1. Introduction

With the rapid growth of China’s economy, the scale of transmission lines has expanded continuously, and their operating environments have become increasingly complex [

1]. In recent years, the rising occurrence of extreme weather events has led to more frequent conductor galloping accidents, posing a serious threat to the secure operation of power grids [

2,

3,

4]. Composite interphase spacers have been widely implemented as an effective mitigation measure, and are now extensively used across overhead lines at various voltage levels [

4,

5,

6,

7]. However, as their installation numbers grow and service periods lengthen, field reports have revealed failures such as hardware detachment, flashover, and string breakage, all of which can compromise transmission reliability [

8,

9,

10].

Composite interphase spacers belong to the broader family of composite insulators and share similar material systems and interfacial structures. Consequently, existing research on composite-insulator failures provides an important foundation for understanding the service behavior of interphase spacers [

11,

12]. In recent years, decay-like fracture has become an increasingly prominent issue in composite insulators, arising from the combined action of electrical, environmental, and mechanical stresses during long-term operation [

13]. Bastidas et al. [

14] and Kumara et al. [

15] reported that interfacial electric-field distortion can initiate partial discharges and accelerate internal insulation breakdown. Gao et al. [

16,

17,

18,

19] reported that discharge and current stresses cause glass fiber breakage and epoxy resin degradation, leading to decay-like fractures. Lu et al. [

20,

21,

22] linked spacer flashover and decay-induced heating to internal defects that trigger partial discharges, which appear externally as localized abnormal temperature rise. Peng et al. [

23,

24] showed that silicone rubber shed defects accelerate root degradation, propagating through the sheath and resulting in sheath–core interface failure.

Moisture ingress has also been identified as a key factor accelerating the decay process. Field observations by Lutz [

25] confirmed the importance of water intrusion, while Wang et al. [

26] demonstrated that moisture increases interfacial leakage current and induces local heating before fracture. Shen et al. [

27] pointed out that the combined effect of temperature and humidity can intensify epoxy resin oxidation and molecular breakdown. Moreover, Xu et al. [

28] and Zhong et al. [

29,

30] emphasized that moisture, discharge activity, and cyclic mechanical loading act together to promote the deterioration of the core under humid service environments. Collectively, these results indicate that decay-like aging arises from the coupled influence of electrical, environmental, and mechanical stresses.

However, most existing literature focuses on conventional composite insulators, whereas systematic investigations dedicated to composite interphase spacers remain limited. Although both devices employ GFRP core rods, interphase spacers differ markedly from conventional insulators in geometry, loading boundary conditions, and high-voltage-end field distribution. As a result, degradation models developed for composite insulators cannot be directly applied to interphase spacers.

To address this gap, the paper examines the first reported case of core rod decay-like fracture in a 500 kV composite interphase spacer. Through integrated macroscopic observation, material characterization, and electric-field simulation, the degradation mechanisms are analyzed, and corresponding structural and material optimization strategies are proposed to enhance the long-term reliability of UHV composite interphase spacers.

2. Sample and Methodology

2.1. Case Description

The failed 500 kV composite interphase spacer was removed from a double-circuit transmission line in central China. The line, 7.7 km long with 25 towers (13 tension and 12 suspension), was commissioned in 2012 and located in a Grade-III galloping region where all spans were equipped with anti-galloping spacers. The spacer was located in an inland region with a temperate monsoon climate, characterized by an annual mean temperature of about 16 °C and an average relative humidity of roughly 60%. During routine inspection, one spacer was found fractured near the lower span of a tower. The failure was repaired by live-line replacement and represented the first reported case of core-rod fracture in a 500 kV interphase spacer in this region.

As shown in

Figure 1, the fractured spacer exhibited severe whitening, friability, and chalking at the core rod fracture surface. The adhesion between the core rod and sheath had completely deteriorated, accompanied by significant cracking and detachment of the sheath, leaving the glass fibers fully exposed. These features are consistent with typical decay-like fracture. In addition, other parts of the sheath showed long cracks, electrical erosion pits, discoloration, and obvious degradation.

2.2. Experimental Samples

The failed spacer (model FXJV-500/120) is composed of two composite interphase spacer sections and associated hardware, interconnected by ball-and-socket joints. Structurally, it is arranged in the sequence of a split-conductor clamp, an interphase composite insulator, an adjusting plate, a second interphase composite insulator, and a split-conductor clamp at the opposite end.

Each insulator section adopted a half-shed configuration to meet the creepage-distance requirements of 500 kV lines and to comply with relevant standards. One section had its half-shed facing the adjusting plate, whereas the other faced the clamp. The fracture occurred at the high-voltage end of the lower insulator, approximately 10 cm from the end fitting, where no protective shed was installed on the sheath surface.

2.3. Characterization Methods

2.3.1. Shore Hardness

Shore hardness was measured using a BAREISS HPE III-00 (Bareiss GmbH, Oberdischingen, Germany) durometer to assess the aging degree of the HTV silicone–rubber sheath and sheds. Each specimen was tested five times at different points, and the average value was recorded.

2.3.2. Hydrophobicity

The hydrophobicity test was performed using a contact angle meter (JY-82, Dedu Equipment, Changzhou, China). Each sample’s static contact angle was measured five times and the average value was taken.

2.3.3. Industrial Computed Tomography (CT)

Industrial CT scanning (GE AX2000 X-ray CT System, GE Inspection Technologies, Wunstorf, Germany) was used for nondestructive visualization of the internal structure, bonding state, and compactness of the core-sheath assembly. The scans were performed under controlled temperature and humidity conditions (23 °C, 28% RH) with a tube voltage of 140 kV, current of 100 µA, integration time of 0.5 s, and 1440 projections, achieving a spatial resolution of 15 µm.

