Human–Robot Interaction for a Manipulator Based on a Neural Adaptive RISE Controller Using Admittance Model

Abstract

1. Introduction

- A dual-loop admittance-based control framework integrating RISE and RBFNN is developed to achieve robust and compliant interaction under uncertain dynamics.

- The proposed scheme achieves semi-global asymptotic tracking with bounded, continuous control inputs, without increasing control gain or requiring known disturbance bounds.

2. Preliminaries and Problem Formulation

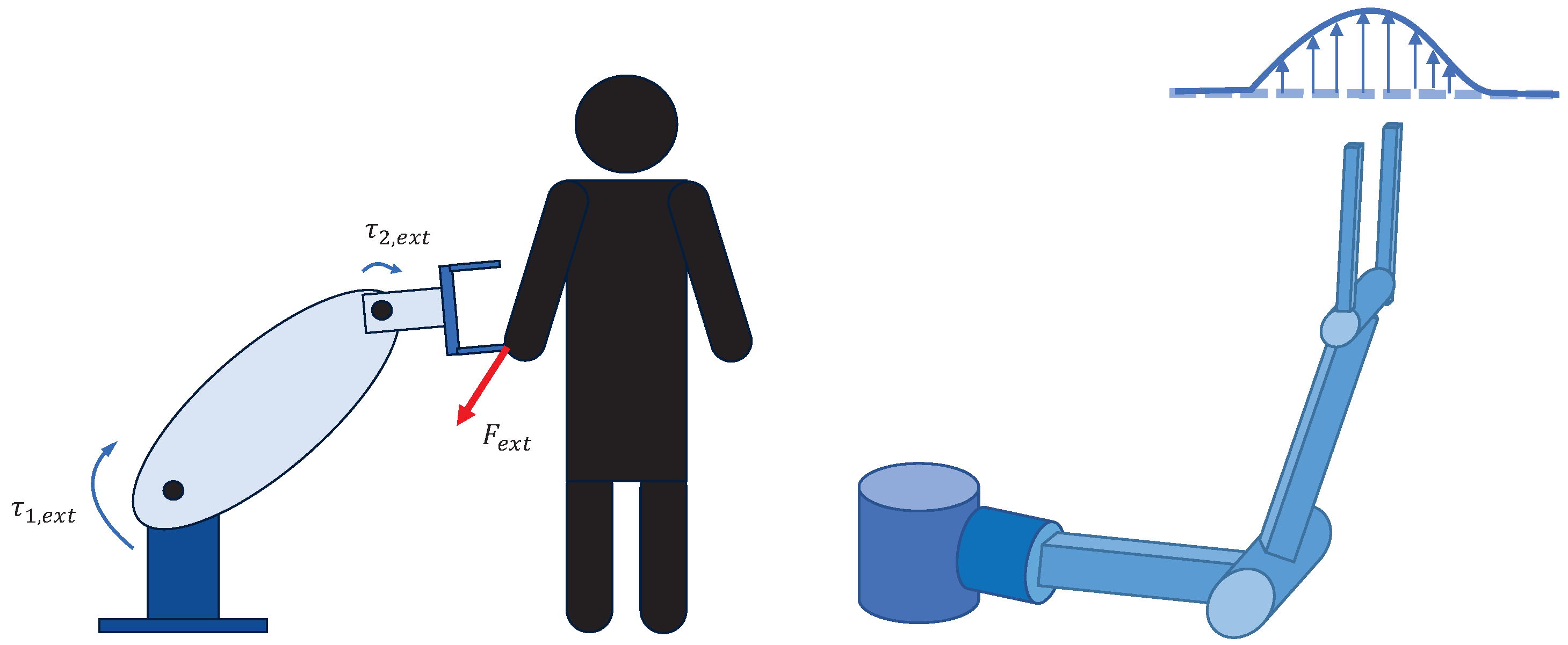

2.1. Problem Formulation

- Design a controller for the robot that enables smooth adaptation to human interactions, facilitating trajectory reshaping using admittance control. This ensures that the robot responds compliantly to human movements, thereby enhancing safety and user comfort during physical interaction.

- Develop a controller capable of robustly tracking trajectories generated by admittance control, even in the presence of model uncertainties. This includes uncertainties in the robot’s dynamics and the environment, ensuring reliable performance in real-world applications of pHRI.

