A Novel Color Image Encryption Method Based on Hierarchical Surrogate-Assisted Optimization

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Designed a fitness function for image encryption suitable for metaheuristic algorithms;

- Proposed an adaptive hierarchical surrogate-assisted differential evolution algorithm (HSADE-IQUA) that combines global and local search. Further applied to the Chen hyperchaotic system and DNA encoding, the HSADE-IQUA-DNA image encryption algorithm was proposed;

- We tested the performance of HSADE-IQUA from multiple perspectives, including parameter sensitivity testing, benchmark function testing, and statistical analysis. The test results validated HSADE-IQUA’s excellent performance;

- We conducted experiments on benchmark images, deep learning training images with anchor boxes, and real remote sensing images using the proposed HSADE-IQUA-DNA. The experimental results demonstrate that HSADE-IQUA-DNA fully preserves image information and is resistant to exhaustive, noise, and cropping attacks.

2. Related Works

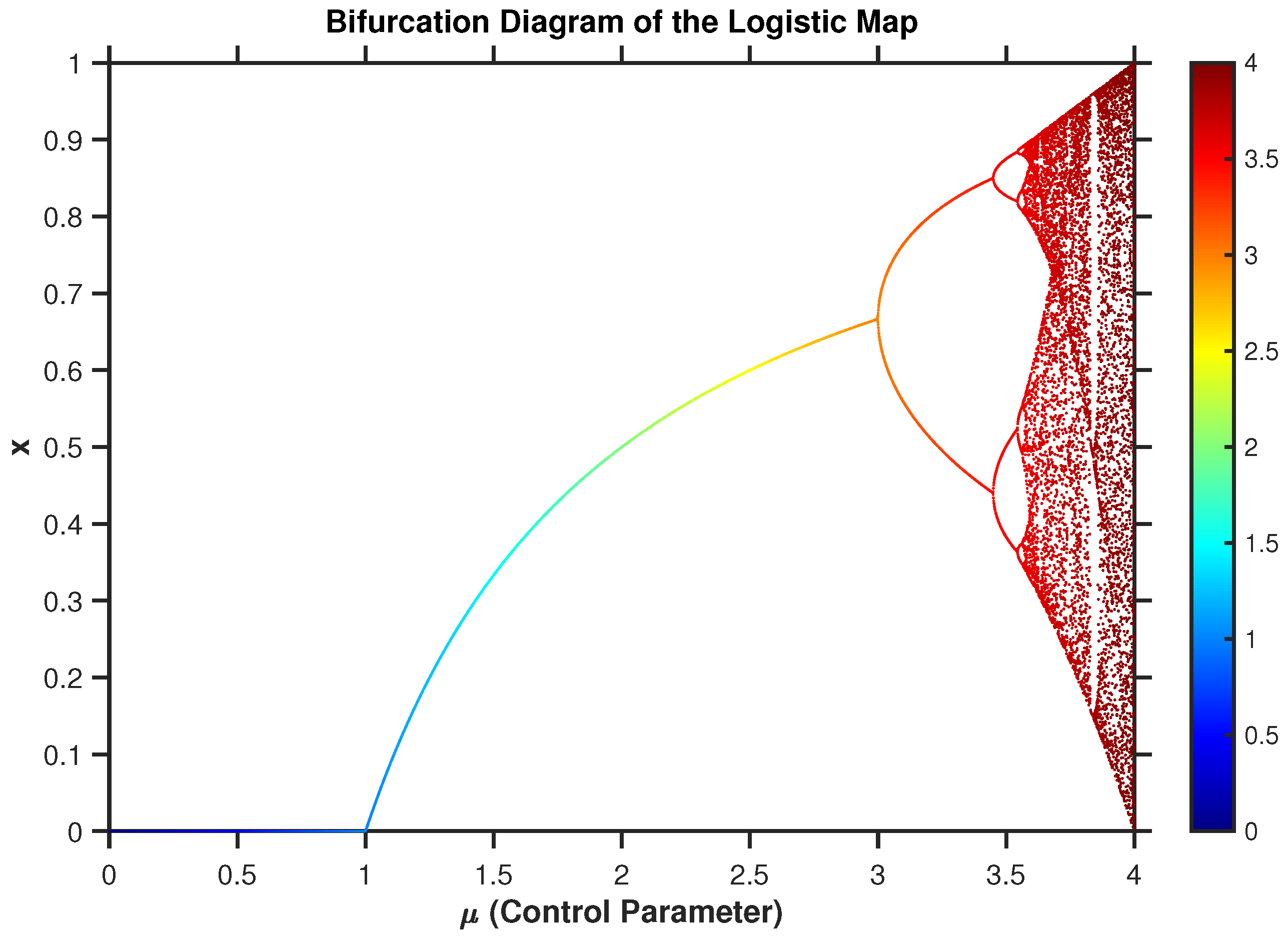

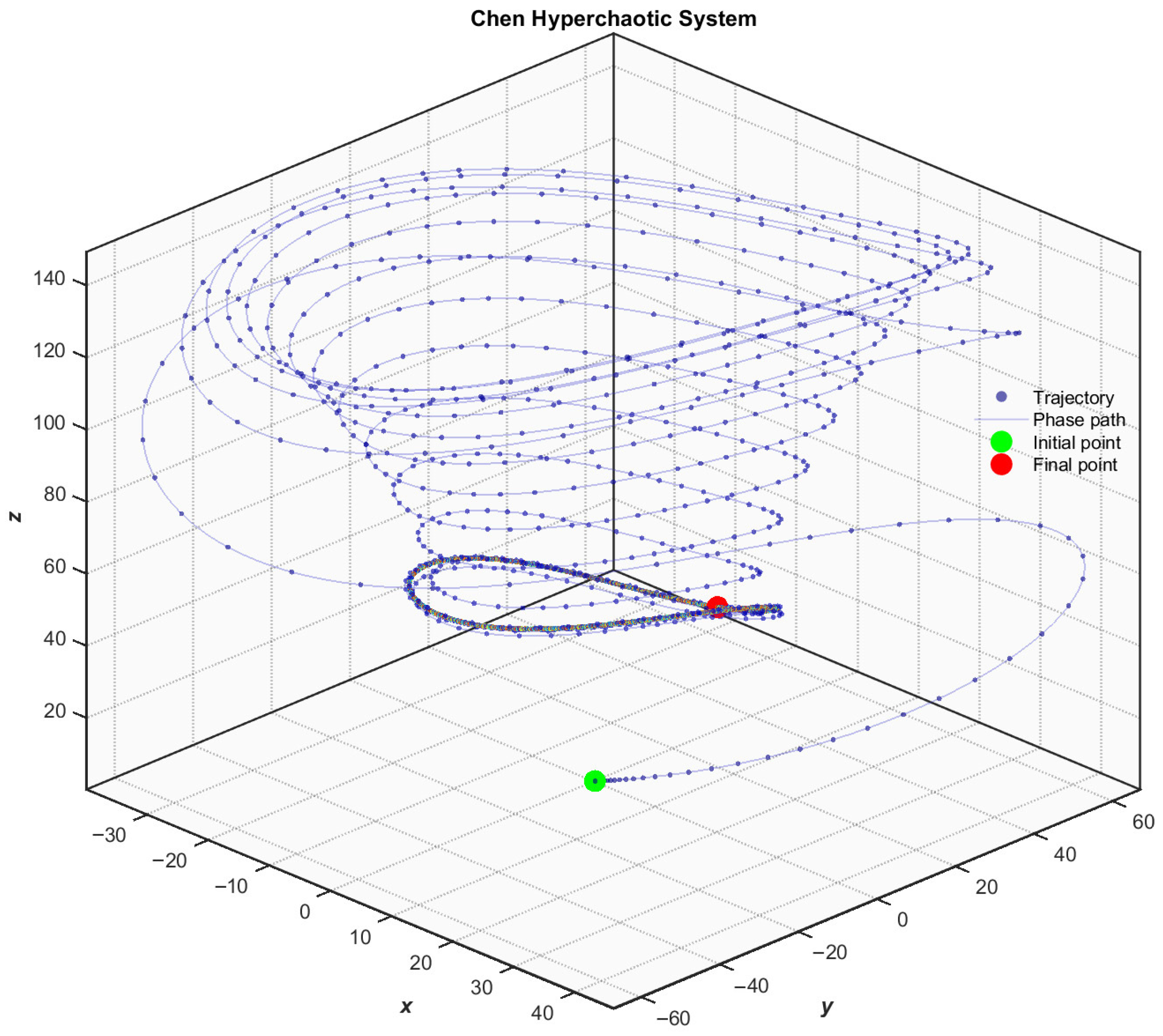

2.1. Chaos Theory

2.2. DNA Coding Rules

2.3. Differential Evolution (DE)

2.4. QUasi-Affine TRansformation Evolution (QUATRE)

2.5. Radial Basis Function

3. Proposed Method

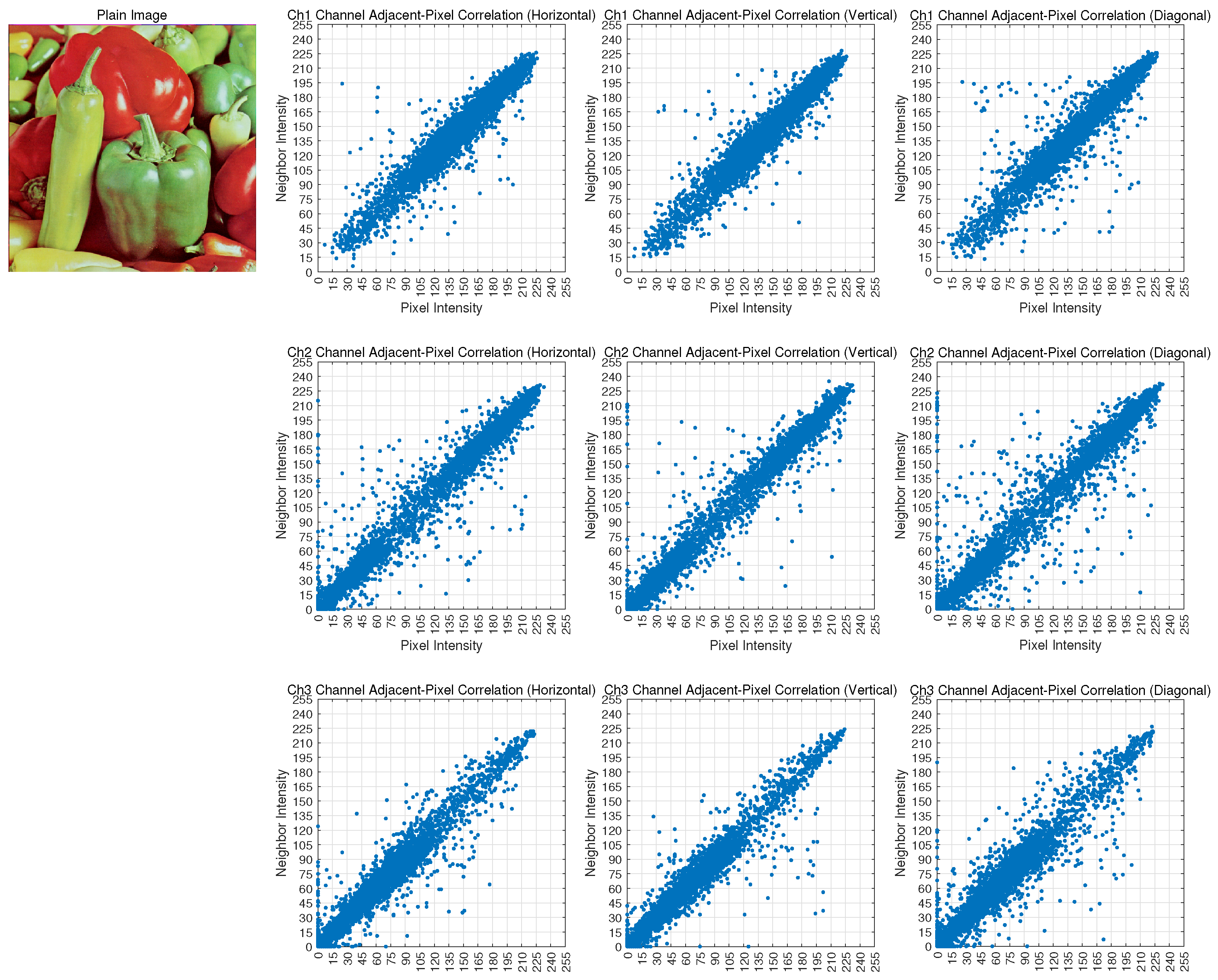

3.1. Fitness Function Based on Pixel Correlation

- (1)

- Reliance on a single information entropy measure.

