1. Introduction

In the era of intelligent manufacturing, known as Industry 4.0, the reliability of rotating machinery is paramount for maintaining operational continuity and efficiency [

1]. This paradigm relies heavily on robust data-driven solutions and automated platforms, often integrated via the Internet of Things (IoT) [

2]. Rolling element bearings, critical components supporting rotational motion, are the primary source of mechanical failures, often accounting for nearly 50 of all machine faults [

3]. Effective, automated bearing fault diagnosis (BFD) based on vibration signal analysis is thus essential for robust Predictive Maintenance (PdM) systems [

4].

Historically, BFD relied on classical Machine Learning (ML) algorithms, such as Support Vector Machines (SVMs) and shallow Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs), which necessitated intensive, manual feature engineering based on time- and frequency-domain statistical metrics [

5]. While successful in controlled laboratory environments, these methods face limitations in scalability, robustness, and interpretability when deployed in complex industrial environments.

Deep Learning (DL) models, specifically Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs), offered a breakthrough by enabling automatic, hierarchical learning of discriminative representations directly from sensor data [

6]. One-dimensional CNNs (1D-CNNs) have proven particularly effective for processing 1D vibration signals, mitigating the need for time-consuming manual feature extraction [

7]. Recent studies have extended this capability to various manufacturing processes; for instance, Chen et al. [

8] utilized optimized 1D-CNNs to extract features from multisource signals for surface roughness prediction in precision grinding, while Chatterjee et al. [

9] demonstrated the efficacy of 1D-CNNs in classifying acoustic emission sources in Laser Powder Bed Fusion.

1.1. Performance–Interpretability Dilemma

Despite the high accuracy achieved by DL, its adoption in critical industrial systems faces the significant hurdle of the “black-box” problem. Models that cannot explain their predictions generate distrust among engineers and operators [

10]. To mitigate this, recent frameworks in processes like Electrochemical Machining (ECM) [

11] and micro-EDM [

12] have successfully integrated XAI methods such as SHAP and Grad-CAM to align deep learning outputs with physical process knowledge. In a PdM context, understanding which physical features (e.g., RMS, Kurtosis) contributed to an alarm is vital for confirming that the diagnosis stems from genuine mechanical defects rather than data artifacts.

Most published BFD research focuses almost exclusively on maximizing performance metrics, neglecting the critical layer of Explainable Artificial Intelligence (XAI). Furthermore, comparative evaluations between traditional ANN models and CNN architectures are often scarce, and statistical significance testing of performance differences is frequently overlooked [

13]. This lack of transparency and rigorous validation limits the practical adoption of advanced DL models.

1.2. Comparative Context and Baseline Study

This work utilizes a publicly available dataset from the Zenodo repository [

14]. This dataset encompasses seven fault classes, including structural and lubrication-related faults. The input features are a vector of 15 statistical features derived from three sensors, as detailed in

Section 3.1.

The study represents a direct and rigorous methodological enhancement of the diagnostic methods proposed in the baseline work by Vlachou et al. (2025) [

2]. Vlachou et al. (2025) developed a diagnostic framework for ball bearing induction motors using vibration analysis, integrating SVM and ANN-MLP models within an IoT-enabled Industry 4.0 edge–cloud architecture [

2]. Their primary contribution focused on IoT integration, feature extraction (statistical and frequency-domain), and achieving high accuracy (>95%) [

2]. However, their approach lacked XAI interpretability and rigorous statistical comparative analysis, leaving a gap in model verification and confidence.

1.3. Novelty Statement and Contributions

This work aims to bridge the gap in validation rigor and interpretability for intelligent bearing fault diagnosis, which is crucial for advanced engineering systems. This paper makes the following key contributions:

Rigorous Architectural Comparison and Critical Fault Detection: Provides a direct, fair comparison of the performance of ANN-MLP, 1D-CNN, and ResNet-1D operating on the same 15-feature vibration vector. Crucially, the study demonstrates that ResNet-1D is the only model capable of achieving perfect detection (F1-score = ) for the critical and difficult-to-isolate Abrasive Particles (6) fault, a finding that empirically justifies its added complexity.

Statistical Validation: Implements a rigorous statistical validation method (paired t-test on 100 bootstrap samples) to scientifically confirm the statistical superiority of the ResNet-1D architecture over the baseline 1D-CNN model (t-statistic , ).

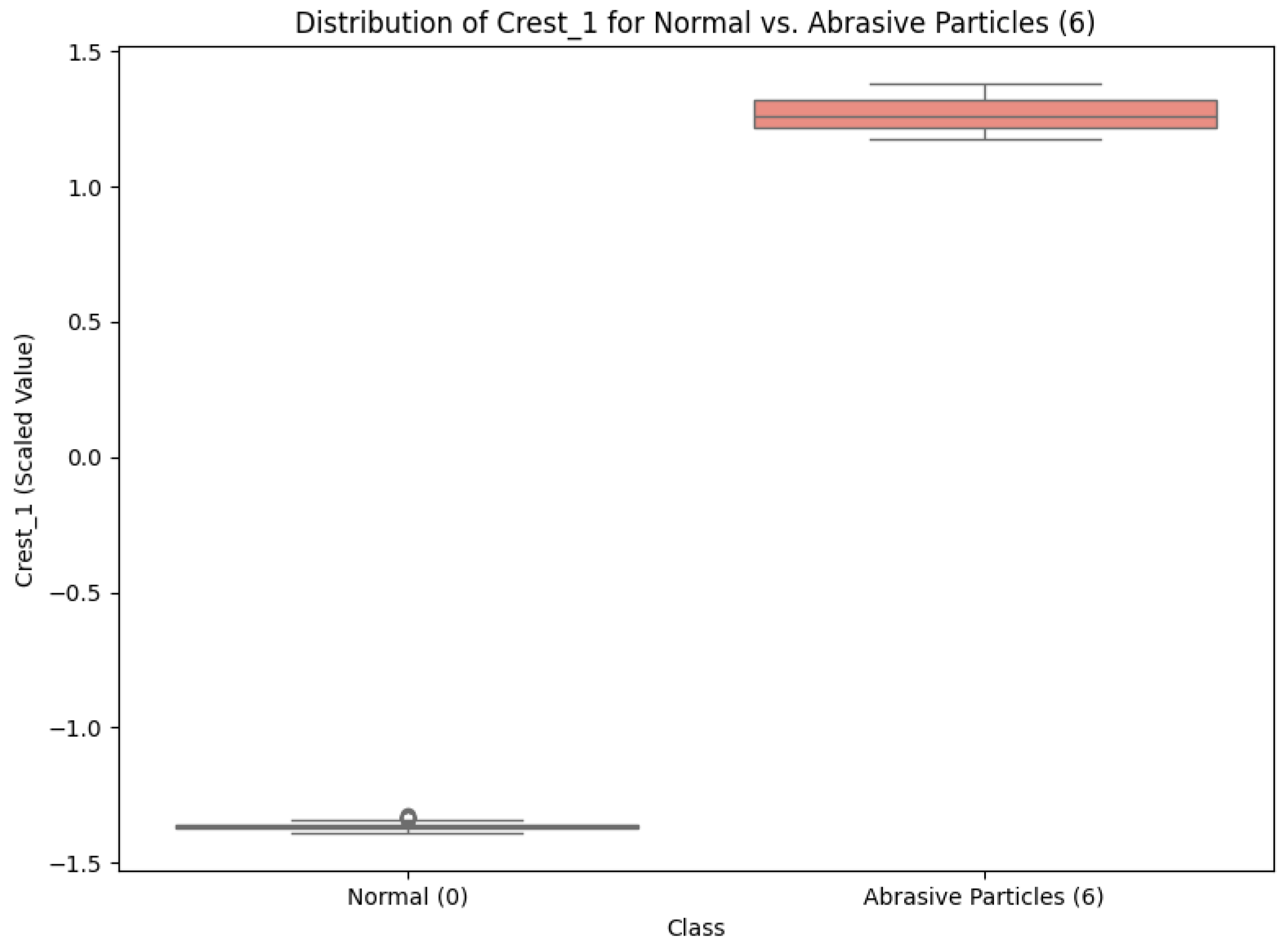

SHAP-Based Model Interpretation for Physical Validation: Applies SHAP to the statistically superior ResNet-1D model to provide global and local feature attribution. This analysis validates the model’s reliance on physically relevant signal characteristics, confirming that Crest_1 is the dominant feature for identifying the Abrasive Particles fault.

