1. Introduction

In recent decades, computer networks, particularly wireless communications, have undergone remarkable expansion due to continuous technological progress. Advances in microelectronics and transducer design have enabled the development of compact, efficient, and low-cost devices capable of detecting and measuring diverse physical quantities with high accuracy. These innovations have paved the way for wireless sensor networks (WSNs), a transformative technology widely recognized by researchers and industry analysts [

1,

2,

3,

4]. A WSN consists of numerous sensor nodes distributed across a geographical area, each capable of sensing, processing, and transmitting information to a central base station (BS) [

5]. However, transmitting large volumes of data consumes significant energy, directly limiting network lifetime, particularly since nodes rely on small batteries and are often deployed in hard-to-reach areas.

In addition to limited energy and transmission range, wireless sensor networks (WSNs) face several other inherent challenges. These include signal interference from co-channel or adjacent wireless systems, limited memory and processing capabilities of sensor nodes, narrow communication bandwidth, constrained transmission range, and heightened vulnerability to environmental disturbances and cyberattacks. For example, Kenyeres et al. [

6] detail how narrow bandwidth, limited memory, and constrained transmission range degrade WSN reliability and increase susceptibility to noise and external interference. Likewise, Ahmad et al. [

7] highlight how these resource constraints amplify security challenges and make nodes vulnerable to attacks and faults.

To overcome this limitation, various routing strategies have been proposed, each aiming to balance energy consumption and extend network lifetime [

8,

9,

10]. These strategies are generally classified into four families based on logical topology. In flat-based routing [

11], all nodes share equal roles, but flooding often leads to redundancy and overhead. Chain-based routing [

12] reduces transmissions by forming sequential links but increases delay. Tree-based routing [

13] establishes a parent–child hierarchy for data aggregation, while cluster-based routing [

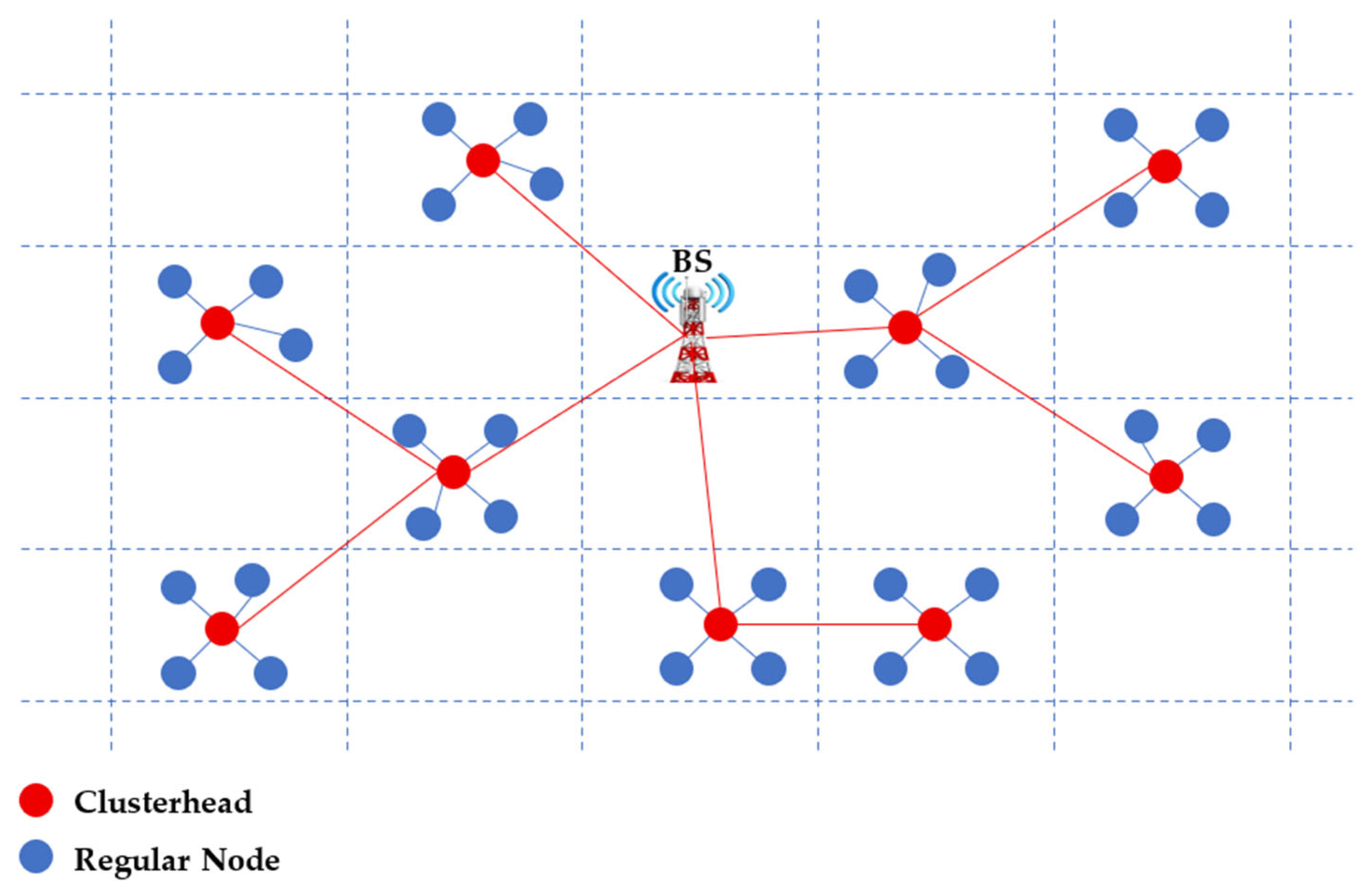

14] organizes nodes into clusters managed by a cluster head (CH) that aggregates and forwards data to the BS, directly or via other CHs. The main challenges lie in selecting optimal CHs, forming balanced clusters, and maintaining efficient communication routes [

15]. Clustering therefore remains central to improving energy efficiency in WSNs.

The pioneering Low-Energy Adaptive Clustering Hierarchy (LEACH) protocol [

14] and its variants—LEACH-C [

16], LEACH-1R [

17,

18], V-LEACH [

19], TL-LEACH [

20], and E-LEACH [

21]—introduced improvements such as centralized control, fixed clustering, backup cluster heads (CHs), hierarchical communication, and energy-aware CH election. Despite these enhancements, they still suffer from unbalanced energy consumption and limited network lifetime. Machine learning-based clustering methods, including k-means [

22,

23] and DBSCAN (Density-based spatial clustering of applications with noise) [

24,

25], have also been investigated. However, k-means requires prior knowledge of the optimal number of clusters, while DBSCAN is highly sensitive to parameter settings. These limitations highlight the need for more adaptive and robust clustering approaches.

Since their emergence in the early 1980s, metaheuristic algorithms have advanced considerably, offering innovative strategies to enhance computational efficiency, solve complex large-scale optimization problems, and provide robust solutions. They have achieved notable success in addressing diverse combinatorial optimization tasks [

26,

27], with examples including Genetic Algorithm (GA), Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO), Ant Colony Optimization (ACO), Artificial Bee Colony (ABC), and Grey Wolf Optimizer (GWO). A recently proposed population-based metaheuristic, the Puma Optimizer Algorithm (PO) [

28], is inspired by the hunting instincts and territorial behaviors of pumas, effectively modeling their exploration and exploitation strategies to solve optimization problems.

Despite extensive research on energy-efficient clustering and routing, many existing protocols still face key limitations. Traditional methods often use fixed clustering structures that fail to adapt to node energy variations, whereas optimization-based algorithms frequently overlook spatial balance or introduce excessive control overhead. Moreover, the interaction between cluster formation and routing remains loosely coupled, leading to uneven energy depletion and reduced coverage over time. To address these challenges, this study introduces a unified clustering and routing framework that integrates the adaptive exploration–exploitation capability of the Puma Optimization Algorithm with grid-based multi-hop routing. The novelty lies in combining optimization-driven cluster head selection with topology-aware routing, enabling dynamic energy balancing, improved scalability, and extended network lifetime.

