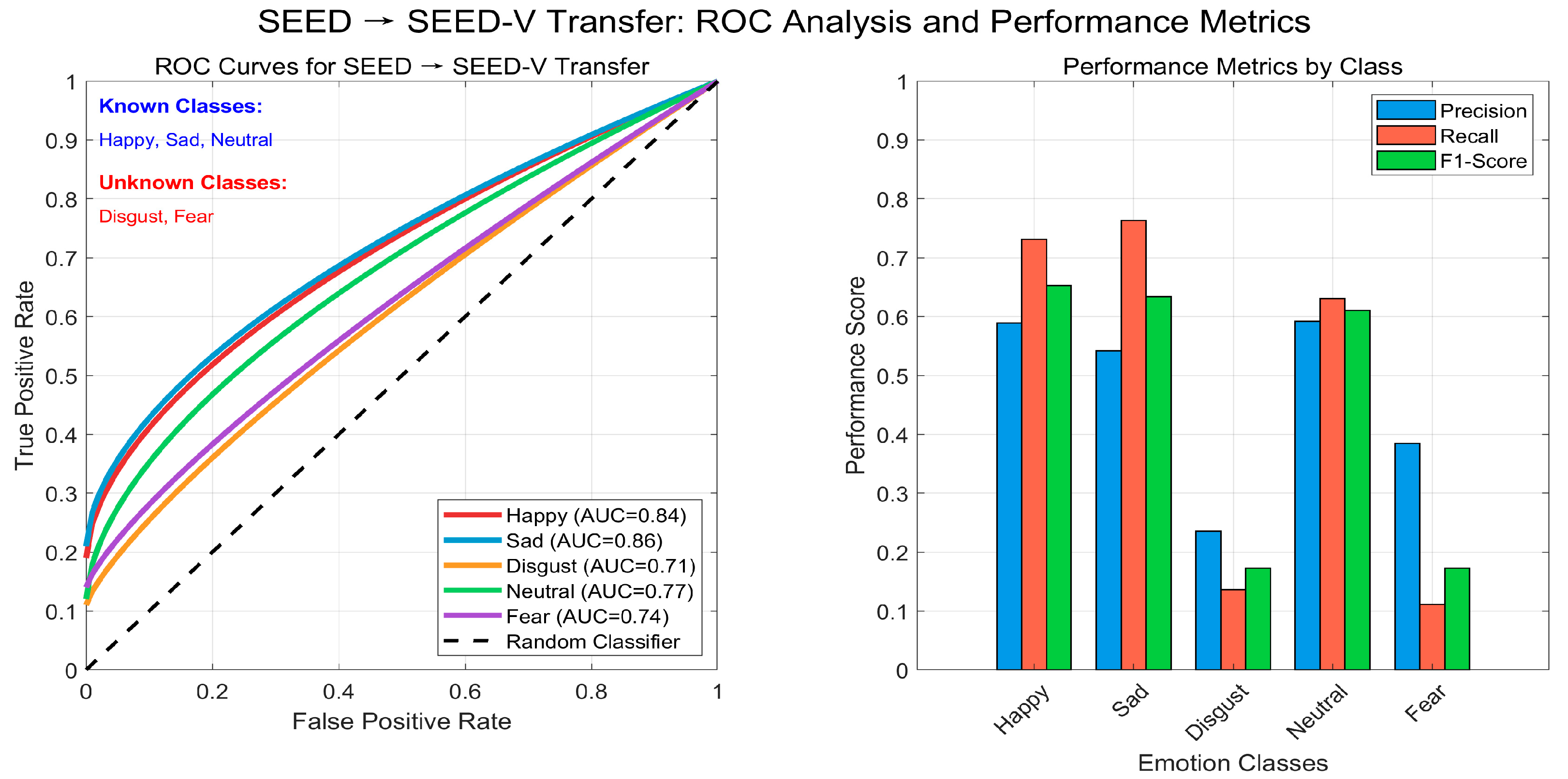

1. Introduction

In contemporary society, emotion recognition has been widely applied in various fields, impacting our daily lives profoundly. In the field of mental health, accurately and timely assessing an individual’s emotional state is crucial for improving psychological well-being [

1]. In education, observing students’ emotional states in the classroom helps educators gain insight into students’ learning situations, thereby adjusting teaching methods to enhance students’ learning effectiveness [

2]. Therefore, emotion recognition has been paid more and more attention, which has spawned a variety of emotion recognition methods. Among them, Electroencephalography (EEG)–based emotion recognition has shown promise for affective computing, mental-health monitoring, and human–computer interaction due to its outstanding stability and high detection accuracy [

3].

