1. Introduction

Throughout the evolution of modern automation, Takagi–Sugeno (T-S) fuzzy systems [

1] have emerged as powerful tools for modeling complex nonlinear dynamics. By employing the set of “IF-THEN” laws, T-S fuzzy models integrate local linear models with membership functions to accurately approximate nonlinear dynamics. With the advent of these models and modern control strategies, significant progress has been made in research, resulting in valuable contributions to stability analysis, stabilization, and adaptive/

control [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6]. However, practical dynamical systems frequently exhibit temporal parameter variations stemming from probabilistic factors such as component malfunctions, maintenance interventions, structural reconfigurations, and environmental perturbations. Such systems, known as Markov jump systems (MJSs), have attracted substantial research interest [

7,

8,

9,

10,

11]. For example, the asynchronous control problem for discrete-time MJSs was investigated in [

12]; fuzzy optimal control for singularly perturbed MJSs was addressed in [

13]; and a reinforcement learning method was proposed in [

14] to tackle the

control problem of discrete-time T-S fuzzy MJSs. Consequently, the investigation and synthesis of control strategies for T-S fuzzy systems incorporating Markov jump parameters remains a critical research frontier, particularly when the transition rates (TRs) of the Markov process, which play a key role in the system’s dynamic behavior, are uncertain.

Within the field of control methodologies, sliding mode control (SMC) [

15] has gained prominence as a widely recognized and effective approach for handling nonlinear dynamics. Owing to its inherent advantages—including rapid convergence, superior dynamic characteristics, and exceptional resilience against exogenous disturbances and parametric uncertainties—this technique has been extensively adopted in operational environments. Recent advances demonstrate innovative implementations of T-S fuzzy sliding mode controllers across theoretical frameworks and industrial domains. For example, ref. [

16] developed a disturbance-resilient fault-tolerant SMC framework for T-S fuzzy architectures; Ref. [

17] proposed a novel fuzzy-integrated SMC law addressing stability preservation in wind-integrated multi-regional power grids with stochastic delays; and ref. [

18] conducted theoretical explorations on interval type-2 fuzzy systems through enhanced sliding manifold constructions. Additionally, the fault-tolerant control via SMC approach was proposed to deal with T-S fuzzy systems in [

19]. For more details, see [

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26] and the references therein, where T-S fuzzy models are combined with sliding manifolds to cope with complex nonlinear behaviors. However, most of these fuzzy SMC designs either assume full state availability and directly measurable premise variables, or impose restrictive structural conditions on the input matrices, such as rule-independent or full-column-rank configurations, which limits their applicability when only partial state information is available and mode-dependent actuators are involved. In addition, observer-based fuzzy control and event-triggered mechanisms have recently been combined in an observer-regulated adaptive fuzzy funnel framework for switched nonlinear systems, which is closely related to the present topic but is developed for deterministic switched systems without Markov jump parameters and does not explicitly address unmeasurable premise variables or generally uncertain transition rates. It explicitly states that the outstanding technical obstacles in the cited SMC works on T-S fuzzy MJSs are premise-variable unobservability combined with uncertain TRs, restrictive input-matrix assumptions that limit the class of fuzzy MJSs that can be treated, and the lack of a mechanism to deal with unknown nonlinearities without conservative switching gains under partial state information. Consequently, the synthesis of practical sliding mode observers necessitates explicit incorporation of fuzzy observer premise variables that are mathematically derived from reconstructed state estimations. The current literature remains notably sparse regarding observer-driven SMC implementations within T-S fuzzy MJSs. A seminal contribution by [

27] introduced an observer-regulated adaptive SMC mechanism for stochastic fuzzy architectures operating under fractional Brownian motion disturbances and uncertain TRs. On the other hand, the traditional SMC method performs well in handling nonlinear disturbances with known boundaries but faces challenges when the nonlinearity is uncertain and the system state components are simultaneously unavailable. These challenges motivate our research.

In addition, event-triggered control (ETC) [

28] has recently emerged as a popular topic due to its ability to enhance network efficiency. Recent work in ETC includes ref. [

29], which developed an innovative data-centric event-triggered regulation architecture for nonlinear dynamical systems operating in continuous-time domains with unidentified parameters, and ref. [

30], which analyzed the stability of complex networks using asynchronous dynamic ETC. Ref. [

31] investigated an ETC architecture with temporal convergence guarantees for dynamical systems exhibiting nonlinearities and parametric uncertainties, utilizing time-constrained stabilization strategies. Dynamic event-triggered and adaptive fuzzy control strategies have also been proposed to improve transient performance and reduce resource usage in nonlinear systems (see [

32,

33,

34,

35]). These contributions clearly show the advantages of dynamic triggering over static ETC, yet they are mainly formulated for deterministic or switched nonlinear systems without Markov jump parameters and typically rely on fully measurable state or premise variables. In contrast, designing a dynamic ETC mechanism for observer-based fuzzy SMC in T-S fuzzy MJSs—where premise variables are unmeasurable, only output measurements are available, and the TRs are generally uncertain—remains largely unexplored and constitutes a central motivation of this paper.

Based on the above analysis, this paper investigates observer-driven event-triggered SMC for continuous-time nonlinear T-S fuzzy MJSs with inaccessible scheduling parameters. An integral sliding hyperplane incorporating reconfigured input matrices is developed to enhance compatibility with fuzzy model dynamics. Furthermore, computationally efficient LMI criteria are established to guarantee stochastic stabilization of the system under uncertainties in TRs. Our work therefore contrasts with recent dynamic event-triggered fuzzy control schemes, which typically address interval type-2 or T-S fuzzy systems with directly measurable premise variables and focus on controller-side triggering for state-feedback or output-feedback designs. The principal innovations of this work are threefold: (1) A dynamic ETC mechanism is developed for observer-dependent fuzzy SMC in T-S MJSs with unmeasurable premise parameters. Different from existing dynamic ETMs for fuzzy systems, which are usually designed for systems with fully available premise variables and without Markov jump parameters, the proposed ETM is embedded into the observer error dynamics and explicitly accounts for both TR uncertainty and premise mismatch. Meanwhile, the proposed approach demonstrates a improvement in network efficiency compared to existing static ETC methods. (2) By transforming input matrices and using an integral sliding hyperplane, we derive sliding mode dynamics with desirable properties and establish feasible stability conditions under generally uncertain TR mode information. This relaxes the structural constraints imposed in many existing fuzzy SMC designs for MJSs and allows uncertain TRs to be treated in a general way through Markovian coupling terms in the LMIs, thereby broadening the applicability of sliding mode-based fuzzy control to systems with heterogeneous actuator structures. (3) A fuzzy SMC strategy integrated with an observer-based neural compensator is synthesized to ensure sliding surface reachability within a finite time interval and to maintain consistent sliding motion behavior. In contrast with event-triggered fuzzy SMC schemes where neural approximators are attached directly to plant states or require measurable premise variables, the proposed compensator is driven by observer states and explicitly participates in both the sliding surface and triggering conditions. This design enables attenuation of unknown nonlinearities while preserving the stochastic robustness of the coupled observer/controller chain and leads to improved transient performance relative to traditional SMC methods.

