5.2. Baseline Partially Homomorphic Schemes

For reference, PHE schemes such as Paillier and ElGamal were implemented using the GMP library. These implementations serve as a baseline for comparison with more advanced HE schemes. Both algorithms were evaluated on datasets of increasing size, corresponding to batches of 100, 1000, and 10,000 encrypted values. Each experiment measured the average time required for key generation, encryption, decryption, and homomorphic aggregation over these datasets.

The Paillier cryptosystem was implemented following its standard mathematical formulation [

46]. It provides an additive homomorphic property, enabling the computation of plaintext sums through ciphertext multiplication. In this study, the implementation relied on the GMP to efficiently handle large integer operations and modular exponentiation.

The Paillier cryptosystem operates over a composite modulus , where p and q are two large, distinct prime numbers. The security of the scheme relies on the difficulty of solving problems related to modular arithmetic over this composite modulus.

The key generation process defines two main keys:

Public key: , where is a generator used during encryption. The public key is shared with all users who need to encrypt data.

Private key: , used for decryption. Here, represents the least common multiple of and ; this value ensures compatibility between the two prime factors. The term denotes the modular inverse of modulo n, which enables recovery of the original plaintext during decryption.

A plaintext message

is encrypted using a random value

as

The random factor r guarantees that encrypting the same message twice produces different ciphertexts, which prevents attackers from detecting repeated plaintexts.

Decryption uses the private key to recover

m from

c:

The auxiliary function extracts information from values modulo and is essential for reconstructing the original plaintext.

The Paillier scheme supports

additive homomorphism: multiplying two ciphertexts corresponds to adding the underlying plaintexts, i.e.,

This property allows computations such as summations or averages to be performed directly on encrypted data, without revealing individual plaintext values.

In our prototype implementation, the Paillier cryptosystem was used to demonstrate and validate the additive homomorphic property in practice. For realistic deployments, cryptographic security requires large prime moduli, typically at least 1024 bits, to prevent factorization attacks and ensure compliance with modern security standards [

8]. This implementation serves as a baseline for comparing PHE with more advanced SWHE and FHE schemes in

Section 5.

The ElGamal cryptosystem [

47] operates over a multiplicative cyclic group

defined by a large prime modulus

p. It provides a multiplicative homomorphic property, meaning that the product of ciphertexts corresponds to the product of the underlying plaintexts after decryption. This characteristic makes it useful for secure aggregation and computations that rely on multiplication in privacy-preserving applications.

The key generation process defines two main keys:

Public key: , where g is a generator of the group , and . The public key parameters are shared with all parties performing encryption.

Private key: x, a randomly selected integer from the range . The value x must remain secret and is used during decryption.

A plaintext message

is encrypted using a randomly chosen ephemeral key

. The encryption process produces a ciphertext pair:

The random value y ensures that encrypting the same message multiple times produces distinct ciphertexts, which prevents attackers from recognizing identical plaintexts.

Decryption is performed using the private key

x. The recipient computes an auxiliary value

and then recovers the plaintext as

where

denotes the modular inverse of

s modulo

p, i.e., the value satisfying

.

The multiplicative homomorphism of ElGamal encryption is verified by the relation:

where

denotes the ciphertext pair corresponding to plaintext

. The component-wise multiplication of two ciphertexts,

produces a valid encryption of the product of the two plaintexts. In other words, multiplying ciphertexts results in the encryption of

.

For experimental evaluation, the ElGamal implementation was used to validate the multiplicative homomorphism and to benchmark core cryptographic operations, including key generation, encryption, decryption, and ciphertext multiplication. As with the Paillier cryptosystem, the GMP was employed to efficiently handle modular exponentiation and large-integer arithmetic.

In practical deployments, secure configurations rely on large prime moduli (typically at least 2048 bits) and cryptographically secure random number generators (CSPRNGs) for generating the ephemeral key

y. These measures are essential to ensure resistance against discrete logarithm attacks and to comply with modern cryptographic security recommendations [

8].

