Forward and Backpropagation-Based Artificial Neural Network Modeling Method for Power Conversion System

Abstract

1. Introduction

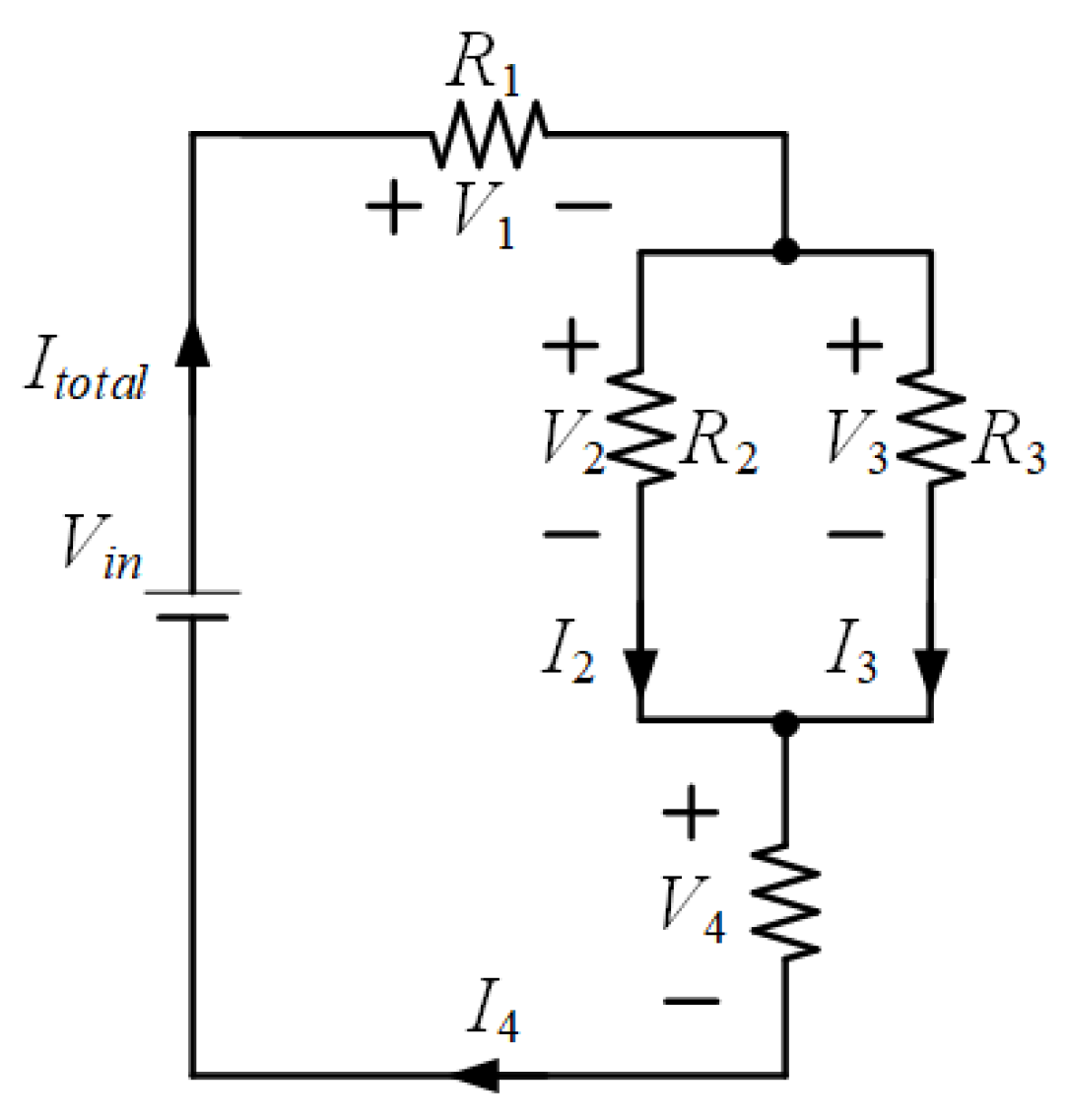

2. Power Conversion Systems Modeling