Notation 1. Throughout this study, denotes a probability space, and represents the expectation with respect to . In symmetric matrices, symmetric elements are denoted by . denotes .

2. Problem Statement and Preliminaries

Consider a continuous-time Markov chain

defined over the finite state space

, whose transition dynamics are characterized by

where

h is a positive scalar satisfying the asymptotic condition

. The TR matrix possesses positive entries

for distinct modes

, while its diagonal elements are defined as

to adhere to conservation principles for all

.

The T-S fuzzy MJSs are formulated through the following rule structure:

Plant rule

i: If

is

,

is

, ⋯,

is

, then

where the state vector

, with

, …,

as the scheduling parameters. The notation

(where

characterizes the linguistic properties of the input states. Additionally, the control input is

, while the controlled output is

;

,

and

are mode-dependent matrices. Furthermore, the pair

is controllable. An uncertain nonlinear functional component described by

is norm-bounded.

Adopting the fuzzy blending approach outlined in [

2], the overall fuzzy system is derived as

The activation degree of fuzzy rule

i is determined by the normalized membership grade

, mathematically formulated as

where

characterizes the membership grade of

associated with the linguistic term

. These functions satisfy the convexity constraints

with

for

. For calculation simplicity,

is denoted as

m in the following parts.

Assumption 1. The fuzzy rule base and membership functions of the plant are completely known, and the observer employs the same membership functions and local matrices , , and as those appearing in (1). Consequently, the premise variables are not directly measured but are reconstructed from the estimated state through the same fuzzy partition, while modeling errors in and , , are not explicitly considered in the present formulation.

Remark 1. Assumption 1 is consistent with most observer-based fuzzy control designs, where a T-S fuzzy model is identified or derived offline and then used as a nominal description for controller and observer synthesis. Within our framework, the uncertainties explicitly addressed by the sliding mode and neural network compensator are encapsulated in the norm-bounded nonlinear term , and the stochastic parametric variations are captured by the uncertain Markov TRs. Under Assumption 1, the only mismatch between the true premise variables and their observer counterparts comes from the state-estimation error and is rigorously modeled by the perturbation term in (9), which is handled via the performance index and -gain inequality established in Theorem 1. Extending the proposed approach to explicitly accommodate structural uncertainty in the membership functions or in the estimator model would require additional adaptive or robust identification mechanisms and is therefore left as an interesting direction for future research.

To construct a networked observer structure for system (

1), an event-triggered mechanism is implemented. The output measurements are processed by an event detector that selectively authorizes data packet transmission through the communication link. Specifically, utilizing real-time output measurements

, the transmitted data is represented as

, where

indicates the transmission instant. Then, the triggering criterion governing data packet release is activated when the discrepancy between

and

satisfies predefined thresholds:

where

operates within the interval

,

,

, and matrix

. The auxiliary variable

is governed by

with initial constraints

and

; the subsequent triggering instants

of the event detector are iteratively computed through the following temporal evolution law, activated following the successful release of

:

Lemma 1 ([

36]).

Given that the ETM law (5) and the interval variable is defined in (4), it holds that for the non-triggering moment. Proof. During the non-triggering interval, it follows from (

3) and (

4) that

In view of the initial condition

, it derives from the above formula that

This completes the proof. □

The networked communication channel forwards data packets to the state estimator in the form of

The proposed state observer is designed using the measurement signal , which is constructed based on the following dynamic equations:

Observer criterion

i: If

is

,

is

, ⋯, and

is

, then

where

and

are the estimates of

and

, respectively. The compensator

serves to counteract effects of the uncertain nonlinearity

, while

denotes observer gain matrix to be synthesized subsequently.

The composite fuzzy observer dynamics are consequently derived through weighted aggregation:

The state estimation discrepancy is introduced as

. By synthesizing Equations (

2) and (

8), the error dynamic behavior is characterized through the following differential relationship:

where

characterizes a perturbation.

Remark 2. In our formulation, the influence of unmeasurable premise variables enters the closed-loop dynamics only through the perturbation term in the observation error system (9), where the mismatch between the true premise variables and their estimates are explicitly collected. Because all membership functions are normalized and satisfy and , the premise-estimation error is automatically bounded in the sense that and for all . Combining this structural property with the definition of yields the quantitative bound , which shows that the perturbation induced by unmeasurable premise variables cannot grow unboundedly but is uniformly bounded by the system and controller matrices and by the bounded closed-loop signals . So, for the composite observer/controller chain, this means that the closed-loop system remains stochastically stable for any premise-estimation error that generates an energy-bounded perturbation .

Prior to the subsequent development, it is noteworthy that conventional methodologies predominantly impose restrictive requirements on input matrices, either demanding rule independence or full column rank properties. Departing from these limitations, this work introduces a generalized formulation where the composite input matrix is constructed as

. Auxiliary matrices are subsequently defined as

Then, the following holds:

Consequently, the observer dynamics corresponding to (

8) are formulated by the expression

where

, meeting

.

From a generalized perspective, the matrix

may be constructed as a subharmonic aggregation of subsystem matrices

, expressed by

, with

and

. However, when the input matrices are identical across all subsystems, i.e.,

, this configuration results in

, leading to

. Such cases have been thoroughly examined in prior research endeavors. The proposed framework significantly extends conventional approaches by eliminating restrictive assumptions regarding rule independence or full column rank requirements for

. For computational purposes, let

, then the observer fuzzy system (

8) is rewritten as

Definition 1 ([

37]).

The unforced open-loop system (

1)

is stochastically stable for any arbitrary initial conditions and , provided that the following inequality condition is satisfied. Lemma 2 ([

38]).

For any positive-definite matrix , the subsequent inequality meets , given a positive scalar ϵ and a matrix R. Additionally, it holds for any vectors and positive-definite matrix that . In summary, the purpose of this paper is to design a dynamic ETC mechanism-based state observer for nonlinear fuzzy MJSs, which is then utilized to develop a neural network-based compensator for the SMC law. The ultimate objectives are to ensure stochastic stability with an performance of the sliding motion in the presence of uncertain TRs, and to improve the network utilization efficiency.

