4.2. CEEMDAN-IWT Denoising Results and Discussion

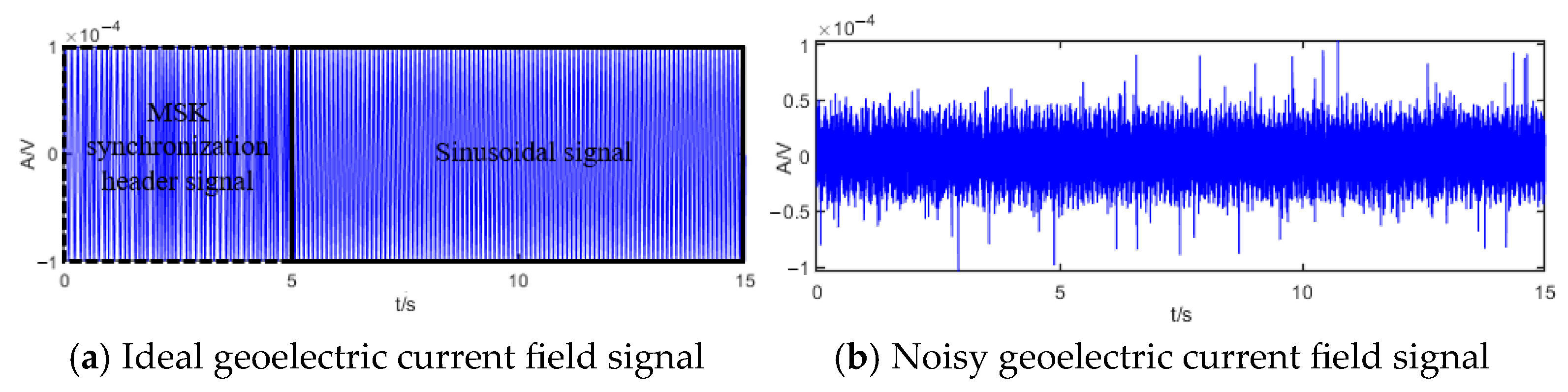

First, the injected geoelectric current field signal needs to be decomposed using CEEMDAN. Considering both accuracy and efficiency, the specific parameters for the CEEMDAN denoising algorithm in this study, obtained through multiple experiments, are as follows: the noise standard deviation is 0.2, the number of noise additions is 100, and the maximum number of iterations is 1000. The signal is decomposed into 13 intrinsic mode functions (IMFs), as shown in

Figure 5.

There are significant differences in the noise levels of different intrinsic mode functions (IMFs), and the reasonable setting of threshold parameters directly affects the IMF component selection effect. A threshold that is too low may result in the residual noise-dominated modes, while a threshold that is too high may lead to the loss of valid components. This paper references the work of Peng et al. [

31] and adopts the IMF component selection criterion based on the

, setting the threshold to ≤0.01. When

≤ 0.01, the IMF component carries less than 1% of the original signal information and mainly reflects the random fluctuation characteristics of the noise. This judgment does not depend on the specific type of the signal but is based on the inherent difference in variance contribution between noise and valid signals. Furthermore,

is a dimensionless parameter that is unaffected by the absolute strength of the signal and can adapt to original signal scenarios with different amplitudes. At the same time, the ensemble averaging strategy of CEEMDAN has already preliminarily reduced the interference of noise in the decomposition results, and the thresholding of

can further precisely remove residual minor noise. Compared to other parameter selection criteria, it demonstrates stronger robustness to scene changes.

Figure 6 shows the variance contribution rate calculation results for the 13 IMF decomposition components. According to the calculation results, the variance contribution rates of IMF7–IMF13 are all ≤0.01 and are removed. The total variance contribution rate of the selected IMF components is 0.9749, indicating that IMF1–IMF6 have completed the preliminary denoising while largely preserving the geoelectric current field signal characteristics.

