Substation Instrument Defect Detection Based on Multi-Domain Collaborative Attention Fusion

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Data-level Enhancement: We introduce a Mixup augmentation strategy to generate transitional defective samples, reducing data scarcity and enhancing the model’s robustness to defects with ambiguous boundaries [21].

- Architectural Innovation: We develop a Multi-Domain Collaborative Attention Fusion (MDCAF) module to improve the representation of fine-grained defects by synergistically capturing features across channel, spatial, and axial-relational domains.

- Training Optimization: We use a class-weight balancing strategy to help the model focus on low-frequency defect classes, reducing the impact of data imbalance.

2. An Improved Detection Algorithm Based on Multi-Domain Collaborative Attention Fusion

2.1. Enhancing Data Sample Diversity

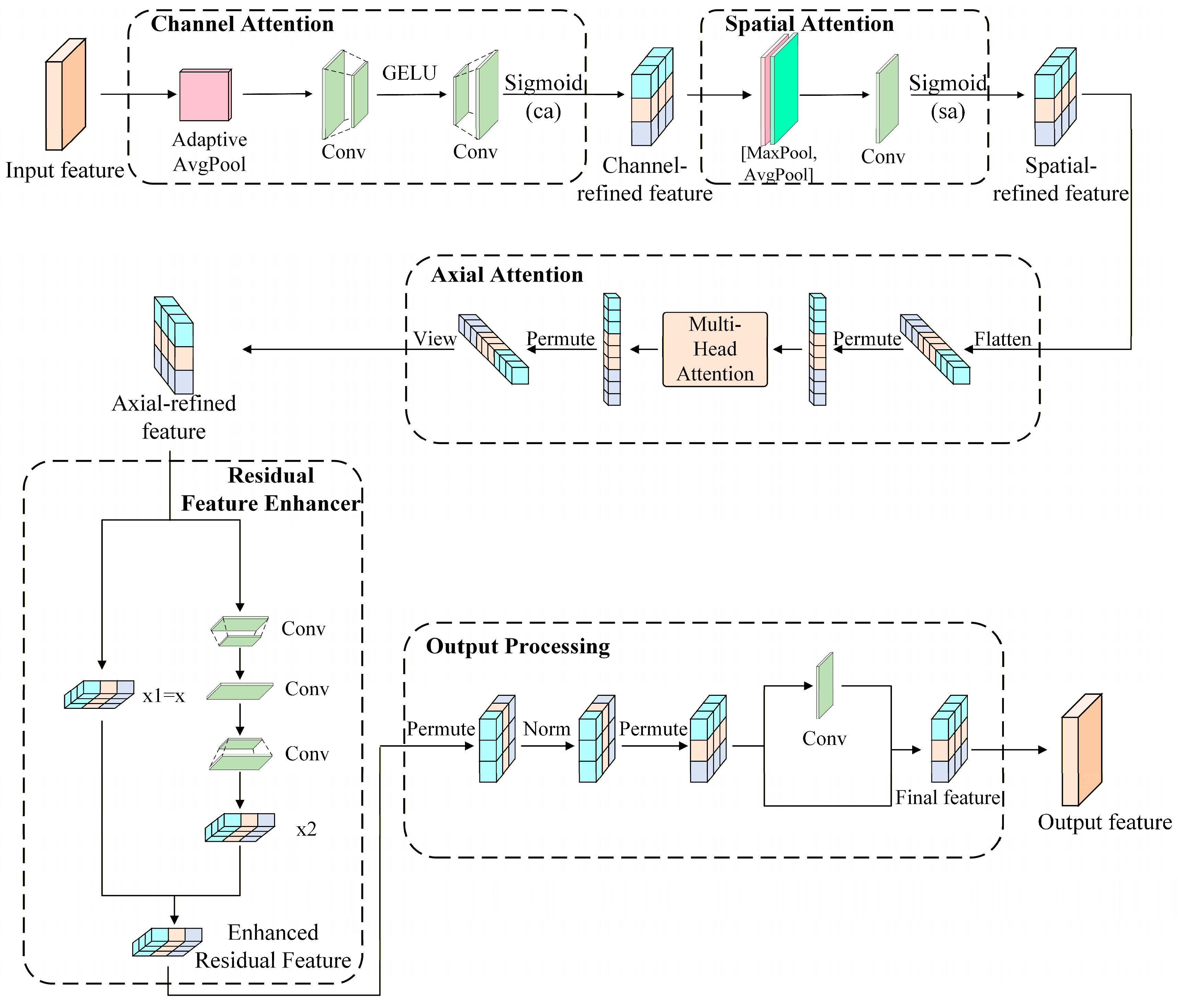

2.2. Multi-Domain Collaborative Attention Fusion Module

