1. Introduction

Electric induction motors are ubiquitous across all industrial sectors, playing a key role in processes where safe and continuous operation is critical. Valued for their robustness, reliability and relatively low maintenance costs, these motors are nonetheless susceptible to faults and degradation, particularly in demanding industrial environments. To ensure the reliability and continuous availability of motors in critical settings, such as those installed in industrial tunnels, health monitoring is essential. In this context, non-invasive methodologies like Motor Current Signature Analysis (MCSA) have gained significant importance.

Despite the potential of MCSA, its applicability in real-world industrial scenarios presents significant complexities and limitations. A primary challenge is that MCSA studies have been predominantly conducted in laboratories, on motors with known defects and under controlled conditions. Variations in real industrial operating conditions, such as variable load and non-constant speeds, can make fault recognition difficult. It is a common hypothesis that the lack of studies conducted on real industrial cases complicates the application of MCSA methods, due to the immense variability of fault patterns that manifest in these environments. This research investigates the use of MCSA for monitoring the health of industrial induction motors in tunnel environments. It aims to determine whether non-invasive methods like MCSA are suitable for real-time monitoring under these circumstances. The variability in motor characteristics and operating conditions poses challenges for defining thresholds and identifying consistent patterns. The study seeks to overcome these issues and explore whether more industrial case studies can reveal common patterns, enabling more accurate health assessments in the future.

This paper presents the outcomes of a collaborative project between the authors and Autostrade per l’Italia S.p.A. focused on condition monitoring of highway tunnel ventilation fans. Conducted intermittently from 2020 to late 2024, this collaboration produced distinctive findings, challenges and lessons that are summarized and discussed in the present study.

Initially, the case of tunnel fans will be described: a brief feasibility study of the condition monitoring applied in this context is presented, including the motivation and issues to implement it. A remark will cover the diagnostic signals chosen and why they are considered more effective for the case.

Measurements were conducted using both portable and permanently installed equipment. While the type of permanent devices employed are described later, particular emphasis is placed on the installation strategy, which proved to be as relevant as the equipment itself. In fact, thanks to peculiar characteristics and conditions of the electrical systems that fed the fans and the application of MCSA for diagnostics, it was possible to monitor all fans in a tunnel by permanently installing only a few components.

The types of data elaborations (and algorithms used) chosen for the case will be described, along with the reasons why they were chosen. Though both frequency and time-frequency domain analyses have been carried out during the project, in this paper only frequency domain results are presented, for brevity.

The diagnostic results will be then presented and discussed; information given by the fans and tunnels’ maintenance staff will be considered and compared to the diagnostic output obtained, showing the potentialities of the techniques.

This study examines whether expanding research on industrial use cases can reveal common patterns in MCSA results, thereby supporting more accurate assessments of induction motor health in future industrial applications.

2. State-of-the-Art: Diagnostic Techniques

Diagnostic techniques for the condition monitoring of electric motors represents a critical domain to guarantee the reliability of industrial systems. These diagnostic techniques have recently experienced extraordinary growth and development, as can be seen from the increasing number and quality of papers published on this argument.

Indeed, predictive maintenance, increasingly widespread across all fields, requires the use of reliable diagnostic tools, implementable with non-invasive sensors for online use. These sensors measure the operating variables that need to be monitored to predict the conditions of the motors. Compared to the past, these sensors are nowadays more reliable, miniaturized and cost-effective, and therefore suitable for electric motors of all sizes, even small and medium-powered ones.

The goal of diagnostics is to identify the fault that will lead to a failure and estimate its severity. The evolution of diagnostics is prognostics, which is based on the continuous monitoring of the motor’s operating variables and uses this information to predict the time until a failure occurs, i.e., the Remaining Useful Life (RUL) [

1]. In other words, prognostics aim to predict the evolution of a fault and when the machine will no longer function as designed or desired [

2]. Prognostics can be used to assess the rate of degradation and can allow the motor to continue operating normally until the time of failure; it can also reduce costly and unnecessary maintenance and unexpected failures [

3].

All the case studies reported in this paper concern squirrel cage induction motors supplied at low voltage (<700 V). In these motors, faults mainly occur in the stator winding, the bearings, the airgap (eccentricity), the rotor cage bars and rings, and, more rarely, in the mechanical load, the auxiliaries and the laminated stator and rotor core [

4]. The operating variables that can be measured and analyzed to determine the state of health of these motors can be electromagnetic (current, external stray flux, voltage, electric power), mechanical (vibration, sound) and of other origin (e.g., temperature).

Traditionally, invasive techniques, such as vibration analysis, have been extensively used for diagnostics, especially for bearing faults which are directly correlated with vibrations. However, these methods are often difficult and costly to implement, requiring the installation of various sensors in precise locations and incurring high installation and maintenance expenses. The recent trend in diagnostics is to prefer an electromagnetic signal instead of vibration, because often the former is already measured by means of the electrical drive for the control of the motor; moreover, most of the electromagnetic signals can be collected far from the motors, at their terminals on the switchboard, when the motors are not accessible [

5,

6,

7]. In particular, in the last few years, the analysis of the external stray flux around the motor has become increasingly popular, alone [

8,

9] or combined with the analysis of the stator current [

10]. These signals can be measured in steady state or during the starting transient and can be processed by means of different techniques, mainly divided into frequency-based analyses [

11] and time-frequency analyses [

12]: the former are mainly based on the classical Fast Fourier Transform (FFT), whereas the latter include Short-Time Fourier Transform (STFT), Dragon Transform (DT) and Short-Time Minimum-Norm.

When the measured signal is the current of one phase, its frequency-based analysis is known as Motor Current Signature Analysis (MCSA). The operating principle of MCSA is based on detecting fluctuations in the stator current spectrum, which are induced by asymmetries in the air-gap magnetic field caused by internal faults, such as broken rotor bars (BRB). If all the three phase currents can be measured simultaneously with three different probes connected to the same data acquisition board, MCSA is frequently integrated with advanced methods such as the Park’s Vector Approach. Park’s Vector approach is also known as

Id −

Iq analysis, as it involves the study of the three-phase stator currents using their orthogonal components, i.e.,

Id (direct current) and

Iq (quadrature current) [

13]. Instead, if all the three phase voltages are collected, the Zero Sequence Voltage (ZSV) can be calculated and analyzed [

14].

Moreover, with the voltage signals, the Instantaneous Power Signature Analysis (IPSA), i.e., the study of the instantaneous power signal (given by the instantaneous current multiplied by the voltage) in the time or frequency domain of one or all the three motor phases can be performed [

15,

16,

17]. Note that with three phases voltage sensors, grid supply voltage unbalances can be detected, avoiding false positives or false negatives in the detection of many faults [

18].

Besides the signal processing methods presented above, Artificial Intelligence (AI) techniques can be helpful for automatic fault identification and classification. For example, in [

19] an AI-based technique is used to automatically diagnose various types of bearing faults and load anomalies using stator currents measured on induction motors. These signals are processed to obtain time-frequency representations, which are then elaborated by five pre-trained Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs). The results demonstrate the ability of the electromagnetic signals to detect bearing faults and mechanical anomalies. Furthermore, the CNN has been shown to automatically distinguish bearing defects from their healthy condition. The main challenge for broad large-scale AI adoption is the lack of sufficient labeled data across different operating environments, a challenge that reflects real-world conditions where datasets are collected from diverse motors and settings. A persistent issue is the lack of generalization, meaning models often fail to predict on new datasets or different systems [

20].

Other examples of AI applied to fault detection include the so-called Explainable (or interpretable) Artificial Intelligence (XAI). For instance, in [

21], an innovative neural network, called Transparent Operator Network (TON), was introduced. The network proposed is composed of several layers. For the processing stage, the signal operator layer (SOL), that applies a Morlet Wavelet Filter, is applied. In the proposed work, the analysis had good results in finding bearing faults if compared to other techniques that use a higher number of parameters in the training of the network.

Another application of XAI is proposed in [

22], where the authors introduce the Transparent Information Fusion Network (TIFN) applied to the fault detection in electrical machines. In this case, the network combines information from different sensors to train the network, achieving good results in detecting the bearing fault.

Despite the interesting results achieved in the methods mentioned above, the analysis of this work focuses on the classical harmonics found in the current spectrum through the FFT, since the purpose of the work is to give hints about the evolution of several faults through a limited number of sensors.

Induction motors are widely used in critical applications such as transportation or power generation because they are robust and require minimal maintenance. However, their location in these environments often makes it difficult to place traditional monitoring methods, such as vibration sensors. This combination of high operational importance and limited accessibility highlights the need for non-invasive techniques like MCSA. Validating MCSA in real-world scenarios is essential to ensure its reliability and effectiveness, particularly in challenging environments such as tunnels (the asset monitored in this work). Moreover, its cost-effectiveness represents a key factor for the large-scale adoption of AI-based diagnostic methods in industrial settings.

3. Tunnel Fans’ Case

As mentioned before, the case presented in this paper is about highway tunnel fans. These machines are usually axial ventilators fixed on the tunnel ceiling. The appliances are used for the following two different purposes:

The electrical systems feeding these appliances have some sophisticated characteristics to satisfy the two purposes of the fans. All the motors have some vibration sensors and thermistors installed. However, the electrical system reacts differently depending on which case is occurring: in “air-quality” operations, with a high temperature or vibrations the machines stop; in an emergency the machines are driven even with high temperature and vibrations potentially until their self-destruction. To control this machine state, Safety Programmable Logic Controllers (PLCs) are adopted [

27].

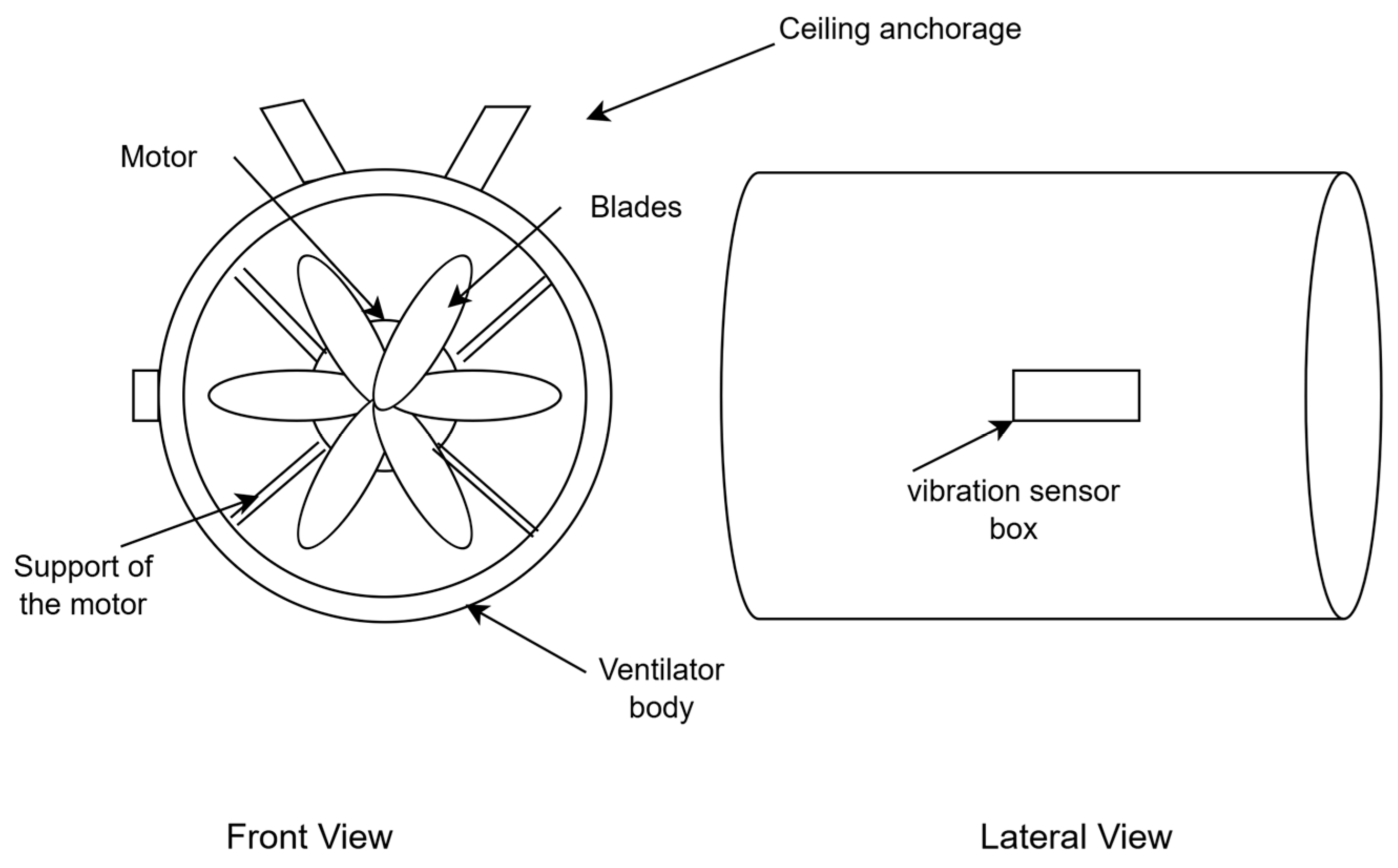

A preliminary study was conducted to determine if thermal and vibration sensors (especially the vibration ones) could be used for adequate condition monitoring of the electrical motor and fans. However, it turns out that vibration sensors are industrial sensors with an output proportional to the RMS value of the vibration, in form of speed. The location of the vibration sensors, moreover, is often on the external fan chassis (a representation of the fan is reported in

Figure 1).

Vibration sensors in industrial fans typically provide only RMS speed values, which does not allow spectral analysis and therefore limits early-stage fault localization. These sensors are often mounted on the fan chassis (see

Figure 1), not on the motor, and the spring-mounted motor further dampens the signal. Speed-based vibration is also limited to low frequencies (<1000 Hz), missing key fault signatures [

28]. Due to these limitations, vibration sensors were excluded from our diagnostics. Motor access is highly restricted, as maintenance requires traffic interruption or rerouting. This made installing additional sensors—such as high-resolution vibration or stray flux sensors—impractical. Estimating the costs, installing and maintaining sensors, along with the power supply and data transmission infrastructure, would entail, for each vibration-based system installed onto a single fan, a cost comparable to that of the entire system for MCSA installed in the electrical cabin (that will be described in the next paragraph).

