Assessment of GNSS-Based InBSAR Deformation Monitoring Using GB-SAR and D-GNSS Measurements

Abstract

1. Introduction

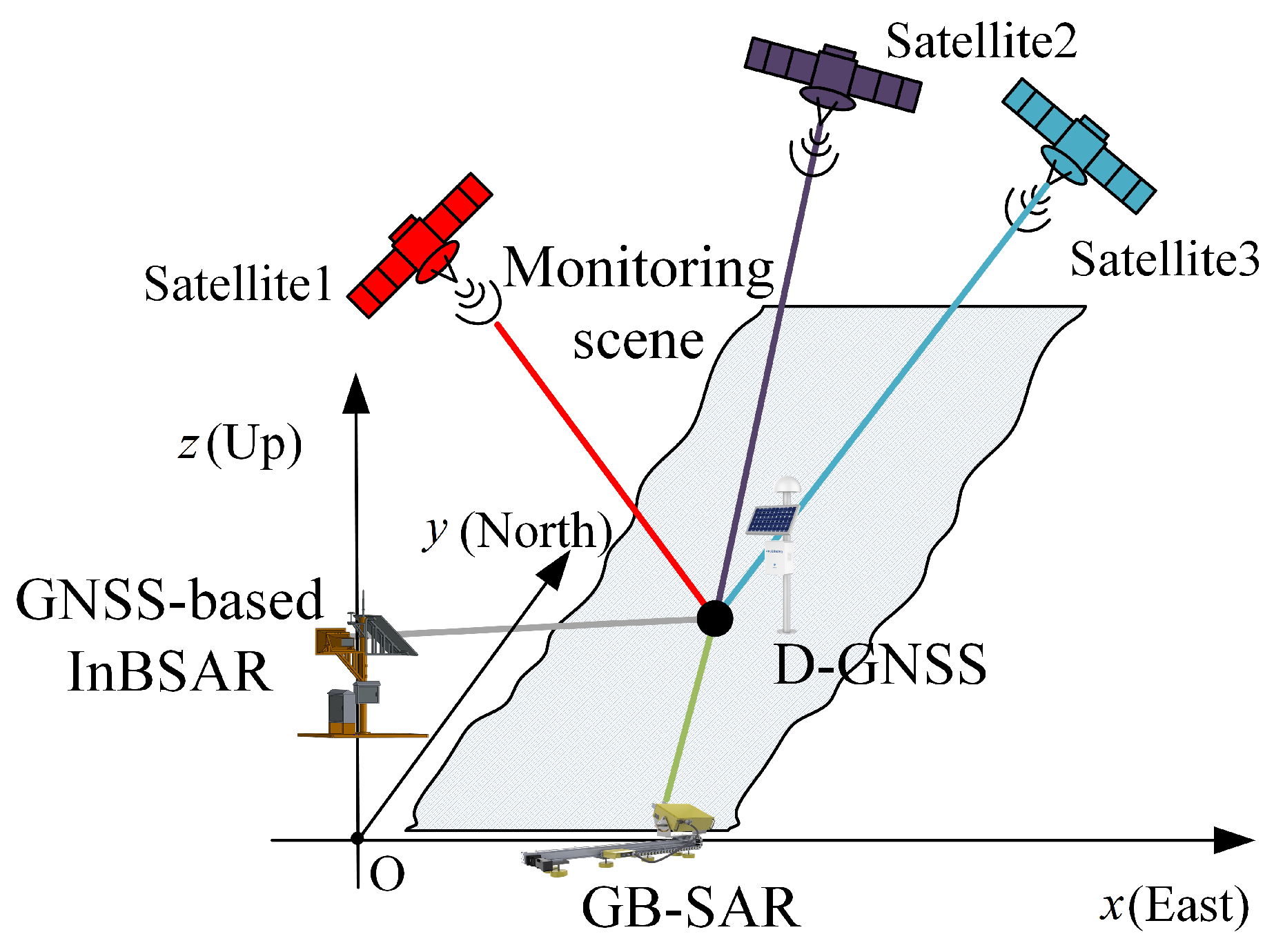

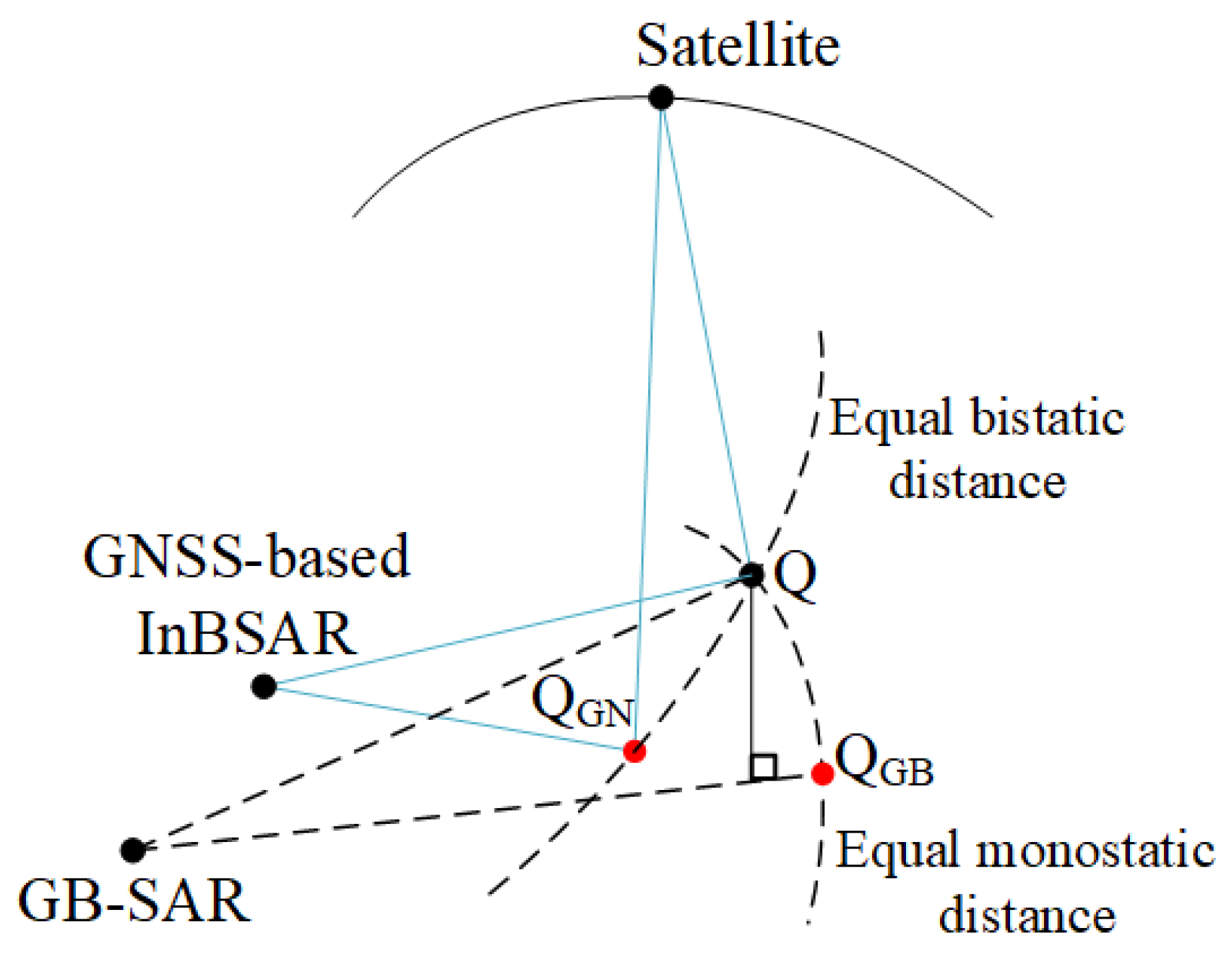

