ASFNOformer—A Superior Frequency Domain Token Mixer in Spiking Transformer

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- Theoretical Validation: We conducted a theoretical analysis of binary versus continuous signals using the Fourier transform to demonstrate the unique superiority of frequency-domain analysis for SNNs. We found that for binary spike signals, the Fourier transform effectively enhances signal intensity representation. Furthermore, signal analysis experiments confirm that this method efficiently extracts temporal features from dynamic datasets—a task that remains challenging for traditional spatial methods.

- (2)

- Novel Architecture: Based on the theoretical analysis and the inherent spatiotemporal nature of neuromorphic data, we designed the ASFNO module with weight sharing and weight block diagonal matrix. This module explicitly integrates temporal dimensions and employs LIF neurons with Learnable Weight Parameters (LWP-LIF) to further enhance network sparsity and adaptability.

- (3)

- SOTA Performance: We integrated the ASFNO module as a token mixer within Spiking Transformers. Experimental results on multiple neuromorphic datasets confirm that our model achieves state-of-the-art performance in classification tasks.

2. Related Works

2.1. Spiking Neural Networks

2.2. Token Mixer

2.3. Frequency Domain Analysis

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Signal Analysis

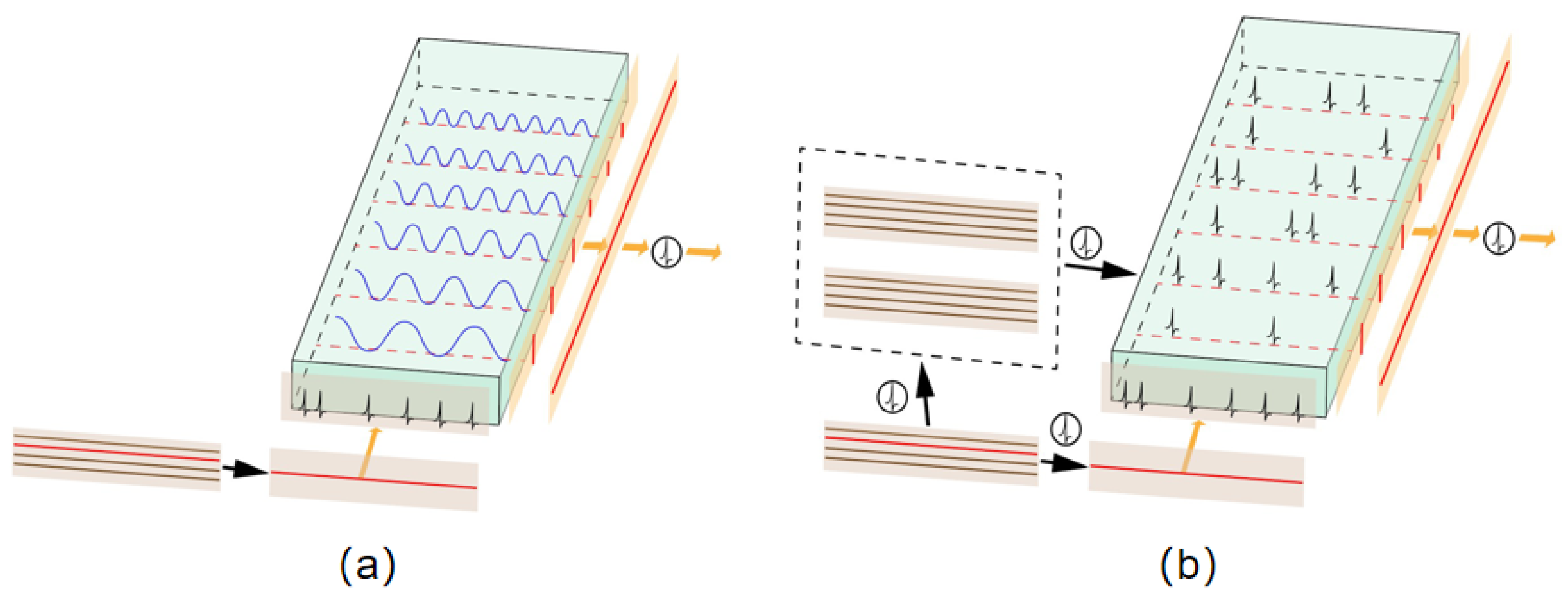

3.2. AFNO in Spikingformer

3.3. Weight Sharing and Weight Block Diagonal Matrix

3.4. LIF Model with Learnable Weight Parameter (LWP-LIF)

3.5. The Temporal Information in ASFNO

4. Results

4.1. Setup

4.2. Performance of Static Data Sets

4.3. Performance of Dynamic Data Sets

4.4. Ablation Experiment

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ANNs | Artificial Neural Networks |