- (2)

- There is a conflict in the linear weighted combination.

- (3)

- Ignoring the channel coupling of color images.

3.2. Adaptive Hierarchical Assisted Agent Differential Evolution Algorithm (HSADE-IQUA)

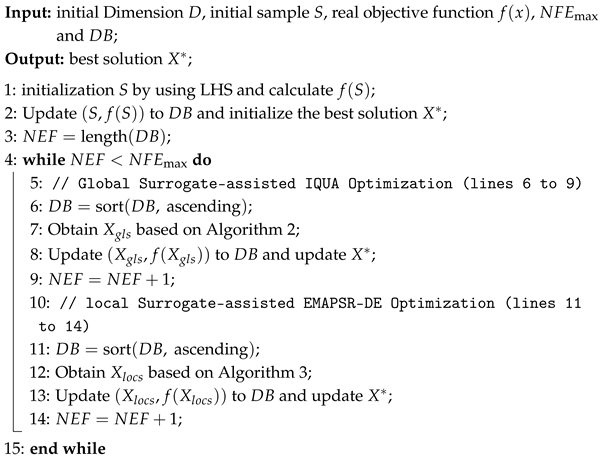

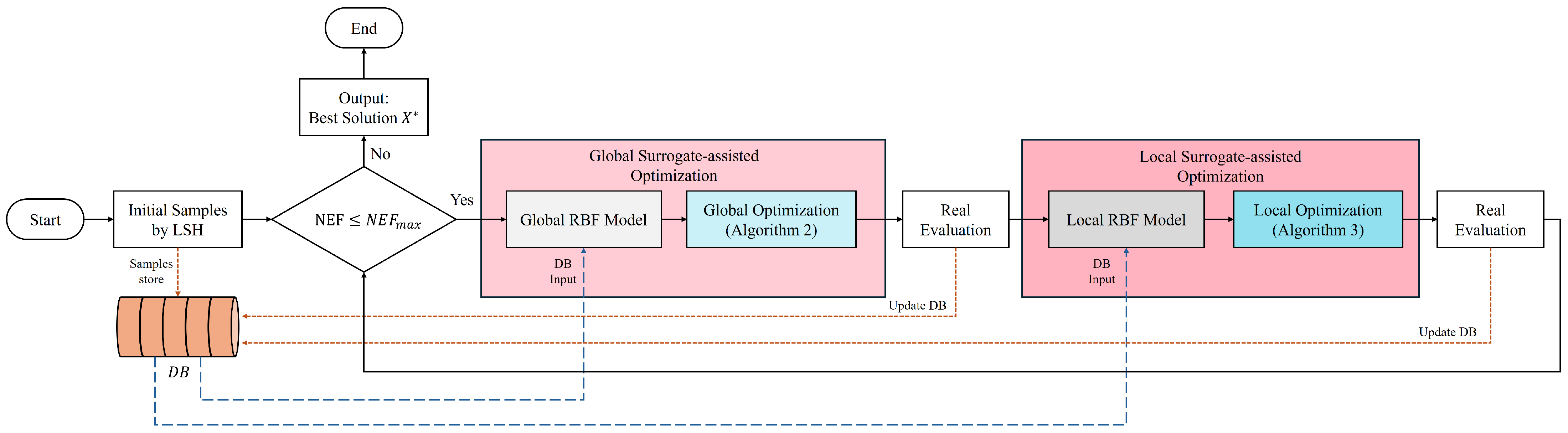

| Algorithm 1: Pseudocode of HSADE-IQUA |

|

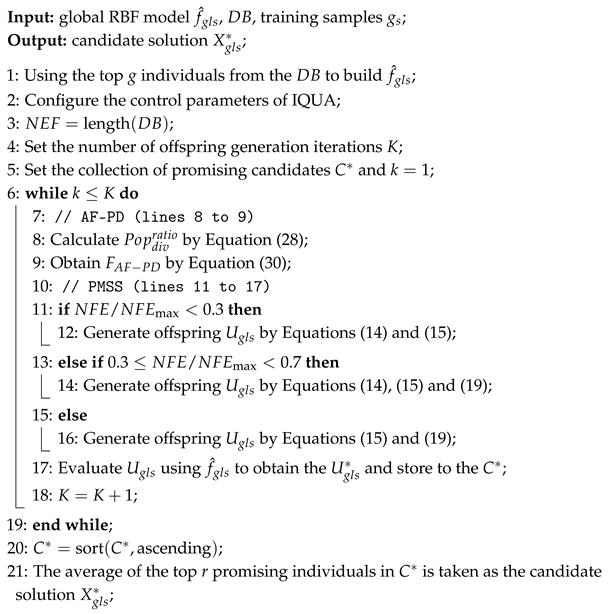

| Algorithm 2: Pseudocode of IQUA |

|

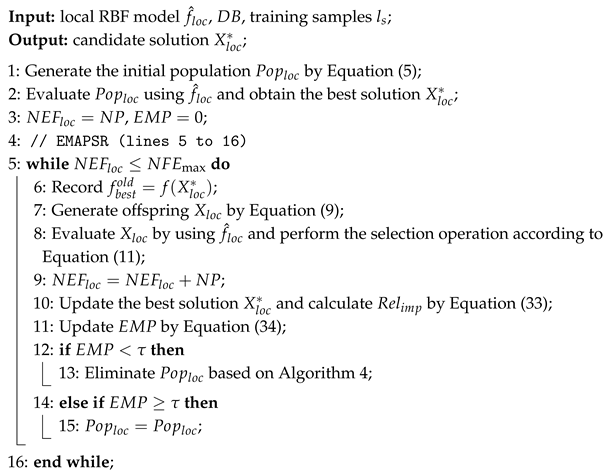

| Algorithm 3: Pseudocode of EMAPSR-DE |

|

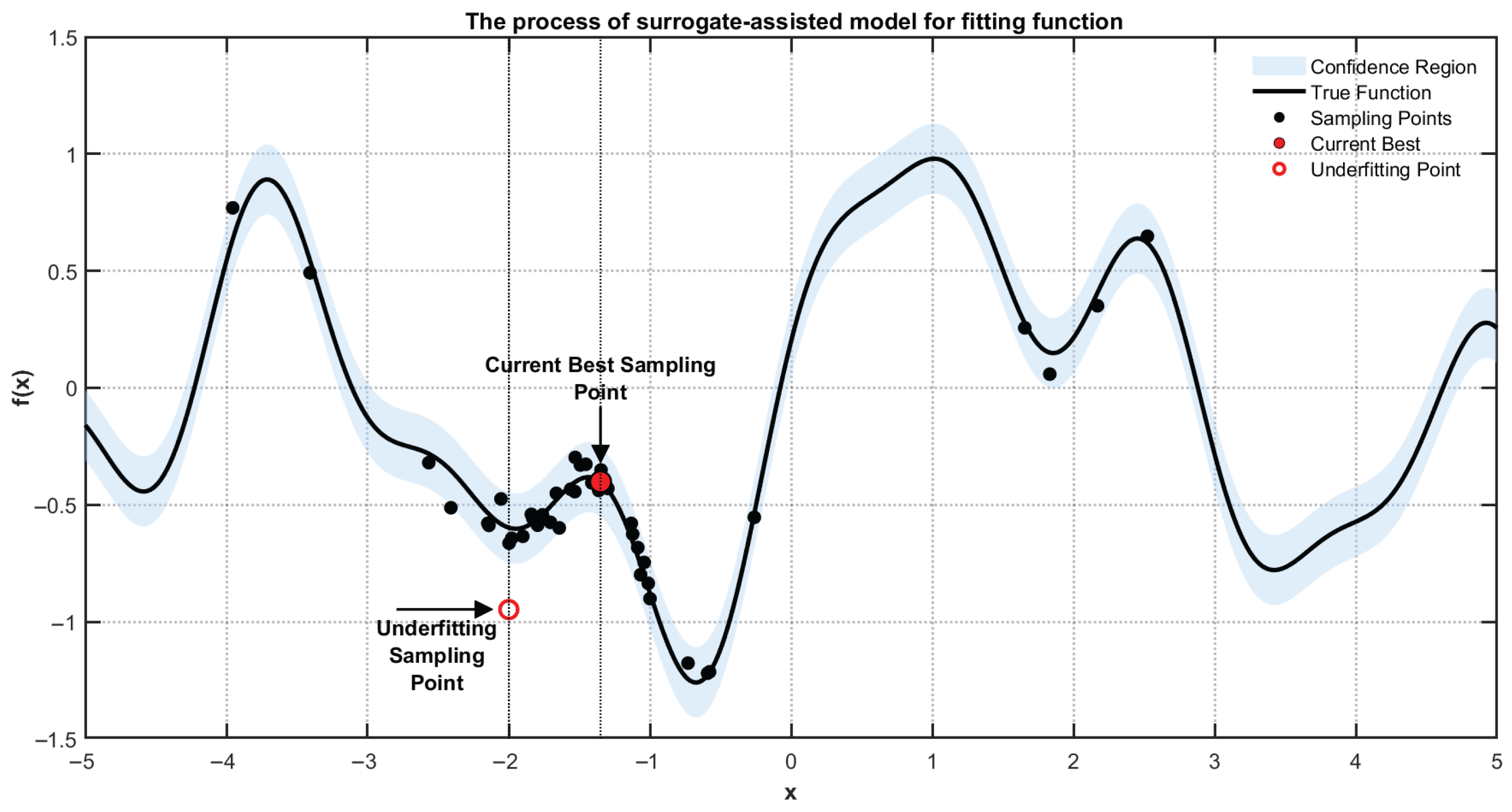

3.2.1. Global Surrogate-Assisted Optimization (IQUA)

- (1)

- AF-PD

- (2)