2.2. Physical HRI Objective

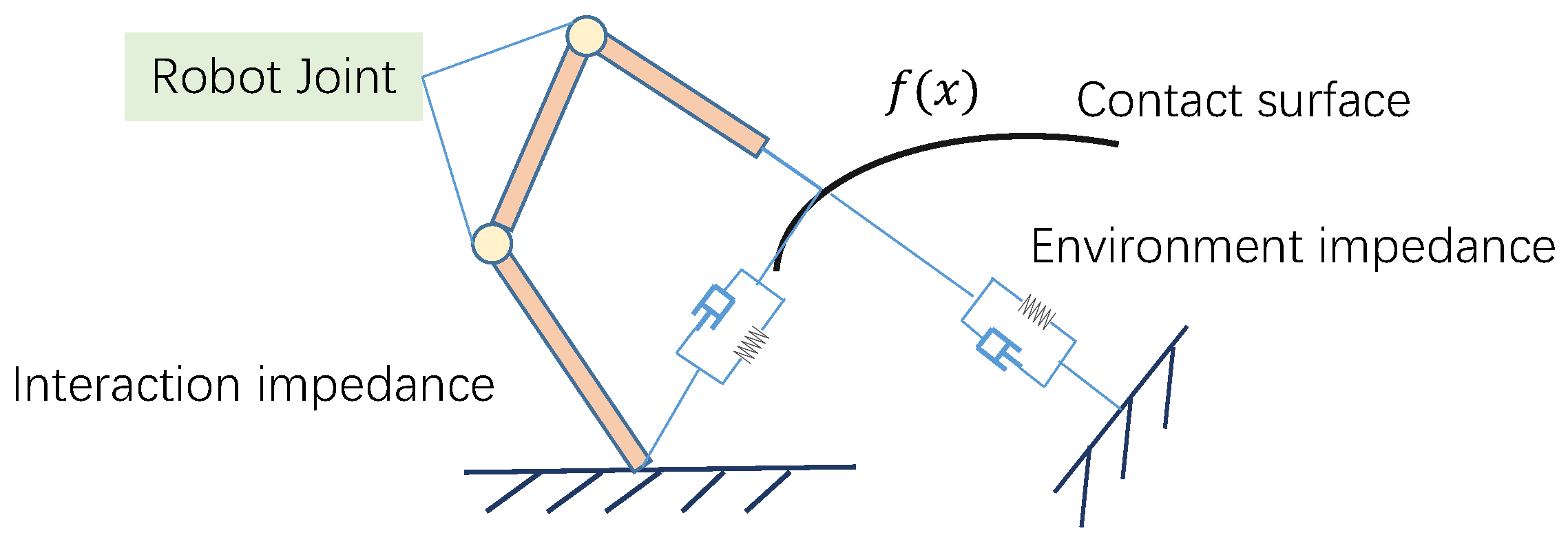

2.3. Dynamics Modeling of Manipulator System

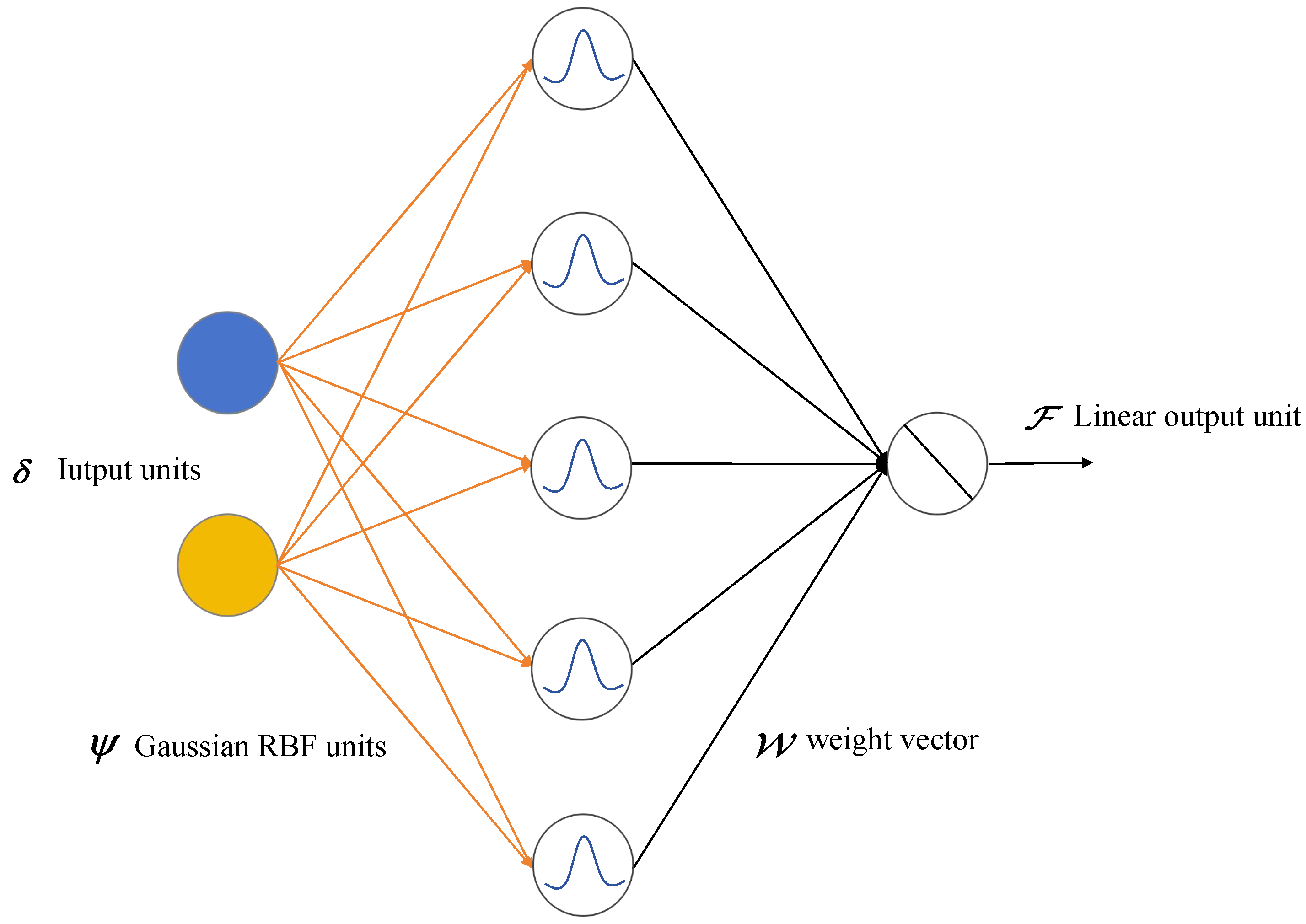

2.4. Neural Network Approximation

3. RBFNN Based Robust Integral Sign Error Dynamic Robot Control

3.1. Filtered Tracking Error Dynamics

3.2. RBFNN Approximation

3.3. Controller Design

4. Simulation

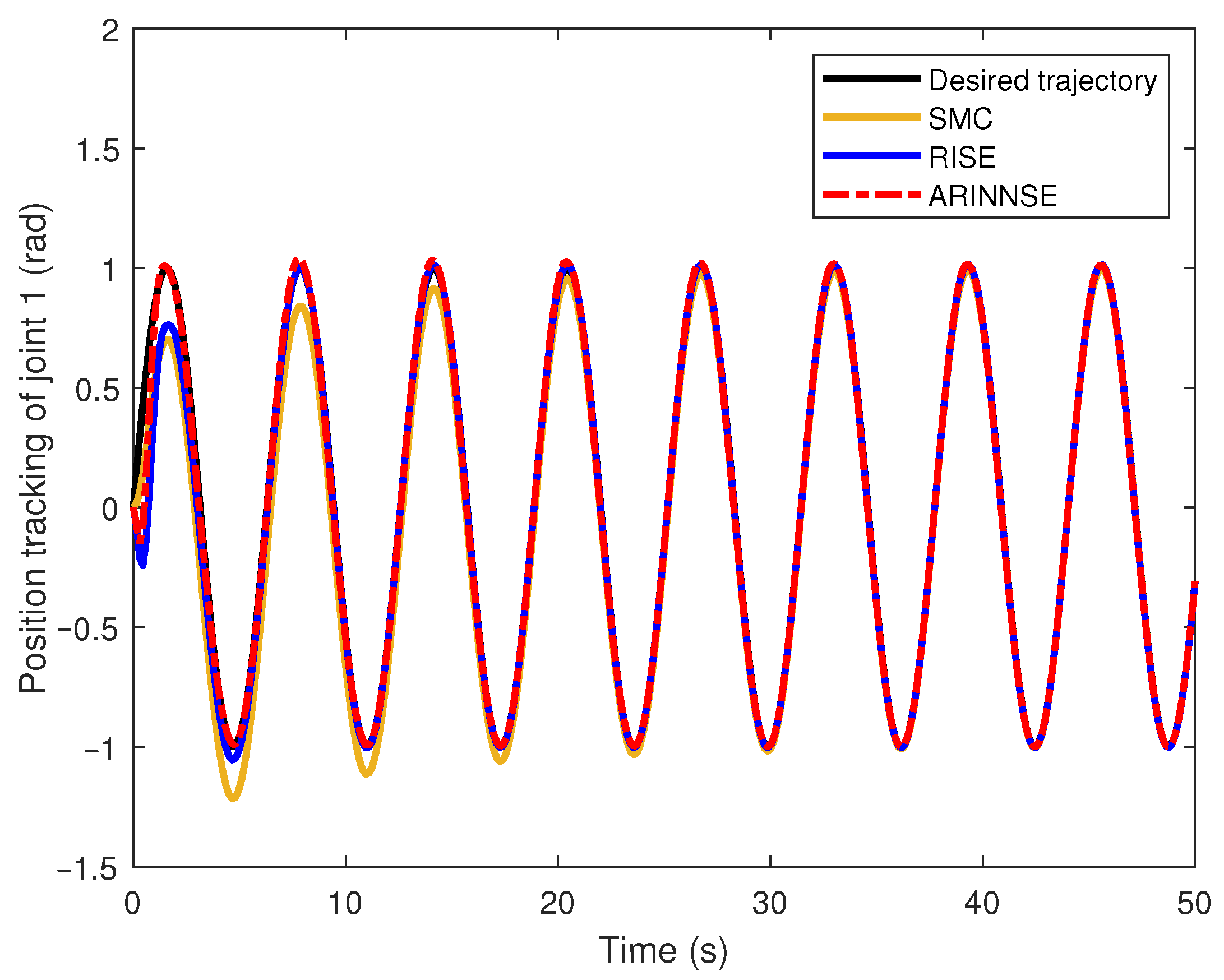

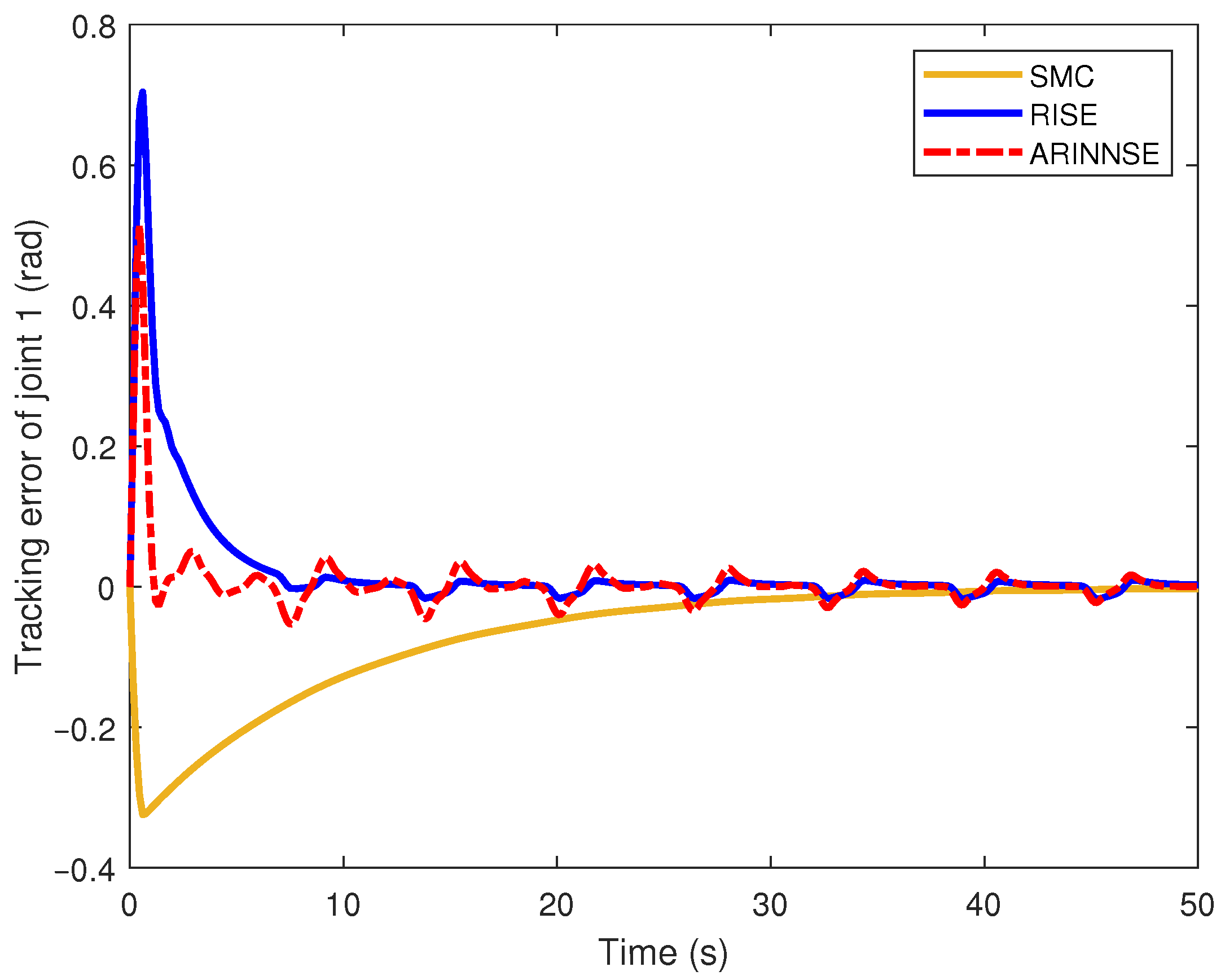

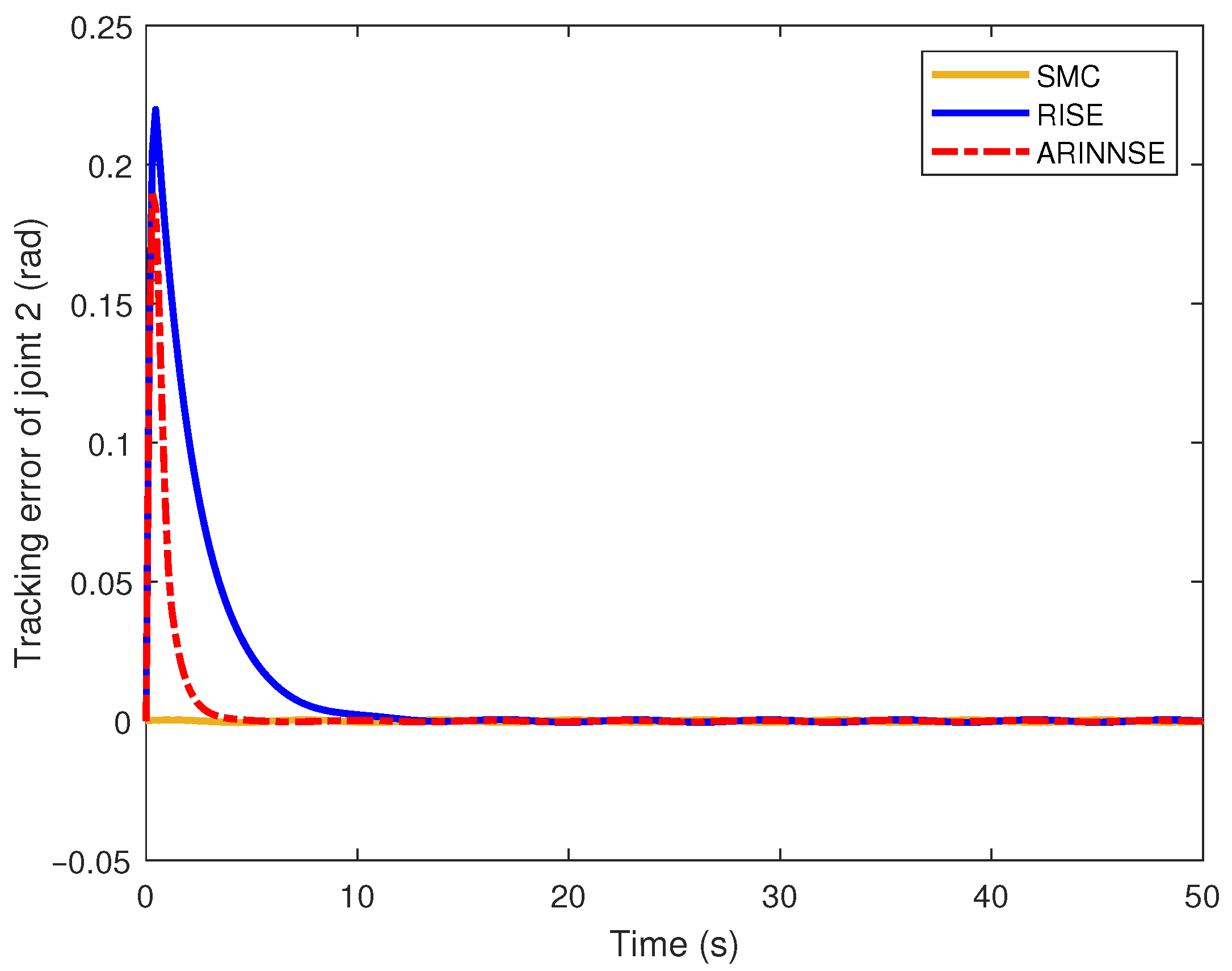

4.1. Tracking Performance Evaluation