Therefore, monitoring of motor currents in the motor control rooms has been chosen for the proposed work. Since the control rooms are located outside the tunnels, the acquisition of the electrical signals is more accessible and less disruptive compared to the acquisition of vibration signals. Note that the difficulty in operating the maintenance, due to the necessity to modify the vehicles’ transit during these operations, is one of the main reasons that brought the company to ask for a study about condition monitoring and predictive maintenance techniques.

4. Tunnel Characteristics and Measurement Setup

4.1. Tunnels

The experimental measurements were conducted in two highway tunnels located in central Italy. Both tunnels are twin-tube configurations, meaning each carriageway is housed in a separate bore and both are equipped with 14 axial jet fans [

29,

30]. Tunnel A uses a motor and fans from a different brand than Tunnel B, as summarized in

Table 1.

These tunnels were selected as candidates because they met key technical requirements:

Independent control of each fan motor.

Direct power supply from the electrical grid (no inverter), enabling accurate spectral analysis.

Accessible control cabin located outside the tunnel in an enclosed space, allowing measurements without traffic disruption.

Table 1 summarizes the main characteristics of the tunnels and their ventilation systems.

4.2. Instrumentation Characteristics and Installation

For the measurement of the machine stator current for diagnostic purposes, the following components are used:

Rogowski current clamps (one for each phase).

Metallic tips and cable for voltage measurements.

A digital acquisition board (DAQ) with anti-aliasing filter.

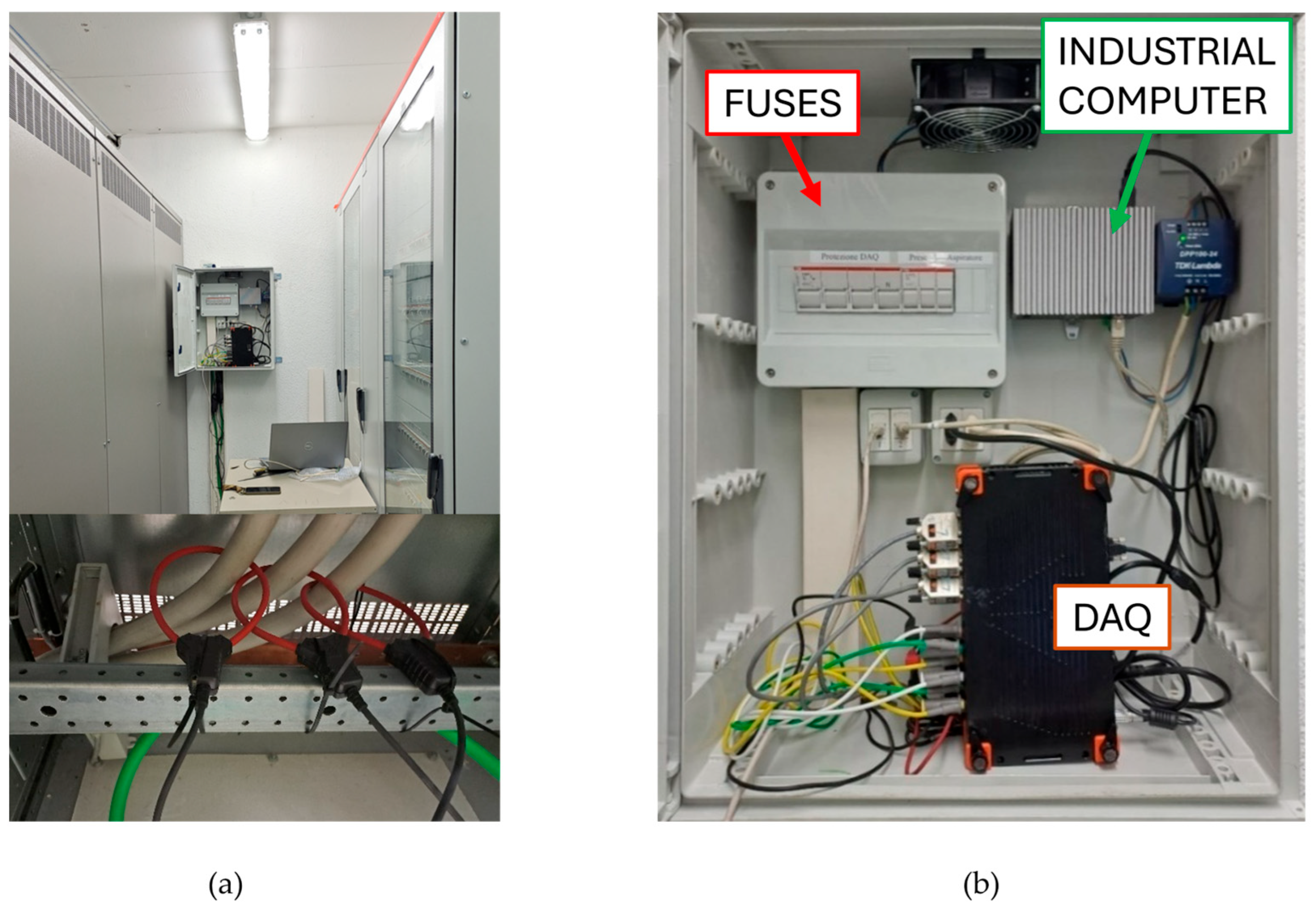

An industrial computer (for data storage and first processing).

The DAQ used in this project is the SIRIUSi-4xHV-4xLV with 8-channel, from DeweSoft company, Trbovlje, Slovenia (

Figure 2); this multi-channel system enables the measurement of three-phase currents for MCSA (Motor Current Signature Analysis) and three voltages up to 1000 V. This DAQ has an extremely performant dynamic range of about 150 dB, since 24 bits are used for discretization of the signal under the sampling frequency of 1 MS/s [

31]. So, a very high SNR (Signal to Noise Ratio) is achievable with this equipment.

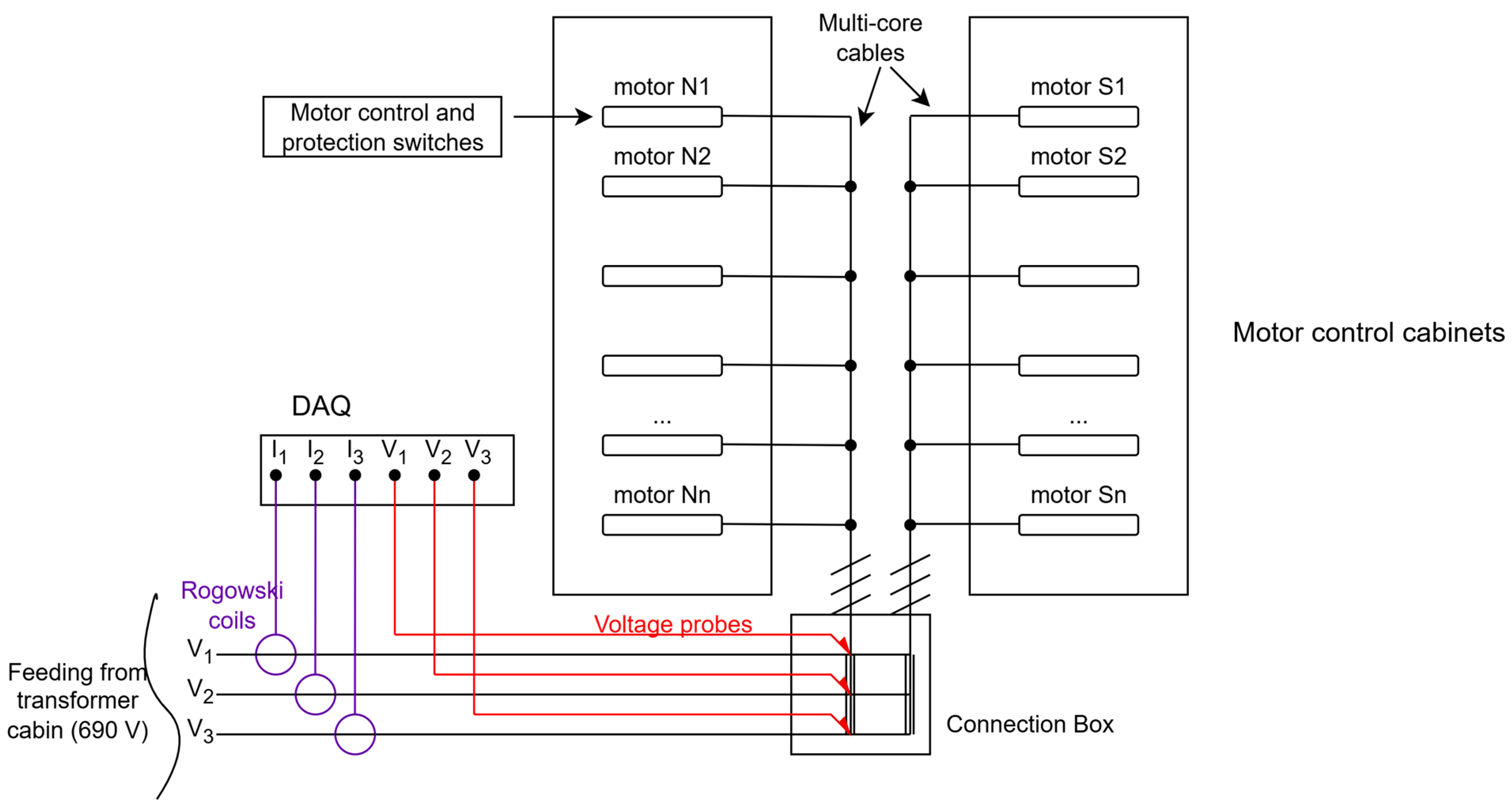

The acquisition system has been thought to be installed permanently or semi-permanently (some months) and to be remote controlled. To satisfy this requirement, an industrial computer is installed with the DAQ. Moreover, the internet connection has been setup to remotely control the acquisitions. However, installing similar hardware for every motor to be monitored would have highly increased the total costs unacceptably. Therefore, the following alternative installation has been idealized and practiced.

Since the motors are most of the time non-energized, and since the electrical system had a configuration with a three-phase line dedicated only to the motors feeding (no other auxiliary connected to the line), this setup required the installation of only one DAQ and computer to monitor all the motors of the tunnel. In fact, the motors can be energized one at a time, storing the data in the computer. This operation is usually carried out by maintenance staff at least once a month, to assure that the motors do not stay off for too long (if air-quality and emergency are not triggered, motors stay off), giving them moisture and bearing issues. Thus, it was sufficient to energize only one motor at a time during the scheduled maintenance operations, instead of energizing many motors at a time. In this way, the measurement of the motors signals was possible (even without maintenance staff the operation can be carried out remotely).

Only one issue remained to be solved: when the motors are energized more than one at time for emergency of smog elimination, the current sensors (that remain fixed on the motors upstream feeding line) could undergo core-saturation issues. For this important reason, Rogowski coils are chosen as sensors for this specific application. In fact, Rogowski probes, differently from Hall sensors or current transformers, do not have an iron-core but they are air-cored sensors, i.e., immune to saturation issues.

A general scheme of installation is in

Figure 3.

Details of the installation of the hardware are instead depicted in

Figure 4. Note that, for permanent installation, additional fuses are added in series to the voltage channel, for protection from eventual short circuits due to voltage surges.

Note that with this kind of insertion, the scalability of the monitoring system is much more achievable (because of the reduced costs, the measurement equipment can be installed in many other tunnels). If critical tunnels or motors are identified, dedicated measurement equipment can be reserved for monitoring such components—achieving in this case an actual real-time monitoring. So, scaling the system could be carried out in a hybrid way: using the periodic measurements for normal assets and real-time measurements for the critical ones.

As regards the installed Rogowski coils, four ranges can be chosen (RMS current): 3, 30, 300, 3000 A. Though each motor absorbs about 27 A, and so the 30 A scale could be the most appropriate, in the end the 300 A scale was chosen. This is to include the start-up current that can be used for time-frequency domain analysis. The accuracy of the sensors is quite high, as declared to be <1.5%. Their model is “DeweSoft DS-FLEX-3000-35 AC”, from Dewesoft d.o.o. company, Trbovlje, Slovenia [

32]. Though a real analysis of the SNR in measuring the harmonics magnitudes with this equipment is not carried out, the value of the probes’ accuracy is considered enough because in previous works the authors successfully measured even the very low bearing fault harmonics with probes with the same accuracy and a 16-bit DAQ [

33]. An accounted issue in Rogowski coils is that their accuracy can slightly change with their relative location with respect to the cable on which the current is measured. However, since the installation is fixed—at least in a test campaign—this should not represent a very detrimental condition. Also, the reduction in the SNR, given using the 300 A scale, is considered not critical for the detection of the faults considered in this paper.

5. Algorithms and Elaborations

From tunnel A motors S1 and N6 are analyzed, while from tunnel B motors N7, N10 and N13 are analyzed. Having three currents signals for each three-phase motor, allows for the monitoring of the motors’ health through the analysis of the motor current; this can be achieved by using the classical MCSA, i.e., the study of one phase current of the motor in the frequency domain [

34].

Using current sensors, often already present in the system, MCSA provides a reliable means of machine condition monitoring and is considered as the best choice for rotor fault detection [

4,

34,

35], while also addressing other fault types effectively [

36]. Bearing faults and the Inter-Turn Short Circuits (ITSCs) are among the most challenging faults to detect using MCSA. Bearing faults generate very low amplitude of fault-related harmonics in the current spectra, which are often buried by the noise floor [

37], making reliable detection impractical. ITSC faults rapidly evolve from an incipient fault to a totally destructive condition (and harmonics can be very small also in this case if the fault comprises only few winding turns) [

38,

39,

40]. For grid-supplied machines such as those from our study, there is no practical way to mitigate an ITSC fault, and the only viable solution once it occurs is complete motor replacement. Consequently, in this work the ITSC fault is not considered, and the bearing fault harmonics are not analyzed in the spectra.