| SNNs | Spiking Neural Networks |

| FFT | Fast Fourier Transform |

| DFT | Discrete Fourier Transform |

| GFNs | Global Filter Networks |

| ASFNO(former) | Adaptive Spiking Fourier Neural Operator (Transformer) |

| AFNO | Adaptive Fourier Neural Operator |

| DVS | Dynamic Vision Sensors |

| MHA | Multi-Head Attention |

| MLP | Multi-Layer Perceptron structure |

| LIF | Leaky Integrate- and -Fire |

| SSA | Spike Self-Attention |

| SPS | Spike Patch Splitting |

| RPEs | Relative Position Embeddings |

| BN | Batch Normalization |

| SN | Spiking Neuron |

| GAP | Global Average Pooling |

| CH | Classification Header |

| LWP-LIF | LIF Model with Learnable Weight Parameter |

| FLOPs | Floating Point Operations |

References

- Maass, W. Networks of spiking neurons: The third generation of neural network models. Neural Netw. 1997, 10, 1659–1671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, K.; Jaiswal, A.; Panda, P. Towards spike-based machine intelligence with neuromorphic computing. Nature 2019, 575, 607–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mnih, V.; Kavukcuoglu, K.; Silver, D.; Rusu, A.A.; Veness, J.; Bellemare, M.G.; Graves, A.; Riedmiller, M.; Fidjeland, A.K.; Ostrovski, G.; et al. Human-level control through deep reinforcement learning. Nature 2015, 518, 529–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, W.; Yu, Z.; Chen, Y.; Huang, T.; Masquelier, T.; Tian, Y. Deep residual learning in spiking neural networks. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2021, 34, 21056–21069. [Google Scholar]

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, Ł.; Polosukhin, I. Attention is all you need. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2017, 30, 5998–6008. [Google Scholar]

- Barranco, F.; Fermuller, C.; Aloimonos, Y.; Delbruck, T. A dataset for visual navigation with neuromorphic methods. Front. Neurosci. 2016, 10, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Liu, H.; Ji, X.; Li, G.; Shi, L. Cifar10-dvs: An event-stream dataset for object classification. Front. Neurosci. 2017, 11, 309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orchard, G.; Jayawant, A.; Cohen, G.K.; Thakor, N. Converting static image datasets to spiking neuromorphic datasets using saccades. Front. Neurosci. 2015, 9, 437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, L.; Wu, Y.; Hu, X.; Liang, L.; Ding, Y.; Li, G.; Zhao, G.; Li, P.; Xie, Y. Rethinking the performance comparison between SNNS and ANNS. Neural Netw. 2020, 121, 294–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, J.; Deng, L.; Song, S.; Zhao, M.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, S.; Wang, G.; Zou, Z.; Wu, Z.; He, W.; et al. Towards artificial general intelligence with hybrid Tianjic chip architecture. Nature 2019, 572, 106–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amir, A.; Taba, B.; Berg, D.; Melano, T.; McKinstry, J.; Di Nolfo, C.; Nayak, T.; Andreopoulos, A.; Garreau, G.; Mendoza, M.; et al. A low power, fully event-based gesture recognition system. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017; pp. 7243–7252. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.K.; Buonomano, D.V. Embedding multiple trajectories in simulated recurrent neural networks in a self-organizing manner. J. Neurosci. 2009, 29, 13172–13181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maheswaranathan, N.; McIntosh, L.T.; Kastner, D.B.; Melander, J.; Brezovec, L.; Nayebi, A.; Wang, J.; Ganguli, S.; Baccus, S.A. Deep learning models reveal internal structure and diverse computations in the retina under natural scenes. bioRxiv 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Valois, R.L.; Albrecht, D.G.; Thorell, L.G. Spatial frequency selectivity of cells in macaque visual cortex. Vis. Res. 1982, 22, 545–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daugman, J.G. Uncertainty relation for resolution in space, spatial frequency, and orientation optimized by two-dimensional visual cortical filters. J. Opt. Soc. Am. A 1985, 2, 1160–1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, M.; Hu, J.; Zhou, Z.; Yuan, L.; Tian, Y.; Xu, B.; Li, G. Spike-driven transformer. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2023, 36, 64043–64058. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Y.; Deng, L.; Li, G.; Zhu, J.; Shi, L. Spatio-temporal backpropagation for training high-performance spiking neural networks. Front. Neurosci. 2018, 12, 331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, W.; Yu, Z.; Chen, Y.; Masquelier, T.; Huang, T.; Tian, Y. Incorporating learnable membrane time constant to enhance learning of spiking neural networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Montreal, QC, Canada, 10–17 October 2021; pp. 2661–2671. [Google Scholar]