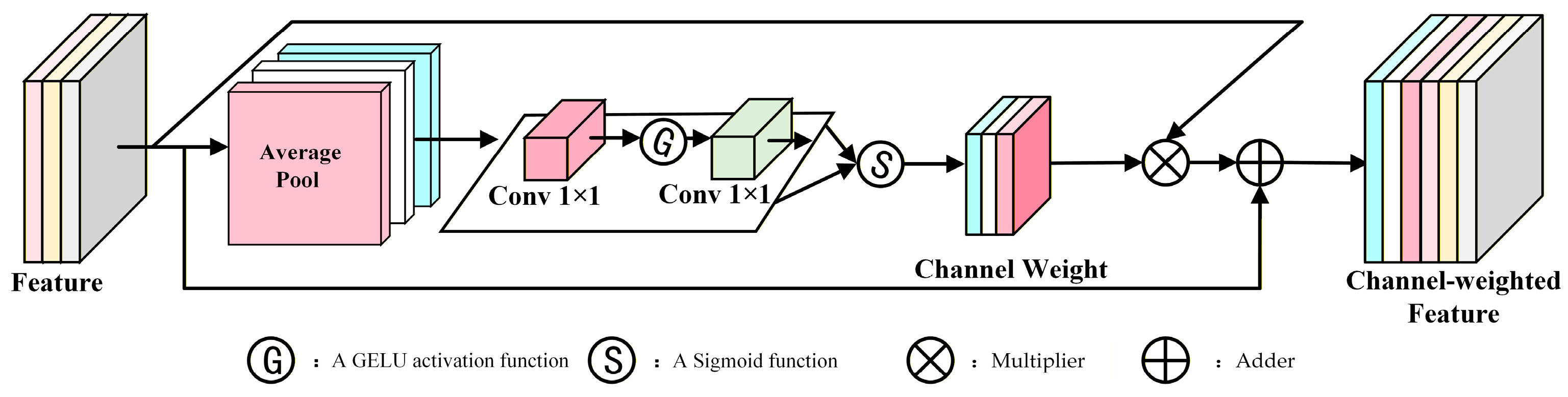

2.2.1. Channel-Domain Computation

- Spatial dimensions are compressed via global average pooling. This condenses spatial information into a channel-level global statistic, as defined in Equation (4):where represents the pixel value of the input feature map at the -th channel and spatial position .

- A 1 × 1 convolution with () channels reduces dimensionality to capture key inter-channel correlations efficiently. A GELU activation function follows this to model complex channel dependencies. Subsequently, A 1 × 1 convolution with channels is used to perform up-sampling, further strengthening the feature representation.

- A Sigmoid function maps the output to the [0, 1] interval to generate channel weights .where , .

- Finally, the input features are multiplied by the generated weights . This enhances channels containing defect signals while suppressing irrelevant background noise, resulting in the weighted features .where denotes channel-wise element-wise multiplication.