Certain bearing faults, especially the generalized roughness faults [

41], produce also eccentricity, whose characteristics harmonics are considered in this work. Since high radial forces associated with eccentricity can increase the bearing wear, monitoring its harmonics provides an effective means to prevent bearing failures. By monitoring eccentricity-related harmonics, without the need for advanced techniques, bearings are indirectly monitored too. Thus, the fault characteristic harmonics considered in this work are related to the detection of the following:

Broken rotor bars.

Eccentricity.

The equations considered are described in the following subsections. Moreover, the diagnoses of the analysis presented were confirmed in many cases by technical staff which dismounted and verified the health conditions of some of the machines during programmed maintenance.

5.1. Rotor Faults

Broken rotor bars or other electric rotor asymmetries (i.e., broken rotor end-ring, porosity in the aluminum cast and magnetic anisotropy) can be detected by using MCSA. A widely recognized formula for identifying characteristic harmonics associated with rotor asymmetries is as follows [

42]:

where

is the supply frequency of the motor,

s is the motor slip and

k = 1, 2, 3 …

However, the sensitivity of this formula decreases in some cases such as with low-load or low-slip machines. Moreover, the equation is prone to false positives in cases of magnetic anisotropy in the rotor core [

40]. Finally, though the more sensitive harmonics in (2) are the ones with

k = 1, it can be necessary to monitor also the harmonics with

k = 2 to avoid false negatives when non-adjacent rotor bars are present and spaced at 90° electric [

43].

Therefore, to have a more reliable approach, the space harmonics-induced rotor fault components can be monitored through the following [

42]:

where m = 5, 7, 11, 13 … (note that the multiples of 3 are not present).

The harmonics from (2) are resumed in

Table 2, separating the “+” and “−” in the formula and considering also the

m = 1, as many references do, for clarity.

Note that with m = 1, the “−” harmonic corresponds to the left sideband of Formula (1), while the “+” harmonic corresponds to the supply frequency (generally not monitored to detect broken rotor bars).

In this work, in any case, the harmonics with m = 5 and m = 7 are considered with Formula (2), since it has been noticed to be more sensitive in these types of induction motors.

5.2. Eccentricity

The characteristic harmonics for airgap eccentricity detection are taken from the following [

32]:

where:

k = 1, 2, 3 … is an integer,

n = 1, 2, 3 … is the harmonic order,

is the rotational rotor speed in Hz, and

p are the pole pairs of the machine.

Note that the characteristic frequencies with harmonic orders different from 1 are often not considered, and negative frequencies are considered in absolute values, leading to the following equation [

42]:

with

k = 1, 2, 3 …

The harmonics in Formula (4) with k = 1 correspond to the LMEH (Lower Mixed Eccentricity Harmonic), when the negative sign “−” is used and to the UMEH (Upper Mixed Eccentricity Harmonic), when the positive sign “+” is applied. The UMEH has been found to be particularly sensitive and is monitored in this work. These harmonics are representative of mixed eccentricity [

44].

Other harmonics considered in this work are for static or dynamic eccentricity detection, given by the following formula [

42]:

where

= 1, 2, 3,…,

number of rotor slots,

order of eccentricity: 0 for static eccentricity, 1, 2, 3 … for dynamic eccentricity

slip,

number of pole pairs,

= 1, 3, 5 … is the order of the stator time harmonics that are present in the power supply waveforms.

Principal Slot Harmonics (PSHs) are generated under specific conditions, particularly when the ratio between the number of rotor bars and the number of pole pairs results in an even number. Under these circumstances, the characteristic harmonics described by Formula (5) become prominent and thus sensitive to fault detection. Characteristics harmonics from (5), however, are mainly present (and then sensitive to the fault) only in particular cases, i.e., when the motor produces the Principal Slot Harmonics (PSHs), that happen when the number of rotor bars divided by the number of pole pairs gives an even number [

45]. In this work some considerations and observations are carried out about these harmonics. In fact, the exact number of rotor bars is uncertain, making it difficult to evaluate the reliability of monitoring based on this parameter in the present case. However, using a comparative analysis through different machines, it can be hypothesized which machines have a higher level of eccentricity.

5.3. Processing of the Data

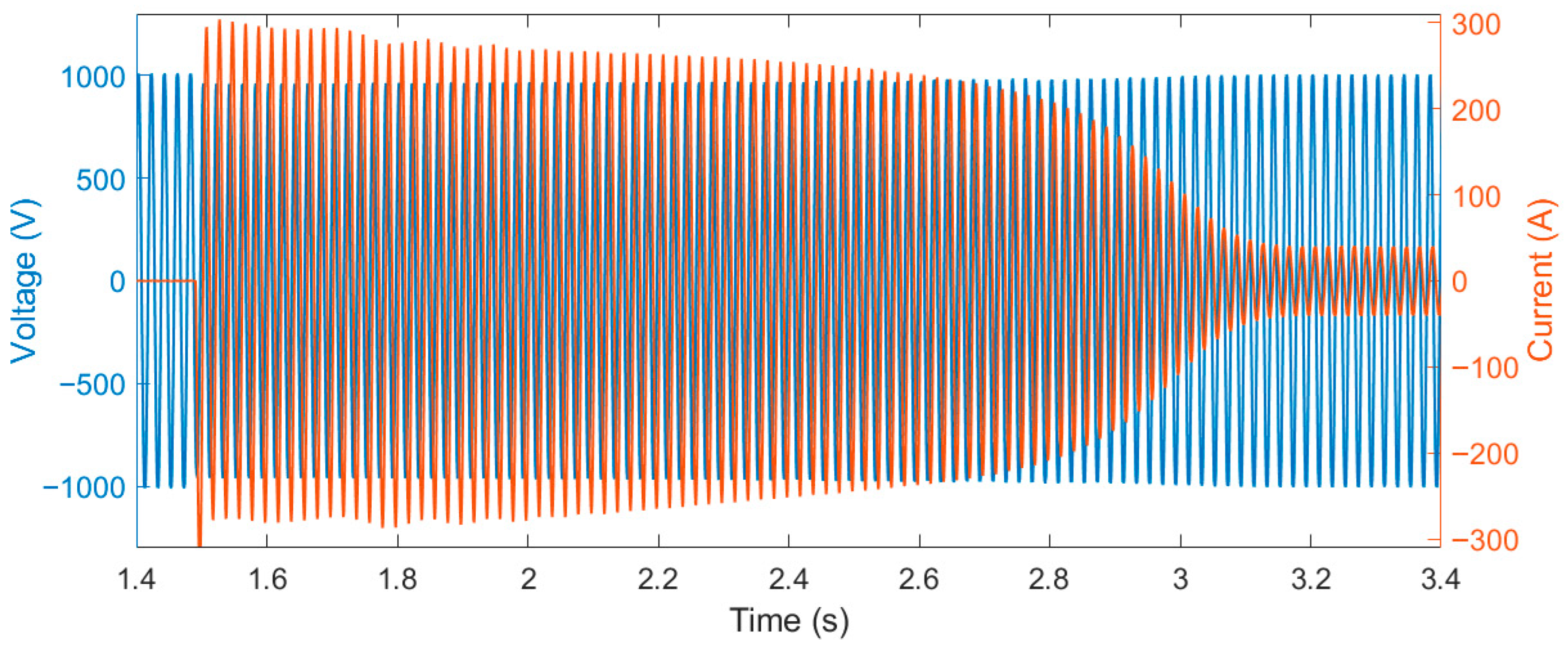

Each acquisition lasts 52.4 s and includes the motor start-up transient (see

Figure 5).

Motor operation in both forward and reverse directions was recorded and analyzed. One acquisition per direction was useful because one direction could show greater operational stability. The parameters of the registration for the two tunnels are summarized in

Table 3. Frequency analysis of voltage is not reported in this work.

The data were processed using MATLAB R2023a. The main steps of the elaborations were as follows:

Since start-up transient is acquired in each 52.4 s long acquisition, selection of the steady state time segment in the signal is applied to remove the transient;

Application of a Hann window function to the time-domain steady-state signal, to reduce spectral leakage;

Frequency domain transformation of the signal through the FFT (Fast Fourier Transform) algorithm. This function generates a double side spectrum, i.e., a spectrum with positive and negative frequencies composite of complex numbers;

Transformation of the complex numbers into absolute values and of the double-side spectrum into a single-side one;

Squaring of the absolute values and transformation into dB;

Plotting of the frequency domain data.

The sampling time was chosen to be a correct trade-off between adequate frequency resolution in spectra and immunity from non-stationary conditions. The frequency resolution in the spectrum is obtained reversing the sampling time. Eliminating the transient of the motor, the sampling time can be considered to be 50 s; it leads to a frequency resolution of 1/50 = 0.02 Hz, that has been found to be adequate for discerning close harmonics. Note that lower sampling time led to an inadequate frequency resolution, while augmenting this time increases the probability of acquiring non-stationary conditions. So, the selected sampling time can be considered an ideal trade-off to optimize these two constricting factors.

The data analyses, in the frequency domain, are in the following sections for the two tunnels considered. In tunnel A it is known that the motor S1 was installed nine years before the analysis and so it is considered near the end of its service life (the current maintenance program aims to replace the motor every ten years). As regards motor N6, it was installed less than one year before the data acquisition campaign. The acquisitions in this tunnel were carried out from January to June of 2024, with measurements taken every two to three weeks during this period. Two datasets will be considered and compared in this work: one acquisition from January and one from May.

Regarding tunnel B, the motors were installed eight years before the analysis, and measurements were taken once in August 2024. Based on overall vibration readings and maintenance staff inspections, it was known that machines N10 and N13 had some bearing issues and were scheduled for replacement during the next maintenance stop. The motors’ health conditions are resumed in

Table 4 (the results and considerations will be presented in the next sections).

Note that in the analysis, no specific threshold is used to determine if the machine being examined is in faulty condition. Instead, a comparative approach between signatures coming from different machines is carried out, or alternatively, the signature from the same motor can be compared to itself during different acquisitions in a time plan. However, after enough measurements, with both healthy and faulty cases recorded, a statistical approach could be used to better hypothesize fault thresholds.

During the campaign, it can be stated that no false negatives were detected since no motor exhibited actual failure. Moreover, excluding the diecast porosity that is difficult to verify, no false positives were detected (since motor N10 and N13 health was verified by maintenance staff).

