1. Introduction

Financial markets process an ever-growing volume of textual information at high velocity. Beyond formal news, social streams contain economically meaningful signals [

1]. Headlines—brief but information-dense—shape investor attention and often encode macroeconomic narratives [

2], a conclusion supported by systematic reviews on text mining for market prediction [

3]. In this financial context, sentiment analysis systems must be not only accurate but also auditable for risk, compliance, and governance. Transformers—notably FinBERT—have set accuracy benchmarks for financial sentiment classification [

4]. Yet, opacity in model reasoning impedes adoption in high-stakes finance [

5]. Financial institutions increasingly require transparent, testable justifications for model outputs. This paper addresses that requirement by delivering a finance-centric workflow designed to: (i) achieve competitive accuracy on sector-specific financial headlines, (ii) audit explanations for faithfulness rather than plausibility alone, and (iii) quantify uncertainty to align predictions with risk management practices. Unlike general multi-domain XAI studies, we restrict our focus to sector-specific financial news and evaluate economic relevance via standard, investable sector ETFs (e.g., SPDR Select Sector funds) to ensure direct alignment with market practice [

6,

7,

8,

9]. This keeps the conceptual framing, datasets, and validation coherent within finance. We make four contributions beyond straightforward benchmarking: (1) Finance-aligned, sector-aware reproducibility with a fully open, script-driven pipeline that constructs a sector-tagged gold set (1500 headlines), trains/evaluates baselines and FinBERT variants, and outputs figures/tables aligned to GICS sectors and SPDR ETFs (SPDR site:

https://www.sectorspdrs.com/; MSCI GICS page:

https://www.msci.com/indexes/index-resources/gics, accessed on 20 July 2025). (2) Audited explainability for FinBERT via deletion curves and AOPC, contrasting IG, LIME, and attention-rollout and showing LIME > IG >> attention for faithfulness [

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16] (3) Uncertainty and calibration audit—reliability diagrams, ECE, and temperature scaling—following Guo et al. [

16] (4) Financial validation under a reactive-signal hypothesis via event studies and transaction-cost-adjusted sector backtests, focusing on downstream economic significance rather than forecasting [

17,

18]. The XAI toolkit used is standard and that the contribution is the reproducible, finance-aligned evaluation and deployment guidance.

2. Literature Review

The field of automated sentiment analysis in finance has undergone a significant evolution, progressing from static, rule-based systems to dynamic, data-driven deep learning models. Pioneering contributions centered on the development of domain-specific lexicons, with the Loughran–McDonald (LM) financial sentiment lexicon representing an important advancement [

19]. Through rigorous analysis of financial disclosures, it was demonstrated that general-purpose dictionaries were suboptimal for capturing the semantic nuances of financial discourse. The LM lexicon established that terms such as “liability” or “risk” exhibit significant semantic domain shift, carrying context-specific connotations distinct from their general usage. Subsequent lexicon-based tools, notably VADER, have incorporated syntactic heuristics to better interpret short texts by accounting for negation, intensifiers, and punctuation, though all such methods are inherently constrained by their inability to dynamically interpret context beyond predefined rules.

The advent of transformer architecture has marked a paradigm shift in the field, leading to new state-of-the-art performance benchmarks. Models such as FinBERT, a derivative of the BERT architecture pre-trained on a large-scale financial corpus, leverage self-attention mechanisms to capture complex and long-range semantic dependencies within text [

4]. Its architecture is adaptable, having been successfully fine-tuned for highly specialized documents such as Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) minutes [

20]. These models consistently outperform traditional machine learning methods by learning contextual representations directly from data. However, this superior predictive power is accompanied by considerable drawbacks, including significant computational exigencies and a fundamental lack of transparency. Functioning as opaque “black box” systems, their internal decision-making processes are not readily intelligible to human users.

2.1. Advances in Explainable AI (XAI)

This makes it exceedingly difficult to trace a given prediction back to specific textual evidence, presenting a fundamental challenge to model governance and accountability—a critical limitation in high-stakes applications like finance, where model justification is often a regulatory and operational necessity [

21].

In response to this challenge, Explainable AI (XAI) has emerged as a critical subfield focused on ameliorating the opacity of complex models. Among the most robust and theoretically grounded XAI frameworks is SHAP (SHapley Additive Explanations), introduced by Lundberg and Lee [

22]. Rooted in cooperative game theory and the concept of Shapley values, SHAP offers a unified method for attributing the output of any machine learning model to its input features. It computes the marginal contribution of each feature—in this context, a word or token—to a prediction, thereby providing both local (per-instance) and global (model-wide) interpretability. In contrast to earlier techniques like LIME [

23], which rely on local linear approximations that can lack stability, SHAP provides explanations that are guaranteed to be consistent and locally accurate, adhering to strong theoretical properties.

This research is situated at the confluence of these domains. While acknowledging the state-of-the-art performance of models like FinBERT, our work prioritizes the principles of XAI. We adopt a “glass box” methodology where possible, employing inherently interpretable model architectures and augmenting them with SHAP to produce granular and defensible explanations. Crucially, we also extend explainability techniques to “black box” models and introduce quantitative metrics to evaluate the faithfulness of these explanations. By systematically comparing this transparent pipeline against both lexicon-based methods and a state-of-the-art transformer, this study aims to provide a practical framework that reconciles the tension between raw predictive capability and the exigent need for interpretability in financial text analysis.

Explainable AI (XAI) methods are commonly organized along two axes: (i) intrinsically interpretable models whose structure is transparent by design and (ii) post hoc explanation methods that attempt to explain complex “black-box” predictors after training [

24]. Intrinsic approaches include sparse linear models, decision trees, scoring systems, and generalized additive models (GAMs), in which the prediction decomposes into a sum of low-dimensional functions of the inputs [

25]. Modern GAM variants such as the Explainable Boosting Machine (EBM) preserve additivity while learning flexible shape functions, enabling competitive accuracy with decomposable, human-auditable contributions [

26]. These models map naturally to our methodological choices, where EBM provides a non-linear but transparent baseline against which we compare transformer architectures.

Post hoc techniques constitute several families. Perturbation-based methods (e.g., LIME) approximate the local decision boundary with a simple surrogate to derive feature importances [

23]. Game-theoretic approaches such as SHAP attribute predictions to features using Shapley values, offering local and global explanations with desirable consistency properties [

22]. Gradient-based methods—including Integrated Gradients (IG)—propagate gradients from output to input along a path to yield token- or feature-level attributions that satisfy axioms like sensitivity and implementation invariance [

27]. For deep sequence models, attention-based explanations use attention weights or roll-ups (e.g., attention rollout) as importance scores, though their faithfulness remains debated in NLP. Beyond feature attribution, rule- or example-based explainers such as Anchors provide high-precision, human-readable rules for specific predictions, while concept-based methods (e.g., TCAV) quantify the influence of human-aligned concepts on predictions—useful when features are not directly human-meaningful. Together, these families span complementary desiderata (local/global scope, theoretical guarantees, stability, and human interpretability) that we exploit in our evaluations.

A growing body of recent work critically examines faithfulness—whether explanations truly reflect a model’s internal reasoning. Surveys in 2023–2025 synthesize metrics (e.g., deletion/insertion curves, comprehensiveness/sufficiency, AOPC variants) and highlight failure modes across attribution and attention methods, motivating quantitative audits rather than purely qualitative inspection [

10,

11]. Our study aligns with this direction by operationalizing a deletion-based perturbation test to compare IG, LIME, and attention explanations for FinBERT (

Section 4.2).

Recent surveys argue that explanation work in NLP should prioritize faithfulness—quantitatively testing whether attributions reflect true model reasoning—using deletion/insertion curves, comprehensiveness/sufficiency, and ROAR/AOPC, rather than relying on plausibility alone [

10,

11]. We operationalize this recommendation via deletion-based AOPC for FinBERT [

12,

28,

29].

2.2. XAI for Natural Language Processing

In NLP, explanation targets are typically tokens, spans (rationales), instances, or concepts. Token- and span-level attribution via gradients (e.g., IG) and perturbation (e.g., LIME) are prevalent because they interface naturally with discrete text. However, attribution stability and sensitivity to baselines, sampling noise, and masking strategies can hinder faithfulness if left unmeasured [

23,

27]. Recent surveys emphasize the importance of faithfulness-oriented evaluation (e.g., deletion/insertion, ROAR/AOPC, comprehensiveness/sufficiency) over plausibility-only measures, noting that attention weights and some perturbation strategies can produce persuasive but misleading highlights [

10,

11].

Beyond word-level importance, rule-based rationales (Anchors) and concept-based explanations (TCAV) address the semantic gap by mapping neural reasoning to human-interpretable conditions or higher-level concepts (e.g., “lawsuit,” “AI chips”), which is particularly relevant to domain narratives. While such methods are more common in vision, their recent adaptations to text underscore advantages for global interpretability and auditing spurious correlations (e.g., via concept sensitivity analyses). This motivates our sector-specific analysis, where we compare linguistic drivers across industries using SHAP and evaluate whether attributions align with domain concepts (

Section 4.3).

Finally, contemporary NLP work stresses explanation robustness under distribution shift and noisy supervision, both salient in news streams. Adversarial sensitivity tests show that small perturbations can drastically change explanation maps even when predictions do not, reinforcing the need for reliability checks [

30]. We address these concerns by coupling faithfulness tests with a weak-supervision audit, quantifying how noisy labels distort both performance and explanations (

Section 5.3).

2.3. Explainability in Financial News Sentiment Analysis

Financial text tasks pose unique constraints—regulatory auditability, risk management, and market impact—that amplify the value of transparent models and verifiable explanations. Recent surveys of financial sentiment analysis and XAI in finance report a surge in transformer-based models (e.g., FinBERT) alongside increasing use of SHAP/IG for post hoc attribution and growing interest in faithfulness metrics to guard against “explanations that look right for the wrong reasons” [

17,

18]. Empirical syntheses also highlight challenges from class imbalance, domain drift, and heterogeneous sources (headlines, filings, social media), recommending sector-aware analyses and multi-stage validation of economic significance—precisely the design adopted here (

Section 3.3;

Section 4.2).

Within this literature, FinBERT and its domain-specific fine-tunes offer strong baselines, yet explaining their predictions remains non-trivial. Gradient-based attributions (IG, SmoothGrad-IG variants) can yield informative token-level evidence, but 2023–2025 reviews underline persistent concerns about baseline selection, saturation, and faithfulness under masking, motivating quantitative perturbation tests (as we implement) rather than relying on saliency maps alone [

10,

11]. Meanwhile, intrinsically interpretable alternatives (e.g., EBM/GAM) have been advocated in high-stakes finance to ensure decomposable risk factors and audit trails [

24,

26]. Our study positions EBM and LR as glass-box comparators, extends FinBERT with IG/LIME/attention analyses, and connects explanations to economic validation (event studies, Granger causality, backtests), echoing best-practice guidance from recent finance-focused surveys.

3. Materials and Methods

Our methodology is designed as a multi-stage pipeline to construct, explain, and validate sentiment analysis models. The primary output is a daily sentiment score for each industrial sector derived from news headlines. To ground this technical pipeline in a practical context, the final stage is a rigorous econometric validation designed to assess the financial relevance and potential utility of these sentiment signals for decision-making.

The methodology of this study is predicated upon the principles of transparency, reproducibility, and comparative analysis. Our entire research workflow, from data acquisition and processing to model training and evaluation, exclusively employs publicly available datasets and open-source Python 3.13 libraries. This ensures that our findings can be independently verified and that the framework can be readily extended by other researchers. This commitment to an open and shareable workflow aligns with recent calls to improve reproducibility in machine learning research [

24,

31]. The primary objective is to rigorously evaluate the trade-off between predictive performance and model interpretability within the domain of financial sentiment analysis.

3.1. Datasets

The empirical basis of this study rests on three distinct datasets, each selected to probe different facets of model performance. A summary of their composition and class distributions is provided in

Table 1.

We utilize the “sentences_allagree” subset of the Financial PhraseBank (FPB), a widely accepted public benchmark. This corpus consists of 2264 phrases where human annotators reached a unanimous consensus on the sentiment label. Its clean, formal linguistic style serves as an ideal baseline for evaluating a model’s foundational performance.

The FiQA-Sentiment dataset offers a contrasting methodological challenge, comprising 498 financial news headlines. The language in this corpus is more concise and stylistically varied than that of the FPB. Its pronounced class imbalance provides a stringent test for a model’s robustness.

To assess model generalization to contemporary and diverse domains, we constructed a bespoke, manually annotated “gold-standard” corpus. This corpus consists of 1500 headlines, sampled from a larger collection of articles from H1 2025. The headlines are stratified across 10 distinct industry sectors to ensure broad topic coverage and test for sector-specific performance. This corpus functions as our primary testbed for evaluating out-of-domain generalization for our baseline models and serves as the foundation for training, validating, and testing our fine-tuned FinBERT model. The creation of new, domain-specific datasets is a critical contribution, as modern NLP models require high-quality, specialized data for tasks such as numerical reasoning and long-form question answering in finance [

32,

33] and transparent modelling frameworks for interpretability [

25,

26].

Although headlines can be broad, they are sector-tagged under GICS and validated against investable sector ETFs, which is why they’re appropriate for a financial objective.

We also introduce two additional model classes presented in

Section 3.2.

3.2. Sentiment Analysis Models

To investigate the performance-interpretability spectrum, we evaluate a methodologically diverse suite of models.

Lexicon-Based Models: These models operate on the principle of dictionary lookup, assigning sentiment based on the aggregation of polarity scores from predefined word lists. We evaluate two prominent examples: VADER, a general-purpose lexicon optimized for the syntax of short texts, and the Loughran–McDonald (LM) lexicon, curated specifically for financial terminology [

19]. For each, a continuous polarity score is calculated per headline, and classification thresholds are subsequently optimized on the training data to maximize the macro F1-score.

Interpretable ML Baseline (TF-IDF + LR): Our designated “glass box” model is a classic natural language processing pipeline chosen for its inherent transparency. Text is transformed into a numerical matrix using a Term Frequency-Inverse Document Frequency (TF-IDF) vectorizer, capturing the relative importance of unigrams and bigrams. A multinomial Logistic Regression (LR) classifier is then trained on these features. This linear model is inherently interpretable, a characteristic further enhanced through the application of SHAP.

Glass-Box Non-Linear Baseline (EBM): We include an Explainable Boosting Machine (EBM) as a strong, non-linear but fully interpretable baseline. EBMs are a form of Generalized Additive Model (GAM) that learn a flexible function for each feature independently, making their predictions decomposable and easy to visualize without requiring post hoc explanation methods like SHAP.

Hybrid Model (FinBERT + LR): To bridge the gap between transformers and interpretable models, we test a hybrid approach. We first use FinBERT to generate a 768-dimension sentence embedding from the [CLS] token for each headline. These rich, contextual embeddings are then used as input features for a simple, interpretable multinomial Logistic Regression classifier.

State-of-the-Art Benchmark (FinBERT): To establish an empirical upper bound on performance, we employ ProsusAI/finbert. As a powerful transformer model pre-trained on a vast financial corpus, its deep contextual understanding of domain-specific language makes it a formidable benchmark. Its capabilities are assessed in two distinct modes: zero-shot inference and fine-tuning.

FinBERT (Fine-Tuned): To create our top-performing model, the pre-trained ProsusAI/finbert model was fine-tuned on a training partition of our 1500-sample gold-standard dataset. This approach tests the model’s ability to adapt its general financial knowledge to the specific nuances of our multi-sector news headline task.

3.3. Evaluation Protocol

Model performance is quantified using Accuracy and Macro F1-Score. The Macro F1-Score is afforded particular importance due to its ability to provide a fair assessment of performance on imbalanced datasets by averaging the per-class F1-score without weighting by class frequency. On the public FPB and FiQA datasets, all models are evaluated on a stratified 80/20 train–test split with a fixed random seed. The 1500-headline US Multi-Sector corpus is used exclusively as a hold-out test set to rigorously test generalization.

The 1500-headline US Multi-Sector corpus is used exclusively as a hold-out test set for the baseline models. For the fine-tuned FinBERT model, this corpus was partitioned into training, validation, and a final 15% held-out test set to ensure a fair and rigorous evaluation of its performance on unseen data.

