FDTD Simulation on Signal Propagation and Induced Voltage of UHF Self-Sensing Shielding Ring for Partial Discharge Detection in GIS

Abstract

1. Introduction

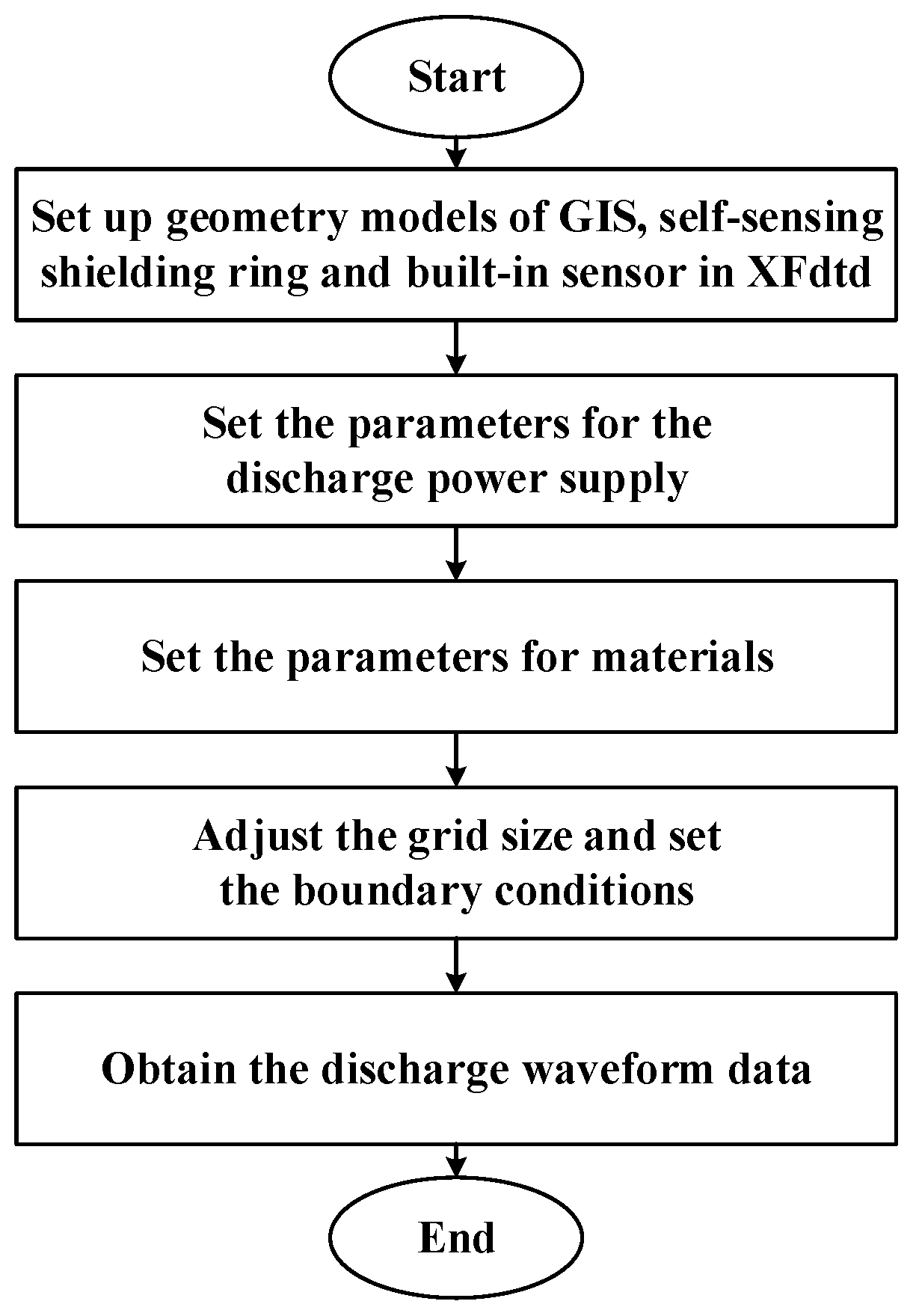

2. Simulation Principle of Partial Discharge in GIS