6. Tunnel A Analysis

6.1. Broken Rotor Bars Related Harmonics

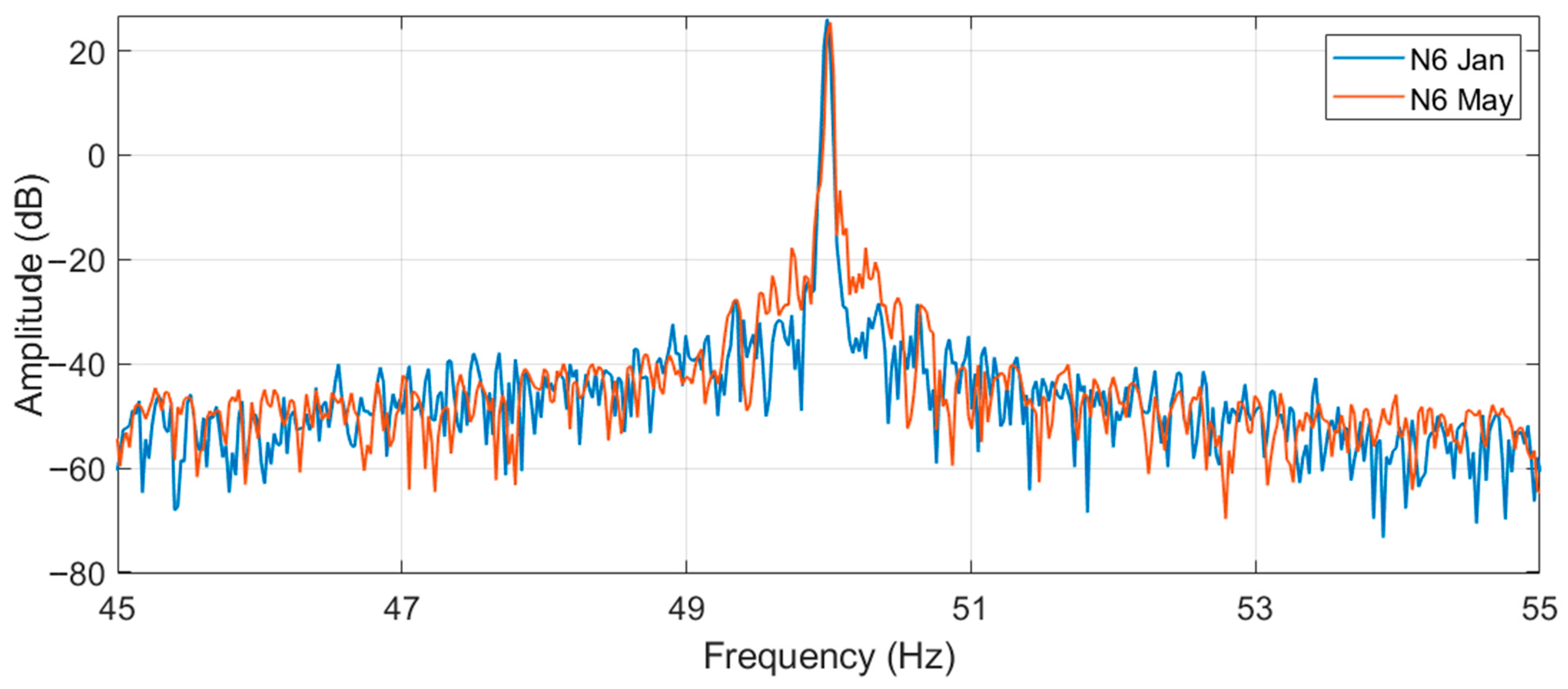

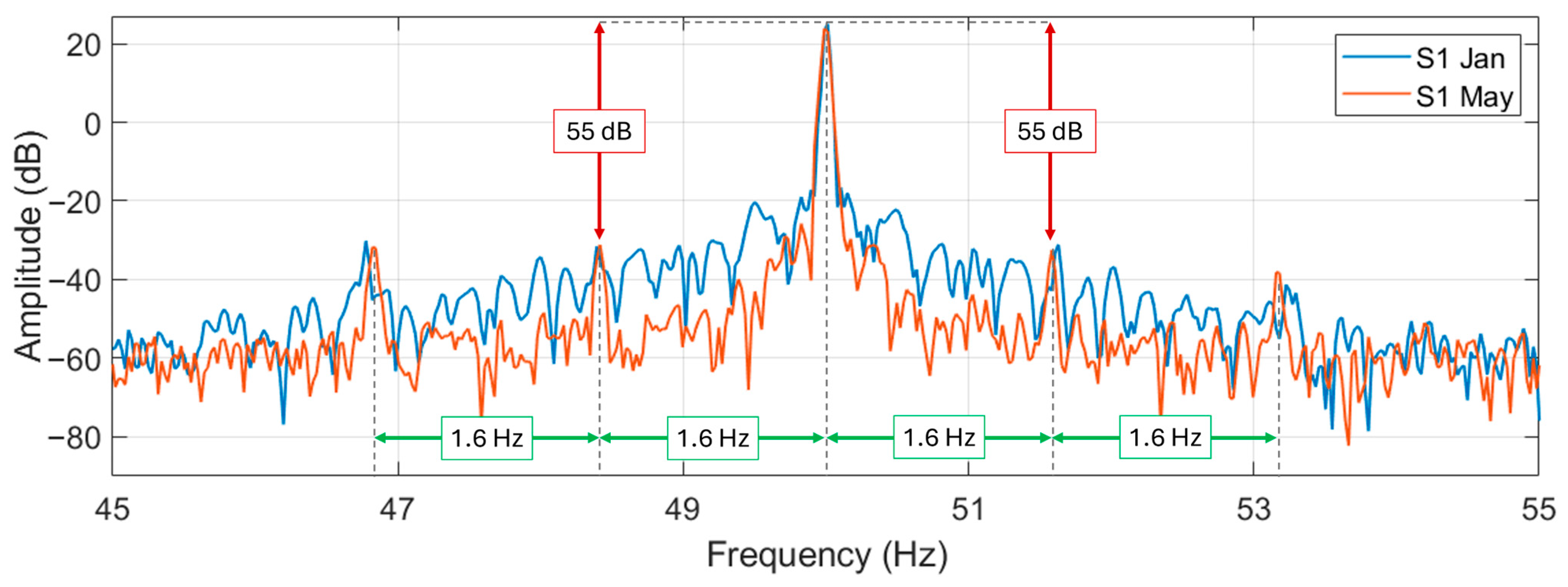

Firstly, the sidebands around the supply harmonic (at 50 Hz) are checked out. This is because their values are representative of the slip of the machine and of rotor asymmetries. Current signals for January and May recordings are represented in the next figures for motor N6 (healthy) and S1.

Current signal spectra zoom around the supply frequency are represented in

Figure 6 and

Figure 7 for the two motors.

A difference can be noticed between the two motors in this frequency range: in motor N6 it is practically not possible to see any sidebands (from Formula (1)) around the supply harmonic. In motor S1, instead, the sidebands are noticeable at about 1.6 Hz (especially for the signal acquired in May). In motor S1, the magnitude difference between the fundamental and the sidebands is about 55 dB. The difference in energy between these sidebands and the fundamental, that does not change in the period between January and May, implies the absence of the broken bar fault. However, since those harmonics are clearly visible, it can be hypothesized that an amount of porosity in the aluminum cast (or other kind of inherent rotor circuit or magnetic asymmetries) is present in S1 to generate the sidebands. The porosity in the aluminum diecast is a manufacturing defect that in the authors’ opinion will not deteriorate significantly over time (unless it is very severe). So, the motor can continue working. However, higher rotor losses (due to a higher rotor electrical resistance) and a torque oscillation in the motor output (due to a non-uniform distribution of the electrical resistance in the rotor bars) can be expected. These side-effects can potentially increase the motor temperature (accelerating the deterioration of winding insulation) and induce bearing wear due to the speed oscillation deriving from the torque oscillation. So, though it is difficult to effectively verify the porosity, it is worth giving attention to bearings and insulation health during the maintenance inspections.

Moreover, in the authors’ opinion, the two motors can be of different models (knowing also that N6 motor had been recently substituted) and the related signatures could be different. For example, a different skewing angle could be adopted in rotor designs or different combinations of stator and rotor slot numbers could be utilized in the two motors. As regards the magnetic anisotropy of the rotor, since the machines are low power, the authors believe that the manufacturer did not use a skewing technique in the stacking of the rotor laminations to reduce the anisotropy. So, anisotropy should be present in every motor and if the harmonics appear it should be due to porosity or possibly rotor ovality [

46].

Regarding the discrepancies observed among the measures taken at the four-month intervals, the underlying reason for the less evidence of side-band features in the January measurement of motor S1 remains unclear. Hypotheses can be drawn on a less stationary working condition, e.g., due to the presence of wind in the gallery. It can be noticed also that there is a slightly higher slip in the January trial; this ideally can be due to the lower season temperature that increases the air density and then the load to the ventilators.

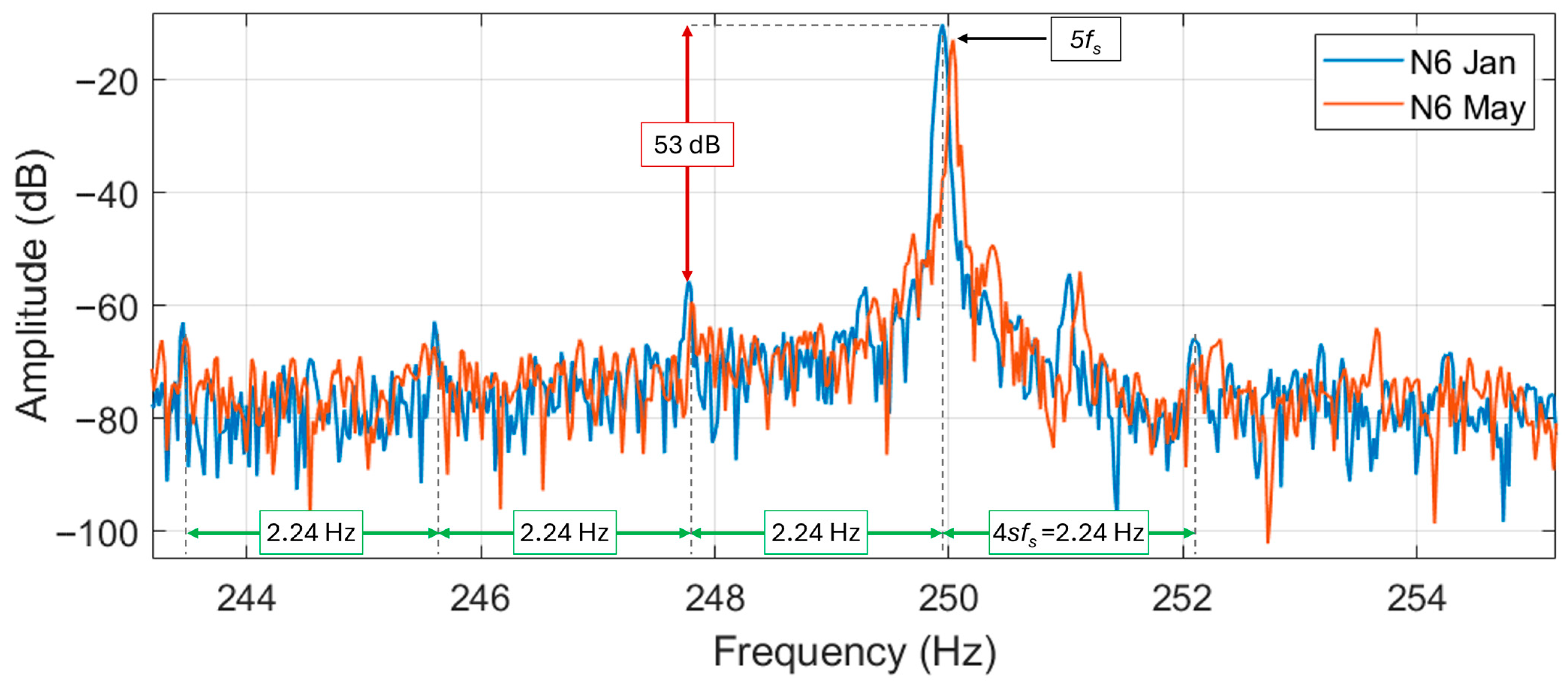

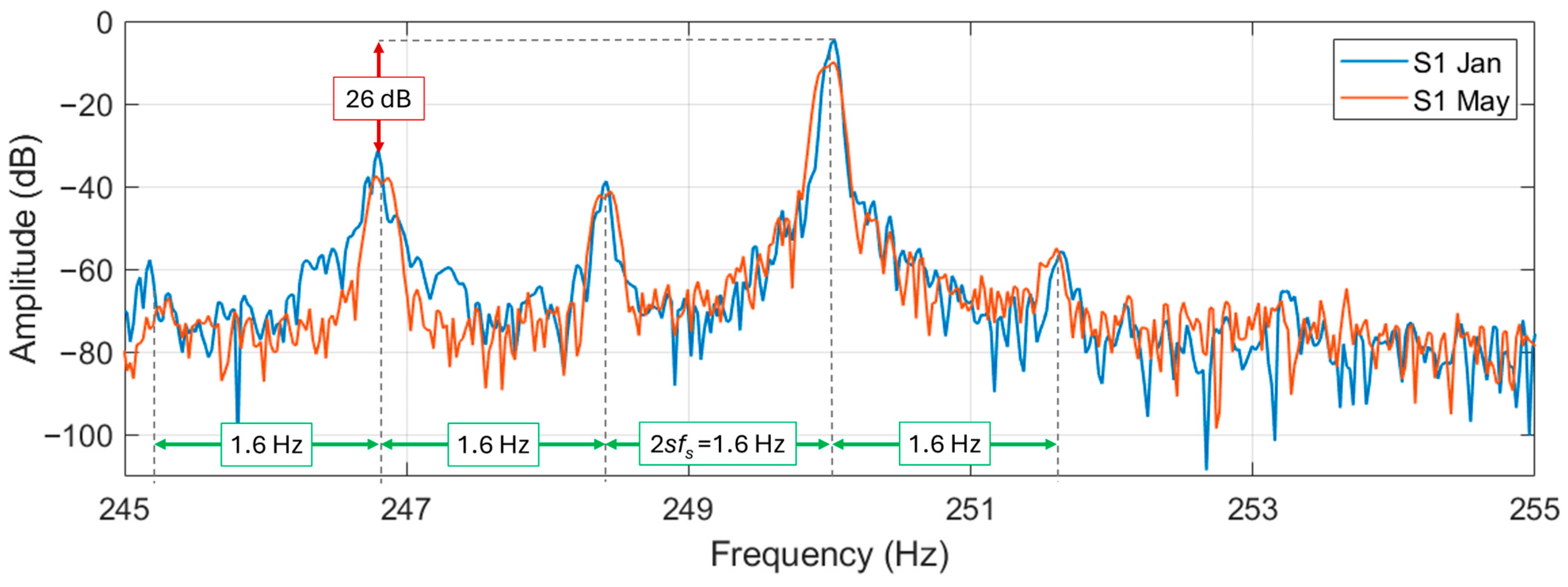

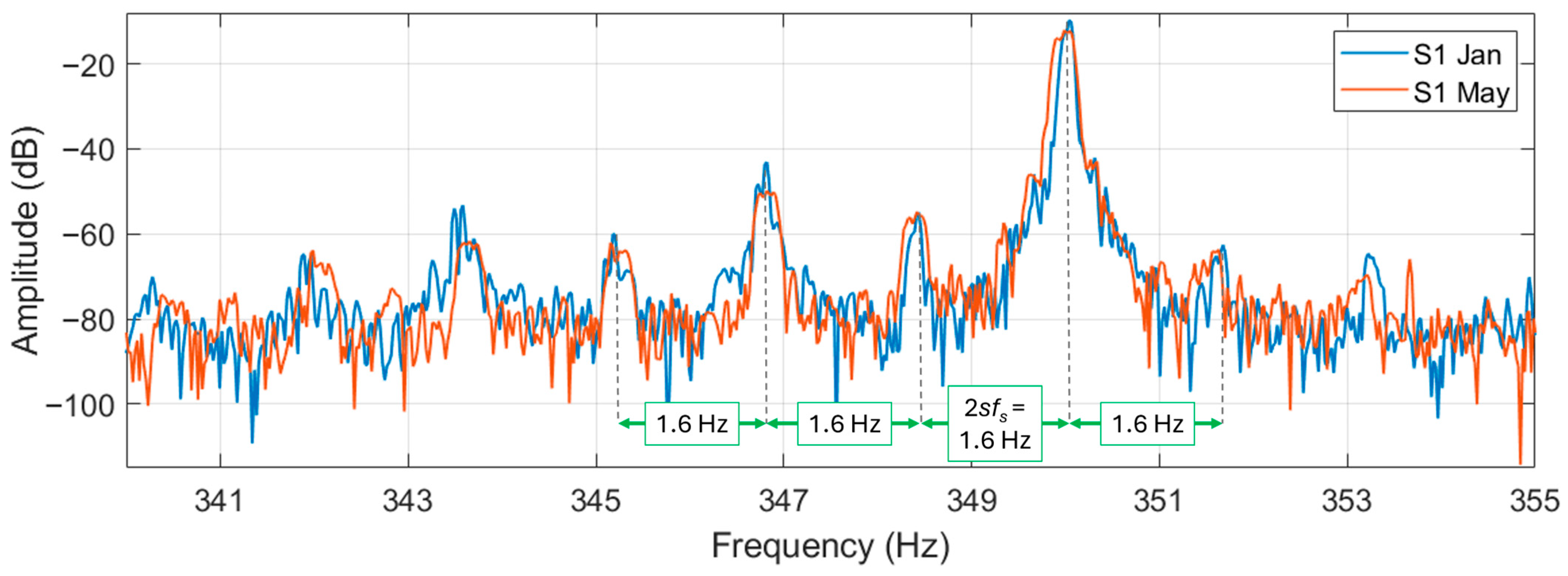

The characteristic harmonics from (2), namely

, near the fifth supply harmonics are shown in

Figure 8 and

Figure 9. For motor N6 (healthy) the harmonics are slightly noticeable. In a first instance, the distance between the harmonics could be assumed to be

, measurable as 2.24 Hz, and, since

reversing the Formula (2) corresponds to an estimated slip of 2.24%. However, as will be shown in the following analysis, the visible sidebands are displaced at

from the fundamental. Therefore, 2.24% is twice the value of the slip (the actual slip is around 1.12%).

