1. Introduction

Malicious Traffic Detection (MTD) is a critical technology for security defense in the Internet of Things (IoT), identifying potential malicious activities by monitoring abnormal behavior in network traffic in real-time. In response to the unique characteristics of heterogeneous devices, limited resources, and diverse communication protocols in the IoT, malicious traffic detection requires dynamic traffic analysis and lightweight detection algorithms, striking a balance between accuracy, real-time performance, and low computational overhead. Traditional traffic detection methods face critical challenges, including the variability and concealment of malicious traffic in IoT environments.

Machine learning methods can automatically learn feature representations, reducing reliance on manual feature engineering, and are suitable for large-scale traffic data analysis and complex pattern extraction. Le et al. [

1] proposed an XGBoost-based IoT intrusion detection method to mitigate multiclass sample imbalance in the Industrial Internet of Things (IIoT), enhancing attack detection performance in such scenarios. Thakkar et al. [

2] proposed a feature selection technique based on statistical importance fusion, which integrates standard deviation, mean, and median statistics to select relevant features and reduce redundant features. Thakkar et al. [

3] integrated Autoencoder (AE) and Principal Component Analysis (PCA) techniques for feature dimensionality reduction, using AE to capture nonlinear relationships and PCA to capture linear relationships. Traditional machine learning methods have limitations in extracting deep features from sequence data, resulting in insufficient generalization performance.

In contrast, detection systems based on deep learning [

4] demonstrate better accuracy and adaptability in detecting malicious traffic in the Internet of Things through hierarchical feature learning. Djenouri et al. [

5] proposed the D2E-ADN framework, which combines data decomposition, deep learning, and evolutionary computation. The authors employ five clustering algorithms to decompose the data, a new RNN model, and two evolutionary algorithms to optimize the hyperparameters. The framework outperforms the baseline algorithm in terms of runtime and accuracy. Yang et al. [

6] proposed a Data Purification Algorithm (DPA) to reduce data redundancy, enhanced the CNN structure based on separable convolution, and designed a lightweight detection algorithm, LSCNN. Wang et al. [

7] proposed an automated lightweight spatiotemporal decoupling Transformer framework called AutoLDT, which improves model performance while reducing model complexity. Deep learning-based methods can better extract deep features. However, most of these methods require a large amount of data for training, which poses challenges for practical network traffic scenarios. In practical network scenarios, a large amount of data is normal, and destructive data only accounts for a small portion, but it can bring incalculable losses. In IoT traffic detection tasks, there is still room for improvement in detecting a small number of samples.

Few-shot learning has made significant progress in fields such as image classification [

8] and temporal classification [

9], but its research in malicious traffic detection is still in the exploratory stage. Few-shot learning is significant in detecting network traffic with scarce abnormal data. In the early exploration of using Few-shot learning for malicious traffic detection, researchers mainly focused on introducing the basic concepts of Few-shot learning into this field. Olasehinde et al. [

10] were the first to apply meta-learning to intrusion detection, proposing a novel IDS based on three meta-learning algorithms. Subsequently, Lu et al. [

11] developed an IoT intrusion detection model by combining Model-Agnostic Meta-Learning (MAML) and Convolutional Neural Networks (CNN). They also constructed the FSIDS-IoT dataset (integrating five public datasets with multiple attack scenarios) to support few-shot learning. Leveraging MAML, the model quickly adapts to new attacks and achieves high few-shot detection accuracy; however, it lacks sample diversity and practical deployment testing. To further improve the performance of Few-shot learning in malicious traffic detection, Wu et al. [

12] proposed MASiNet, a multistage attention Siamese network. This model utilizes a carefully designed attention mechanism to more effectively extract network traffic features, while introducing a contrastive loss function to enhance the model’s ability to compare sample pairs. Experiments on NSL_KDD and UNSW_NB15 show that it outperforms existing methods. Most existing methods have not fully considered the relationships between samples, resulting in the feature representations learned by the model being less robust and discriminative, which limits the performance of Few-shot classification.

Therefore, inspired by previous research, we propose GADF-SRGA, a novel IoT malicious traffic detection framework. This framework combines temporal imaging techniques, few-shot meta-learning methods, and inter-sample class similarity relationships. First, the Gramian Angular Difference Field (GADF) imaging method encodes IoT network traffic data into two-dimensional images, preserving the temporal dependencies and pattern features of the traffic sequences. Convolutional networks are then used to extract features and generate a pre-trained model. Then, we propose the GADF-SRGA model, which enhances meta learning by incorporating a display-guided attention mechanism to capture inter-sample relationships. To verify the effectiveness of the proposed method, we validated the publicly available real IoT intrusion detection datasets ToN_IoT and Malicious_TLS. The contributions of this paper are as follows:

We propose a detection framework based on GADF-SRGA, which solves the problem of insufficient malicious traffic recognition performance in public IoT traffic detection datasets Malicious_TLS and ToN_IoT.

We utilize GADF image encoding to transform network traffic data into 2D images, thereby enhancing the representation of temporal and semantic features.

We introduce few-shot learning methods to solve the problems of insufficient learnable samples and low recognition accuracy of newly emerging attack types in the Internet of Things environment.

We propose a sample relevance guidance attention module, which addresses the issue of insufficient feature discriminability in existing few-shot classification methods by considering inter-image association relationships. This module significantly improves the model’s intra-class compactness and inter-class separability in the feature space.

2. Fundamental Technologies

This section sorts out the key technologies used and introduces the core principles of three key technologies: attention mechanism, model-agnostic meta-learning, and prototype classification.

