Unlocking the Potential of Cd-Free SnS2 Electron Transport Layer for High-Efficiency Sb2(S,Se)3 Solar Cells: A Numerical Simulation Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Numerical Methods and Device Modeling

3. Result and Discussion

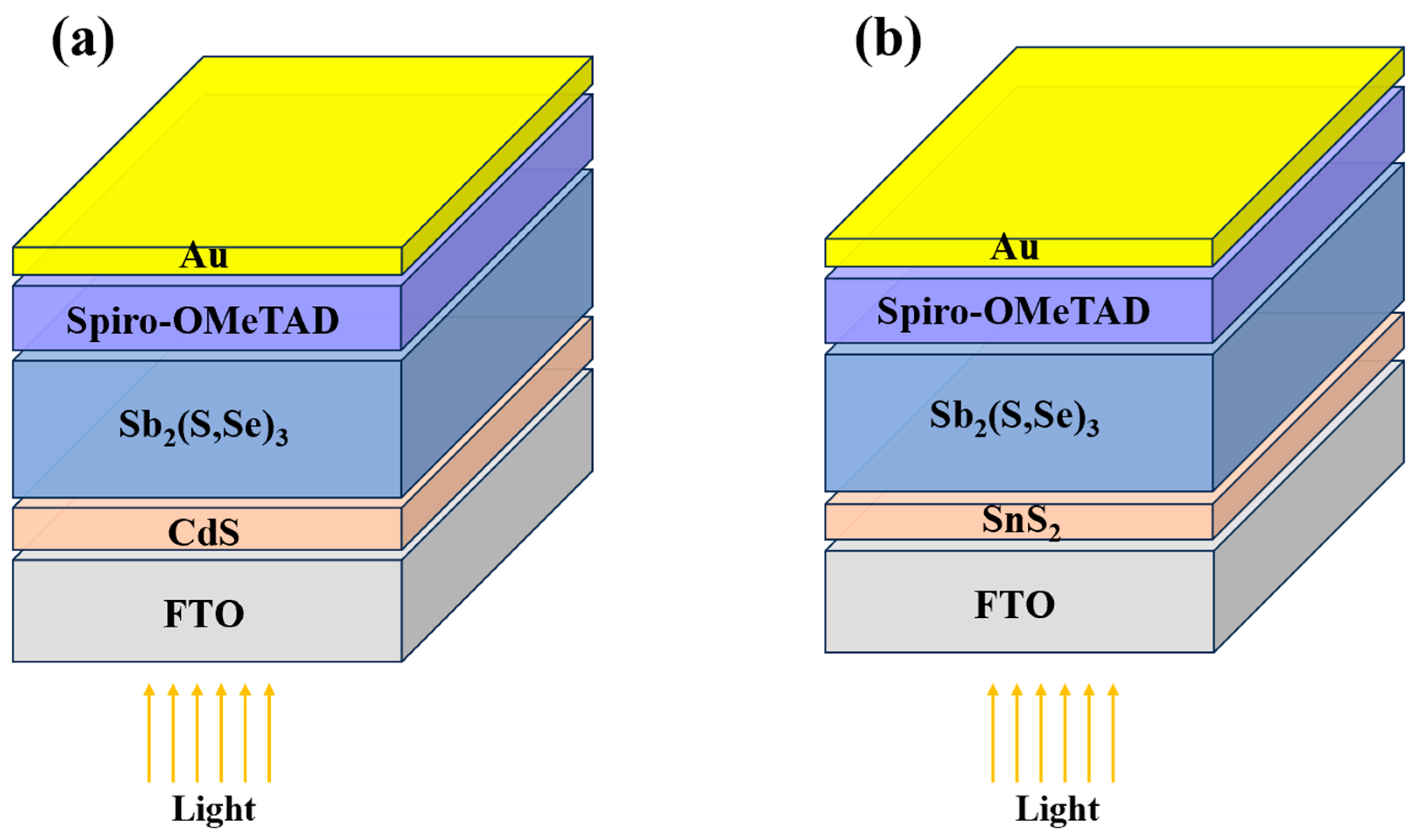

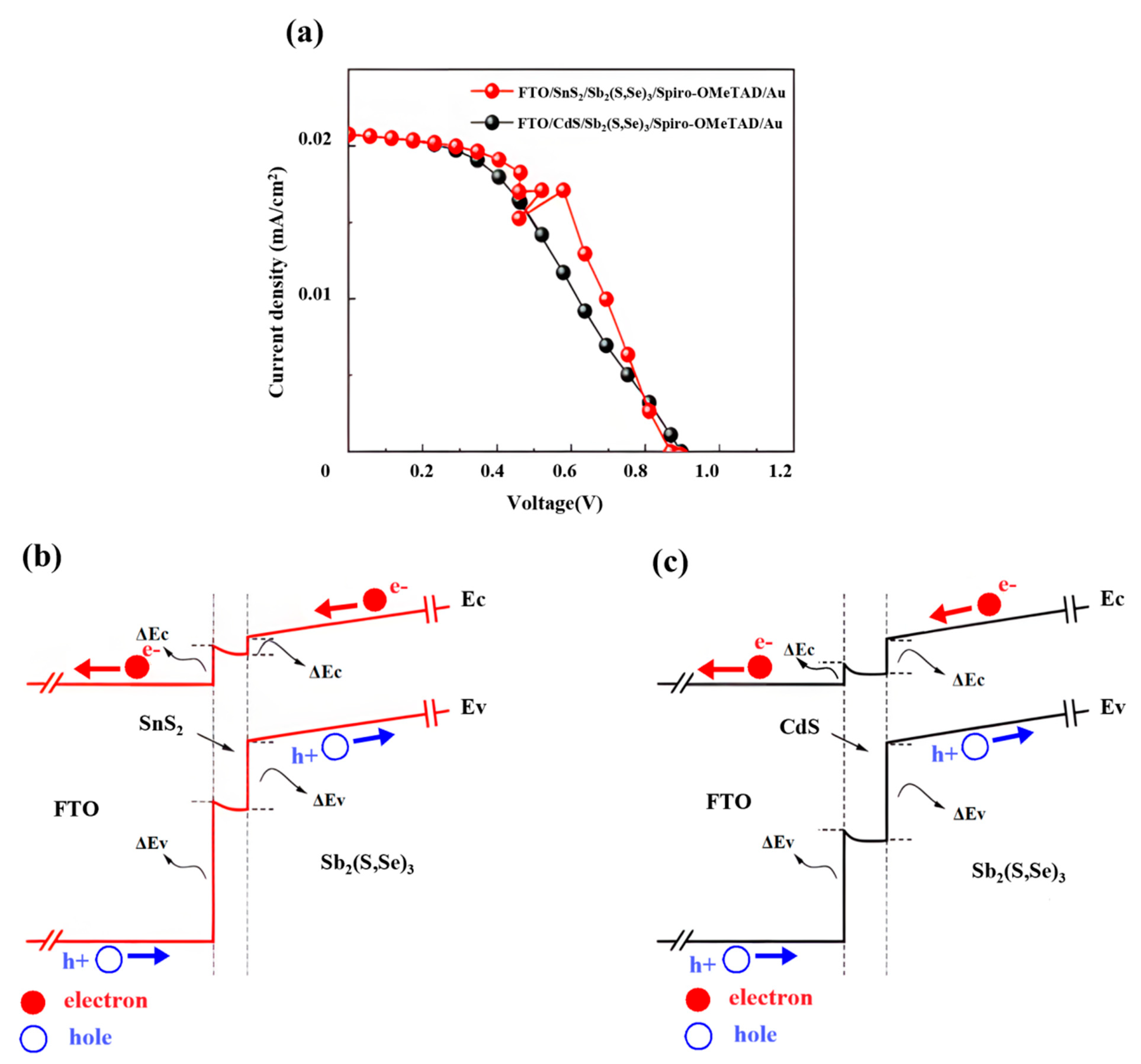

3.1. Superior Interface Band Alignment of the SnS2 Electron Transport Layer

3.2. Performance Optimization of the Sb2(S,Se)3 Solar Cell

3.2.1. Engineering the Absorber Band Gap via Sulfur Composition

3.2.2. Balancing Absorption and Collection with Absorber Thickness

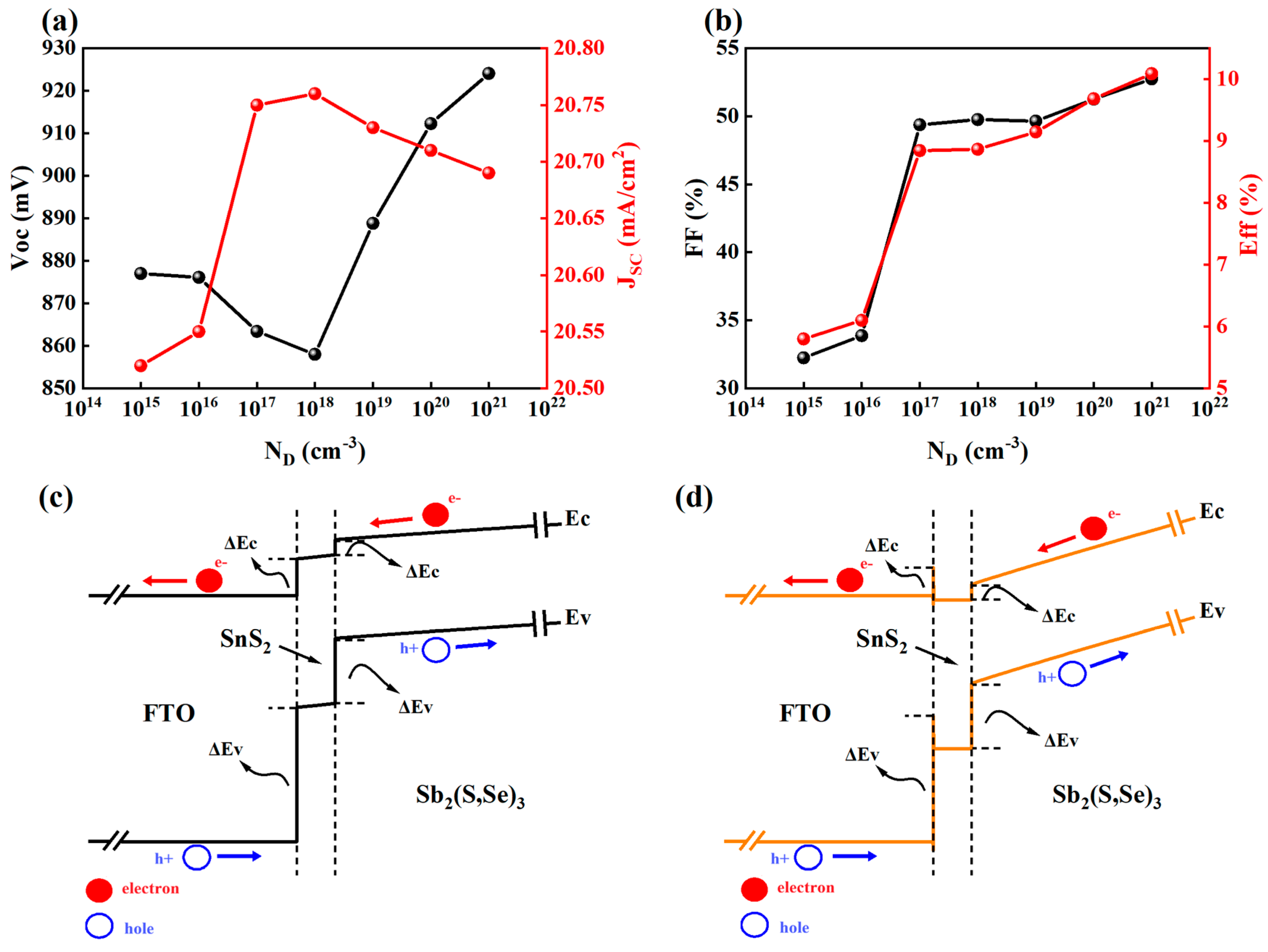

3.2.3. The Pivotal Role of SnS2 Doping in Contact Engineering

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Khan, T.M.; Hosen, A.; Saidani, O.; Al Ahmed, S.R. Artificial Neural Network Assisted Numerical Analysis on Performance Enhancement of Sb2(S,Se)3 Solar Cell with SnS as HTL. Mater. Today Commun. 2024, 40, 109639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, D.Y.; Yang, P.P.; Pan, Y.X.; Wang, Y.Y.; Pan, Y.L.; Weng, G.E.; Hu, X.B.; Tao, J.H.; Chu, J.H.; Akiyama, H.; et al. High Efficiency Sb2(S, Se)3 Thin-Film Solar Cells by Substrate-Temperature-Controlled Vapor Transport Deposition Method. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2025, 280, 113232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rühle, S. Tabulated Values of the Shockley–Queisser Limit for Single Junction Solar Cells. Sol. Energy 2016, 130, 139–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, X.Y.; Pan, Y.L.; Shen, L.Y.; Wang, L.J.; Wang, R.; Weng, G.E.; Jiang, J.C.; Hu, X.B.; Chen, S.Q.; Yang, P.X.; et al. All-Vacuum-Processed Sb2(S,Se)3 Thin Film Photovoltaic Devices via Controllable Tuning Seed Orientation. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2023, 33, 214511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, J.B.; Gao, Q.Q.; Wu, L.; Yang, J.J.; Liu, H.Z.; Wang, W.H.; Tang, R.F.; Li, J.Y.; Cao, Z.X.; Liu, Y.; et al. Carrier Management through Electrode and Electron-Selective Layer Engineering for 10.70% Efficiency Antimony Selenosulfide Solar Cells. Nat. Energy 2025, 10, 857–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.M.; Zhao, Y.Q.; Li, C.; Wang, S.Y.; Chen, X.L.; Gong, J.B.; Wang, X.M.; Xiao, X.D. Hydrazine Hydrate-Induced Surface Modification of CdS Electron Transport Layer Enables 10.30%-Efficient Sb2(S,Se)3 Planar Solar Cells. Adv. Sci. 2022, 9, 2202356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.L.; Che, B.; Zhao, Y.Q.; Wang, S.Y.; Li, H.; Gong, J.B.; Chen, G.L.; Chen, T.; Xiao, X.D.; Li, J.M. Solvent-Assisted Hydrothermal Deposition Approach for Highly-Efficient Sb2(S,Se)3 Thin-Film Solar Cells. Adv. Energy Mater. 2023, 13, 2300391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.F.; Jia, X.G.; Hadke, S.H.; Zhang, J.Y.; Wang, W.; Ma, C.H.; Qiu, J.H.; Yuan, N.Y.; Wong, L.H.; Ding, J.N. Highly Efficient and Thermally Stable Sb2Se3 Solar Cells Based on a Hexagonal CdS Buffer Layer by Environmentally Friendly Interface Optimization. J. Mater. Chem. C 2020, 8, 