Asymmetric Metamaterial Nanowire Structure for Selective Solar Absorption

Abstract

1. Introduction

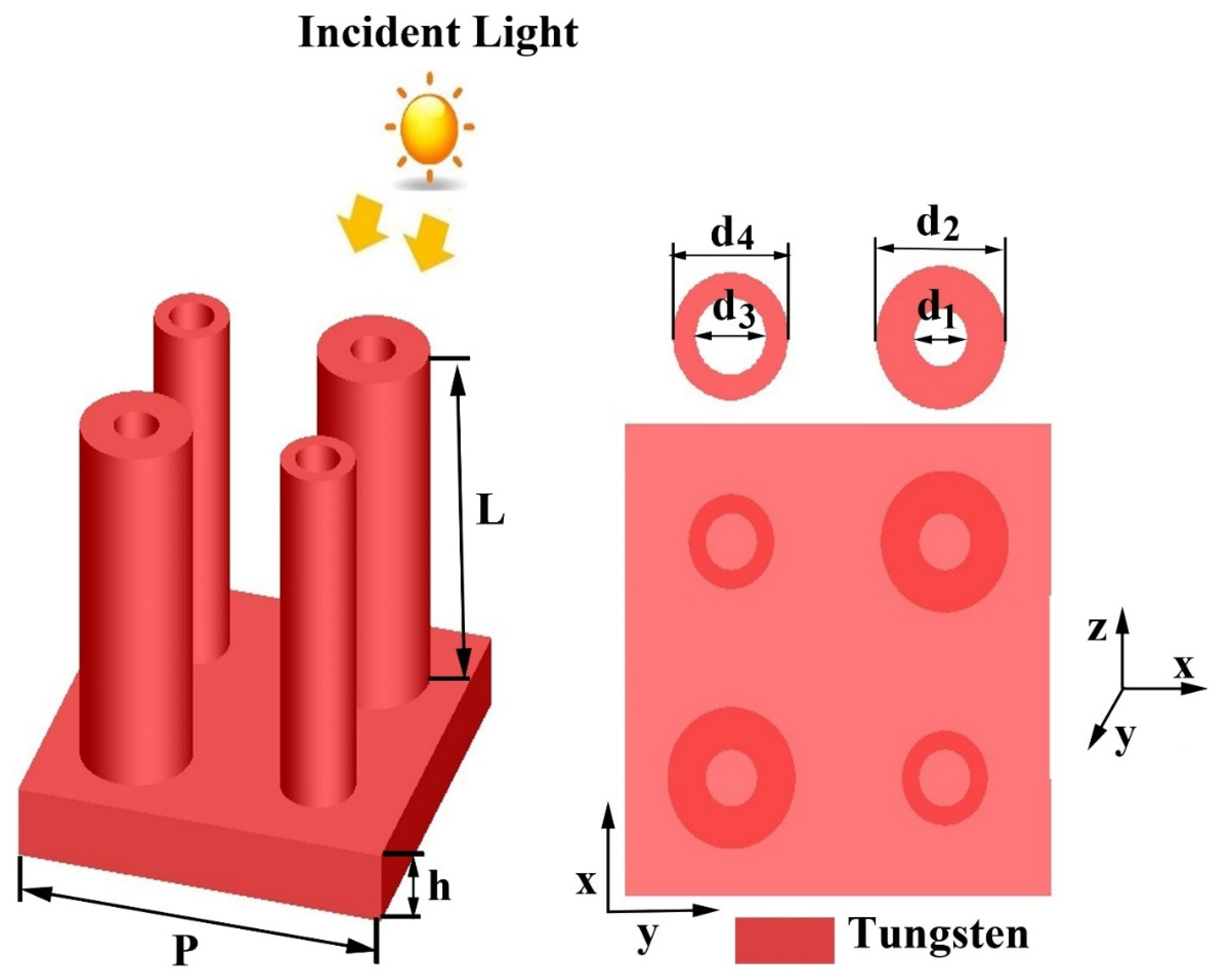

2. Design Considerations

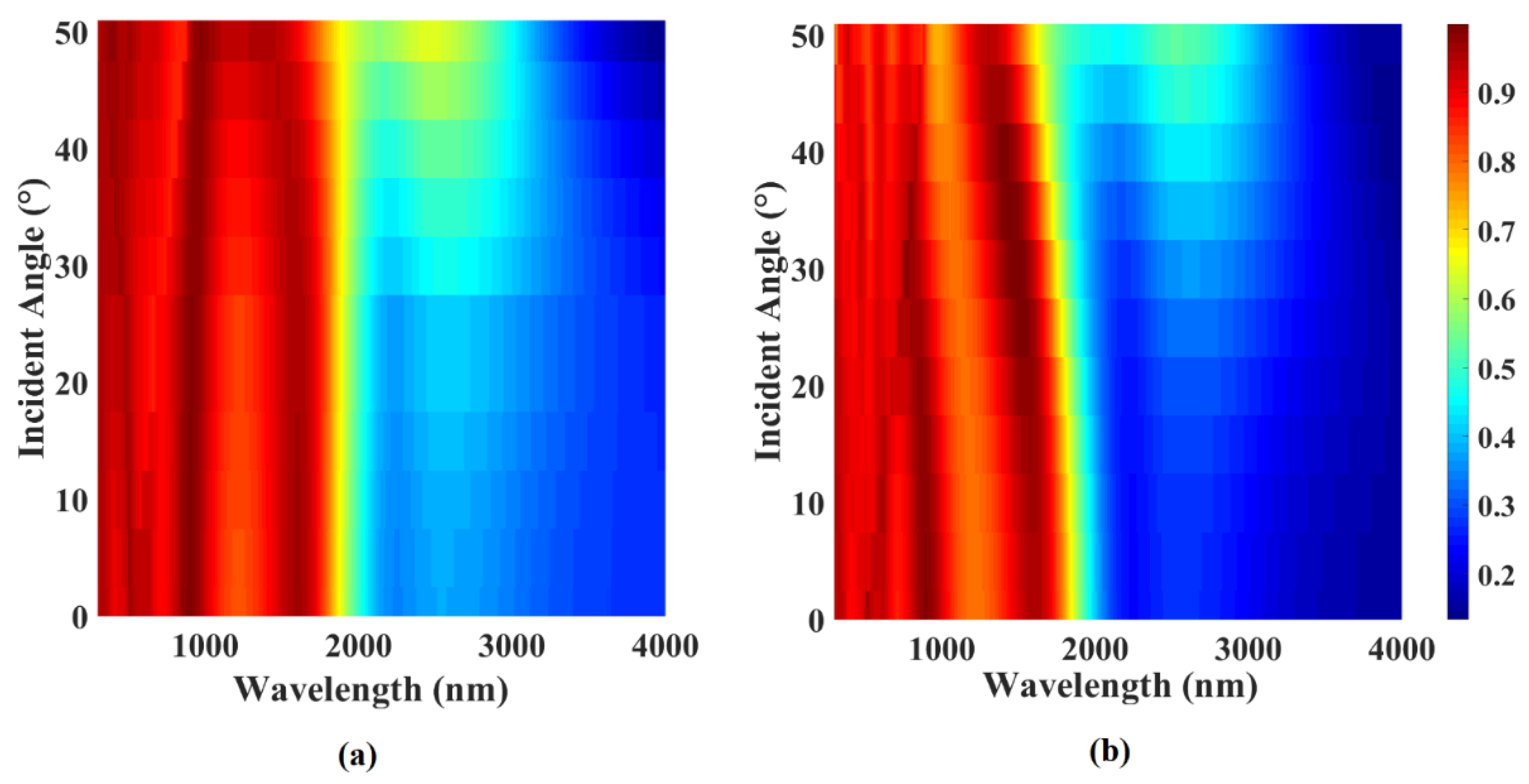

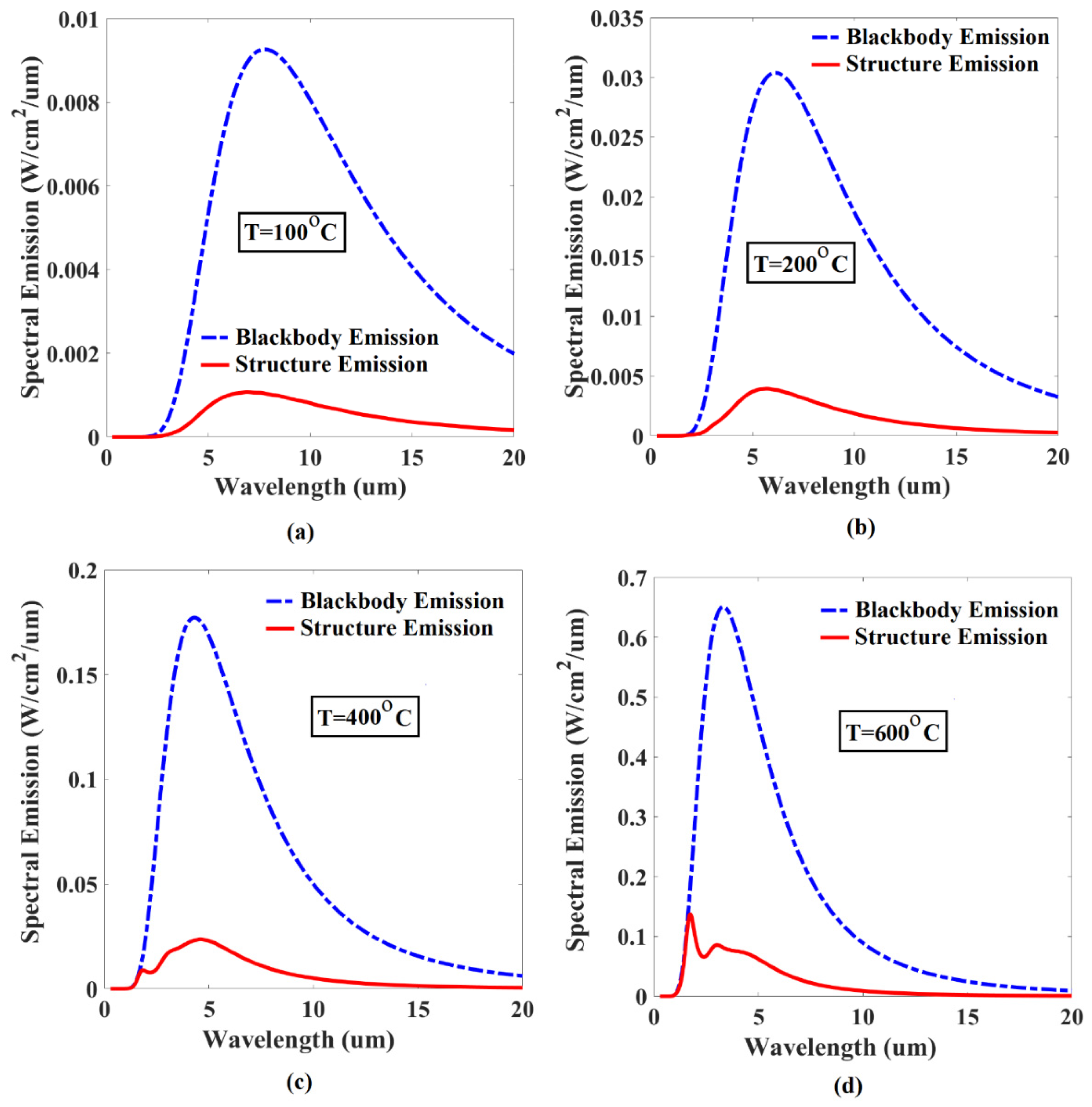

3. Numerical Results and Optical Performance Analysis

4. Conclusions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Thekaekara, M.P. The Solar Constant and The Solar Spectrum Measured from a Research Aircraft; NASA Goddard Space Flight Center: Greenbelt, MD, USA, 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Green, M.A. Solar Cells: Operating Principles, Technology, and System Applications; UNSW Press: Sydney, Australia, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Abdel-Latif, G.Y.; Hameed, M.F.O.; Obayya, S.S.A. Thermal absorber with epsilon-near-zero metamaterial based on 2D square spiral design. J. Opt. Soc. Am. B 2021, 38, 3878–3885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Latif, G.Y.; Hameed, M.F.O.; Obayya, S.S.A. Characteristics of thermophotovoltaic emitter based on 2D cylindrical gear grating. Opt. Quantum Electron. 2021, 53, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Liu, H.; Zhu, J. Solar thermophotovoltaics: Progress, challenges, and opportunities. APL Mater. 2019, 7, 080906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Datas, A.; Martí, A. Thermophotovoltaic energy in space applications: Review and future potential. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2017, 161, 285–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spirkl, W.; Ries, H. Solar thermophotovoltaics: An assessment. J. Appl. Phys. 1985, 57, 4409–4414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, P.; Luque, A. Solar thermophotovoltaics: Brief review and a new look. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 1994, 33, 11–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LaPotin, A.; Schulte, K.L.; Steiner, M.A.; Buznitsky, K.; Kelsall, C.C.; Friedman, D.J.; Tervo, E.J.; France, R.M.; Young, M.R.; Rohskopf, A.J.N. Thermophotovoltaic efficiency of 40%. Nature 2022, 604, 287–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greffet, J.-J.; Carminati, R.; Joulain, K.; Mulet, J.-P.; Mainguy, S.; Chen, Y. Coherent emission of light by thermal sources. Nature 2002, 416, 61–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marquier, F.; Joulain, K.; Mulet, J.-P.; Carminati, R.; Greffet, J. Engineering infrared emission properties of silicon in the near field and the far field. Opt. Commun. 