2.3.4. Fourier-Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR)

FTIR analysis identified the molecular composition and functional groups of organic materials. Characteristic absorption peaks and corresponding wavenumbers were used to determine chemical bonds. Measurements were performed using a Thermo Fisher Nicolet iS50 FTIR spectrometer, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA covering 7800–350 cm−1 with a 4 cm−1 resolution.

2.3.5. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM)

Microscopic morphology was examined using a KEYENCE VE-9800S field-emission SEM, Keyence Corporation, Osaka, Japan. Prior to testing, samples were ultrasonically cleaned in anhydrous ethanol for 1 h and oven-dried at 60 °C.

2.3.6. X-Ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS)

XPS was performed using a Thermo Scientific K-Alpha 134 XPS system, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA to analyze the elemental composition and chemical states of the core rod.

2.3.7. Leakage Current Test

Leakage current was measured in accordance with IEC 62217 [

31]. The sample was cleaned and then boiled in a 0.1% NaCl solution for 100 h to allow conductive liquid to adhere to the surface, thereby amplifying the measurable current and reducing test uncertainty. The applied voltage was increased to 6 kV at a ramp rate of 1 kV/s and held for 1 min. The voltage and current waveforms were recorded using a high-precision leakage current measurement system with a resolution of 1 μA.

3. Results

3.1. Macroscopic Characterization

3.1.1. Appearance

The failed composite interphase spacer comprised two composite-insulator sections connected by ball-and-socket joints. At the high-voltage end of the lower section, the core rod fractured about 10 cm from the end fitting, in a region without shed protection where only the sheath covered the surface.

The sheath surface was heavily cracked and locally detached, exposing the underlying epoxy–glass-fiber core, which appeared chalky, brittle, and grayish-black. Numerous electrical erosion pits and ablation traces were visible on the sheath, implying long-term partial-discharge activity under humid and high-field conditions. The exposed fibers were embrittled and discolored, while the epoxy matrix exhibited signs of decomposition.

These features indicate severe interfacial deterioration near the high-voltage end and extensive material degradation around the fracture region, consistent with a decay-like failure pattern of composite insulators.

3.1.2. Hardness

Shore hardness measurements were performed on the sheds and sheaths of both sections of the spacer. Three test points were selected along each insulator—from the high-voltage end to the adjusting plate. The results are summarized in

Table 1. Compared with the intact spacer, the sheath at the high-voltage end of the fractured insulator showed a marked increase in hardness. None of the sheds displayed cracking or embrittlement during the 90° bending test, suggesting that the shed portion still retained adequate elasticity and mechanical strength.

3.1.3. Hydrophobicity

The results are summarized in

Figure 2. The fractured spacer exhibited a slight decrease in hydrophobicity at the high-voltage end, whereas the middle and adjusting-plate sections maintained similar levels to those of the intact sample. Overall, the measured contact angle remained within the acceptable range for field operation.

3.1.4. Cross-Sectional Analysis

To further examine the internal deterioration and the bonding condition between the sheath and core rod, the fractured insulator was dissected. As shown in

Figure 3, the sheath near the fracture could be easily separated from the core, exhibiting a hardened, brittle, and powdery texture—evidence of complete interfacial debonding. The exposed core surface appeared dark and porous, consistent with moisture-induced degradation.

The deterioration extended approximately 226 cm axially from the fracture. According to the degree of discoloration, cracking, and adhesion loss, the degraded portion was divided into three zones: heavily degraded (H), moderately degraded (M), and lightly degraded (L). In the H-zone, the sheath was completely detached and the core severely blackened and friable; in the M-zone, cracking and partial discoloration were observed; in the L-zone, the sheath retained partial adhesion, and the core largely preserved its original green color. The sampling layout of the fractured spacer, including the division of heavily, moderately, and lightly degraded zones, is shown in

Figure 4.

Samples approximately 30 mm in length were collected from five positions within each zone (H1–H5, M1–M5, L1–L5) for quantitative evaluation of the cross-sectional degradation area and subsequent CT characterization. Severe decay caused fragmentation of several H-zone samples (H1–H3) during cutting, while M2 was loss. As summarized in

Table 2, the cross-sectional degradation area ratio gradually decreased along the axial direction, following the general order H > M > L. Representative cross-sections are presented in

Figure 5, where the degraded region displays a crescent-shaped front along the sheath–core interface that narrows and fades with increasing distance from the fracture. This spatial trend indicates that degradation initiated at the high-voltage end and propagated axially through interfacial paths.

3.2. Microscopic Characterization

3.2.1. CT Analysis

Representative three-dimensional reconstructions of the core structure are presented in

Figure 6. Pores and voids were classified by equivalent diameter and color-coded for visualization. For each degradation zone, two non-contiguous samples were scanned for comparison. As shown in the 3D maps, the relative defect size followed the order H3 > H5 > M3 > M5 > L3 > L5, indicating that both the number and volume of internal voids decreased with distance from the fracture. Quantitative analysis results are summarized in

Table 3, where the total sample volume, void volume, and corresponding void ratio (void volume/sample volume) were calculated. Due to sample loss, data for H1, H2, and M2 were unavailable.

The results indicate that the defect volume ratio generally decreases from the heavily degraded zone to the lightly degraded zone, consistent with conclusions drawn from appearance observations and 3D modeling. However, exceptions were observed, such as M5 > M4 and L3 > L1, suggesting that M5 was more deteriorated than M4 and L3 more than L1. This implies that although the overall degree of core rod deterioration decreases along the axial direction from the fracture, localized regions may exhibit higher degradation, likely due to variations in operating conditions and environmental factors. Compared with cross-sectional defect area ratios, the defect volume ratio provides a more comprehensive indicator of overall deterioration.

