Using Denoising Diffusion Model for Predicting Global Style Tokens in an Expressive Text-to-Speech System

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. State of the Art

1.2. Problem Formulation

2. Related Work

3. Materials and Methods

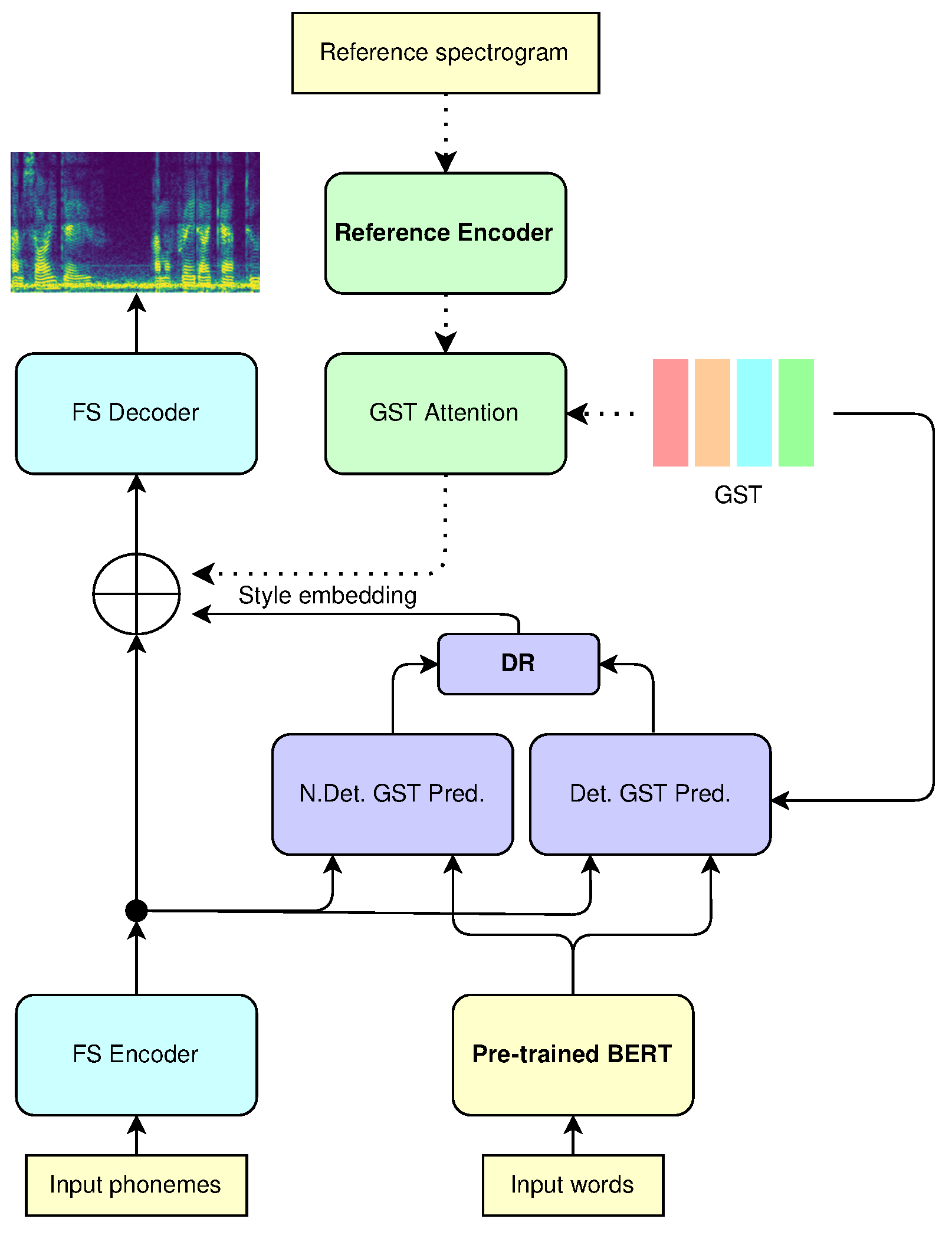

3.1. GST FastSpeech

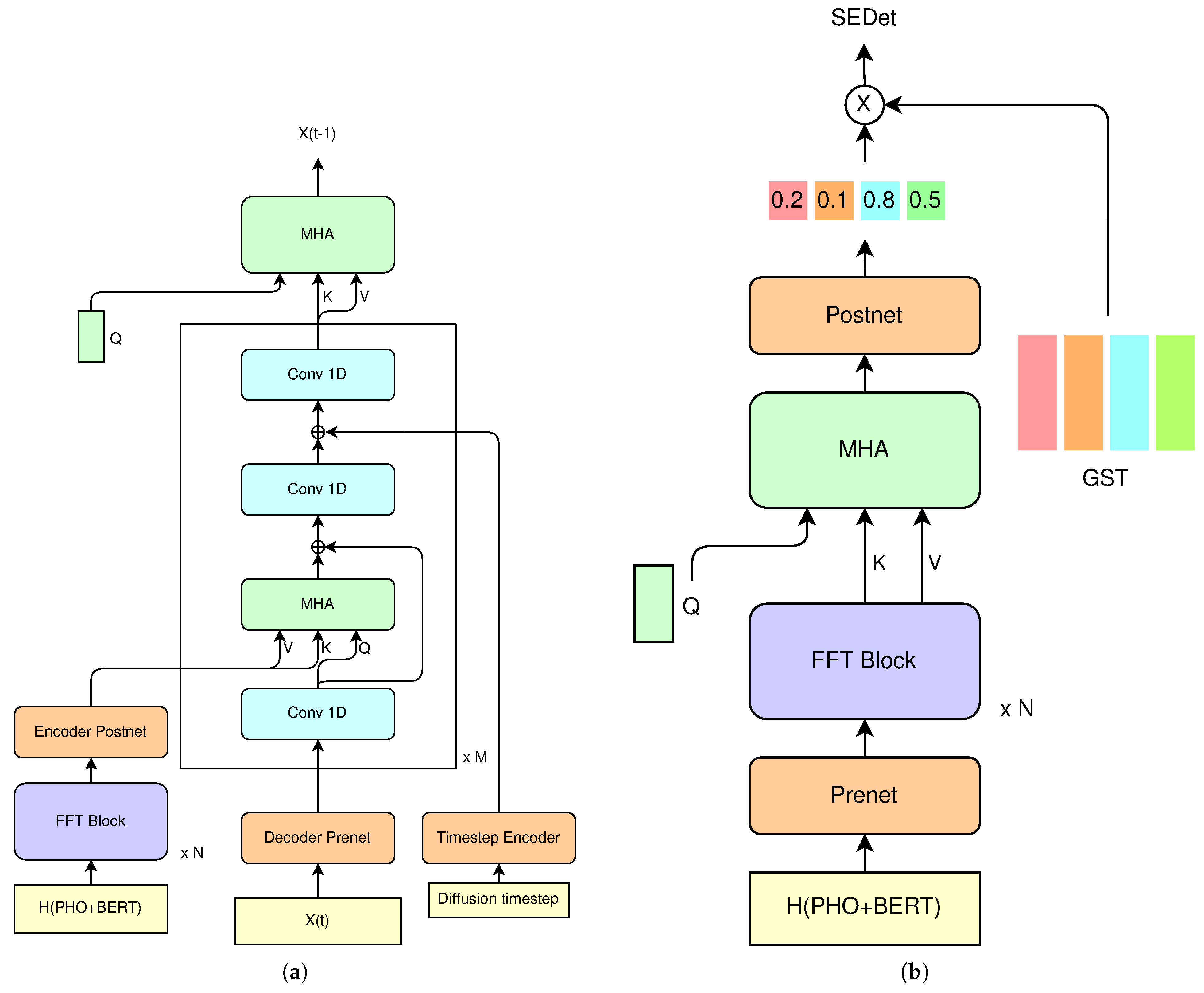

3.2. Denoising Diffusion Model for GST Prediction

3.3. Non-Deterministic GST Predictor

| Algorithm 1 Backward diffusion sampling in a diffusion framework |

|

3.4. Deterministic GST Predictor

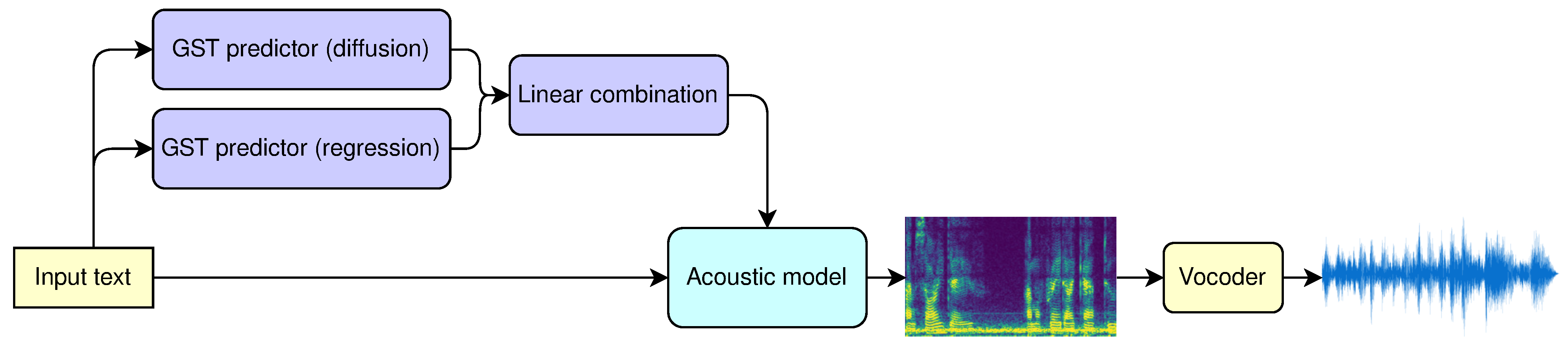

3.5. Inference

- Process the input phonemes through the encoder of the backbone model and obtain .

- Concatenate BERT representations with encoder’s output to obtain .

- Calculate using Algorithm 1, where the conditioning information y is .

- Calculate using the Deterministic GST predictor and substitute it into the Equation (3) to obtain .

- Calculate the final style embedding as .

- Add the final style embedding to and pass it through the backbone model’s decoder to obtain the output spectrogram.

- Convert the output spectrogram to the output waveform using a vocoder.