4. Simulation Example

Consider a robotic manipulator model referenced in [

39], governed by the dynamical equation

where

corresponds to the arm’s angular displacement, with

signifying the applied control torque. System parameters comprise payload mass

M, rotational inertia

J, gravitational acceleration

g, arm length

L, and time-dependent viscous damping coefficient

. The gravitational acceleration and arm length are fixed at

and

, respectively. The viscous damping coefficient

is defined as a time-invariant parameter with a constant value of

. Furthermore, the payload mass

M and rotational inertia

J operate under three distinct configurations, as tabulated in

Table 1. The TR matrix governing mode switching is structured as

Define

and

. In accordance with [

34], the nonlinear function

is represented as

where

, with membership grades

and

satisfying the convex constraint

equal to 1. Through analytical derivation of the governing equations, the fuzzy weighting functions are obtained as

According the proposed membership grades, it is clear that if is approximately 0 rad, the corresponding values are and equal to 1 and , which are equal to 0. Conversely, if is around rad or rad, we get , which is equal to 0, and , which is equal to 1. Incorporating nonlinear uncertainties, the robotic arm’s dynamics are formulated as a dual-rule T-S fuzzy model in state-space representation:

Plant criterion 1: if

is “about 0 rad”, the following holds:

Plant criterion 2: if

is “about

rad or

rad”, the following holds:

in which

,

When solving the LMI conditions, we select the controller gain as

, and assume that

satisfies the constraint

. By resolving the prescribed optimization tasks under

, the subsequent minimized solutions are yielded:

Thus, we can obtain the observer gains

For simulation, set initial conditions as

. The parameters are chosen as

,

,

, and

represents the nonlinear function. The adaptive laws follow Equation (

18), with parameters

and

. For the implementation of the neural network, the centers are set as

, and the widths are given by

. Simulation results are illustrated in

Figure 1,

Figure 2,

Figure 3,

Figure 4,

Figure 5,

Figure 6,

Figure 7,

Figure 8,

Figure 9 and

Figure 10.

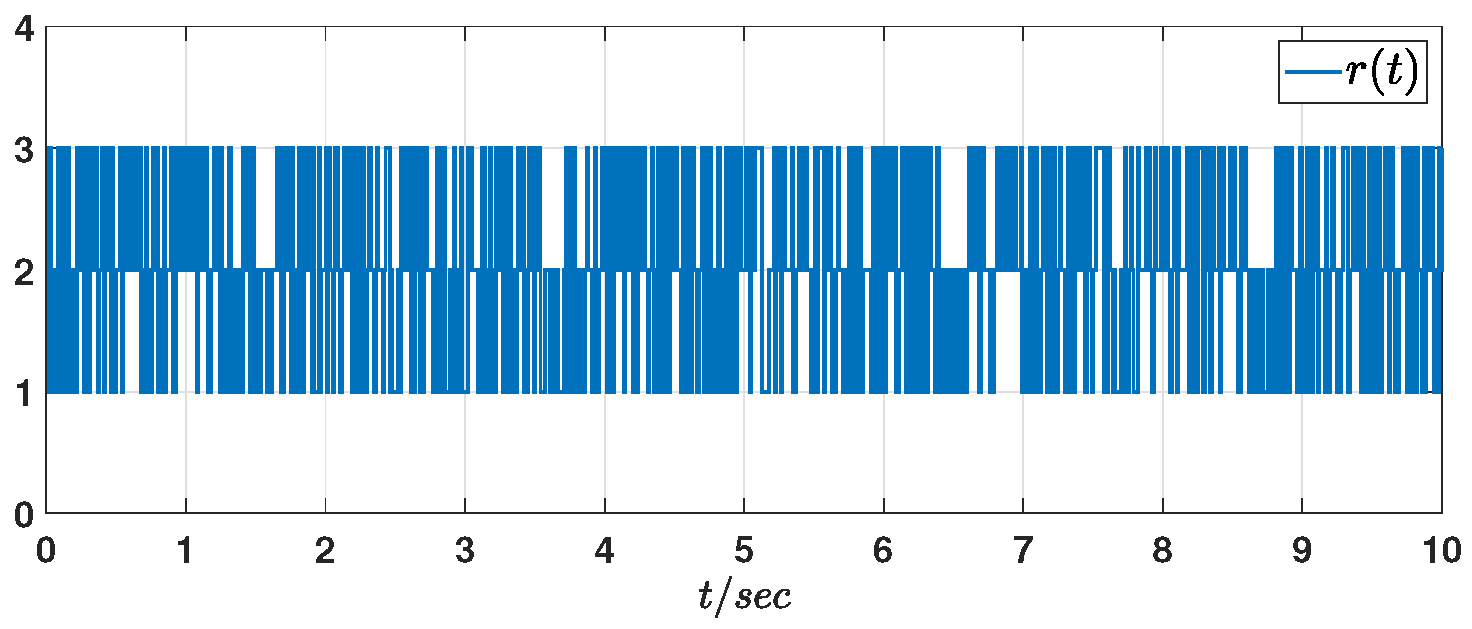

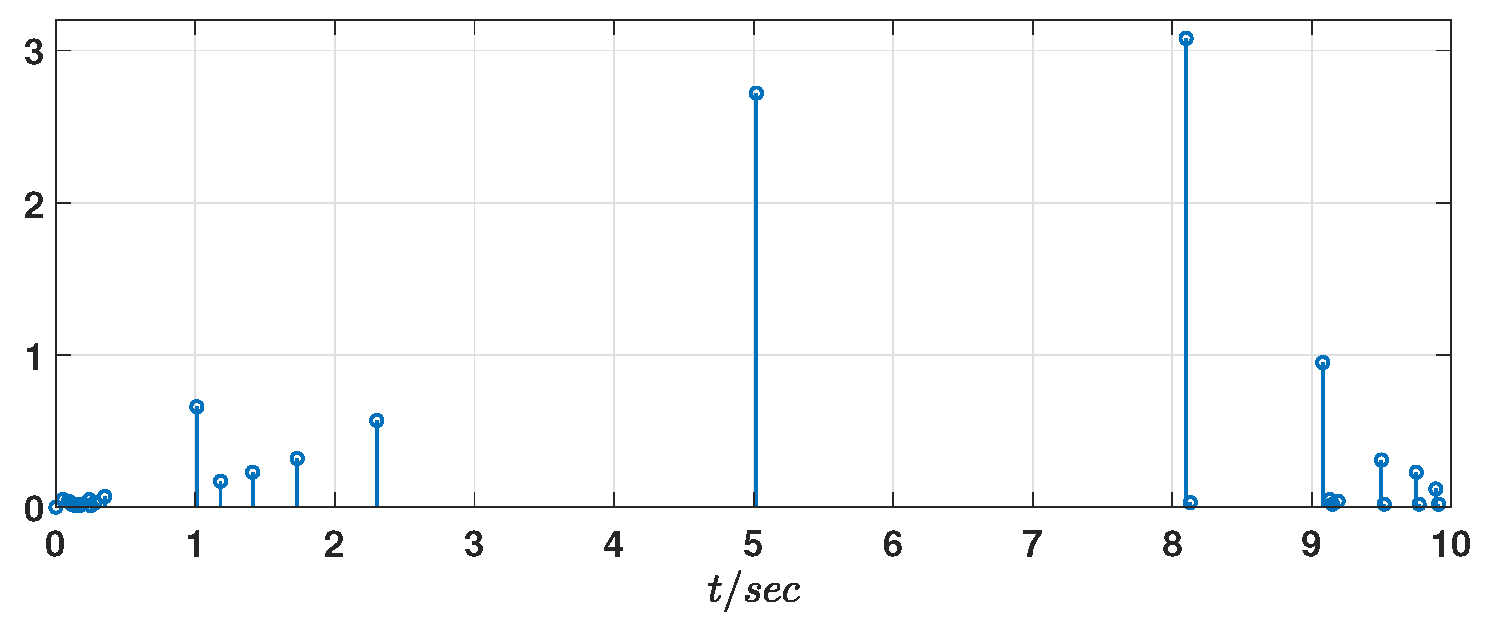

Figure 1 shows the evolution of the jumping modes.