For four typical samples (H3, H5, M3, M5), detailed scans were performed, and both transverse and longitudinal sections were extracted to examine internal degradation (

Figure 7). From these scans, the CT results revealed that all samples contained cracks of varying severity, including partially penetrating cracks within the sheath and interfacial defects between the core and sheath that weakened adhesion. In H5, M3, and M5, several cracks originated from the core–sheath interface and propagated outward, but had not yet penetrated the sheath; these cracks are expected to evolve into fully penetrating cracks with further degradation. In contrast, H3, H5, and M3 already exhibited cracks that penetrated through the sheath, extending deep into the core rod. In particular, H3 and H5 contained cracks that had fully penetrated the core, while M3 exhibited cracks approaching full penetration.

3.2.2. FTIR Analysis

The core rod was mainly composed of epoxy resin and glass fibers, whereas the sheath consisted primarily of silicone rubber, silica, and Al(OH)

3. The obtained FTIR spectra are presented in

Figure 8. The FTIR spectra of the fractured core rod differed significantly from those of the intact region, with marked changes in vertical scaling and more complex spectral contours. Distinct absorption peaks appeared at 3600–3700 cm

−1, 1733.77 cm

−1, and 910 cm

−1, while the band at 2340–2360 cm

−1 corresponded to CO

2 interference from the ambient air.

The sharp absorption peak at 3600–3700 cm−1 indicates substantial hydrolysis of the glass fibers, where moisture disrupted the Si–O–Si network and generated a large number of Si–OH terminal groups. This hydrolytic process directly weakened the mechanical strength of the fibers. The strong peak at 1733.77 cm−1 reflects the formation of carbonyl (C=O) groups, suggesting oxidation of the epoxy resin matrix and the generation of aldehydes, ketones, and carboxylic acids. The absorption at 910 cm−1 confirms the presence of Si–OH and Si–O bonds, providing additional evidence of glass fiber hydrolysis. These results collectively demonstrate that moisture ingress and oxidation are the dominant chemical pathways in the degradation of the composite spacer’s core material.

3.2.3. SEM Analysis

To further investigate the microstructural differences between fractured and intact regions, SEM observations were performed on the sheath and core rod. Two samples were taken from the fracture site (zones 1 and 2) and one from a distant intact region (zone 3), as shown in

Figure 9.

The sheath surface at the fractured area appeared rough and uneven, with numerous cracks, grooves, and microvoids. The silicone rubber matrix exhibited fragmentation, and several regions showed a porous texture caused by material loss. In contrast, the intact sheath displayed a smooth and compact surface without visible defects.

For the core rod, fibers in the fractured region were partially broken or exposed due to resin loss, whereas in the intact region they remained uniformly encapsulated by the epoxy matrix. The interfacial area between fibers and matrix in the fractured zone became discontinuous and loosely bonded. These microscopic observations provide direct evidence of the synergistic degradation of the sheath and core rod, corroborating the results obtained from FTIR and CT analyses.