Edge Deployment Suitability (Thematic): Acknowledges the 1D-CNN design’s suitability for edge deployment due to its compact feature vector, directly addressing practical needs in Industry 4.0 environments.

Table 1 details the innovative methodological elements compared to the baseline work.

2. Related Works

The development of intelligent Fault Detection and Diagnosis (FDD) systems requires integrating advanced algorithms with robust condition monitoring techniques, ensuring transparent and verifiable outcomes [

15]. The increasing connectivity and autonomy of manufacturing equipment necessitates solutions compatible with Industry 4.0 frameworks, where security and transparency, often empowered by technologies like Blockchain, complement the XAI objective [

16]. This review focuses on the context of vibration diagnostics [

17], relevant Deep Learning (DL) architectures, Explainable AI (XAI) techniques, and the necessity of statistical validation rigor.

2.1. Foundation of Machine Condition Monitoring: Statistical Feature Extraction

Condition monitoring of rotating machinery traditionally relies on analyzing a comprehensive set of statistical and spectral features [

18]. These statistical metrics are highly sensitive to changes in the vibration signal characteristics that accompany fault development [

19]. Time-domain features, such as Root Mean Square (RMS) and Peak values, are crucial indicators of overall vibration energy, while Kurtosis and Crest Factor offer insights into the amplitude distribution shape, which is particularly useful for the early detection of localized bearing faults (impulsive events) [

18].

Early FDD systems utilized these statistical feature vectors as input for shallow Machine Learning (ML) classifiers like Support Vector Machines (SVMs) and Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs) [

5]. While these methods proved effective, their performance remains strongly dependent on expert-driven feature engineering [

19]. The subsequent shift toward Deep Learning enabled automated feature learning [

6], although the utilization of highly optimized, pre-processed statistical features is still favored in many works for reducing computational complexity and retaining physical context-a necessary compromise, especially for edge computing deployment.

The 15 statistical features used in this study, derived from three sensors measuring Velocity (V), Acceleration (a), and Temperature (Temp), are detailed in

Table 2 for complete reproducibility.

2.2. Deep Learning Architectures for Vibration Signal Analysis

Deep learning models, especially Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs), have emerged as the dominant tool for intelligent fault diagnosis [

6,

20]. One-dimensional Convolutional Neural Networks (1D-CNNs) are uniquely suited for processing sequential vibration signals [

7], utilizing local filters to automatically extract hierarchical, translationally invariant fault signatures. Research consistently shows that 1D-CNNs surpass traditional shallow networks in BFD tasks, often achieving average accuracies above 99% across various operating conditions. The intrinsic ability of 1D-CNNs to model complex correlations within feature sequences provides a key advantage over fully connected networks like ANN-MLP.

More complex, state-of-the-art DL models for BFD include hybrid architectures that combine 1D Convolutional Residual Networks (1D Conv ResNet) with Bi-directional Long Short-Term Memory (BiLSTM) and Attention mechanisms to capture both spatial and temporal dependencies in non-stationary signals [

3]. While these complex models often achieve state-of-the-art results, they entail significantly higher computational demands, making them less suitable for deployment on resource-constrained edge devices crucial for modern PdM systems. Therefore, architectures like the simpler 1D-CNN and the robust ResNet-1D, operating on compact feature vectors, offer a superior performance-to-complexity balance for practical edge deployment.

Reviews confirm the superior performance of DL methods, including DenseNet and ResNet variants, compared to classical ML approaches [

6]. Furthermore, transfer learning based on 1D-CNNs has been proposed to enhance diagnostic efficiency when dealing with limited data availability [

21].

2.3. Explainable AI (XAI) for Transparency in Predictive Maintenance

The deployment of sophisticated DL algorithms in mission-critical industrial systems necessitates tools that ensure auditability and engender trust. Explainable Artificial Intelligence (XAI) addresses the “black-box” problem by providing insights into the model’s decision-making process [

10]. In the broader context of intelligent manufacturing, XAI is essential for physical interpretability, allowing engineers to verify that a model’s prediction aligns with known process physics (e.g., in machining or additive manufacturing). In PdM, understanding feature contribution is essential for validating the diagnosis and preventing maintenance based on spurious correlations [

22].

The SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) method, due to its strong theoretical grounding in cooperative game theory, has become a standard for model-agnostic feature attribution [

22]. SHAP is broadly applied in machine diagnostics to identify the most influential input features [

23]. Studies have used SHAP to not only explain models like SVM and kNN but also to guide feature engineering [

23]. For instance, by using SHAP to analyze the contribution of statistical features [

23], researchers confirmed that metrics like Skewness and Shape Factor are dominant factors in diagnostic outcomes, allowing for informed feature set reduction without performance loss [

24]. The application of SHAP allows for the physical validation of the model, confirming that diagnostic alarms are indeed tied to physically relevant indicators like acceleration RMS or Crest Factor. Other XAI methods, such as Frequency Activation Maps (FAMs) [

25] or frameworks integrating XAI for signal diagnosis [

26], offer complementary perspectives on model transparency.

2.4. Methodological Rigor: Statistical Validation in Model Comparison

To enhance the academic and practical rigor of FDD studies, it is critical to employ robust statistical validation methods that move beyond simple comparisons of point accuracy [

13]. Experts in model validation warn against “optimism bias” which undermines confidence in reported architectural superiority [

13].

In comparing DL models, resampling techniques, such as bootstrapping, are essential for generating a distribution of performance results, enabling the use of formal statistical tests. The paired

t-test applied to the distributions of performance metrics (such as Macro F1-score) obtained from multiple bootstrap iterations is a well-established and powerful method for confirming whether the performance difference between two architectures (e.g., ResNet-1D vs. 1D-CNN) is statistically significant. Specifically, performing the paired

t-test on a sufficiently large number of bootstrap samples (

in this work) ensures a robust measure of statistical power [

15]. The rigorous statistical approach taken in this study addresses the methodological gap found in many previous works, including the initial framework by Vlachou et al. (2025) [

2], which did not include such detailed statistical validation.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Dataset and Feature Engineering

The basis of this analysis is the bearing vibration dataset available on Zenodo repository [

14]. This data, originally introduced by Vlachou et al. (2025) [

2], contains vibration and temperature data characterizing seven bearing health states, including structural faults (inner race, outer race, rolling element) and lubrication states (under-greased, over-greased) [

2].

Each diagnostic record is represented by 15 pre-processed statistical features. This compact, feature-based representation is computationally efficient and aligns with real-world constraints for edge-device deployment in Industry 4.0 systems, which often prioritize data transmission efficiency over raw signal processing. The complete list of features, which includes metrics such as V-RMS, a-RMS, a-Peak, Crest Factor, and Temperature, measured across three sensor locations, is provided for reproducibility in

Table 2.

To ensure data quality, Z-score standardization was applied to all 15 features. The scaler was fitted exclusively on the training set to prevent data leakage. The data was split into training (80%) and testing (20%) sets using chronological block splitting, where the last 20% of the time-ordered data constituted the test set. This method ensures temporal independence between the training and test samples, mitigating the risk of data leakage inherent in random shuffling of time-series windowed data. The split also employed stratification to maintain class distribution integrity. The class distribution of the test set is detailed in

Figure 1. Exploratory data analysis was conducted to assess feature discriminative power.

Figure 2 illustrates the distribution of Crest_1 between the Normal state and the critical Abrasive Particles (6) fault, revealing a clear separation that supports its relevance for fault detection, consistent with physical principles.