Yet moving trained models across people remains difficult: inter-subject variability, recording non-stationarities, and session effects induce substantial domain shifts. Due to the differences in emotional and physiological characteristics among different subjects, the EEG data distribution varies among different subjects [

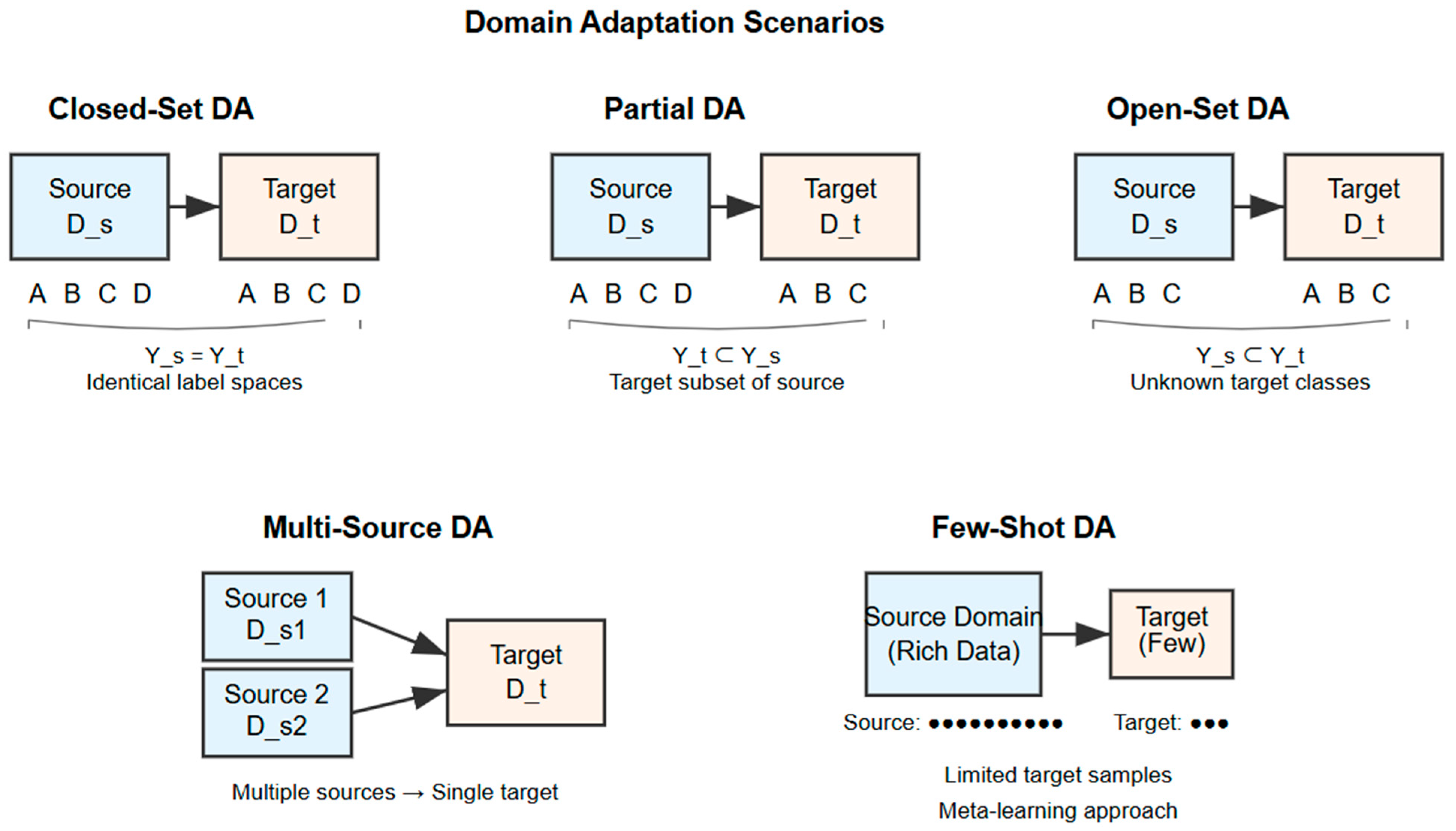

4]. It shows that the emotion recognition model trained with EEG data on a single subject may not achieve satisfactory results on a new subject, that is, there is a problem of model generality. In realistic deployments, the target domain may also contain emotion states absent from the source, creating an open-set scenario. In open-set domain adaptation (OSDA), the model must (i) align only the shared classes between domains and (ii) reject unknowns to avoid negative transfer. This setting is common in cross-dataset and cross-subject EEG but remains underexplored relative to closed-set transfer.