4. Results

4.1. Experimental Setup

4.2. Speech Quality Evaluation with Objective Metrics

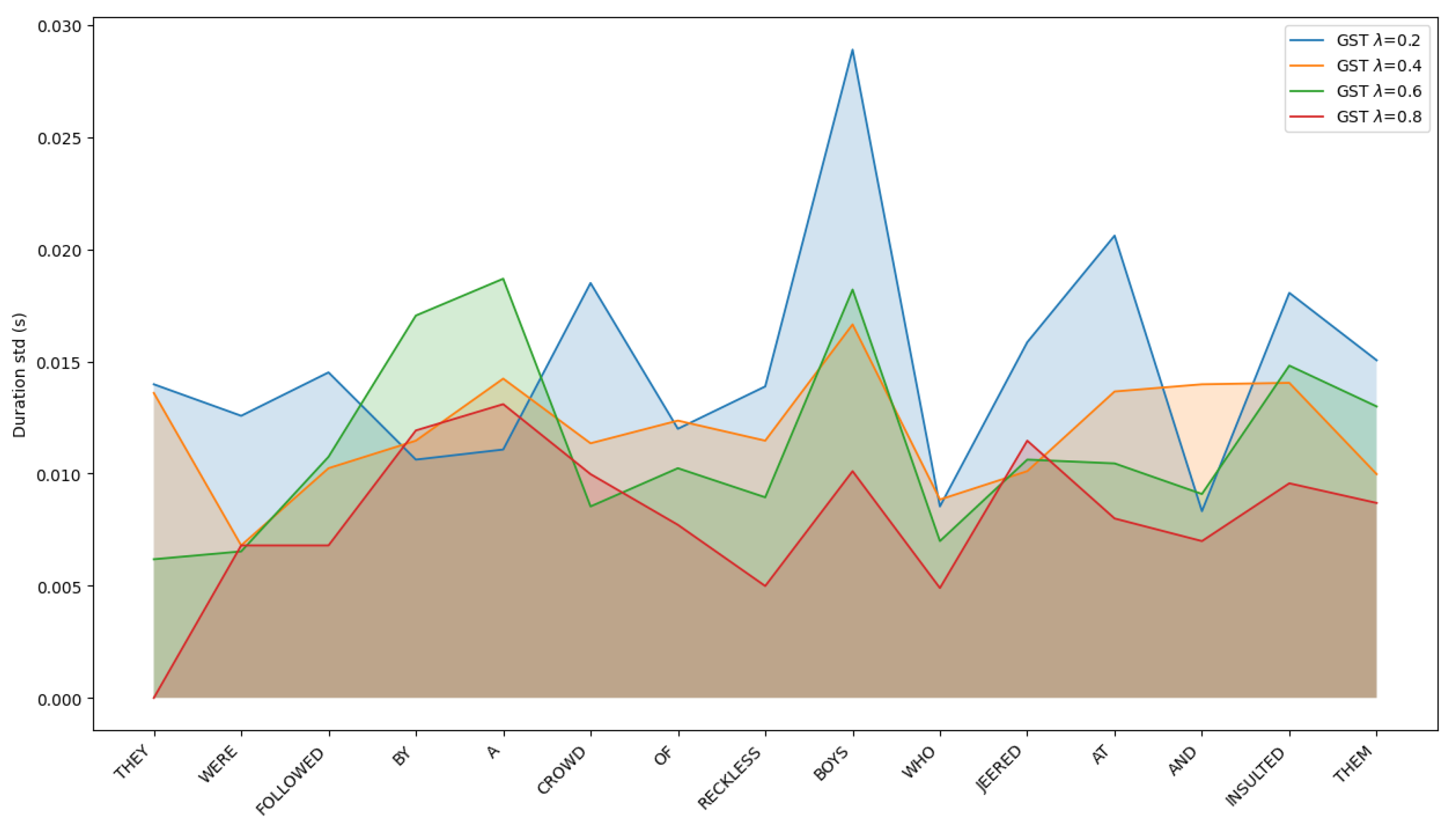

4.3. Diversity of Expression Evaluated with Objective Metrics

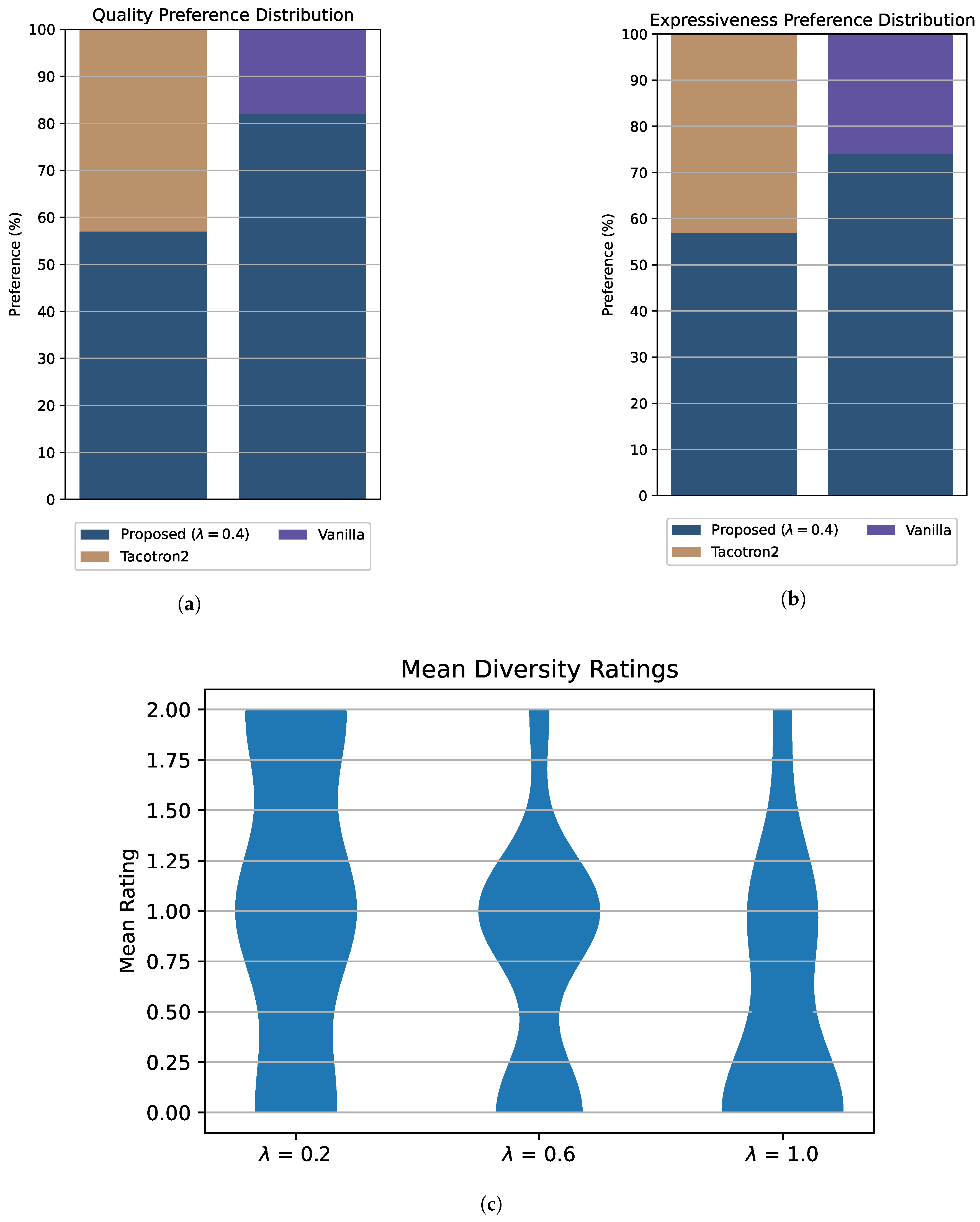

4.4. Subjective Evaluation of Speech Quality and Diversity

- H1: Speech generated by the proposed system is comparable to that produced by the baseline systems in terms of quality (lack of artifacts, quality of sound, lack of spelling errors).

- H2: Speech generated by the proposed system is comparable to that produced by the baseline systems in terms of expressiveness (natural intonation, consistent rhythm).

- H3: Manipulating the hyperparameter of the system has visible influence on diversity of the high-level features of the produced speech (intonation, breaks, duration of words)