3.2. Model Architectures and Training Setup

All training parameters, including the optimizer and hyperparameters, were unified for all models (ANN-MLP, 1D-CNN, and ResNet-1D) to ensure an objective comparison.

3.2.1. Artificial Neural Network–Multilayer Perceptron (ANN-MLP)

The ANN-MLP model is a classic feed-forward network, consisting of an input layer (15 features), four fully connected hidden layers (30 neurons each), utilizing the ReLU activation function. Batch Normalization was applied after each hidden layer to stabilize gradients and accelerate convergence. The output layer comprised seven neurons with Softmax activation for multi-class classification.

3.2.2. One-Dimensional Convolutional Neural Network (1D-CNN) and ResNet-1D

The 1D-CNN and ResNet-1D models were designed to leverage the specialized ability of convolution to extract hierarchical features. The architecture of the 1D-CNN included two convolutional blocks (32 and 64 filters, kernel size 3, ReLU, Batch Normalization), followed by a Flatten layer, a dense layer (60 neurons, ReLU), and Dropout (rate = 0.5) to mitigate overfitting. The ResNet-1D architecture introduced residual connections to enhance feature learning depth and mitigate the vanishing gradient problem.

Justification for 1D Convolution on Tabular Features: It is acknowledged that the theoretical argument exists regarding the methodological challenge of applying 1D convolution to a permutation-invariant vector of statistical features. However, the input feature vector was deliberately and logically ordered (grouping features from Sensor 1, Sensor 2, and Sensor 3 consecutively, as detailed in

Table 2). This deliberate ordering allows the 1D convolution with a small kernel (size 3) to effectively learn non-linear, localized interactions between physically related features (e.g., the relationship between V-RMS and Crest Factor on a single sensor) that a permutation-invariant MLP cannot capture. The superior performance of ResNet-1D (F1-score

for the critical class) serves as strong empirical validation for this methodological choice.