To achieve optimal denoising performance, this paper uses the signal-to-noise ratio (

) as a quantitative evaluation metric to assess the denoising effect. When calculating the

, the first step is to perform a sliding correlation calculation between the denoised signal and the

synchronization header template signal, as shown in Equation (14). The sampling point that maximizes the sliding correlation coefficient is identified. The

synchronization header lasts for 5 s, and starting from the end of the synchronization header, a 10 s signal is extracted as the valid window. The valid signal segment within this window is used for the

calculation, effectively excluding the transient interference from the

synchronization header.

where

represents the denoised signal,

is the

synchronization header signal, and

has

sampling points,

is the

-th sliding correlation coefficient.

The expression for the signal-to-noise ratio is:

where

is the power of the useful signal, and

is the power of the noise,

is the sampled value of the pure signal,

is the sampled value of the denoised signal,

is the index of the starting sampling point of the valid window,

is the number of sampling points in the valid window.

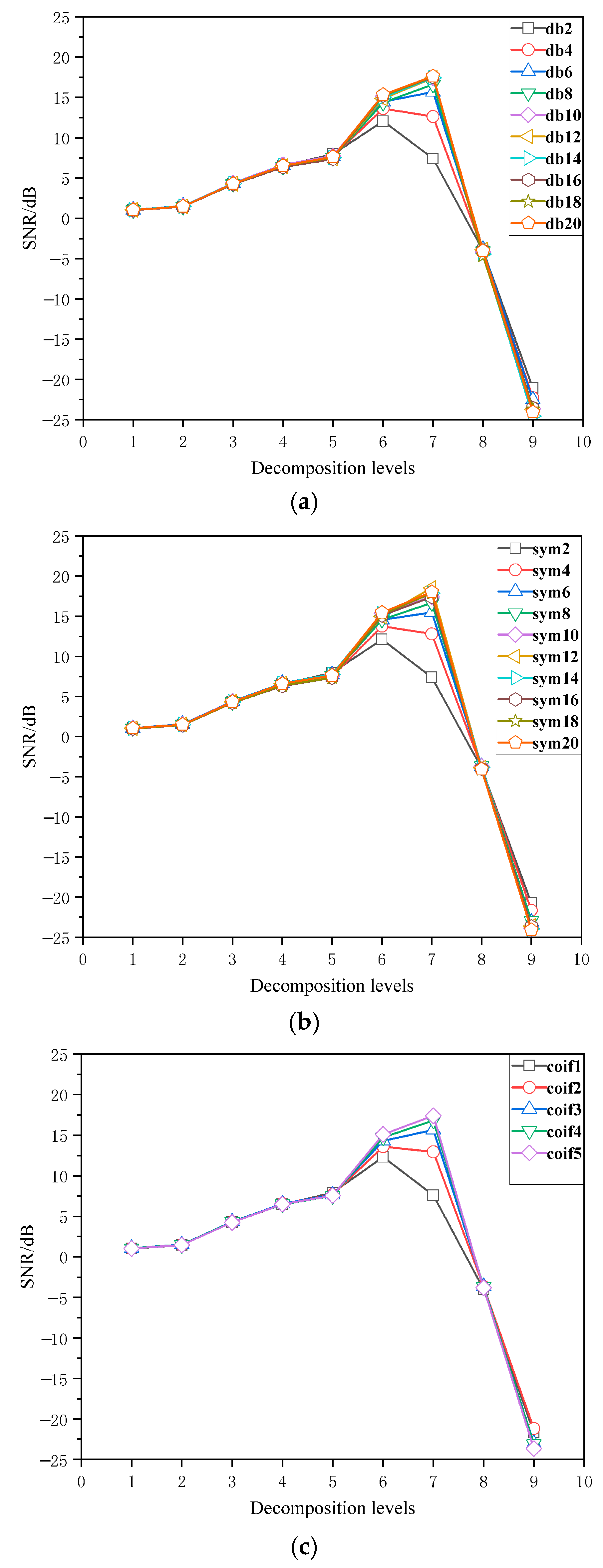

Experiments on denoising of geoelectric current field signals were conducted for different wavelet basis functions and decomposition layer combinations to select the optimal wavelet parameter combination. The experimental results indicate that the signal-to-noise ratio reaches its maximum value of 18.65 dB when the sym12 wavelet basis is used with 7 decomposition layers, as shown in