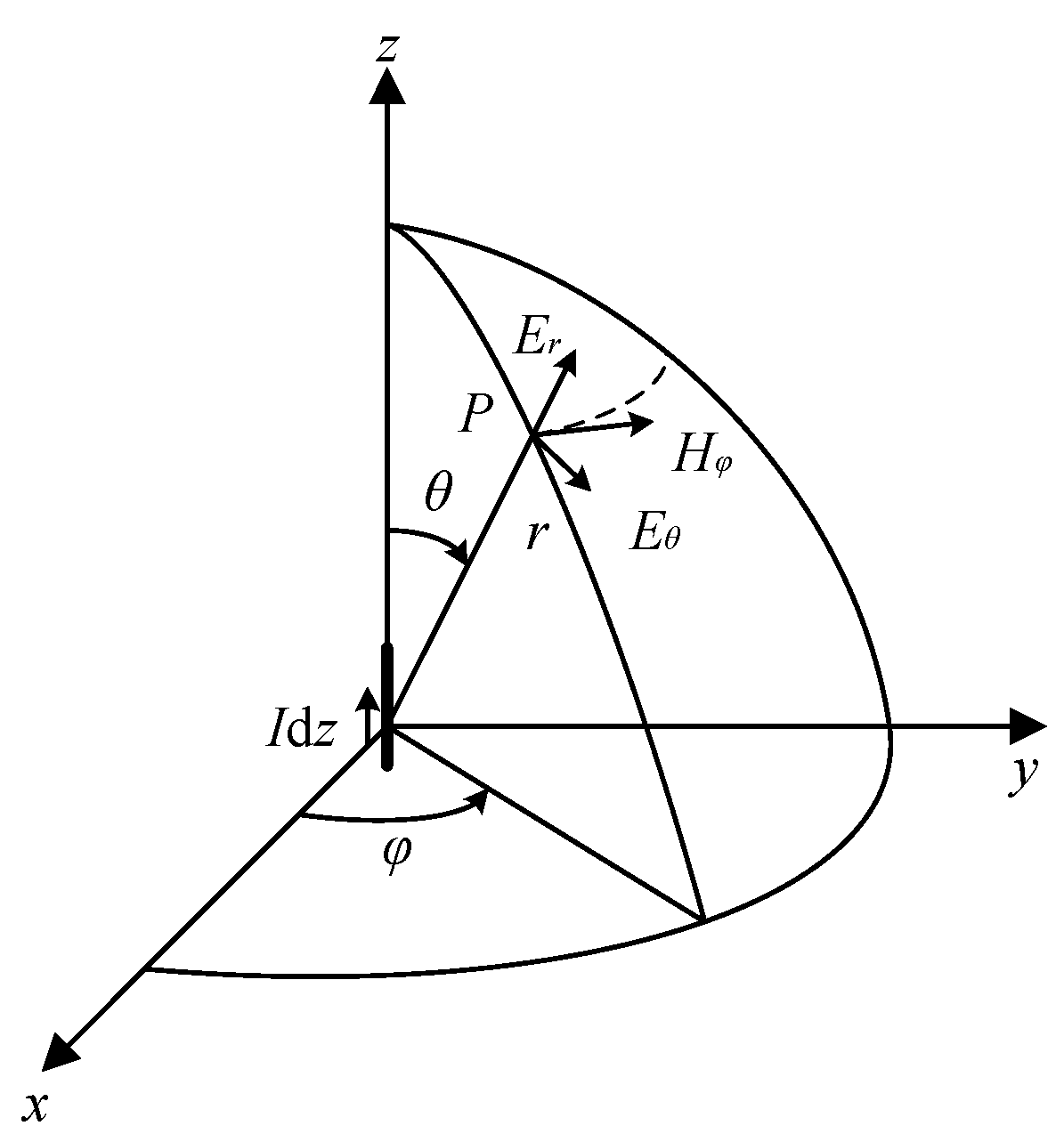

2.1. Principle of Partial Discharge Radiation

2.2. Interface Connection Conditions

2.3. Establishment of the Self-Sensing Shielding Ring Simulation Model

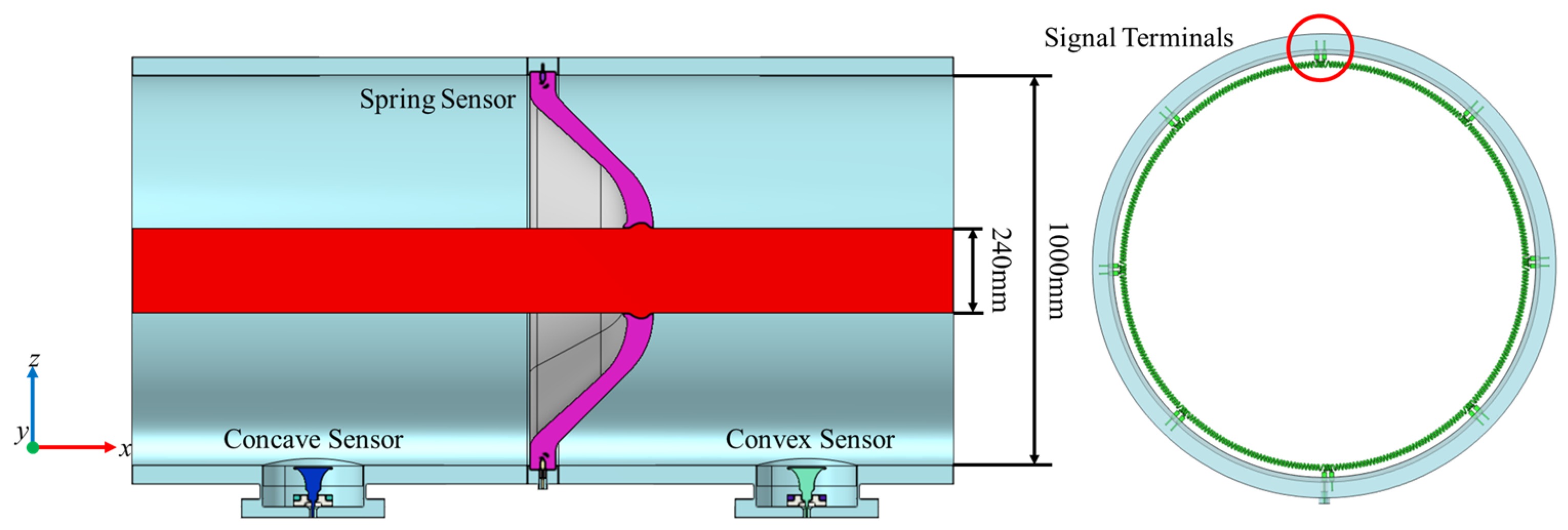

2.3.1. Establishment of the Model