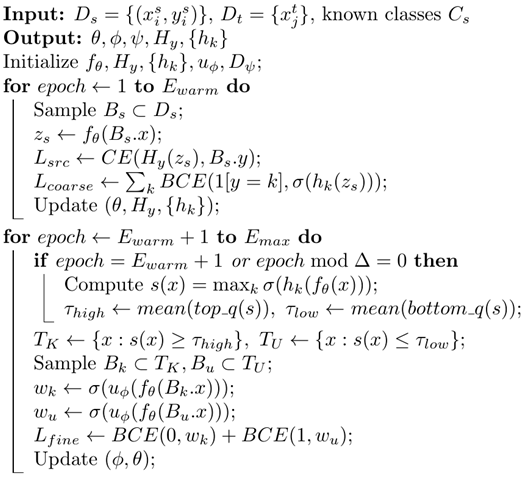

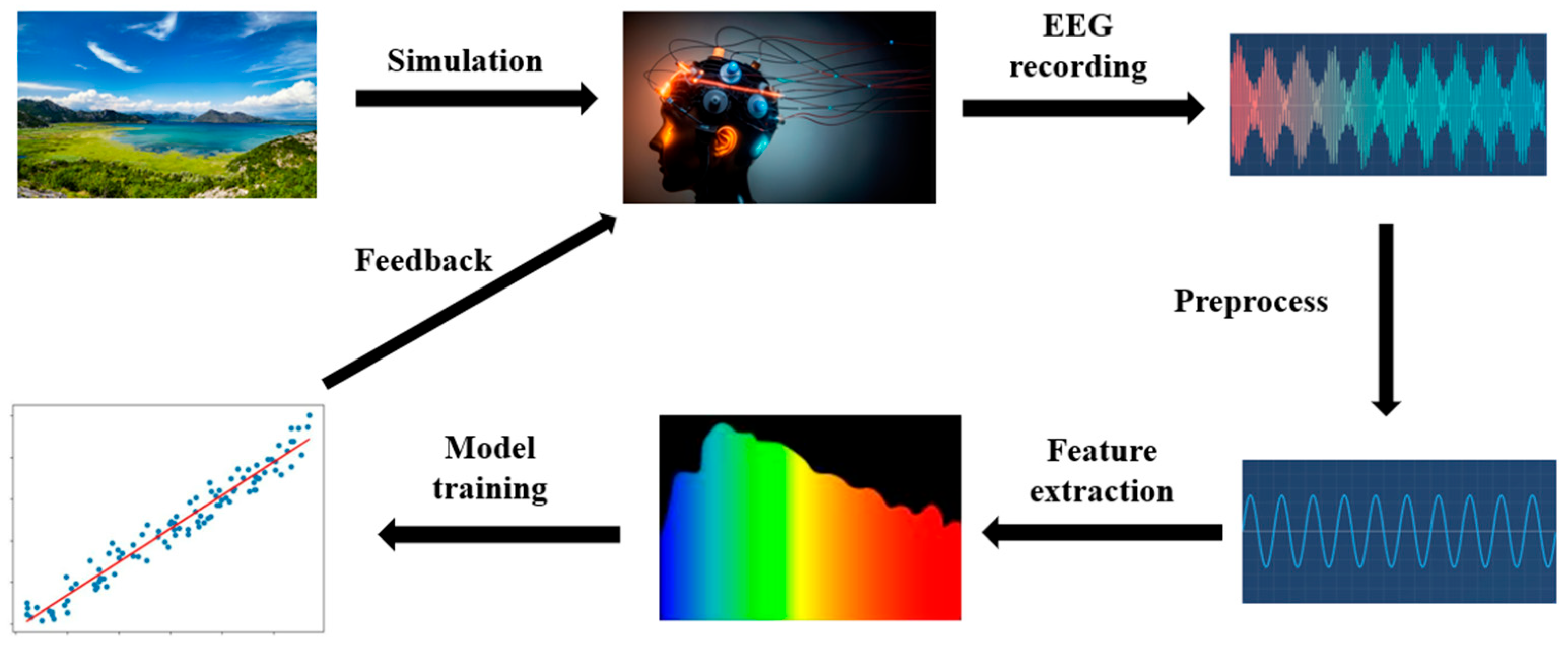

As illustrated in

Figure 1, the emotional brain–computer interface (EBCI) framework typically comprises several key stages, including stimulus presentation, electroencephalogram (EEG) signal acquisition, preprocessing, feature extraction, model training, and feedback. This iterative cycle enables the systematic modeling and analysis of EEG signals to infer users’ emotional states, thereby providing a foundation for advanced human–computer interaction.

To address this, many studies have used Unsupervised Domain Adaptation (UDA) techniques [

5]. These methods treat labeled EEG data from one subject as the source domain and unlabeled EEG data from another subject as the target domain. Then they train the model on the source domain to transfer it to the target domain.

Existing EEG approaches typically fall into three groups. Subject-dependent models achieve high accuracy but require labeled data per user and do not transfer. Closed-set domain adaptation reduces distribution shift but implicitly forces all target samples to match source classes, which misaligns truly novel target states. Finally, recent graph-based or temporal models improve representation quality but often rely on static inter-channel topologies and lack mechanisms to (a) encode neurocognitive priors that aid generalization, (b) capture evolving temporal salience, and (c) separate known vs. unknown target samples during adaptation. Moreover, evaluations frequently report overall accuracy alone, obscuring the trade-off between known-class performance and unknown-class rejection.