Figure 7. Based on this, the sym12 wavelet basis and 7-layer decomposition are determined as the optimal parameter combination to ensure the best denoising effect

To verify the rationality of the “

≤ 0.01” IMF filtering threshold proposed in this study and evaluate its impact on the denoising effect, a sensitivity analysis was conducted. In the simulation scenario with an initial

of −5 dB, thresholds of 0.005, 0.01, and 0.02 were set. The performance differences were quantified by comparing the denoised signal’s signal-to-noise ratio (

) and normalized cross-correlation (

). The results are shown in

Table 1, and the expression for the

is given in Equation (16).

The above results indicate that when the threshold is set to 0.01, both the and reach their highest levels, achieving the best denoising effect. When the threshold is set to 0.005, the selection criterion is too loose, which leads to the residual presence of some noise-dominant IMF components due to insufficient filtering. Although a small amount of noise is suppressed, the proportion of residual noise increases, resulting in a decrease in both and . On the other hand, when the threshold is raised to 0.02, the filtering becomes too strict, leading to excessive elimination of IMF components and thus causing the loss of effective signal, which results in the lowest and values. In conclusion, the effective energy of the injected electric field signal is mainly concentrated in a few mid-to-high frequency IMF components, while the variance contribution of the noise components is generally low. The threshold of 0.01 effectively removes most noise components without excessively losing the effective signal, achieving an optimal balance between noise suppression and signal fidelity.

To preliminarily verify the denoising effect of the proposed method, a visual analysis is first conducted through waveform comparison. The proposed method is compared with wavelet hard thresholding, soft thresholding, Improvement thresholding, CEEMDAN-hard thresholding, and CEEMDAN-soft thresholding, with a focus on the ability of each method to restore details at characteristic points. The denoising effect comparisons are shown in

Figure 8a–f. The figure also presents a waveform comparison between the ideal current field signal and the denoised signal in the 9–11 s time interval, along with local enlarged details at three key characteristic positions to highlight the detail retention of different methods.

The experimental results show that all six denoising methods effectively eliminate most of the noise in the simulated noisy geoelectric current field signal. However, the CEEMDAN-IWT method proposed in this study demonstrates a significant advantage in detail preservation: As seen from the detail comparisons in the local zoomed-in regions A, B, and C, this method not only removes the noise but also preserves the waveform characteristics and the amplitude-phase relationships of the original signal to a greater extent. In contrast, when using hard threshold wavelet or soft threshold wavelet individually, the signal details deviate significantly, and the denoising effect is poorer. Although the other methods can also effectively denoise, they still exhibit some minor deviations. The experimental results validate the synergistic improvement effect of the CEEMDAN-IWT method in adaptive noise separation and weak signal fidelity.

The waveform comparison above preliminarily demonstrates the advantage of the proposed method in terms of detail preservation. To further validate the effectiveness and superiority of the proposed method, this study conducts a comprehensive comparison between the proposed method and existing typical denoising methods using the simulated signal dataset with a signal-to-noise ratio of −5 dB synthesized in

Section 4.1 (sampling duration: 15 s). The specific parameter settings are shown in

Table 2.

To objectively quantify the overall performance, the

,

, and root mean square error (

) are selected as evaluation metrics, with the

calculation formula shown in Equation (17). The results are presented in

Table 3. Although learning-based methods have shown strong potential in the field of signal processing, their application in practical geoelectric field detection faces two key challenges: first, these methods typically require a large number of labeled “noise-clean” signal pairs for supervised training, which is difficult to obtain in actual exploration environments where pure reference signals are scarce; second, their decision-making process lacks physical interpretability, making it challenging to meet the need for clear physical mechanisms in the interpretation of geoelectric field data. Therefore, to better align with the requirements of robustness, practicality, and transparency of mechanisms in geoelectric field detection, this study does not include such methods in the comparative analysis.