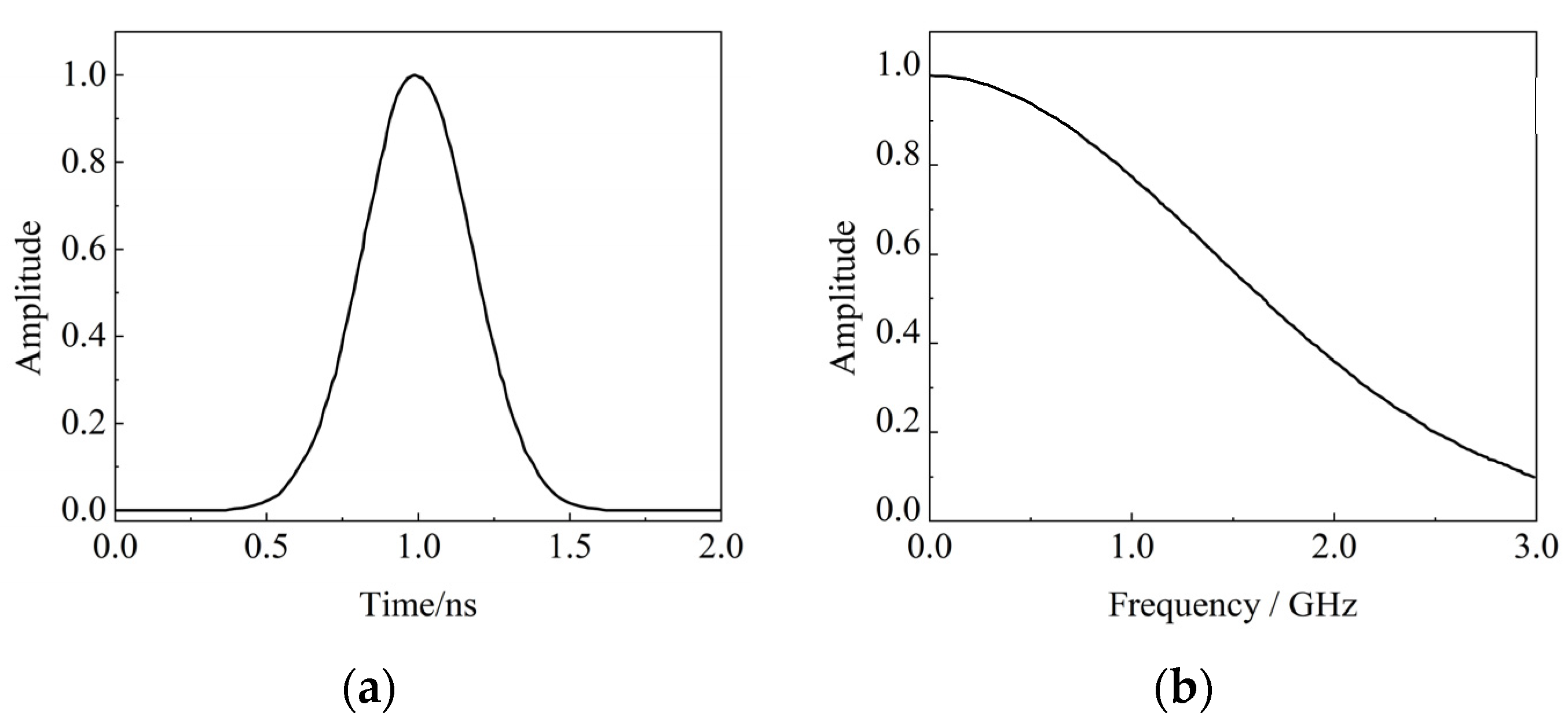

2.3.2. Settings of the Power Supply

2.3.3. Material Settings

2.3.4. Grid Size Subdivision

2.3.5. Boundary Condition Settings

3. Results and Analysis of the Propagation Characteristics Simulation

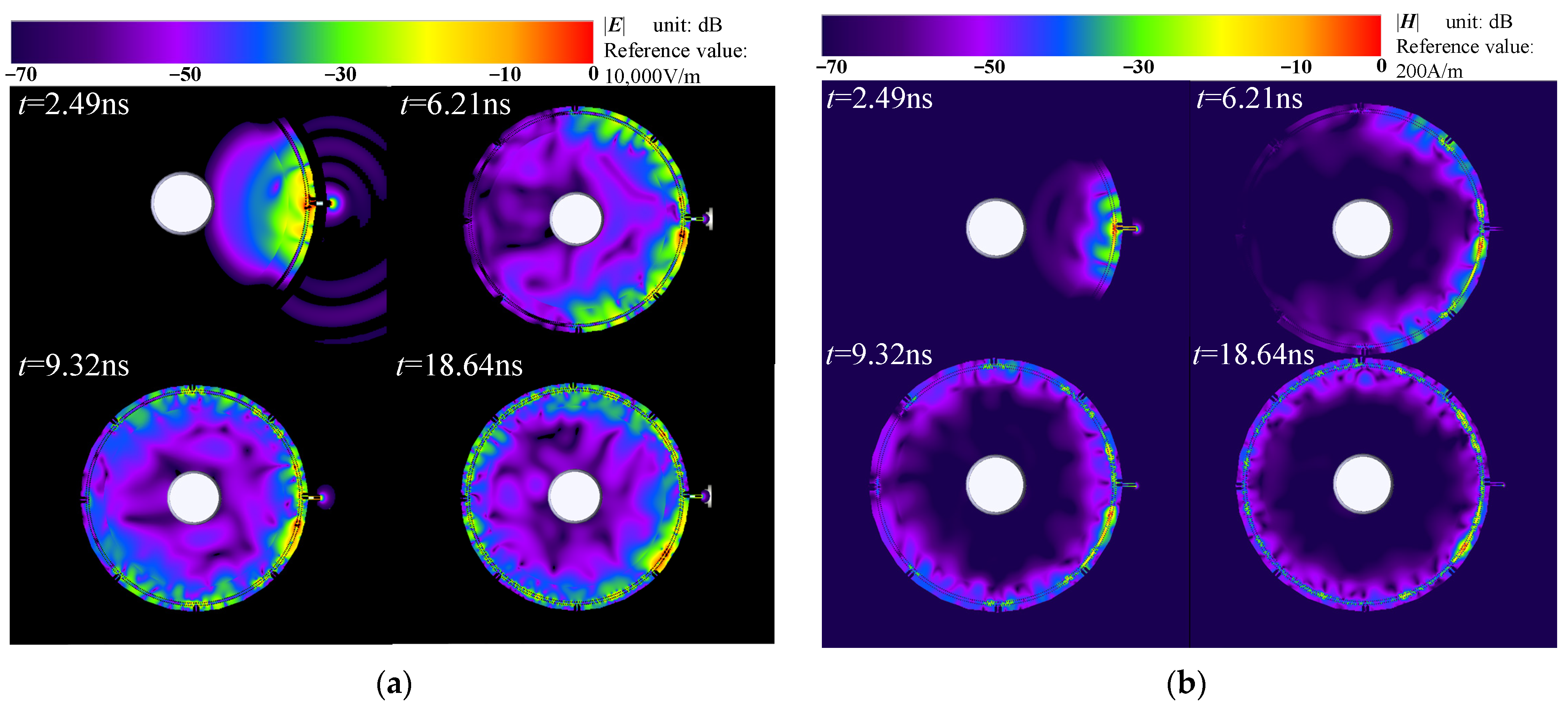