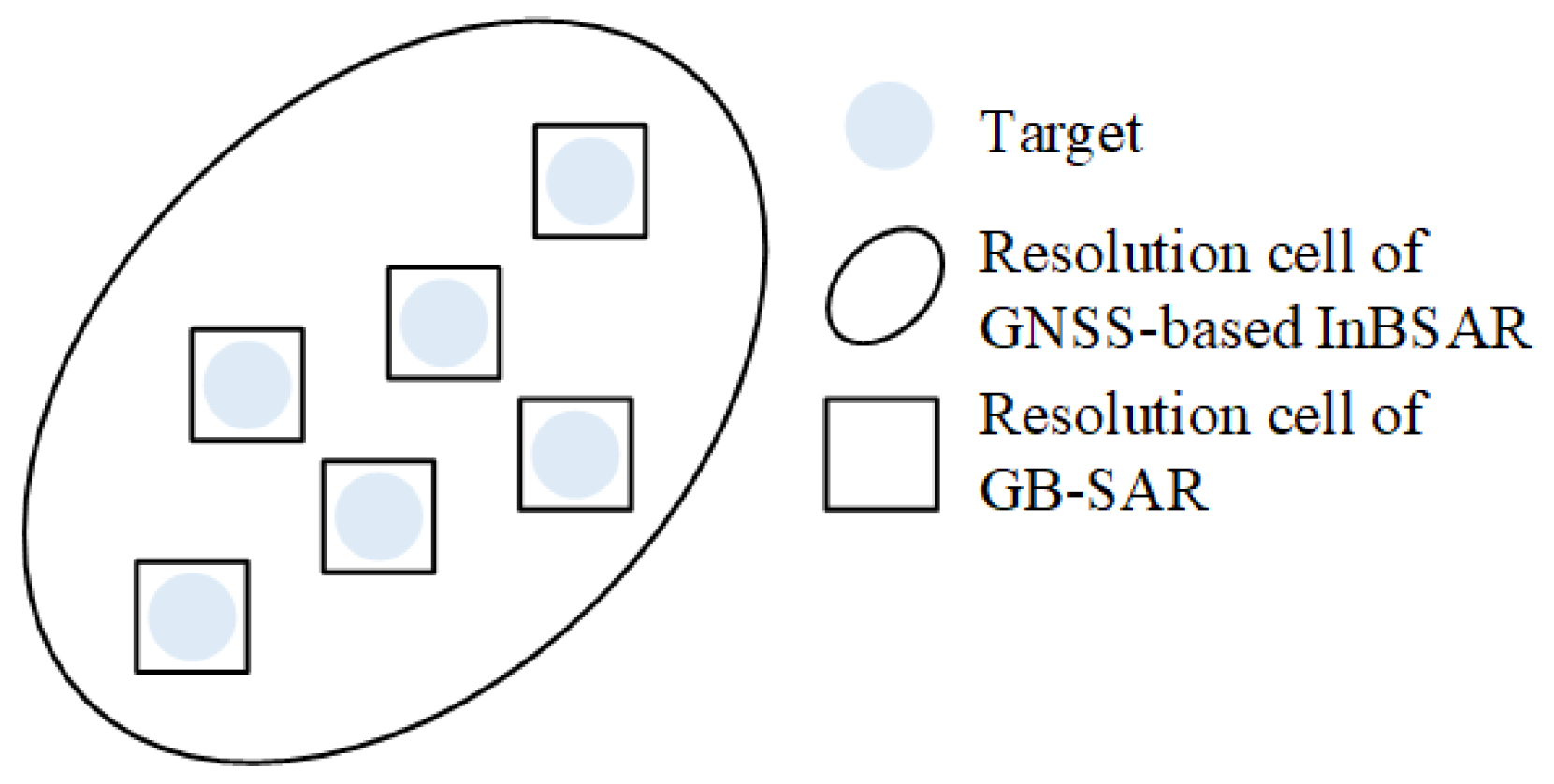

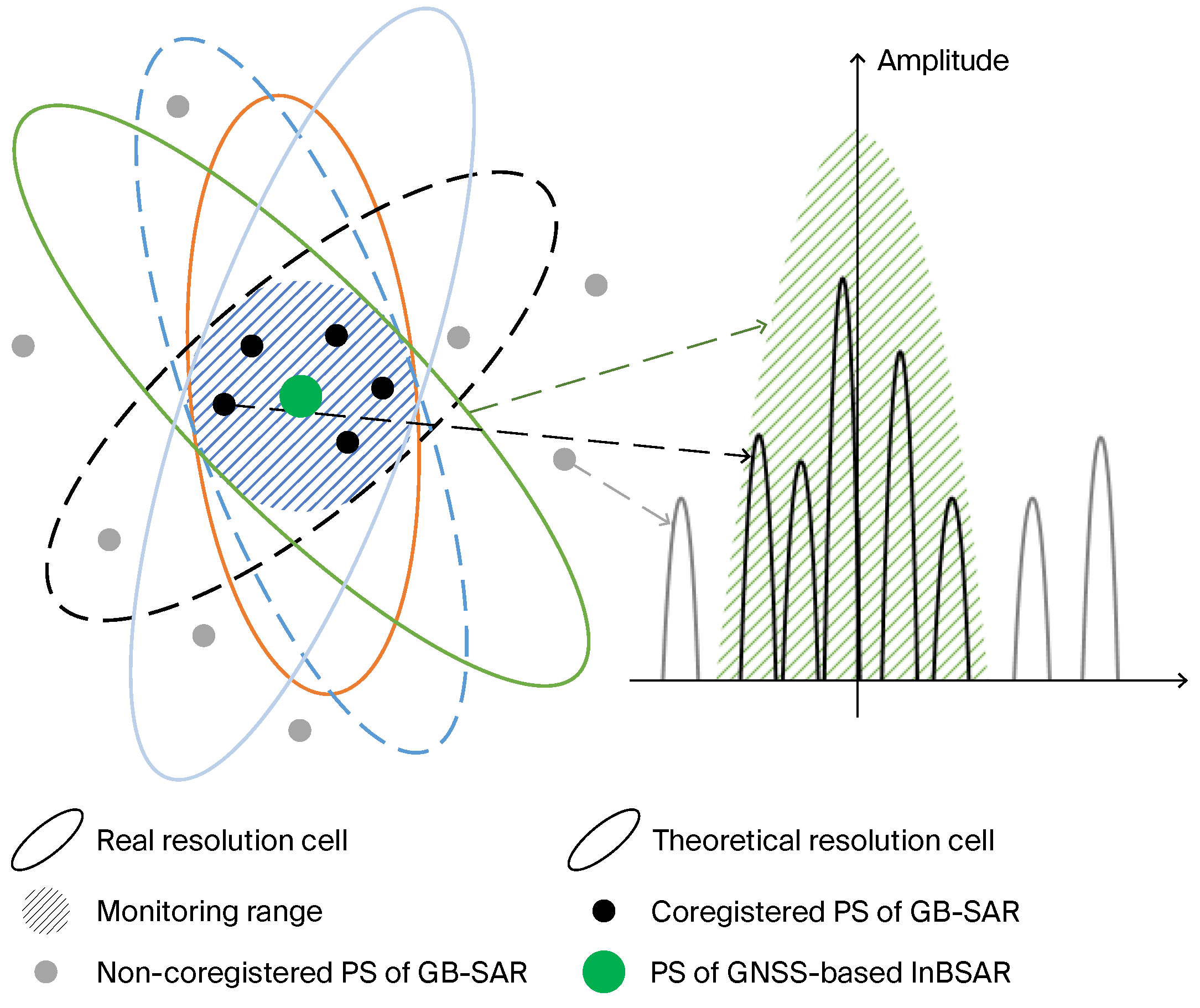

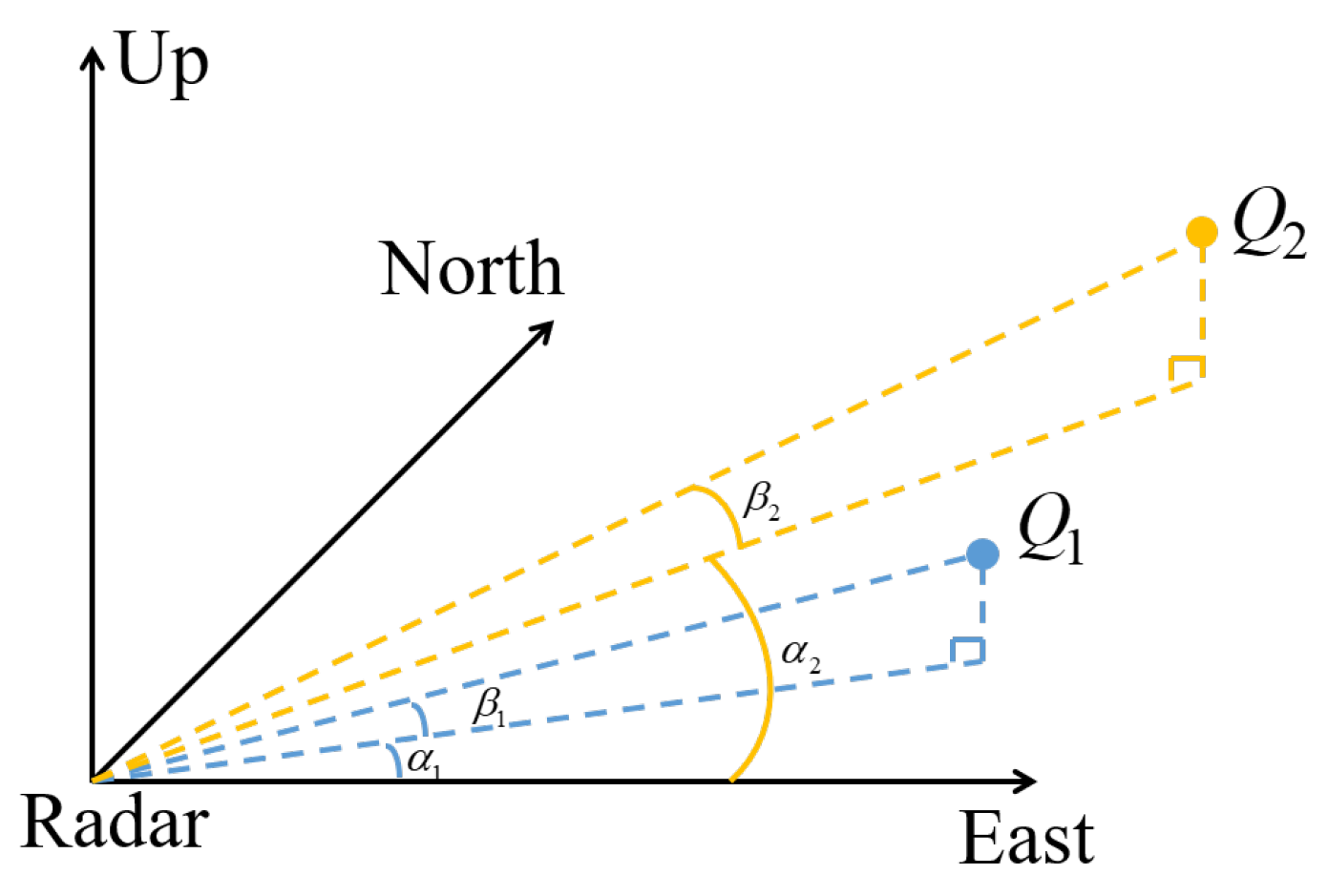

2. Signal Model

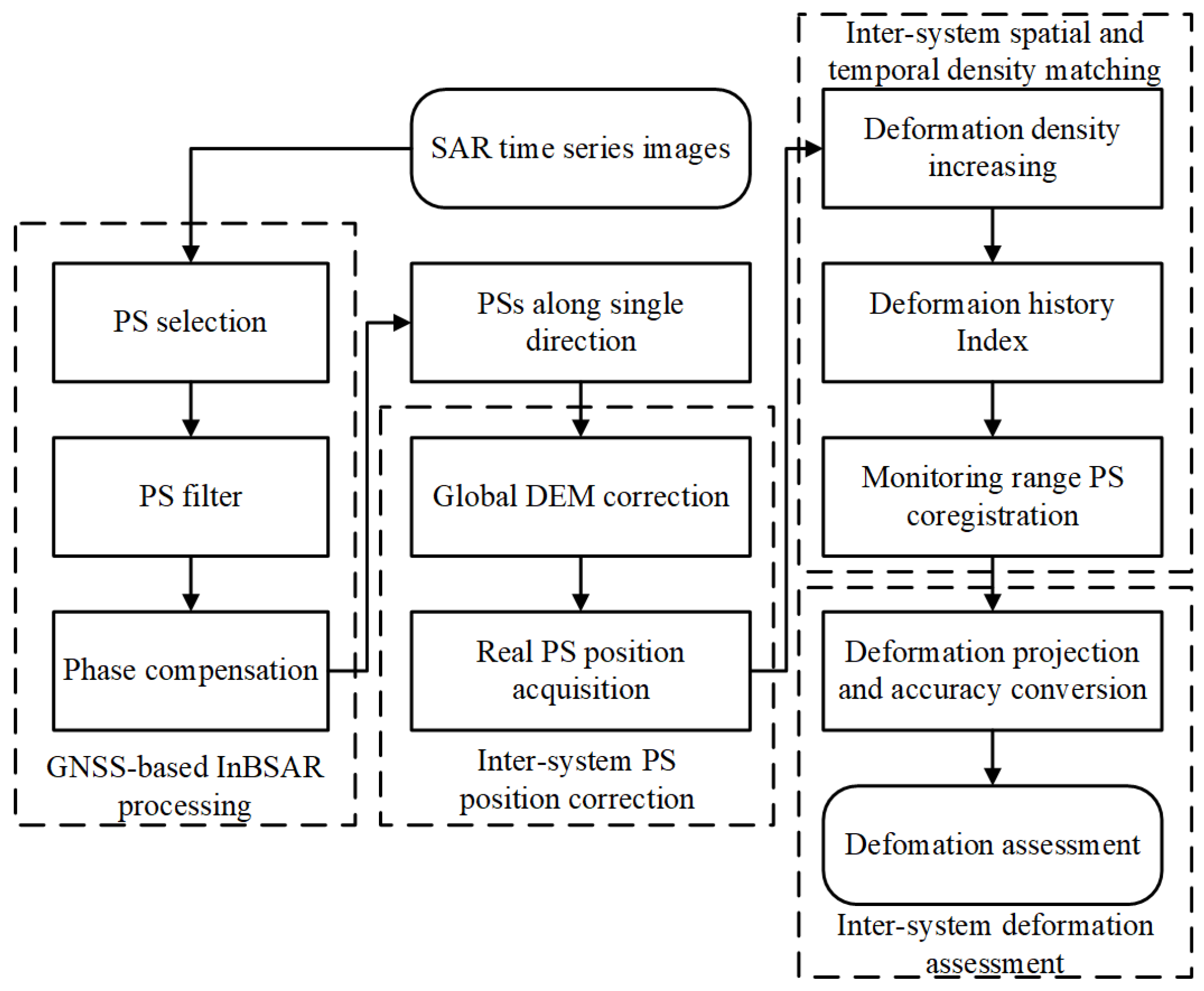

3. Algorithm

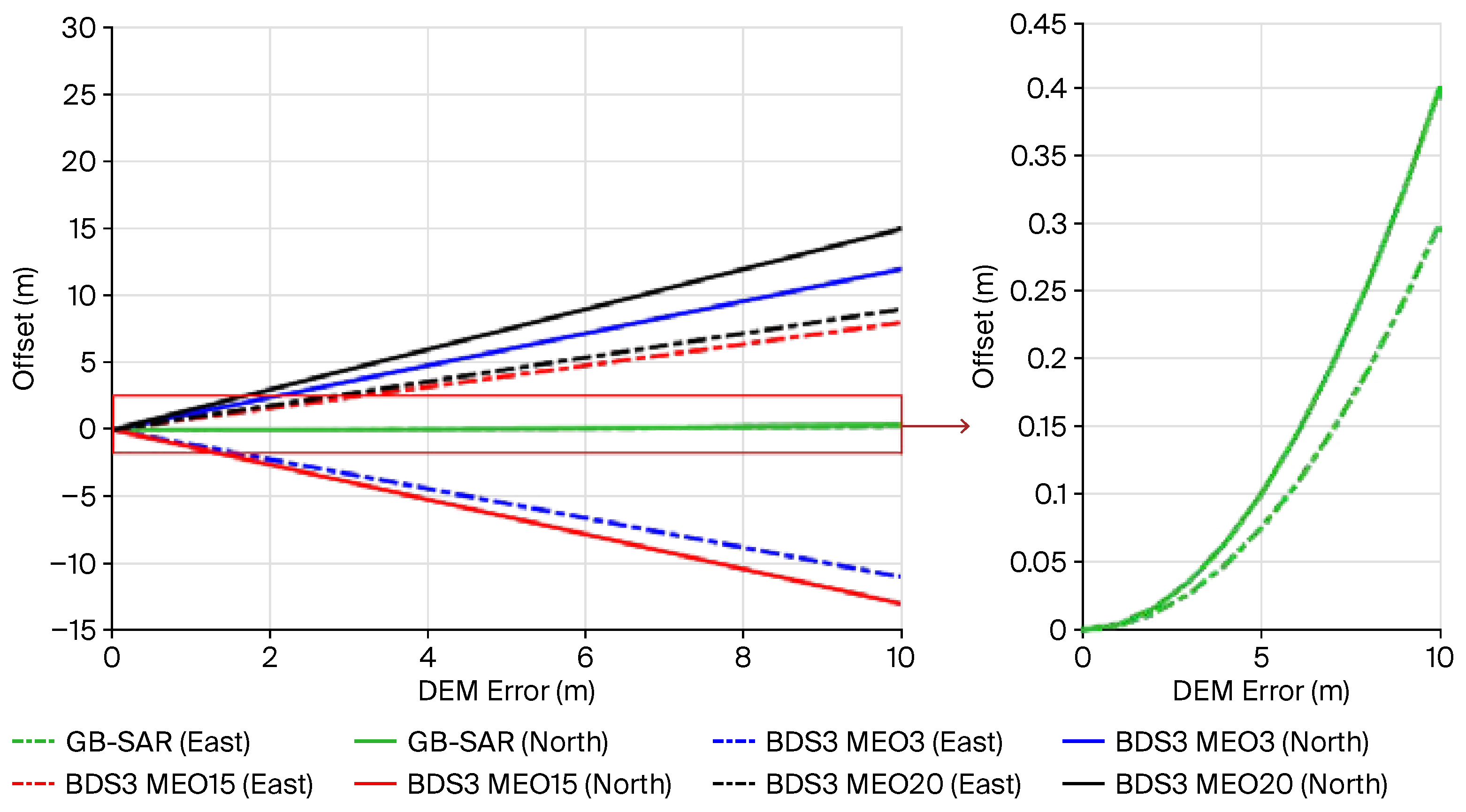