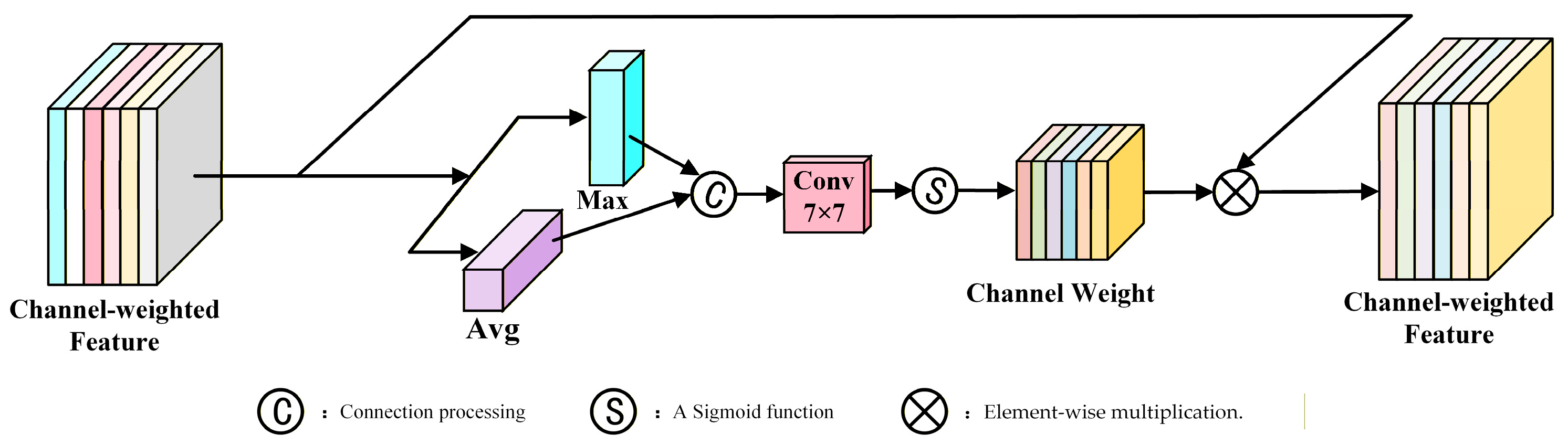

2.2.2. Spatial-Domain Computation

- The maximum and average values along the channel dimension of the channel-weighted features are extracted to capture both key regions and overall distribution traits. The calculations of and are shown in Equation (7):where max() and mean() represent the highest and average value across all spatial positions within each channel.

- Subsequently, and are concatenated and processed by a 7 × 7 convolutional layer. This operation leverages a large receptive field to integrate multi-scale spatial information and fuse features from different spatial statistics. A Sigmoid function then normalizes the output to [0, 1], generating spatial attention weights:

- Finally, the spatial weights are applied to the input features via element-wise multiplication. This highlights defect-relevant regions while suppressing secondary background noise, yielding the spatially weighted features :

2.2.3. Axial-Relation-Domain Computation

- To adapt the spatial-weighted features for the attention mechanism, is flattened into a sequential representation . The spatial dimensions are rearranged into a sequence-length dimension, ensuring that each spatial position corresponds to a sequence element. This preserves positional information while enabling the capture of long-range dependencies:

- The sequence is processed using multi-head attention with heads, where each head has a dimensionality of . This parallel design allows the model to learn diverse feature correlations across different subspaces jointly. The dimensionality is calculated as follows:

- For each head, three independent linear transformation matrices , , and reused to generate the Query (), Key () and Value () matrices, respectively. These are further divided into submatrices , , () for each attention head. Each attention head computes its output using Equation (12), where represents the similarity matrix among sequence positions. The Softmax function normalizes the similarity matrix, while the scaling factor mitigates the vanishing gradient problem associated with large inner products:

- Outputs from all attention heads are concatenated and linearly projected through to obtain the final multi-head attention representation, denoted as . The resulting output is reshaped back to its original spatial configuration, producing the axial feature representation , as expressed in Equations (13) and (14):

2.2.4. Residual Feature Enhancer

- A 1 × 1 convolutional kernel is used for channel down-sampling, reducing the input axial features’ channels to obtain .

- A 3 × 3 convolution is used for spatial feature extraction to derive . This step captures local spatial correlations and enhances structural details such as edges.

- A 1 × 1 convolutional up-samples the features resulting in , ensuring dimensions align with the original input.

- Finally, element-wise multiplication fuses the enhanced features with the original input . This interaction maintains the integrity of the original information while reinforcing it with the learned spatial details, as shown in Equations (15)–(18).

2.2.5. Stage Difference Regularization

2.2.6. Feature Alignment

- Let the original feature be denoted as . After a dimension permutation operation, the dimensions are rearranged into the order of batch , height , width , and channel , resulting in .

- Layer normalization is applied to each channel of every sample in the spatial dimensions . This reduces the internal covariate shift problem and enhances the stability and speed of model training, as shown in Equation (24):where is the mean of the feature along the spatial dimension, is the standard deviation, is the scaling factor used to adjust the amplitude of the feature distribution, and is the offset term.

- B Finally, a conditional branching strategy adapts the feature channels to match the downstream network’s requirement. Let be the current channel count and be the output from the RFE module. The final output is determined as follows:where is the output of the RFE, and is the result of applying batch normalization to .

2.3. Class Weight Balancing Strategy

- It is necessary to count the occurrences of each class in the training set to determine the class frequency , as shown in Equation (26).This frequency reflects the original distribution. For instance, in our dataset, “normal meter” samples far exceed “dial condensation” samples, resulting in a significant frequency disparity.