According to the results in

Table 3, the CEEMDAN-IWT method significantly outperforms other comparative methods in overall denoising performance. Although traditional time-domain and frequency-domain methods possess some denoising capability, their overall metrics are relatively poor. adaptive filtering achieved

= 9.92 dB,

= 0.8261,

= 0.0211; correlation detection achieved

= 10.35 dB,

= 0.8715,

= 0.0178. This indicates that traditional methods struggle to effectively preserve signal features under strong noise conditions, resulting in noticeable distortion and residual noise. Time–frequency analysis methods perform better overall than traditional methods. Among them, the improved wavelet thresholding (IWT) performs the best, achieving

= 15.02 dB,

= 0.9244,

= 0.0095, surpassing traditional wavelet hard thresholding (

= 12.53 dB) and CEEMDAN-only denoising (

= 12.14 dB), demonstrating the advantage of multi-scale analysis.

The method proposed in this study, through the synergistic effect of CEEMDAN adaptive decomposition and fine denoising via IWT, further optimizes denoising performance, achieving = 18.65 dB, = 0.9611, = 0.0015, and attaining a better balance between noise suppression and signal fidelity.

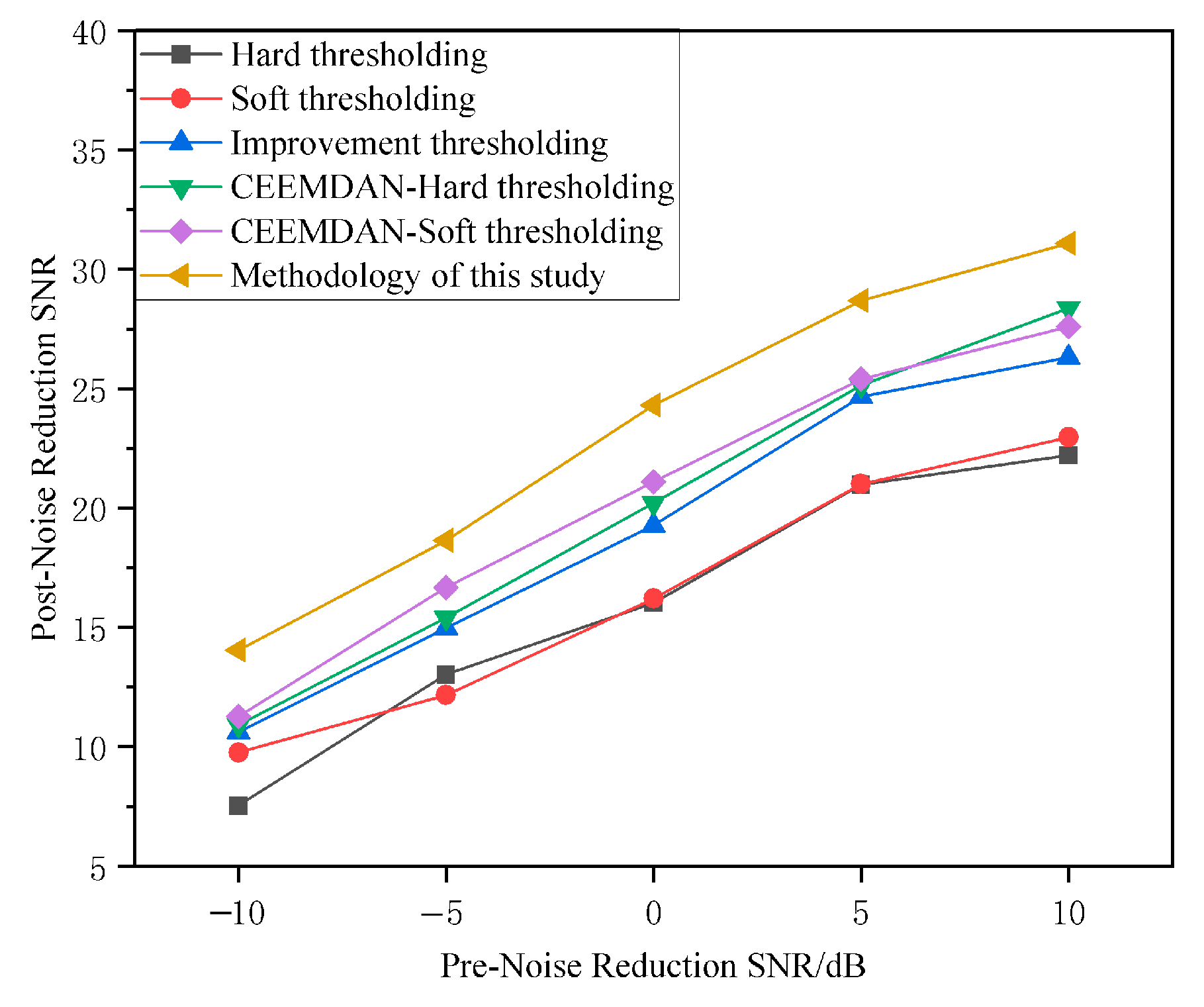

To further explore the denoising performance of the CEEMDAN-IWT method under different noise conditions, denoising analysis was conducted on signals mixed with noise at various

. The experimental results demonstrate that the CEEMDAN-IWT denoising method outperforms the other six methods, significantly improving the

in various noise environments. It effectively separates the characteristic signal and reduces noise interference, enabling more effective signal extraction and noise suppression, thereby significantly enhancing the signal quality, The results are shown in

Figure 9. This validates the strong robustness and adaptability of the method.

The robustness results under different noise intensities have already demonstrated the advantages of the method, but a single experiment may be influenced by the randomness of the noise. To ensure the statistical reliability of the conclusions, 45 independent noise realization experiments were conducted under each

condition to quantify the stability of the results. The output

and

are presented in the form of Mean ± Std, with the results shown in

Table 4.

As the input increases from −10 dB to 10 dB, the output increases from 14.05 dB to 30.85 dB, with the standard deviation remaining ≤ 1.08 dB. The decreases from 0.0049 to 0.0002 as the input improves, with the standard deviation ≤ 0.00043. These results validate the robustness of the method to changes in noise intensity, and the results demonstrate statistical reliability.