2.1. Attention Mechanism

The attention mechanism [

13] is a computational paradigm in deep learning that simulates how human attention is allocated. Its core is to improve the model’s ability to capture key information by dynamically adjusting its degree of attention to different input parts. The entire attention mechanism process can be divided into three parts: correlation measurement, weight normalization, and weighted feature output. In the correlation measurement stage, suppose the input features generate a query vector

, a key vector

, and a value vector

through linear transformation, where

L is the length of the feature sequence, and

must be satisfied. The correlation between

and

is quantified by the dot product operation, and the formula is as follows:

where

is a scaling factor, used to avoid numerical overflow caused by the dot product of high-dimensional vectors and ensure the stability of gradient backpropagation. In the weight normalization stage, the Softmax function is used to convert the correlation score

into a probability distribution with a sum of 1, and the attention weight matrix

is obtained to realize the probabilistic highlighting of key features:

where the larger the weight

, the higher the contribution of the

j-th feature to the

i-th query target. In the weighted feature output stage, through the weighted summation of the attention weight matrix

and the value vector

, key information is aggregated, and the attention-enhanced feature is output:

In summary, the core of the attention mechanism is to adaptively assign weights to input features, so that the model can specifically capture the differentiated features of samples.

2.2. Model-Agnostic Meta-Learning

Model-Agnostic Meta-Learning (MAML) [

14] is a general framework in meta-learning suitable for few-shot scenarios. Its core goal is to optimize a set of initialized model parameters with strong generalization ability, enabling the model to quickly adapt to new tasks with only a few gradient updates. MAML is mainly divided into the meta-training phase and the meta-testing phase. The meta-training phase extracts general initialized parameters from many known malicious traffic tasks through task sampling and continuous iteration of inner and outer loop optimization to quickly adapt to new tasks in the meta-testing phase.

In the meta-training phase, first, N-way K-shot tasks are generated according to the task distribution

. Each task

consists of a support set

and a query set

, where

N is the number of categories and

K is the number of samples per category. In the meta-training phase,

N known categories are selected to maintain the consistency of task distribution. Each category extracts

K labeled samples to form

, and then extracts

samples to form

, where the sample categories are the same, but there are no overlapping samples between the support set and the query set. Then, for each generated task

, the inner loop starts with the initial meta-parameter

, calculates the loss

on the support set

, and updates the parameters in the direction opposite to the loss gradient, thereby performing task-level rapid fine-tuning. The update formula for the meta-parameter

is

where

is the inner loop learning rate.

After completing the inner loop fine-tuning of each task

, outer loop parameter optimization is performed. The initial meta-parameter

is updated by aggregating the loss of the query set

, and the meta-loss is

Subsequently, the initial parameter

is updated along the gradient direction of the meta-loss as follows:

where

is the outer loop learning rate.

In the meta-testing phase, the model’s ability to quickly adapt to new samples is verified through three links: constructing new tasks, parameter fine-tuning, and performance evaluation. First, select an N-way K-shot task

containing new-type samples from the test set

. Among them, the support set

is

K labeled samples of this new-type malicious traffic category, and the query set

is unlabeled samples of the same type, to simulate the detection scenario when encountering new-type malicious traffic. For

, using the optimal initial parameter

obtained from meta-training, gradient fine-tuning is performed through the inner loop to generate a parameter

adapted to new-type malicious traffic. The fine-tuning formula is

In the meta-testing phase, the model does not require retraining, and adaptation can be completed with only a small number of gradient updates.

2.3. Prototypical Networks

Prototypical Networks [

15] is a core framework based on the metric learning paradigm, suitable for handling fast adaptation problems under limited data conditions. A prototype is a typical feature representative of each category, composed of the mean value of the feature vectors of samples of that category in the support set. Prototypical Networks realize the rapid recognition of new categories through category prototype representation learning and feature distance metric. Prototypical Networks transform the classification problem into a distance calculation problem through four steps: feature embedding, prototype construction, distance metric, and classification decision. In the feature embedding stage, the original data is mapped to a high-dimensional feature space through a differentiable model to achieve effective feature extraction.

In the feature embedding stage, the original data is mapped to a high-dimensional feature space through a differentiable model to achieve effective feature extraction. When , its feature vector is , where d is the embedding dimension.

In the prototype calculation stage, for the

k-th category in the N-way K-shot task

, where

its support set is

, and the corresponding feature vectors are

. The calculation formula for the prototype vector of this category is

. As shown in

Figure 1, the prototypes of each category are represented as blue squares.

In the distance metric stage, Prototypical Networks realizes classification by measuring the distance between the query sample and the prototypes of each category. The smaller the distance, the higher the feature similarity between the sample and the category. The Euclidean distance is used to measure the distance between the feature

of the query sample and each prototype

, as shown below:

In the classification decision stage, the distance is converted into a classification probability, and the Softmax function is used to normalize the negative distance. The probability that the query sample

belongs to the

k-th category is

where

is a distance scaling factor, used to adjust the weight of the distance’s influence on the probability. The model is trained with cross-entropy loss as the optimization objective, and the classification error of the query set is minimized as follows:

3. Proposed Approach

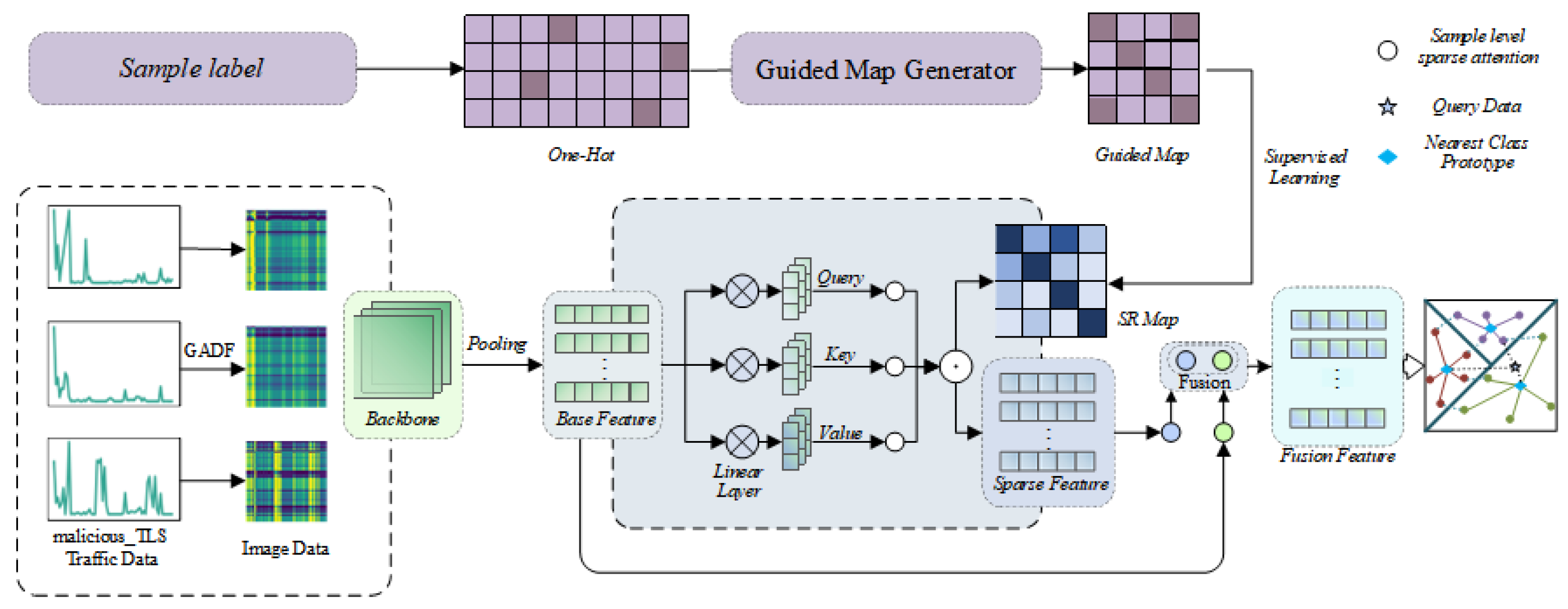

The overall framework of GADF-SRGA is shown in

Figure 2, which includes three parts: the traffic data visualization module, the Sample Relevance Guided Attention module, and the Nearest Prototype Classifier (NPC) module. The traffic data visualization module effectively extracts global spatial features and correlation information between features by converting traffic data into image data, thereby enhancing the spatial representation ability in network malicious traffic detection. It also uses a ResNet-based backbone to obtain pre-trained models. Then, in the Few-shot learning framework based on meta-learning, a sample association-guided attention mechanism is introduced, and the support set labels are used to explicitly guide the model to enhance the extraction of same-class relationships and expand the distance between different classes, thereby improving inter-class discrimination. Finally, based on the variable nature of task-learning categories, a nearest neighbor prototype classifier is used to classify the query set samples.

3.1. GADF Encoder

Raw traffic data exists only in a one-dimensional form composed of discrete time points, which makes it difficult to reflect temporal correlation characteristics—such as those of burst traffic. This limitation imposes constraints on traditional time-series analysis methods when capturing complex features. Specifically, traditional traffic processing methods face two key challenges: on one hand, they struggle to model the spatiotemporal correlation of multi-dimensional traffic features and fail to effectively capture dynamic collaborative patterns between different traffic dimensions; on the other hand, their ability to represent features of bursty and non-linear malicious traffic patterns is relatively limited, which often results in the loss of detailed information about key patterns during the feature extraction process. Furthermore, in few-shot scenarios, one-dimensional time-series data has an inherent attribute of sparse features, which cannot adequately support the model in quickly learning generalizable feature representations. This inadequacy further impacts the detection performance for new and unknown malicious traffic. To address this issue, we adopt the Gramian Angular Difference Field (GADF) [

16] to perform spatiotemporal feature reconstruction and modal conversion on network traffic data, thereby facilitating the extraction of fine-grained features.

The GADF is an image encoding technology that maps one-dimensional time-series data to two-dimensional images via polar coordinate transformation and Gram matrix construction, while completely preserving the temporal dependence and spatial correlation of the data. Compared with GASF and MTF, GADF more effectively captures the dynamic patterns of time series and converts them into image-based visual representations, facilitating subsequent feature extraction and classification. The implementation process of this technology is as follows: first, the one-dimensional time-series data is normalized to the interval [−1, 1]; after normalization, the value of each time-series point corresponds to two elements of polar coordinates, namely the angle and the radius. Subsequently, a two-dimensional image is generated through the matrix operation of the GADF. During this process, two key conversions take place: first, the order of the time-series data is converted into the spatial positional relationship of the image; second, the magnitude and variation trend of the data values are converted into the texture and shape features of the image. Ultimately, the dynamic patterns of the time series are fully encoded into the visual structure of the image. For a detailed implementation of the GADF-based encoding workflow, refer to Algorithm 1.

| Algorithm 1 GADF encoding for converting traffic data to images |

| Input: Traffic data , where N denotes the batch size, the k-th time-series data , the normalized scaling limit , sliding window size used to truncate the length of the time-series data. |

| Output: The set of GADF image matrices corresponding to the traffic data sequence is constructed as follows, where each uniquely corresponds to the timeseries data in a one-to-one manner. |

| 1. For each , : // Initialize the GADF Matrix of the k-th sample |

| // Data standardization |

| 2. For to : |

| 3. // Normalize within a single traffic flow |

| 4. , where //Truncate individual elements |

| 5. End for |

| // Polar coordinate transformation |

| 6. For to : |

| 7. // Angle corresponding to |

| 8. // Radius |

| 9. End For |

| // Gram Matrix Calculation |

| 10. For to : |

| 11. For to : |

| 12. |

| 13. End for |

| 14. End for |

| 15. // Image Scaling for |

| 16. Return |

Based on Algorithm 1, the traffic image dataset G can be obtained. The image data set is partitioned into mini-batches with a batch size of M, resulting in input images for each batch. Subsequently, the d-dimensional feature vectors are extracted from each batch of images using a backbone feature extractor. Finally, the feature vectors from each batch are concatenated along the sample dimension, yielding the basic feature .