- To prioritize rare defects, the paper defines an inverse frequency weighting function . Lower frequency classes are assigned higher weights to amplify their contribution to the loss calculation:where is a small value (usually taken as ) to prevent division-by-zero errors.

- Since inverse weights vary significantly in scale, they are normalized. The weight for each class is divided by the sum of weights across all classes , ensuring the values lie within a stable range:

- The normalized weight is multiplied by to amplify the differences between classes, completing the class weight balancing calculation and obtaining the final balanced weight , as shown in Equation (29).

3. Experimental Results and Analysis

3.1. Experimental Environment

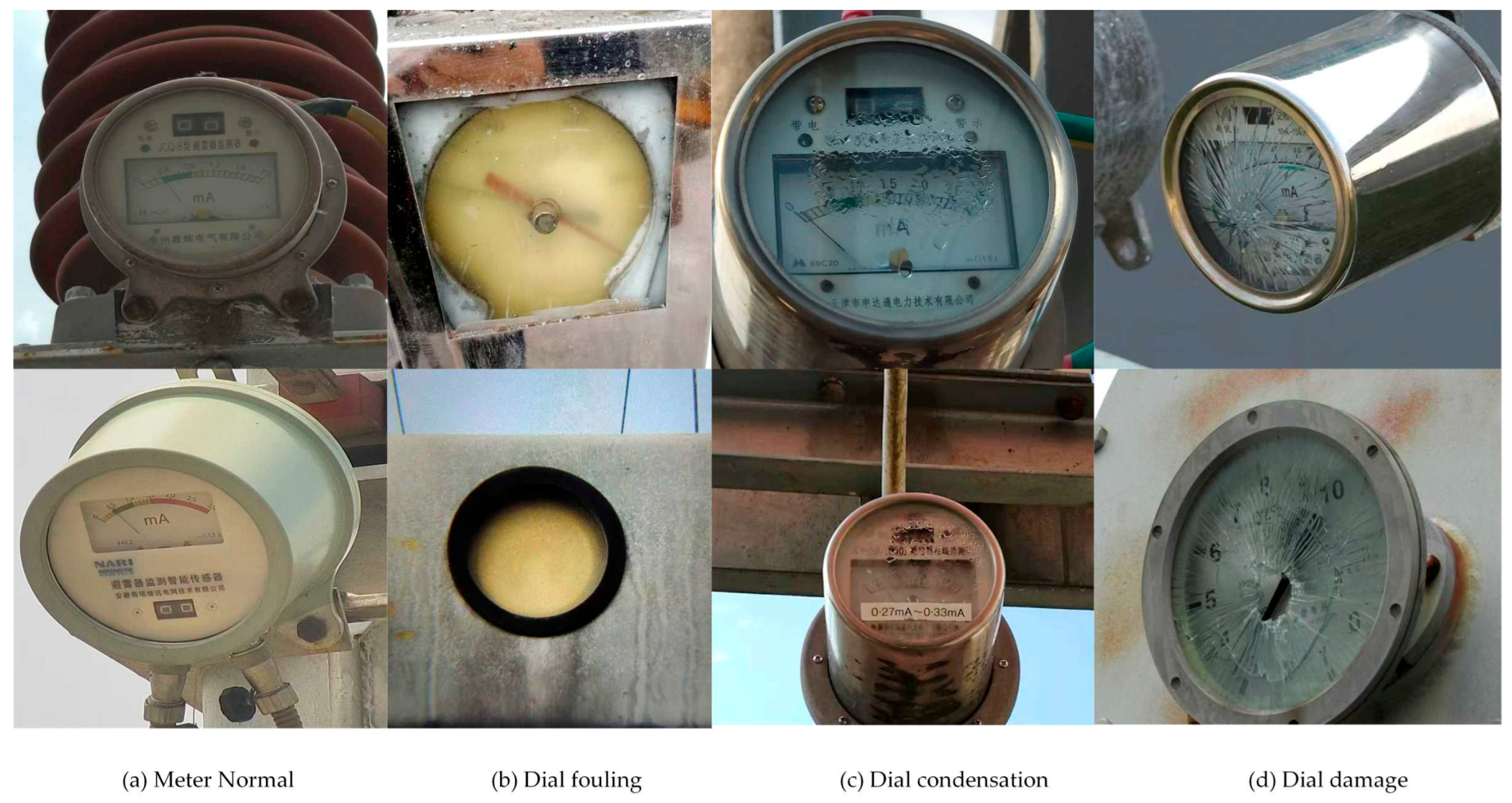

3.2. Experimental Dataset

3.3. Training Details

3.4. Evaluation Metrics

3.5. Detailed Analysis of Results

3.5.1. Comparative Experiment

3.5.2. Ablation Experiment of the MDCAF Module

- When introducing any single attention module alone, the overall improves to some extent compared to the baseline. Among them, the gain from axial attention is particularly noticeable, indicating that modeling long-range dependencies along the coordinate axes helps enhance the perception of the structural information of the instrument dial.

- Combining two attention modules (such as channel + space, channel + axial, space + axial) further improves the .

- Introducing all three attention modules at once boosts the overall by about 0.8 percentage points over the Baseline, highlighting the strong synergy between different attention mechanism dimensions.

3.5.3. Ablation Experiments of the Algorithm Proposed in This Paper

- Compared to the baseline model, adding data augmentation, the MDCAF module, and the class weight balancing strategy helps the network learn defect features more effectively, which improves the accuracy of substation instrument defect detection.

- When comparing the baseline model with the version that includes only the MDCAF module, the overall increased from 87.3% to 88.1%, a gain of 0.8 percentage points. The main performance boost was seen in the “dial fouling” class, where rose by 1.9 percentage points. The for the “dial damage” class remained pretty steady, while the “dial condensation” class showed a modest increase of 1.5 percentage points. This demonstrates the effectiveness of the MDCAF module, which improves the representation of complex defects by selectively emphasizing key features in the channel domain, spatially localizing defect regions, and modeling global continuity in the axial-relation domain. However, because the “dial condensation” class had only 186 samples, the attention mechanism alone could not fully compensate for the limited training data, resulting in only modest improvements in that category.

- After adding the Mixup data augmentation strategy on top of the MDCAF module, the for the “dial condensation” class increased significantly by 2.2 percentage points. In contrast, the for the “normal meter” class slightly decreased. Mixup creates transitional defect samples via weighted blending, thereby enhancing the diversity of low-frequency defects and helping the model learn complex morphologies more effectively. Conversely, since the “normal meter” class already had ample samples, excessive mixing diluted its distinctive patterns, resulting in a small decrease in . However, this minor decline had little impact on overall performance.