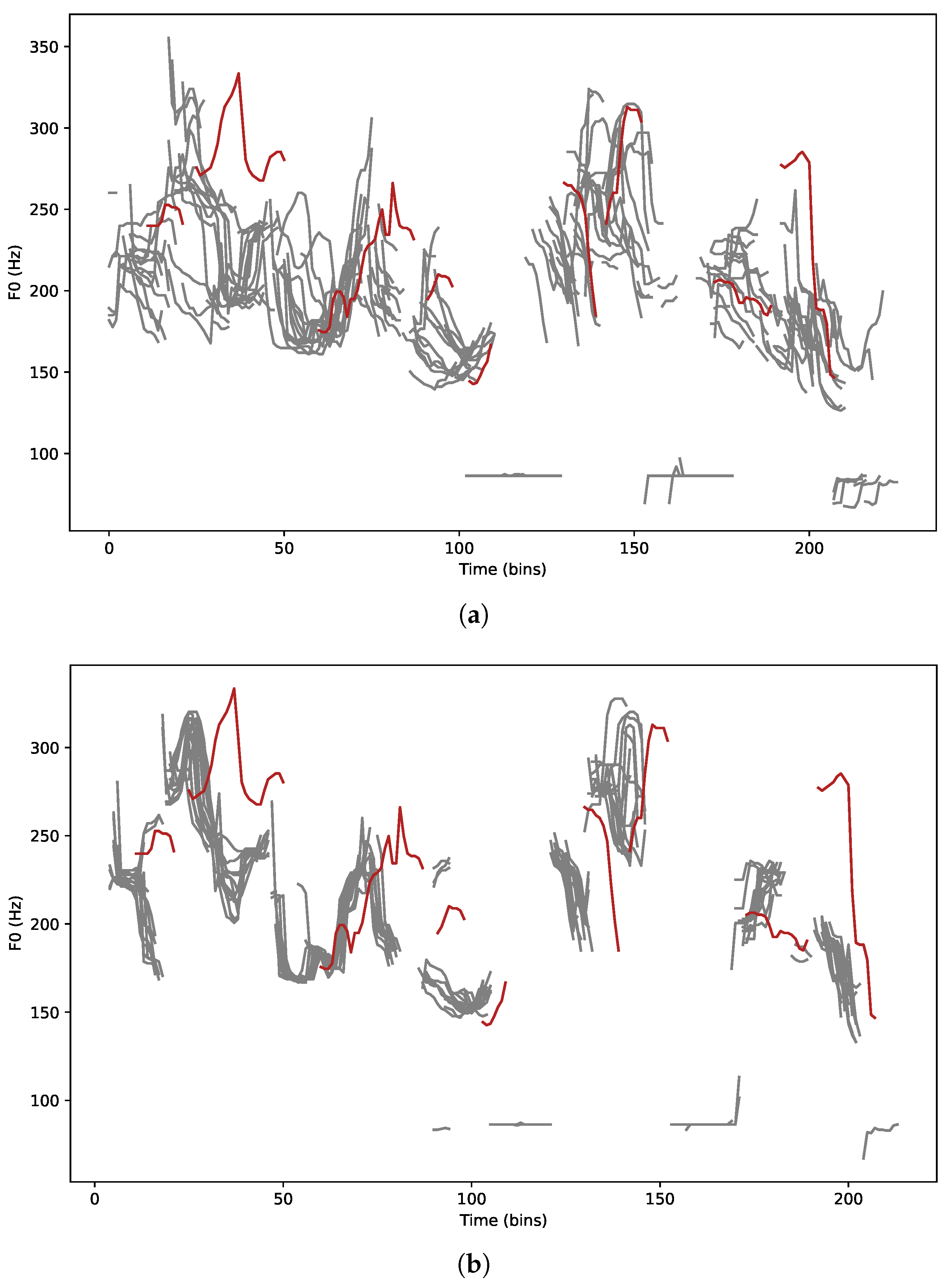

4.5. Case Study: Diversity of Word Durations

5. Discussion

- The proposed method of explicit style modeling improves the quality of the generated speech, which proves its value in constructing robust TTS systems.

- The use of a diffusion framework in predicting the stylistic features has a visible influence on the diversity of high-level prosodic characteristics, such as pitch and word duration.

- Blending the regressive and diffusion-based predictors allows for smooth control of the produced speech’s prosody. As a result, by manipulating a single hyperparameter, we can decide whether, e.g., the pitch track will be centered near the average or deviate.

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| TTS | Text-to-Speech |

| ETTS | Expressive Text-to-Speech |

| GST | Global Style Tokens |

| WSV | Word-level Style Variation |

| BERT | Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformer |

| FFT | Feed Forward Transformer |

| DDPM | Denoising Diffusion Probabilistic Models |

| ELBO | Evidence Lower Bound |

| DTW | Dynamic Time Warping |

| RMSE | Root Mean Square Error |

| MCD | Mean Cepstral Distortion |

| MRE | Mean Relative Error |

References

- Ren, Y.; Ruan, Y.; Tan, X.; Qin, T.; Zhao, S.; Zhao, Z.; Liu, T.Y. Fastspeech: Fast, robust and controllable text to speech. In Proceedings of the 33rd International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 8–14 December 2019; Volume 32. [Google Scholar]

- Barakat, H.; Turk, O.; Demiroglu, C. Deep learning-based expressive speech synthesis: A systematic review of approaches, challenges, and resources. Eurasip J. Audio Speech Music. Process. 2024, 2024, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Stanton, D.; Zhang, Y.; Ryan, R.S.; Battenberg, E.; Shor, J.; Xiao, Y.; Jia, Y.; Ren, F.; Saurous, R.A. Style tokens: Unsupervised style modeling, control and transfer in end-to-end speech synthesis. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning, PMLR, Stockholm, Sweden, 10–15 July 2018; pp. 5180–5189. [Google Scholar]

- Stanton, D.; Wang, Y.; Skerry-Ryan, R. Predicting expressive speaking style from text in end-to-end speech synthesis. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE Spoken Language Technology Workshop (SLT), Athens, Greece, 18–21 December 2018; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 595–602. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, Y.; Hu, C.; Tan, X.; Qin, T.; Zhao, S.; Zhao, Z.; Liu, T.Y. FastSpeech 2: Fast and High-Quality End-to-End Text to Speech. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2006.04558. [Google Scholar]