3.1. Propagation Characteristics of Electromagnetic Waves in the Self-Sensing Shielding Ring

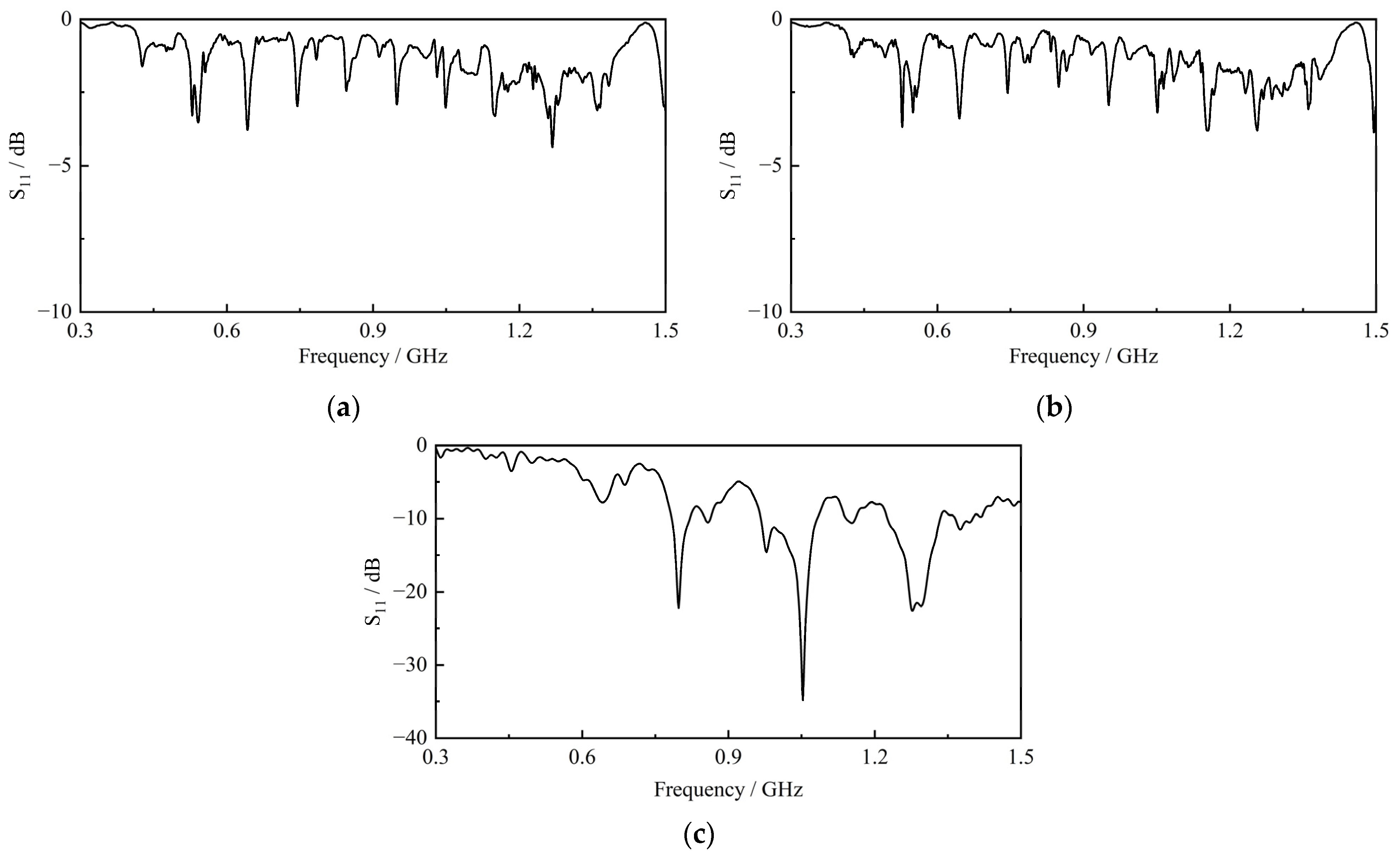

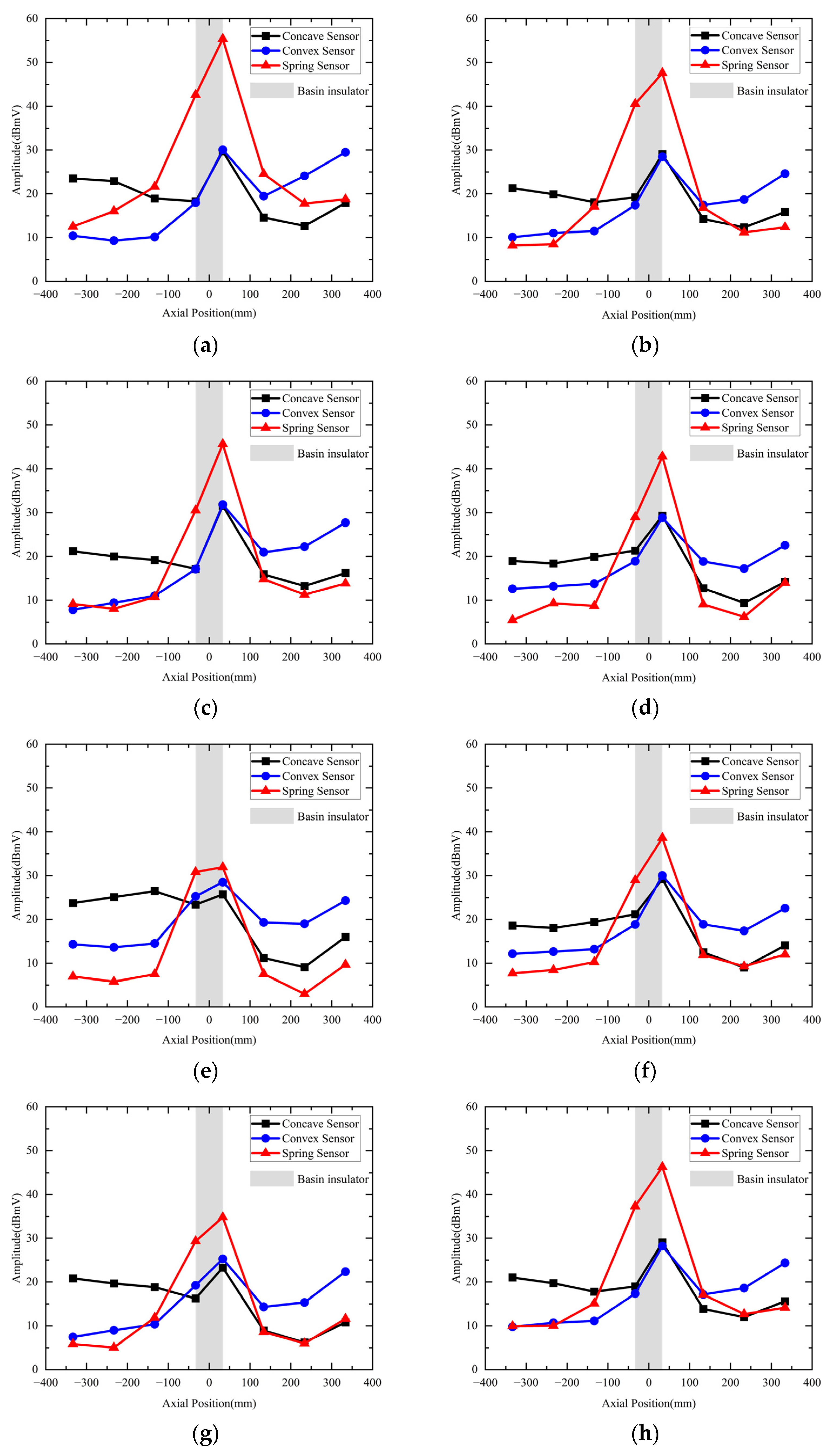

3.2. S11 Simulation Results and Analysis

- (1)

- Average S11

- (2)