- Comparing different two-module combinations, the model that combined Mixup and the class weight balancing strategy showed the most remarkable improvement for the “dial fouling” class, increasing by 2.8 percentage points. In contrast, the for the “dial condensation” class remained essentially unchanged. This suggests that class-weight balancing, using inverse-frequency weighting, increased the significance of low-frequency defects in the loss calculation and helped reduce overfitting to normal samples. However, without the MDCAF module, the weak features of condensation were still not effectively captured, so the performance on this low-frequency class did not improve much.

- When all three components—Mixup, the MDCAF module, and the class weight balancing strategy—were used together, the overall increased by 2.8 percentage points compared to the baseline. The for the rare “dial condensation” class rose by 6.4 percentage points, the largest improvement among all categories. The for the “dial damage” and “dial fouling” classes increased by 1.8 and 3.6 percentage points, respectively, while the “normal meter” class saw only a slight decline. The Mixup strategy created transitional defect samples to compensate for limited feature diversity; the MDCAF module identified low-contrast features of condensation, damage edges, and the overall distribution of fouling via multi-domain attention; and the class weight balancing strategy dynamically focused on low-frequency categories. The combination of these three components led to significant improvements in substation instrument defect detection accuracy.

3.6. Visual Comparison of Results

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhang, J.; Zhu, W. Research on Algorithm for Improving Infrared Image Defect Segmentation of Power Equipment. Electronics 2023, 12, 1588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, M.; Qin, L.; Liu, K.; Deng, X.; Li, B.; Li, Q.; Xu, X. Research on Intelligent Detection Algorithms for Substation Power Meters. High Volt. Eng. 2024, 50, 2942–2954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, W.; Chen, H. Research on Intelligent Substation Monitoring by Image Recognition Method. Int. J. Emerg. Electr. Power Syst. 2021, 22, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, K.U.; Thakur, N.V. A Review and an Approach for Object Detection in Images. Int. J. Comput. Vis. Robot. 2017, 7, 196–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Dosovitskiy, A.; Beyer, L.; Kolesnikov, A.; Weissenborn, D.; Zhai, X.; Unterthiner, T.; Dehghani, M.; Minderer, M.; Heigold, G.; Gelly, S.; et al. An Image Is Worth 16x16 Words: Transformers for Image Recognition at Scale. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2010.11929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redmon, J.; Divvala, S.; Girshick, R.; Farhadi, A. You Only Look Once: Unified, Real-Time Object Detection; IEEE Computer Society: Washington, DC, USA, 2016; pp. 779–788. [Google Scholar]