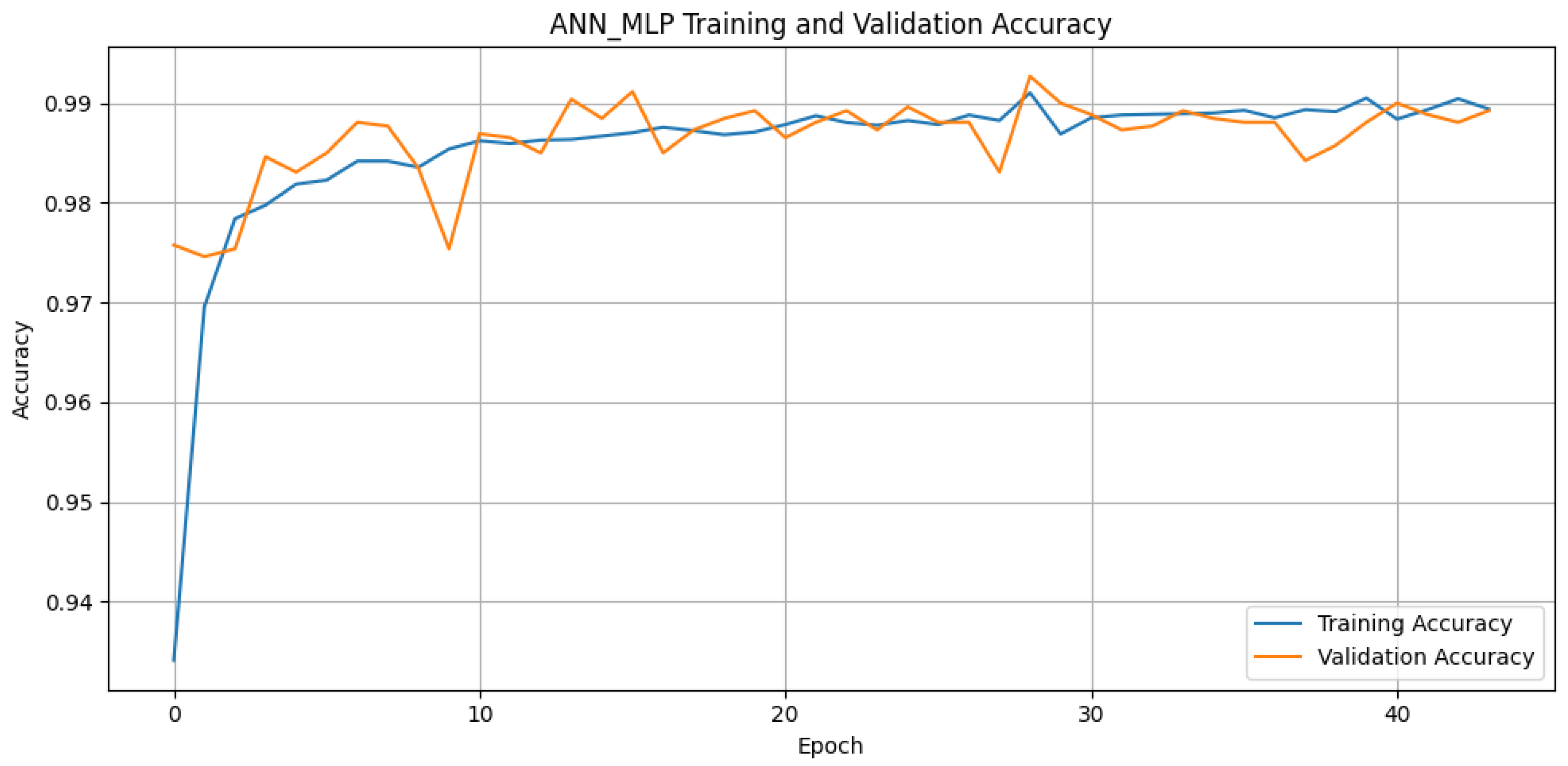

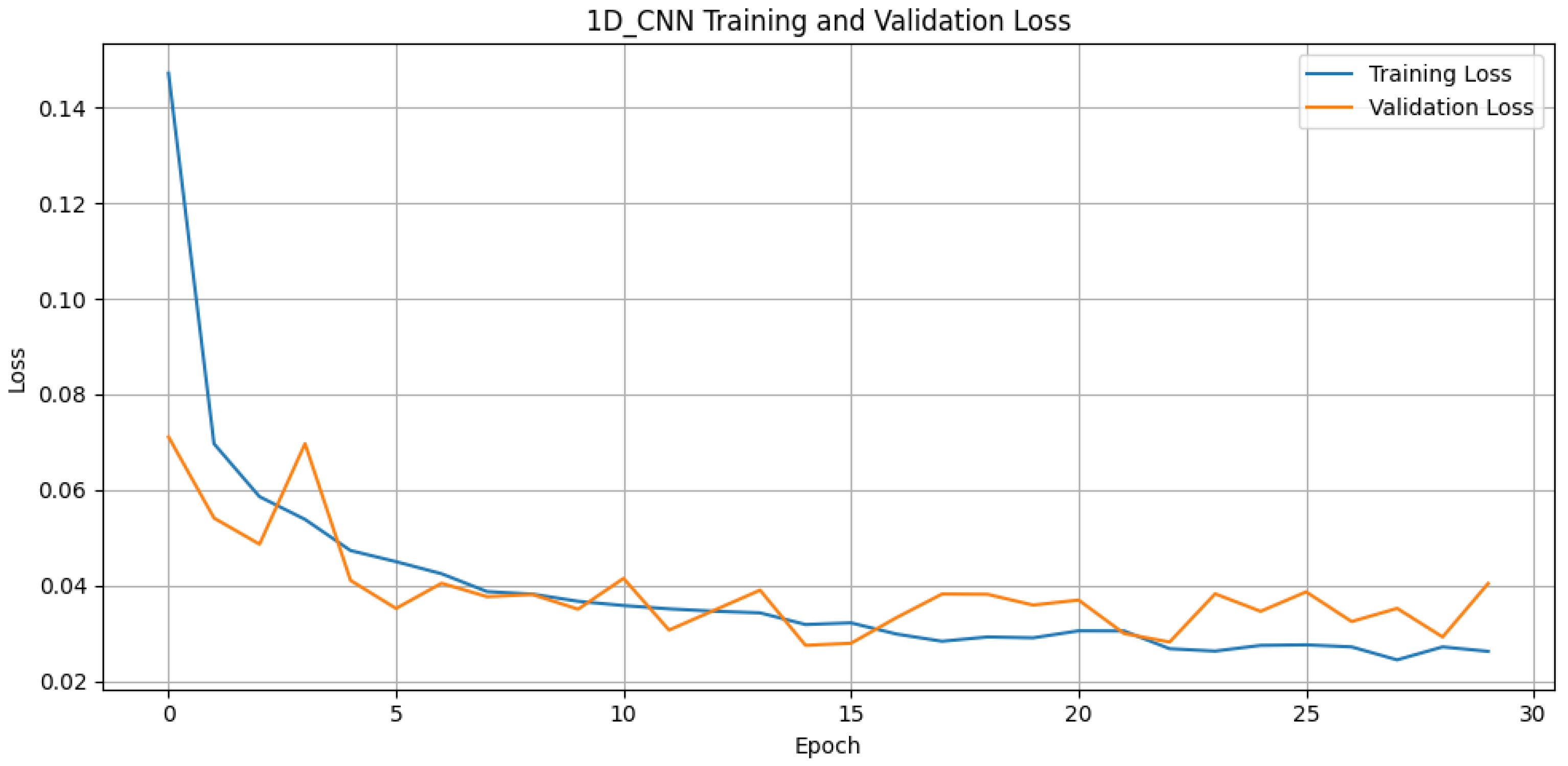

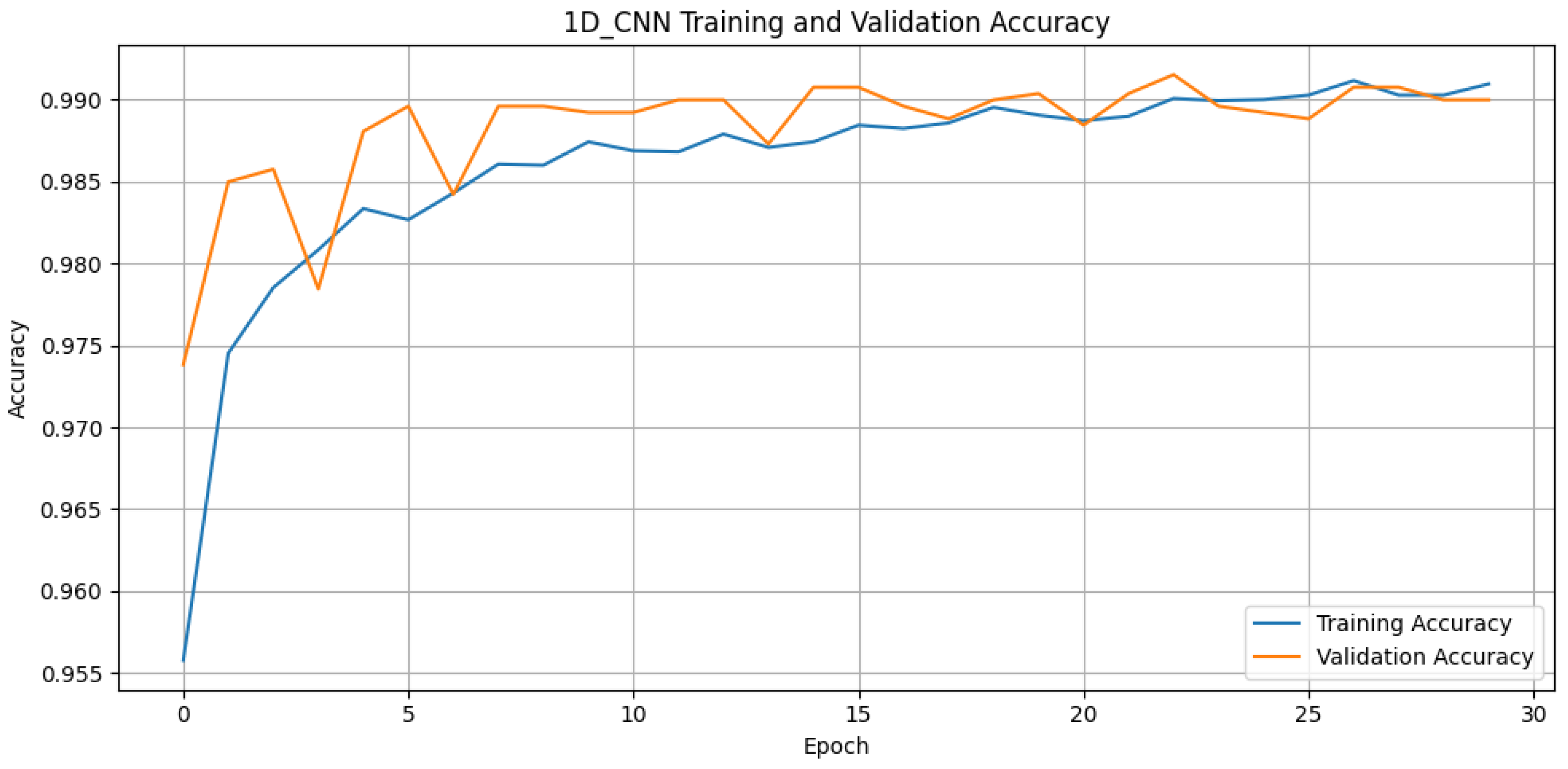

Training for both models utilized the Sparse Categorical Cross-Entropy loss function and the Nadam optimizer (learning rate 0.001). Early stopping (patience = 15) and checkpointing were implemented based on validation accuracy to ensure optimal generalization. The training dynamics for both models, including loss and accuracy curves, are presented in

Appendix A (

Figure A1,

Figure A2,

Figure A3,

Figure A4,

Figure A5 and

Figure A6).

3.3. Performance Evaluation and Statistical Validation

Model performance was measured using Accuracy, Macro F1-score, and Macro AUC. Macro F1-score was the preferred synthesis metric due to its robustness in multi-class classification, ensuring a reliable assessment across all seven fault categories.

To rigorously compare the architectures, 100 independent bootstrap samples of the Macro F1-score were generated for the top-performing models (ResNet-1D and 1D-CNN). A paired t-test was then applied to these 100 pairs of scores to statistically confirm that the superior performance of ResNet-1D was statistically significant () and not due to random chance.

3.4. SHAP Implementation for Model Interpretability

SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) was applied to the statistically superior ResNet-1D model to provide crucial interpretability [

23]. The analysis focused specifically on the Abrasive Particles (6) fault, which was the most difficult-to-detect class for the simpler models.