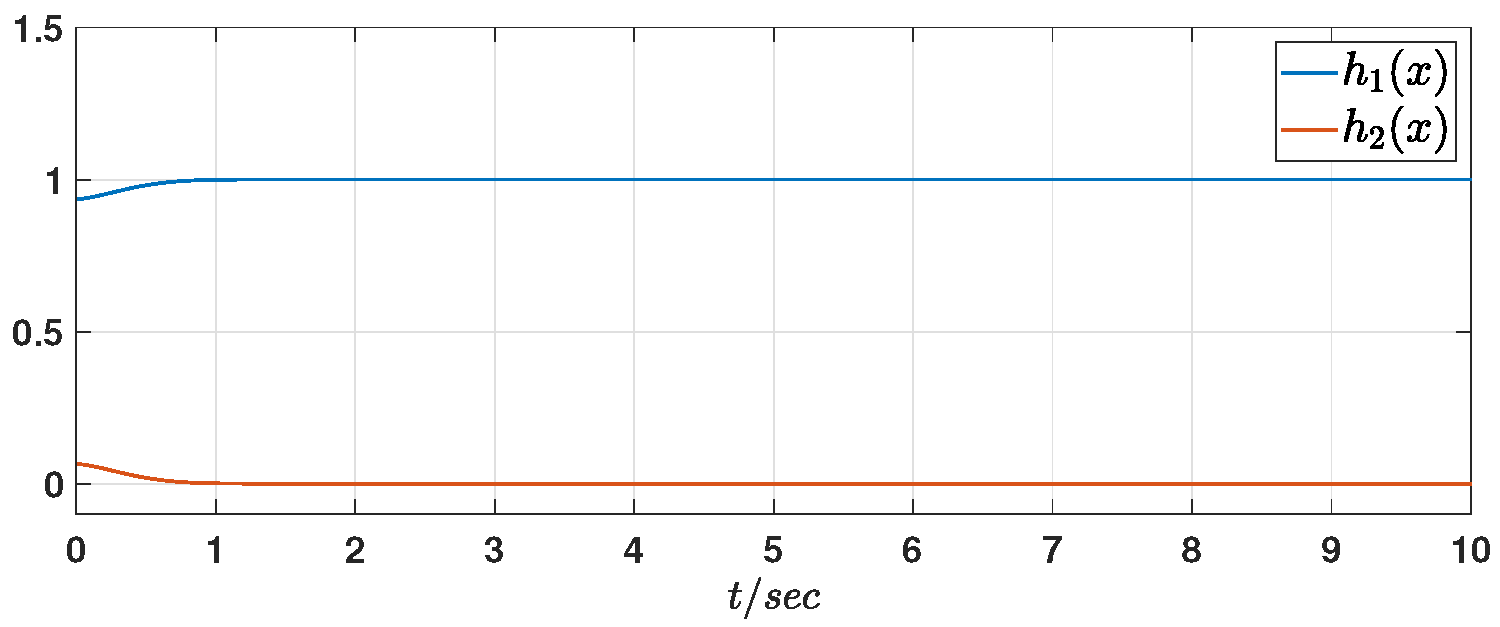

Figure 2 presents the fuzzy membership functions.