3.4. Interpretability, Faithfulness, and Temporal Analysis

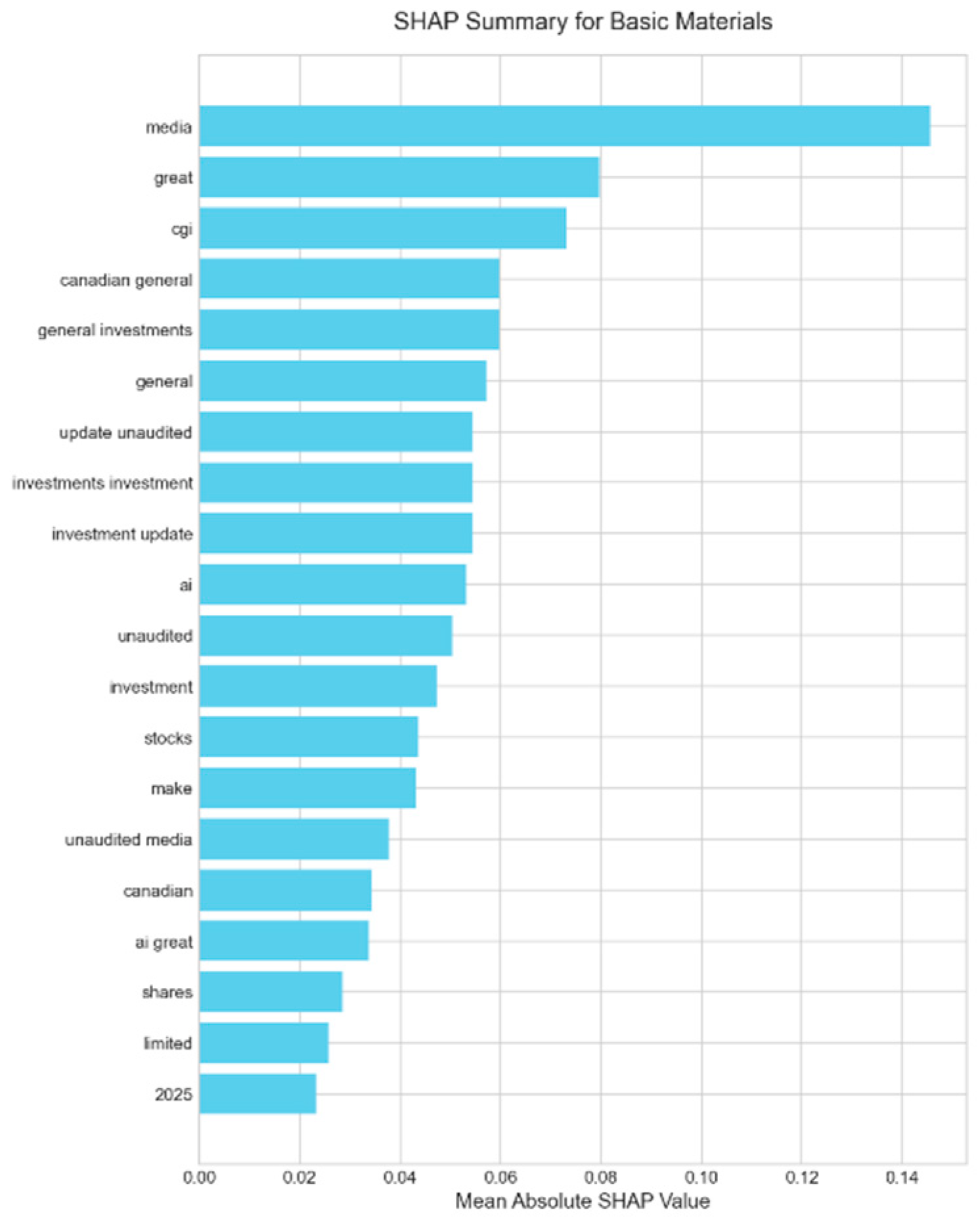

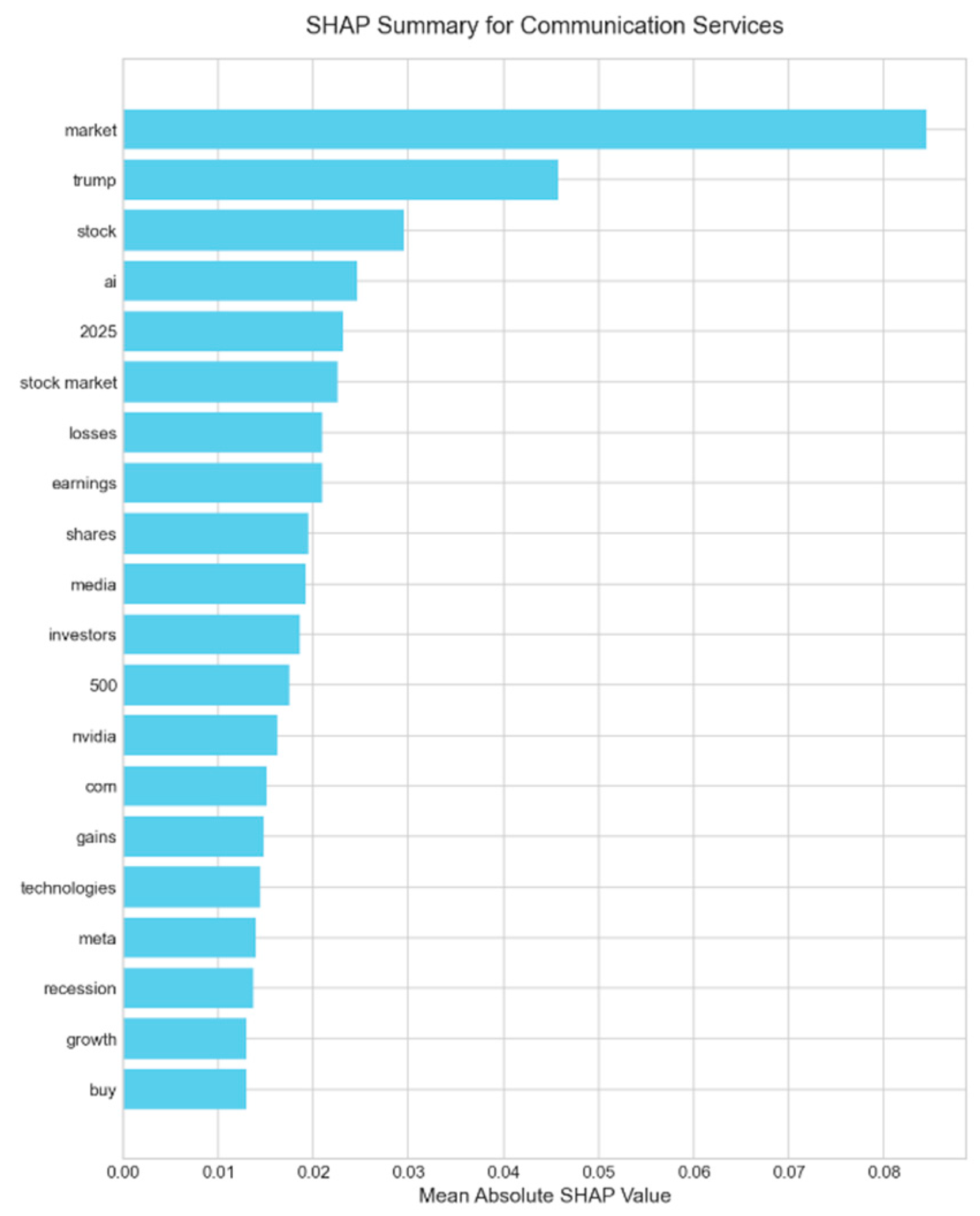

The transparency of our baseline model is systematically interrogated using the SHAP framework. By employing SHAP’s LinearExplainer, we compute the exact, additive contribution of each token to the Logistic Regression model’s output for every prediction. This method enables the generation of global feature importance plots that reveal the model’s underlying decision-making logic by identifying the most influential terms across the entire dataset.

Furthermore, we investigate the temporal dynamics of financial discourse through a regime shift analysis. The full Marketaux dataset is partitioned into two distinct periods: Quarter 1 (January–March 2025) and Quarter 2 (April–June 2025). Using VADER to generate weak supervision labels, we train a separate TF-IDF + LR model on the data from each quarter. This technique of using an automated, heuristic-based labeler (VADER) to provide training data for a supervised model is a form of weak supervision, a practical approach for creating labeled datasets without manual annotation costs [

34]. Also, by systematically comparing the SHAP-derived importance rankings of tokens between the two models, we can quantitatively identify which linguistic features gained or lost influence over time. This methodology facilitates a shift from static sentiment measurement to a dynamic understanding of evolving market narratives.

We implement deletion-based AOPC (removing tokens in the order indicated by the explainer) to quantify how well IG, LIME, and attention-rollout identify truly influential tokens [

12]. We also apply Wilcoxon signed-rank tests between methods, following faithfulness-focused guidance [

10,

11]. For context, comprehensiveness/sufficiency and ROAR are alternative checks [

29].

Uncertainty and calibration audit. We compute reliability diagrams and Expected Calibration Error (ECE) and apply temperature scaling to improve probability calibration [

16,

35]. In deployment, calibrated thresholds and optional conformal-style set predictions can control error rates for risk-sensitive use [

36].

3.5. Open-Source Implementation and Reproducibility

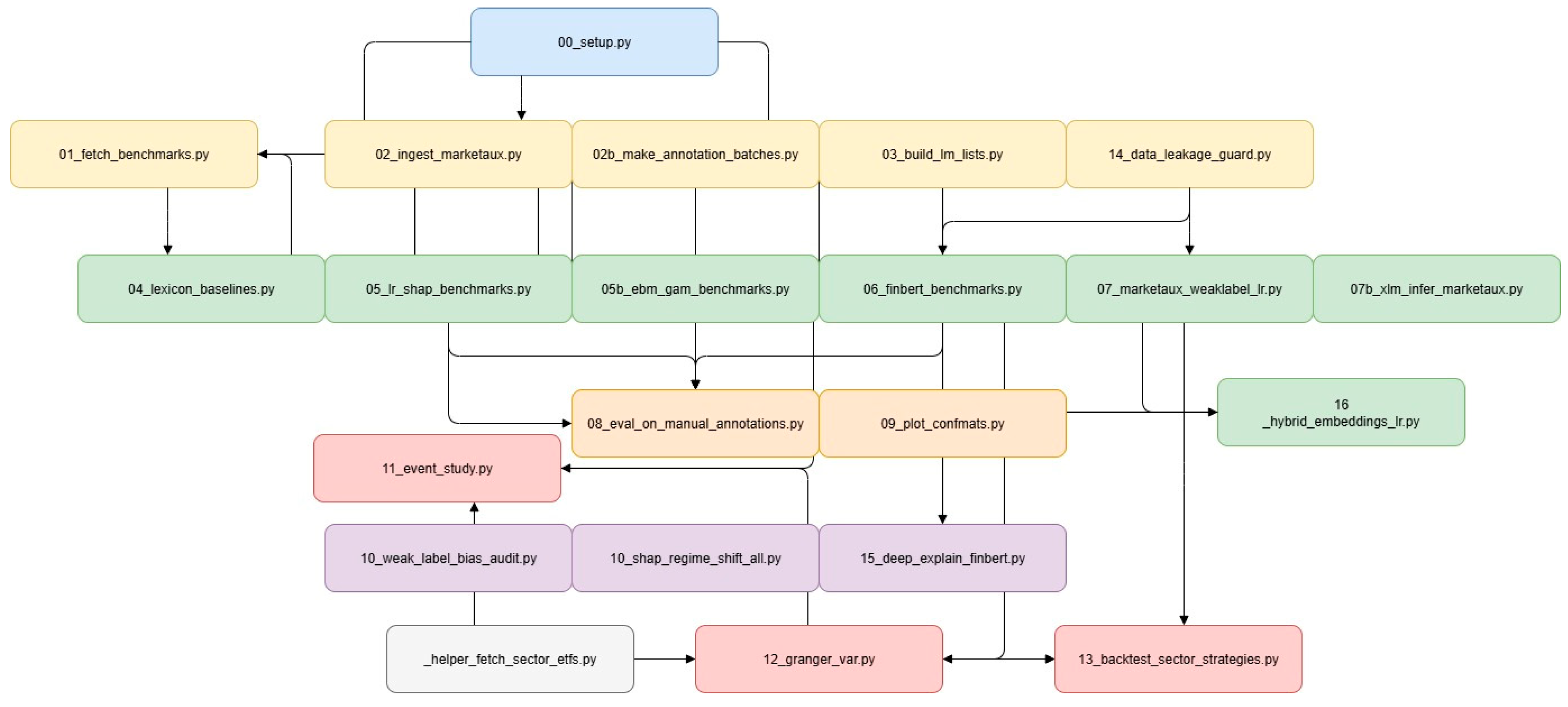

To ensure clarity and reproducibility, we developed the xai-finnews-sentiment framework. All source code, configuration files, and intermediate artifacts produced during this research are publicly released in the associated GitHub repository under the permissive MIT License (Version 1.0.0). The pipeline integrates multiple stages, from data collection and preprocessing to model training, evaluation, and explainability analysis. The methodology is summarized schematically in

Figure 1.

3.6. Code Availability and Repository Layout

All materials for this study—source code, configuration files, and intermediate artifacts—are openly available in the xai-finnews-sentiment repository (MIT License) at:

https://github.com/MaraAlexandru/xai-finnews-sentiment/ (accessed on 27 August 2025). The repository is built around a single idea: end-to-end reproducibility. Every figure, table, and numerical result in the manuscript can be regenerated from the workflow, with no hidden steps or manual curation.

The layout mirrors the narrative of the paper. It guides readers from data acquisition and preparation, through modeling and explainability, and into temporal analysis and econometric validation, before culminating in the final outputs used in the article. Public benchmark datasets are retrieved automatically; domain-specific news data are incorporated via documented procedures that respect licensing constraints. Expert lexicons are provided with clear provenance and simple regeneration paths to ensure legal clarity across jurisdictions.

Analysis routines map one-to-one onto the methodological elements reported here: comparative benchmarks across interpretable and transformer-based models, a hybrid approach that bridges performance and transparency, systematic explainability audits that test the faithfulness of explanations, and econometric evaluations that assess real-world relevance. The intent is not merely to share code, but to make the research process legible, so that readers can follow the same path from raw inputs to published claims.

All outputs—metrics, reports, plots, and figure assets—are generated directly by the pipeline and collected in a single place for inspection. Dependencies are resolved on demand, and proprietary content is never redistributed; instead, the workflow operates on user-provided exports with clear instructions.

Licensing and provenance are explicit: original code under MIT, the manually annotated headline set under CC BY 4.0, the manuscript and figures under CC BY 4.0, and third-party resources under their original terms. Taken together, the repository is designed to support transparent verification and easy extension: each result in the paper can be traced to a specific dataset, analysis step, and output artifact, enabling the community to audit, adapt, and build upon this work.

3.7. Assessing the Economic Significance of Sentiment

We define sector events via 63-day rolling z-score thresholds (±1.5) on daily sector sentiment derived from headlines. For each event, we compute sector ETF CAR over [−5, +5] using a market model with SPY as the proxy; predictive structure is tested via VAR-based Granger on sentiment and ETF returns. Practical utility is evaluated with simple, rules-based long-only and long-short strategies on sector ETFs with 5 bps costs, emphasizing the economic properties of the signal rather than building a forecasting oracle. To formally test for predictive power, we employ Granger causality analysis on a bivariate time series of daily mean sentiment and the corresponding ETF’s daily return. We fit a Vector Autoregression (VAR) model and conduct F-tests to evaluate whether past sentiment values Granger-cause future returns, and vice versa.

To evaluate practical utility, we backtest a simple, rules-based trading strategy for each sector based on the daily sentiment z-score, accounting for a transaction cost of 5 basis points (0.05%) per trade. We evaluate the strategies by calculating their Sharpe Ratio, annualized return (CAGR), and maximum drawdown.

This validation stage is not intended to create a standalone prediction model but to test the financial properties of the sentiment signal. Specifically, we use an event study to measure market reaction to sentiment spikes, Granger causality tests to evaluate predictive vs. reactive properties, and a strategy backtest to assess practical utility net of costs.

4. Results

Our empirical analysis unfolds in several stages. We first establish performance baselines on public datasets before conducting a deep dive into model performance on our new, 1500-headline gold-standard corpus. This is followed by a rigorous, quantitative audit of the explainability methods for our best model. Finally, we investigate the economic properties and practical utility of the generated sentiment signal through a series of econometric tests.

4.1. Model Performance on Public Benchmarks

To ground our study, we first evaluated our models on two widely used public benchmarks: the Financial PhraseBank (FPB) and the FiQA headlines dataset. These tests serve to validate the relative capabilities of each model architecture on standardized tasks. The results are summarized in

Table 2.

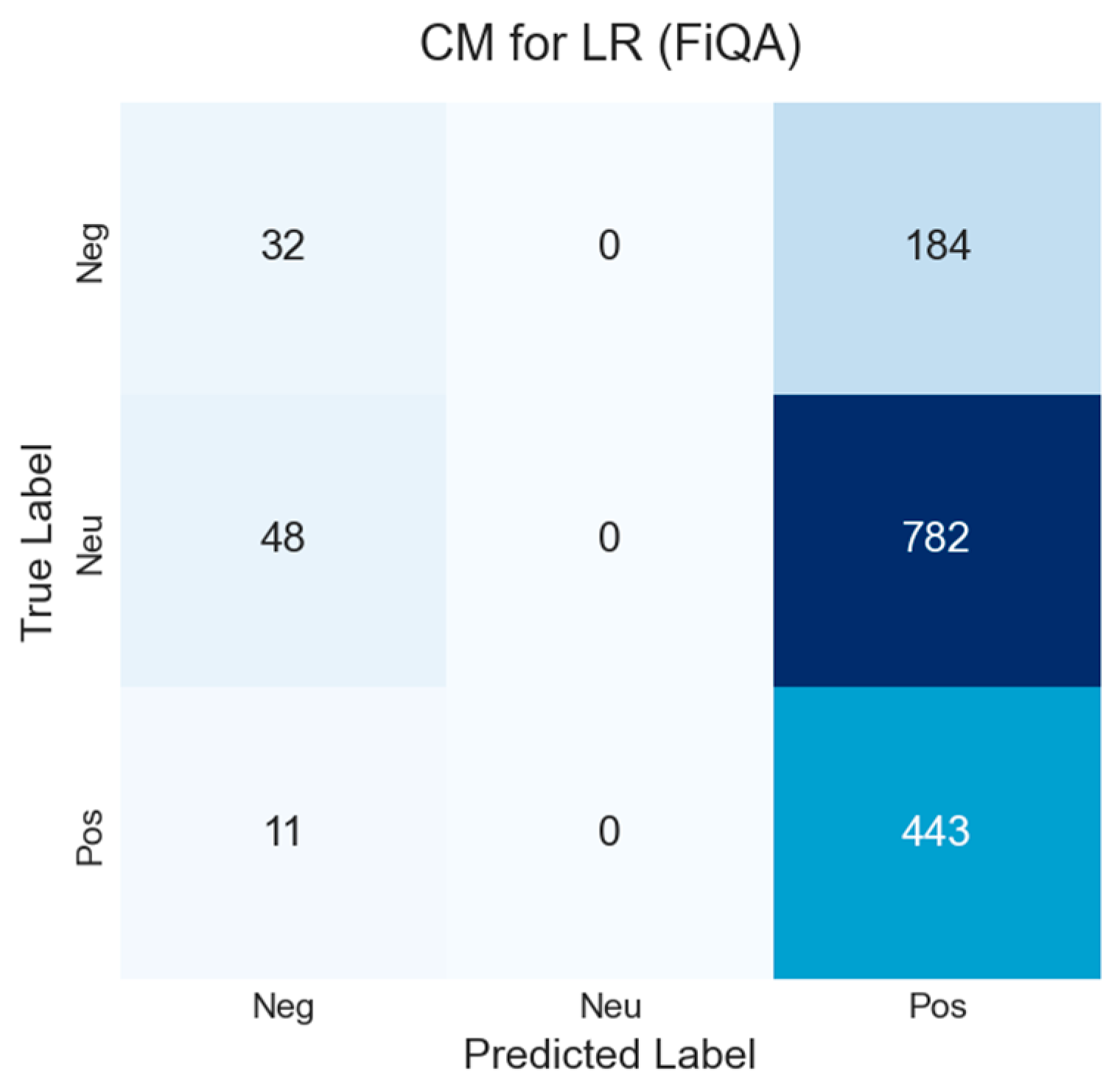

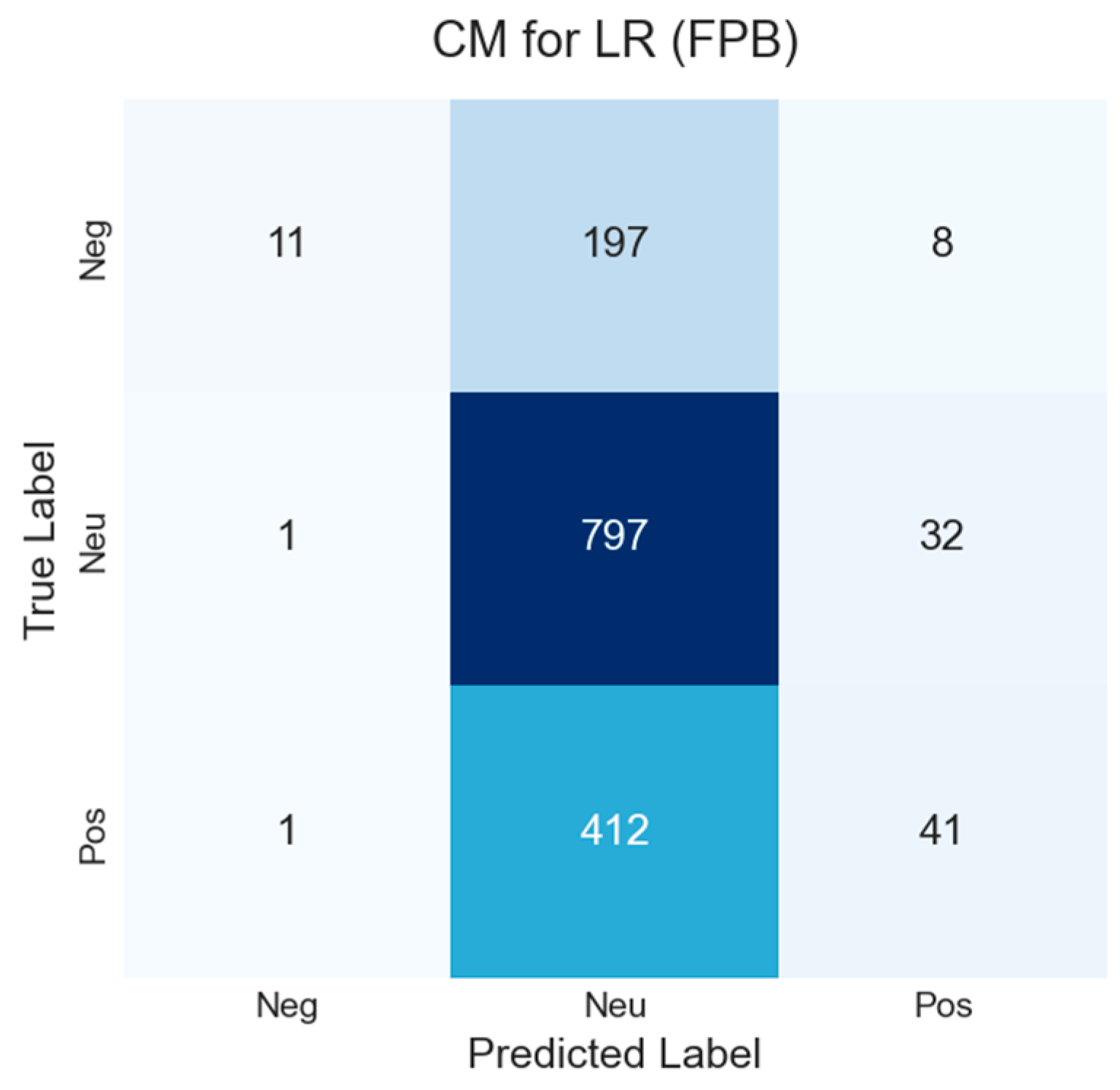

On the clean, formal language of the FPB, the FinBERT + LR (Hybrid) model achieved near-perfect accuracy, with a macro F1-score of 0.981. This demonstrates the immense power of contextual embeddings from a domain-trained transformer when applied to a straightforward classification task. On the more challenging FiQA dataset, which is characterized by greater stylistic variance and significant class imbalance, the hybrid model also proved superior, achieving a macro F1-score of 0.603. The lexicon-based methods, particularly the domain-specific Loughran–McDonald (LM) lexicon, struggled significantly on the imbalanced FiQA data (F1 of 0.345), highlighting the limitations of non-contextual, rule-based approaches on noisy, real-world text.

Performance is measured on a held-out test set. The hybrid model demonstrates state-of-the-art performance, while lexicon methods provide a solid baseline on simpler data but struggle with imbalance.