4.2. Human–Robot Interaction Test

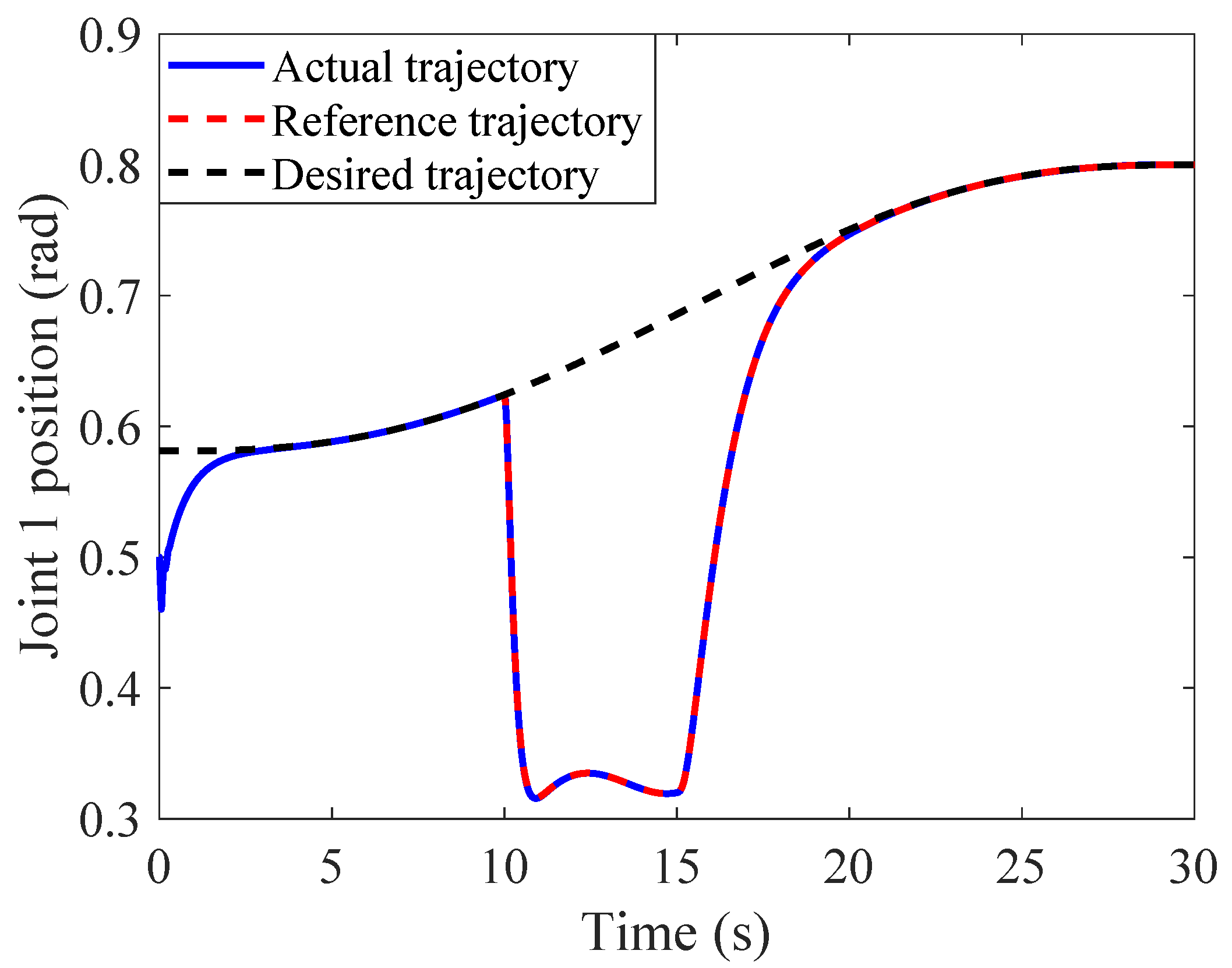

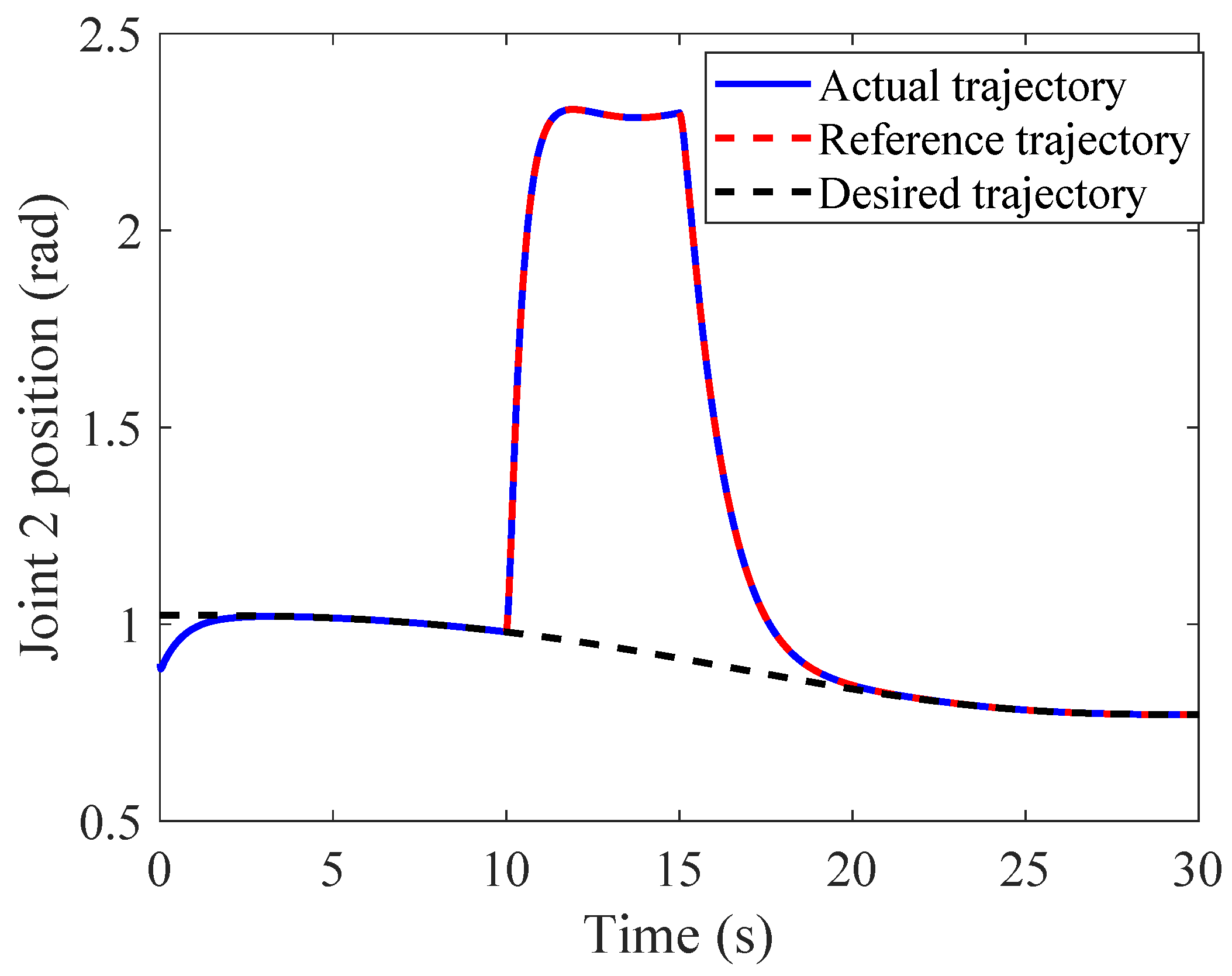

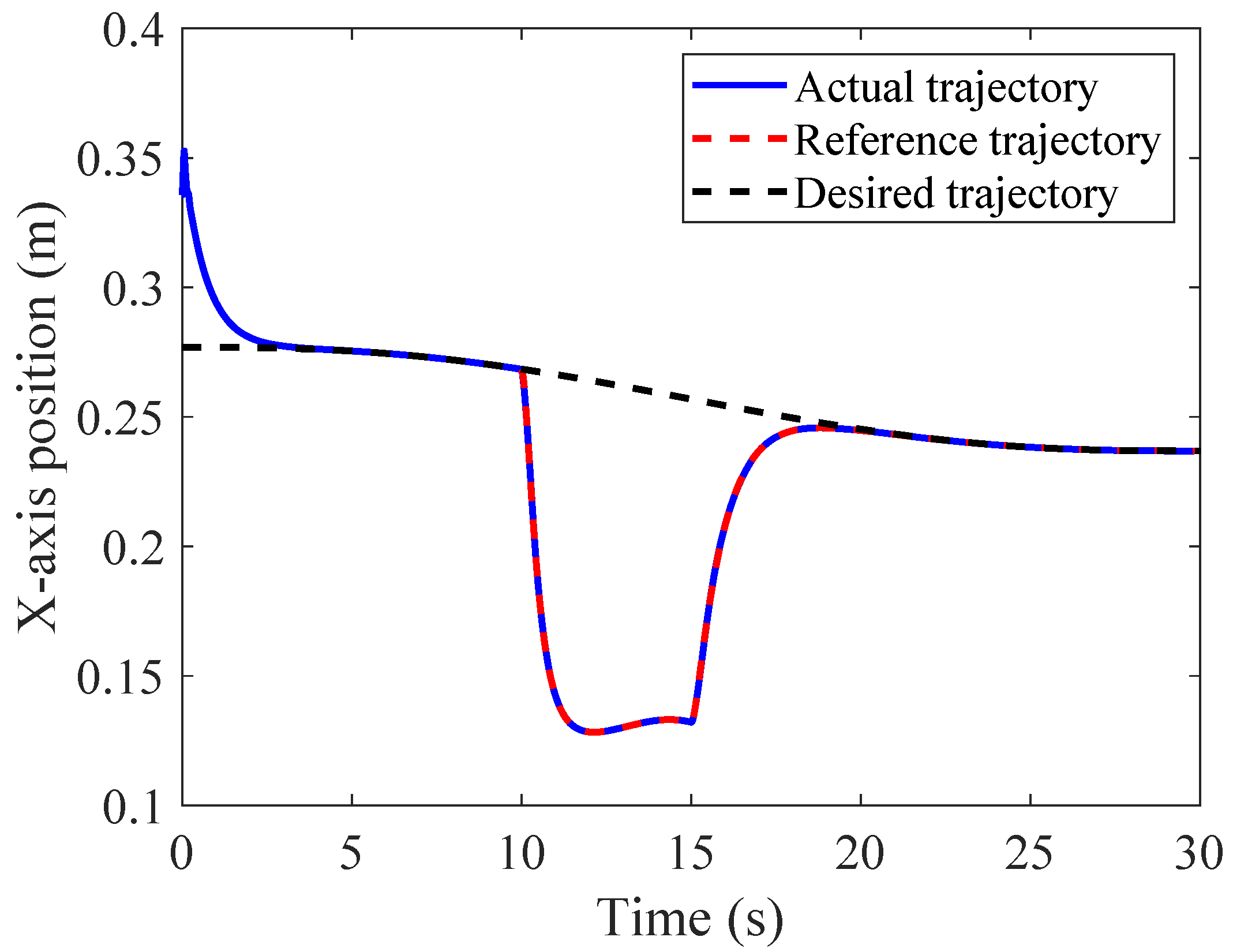

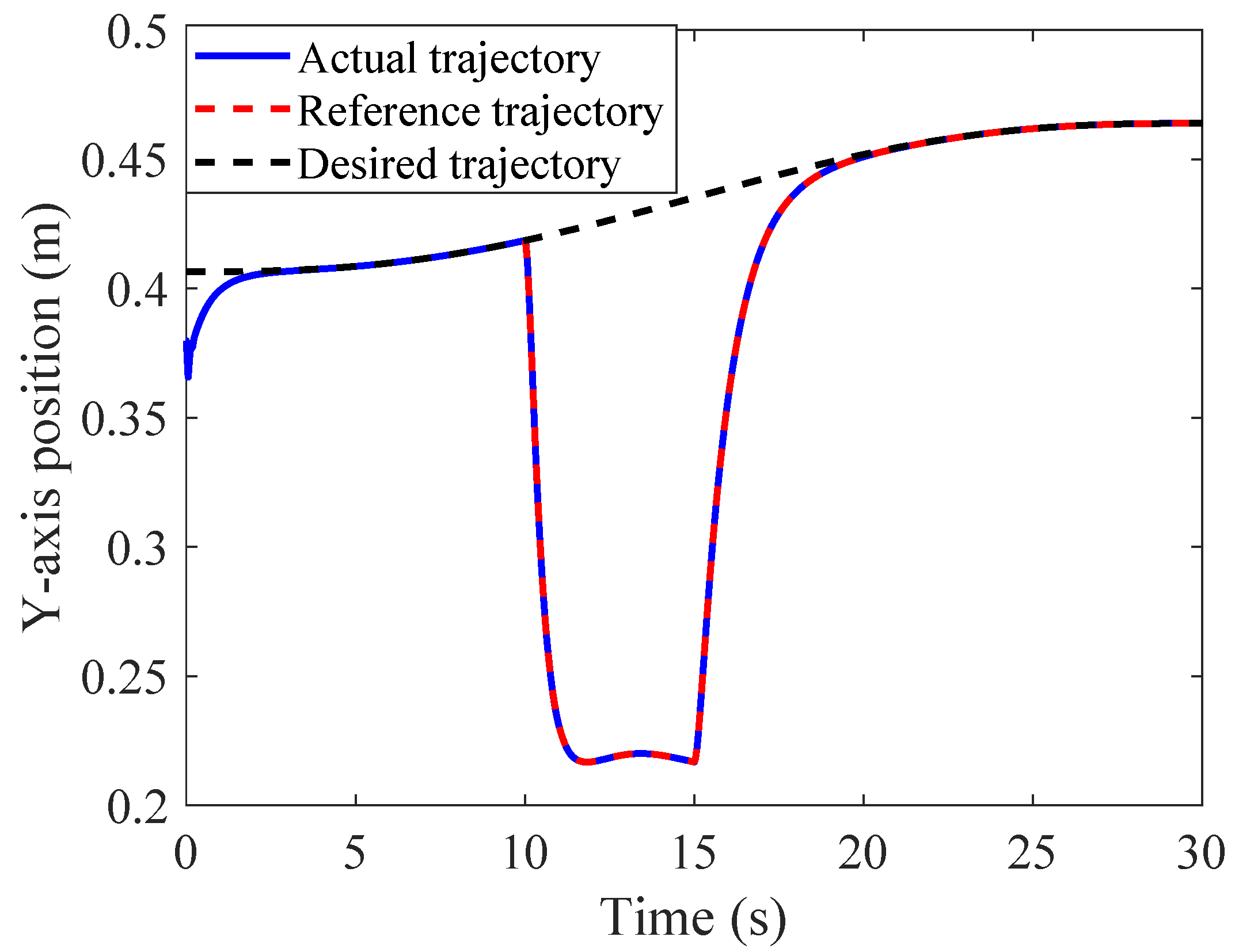

4.2.1. Tracking Performance in Joint and Cartesian Space

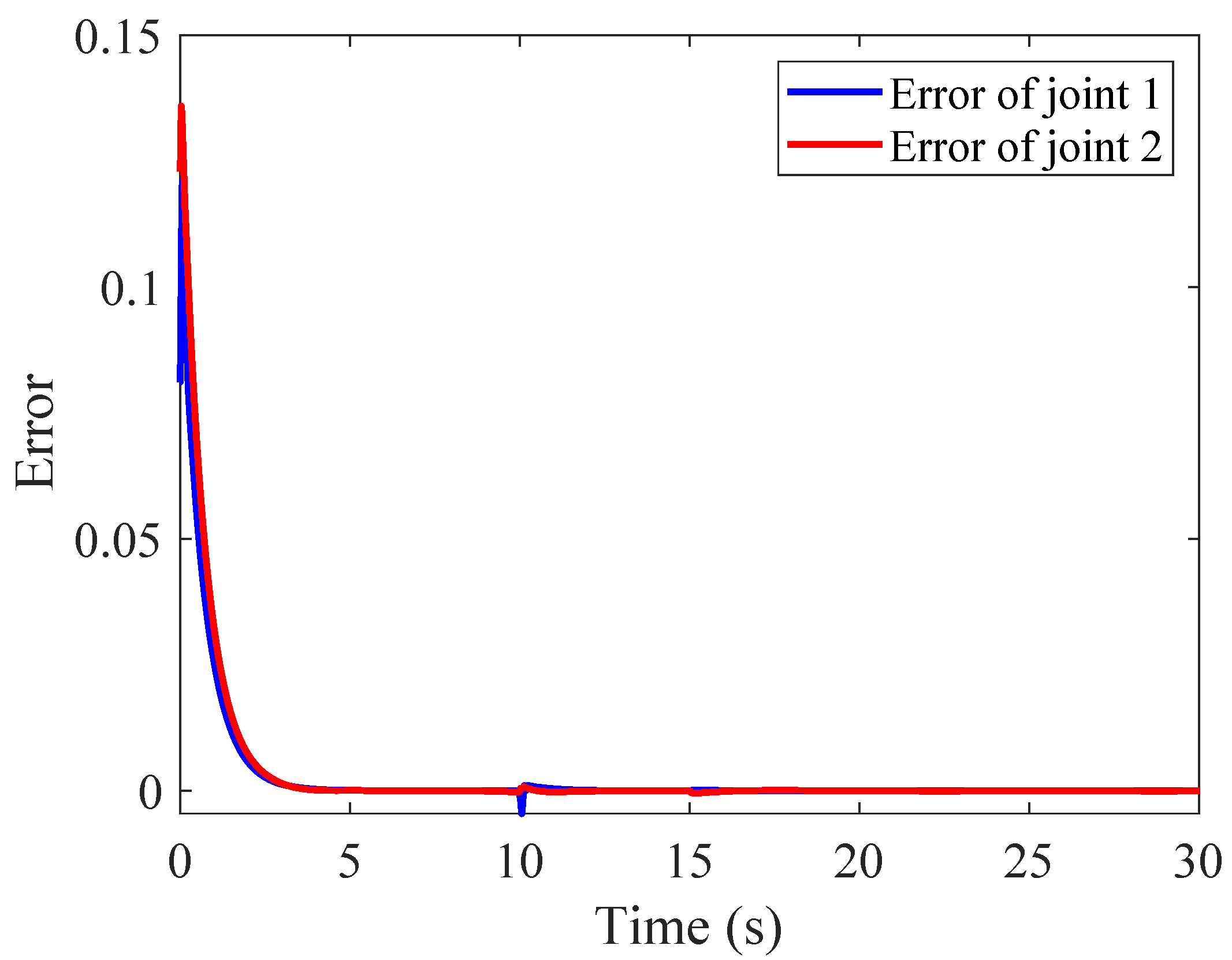

4.2.2. Tracking Error and Stability

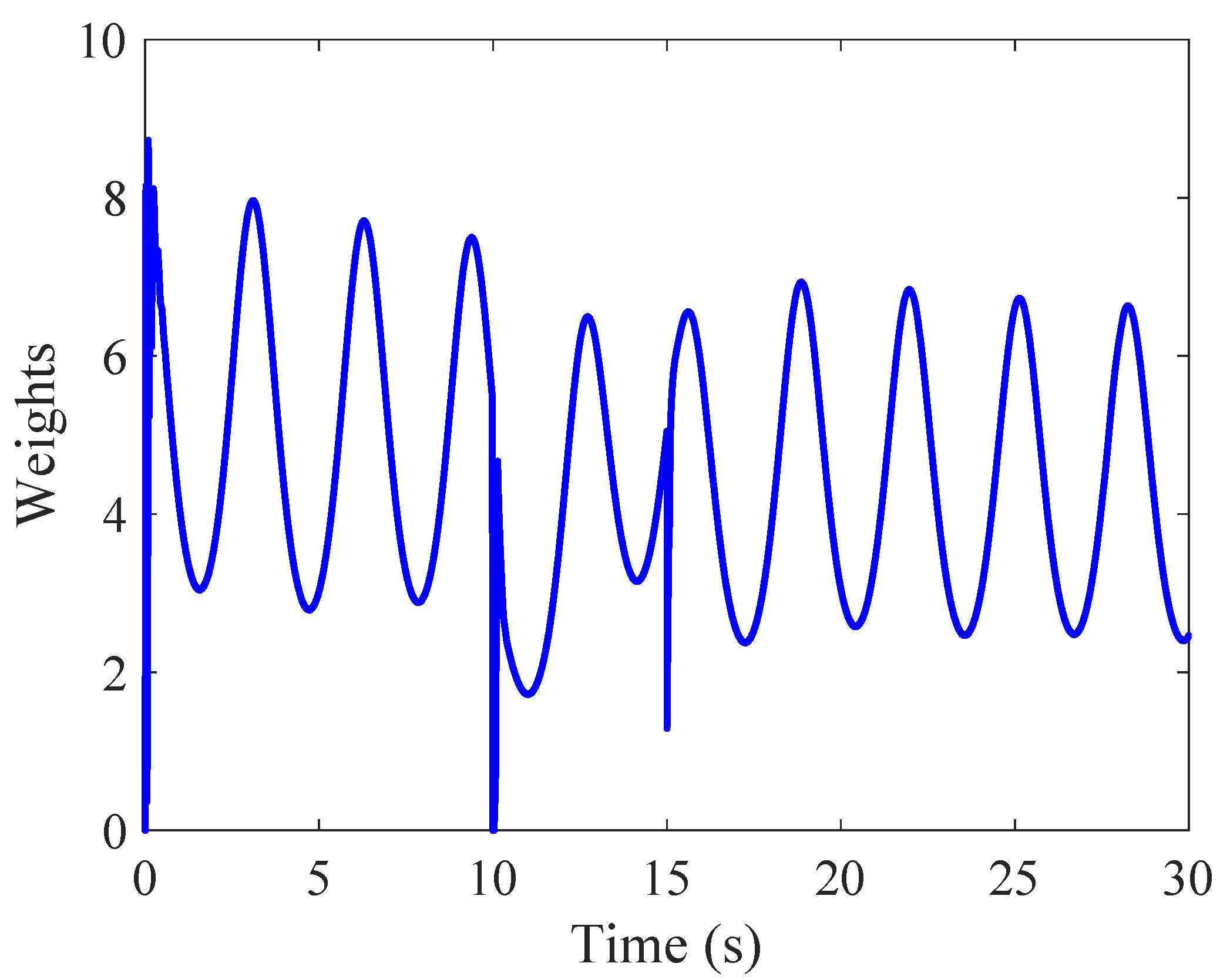

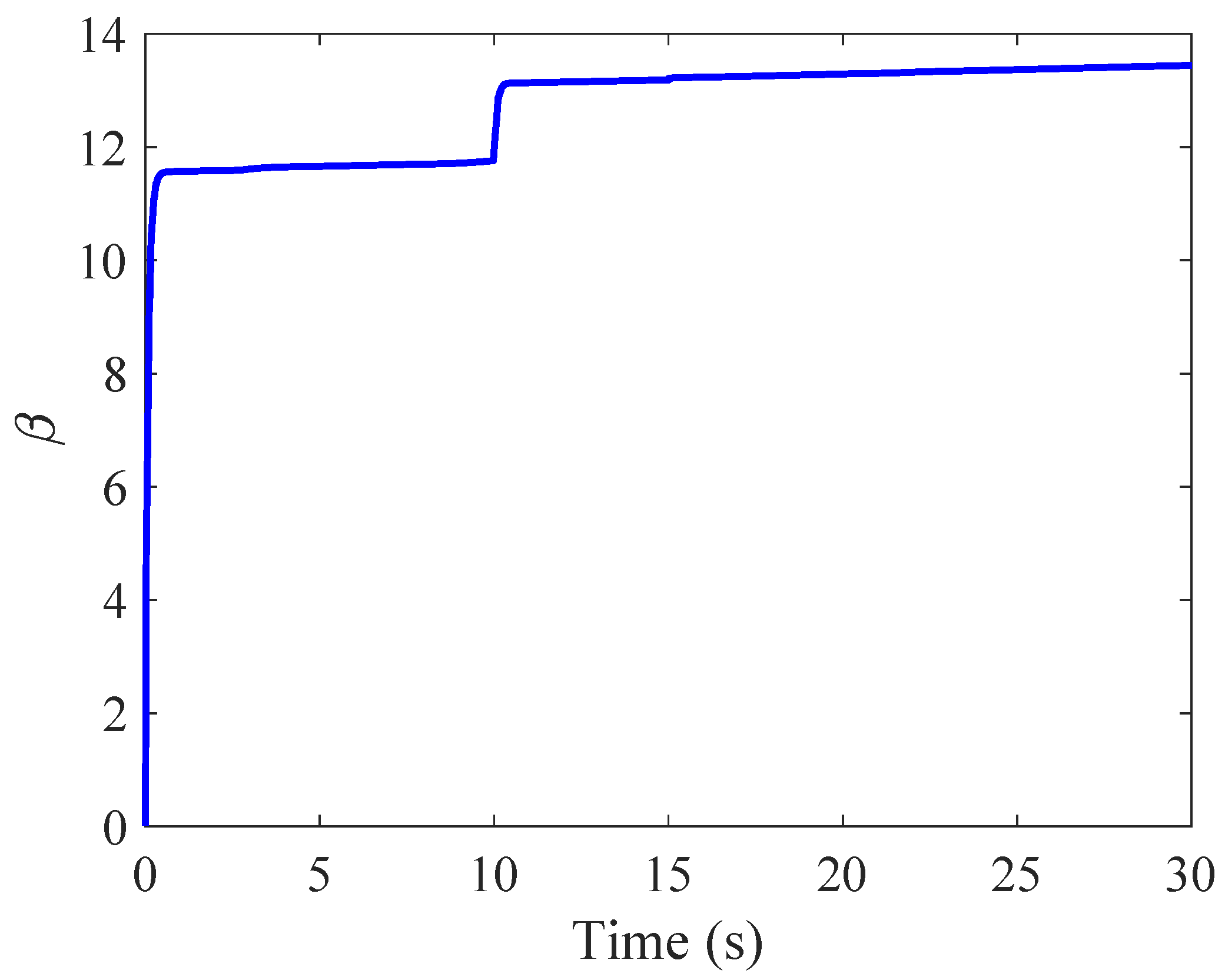

4.2.3. NN Weights and Adaptive Term

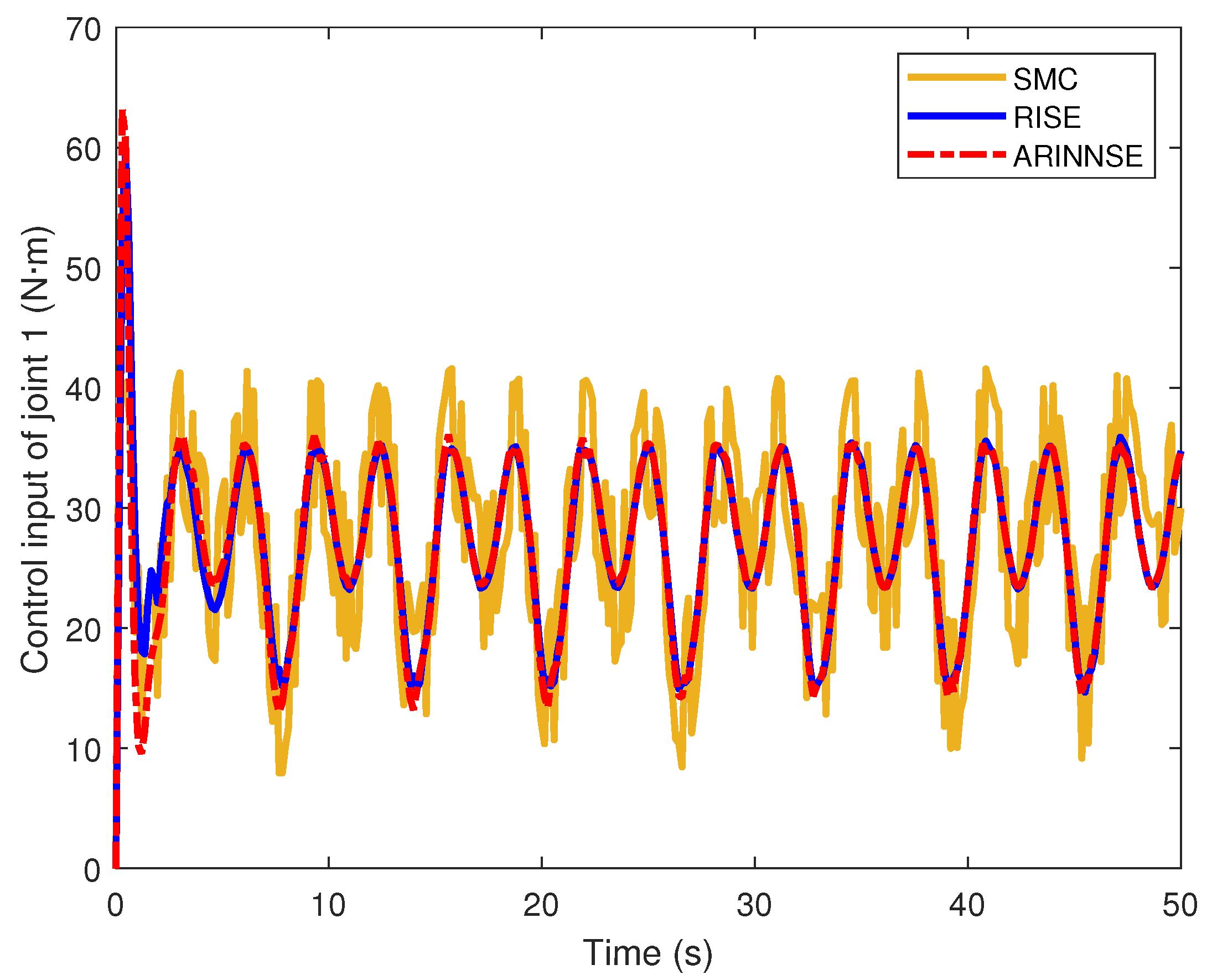