Although these existing methods effectively reduce the distribution differences in EEG data, they still have limitations. Because they usually assume that different subjects share the same label space, but the actual scene may encounter a different label space, especially when the emotional label space of the target domain is more than that of the source domain, that is, the scene of an open-set. In open-set EEG emotion recognition, not only do we need to address the distribution differences between subjects, but we also need to tackle the separation of known and unknown emotional classes due to different label spaces [

6].

We address these gaps with C2FDA-G, a cognition-prior spatio-temporal graph framework integrated with a coarse-to-fine open-set adaptation pipeline. This approach leads to the proposal of the C2FDA framework for EEG emotion recognition, which is designed to overcome the identified challenges in open-set domain adaptation. On the representation side, we construct a dynamic brain graph with graph convolution to learn data-driven channel affinities, combine it with temporal self-attention to weight informative segments, and fuse the streams via hierarchical cross-attention fusion (H-CAF). In parallel, we inject a cognition-prior branch from functional connectivity (e.g., PLV), then fuse prior- and data-driven embeddings to obtain discriminative, interpretable features stable across subjects.

Initially, the Coarse-to-Fine processing module performs coarse classification on the extracted EEG feature information, sorts all target domain samples based on the similarity of each target domain sample, and selects high and low probability score samples for fine classification, thus achieving the separation of known and unknown classes in the target domain. On the adaptation side, a bank of one-vs-class coarse heads ranks target samples by known-class plausibility; a fine unknown detector assigns an unknown probability w(x). We then perform instance-weighted adversarial alignment that emphasizes likely known target samples in the shared label space using a |Cs| + 1 classifier (with an explicit unknown class). A lightweight curriculum penalizes early high-confidence misclassifications, improving the stability of unknown rejection. Then, the Domain Adversarial module maps samples from the source and target domains to a shared label space, achieving alignment of the sample space. Finally, we input the EEG signal data processed by the two modules into the classifier to complete the EEG emotion recognition task.

In summary, our research makes the following contributions:

(1) We propose a Coarse-to-Fine processing module that can separate known and unknown emotional classes. This module solves the problem of negative transfer caused by the misalignment of unknown classes in the target domain with known classes in the source domain effectively.

(2) We propose a Domain Adversarial module that maps samples from the source and target domains to a shared label space for alignment of the EEG samples. This module effectively addresses the label space alignment problem in open-set EEG emotion recognition.

(3) Through extensive transfer experiments on three datasets, our experimental results demonstrate the reliability of the C2FDA method in open-set EEG emotion recognition.

As the field of semantic communication in 6G networks continues to develop, the focus is on transmitting task-relevant meaning rather than raw data. EEG-based emotion recognition is inherently semantic, as it extracts emotionally meaningful states from complex signals. The open-set scenario naturally aligns with semantic communication principles, where the system must determine whether incoming data belongs to the known semantic space or represents novel, unrecognized states. Our C2FDA framework addresses this by filtering semantically relevant emotional information and rejecting unknown samples, thus enhancing semantic efficiency and robustness in next-generation network applications. However, it is important to note that the connection to 6G semantic communication is conceptual, and this paper focuses primarily on the development and evaluation of the C2FDA framework for EEG emotion recognition.

3. Methodology

We begin by establishing the notation used throughout this work. Let denote the source domain with labeled samples, and represent the target domain with unlabeled samples. The label space relationship follows , where U denotes the set of unknown classes present only in the target domain. Our framework employs a feature extractor that maps inputs to d-dimensional representations. The coarse-stage processing utilizes a bank of one-vs-rest classifiers , each producing class-specific probabilities . The fine-stage unknown detector estimates the probability that a sample belongs to an unknown class. Finally, an open-set classifier performs classification, while a domain discriminator distinguishes between source and target domains. Having established the notation, we now proceed to detail the architecture and training procedure of our proposed C2FDA framework.

The method addresses two fundamental challenges in open-set domain adaptation: (1) distinguishing between known and unknown classes in the target domain, and (2) aligning only the shared classes while avoiding negative transfer from unknown samples. For the sake of illustration, we give some definitions of symbols. In the open-set EEG emotion recognition task, we have a source domain Ds containing ns labeled samples, denoted as , and a target domain Dt containing nt unlabeled samples, denoted as . Here, the label space size of the source domain is Cs. It is worth noting that the label space of the source domain is a subset of the label space of the target domain: The additional label space contained in the target domain is defined as the unknown class label space .

The source domain and the target domain come from different probability distributions , respectively. In domain adaptation, our probability distribution is also different: In open-set domain adaptation, our probability distributions are even more different: , where represents the distribution of target domain data in the shared label space. In summary, we can define the open-set EEG emotion recognition task as follows: . It is important to note that the label space of our source domain is a subset of the label space of the target domain.

3.1. C2FDA Model

Cognition-Prior Spatio-Temporal Graph Encoder—This component extracts discriminative and interpretable EEG features by combining dynamic graph convolution (DGC), temporal self-attention (TSAR), and hierarchical cross-attention fusion (H-CAF) along with a functional connectivity prior represented by the PLV graph.