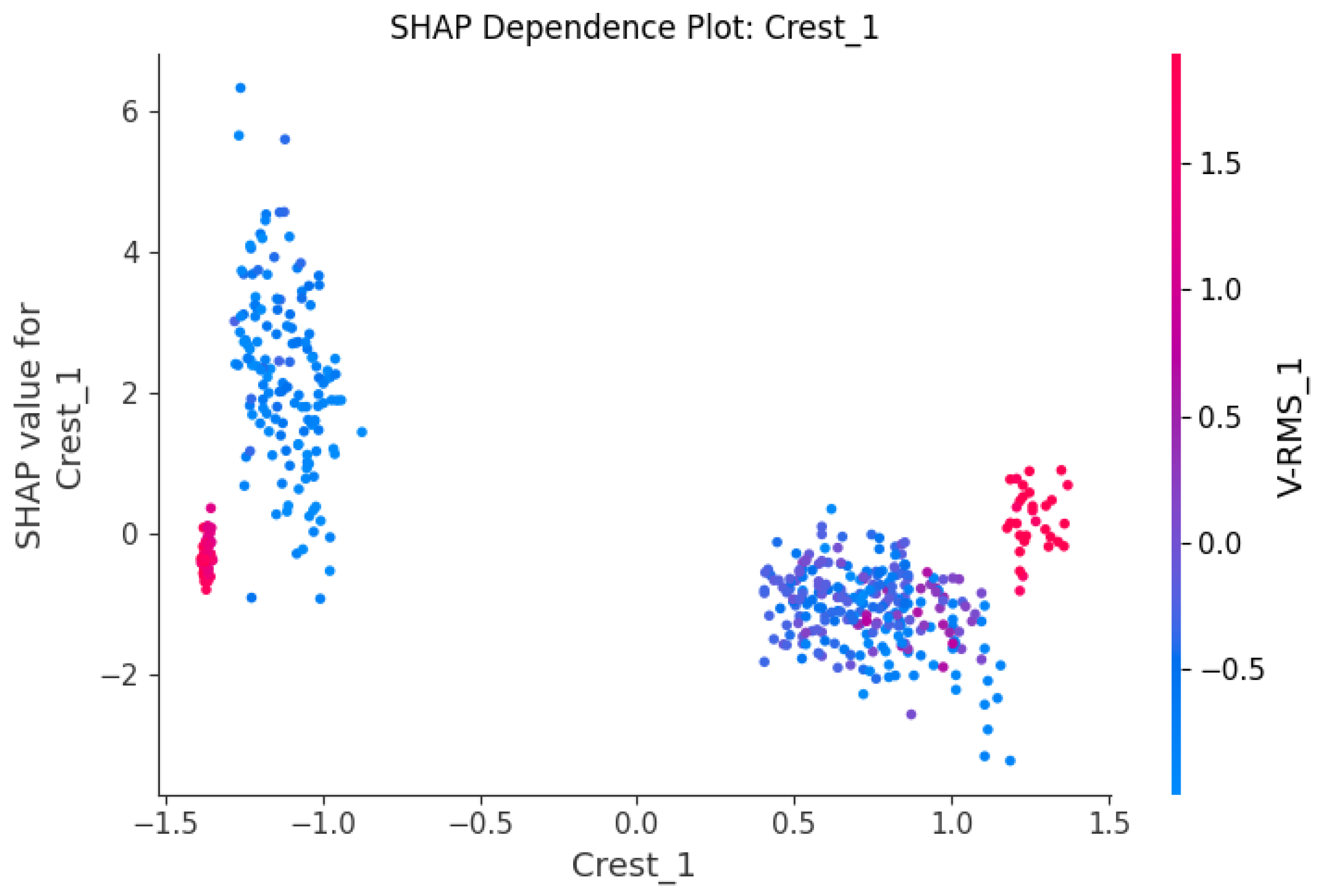

Global Importance: Used mean absolute SHAP values to rank features, confirming that Crest_1 is the dominant feature for this critical fault.

Direction of Influence: Used Beeswarm Plots to visualize how feature magnitudes (high Crest_1) affect the prediction score for the Abrasive Particles fault.

Local Verification: Used Waterfall Plots to provide detailed, local explanations for critical predictions, linking the model output directly to measured physical values.

3.5. Reproducibility

To ensure full transparency and replicability of this study, all data preprocessing, model training, and interpretability scripts are provided in the

Supplementary Material section. Furthermore, the complete computational environment and specific library versions used for execution are detailed in

Appendix C (

Table A1) to guarantee exact replication of the analytical pipeline.

4. Results

This section presents the rigorous comparative performance of the ANN-MLP, 1D-CNN, and ResNet-1D models on the temporally independent test set. All architectures were trained under identical conditions to ensure a fair and objective comparison.

4.1. Overall Performance and Critical Fault Breakthrough

The comprehensive performance evaluation of the three models on the test set is summarized in

Table 3.

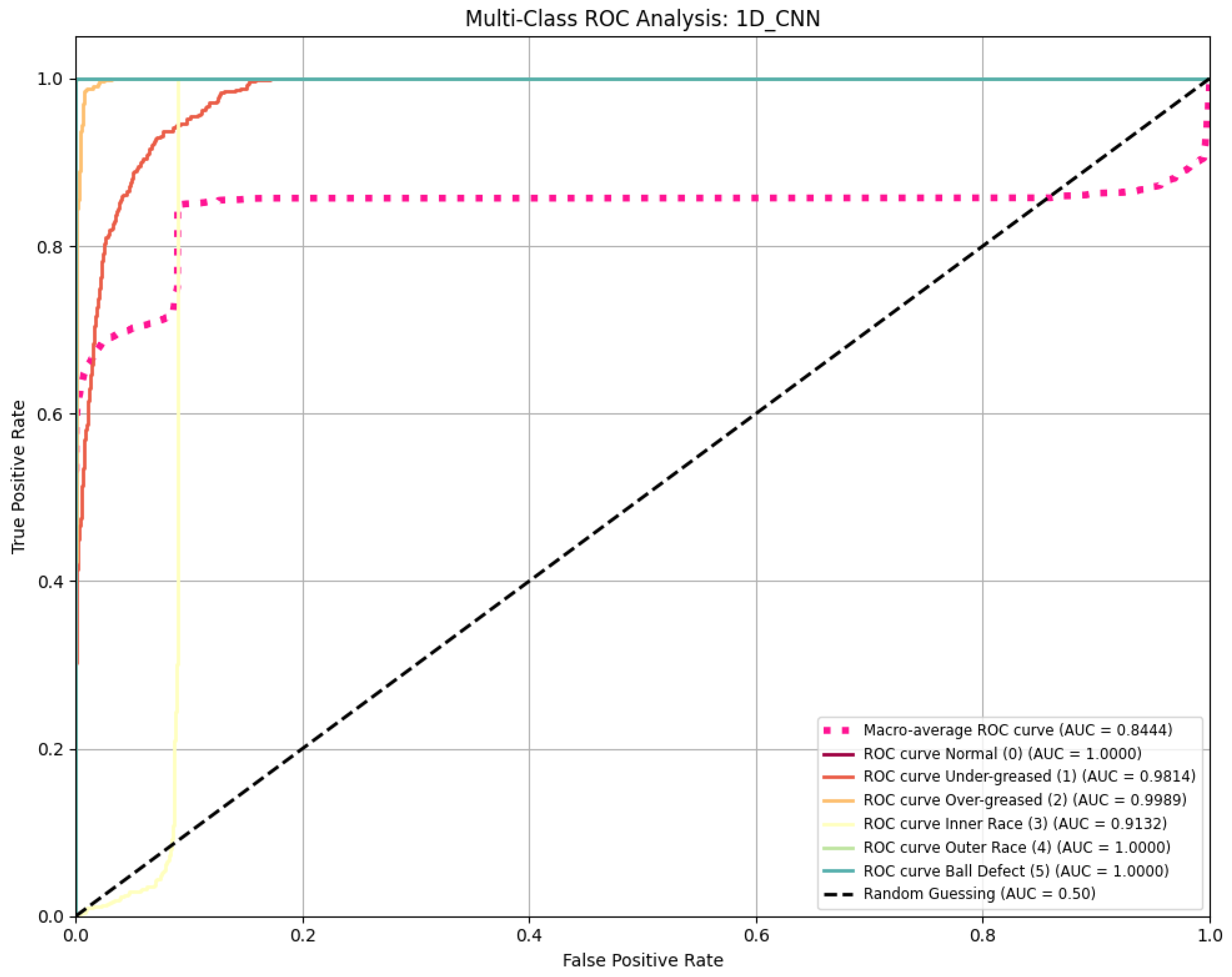

As shown in

Table 3, both the ANN-MLP and 1D-CNN exhibited a significant performance deficit, particularly reflected in their low Macro F1-scores (∼0.70–0.73). In sharp contrast, the ResNet-1D model achieved the highest overall performance, with 0.9926 accuracy and a Macro F1-score of 0.9913. This architectural enhancement resulted in an average performance gain of 0.2846 in Macro F1-score over the simple 1D-CNN model. The superior discriminatory capability of ResNet-1D is further confirmed by a near-perfect Macro AUC value of 0.9998.