- PMSS

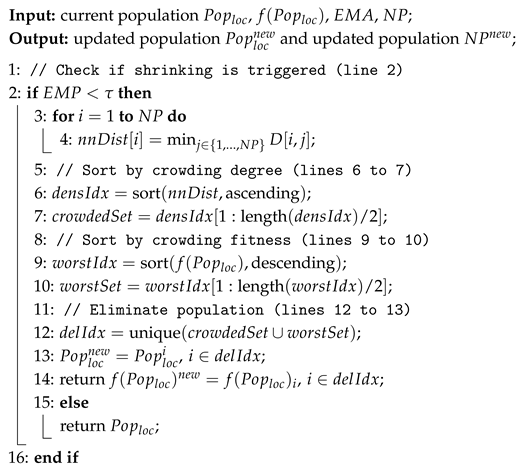

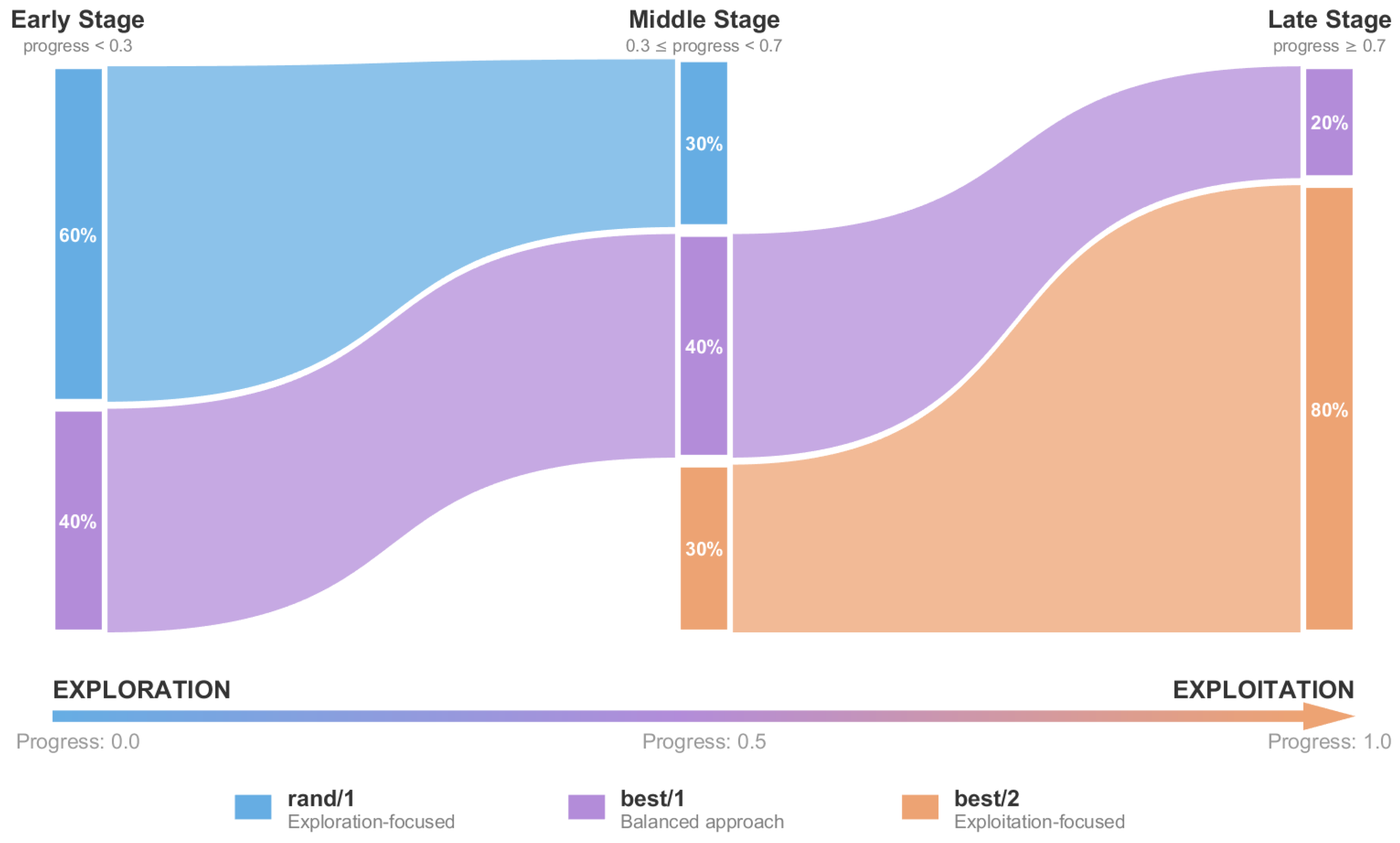

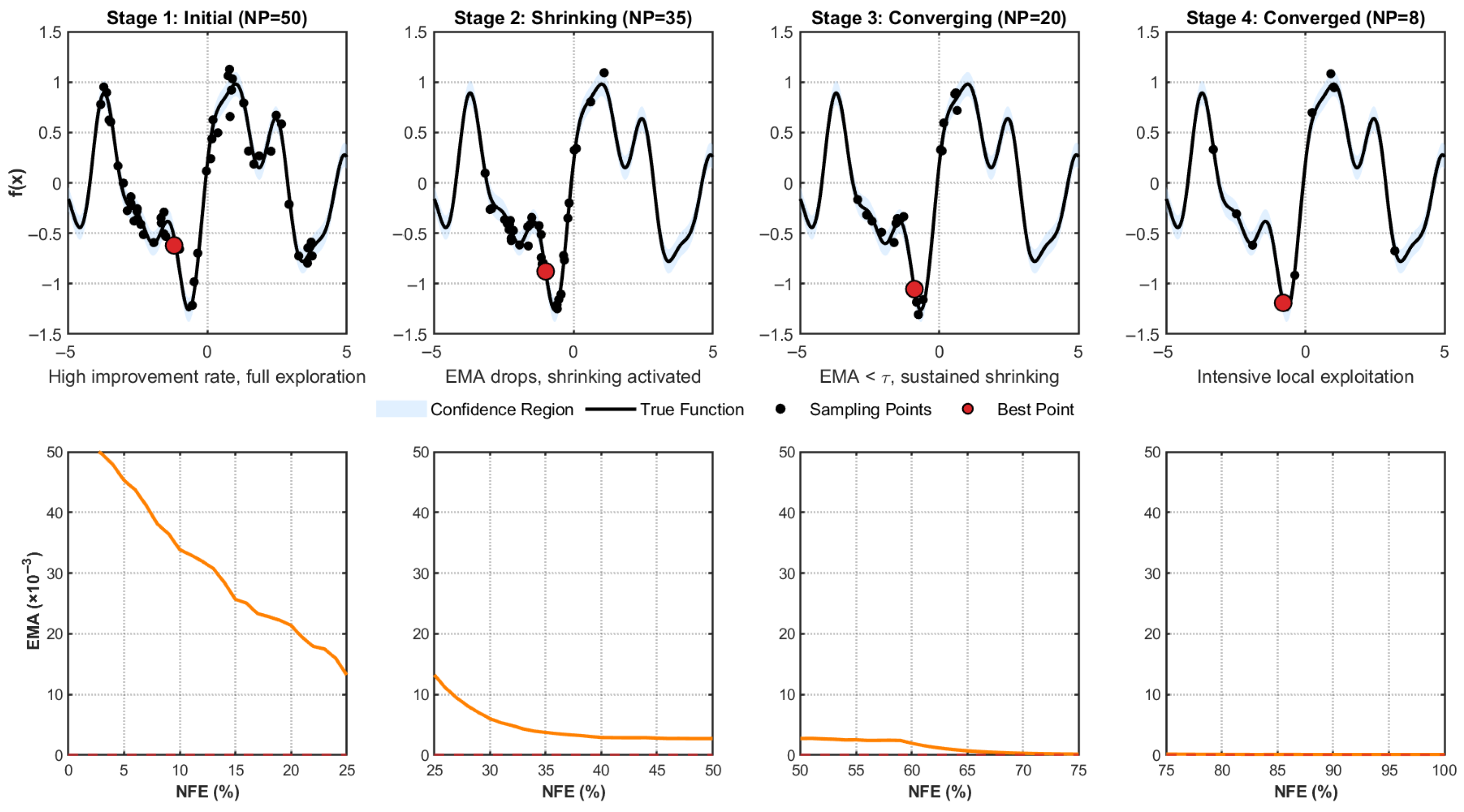

3.2.2. Local Surrogate-Assisted Optimization (EMAPSR-DE)

| Algorithm 4: Pseudocode of EMAPSR |

|

3.2.3. Computational Complexity of HSADE-IQUA

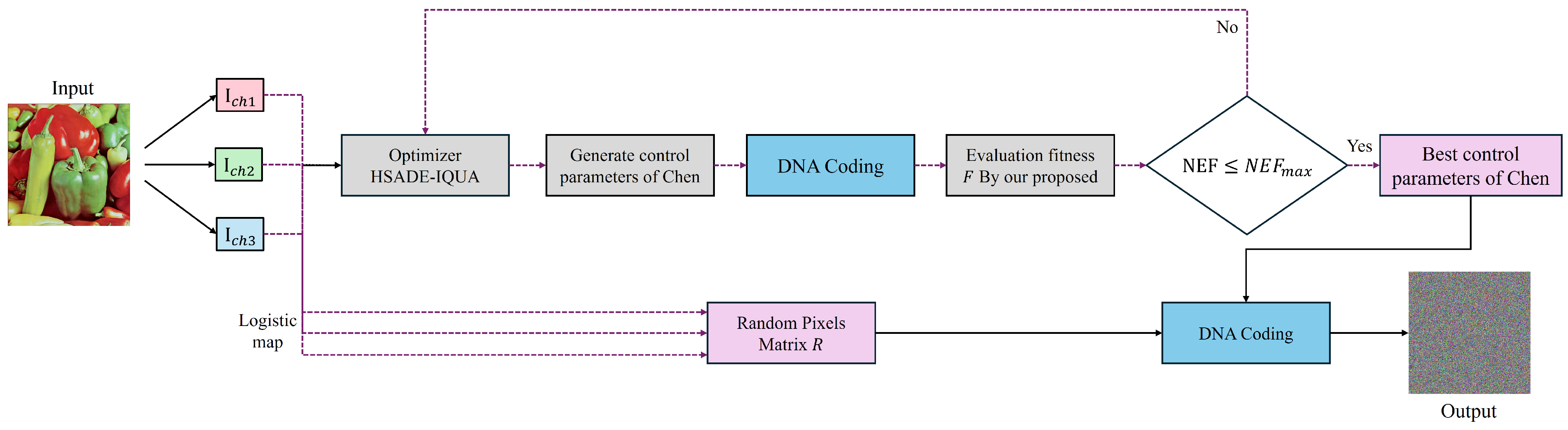

3.3. HSADE-IQUA Optimized Image Encryption Algorithm (HSADE-IQUA-DNA))

- (1)

- Pixel acquisition

- (2)

- Chaos key initialization

- (3)

- HSADE-IQUA Optimization

- (4)