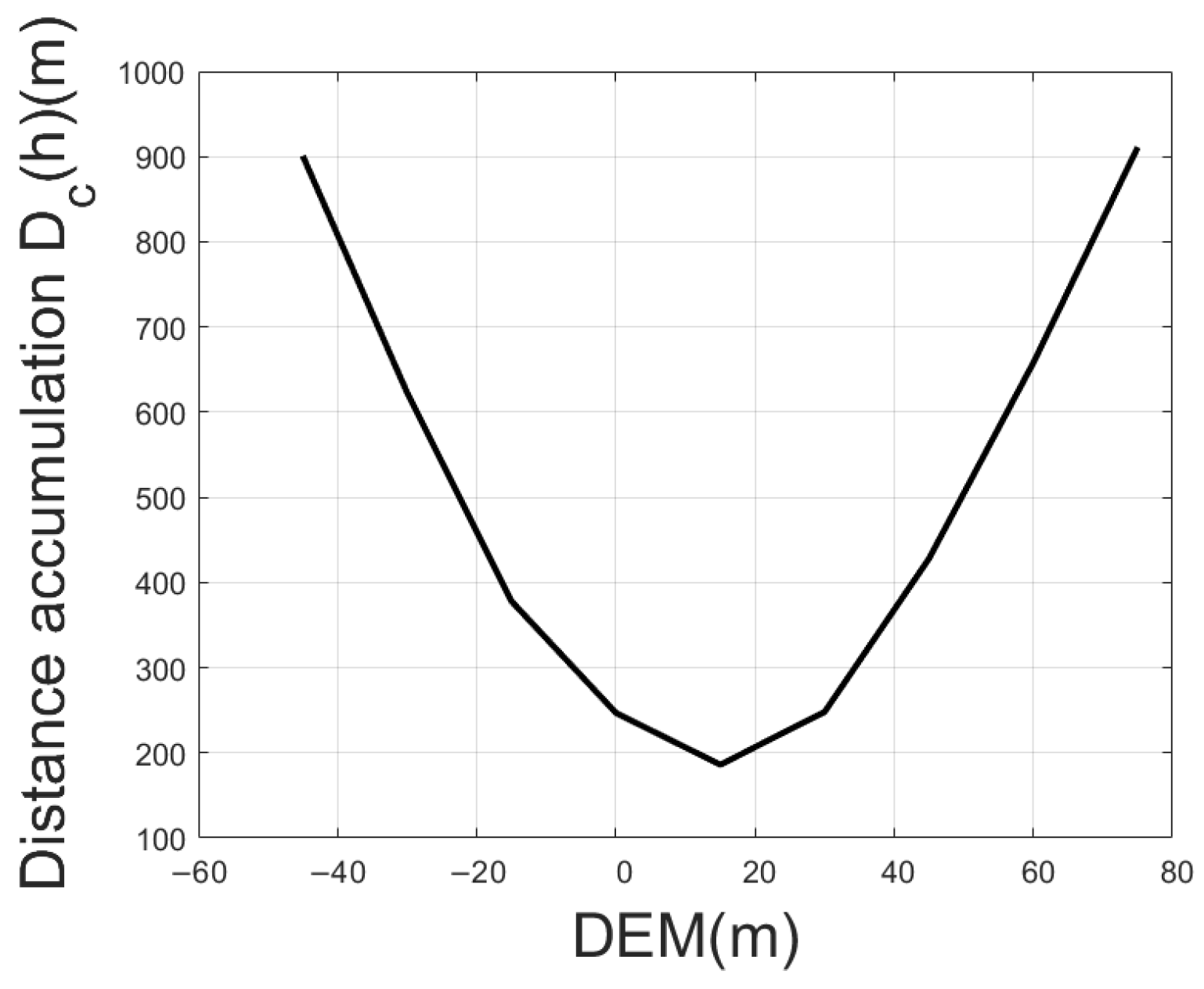

3.1. Inter-System DEM-Error Compensation

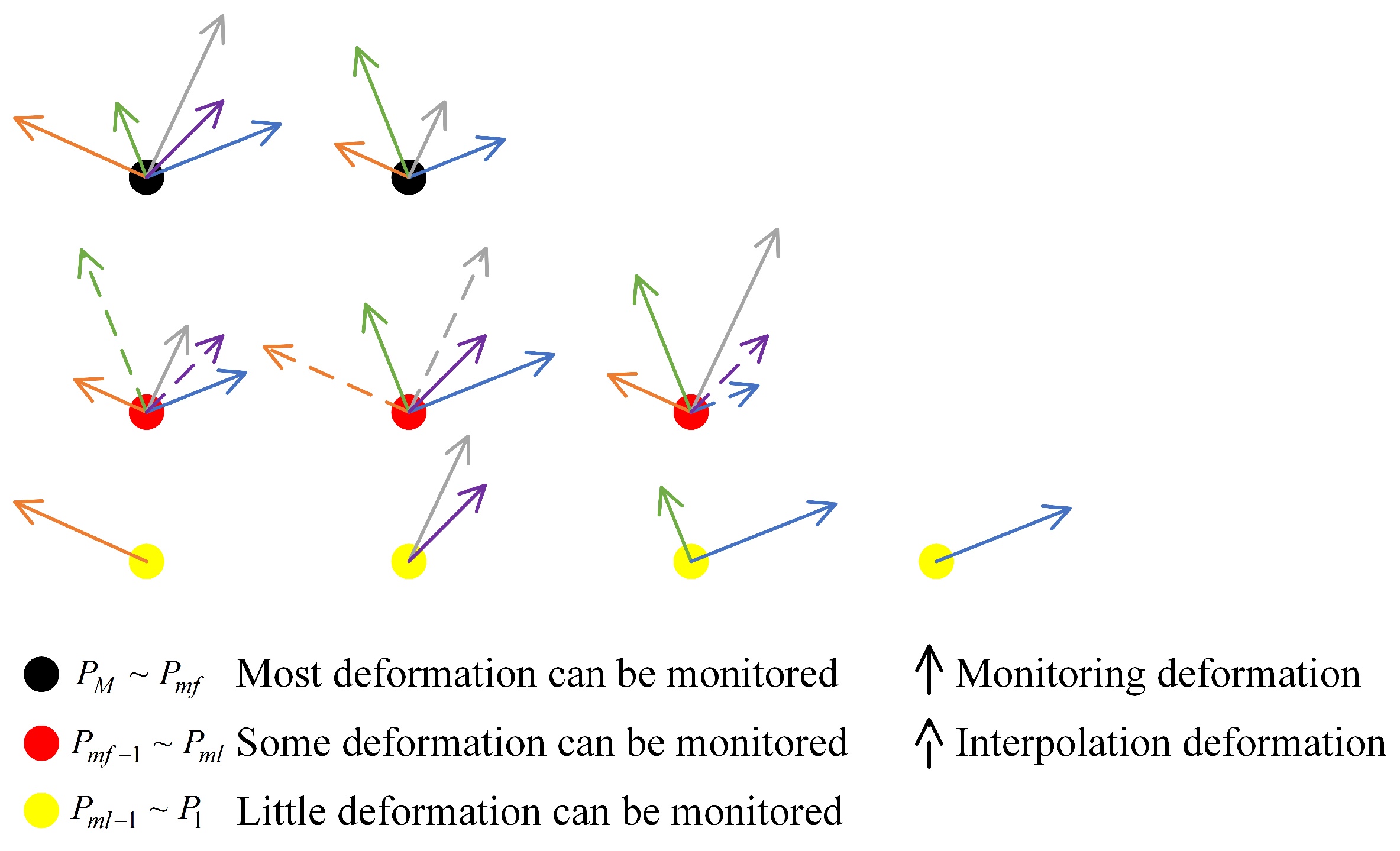

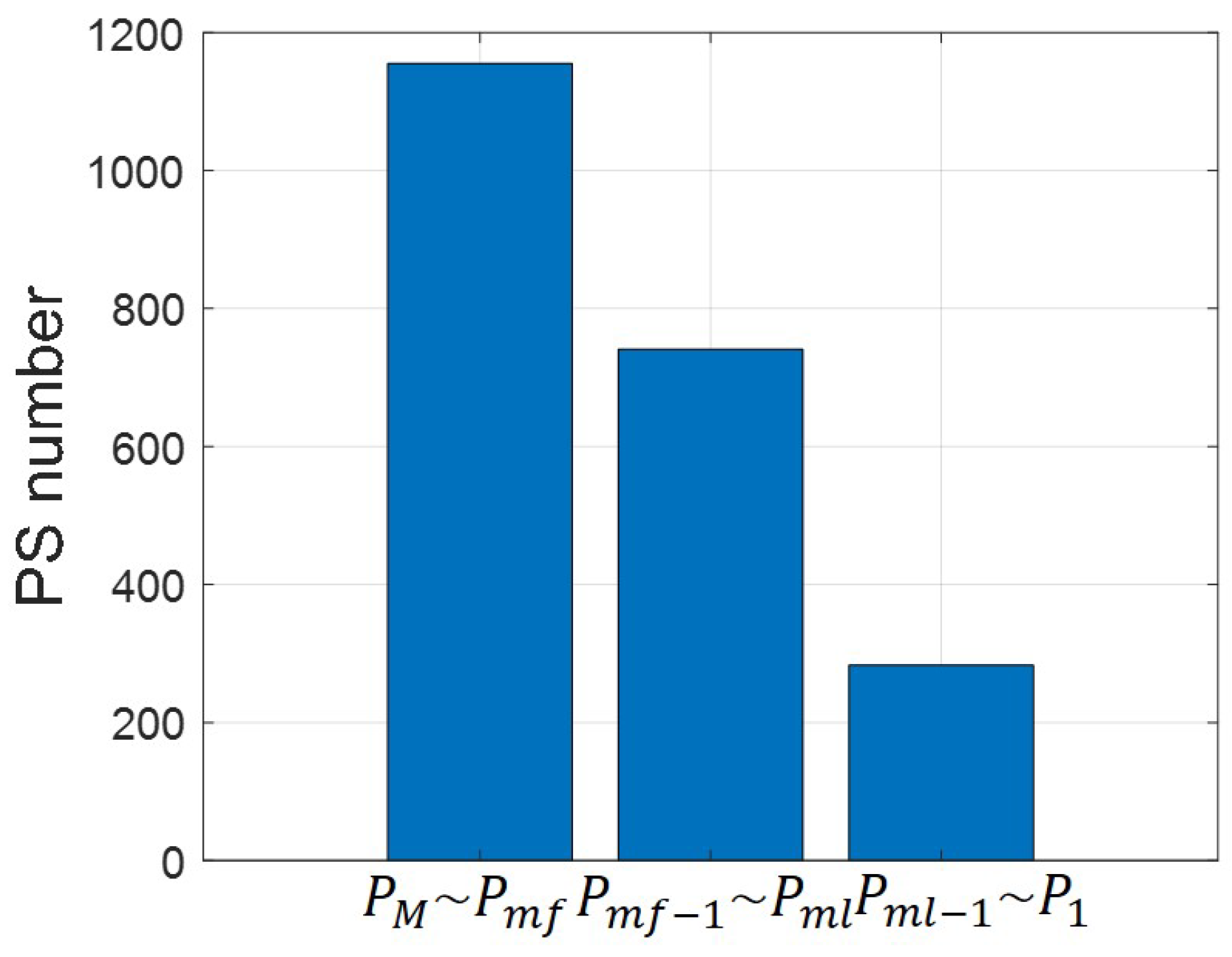

3.2. Inter-System Spatial and