While many protocols address clustering or routing in isolation, the interaction between these two stages often leads to uneven energy depletion and localized network death. To counteract the inherent limitations of fixed clustering and sub-optimal search strategies employed by protocols like AEO, we propose a novel, unified solution. The PUMA-GRID protocol directly links optimization-driven, energy-aware Cluster Head selection with efficient topology-aware routing to create a scalable, adaptive, and sustainable framework for WSNs, resolving the critical stability challenges faced by existing methods.

The major contributions of this paper are summarized as follows:

A novel clustering protocol, PUMA-GRID, designed to optimize energy consumption and extend network lifetime.

Exploiting the adaptive balance between exploration and exploitation: exploration identifies diverse CH candidates, whereas exploitation refines them into energy-efficient selections. The dynamic switching between these phases prevents premature convergence, improves robustness, and ensures high-quality clustering solutions.

CH selection is guided by a fitness function based on three parameters: residual energy of candidate CHs, distance to the BS, and distance from each node to its CH.

Several experiments were conducted by varying the weight values of the fitness function to evaluate their impacts under three different BS placements.

Performance was assessed using multiple metrics, including residual energy, number of packets sent to the BS, First Node Death (FND), Half Node Death (HND), Last Node Death (LND), energy consumption per round, and the coverage fairness index (measuring the impact of node deaths on coverage).

The proposed protocol was compared against AEO, LEACH, PUMA-SH, and grid-enhanced versions such as AEO-GRID.

Compared with previous studies, this paper addresses several limitations observed in existing clustering and routing approaches. Traditional protocols such as LEACH and MR-LEACH provide simple probabilistic or static cluster-head selection but lack adaptability to energy dynamics. Optimization-based schemes like AEO, SHO-CH, and AVOACS incorporate heuristic search but often ignore spatial routing balance. The proposed PUMA-GRID protocol distinguishes itself by combining the adaptive exploration–exploitation behavior of the Puma Optimization Algorithm with grid-based multi-hop routing, achieving enhanced load balancing, energy preservation, and coverage fairness across varying deployment scenarios.

To further distinguish this study from existing hybrid metaheuristic and multi-hop protocols, the proposed PUMA-GRID framework establishes a coordinated interaction between clustering and routing. PUMA first determines the cluster head structure through its adaptive exploration and exploitation process, and the grid layout then transforms this structure into organized relay paths. This direct coupling between the optimizer’s output and the multi hop forwarding pattern differs from prior works where metaheuristics are used only for CH selection while routing relies on conventional schemes. The result is an integrated clustering routing mechanism that enhances energy balance and extends network lifetime beyond existing hybrid models.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows.

Section 2 reviews clustering protocols that employ metaheuristics for CH selection.

Section 3 presents the PUMA algorithm, while

Section 4 describes the proposed PUMA-GRID protocol.

Section 5 discusses the simulation setup along with the results and analysis. Finally,

Section 6 concludes the paper.

2. Related Work

In AEOWSNC [

29], a clustering protocol inspired by the Atomic Energy Optimization (AEO) algorithm [

30] was introduced to extend the operational lifespan of WSNs. The protocol selects optimal CHs to minimize energy consumption while maintaining clustering efficiency. Each atom represents a candidate CH set, evolving through iterative energy transfer and dissipation operations. The algorithm minimizes an objective function based on total node-to-CH and CH-to-BS distances, with the best solution yielding the lowest value. Strong solutions are preserved, while weaker ones lose energy and are replaced, ensuring a balance between exploration and exploitation. The protocol operates centrally, with CHs transmitting data directly to the BS. Simulations confirm its efficiency over other protocols. However, since the objective function considers only distance and not residual energy, CHs remain in that role until depletion, leading to unbalanced energy usage and reduced coverage. This highlights the critical need for mandatory residual energy consideration and adaptive CH rotation, a requirement addressed directly by the PUMA-GRID fitness function.

The SHO-CH protocol [

31] was proposed as an energy-efficient, cluster-based routing scheme for heterogeneous WSNs. Its goal is to extend network lifetime while balancing energy consumption across nodes. Inspired by the cooperative hunting strategies of spotted hyenas, the protocol balances exploration and exploitation to select CHs that are both energy-efficient and strategically positioned. CH selection is guided by a fitness function incorporating residual energy, distance between nodes and their CHs, and distance from CHs to the BS. After aggregating data from members, CHs transmit either directly to the BS or via intermediate CHs located closer to it. Simulation results demonstrate that SHO-CH improves network lifetime and achieves more equitable energy distribution compared to existing approaches.

The African Vulture Optimization Algorithm-based Energy Efficient Clustering Scheme (AVOACS) [

32] applies the scavenging and foraging behaviors of vultures to optimize CH selection. Each vulture represents a candidate CH configuration, evaluated using a fitness function that considers residual energy, distance to the sink, intra-cluster distance, and a Communication Mode Decider (CMD). After evaluation, the best two vultures guide the others, which update their positions relative to these leaders. A dynamic hunger rate regulates the balance between exploration and exploitation, transitioning the search from global roaming to local refinement strategies modeled on vulture scavenging behaviors. This adaptive mechanism ensures a smooth transition from global search to local refinement, preventing premature convergence. Results show that AVOACS distributes energy more evenly, improves stability, and extends network lifetime compared to conventional protocols.

The EEM-LEACH-ABC protocol [

33] combines LEACH with the Artificial Bee Colony (ABC) algorithm for energy-efficient clustering and routing. Initially, each node computes a fitness score based on residual energy and distance to the BS to determine its suitability as a CH. Only high-fitness nodes are considered candidates. The ABC algorithm then refines CH selection, with worker, onlooker, and scout bees exploring and introducing new candidates to avoid local optima. To reduce the transmission cost of distant CHs, a multi-hop relay mechanism is applied. Selected CHs are ordered by weight to form a hierarchical relay tree. Each CH broadcasts advertisements, allowing nearby nodes to join its cluster, and generates a Time Division Multiple Access (TDMA) schedule for organized transmissions. During operation, CHs aggregate data and forward it either to the BS or through relay CHs. This adaptive clustering and routing approach significantly delays the FND and extends overall network lifetime.

The Binary Dragonfly Algorithm (BDA)-based protocol [

34] operates in four phases: node localization, Dragonfly-based CH selection (optimizing residual energy and node density), fuzzy-logic cluster formation, and multi-hop path discovery for data transmission. This protocol extends network lifetime by balancing energy usage, though reliance on fuzzy logic and multi-hop forwarding through normal nodes can increase energy burden on some nodes, potentially affecting long-term performance.

A hybrid protocol combining K-means and ACO [

35] was also proposed. Initially, K-means forms clusters based on spatial proximity, after which ACO selects CHs and determines optimal routing paths. Decisions are guided by residual lifetime and energy efficiency (energy consumed in transmission). This hybridization exploits the strengths of K-means in forming compact clusters and ACO in optimizing routing. However, K-means alone is less effective in WSNs since it emphasizes Euclidean distance to centroids, overlooking irregular node distributions and resulting in imbalanced clusters and suboptimal energy usage. This demonstrates the necessity of integrating topology-aware mechanisms like our grid routing to enforce spatial balance, a weakness inherent in distance-only clustering.

Another hybrid approach combining K-means, PSO, and fuzzy logic [

36] was introduced. K-means first generates initial clusters, and its result is used as one particle in PSO, while the others are generated randomly. After optimization, the best particle defines the final clusters. CHs are then elected using fuzzy logic: Primary CHs are selected based on residual energy, distance to the BS, and distance to the centroid; Secondary CHs are chosen considering residual energy, distance to the centroid, and distance to the Primary CH. While this multi-layered selection improves clustering efficiency, executing fuzzy logic at every node increases computational overhead and accelerates energy depletion.