Coarse-to-Fine Selector—This component ranks target samples based on their plausibility of belonging to the shared classes and then refines the decisions using a binary classification (“unknown vs. known”) fine head.

Instance-Weighted Domain Adversarial Alignment—This component aligns only the target samples likely to belong to the known classes to the source domain using a gradient reversal layer (GRL), while suppressing the alignment of unknown samples.

Open-Set Classifier—This component predicts over |Cs| + 1 classes, where the additional class explicitly represents the “unknown” category.

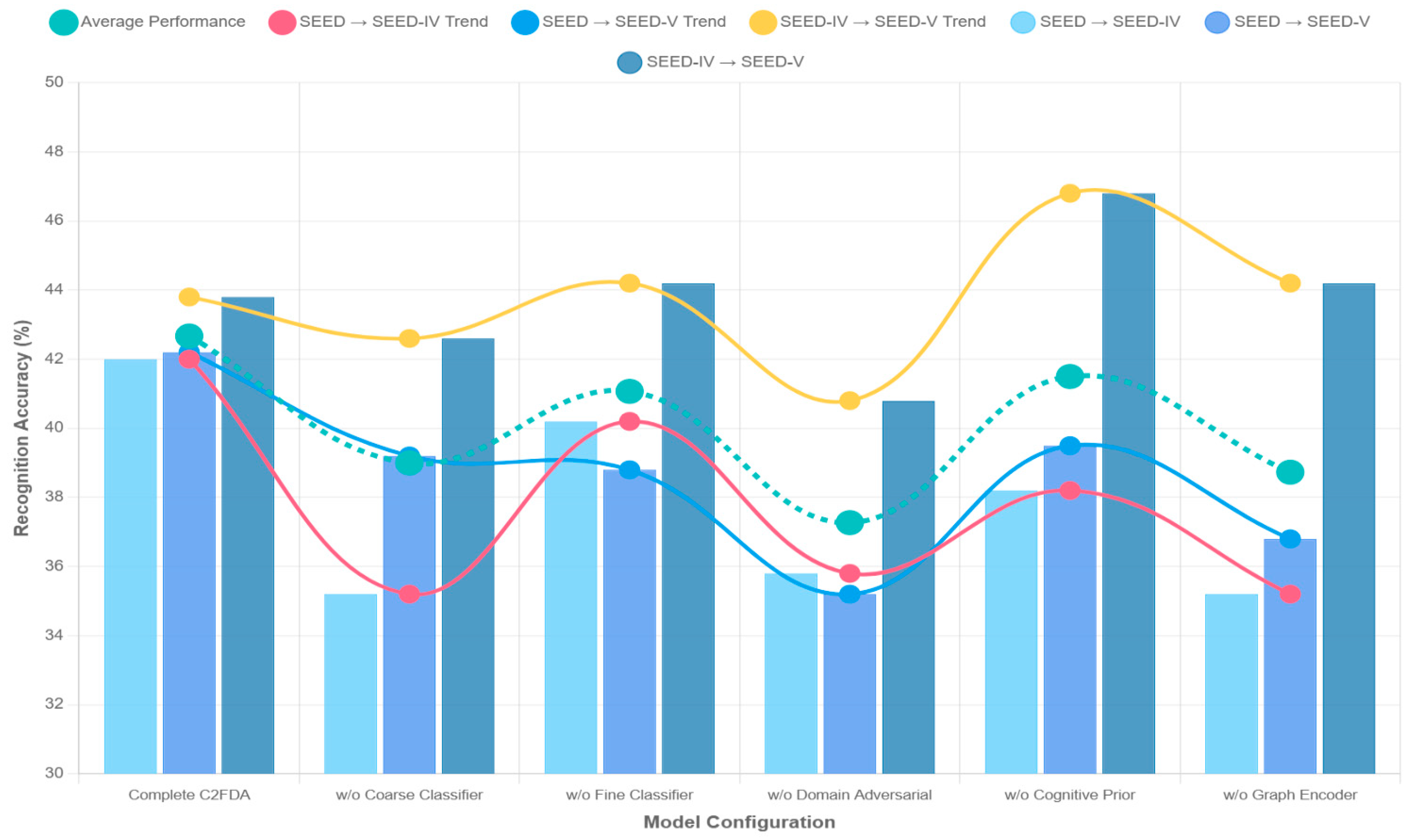

To address the aforementioned two issues, we innovatively propose A Coarse-to-Fine Open-set Domain Adaptation framework for EEG emotion recognition (C2FDA). The method framework of C2FDA is illustrated in

Figure 2. This method mainly consists of two modules: the Coarse-to-Fine processing module and the Domain Adversarial module. The Coarse-to-Fine processing module transforms the extracted EEG feature information from coarse-grained features to fine-grained features; in other words, its purpose is to separate known classes from unknown classes. The function of the Domain Adversarial module is to map samples from the source domain and target domain to a common label space, achieving sample space alignment. In

Figure 2,

represents the feature extractor of EEG signals,

and

represent the coarse classifier and fine classifier, respectively,

is the domain discriminator, which is also our Domain Adversarial module, and

is our final EEG data classifier. C2FDA-G is a variant of C2FDA that incorporates a cognition-prior spatio-temporal graph encoder into the feature extraction process, enhancing the model by explicitly integrating neurocognitive priors from EEG signals. Both models share the same core feature extraction approach, but C2FDA-G benefits from the added graph encoder for richer spatio-temporal dependencies.

