4.2. Ablation Study

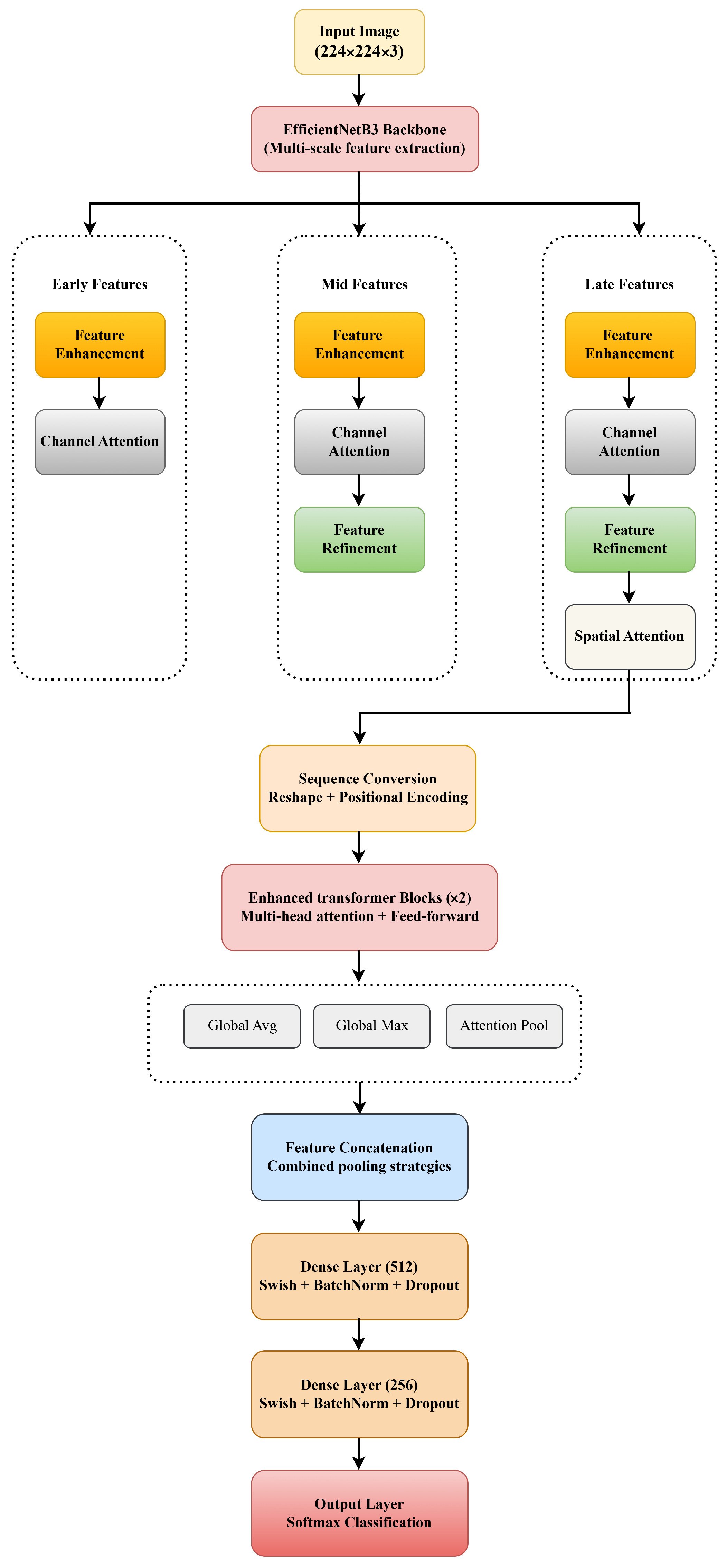

We performed an ablation study to quantitatively identify the gain in performance by each of the proposed components. We constructed five variants of the proposed model by successively adding the individual architectural components (channel attention, spatial attention, feature refinement, and transformer blocks) to the baseline model. The results are shown in

Table 4.

As seen from the results, the baseline model with only EfficientNet-B3 as the backbone already delivers a high level of performance, with an accuracy of 96.49% and an AUC of 98.90%. The model with the channel attention module shows a slightly lower accuracy score, which is probably due to the model over-focusing on the dependencies along the channel dimension. In contrast, the model with the spatial attention module shows improved discrimination, achieving an accuracy of 96.81% and an F1-score of 94.57%, outperforming the baseline model. The models with the feature refinement module and transformer blocks show a drop in performance compared to the baseline. This might be due to the repeated amplification of features, as well as the transformer’s unstable convergence on the small malaria dataset. The proposed NOVA with the optimal attention modules and lightweight transformer-based feature fusion achieves the highest scores in all the reported metrics, with a 97.00% accuracy, a 97.00% F1-score, and a 99.14% AUC.

Analysis of Isolated Module Performance

This observation from the ablation study seems to suggest an important design intuition for this work. Namely, each architectural module, while not performing very well by themselves, can be made useful if properly conditioned and integrated. The feature refinement module, for example, achieves an accuracy of 62.89% when inserted independently, while the Transformer module performs at 69.91% in its standalone manner.