Furthermore, the efficacy of integrating learning-based optimization has been explored across various environments. For instance, in the challenging domain of Underwater Wireless Sensor Networks (UWSNs), recent work by Gang et al. introduced a Q-Learning-based approach to design an energy-efficient MAC protocol for collision avoidance [

37]. Their methodology leverages reinforcement learning to dynamically optimize channel access and transmission energy levels, aiming to maximize throughput and prolong network lifespan in environments characterized by high latency and low bandwidth. This work, while focusing on the MAC layer in UWSNs, underscores the growing trend of utilizing advanced optimization algorithms to address fundamental energy efficiency challenges across all forms of sensor networks.

Zheng et al. [

38] proposed a relay selection and deployment approach for non-orthogonal multiple-access (NOMA) enabled multi-AAV-assisted wireless sensor networks. Their study jointly optimizes relay placement and selection to enhance throughput and spectral efficiency under energy and coverage constraints, demonstrating the growing research interest in deployment-aware WSN optimization.

The preceding review highlights two dominant structural weaknesses in existing protocols. First, most metaheuristic approaches (e.g., AEOWSNC, AVOACS) either overlook or loosely couple energy metrics with CH selection, leading to concentrated energy depletion rather than balanced rotation. Second, while some adopt multi-hop routing (e.g., SHO-CH, EEM-LEACH-ABC), few integrate a scalable, topology-aware structure that actively enforces load balance across the network terrain. PUMA-GRID is explicitly designed to address this duality: the Puma Optimization Algorithm provides the adaptive, energy-aware exploration required for effective CH rotation, while the Grid-Based Multi-Hop Routing mechanism ensures that the topology is structured to minimize long-range transmission costs and prevent energy hotspots from forming. It is to resolve this dual challenge, the lack of energy aware search coupled with absent spatial load enforcement, that the PUMA-GRID framework was conceived and designed.

Table 1 summarizes the reviewed protocols in terms of CH selection methods, considered variables (residual energy, distance to BS, intra-cluster communication), and routing strategies. Overall, energy minimization in WSNs is achieved not only through metaheuristic-based CH selections, such as evolutionary and swarm-intelligence algorithms, but also via classical clustering, adaptive thresholding, and energy-aware multi-hop routing. These complementary approaches balance network load, prolong node lifetime, and reduce communication overhead, leading to more sustainable WSN deployments.

4. The PUMA-GRID Protocol: Clustering with Grid-Based Multi-Hop Routing

The proposed protocol, PUMA-GRID, introduces an advanced clustering and routing framework to address the critical challenge of energy efficiency in WSNs. It leverages the Puma Optimizer, a metaheuristic known for its adaptive balance between exploration and exploitation, to dynamically optimize CH selection across the network. By navigating the complex combinatorial space of possible CH assignments, PUMA explores diverse clustering configurations during the early search stages and gradually intensifies its focus on promising regions of the solution space. This adaptive tuning enables efficient convergence toward high-quality, energy-aware clustering solutions.

In this study, PUMA-GRID assumes a single BS located either inside or at the edge of the monitored area, which serves as the central data collection point. This assumption aligns with most benchmark WSN configurations and facilitates consistent performance comparison. Although deploying multiple BSs could further reduce communication distances and balance network load, the proposed framework was designed and evaluated under a single-BS scenario.

The technical contribution of PUMA-GRID lies in the coordinated mechanism that links the PUMA-based clustering outcome with the grid-based multi-hop routing behavior. Unlike approaches that use an optimizer solely for CH selection, PUMA-GRID embeds a fitness function specifically designed to favor CH patterns that align with the grid relay structure [

39]. After clustering, each CH participates in a structured A*-inspired relay decision that evaluates whether multi-hop forwarding offers a lower cost than direct transmission. This creates a closed-loop mechanism where clustering influences routing feasibility and routing efficiency feeds back into the selection pressure of the optimizer. This level of integration is not present in existing hybrid protocols, where clustering and routing typically operate as separate stages without mutual adaptation.

4.1. Initialization

In the initialization phase, the clustering process is prepared by setting up candidate solutions for CH selection. In the proposed protocol, the CH selection process is not predetermined within each grid cell but dynamically optimized through the PUMA algorithm. All sensor nodes are initially eligible to become CHs, and their selection depends on the fitness function that considers residual energy, distance to the BS, and intra-cluster communication distance.

After random deployment of nodes in the target area, each node transmits its position information to the BS, which then begins executing the PUMA algorithm. A population of individuals (candidate solutions) is generated, where each individual is represented as an -length binary vector. In this encoding, a value of 1 denotes that the node is selected as a CH, while 0 indicates a regular sensor node. The desired number of CHs is specified as a user-defined percentage of the total nodes. This binary representation, consistent with classical metaheuristic clustering approaches, enables flexible exploration of CH configurations and establishes a solid foundation for the optimization process.

4.2. PUMA-Based Clustering and Fitness Evaluation

PUMA balances exploration and exploitation through adaptive control mechanisms embedded in its search dynamics. During the exploration phase, candidate solutions undergo wide, randomized position adjustments that preserve diversity and help the algorithm avoid premature convergence. As optimization progresses, PUMA transitions into the exploitation phase, where updates become more focused, favoring local improvements around the current best solution. The number of CHs is not strictly enforced during this process, allowing the search to flexibly explore a broader range of configurations. This hyper-heuristic switching mechanism, as demonstrated in recent applications of the Puma Optimizer, dynamically adjusts the exploration–exploitation ratio according to the optimization context, enabling progressive refinement of clustering results while avoiding local optima.

The fitness function in PUMA-GRID integrates three key metrics: (1) the total distance between each regular node and its nearest CH, (2) the distance from each CH to the BS, and (3) the residual energy of the selected CHs. These components are combined using weighted coefficients

,

, and

, all in the range [0–1].

Additionally, a penalty term is introduced to discourage solutions where the number of CHs deviates significantly from the desired count. This mechanism ensures a balance between flexibility in exploration and compliance with user-defined network constraints. The objective function is therefore formulated as follows:

where

is the Euclidean distance between node and its associated CH .

is the Euclidean distance between CH and the BS.

is the residual energy of CH .

is the penalty coefficient that penalizes any deviation from .

is the number of CHs in the current solution.

is the desired number of CHs.

It is important to clarify the presence of the negative sign preceding the residual energy term . The optimization objective of the PUMA algorithm is defined as a minimization problem, where the algorithm searches for the solution with the lowest cost. However, the network design goal is to maximize the total residual energy of the selected CHs to prolong network lifetime. By subtracting the energy term in the cost function, higher residual energy values result in a lower overall cost. This ensures that the optimization process favors energy-rich nodes for the CH role.

After evaluating all candidate solutions in the PUMA population using the objective function, the individual with the minimum cost value is chosen as the best solution. This puma represents the most energy-efficient clustering configuration for the current round, achieving the optimal trade-off among intra-cluster communication, CH-to-BS transmission, residual energy, and the cluster count penalty. In this context, a round refers to a complete operational cycle consisting of cluster formation, data sensing, aggregation by CHs, and data transmission to the BS. Algorithm 4 illustrates how PUMA operates in selecting CHs.