2.1. Circuit Configuration and Operating Characteristics

2.2. Necessity of Predictive Modeling

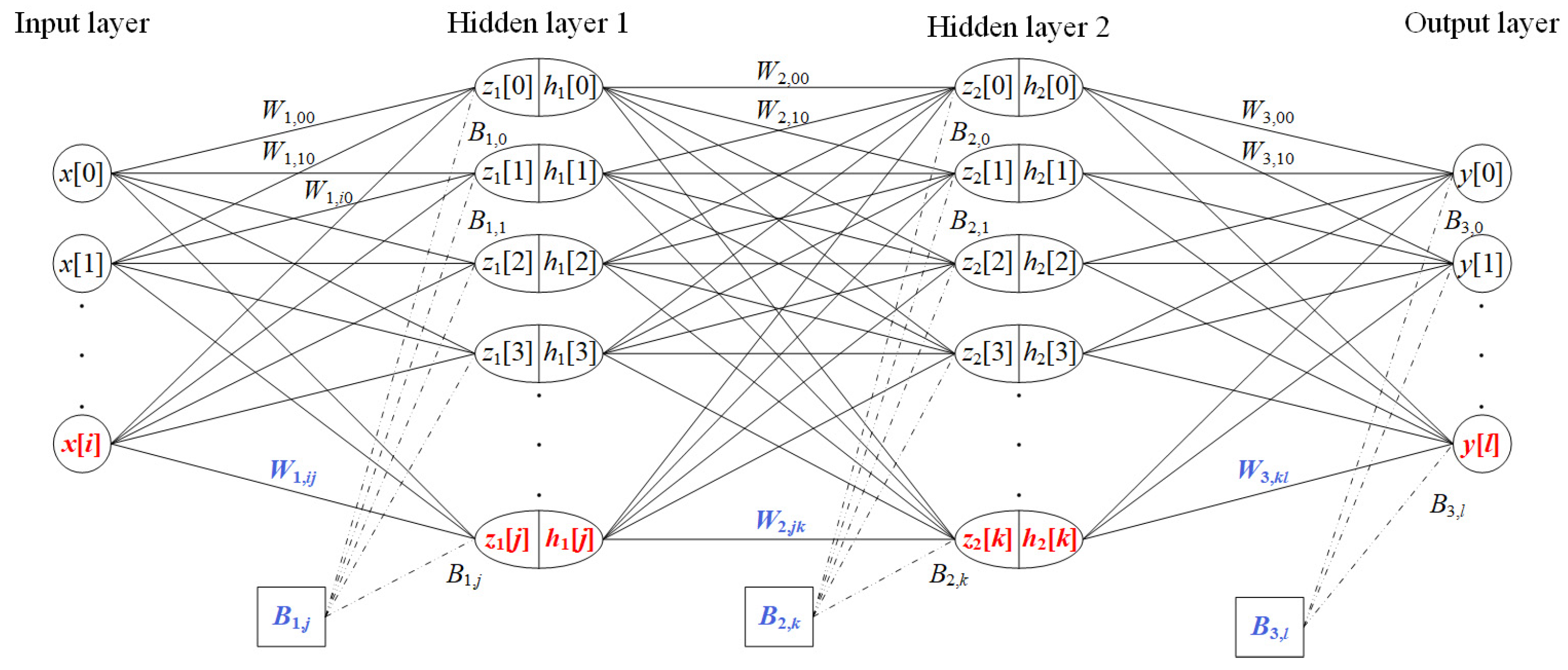

3. Artificial Neural Network Modeling Method

3.1. Structure of Proposed Artificial Neural Network