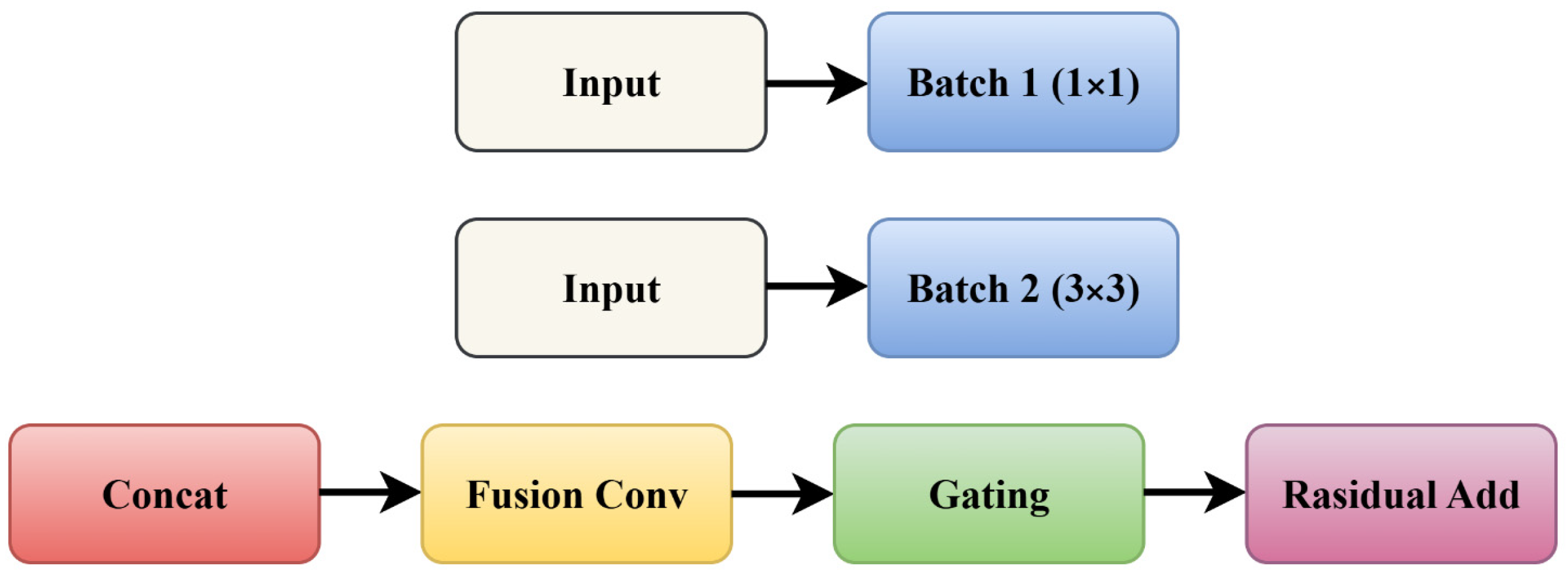

Breaking down the performance gap of the feature refinement module, we believe this is largely because of the following factors: (1) Amplification of non-informative noise—when multi-branch features are fused without attentional selection mechanisms, it non-selectively amplifies both discriminative parasitic features and background noises/artifacts/staining variation. (2) Training instability—in the absence of high-level feature initialization, introducing a gated residual block as in the proposed AFR module further complicates optimization and has difficulty in converging with the small medical dataset. (3) Feature redundancy—with multiple parallel feature refinement branches lacking feature selection mechanisms, AFR introduces redundant feature maps, leading to overfitting. An observation from the activation maps of AFR also supports this hypothesis: with naive initialization, the model still learns to activate highly on cell boundary/background regions instead of the desired inner-cell parasitic components. The performance degradation of the transformer module could be further broken into the following:

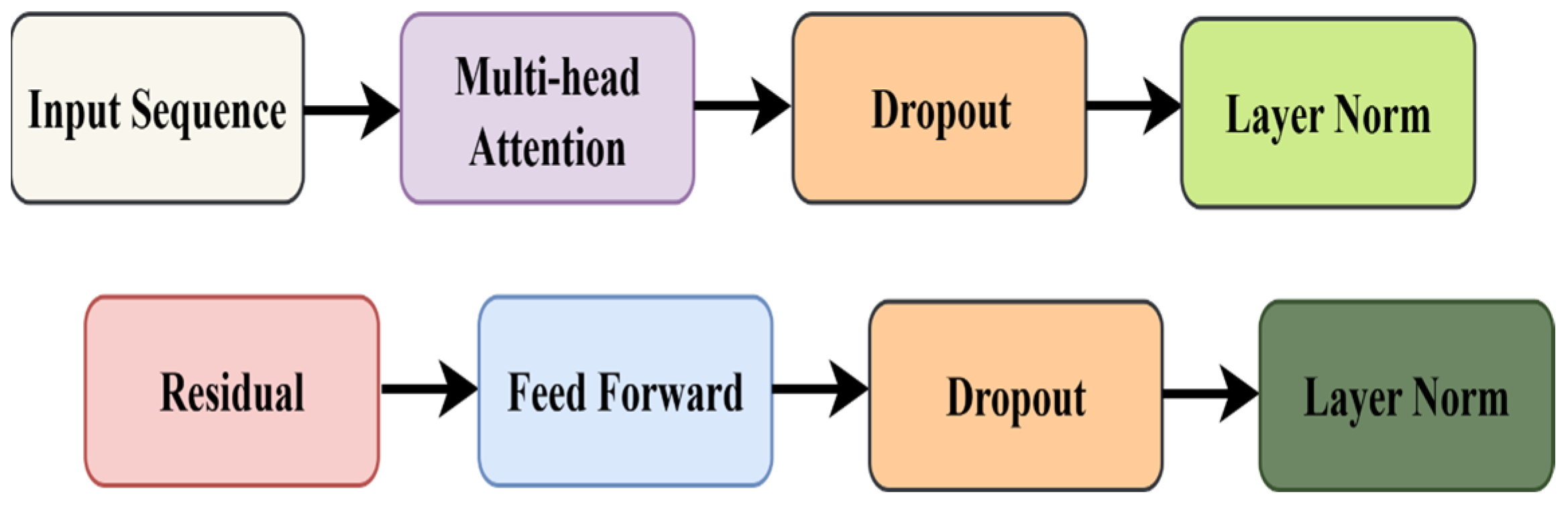

(1) Loss of local contextual information: When the input image is tokenized into flattened non-overlapping patches as transformer inputs, local morphological information becomes lost, which is critical in learning subtle intracellular parasitic features (chromatin dots, hemozoin pigments, etc.).

(2) Data scale mismatch: Transformer-based self-attentional architectures are typically trained on very large-scale datasets (ImageNet with 1.2 M images) to prevent overfitting, while the medical image dataset used in this work contains only 13,152 training images.

(3) Attention falling on wrong region: In the absence of a hierarchically initialized CNN backbone, the model might attend to noisy background regions instead of the discriminative foreground cells.