- Image decryption

4. Experiment and Analysis

4.1. Benchmark Results and Analysis of SAEAs

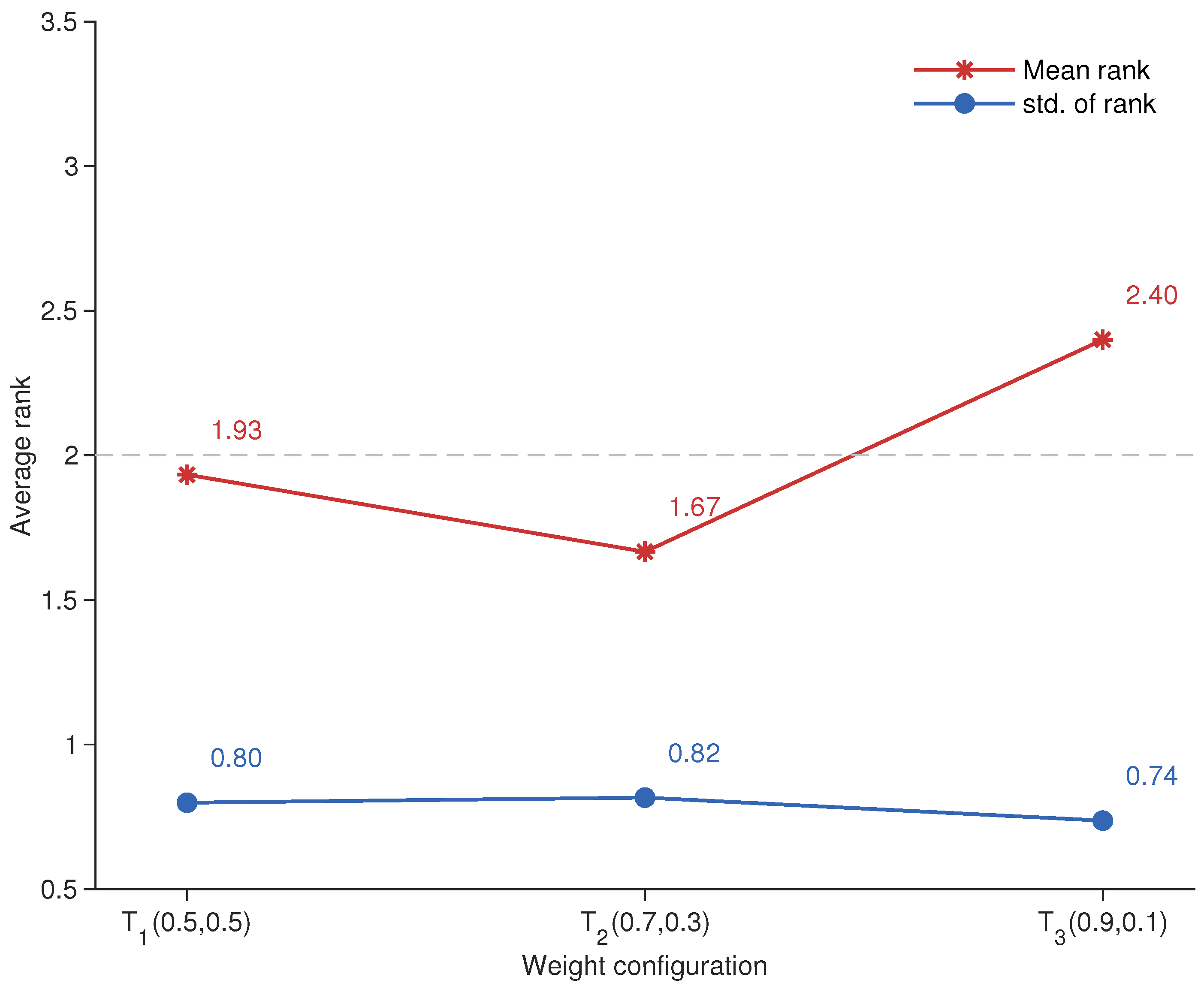

4.1.1. Parameter Sensitivity Analysis

4.1.2. Benchmark Analysis

4.2. Image Encryption Experimental Results and Analysis

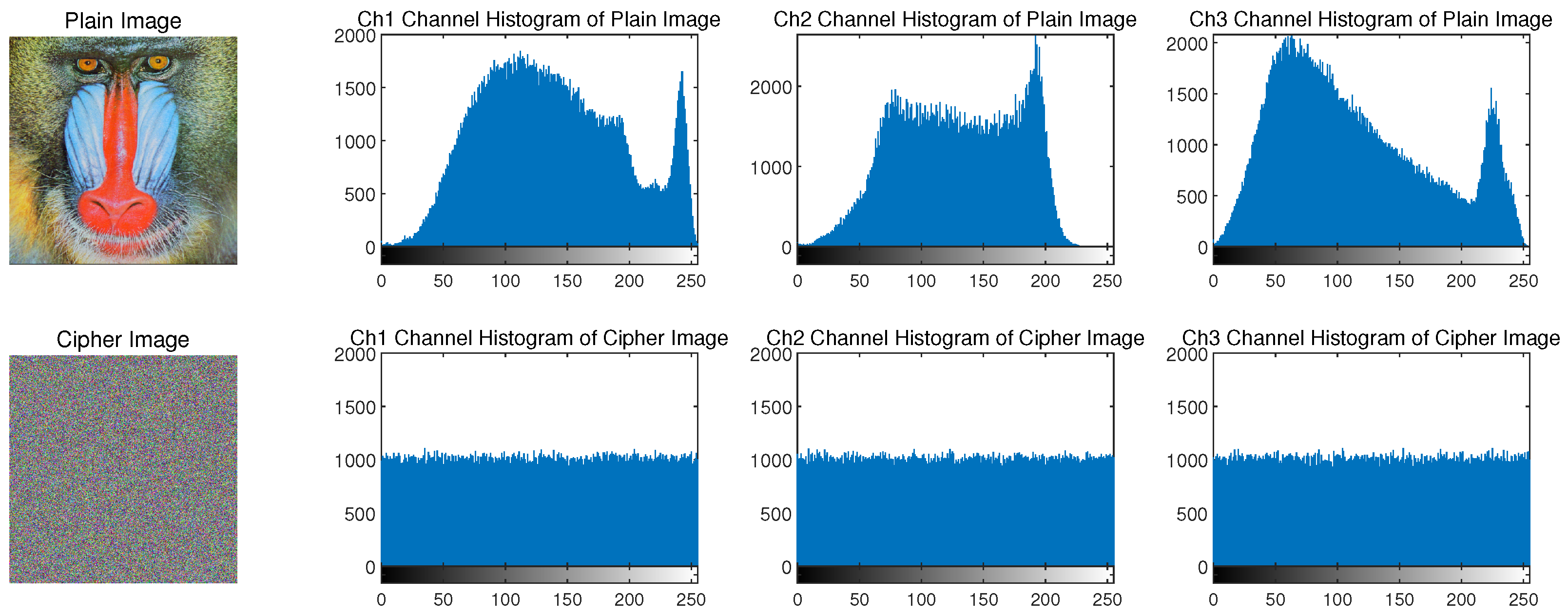

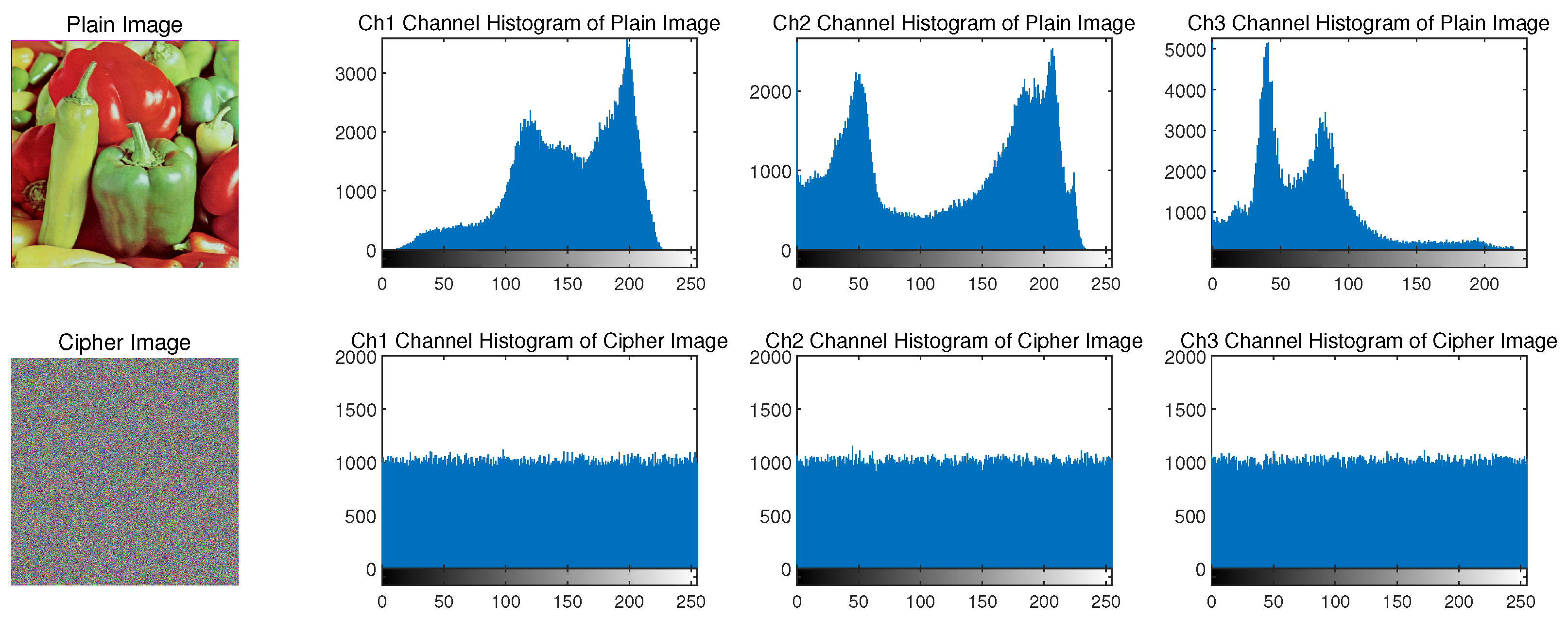

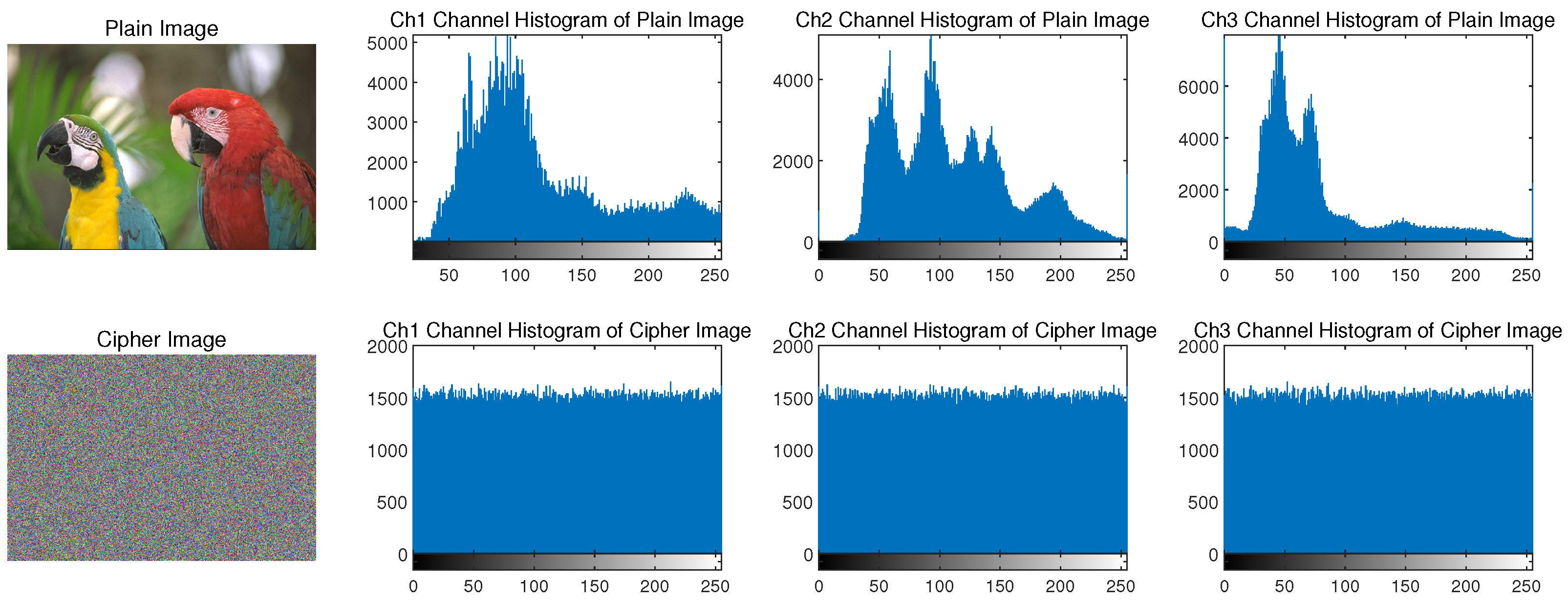

4.2.1. Standard Computer Image Experiment Results and Analysis

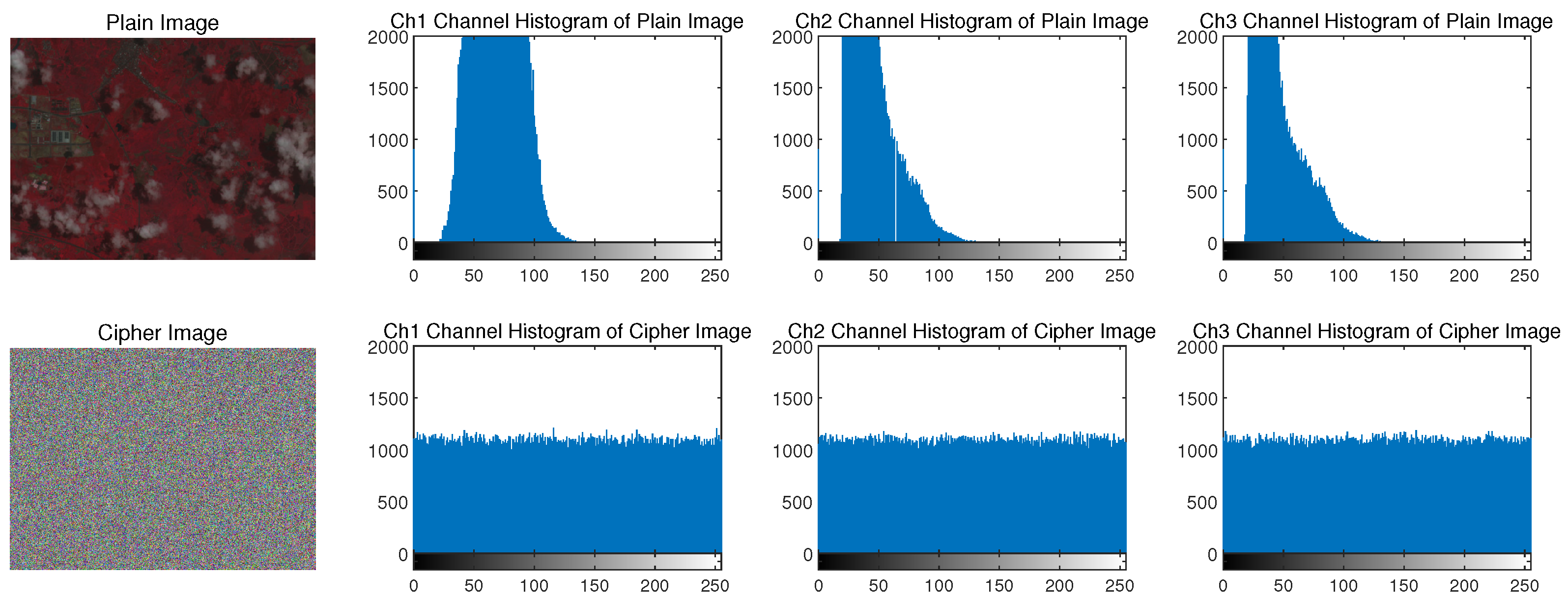

- (1)

- Histogram Statistics Experiment

- (2)

- Anti-clipping attack experiments

- (3)

- Anti-noise experiments

- (4)

- Key capacity analysis

4.2.2. Experimental Results and Analysis of Object Detection Dataset

4.2.3. Experimental Results and Analysis of Real Remote Sensing Images

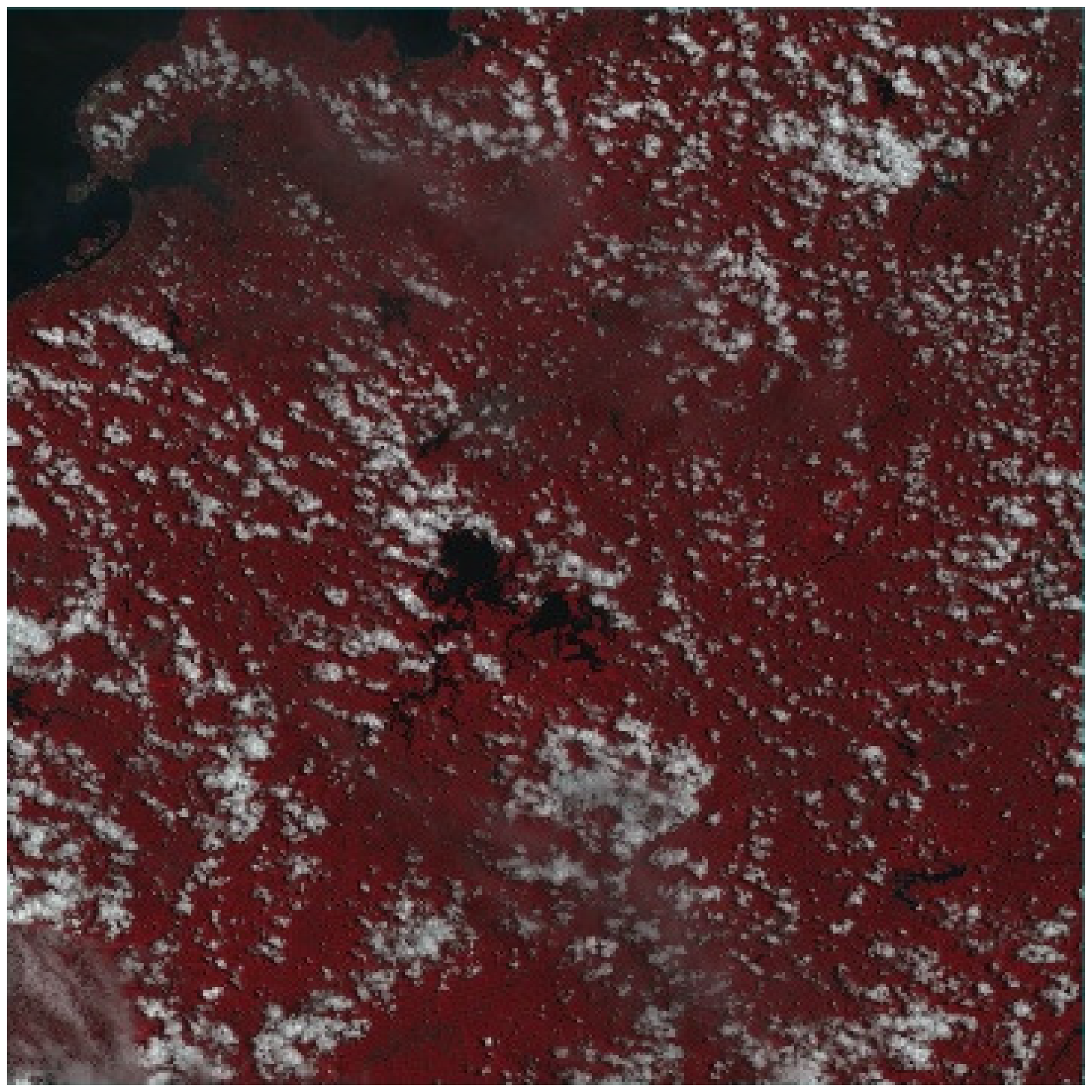

- (1)

- Remote sensing data introduction

- (2)