To quantitatively evaluate the computational efficiency and resource consumption of the CEEMDAN-IWT method, this study conducted a computational complexity analysis experiment. The running time and memory usage of the method were measured under different signal lengths (N) and ensemble numbers (I), with the results shown in

Table 5.

As can be seen from

Table 5, the runtime of the CEEMDAN-IWT method increases approximately linearly with both signal length (N) and ensemble size (I). Under the same I, when N increases from 1500 to 15,000 (a 10-fold increase), the runtime rises by about 12–14 times; under the same N, when I increases from 50 to 200 (a 4-fold increase), the runtime increases by approximately 3.6–3.9 times. The memory usage shows a moderate upward trend with the growth of N (when N increases 10-fold, memory rises from 865 KB to 3569 KB), but remains basically stable with changes in I, indicating that memory consumption is mainly determined by the signal decomposition scale.

From the perspective of practical application scenarios, this method has certain applicability on embedded platforms under the conditions of medium-length signals (N ≤ 7500) and moderate ensemble sizes (I = 50–100). At this point, the memory requirement is less than 2 MB and the runtime is controlled within 16 s, which can match the resource constraints of portable geoelectric field detection equipment. For scenarios with large N (e.g., 15,000) or large I (e.g., 200), offline processing is recommended to balance performance and resource consumption.

The above research results indicate that the method proposed in this study, through the synergistic effect of CEEMDAN and improved wavelet threshold denoising, not only better preserves the key information of the geoelectric current field signal, preventing the loss of critical information in geological analysis, but also significantly outperforms traditional methods in terms of various precise quantitative indicators and environmental adaptability. This achieves the optimal balance between noise suppression and signal fidelity. Although this method slightly increases the computational load, it significantly enhances signal fidelity and reliability. Its two-level synergistic processing framework minimizes signal distortion and improves processing accuracy, providing high-quality data support for subsequent underground electrical parameter inversion and geological structure analysis.