4.2. Detailed Classification Robustness: Failure to Breakthrough

Per-class precision, recall, and F1-scores for all three models are provided in

Table 4,

Table 5 and

Table 6. These reports reveal the critical difference between the baseline models and the proposed architecture.

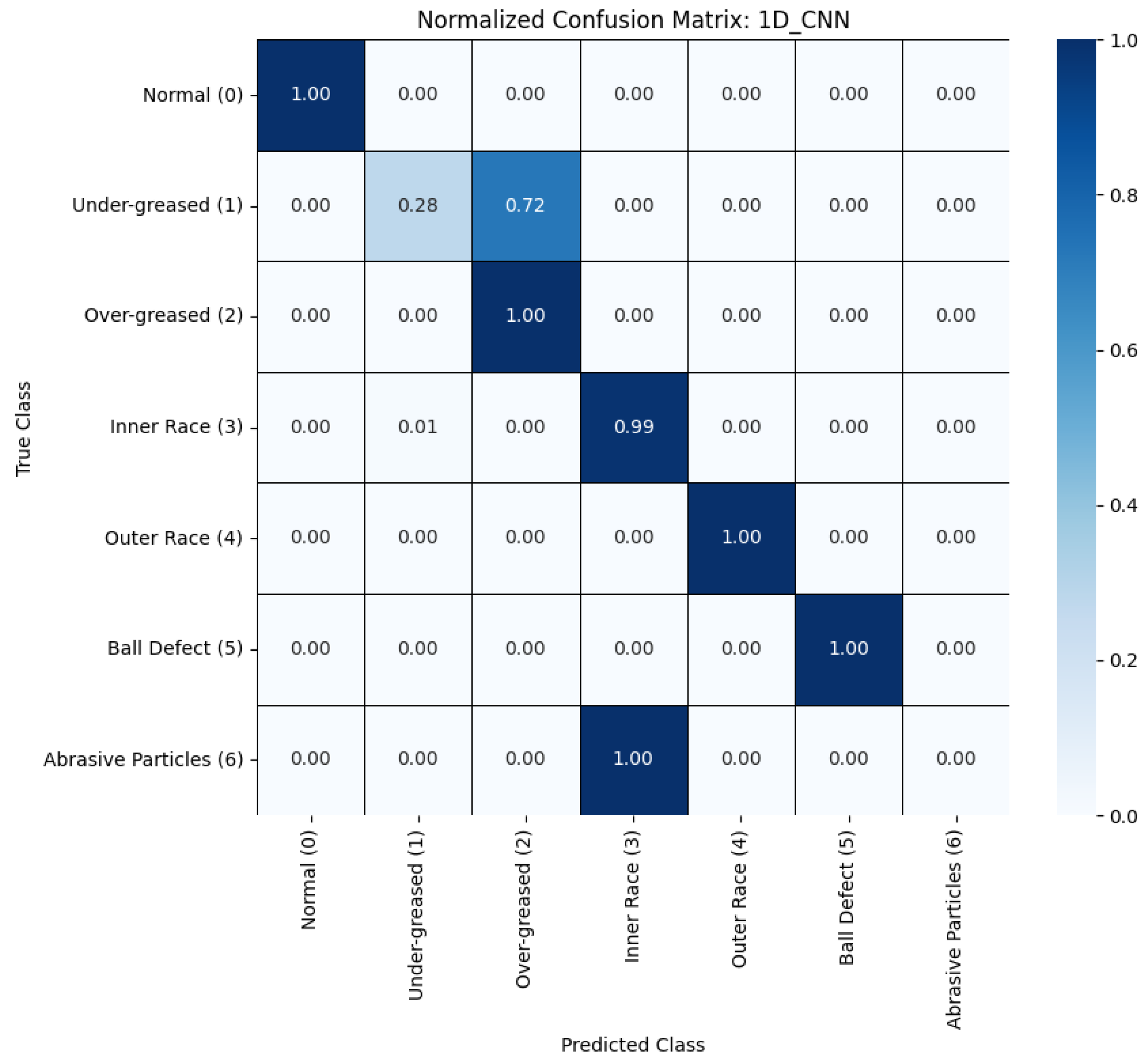

The most critical finding is the complete failure of both ANN-MLP (

Table 4) and 1D-CNN (

Table 5) to detect the Abrasive Particles (6) fault, yielding an F1-score of 0.0000. This challenging fault class represents a critical operational risk. In stark contrast, the ResNet-1D model (

Table 6) achieved a perfect F1-score of 1.0000 for this class, successfully resolving the most complex diagnostic task. This breakthrough justifies the architectural choice by delivering high confidence and robustness, essential for industrial PdM.

4.3. Confusion Matrices

Normalized confusion matrices, illustrating per-class prediction accuracy (Recall), are presented in

Figure 3 for the ANN-MLP,

Figure 4 for the 1D-CNN, and

Figure 5 for the ResNet-1D. These matrices visually confirm the failure of the baseline models to detect Abrasive Particles (6) (showing a horizontal bar of misclassification) and the near-perfect diagonal classification achieved by the ResNet-1D model. Detailed ROC curve analysis for all models is provided in

Appendix B (

Figure A7,

Figure A8 and

Figure A9).

4.4. Statistical Significance Testing

To formally validate the architectural advantage, a paired

t-test was performed on the Macro F1-scores obtained from

bootstrap samples, comparing the two best convolutional architectures, as shown in

Table 7.

The resulting t-statistic of t = 592.702 and p-value of () indicate a statistically significant difference in performance. This result formally validates the architectural superiority of ResNet-1D over the simpler 1D-CNN, adhering to high standards of methodological rigor.

4.5. Interpretability Analysis with SHAP

SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) was applied to the top-performing ResNet-1D model to provide crucial interpretability for the most critical fault class. The analysis focused on the Abrasive Particles (6) fault, whose successful detection is the key contribution of this work.

4.5.1. Global Feature Importance

Figure 6 presents the global feature importance based on the mean absolute SHAP value for the Abrasive Particles (6) class. This analysis confirms that Crest_1 (Crest Factor from Sensor 1) is the dominant and most influential feature, justifying the model’s reliance on physically relevant indicators of impulsive events.

4.5.2. Beeswarm Plot

Figure 7 provides the SHAP Beeswarm Summary Plot, showing the magnitude and direction of influence for each feature on the Abrasive Particles (6) prediction score. High values of Crest_1 (red dots) strongly correlate with a high positive SHAP value, pushing the model toward predicting the Abrasive Particles state.

4.5.3. Dependence Plot

Figure 8 is the Dependence Plot, illustrating the non-linear relationship between the value of the most important feature (Crest_1) and its impact on the model output (SHAP value). The plot shows a clear threshold: when Crest_1 exceeds a certain value, the SHAP value increases sharply, strongly confirming the prediction of the Abrasive Particles fault.

4.5.4. Local Explanation

Figure 9 shows the SHAP Waterfall Plot, presenting a local explanation for a single, critical prediction of the Abrasive Particles (6) fault. The plot demonstrates how the high value of Crest_1 acts as the primary driver (red bar) pushing the model toward the correct diagnosis. This interpretability layer ensures that the model’s decisions align with physical principles, improving trust and transparency in industrial applications.

5. Discussion

5.1. Architectural Necessity and Convolutional Feature Abstraction

The rigorous statistical comparison proved that the ResNet-1D architecture’s ability to learn hierarchical and deeply correlated patterns provides a significant and robust advantage over both the ANN-MLP and the simpler 1D-CNN. This architectural sophistication was not merely incremental; it was empirically necessary to solve the most complex diagnostic task: achieving a perfect F1-score of 1.0000 for the Abrasive Particles (6) fault, which both baseline models completely failed to detect (F1 = 0.0000).