- Bu, T.; Fang, W.; Ding, J.; Dai, P.; Yu, Z.; Huang, T. Optimal ANN-SNN conversion for high-accuracy and ultra-low-latency spiking neural networks. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2303.04347. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, J.; Yu, Z.; Tian, Y.; Huang, T. Optimal ANN-SNN conversion for fast and accurate inference in deep spiking neural networks. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2105.11654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, B.; Srinivasan, G.; Roy, K. Rmp-snn: Residual membrane potential neuron for enabling deeper high-accuracy and low-latency spiking neural network. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Seattle, WA, USA, 13–19 June 2020; pp. 13558–13567. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J.H.; Delbruck, T.; Pfeiffer, M. Training deep spiking neural networks using backpropagation. Front. Neurosci. 2016, 10, 508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrestha, S.B.; Orchard, G. Slayer: Spike layer error reassignment in time. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2018, 31, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, W.; Luo, M.; Zhou, P.; Si, S.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, X.; Feng, J.; Yan, S. Metaformer is actually what you need for vision. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, New Orleans, LA, USA, 18–24 June 2022; pp. 10819–10829. [Google Scholar]

- Child, R.; Gray, S.; Radford, A.; Sutskever, I. Generating long sequences with sparse transformers. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1904.10509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parmar, N.; Vaswani, A.; Uszkoreit, J.; Kaiser, Ł.; Shazeer, N.; Ku, A.; Tran, D. Image transformer. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning, PMLR, Stockholm, Sweden, 10–15 July 2018; pp. 4055–4064. [Google Scholar]

- Lian, D.; Yu, Z.; Sun, X.; Gao, S. As-mlp: An axial shifted mlp architecture for vision. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2107.08391. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S.; Li, B.Z.; Khabsa, M.; Fang, H.; Ma, H. Linformer: Self-attention with linear complexity. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2006.04768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitaev, N.; Kaiser, Ł.; Levskaya, A. Reformer: The efficient transformer. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2001.04451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, A.; Saffar, M.; Vaswani, A.; Grangier, D. Efficient content-based sparse attention with routing transformers. Trans. Assoc. Comput. Linguist. 2021, 9, 53–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee-Thorp, J.; Ainslie, J.; Eckstein, I.; Ontanon, S. Fnet: Mixing tokens with fourier transforms. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2105.03824. [Google Scholar]

- Rao, Y.; Zhao, W.; Zhu, Z.; Lu, J.; Zhou, J. Global filter networks for image classification. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2021, 34, 980–993. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Z.; Kovachki, N.; Azizzadenesheli, K.; Liu, B.; Bhattacharya, K.; Stuart, A.; Anandkumar, A. Fourier neural operator for parametric partial differential equations. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2010.08895. [Google Scholar]

- Guibas, J.; Mardani, M.; Li, Z.; Tao, T.; Anandkumar, A.; Catanzaro, B. Adaptive fourier neural operators: Efficient token mixers for transformers. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2111.13587. [Google Scholar]

- Jiménez-Fernández, A.; Cerezuela-Escudero, E.; Miró-Amarante, L.; Domínguez-Morales, M.J.; Gómez-Rodríguez, F.; Linares-Barranco, A.; Jiménez-Moreno, G. A binaural neuromorphic auditory sensor for FPGA: A spike signal processing approach. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2017, 28, 804–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auge, D.; Mueller, E. Resonate-and-fire neurons as frequency selective input encoders for spiking neural networks. Neural Netw. 2022, 155, 524–539. [Google Scholar]

- López-Randulfe, J.; Duswald, T.; Bing, Z.; Knoll, A. Spiking neural network for fourier transform and object detection for automotive radar. Front. Neurorobot. 2021, 15, 688344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- López-Randulfe, J.; Reeb, N.; Karimi, N.; Knoll, A. Time-coded spiking fourier transform in neuromorphic hardware. IEEE Trans. Comput. 2022, 71, 2792–2802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paszke, A. Pytorch: An imperative style, high-performance deep learning library. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1912.01703. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Z.; Zhu, Y.; He, C.; Wang, Y.; Yan, S.; Tian, Y.; Yuan, L. Spikformer: When spiking neural network meets transformer. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2209.15425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeCun, Y.; Bottou, L.; Bengio, Y.; Haffner, P. Gradient-based learning applied to document recognition. Proc. IEEE 1998, 86, 2278–2324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C.; Zhang, H.; Zhou, Z.; Yuan, L.; Tian, Y. Qkformer: Hierarchical spiking transformer using qk attention. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2403.16552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, S.; Li, Y.; Zhang, S.; Chu, X.; Li, H. Temporal efficient training of spiking neural network via gradient re-weighting. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2202.11946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, H.; Wu, Y.; Deng, L.; Hu, Y.; Li, G. Going deeper with directly-trained larger spiking neural networks. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Virtual, 2–9 February 2021; Volume 35, pp. 11062–11070. [Google Scholar]