- Varghese, R.; Sambath, M. YOLOv8: A Novel Object Detection Algorithm with Enhanced Performance and Robustness. In Proceedings of the 2024 International Conference on Advances in Data Engineering and Intelligent Computing Systems (ADICS), Chennai, India, 18–19 April 2024; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z.; Lin, Y.; Cao, Y.; Hu, H.; Wei, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Lin, S.; Guo, B. 7Swin Transformer: Hierarchical Vision Transformer Using Shifted Windows. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Montreal, QC, Canada, 10–17 October 2021; pp. 9992–10002. [Google Scholar]

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, Ł.; Polosukhin, I. Attention Is All You Need. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, Long Beach, CA, USA, 4–9 December 2017; Curran Associates, Inc.: Nice, France, 2017; Volume 30. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Z.; Ma, D.; Shi, Y.; Li, G. Appearance Defect Detection Algorithm for Substation Meters Based on Improved YOLOX. J. Graph. 2023, 44, 937–946. [Google Scholar]

- Gevorgyan, Z. SIoU Loss: More Powerful Learning for Bounding Box Regression. arXiv 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Fan, J.; Yan, F.; Hu, H.; Zeng, Z.; Huang, H. Unsupervised Fur Anomaly Detection with B-Spline Noise-Guided Multi-Directional Feature Aggregation. Vis. Comput. 2025, 41, 6169–6185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Xu, X.; Wang, Y.; Wu, P.; Yan, F.; Zeng, Z. A Robust Defect Detection Method for Syringe Scale without Positive Samples. Vis. Comput. 2023, 39, 5451–5467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hao, S.; Lee, D.-H.; Zhao, D. Sequence to Sequence Learning with Attention Mechanism for Short-Term Passenger Flow Prediction in Large-Scale Metro System. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2019, 107, 287–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Shen, L.; Sun, G. Squeeze-and-Excitation Networks. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–23 June 2018; pp. 7132–7141. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Wang, W.; Hu, X.; Yang, J. Selective Kernel Networks. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Long Beach, CA, USA, 15–20 June 2019; pp. 510–519. [Google Scholar]

- Bao, Q.; Liu, Y.; Gang, B.; Yang, W.; Liao, Q. SCTANet: A Spatial Attention-Guided CNN-Transformer Aggregation Network for Deep Face Image Super-Resolution. IEEE Trans. Multimed. 2023, 25, 8554–8565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woo, S.; Park, J.; Lee, J.-Y.; Kweon, I.S. CBAM: Convolutional Block Attention Module. In Proceedings of the Computer Vision—ECCV 2018, Munich, Germany, 8–14 September 2018; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 3–19. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Q.; Tan, K.; Yuan, D.; Liu, Q. Progressive Domain Adaptation for Thermal Infrared Tracking. Electronics 2025, 14, 162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Geng, G.; Zhang, X.; Yuan, D. Cross-Modal Alignment Enhancement for Vision–Language Tracking via Textual Heatmap Mapping. AI 2025, 6, 263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Cisse, M.; Dauphin, Y.N.; Lopez-Paz, D. Mixup: Beyond Empirical Risk Minimization. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1710.09412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Zhu, Y.; Green, B.; Adam, H.; Yuille, A.; Chen, L.-C. Axial-DeepLab: Stand-Alone Axial-Attention for Panoptic Segmentation. In Proceedings of the Computer Vision—ECCV 2020, Glasgow, UK, 23–28 August 2020; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 108–126. [Google Scholar]