2004, 237, 379–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.; Li, Y.; Chen, F.; Yang, W.; Wang, B. A perfect absorber for ultra-long-wave infrared based on a cross-shaped resonator structure. Plasmonics 2024, 19, 2077–2086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Q.; Zheng, L.; Chen, F.; Zhang, H.; Yang, W. High-efficiency broadband perfect absorber based on a multilayered pyramid structure. Phys. Scr. 2022, 98, 015811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maruyama, S.; Kashiwa, T.; Yugami, H.; Esashi, M. Thermal radiation from two-dimensionally confined modes in microcavities. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2001, 79, 1393–1395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahan, N.; Niv, A.; Biener, G.; Gorodetski, Y.; Kleiner, V.; Hasman, E. Extraordinary coherent thermal emission from SiC due to coupled resonant cavities. J. Heat Transf. 2008, 130, 112401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Lee, B.J.; Wang, X.; Zhang, Z. Spatial and temporal coherence of thermal radiation in asymmetric Fabry–Perot resonance cavities. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2009, 52, 3024–3031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Basu, S.; Zhang, Z. Direct measurement of thermal emission from a Fabry–Perot cavity resonator. J. Heat Transf. 2012, 134, 072701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.; Li, Y.; Chen, F.; Cheng, S.; Yang, W.; Wang, B.; Yi, Z.; Yao, D. Ultra-broadband solar absorber based on TiN metamaterial from visible light to mid-infrared. J. Opt. Soc. Am. B 2023, 40, 3057–3064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narayanaswamy, A.; Chen, G. Thermal emission control with one-dimensional metallodielectric photonic crystals. Phys. Rev. B 2004, 70, 125101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, B.J.; Chen, Y.-B.; Zhang, Z. Surface waves between metallic films and truncated photonic crystals observed with reflectance spectroscopy. Opt. Lett. 2008, 33, 204–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, B.J.; Wang, L.; Zhang, Z. Coherent thermal emission by excitation of magnetic polaritons between periodic strips and a metallic film. Opt. Express 2008, 16, 11328–11336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Zhang, Z. Wavelength-selective and diffuse emitter enhanced by magnetic polaritons for thermophotovoltaics. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2012, 100, 063902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landy, N.I.; Sajuyigbe, S.; Mock, J.J.; Smith, D.R.; Padilla, W.J. Perfect metamaterial absorber. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2008, 100, 207402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, N.; Mesch, M.; Weiss, T.; Hentschel, M.; Giessen, H. Infrared perfect absorber and its application as plasmonic sensor. Nano Lett. 2010, 10, 2342–2348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Tyler, T.; Starr, T.; Starr, A.F.; Jokerst, N.M.; Padilla, W.J. Taming the blackbody with infrared metamaterials as selective thermal emitters. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2011, 107, 045901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendrickson, J.; Guo, J.; Zhang, B.; Buchwald, W.; Soref, R. Wideband perfect light absorber at midwave infrared using multiplexed metal structures. Opt. Lett. 2012, 37, 371–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Wu, X.; Yuan, L.; Zhou, C.; Wang, Y.; Huang, K.; Feng, S. Solar selective absorbers with foamed nanostructure prepared by hydrothermal method on stainless steel. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2016, 146, 99–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, J.; Ji, B.; Lin, J. High-performance tunable plasmonic absorber based on the metal-insulator-metal grating nanostructure. Plasmonics 2017, 12, 151–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, J.; Wang, J.; Liu, X.; Padilla, W.J.; Zhou, L.; Qiu, M. High performance optical absorber based on a plasmonic metamaterial. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2010, 96, 251104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, F.; Yang, C.; Zhang, X.; Wang, J.; Ou, Z.; Deng, J.; Yan, B. Inverse design of metalenses with polarization and chromatic dispersion modulation via transfer learning. Opt. Lett. 2024, 50, 189–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Zhao, L.; Cheng, Y.; Yan, Z.; Wang, X.; Tang, C.; Gao, F.; Yi, Z.; Zhu, M. Bandwidth-tunable absorption enhancement of visible and near-infrared light in monolayer graphene by localized plasmon resonances and their diffraction coupling. Results Phys. 2023, 49, 106471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Nie, Q.; Tang, C.; Yan, B.; Liu, F.; Zhu, M. Bandwidth tunability of graphene absorption enhancement by hybridization of delocalized surface plasmon polaritons and localized magnetic plasmons. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 2024, 19, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gu, P.; Li, D.; Zhu, H.; Chen, J.; Zhang, Z.; Hu, E.; Deng, J.; Tang, C.; Chen, Z. Arrays of nanoscale-thick ITO hemispherical shells as saturable absorbers for Q-switched all-fiber lasers. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2024, 7, 20579–20586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, C.; Nie, Q.; Cai, P.; Liu, F.; Gu, P.; Yan, Z.; Huang, Z.; Zhu, M. Ultra-broadband near-infrared absorption enhancement of monolayer graphene by multiple-resonator approach. Diam. Relat. Mater. 2024, 141, 110607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Cheng, S.; Zhang, H.; Yang, W.; Yi, Z.; Yi, Y.; Wang, J.; Ahmad, S.; Raza, R. Ultrathin broadband terahertz metamaterial based on single-layer nested patterned graphene. Phys. Lett. A 2025, 534, 130262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Cheng, S.; Yi, Z.; Zhang, H.; Song, Q.; Hao, Z.; Sun, T.; Wu, P.; Zeng, Q.; Raza, R. Advanced optical reinforcement materials based on three-dimensional four-way weaving structure and metasurface technology. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2025, 126, 033503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Q.; Chen, F.; Cheng, S.; Yang, W.; Yi, Z. Broad band solar cell absorber based on double-ring coupled disk resonator structure: From visible to mid infrared. Phys. Scr. 2023, 98, 045513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, J.-Y.; Wang, H.; Wang, L. Tungsten nanowire metamaterials as selective solar thermal absorbers by excitation of magnetic polaritons. J. Heat Transf. 2017, 139, 052401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shchegolkov, D.Y.; Azad, A.K.; O’hara, J.; Simakov, E. Perfect subwavelength fishnetlike metamaterial-based film terahertz absorbers. Phys. Rev. B 2010, 82, 205117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Koschny, T.; Soukoulis, C.M. Wide-angle and polarization-independent chiral metamaterial absorber. Phys. Rev. B 2009, 80, 033108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Cheng, S.; Zhang, H.; Yi, Z.; Tang, B.; Chen, J.; Zhang, J.; Tang, C. Ultra wideband absorption absorber based on Dirac semimetallic and graphene metamaterials. Phys. Lett. A 2024, 517, 129675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, S.; Li, W.; Zhang, H.; Akhtar, M.N.; Yi, Z.; Zeng, Q.; Ma, C.; Sun, T.; Wu, P.; Ahmad, S. High sensitivity five band tunable metamaterial absorption device based on block like Dirac semimetals. Opt. Commun. 