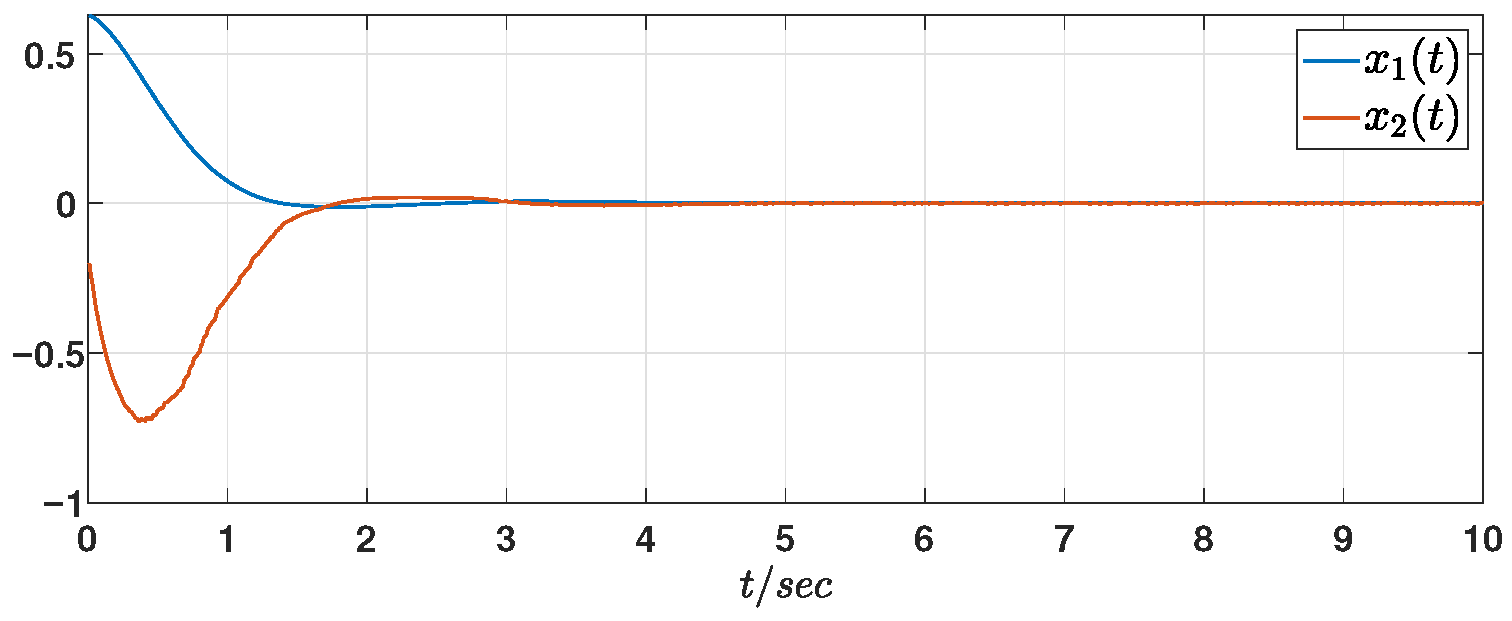

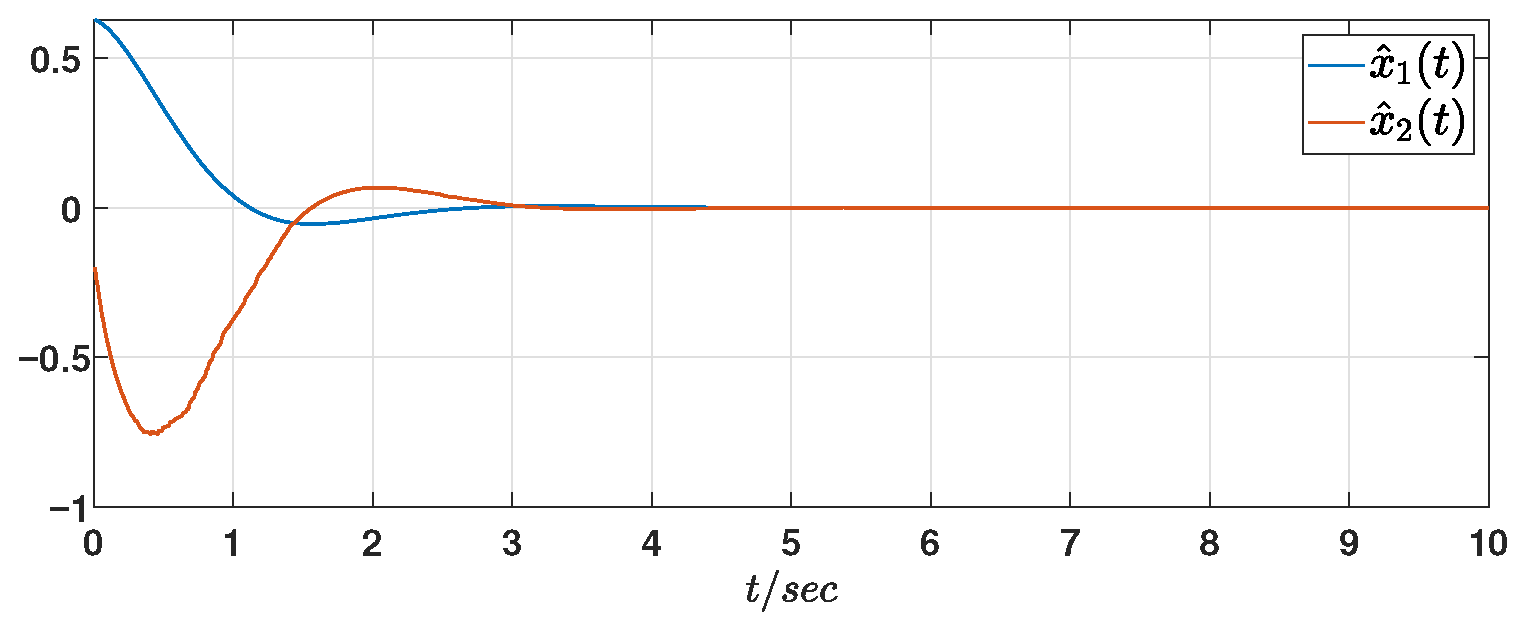

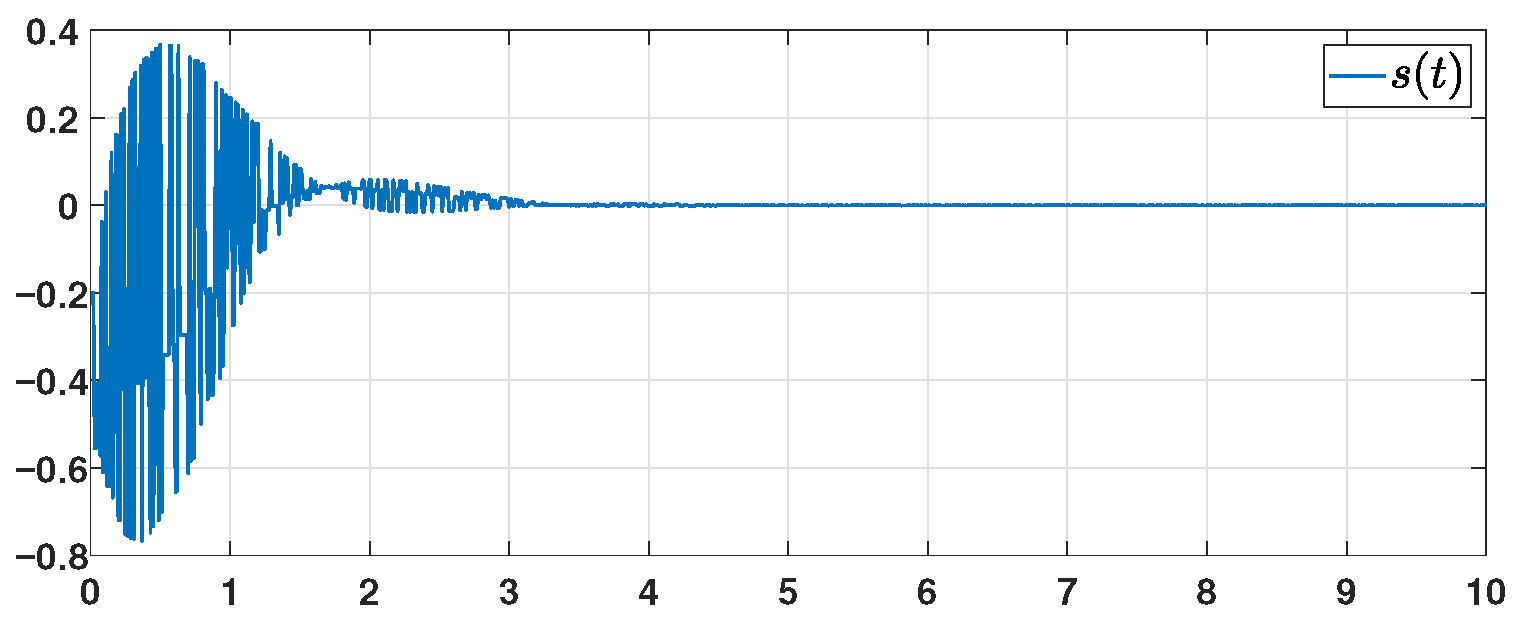

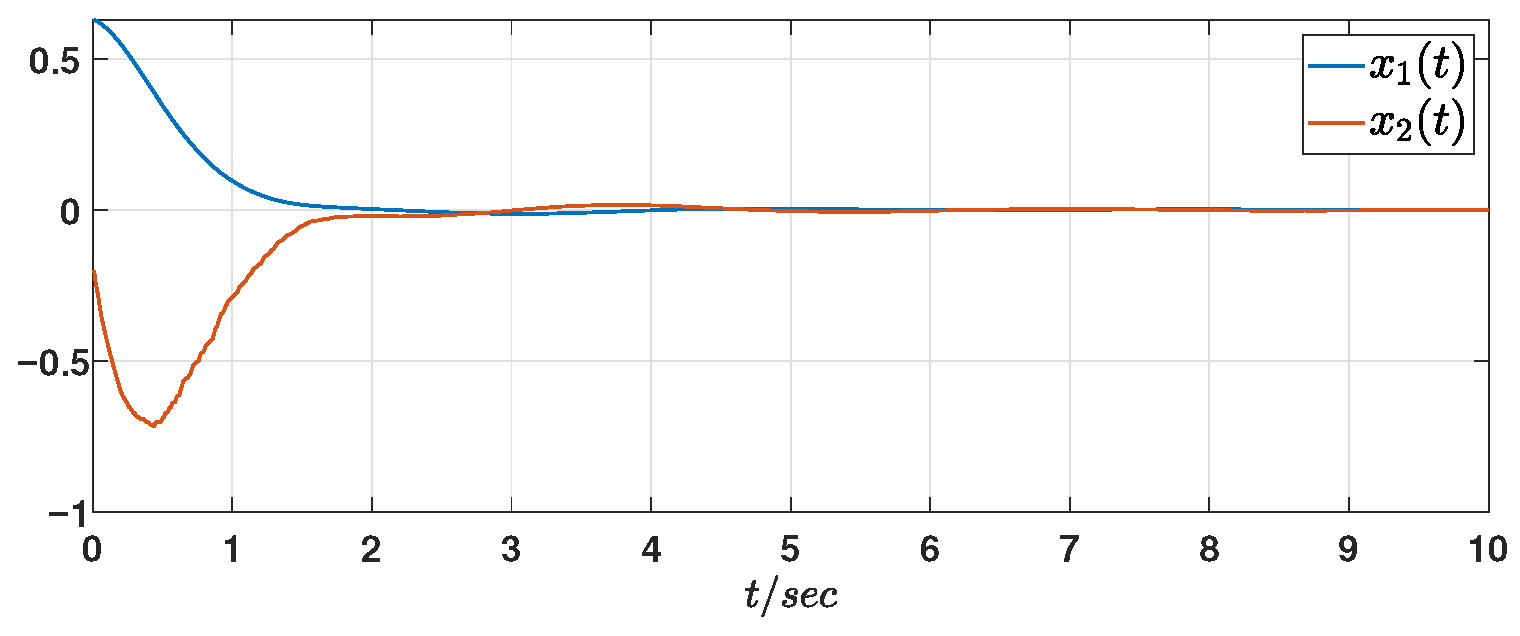

Figure 3 and

Figure 4 depict the state responses of the original system (

1) and the observer system (