The image encoding technology of the GADF mainly lies in three aspects: first, it converts the temporal dependence and numerical relationships of the one-dimensional time series into the spatial structure of two-Zdimensional images, facilitating the capture of multiscale local and global patterns; second, two-dimensional images can directly reuse mature image processing technologies, enabling efficient extraction of high-level visual features; third, the image-based dense feature representation can provide richer pattern information for meta-learning frameworks in few shot scenarios, thereby accelerating the model’s adaptation process to new types of malicious traffic.

3.2. Class-Sparse Attention Module

Malicious traffic classification frequently confronts novel traffic family attacks, such as zero-day vulnerabilities and variant ransomware samples, where the labeled samples of such novel malicious traffic are incredibly scarce, rendering it a typical few-shot classification scenario. Traditional methods rely solely on implicit feature similarity, which is prone to missing detections due to the one-sidedness of single-sample features; meanwhile, the full-attention mechanism tends to introduce noise. To address these issues, this paper proposes a class-sparse attention mechanism, which filters out noise via top-K sparsification and employs a guided map for explicit supervision to align with true categories. It aggregates the standard features of samples within the same class to compress intra-class differences and enlarge inter-class distances. Ultimately, it re-weights via the inter-sample class similarity graph to generate the class-sparse attention feature with explicit category association information. The detailed specifics are presented as follows.

The base feature undergoes three linear transformations to obtain query, key, and value vectors . Only the top K high-similarity associations are retained to construct the inter-class similarity graph of samples. The raw inter-class similarity score of samples is given by , where h is the scaling factor in the attention mechanism. The top-K sparsification strategy is defined as follows: for each class i, the top K associations with the highest similarity scores to other classes are retained, and the rest are set to 0, yielding the sparsified inter-class similarity score .

Finally, the sigmoid function is used for activation to generate the final inter-class similarity graph of samples as follows:

Unlike traditional few-shot learning methods that only indirectly optimize features via classification loss and tend to learn spurious similarities due to the lack of explicit constraints on class associations, this paper adopts a guided map (GM) to supervise SR explicitly. It constrains SR to align with true class relationships through a loss function. For a batch of input samples containing

N samples and

L classes, its one-hot encoding matrix is denoted as

. The guided map GM is obtained by multiplying the one-hot encoding matrix:

,

. Its elements are defined as follows:

GM provides label-level information to supervise the inter-class similarity graph SR of samples. GM enables the network to capture the true relationships between samples. Then, the value vector V is re-weighted by the inter-class similarity graph SR to obtain the class-sparse attention feature

for each sample:

where × denotes matrix multiplication and the softmax function ensures that the weighted aggregated features are consistent in scale with the original features. This class-sparse attention mechanism can thus obtain the task-relevant similarity graph SR of similar samples and the class-sparse attention feature

for malicious traffic classification.

Compared with the attention mechanism in Transformers [

13], the SRGA module exhibits differences in attention modeling granularity. Standard self-attention calculates attention weights at the token level, focusing on temporal dependencies between individual tokens in the input sequence. In contrast, the SRGA module models attention directly at the sample level, prioritizing correlations among entire malicious traffic samples rather than local token features. This makes SRGA more suitable for few-shot traffic detection tasks that require mining global sample relationships. Cross-attention relies on bidirectional mapping between the query set and the key-value set, yet lacks explicit category supervision and is susceptible to noise interference from heterogeneous traffic features. The SRGA module introduces a class-label-guided supervision graph that imposes sparse constraints on attention weights, retaining only the top-K high-similarity sample associations to suppress invalid cross-class attention calculations. This approach effectively reduces computational redundancy while enhancing intra-class compactness. Standard self-attention employs a unified scaled dot-product computation for all attention weights, leading to non-targeted weight allocation. In contrast, the SRGA module employs a dynamic weight allocation mechanism based on sample class similarity, strengthening association weights within the same malicious traffic family while weakening those of heterogeneous samples. This design enhances the model’s ability to distinguish between similar attack types in few-shot scenarios.

For each corresponding element in the inter-class similarity graph

and the guided map

, the relationship loss

is computed using the following formula:

where

is denotes the inter-class similarity score between sample

i and sample

j, and

represents the true class association label for the two samples. By constructing this relationship loss

, the learning process of the inter-class similarity graph

is explicitly guided to align its elements with those of

, thereby achieving more compact intra-class clustering of malicious traffic samples in the feature space from a global perspective and further enhancing the model’s generalization ability for few-shot novel malicious traffic.

3.3. Fusion Features

The base features extracted by the backbone network contain fine-grained information about samples, but they tend to lack class association, resulting in insufficient discriminability in few-shot scenarios. By contrast, the class-sparse attention features are generated under the supervision of the guided map; they can capture the correlation information of samples within the same class, yet may lose the fine-grained details of individual samples. To dynamically and adaptively fuse the base features extracted by the backbone network with the class-sparse attention features based on class information, this paper proposes an adaptive feature fusion strategy.

Given that base features and class-sparse attention features exhibit distinct focuses, each feature is incorporated with learnable feature weighting parameters. Accordingly, we define a weight parameter

and a bias parameter

for the base features and class-sparse attention features of input samples. For each feature, the linear transformation function

parameterized by a and b is expressed as follows:

where

represents the mean operation,

describes the variance operation, and

is a constant infinitely close to 0. The learnable parameter weights of the original and sparse features are independent. By linearly weighting the original features and the aggregated features, and then cascading the dimensions, the fusion feature

of the original features and sparse features is obtained, as shown below:

where ⊕ represents the connection operation.