- Remote sensing image encryption results

- (3)

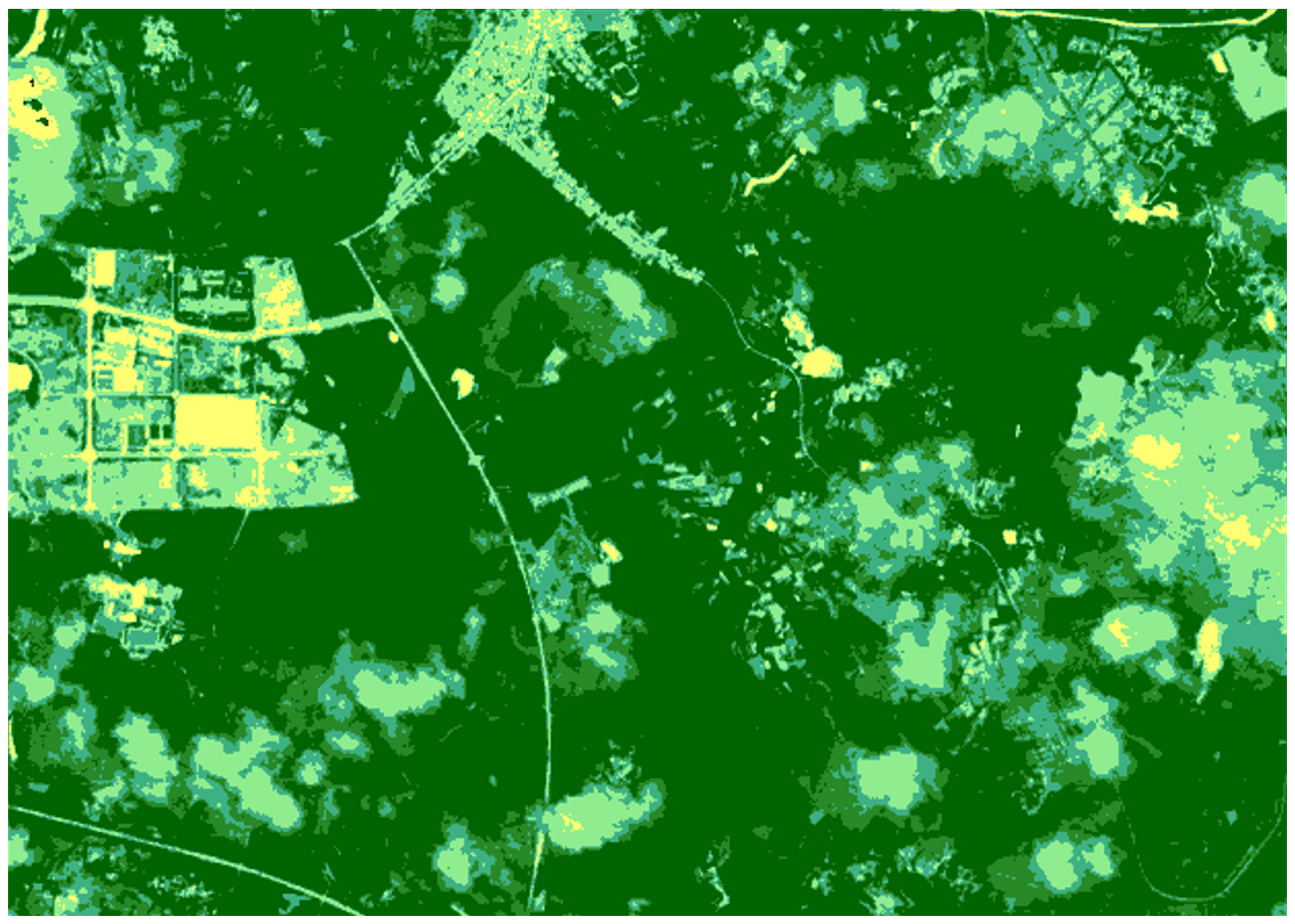

- Analysis of vegetation coverage of decrypted image

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Algorithm | Horizontal | Vertical | Diagonal | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ch1 | Ch2 | Ch3 | Ch1 | Ch2 | Ch3 | Ch1 | Ch2 | Ch3 | |

| HSADE-IQUA | 0.003459 | 0.0033734 | 0.0008789 | 0.0047487 | 0.0045432 | 0.009507 | |||

| Ref. [73] | 0.0018 | 0.0043 | 0.0061 | ||||||

| Ref. [74] | 0.0081 | 0.0225 | 0.0071 | 0.0175 | 0.0338 | ||||

| Ref. [75] | 0.0031 | 0.0012 | |||||||

| Ref. [76] | 0.0113 | 0.0121 | 0.006 | 0.017 | 0.0254 | ||||

| Ref. [77] | 0.0018101 | 0.013868 | 0.011955 | 0.011271 | |||||

| Algorithm | Horizontal | Vertical | Diagonal | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ch1 | Ch2 | Ch3 | Ch1 | Ch2 | Ch3 | Ch1 | Ch2 | Ch3 | |