It is acknowledged that the components of the objective function possess significantly different magnitudes; specifically, the Euclidean distance terms typically range in the hundreds of meters, whereas the residual energy is a fractional value measured in Joules. While explicit normalization techniques (such as Min–Max scaling) are often employed to standardize these values, this study utilizes the weighted coefficients

to inherently address this disparity. Through the sensitivity analysis presented in

Section 5, it was observed that tuning these weights effectively acts as a scaling mechanism.

| Algorithm 4: Binary Puma Optimization Algorithm for WSN Clustering |

- 1:

Input: Number of sensors ; sensor positions ; residual energy; BS position ; maximum iterations ; weighted coefficients , , and - 2:

Output: Optimal binary vector of CHsor ; best fitness value - 3:

Initialize a population of pumas as binary vectors ( for CH, 0 for normal node) - 4:

Evaluate the fitness of each puma using a weighted combination of residual energy, distance to CH, and distance to BS (Equation (6)) - 5:

Identify the current global best () - 6:

For each iteration to do - 7:

For each puma do - 8:

Apply exploration phase: roaming and searching for locally optimal CH positions - 9:

Apply exploitation phase: refining CH selection using ambush/attack strategies - 10:

Apply Normalization (Equation (3)) and Binarization (Equation (4)) to update CH vector - 11:

End For - 12:

Evaluate fitness of all pumas - 13:

Update the Global Best () - 14:

End For - 15:

For each iteration to do - 16:

For each puma do - 17:

If > - 18:

Apply Exploration Phase - 19:

If new solution improves - 20:

Update - 21:

End If - 22:

Else - 23:

Apply Exploitation Phase - 24:

If new solution improves - 25:

Update - 26:

End If - 27:

End If - 28:

Apply Normalization (Equation (3)) and Binarization (Equation (4)) to update CH vector - 29:

End For - 30:

Evaluate fitness of all pumas - 31:

Update the global best () - 32:

Recompute and - 33:

End For - 34:

Return the global best as the optimal CH selection vector and its fitness value

|

By assigning appropriate values to , the algorithm implicitly balances the large magnitude of the distance with the smaller magnitude of the energy, ensuring that no single term dominates the fitness evaluation purely due to its unit of measurement. Preliminary tests indicated that this weighted-scaling approach achieved performance parity with explicit normalization methods while reducing computational complexity.

4.3. Grid-Based Multi-Hop Routing via A*-Inspired Logic

After clustering, PUMA-GRID proceeds with a grid-based routing phase that employs a heuristic path selection mechanism. The network field is divided into uniform grid cells of user-defined size, with each CH residing in a specific cell. When forwarding aggregated data, a CH selects its next-hop relay from an adjacent grid cell that lies closer to the BS. The forwarding rule employs a localized A* cost function (

). Specifically, a CH selects a relay that minimizes the sum of the distance to that relay (

) and the remaining distance to the BS (

). This differs from standard greedy geographic forwarding, which typically minimizes only the remaining distance (

), by penalizing relays that are far from the sender, thus optimizing the total path length hop-by-hop without requiring a global priority queue. This heuristic emulates intelligent path selection, progressively routing data through energy-efficient multi-hop corridors while avoiding unnecessary long-range transmissions.

Figure 1 illustrates how the next CH is elected, and the detailed mechanism is provided in Algorithm 5.

To guarantee loop-free routing, a strict geographical descent condition is enforced: a CH only considers candidate relays located in grid cells that are strictly closer to the BS than its own cell. Because the Euclidean distance to the destination is required to monotonically decrease with every hop, the routing path forms a directed acyclic graph, rendering routing loops geometrically impossible.

The optimal grid size was determined empirically by testing various configurations. For instance, testing grid dimensions of 20 m, 30 m, and 40 m yielded maximum network lifetimes of approximately 355 rounds, 367 rounds, and 367 rounds, respectively. Given that both 30 m and 40 m achieved peak stability, the 40 m size was selected for the comparative analysis. By choosing the larger dimension that maintains optimal performance, we effectively minimize the total number of grid cells and the associated routing search overhead compared to the 30 m configuration.

| Algorithm 5: Grid-Based CH Routing |

- 1:

Input: Set of , , grid structure - 2:

Output: Optimal multi-hop routing paths for data forwarding - 3:

For each clusterhead do - 4:

If and are in the same grid - 5:

Send data directly to - 6:

Else If BS is in a directly adjacent grid - 7:

Send data directly to - 8:

Else - 9:

Search adjacent grid(s) in the direction of the - 10:

If one or more exist in adjacent grids - 11:

Select , where belongs to all adjacent grids - 12:

Forward data to - 13:

Else - 14:

Extend search to next-level adjacent grids - 15:

If is found - 16:

Send data directly to - 17:

Else If one or more exist - 18:

Select , where belongs to all adjacent grids - 19:

Forward data to - 20:

End If - 21:

End If - 22:

End If - 23:

End For - 24:

Return final routing paths for all

|

4.4. Adaptive Operation and Steady-State Execution

Once the best individual (lowest-cost solution) is identified, PUMA-GRID organizes clusters by enabling CHs to broadcast advertisements. Ordinary nodes then join their nearest CH, and a time-division schedule is established. During the steady-state phase, regular nodes sense data and transmit it to their CH, which aggregates the data and forwards it through the grid-based multi-hop path toward the BS. Re-clustering is triggered when the residual energy of CHs falls below defined thresholds or when load imbalance occurs, thereby maintaining sustained energy-aware operation.

4.5. Complexity Analysis of PUMA-GRID

The computational complexity of the proposed PUMA-GRID protocol can be analyzed by considering its two main components: CH selection based on PO and grid-based multi-hop routing. In the clustering phase, PO operates over a population of pumas, each representing a possible CH configuration among sensor nodes. During each iteration, the algorithm evaluates the fitness of all individuals using the defined weighted objective function. This process involves computing intra-cluster distances, CH-to-base-station distances, and residual energies. The cost of evaluating one solution is , leading to an overall clustering complexity of , where denotes the number of iterations. This level of complexity is typical for metaheuristic-based clustering algorithms and remains acceptable for moderate network sizes due to the algorithm’s parallelizable structure and convergence efficiency.

In the routing phase, the grid-based multi-hop routing mechanism partitions the monitored area into grids, where each CH searches for the next-hop relay among adjacent grids. Assuming each grid contains a small constant number of CHs, the selection of the next-hop node for each CH requires a limited search over neighboring grids, resulting in a routing complexity of approximately for a single transmission round.

Consequently, the total computational complexity of PUMA-GRID per clustering round is dominated by the POA component and can be expressed as which scales linearly with the number of nodes and grids. The memory complexity is , as the algorithm stores the position vectors and fitness values for all candidate solutions.

4.6. Conceptual Comparison with Prior Approaches

To present clearly what PUMA-GRID contributes beyond earlier designs, this subsection provides a structured comparison between the proposed method and two reference approaches, namely PUMA-SH (PUMA single-hop) and AEO-GRID (AEO multi-hop, grid-based). A visual summary is provided in

Figure 2, which outlines the main operational stages of each method from the input information to the resulting routing and performance outcome. While this section outlines the architectural differences, the resulting quantitative performance gains—specifically regarding network lifetime, throughput, and coverage fairness—are rigorously evaluated and compared in

Section 5.5.

PUMA-SH performs CH selection using the Puma Optimizer and forms clusters based on proximity, but it forwards data directly from each CH to the base station in a single hop manner. As shown in

Figure 2, this results in long-distance transmissions and early energy depletion near the BS. In AEO GRID the clustering relies mainly on distance-based evaluation, which can create unbalanced CH placements. The grid structure improves routing by using small relay steps between virtual cells, but the clustering and routing operate as separate processes, which limits the overall coordination between them.

PUMA-GRID introduces a more consistent process by integrating optimization-based clustering with structured forwarding.

Figure 2 shows that the method begins with node information that includes position, residual energy, and the BS location. The Puma Optimizer then evaluates several factors together, including intra cluster compactness, the distance between each candidate CH and the BS, the remaining energy of nodes, and a penalty on excessive CH count. This produces a more balanced set of CH positions. Afterward, the same field is partitioned into uniform virtual cells that shape the forwarding pattern. Instead of transmitting directly to the BS, CHs select relay heads based on the cost of a two-step path that follows the grid layout. This creates a multi-hop flow that avoids long transmissions and distributes the forwarding burden across the network.

5. Simulation Setup, Results, and Discussion

In practical deployments, sensor nodes can estimate their geographical positions through various localization techniques depending on the application and cost constraints. Common approaches include Global Positioning System (GPS) modules for outdoor environments, or signal-based localization methods such as Received Signal Strength Indication (RSSI), Time of Arrival (ToA), and Time Difference of Arrival (TDoA). In cases where GPS is not feasible, anchor-based or centroid localization algorithms can be applied using a limited number of reference nodes with known coordinates. The position of the BS is typically predefined and broadcast once to all nodes during network initialization, enabling each node to store this information locally and use it for cluster formation and routing decisions.