3.4. Nearest Neighbor Prototype Classifier

The standard Few-Shot Classification (FSC) problem provides a training set and a test set . The FSC model is trained on a randomly sampled sequence of tasks from , and then evaluated on a randomly sampled sequence of tasks from . Each task consists of two disjoint sets: the support set and the query set , arranged according to the N-way K-shot setting, defined as where samples are organized. The query set is denoted as and shares a common label space with the support set. During the training phase, the FSC model learns from the support set and then extracts from to evaluate on the query set. This training strategy enables the model to effectively handle the behavior of processing a few samples, thereby enhancing the model’s robustness.

Recently, based on meta-learning approaches, the model has shown superior performance in various tasks. The original network framework calculates the average probability for each class

K as follows:

, where

represents samples of class

K, and

denotes the feature extraction. Subsequently, the classification probabilities for each sample class are computed using the Softmax function to obtain the class probabilities.

where

is the class prototype. The distance between the sample feature

and the class prototype

indicates the proximity of the sample to the respective class. The function

is used for normalizing the Euclidean distance

, which represents the distance between samples. The higher the distance, the larger the influence on the classification.

N represents the number of classes. The learning process minimizes the loss function

. In this paper, we employ the cross-entropy loss to minimize the prediction error of the query samples for each task, as follows:

where

is the number of samples in the query set of a task, and

N is the total number of classes in the dataset.

is the ground truth label, which is 1 if the query sample

q truly belongs to class

k, and 0 otherwise.

is the sample classification probability obtained from Equation (

17). Finally, based on the sample-based loss, the total loss

for classification learning and cross-entropy defined in (3) is given by:

where

and

are hyperparameters that control the impact of each loss term on the overall loss.

4. Experimental Design and Results Analysis

This section describes the dataset, relevant experimental details, and experimental setup.

4.1. Datasets Description

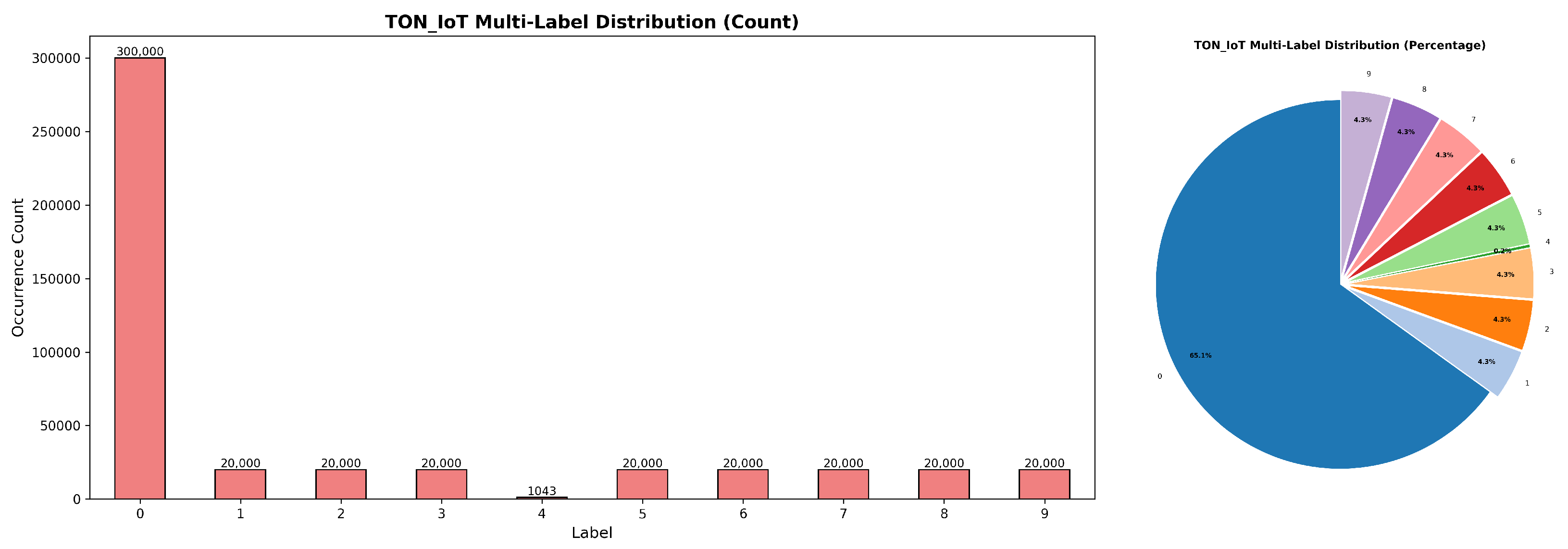

To verify the effectiveness and detection performance of GADF-SRGA in real-world IoT environments, we conduct IoT intrusion detection using the private dataset Malicious_TLS and the public dataset ToN-IoT. The Malicious_TLS dataset is a malicious traffic dataset captured from real edge network devices, where all traffic is encrypted with TLS technology. This dataset contains 22 different types of traffic. The ToN-IoT dataset contains traffic captured from real IoT environments, including 10 different types of traffic. The training set and test set are partitioned in a ratio of 7:3. As shown in

Figure 3, it illustrates the class distribution and categorization of the ToN-IoT dataset, where class 0 represents benign samples, and the remaining classes correspond to different malicious traffic families.

In the ToN-IoT dataset, benign samples account for approximately 68.1%. Among the malicious traffic families, except for Class 4 which represents 0.2%, each of the remaining classes accounts for about 4.3%, indicating a significant difference in the number of samples across malicious traffic families.