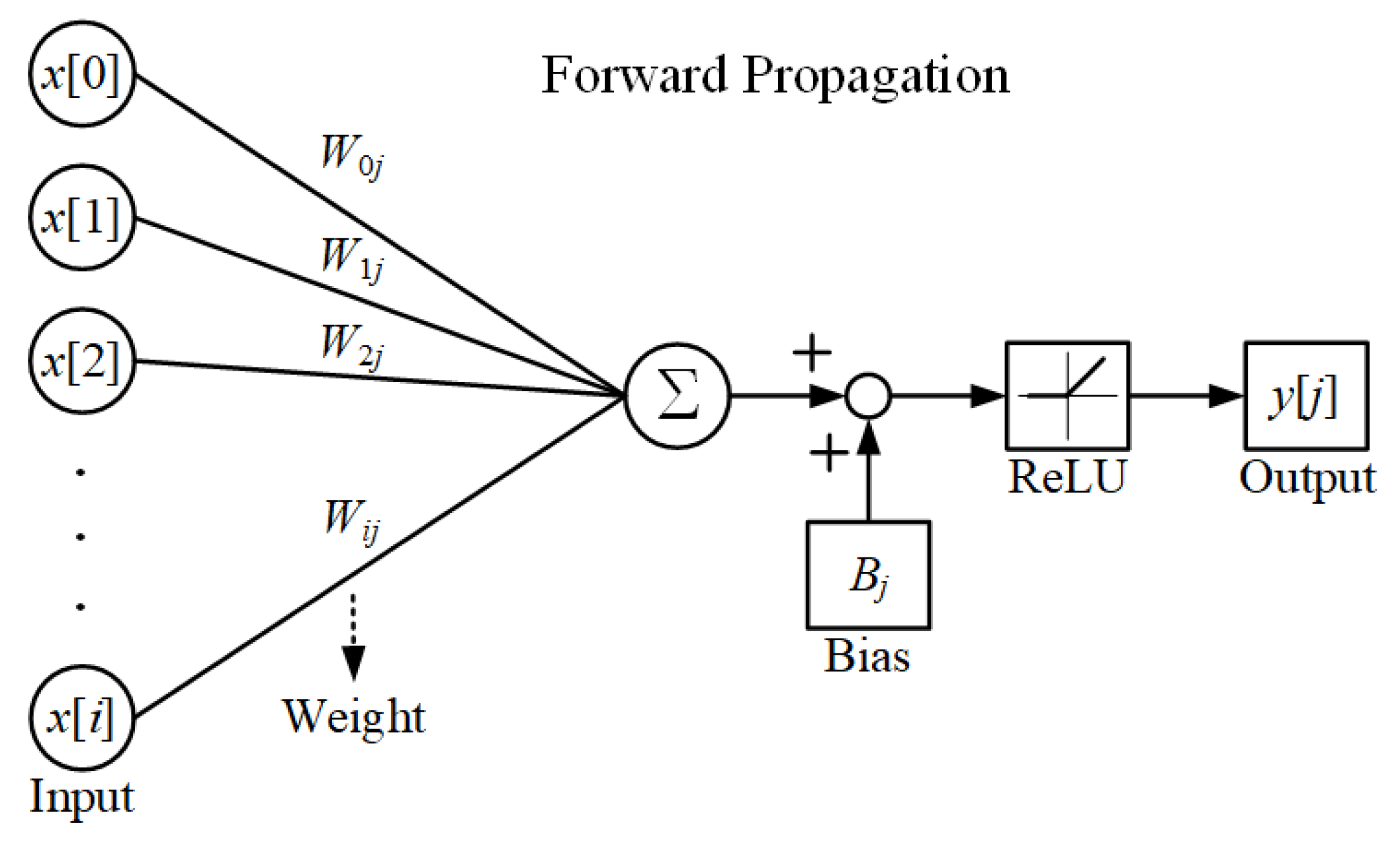

3.2. Forward Propagation Modeling

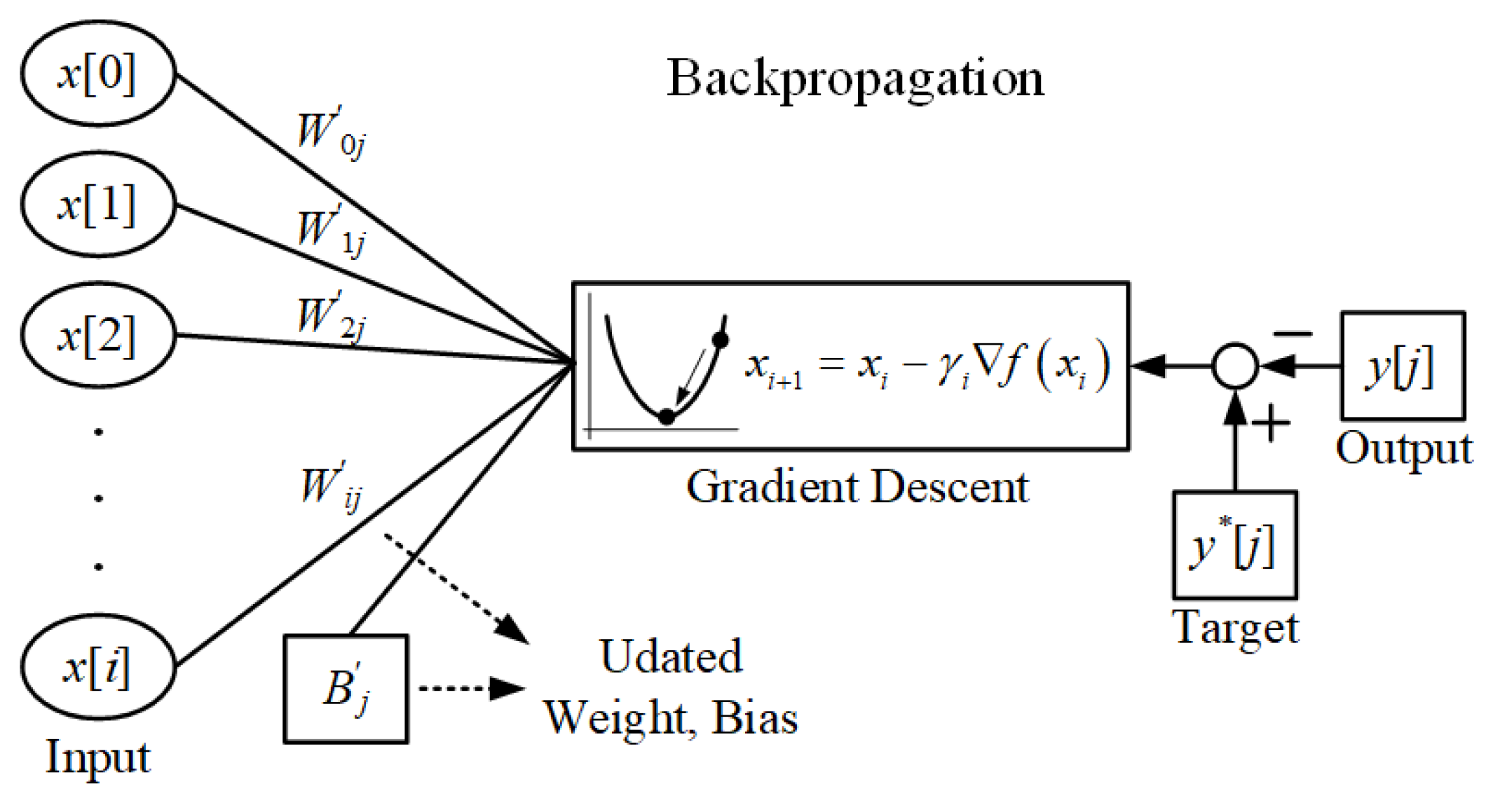

3.3. Backpropagation Modeling

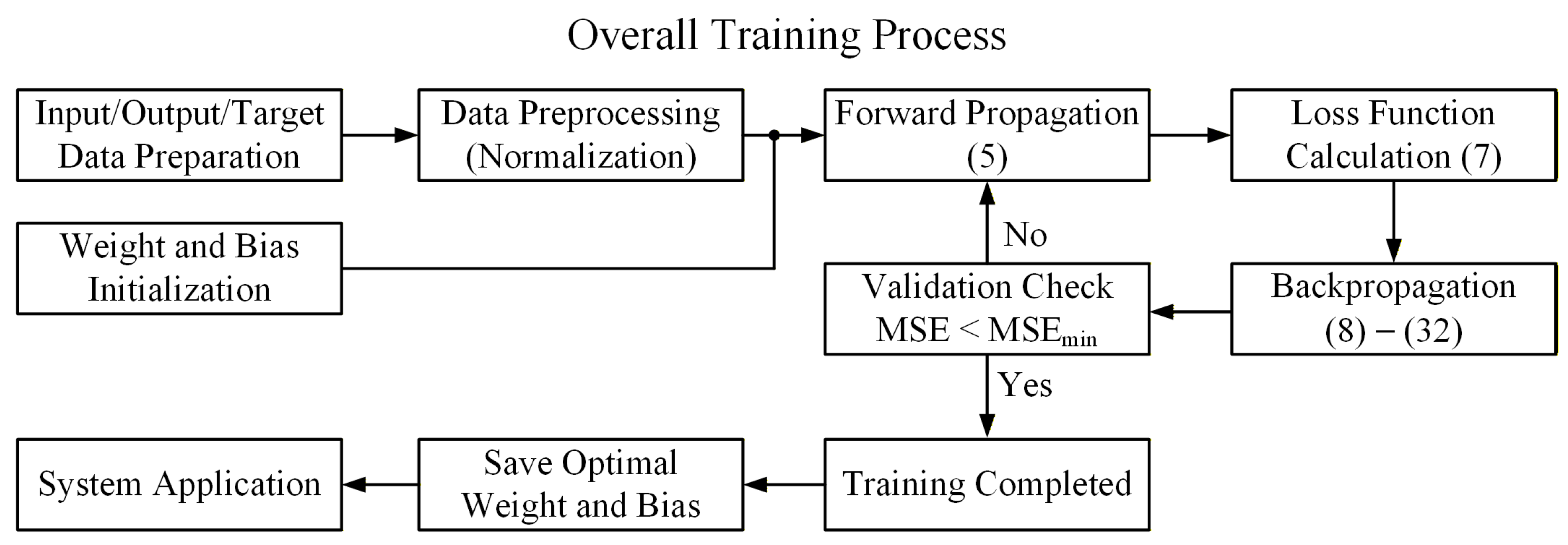

3.4. Overall Training Process

- Data preprocessing:

- 2.