The final NOVA model addresses the limitations by means of a synergistic hierarchical combination:

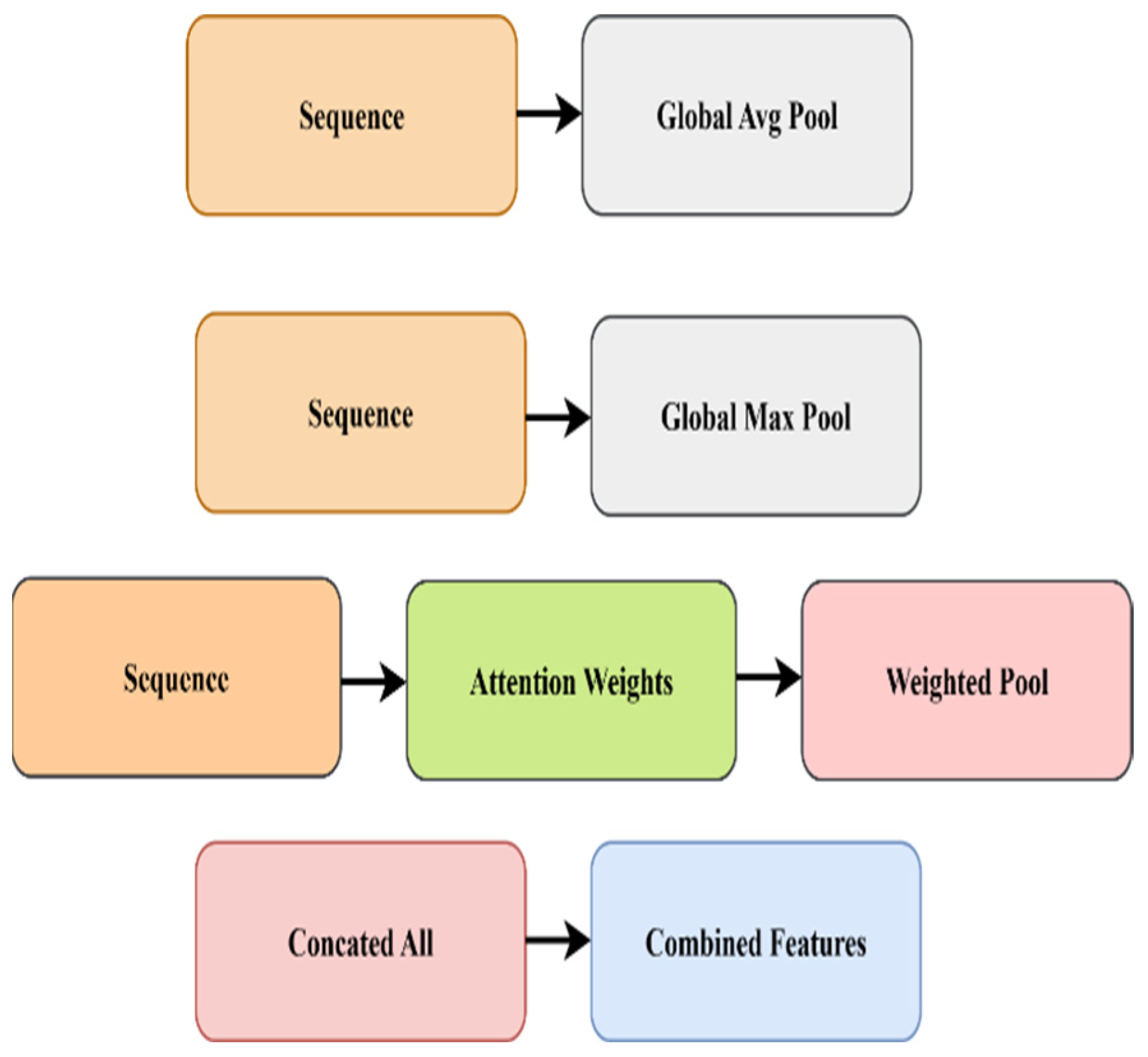

Stage 1 (Foundation): The EfficientNetB3 CNN backbone extracts spatially aware and semantically meaningful features that shield downstream modules from learning spurious patterns.