3.2. Cognition-Prior Spatio-Temporal Graph Encoder

(a) Graph Construction We represent each EEG trial as a multi-channel DE feature map over frequency bands. Each band yields a graph , where are channels, edges, and the adjacency matrix.

To capture both neurophysiological priors and adaptive patterns, we construct a hybrid graph representation that combines domain knowledge with data-driven learning: Prior Graph —computed from PLV between channels over source data, encoding stable cognitive connectivity patterns.

Data-Driven Graph

—learned via attention-based affinity estimation that adapts to each sample.

The parameter α balances the contribution of cognitive priors (when α is large) versus adaptive learning (when α is small), allowing the model to leverage neuroscience knowledge while adapting to task-specific patterns.

We blend the two to form the adjacency for convolution:

(b) Spatial Encoding with DGC We apply graph convolutional layers over

to capture spatial dependencies:

where

is the degree matrix,

are learnable weights, and

is an activation function.

(c) Temporal Self-Attention (TSAR) For each channel representation, TSAR assigns attention weights across time steps:

where

are learned projections. This emphasizes temporally salient EEG segments.

(d) Hierarchical Cross-Attention Fusion (H-CAF) Spatial and temporal streams are fused using cross-attention to produce the final embedding for each trial.

3.3. Hyperparameter Tuning for α and λ

In this section, we explain the selection of the hyperparameters α and λ, which are essential for the performance of the C2FDA framework. The parameter α controls the balance between cognitive priors and adaptive learning, while λ adjusts the weight of the entropy loss in the domain adversarial module. The two parameters determine how the model blends prior knowledge and data-driven learning, ensuring effective separation between known and unknown emotional classes.

To blend the cognitive prior graph (

) and the data-driven graph (

), we use the equation:

The parameter α was tested within the range [0.1, 1.0], where larger values favor prior knowledge and smaller values prioritize adaptive learning. Similarly, λ controls the entropy loss contribution and was varied within [0, 1], with higher values placing more emphasis on rejecting unknown classes. The adjusted adjacency matrix is given by:

We used k-fold cross-validation to select the optimal values for both α and λ, evaluating performance based on recognition accuracy for known classes and the ability to detect unknown emotional states. The impact of these hyperparameters is significant. Larger α values improve known-class recognition but reduce flexibility in detecting unknown emotional states, while smaller values enhance detection of novel classes. For λ, higher values strengthen unknown class rejection but may overfit known classes, while lower values improve detection of unknowns. This tuning process ensures robustness and reproducibility in open-set EEG emotion recognition tasks.

3.4. The Coarse-to-Fine Processing Module

Coarse Stage: We deploy a bank of

one-vs-class classifiers

producing logits

and probabilities

. For target sample

, define:

To distinguish known and unknown classes in the target domain, we put forward the Coarse-to-Fine processing module. We introduce a coarse classifier

, consisting of

classifiers. The coarse classifier measures the similarity between each target domain sample and each source domain class. Each classifier is independent, with different functionalities; each classifier can only classify specific emotion classes. The loss function of the coarse classifier is defined as shown in Equation (1):

In Equation (10),

represents the cross-entropy loss of the coarse classifier. When

coarse,

= 1; otherwise,

= 0. Each

returns the probability score

of each target domain sample being classified as the known class coarse. Thus,

can be used to measure the similarity between samples in the target domain and the known class. A higher probability score indicates a higher likelihood of the sample belonging to class coarse. Empirically, known class samples in the target domain tend to have higher probability scores compared to unknown class samples. Therefore, we can use the maximum probability score of each sample, p1, p2, …, p

, to represent the similarity between each target domain sample

and the source domain, as shown in Equation (2):

To avoid manual hyperparameter tuning and ensure robustness across different degrees of openness, we introduce an adaptive thresholding mechanism based on quantile statistics:

Figure 3 Coarse-to-fine sample separation via adaptive threshold selection. Target domain samples are stratified into three regions based on similarity scores: high-confidence known sample region (green) for domain alignment; ambiguous sample region (gray) excluded from training; and high-confidence unknown sample region (red) for novel class detection. The high and low adaptive thresholds are automatically determined without hyperparameter tuning. This approach is conceptually similar to the Separate to Adapt (STA) method, which employs a coarse-to-fine separation mechanism to progressively distinguish between known and unknown classes based on sample similarity. In STA, sample importance is adaptively weighted during feature distribution alignment, and unknown target samples are excluded from the alignment process to prevent negative transfer. While STA addresses domain adaptation across varying levels of openness, this work utilizes adaptive threshold selection to specifically tackle the challenges of open-set EEG emotion recognition without the need for manual hyperparameter tuning.