6), respectively. The dynamic behavior of the sliding manifold is depicted in

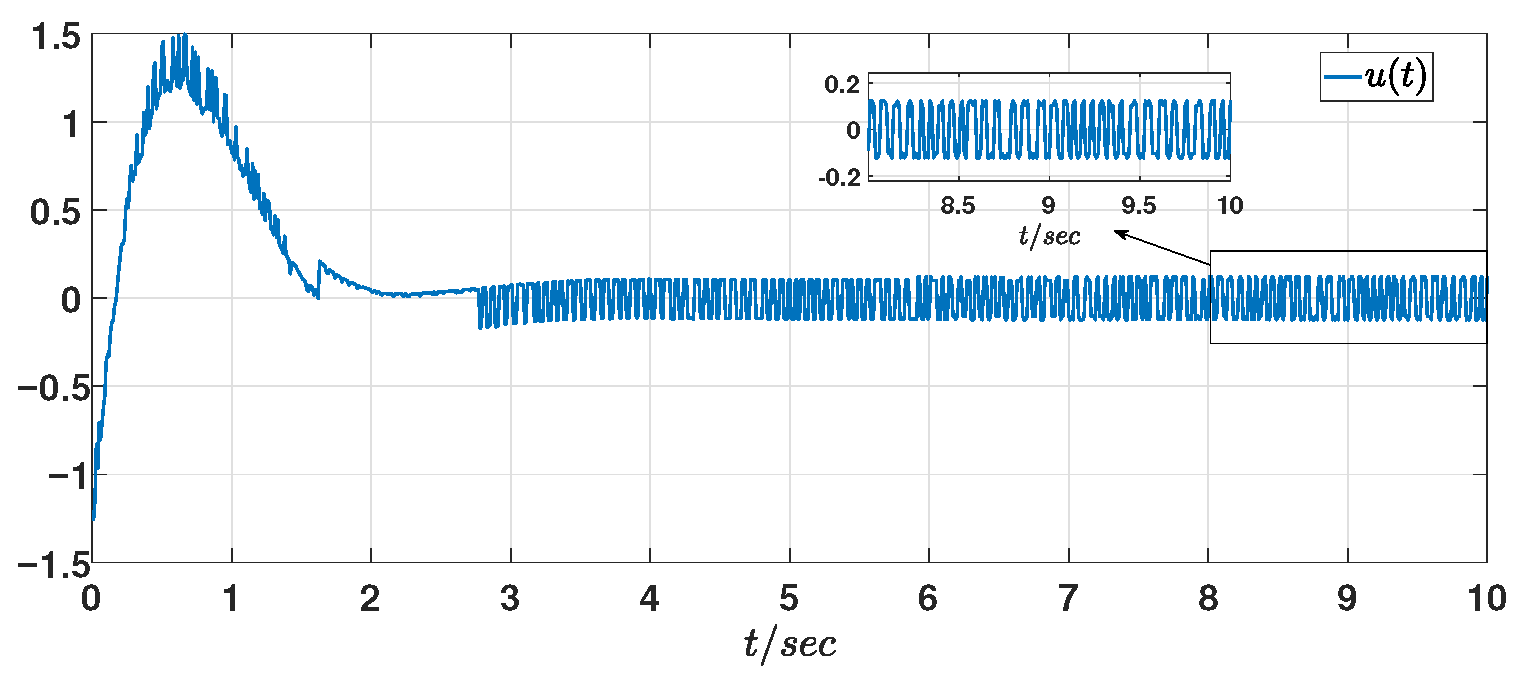

Figure 5. Variations in the control input signal are shown in

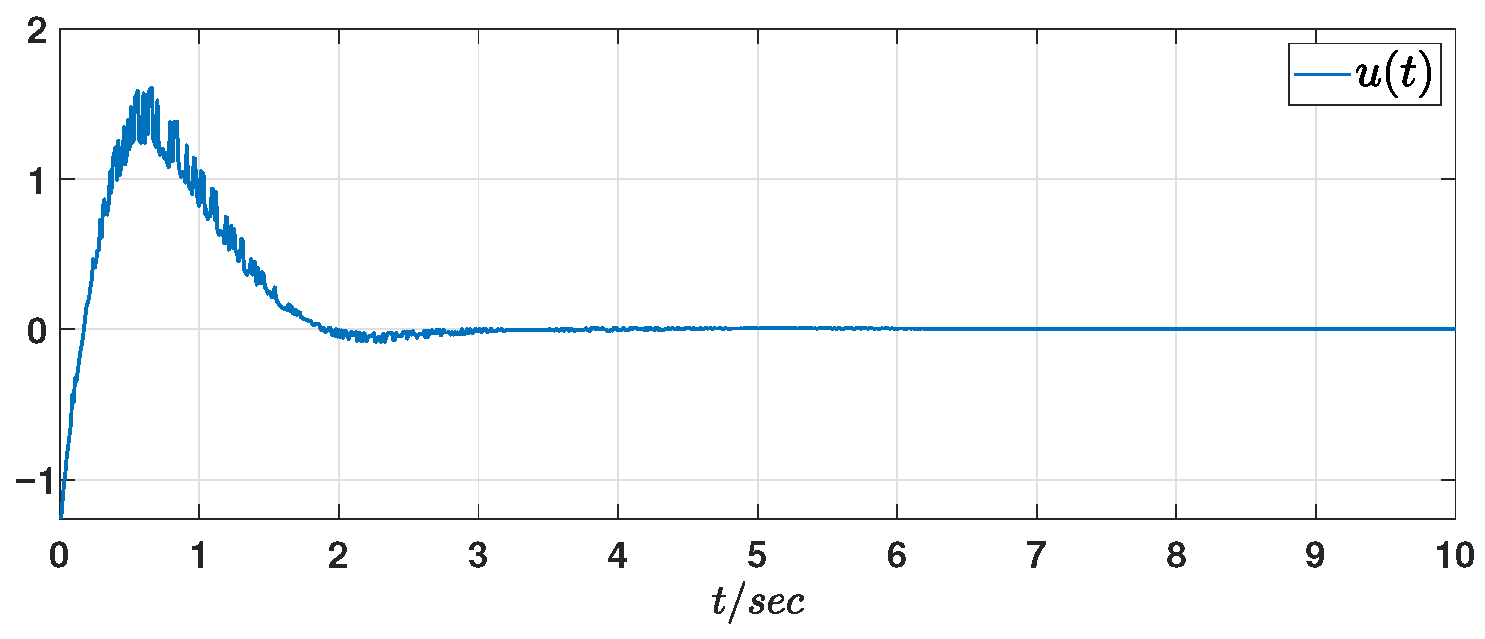

Figure 6, which exhibits a severe chattering effect. To mitigate this issue, the switching signal