2024, 569, 130816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Z.; Liu, H.; Zhang, H.; Cheng, S.; Yi, Y.; Yi, Z.; Wang, J.; Zhang, J. Tunable ultra-sensitive four-band terahertz sensors based on Dirac semimetals. Photonics Nanostructures Fundam. Appl. 2025, 63, 101347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Liu, G.; Huang, Z.; Liu, X.; Fu, G. Ultra-broadband perfect solar absorber by an ultra-thin refractory titanium nitride meta-surface. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2018, 179, 346–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Wang, L. Tailoring thermal radiative properties with film-coupled concave grating metamaterials. J. Quant. Spectrosc. Radiat. Transf. 2015, 158, 127–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Qu, Y.; Du, K.; Bai, S.; Tian, J.; Pan, M.; Ye, H.; Qiu, M.; Li, Q. Broadband optical absorption based on single-sized metal-dielectric-metal plasmonic nanostructures with high-ε” metals. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2017, 110, 101101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rana, A.S.; Mehmood, M.Q.; Jeong, H.; Kim, I.; Rho, J. Tungsten-based ultrathin absorber for visible regime. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 2443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mou, N.; Liu, X.; Wei, T.; Dong, H.; He, Q.; Zhou, L.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, L.; Sun, S. Large-scale, low-cost, broadband and tunable perfect optical absorber based on phase-change material. Nanoscale 2020, 12, 5374–5379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Qin, Z.; Liang, Z.; Meng, D.; Xu, H.; Smith, D.R.; Liu, Y. Ultra-broadband metamaterial absorbers from long to very long infrared regime. Light. Sci. Appl. 2021, 10, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Sun, Y.; Wu, B.; Sun, C.; Wu, X. Perfect metamaterial absorber for solar energy utilization. Int. J. Therm. Sci. 2022, 179, 107638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Varshney, G. Thermally-electrically tunable broadband ultrathin metal-free THz Absorber. IEEE Photon-Technol. Lett. 2023, 35, 1235–1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palik, E.D. Handbook of Optical Constants of Solids; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1998; Volume 3. [Google Scholar]