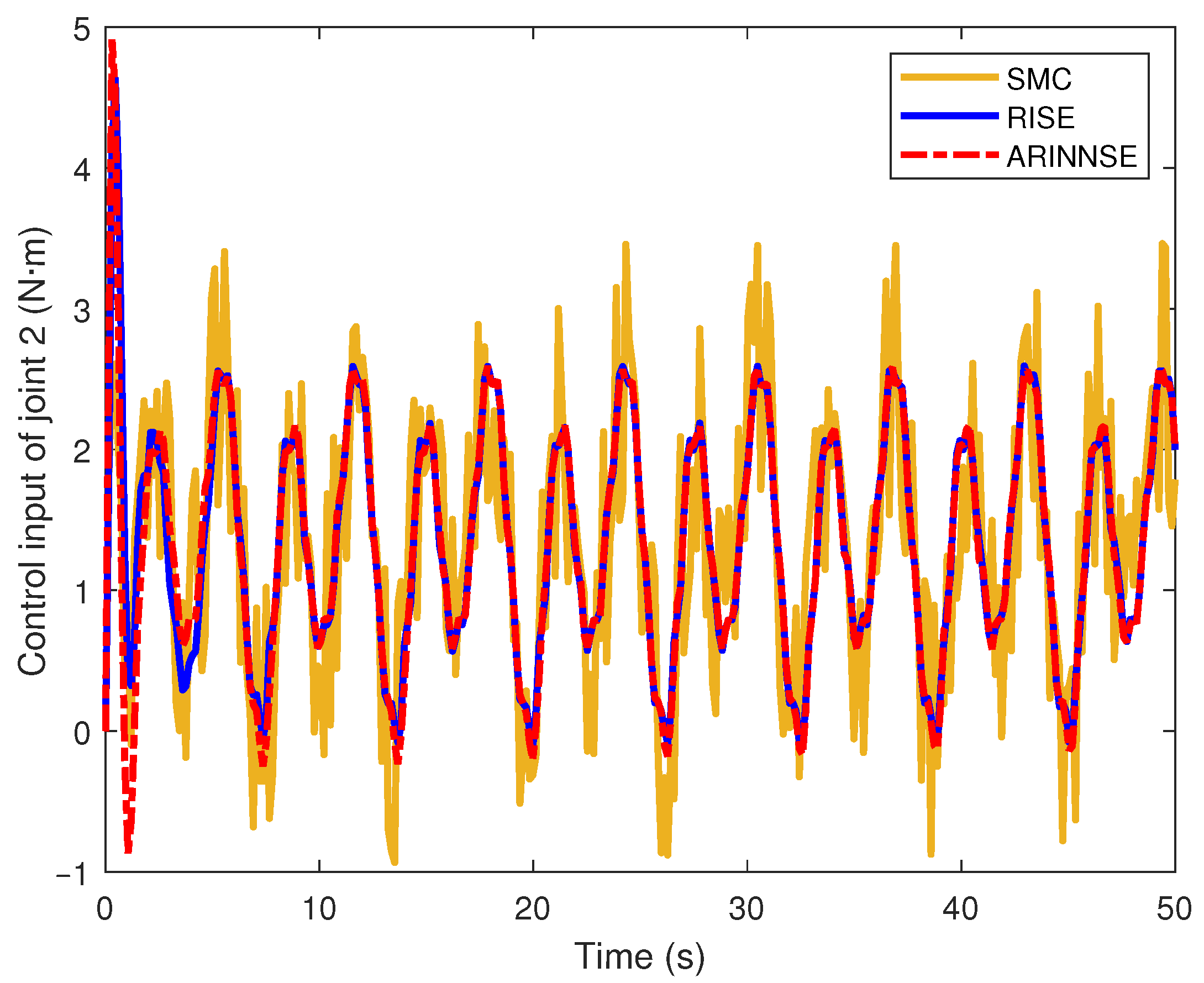

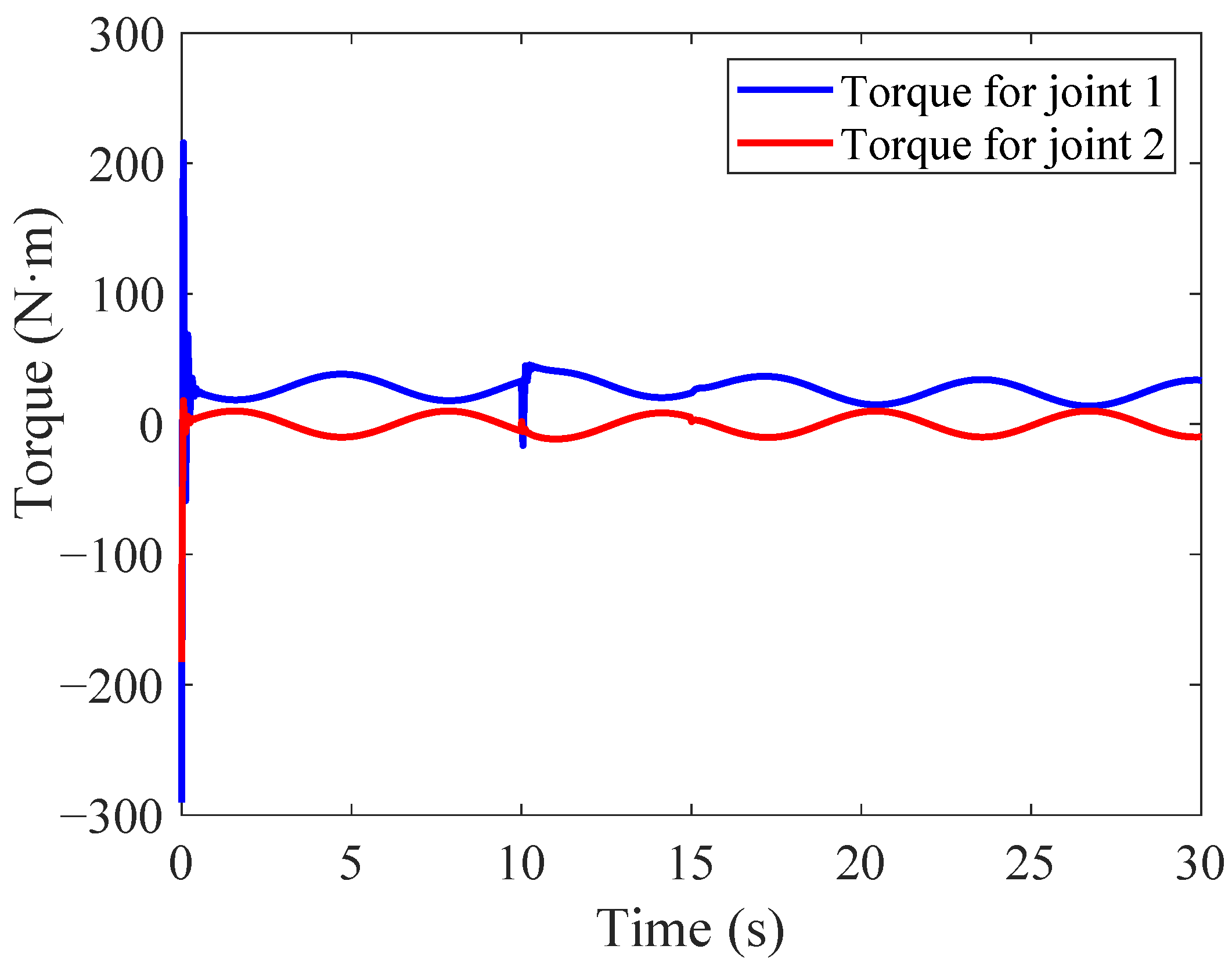

4.2.4. Control Signal Boundedness

5. Conclusions and Future Work

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Liu, Y.; Wang, H.; Fan, Q. Adaptive learning and sliding mode control for a magnetic microrobot precision tracking with uncertainties. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2023, 8, 7767–7774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, C.; Yang, C.; Chen, Z. Bio-inspired robotic impedance