| HSADE-IQUA-DNA | 0.011275 | 0.010328 | 0.0045465 | 0.0071175 | 0.0032311 | 0.006748 | |||

| Ref. [73] | 0.0081 | 0.007 | 0.0053 | 0.0077 | |||||

| Ref. [78] | |||||||||

| Chen-DNA | 0.0046581 | 0.015098 | 0.01217 | 0.0062174 | 0.017426 | ||||

| DE-DNA | 0.0096859 | 0.0078637 | 0.0031261 | 0.0055742 | 0.023366 | 0.013708 | |||

| SADE-AMSS-DNA | 0.010237 | 0.00062873 | 0.0078786 | 0.030542 | 0.02265 | ||||

| Algorithm | Horizontal | Vertical | Diagonal | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ch1 | Ch2 | Ch3 | Ch1 | Ch2 | Ch3 | Ch1 | Ch2 | Ch3 | |

| HSADE-IQUA-DNA | 0.0096859 | 0.0078637 | 0.0031261 | 0.0055742 | 0.023366 | 0.013708 | |||

| Chen-DNA | 0.0063536 | 0.03094 | 0.0069991 | 0.003104 | |||||

| DE-DNA | 0.00031537 | 0.017807 | 0.000030707 | 0.0070802 | 0.0042869 | 0.0079813 | 0.009353 | 0.022275 | |

| SADE-AMSS-DNA | 0.0032449 | 0.018599 | 0.019872 | ||||||

| ESAO-DNA | 0.028455 | 0.0061859 | 0.0022043 | 0.005985 | |||||

| AES | 0.0176 | 0.0181 | 0.0079 | 0.0018 | 0.000092764 | 0.0072 | |||

References

- Afzal, I.; Parah, S.A.; Hurrah, N.N.; Song, O. Secure patient data transmission on resource constrained platform. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2024, 83, 15001–15026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alqaralleh, B.A.; Vaiyapuri, T.; Parvathy, V.S.; Gupta, D.; Khanna, A.; Shankar, K. Blockchain-assisted secure image transmission and diagnosis model on Internet of Medical Things Environment. Pers. Ubiquitous Comput. 2024, 28, 17–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Chen, M.; Li, G.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, Z. Secure semantic communications: Fundamentals and challenges. IEEE Netw. 2024, 38, 513–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doss, A.F. Data Privacy & National Security: A Rubik’s Cube of Challenges and Opportunities That Are Inextricably Linked. Duquesne Law Rev. 2021, 59, 231. [Google Scholar]

- Zia, U.; McCartney, M.; Scotney, B.; Martinez, J.; AbuTair, M.; Memon, J.; Sajjad, A. Survey on image encryption techniques using chaotic maps in spatial, transform and spatiotemporal domains. Int. J. Inf. Secur. 2022, 21, 917–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alghamdi, Y.; Munir, A. Image encryption algorithms: A survey of design and evaluation metrics. J. Cybersecur. Priv. 2024, 4, 126–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeghid, M.; Machhout, M.; Khriji, L.; Baganne, A.; Tourki, R. A modified AES based algorithm for image encryption. Int. J. Comput. Sci. Eng. 2007, 1, 70–75. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Liu, W.; Cao, S.; Zhai, Z.; Nie, X.; Dai, W. Digital image encryption algorithm based on chaos and improved DES. In Proceedings of the 2009 IEEE International Conference on Systems, Man and Cybernetics, San Antonio, TX, USA, 11–14 October 2009; pp. 474–479. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, F.; Lv, Z. A secure image encryption based on spatial surface chaotic system and AES algorithm. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2022, 81, 3959–3979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orsdemir, A.; Altun, H.O.; Sharma, G.; Bocko, M.F. On the security and robustness of encryption via compressed sensing. In Proceedings of the MILCOM 2008—2008 IEEE Military Communications Conference, San Diego, CA, USA, 16–19 November 2008; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.; Ren, Y.; Feng, G.; Qian, Z. Compressing encrypted image using compressive sensing. In Proceedings of the 2011 Seventh International Conference on Intelligent Information Hiding and Multimedia Signal Processing, Dalian, China, 14–16 October 2011; pp. 222–225. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, N.; Zhang, A.; Zheng, F.; Gong, L. Novel image compression–encryption hybrid algorithm based on key-controlled measurement matrix in compressive sensing. Opt. Laser Technol. 2014, 62, 152–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abadi, M.; Andersen, D.G. Learning to protect communications with adversarial neural cryptography. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1610.06918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, L.; Du, J.; Fu, C.; Song, W. Image encryption algorithm combining chaotic image encryption and convolutional neural network. Electronics 2023, 12, 3455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fridrich, J. Symmetric ciphers based on two-dimensional chaotic maps. Int. J. Bifurc. Chaos 1998, 8, 1259–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baptista, M. Cryptography with chaos. Phys. Lett. A 1998, 240, 50–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arab, A.; Rostami, M.J.; Ghavami, B. An image encryption method based on chaos system and AES algorithm. J. Supercomput. 2019, 75, 6663–6682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.; Wang, E.; Zhao, B. Image encryption scheme with compressed sensing based on a new six-dimensional non-degenerate discrete hyperchaotic system and plaintext-related scrambling. Entropy 2021, 23, 291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Liu, C. A novel and effective image encryption algorithm based on chaos and DNA encoding. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2017, 76, 6229–6245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, Y.; Xue, B.; Mesejo, P.; Cagnoni, S.; Zhang, M. A survey on evolutionary computation for computer vision and image analysis: Past, present, and future trends. IEEE Trans. Evol. Comput. 2022, 27, 5–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, M.; Singh, S.; Kaur, M. Computational image encryption techniques: A comprehensive review. Math. Probl. Eng. 2021, 2021, 5012496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, C.; Zhang, Y.; Gong, D.; Ji, X. A review of surrogate-assisted evolutionary algorithms for expensive optimization problems. Expert Syst. Appl. 2023, 217, 119495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Y. Surrogate-assisted evolutionary computation: Recent advances and future challenges. Swarm Evol. Comput. 2011, 1, 61–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamadi, S.J.; Mohammed, E.A. Chaotic Systems in Cryptography: An Overview of Feature-Based Methods. Al-Salam J. Eng. Technol. 2025, 4, 164–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, F.; Jhangeer, A.; Muddassar, M. Comprehensive classification of multistability and Lyapunov exponent with multiple dynamics of nonlinear Schrödinger equation. Nonlinear Dyn. 2025, 113, 10335–10364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benkouider, K.; Sambas, A.; Bonny, T.; Al Nassan, W.; Moghrabi, I.A.; Sulaiman, I.M.; Hassan, B.A.; Mamat, M. A comprehensive study of the novel 4D hyperchaotic system with self-exited multistability and application in the voice encryption. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 12993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Ueta, T. Yet another chaotic attractor. Int. J. Bifurc. Chaos 1999, 9, 1465–1466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, F.Q.; Wu, G. A color image encryption and decryption scheme based on extended DNA coding and fractional-order 5D hyper-chaotic system. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 254, 124413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Storn, R.; Price, K. Differential evolution–a simple and efficient heuristic for global optimization over continuous spaces. J. Glob. Optim. 1997, 11, 341–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, C.; Meng, Z. A survey on expensive optimization problems using differential evolution. Appl. Soft Comput. 2025, 170, 112727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Jesús Rubio, J.; Orozco, E.; Cordova, D.A.; Hernandez, M.A.; Rosas, F.J.; Pacheco, J. Observer-based differential evolution constrained control for safe reference tracking in robots. Neural Netw. 2024, 175, 106273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, P.; Rustam, F.; Kanwal, K.; Aljedaani, W.; Alfarhood, S.; Safran, M.; Ashraf, I. Detecting thyroid disease using optimized machine learning model based on differential evolution. Int. J. Comput. Intell. Syst. 2024, 17, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Lu, G.; Yan, X.; Xia, P.; Chen, Z.; Wu, D. A differential evolution optimized hybrid XGBoost for accurate carbon emission prediction. Environ. Model. Softw. 2025, 193, 106627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Z.; Sun, L.; Matsveichuk, N.; Sotskov, Y.; Jiang, S.; Yu, Y. Differential evolution based on individual information parameter setting and diversity measurement of aggregated distribution. Swarm Evol. Comput. 2025, 92, 101793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, S.; Wang, Y.; Yan, Y.; Zhao, J.; Gao, Z. Self-adaptive enhanced learning differential evolution with surprisingly efficient decomposition approach for parameter identification of photovoltaic models. Energy Convers. Manag. 2024, 308, 118387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brest, J.; Greiner, S.; Boskovic, B.; Mernik, M.; Zumer, V. Self-adapting control parameters in differential evolution: A comparative study on numerical benchmark problems. IEEE Trans. Evol. Comput. 2006, 10, 646–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Sanderson, A.C. JADE: Adaptive differential evolution with optional external archive. IEEE Trans. Evol. Comput. 2009, 13, 945–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Cai, Z.; Zhang, Q. Differential evolution with composite trial vector generation strategies and control parameters. IEEE Trans. Evol. Comput. 2011, 15, 55–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Z.; Pan, J.S. HARD-DE: Hierarchical archive based mutation strategy with depth information of evolution for the enhancement of differential evolution on numerical optimization. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 12832–12854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Z.; Pan, J.S. QUasi-Affine TRansformation Evolution with External ARchive (QUATRE-EAR): An enhanced structure for differential evolution. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2018, 155, 35–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Z.; Pan, J.S.; Li, X. The quasi-affine transformation evolution (QUATRE) algorithm: An overview. In Proceedings of the The Euro-China Conference on Intelligent Data Analysis and Applications, Malaga, Spain, 9–11 October 2017; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 324–333. [Google Scholar]

- Tanabe, R.; Fukunaga, A. Success-history based parameter adaptation for differential evolution. In Proceedings of the 2013 IEEE Congress on Evolutionary Computation, Cancun, Mexico, 20–23 June 2013; pp. 71–78. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, L.; Ren, C.; Meng, Z. A surrogate-assisted differential evolution with fitness-independent parameter adaptation for high-dimensional expensive optimization. Inf. Sci. 2024, 662, 120246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, H.; Wang, H.; Jin, Y. Surrogate-assisted differential evolution with adaptive multisubspace search for large-scale expensive optimization. IEEE Trans. Evol. Comput. 2022, 27, 1765–1779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Li, J.; Di, X. A novel lossless medical image encryption scheme based on game theory with optimized ROI parameters and hidden ROI position. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 122210–122228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.; Zhou, Q.; Liu, J.; Zhang, Y.; Hui, Z.; Zhang, X. Separable reversible data hiding in encrypted images for remote sensing images. Entropy 2023, 25, 1632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, X.; Gan, Z.; Yuan, K.; Chen, Y.; Liu, X. A novel image encryption scheme based on DNA sequence operations and chaotic systems. Neural Comput. Appl. 2019, 31, 219–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahna, K.; Mohamed, A. A novel image encryption scheme using both pixel level and bit level permutation with chaotic map. Appl. Soft Comput. 2020, 90, 106162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kocak, O.; Erkan, U.; Toktas, A.; Gao, S. PSO-based image encryption scheme using modular integrated logistic exponential map. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 237, 121452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferdush, J.; Mondol, G.; Prapti, A.P.; Begum, M.; Sheikh, M.N.A.; Galib, S.M. An enhanced image encryption technique combining genetic algorithm and particle swarm optimization with chaotic function. Int. J. Comput. Appl. 2021, 43, 960–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enayatifar, R.; Abdullah, A.H.; Lee, M. A weighted discrete imperialist competitive algorithm (WDICA) combined with chaotic map for image encryption. Opt. Lasers Eng. 2013, 51, 1066–1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afify, Y.M.; Sharkawy, N.H.; Gad, W.; Badr, N. A new dynamic DNA-coding model for gray-scale image encryption. Complex Intell. Syst. 2024, 10, 745–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olvera-Martinez, L.; Cedillo-Hernandez, M.; Diaz-Rodriguez, C.A.; Faustinos-Morales, L.; Cedillo-Hernandez, A.; Garcia-Ugalde, F.J. Symmetric Grayscale Image Encryption Based on Quantum Operators with Dynamic Matrices. Mathematics 2025, 13, 982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, K.C.; Feng, L.; Jiang, M. Evolutionary transfer optimization-a new frontier in evolutionary computation research. IEEE Comput. Intell. Mag. 2021, 16, 22–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosli, S.J.; Rahim, H.A.; Abdul Rani, K.N.; Ngadiran, R.; Ahmad, R.B.; Yahaya, N.Z.; Abdulmalek, M.; Jusoh, M.; Yasin, M.N.M.; Sabapathy, T.; et al. A hybrid modified method of the sine cosine algorithm using Latin hypercube sampling with the cuckoo search algorithm for optimization problems. Electronics 2020, 9, 1786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellman, R. Dynamic programming. Science 1966, 153, 34–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanabe, R.; Fukunaga, A.S. Improving the search performance of SHADE using linear population size reduction. In Proceedings of the 2014 IEEE Congress on Evolutionary Computation (CEC), Beijing, China, 6–11 July 2014; pp. 1658–1665. [Google Scholar]