As shown in

Table 5, both the time and memory requirements increase approximately linearly with the number of encrypted values. Since the size of a single ciphertext remains constant, the overall data volume scales proportionally to the input size.

To extend the previous analysis, the same methodology was applied to the ElGamal scheme, which provides a multiplicative rather than additive homomorphism. When compared with Paillier, ElGamal achieves notably shorter encryption and decryption times for an equal number of inputs. For instance, when processing 10,000 values, ElGamal encryption was about 2.3× faster and decryption about 12× faster than Paillier.

The ciphertext size and memory usage were comparable for both schemes, as each ElGamal ciphertext consists of two components with a total size of roughly 256 bytes. Overall, ElGamal is more efficient in terms of computational cost, particularly for large datasets and multiplicative operations, whereas Paillier remains an effective choice for applications requiring homomorphic addition.

5.3. Baseline Somewhat Homomorphic Schemes

The performance of the BFV scheme was evaluated using the Microsoft SEAL library (v4.1), an open-source framework for HE that enables computations to be carried out directly on encrypted data. This approach ensures that plaintexts remain confidential throughout all stages of computation and allows the development of fully encrypted end-to-end processing pipelines and secure cloud services without exposing decryption keys to external entities.

The efficiency and accuracy of BFV computations depend on a set of key cryptographic parameters that jointly determine the trade-off between performance, security, and noise tolerance. In this study, the polynomial modulus degree was set to , providing a balance between computational cost and the depth of supported operations. The coefficient modulus followed SEAL’s default configuration for approximately 128-bit security, while the plaintext modulus was fixed at , which offers efficient integer arithmetic for typical encrypted workloads. The plaintext modulus t defines the numeric range in which plaintext arithmetic is performed: all BFV computations occur modulo t, meaning that values wrap around this modulus. Larger values of t allow a broader representable range of plaintexts but may increase noise growth, whereas smaller values reduce noise at the cost of a narrower arithmetic domain. All timing results represent the average of ten runs using identical random plaintext vectors of 1000 integers.

Table 6 demonstrates that the available noise budget decreases after each homomorphic operation, particularly following multiplications and relinearizations. Larger polynomial modulus degrees provide higher residual noise budgets, enabling deeper computational circuits at the cost of increased runtime and memory consumption. As expected, the runtime of all operations grows approximately linearly with the polynomial modulus degree, consistent with the

complexity of polynomial arithmetic. These results highlight the inherent trade-off between computational depth and performance in the BFV scheme, emphasizing the need for parameter tuning based on application-specific latency and accuracy requirements.

The polynomial modulus degree N plays a crucial role in balancing computational efficiency and numerical stability. Smaller degrees () offer faster execution but quickly deplete the available noise budget, limiting the number of homomorphic operations that can be performed without bootstrapping. Conversely, higher degrees () support a greater multiplicative depth and improved resistance to noise accumulation, albeit at the cost of increased computational and memory overhead.

Among the evaluated operations, multiplication is the most computationally demanding (≈18.6 ms for ), while addition and decryption remain relatively lightweight. These findings are consistent with the theoretical behavior of the BFV scheme, where noise growth scales with the multiplicative depth and is inversely related to the polynomial modulus size.