- Ho, J.; Jain, A.; Abbeel, P. Denoising diffusion probabilistic models. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2020, 33, 6840–6851. [Google Scholar]

- Kingma, D.P.; Welling, M. Auto-Encoding Variational Bayes. arXiv 2013, arXiv:1312.6114. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, J.; Ding, D.; Li, Y.; Lu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, Y.C.; Xue, G. M2SILENT: Enabling Multi-user Silent Speech Interactions via Multi-directional Speakers in Shared Spaces. In Proceedings of the 2025 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (CHI ’25), Yokohama, Japan, 26 April–1 May 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brade, S.; Anderson, S.; Kumar, R.; Jin, Z.; Truong, A. SpeakEasy: Enhancing Text-to-Speech Interactions for Expressive Content Creation. In Proceedings of the 2025 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (CHI ’25), Yokohama, Japan, 26 April–1 May 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danielescu, A.; Horowit-Hendler, S.A.; Pabst, A.; Stewart, K.M.; Gallo, E.M.; Aylett, M.P. Creating Inclusive Voices for the 21st Century: A Non-Binary Text-to-Speech for Conversational Assistants. In Proceedings of the 2023 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (CHI ’23), Hamburg, Germany, 23–28 April 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Wang, S.; Hu, Z.; Fan, C.; Lv, T.; Ding, Y.; Deng, Z.; Yu, X. Styletalk: One-shot talking head generation with controllable speaking styles. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Washington, DC, USA, 7–14 February 2023; Volume 37, pp. 1896–1904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Skerry-Ryan, R.; Stanton, D.; Wu, Y.; Weiss, R.J.; Jaitly, N.; Yang, Z.; Xiao, Y.; Chen, Z.; Bengio, S.; et al. Tacotron: Towards End-to-End Speech Synthesis. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1703.10135. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, J.; Pang, R.; Weiss, R.J.; Schuster, M.; Jaitly, N.; Yang, Z.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Skerrv-Ryan, R.; et al. Natural tts synthesis by conditioning wavenet on mel spectrogram predictions. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP), Calgary, AB, Canada, 15–20 April 2018; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 4779–4783. [Google Scholar]