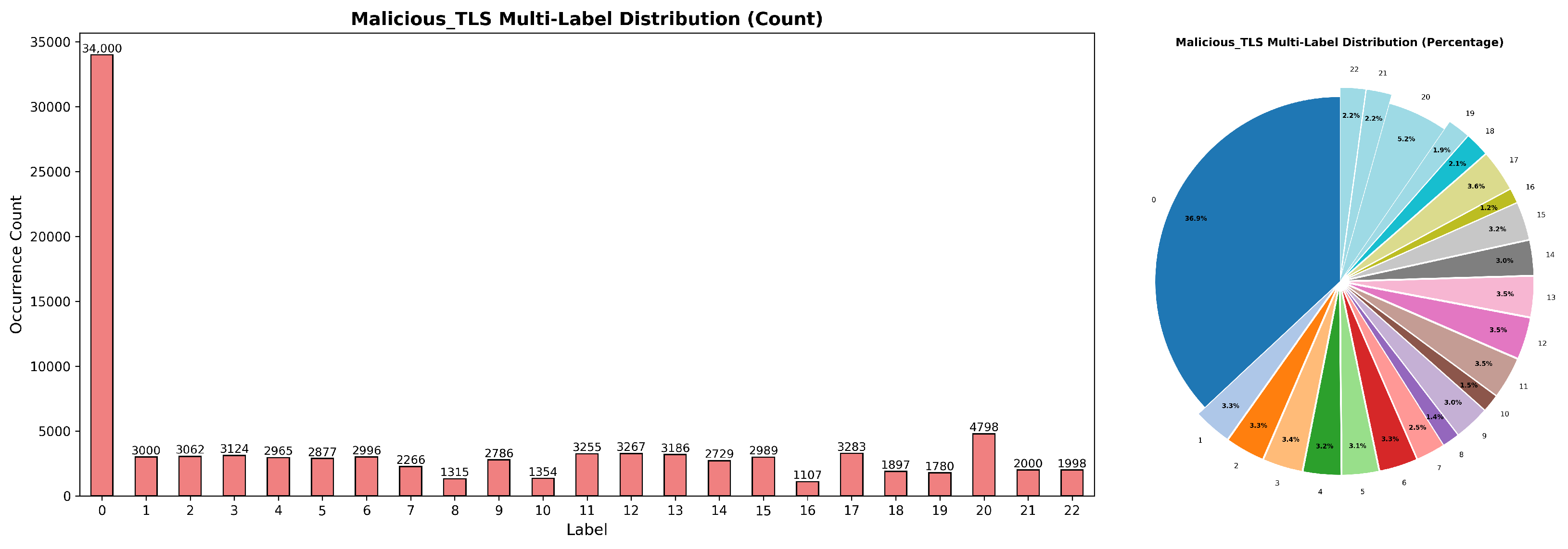

As shown in

Figure 4, it presents the class distribution of the Malicious_TLS dataset, where Class 0 denotes benign samples and the rest correspond to different malicious traffic families.

In the Malicious_TLS dataset, benign samples account for 34.9%. There are significant differences in the occurrence counts and proportions among different malicious traffic families; for instance, Class 20 occurs 4798 times, while Class 16 only appears 1107 times, indicating a significant class imbalance.

4.2. Experimental Settings

Experimental environment: All experiments were conducted on the same device, equipped with an NVIDIA A100 80GB GPU. The experimental setup is configured with Python 3.12, PyTorch 2.5, and CUDA 12.1 to ensure an efficient, reproducible experimental environment.

To verify the effectiveness of the proposed method, this experiment utilizes four commonly used evaluation metrics in malicious traffic detection and classification: accuracy (Acc), precision (Pr), recall (Rc), and F1-score (F1). The specific calculation methods are shown in Equations (20)–(23). This section may be divided by subheadings. It should provide a concise and precise description of the experimental results, their interpretation, and the conclusions that can be drawn.

Model parameter settings: The configuration of important hyperparameters of the model is shown in

Table 1.

As shown in

Table 1, in the hyperparameter configuration, the learning rate is set to 0.001, which balances the convergence rate and stability of parameter updates in the meta-learning framework; the number of epochs is set to 200 to ensure the model entirely fits the meta-training data; the number of meta-learning task-based training episodes (Num_episode) is set to 600, and multi-task sampling in each meta-training phase enhances the model’s generalization ability in few-shot scenarios; the multi-source guided classification loss weights

are set to 1.0 and 1.5 respectively, balancing the contributions of different classification losses; the image size

is 28, adopting lightweight encoding for malicious traffic features; both the embedding dimension

and the fusion dimension

are 64, ensuring the efficiency of feature embedding and feature interaction.

According to the characteristics of meta-learning, the dataset needs to be divided into two parts: the meta-training set and the meta-validation set, each part containing a support set and a query set. Taking the Malicious_TLS dataset as an example, the initial dataset has 23 categories, including 22 attack categories and 1 benign category. Firstly, the 23 categories of the dataset were shuffled, and 18 categories were randomly selected as the meta-training set, while 5 categories were chosen as the meta-validation set. Randomly select 15 samples from each category as the query set and N = {1, 5, 10} samples as the support set. The tasks required for meta-learning are randomly combined from these categories, with each task containing a small number of training and testing samples.

4.3. Comparative Experiments with Meta-Learning Approaches

To evaluate the traffic classification performance of the proposed method under few-shot conditions, we established three scenarios: 5-way 10-shot, 5-way 5-shot, and 5-way 1-shot. We employed four metrics, namely Accuracy (Acc), Precision (Pr), Recall (Rc), and F1-score (F1), for assessment and mitigated randomness through cross-task validation. Firstly, comparative experiments were conducted on the Malicious_TLS dataset, contrasting the proposed method with four classic meta-learning models in the few-shot domain, including MAML, Reptile, MatchingNet, and ProtoNet. The comparison results are summarized in

Table 2.