The simulations were performed using MATLAB R2014b on a workstation equipped with an Intel Core i7 processor and 32 GB of RAM, running on a Windows 11 operating system.

In the simulation study, we employed the first-order radio model for energy consumption as presented in [

40]. In this model, a radio transmits an

-bit data packet to a receiver at distance

meters by dissipating an energy amount

. Similarly, a sensor node’s radio consumes

energy to receive an

-bit message.

The free-space channel (

) is applied when

, while the multi-path channel (

) is applied when

. Equation (7) expresses the energy required to transmit a packet of

-bit across a distance

.

where

is the energy needed to transfer a single bit over

meters, both ways. The threshold distance at which the amplification factors begin to shift is known as

:

For the receiver to receive a packet of

bits, energy

must be consumed as follows:

The simulations were conducted in MATLAB using a network model to evaluate sensor-node performance. To ensure statistical reliability and mitigate the impact of random network initialization, each simulation scenario was executed for more than 50 independent Monte Carlo trials, and the results presented in the subsequent figures represent the averaged performance metrics across these runs.

Energy consumption was analyzed both at the node level and across the entire network using a standard radio energy model. A set of

sensor nodes was randomly deployed within the monitored area, where they continuously gathered and exchanged data before transmitting it to the BS after aggregation by the CHs. The CHs forwarded the data either directly to the BS or through other CHs using multi-hop transmission.

Table 2 summarizes the simulation parameters and the different BS positions.

The simulation parameters listed in

Table 2 were selected based on widely adopted configurations in WSN studies to ensure fair comparison and reproducibility. The network size of

and node count of 100 provide a moderate-density scenario suitable for evaluating scalability. The percentage of CHs was fixed at 5%, as this value is commonly used in protocols such as LEACH and its variants to maintain an optimal balance between energy consumption and communication overhead. The initial energy (0.1 J) and packet size (500 bytes) follow standard benchmarks used in energy-efficient routing simulations. The energy model parameters (

,

, and

) correspond to the first-order radio model, while the threshold distance

differentiates free-space and multipath propagation regions. The grid size (10–40 m) range was tested to assess the effect of spatial partitioning on routing performance.

Before execution, all nodes are initialized with basic network information, including the total number of nodes, grid dimensions, and the position of the BS, which is broadcast once during setup. These parameters are required to compute distances and support clustering and routing operations. Although this study uses static weight values for the fitness function, the same framework can support adaptive weight adjustment, where weights are dynamically updated in real time according to network conditions such as average residual energy, node density, or communication cost.

5.1. Choosing the Optimal Weights for the Fitness Function

To improve the energy efficiency of the proposed PUMA-GRID protocol, a multi-objective fitness function was employed, combining three key factors with associated weights: the distance from sensor nodes to their respective CH , the distance from CHs to the BS , and the residual energy of the CH . An additional penalty term is applied to penalize deviations from . The penalty coefficient was set to based on a preliminary sensitivity analysis conducted to balance constraint satisfaction with search exploration. Experimental results indicated that values of significantly lower than 10 resulted in weak enforcement of the constraint, leading to solutions that optimized energy but failed to maintain the required cluster structure. Conversely, values significantly higher than 10 (e.g., ) dominated the fitness landscape, causing the algorithm to stagnate in local optima by suppressing the exploration of alternative configurations. The value was found to provide the necessary magnitude to penalize invalid solutions while allowing the PUMA algorithm to effectively minimize distance and energy consumption within the valid solution space.

To identify the most suitable weight combinations, extensive simulations were conducted under three BS deployment scenarios:

- (1)

Located at the center of the sensor field;

- (2)

Situated outside the network boundary.

Although a full factorial exploration would involve 36 weight combinations, only a representative subset is reported here to avoid redundancy, while all possible combinations were simulated and analyzed. Each configuration was evaluated using the following performance indicators:

- (1)

, , —the rounds when the first, half, and last nodes die, used to estimate network lifetime and stability;

- (2)

Live Nodes per Round—tracking the network’s vitality throughout the simulation;

- (3)

Number of Packets Sent to the BS—reflecting data delivery capability;

- (4)

Coverage Fairness Index (CFI)—defined as

which measures the fraction of grid cells containing at least one live node, where

indicates perfect spatial fairness and values near

reflect poor distribution; and

- (5)

Residual Energy per Round—quantifying the energy dissipated by the entire network in each round.

It is important to note that while standard coverage metrics often rely on the precise sensing radius and geometric intersections, this study evaluates fairness at the grid-cell level (CFI) to align with the proposed PUMA-GRID architecture. Since the routing and clustering mechanisms utilize the grid structure to distribute traffic load, the presence of at least one active node per cell serves as a direct indicator of the protocol’s ability to maintain spatial connectivity and operational capability across the entire monitored region. Furthermore, this discrete approach effectively captures the formation of coverage holes caused by uneven energy depletion, serving as a proxy for spatial fairness without the high computational complexity of continuous coverage calculation.

5.2. Impact of Weight Combinations on Different Metrics (BS Inside the Network)

Figure 3 illustrates the FND, HND, and LND of the same network under different weight combinations when the BS is located inside the network. A higher value of

directs the optimization process to prioritize assigning nodes to nearby CHs. This reduces transmission energy, balances load distribution, and delays the FND, thereby prolonging the initial operational phase of the network. In contrast, a low

neglects proximity, forcing some nodes to transmit over longer distances, consume more energy, and die earlier.

The influence of on FND, HND, and LND is relatively minor when the BS is located at the center of the network. Since the CH-to-BS distance remains short across all configurations, variations in do not significantly affect energy consumption or network lifetime. Thus, minimizing CH-to-BS distance is less critical in this deployment scenario.

A lower , which reduces emphasis on CH residual energy, generally results in a longer LND. This is because CH selection becomes more diversified and less biased toward high-energy nodes, enabling more nodes to remain active over time. Conversely, a high favors repeated selection of energy-rich nodes, which may initially appear beneficial but eventually accelerates their depletion due to overuse, thereby reducing LND.

When and differ significantly, even a high can still produce an extended LND. This demonstrates that the interaction among weights plays a decisive role, and certain imbalanced combinations can nevertheless enhance overall energy efficiency.

Figure 4 shows the number of packets sent to the BS under different weight combinations when the BS is located inside the network. The analysis reveals that the choice of weights

has a significant effect on the volume of data successfully delivered. A higher value of

substantially increases the number of packets, emphasizing the importance of prioritizing intra-cluster distance in CH selection. This improves local communication efficiency and ensures more reliable data forwarding.

In contrast, lower values of are associated with higher packet counts. This indicates that giving excessive weight to the distance between CHs and the BS can reduce throughput, particularly when the BS is located within the network where CH-to-BS distances are already short. Thus, minimizing the emphasis on in such scenarios helps preserve higher packet delivery rates.

The role of is also evident: lower values, which reduce the influence of residual energy in CH selection, tend to yield more packets. This outcome suggests that excessive reliance on energy-rich nodes can lead to their overuse, while a moderate level of randomness or fairness in CH rotation distributes the forwarding load more evenly and supports sustained throughput.

Figure 5 illustrates the effect of different weight combinations on three performance metrics when the BS is located inside the network: (a) number of live nodes, (b) residual energy, and (c) the CFI.

A higher value of generally extends the number of live nodes and preserves residual energy for longer rounds. This is because prioritizing the distance between nodes and their CHs reduces transmission costs, balances energy consumption across nodes, and delays early depletion. Consequently, higher values also correlate with improved coverage fairness, as nodes remain distributed and active for longer. In contrast, a lower accelerates node death and energy dissipation due to longer communication distances, which results in uneven coverage and reduced fairness over time.

The effect of is comparatively limited in this scenario since the BS is centrally located, and CH-to-BS distances are already short across all configurations. As a result, increasing does not significantly alter node survival, energy consumption, or fairness. Nonetheless, excessive emphasis on can slightly reduce throughput and energy efficiency by constraining CH selection unnecessarily.