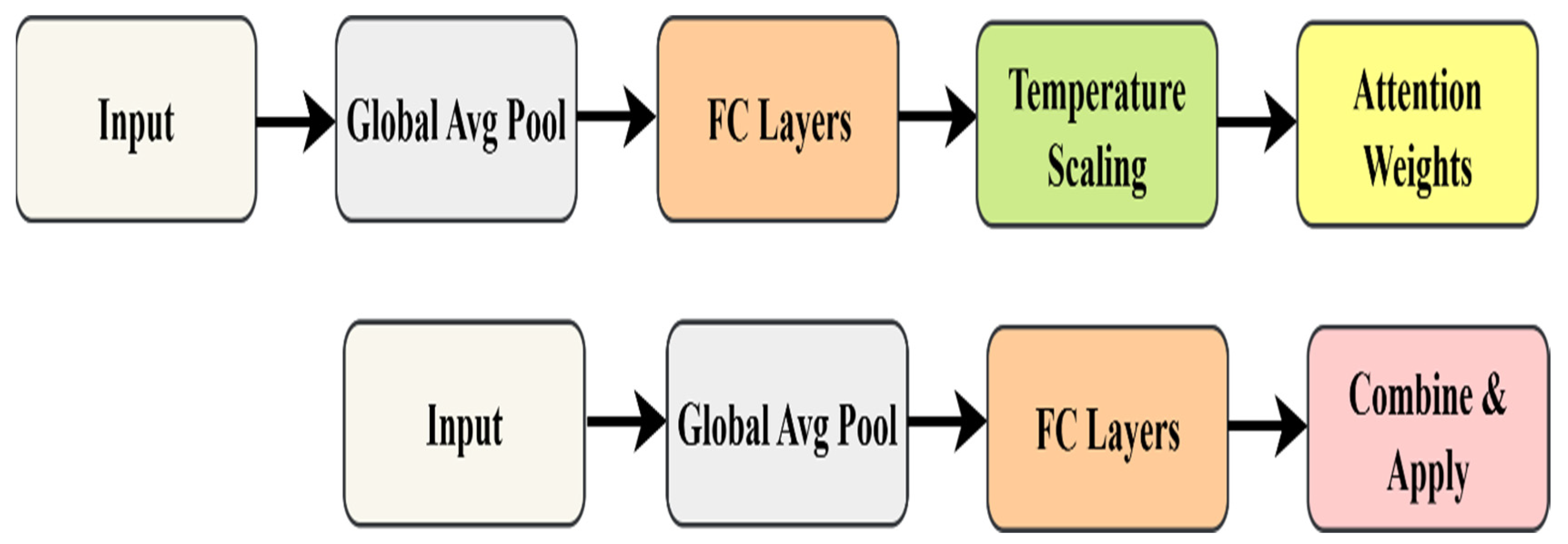

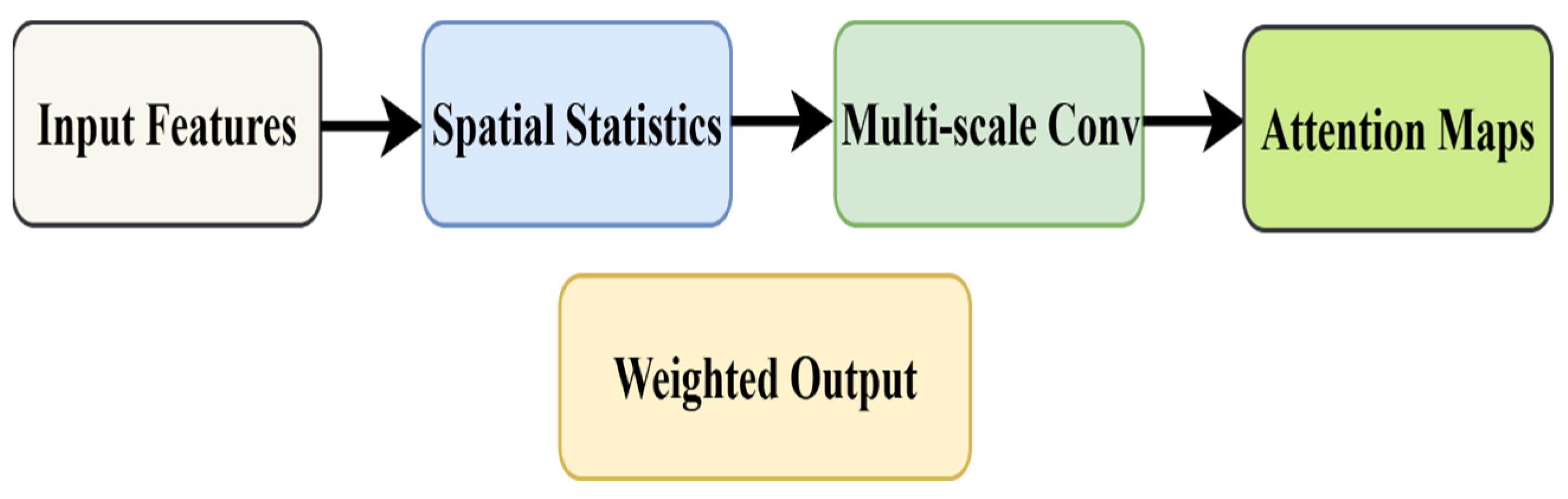

Stage 2 (Selection): Dynamic Channel Attention and Learnable Temperature Spatial Pyramid Attention filter out noisy channels and localize regions of interest BEFORE refinement, preventing noise amplification.

Stage 3 (Enhancement): Feature refinement now operates on attention-filtered representations, allowing the gating mechanism to selectively enhance discriminative parasitic morphologies without amplifying artifacts.

Stage 4 (Global Reasoning): The transformer now receives well-structured, attention-guided features from the CNNs, allowing stable training and the effective modeling of long-range dependencies (e.g., spatial relationships between multiple infected cells).

The hierarchical nature of this design also means that each module can shield its successor from the limitations. Namely, CNNs prevent transformers from learning random patterns, attention prevents refinement from amplifying noise, and refinement provides well-enhanced features for global reasoning. The final NOVA configuration achieves an accuracy of 97.00% and highlights that architectural synergy is key in medical image analysis, where both subtle features and limited data present unique challenges.

4.4. Comparison with Other Conventional Techniques

To further validate the efficiency in diagnosis, we also analyzed and compared the computational efficiency of the NOVA and common deep learning architectures. The number of parameters, floating point operations per second (FLOPs), and inference time per image are reported in

Table 6. The proposed NOVA achieves optimal accuracy along with moderate model complexity. The NOVA only needs 11.8M parameters, much less than DenseNet201 (20.0 M) and EfficientNet-B7 (37.0 M). Similarly, the NOVA only results in 3.1 GFLOPs, which is lower than ResNet50 (4.1 GFLOPs) and EfficientNet-B7 (7.9 GFLOPs). The NOVA only takes 6.8 (ms) to process a 224 × 224 image, making it feasible to be deployed in real-time screening scenarios. The NOVA shows the model’s potential for deployment on mid-range GPUs and edge devices.

The performance evaluation metrics, including accuracy, precision, recall, F1-score, and AUC, are compared for various deep learning models employed in malaria cell detection. DenseNet121, DenseNet169, DenseNet201, VGG16, ResNet50, and CNN, representing conventional architectures, demonstrate promising performance. The accuracy of these models falls within the range of approximately 89.76% to 94.12%. Furthermore, AUC values range from 95.90% to 97.65% for DenseNet201, DenseNet169, DenseNet121, ResNet50, VGG16, and CNN. On the other hand, lightweight models, including MobileNet, MobileNetV2, and EfficientNet-B1, show relatively lower performance. Notably, EfficientNet-B1 has the lowest accuracy at 60.35%. These results suggest that lightweight models, with their reduced parameter complexity, may face challenges in extracting discriminative features for malaria cell classification. InceptionV3, a widely used deep model, yields moderate results with an accuracy of 85.67% and an AUC of 93.50%. This finding suggests that not all deep architectures are equally effective in generalizing the task of malaria cell detection. On the other hand, our proposed NOVA outperforms the existing deep learning models in terms of all metrics, achieving 97.00% accuracy, 96.00% precision, 97.00% recall, 97.00% F1-score, and 98.00% AUC. This result demonstrates the NOVA’s ability to reliably and effectively detect infected cells. Overall, these results position the NOVA as a viable candidate for malaria diagnosis as it outperforms traditional and lightweight deep learning models in discriminative capability and overall classification performance.