- Li, F.; Cai, X.; Gao, L.; Shen, W. A surrogate-assisted multiswarm optimization algorithm for high-dimensional computationally expensive problems. IEEE Trans. Cybern. 2020, 51, 1390–1402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suganthan, P.N.; Hansen, N.; Liang, J.J.; Deb, K.; Chen, Y.P.; Auger, A.; Tiwari, S. Problem Definitions and Evaluation Criteria for the CEC 2005 Special Session on Real-Parameter Optimization; KanGAL Report Number 2005005; Kanpur Genetic Algorithms Laboratory: Kanpur, India, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Wilcoxon, F. Individual comparisons by ranking methods. In Breakthroughs in Statistics: Methodology and Distribution; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1992; pp. 196–202. [Google Scholar]

- Friedman, M. The use of ranks to avoid the assumption of normality implicit in the analysis of variance. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1937, 32, 675–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, K.C.; Goh, C.K.; Yang, Y.; Lee, T.H. Evolving better population distribution and exploration in evolutionary multi-objective optimization. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2006, 171, 463–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kůdela, J.; Matoušek, R. Combining Lipschitz and RBF surrogate models for high-dimensional computationally expensive problems. Inf. Sci. 2023, 619, 457–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Tan, Y.; Zeng, J.; Sun, C.; Jin, Y. Surrogate-assisted hierarchical particle swarm optimization. Inf. Sci. 2018, 454, 59–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Wang, G.G.; Song, B.; Wang, P.; Wang, Y. A novel evolutionary sampling assisted optimization method for high-dimensional expensive problems. IEEE Trans. Evol. Comput. 2019, 23, 815–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.Y.; Zhan, Z.H.; Zhang, J. Evolutionary computation for expensive optimization: A survey. Mach. Intell. Res. 2022, 19, 3–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Noonan, J.P.; Agaian, S. NPCR and UACI randomness tests for image encryption. Cyber J. Multidiscip. J. Sci. Technol. J. Sel. Areas Telecommun. (JSAT) 2011, 1, 31–38. [Google Scholar]

- Lakshmi, C.; Nithya, C.; Thenmozhi, K.; Sivaraman, R.; Yasvanthira Sri, D.; Vinizia, B.; Subashini, R.; Meikandan, P.V.; Mahalingam, H.; Amirtharajan, R. Reconfigurable security solution based on hopfield neural network for e-healthcare applications. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 5628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, K.; Wan, G.; Cheng, G.; Meng, L.; Han, J. Object detection in optical remote sensing images: A survey and a new benchmark. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2020, 159, 296–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sapkota, R.; Karkee, M. Comparing YOLOv11 and YOLOv8 for instance segmentation of occluded and non-occluded immature green fruits in complex orchard environment. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2410.19869. [Google Scholar]

- Xue, J.; Su, B. Significant remote sensing vegetation indices: A review of developments and applications. J. Sens. 2017, 2017, 1353691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hameed, K.; Naha, R.; Hameed, F. Digital transformation for sustainable health and well-being: A review and future research directions. Discov. Sustain. 2024, 5, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Y.; Xu, X.; Jiang, Z. A New Chaotic Color Image Encryption Algorithm Based on Memristor Model and Random Hybrid Transforms. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, F.; Wu, G.; Zhang, J. A novel color image encryption algorithm based on fractional-order conservative memristive hyperchaotic system and extended zig-zag transform. J. King Saud Univ. Comput. Inf. Sci. 2025, 37, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- İhsan, A.; Doğan, N. An innovative image encryption algorithm enhanced with the Pan-Tompkins Algorithm for optimal security. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2024, 83, 82589–82619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.; Yang, W.; Yin, Y.; Tian, X.; Li, G.; Deng, X. A color image encryption scheme utilizing a logistic-sine chaotic map and cellular automata. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 21603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Liu, J.; You, Z.; Zhang, T. A novel color image encryption algorithm based on hybrid two-dimensional hyperchaos and genetic recombination. Mathematics 2024, 12, 3457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Dayel, I.; Nadeem, M.F.; Khan, M.A.; Abraha, B.S. An image encryption scheme using 4-D chaotic system and cellular automaton. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 19499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 00 | 00 | 01 | 01 | 10 | 10 | 11 | 11 |

| T | 11 | 11 | 10 | 10 | 01 | 01 | 00 | 00 |

| G | 01 | 10 | 00 | 11 | 00 | 11 | 01 | 10 |

| C | 10 | 01 | 11 | 00 | 11 | 00 | 10 | 01 |

| Decimal | Binary | Extracted Bits |

|---|---|---|

| 85 | 01010101 | Odd bits |

| 170 | 10101010 | Even bits |

| 51 | 00110011 | Low bit pairs |

| 204 | 11001100 | High bit pairs |

| Benchmark Function | Function Type | Range | Optimal Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| = ELLIPSOID | Unimodal Function | [−5.12, 5.12] | 0 |

| = ROSENBROCK | Multimodal Function | [−5.12, 5.12] | 0 |

| = ACKLEY | Multimodal Function | [−2.048, 2.048] | 0 |

| = GRIEWANK | Multimodal Function | [−32.76, 32.76] | 0 |

| = RASTRIGIN | Multimodal Function | [−600, 600] | 0 |

| = CEC05_f11 | Highly Complex Function | [−5, 5] | 90 |

| = CEC05_f19 | Highly Complex Function | [−5, 5] | 10 |

| = CEC05_f20 | Highly Complex Function | [−5, 5] | 10 |

| Problem | Dim | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ELLIPSOID | 30 | 2.099 × 10−8 ± 1.735 × 10−8 | 1.300 × 10−8 ± 8.459 × 10−9 | 1.693 × 10−8 ± 2.387 × 10−8 |

| ELLIPSOID | 50 | 7.236 × 10−5 ± 6.952 × 10−5 | 5.474 × 10−5 ± 5.198 × 10−5 | 4.550 × 10−5 ± 4.471 × 10−5 |

| ELLIPSOID | 100 | 2.802 × 10−1 ± 4.434 × 10−1 | 9.850 × 10−2 ± 1.772 × 10−1 | 1.123 × 10−1 ± 1.878 × 10−1 |

| ROSENBROCK | 30 | 9.711 × 101 ± 8.687 × 101 | 9.715 × 101 ± 8.366 × 101 | 1.147 × 102 ± 8.022 × 101 |

| ROSENBROCK | 50 | 8.218 × 101 ± 1.256 × 102 | 1.660 × 102 ± 1.589 × 102 | 1.113 × 102 ± 1.351 × 102 |

| ROSENBROCK | 100 | 3.459 × 102 ± 2.666 × 102 | 2.924 × 102 ± 2.665 × 102 | 3.945 × 102 ± 3.248 × 102 |

| ACKLEY | 30 | 2.429 × 101 ± 3.119 × 10−1 | 2.434 × 101 ± 3.757 × 10−1 | 2.461 × 101 ± 9.297 × 10−1 |

| ACKLEY | 50 | 4.575 × 101 ± 4.442 × 10−1 | 4.570 × 101 ± 2.886 × 10−1 | 4.591 × 101 ± 4.615 × 10−1 |

| ACKLEY | 100 | 9.778 × 101 ± 2.349 × 10−1 | 9.776 × 101 ± 3.710 × 10−1 | 9.791 × 101 ± 2.086 × 10−1 |

| GRIEWANK | 30 | 8.682 × 10−1 ± 9.683 × 10−1 | 1.187 × 100 ± 1.018 × 100 | 9.357 × 10−1 ± 8.988 × 10−1 |

| GRIEWANK | 50 | 6.104 × 10−1 ± 8.144 × 10−1 | 9.428 × 10−1 ± 1.229 × 100 | 6.112 × 10−1 ± 7.967 × 10−1 |

| GRIEWANK | 100 | 3.661 × 10−2 ± 7.003 × 10−2 | 2.367 × 10−2 ± 1.017 × 10−2 | 3.681 × 10−2 ± 6.136 × 10−2 |

| RASTRIGIN | 30 | 5.049 × 10−3 ± 6.754 × 10−3 | 5.042 × 10−3 ± 9.812 × 10−3 | 5.676 × 10−3 ± 7.977 × 10−3 |

| RASTRIGIN | 50 | 7.102 × 10−3 ± 9.100 × 10−3 | 4.593 × 10−3 ± 1.045 × 10−2 | 1.394 × 10−2 ± 4.557 × 10−2 |

| RASTRIGIN | 100 | 2.079 × 10−2 ± 2.681 × 10−2 | 1.563 × 10−2 ± 6.009 × 10−3 | 1.498 × 10−2 ± 5.939 × 10−3 |

| Problem | Dim | HSADE-IQUA | SADE-AMSS | LSADE | SHPSO | ESAO |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ELLIPSOID | 30D | 1.66 × 10−8 ± 1.18 × 10−8 | 1.68 × 101 ± 1.52 × 101 (+) | 8.47 × 10−3 ± 3.22 × 10−3 (+) | 6.00 × 101 ± 2.48 × 101 (+) | 9.43 × 10−5 ± 2.75 × 10−5 (+) |

| ELLIPSOID | 50D | 5.53 × 10−5 ± 5.32 × 10−5 | 3.54 × 101 ± 2.53 × 101 (+) | 1.51 × 100 ± 1.52 × 100 (+) | 2.31 × 102 ± 7.38 × 101 (+) | 3.65 × 10−1 ± 4.31 × 10−1 (+) |

| ELLIPSOID | 100D | 1.05 × 10−1 ± 2.31 × 10−1 | 9.00 × 101 ± 5.42 × 101 (+) | 1.16 × 102 ± 3.49 × 101 (+) | 1.42 × 103 ± 4.47 × 102 (+) | 5.40 × 102 ± 6.59 × 101 (+) |

| ROSENBROCK | 30D | 2.37 × 101 ± 1.30 × 100 | 1.24 × 102 ± 6.24 × 101 (+) | 2.73 × 101 ± 1.03 × 100 (+) | 9.66 × 101 ± 3.91 × 101 (+) | 2.44 × 101 ± 1.02 × 100 (+) |