- Ansys Optics—Optics and Photonics Simulation Software. AnsysLumerical, Lumerical Solutions, Inc.: Vancouver, BC, Canada. Available online: https://www.lumerical.com (accessed on 15 May 2025).

- Zhang, Z.M. Nano/Microscale Heat Transfer; Springer Nature: Durham, NC, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Fowles, G.R. Introduction to Modern Optics; Courier Corporation: Washington, DC, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- ASTM. Reference Solar Spectral Irradiance: Air Mass 1.5 Spectra. 2011. Available online: http://rredc.nrel.gov/solar/spectra/am1.5/ (accessed on 15 March 2025).

- Wang, H.; Wang, L. Perfect selective metamaterial solar absorbers. Opt. Express 2013, 21, A1078–A1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergman, T.L. Fundamentals of Heat and Mass Transfer; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Khodasevych, I.E.; Wang, L.; Mitchell, A.; Rosengarten, G. Micro-and nanostructured surfaces for selective solar absorption. Adv. Opt. Mater. 2015, 3, 852–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, Q.; Alshehri, H.; Yang, Y.; Ye, H.; Wang, L. Plasmonic light trapping for enhanced light absorption in film-coupled ultrathin metamaterial thermophotovoltaic cells. Front. Energy 2018, 12, 185–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tittl, A.; Harats, M.G.; Walter, R.; Yin, X.; Schäferling, M.; Liu, N.; Rapaport, R.; Giessen, H. Quantitative angle-resolved small-spot reflectance measurements on plasmonic perfect absorbers: Impedance matching and disorder effects. ACS Nano 2014, 8, 10885–10892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, H.; Hu, L.; Lu, Y.; Xu, J.; Chen, Y. Dual-band metamaterial absorbers in the visible and near-infrared regions. J. Phys. Chem. C 2019, 123, 10028–10033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rana, A.S.; Zubair, M.; Chen, Y.; Wang, Z.; Deng, J.; Chani, M.T.S.; Danner, A.; Teng, J.; Mehmood, M.Q. Broadband solar absorption by chromium metasurface for highly efficient solar thermophotovoltaic systems. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2023, 171, 113005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, H.; Sun, Y.; Liu, J.; Wang, X. Genetic algorithm optimization for highly efficient solar thermal absorber based on optical metamaterials. J. Quant. Spectrosc. Radiat. Transf. 2021, 271, 107712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Q.; Chen, M.; Cai, W. Numerically investigating a wide-angle polarization-independent ultra-broadband solar selective absorber for high-efficiency solar thermal energy conversion. Sol. Energy 2019, 184, 489–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Q.; Yin, Q.; Chen, L.; Wang, Z.; Chen, X. Perfect spectrally selective solar absorber with dielectric filled fishnet tungsten grating for solar energy harvesting. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2020, 215, 110664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Chen, Y.; Tian, Y.; Liang, J.; Yang, W. Ultra-broadband metamaterial perfect solar absorber with polarization-independent and large incident angle-insensitive. Opt. Laser Technol. 2022, 156, 108591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Verheijen, M.A.; Wu, L.; Karwal, S.; Vandalon, V.; Knoops, H.C.; Sundaram, R.S.; Hofmann, J.P.; Kessels, W.E.; Bol, A.A. Low-temperature plasma-enhanced atomic layer deposition of 2-D MoS 2: Large area, thickness control and tuneable morphology. Nanoscale 2018, 10, 8615–8627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, S. Silicon Processing for the VLSI Era; Lattice: Sunset Beach, CA, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Fang, Y.; Dai, L.; Yang, F.; Yue, G.; Zuo, P.; Chen, H. Fabrication of metal nano-wires by laser interference lithography using a tri-layer resist process. Opt. Quantum Electron. 2016, 48, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Mesh Cell Size (nm) | Peak Abs. 300 nm | Peak Abs. 600 nm | Peak Abs. 880 nm | Peak Abs. 1545 nm | Relative Change Compared to Finer Mesh (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10 nm | 0.939 | 0.938 | 0.981 | 0.930 | 0.40% |