- van den Oord, A.; Dieleman, S.; Zen, H.; Simonyan, K.; Vinyals, O.; Graves, A.; Kalchbrenner, N.; Senior, A.; Kavukcuoglu, K. WaveNet: A Generative Model for Raw Audio. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1609.03499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arık, S.Ö.; Chrzanowski, M.; Coates, A.; Diamos, G.; Gibiansky, A.; Kang, Y.; Li, X.; Miller, J.; Ng, A.; Raiman, J.; et al. Deep voice: Real-time neural text-to-speech. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning, PMLR, Sydney, Australia, 6–11 August 2017; pp. 195–204. [Google Scholar]

- Li, N.; Liu, S.; Liu, Y.; Zhao, S.; Liu, M. Neural speech synthesis with transformer network. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Honolulu, HI, USA, 27–28 January 2019; Volume 33, pp. 6706–6713. [Google Scholar]

- Łańcucki, A. Fastpitch: Parallel text-to-speech with pitch prediction. In Proceedings of the ICASSP 2021–2021 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP), Toronto, ON, Canada, 6–11 June 2021; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 6588–6592. [Google Scholar]

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, Ł.; Polosukhin, I. Attention is all you need. In Proceedings of the 31st Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (NIPS 2017), Long Beach, CA, USA, 4–9 December 2017; Volume 30. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Yan, Z.; Chen, S.; Ye, T.; Ren, W.; Chen, E. NightHazeFormer: Single Nighttime Haze Removal Using Prior Query Transformer. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2305.09533. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Gu, J.; Dong, J.; Kong, L.; Yang, X. Xformer: Hybrid X-Shaped Transformer for Image Denoising. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2303.06440. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.; Chen, S.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Zhou, L.; Liu, S.; Chen, Z.; Liu, Y.; Wang, H.; Li, J.; et al. Neural Codec Language Models are Zero-Shot Text to Speech Synthesizers. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2301.02111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Y.; Lei, M.; Huang, Z.; Zhang, S.; Chen, Q.; Yan, Z.; Zhao, Z. ProsoSpeech: Enhancing Prosody With Quantized Vector Pre-training in Text-to-Speech. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2202.07816. [Google Scholar]

- Choromanski, K.; Likhosherstov, V.; Dohan, D.; Song, X.; Gane, A.; Sarlos, T.; Hawkins, P.; Davis, J.; Mohiuddin, A.; Kaiser, L.; et al. Rethinking Attention with Performers. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2009.14794. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S.; Li, B.Z.; Khabsa, M.; Fang, H.; Ma, H. Linformer: Self-Attention with Linear Complexity. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2006.04768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skerry-Ryan, R.; Battenberg, E.; Xiao, Y.; Wang, Y.; Stanton, D.; Shor, J.; Weiss, R.; Clark, R.; Saurous, R.A. Towards end-to-end prosody transfer for expressive speech synthesis with tacotron. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning, PMLR, Stockholm, Sweden, 10–15 July 2018; pp. 4693–4702. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.A.; Han, C.; Mesgarani, N. StyleTTS: A Style-Based Generative Model for Natural and Diverse Text-to-Speech Synthesis. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Signal Process. 2025, 19, 283–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.A.; Han, C.; Raghavan, V.; Mischler, G.; Mesgarani, N. StyleTTS 2: Towards Human-Level Text-to-Speech through Style Diffusion and Adversarial Training with Large Speech Language Models. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, New Orleans, LA, USA, 10–16 December 2023; Oh, A., Naumann, T., Globerson, A., Saenko, K., Hardt, M., Levine, S., Eds.; Curran Associates, Inc.: Red Hook, NY, USA, 2023; Volume 36, pp. 19594–19621. [Google Scholar]

- Min, D.; Lee, D.B.; Yang, E.; Hwang, S.J. Meta-StyleSpeech: Multi-Speaker Adaptive Text-to-Speech Generation. In Proceedings of the 38th International Conference on Machine Learning, PMLR, Virtual, 18–24 July 2021; Meila, M., Zhang, T., Eds.; PMLR: New York, NY, USA, 2021; Volume 139, pp. 7748–7759. [Google Scholar]