4.2. Generalization on the Gold-Standard Corpus: The Critical Value of Fine-Tuning

The definitive test of a model’s utility is its ability to generalize to new, unseen data that reflects a real-world distribution of topics and styles. We evaluated all models on a held-out test partition of our 1500-headline multi-sector gold-standard corpus. The results, presented in

Table 3, reveal a clear performance hierarchy and provide the central finding of our performance analysis.

Our fine-tuned FinBERT model emerges as the unambiguous top performer, achieving a robust accuracy of 71.6% and a macro F1-score of 0.707. This result is not only strong but represents a significant performance uplift of +14.9% in accuracy and +0.152 in macro F1-score over the standard zero-shot FinBERT baseline. This starkly illustrates that fine-tuning, even on a modestly sized but high-quality, domain-specific dataset, is important for unlocking the true potential of large language models for specialized tasks.

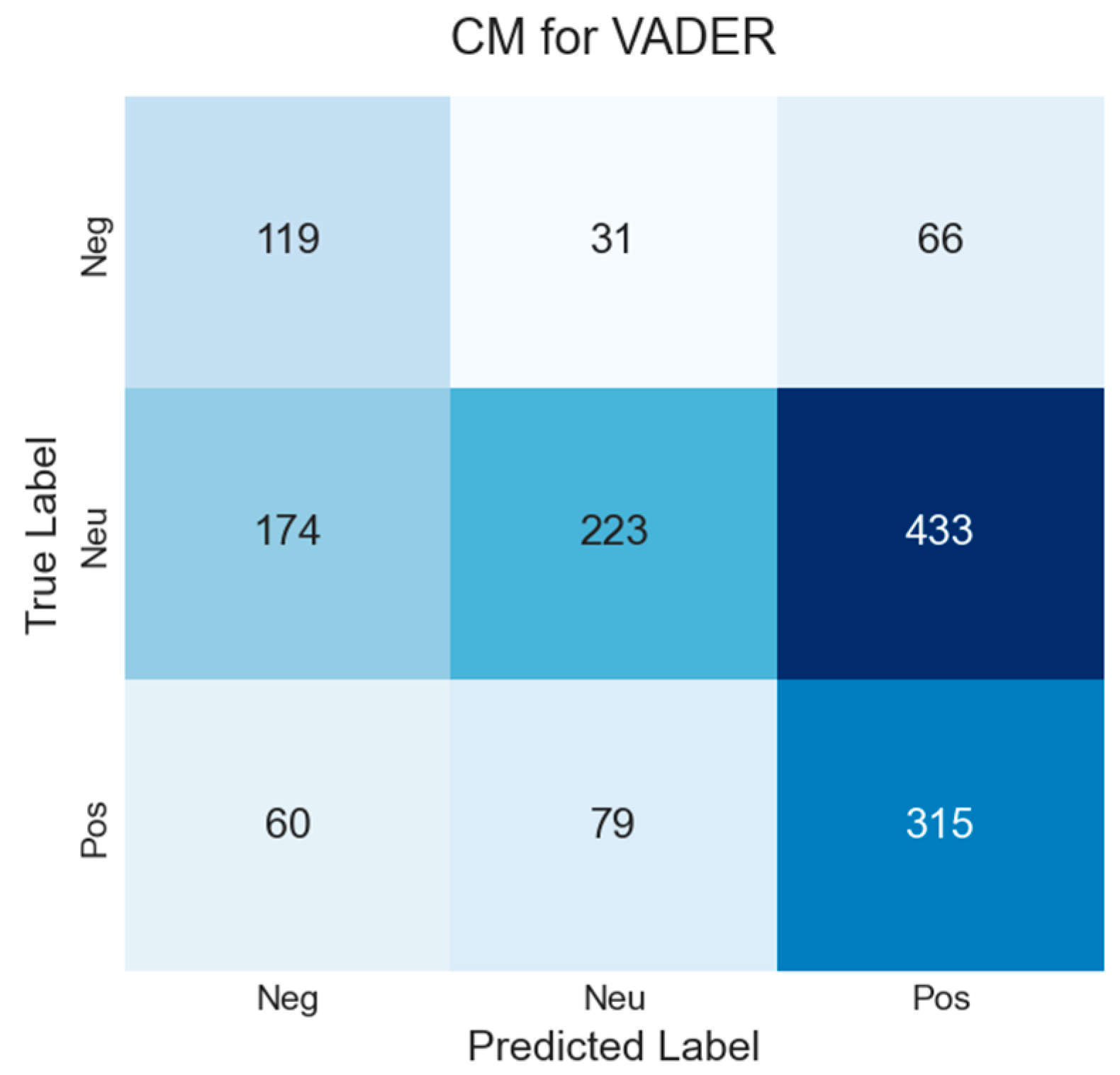

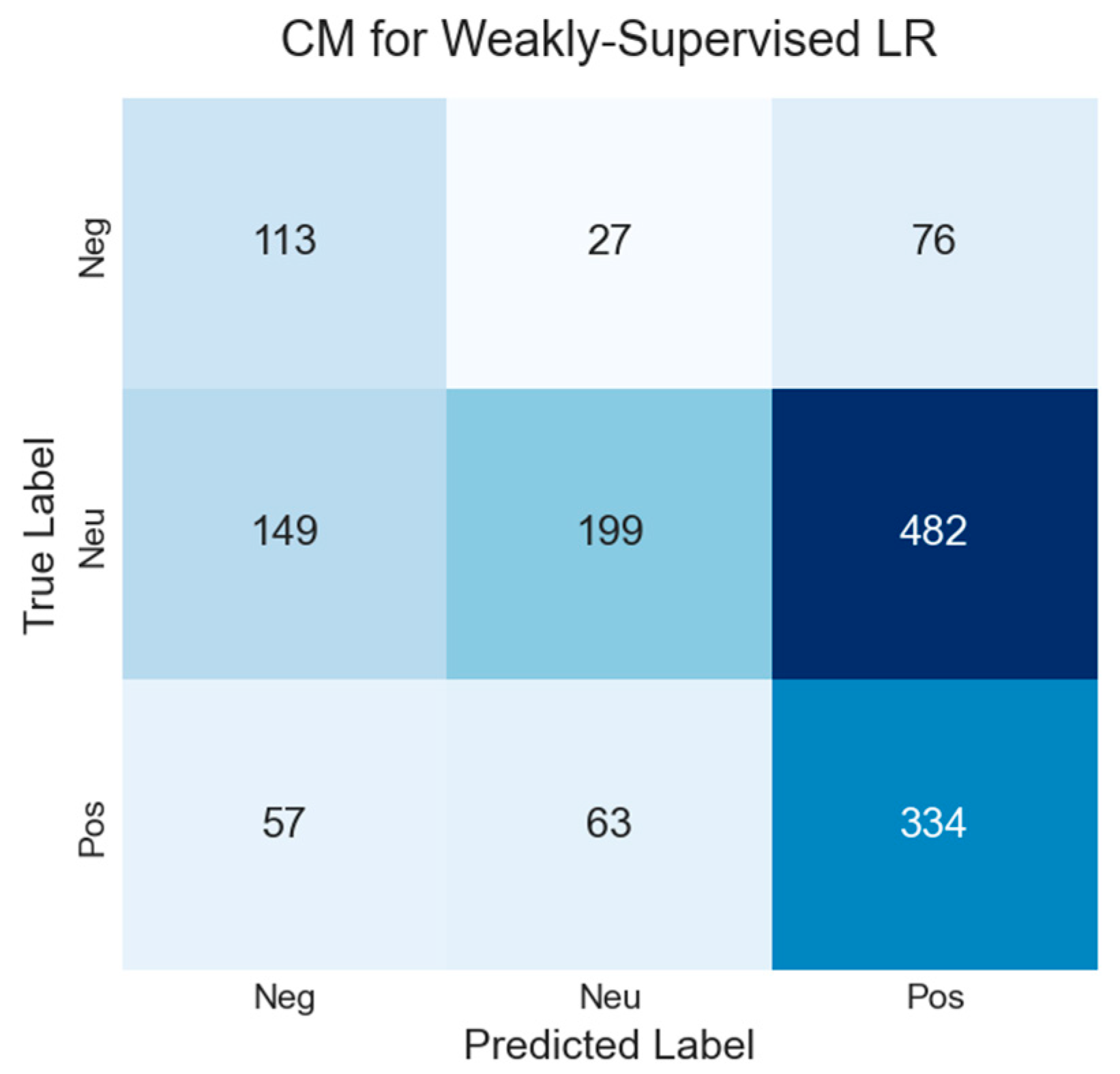

The baselines exhibit varied but generally weaker performance. The zero-shot FinBERT, while the best of the non-fine-tuned models, still only achieves a macro F1-score of 0.555, underscoring the challenge of out-of-domain generalization. Lexicon-based methods like VADER (F1 of 0.433) and even the domain-specific LM lexicon (F1 of 0.482) perform poorly, confirming their inability to adapt to the diverse and noisy language of multi-sector headlines. The model trained on weak supervision (Weakly Supervised LR) performs similarly to the simple lexicon methods, reinforcing the limitations of this approach, which we explore further in

Appendix A.1.

Models were evaluated on an unseen test set derived from the 1500 annotated headlines. Fine-tuning provides a decisive performance advantage over all other baseline and zero-shot methods.

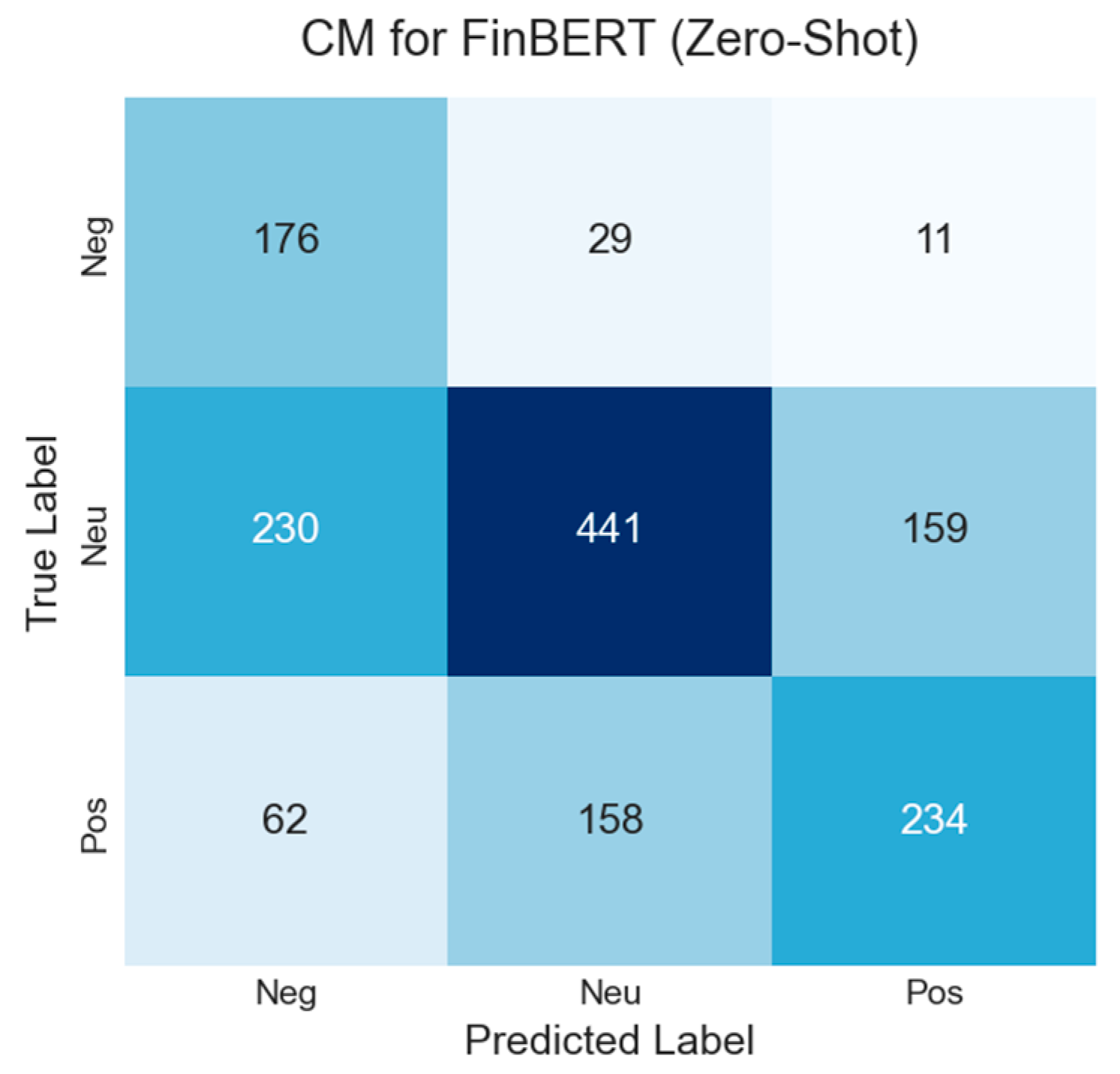

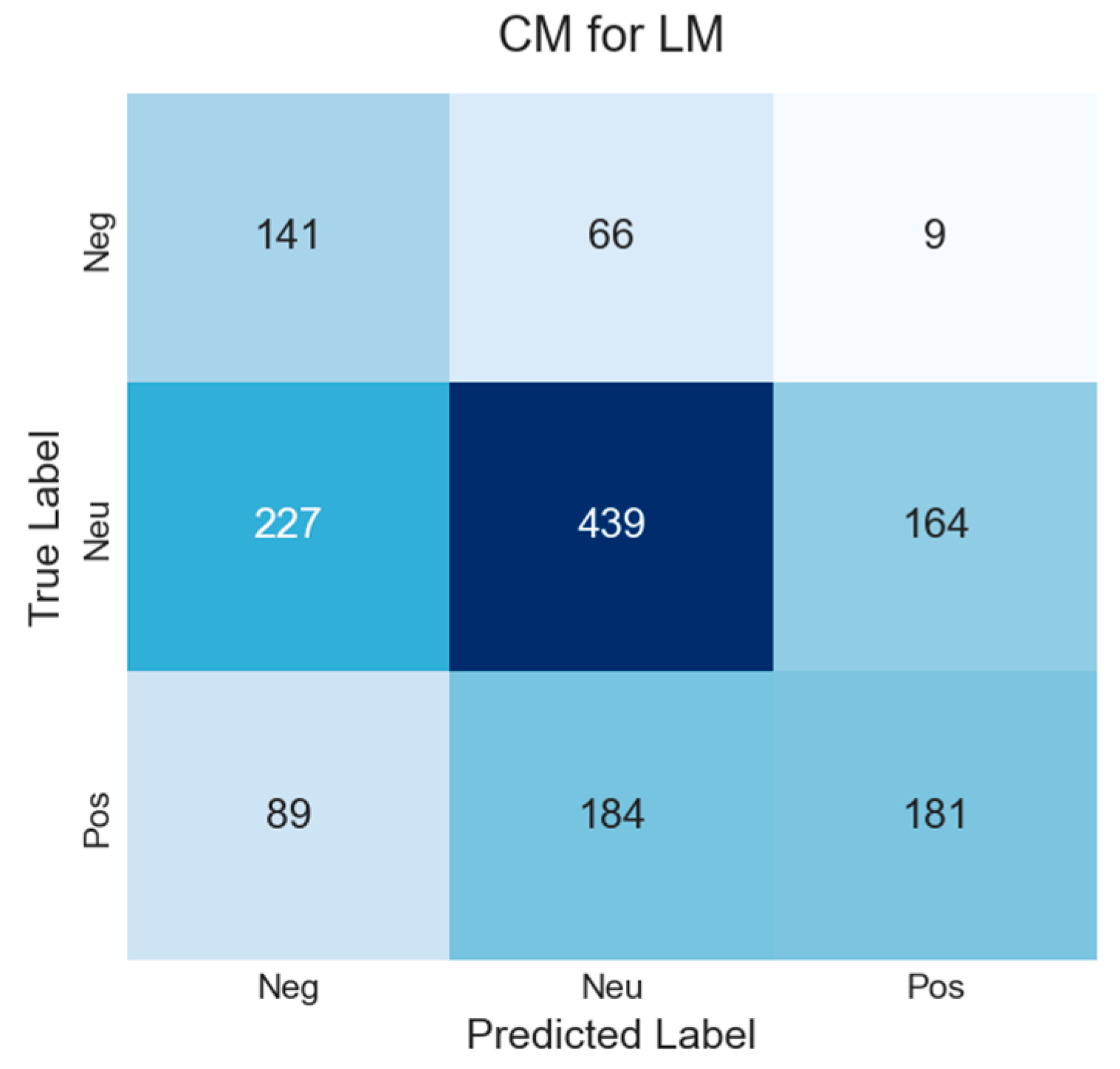

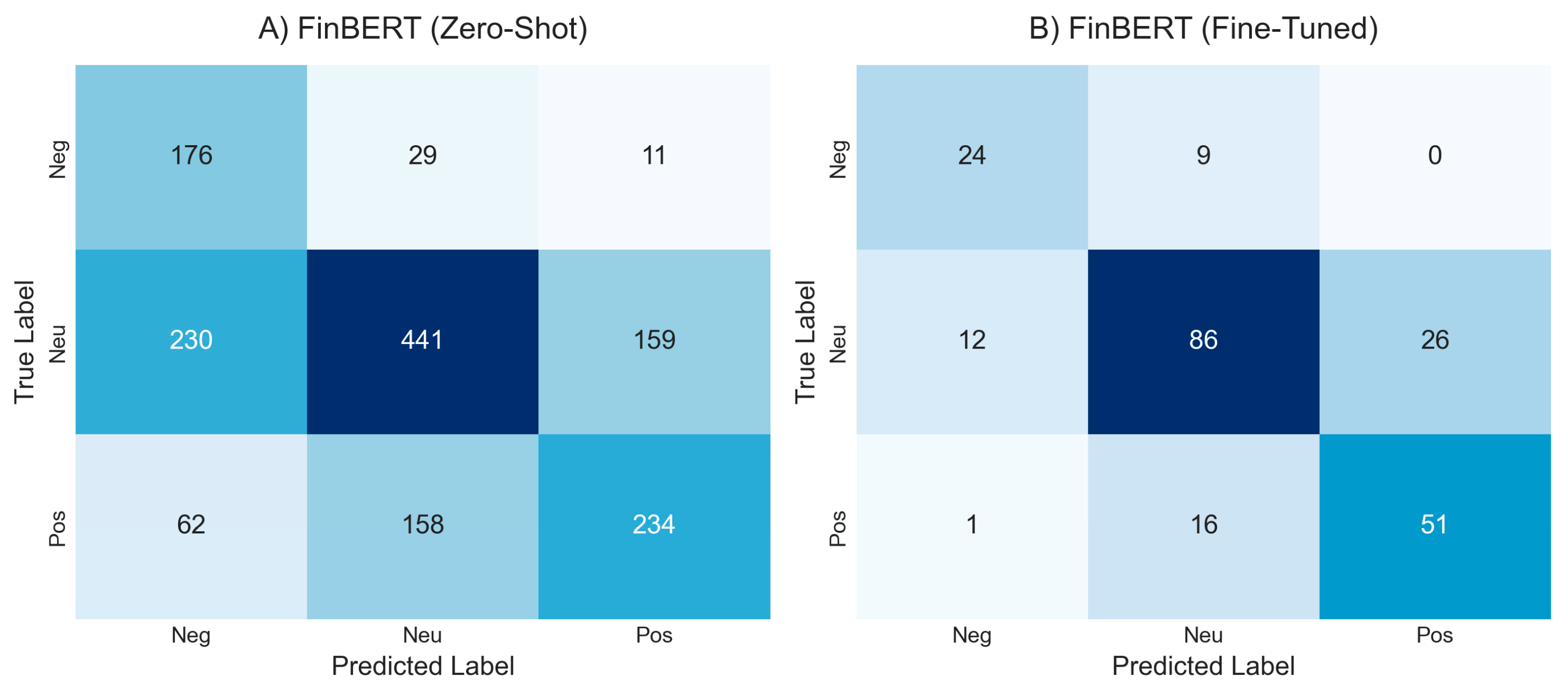

A granular, class-level view of this performance gap is provided in

Figure 2. The confusion matrix for the zero-shot FinBERT (A) shows significant errors, particularly in misclassifying both negative and positive headlines as neutral (230 and 158 instances, respectively). In stark contrast, the fine-tuned FinBERT (B) demonstrates a much more accurate and balanced profile. It drastically reduces these critical misclassifications, indicating a superior ability to discern subtle sentiment cues across all three classes. Detailed confusion matrices for every baseline model are available for review in

Appendix A.1.