- Weight and bias initialization:

- 3.

- Forward propagation:

- 4.

- Loss function calculation:

- 5.

- Backpropagation:

- 6.

- Iterative training and termination condition setting:

- 7.

- Training completion and application.

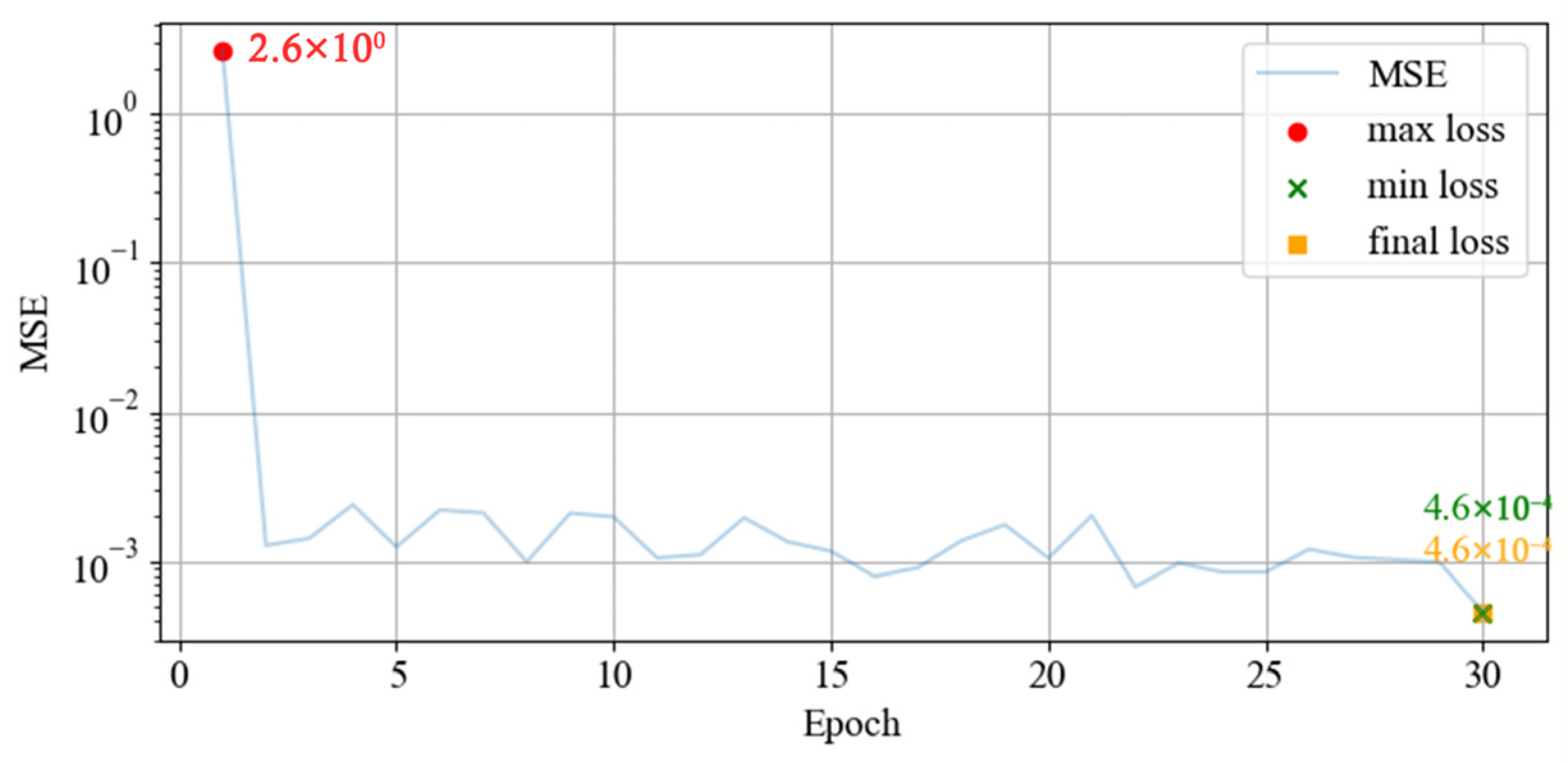

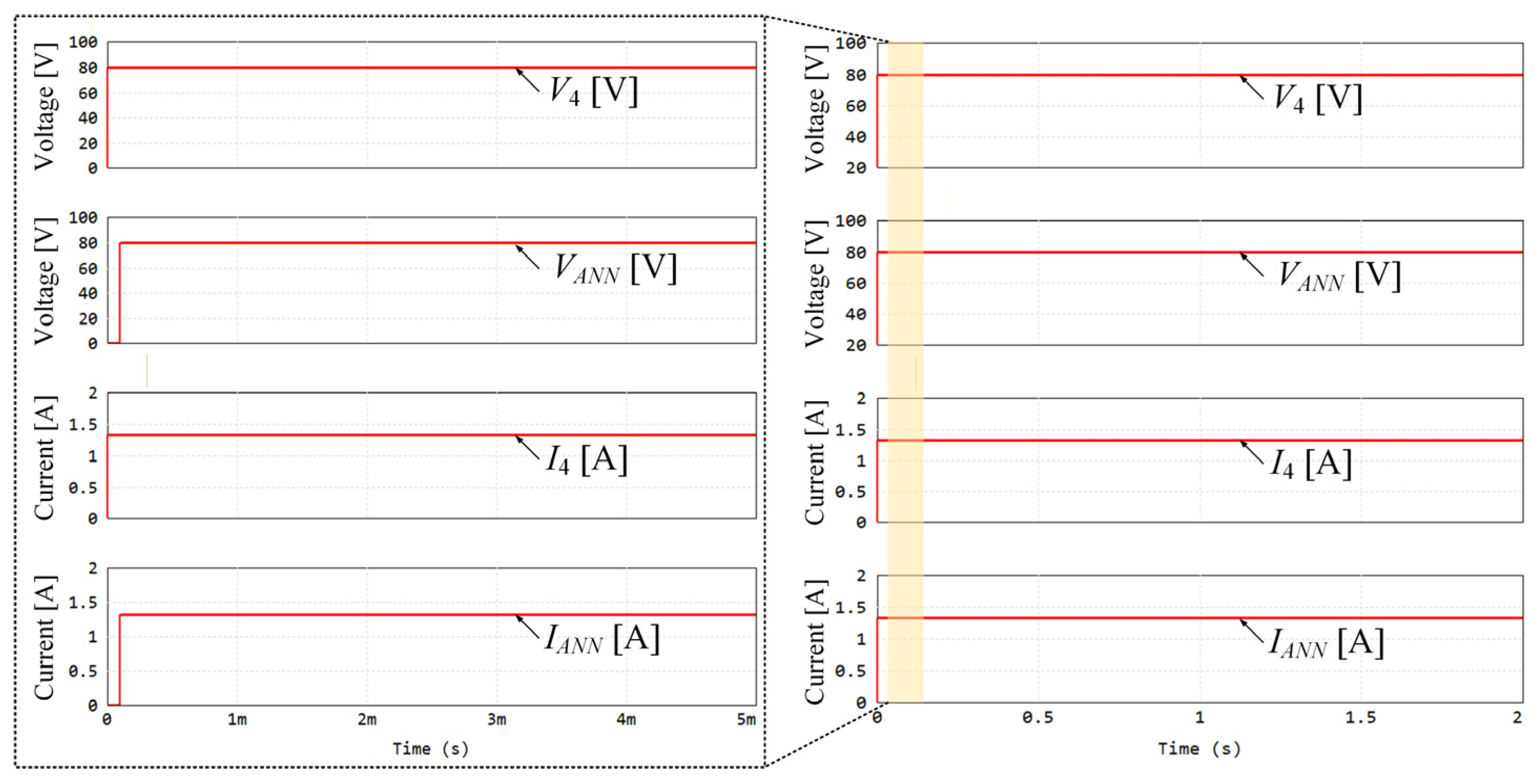

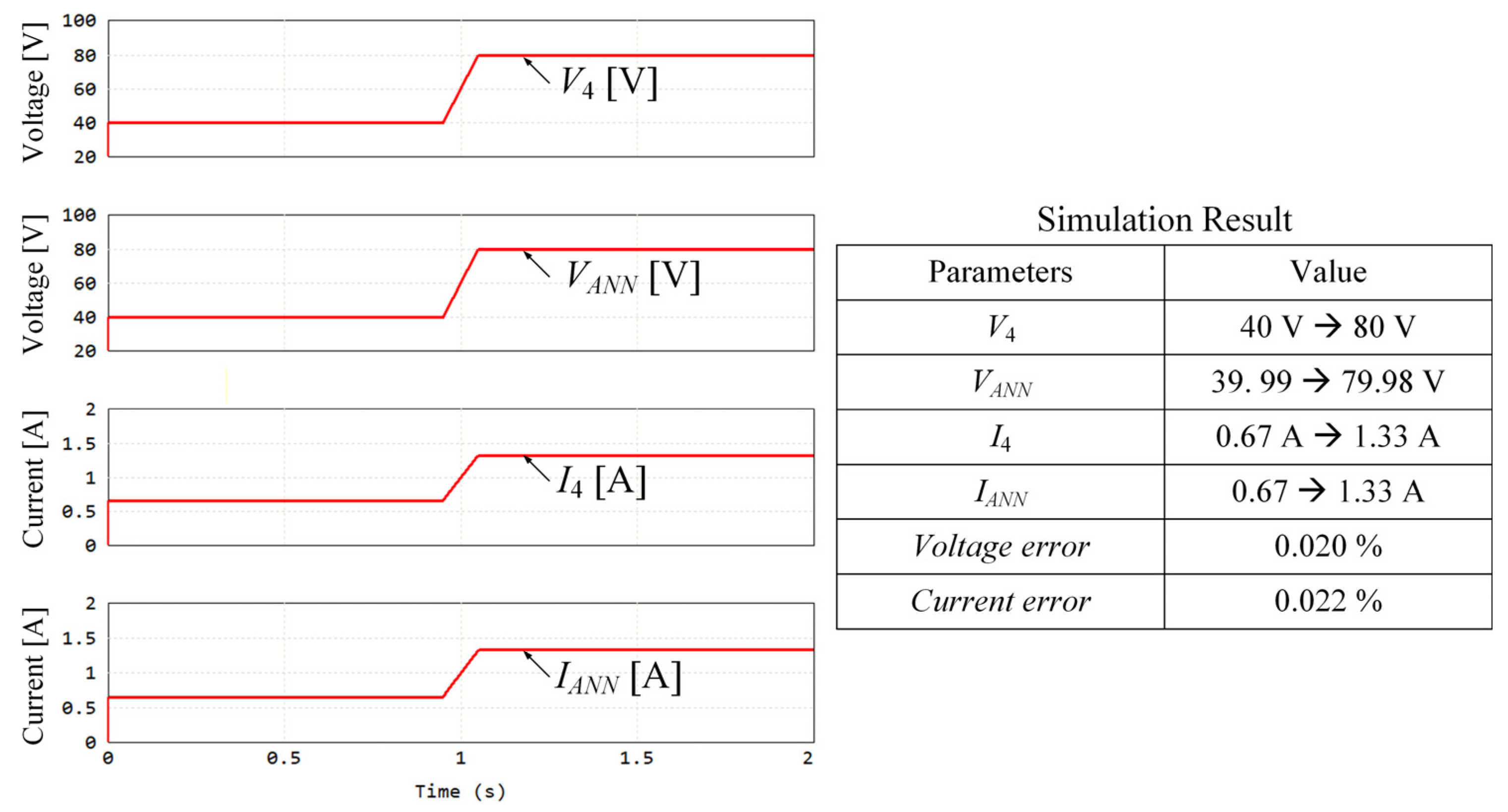

4. Simulation Results

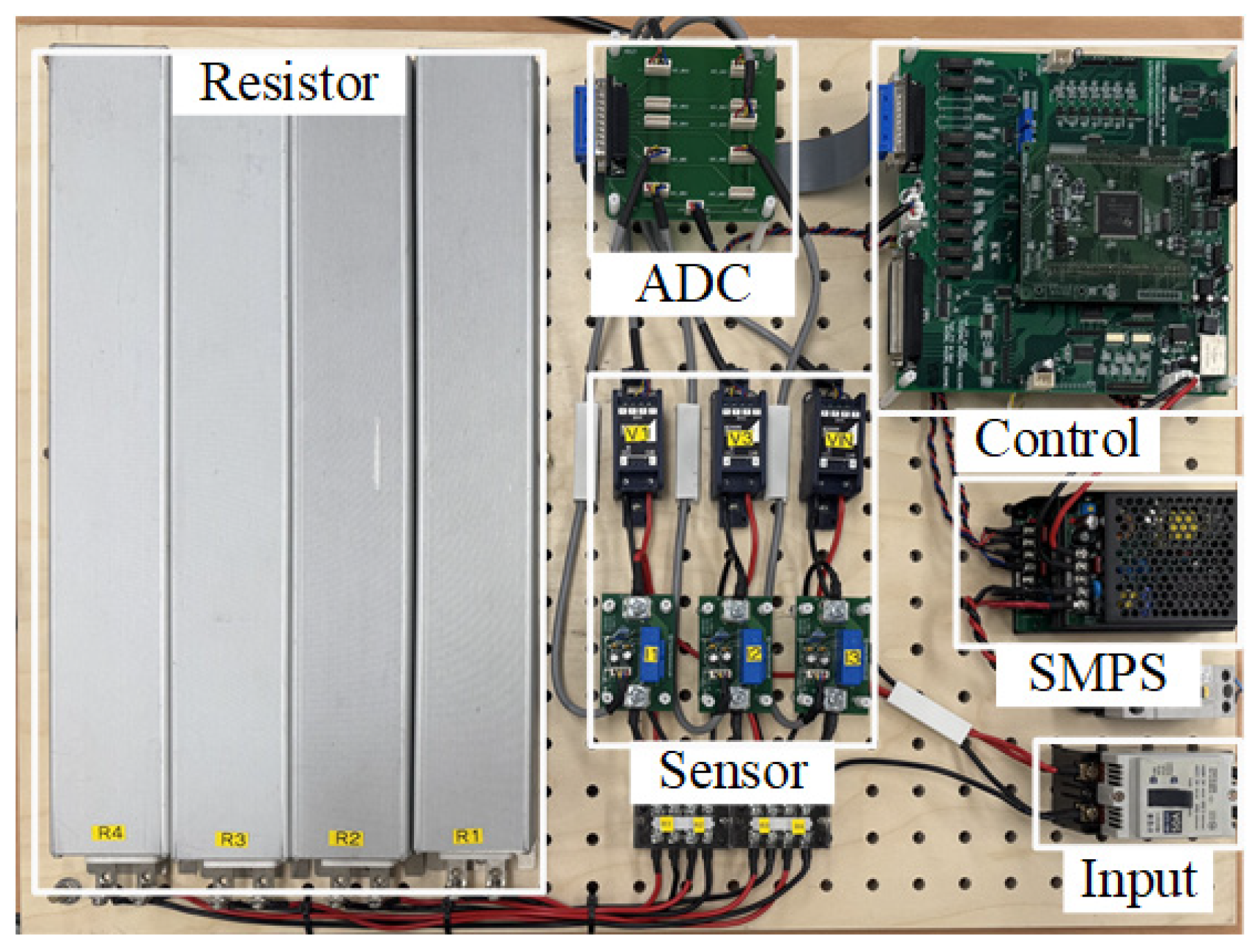

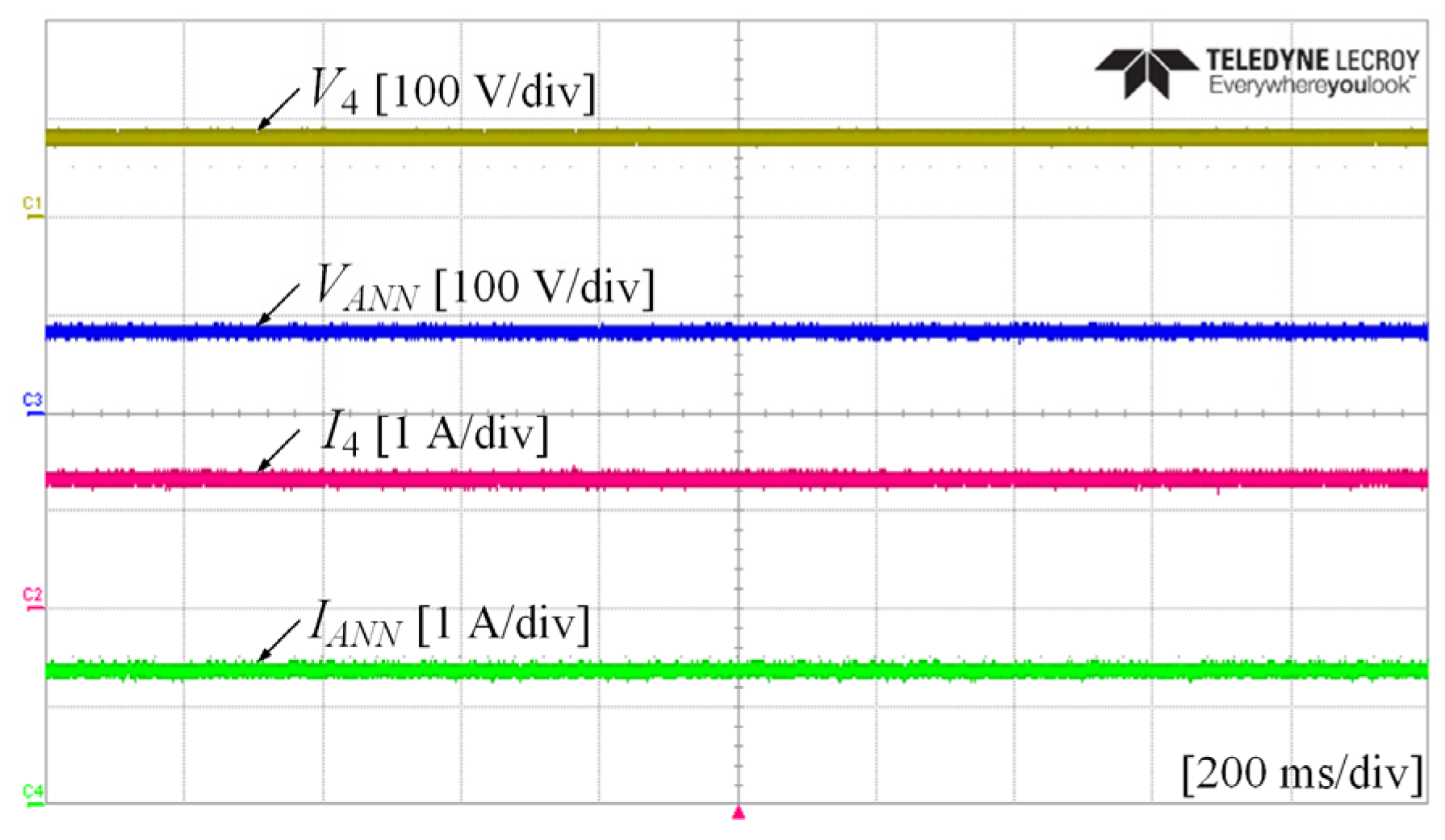

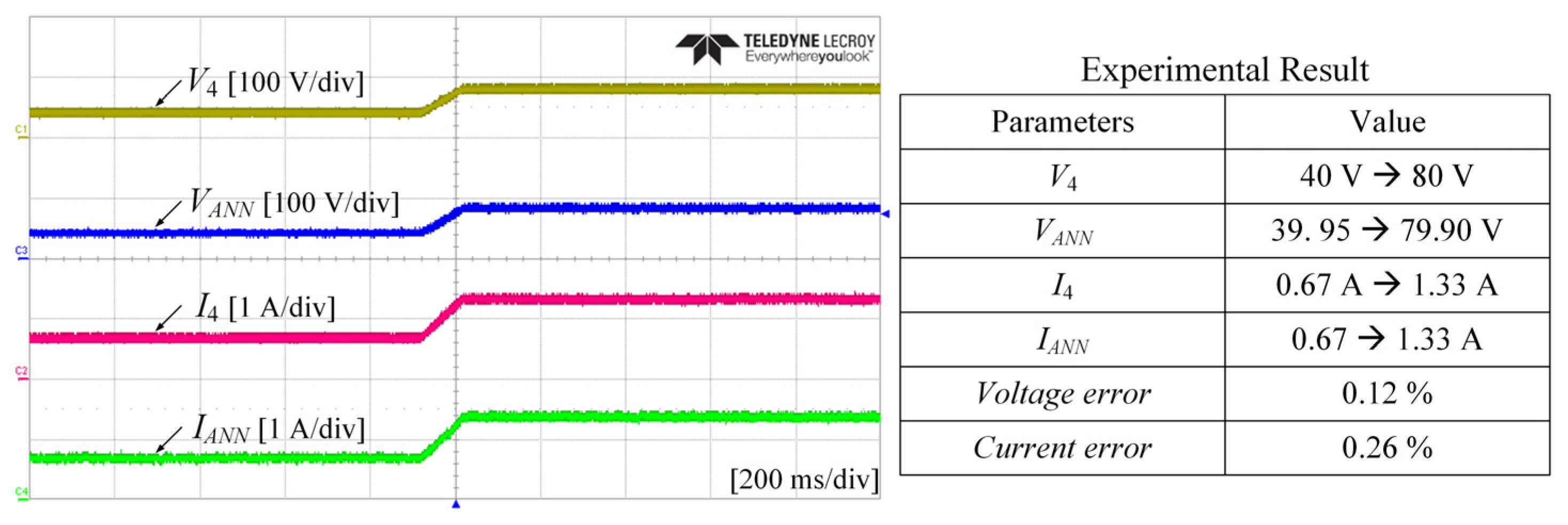

5. Experimental Results

6. Discussions

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bhardwaj, A.; Moon, J.; Nguyen, D.N.; Pamidi, S.V. A Novel Power Conversion System for SMES in Pulsed Power Applications. IEEE Trans. Appl. Supercond. 