| ROSENBROCK | 50D | 4.59 × 101 ± 8.28 × 10−1 | 1.93 × 102 ± 8.74 × 101 (+) | 4.79 × 101 ± 1.16 × 100 (+) | 2.24 × 102 ± 9.45 × 101 (+) | 4.73 × 101 ± 1.47 × 100 (+) |

| ROSENBROCK | 100D | 9.78 × 101 ± 3.69 × 10−1 | 4.70 × 102 ± 2.63 × 102 (+) | 1.26 × 102 ± 2.32 × 101 (+) | 6.74 × 102 ± 1.75 × 102 (+) | 2.87 × 102 ± 2.96 × 101 (+) |

| ACKLEY | 30D | 6.31 × 10−1 ± 6.77 × 10−1 | 8.11 × 100 ± 2.80 × 100 (+) | 8.02 × 10−1 ± 9.28 × 10−1 (≈) | 1.00 × 101 ± 1.11 × 100 (+) | 4.56 × 100 ± 1.64 × 100 (+) |

| ACKLEY | 50D | 5.29 × 10−1 ± 1.84 × 10−1 | 8.58 × 100 ± 2.45 × 100 (+) | 8.00 × 100 ± 2.76 × 100 (+) | 1.19 × 101 ± 9.58 × 10−1 (+) | 7.98 × 10−1 ± 1.04 × 100 (≈) |

| ACKLEY | 100D | 1.90 × 10−1 ± 6.98 × 10−3 | 7.83 × 100 ± 2.82 × 100 (+) | 1.46 × 101 ± 1.42 × 100 (+) | 1.29 × 101 ± 6.67 × 10−1 (+) | 7.97 × 100 ± 3.33 × 100 (+) |

| GRIEWANK | 30D | 4.31 × 10−3 ± 7.49 × 10−3 | 5.57 × 101 ± 1.89 × 101 (+) | 5.95 × 10−2 ± 3.61 × 10−2 (+) | 1.14 × 100 ± 9.16 × 10−2 (+) | 9.45 × 10−1 ± 4.55 × 10−2 (+) |

| GRIEWANK | 50D | 2.12 × 10−3 ± 3.87 × 10−3 | 1.92 × 101 ± 1.35 × 101 (+) | 8.36 × 10−1 ± 1.19 × 10−1 (+) | 1.14 × 100 ± 4.96 × 10−2 (+) | 9.29 × 10−1 ± 5.31 × 10−2 (+) |

| GRIEWANK | 100D | 1.83 × 10−2 ± 1.42 × 10−2 | 2.93 × 101 ± 2.58 × 101 (+) | 9.44 × 100 ± 2.62 × 100 (+) | 1.15 × 100 ± 6.47 × 10−2 (+) | 1.99 × 101 ± 2.14 × 100 (+) |

| RASTRIGIN | 30D | 9.41 × 101 ± 8.54 × 101 | 1.06 × 102 ± 3.96 × 101 (+) | 7.13 × 101 ± 1.73 × 101 (+) | 2.56 × 102 ± 1.83 × 101 (+) | 2.49 × 102 ± 2.94 × 101 (+) |

| RASTRIGIN | 50D | 1.49 × 102 ± 3.36 × 101 | 2.62 × 102 ± 4.71 × 101 (+) | 1.51 × 102 ± 1.60 × 102 (+) | 4.72 × 102 ± 3.22 × 101 (+) | 4.42 × 102 ± 2.93 × 101 (+) |

| RASTRIGIN | 100D | 3.04 × 102 ± 2.41 × 102 | 7.36 × 102 ± 9.59 × 101 (+) | 3.82 × 102 ± 7.27 × 101 (+) | 9.80 × 102 ± 3.09 × 101 (+) | 9.83 × 102 ± 2.86 × 101 (+) |

| CEC05_f11 | 30D | 1.32 × 102 ± 2.93 × 100 | 1.35 × 102 ± 2.32 × 100 (≈) | 1.36 × 102 ± 1.50 × 100 (+) | 1.35 × 102 ± 1.88 × 100 (≈) | 1.36 × 102 ± 1.36 × 100 (≈) |

| CEC05_f11 | 50D | 1.63 × 102 ± 4.05 × 100 | 1.71 × 102 ± 2.68 × 100 (≈) | 1.71 × 102 ± 2.66 × 100 (+) | 1.72 × 102 ± 1.80 × 100 (≈) | 1.71 × 102 ± 2.09 × 100 (≈) |

| CEC05_f11 | 100D | 2.64 × 102 ± 2.74 × 100 | 2.63 × 102 ± 2.21 × 100 (≈) | 2.63 × 102 ± 3.93 × 100 (≈) | 2.64 × 102 ± 2.83 × 100 (≈) | 2.62 × 102 ± 2.66 × 100 (≈) |

| CEC05_f19 | 30D | 1.15 × 103 ± 4.62 × 101 | 1.03 × 103 ± 5.76 × 101 (+) | 9.63 × 102 ± 4.21 × 101 (+) | 1.16 × 103 ± 2.84 × 101 (≈) | 9.28 × 102 ± 5.96 × 100 (+) |

| CEC05_f19 | 50D | 9.66 × 102 ± 1.15 × 102 | 1.17 × 103 ± 6.06 × 101 (+) | 1.05 × 103 ± 5.97 × 101 (+) | 1.20 × 103 ± 2.63 × 101 (+) | 9.77 × 102 ± 3.25 × 101 (+) |

| CEC05_f19 | 100D | 9.65 × 102 ± 8.74 × 101 | 1.28 × 103 ± 1.68 × 102 (+) | 1.42 × 103 ± 3.40 × 101 (+) | 1.44 × 103 ± 6.11 × 101 (+) | 1.38 × 103 ± 2.93 × 101 (+) |

| CEC05_f20 | 30D | 1.10 × 103 ± 7.07 × 101 | 1.04 × 103 ± 4.31 × 101 (+) | 9.56 × 102 ± 3.65 × 101 (+) | 1.16 × 103 ± 3.87 × 101 (+) | 9.30 × 102 ± 4.33 × 101 (+) |

| CEC05_f20 | 50D | 9.39 × 102 ± 8.79 × 101 | 1.12 × 103 ± 4.30 × 101 (+) | 1.04 × 103 ± 6.62 × 101 (+) | 1.20 × 103 ± 2.85 × 101 (+) | 9.71 × 102 ± 3.59 × 101 (+) |

| CEC05_f20 | 100D | 9.69 × 102 ± 9.80 × 101 | 1.29 × 103 ± 1.48 × 102 (+) | 1.41 × 103 ± 3.47 × 101 (+) | 1.48 × 103 ± 5.37 × 101 (+) | 1.38 × 103 ± 2.68 × 101 (+) |

| Statistical Tests | Dim | HSADE-IQUA | SADE-AMSS | LSADE | SHPSO | ESAO |

| Friedman rank mean | 30D | 1.88 | 3.75 | 2.38 | 4.38 | 2.62 |

| 50D | 1.25 | 3.75 | 2.5 | 4.88 | 2.62 | |

| 100D | 1.5 | 3 | 3.12 | 4.25 | 3.12 |

| Image Encryption Algorithm | Standard Computer Vision Images | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Baboon | Peppers | kodim23 | |

| HSADE-IQUA-DNA | 4.23 × 10−6 | 6.99 × 10−6 | 2.82 × 10−7 |

| DE-DNA | 2.70 × 10−5 | 2.78 × 10−5 | 3.14 × 10−5 |

| SADE-AMSS-DNA | 4.53 × 10−6 | 8.48 × 10−6 | 7.63 × 10−7 |

| ESAO-DNA | 4.07 × 10−6 | 9.61 × 10−6 | 1.00 × 10−6 |

| Chen-DNA | 6.90 × 10−3 | 4.35 × 10−2 | 9.40 × 10−3 |

| AES | 7.75 × 10−2 | 8.26 × 10−3 | 1.86 × 10−2 |

| Algorithm | Baboon | Peppers | kodim23 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ch1 | Ch2 | Ch3 | Ch1 | Ch2 | Ch3 | Ch1 | Ch2 | Ch3 | |

| Original | 7.7067 | 7.4744 | 7.7520 | 7.3388 | 7.4960 | 7.0583 | 7.4699 | 7.4814 | 7.1650 |

| HSADE-IQUA-DNA | 7.9994 | 7.9994 | 7.9993 | 7.9994 | 7.9995 | 7.9993 | 7.9995 | 7.9996 | 7.9995 |

| DE-DNA | 7.9993 | 7.9994 | 7.9993 | 7.9993 | 7.9993 | 7.9992 | 7.9995 | 7.9995 | 7.9995 |

| SADE-AMSS-DNA | 7.9992 | 7.9992 | 7.9993 | 7.9993 | 7.9993 | 7.9994 | 7.9995 | 7.9995 | 7.9995 |

| ESAO-DNA | 7.9992 | 7.9994 | 7.9992 | 7.9993 | 7.9994 | 7.9994 | 7.9995 | 7.9995 | 7.9996 |

| Chen-DNA | 7.9993 | 7.9994 | 7.999 | 7.9993 | 7.9992 | 7.9991 | 7.9995 | 7.9996 | 7.9996 |

| AES | 7.9993 | 7.9993 | 7.9993 | 7.9993 | 7.9994 | 7.9992 | 7.9995 | 7.9996 | 7.9995 |

| Standard Computer Vision Images | Evaluation Indicators | |

|---|---|---|

| NPCR | UACI | |

| Baboon | 99.6120% | 33.4769% |

| Peppers | 99.6103% | 33.4579% |

| kodim23 | 99.6145% | 33.5077% |

| Band | Wavelength | Bandwidth |

|---|---|---|

| B2 (Blue) | 489 nm | 107 nm |

| B3 (Green) | 560.6 nm | 77 nm |

| B4 (Red) | 666.5 nm | 73 nm |

| B8 (Near-infrared) | 834.6 nm | 162 nm |

| Parameter | B8 | B4 | B3 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Original | Encrypted | Original | Encrypted | Original | Encrypted | |

| Horizontal correlation | 0.95026 | 0.004879 | 0.98103 | −0.0034483 | 0.9832 | −0.004604 |

| Vertical correlation | 0.95777 | −0.010475 | 0.98135 | 0.019821 | 0.98268 | 0.015622 |

| Diagonal correlation | 0.92038 | 0.013708 | 0.96808 | −0.0070606 | 0.97194 | −0.0018774 |

| Channel | Plaintext Information Entropy | Ciphertext Information Entropy |

|---|---|---|

| B8 | 6.0883 | 7.9994 |

| B4 | 5.2168 | 7.9994 |

| B3 | 5.1009 | 7.9993 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liu, G.-Y.; Yu, Y.; Zhao, H.-Q.; Gao, T.-Y.; Chen, Z.-Y. A Novel Color Image Encryption Method Based on Hierarchical Surrogate-Assisted Optimization. Electronics 2025, 14, 4716. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14234716

Liu G-Y, Yu Y, Zhao H-Q, Gao T-Y, Chen Z-Y. A Novel Color Image Encryption Method Based on Hierarchical Surrogate-Assisted Optimization. Electronics. 2025; 14(23):4716. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14234716

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Gao-Yuan, Ying Yu, Hui-Qi Zhao, Tian-Yu Gao, and Zhi-Yang Chen. 2025. "A Novel Color Image Encryption Method Based on Hierarchical Surrogate-Assisted Optimization" Electronics 14, no. 23: 4716. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14234716

APA StyleLiu, G.-Y., Yu, Y., Zhao, H.-Q., Gao, T.-Y., & Chen, Z.-Y. (2025). A Novel Color Image Encryption Method Based on Hierarchical Surrogate-Assisted Optimization. Electronics, 14(23), 4716. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14234716