Further analysis reveals that performance varies considerably across industrial sectors, as detailed in

Appendix A.1. This sectoral variance highlights the domain-specific nature of financial language and reinforces the need for sector-aware modeling and evaluation, a core principle of our workflow.

4.3. Auditing Explanations and Uncertainty: From Plausibility to Trust

Achieving high accuracy is only the first step; for a model to be trustworthy in a financial context, its reasoning must be scrutable. This section moves beyond generating plausible explanations to quantitatively auditing their faithfulness.

4.3.1. Explaining the Interpretable Baselines with SHAP

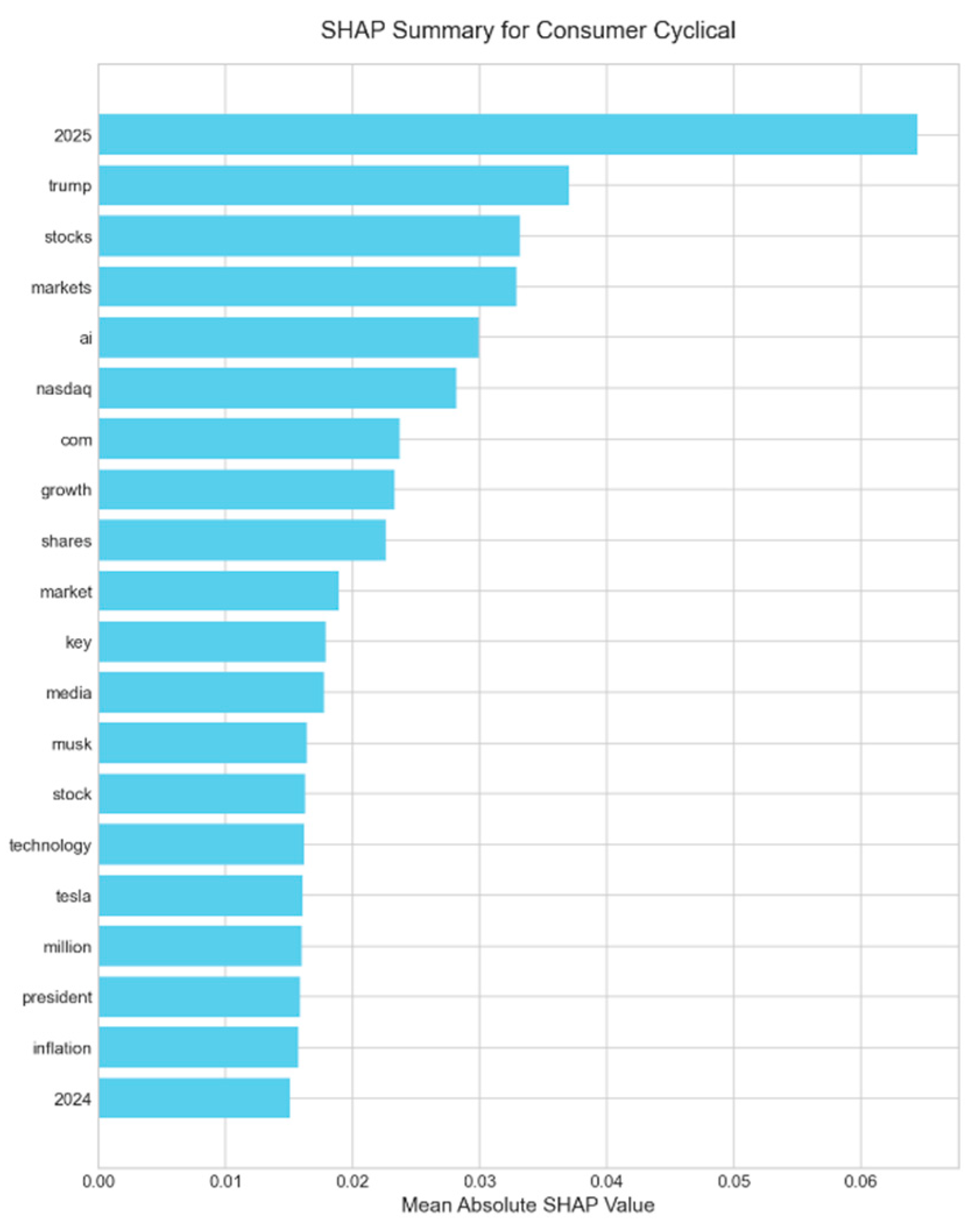

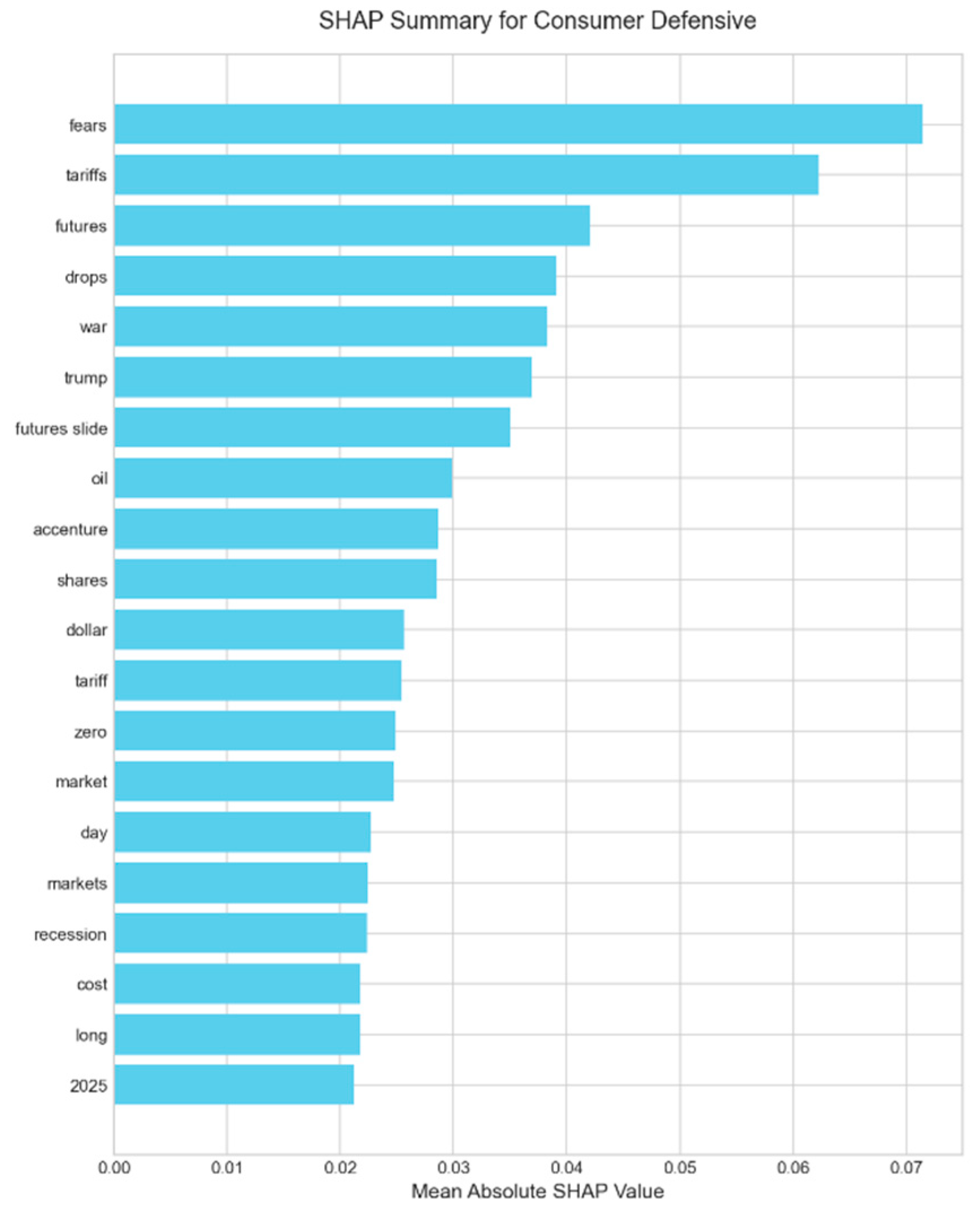

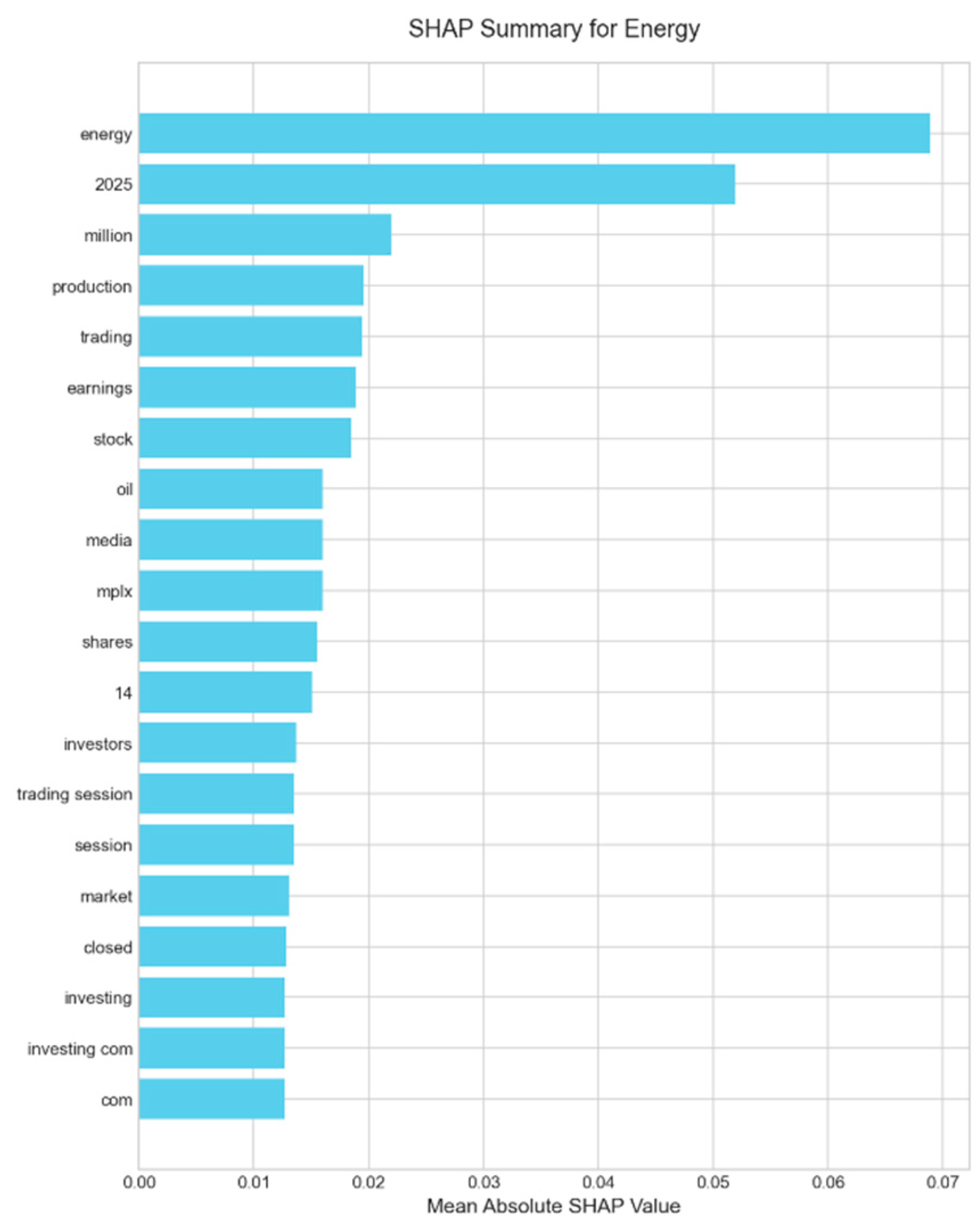

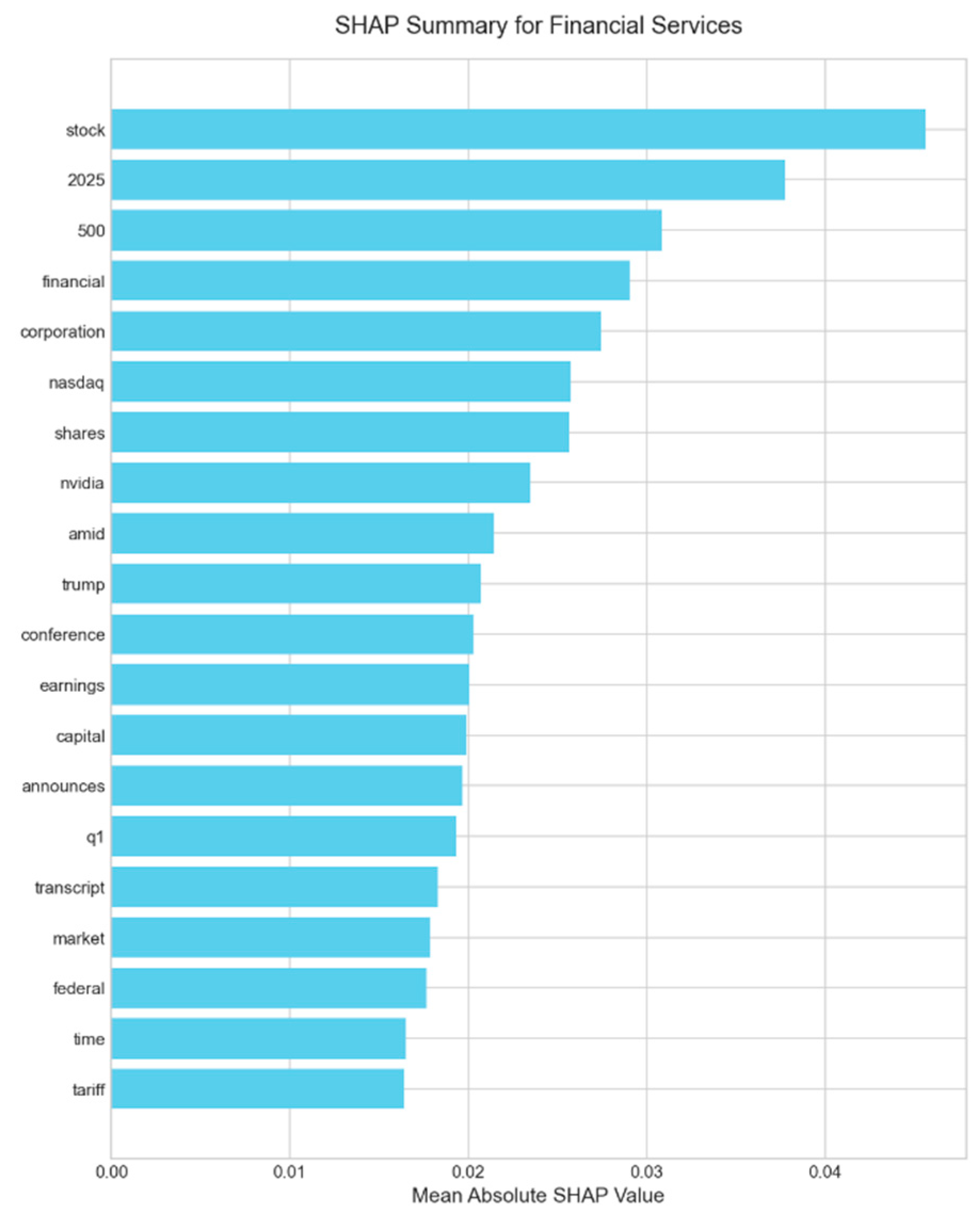

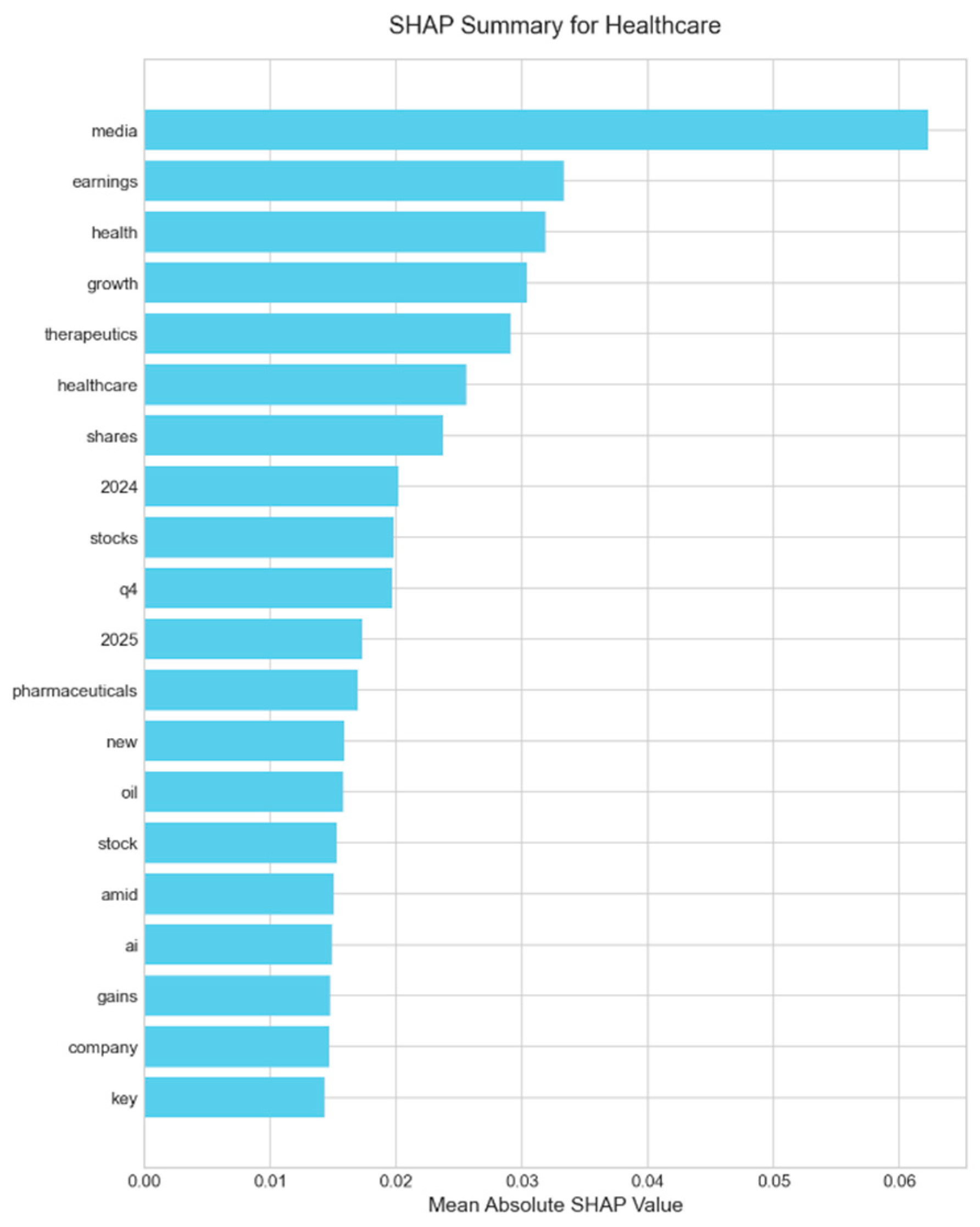

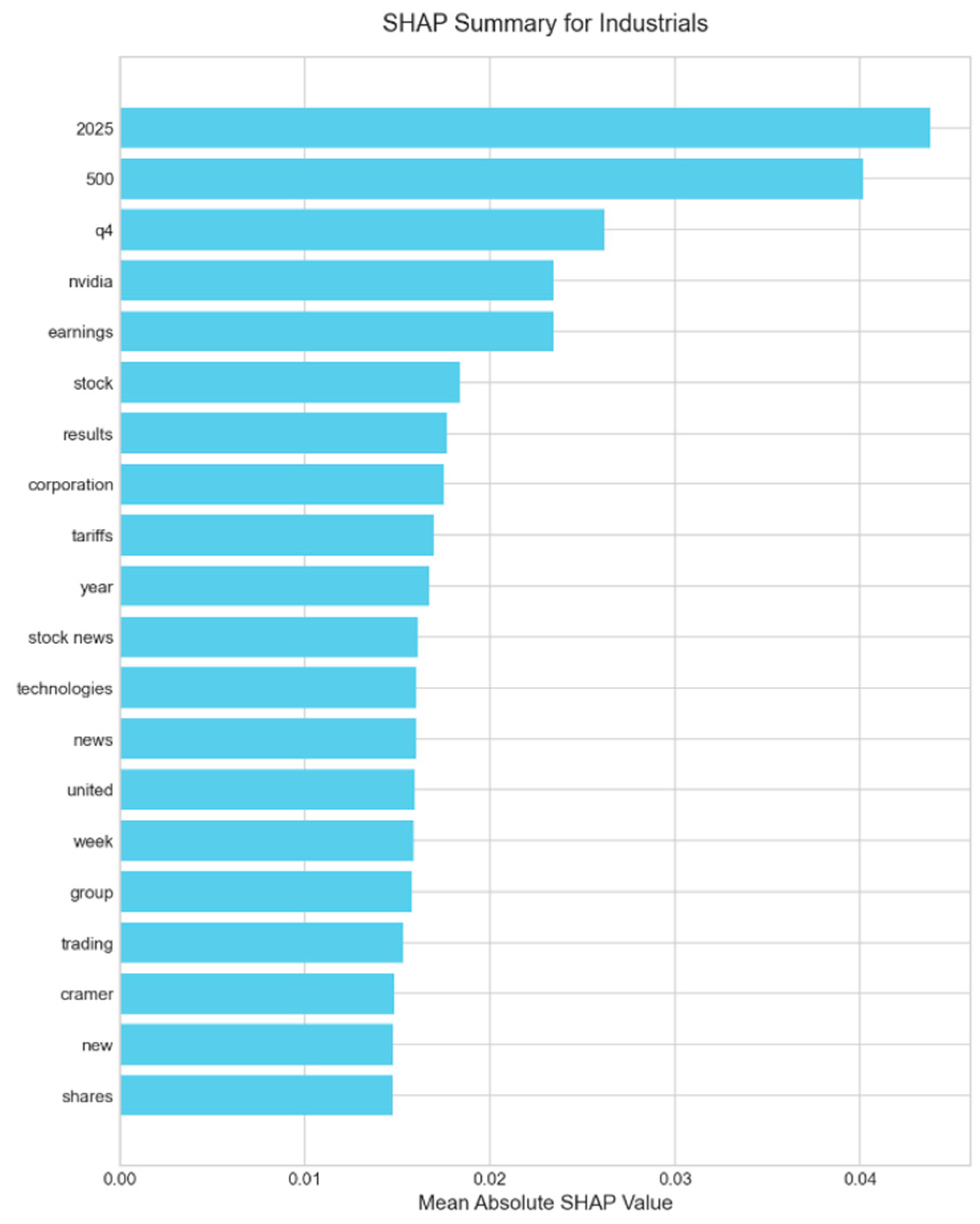

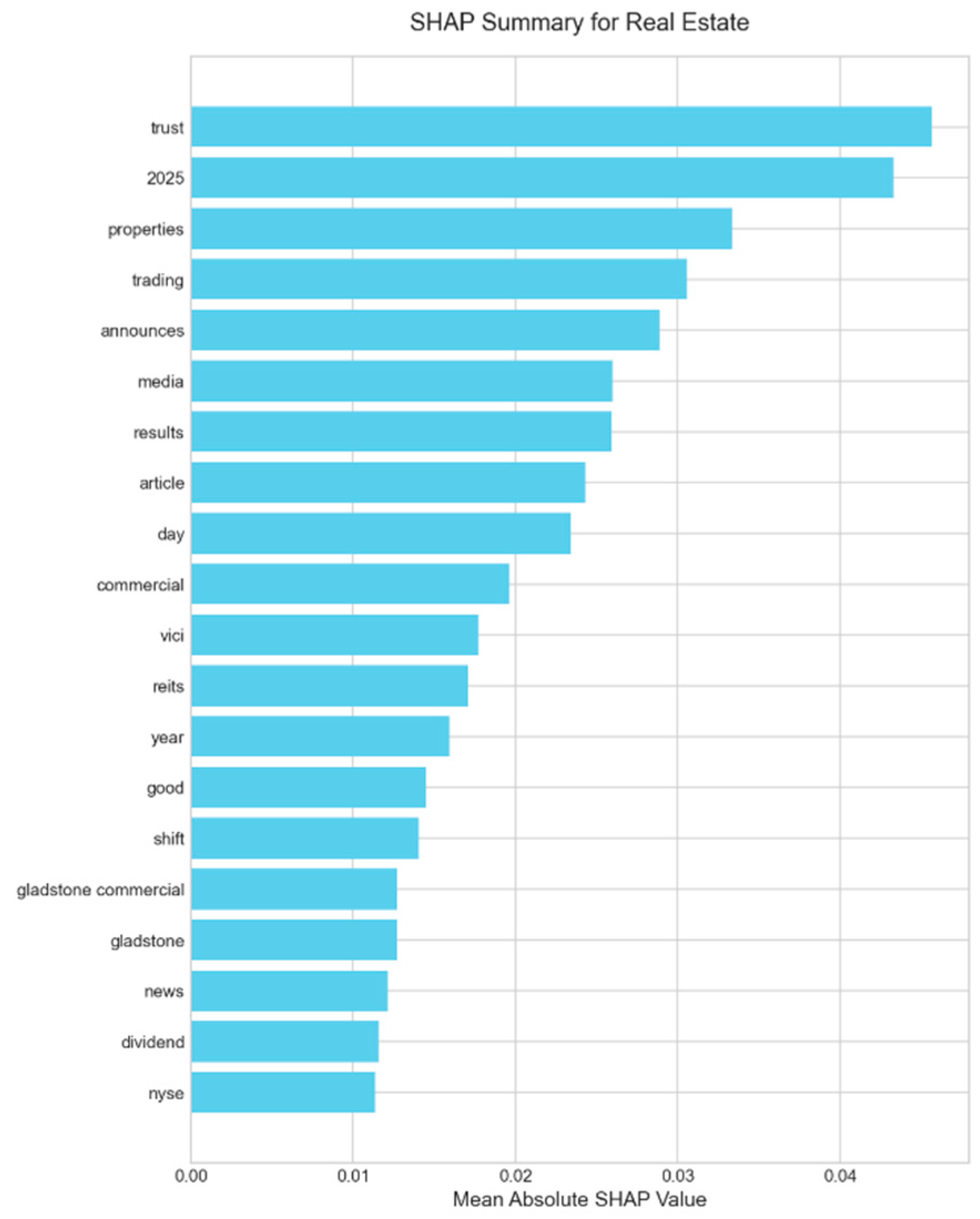

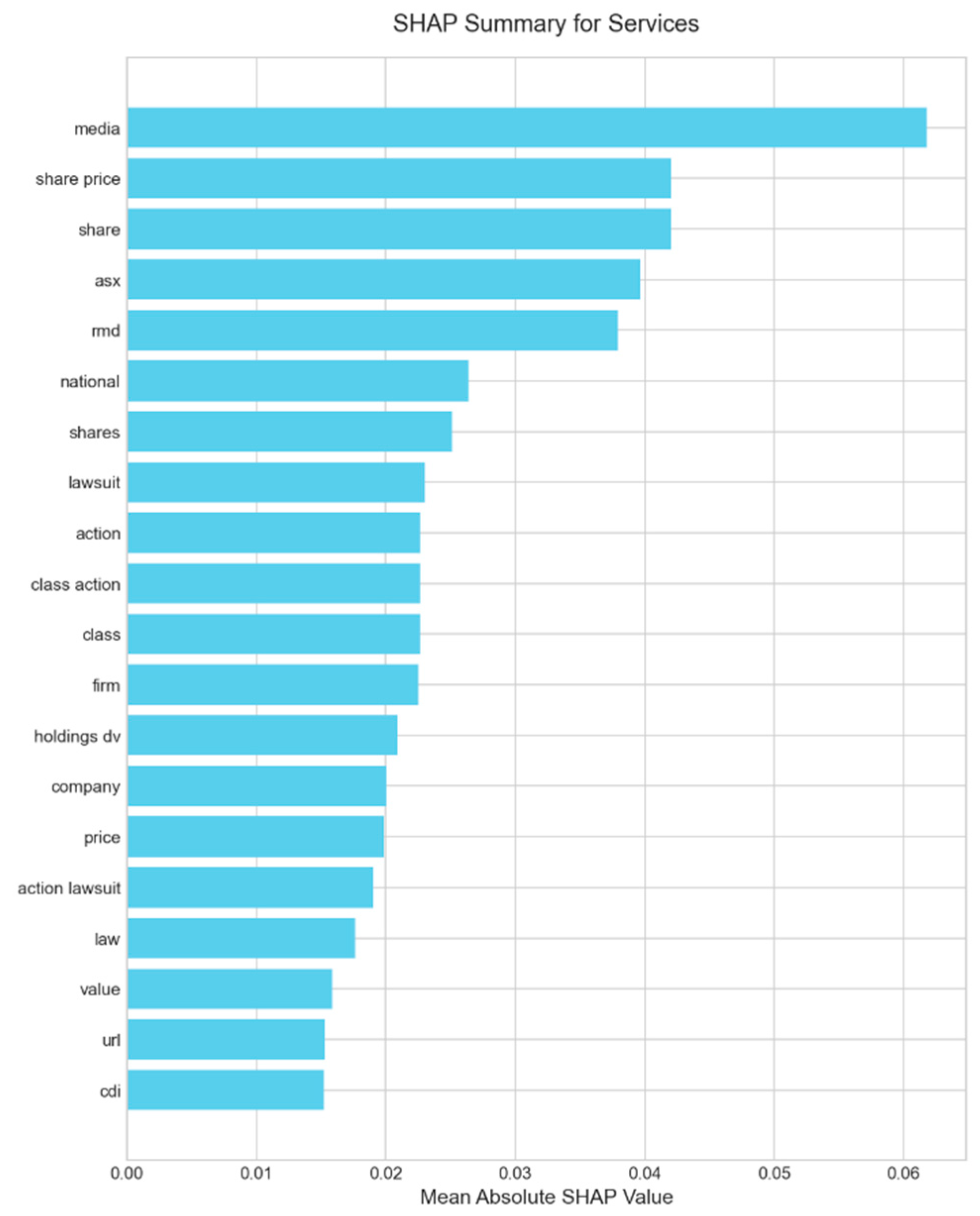