Motor S1 has also much more noticeable harmonics in this range of frequencies. The displacement between each harmonic is about 1.6 Hz, meaning that if they are at distances, the estimated slip resulting from (1) is 1.6%. The difference in magnitude between the fifth harmonics and the higher of the is around 53 dB for the N6 and 26 dB for the S1. Moreover, in this case no particular fault is hypothesized though an inherent asymmetry in motor S1 is supposed to be present; different types of motor design also can have influenced the appearance of such different signatures.

Finally, marked degradation over the months is not noticeable in the spectrum.

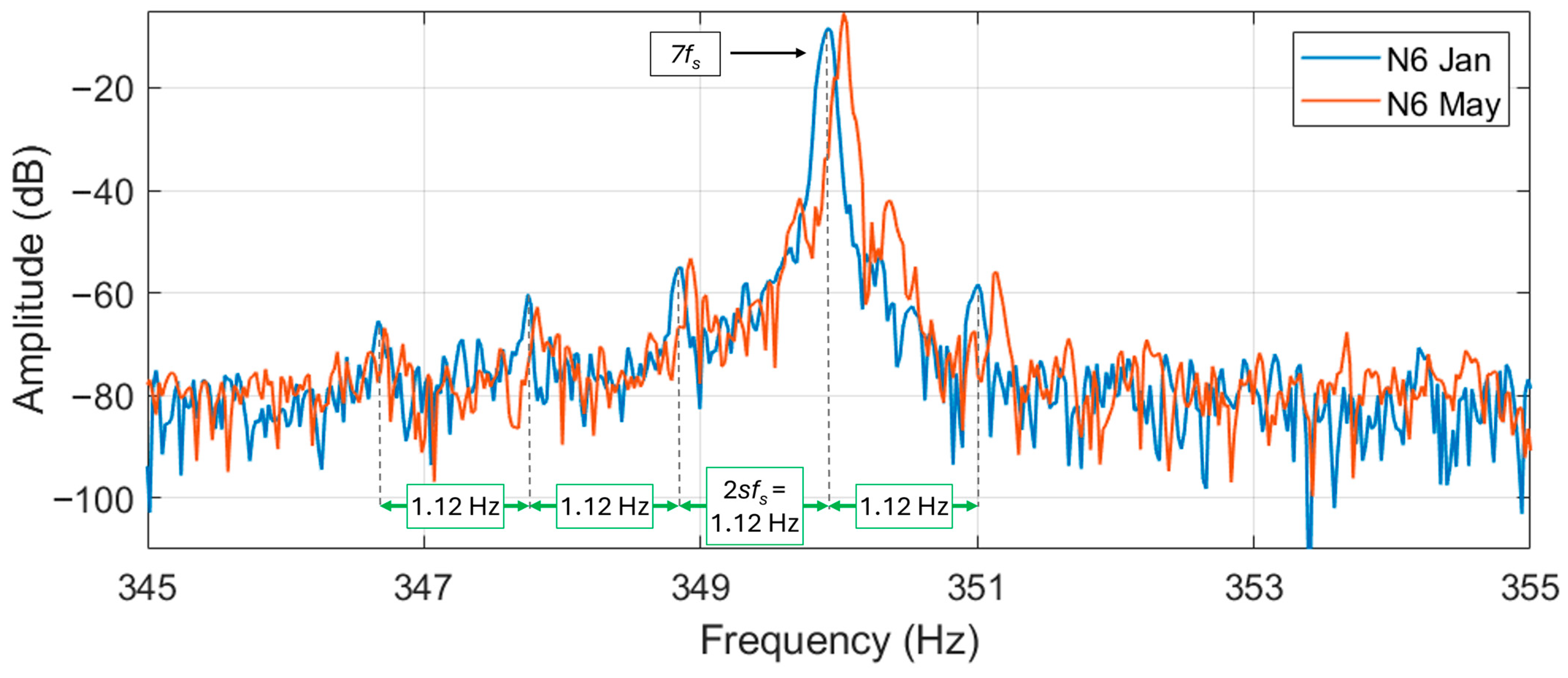

To double check the N6

harmonics, the seventh supply harmonics are analyzed. Here the harmonics are clearer and spaced at a different distance, i.e., about 1.12 Hz. This is assumed to be the correct value of the

distance, representing a slip of 1.12% for N6. The slip, in fact, is then verified using the eccentricity harmonics from Equation (4). The

harmonics near the seventh supply are represented in

Figure 10 and

Figure 11 for motor N6 and S1, respectively.

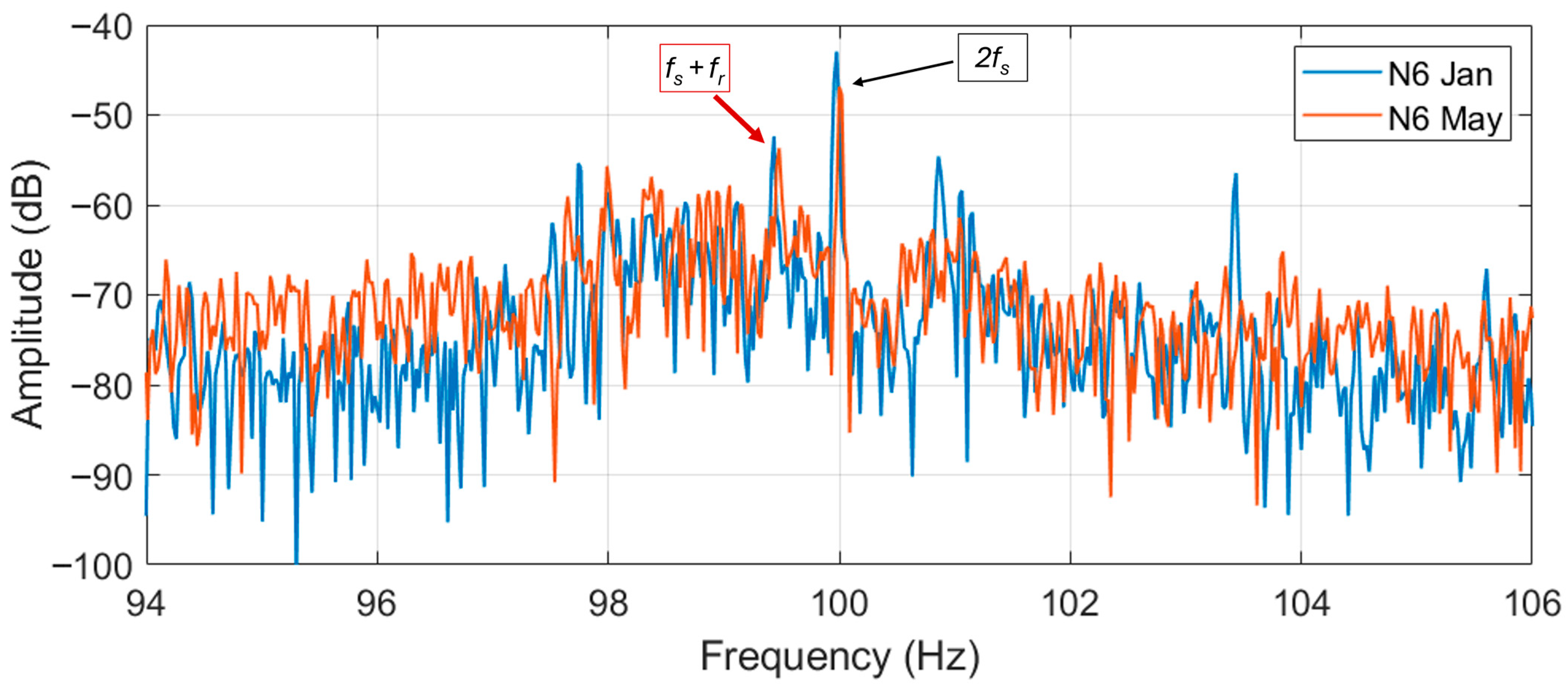

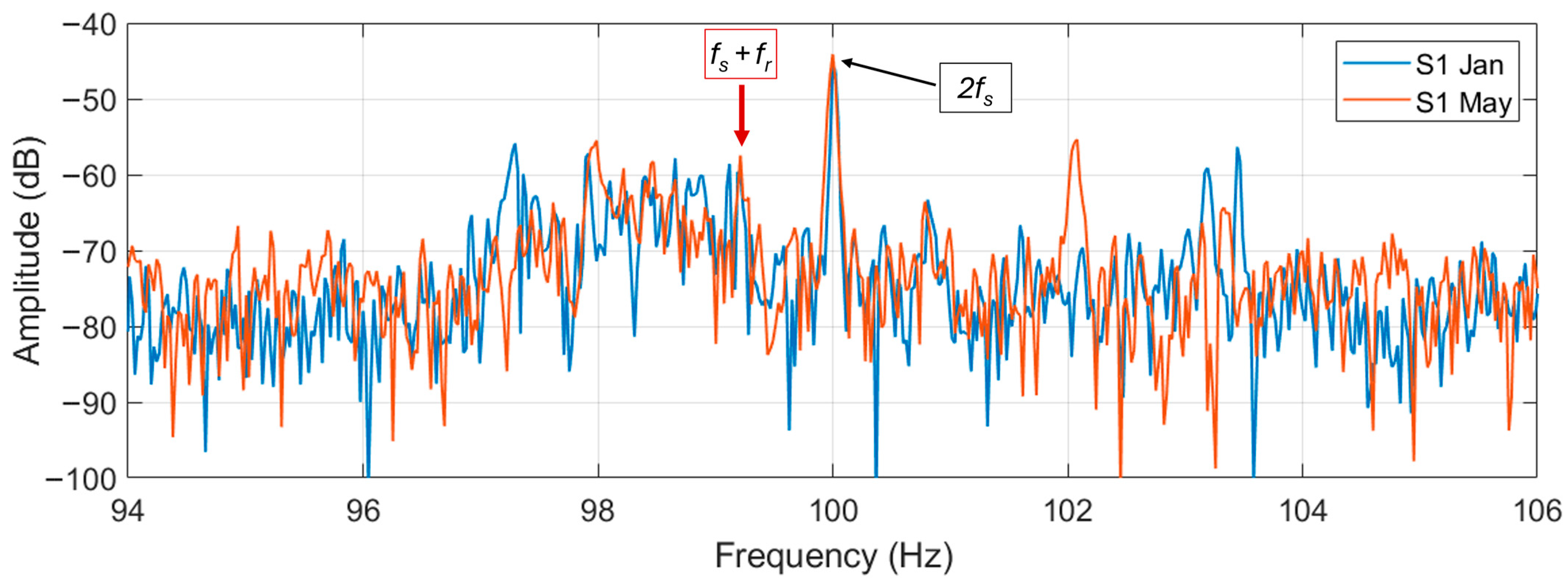

6.2. Eccentricity-Related Harmonics

The analyses of eccentricity-related harmonics for motors N6 and S1 are reported in

Figure 12 and

Figure 13. These harmonics are the UMEH, obtained from (4) when

k = 1 and the positive sign are applied. Note that the harmonics are quite close to

at 100 Hz. This is typical for 2-pole (

) machines; therefore, finding the characteristic harmonics represents a challenge, since they can have similar amplitude to other harmonics around the 100 Hz component. For machines with

, instead, this harmonic is generally easier to find, since in those cases it does not lie around high-energy components.

In addition to what has been discussed so far, the harmonics presented in this subsection can be used to estimate the slip (and therefore the speed) of the machine [

47]. In fact, from the estimation of the slip given by Equation (2), that can be considered quite approximate [

47], and knowing the pole number of the machine, it is possible to identify the zone of the spectrum in which to look for the UMEH. Then, after finding the exact frequency of the UMEH, slip and speed can be calculated by reversing Equation (4).

Assuming that the harmonics are the ones highlighted with red arrows in

Figure 12 and

Figure 13, it turns out that the slip is 1.12% for motor N6 and 1.6% for motor S1. This finding confirms the slip estimation conducted by studying the broken rotor bar harmonics in

Section 5.1.

As regards the magnitudes of these harmonics, to the knowledge of the authors, no fixed threshold limit is defined in the literature that indicates severe faults. However, in this work, the harmonic magnitude is monitored in time and compared to . The eccentricity harmonics are found to be lower than the 100 Hz harmonic of about 10 dB and 13 dB for motor N6 and S1, respectively. In authors’ opinion this should not represent a critical level of eccentricity.

6.3. Slot Pass Harmonics and Eccentricity Sidebands

The slot pass harmonics (SPH) appear due to the presence of slots in the rotor and, as already mentioned, can be pronounced depending on the combination of the numbers of bars and poles [

45]. They can be easily recognized in the spectra as they are the higher harmonics in the high-frequency range (generally over 800–1000 Hz). Moreover, they are distanced

one with the others (in case of 50 Hz supply they are distanced by 100 Hz).

The eccentricity-related sidebands of these harmonics can be found using Equation (6). Specifically,

sidebands around the SPHs should appear pronounced in case of eccentricity [

44].