Temporal Density Difference Compensation

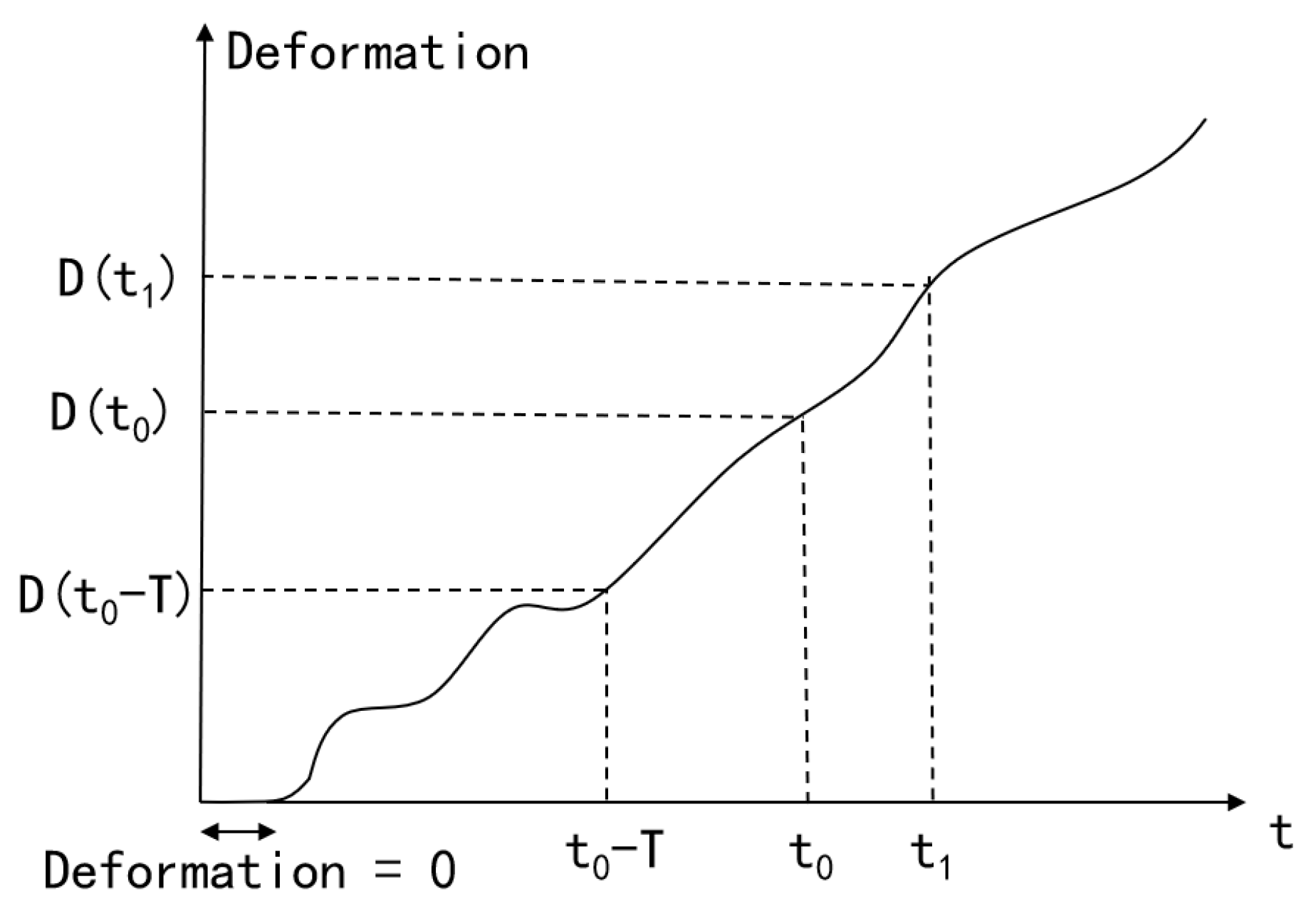

3.3. Inter-System Deformation Information Extraction

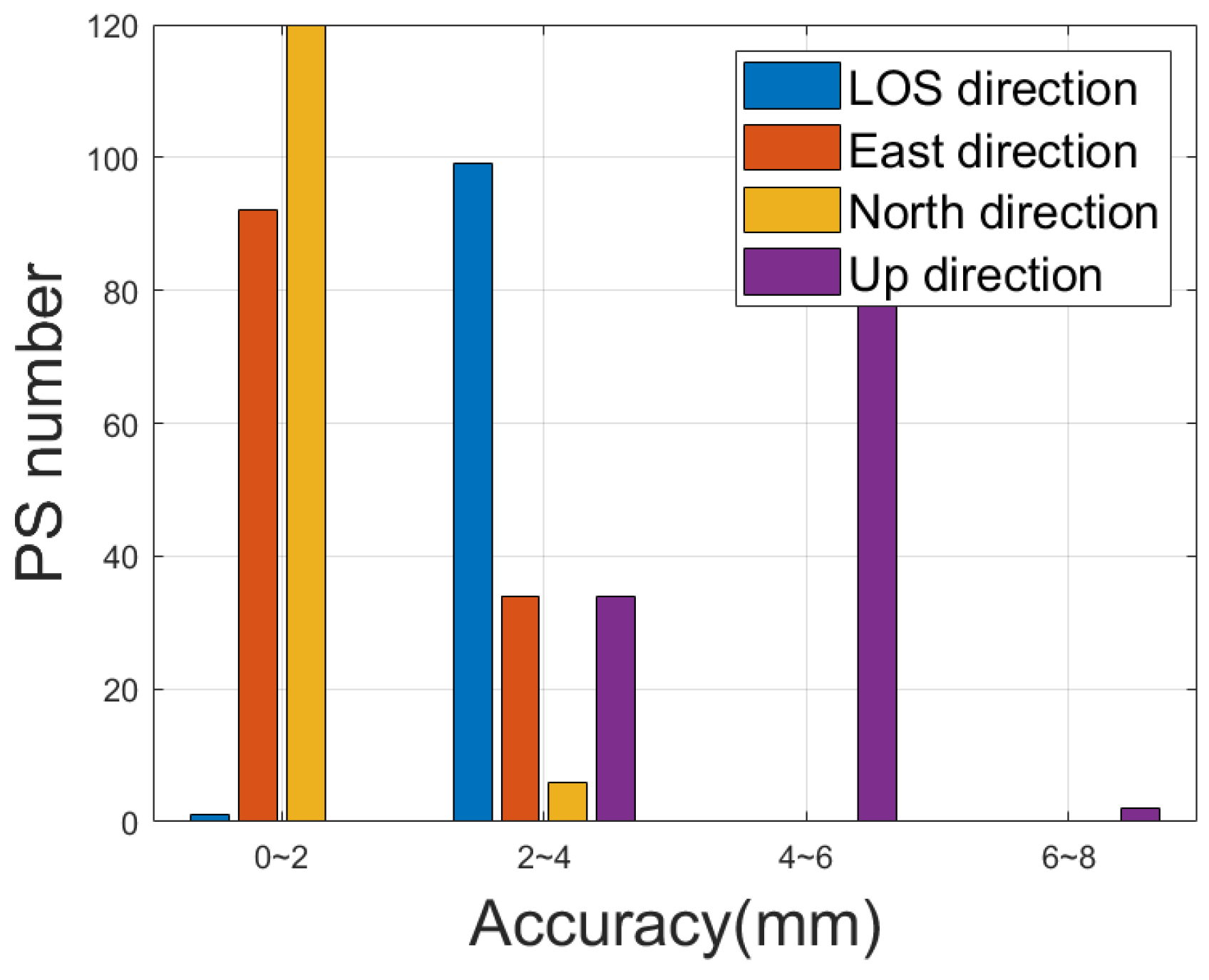

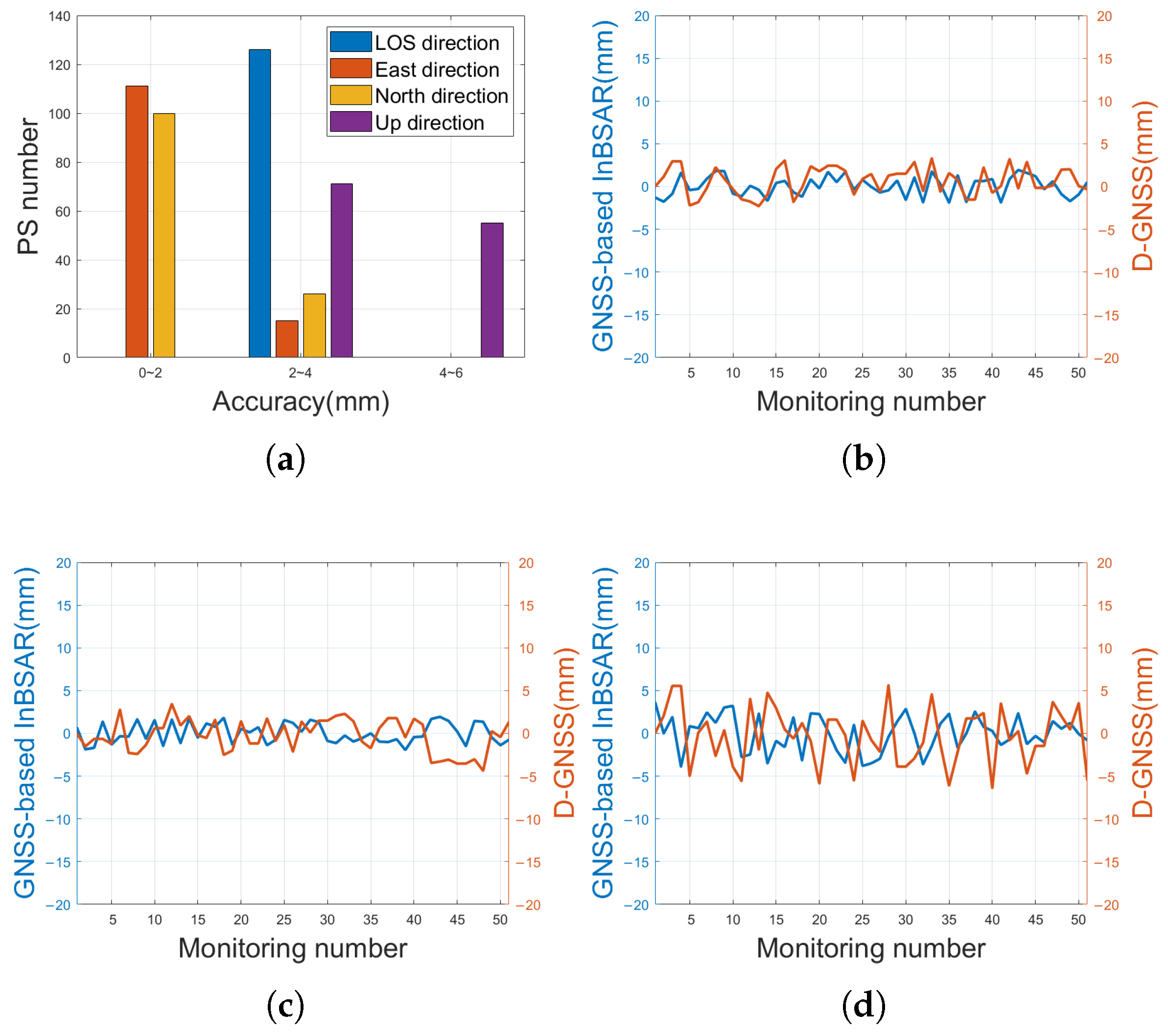