This partitioning strategy creates three distinct regions: high-confidence known samples (), high-confidence unknown samples (), and an ambiguous region that is excluded from alignment to prevent negative transfer.

After employing such a measurement method, known class samples in the target domain will indeed exhibit high similarity with the source domain. Similarly, samples of unknown classes in the target domain will show low similarity with the source domain.

Therefore, based on the magnitude of similarity for each target domain sample, we can sort all target domain samples and select those with particularly high or low probability scores to train the next-stage fine classifier . Although this selection method may seem simplistic, the chosen samples exhibit high confidence and similarity. Additionally, since we no longer need to manually select hyperparameters or use optimization tools, this approach is robust to varying degrees of openness.

To further refine sample selection, we categorize samples into three groups based on the magnitude of similarity probability scores: highest probability scores, moderate probability scores, and lowest probability scores. Then, we use the average of the highest probability scores, denoted as , as the upper limit for known class samples in the target domain. Thus, when a sample’s similarity probability score satisfies ≥ , we classify it as a known class. Similarly, we use the average of the lowest probability scores, denoted as , as the lower limit for unknown class samples in the target domain. Hence, when a sample’s similarity probability score satisfies ≤ , we classify it as an unknown class.

Fine Stage: From the extreme quantiles (top , bottom of ), a binary fine classifier is trained to predict , the probability that is unknown. While the coarse stage provides initial separation, the fine-stage binary classifier performs precise unknown detection by learning from the high-confidence samples identified in the coarse stage.

As illustrated in

Figure 4, the C2FDA framework adopts a hierarchical processing strategy. First, a graph-based feature extractor (which incorporates the cognition-prior spatio-temporal graph encoder in C2FDA-G) processes EEG signals from both the source and target domains. This feature extraction approach combines a simpler feature extractor (

) in C2FDA and a more complex graph encoder in C2FDA-G, both of which share the same fundamental task of extracting relevant features from the EEG signals. Then, the coarse-to-fine separation module performs progressive filtering on the target samples. Specifically, the coarse separation layer ranks the samples based on their similarity to known categories, while the fine separation layer conducts binary classification to distinguish between known and unknown samples. Finally, the domain adversarial module aligns distributions only for the samples that are likely to belong to known categories, thereby avoiding negative transfer caused by unknown samples. This allows the final classifier to achieve open-set emotion recognition with unknown category detection.

Once the coarse classifier

selects high probability known class samples and low probability unknown class samples, denoted as

, we can further feed these selected samples into the next-stage fine classifier

, to separate known and unknown class samples in the target domain. We label the samples that have been separated from the target domain, denoted as

∈

, as

. Known class samples are labeled as

= 0, while unknown class samples are labeled as

= 1. The loss function of the fine classifier

is shown in Equation (3):

The unknown probability w(x) serves as an instance-level confidence measure, enabling selective alignment where only samples with low w(x) values (likely known) participate in domain adversarial training. Through the Coarse-to-Fine processing module, we can separate EEG signal samples of known and unknown classes in the target domain.

Curriculum Learning: Inspired by step-penalty reinforcement learning, we weight early confident mistakes more heavily in the first K epochs:

Through the Coarse-to-Fine processing module, we can separate EEG signal samples of known and unknown classes in the target domain.

From a semantic communication perspective, the coarse-to-fine mechanism acts as a semantic filtering process: it transmits only emotionally relevant information (known classes) while suppressing irrelevant or unknown samples. This aligns with the goal of semantic communication in 6G systems, where only semantically valid data is prioritized for transmission, thereby reducing bandwidth overhead and improving task efficiency.

3.5. The Domain Adversarial Module

Traditional domain adaptation aligns all target samples with the source distribution, leading to negative transfer when unknown classes are present. Our instance-weighted alignment strategy addresses this by selectively emphasizing likely known samples.

In this section, we first present the classification error function for the source domain, as shown in Equation (4):

where Ly represents the cross-entropy loss function, and Hy represents an extended classifier with |Cs| + 1 classes, where |Cs| + 1 includes |Cs| known emotions from the source domain and 1 unknown emotion from the target domain. Therefore,

returns the probability of each sample corresponding to the |Cs| known emotions.

Next, we focus on aligning the features of samples from the source and target domains. In this step, we map the features from both domains to a shared label space, denoted as Cs. Instead of directly inputting the output of

into discriminators for known and unknown classes, we append a softmax layer to the output of

, which serves as the input to the discriminators. This softmax layer generates soft instance-level weights, denoted as

, where higher values of

indicate a higher probability of the sample belonging to the unknown class. Hence, we can utilize

to define the weighted loss for Domain Adversarial adaptation of feature distributions in the shared label space Cs, as shown in Equation (5):

In addition, we also need to select samples of unknown classes from the target domain to train the feature extractor Hf. Based on the soft instance-level weights

, we can measure the separation between known and unknown classes. We define the weighted loss for distinguishing unknown classes as shown in Equation (6):

where

represents the unknown emotion class. Through training, we assign all target samples with larger weights

to the unknown emotion class. Similarly,

represents the probability that classifier Hy assigns target samples to the unknown class.