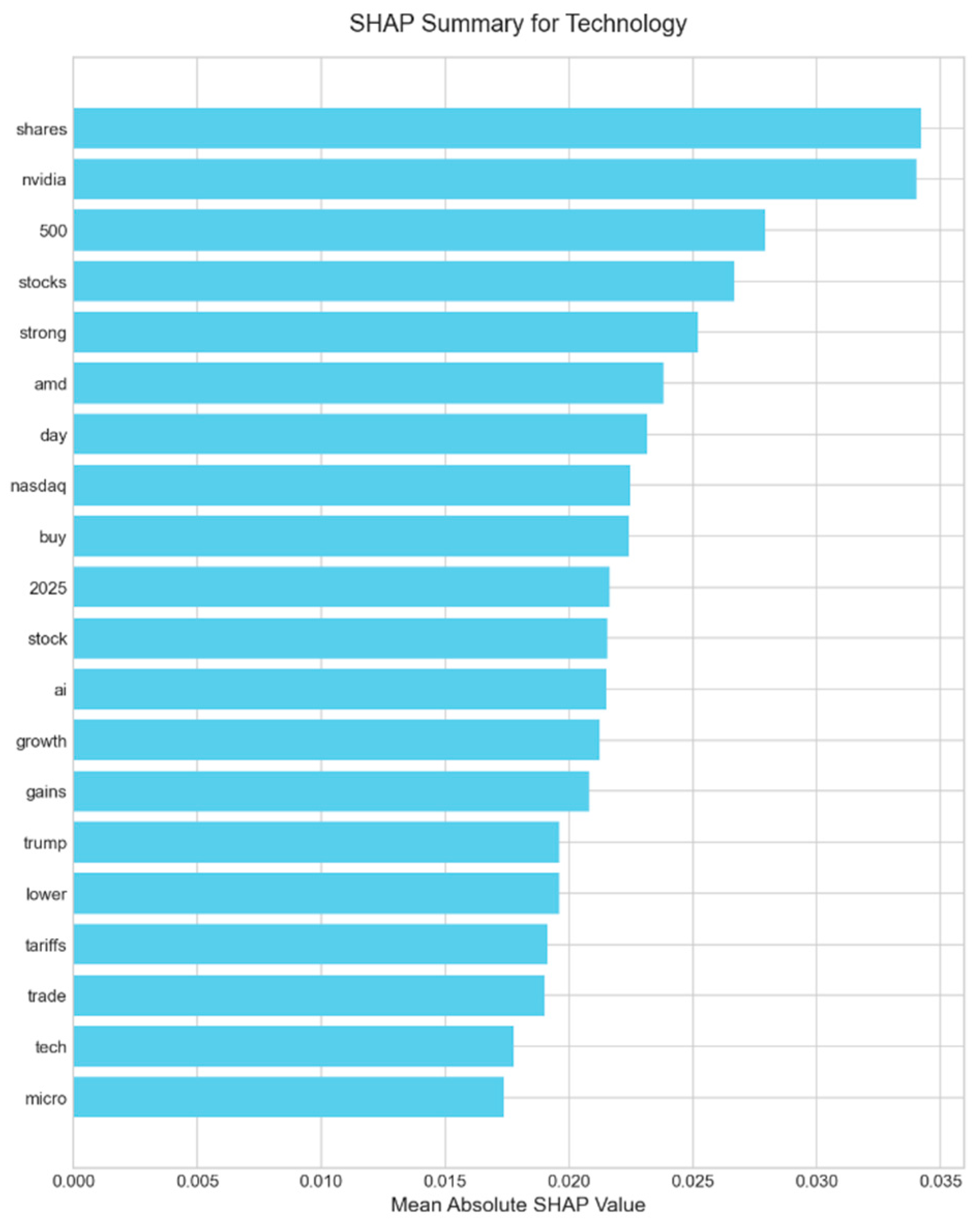

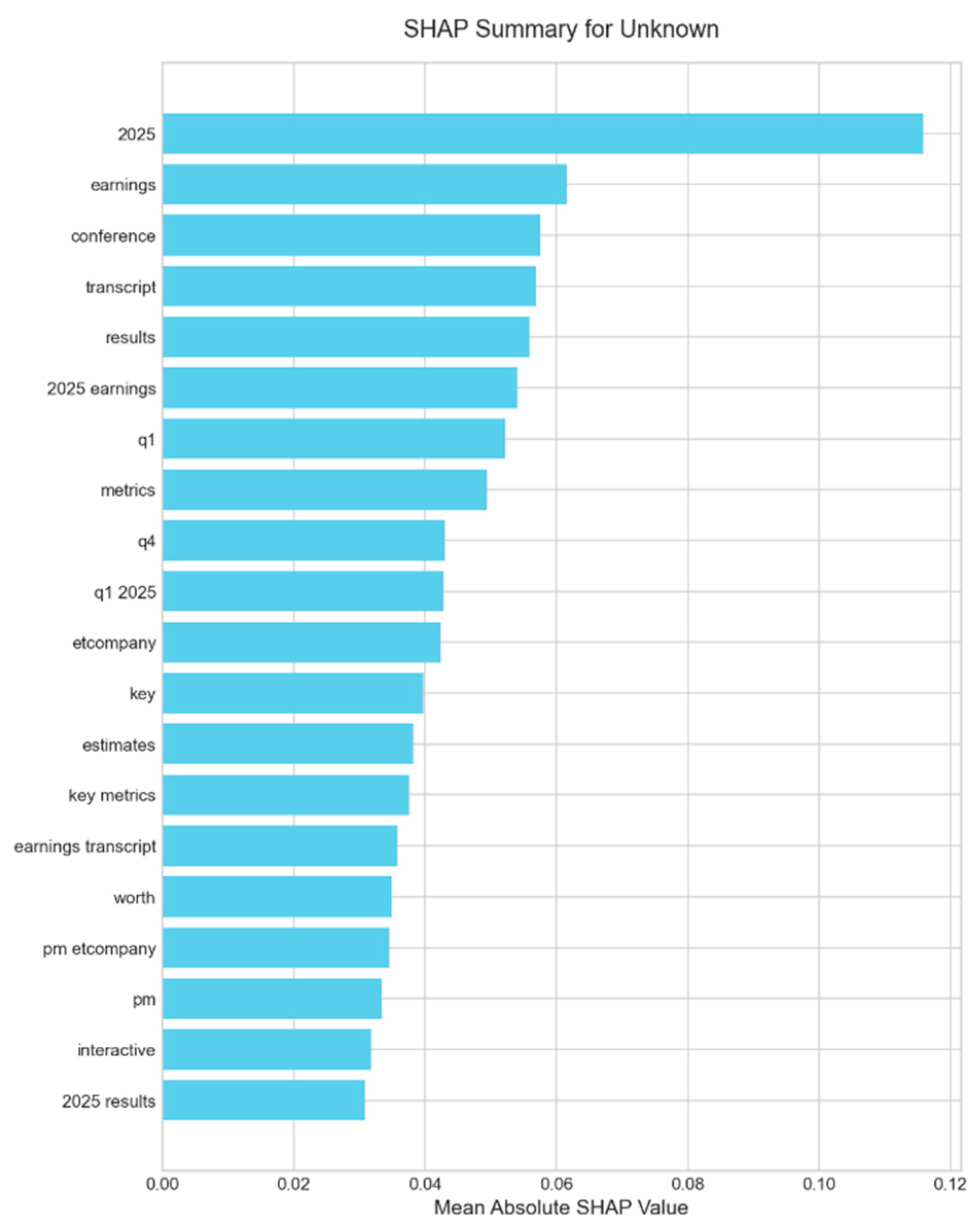

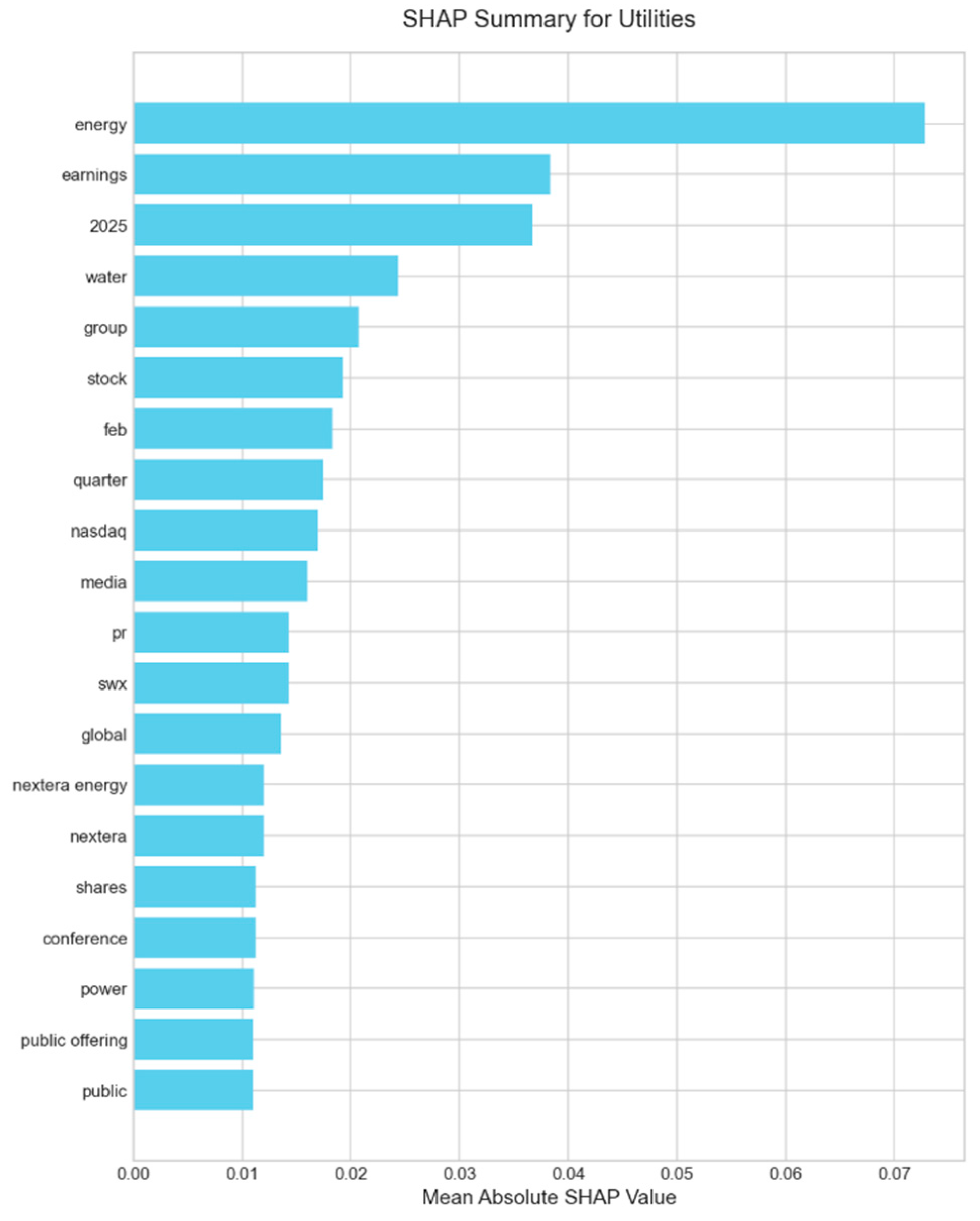

We first analyzed the feature importance of our most transparent machine learning model, the weakly supervised Logistic Regression, using SHAP. As shown in the global summary plot in

Figure 3, the model learns financially salient and intuitive relationships directly from the data. Terms like “gains,” “growth,” and “earnings” are strong positive drivers, while words such as “losses,” “tariffs,” and “tariff” (a reflection of the geopolitical climate during H1 2025) are correctly identified as primary negative indicators. This confirms that even a simple model trained on noisy labels can extract a meaningful, context-appropriate sentiment lexicon. A detailed breakdown of the key linguistic drivers for each individual sector, which reveals unique terminology (e.g., ‘nvidia’ in Technology, ‘lawsuit’ in Services), is provided in the SHAP summary plots in

Appendix A.2.