3.4. Inter-System Accuracy Assessment

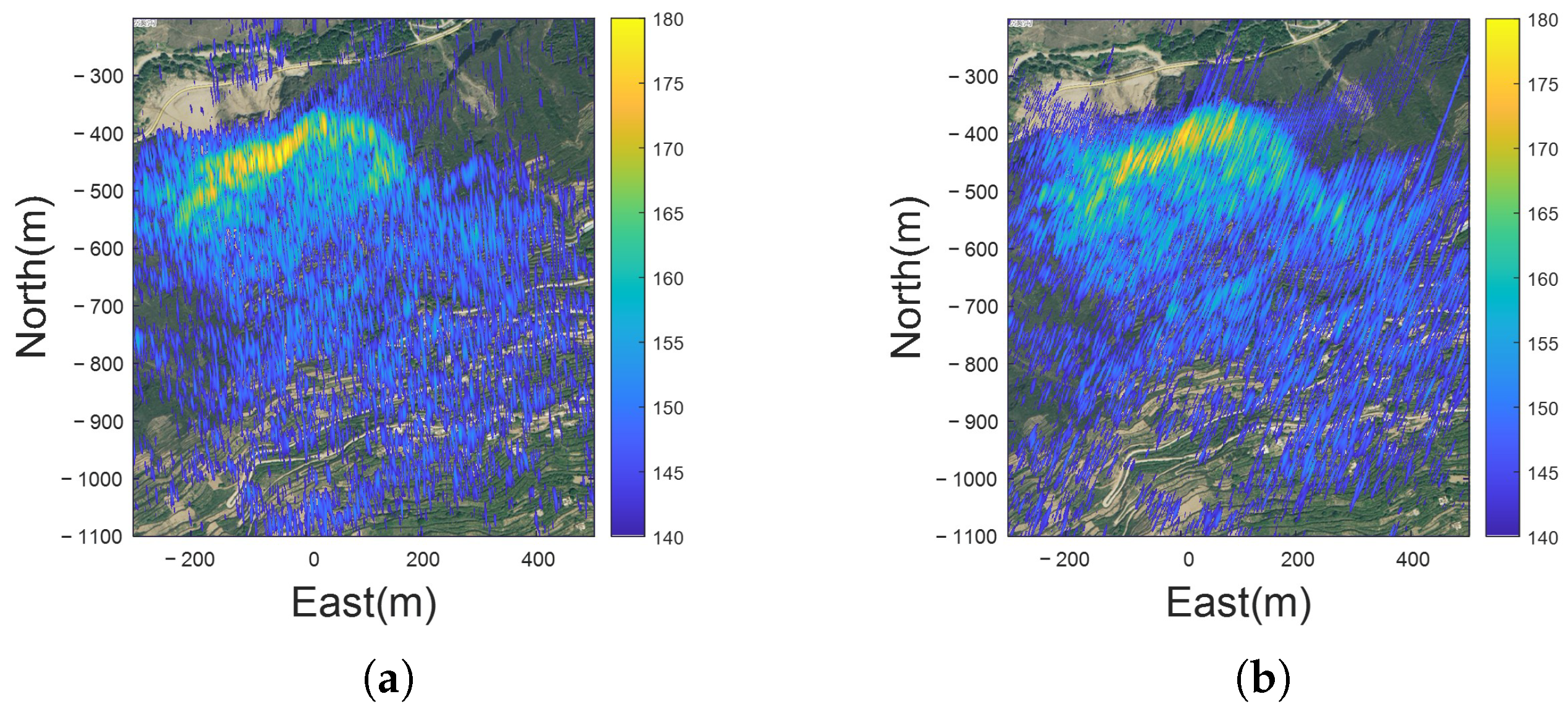

4. Raw Data Processing

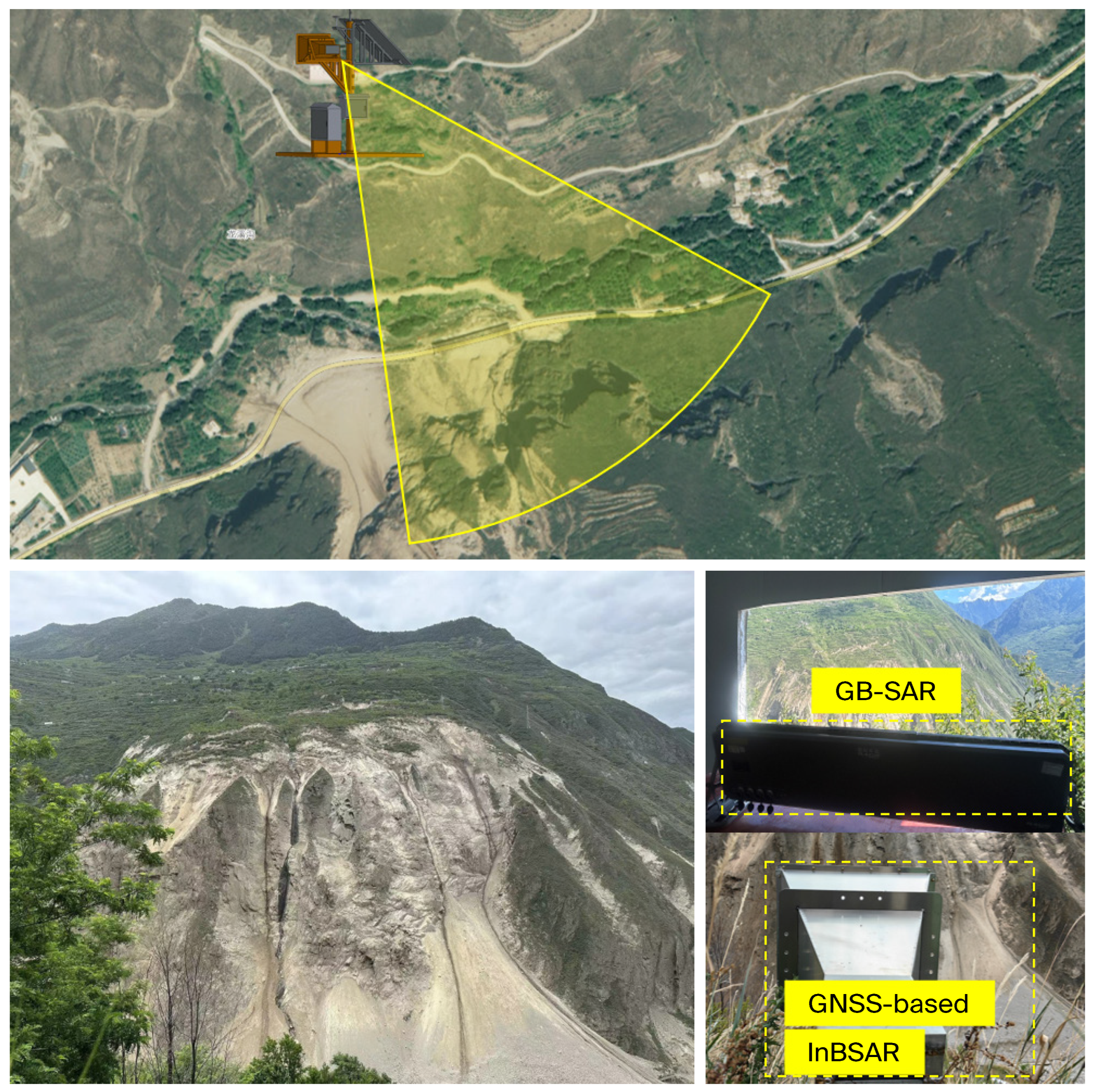

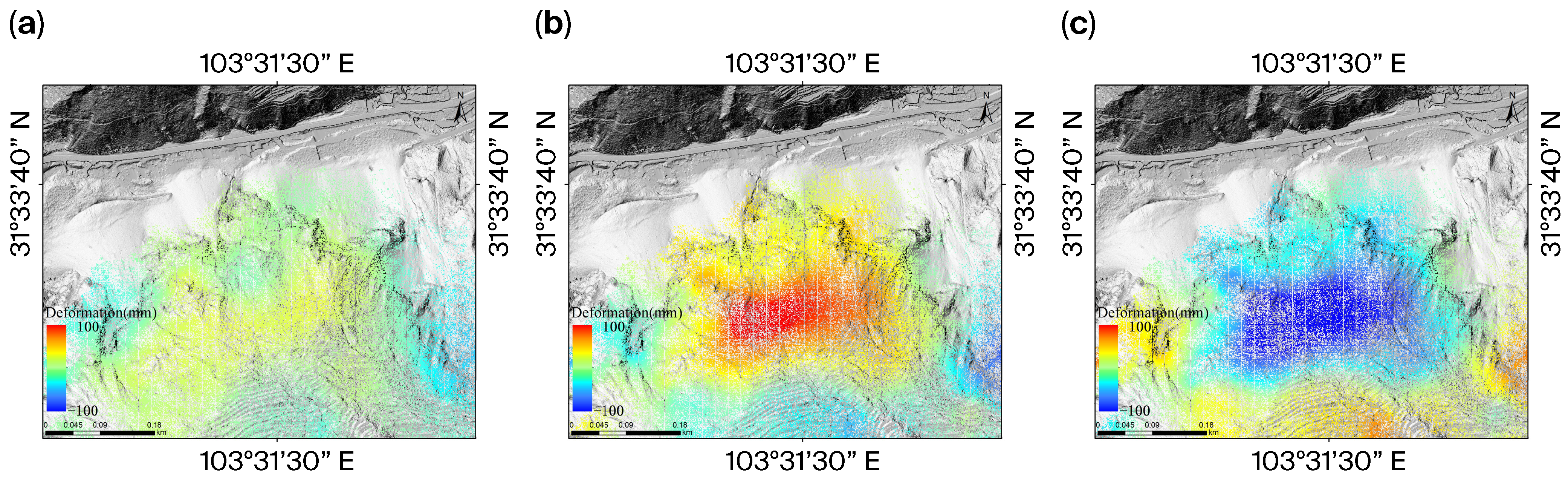

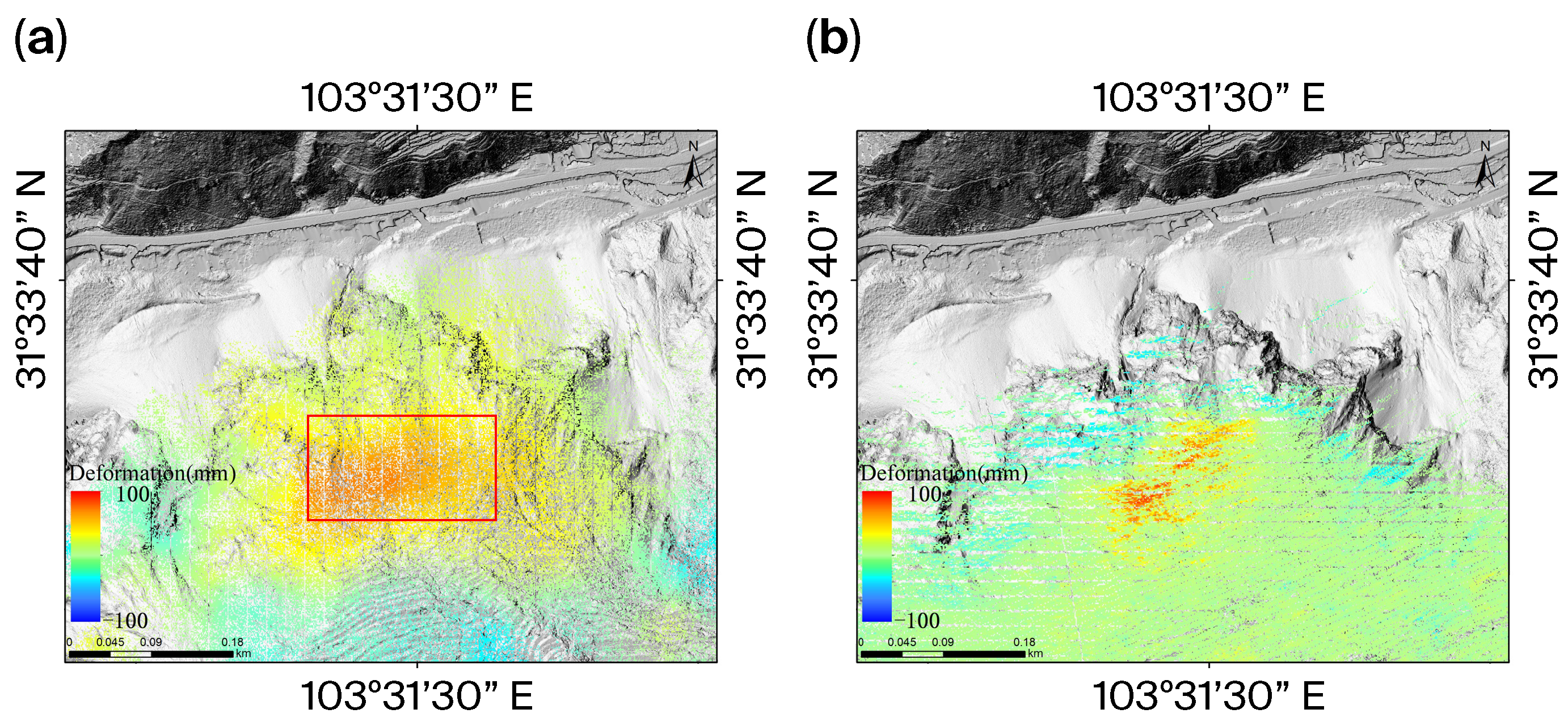