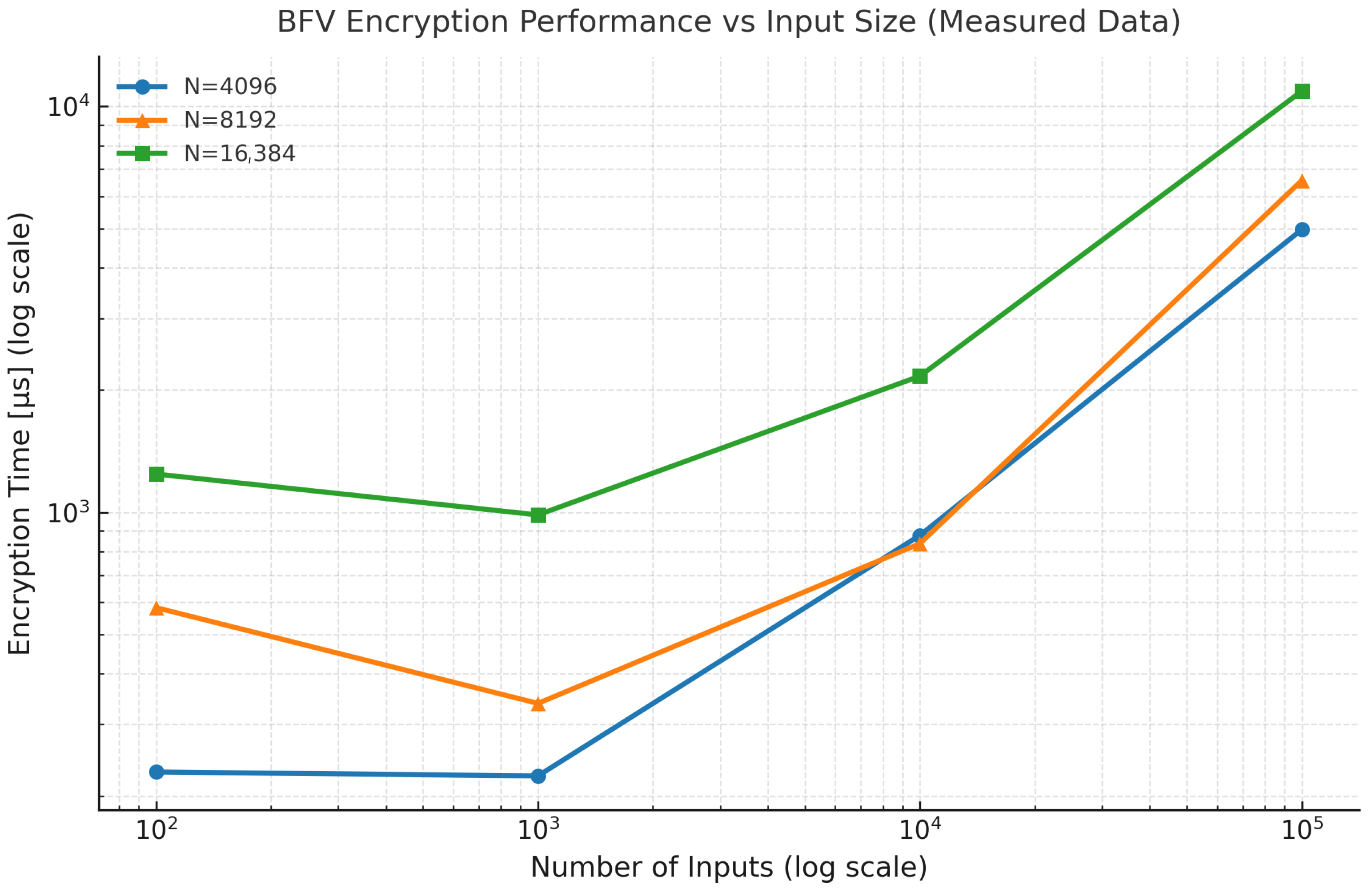

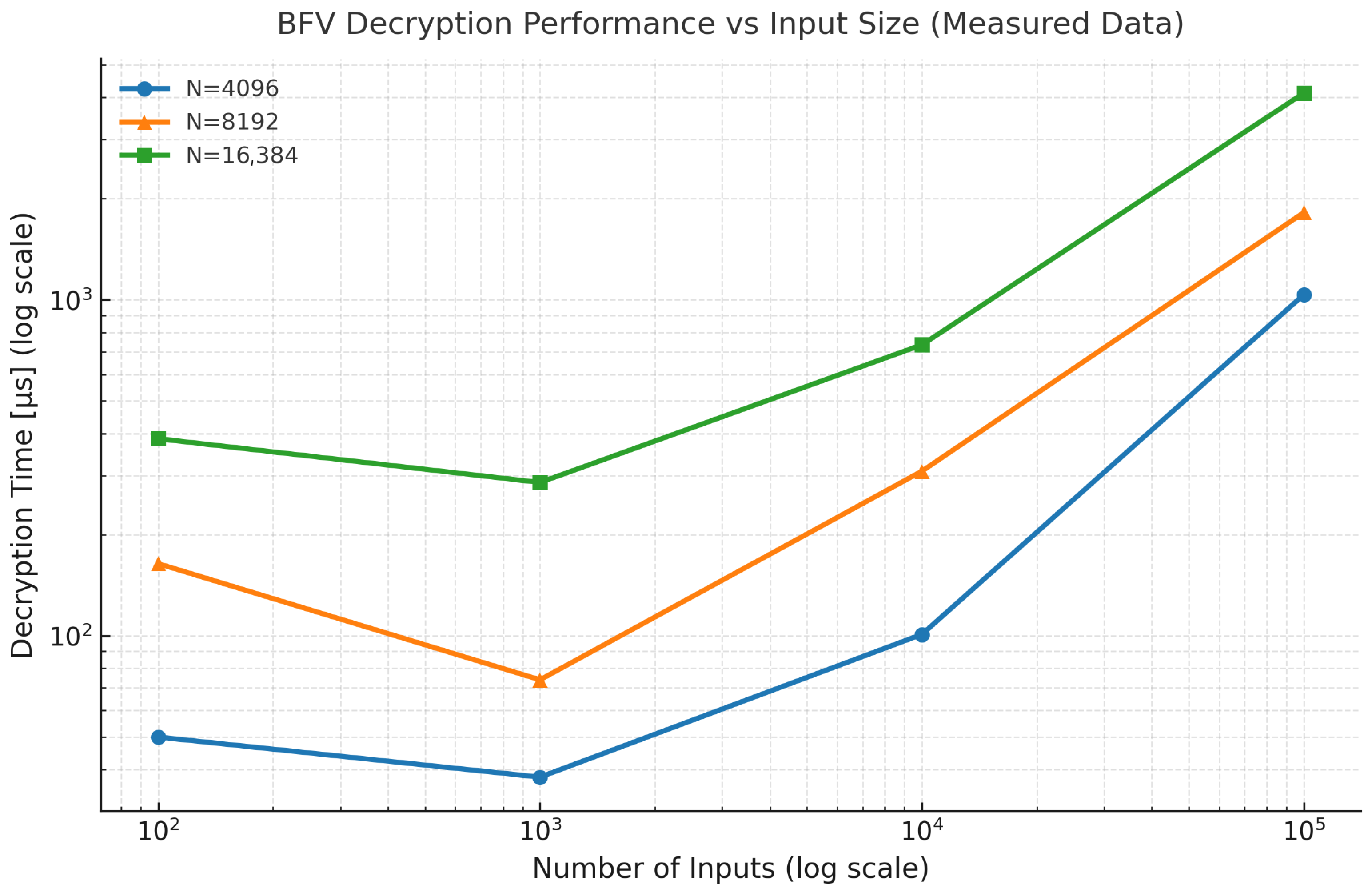

5.3.1. Scaling Behavior and Parameter Impact on BFV Performance

The effect of the polynomial modulus degree (N) and input size on the computational efficiency of the BFV scheme was analyzed using the Microsoft SEAL library. Random integer datasets of varying sizes (100, 1000, 10,000, and 100,000 elements) were encrypted and decrypted to evaluate execution time (in µs), ciphertext size (in MB), and peak memory consumption (in MB). This experiment aimed to assess the scalability of BFV encryption with respect to the number of inputs and parameter configuration.