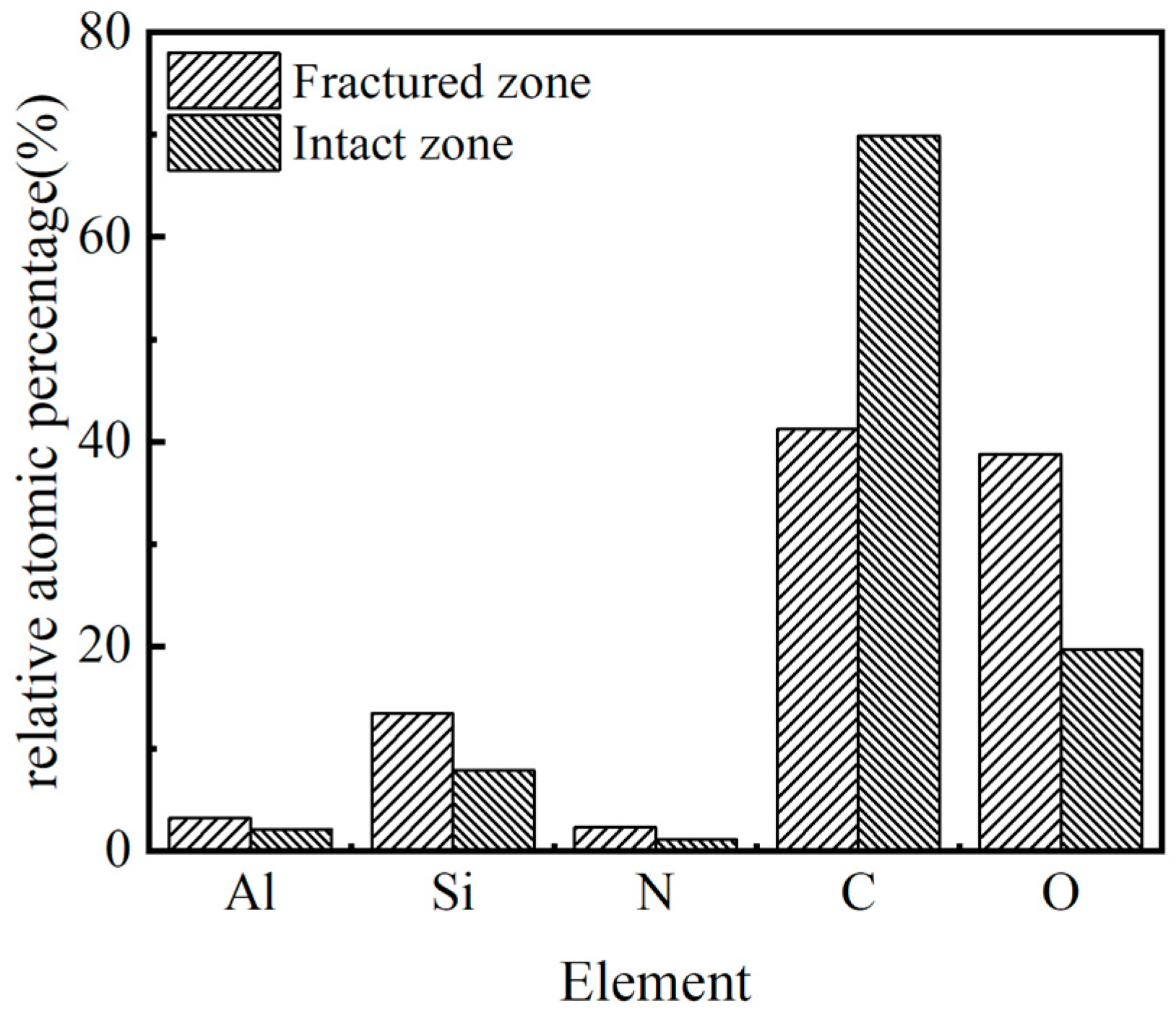

3.2.4. XPS Analysis

XPS was carried out on core rods from different regions to determine their elemental composition, as shown in

Figure 10. Compared with the intact zone, the fractured zone showed lower carbon content and higher oxygen content, implying oxidative decomposition of the epoxy resin in the degraded area. These results are consistent with the SEM, and FTIR findings, confirming the progressive aging and oxidation-driven deterioration of the core material during service.

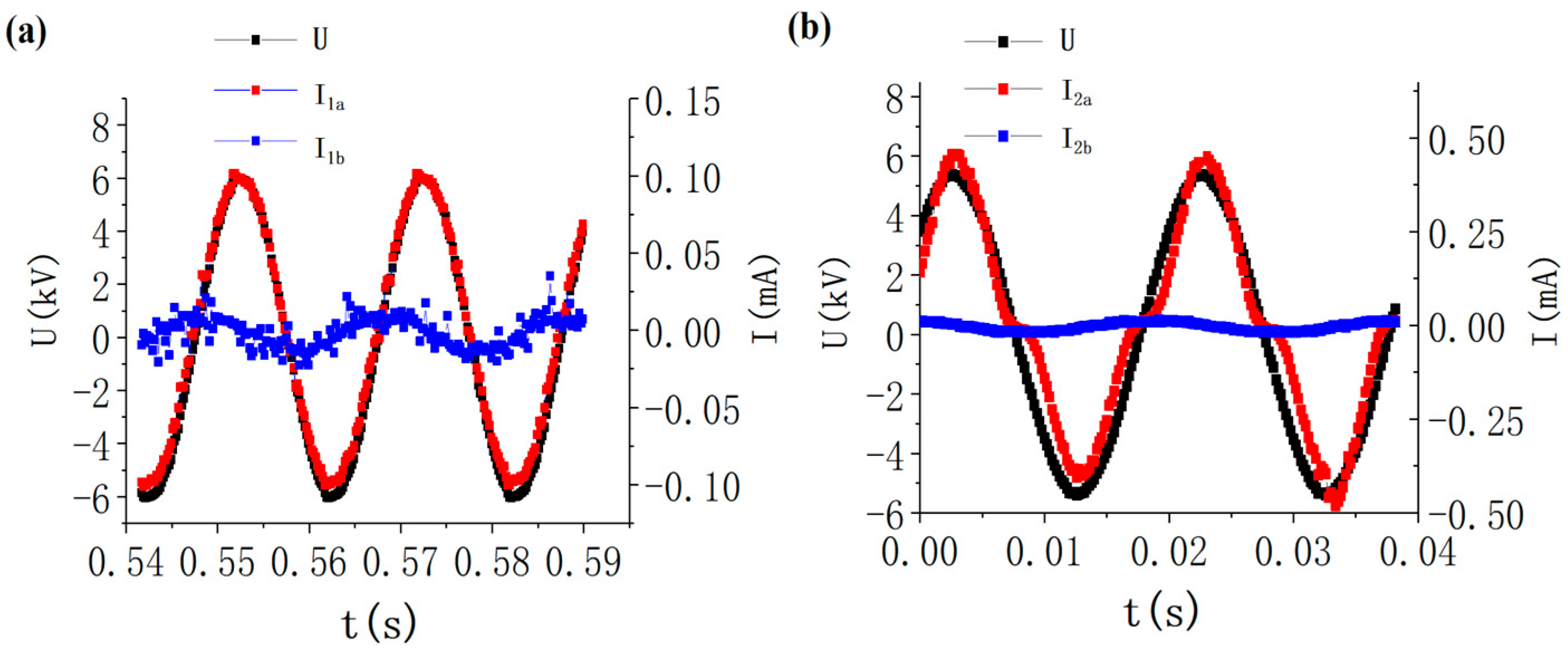

3.3. Leakage Current Analysis

Leakage current tests were performed on short samples taken from both the fractured region and an intact region along the axial direction. The voltage and current waveforms are shown in

Figure 11, where samples labeled a correspond to the fractured high-voltage end, and samples labeled b represent structurally intact region.

Compared with the b-type samples, the a-type samples exhibited a markedly higher leakage current, indicating that the degraded region more readily forms conductive paths. In the a-type samples, the voltage and current were nearly in phase, suggesting that the current was mainly resistive rather than capacitive. In contrast, the leakage current of the b-type samples remained very small, reflecting the dense and continuous surface/interface structure of the intact region.

To further examine the cause of the increased conductivity, the a-type samples were dried at 70 °C for 66 h and retested under the same voltage. After drying, the maximum current decreased to about 0.01 mA, much lower than before, indicating that the enhanced conductivity was largely related to moisture-sensitive conductive species at the interface.

These observations show that the degraded high-voltage end exhibits stronger electrical conduction than the intact region. To better understand the electrical differences along the axial direction, the next section analyzes the electric-field distribution under different shed configurations.