- Défossez, A.; Copet, J.; Synnaeve, G.; Adi, Y. High Fidelity Neural Audio Compression. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2210.13438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, P.; Ling, Z.; Liu, L.; Jiang, Y.; Wu, H.; Dai, L. End-to-End Emotional Speech Synthesis Using Style Tokens and Semi-Supervised Training. In Proceedings of the 2019 Asia-Pacific Signal and Information Processing Association Annual Summit and Conference (APSIPA ASC), Lanzhou, China, 18–21 November 2019; pp. 623–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Meng, Y.; Li, C.; Wu, Z.; Meng, H.; Weng, C.; Su, D. Enhancing speaking styles in conversational text-to-speech synthesis with graph-based multi-modal context modeling. In Proceedings of the ICASSP 2022-2022 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP), Singapore, 22–27 May 2022; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2022; pp. 7917–7921. [Google Scholar]

- An, X.; Wang, Y.; Yang, S.; Ma, Z.; Xie, L. Learning Hierarchical Representations for Expressive Speaking Style in End-to-End Speech Synthesis. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE Automatic Speech Recognition and Understanding Workshop (ASRU), Singapore, 14–18 December 2019; pp. 184–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.J.; Ling, Z.H. Extracting and Predicting Word-Level Style Variations for Speech Synthesis. IEEE/ACM Trans. Audio Speech Lang. Process. 2021, 29, 1582–1593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devlin, J.; Chang, M.W.; Lee, K.; Toutanova, K. Bert: Pre-training of deep bidirectional transformers for language understanding. In Proceedings of the 2019 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies, Volume 1 (Long and Short Papers), Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2–7 June 2019; pp. 4171–4186. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z.; Wu, N.; Zhang, Y.; Ling, Z. Integrating Discrete Word-Level Style Variations into Non-Autoregressive Acoustic Models for Speech Synthesis. In Proceedings of the Interspeech 2022, Incheon, Republic of Korea, 18–22 September 2022; pp. 5508–5512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, M.; Kim, H.; Cheon, S.J.; Choi, B.J.; Kim, N.S. Diff-TTS: A Denoising Diffusion Model for Text-to-Speech. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2104.01409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shih, K.J.; Valle, R.; Badlani, R.; Lancucki, A.; Ping, W.; Catanzaro, B. RAD-TTS: Parallel Flow-Based TTS with Robust Alignment Learning and Diverse Synthesis. In Proceedings of the ICML Workshop on Invertible Neural Networks, Normalizing Flows, and Explicit Likelihood Models, Virtual, 23 July 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J.; Kong, J.; Son, J. Conditional Variational Autoencoder with Adversarial Learning for End-to-End Text-to-Speech. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2106.06103. [Google Scholar]

- Saharia, C.; Chan, W.; Saxena, S.; Li, L.; Whang, J.; Denton, E.; Ghasemipour, S.K.S.; Ayan, B.K.; Mahdavi, S.S.; Lopes, R.G.; et al. Photorealistic Text-to-Image Diffusion Models with Deep Language Understanding. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2205.11487. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Wang, X.; Hu, E.; Wang, A.; Shiri, B.; Lin, W. VNDHR: Variational Single Nighttime Image Dehazing for Enhancing Visibility in Intelligent Transportation Systems via Hybrid Regularization. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2025, 26, 10189–10203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, J.; Salimans, T.; Gritsenko, A.; Chan, W.; Norouzi, M.; Fleet, D.J. Video Diffusion Models. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2204.03458. [Google Scholar]

- Kong, Z.; Ping, W.; Huang, J.; Zhao, K.; Catanzaro, B. DiffWave: A Versatile Diffusion Model for Audio Synthesis. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2009.09761. [Google Scholar]

- Goodfellow, I.J.; Pouget-Abadie, J.; Mirza, M.; Xu, B.; Warde-Farley, D.; Ozair, S.; Courville, A.; Bengio, Y. Generative Adversarial Networks. arXiv 2014, arXiv:1406.2661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ba, J.L.; Kiros, J.R.; Hinton, G.E. Layer Normalization. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1607.06450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, K.; Zhang, X.; Ren, S.; Sun, J. Deep Residual Learning for Image Recognition. arXiv 2015, arXiv:1512.03385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, R.E.; Diaconu, C.D.; Markou, S.; Shysheya, A.; Foong, A.Y.K.; Mlodozeniec, B. Denoising Diffusion Probabilistic Models in Six Simple Steps. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2402.04384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elfwing, S.; Uchibe, E.; Doya, K. Sigmoid-weighted linear units for neural network function approximation in reinforcement learning. Neural Netw. 2018, 107, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, N.; Hinton, G.; Krizhevsky, A.; Sutskever, I.; Salakhutdinov, R. Dropout: A simple way to prevent neural networks from overfitting. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2014, 15, 1929–1958. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Y.; He, K. Group normalization. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV), Munich, Germany, 8–14 September 2018; pp. 3–19. [Google Scholar]

- Agarap, A.F. Deep Learning using Rectified Linear Units (ReLU). arXiv 2018, arXiv:1803.08375. [Google Scholar]

- Ito, K.; Johnson, L. The LJ Speech Dataset. 2017. Available online: https://keithito.com/LJ-Speech-Dataset/ (accessed on 29 November 2025).

- Park, K.; Kim, J. g2pE. 2019. Available online: https://github.com/Kyubyong/g2p (accessed on 29 November 2025).