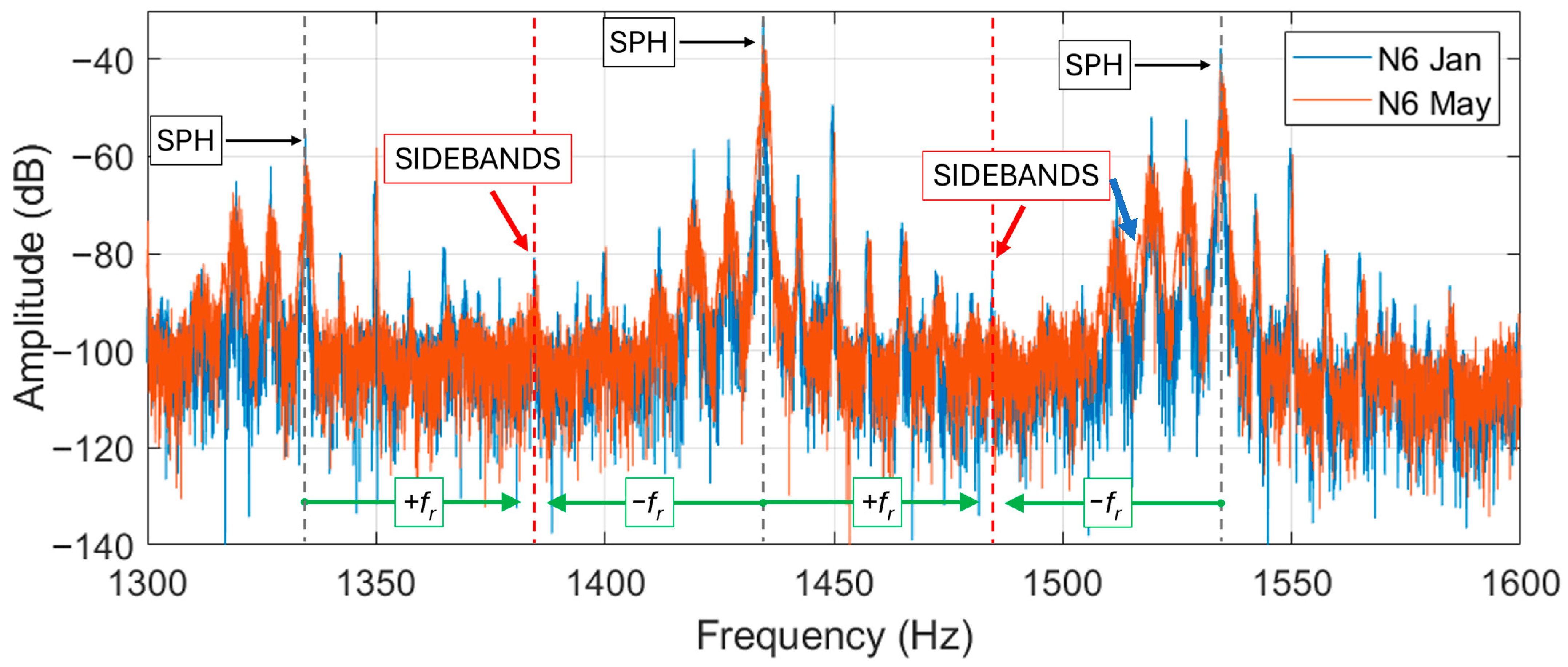

In motor N6 the SPHs with higher energy are placed at about 1434 and 1534 Hz. In this case, the measured amplitude is particularly high for the measurement carried out in January. The research of the

sidebands is not easy (since the spectra are noisy in the analyzed region) and the left sideband of the generic (

n + 1)-th SPH tends to overlap the right sideband of the (

n)-th SPH. This situation is represented in a wide frequency region in

Figure 14 for motor N6. Despite the fact that a quite prominent harmonic can be seen between two consecutive SPHs, it is not possible to distinguish the left from the right sidebands. This introduces difficulties in diagnosing this fault using these sidebands in 2-pole motors.

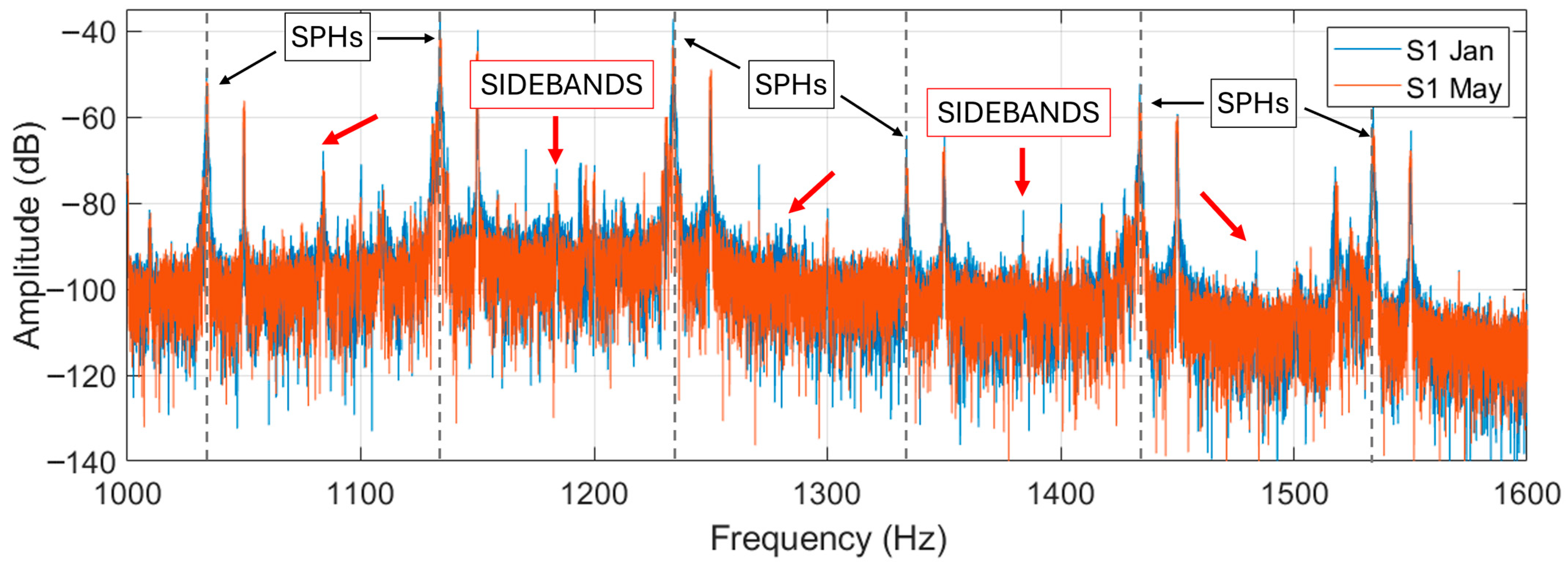

Regarding motor S1, similar results are found. In this case the highest SPH is at 1134 Hz approximately instead of the one at 1434 Hz found in the motor N6. This is probably due to a different number of rotor bars but can also be hypothesized as a filtering effect on the acquisitions, e.g., due to different cable lengths in the two motors. The spectra of motor S1 are depicted in

Figure 15; marked with the black labels and arrows are the SPHs, while red arrows indicate the locations where the sidebands of the SPHs should appear separated but generally appear as a merged peak.

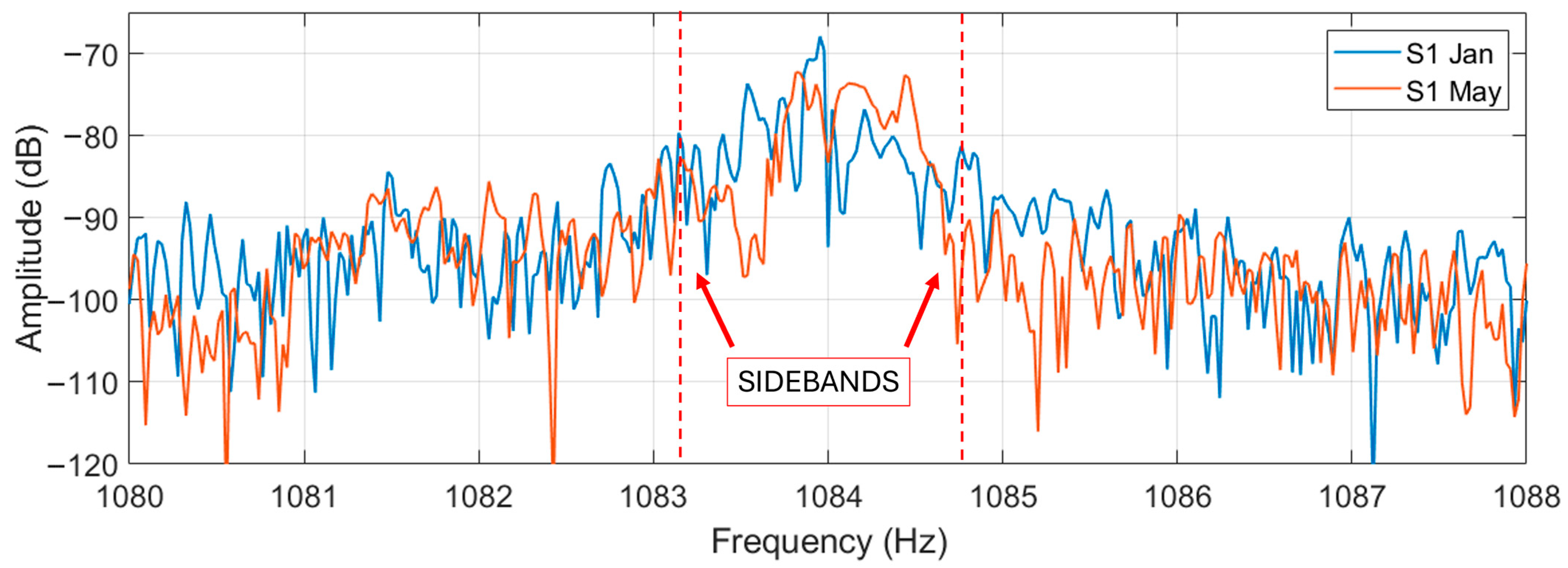

The highest sidebands harmonics have been found between the SPHs at 1034 and 1134 Hz. Zooming these sidebands (

Figure 16), a high harmonic is shown at the middle frequency, i.e., about 1084 Hz and slightly visible are the sidebands at 1083.15 and 1084.75 Hz representative of dynamic eccentricity (

fr is about 49.2 Hz). This highlights the difficulty of using these sidebands, though it can also be that the sidebands are of low levels because the motors do not have eccentricity.

7. Tunnel B Analysis

Data from three motors of this tunnel are studied and reported in this section: motor N7, known to be healthy, and motors N10 and N13, known to have some bearings issues. Only one acquisition for each motor is analyzed in this section. However, data from both forward and backward motor rotation will be presented, for the sake of completeness. The backward motor rotation in most cases gave more stable signals (with less current fluctuations) and so can be considered more interesting for diagnostic purposes. However, since in some cases the forward signal gave clearer results, both signals will be shown.

7.1. Broken Rotor Bar-Related Harmonics

Very slight or no sidebands are present around the fundamental harmonic. The broken rotor bars harmonics are then searched near the fifth and seventh harmonics.

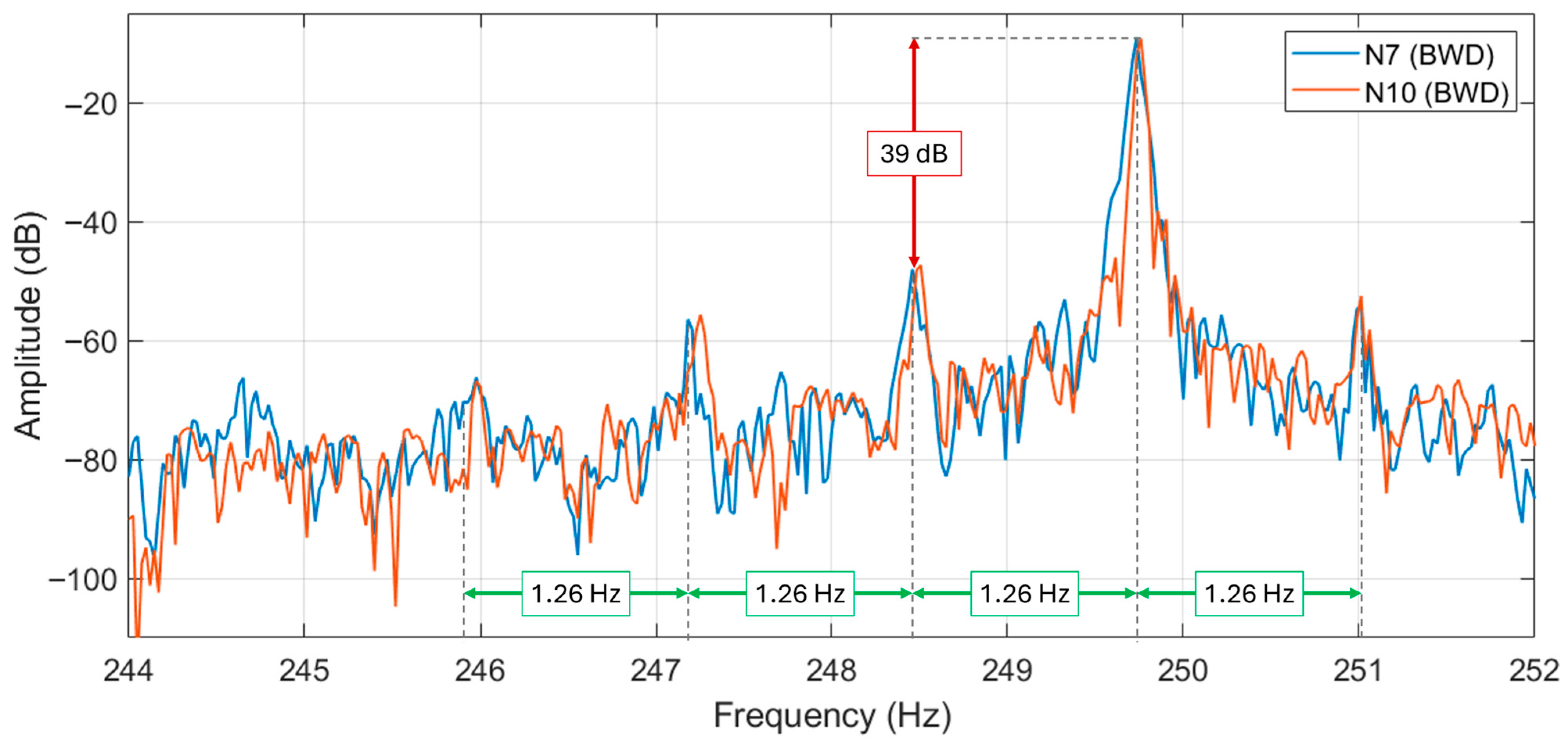

Figure 17 shows the BRB harmonics near

, for motor N7 and N10. From these harmonics, the slip of both machines can be estimated to be around 1.26%. Motor N13 has the same slip. These harmonics are lower than the fifth harmonic of at least −39 dB. Moreover, since very slight harmonics are found around the supply harmonic (50 Hz), it is concluded that no broken rotor bars or excessive porosity in the aluminum diecast (that generate rotor asymmetries) is present.