- Return loss

4. Analysis of Influencing Factors on the Receiving Characteristics of Self-Sensing Shielding Rings

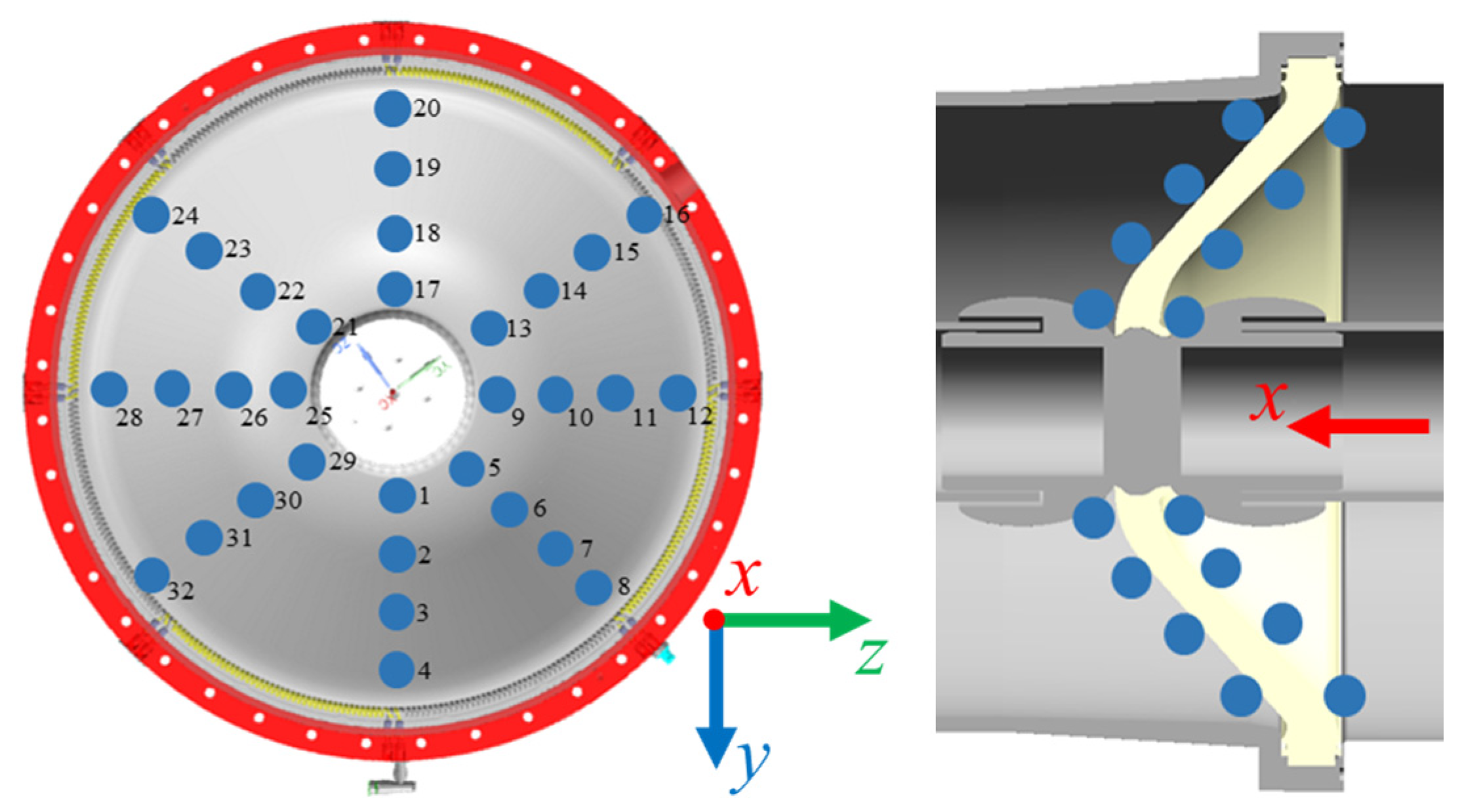

4.1. Array Simulation of Partial Discharge in Self-Sensing Shielding Ring