| 7 nm | 0.936 | 0.937 | 0.983 | 0.921 | 0.16% |

| 5 nm | 0.933 | 0.938 | 0.984 | 0.920 | 0.03% |

| 4 nm | 0.933 | 0.937 | 0.984 | 0.920 | — (the finest mesh) |

| Mode | (F) | (F) | (F) | (H) | (H) | (H) | (H) | LC-Predicted λ (nm) | Simulated λ (nm) | Error (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MP4 | 9.55 × 10−19 | 5.31 × 10−19 | 7.43 × 10−19 | 1.73 × 10−12 | 1.63 × 10−12 | 1.73 × 10−13 | 1.63 × 10−13 | 5.0 × 10−13 | 830 | 600 | 8% |

| MP3 | 9.55 × 10−19 | 5.31 × 10−19 | 7.43 × 10−19 | 1.73 × 10−12 | 1.63 × 10−12 | 1.73 × 10−13 | 1.63 × 10−13 | 5.0 × 10−13 | 1110 | 880 | 6% |

| MP2 | 9.55 × 10−19 | 5.31 × 10−19 | 7.43 × 10−19 | 1.73 × 10−12 | 1.63 × 10−12 | 1.73 × 10−13 | 1.63 × 10−13 | 5.0 × 10−13 | 1660 | 1545 | 3% |

| MP1 | 9.55 × 10−19 | 5.31 × 10−19 | 7.43 × 10−19 | 1.73 × 10−12 | 1.63 × 10−12 | 1.73 × 10−13 | 1.63 × 10−13 | 5.0 × 10−13 | 3330 | 3370 | 0.3% |

| Reference | Design | Number of Sheets | Materials | Absorption Performance | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Metal | Dielectric | ||||

| Xu et al. [62] | Nanodisk array | 3 | Al | SiO2 | Two peaks (0.92 and 0.99) |

| Rana et al. [63] | Cross-shaped | 3 | Cr | SiO2 | 0.9 (300–1200 nm) |

| Wu et al. [50] | Square array | 6 | Fe | SiO2 | 0.93 (400–2000 nm) |

| Cai et al. [64] | Square grating | 6 | W | SiO2 | 0.97 (300–2000 nm) |

| Ye et al. [65] | Sphere array | 3 | W | SiO2 | 0.95 (300–1777 nm) |

| Liang et al. [66] | Fishnet-shaped | 2 | W | SiO2 | 0.935 (400–1200 nm) |

| Zhou et al. [67] | Nanodisk array | 4 | TiN | Si3N4 | 0.97 (400–2500 nm) |

| Chang et al. [38] | Nanowire array | 1 | W | air | ≈0.93 (300–1500 nm) |

| This study | Asymmetric ring | 1 | W | air | 0.95 (300–2000 nm) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Abdel-Latif, G.Y. Asymmetric Metamaterial Nanowire Structure for Selective Solar Absorption. Electronics 2025, 14, 4804. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14244804

Abdel-Latif GY. Asymmetric Metamaterial Nanowire Structure for Selective Solar Absorption. Electronics. 2025; 14(24):4804. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14244804

Chicago/Turabian StyleAbdel-Latif, Ghada Yassin. 2025. "Asymmetric Metamaterial Nanowire Structure for Selective Solar Absorption" Electronics 14, no. 24: 4804. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14244804

APA StyleAbdel-Latif, G. Y. (2025). Asymmetric Metamaterial Nanowire Structure for Selective Solar Absorption. Electronics, 14(24), 4804. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14244804