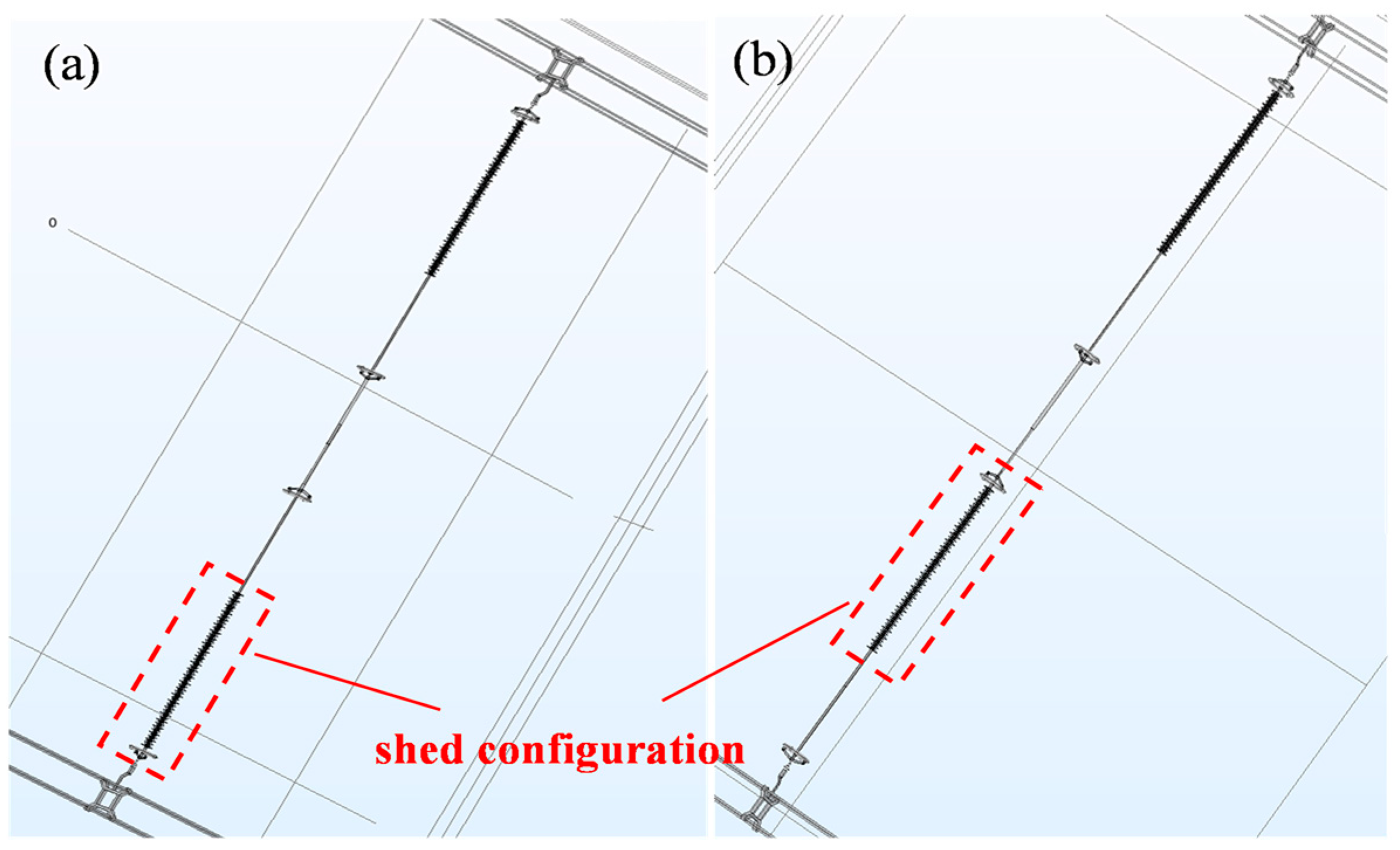

4. Electric Field Distribution

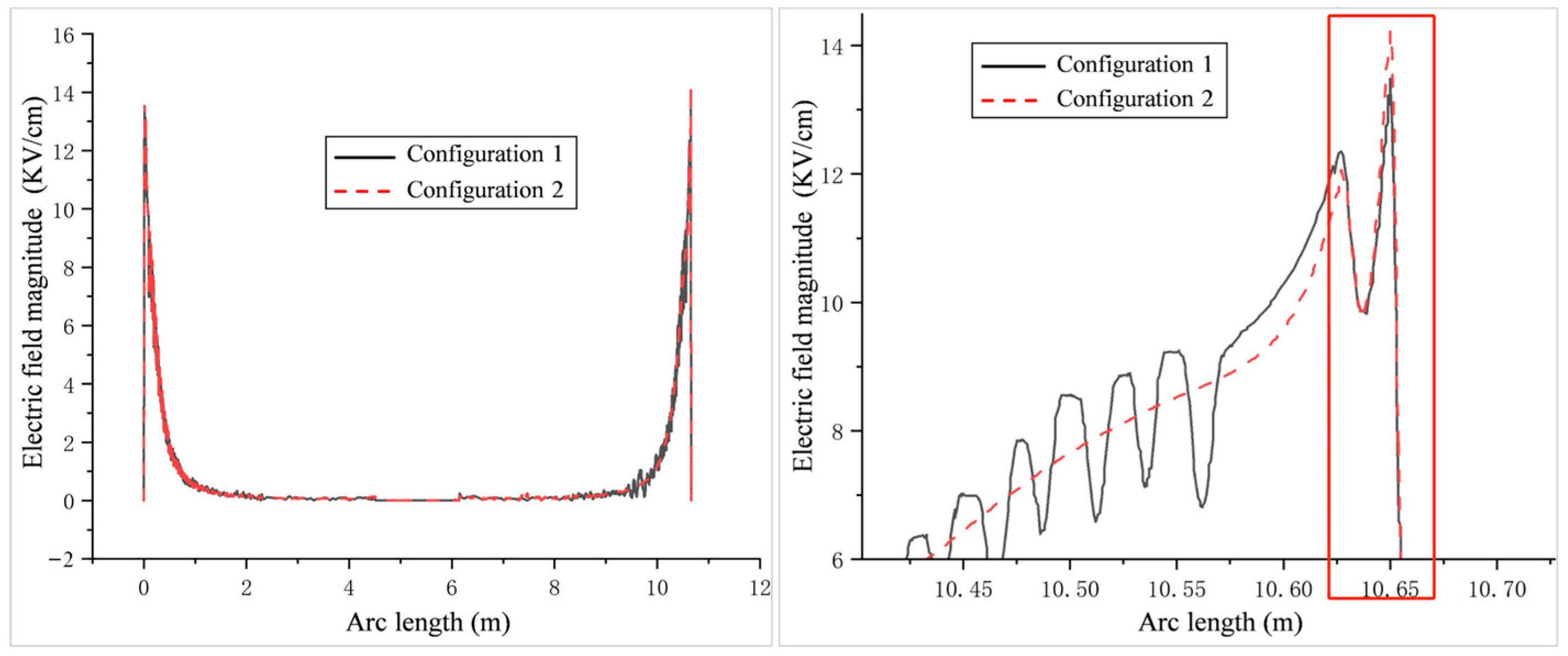

To evaluate the influence of shed configuration on the electric field distribution of the interphase spacer, two geometric models were constructed in COMSOL 6.3 Multiphysics, as illustrated in

Figure 12. Both models consisted of two composite-insulator sections with half-shed designs that met the creepage-distance requirements of 500 kV lines. In Configuration 1, both half-sheds were positioned on the clamp side; in Configuration 2, the sheds were distributed