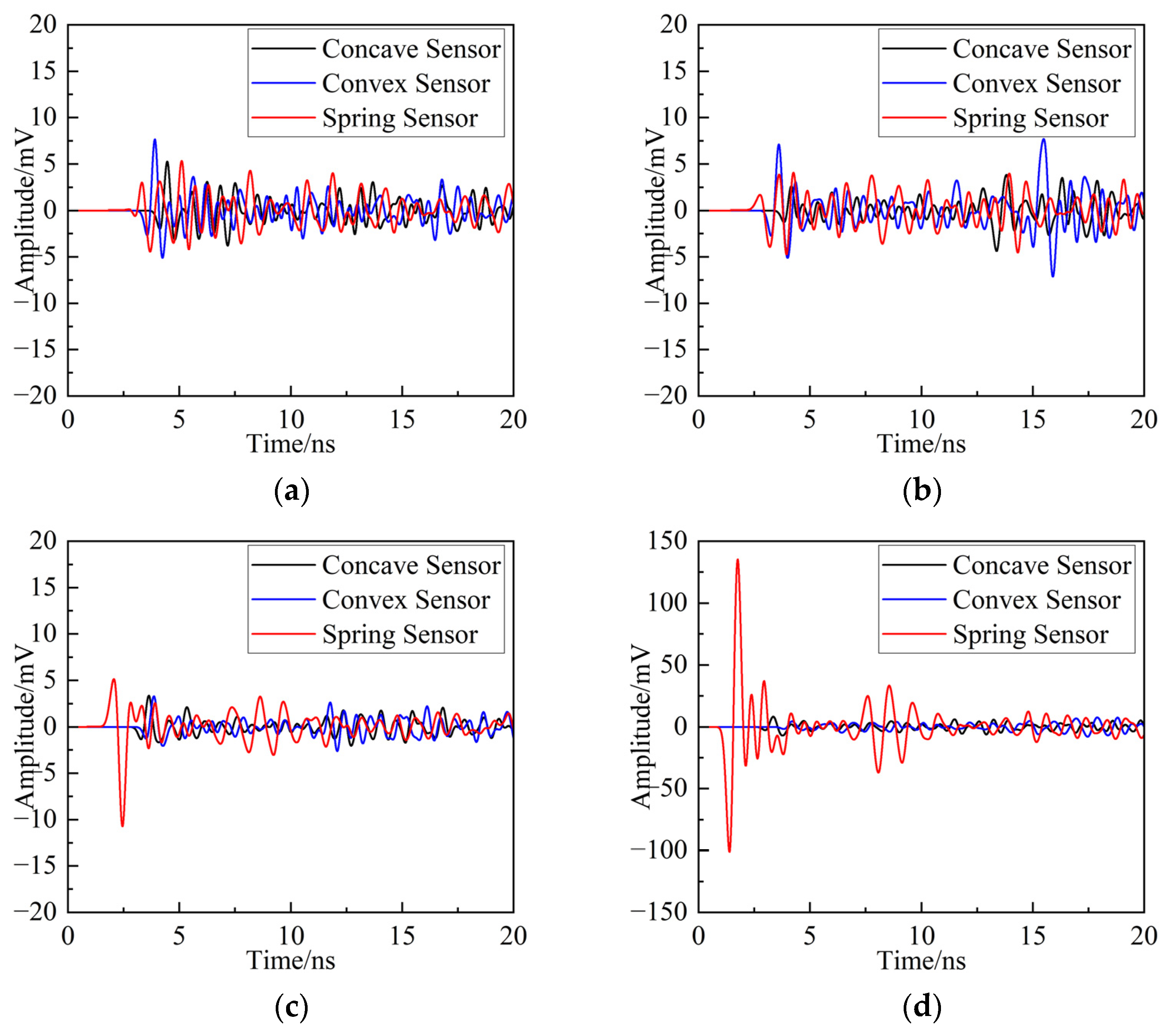

4.2. Influence of Radial Position on Detection Sensitivity

4.3. Influence of Angle Position on Detection Sensitivity

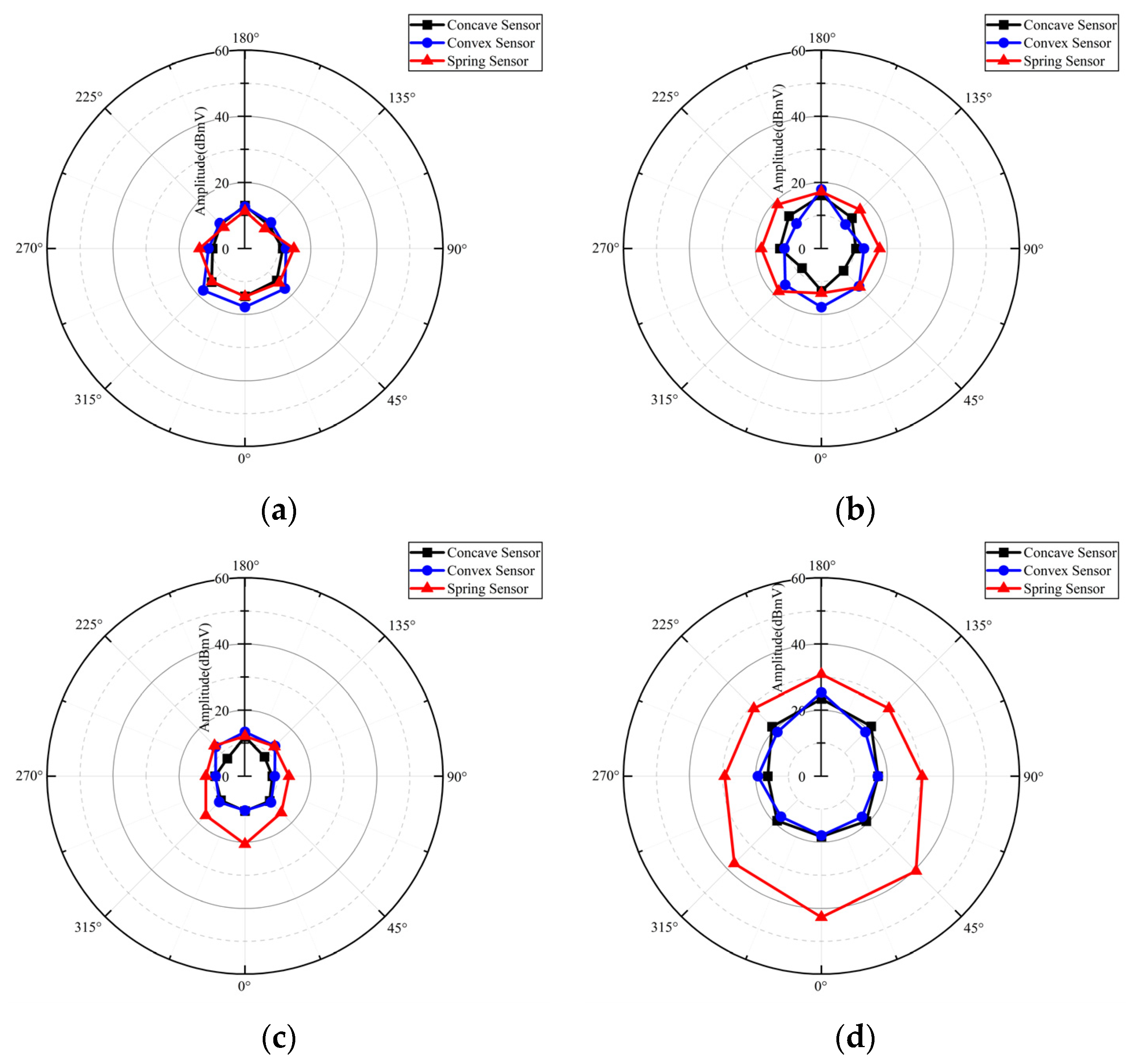