- McAuliffe, M.; Socolof, M.; Mihuc, S.; Wagner, M.; Sonderegger, M. Montreal forced aligner: Trainable text-speech alignment using kaldi. In Proceedings of the Interspeech, Stockholm, Sweden, 20–24 August 2017; Volume 2017, pp. 498–502. [Google Scholar]

- Kingma, D.P.; Ba, J. Adam: A Method for Stochastic Optimization. arXiv 2014, arXiv:1412.6980. [Google Scholar]

- Kalchbrenner, N.; Elsen, E.; Simonyan, K.; Noury, S.; Casagrande, N.; Lockhart, E.; Stimberg, F.; Oord, A.; Dieleman, S.; Kavukcuoglu, K. Efficient neural audio synthesis. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning, PMLR, Stockholm, Sweden, 10–15 July 2018; pp. 2410–2419. [Google Scholar]

- Griffin, D.; Lim, J. Signal estimation from modified short-time Fourier transform. IEEE Trans. Acoust. Speech Signal Process. 1984, 32, 236–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, J.; Kim, J.; Bae, J. HiFi-GAN: Generative Adversarial Networks for Efficient and High Fidelity Speech Synthesis. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2010.05646. [Google Scholar]

| Model’s Name | Component’s Name | Description of Parameter | Value of Parameter |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acoustic | Encoder/Decoder | Number of FFT blocks | 6 |

| Number of filters in the FFT’s 1D Convolution | 1536 | ||

| Duration predictor | Number of convolutional layers | 4 | |

| GST | Number of tokens | 32 | |

| Reference encoder | Number of blocks | 5 | |

| Number of filters in the FFT’s 1D Convolution | 384 | ||

| Global | Dropout rate | 0.1 | |

| Hidden dimension | 384 | ||

| Number of heads in FFT’s multi-head attention | 4 | ||

| Non-det. GST Predictor | Encoder | Number of blocks | 16 |

| Number of heads in FFT’s multi-head attention | 4 | ||

| Number of filters in the FFT’s 1D Convolution | 1536 | ||

| Dropout rate | 0.1 | ||

| Decoder | Number of blocks | 10 | |

| Number of 1D convolution channels | 128 | ||

| Timestep embedding size | 128 | ||

| Diffusion | Number of steps | 1000 | |

| Diffusion schedule | Linear [, ] | ||

| Det. GST Predictor | - | Number of blocks | 2 |

| Dropout rate | 0.2 | ||

| Hidden dimension | 768 | ||

| Number heads in multi-head attention | 16 | ||

| Number of filters in the FFT’s 1D Convolution | 1536 |

| Sample ID | Textual Content |

|---|---|

| LJ005-0008 | They were followed by a crowd of reckless boys, who jeered at and insulted them. |

| LJ008-0184 | Precautions had been taken by the erection of barriers, and the posting of placards at all the avenues to the Old Bailey, on which was printed. |

| LJ011-0095 | He had prospered in early life, was a slop-seller on a large scale at Bury St. Edmunds, and a sugar-baker in the metropolis. |

| LJ015-0009 | Cole’s difficulties increased more and more; warrant-holders came down upon him demanding to realize their goods. |

| LJ048-0261 | Employees are strictly enjoined to refrain from the use of intoxicating liquor. |

| LJ050-0254 | The Secret Service in the past has sometimes guarded its right to be acknowledged as the sole protector of the Chief Executive. |

| System | F0 RMSE ↓ | F0 Pearson ↑ | MCD ↓ | Duration MRE ↓ |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GT Vocoder | 55.81 | 0.85 | 3.02 | 0.0202 |

| Proposed Vanilla | 110.83 | 0.476 | 6.62 | 0.1565 |

| Proposed = 0.2 | 108.69 | 0.484 | 6.63 | 0.1517 |

| Proposed = 0.4 | 106.10 | 0.505 | 6.60 | 0.1574 |

| Proposed = 0.6 | 108.65 | 0.488 | 6.52 | 0.1566 |

| Proposed = 0.8 | 107.52 | 0.497 | 6.50 | 0.1609 |

| Proposed = 1.0 | 108.54 | 0.490 | 6.54 | 0.1642 |

| Tacotron2 + WaveRNN | 106.49 | 0.496 | 7.22 | 0.1520 |

| Tacotron2 + Griffin-Lim | 108.56 | 0.477 | 27.24 | 0.1585 |

| System | F0 | Word Duration |

|---|---|---|

| Proposed | 58.07 | 0.0145 |

| Proposed | 52.82 | 0.0133 |

| Proposed | 49.31 | 0.0112 |

| Proposed | 42.27 | 0.0094 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Prosowicz, W.; Hachaj, T. Using Denoising Diffusion Model for Predicting Global Style Tokens in an Expressive Text-to-Speech System. Electronics 2025, 14, 4759. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14234759

Prosowicz W, Hachaj T. Using Denoising Diffusion Model for Predicting Global Style Tokens in an Expressive Text-to-Speech System. Electronics. 2025; 14(23):4759. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14234759

Chicago/Turabian StyleProsowicz, Wiktor, and Tomasz Hachaj. 2025. "Using Denoising Diffusion Model for Predicting Global Style Tokens in an Expressive Text-to-Speech System" Electronics 14, no. 23: 4759. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14234759

APA StyleProsowicz, W., & Hachaj, T. (2025). Using Denoising Diffusion Model for Predicting Global Style Tokens in an Expressive Text-to-Speech System. Electronics, 14(23), 4759. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14234759