adaptation for human-robot collaborative tasks. Sci. China Inf. Sci. 2020, 63, 170201. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Lu, Q.; Chen, J.; Jiang, N.; Li, K. A Robust Region Control Approach for Simultaneous Trajectory Tracking and Compliant Physical Human–Robot Interaction. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. Syst. 2023, 53, 6388–6400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Li, Z.; Liu, H.; Kan, Z. Skill transfer learning for autonomous robots and human–robot cooperation: A survey. Robot. Auton. Syst. 2020, 128, 103515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z.; Wang, Z.; Lv, Q.; Yang, J. Impedance Learning-Based Hybrid Adaptive Control of Upper Limb Rehabilitation Robots. Actuators 2024, 13, 220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selvaggio, M.; Cognetti, M.; Nikolaidis, S.; Ivaldi, S.; Siciliano, B. Autonomy in physical human-robot interaction: A brief survey. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2021, 6, 7989–7996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, D.; Yang, C.; Jiang, Y.; Zhang, H. Hybrid impedance and admittance control for optimal robot—Environment interaction. Robotica 2024, 42, 510–535. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.; Xu, H.; Jiang, R.; Zhou, Y.; Jiang, S.; Cheng, X.; Li, X.; He, B. Adaptive Variable Impedance Control in Physical Human-Robot Interaction based on Arm End Stiffness Estimation. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2025, 74, 7510812. [Google Scholar]