4.4. Influence of Axial Position on Detection Sensitivity

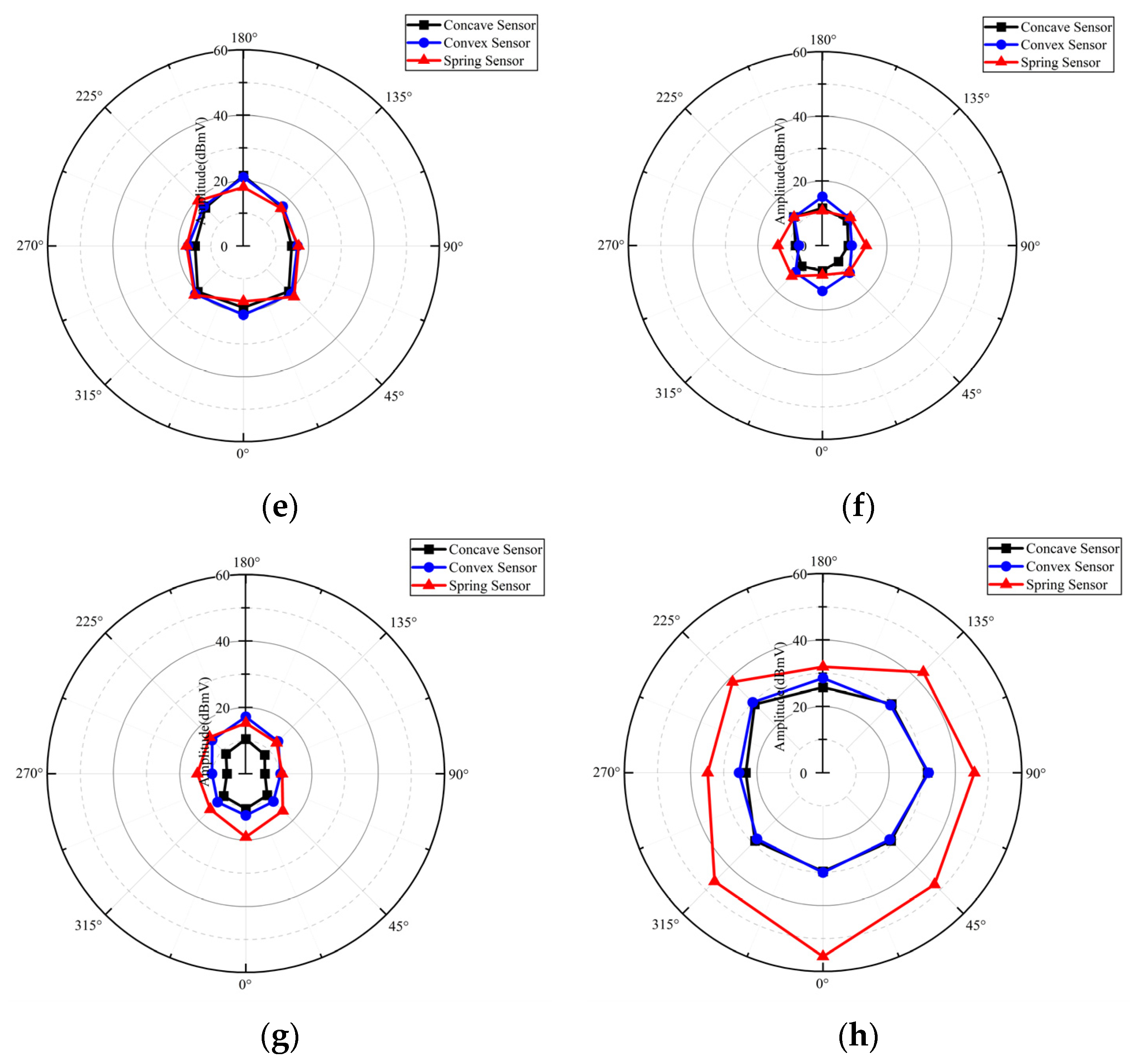

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| FDTD | Finite-difference time-domain |