For all tested configurations, the runtime scaled approximately linearly with the number of inputs and nearly quadratically with the polynomial modulus degree

N. The smallest configuration (

) provided the fastest execution at the cost of a smaller noise budget and lower security margin, while

N = 16,384 achieved higher precision and security at a higher computational cost. Memory consumption increased modestly (from approximately 12 MB to 130 MB), remaining within practical limits for standard computing platforms. These findings confirm that the BFV scheme exhibits predictable scalability, balancing performance, accuracy, and cryptographic strength. Encryption results are shown in

Figure 2, and the corresponding decryption results in

Figure 3.

5.3.2. Impact of Homomorphic Operations on Runtime and Noise Budget

The performance of homomorphic addition and multiplication operations was evaluated at with a plaintext modulus . The experiments measured runtime, noise budget, and memory usage during consecutive encrypted computations.

Homomorphic addition causes negligible noise growth, with the noise budget remaining effectively constant across repeated operations. The average runtime per addition is approximately 220 µs, and the memory footprint remains stable around 109 MB, indicating that addition is computationally lightweight and predictable. The measured characteristics of homomorphic addition are summarized in

Table 7.

In contrast, homomorphic multiplication incurs a substantially higher computational cost and memory demand. Each multiplication reduces the noise budget by roughly 30 bits and increases runtime by about two orders of magnitude compared to addition. The measured characteristics of homomorphic multiplication are summarized in

Table 8. The required relinearization step adds further overhead but is essential to maintain ciphertext size and ensure correct decryption.

Overall, these results confirm that addition operations in the BFV scheme are nearly noise-free and highly efficient, whereas multiplication introduces rapid noise consumption and significant computational overhead. Proper parameter selection and circuit-depth optimization are therefore critical for maintaining decryptability and runtime efficiency in practical applications.

5.4. Performance Evaluation of Fully Homomorphic Encryption

The performance evaluation of FHE was conducted using the CKKS scheme implemented in the OpenFHE library (version 1.1.1). All experiments were executed on the same workstation configuration described earlier (Intel Core i5-9300H, 16 GB DDR4 RAM, Windows 11 64-bit). CKKS was chosen because it supports approximate arithmetic over real numbers, making it particularly suitable for encrypted analytics and privacy-preserving computation on continuous data. The OpenFHE framework provides an optimized implementation of bootstrapping, a mechanism that refreshes ciphertexts and restores the noise budget after multiple homomorphic operations.

5.4.1. Cryptographic Parameter Configuration

The cryptographic context was initialized with the following parameters:

Ring dimension : defines the size of the polynomial ring and determines both computational parallelism and the number of encoding slots ().

Secret key distribution: ternary uniform distribution , providing efficient sampling and balanced noise.

Security level: manually selected to balance precision and performance rather than using predefined security presets.

Key switching method: Brakerski–Fan (BF) for lightweight operations such as addition, and hybrid switching for computationally intensive operations such as multiplication and bootstrapping.

Scaling and modulus sizes: flexible automatic scaling using 59-bit prime moduli and a 60-bit initial modulus, ensuring stable precision while maintaining a reasonable noise margin.

Activated features: public-key encryption, key switching, leveled and bootstrapped operations, enabling the full FHE workflow.

Key generation and evaluation-key setup were performed prior to execution to support multiplicative operations of higher depth. During experiments, the environment automatically managed ciphertext levels, modulus switching, and scaling, ensuring that the noise budget remained within decryptable limits throughout all computations.

5.4.2. Data Encoding and Encryption Process

Plaintext data were represented as real-valued vectors of length not exceeding , corresponding to the number of available encoding slots in the CKKS scheme. Each vector was encoded into a plaintext polynomial and then encrypted to produce the ciphertext representation. During encryption, the following metrics were recorded:

Decryption was subsequently applied to verify computational correctness by comparing the decrypted outputs with the original plaintext values, confirming the reversibility of the homomorphic processing pipeline.