17194–17201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahan, N.; Ghosh, A.; Ahmed, F.; Buian, M.F.I.; Ali, M.Y.; Miazee, A.A.; Sajid, M.; Nandi, A.; Emon, M.M.H.; Rahman, M.K.; et al. A Comparative Study of CuO Based Solar Cell with ZnTe HTL and SnS2 ETL Using SCAPS 1D Simulation. J. Opt. 2024, 54, 952–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keshtmand, R.; Zamani-Meymain, M.R.; Fallah, M. Enhanced Performance of Planar Perovskite Solar Cells Using Thioacetamide-Treated SnS2 Electron Transporting Layer Based on Molecular Ink. Energy Fuels 2022, 36, 5897–58909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Froitzheim, A.; Stangl, R.; Elstner, L.; Kriege, M.; Fuhs, W. AFORS-HET: A computer-program for the simulation of heterojunction solar cells to be distributed for public use. In Proceedings of the 3rd World Conference on Photovoltaic Energy Conversion, Osaka, Japan, 11–18 May 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Sunny, A.; Al Ahmed, S.R. Numerical Simulation and Performance Evaluation of Highly Efficient Sb2Se3 Solar Cell with Tin Sulfide as Hole Transport Layer. Phys. Status Solidi B 2021, 258, 2000630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dabbabi, S.; Ben Nasr, T.; Kamoun, N.T. CIGS Solar Cells for Space Applications: Numerical Simulation of the Effect of Traps Created by High-Energy Electron and Proton Irradiation on the Performance of Solar Cells. JOM 2018, 71, 602–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saadat, M.; Amiri, O. Fine Adjusting of Charge Carriers Transport in Absorber/HTL