- He, K.; Zhang, X.; Ren, S.; Sun, J. Deep Residual Learning for Image Recognition. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016; pp. 770–778. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Q.; Wang, Y.; Yang, T.; Zhang, X.; Cheng, J.; Sun, J. You Only Look One-Level Feature. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Nashville, TN, USA, 20–25 June 2021; pp. 13039–13048. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, S.; He, K.; Girshick, R.; Sun, J. Faster R-CNN: Towards Real-Time Object Detection with Region Proposal Networks. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2017, 39, 1137–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Name | Model |

|---|---|

| Operating System | Ubuntu16.04 |

| CPU | E5-2620v3 |

| GPU | TITAN Xp |

| CUDA | 10.1 |

| Python | 3.8 |

| Deep Learning Framework | Pytorch1.8.1 |

| Category Name | Number of Images | Label Name |

|---|---|---|

| Meter Normal | 845 | bj_zc |

| Dial fouling | 490 | bj_zw |

| Dial condensation | 186 | bj_nl |

| Dial damage | 272 | bj_bpps |

| Name | Configuration |

|---|---|

| optimizer | SGD |

| Initial learning rate | 0.01 |

| Learning rate strategy | Cosine annealing strategy |

| weight decay | 0.0005 |

| epochs | 200 |

| batch size | 16 |

| Image input size | 640 |

| Algorithms | (%) | (%) | FPS | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Meter Normal | Dial Condensation | Dial Damage | Dial Fouling | |||

| Faster R-CNN | 96.1 | 77.2 | 87.4 | 86.3 | 87.1 | 21.5 |

| YOLOv8 | 96.8 | 75.7 | 88.6 | 88.2 | 87.3 | 98.4 |

| YOLOF | 89.7 | 70.5 | 82.3 | 80.1 | 80.7 | 53.2 |

| The algorithm proposed in this paper | 95.9 | 82.1 | 90.4 | 91.8 | 90.1 | 81.6 |

| Baseline | Channel Attention | Spatial Attention | Axial Attention | (%) | (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Meter Normal | Dial Condensation | Dial Damage | Dial Fouling | |||||

| √ | - | - | - | 96.8 | 75.7 | 88.6 | 88.2 | 87.3 |

| √ | √ | - | - | 96.6 | 76.3 | 87.9 | 88.3 | 87.3 |

| √ | - | √ | - | 96.5 | 76.2 | 88.3 | 88.4 | 87.4 |

| √ | - | - | √ | 96.4 | 76.0 | 88.8 | 89.0 | 87.5 |

| √ | √ | √ | - | 96.7 | 76.7 | 88.5 | 89.5 | 87.7 |

| √ | √ | - | √ | 96.6 | 76.6 | 88.3 | 89.4 | 87.8 |

| √ | - | √ | √ | 96.5 | 76.2 | 88.7 | 89.3 | 87.6 |

| √ | √ | √ | √ | 96.6 | 77.2 | 88.1 | 90.1 | 88.1 |

| Data Augmentation | MDCAF Module | Class Weight Balancing Strategy | (%) | (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Meter Normal | Dial Condensation | Dial Damage | Dial Fouling | ||||

| - | - | - | 96.8 | 75.7 | 88.6 | 88.2 | 87.3 |

| - | √ | - | 96.6 | 77.2 | 88.1 | 90.1 | 88.1 |

| - | √ | √ | 94.6 | 73.2 | 90.0 | 90.7 | 87.1 |

| √ | √ | - | 94.5 | 79.4 | 85.8 | 90.3 | 87.5 |

| √ | - | √ | 95.8 | 75.6 | 89.8 | 91.0 | 88.1 |

| √ | √ | √ | 95.9 | 82.1 | 90.4 | 91.8 | 90.1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liu, K.; Li, Y.; Wang, S.; Yang, Z.; Li, Z.; Zhao, Z. Substation Instrument Defect Detection Based on Multi-Domain Collaborative Attention Fusion. Electronics 2025, 14, 4690. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14234690

Liu K, Li Y, Wang S, Yang Z, Li Z, Zhao Z. Substation Instrument Defect Detection Based on Multi-Domain Collaborative Attention Fusion. Electronics. 2025; 14(23):4690. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14234690

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Kequan, Yandong Li, Shiwei Wang, Zhaoguang Yang, Zhixin Li, and Zhenbing Zhao. 2025. "Substation Instrument Defect Detection Based on Multi-Domain Collaborative Attention Fusion" Electronics 14, no. 23: 4690. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14234690

APA StyleLiu, K., Li, Y., Wang, S., Yang, Z., Li, Z., & Zhao, Z. (2025). Substation Instrument Defect Detection Based on Multi-Domain Collaborative Attention Fusion. Electronics, 14(23), 4690. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14234690