This finding serves as a strong empirical validation for our methodological choice: applying convolution to a logically ordered statistical feature vector. The residual blocks within ResNet-1D effectively extract the latent structural relationships between physically grouped features (e.g., V-RMS, a-RMS, Crest Factor from Sensor 1), demonstrating that this approach is not only a viable, but a superior high-performance, low-latency compromise for industrial edge deployment compared to processing raw signals.

5.2. Trust and Transparency: Physical Validation Through SHAP

The integration of SHAP is fundamental for overcoming the resistance to “black-box” DL models in critical engineering applications [

10]. By independently confirming that Crest_1 is the dominant predictor for the Abrasive Particles (6) fault, the SHAP analysis physically validates the model’s intelligence against established domain knowledge. A high Crest Factor is the known physical signature of impact or abrasive wear, making the model’s reliance on this feature highly plausible.

This transparency is essential for industrial decision-makers, who require certainty that diagnostic alarms are based on physically meaningful metrics rather than abstract model artifacts [

10]. Furthermore, the insights gained from SHAP can be used to optimize sensor placement and feature engineering in future PdM implementations [

22].

5.3. Methodological Significance and Rigor

The statistical confirmation of the ResNet-1D’s superiority (

t-statistic = 592.702,

) using a paired

t-test on 100 bootstrap samples is a crucial methodological advancement. This rigor eliminates the ambiguity inherent in relying on single point measurements and provides objective, statistically proven evidence of the architectural advantage, thus raising the standards for model comparisons in FDD literature. This study therefore significantly refines the diagnostic engine developed in the original IoT framework by Vlachou et al. (2025) [

2], delivering a solution that is demonstrably more reliable, statistically validated, and fully interpretable for Industry 4.0 applications.

6. Limitations

Despite its achievements, this work faces several limitations inherent to most BFD studies:

Dataset Dependency: The analysis was performed on data collected in controlled laboratory conditions. Real-world variables, such as varying loads, speeds, and complex industrial noise, may affect generalization performance [

19].

Monosensory Analysis: The model relies solely on vibration and temperature features. Multimodal fusion, incorporating data such as motor current [

3], acoustic emission, or other process parameters, is often required for maximal robustness in complex environments [

3].

Computational Constraints: The superior performance of the ResNet-1D model comes at the cost of higher computational demands compared to the baseline ANN-MLP. While the input feature vector is compact, the increased complexity of the residual blocks poses challenges for immediate, optimized deployment on highly resource-constrained edge devices.

7. Future Work

Future research should focus on operationalizing the findings and addressing current limitations:

Validating on Diverse Datasets: The ResNet-1D model should be cross-validated on diverse, public industrial datasets (e.g., CWRU or Paderborn) to confirm its generalizability across different operational contexts [

3]. Techniques like transfer learning can be explored for faster adaptation to new machine types [

21].

Optimization for Edge Computing: Comprehensive investigation into model optimization techniques, such as quantization (reducing precision to 8-bit integers) or knowledge distillation (training a simpler network to mimic the ResNet-1D), is necessary to create a lightweight version of the high-performing model capable of real-time operation on resource-limited edge hardware, fulfilling the promise of the IoT framework.

Using SHAP for Feature Engineering: The SHAP results, highlighting the dominance of Crest_1 for the critical fault, should be leveraged to systematically simplify the input feature vector by eliminating the least important features, thereby streamlining data acquisition and reducing implementation costs [

23].

Extending XAI Techniques: Incorporating advanced XAI methods beyond SHAP, such as LIME, or visual tools like Frequency Activation Maps (FAMs) [

25], can provide deeper insights into the model’s classification criteria, further increasing transparency [

26].

8. Conclusions

This study introduced an explainable deep learning framework for rolling element bearing fault diagnosis, rigorously comparing ANN-MLP, 1D-CNN, and the ResNet-1D architectures on a statistical feature vector. The study established two key findings:

The ResNet-1D model achieved statistically significant superiority () over the simpler models, and crucially, was the only architecture capable of detecting the critical Abrasive Particles (6) fault (F1 = 1.0000), demonstrating its necessity for industrial-grade robustness.

SHAP analysis provided interpretable insights, physically validating the model by confirming that its decisions align with established vibration diagnostics principles. The analysis highlighted Crest_1 as the dominant feature for the critical abrasive fault.

By combining a high-performance, robust deep learning architecture with Explainable AI and rigorous statistical validation, this research delivers a solid foundation for trustworthy predictive maintenance solutions, thereby meeting the key engineering requirements for reliability and transparency in the Industry 4.0 era.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at:

https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/electronics14244875/s1, Table S1:

01_preprocess_data.py (Performs data cleaning, Z-score standardization, and stratified data splitting); Table S2:

02.1_ANN-MLP_training.py (Implements and trains the baseline ANN-MLP model); Table S3:

02.2_1D-CNN_training.py (Implements and trains the simple 1D-CNN model); Table S4:

02.3_ResNet-1D_training.py (Implements and trains the statistically superior ResNet-1D model); Table S5:

03_interpret_SHAP.py (Performs post hoc interpretability analysis using the SHAP framework on the ResNet-1D model).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.P., M.P. and D.F.; methodology, L.P.; software, L.P.; validation, L.P., M.P. and D.F.; formal analysis, L.P., M.P. and D.F.; investigation, L.P., M.P. and D.F.; resources, L.P.; data curation, L.P.; writing—original draft preparation, L.P.; writing—review and editing, L.P., M.P. and D.F.; visualization, L.P.; supervision, L.P.; project administration, L.P., M.P. and D.F.; funding acquisition, M.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Slovak Research and Development Agency under the Contract no. APVV-22-0524.

Data Availability Statement

The data analyzed in this study are publicly available in an open-access repository. The dataset, titled “Vibrations signals of a ball bearing fault during different operating conditions”, can be found at Zenodo via the following Digital Object Identifier (DOI):

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.16842422 (accessed on 26 November 2025).

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A. Model Training History and Dynamics

This appendix presents the training dynamics for all three deep learning models, illustrating convergence behavior and generalization performance over the epochs.

Appendix A.1. Artificial Neural Network–Multilayer Perceptron (ANN-MLP)

Figure A1.

ANN-MLP Training and Validation Loss Curve.

Figure A1.

ANN-MLP Training and Validation Loss Curve.

Figure A2.

ANN-MLP Training and Validation Accuracy Curve.

Figure A2.

ANN-MLP Training and Validation Accuracy Curve.

Appendix A.2. One-Dimensional Convolutional Neural Network (1D-CNN)

Figure A3.

1D-CNN Training and Validation Loss Curve.

Figure A3.

1D-CNN Training and Validation Loss Curve.

Figure A4.

1D-CNN Training and Validation Accuracy Curve.

Figure A4.

1D-CNN Training and Validation Accuracy Curve.

Appendix A.3. Residual Network–1D (ResNet-1D)

Figure A5.

ResNet-1D Training and Validation Loss Curve.

Figure A5.

ResNet-1D Training and Validation Loss Curve.

Figure A6.

ResNet-1D Training and Validation Accuracy Curve.

Figure A6.

ResNet-1D Training and Validation Accuracy Curve.

These figures demonstrate stable convergence and minimal signs of overfitting for the ResNet-1D architecture, indicating its robustness in learning the complex feature patterns necessary for the advanced fault diagnosis task.

Appendix B. ROC Curve Analysis

Figure A7,

Figure A8 and

Figure A9 present multi-class ROC curves for ANN-MLP, 1D-CNN, and ResNet-1D models, respectively, along with macro-average AUC values. The curves for ANN-MLP and 1D-CNN show degradation in specific classes, contributing to their lower macro AUC scores, while the ResNet-1D curve confirms near-perfect discrimination across all fault classes.

The ResNet-1D model, with a Macro AUC of 0.9998, demonstrates near-perfect discrimination capability across all fault classes, a significant improvement over the baseline models.

Figure A7.