Interface in Sb2(S,Se)3 Solar Cells. Sol. Energy 2022, 243, 163–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.K.; Sun, X.X.; Li, C.; Xu, R.; Xu, J.; Du, Y.Y.; Wu, Y.X.; Ni, J.; Cai, H.K.; Li, J.; et al. Electron Transport Layer-Free Planar Perovskite Solar Cells: Further Performance Enhancement Perspective from Device Simulation. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2016, 157, 1038–1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhuiyan, M.A.I.; Reza, M.S.; Ghosh, A.; Al-Dmour, H.; Kumar, Y.A.; Rahim, M.I.I.; Aktarujjaman, M.; Yeasmin, F.; Al-Lohedan, H.; Ramalingam, R.J.; et al. Optimized RbPbI3-Based Perovskite Solar Cells with SnS2 ETL and MoO3 HTL Achieving Simulated PCE of 32.72%. Opt. Commun. 2025, 583, 131761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.L.; Zhang, L.S.; Chen, Z.G.; Hu, J.Q.; Li, S.J.; Wang, Z.H.; Liu, J.S.; Wang, X.C. Semiconductor Heterojunction Photocatalysts: Design, Construction, and Photocatalytic Performances. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2014, 43, 5234–5244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.B.; Wang, W.W.; Dong, F.; Zhang, Z.Q.; Han, L.; Luo, X.D.; Huang, J.T.; Feng, Z.J.; Chen, Z.; Jia, G.H.; et al. Recent Advances in Noncontact External-Field-Assisted Photocatalysis: From Fundamentals to Applications. ACS Catal. 