5.4.3. Effect of Ring Dimension on Performance

To assess the scalability of CKKS, encryption was tested for two ring dimensions (

and

), corresponding to 2048 and 8192 available slots.

Table 9 summarizes encryption and decryption performance, ciphertext size, and memory usage. A larger ring dimension increases ciphertext capacity but also linearly increases computational cost and memory footprint.

As observed, increasing the ring dimension results in larger ciphertexts (from 120 kB to nearly 500 kB) and higher memory usage, yet encryption and decryption times remain within a few milliseconds, demonstrating good scalability.

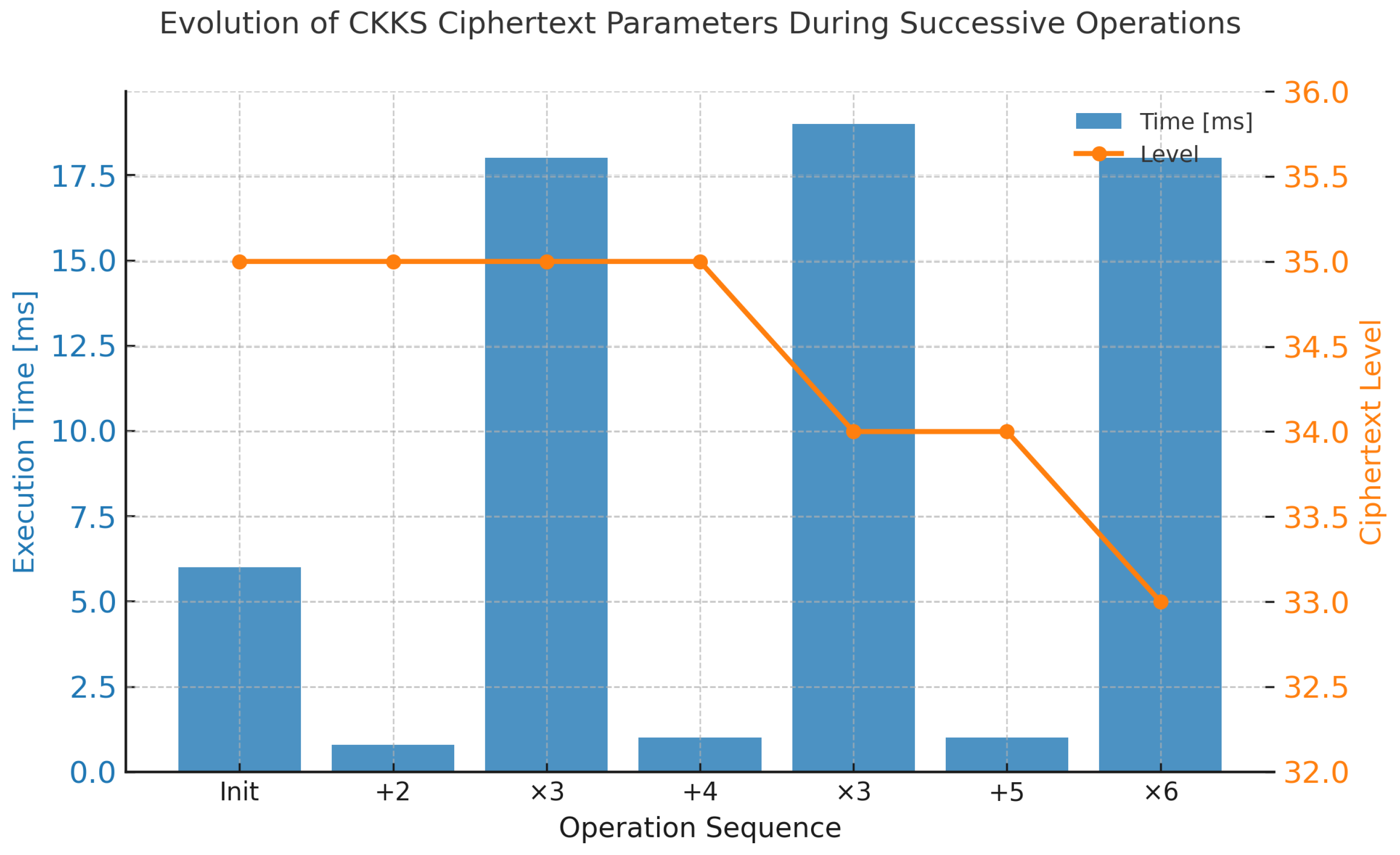

5.4.4. Homomorphic Addition and Multiplication Analysis

Homomorphic addition and multiplication were evaluated to illustrate their computational asymmetry and level reduction behavior in the CKKS scheme.

Figure 4 shows that multiplication dominates execution time due to rescaling and key-switching overhead, while addition remains nearly instantaneous.

Each multiplication reduces the ciphertext level by one, consistent with modular chain reduction, and slightly decreases the ciphertext size as coefficients are rescaled. Throughout all operations, the ciphertext memory footprint remains stable (around 660–670 MB), indicating efficient in-place processing and key reuse within the evaluator.

5.4.5. Bootstrapping and Level Restoration

When repeated multiplications exhausted the available ciphertext levels, a bootstrapping procedure was applied to refresh the ciphertext and restore its computational depth. The corresponding performance metrics are summarized in

Table 10.

Bootstrapping successfully restored the ciphertext level from 2 to 16, enabling additional homomorphic operations without re-encryption. Although the process introduced a latency of approximately 2.2 s and temporarily increased the ciphertext size nearly fivefold, it preserved decryptability and continuity of computation. Memory usage remained stable (around 670 MB), demonstrating efficient resource management by the underlying implementation.

5.4.6. Numerical Precision and Comparative Analysis

Numerical precision and performance for representative CKKS operations with

are summarized in