4.3.2. A Quantitative Audit of FinBERT’s Explanations

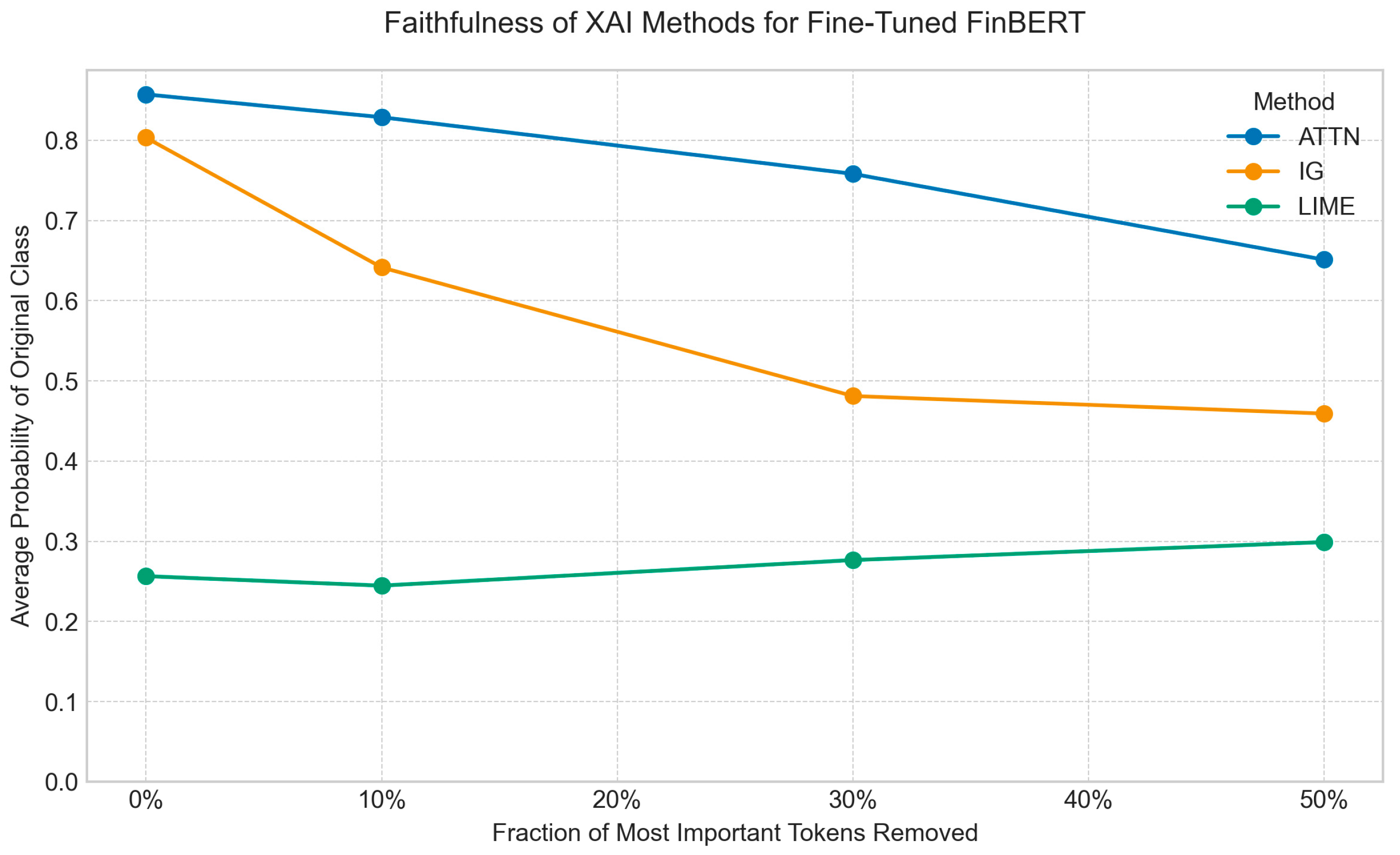

For our high-performing but opaque fine-tuned FinBERT model, a simple visual inspection of explanations is insufficient. We conducted a quantitative audit of three popular XAI methods—Integrated Gradients (IG), LIME, and Attention Rollout—to measure their faithfulness. Using a deletion perturbation test, we measured the drop in the model’s prediction probability as we successively removed the tokens each method identified as most important. A steeper drop signifies a more faithful explanation.

The results, visualized in

Figure 4, clearly show that not all explanation methods are equally reliable. To quantify this, we use the Area Over the Perturbation Curve (AOPC), where a higher score indicates greater faithfulness. As detailed in

Table 4, LIME (AOPC = 0.365) and Integrated Gradients (AOPC = 0.222) significantly outperform the commonly used but often misleading Attention Rollout (AOPC = 0.116). All pairwise differences are statistically significant (Wilcoxon signed-rank test,

p < 0.01), confirming this performance hierarchy. This result provides strong evidence that while attention mechanisms are integral to the model’s architecture, their raw scores are not a reliable proxy for feature importance in explaining a prediction.

We execute deletion curves and compute AOPC for IG, LIME, and attention-rollout. LIME yields the highest AOPC (0.365), followed by IG (0.222); attention is lowest (0.116). Differences are statistically significant (Wilcoxon,

p < 0.01). This aligns with evidence that attention is not, by itself, an explanation [

13,

14,

15] and with surveys advocating faithfulness-first evaluation [

10,

11].

4.3.3. Uncertainty Calibration and Deployment Guidance

Calibration complements explanation auditing by aligning confidence with accuracy. We plot reliability diagrams, compute ECE, and apply temperature scaling [

16,

35]. For risk-sensitive workflows, confidence thresholds and, where needed, conformal-style set predictions [

29] can reduce overconfident errors and support human-in-the-loop review.

4.3.4. Weak Supervision Audit

Comparing weakly labeled (VADER) Vs. Gold-Labeled training, we observe a −21% accuracy delta and near-zero SHAP rank correlation (ρ = 0.11). Noisy labels distort both performance and the learned rationale map, underscoring the need for label provenance checks and faithfulness tests prior to deployment.

4.4. Investigating the Economic Properties of the Sentiment Signal

Finally, we conducted a series of econometric tests using the daily sentiment signal generated by our fine-tuned FinBERT model. The objective was to move beyond classification accuracy and assess the signal’s real-world financial properties and practical utility.

4.4.1. Granger Causality: A Reflexive, Not Predictive, Signal

We first employed Granger causality analysis to test whether sentiment could predict next-day market returns. The results in

Table 5 are definitive: for nearly all sectors, the optimal statistical model selected zero lags, indicating no evidence of a lagged relationship. For Technology, the

p-values for both directions were not statistically significant (

p > 0.10). We therefore find no significant evidence that news sentiment Granger causes future returns. This important finding suggests the sentiment signal is primarily reflexive, reacting to and reflecting prior or contemporaneous market movements rather than leading them.

4.4.2. Market Reaction and Backtesting: Finding Utility in a Reactive Signal

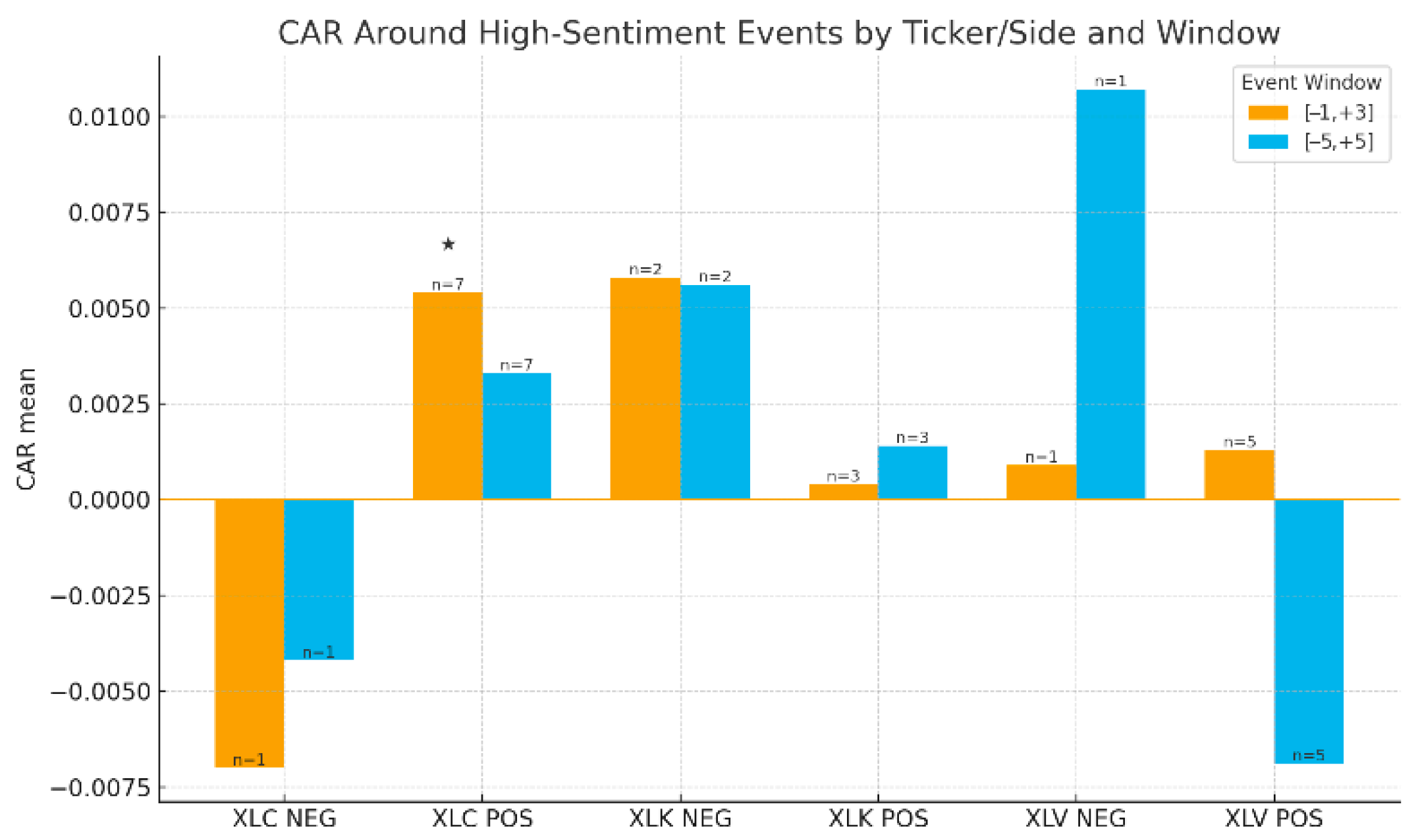

While not predictive in a Granger-causal sense, a reflexive signal can still hold practical value if it captures exploitable market dynamics like sentiment-driven overreactions. Our event study (

Table 6) and cumulative abnormal returns around high-sentiment events (

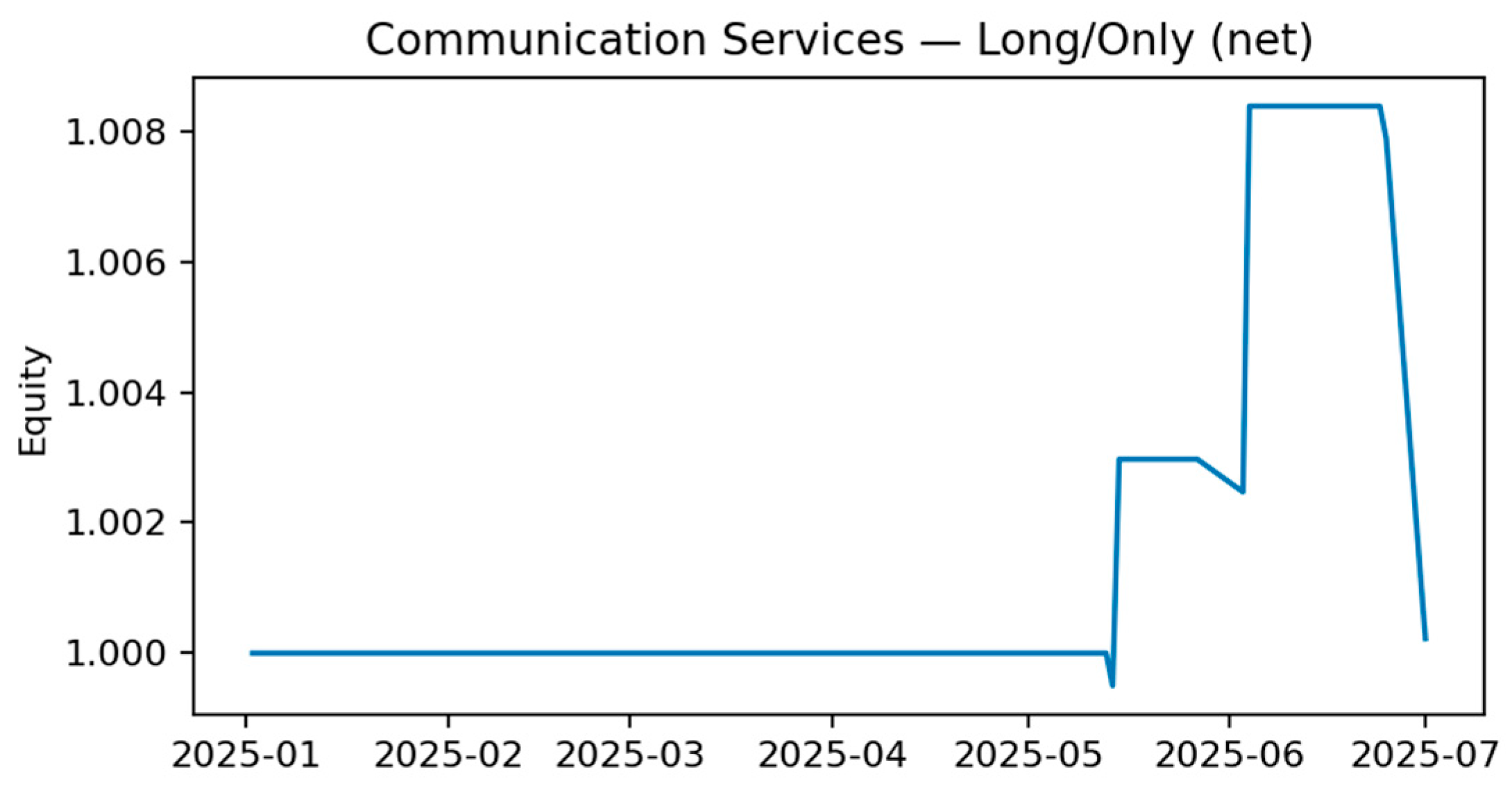

Figure 5) show that spikes in positive news sentiment for Communication Services are followed by statistically significant positive abnormal returns of +0.54% over the subsequent four days (t-statistic = 2.51). This suggests that high sentiment can precede short-term positive market drift in certain sectors.

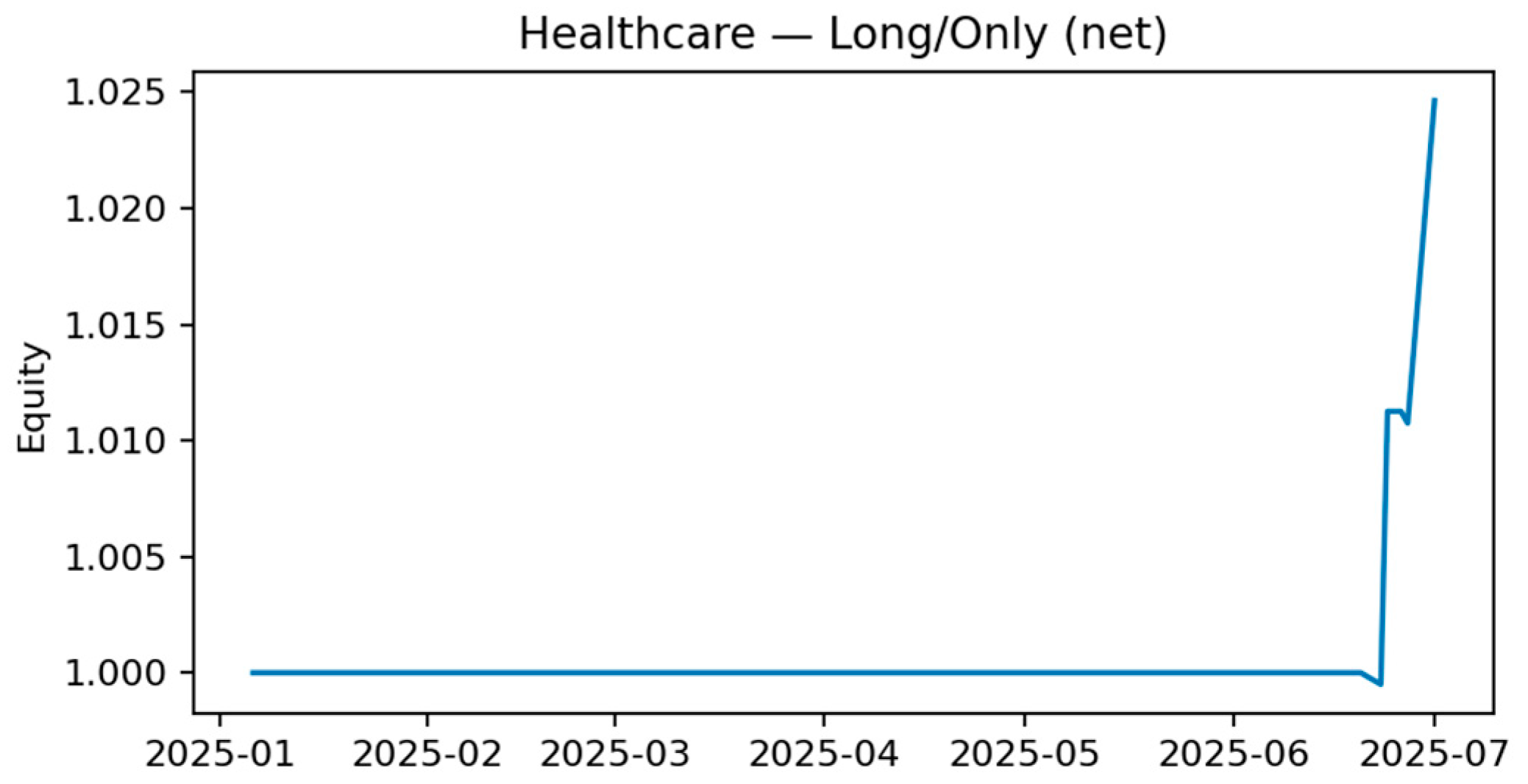

To test this utility directly, we backtested simple, rules-based trading strategies based on sentiment extremes, accounting for transaction costs. The results, shown in