symmetrically on the clamp and adjusting-plate sides. All other structural and material parameters were kept identical to ensure a consistent comparison.

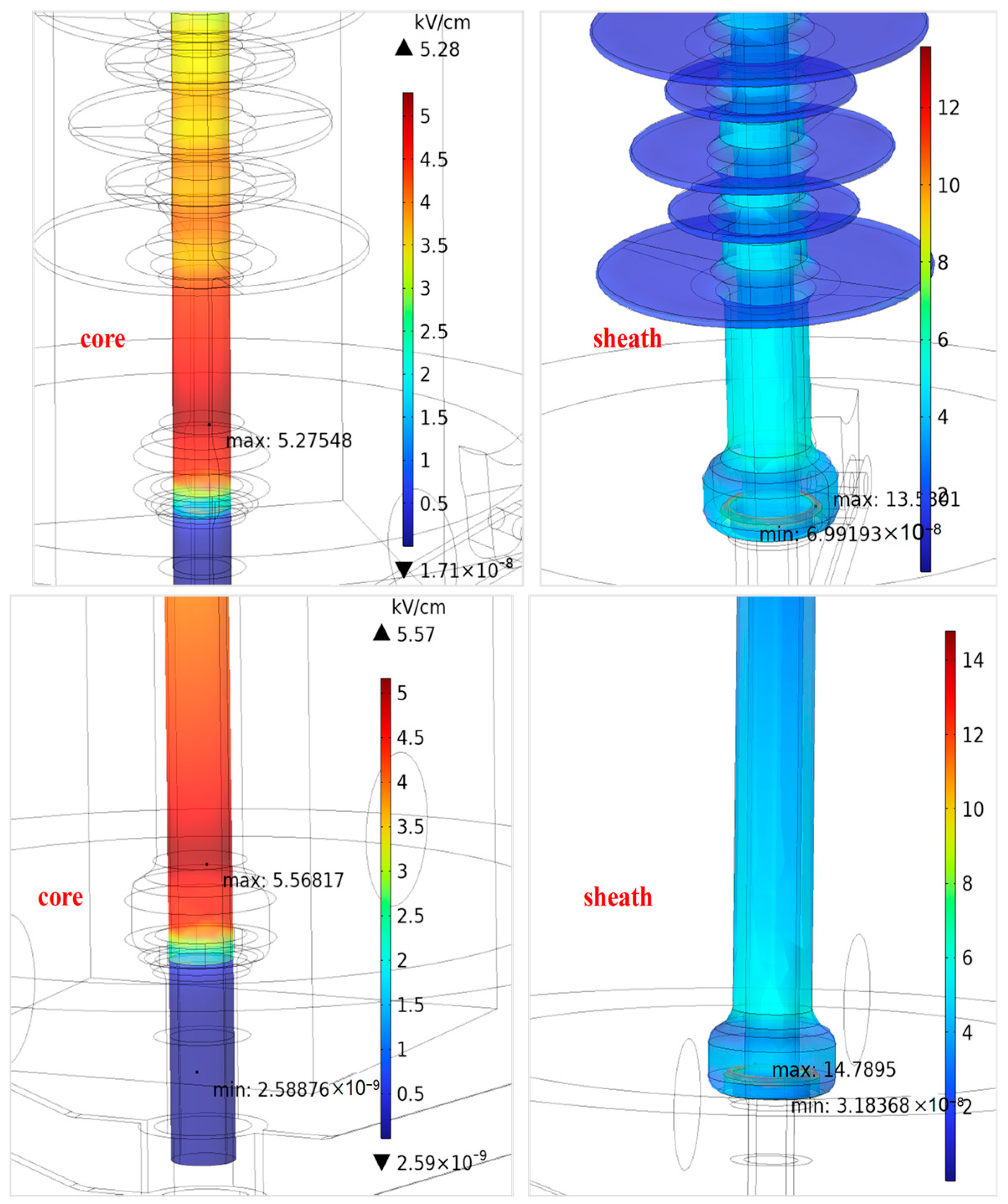

Simulation results indicated that the overall field distribution along the spacer surface was similar in both configurations, exhibiting an approximately symmetric saddle-shaped profile. However, distinct differences appeared near the high-voltage end, where the sheath was directly exposed without shed protection. In this region, the local electric field intensity increased noticeably.