For , the results show that a moderate value contributes to more balanced performance across all three metrics. A lower , which reduces emphasis on CH residual energy, helps sustain node activity and fairness by diversifying CH selection, but it can accelerate overall energy depletion. Conversely, a very high heavily biases the convergence behavior, causing the optimizer to aggressively lock onto energy-rich nodes regardless of their position. This may appear beneficial initially but leads to concentrated energy usage, faster depletion of those nodes, and lower fairness.

5.3. Impact of Weight Combinations on Different Metrics (BS Outside the Network)

Figure 6 presents the effect of different weight combinations on FND, HND, and LND when the BS is located outside the network. The results highlight that the placement of the BS substantially changes how the weights influence network lifetime.

A higher value of continues to delay FND by emphasizing proximity between nodes and their CHs. This reduces intra-cluster energy costs and prevents early depletion of distant nodes. However, the improvement in HND and LND is less pronounced compared with the BS-inside scenario, since a larger proportion of energy is consumed in long-range CH-to-BS transmissions, regardless of efficient clustering.

The role of becomes more significant when the BS is external. Higher values extend both HND and LND, as prioritizing shorter CH-to-BS distances helps reduce the energy cost of long-range transmissions. In contrast, very low values degrade overall performance because CHs are sometimes selected without regard for their distance to the BS, leading to higher energy consumption and earlier node death.

The influence of remains consistent with earlier findings: moderate values provide balanced performance, while very high values lead to repeated use of energy-rich nodes, causing faster depletion and reduced LND. Conversely, very low improves fairness in CH rotation but may accelerate energy consumption across the network.

Figure 7 presents the effect of different weight combinations on the number of packets delivered to the BS when the BS is located outside the network. The results show that the role of weights shifts compared with the BS-inside scenario, reflecting the higher energy cost of long-range CH-to-BS communication.

A higher value of significantly improves packet delivery, as prioritizing intra-cluster distance reduces energy consumption during local transmissions and leaves more residual energy available for forwarding data to the distant BS. This effect is particularly evident for combinations where dominates, leading to the highest packet counts.

The influence of becomes more pronounced with the BS outside the network. Lower values of often correspond to higher packet counts, indicating that assigning excessive weight to CH-to-BS distance can restrict CH selection without substantially reducing long-range transmission costs. Conversely, when is kept moderate, it contributes positively by preventing inefficient CH placements.

The effect of is more nuanced. Lower to moderate values support higher packet delivery rates by diversifying CH selection and preventing the repeated overuse of energy-rich nodes. In contrast, very high values limit CH rotation, concentrating energy demands on a few nodes and reducing the overall number of packets delivered.

Figure 8 shows the effect of different weight combinations on (a) the number of live nodes, (b) residual energy, and (c) the CFI when the BS is located outside the network. The results emphasize how weight selection affects network longevity and energy balance under the more demanding external BS setting.

A higher value of

supports longer node survival by prioritizing intra-cluster proximity. As seen in

Figure 8a, configurations with high maintain a greater number of live nodes over time, which translates into slower residual energy depletion in

Figure 8b. In contrast, lower

values accelerate node deaths due to increased transmission distances, leading to earlier energy exhaustion and a faster decline in fairness.

The role of

is more critical when the BS is external. Configurations with moderate to high

exhibit extended residual energy and a slower decline in live nodes, as prioritizing CH-to-BS distance mitigates the cost of long-range transmissions.

Figure 8c confirms this, where higher

values sustain higher CFI levels for longer periods, ensuring more balanced spatial coverage.

The influence of is evident in fairness outcomes. Moderate values help diversify CH selection and balance the workload, contributing to extended CFI stability. However, very high risks over-relying on energy-rich nodes, which may initially improve residual energy but ultimately accelerate fairness degradation as these nodes deplete more quickly.

5.4. Discussion

The analysis of weight combinations under both deployment scenarios—BS inside and BS outside the network—provides important insights into the role of , , and in optimizing network lifetime, energy efficiency, and fairness.

When the BS is located inside the network, a higher emphasis on consistently improves performance across most metrics. Prioritizing intra-cluster distance minimizes transmission costs, delays FND, and sustains a larger number of live nodes, ultimately extending LND. In this scenario, the effect of is minimal, as the distance between CHs and the BS is already short and does not significantly impact energy consumption or throughput. Meanwhile, moderate values of prove beneficial by balancing the reuse of high-energy nodes with fairness in CH rotation, thereby supporting longer coverage and stable CFI.

In contrast, when the BS is outside the network, the influence of becomes critical. Long-range CH-to-BS transmissions dominate energy consumption and assigning higher weight to helps select CHs closer to the BS, reducing transmission costs and improving HND, LND, and residual energy utilization. While remains important for sustaining intra-cluster efficiency and supporting high packet delivery, its relative dominance is reduced compared with the BS-inside case. As before, moderate values of yield more balanced performance by preventing overuse of energy-rich nodes and maintaining fairness in coverage.

Across both scenarios, packet delivery results confirm that the highest throughput is achieved when is high, is kept low to moderate, and remains moderate. However, fairness metrics such as CFI suggest that purely maximizing throughput may compromise spatial coverage unless residual energy is also considered. Thus, configurations with overly low improve packet counts but reduce coverage balance over time, while excessively high shorten LND by exhausting selected nodes prematurely.

Synthesizing these findings, the best overall weight configuration emerges as a combination where is high (0.5–0.7), is low to moderate (0.1–0.3 when the BS is inside, and 0.2–0.4 when the BS is outside), and is moderate (0.2–0.3). This setup ensures efficient intra-cluster communication, controlled CH-to-BS distance, and fair utilization of residual energy, resulting in extended network lifetime, sustained packet delivery, and improved coverage fairness across both deployment scenarios.

5.5. Comparison of Different Routing Protocols

To assess the effectiveness of the proposed PUMA-GRID protocol, we conducted a comprehensive performance evaluation against several benchmark clustering and routing schemes. The comparison included LEACH, MR-LEACH, AEO-SH, and PUMA-SH (AEO and PUMA single-hop variants), as well as AEO-GRID and PUMA-GRID (AEO and PUMA multi-hop, grid-based approaches). The comparison considered a range of performance metrics that collectively capture both network longevity and efficiency: the stability period expressed through the rounds of first, half, and last node deaths; the total number of packets successfully delivered to the BS; the evolution of live nodes over time; the residual energy trends; the overhead in terms of control packets exchanged; and the coverage fairness index, which reflects the spatial distribution of active nodes. Simulations were conducted under two deployment scenarios, with the BS placed either inside or outside the sensor field, to assess protocol behavior under varying communication constraints.

For the simulation parameters (

Table 3), we extended the network to

, and increased the initial energy of each node to 0.5 joules. In addition, parameters values are set for grid size,

,

, and

. To ensure a rigorous and fair comparison, the following operational conditions were strictly enforced across all simulated protocols. All protocols operate under an identical round structure, defined as a setup phase followed by a steady-state phase. Re-clustering and CH rotation are executed at the beginning of every round for all protocols. This ensures that the energy overhead associated with the setup phase is incurred equally by all schemes, preventing any protocol from gaining an unfair advantage by skipping setup rounds. In LEACH and MR-LEACH, the number of CHs is probabilistic and fluctuates naturally around the target percentage (

) based on the stochastic threshold equation. In PUMA and AEO, the number of CHs is adaptive, determined by the metaheuristic optimization process in each round. However, the fitness function includes a penalty term to guide the solution toward the target percentage (

), ensuring the topology remains comparable to the baselines.

In

Figure 9a, where the BS is located inside the network, LEACH and MR-LEACH show the weakest results. Both suffer from extremely early FND and a rapid progression to HND, which indicates highly unbalanced energy consumption. Their LND values are also much shorter than those achieved by optimization-based methods, confirming that their probabilistic CH selection does not provide adequate energy distribution, even under the relatively favorable condition of a centrally placed BS.

The AEO-based protocols offer a noticeable improvement over LEACH and MR-LEACH, extending the HND and LND considerably. Between the two, AEO-GRID performs slightly better, benefiting from its structured multi-hop forwarding, which helps to alleviate the energy burden of long transmissions. Nevertheless, both variants still experience relatively early FND compared with PUMA-based methods, limiting their stability phase in the initial part of the network’s lifetime.