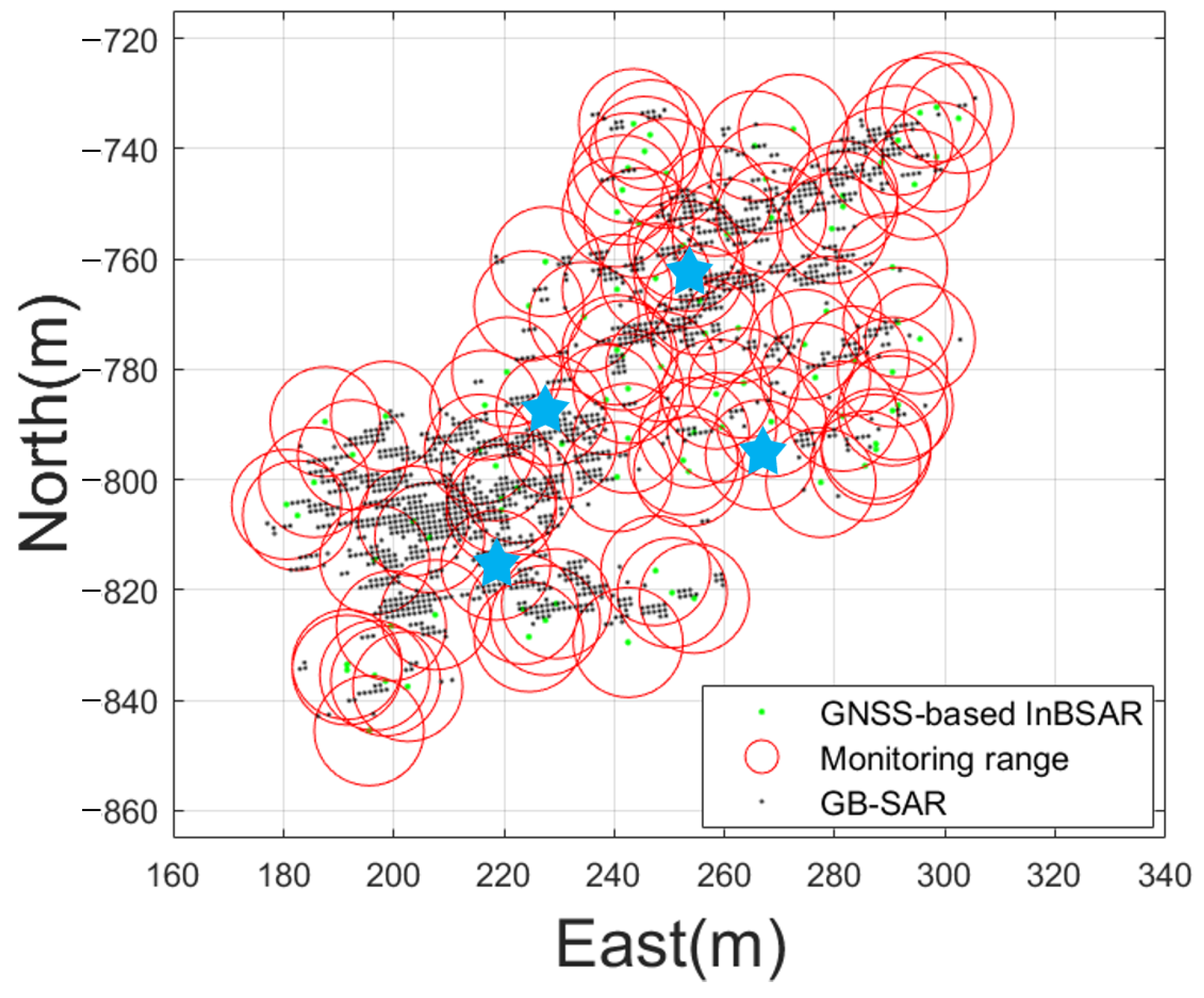

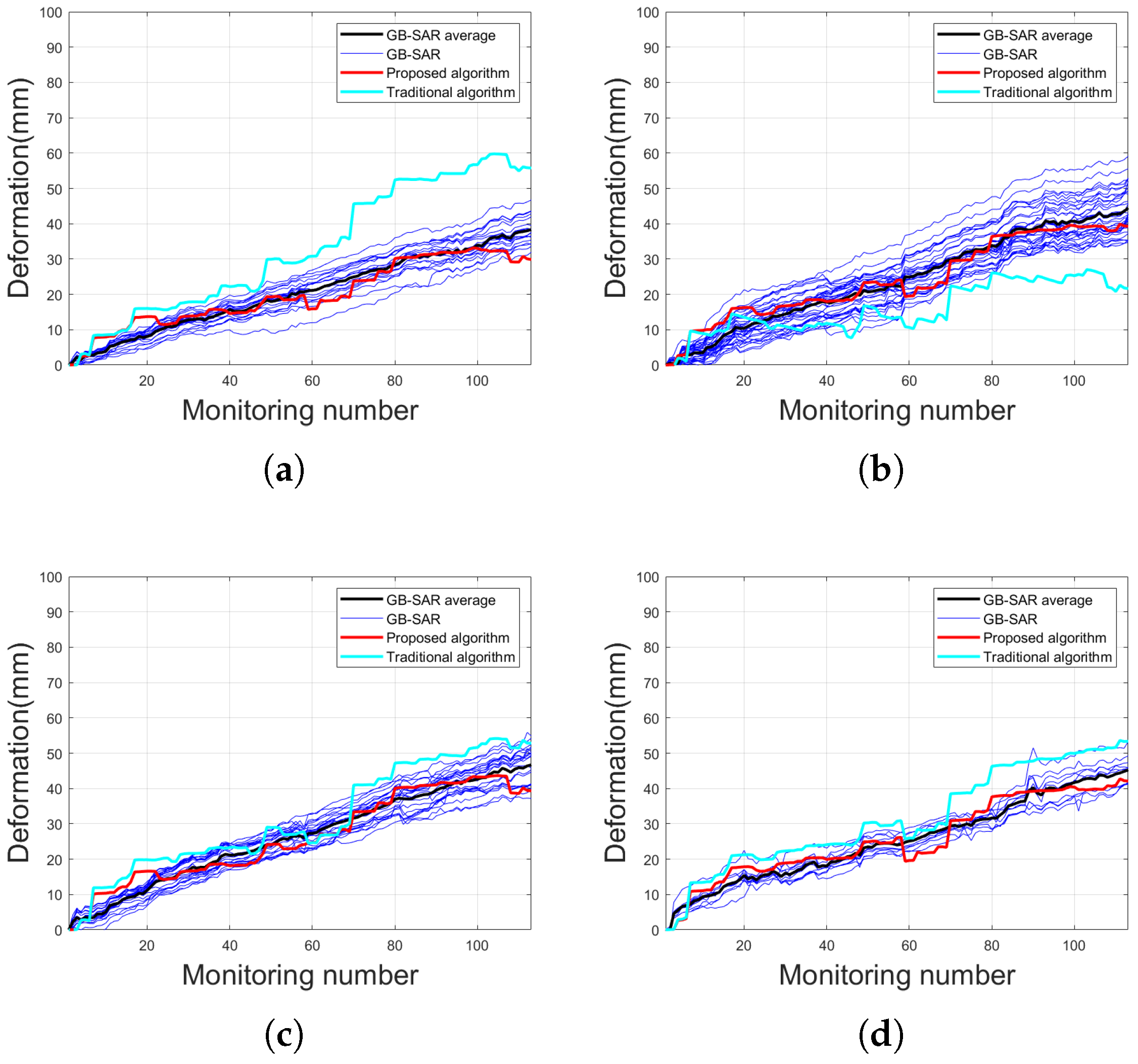

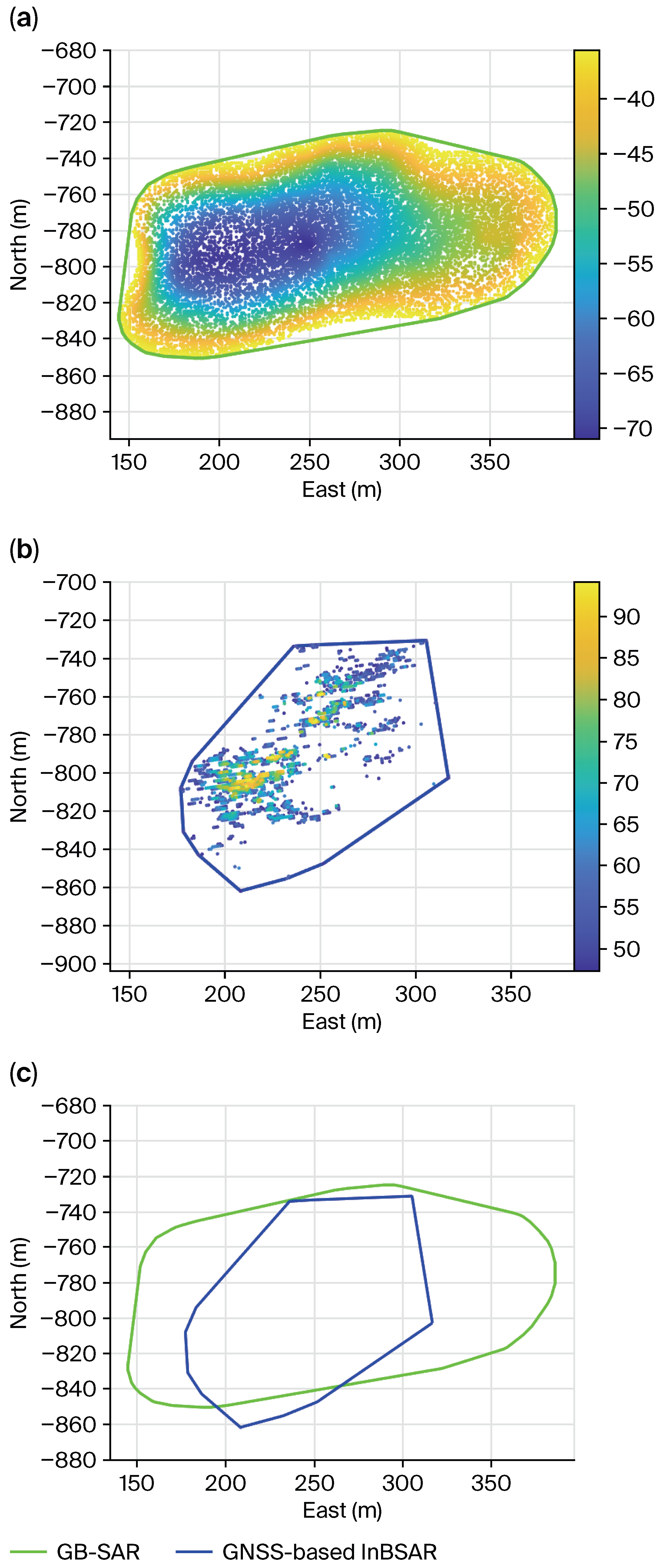

4.1. Natural Landslide Experiment

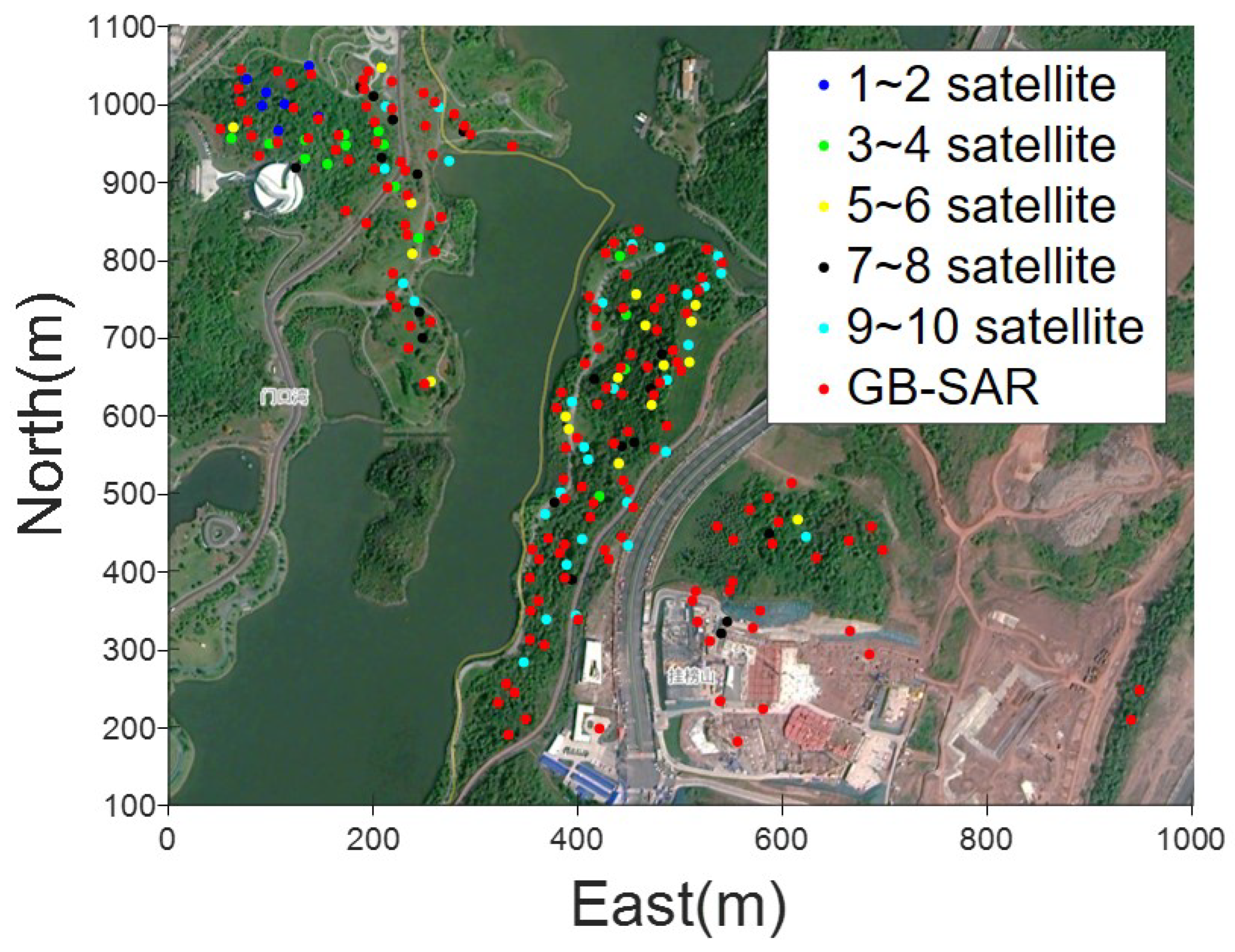

4.2. Artificial Ecological Park Monitoring Experiment

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| GNSS-based InBSAR | global navigation satellite system-based bistatic synthetic-aperture radar |