As summarized in

Table 4, the maximum electric field on the sheath surface was 13.53 kV/cm for Configuration 1 and 14.79 kV/cm for Configuration 2. The corresponding values on the core surface were 5.28 kV/cm and 5.57 kV/cm, representing increases of 9.3% and 5.5%, respectively, when the sheds were rearranged to the symmetric layout. The enhancement was confined mainly to a zone extending about 20–30 cm from the high-voltage terminal, as illustrated in

Figure 13.

To further examine the sheath field distribution over the entire spacer, the surface electric field was calculated for both configurations, as illustrated in

Figure 14. The results show that, apart from the high-voltage end, the field patterns along the remaining sheath surface were nearly identical. Both configurations exhibited a generally symmetric saddle-shaped curve, and significant deviations occurred only at the terminal region with or without shed protection. Therefore, the shed arrangement primarily affects the field strength on the high-voltage-end side of the spacer, within a range of approximately 20–30 cm, where the maximum field values differed by about 9.31%. These analyses demonstrate that while the shed configuration has a minor effect on the global field distribution, it distinctly modifies the local field intensity near the end fitting. The results provide quantitative support for subsequent optimization of spacer geometry and end-fitting design.

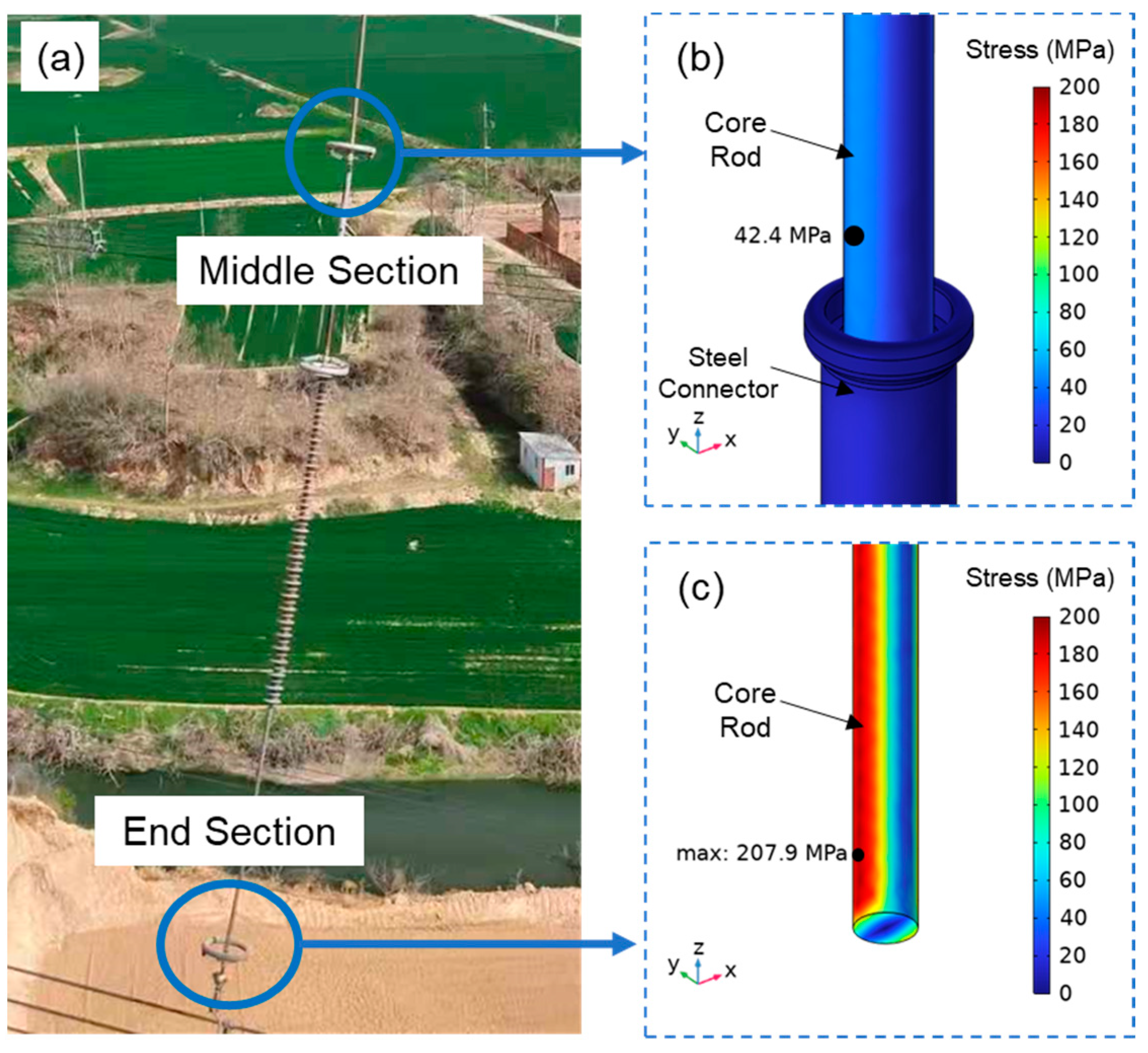

5. Mechanical Stress Simulation Under Flexural Load

To investigate the difference in aging degree between the end and medium section of the interphase bars, mechanical simulation was conducted using COMSOL. Since the modulus of silicone sheath is much lower (2.5 MPa) than the steel (200 GPa) and epoxy core rod (45 GPa), the outer sheath is neglected during mechanical analysis. During the simulation, the interphase bar shown in

Figure 15a is aligned to the Z direction, and the upper boundary is fixed and lower boundary is applied with a 10 N force aligned to +X direction.