Table 11. The mean squared error (MSE) between plaintext and decrypted results remained below

for all evaluated operations, confirming the suitability of the CKKS scheme for approximate analytics in practical settings.

As expected, bootstrapping dominates the computational cost, being roughly six orders of magnitude slower than basic arithmetic operations. Nevertheless, this step is essential to restore full homomorphic depth and enable continued computation on encrypted data. The observed MSE values indicate negligible precision loss, validating CKKS as an efficient and accurate scheme for approximate encrypted computation.

5.4.7. Plaintext vs. Homomorphic Computation

To quantitatively assess the computational overhead introduced by HE, a variance computation was performed on 4000 randomly generated integers uniformly distributed within the range

. The same operation was executed both in plaintext and under different encryption paradigms using representative homomorphic schemes (BFV and CKKS).

Table 12 reports the measured execution times, ciphertext sizes, memory usage, and relative slowdowns for each configuration.

As observed in

Table 12, PHE (BFV) operations incur a computational slowdown of approximately four orders of magnitude compared with direct arithmetic. This performance degradation primarily arises from ciphertext expansion and modular polynomial arithmetic. The leveled variant of CKKS (without bootstrapping) exhibits an even higher overhead, reflecting the cost of rescaling and key-switching operations required to manage noise growth during multiplicative depth expansion. When bootstrapping is enabled, CKKS achieves FHE functionality by refreshing the accumulated noise and restoring ciphertext validity at the expense of an additional three orders of magnitude in runtime. Despite this substantial computational cost, homomorphic computation guarantees complete data confidentiality, as all intermediate values remain encrypted throughout the processing pipeline. These findings highlight the fundamental trade-off between computational efficiency and privacy preservation inherent in HE, illustrating that performance remains application-dependent and strongly influenced by parameter selection and the chosen level of homomorphism.