2021, 11, 4739–4769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, T.; Xu, W.D.; Xu, S.D.; Ratnasingham, S.R.; Lin, C.T.; Kim, J.; Briscoe, J.; McLachlan, M.A.; Durrant, J.R. Light-Intensity and Thickness Dependent Efficiency of Planar Perovskite Solar Cells: Charge Recombination versus extraction. J. Mater. Chem. C 2020, 8, 12648–12655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gharibshahian, I.; Orouji, A.A.; Sharbati, S. Efficient Sb2(S,Se)3/Zn(O,S) solar cells with high open-circuit voltage by controlling sulfur content in the absorber-buffer layers. Sol. Energy 2021, 227, 606–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolas-Marin, M.M.; Ayala-Mato, F.; Vigil-Galan, O.; Courel, M. Simulation analysis of Cd1-xZnxS/Sb2(Se1-xSx)3 solar cells with n-i-p structure. Sol. Energy 2021, 224, 245–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pisoni, S.; Fu, F.; Widmer, R.; Carron, R.; Moser, T.; Groening, O.; Tiwari, A.N.; Buecheler, S. Impact of Interlayer Application on Band Bending for Improved Electron Extraction for Efficient Flexible Perovskite Mini-Modules. Nano Energy 2018, 49, 300–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaker, A.; Salem, M.S.; Jayan, K.D. Analysis and Design of p-n Homojunction Sb2Se3 Solar Cells by Numerical Simulation. Sol. Energy 2022, 242, 276–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.T.; Xie, L.; Wu, T.; Ge, C.H.; Hua, Y. Constructing Spike-like Energy Band Alignment at the Heterointerface in Highly Efficient Perovskite Solar Cells. Chem. Sci. 2023, 14, 2877–2886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Parameter | FTO | Sb2(S,Se)3 | Spiro-oMeTAD | CdS | SnS2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thickness (nm) | 230 | 260 | 90 | 62 | 50 |