is replaced with

. As a result, the curve of the quasi-control input, shown in

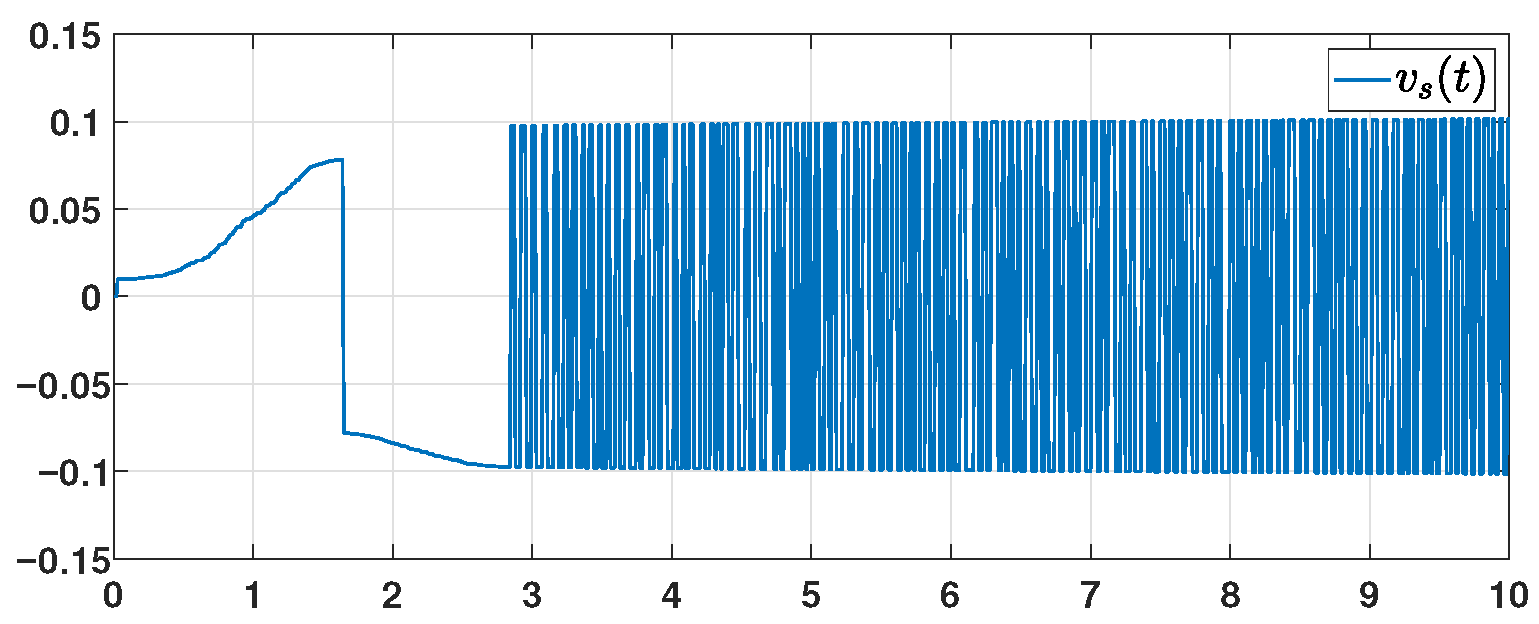

Figure 7, demonstrates a significant reduction in the chattering effect. Operational characteristics of the compensation mechanism are captured in