We also enhance the decision boundary between domains by computing the loss for minimizing the entropy of known classes in the target domain, denoted as Le. This is achieved by enhancing weights with the following formula, as shown in Equation (7):

In Equation (7), E represents the entropy loss, specifically expressed as It is important to note that our goal is to minimize the entropy of target samples predicted as known emotion class. Therefore, we use as the instance-level weight parameter for entropy minimization.

The adversarial alignment in C2FDA ensures semantic consistency across domains, akin to semantic fidelity in 6G-oriented communication systems. By weighting known samples more heavily, the model mimics a semantic-aware transmission protocol that prioritizes meaningful emotional states over noisy or unknown inputs.

3.6. Open-Set Classification and Loss Functions

Beyond global domain alignment, we introduce prototype-based fine-grained alignment to enhance intra-class consistency between source and target domains:

To stabilize the training process and prevent early convergence to suboptimal solutions, we employ a curriculum learning strategy that penalizes confident misclassifications more heavily in early training stages:

where e is the current epoch,

is the transition epoch, and γ ∈ (0,1).

Our final objective function integrates all components through a carefully designed multi-term loss that balances source supervision, sample separation, domain alignment, and regularization.

The open-set classifier

outputs

logits, with the last logit representing “unknown.” We optimize the total loss:

Each loss term addresses a specific aspect of the open-set domain adaptation problem: ensures source discriminability, and enable known/unknown separation, performs selective alignment, enhances intra-class consistency, promotes unknown rejection, sharpens decision boundaries, and provides training stability.

Where each term corresponds to supervised source classification, coarse/fine stage training, adversarial alignment, target entropy minimization, and curriculum penalty.

3.7. Objective Function

The optimization of our multi-component objective requires a progressive training strategy that alternates between sample separation and domain alignment to ensure stable convergence.

We divide the training into two progressive stages: (1) sample separation, where target data are partitioned into likely known and likely unknown subsets based on confidence scores, and (2) domain adversarial adaptation, where only the reliable known subset is aligned with the source domain distribution. By alternating between these two stages, the model gradually adapts target samples of known classes while rejecting unknown ones.

Algorithm 1 summarizes the procedure. In the first step, we train the feature extractor and classifier with source supervision, while auxiliary coarse classifiers provide confidence scores for sample separation. Target samples with high scores are treated as potential known data and passed to the fine classifier , whereas low-score samples are considered likely unknown.

This alternating optimization strategy prevents the premature alignment of unknown samples while gradually improving the separation of known and unknown classes, leading to more robust open-set domain adaptation performance.

| Algorithm 1: Coarse-to-Fine Open-Set Domain Adaptation (CF-OSDA) |

![Electronics 14 04833 i001 Electronics 14 04833 i001]() |

Step 1: First, we train the feature extractor Hf and classifier Hy on the source domain. Additionally, we utilize each class of emotion samples in the source domain to train the coarse classifiers

, where coarse

. Next, we select target domain samples with high and low probability scores, similar to those in the source domain, to train the fine classifier

. Here, we denote the parameters of

as

, respectively. The optimal parameters

= 1 can be found using the following equation, as shown in Equation (8):

Step 2: In this step, we primarily perform domain adversarial adaptation to align the feature distribution of known classes in the target domain with that in the source domain. Additionally, we use data from unknown classes to train Hy as additional classes. In this step, we continue training the classifiers with source samples to retain knowledge relevant to known class emotions. We denote the parameters of the domain discriminator

as

. The optimal parameters

can be obtained using the following two equations, as shown in Equations (9) and (10):

where λ is a hyperparameter used to balance the entropy loss.

Through the proposed C2FDA model, we can effectively separate known and unknown class data in the target domain. Step 1 rejects unknown class emotion data to avoid interference from unknown class emotions in Step 2, where domain adversarial adaptation aligns the feature distributions of samples between the source and target domains. Since there is no manual selection of threshold hyperparameters throughout the process, the disadvantage of tuning parameters when the openness changes in real scenarios can be avoided.

In summary, the biggest problem of an open-set task is the separation of known emotions and unknown emotions. In order to solve this problem, we propose the C2FDA method. The C2FDA method uses a gradual method to find two types of samples with high scores and low scores during training. Because the prediction results of the samples with high scores will be more accurate, it is also conducive to training the classifiers of known classes, while the samples with low scores tend to be the samples of unknown classes, so we can extract these samples to train the classifiers of unknown classes. By this means, we can well separate the known emotion from the unknown emotion. At the same time, it also solves the impact of the negative migration of wrong samples.