| GB-SAR | ground-based synthetic-aperture radar |

| D-GNSS | differential global navigation satellite system |

| DEM | digital elevation model |

| PS | persistent scatterer |

| LOS | line of sight |

| InSAR | interferometric synthetic-aperture radar |

| RCS | radar cross-section |

| GAN | generative adversarial network |

References

- Baade, J.; Schmullius, C. TanDEM-X IDEM precision and accuracy assessment based on a large assembly of differential GNSS measurements in Kruger National Park, South Africa. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2016, 119, 496–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Luo, J.; Dong, J.; Mallorqui, J.J.; Liao, M.; Zhang, L.; Gong, J. Sequential polarimetric phase optimization algorithm for dynamic deformation monitoring of landslides. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2024, 218, 84–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Cao, Z.; Li, Q.; Li, Y. Millimeter-Wave Interferometric Synthetic Aperture Radiometer Imaging via Non-Local Similarity Learning. Electronics 2025, 14, 3452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Qi, X.; Huang, L.; Zhang, B.; Zhang, W.; Yan, L. Enhanced BP Algorithm Combined With Semantic Segmentation and Subaperture for Improving Agricultural Scene Image Quality in GEO SAR. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2025, 18, 3043–3056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pastina, D.; Santi, F.; Pieralice, F.; Antoniou, M.; Cherniakov, M. Passive Radar Imaging of Ship Targets With GNSS Signals of Opportunity. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2021, 59, 2627–2642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, B.; Wang, Y.; Yu, H. An Algorithm Measuring Urban Building Heights by Combining the PS-InSAR Technique and Two-Stage Programming Approach Framework. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2023, 16, 7624–7635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Y.; Chen, J.; Wang, P.; Zhou, X. An Image Formation Algorithm for Bistatic SAR Using GNSS Signal With Improved Range Resolution. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 80333–80346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Yu, Z.; Li, J.; Li, C. Focusing Multistatic GEO SAR With Two Stationary Receivers Based on Spectrum Gap Alignment and Recovery. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2024, 17, 1949–1960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Niu, X.; Shi, C. Impact Assessment of Various IMU Error Sources on the Relative Accuracy of the GNSS/INS Systems. IEEE Sensors J. 2020, 20, 5026–5038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, A.; Hu, J.; Sun, Q.; Zhou, D.; Chen, Y.; Zheng, W.; Han, B.; Li, J. Revealing Hidden Deformation Patterns in Shallow Creeping Landslides: A Data-Driven InSAR Phase Filtering Method Addressing Geometric Distortions. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2025, 63, 5214822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Wang, J.; Wu, S.; Gao, Y.; Wang, Y.; Nie, G. Transforming Structural Health Monitoring: Leveraging Multisource Data Fusion With Two-Stage Encoder Transformer for Bridge Deformation Prediction. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2025, 74, 2520613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zhang, C.; Li, Z.; Li, Y.; Cao, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Zhou, J.; He, K.; Wang, X. Asymmetric Deformation Induced by Underground Mining: A Case Study of a Mine in Shaanxi, China. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2025, 18, 17368–17385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Heo, J.; Lee, S.; Jung, Y. SARDIMM: High-Speed Near-Memory Processing Architecture for Synthetic Aperture Radar Imaging. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 7601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santi, F.; Bucciarelli, M.; Pastina, D.; Antoniou, M.; Cherniakov, M. Spatial Resolution Improvement in GNSS-Based SAR Using Multistatic Acquisitions and Feature Extraction. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2016, 54, 6217–6231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santi, F.; Antoniou, M.; Pastina, D. Point Spread Function Analysis for GNSS-Based Multistatic SAR. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2015, 12, 304–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horn, B.K.P. Round-Trip Time Ranging to Wi-Fi Access Points Beats GNSS Localization. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 7805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; He, X. Evaluation of Multisignal and Multiorbit Multipath Reflectometry of BeiDou Navigation Satellite System. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2023, 20, 1503305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Li, Z.; Mao, W.; Shi, Q.; Lin, Q. Fusion of InSAR and GNSS Based on Adaptive Spatio-Temporal Kalman Model for Reconstructing High Spatio-Temporal Resolution Deformation. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2024, 17, 19616–19626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capolupo, A. Improving the Accuracy of Global DEM of Differences (DoD) in Google Earth Engine for 3-D Change Detection Analysis. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2021, 14, 12332–12347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Wang, M.; Chang, B.; Li, Y. Multi-Level Interpolation-Based Filter for Airborne LiDAR Point Clouds in Forested Areas. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 41000–41012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Xiang, W.; Chen, W. SAR Filtering Algorithm for Detecting Terrain Relief Targets. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2023, 20, 4011905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, X.; Zhang, L.; Lu, Z.; Liang, H. Robust Stacking InSAR: Mitigating DEM Errors for Precise Deformation Rate Retrieval. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2025, 63, 5218613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dörr, N.; Schenk, A.; Hinz, S. Fully Integrated Temporary Persistent Scatterer Interferometry. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2022, 60, 4412815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navneet, S.; Kim, J.W.; Lu, Z. A New InSAR Persistent Scatterer Selection Technique Using Top Eigenvalue of Coherence Matrix. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2018, 56, 1969–1978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Zeng, X.; Gao, J.; Wang, Z. Deformation Field Formation Algorithm Based on Modified Kriging Interpolator in GNSS-Based InBSAR. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2024, 21, 4009405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Li, J.; Liu, Q.; Zhang, Z.; Dong, Y. Comparative Study of Fractional Vegetation Cover Estimation Methods Based on Fine Spatial Resolution Images for Three Vegetation Types. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2022, 19, 2508005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Yang, X.; Pu, Q.; Jeon, G.; Liu, K. PSAM: Progressive Spatial Adaptive Matching for Reference-Based Super Resolution. IEEE Signal Process. Lett. 2023, 30, 1717–1721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Zhang, H.; Huang, H.; Zhang, L. Remote Sensing Image Spatiotemporal Fusion via a Generative Adversarial Network With One Prior Image Pair. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2022, 60, 5528117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Y.; Hu, C.; Tian, W.; Zhao, Z. 3-D Deformation Measurement Based on Three GB-MIMO Radar Systems: Experimental Verification and Accuracy Analysis. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2021, 18, 2092–2096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Fan, X.; Zhang, T.; Liu, Q. GNSS-Based SAR Interferometry for 3-D Deformation Retrieval: Algorithms and Feasibility Study. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2018, 56, 5736–5748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huo, T.; He, Y.; Zhang, L.; Yang, W.; Tang, J.; Zhang, Q.; Lu, J.; Zhang, Y. GLER-BiGRUnet: A Surface Deformation Prediction Model Fusing Multiscale Features of InSAR Deformation Information and Environmental Factors. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2024, 17, 14848–14861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, S.; Zhang, Z.; Li, Z.; Liu, X.; Chen, Q. Prediction of Mining-Induced 3-D Deformation by Integrating Single-Orbit SBAS-InSAR, GNSS, and Log-Logistic Model (LL-SIG). IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2023, 61, 5222213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Zhu, Y.; Deng, Z.; Zhao, Y. A Satellite Selection Algorithm for GNSS-R InSAR Elevation Deformation Retrieval. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2025, 22, 4500305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Transmitter | Azimuth () | Pitch () |

|---|---|---|

| BDS3 MEO3 | 331 | 59 |

| BDS3 MEO15 | 217 | 46 |

| BDS3 MEO20 | 276 | 24 |

| GB-SAR | 30 | 30 |

| Satellite Count | East (mm) | North (mm) | Up (mm) | PS Count |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1∼2 | 6.1 | 7.3 | 14.7 | 7 |

| 3∼4 | 3.1 | 3.5 | 8.4 | 15 |

| 5∼6 | 2.3 | 2.4 | 5.9 | 17 |

| 7∼8 | 1.9 | 2.0 | 5.1 | 19 |

| 9∼10 | 1.9 | 2.0 | 5.1 | 19 |

| Transmitter | Azimuth Resolution | Range Resolution |

|---|---|---|

| BDS3 MEO3 | 4.3 m | 9.9 m |

| BDS3 MEO15 | 4.9 m | 8.7 m |

| BDS3 MEO20 | 3.4 m | 9.4 m |

| GB-SAR | 7.5 m (about 1000 m) | 0.15 m |

| Transmitter | Azimuth () | Pitch () | East Offset (m) | North Offset (m) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BDS2 IGSO2 | 55 | 81 | 13 | −15 |

| BDS2 IGSO3 | 189 | 60 | −14 | 16 |

| BDS2 IGSO5 | 335 | 75 | 12 | 18 |

| BDS2 IGSO6 | 197 | 52 | 16 | −12 |

| BDS3 MEO1 | 110 | 38 | 13 | 15 |

| BDS3 MEO12 | 246 | 40 | 12 | 17 |

| BDS3 MEO16 | 348 | 60 | −19 | 12 |

| BDS3 MEO22 | 291 | 29 | 12 | 12 |

| BDS3 MEO26 | 77 | 32 | 14 | −13 |

| BDS3 ME9 | 69 | 29 | 14 | −16 |

| GB-SAR | 265 | 15 | 1 | 3 |

| Type | Dimension | Reference | Accuracy (mm) |

|---|---|---|---|

| GB-SAR | 1D | 0 | 0.2 |

| GNSS-based InBSAR | 1D | 0 | 2.5 |

| GNSS-based InBSAR | 1D | GB-SAR | 2.6 |

| GNSS-based InBSAR | 3D | GB-SAR | 1.6, 1.7, 4.0 |

| D-GNSS | 3D | 0 | 1.7, 1.9, 3.3 |

| GNSS-based InBSAR | 3D | 0 | 1.2, 1.2, 2.1 |

| GNSS-based InBSAR | 3D | D-GNSS | 2.2, 2.5, 4.3 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Xu, Z.; Wang, Z.; Deng, Y.; Li, Y.; Yao, D.; Liu, F. Assessment of GNSS-Based InBSAR Deformation Monitoring Using GB-SAR and D-GNSS Measurements. Electronics 2025, 14, 4749. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14234749

Xu Z, Wang Z, Deng Y, Li Y, Yao D, Liu F. Assessment of GNSS-Based InBSAR Deformation Monitoring Using GB-SAR and D-GNSS Measurements. Electronics. 2025; 14(23):4749. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14234749

Chicago/Turabian StyleXu, Zhixiang, Zhanze Wang, Yunkai Deng, Yuanhao Li, Di Yao, and Feifeng Liu. 2025. "Assessment of GNSS-Based InBSAR Deformation Monitoring Using GB-SAR and D-GNSS Measurements" Electronics 14, no. 23: 4749. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14234749

APA StyleXu, Z., Wang, Z., Deng, Y., Li, Y., Yao, D., & Liu, F. (2025). Assessment of GNSS-Based InBSAR Deformation Monitoring Using GB-SAR and D-GNSS Measurements. Electronics, 14(23), 4749. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14234749