- Ferraguti, F.; Talignani Landi, C.; Sabattini, L.; Bonfe, M.; Fantuzzi, C.; Secchi, C. A variable admittance control strategy for stable physical human—Robot interaction. Int. J. Robot. Res. 2019, 38, 747–765. [Google Scholar]

- Sharifi, M.; Zakerimanesh, A.; Mehr, J.K.; Torabi, A.; Mushahwar, V.K.; Tavakoli, M. Impedance variation and learning strategies in human-robot interaction. IEEE Trans. Cybern. 2021, 52, 6462–6475. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, M.H.; Ogawa, S.; Konno, A. Symmetry position/force hybrid control for cooperative object transportation using multiple humanoid robots. Adv. Robot. 2016, 30, 131–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngo, V.T.; Liu, Y.C. Adaptive Impedance and Admittance Controls for Physical Human-Robot Interaction with Force-Sensorless. In Proceedings of the 2024 American Control Conference (ACC), Toronto, ON, Canada, 10–12 July 2024; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2024; pp. 3791–3796. [Google Scholar]

- Hogan, N. Impedance control: An approach to manipulation. In Proceedings of the 1984 American Control Conference, San Diego, CA, USA, 6–8 June 1984; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 1984; pp. 304–313. [Google Scholar]

- Ott, C.; Mukherjee, R.; Nakamura, Y. Unified impedance and admittance control. In Proceedings of the 2010 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation, Anchorage, Alaska, 3–8 May 2010; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2010; pp. 554–561. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Li, Z.; Liu, H.; Kan, Z.; Xu, B. Bioinspired embodiment for intelligent sensing and dexterity in fine manipulation: A survey. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2020, 16, 4308–4321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Peng, G.; Yang, C. Adaptive Admittance Control with Dynamical Systems for Optimized Motion Adaptation. In Proceedings of the 2024 International Conference on Advanced Robotics and Mechatronics (ICARM), Hyderabad, India, 31 July 2024; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2024; pp. 1032–1037. [Google Scholar]

- Abdullahi, A.M.; Haruna, A.; Chaichaowarat, R. Hybrid adaptive impedance and admittance control based on the sensorless estimation of interaction joint torque for exoskeletons: A case study of an upper limb rehabilitation robot. J. Sens. Actuator Netw. 2024, 13, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bascetta, L. A passivity-based adaptive admittance control strategy for physical human-robot interaction in hands-on tasks. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE 18th International Conference on Automation Science and Engineering (CASE), Mexico City, Mexico, 20–24 August 2022; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2022; pp. 2267–2272. [Google Scholar]

- Slotine, J.J.E.; Li, W. On the adaptive control of robot manipulators. Int. J. Robot. Res. 1987, 6, 49–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slotine, J.J.E.; Li, W. Composite adaptive control of robot manipulators. Automatica 1989, 25, 509–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsia, T. Adaptive control of robot manipulators-a review. In Proceedings of the 1986 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation, San Francisco, CA, USA, 7–10 April 1986; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 1986; Volume 3, pp. 183–189. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, S.; Wu, Y.; He, X.; Wang, J. Neural Network-Based Cooperative Trajectory Tracking Control for a Mobile Dual Flexible Manipulator. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2023, 34, 6545–6556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Si, C.; Wang, Q.G.; Yu, J. Event-Triggered Adaptive Fuzzy Neural Network Output Feedback Control for Constrained Stochastic Nonlinear Systems. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2024, 35, 5345–5354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, W.; Zhou, H.; Zhou, J.; Yao, J. Neural Network-Based Adaptive Asymptotic Prescribed Performance Tracking Control of Hydraulic Manipulators. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. Syst. 2023, 53, 285–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Hou, Z.; Polycarpou, M.M. Controller-dynamic-linearization-based data-driven ILC for nonlinear discrete-time systems with RBFNN. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. Syst. 2021, 52, 4981–4992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, X.; Liu, Y.; Hu, Y.; Li, Z. Integrated Task Sensing and Whole Body Control for Mobile Manipulation With Series Elastic Actuators. IEEE Trans. Autom. Sci. Eng. 2022, 20, 413–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Li, Z.; Su, H.; Su, C.Y. Whole-Body Control of an Autonomous Mobile Manipulator Using Series Elastic Actuators. IEEE/ASME Trans. Mechatron. 2021, 26, 657–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fei, J.; Wang, T. Adaptive fuzzy-neural-network based on RBFNN control for active power filter. Int. J. Mach. Learn. Cybern. 2019, 10, 1139–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, S.; Hang, C.; Lee, T.; Zhang, T. Stable Adaptive Neural Network Control Design; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayakawa, T.; Haddad, W.M.; Hovakimyan, N. Neural network adaptive control for a class of nonlinear uncertain dynamical systems with asymptotic stability guarantees. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. 2008, 19, 80–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Ge, S.S.; How, B.V.E. Robust adaptive neural network control for a class of uncertain MIMO nonlinear systems with input nonlinearities. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. 2010, 21, 796–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.; Zhang, C.; Si, W.; Jiang, Y.; Yang, C.; Zeng, C. A physical human–robot interaction framework for trajectory adaptation based on human motion prediction and adaptive impedance control. IEEE Trans. Autom. Sci. Eng. 2024, 22, 5072–5083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Yue, D.; Dong, Z. Robust integral of neural network and precision motion control of electrical–optical gyro-stabilized platform with unknown input dead-zones. ISA Trans. 2019, 95, 254–265. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Liu, C.; Zhao, K.; Si, W.; Li, J.; Yang, C. Neuroadaptive Admittance Control for Human–Robot Interaction With Human Motion Intention Estimation and Output Error Constraint. IEEE Trans. Cybern. 2025, 55, 3005–3016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Utkin, V.I. Chattering suppression methods in sliding mode control systems. Annu. Rev. Control 2007, 31, 179–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Jagannathan, S.; Sun, Y. Robust integral of neural network and error sign control of MIMO nonlinear systems. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2015, 26, 3278–3286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sciavicco, L.; Siciliano, B. Modelling and Control of Robot Manipulators; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.; Hill, D.J.; Ge, S.S.; Chen, G. An ISS-modular approach for adaptive neural control of pure-feedback systems. Automatica 2006, 42, 723–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, W.; Xue, C.; Yu, X.; Li, Z.; Yang, C. Admittance-based controller design for physical human–robot interaction in the constrained task space. IEEE Trans. Autom. Sci. Eng. 2020, 17, 1937–1949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huo, Y.; Li, P.; Chen, D.; Liu, Y.H.; Li, X. Model-free adaptive impedance control for autonomous robotic sanding. IEEE Trans. Autom. Sci. Eng. 2021, 19, 3601–3611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shtessel, Y.; Edwards, C.; Fridman, L.; Levant, A. Sliding Mode Control and Observation; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014; Volume 10. [Google Scholar]

| Methods | (rad) | (rad) | (N·m) |

|---|---|---|---|

| SMC | 0.1065 | 28.6725 | |

| RISE | 0.0893 | 28.1323 | |

| ARINNSE | 0.0515 | 28.0857 |

| Methods | (rad) | (rad) | (N·m) |

|---|---|---|---|

| SMC | 0.0003 | 1.6721 | |

| RISE | 0.0352 | 1.6079 | |

| ARINNSE | 0.0204 | 1.6167 |

| Arm Joints | (rad) | (rad) | (N·m) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.0120 | 29.1672 | |

| 2 | 0.0151 | 7.2041 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chen, S.; Jiang, L.; Bai, K.; Chen, Y.; Xu, X.; Jiang, G.; Liu, Y. Human–Robot Interaction for a Manipulator Based on a Neural Adaptive RISE Controller Using Admittance Model. Electronics 2025, 14, 4862. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14244862

Chen S, Jiang L, Bai K, Chen Y, Xu X, Jiang G, Liu Y. Human–Robot Interaction for a Manipulator Based on a Neural Adaptive RISE Controller Using Admittance Model. Electronics. 2025; 14(24):4862. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14244862

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen, Shengli, Lin Jiang, Keqiang Bai, Yuming Chen, Xiaoang Xu, Guanwu Jiang, and Yueyue Liu. 2025. "Human–Robot Interaction for a Manipulator Based on a Neural Adaptive RISE Controller Using Admittance Model" Electronics 14, no. 24: 4862. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14244862

APA StyleChen, S., Jiang, L., Bai, K., Chen, Y., Xu, X., Jiang, G., & Liu, Y. (2025). Human–Robot Interaction for a Manipulator Based on a Neural Adaptive RISE Controller Using Admittance Model. Electronics, 14(24), 4862. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14244862