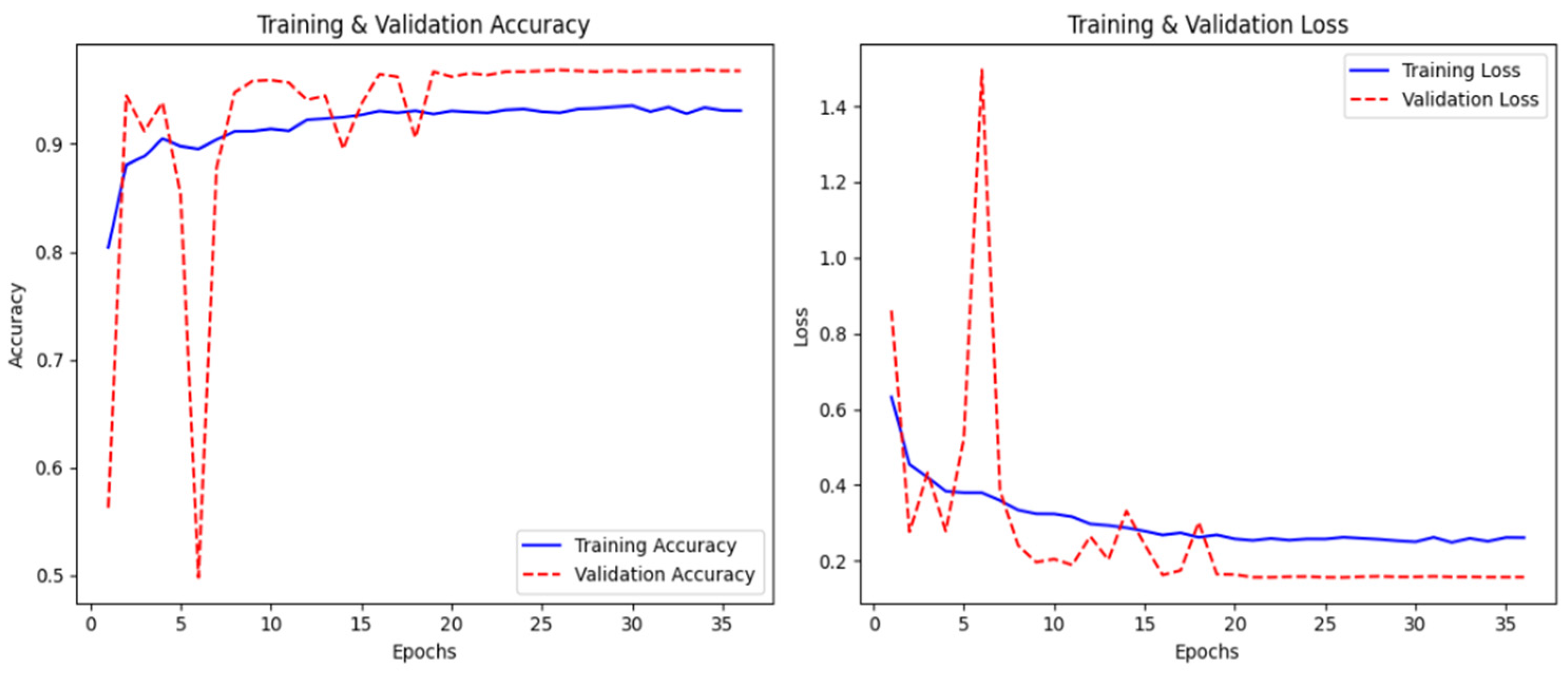

In

Figure 10, the graph represents the model’s training history, which indicates good convergence, with both training and validation accuracy approaching 96% by epoch 35. The loss curves show a smooth decrease in training loss from 0.65 to around 0.25, while the validation loss is somewhat more erratic during the first epochs, eventually settling around 0.18 after about epoch 20. Validation accuracy initially fluctuates quite significantly between epochs 5–15, from 0.50 to 0.98, before stabilizing at a high level. This initial instability is likely due to the model being sensitive to the specific batch compositions in the early stages of training; however, the eventual convergence of both loss and accuracy metrics indicates successful learning without overfitting.