| UHF | Ultra-high frequency |

| GIS | Gas-insulated switchgear |

| PD | Partial discharge |

| PTFE | Polytetrafluoroethylene |

| PEC | Perfect electric conductors |

| CFL | Courant–Friedrichs–Lewy |

| PML | Perfectly matched layers |

| VNA | Vector network analyzer |

References

- Gao, W.; Ding, D.; Liu, W. Research on the Typical Partial Discharge Using the UHF Detection Method for GIS. IEEE Trans. Power Deliv. 2011, 26, 2621–2629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Judd, M.D.; Farish, O.; Hampton, B. The excitation of UHF signals by partial discharges in GIS. IEEE Trans. Dielectr. Electr. Insul. 2002, 3, 213–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Rong, M.; Zheng, C.; Wang, X. Development simulation and experiment study on UHF Partial Discharge Sensor in GIS. IEEE Trans. Dielectr. Electr. Insul. 2012, 19, 1421–1430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Han, X.; Liu, Z.; Yao, X. A Novel GIS Partial Discharge Detection Sensor with Integrated Optical and UHF Methods. IEEE Trans. Power Deliv. 2016, 33, 2047–2049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roslizan, N.D.; Rohani, M.N.; Wooi, C.L.; Isa, M.; Ismail, B.; Rosmi, A.S.; Mustafa, W.A. A review: Partial discharge detection using UHF sensor on high voltage equipment. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2020, 1432, 012003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bin, F.; Wang, F.; Sun, Q.; Lin, S.; Xie, Y.; Fan, M. Internal UHF antenna for partial discharge detection in GIS. IET Microw. Antennas Propag. 2018, 12, 2184–2190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faizol, Z.; Zubir, F.; Saman, N.M.; Ahmad, M.H.; Rahim, M.K.A.; Ayop, O.; Jusoh, M.; Majid, H.A.; Yusoff, Z. Detection Method of Partial Discharge on Transformer and Gas-Insulated Switchgear: A Review. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 9605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, V.M.; Abdul-Malek, Z.; Muhamad, N.A. Status Review on Gas Insulated Switchgear Partial Discharge Diagnostic Technique for Preventive Maintenance. Indones. J. Electr. Eng. Comput. Sci. 2017, 7, 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, X.; Song, H.; Dai, J.; Luo, L.; Sheng, G.; Jiang, X. Severity Evaluation of UHF Signals of Partial Discharge in GIS Based on Semantic Analysis. IEEE Trans. Power Deliv. 2021, 37, 1456–1464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, H.; Phung, B.; Mitchell, S. Application of UHF Sensors in Power System Equipment for Partial Discharge Detection: A Review. Sensors 2019, 19, 1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, R.; Wu, S.; Chi, P.; Peng, N.; Li, Y. Optimal Placement of UHF Sensors for Accurate Location of Partial Discharge in Gas-Insulated Switchgear. Energies 2019, 12, 1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, J.; Zhang, G.; Ming, C.; He, L.; Liu, Y.; Liu, J.; Zhang, X. Design of a Flexible UHF Hilbert Antenna for Partial Discharge Detection in Gas-Insulated Switchgear. IEEE Antennas Wirel. Propag. Lett. 2022, 22, 794–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Zhang, G.; Liu, X.; Chen, K.; Zhang, X. Design of High-Sensitivity Flexible Low-Profile Spiral Antenna Sensor for GIS Built-in PD Detection. Sensors 2023, 23, 4722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jia, Y.; Yang, J.; Rong, L.; Tao, F. Performance Comparison of Typical Built-In UHF Sensors Used for GIS PD Detection. Appl. Mech. Mater. 2014, 672–674, 1143–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hikita, M.; Ohtsuka, S.; Teshima, T.; Okabe, S.; Kaneko, S. Electromagnetic (EM) wave characteristics in GIS and measuring the EM wave leakage at the spacer aperture for partial discharge diagnosis. IEEE Trans. Dielectr. Electr. Insul. 2007, 14, 453–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, G.M.; Li, C.R.; Chen, W.J.; Zhang, B.; Li, Z.B. VFTO Measurement System Based on the Embedded Electrode in GIS Spacer. IEEE Trans. Power Deliv. 2012, 27, 1998–2003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoshino, T.; Maruyama, S.; Sakakibara, T.; Ohtsuka, S.; Hikita, M.; Ueta, G.; Okabe, S. Sensitivity of UHF coupler and loop electrode with UHF method and their comparison for detecting partial discharge in GIS. In Proceedings of the 2008 International Conference on Condition Monitoring and Diagnosis, Beijing, China, 21–24 April 2008; IEEE: New York, NY, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Shuheng, D.; Na, W.; Haodong, L.; Teng, J. Optimization Design of Grading Ring for 220 kV Basin type Insulator Based on Finite Element Method and Neural Network Method. Insul. Surge Arresters 2018, 54, 79–85. [Google Scholar]

- Ye, H.; Man, Y.; Qian, Y.; Cao, L.; Sheng, G.; Jiang, X. Simulation study of attenuation of ultrahigh frequency electromagnetic wave by salver-shaped insulator in GIS. Przegląd Elektrotechniczny 2013, 89, 122–125. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Wang, X.; Yang, A.; Rong, M. Partial discharge source localization in GIS based on image edge detection and support vector machine. IEEE Trans. Power Deliv. 2019, 34, 1795–1802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Wang, X.; Zheng, C.; Liu, D.; Rong, M. Investigation on the placement effect of UHF sensor and propagation characteristics of PD-induced electromagnetic wave in GIS based on FDTD method. IEEE Trans. Dielectr. Electr. Insul. 2014, 21, 1015–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, R.; Zhang, Y.; Si, G.; Wu, C.; Yang, N.; Wang, Y. Simulation analysis on the propagation characteristics of electromagnetic wave in T-branch GIS based on FDTD. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE 15th Mediterranean Microwave Symposium (MMS), Lecce, Italy, 30 November–2 December 2015; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, G.; Tian, J.; Zhang, X.; Liu, J.; Lu, C. A flexible planarized biconical antenna for partial discharge detection in gas-insulated switchgear. IEEE Antennas Wirel. Propag. Lett. 2022, 21, 2432–2436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salah, W.S.; Gad, A.H.; Attia, M.A.; Eldebeikey, S.M.; Salama, A.R. Design of a compact ultra-high frequency antenna for partial discharge detection in oil immersed power transformers. Ain Shams Eng. J. 2022, 13, 101568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Evaluation Index | Concave Sensor | Convex Sensor | Spring Sensor |

|---|---|---|---|

| Average S11 (dB) | −1.270 | −1.274 | −6.347 |

| Average RL (dB) | 1.270 | 1.274 | 6.347 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Li, R.; Wang, S.; Zhang, W.; Liu, H.; Li, L.; Yuan, S.; Wang, D.; Zhang, G. FDTD Simulation on Signal Propagation and Induced Voltage of UHF Self-Sensing Shielding Ring for Partial Discharge Detection in GIS. Electronics 2025, 14, 4757. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14234757

Li R, Wang S, Zhang W, Liu H, Li L, Yuan S, Wang D, Zhang G. FDTD Simulation on Signal Propagation and Induced Voltage of UHF Self-Sensing Shielding Ring for Partial Discharge Detection in GIS. Electronics. 2025; 14(23):4757. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14234757

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Ruipeng, Siqing Wang, Wei Zhang, Huiwu Liu, Longxing Li, Shurong Yuan, Dong Wang, and Guanjun Zhang. 2025. "FDTD Simulation on Signal Propagation and Induced Voltage of UHF Self-Sensing Shielding Ring for Partial Discharge Detection in GIS" Electronics 14, no. 23: 4757. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14234757

APA StyleLi, R., Wang, S., Zhang, W., Liu, H., Li, L., Yuan, S., Wang, D., & Zhang, G. (2025). FDTD Simulation on Signal Propagation and Induced Voltage of UHF Self-Sensing Shielding Ring for Partial Discharge Detection in GIS. Electronics, 14(23), 4757. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14234757