2025, 35, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaramasu, V.; Wu, B.; Sen, P.C.; Kouro, S.; Narimani, M. High-Power Wind Energy Conversion Systems: State-of-the-Art and Emerging Technologies. Proc. IEEE 2015, 103, 740–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, T.; Kim, T. Novel Energy Conversion System Based on a Multimode Single-Leg Power Converter. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2013, 28, 213–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Zhang, Z.; Ericsen, T.; Raju, R.; Burgos, R.; Boroyevich, D. Advances in Power Conversion and Drives for Shipboard Systems. Proc. IEEE 2015, 103, 2285–2311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Mok, K.T.; Tan, S.C.; Hui, S.Y. Nonlinear Dynamic Power Tracking of Low-Power Wind Energy Conversion System. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2015, 30, 5223–5236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Zhu, L.; Yang, F.; Mu, T.; Ge, H. Dual-DC-Port Asymmetrical Multilevel Inverters with Reduced Conversion Stages and Enhanced Conversion Efficiency. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2017, 64, 2081–2091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habib, S.; Khan, M.M.; Abbas, F.; Ali, A.; Faiz, M.T.; Ehsan, F.; Tang, H. Contemporary Trends in Power Electronics Converters for Charging Solutions of Electric Vehicles. CSEE J. Power Energy Syst. 2020, 6, 911–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.W.; Kim, H.; Song, M.; Kim, J.J. Energy-Efficient Power Management Interface with Adaptive HV Multimode Stimulation for Power-Sensor Integrated Patch-Type Systems. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Circuits Syst. 2023, 17, 1355–1370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, M.; Gong, Y.; Mao, R.; Liu, Z.; Tian, B.; Hu, Z.; Liu, M. An External Interference-Resistant Noncontact Voltage Sensor with Negative Feedback Design. IEEE Sens. J. 2024, 24, 17040–17044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nibir, S.J.; Biglarbegian, M.; Parkhideh, B. A Non-Invasive DC-10-MHz Wideband Current Sensor for Ultra-Fast Current Sensing in High-Frequency Power Electronic Converters. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2019, 34, 9095–9104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, O.; Dabas, S.; Sikder, A.; Smith, R.; Madiraju, P.; Yahyasoltani, N.; Ahamed, S.I. State-of-the-Art Versus Deep Learning: A Comparative Study of Motor Imagery Decoding Techniques. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 45605–45619. [Google Scholar]