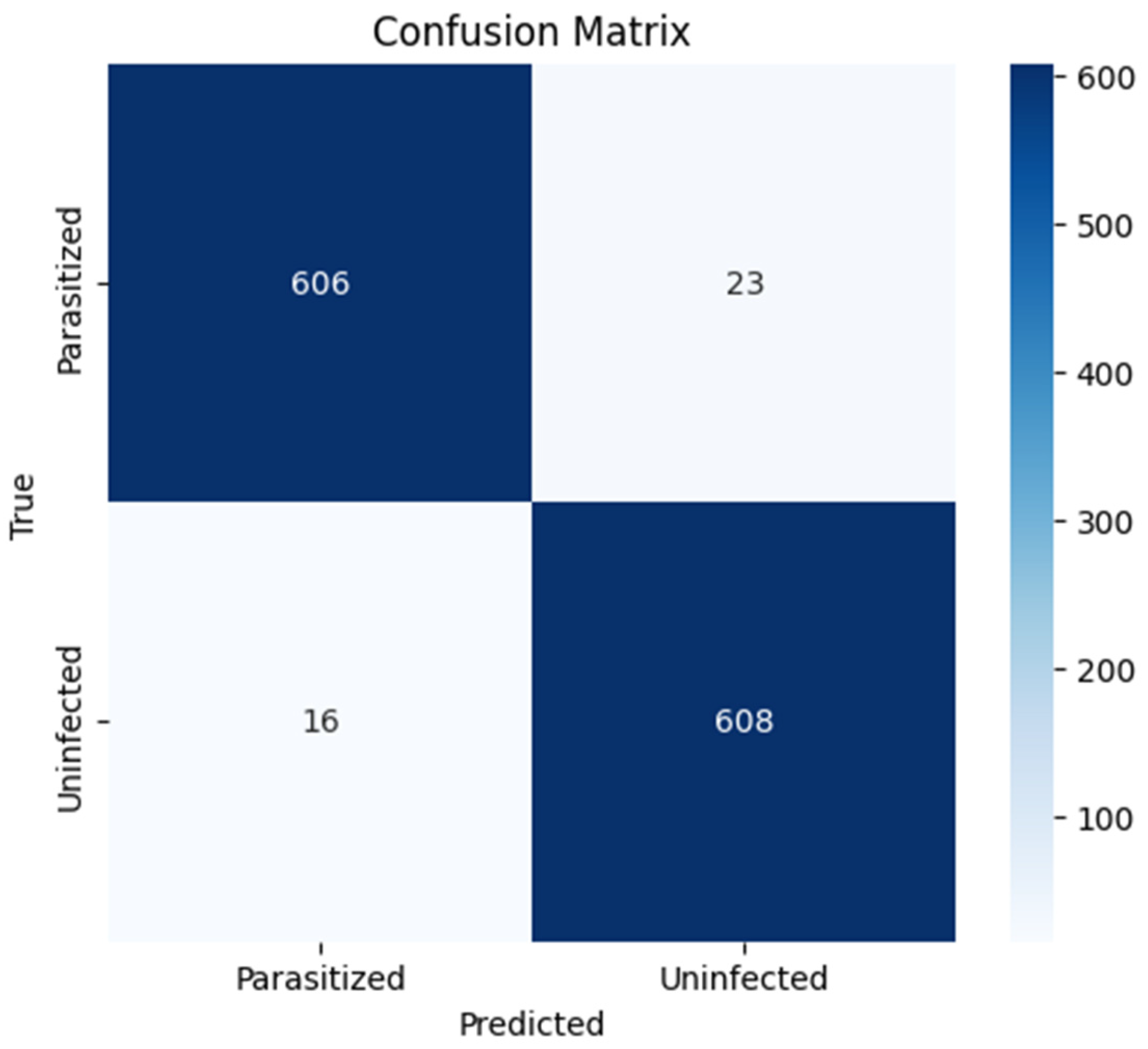

In

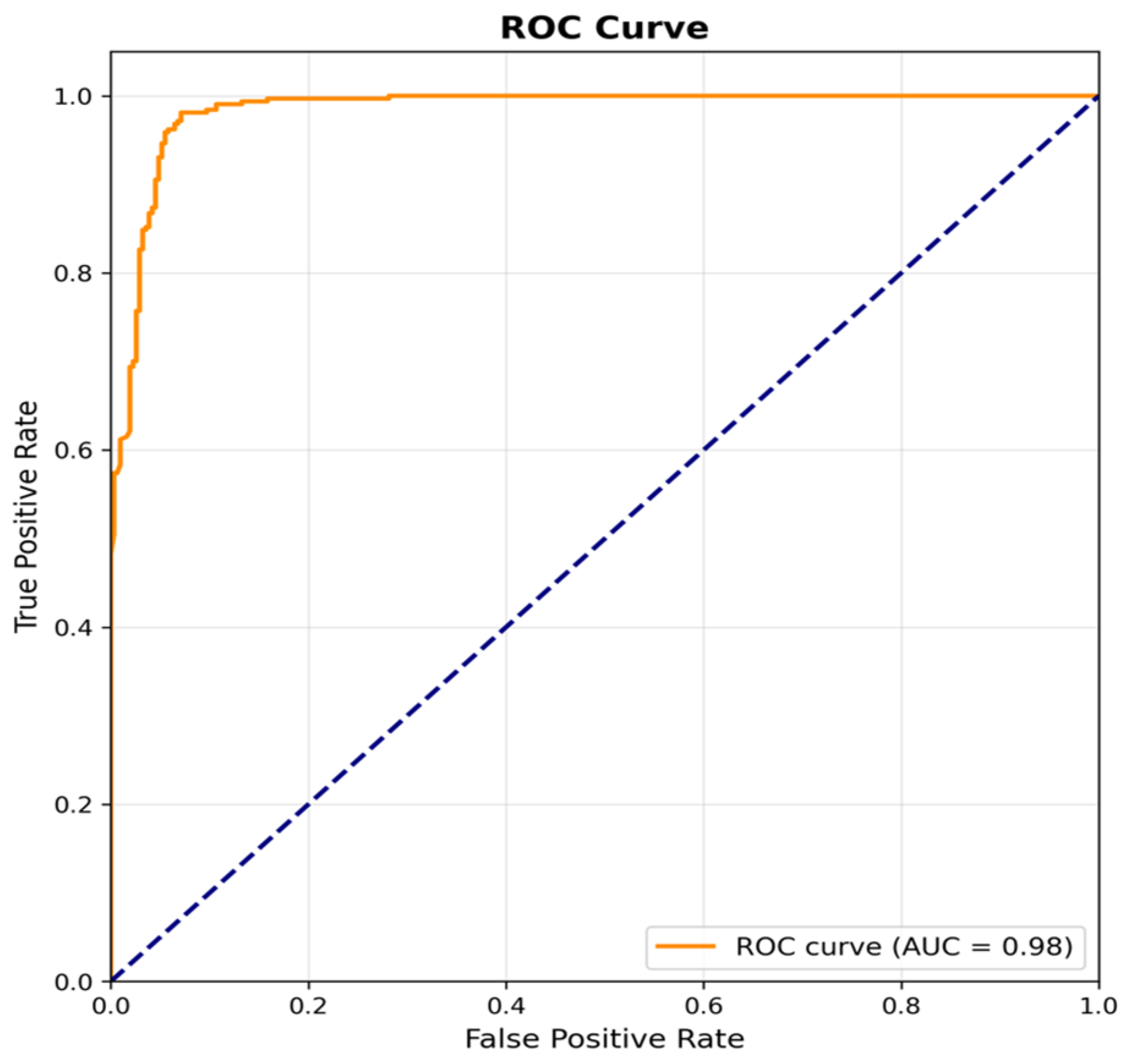

Figure 11, the confusion matrix illustrates the model’s classification performance over the 1253 samples in the test set. The model correctly classified 606 samples as parasitized and 608 as uninfected, with a small number of misclassifications: 23 samples were false negatives (parasitized classified as uninfected) and 16 were false positives (uninfected classified as parasitized). This results in a sensitivity (true positive rate) of 96.3% and a specificity (true negative rate) of 97.4%, reflecting a high level of discriminative performance. In

Figure 12, the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve is provided, which shows an excellent performance with an area under the curve (AUC) of 0.98. The ROC curve quickly rises towards the upper left corner, indicating that the model can achieve high true positive rates while maintaining low false positive rates across different classification thresholds, making it a reliable candidate for deployment in diagnostic settings.