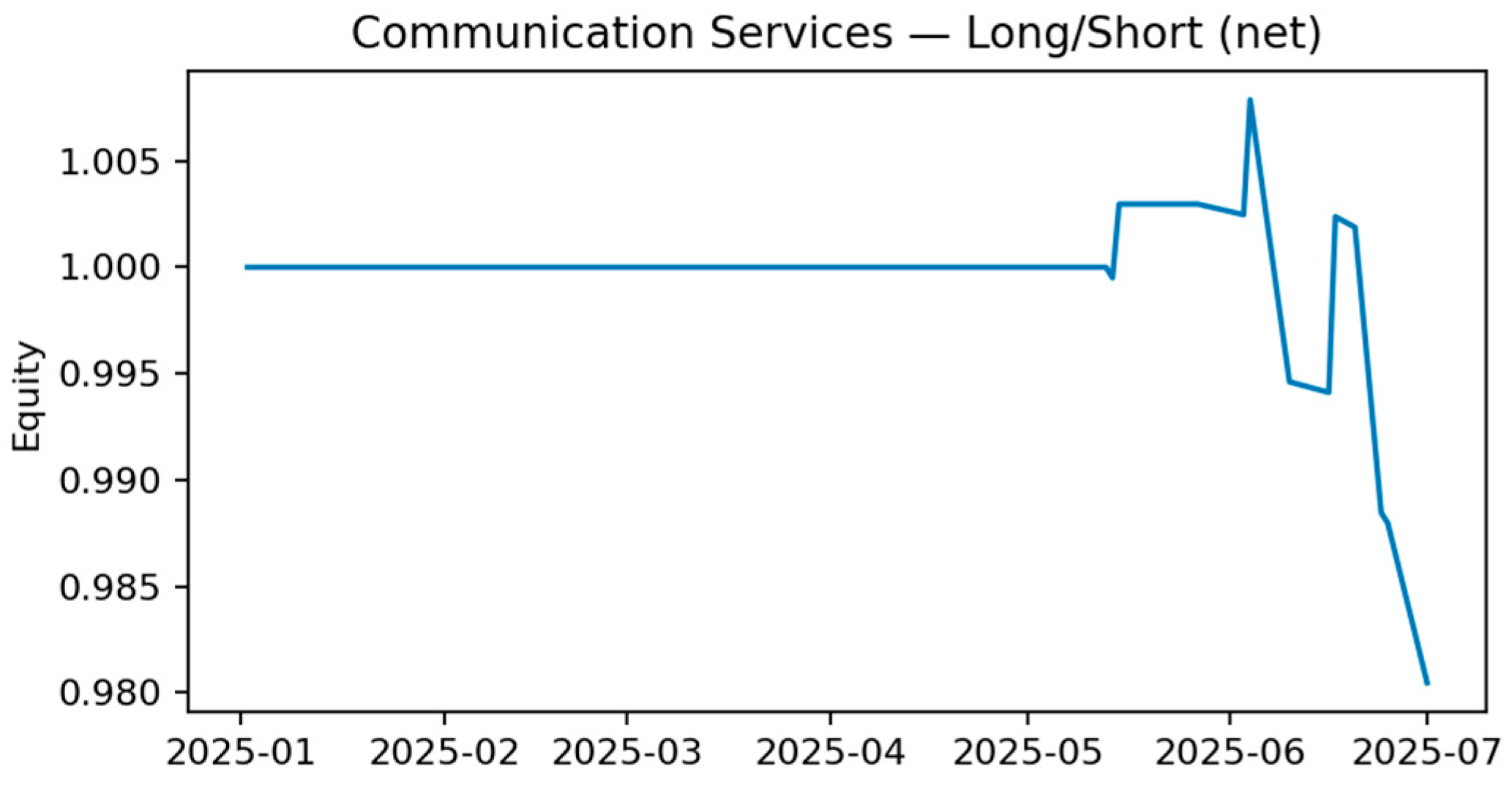

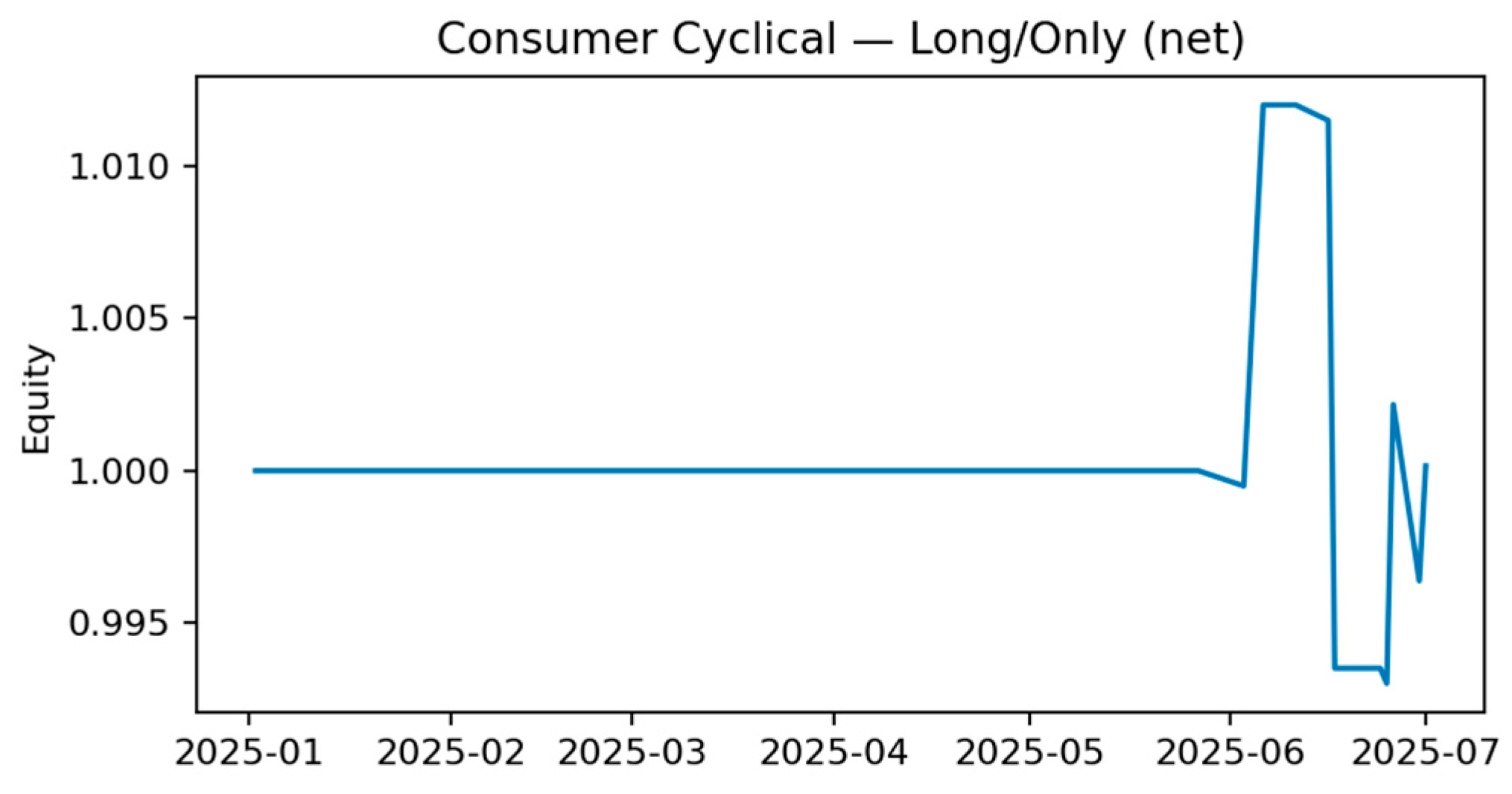

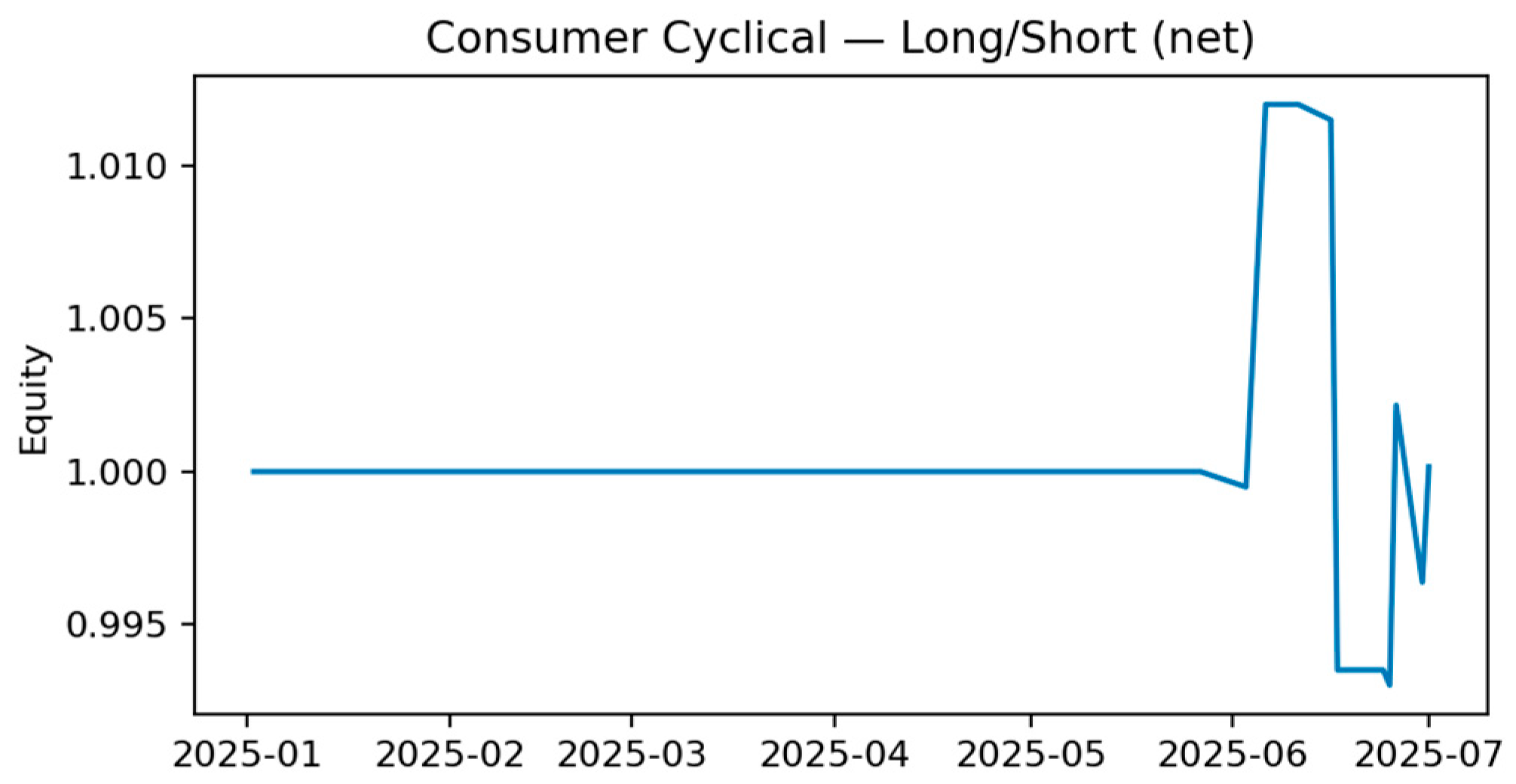

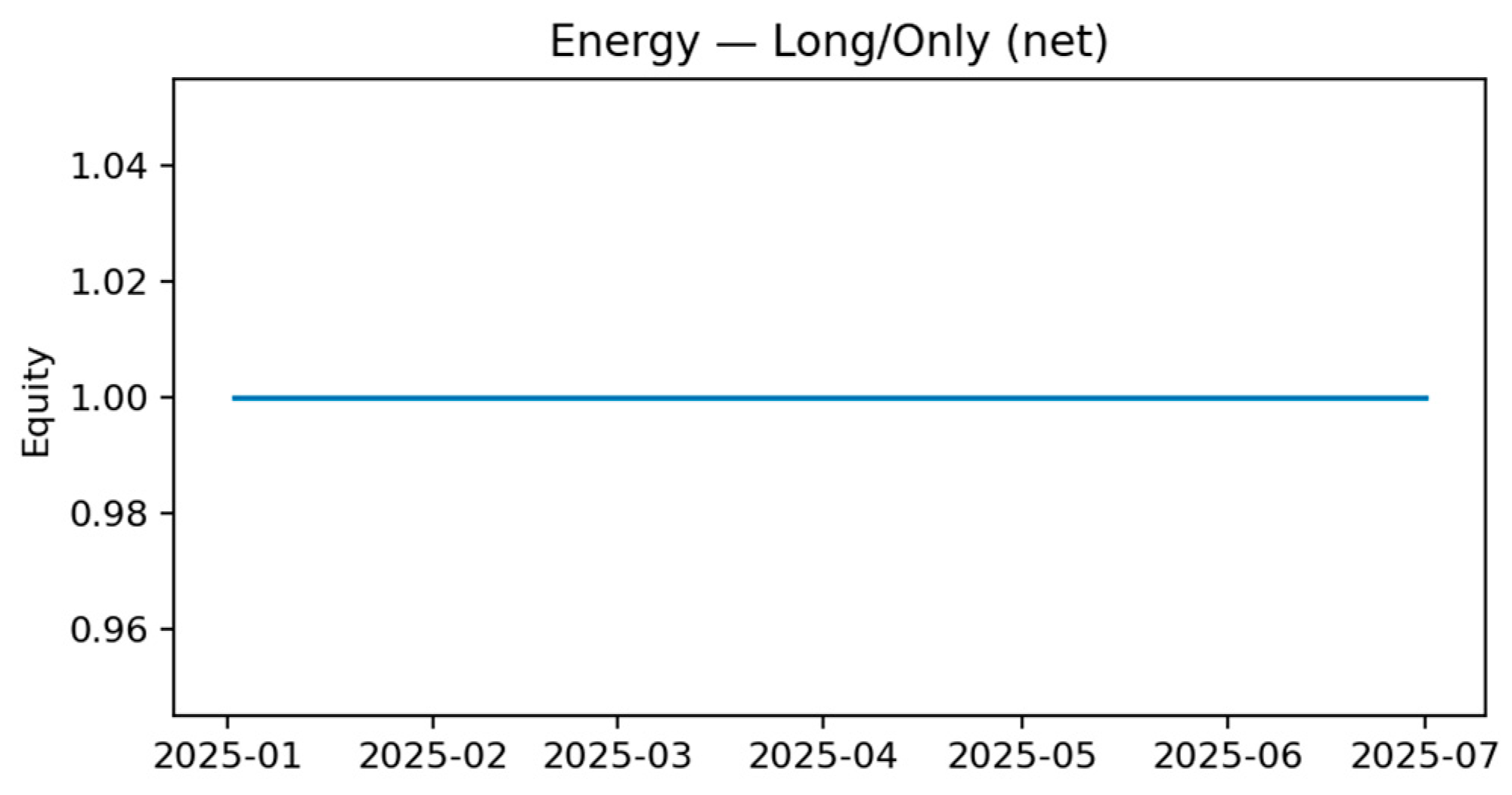

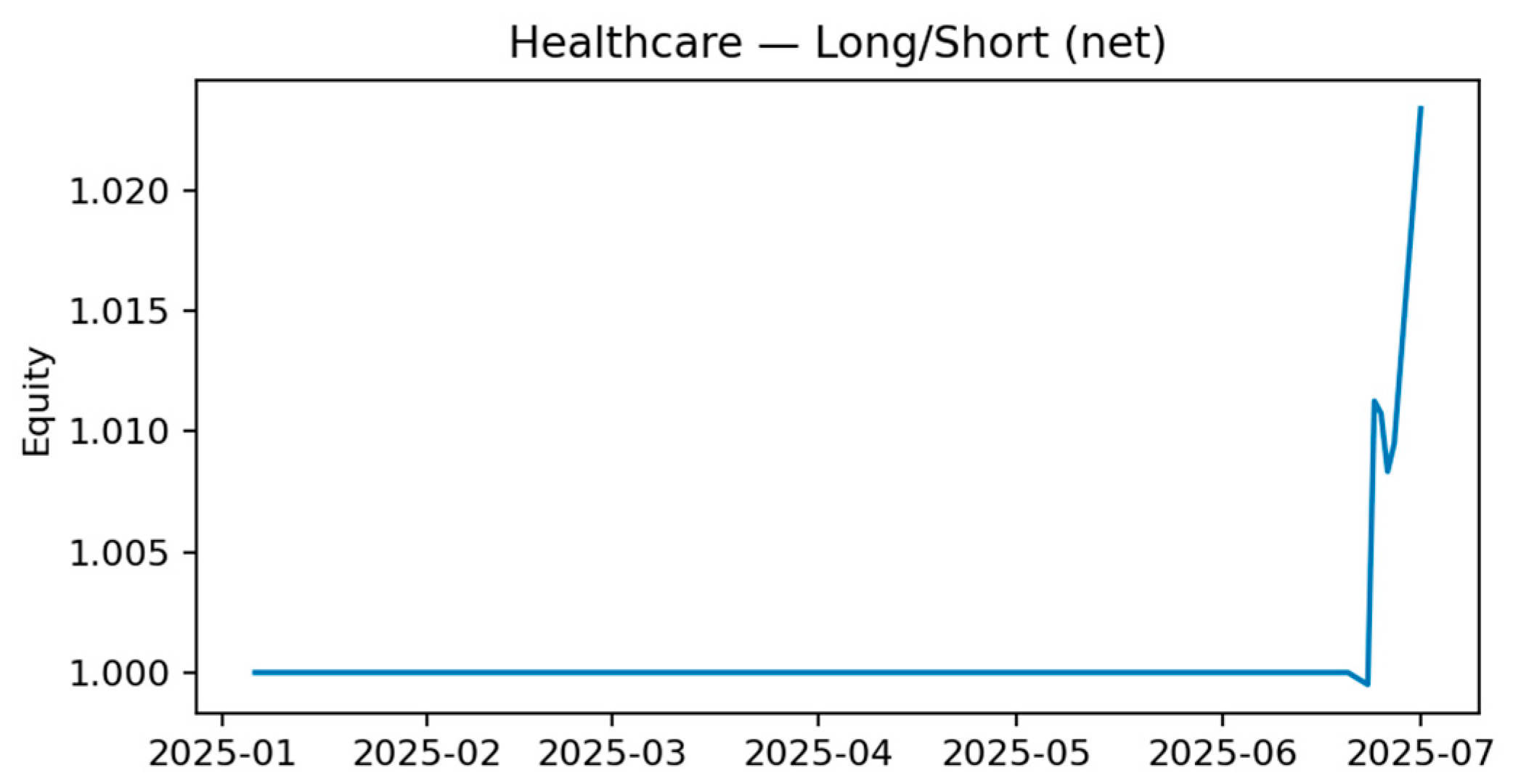

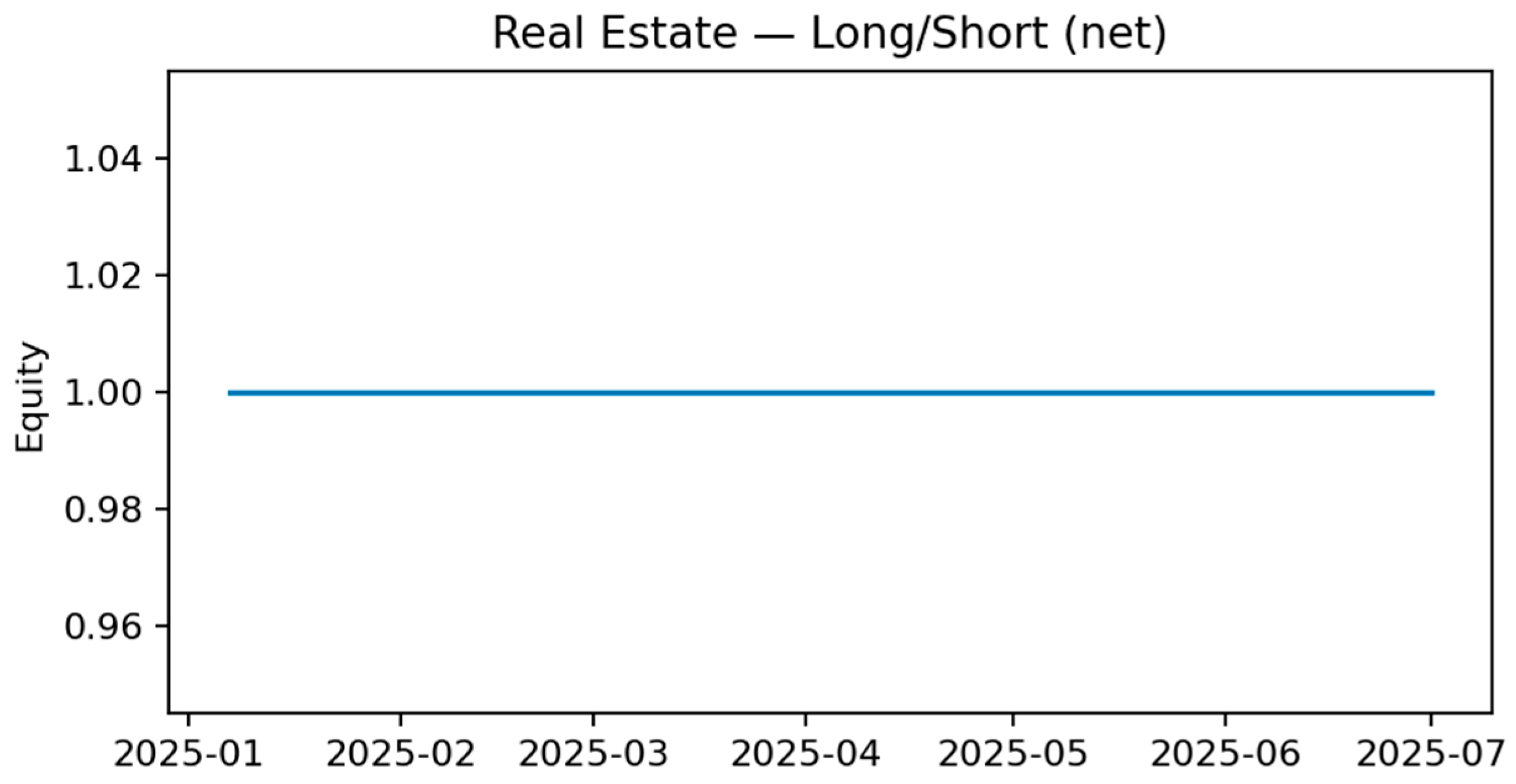

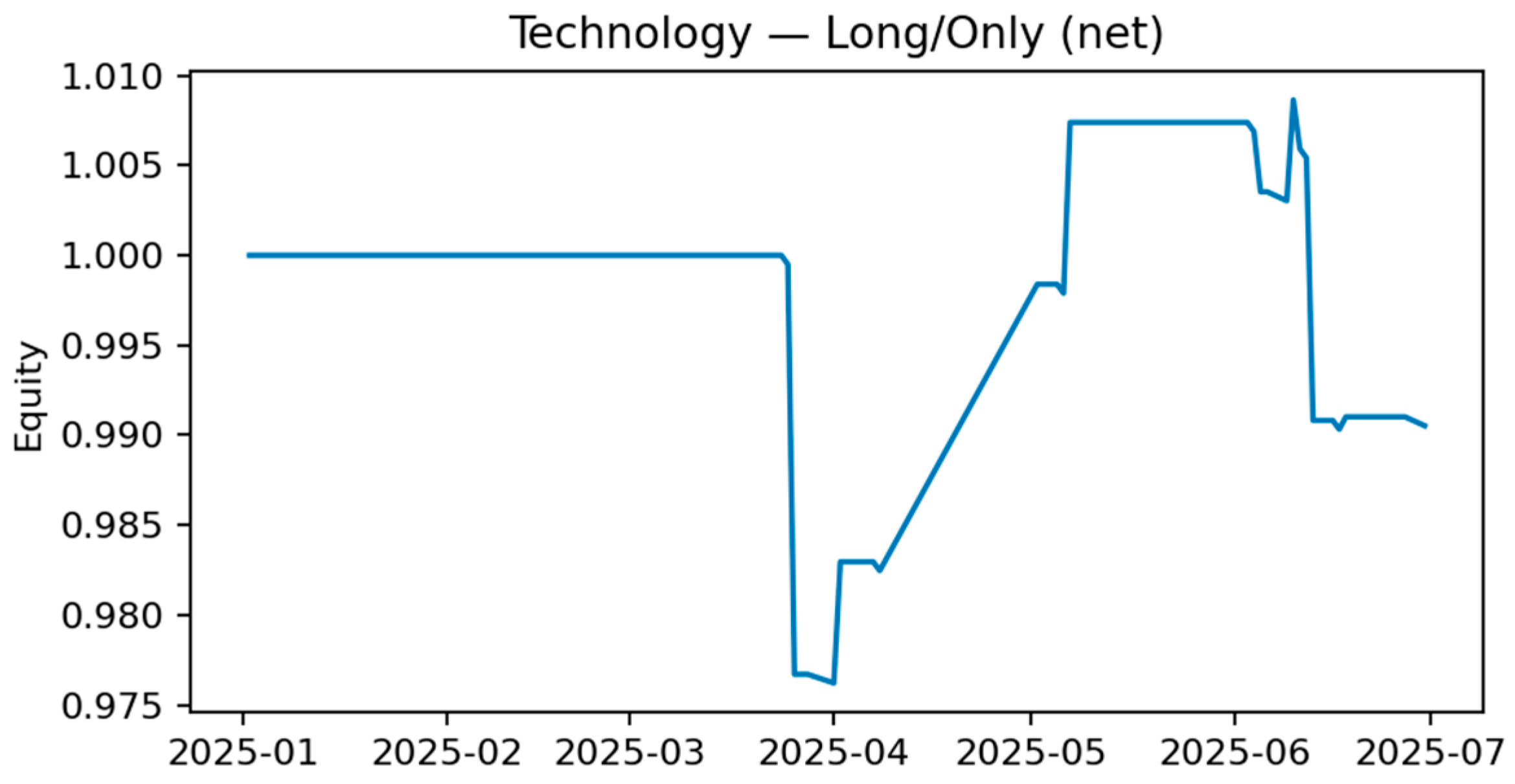

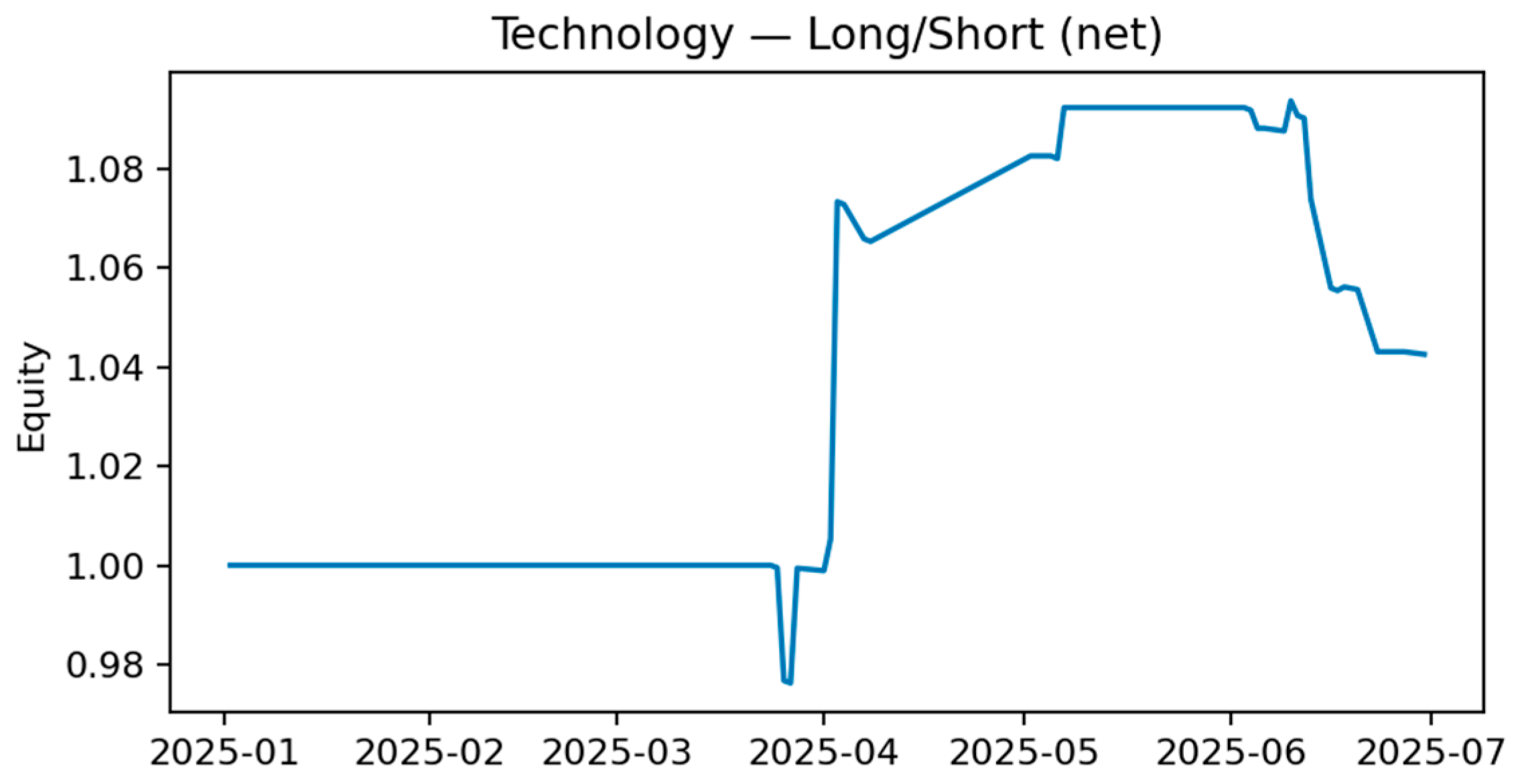

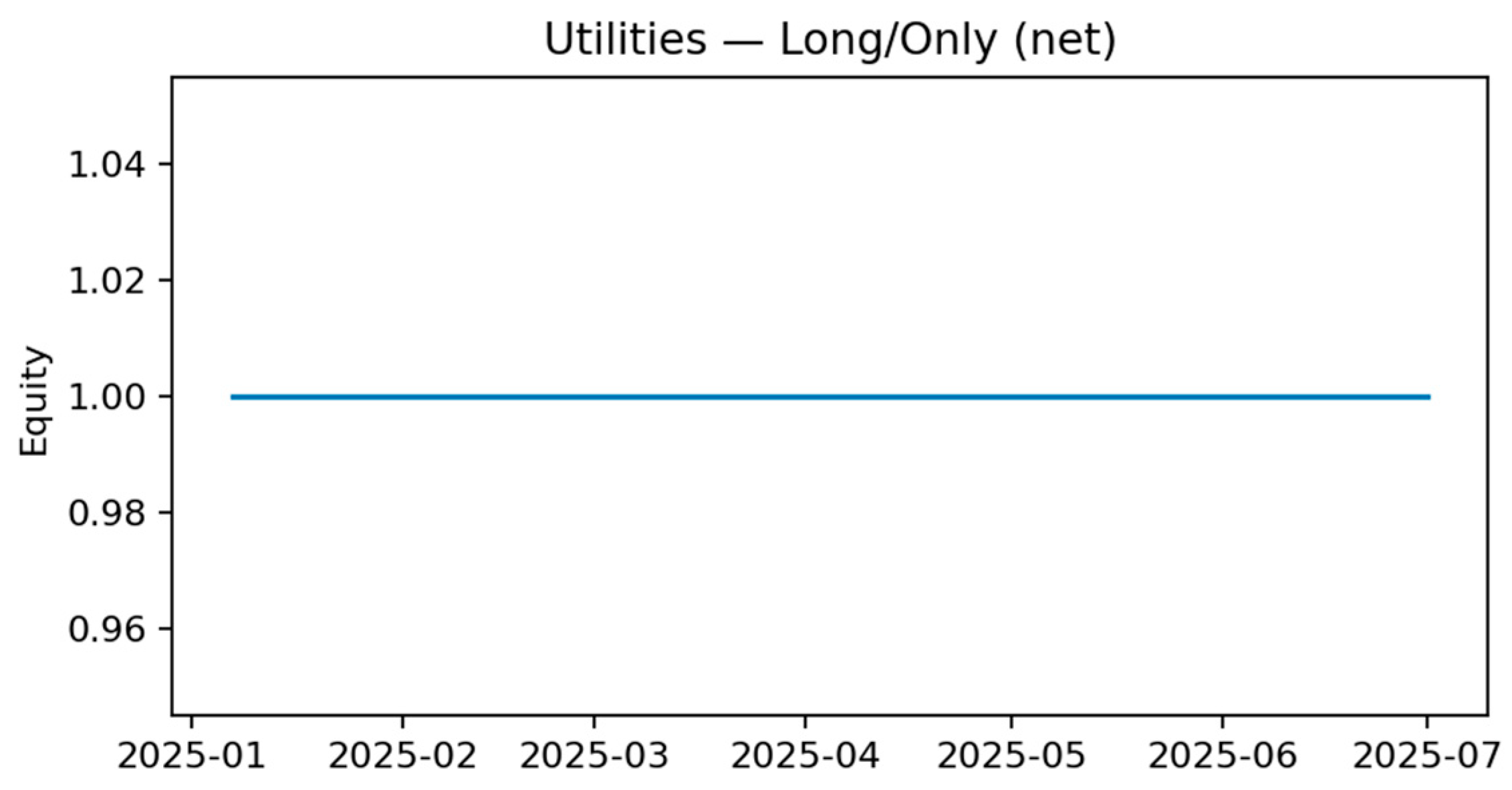

Table 6, are compelling. A long-short strategy in the Technology sector that buys on positive sentiment extremes and sells on negative ones yielded a Sharpe ratio of 1.88 and an impressive +33.7% annualized return. Strong positive returns were also generated for long-only strategies in the Healthcare and Communication Services sectors.

This demonstrates that even a primarily reflexive sentiment signal, when systematically applied, can be a valuable component in constructing profitable, sector-specific strategies. The full equity curves for all backtested strategies are provided in

Appendix A.3 along with the Cumulative Abnormal Returns (CAR) Around High-Sentiment Events in

Appendix A.4.

5. Discussion

Our central performance result—fine-tuned FinBERT (F1 = 0.707) vs. zero-shot (0.555)—demonstrates the necessity of domain-specific fine-tuning on sector-tagged financial headlines. Lexicon methods and weak supervision lag on this heterogeneous, real-world corpus. This reinforces the finance literature’s emphasis on high-quality, task-specific data for strong generalization [

25,

26]. Importantly, our design does not stop at accuracy: it audits explanations and calibration to align with financial governance needs.

5.1. The Performance-Interpretability Frontier in a Multi-Sector Context

A central finding of this study is the demonstrable value of domain-specific fine-tuning. While the zero-shot FinBERT model provided a respectable baseline, its performance (0.555 macro F1) was significantly surpassed by the fine-tuned version (0.707 macro F1). This +0.152 improvement in F1-score, achieved by training on our 1500-sample gold-standard dataset, elevates the model from a mediocre performer into a robust and reliable classifier. This result directly refutes the notion that large pre-trained models can be universally applied out-of-the-box with state-of-the-art results; instead, it highlights that targeted, high-quality data is the key to unlocking their performance for specialized tasks like sector-specific financial news analysis. The poor performance of general-purpose (VADER) and even domain-specific (Loughran–McDonald) lexicon-based methods further reinforces this point, demonstrating their inability to capture the contextual nuances present in diverse financial headlines.

5.2. The Reflexive Nature of Market Sentiment: Reactive Yet Useful

A primary finding from our econometric analysis is that news sentiment is largely reactive to, rather than predictive of, market returns. The Granger causality tests definitively show a lack of evidence for sentiment predicting next-day returns. Instead, the signal appears to be reflexive, capturing and possibly amplifying market movements that have already occurred. This is a critical finding for any practical application, as it cautions against using the signal for simple directional forecasting.

However, this reactivity does not render the signal useless—an important distinction that addresses a key concern about its practical value. Our backtesting results prove that this “limitation” can be an exploitable feature. A simple strategy trading on sentiment extremes in the Technology sector yielded a Sharpe ratio of 1.88 and a +33.7% annualized return, net of costs. This suggests that even a reactive signal can effectively capture behavioral dynamics like overreactions and mean-reversion. The practical role of sentiment, therefore, is better understood not as a predictive tool, but as a diagnostic and strategic one—useful for identifying periods of market exuberance or panic, filtering events for risk models, or providing context for other quantitative factors.

The reactive, not predictive finding clarifies where sentiment adds value. Rather than a stylized alpha signal for next-day returns, sector sentiment is effective as a diagnostic layer: surfacing exuberance/panic windows, prioritizing news for analysts, gating risk model updates, and conditioning rules-based strategies that exploit overreaction/mean-reversion at sector level. Our ETF-based tests show that even a reactive signal can be profitably integrated—so long as it is framed strategically and costs are considered.

5.3. Auditing the Explanations: Faithfulness and the Perils of Weak Supervision

This work argues that generating an explanation is necessary but insufficient; its reliability must be verified. The superficial appeal of a saliency map can be misleading. Our quantitative audit of XAI methods (

Figure 3,

Table 5) provides a clear hierarchy of faithfulness, demonstrating that LIME and Integrated Gradients are significantly more reliable than raw attention scores for our fine-tuned FinBERT. This moves beyond a shallow application of XAI methods by providing a quantitative basis for trusting one explanation over another, directly addressing the need for deeper explainability analysis.