7.2. Eccentricity-Related Harmonics

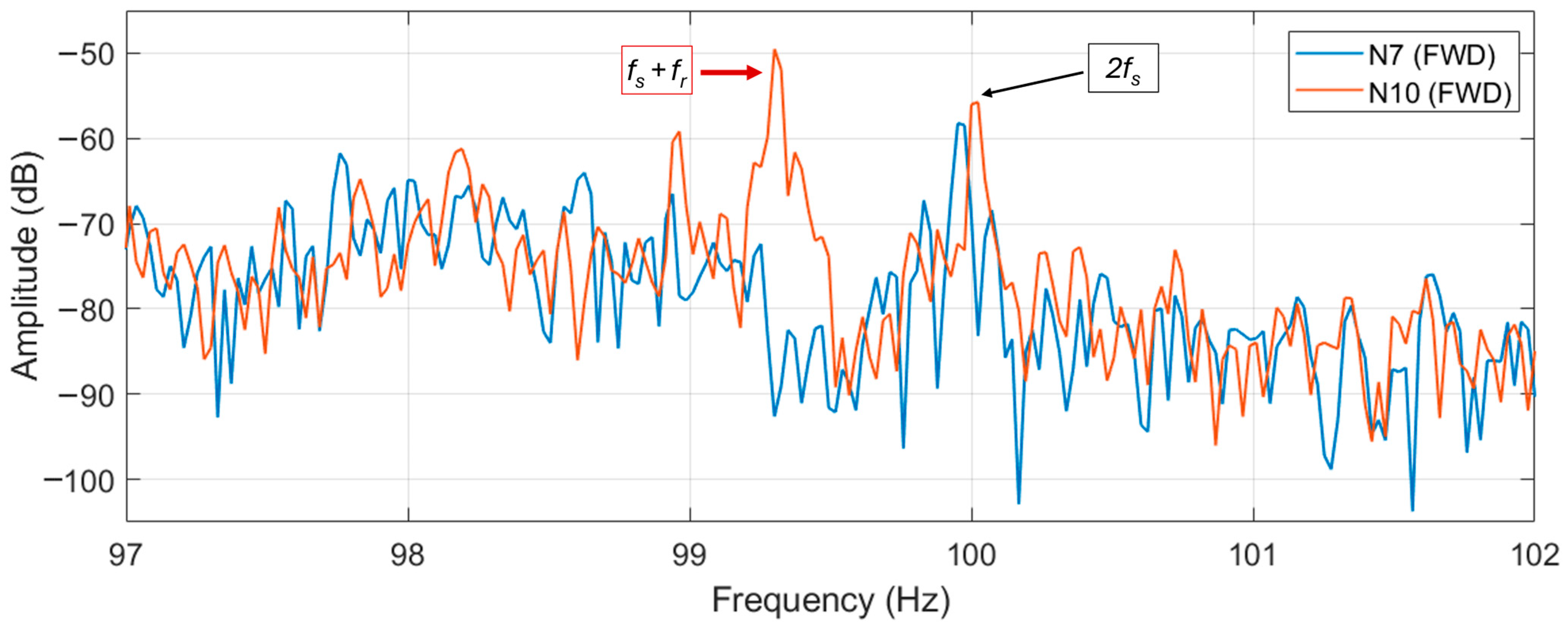

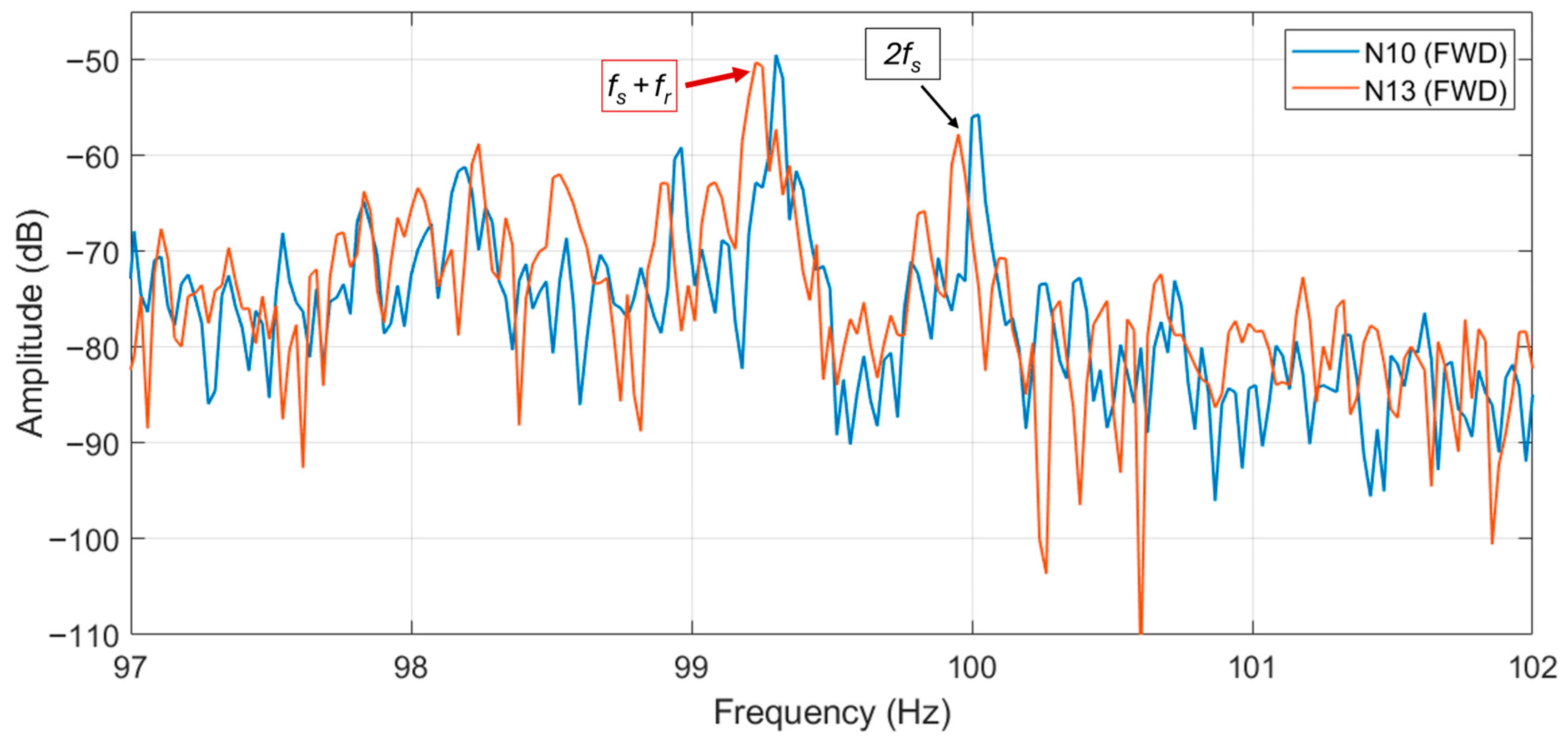

Different amplitudes in eccentricity-related harmonics have been found, depending on the motor. Motor N7 (healthy) generally presents lower eccentricity harmonics than motors N10 and N13. The harmonics found for N7 and N10 are highlighted in

Figure 18. In the figure the second supply harmonic is visible at 100 Hz, whose amplitude is similar for both motors. However, the eccentricity harmonic is much higher in N10 than N7 motor (about 20 dB more), being even higher in amplitude than the 100 Hz harmonic of about 6 dB. In the authors’ opinion this comparative analysis, between two similar motors (if not equal), can highlight eccentricity problems in motor N10.

As regards motor N13, similar or even higher amplitudes of eccentricity-related harmonics than those observed for motor N10 have been found (

Figure 19). Therefore, the presence of eccentricity can be hypothesized for motor N13.

To confirm the eccentricity in motors N10 and N13, a comparison between the third harmonics of the motor under analysis for Tunnel B has been made. The results show that, compared to the harmonic of motor N7, those in the spectra of N10 and N13 have an increase in magnitude of around 5–6 dB (while the harmonics related to the supply frequency have the same levels in all the spectra).

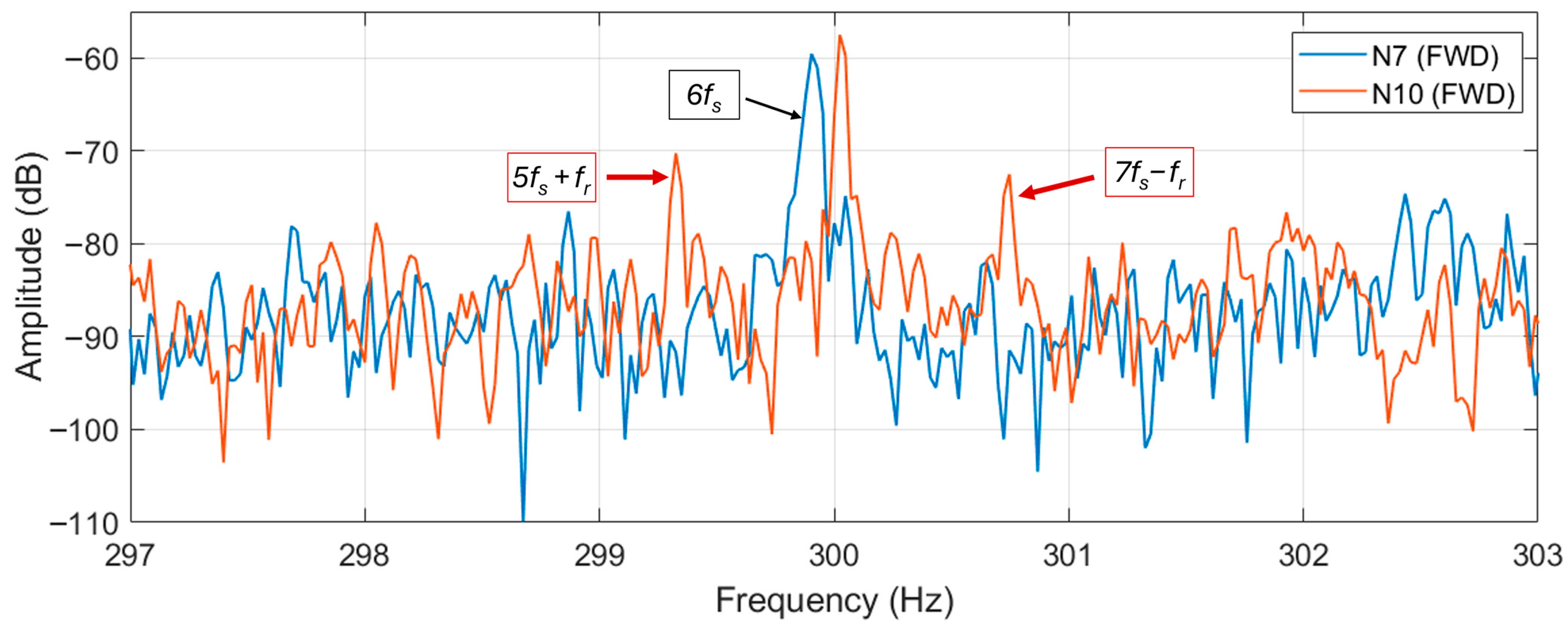

Moreover, it has been found that other sidebands given by Equation (4) are quite sensitive: the right sideband of the fifth harmonic and the left sideband of the seventh harmonic, keeping

k = 1 in the formula. Namely they are the

and

. These sidebands appear around the sixth harmonic of the fundamental (300 Hz). They are represented in

Figure 20, from which the higher levels of the harmonics of the N10 motor are evident (about 8 dB higher). Similar magnitudes were found for motor N13.

The summary of the magnitudes of the eccentricity-related harmonics and of the reference harmonics at

and

is reported in

Table 5. The table clearly shows higher magnitudes in the eccentricity-related harmonics for motors N10 and N13, while the reference harmonics

and

remain almost constant in every case.