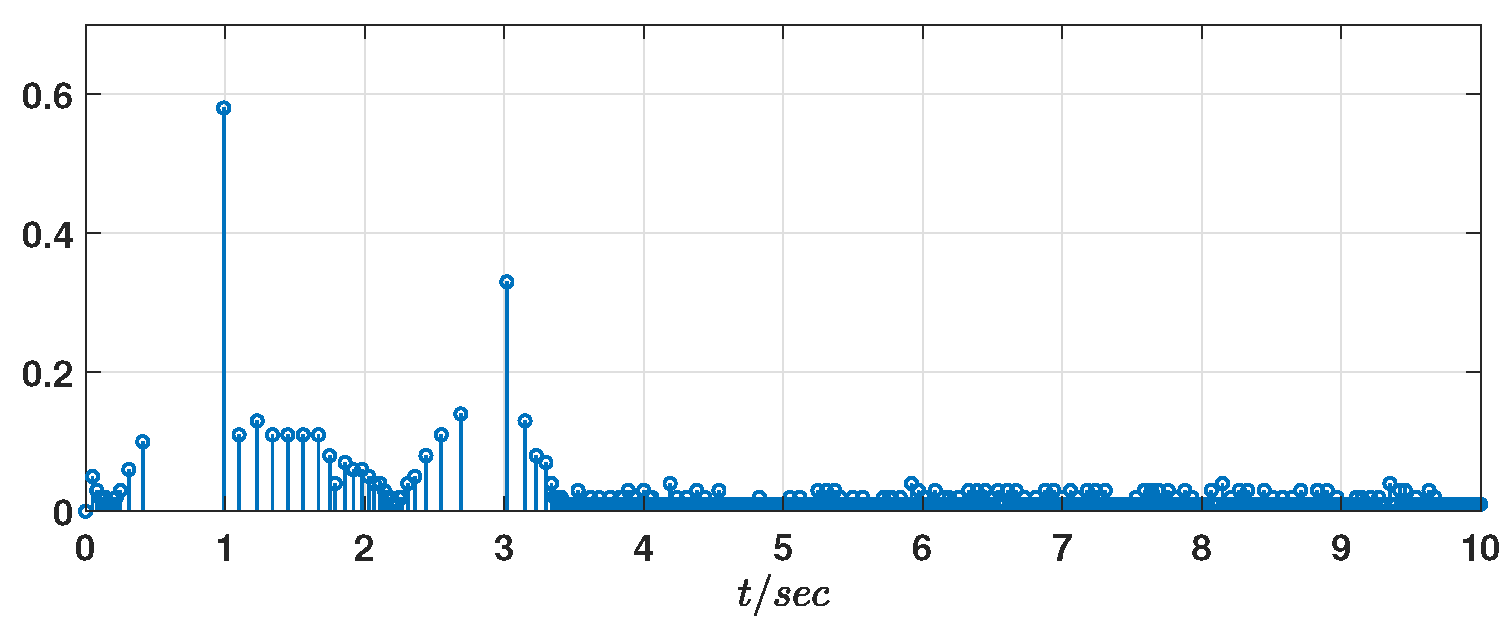

Figure 8. Event-triggered instants and inter-event durations governed by the dynamic ETC strategy (

5) are documented in

Figure 9, in which 31 triggering events are detected. For comparison, a static ETC mechanism is also considered, in which the internal variable

in Equation (

5) is omitted. The corresponding result is shown in

Figure 10, where 583 triggering events are observed. This comparison clearly demonstrates that the dynamic ETC mechanism achieves longer average event intervals, thereby improving network efficiency by nearly

over the observed interval. To make the comparison more transparent, we add the average inter-event time

, where

and

s denote the initial and final simulation times. Hence,

Consequently, the system requires fewer updates and communications, significantly reducing the number of triggering events and conserving communication resources.

Furthermore, to evaluate the robustness of the neural compensator-based SMC, a simulation is conducted under the condition where no neural compensator is implemented. The resulting state response of the original plant, affected by unknown nonlinearities, is shown in

Figure 11. Compared with the response shown in

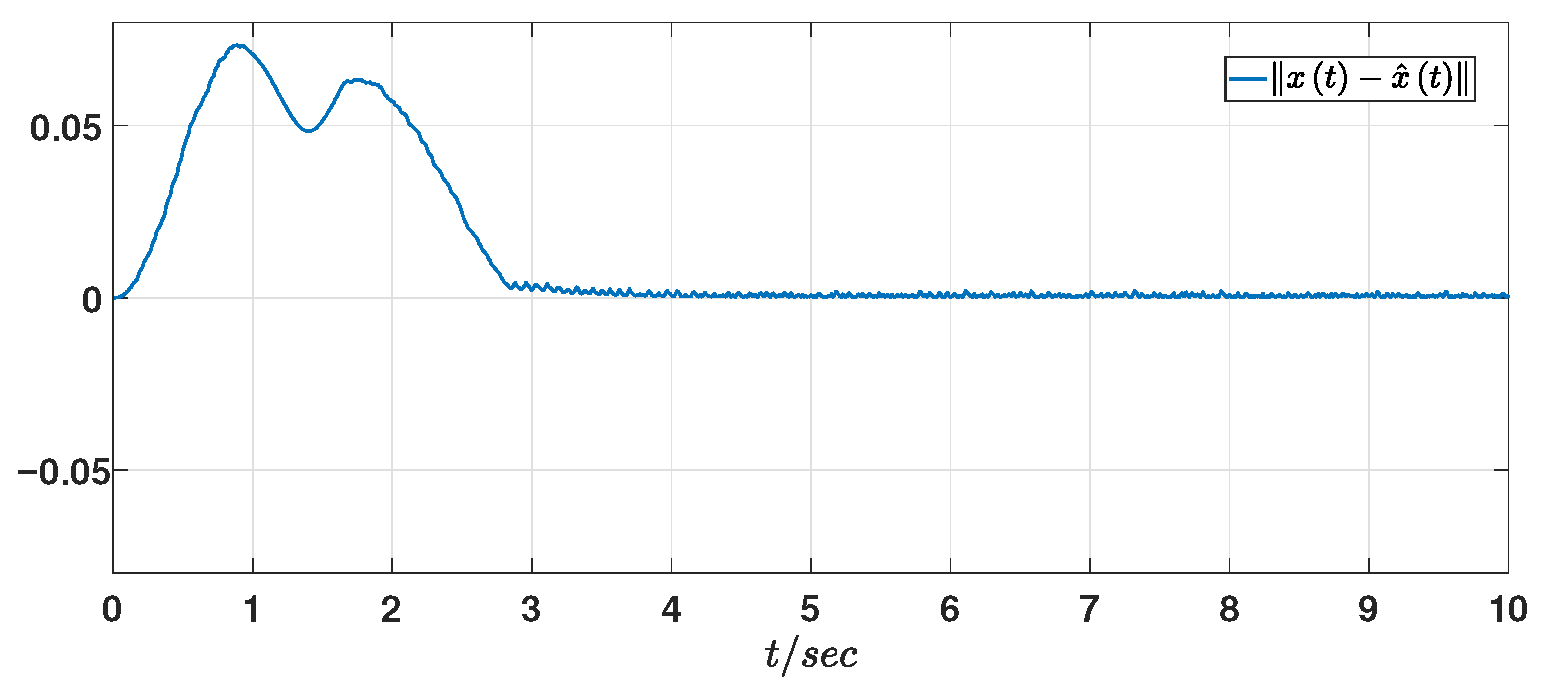

Figure 3, the proposed neural compensator-based SMC exhibits superior performance in terms of faster response, improved transient behavior, and better steady-state characteristics. Meanwhile,

Figure 12 provided the variation trajectory of the

-norm value of the system error, greatly improving the reliability and verifiability of the simulation.

Remark 4. The communication load reduction is primarily due to the dynamic event-triggered structure, while the NN compensator modifies the closed-loop dynamics, but does not enter the triggering inequality, and therefore, it influences the event sequence only indirectly.

Remark 5. The proposed dynamic event-triggered observer-based neural SMC method has significantly outperformed conventional SMC and non-event-triggered benchmark approaches across multiple aspects. By estimating unmeasurable premise variables through a state observer and reconstructing input matrices, it has overcome traditional SMCs’ strict requirements on measurable variables and specific input matrix structures. The incorporation of an RBF neural network-based online adaptive compensation mechanism has effectively suppressed unknown nonlinear disturbances, eliminating traditional SMCs’ dependence on disturbance boundaries and conservative gain selection. The dynamic event-triggered mechanism has extended the average triggering interval from 0.017 s in static mechanisms to 0.323 s, reducing the communication load by approximately . The established LMI stability conditions have enabled handling of generally uncertain TRs, enhancing robustness in Markov jump systems. This method has demonstrated superior comprehensive control performance, robustness, and resource efficiency under multiple challenges.