- Duan, C.; Ding, J.; Chen, S.; Yu, Z.; Huang, T. Temporal effective batch normalization in spiking neural networks. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2022, 35, 34377–34390. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, Y.; Zhang, L.; Chen, Y.; Hu, X.; Liu, X.; Peng, W.; Ma, X.; Ma, Z. Real spike: Learning real-valued spikes for spiking neural networks. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision, Tel Aviv, Israel, 23–27 October 2022; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 52–68. [Google Scholar]

- Meng, Q.; Xiao, M.; Yan, S.; Wang, Y.; Lin, Z.; Luo, Z. Training high-performance low-latency spiking neural networks by differentiation on spike representation. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, New Orleans, LA, USA, 18–24 June 2022; pp. 12444–12453. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, C.; Yu, L.; Zhou, Z.; Zhang, H.; Ma, Z.; Zhou, H.; Tian, Y. Spikingformer: Spike-driven residual learning for transformer-based spiking neural network. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2304.11954. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, C.; Zhang, H.; Zhou, Z.; Yuan, L.; Tian, Y. Enhancing the performance of transformer-based spiking neural networks by SNN-optimized downsampling with precise gradient backpropagation. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2305.05954. [Google Scholar]

| Method | CIFAR10 | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Para (M) | Time Steps | Accuracy | |

| TET [43] | 12.63 | 6 | 94.50 |

| tdBN [44] | 12.63 | 4 | 92.92 |

| TEBN [45] | 12.63 | 6 | 94.71 |

| Real Spike [46] | 12.63 | 6 | 95.78 |

| DSR [47] | 11.20 | 20 | 95.40 |

| SpikFormer [40] | 9.32 | 4 | 95.51 |

| SpikingFormer [48] | 9.32 | 4 | 95.81 |

| ASFNOFormer (ours) | 9.12 | 4 | 96.04 |

| Method | Cifar10-DVS | DVS128-Gesture | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Para (M) | Time Steps | Accuracy | Para (M) | Time Steps | Accuracy | |

| tdBN [44] | 12.63 | 10 | 67.80 | 12.63 | 10 | 96.90 |

| TEBN [45] | 12.63 | 10 | 75.10 | 12.63 | 10 | 97.50 |

| CML [7] | 2.57 | 16 | 80.90 | 2.57 | 16 | 98.30 |

| S-Transformer [49] | 2.57 | 16 | 80.00 | 2.57 | 16 | 99.30 |

| Spikformer [40] | 2.57 | 16 | 80.90 | 2.57 | 16 | 98.30 |

| Spikingformer [48] | 2.57 | 16 | 81.30 | 2.57 | 16 | 98.30 |

| ASFNOformer (ours) | 2.12 | 16 | 82.80 | 2.12 | 16 | 99.10 |

| Model | Accuracy | FLOPS (G) |

|---|---|---|

| Spikeformer | 80.9 | 2.79 |

| ASFNO (ours) | 82.8 | 3.19 |

| Model | Accuracy |

|---|---|

| QKformer | 84.0 |

| ASFNO (ours) | 85.5 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gao, S.; Hong, Z.; Gu, Y.; Wu, J.; Yang, Y.; Huang, R. ASFNOformer—A Superior Frequency Domain Token Mixer in Spiking Transformer. Electronics 2025, 14, 4860. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14244860

Gao S, Hong Z, Gu Y, Wu J, Yang Y, Huang R. ASFNOformer—A Superior Frequency Domain Token Mixer in Spiking Transformer. Electronics. 2025; 14(24):4860. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14244860

Chicago/Turabian StyleGao, Shouwei, Zichao Hong, Yangqi Gu, Jianfeng Wu, Yang Yang, and Ruilong Huang. 2025. "ASFNOformer—A Superior Frequency Domain Token Mixer in Spiking Transformer" Electronics 14, no. 24: 4860. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14244860

APA StyleGao, S., Hong, Z., Gu, Y., Wu, J., Yang, Y., & Huang, R. (2025). ASFNOformer—A Superior Frequency Domain Token Mixer in Spiking Transformer. Electronics, 14(24), 4860. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14244860