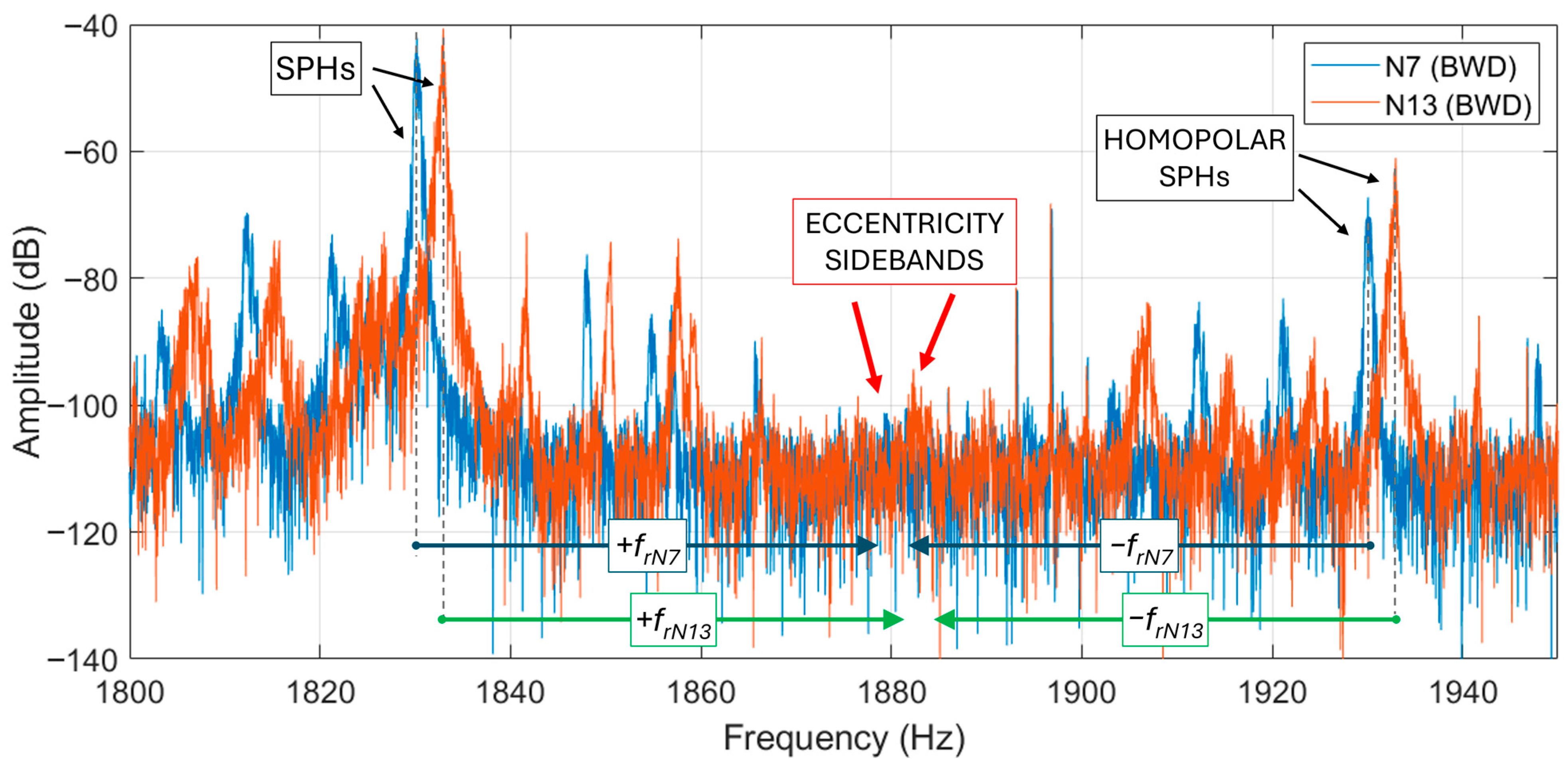

7.3. Slot-Pass Harmonics and Eccentricity Sidebands

A comparative analysis on the slot pass harmonics and their eccentricity sidebands is carried out in this subsection. At higher frequencies, spectra are not clear and the fault-related harmonics found are quite low. Nevertheless, compared to the healthy machine (N7), higher amplitudes can be observed in the faulty ones.

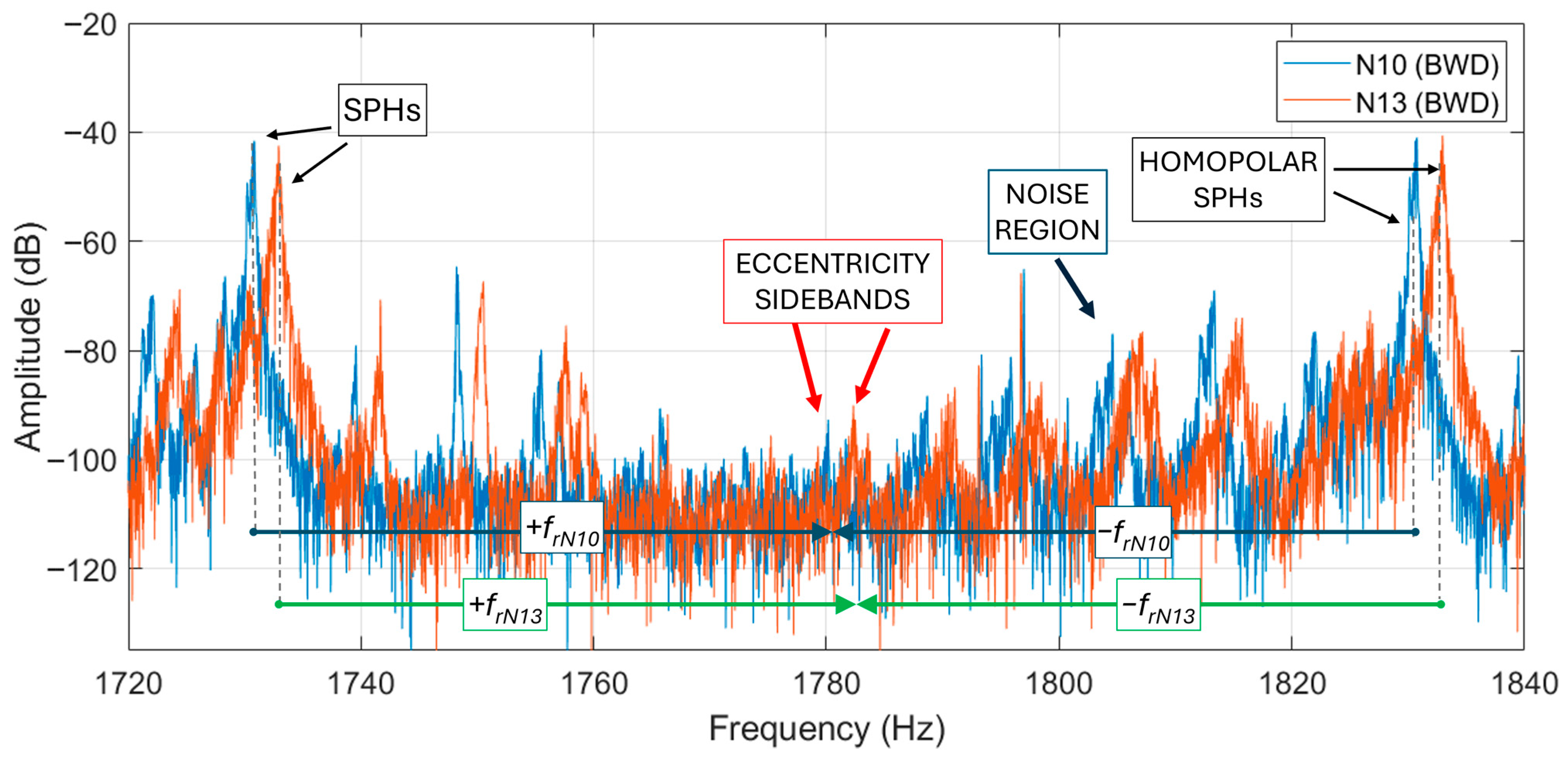

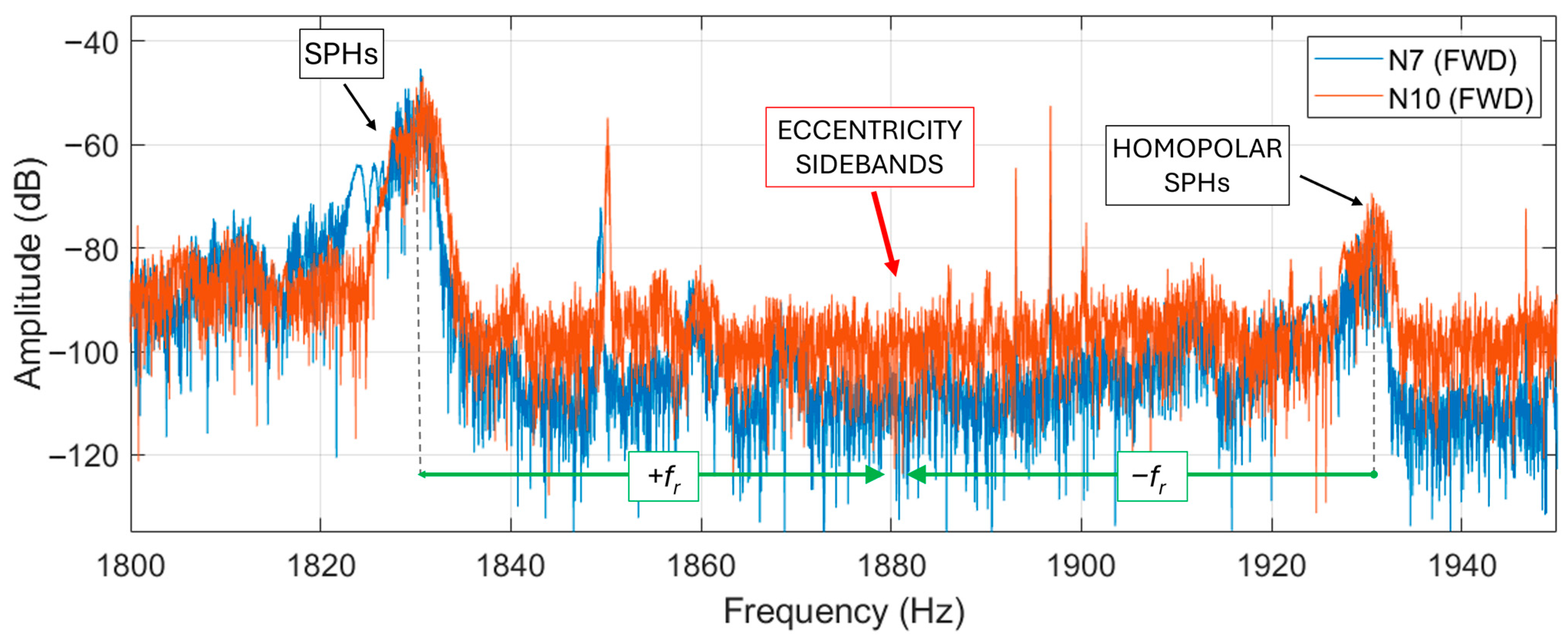

For example, monitoring motor N13 and motor N7 some differences are noticeable. In motor N13, operating in backward rotation, SPHs appear at about the “33” units of each hundred, i.e., 1433, 1533, 1633, etc. Hz. In motor N7 in backward rotation, they appear at the “30” units (this can be due to slightly different slip between the machines).

SPHs are found to be variable in their amplitude, having a series of two high-energy SPHs and then one with lower magnitude. The lower of the SPHs is supposed to be the homopolar one [

48]. In the data collected the homopolar SPH is generally 20 dB lower than the non-homopolar. It has been noticed that the left or right eccentricity sidebands of the SPHs are quite distinguishable in faulty motors; moreover, the eccentricity sidebands of a homopolar SPH are often even more visible since less “noise” is found in the region (the noise can cover the harmonics). Examples are in the following

Figure 21 and

Figure 22.

Note that the eccentricity harmonics should be distinct, but as in the case of the motors of tunnel A, they tend to overlap. If speed variations occur (as observed in motor forward rotation), these harmonics are more difficult to observe. In

Figure 23, eccentricity harmonics for the forward rotation of motors N7 and N10 are presented. Only motor N10 shows harmonics in between the two SPHs, indicating a higher value of eccentricity. A final observation can be made on the widened peaks of the SPHs: this is due to non-stationary conditions (speed variations).

8. Conclusions

In this paper, a field application of condition monitoring and diagnostics of electrical machines is described, starting from consultancy activities carried out by some of the authors for “Autostrade per l’Italia S.p.A.” company, the principal operator of Italian highways. During the study, highway tunnel axial-jet fan motors have been monitored through the acquisition of current. The monitoring process has been implemented by acquiring the signals from outside the tunnel, in the electrical cabin that feeds the tunnel services. This choice allowed for a reduction in the costs and the complexity of the process, compared to the signals acquired inside the tunnels.

Moreover, since the ventilators are typically de-energized (they switch on only in case of emergency, i.e., fire alarm or due to high pollution), and considering the installation’s complexity, deploying a single acquisition system (DAQ + computer + three Rogowski current sensors) to monitor all tunnel motors proved efficient and practical. With this kind of installation, a continuous monitoring operation can be carried out remotely (all the equipment can be activated—and the data transmitted—through internet), for example once or twice a month, and cost effectively. This potentially allows a comparative analysis during time, i.e., the characteristic harmonics of the same motors can be monitored in their magnitude monthly.

Interpretation of the data is operated to understand the healthy conditions of the machines, i.e., diagnostics techniques are implemented. Focus is given to frequency-analysis of the current signal and specifically on broken rotor bars and eccentricity-related harmonics. These faults have been chosen as a benchmark due to their quite slow degradation over time. Therefore, if monitored, the fault can be detected promptly and maintenance actions can be programmed efficiently. Nevertheless, other faults can be considered in future approaches.

The results obtained by data analysis are often confirmed by maintenance staff which had accurate information about the machines’ condition during the periodic scheduled maintenance. Two tunnels are included in the measurement campaign (namely tunnel A and B) and the defects found or suspected are: porosity in the aluminum rotor diecast (or rotor ovality) in one motor of tunnel A and eccentricity issues in two motors in tunnel B. These latter issues are reported by maintenance staff to be due to bearing defects that, as known from the literature, can in turn generate eccentricity issues.

The paper presents also many insights given by real-life acquisitions, as highlighted in the following:

frequencies around supply harmonics can be hard to detect when the slip has low value.

The spaced frequencies around the fifth supply harmonics can be sometimes not visible and instead harmonics can be seen (seen in motor N6 of tunnel A).

There is some difficulty locating sidebands around the Slot Pass Harmonics because they appear as overlapped harmonics rather than separated harmonics.

The proposed rule of thumb to check eccentricity in 2-pole motors is by confronting the Upper Mixed Eccentricity Harmonic with the harmonic (100 Hz).

The presence of the homopolar SPHs near where the eccentricity harmonics are allowed for a clearer observation of the latter because of less noise disturbances.

Among the many fault-related harmonics obtained by the different coefficients in the proposed equations, the and harmonics have been found to be more sensitive than others for eccentricity detection.

The forward and backward directions of the motors can give different signal signatures.

Management of multiple or combined faults is particularly challenging because feature extraction becomes increasingly complex when linear or non-linear combinations of frequency components are present in current signals.

Based on the diagnostic results obtained with MCSA, the next phase involves applying the diagnostic approach to estimate the Remaining Useful Life (RUL) of induction motors across the tunnel network. A promising method integrates MCSA, Id–Iq trajectory analysis and FFT with machine learning techniques, focusing on bearing health [

13]. Additionally, a Health Index (HI) derived from these features would enable classification of fault conditions. The RUL can then be estimated by analyzing the degradation trend of the HI, providing a quantitative basis for maintenance planning.

To conclude, the authors suggest that a comparative analysis between all the selected harmonics (either within the same motor over a defined period or across different motors of the same model) represents an effective approach for machine analysis and fault diagnosis in this application.