The steady-state simulation of mechanical stress is shown in

Figure 15b,c, which firstly indicates that the core rod suffers a stress concentration at the surface of both +X and −X direction, which is a typical pattern for the flexural load. Moreover, even with a relatively small flexural load (10 N), the maximum stress of core rod still reaches to 207.9 MPa at the end section of the interphase bar, which is about 20% of the failure stress (~1000 MPa) of fiber-reinforced epoxy rod. Considering that the mechanical load of on-site interphase bar can be higher and temporally variated, the mechanical stress can also be higher than the simulated value, which may lead to long-term fatigue of the core rod under the combination of electrical, mechanical, thermal and chemical stress. In addition, the stress level at the end part is 4.90 times higher than the value of middle section, indicating that the degradation of the end part is also easier than the middle part, which is also coherent to the electric field simulation results (also demonstrates “end-part concentration”) in

Figure 14.

6. Discussion

The combination of macroscopic observations, microscopic characterization, leakage current tests electric-field simulations, and mechanical stress analysis has provided a coherent understanding of the decay-like fracture mechanism in the 500 kV composite interphase spacer. All aging features indicate that deterioration originates from the interface near the high-voltage end and gradually propagates along the axial direction.

Macroscopic dissection shows sheath cracking and detachment, powdery decay of the exposed core, and a crescent-shaped degradation front. The axial degradation-area ratio confirms that the most severe deterioration occurs within several tens of centimeters of the end fitting. Industrial CT visualizes dense, interconnected cracks and voids forming an axial interfacial network, with some cracks extending into the core and others penetrating the sheath. The defect-volume ratio provides a more representative measure of global damage than 2D cross-sections and shows a spatial gradient consistent with macroscopic observations.

Microscopic and chemical analyses provide additional confirmation of severe interfacial deterioration. The enhancement of Si–OH and C=O peaks in FTIR, together with the increased O/C ratio in XPS, indicates pronounced glass-fiber hydrolysis and epoxy oxidation. SEM observations reveal resin peeling, fiber exposure, and embrittlement, implying significant loss of interfacial bonding. Short samples taken from the HV end exhibit significantly higher resistive current, which drops sharply after drying. It indicated that the increased conductivity mainly results from moisture absorption and the accumulation of soluble ionic species rather than permanent carbonized paths. This behavior is consistent with the crack networks visible in CT images, suggesting that interfacial defects readily form temporary conductive paths under wet conditions.

Electric-field simulations clarify the spatial localization of degradation. While the overall field pattern remains similar across various shed configurations, a marked intensification occurs within the first 20–30 cm of the unprotected high-voltage end, precisely overlapping with the region of most severe deterioration. Such localized field enhancement promotes partial discharge activity, increases dielectric heating, and facilitates moisture migration, thereby accelerating interfacial cracking and resin degradation.

Mechanical analysis further illustrates the vulnerability of the end region. Even under modest lateral loading, the maximum stress at the end reaches about 208 MPa, nearly five times that at the mid-span, indicating pronounced flexural stress concentration. When combined with moisture ingress and intensified electric fields, such stress conditions promote crack initiation and fatigue-related damage.

Overall, the decay-type fracture of the interphase spacer results from the combined effects of mechanical stress, moisture ingress, electric-field concentration, and chemical degradation. The end-fitting region, subjected to repeated bending and lacking effective shed protection, becomes the critical location for crack initiation, moisture accumulation, and heating induced by discharge, ultimately leading to interfacial penetration and failure.

From an engineering perspective, these findings emphasize the necessity of improving the environmental and structural resilience of composite interphase spacers. Enhancing the water resistance of the sheath—through increased thickness or hydrophobic fillers—and optimizing end-fitting and shed configurations to reduce local field concentration can effectively mitigate decay initiation. Furthermore, regular inspections of end regions using nondestructive techniques such as CT or infrared thermography could enable early detection of interfacial degradation, providing practical guidance for preventive maintenance in ultra-high-voltage transmission systems.

7. Conclusions

This study systematically investigates the decay-like fracture of a 500 kV composite interphase spacer through macroscopic inspection, material characterization, and electric-field simulation, clarifying the underlying multi-factor degradation mechanism. The main conclusions are as follows:

The decay-type fracture of the interphase spacer results from the combined action of mechanical, environmental, electrical, and chemical stresses. Long-term bending and torsional loading initiates microcracks at the interface, and the unsheltered terminal region allows moisture to enter and migrate along these cracks. Local electric-field distortion promotes partial discharge and heat accumulation, while humid and thermally stressful conditions accelerate epoxy oxidation and glass-fiber hydrolysis.

The degradation propagates axially along the interface and also extends radially, outward into the sheath and inward into the core, forming penetrating cracks. Compared with two-dimensional cross-sectional measurements, the defect-volume ratio obtained from 3D CT provides a more accurate indication of the overall deterioration level.

Electric field simulations indicated that field enhancement is confined to the first 20–30 cm of the high-voltage end, where sheath and core surface fields rise by 9.3% and 5.5%, corresponding to the observed decay zone. Mechanical analysis shows that a modest 10 N flexural load produces a peak stress of 207.9 Mpa, which is 4.9 times higher than the value of the middle part. The combined, concentrated electric field and mechanical stress can significantly reduce the long-term stability of the end part of the interphase bars.

To enhance long-term reliability, improvements are recommended from material, structural, and operational perspectives: strengthening the sheath’s moisture resistance, optimizing shed arrangement and end-fitting geometry, and reducing in-service torsional stresses, combined with CT or infrared-based nondestructive monitoring. Future work will further validate the effectiveness of these optimization strategies through integrated experimental and simulation studies under practical operating conditions.