| εr | 9 | 14.38 | 3 | 10 | 10 |

| χ (eV) | 4.8 | 4.01 | 2 | 4.5 | 4.24 |

| Eg (eV) | 3.7 | 1.49 | 3 | 2.4 | 2.24 |

| NC (cm−3) | 2.2 × 1018 | 2.2 × 1018 | 2.5 × 1018 | 2.2 × 1018 | 2.2 × 1018 |

| NV (cm−3) | 1.8 × 1019 | 1.8 × 1020 | 1.8 × 1019 | 1.8 × 1019 | 1.8 × 1019 |

| µe [cm2/Vs] | 20 | 14 | 1.0 × 10−4 | 100 | 50 |

| µp [cm2/Vs] | 10 | 2.6 | 2.0 × 10−4 | 25 | 50 |

| NA (cm−3) | – | 1.0 × 1014 | 5.0 × 1018 | – | – |

| ND (cm−3) | 1.0 × 1020 | – | – | 4.0 × 1017 | 1017 |

| [cm/s] | 1.0 × 107 | 1.0 × 107 | 1.0 × 1018 | 1.0 × 107 | 1.0 × 107 |

| [cm/s] | 1.0 × 107 | 1.0 × 107 | 1.0 × 1018 | 1.0 × 107 | 1.0 × 107 |

| Defect Parameters | FTO | Sb2(S,Se)3 | Spiro-oMeTAD | CdS | SnS2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Defect 1 | Defect 2 | |||||

| Type | Single acceptor | Single acceptor | Single acceptor | Single acceptor | Single donor | Single acceptor |

| Nt | 1.0 × 1015 | 1.3 × 1014 | 1.0 × 1015 | 1.0 × 1018 | 1.0 × 1014 | 1.0 × 1012 |

| σe (cm2) | 1.0 × 10−15 | 1.99 × 10−14 | 1.99 × 10−14 | 1.0 × 10−15 | 3.0 × 10−15 | 3.0 × 10−15 |

| σh (cm2) | 1.0 × 10−15 | 1.99 × 10−14 | 1.99 × 10−14 | 1.0 × 10−15 | 2.0 × 10−14 | 2.0 × 10−14 |

| RS (Ω·cm−2) | 3.7 |

| RSH (Ω·cm−2) | 751.2 |

| Parameter | ΔEC (eV) | ΔEV (eV) |

|---|---|---|

| CdS | 0.49 | 1.40 |

| SnS2 | 0.23 | 0.98 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zheng, X.; Ishaq, M.; Ai, J.; Shah, W.A. Unlocking the Potential of Cd-Free SnS2 Electron Transport Layer for High-Efficiency Sb2(S,Se)3 Solar Cells: A Numerical Simulation Study. Electronics 2025, 14, 4926. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14244926

Zheng X, Ishaq M, Ai J, Shah WA. Unlocking the Potential of Cd-Free SnS2 Electron Transport Layer for High-Efficiency Sb2(S,Se)3 Solar Cells: A Numerical Simulation Study. Electronics. 2025; 14(24):4926. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14244926

Chicago/Turabian StyleZheng, Xiaodong, Muhammad Ishaq, Jianwen Ai, and Wahab Ali Shah. 2025. "Unlocking the Potential of Cd-Free SnS2 Electron Transport Layer for High-Efficiency Sb2(S,Se)3 Solar Cells: A Numerical Simulation Study" Electronics 14, no. 24: 4926. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14244926

APA StyleZheng, X., Ishaq, M., Ai, J., & Shah, W. A. (2025). Unlocking the Potential of Cd-Free SnS2 Electron Transport Layer for High-Efficiency Sb2(S,Se)3 Solar Cells: A Numerical Simulation Study. Electronics, 14(24), 4926. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14244926