- Kolman, E.; Margaliot, M. Are Artificial Neural Networks White Boxes? IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. 2005, 16, 844–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lang, W.; Hu, Y.; Gong, C.; Zhang, X.; Xu, H.; Deng, J. Artificial Intelligence-Based Technique for Fault Detection and Diagnosis of EV Motors: A Review. IEEE Trans. Transp. Electrif. 2022, 8, 384–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Dai, X.; Song, X.; Liu, G. ITSC Fault Diagnosis for Five Phase Permanent Magnet Motors by Attention Mechanisms and Multiscale Convolutional Residual Network. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2024, 71, 9737–9746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Wang, X.; Wei, H. Electromagnetic Performance Analysis, Prediction, and Multiobjective Optimization for U-Type IPMSM. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2024, 71, 10322–10334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.-K.; Yoo, D.-W.; Hur, J. Application and Verification of Voltage Angle-Based Fault Diagnosis Method in Six-Phase IPMSM. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 2024, 60, 426–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, T.; Kawakami, W.; Kuwabara, S.; Kobayashi, S.; Hirano, A. Intelligent Monitoring of Optical Fiber Bend Using Artificial Neural Networks Trained with Constellation Data. IEEE Netw. Lett. 2019, 1, 60–62. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Z.F.; Li, J.; Cai, M.Y.; Lin, Y.; Zhang, W.J. On Membership of Black-Box or White-Box of Artificial Neural Network Models. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE 11th Conference on Industrial Electronics and Applications (ICIEA), Hefei, China, 5–7 June 2016; pp. 1400–1404. [Google Scholar]

- Demidova, G.; Justo, J.J.; Lukichev, D.; Poliakov, N.; Anuchin, A. Neural Network Models for Predicting Magnetization Surface Switched Reluctance Motor: Classical, Radial Basis Function, and Physics-Informed Techniques. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 54987–54996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Z. A High-Efficient Hybrid Physics-Informed Neural Networks Based on Convolutional Neural Network. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2021, 33, 5514–5526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; Suh, T. Speculative Backpropagation for CNN Parallel Training. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 215365–215374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Ma, G.; Yao, C.; Sun, Z.; Xu, S. Current Sensor Fault Detection and Identification for PMSM Drives Using Multichannel Global Maximum Pooling CNN. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2024, 39, 10311–10325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, B.; Zhang, S.; Su, J.; Cui, H. Fault Diagnosis for Inverter-Fed Motor Drives Using One Dimensional Complex-Valued Convolutional Neural Network. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 117678–117690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rumelhart, D.; Hinton, G.; Williams, R. Learning representations by back-propagating errors. Nature 1986, 323, 533–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Villiers, J.; Barnard, E. Backpropagation neural nets with one and two hidden layers. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. 1993, 4, 136–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Efe, M.O.; Kaynak, O. A general backpropagation algorithm for feedforward neural networks learning. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. 2002, 13, 251–259. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, J.; Wang, W.; Ning, Z.; Venugopal, P.; Popovic, J.; Rietveld, G. High-Frequency Core Loss Modeling Based on Knowledge-Aware Artificial Neural Network. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2024, 39, 1968–1973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inoue, K.; Ichige, K.; Nagao, T.; Hayashi, T. Learning-Based Prediction Method for Radio Wave Propagation Using Images of Building Maps. IEEE Antennas Wirel. Propag. Lett. 2022, 21, 124–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Z.; Chen, X.; Shen, Y.; Su, X.; Xiao, D.; Abel, D.; Zhao, H. Plant-Physics-Guided Neural Network Control for Permanent Magnet Synchronous Motors. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Signal Process. 2025, 19, 74–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameters | Symbol | Value |

|---|---|---|

| Input voltage | Vin | 200 V |

| Resistors | R1, R2, R3, R4 | 60 Ω |

| The number of neurons in the input layer-1 | i | 5 |

| The number of neurons in the first hidden layer-1 | j | 9 |

| The number of neurons in the second hidden layer-1 | k | 9 |

| The number of neurons in the output layer-1 | l | 1 |

| Learning rate | η | 0.001 |

| The number of training iterations | Epoch | 100 |

| early training stopping criterion | MSE < MSEmin | 5 μ |

| Parameters | Value/Model | Position |

|---|---|---|

| DSP board | TMS320F28335 | Control |

| Input voltage | 200 V | Input |

| SMPS | CS30-5, CS30-1212 | SMPS |

| Load resistor | 60 Ω | Resistor |

| Voltage sensor | 800 Vmax | Sensor |

| Current sensor | 25 Amax | Sensor |

| Sampling rate | 100 μs | Control |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kim, G.; Bak, Y. Forward and Backpropagation-Based Artificial Neural Network Modeling Method for Power Conversion System. Electronics 2025, 14, 4718. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14234718

Kim G, Bak Y. Forward and Backpropagation-Based Artificial Neural Network Modeling Method for Power Conversion System. Electronics. 2025; 14(23):4718. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14234718

Chicago/Turabian StyleKim, Gyuri, and Yeongsu Bak. 2025. "Forward and Backpropagation-Based Artificial Neural Network Modeling Method for Power Conversion System" Electronics 14, no. 23: 4718. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14234718

APA StyleKim, G., & Bak, Y. (2025). Forward and Backpropagation-Based Artificial Neural Network Modeling Method for Power Conversion System. Electronics, 14(23), 4718. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14234718