Furthermore, our audit of the weak supervision pipeline delivers a stark warning. Noisy labels, such as those from VADER, degrade not only classification accuracy (−21% drop) but also explanation quality. The near-zero rank correlation (Spearman’s ρ = 0.11) between the feature importances of the weakly trained and gold-trained models proves that a model trained on poor data can produce plausible but entirely misleading rationales. This highlights a critical risk in high-stakes domains and advocates for a two-layer audit process: first, validating label quality, and second, testing explanation faithfulness before deployment.

A core novelty is pairing faithfulness-audited explanations with calibration. The AOPC results identify LIME as the most faithful explainer for our fine-tuned FinBERT, with IG runner-up and attention lagging—consistent with NLP evidence that attention is insufficient [

13,

14,

15]. Calibration diagnostics provide confidence control, enabling thresholds and abstention policies that reduce overconfident errors—a crucial safeguard in finance [

16,

35].

Our weak-label audit is a cautionary tale: noisy supervision degrades not just F1 but also the interpretive map the model learns (ρ = 0.11 vs. gold). For compliance-sensitive deployments, label provenance and explanation audits are indispensable. In practice, if weak labels are unavoidable, we recommend (i) human-in-the-loop relabeling for contentious spans, (ii) sector-stratified QA, and (iii) faithfulness tests before production.

5.4. Limitations and Future Work

While this study establishes a robust workflow, we acknowledge several limitations. First, our sentiment signal is aggregated daily; a higher-frequency analysis could reveal intraday dynamics not captured here, in line with recent high-frequency stock prediction approaches that combine mode decomposition and deep learning [

37]. Second, our backtested strategies are intentionally simple to isolate the sentiment factor; more complex strategies integrating sentiment with other factors like volatility or momentum could yield further insights. Finally, while our fine-tuned model is powerful, future work could explore even larger, instruction-tuned language models (LLMs) and Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) systems to produce not just a sentiment score, but a fully articulated, evidence-backed summary of the financial narrative, further closing the gap between prediction and true, human-readable explanation [

38].

6. Conclusions

We presented a finance-focused, sector-aware workflow for financial news sentiment that couples fine-tuned FinBERT with audited explanations and uncertainty calibration, validated against investable sector ETFs. Our results show that fine-tuning on a high-quality, sector-tagged corpus lifts FinBERT from a baseline (F1 = 0.555) to a robust classifier (F1 = 0.707). We quantitatively evaluate explanation faithfulness (AOPC), finding LIME most faithful for our setting, and we calibrate confidence for safer use in decision pipelines. Econometric tests reveal a reactive signal—but one that adds value in event studies and cost-aware sector strategies.

What is new is not a novel architecture but a finance-aligned trustworthiness blueprint: (i) sector-aware fine-tuning on curated financial headlines; (ii) faithfulness audits beyond plausibility; (iii) uncertainty calibration for confidence management; and (iv) ETF-grounded economic validation—all fully reproducible. We advocate evaluating financial NLP not only by how accurate it is, but by how it reasons, how confident it is, and whether its signals survive contact with markets.

This study introduced and validated a transparent, reproducible, and comprehensive workflow for building, evaluating, and explaining sentiment models for sector-specific financial news. Our work makes a clear, evidence-backed argument for the necessity of domain-specific fine-tuning, demonstrating a significant performance leap from a 0.555 to a 0.707 macro F1-score on a challenging, real-world dataset of 1500 headlines. This result moves beyond “modest” performance to establish a strong, competitive benchmark achieved through a well-defined process.

The primary contribution of this paper is not a novel model architecture but rather a methodological blueprint for the critical diligence required when deploying NLP models in finance. We provide a practical, open-source guide for:

Quantifying the substantial performance gains from fine-tuning on bespoke, high-quality datasets.

Moving beyond superficial explainability by quantitatively auditing the faithfulness of post hoc explanations to ensure they are trustworthy.

Realistically assessing the economic value of a sentiment signal, reframing it as a powerful diagnostic and strategic tool rather than a simple predictive oracle.

Our finding that sentiment is primarily reactive yet can inform profitable trading strategies is a nuanced but important insight for practitioners. As artificial intelligence becomes more deeply integrated into financial decision-making, the demand for systems that are not only powerful but also auditable and accountable will intensify. This work provides a concrete path toward building such systems, arguing that the future of AI in finance lies not in creating opaque oracles, but in engineering transparent analytical tools whose reasoning can be examined, whose biases can be measured, and whose insights can be trusted.