PUMA-SH and PUMA-GRID achieve the best overall performance in the BS-inside scenario. PUMA-SH delays FND significantly while maintaining a strong stability period, and PUMA-GRID further extends LND, achieving the longest lifetime among all protocols. This outcome demonstrates the benefit of combining PUMA’s adaptive clustering with grid-based routing, which balances traffic loads and prevents energy hotspots. As a result, PUMA-GRID delivers the most balanced and long-lasting operation when the BS is positioned inside the sensor field.

In

Figure 9b, where the BS is located outside the monitored area, the performance trends change noticeably. LEACH and MR-LEACH degrade further, with extremely short lifetimes and minimal stability. Nodes in these protocols consume excessive energy when transmitting to the distant BS, leading to very early network collapse.

Interestingly, under this more challenging deployment, the AEO-based protocols outperform all others. AEO-SH and particularly AEO-GRID achieve the longest HND and LND, clearly showing their strength in distributing energy fairly when longer communication distances are involved. The fitness-driven clustering of AEO, combined with grid-based routing, enables the network to adapt effectively to the harsher conditions, sustaining activity longer than both PUMA-based and classical approaches.

The PUMA protocols still maintain competitive results, especially in terms of delaying FND, but their lifetimes are shorter than those of the AEO-based methods in this scenario. PUMA-SH provides moderate stability, while PUMA-GRID achieves a balanced performance but cannot match the endurance of AEO-GRID. This indicates that while PUMA excels under central BS placement, AEO is better suited for external BS deployments, where its clustering and routing strategies better handle the additional communication overhead.

In

Figure 10a, where the BS is located inside the network, LEACH and MR LEACH achieve the lowest packet delivery, reflecting their limitations in balancing energy and sustaining communication. The probabilistic CH election of LEACH and the multi-hop variation in MR LEACH result in nodes depleting their energy too early, which reduces the overall throughput. AEO-SH and AEO-GRID perform better, with noticeable gains in packet delivery compared to LEACH, but their performance remains moderate and unable to match the more advanced designs. In contrast, the PUMA-based approaches clearly dominate. Both PUMA-SH and PUMA-GRID deliver more than twice the number of packets compared to AEO and LEACH, with PUMA-GRID producing the highest values among all protocols. This emphasizes the advantage of combining PUMA’s adaptive CH election with grid-based multi-hop routing, which reduces energy consumption and ensures more balanced utilization of resources.

In

Figure 10b, when the BS is placed outside the network, packet delivery declines across all protocols because of the higher transmission energy required for long distance communication. LEACH and MR-LEACH remain the weakest performers, again highlighting their inability to adapt to challenging deployment conditions. AEO-SH and AEO-GRID manage to sustain a moderate level of throughput, but their improvement is still limited. The PUMA-based protocols once again provide the best results, with PUMA-GRID achieving the highest number of packets followed closely by PUMA-SH. This consistent superiority across both scenarios highlights the robustness of the PUMA design, which successfully integrates residual energy awareness, node proximity, and efficient data forwarding mechanisms to maintain reliable communication even under more demanding conditions.

In

Figure 11a, which shows the results with the BS located inside the network, the LEACH and MR-LEACH protocols exhibit very short lifetimes, with both the first and last nodes dying much earlier than in other protocols. This outcome is consistent with their limited energy-awareness and reliance on probabilistic CH selection. In contrast, the AEO protocols (both single hop and grid-based) extend the network lifetime considerably, with the last node surviving much longer than in LEACH and MR-LEACH. However, while AEO demonstrates strong stability and balanced performance, the PUMA-based protocols, particularly PUMA-GRID, show the best performance overall. PUMA-GRID maintains live nodes for the longest duration, indicating that the combination of adaptive CH selection and grid-based routing significantly reduces energy imbalance and delays node deaths. PUMA-SH also performs strongly, maintaining a higher number of live nodes than AEO protocols, though it falls slightly behind PUMA-GRID in sustaining the final rounds of operation.

In

Figure 11b, when the BS is positioned outside the network, the performance differences between protocols become more pronounced. LEACH and MR-LEACH again show the shortest lifetime, confirming their inability to cope with the higher communication burden imposed by longer distances to the BS. AEO-SH and AEO-GRID perform considerably better, demonstrating resilience in maintaining active nodes for a longer time compared to LEACH. However, the PUMA protocols remain superior under this scenario. PUMA-SH shows the longest stability period, maintaining the largest number of live nodes until the later rounds, while PUMA-GRID also achieves a significantly extended lifetime compared to AEO. These results confirm that PUMA’s optimization-driven CH election, combined with efficient routing, ensures more balanced energy consumption, making it the most effective approach for sustaining network operations regardless of the BS placement.

In

Figure 12a, where the BS is located inside the network, the residual energy trends highlight clear differences between the protocols. LEACH and MR-LEACH deplete their energy rapidly, confirming their limited capacity to distribute communication loads evenly across the network. Both protocols reach near-zero energy in significantly fewer rounds, reflecting their vulnerability to hotspot issues and lack of energy-aware clustering. In contrast, AEO-SH and AEO-GRID extend energy sustainability further, with nodes maintaining moderate reserves across more rounds. This outcome is consistent with their energy-oriented cluster formation, which postpones full depletion. However, the best performance is observed in PUMA-based protocols, especially PUMA-GRID and PUMA-SH, which conserve energy most effectively. The balanced incorporation of residual energy, intra-cluster distance, and grid-based routing mechanisms enables slower depletion, maintaining higher energy levels through later rounds. This indicates that PUMA’s design succeeds in spreading energy consumption evenly while preventing premature exhaustion of CHs.

When the BS is placed outside the network, as shown in

Figure 12b, the disparities become more pronounced. LEACH and MR-LEACH remain the weakest performers, exhausting energy reserves very early, which underscores their inability to handle the longer transmission distances imposed by external BS placement. AEO-SH and AEO-GRID perform better, especially AEO-GRID, which manages to conserve energy longer due to its grid-based structure. Nonetheless, PUMA again demonstrates superior performance. PUMA-GRID shows the most stable and gradual decline in residual energy, with PUMA-SH following closely. These results reveal that PUMA’s adaptive strategies are resilient under harsher transmission conditions, ensuring that energy dissipation is minimized and reserves last significantly longer than in competing protocols.

In

Figure 13, the number of control packets highlights the overhead introduced by each routing protocol. LEACH consistently shows the lowest control overhead in both scenarios, with BS inside and outside the network, since it relies on simple probabilistic clustering without frequent energy-aware adjustments or sophisticated routing mechanisms. MR-LEACH increases the overhead slightly due to its multi-hop extension, which requires additional control messaging for route setup.

In contrast, the PUMA-based protocols generate a considerably higher number of control packets compared to LEACH and MR-LEACH. This overhead stems from the energy-aware CH selection and adaptive routing strategies that require additional coordination between nodes. While this increases control packet exchange, it directly contributes to improved energy balance and longer network lifetime, as observed in earlier figures. Between the two, PUMA-GRID typically introduces slightly more overhead than PUMA-SH, owing to the additional routing logic used in grid-based forwarding.

The AEO-based protocols exhibit the highest overhead across both scenarios. Their complex optimization-driven clustering demands intensive control messaging to exchange node state information and maintain optimal configurations. This ensures strong energy distribution but comes at the cost of higher overhead. Notably, AEO-GRID further increases the number of control packets compared to AEO-SH, reflecting the added cost of maintaining grid-based routing paths.

In

Figure 14a, with the BS placed inside the network, PUMA-GRID consistently outperforms AEO-GRID in maintaining higher coverage fairness over longer periods. At high CFI thresholds such as eighty and sixty percent, PUMA-GRID achieves a larger number of rounds before the fairness level drops, demonstrating its ability to sustain widespread spatial coverage across the grid. As the fairness requirement becomes less strict, both protocols extend their network lifetimes, yet PUMA-GRID maintains a steady advantage, confirming its strength in balancing energy consumption while ensuring even node distribution.