As shown in

Table 2, the metrics represented in

bold indicate the highest performance values, while the metrics represented in

underlined text denote the second-highest performance values. In the various few-shot scenarios of the Malicious_TLS dataset, the proposed method consistently demonstrates performance advantages. Specifically, it achieves an accuracy metric of 97.17% in the 5-way 1-shot scenario, which increases to 97.34% in the 5-way 5-shot scenario, and further improves to 97.72% in the 5-way 10-shot scenario. In the 5-way 1-shot scenario, the method demonstrates superior performance in terms of accuracy and precision, reaching 97.17% and 97.14%, respectively, while the second-best methods, MatchingNet and ProtoNet, attain an accuracy of 96.69%. In the 5-way 5-shot scenario, the proposed method achieves the highest performance across all four metrics, with values of 97.34%, 97.56%, 97.34%, and 97.45%; the second-best method, ProtoNet, scores 97.28%, 97.36%, 97.28%, and 97.31%. In the 5-way 10-shot scenario, the proposed method maintains its superiority with an accuracy of 97.72%, which is 0.21 percentage points higher than the second-best method, ProtoNet, at 97.51%. In summary, the proposed method consistently surpasses the baseline models in all evaluation metrics across the few-shot scenarios of Malicious_TLS traffic.

Next, for the ToN_IoT dataset, we conducted comparative experiments between the proposed method and four classic few-shot models: MAML, Reptile, MatchingNet, and ProtoNet. The comparison results are shown in the

Table 3.

As shown in

Table 3, the metrics represented in

bold indicate the highest performance values, while the metrics represented in

underlined text denote the second-highest performance values. In the various few-shot scenarios of the ToN_IoT dataset, specifically from 5-way 1-shot to 5-way 10-shot, the proposed method consistently demonstrates performance advantages. In the 5-way 1-shot scenario, the accuracy reaches 92.37%, while the accuracy for the 5-shot scenario is 96.56%, and it further increases to 97.81% in the 10-shot scenario. In the 5-way 1-shot scenario, the proposed method achieves the best performance, with accuracy and precision values of 92.37% and 92.84%, respectively. The following method, ProtoNet, has an accuracy of 84.59% and a precision of 86.09%. In the 5-way 5-shot scenario, the proposed method is optimal across all four evaluation metrics, achieving an accuracy of 96.56%, which is 3.84 percentage points higher than the next best method, MatchingNet, with an accuracy of 92.72%. In the 5-way 10-shot scenario, the proposed method maintains its superiority with an accuracy of 97.81%, surpassing the next best method, ProtoNet, by 4.45 percentage points, as ProtoNet’s accuracy is 93.36%.

The MAML method struggles to extract spatiotemporal patterns of malicious traffic because it lacks traffic-specific feature enhancement mechanisms. Meanwhile, Reptile is constrained by its simplistic gradient update strategy, which results in inadequate generalization and robustness when dealing with class imbalance. Additionally, MatchingNet employs a cosine similarity-based matching mechanism, making it challenging to differentiate between semantically similar variants of malicious traffic. ProtoNet’s approach to modeling class prototypes through mean calculations is susceptible to interference from outlier samples and dominant classes, resulting in significant bias in prototype representation under imbalanced conditions. In contrast, the GADF-SRGA proposed in this paper effectively preserves the spatiotemporal correlation features of malicious traffic. Its SRGA module explicitly models inter-sample class correlations, significantly improving classification robustness. Furthermore, it incorporates a meta-learning framework that enables rapid few-shot adaptation, maintaining high accuracy even in extreme 1-shot scenarios. In summary, the proposed method consistently outperforms all baseline comparison models across various evaluation metrics in few-shot scenarios for both Malicious_TLS and TON_IoT traffic datasets.

4.4. Comparison Experiment

To verify the performance of the proposed time series classification method under few-shot conditions, three scenarios were defined: 5-way 10-shot, 5-way 5-shot, and 5-way 1-shot. The evaluation metric uses classification accuracy and eliminates the influence of randomness through cross-task validation. The few-shot IoT malicious traffic detection model based on GADF-SRGA proposed in this paper can dynamically adjust the network and adapt to new tasks. In

Table 4, we review the results of other researchers in terms of the dataset used, the number of model categories used, classification settings, feature types, and the amount of data used during the training process.

GADF-SRGA achieves 97.34% accuracy under the 5-way 5-shot configuration and reaches 97.72% on the Malicious_TLS dataset under 5-way 10-shot settings. This unequivocally validates its dual capability: effective multi-category classification and rapid feature learning from minimal samples, delivering distinct advantages for detecting novel attacks prevalent in IoT environments. Notably, GADF-SRGA attains near 98% accuracy with merely 9183 samples (5-way 10-shot), while the Aggregation model requires approximately 30 million samples to achieve comparable performance.