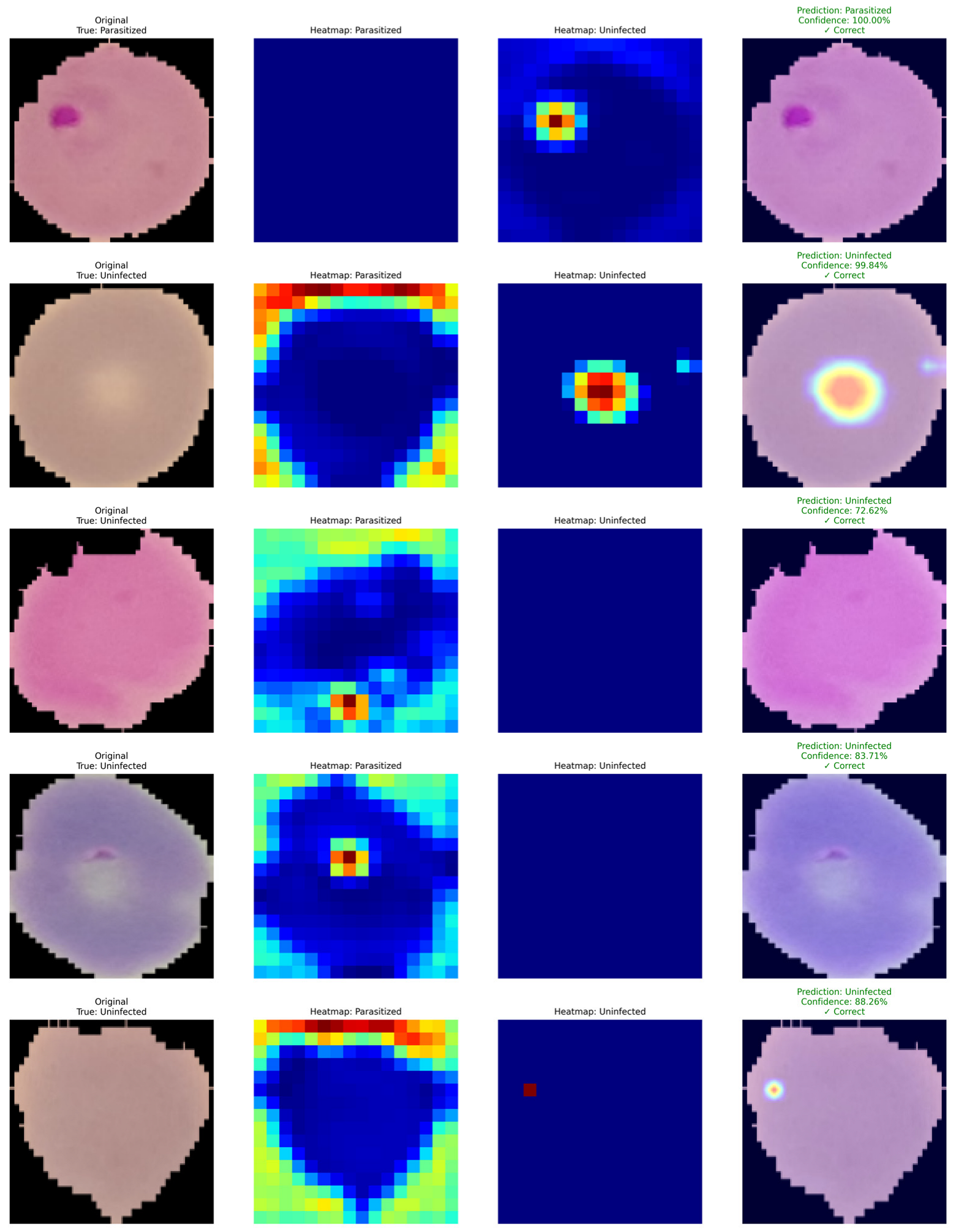

Figure 13 shows Grad-CAM-based interpretability on a few examples from the malaria cell classification task. Each row of the figure consists of (i) the original microscopy image with its ground truth label, (ii) the corresponding Grad-CAM activation map for the parasitized class, (iii) the activation map for the uninfected class, and (iv) the final prediction with confidence. In the correctly classified parasitized samples, the Grad-CAM maps highlight the activation on the area of the intracellular parasite. The model thus appears to capture morphological features that are discriminatory for the positive class, such as chromatin-rich parasite structures and cytoplasmic anomalies. The uninfected heatmap is mostly inactive in these examples, which shows that the model can correctly downregulate the negative class when strong parasitic features are present. In the uninfected samples, the activation maps are consistently different. The uninfected class consistently highlights the central region of the erythrocyte, while the parasitized heatmap is mostly inactive. The model thus appears to base its decision on features such as homogeneous cell texture and the lack of parasitic inclusions. Prediction overlays on the original image further confirm high confidence in the classification. Intriguingly, for some uninfected examples, weak or diffused activation can be observed on the parasitized heatmap. This can potentially be caused by staining artifacts, mild structural anomalies or noise in the sample, and the model’s sensitivity to these. The final prediction is nonetheless correct, as global activation is still consistent within classes.