In

Figure 14b, where the BS is located outside the monitored area, the trend is reversed. AEO-GRID shows better resilience in sustaining higher CFI levels for longer rounds compared to PUMA-GRID. This is particularly evident at stricter thresholds such as eighty and sixty percent, where AEO-GRID achieves later last-round values. At lower fairness thresholds, such as twenty and ten percent, AEO-GRID still maintains its advantage, highlighting its efficiency in scenarios where longer-distance transmissions dominate.

5.6. General Discussion

The comparative analysis across

Figure 9,

Figure 10,

Figure 11,

Figure 12,

Figure 13 and

Figure 14 highlights not only which protocols perform better but also why these differences emerge, offering deeper insights into energy-aware routing for wireless sensor networks. The results confirm that network lifetime extension depends strongly on how effectively protocols balance energy among nodes. LEACH and MR-LEACH, with their probabilistic or static CH assignments, suffer from severe imbalance: some nodes deplete energy very early, leading to short stability periods. By contrast, optimization-based protocols such as PUMA and AEO explicitly consider residual energy and distances in their objective functions, which directly improves stability. PUMA-GRID achieves superior performance because it combines the adaptive exploration–exploitation mechanism of the Puma Optimizer with grid-based multi-hop routing. The optimizer dynamically refines CH selection to avoid premature node depletion, while the grid structure shortens transmission distances and balances inter-cluster loads. This synergy minimizes redundant transmissions, preserves residual energy, and maintains spatial coverage more effectively than LEACH, AEO-based, or earlier PUMA variants.

Throughput analysis provides further evidence of these differences. The number of packets delivered to the BS reflects both stability and how well a protocol manages congestion and redundancy. LEACH and MR-LEACH deliver very few packets because many nodes die early and surviving nodes face high transmission costs. AEO protocols improve throughput but remain limited by their sensitivity to initial CH assignments. PUMA protocols, especially PUMA-GRID, achieve the highest throughput in both scenarios, confirming that adaptive exploration–exploitation and efficient forwarding maximize sustained delivery. The improvement in PUMA-GRID is not only quantitative but also qualitative: by maintaining diverse CH distributions and structured forwarding paths, the network avoids congestion around central nodes, ensuring that throughput is steady rather than collapsing rapidly after a short period.

The live node and residual energy trends provide complementary insights. LEACH and MR-LEACH show sharp drops in both metrics, which reveals two main shortcomings: poor energy balancing and lack of residual energy consideration. AEO protocols distribute energy more effectively, reflected in smoother declines, but they still concentrate some load on selected CHs, leading to earlier depletion than PUMA. PUMA’s balance between exploration and exploitation ensures that CH roles rotate across different candidates, which distributes energy use more evenly and prevents premature exhaustion of high-energy nodes. Grid-based routing amplifies this effect by minimizing long direct transmissions, reducing the steep decline seen in other methods. These findings also show that the metric of residual energy alone can be misleading: although AEO maintains relatively high reserves at certain points, its coverage and fairness degrade earlier, indicating that spatial distribution of energy is as important as total reserves.

The analysis of control packet overhead reveals another trade-off. LEACH achieves low overhead but at the expense of stability and fairness, showing that minimal control traffic is not useful when it results in early collapse. AEO incurs the highest overhead because of frequent information exchange for clustering and routing optimization. PUMA strikes a middle ground, requiring more control packets than LEACH but significantly fewer than AEO, while still achieving superior lifetime and fairness. This necessary overhead is explicitly emphasized as an expected trade-off: the additional energy expenditure during the setup phase directly enables the protocol’s sustained energy savings and stability throughout the longer data transmission phase, thereby maximizing utility per control packet. PUMA achieves this by linking its overhead directly to measurable lifetime gains, while AEO sometimes introduces overhead that outweighs the benefits, particularly when the BS is inside the field.

Coverage fairness adds another dimension to the evaluation. A network that survives longer but collapses coverage in large regions may be unsuitable for applications such as environmental monitoring or surveillance. The Coverage Fairness Index results show that PUMA-GRID sustains higher fairness levels for longer when the BS is inside the network, reflecting its ability to spread CHs evenly and avoid clustering bias. Conversely, when the BS is outside, AEO-GRID maintains fairness for longer, indicating that its clustering strategy is more robust under asymmetric energy demands. This suggests that protocol suitability depends on deployment context and application requirements: for dense monitoring tasks where coverage uniformity is critical, PUMA is more effective with central BSs, whereas AEO is better suited for external placements where energy burdens are unevenly distributed.

Specifically addressing the performance disparity observed when the BS is outside the network, the strength of AEO-GRID lies in its simple, distance-focused fitness function. This function implicitly prioritizes the absolute minimization of the long-range CH-to-BS transmission cost, which is the single most dominant energy factor in the external BS setup. In contrast, PUMA-GRID’s multi-objective fitness function introduces a competitive constraint between minimizing geographical distance () and maximizing residual energy (). This trade-off, while crucial for fair energy balancing, leads PUMA to select geographically sub-optimal CHs, ultimately reducing its overall long-term network lifetime (LND) compared to AEO-GRID, which strictly minimizes the paramount geographical cost. This highlights that protocol superiority is context-dependent and subject to the weighting of primary optimization objectives.

Taken together, the findings show that PUMA-GRID provides the most consistent improvement across metrics when the BS is inside the network, combining high throughput, extended stability, balanced energy consumption, and strong fairness. When the BS is outside, AEO-GRID performs competitively and often surpasses PUMA in fairness and energy distribution, although PUMA remains stronger in throughput. LEACH and MR-LEACH remain consistently weak across all scenarios, underscoring the necessity of energy-aware and adaptive clustering strategies. The results highlight that effective protocol design requires not only extending lifetime but also balancing energy, maintaining fairness, and managing overhead, with the choice of protocol ultimately depending on the deployment environment and application objectives.

The strengths and design rationale of the evaluated protocols are summarized in

Table 4, synthesizing the trade-offs observed across multiple performance metrics.

5.7. Limitations

Although the proposed PUMA-GRID protocol achieves notable improvements in energy efficiency, stability, and coverage fairness compared with existing approaches, several limitations should be acknowledged.

First, the study was carried out in an idealized simulation environment where effects such as interference, packet loss, retransmissions, and signal fading were not modeled in detail. The use of the free space propagation model provided a simplified baseline for evaluating the optimization behavior of the algorithm, but it does not capture the full complexity of real wireless environments. Incorporating more realistic communication stacks and physical channel models will be an important step in future experimental work.

Second, the grid-based routing structure was designed mainly to complement the PUMA optimization mechanism rather than to serve as a new routing method. While the grid approach effectively reduces long distance transmissions and balances the load among CHs, it does not adapt dynamically to variations in node density, node failures, or irregular spatial distributions. Empty grid cells or uneven deployments can cause routing inefficiencies or temporary disconnections. However, the simplicity and scalability of the grid model make it appropriate for evaluating the energy optimization capability of PUMA-based clustering. Future studies will consider adaptive grid resizing and density aware routing mechanisms to improve resilience in heterogeneous network conditions.

Third, the proposed approach assumes that all nodes are static and identical in terms of initial energy and communication capacity. While the residual energy metric allows PUMA-GRID to handle energy decay adaptively, the assumption of identical initial energy may not hold in practice, nor does the static grid structure account for highly varied node density or irregular spatial deployments. Extending the protocol to support mobile and heterogeneous sensor nodes through adaptive mechanisms (such as node-specific weight tuning or adaptive grid resizing) would enhance its practical applicability.

Finally, the current configuration of weights in the fitness function is determined through simulation rather than through an adaptive real time process. Although this study identified effective weight combinations for different BS placements, these optimal values are inherently dependent on the specific network scale and density tested. A real time adaptation based on current network conditions such as remaining energy, node distribution, or data traffic could further enhance performance and reliability, especially when transitioning to networks with widely varying scale and density.