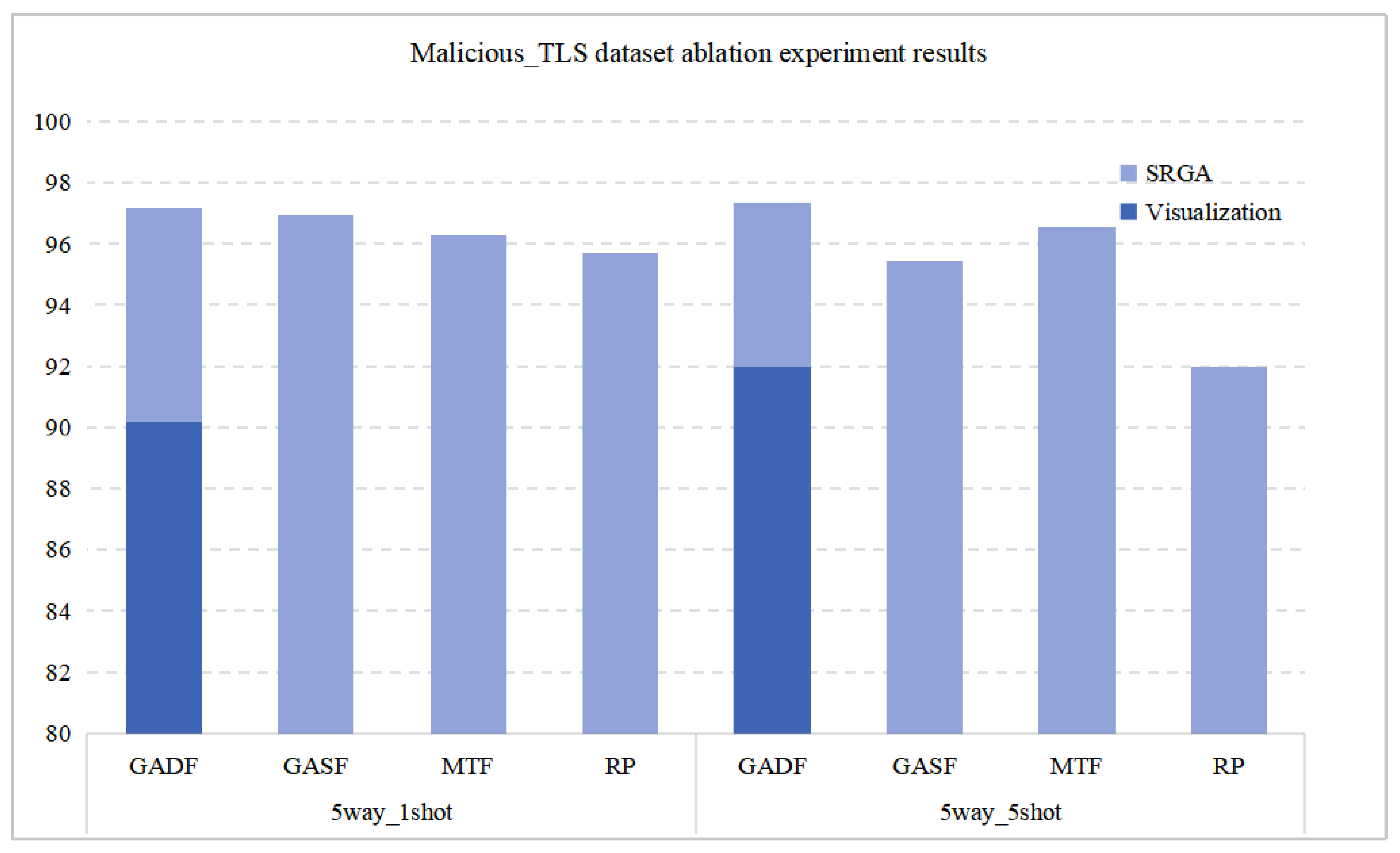

4.5. Ablation Experiments

To verify the effectiveness of the proposed image-based few-shot malicious traffic detection model, we conducted ablation experiments on the Malicious_TLS dataset to validate the effectiveness of each module: the traffic data visualization module (comparison of different visualization methods) and the Sample Relevance Guided Attention (SRGA) module. The results of the ablation experiment are shown in

Table 5.

As shown in

Table 5, bold font denotes the best result, and underlined font denotes the suboptimal result. When the GADF method is used to convert traffic data into images for few-shot experiments, the improvement in model performance is significant when combined with the SRGA module. In the 5-way 1-shot setting, the proposed method achieves an accuracy 7.02% higher than that of the model without the SRGA module. Experiment 1 demonstrates that the SRGA module can effectively improve the accuracy of few-shot classification. Comparative experiments were further conducted in Experiments 2–5 by combining the SRGA module with different traffic visualization methods. When the GADF method is adopted in this study, the accuracies in the 5-way 1-shot and 5-way 5-shot settings both achieve the highest values, which are 97.17% and 97.34% respectively. Specifically, in the 5-way 1-shot setting, the accuracy is 0.21%, 0.89%, and 1.47% higher than those of the GASF, MTF, and RP methods; in the 5-way 5-shot setting, the accuracy is 1.91%, 0.78%, and 5.36% higher than those of the GASF, MTF, and RP methods. Different traffic data visualization methods have different impacts on model performance. In the ablation experiment on the Malicious_TLS dataset, the accuracy of GADF-SRGA on task 5way_1shot and 5way_5shot was 97.17% and 97.34%, respectively, achieving the best performance among all ablation experiments. The visualization of the results is shown in

Figure 5.

Experimental results demonstrate that the combination of the GADF method adopted in this study and the SRGA module achieves the highest accuracy and exhibits the best performance.

5. Conclusions

This paper proposes a few-shot malicious traffic detection method based on a sample similarity-guided attention mechanism. This method integrates a sample relevance-guided attention module into the meta-learning framework to explore the application potential of few-shot learning in this task. Experiments verify that the method can address label scarcity in IoT network anomaly detection with a small amount of labeled data, and it exhibits excellent feature extraction performance on the Malicious_TLS and ToN-IoT datasets, with detection performance significantly outperforming existing methods.

Although GADF-SRGA achieves good performance in few-shot malicious traffic detection, it still has two limitations: first, for malicious traffic types not observed during training, the model can only identify them by relying on the general spatiotemporal features extracted by GADF image encoding and the sample relationship generalization ability of the SRGA module. In few-shot scenarios, it is unable to learn exclusive feature patterns for new attacks, which tends to weaken the discriminative ability due to feature distribution shift; second, the computational cost of the method and its deployment feasibility on resource-constrained IoT devices remain unclear, and the real-time deployment adaptability on edge IoT devices is yet to be verified.

To address the above limitations, future research will focus on the pruning and network design of lightweight multimodal models, aiming to improve the efficiency of model training and design, while solving the deployment challenges of it on resource-constrained devices.