Multi-class ROC curves for ANN-MLP. The Macro-average AUC is 0.8830.

Figure A7.

Multi-class ROC curves for ANN-MLP. The Macro-average AUC is 0.8830.

Figure A8.

Multi-class ROC curves for 1D-CNN. The Macro-average AUC is 0.8444.

Figure A8.

Multi-class ROC curves for 1D-CNN. The Macro-average AUC is 0.8444.

Figure A9.

Multi-class ROC curves for ResNet-1D. The Macro-average AUC is 0.9998.

Figure A9.

Multi-class ROC curves for ResNet-1D. The Macro-average AUC is 0.9998.

Appendix C. Computational Environment and Library Versions

All experiments and analyses were conducted in a Python 3.11.9 environment to ensure consistency and reproducibility. To maintain transparency and allow full replication of the workflow, the versions of the key scientific and machine learning packages employed in the study are summarized in

Table A1.

Table A1.

Versions of Python libraries used in the computational environment.

Table A1.

Versions of Python libraries used in the computational environment.

| Package | Description | Version |

|---|

| pandas | Data manipulation and tabular processing | v2.3.3 |

| numpy | Core numerical computations and array operations | v2.3.5 |

| scikit-learn | Machine learning algorithms and evaluation metrics | v1.7.2 |

| matplotlib | Visualization and plotting utilities | v3.10.7 |

| seaborn | Statistical data visualization | v0.13.2 |

| torch | Deep learning framework for LSTM Autoencoder | v2.10.0.dev20251124+cu128 |

| shap | Post hoc interpretability using SHAP values | v0.50.0 |

This appendix ensures full reproducibility and aligns with best practices for scientific reporting.

References

- Choi, K.; Yi, J.; Park, C.; Yoon, S. Deep Learning for Anomaly Detection in Time-Series Data: Review, Analysis, and Guidelines. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 120043–120065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlachou, V.I.; Karakatsanis, T.S.; Vologiannidis, S.D.; Efstathiou, D.E.; Karapalidou, E.L.; Antoniou, E.N.; Efraimidis, A.E.; Balaska, V.E.; Vlachou, E.I. Intelligent Fault Diagnosis of Ball Bearing Induction Motors for Predictive Maintenance Industrial Applications. Machines 2025, 13, 902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddique, M.F.; Saleem, F.; Umar, M.; Kim, C.H.; Kim, J.M. A Hybrid Deep Learning Approach for Bearing Fault Diagnosis Using Continuous Wavelet Transform and Attention-Enhanced Spatiotemporal Feature Extraction. Sensors 2025, 25, 2712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, C.; Tang, D.; Zhu, H.; Nie, Q. A Novel Predictive Maintenance Method Based on Deep Adversarial Learning in the Intelligent Manufacturing System. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 49557–49575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullah, A.T.; Hussein, H.M.; Sabeeh, R.S.; Hussien, M.J. A Comprehensive Review of Machine Learning Algorithms for Fault Diagnosis and Prediction in Rotating Machinery. J. Univ. Babylon Eng. Sci. 2025, 33, 110–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mushtaq, S.; Islam, M.M.M.; Sohaib, M. Deep Learning Aided Data-Driven Fault Diagnosis of Rotatory Machine: A Comprehensive Review. Energies 2021, 14, 5150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.C.; Liu, Z.; Yang, G.; Wu, C.C.; Ye, Q. An Improved Fault Diagnosis Using 1D-Convolutional Neural Network Model. Electronics 2021, 10, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Zha, J.; Cai, Z.; Wu, M. Predictive modelling of surface roughness in precision grinding based on hybrid algorithm. Cirp J. Manuf. Sci. Technol. 2025, 59, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, S.; Chaudhuri, R.; Vrontis, D.; Papadopoulos, T. Examining the impact of deep learning technology capability on manufacturing firms: Moderating roles of technology turbulence and top management support. Ann. Oper. Res. 2024, 339, 163–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.D.; Vu, T.T.; Danh, T.B.D.; Pham, T.H.; Nguyen, P.D. Explainable AI-Enhanced Fault Diagnosis for Rotating Machinery: A SHAP-Based Framework for Transparent Decision Making. In Proceedings of the 2025 24th International Symposium on Communications and Information Technologies (ISCIT), Hanoi, Vietnam, 16–18 October 2025; pp. 103–109, ISSN 2643-6175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.; Yao, Z.; Verbeke, M.; Karsmakers, P.; Gorissen, B.; Reynaerts, D. Data-driven models with physical interpretability for real-time cavity profile prediction in electrochemical machining processes. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2025, 160, 111807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Z.; Wu, M.; Qian, J.; Reynaerts, D. Intelligent discharge state detection in micro-EDM process with cost-effective radio frequency (RF) radiation: Integrating machine learning and interpretable AI. Expert Syst. Appl. 2025, 291, 128607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerr, K.F.; Meisner, A.; Thiessen-Philbrook, H.; Coca, S.G.; Parikh, C.R. RiGoR: Reporting guidelines to address common sources of bias in risk model development. Biomark. Res. 2015, 3, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vlachou, V.; Karakatsanis, T.; Vologiannidis, S.; Efstathiou, D.; Elisavet, K.; Antoniou, E.; Efraimidis, A.; Balaska, V.; Vlachou, E. Vibrations Signals of a Ball Bearing Fault During Different Operating Conditions; Dataset (Version v1); Zenodo: Geneva, Switzerland, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leite, D.; Andrade, E.; Rativa, D.; Maciel, A.M.A. Fault Detection and Diagnosis in Industry 4.0: A Review on Challenges and Opportunities. Sensors 2025, 25, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Addula, S.R.; Tyagi, A.K.; Naithani, K.; Kumari, S. Blockchain-Empowered Internet of Things (IoTs) Platforms for Automation in Various Sectors. In Artificial Intelligence-Enabled Digital Twin for Smart Manufacturing; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2024; pp. 443–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilk-Jakubowski, J.L.; Pawlik, L.; Frej, D.; Wilk-Jakubowski, G. The Evolution of Machine Learning in Vibration and Acoustics: A Decade of Innovation (2015–2024). Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 6549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutai, B. The Importance of Skewness and Kurtosis in EDA. DEV Community, 2025. Available online: https://dev.to/brenda_mutai_8a282e86666a/the-importance-of-skewness-and-kurtosis-in-eda-5c07 (accessed on 26 November 2025).

- Kim, J.H.T.; Kim, H. Estimating Skewness and Kurtosis for Asymmetric Heavy-Tailed Data: A Regression Approach. Mathematics 2025, 13, 2694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawlik, L.; Wilk-Jakubowski, J.L.; Frej, D.; Wilk-Jakubowski, G. Applications of Computational Mechanics Methods Combined with Machine Learning and Neural Networks: A Systematic Review (2015–2025). Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 10816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chopra, P.; Kumar, H.; Yadav, S. PNN: A Novel Progressive Neural Network for Fault Classification in Rotating Machinery under Small Dataset Constraint. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2503.18263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Wu, M. Research on bearing fault diagnosis based on machine learning and SHAP interpretability analysis. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 41242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brusa, E.; Cibrario, L.; Delprete, C.; Di Maggio, L.G. Explainable AI for Machine Fault Diagnosis: Understanding Features’ Contribution in Machine Learning Models for Industrial Condition Monitoring. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 2038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, M.J.; Sohaib, M.; Kim, J.M. An Explainable AI-Based Fault Diagnosis Model for Bearings. Sensors 2021, 21, 4070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maged, A.; Haridy, S.; Shen, H. Explainable Artificial Intelligence Techniques for Accurate Fault Detection and Diagnosis: A Review. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2404.11597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latil, D.; Ngouna, R.H.; Medjaher, K.; Lhuisset, S. Vibration-based Data-driven Fault Diagnosis of Rotating Machines Operating Under Varying Working Conditions: A Review and Bibliometric Analysis. Int. J. Progn. Health Manag. 2025, 16, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).