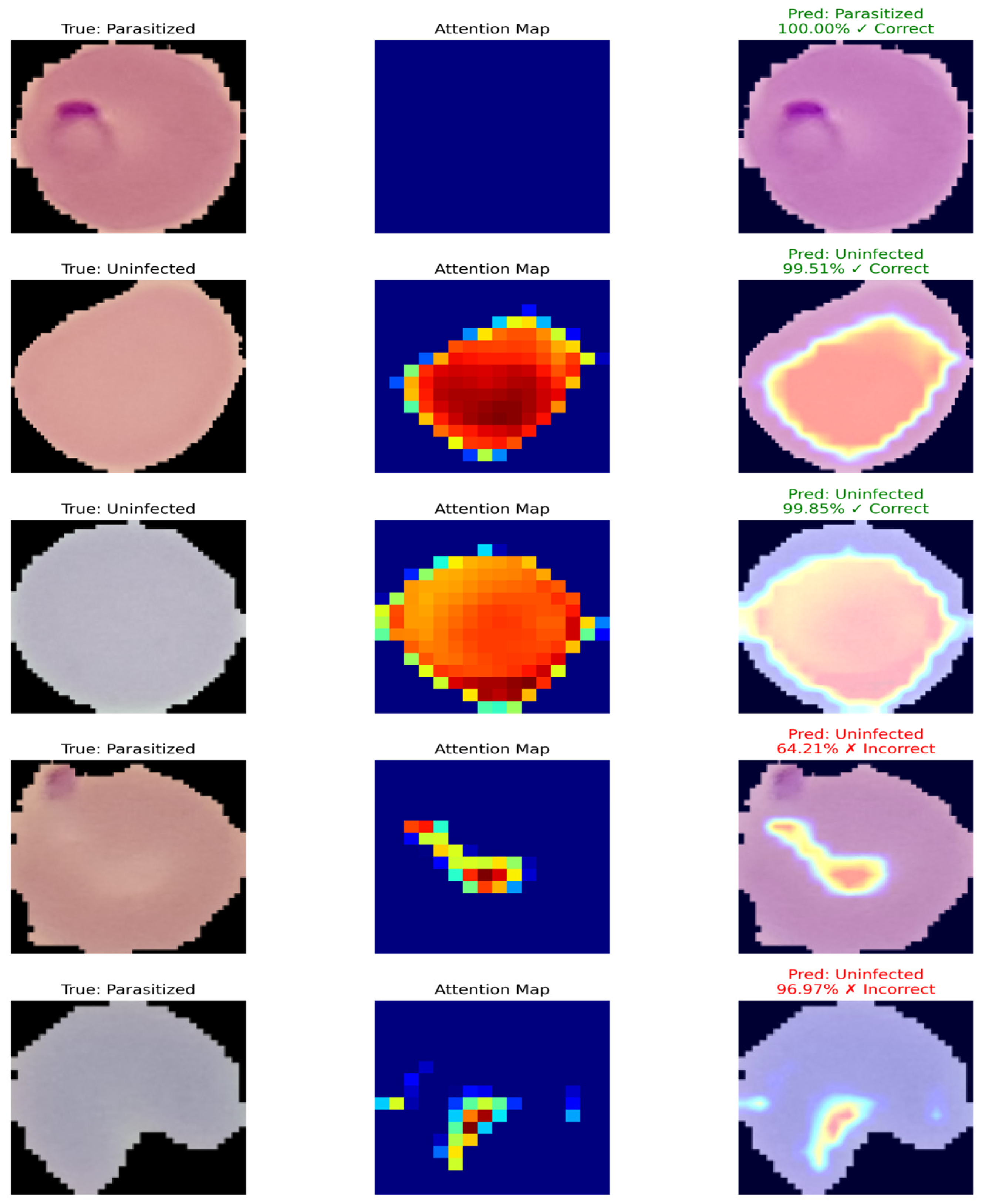

Figure 14 shows examples of the predicted results of the proposed model and the corresponding attention maps. The first, second, and third columns represent the true label of parasitized and uninfected cells, the attention map of the model (regions in which the model thinks are important to classify), and the predicted label with the confidence score, respectively. Green represents correctly predicted results and red represents incorrectly predicted results. The model correctly predicted most cells and captured the attention on the important region in most cases. However, for two parasitized cells, the model did not pay enough attention to the parasitized cell, which led to misclassification.

4.5. Comparison with Dataset-2

We assessed the cross-dataset transferability of the NOVA by applying it to the NIH Malaria Cell Images Dataset [

37]. The dataset consists of 27,558 images (13,779 parasitized and 13,779 uninfected) acquired from 150 infected patients and 50 healthy donors. The dataset was randomly split with stratification and a ratio of 80:10:10 for training, validation, and testing, respectively, with random seed fixed at 42 for reproducibility and perfect class balance in each split. All images were bilinearly interpolated to 224 × 224 × 3 pixels and normalized to [0, 1]. In addition to the interpolation and normalization, training images were randomly flipped, rotated (±20°), zoomed (±15%), translated (±10%), and shared (brightness/contrast, ±20%), whereas validation and test images only underwent the interpolation and normalization steps. We fine-tuned the pre-trained NOVA from Dataset-1 for 100 epochs with early stopping at epoch 47 on the NIH dataset. The optimization setup used Adam with an initial learning rate of 1 × 10

−4 and the ReduceLROnPlateau learning rate scheduler, a batch size of 32, binary cross-entropy loss, and L2 regularization (λ = 1 × 10

−4). The key limitation of this evaluation is the absence of patient-level metadata in Dataset-2, which precluded patient-stratified splitting and may result in the training and testing sets including cells from the same patients. All reported results represent cell-level classification performance, not patient-level diagnostic generalizability.

Table 7 shows the results of the selected deep learning architectures on the malaria cell dataset. From the conventional deep learning models, DenseNet169 and VGG16 gave good accuracy values of 94.19% and 94.92%, respectively, and the corresponding AUC values are 0.9824 and 0.9713. These models also demonstrate their good discrimination ability in terms of ROC between parasitized and uninfected cells. CNN, MobileNet, and EfficientNet-B7 also had very good accuracy, with a score of more than 95% in performance. However, InceptionV3, MobileNetV2, and EfficientNet-B1 showed poor accuracy and did not do well [

38,

39].

On the other hand, our proposed NOVA outperforms all the baseline models. It provides very high accuracy of 99.42%, where the precision, recall, and F1-score are above 99% and the area under the curve (AUC) is 99.08%. The proposed NOVA model has strong generalization power and demonstrated its ability to extract both local and global discriminative features in classifying malaria-infected and uninfected cells automatically.