Dynamic Imprint and Recovery Mechanisms in Hf0.2Zr0.8O2 Anti-Ferroelectric Capacitors with FORC Characterization

Abstract

1. Introduction

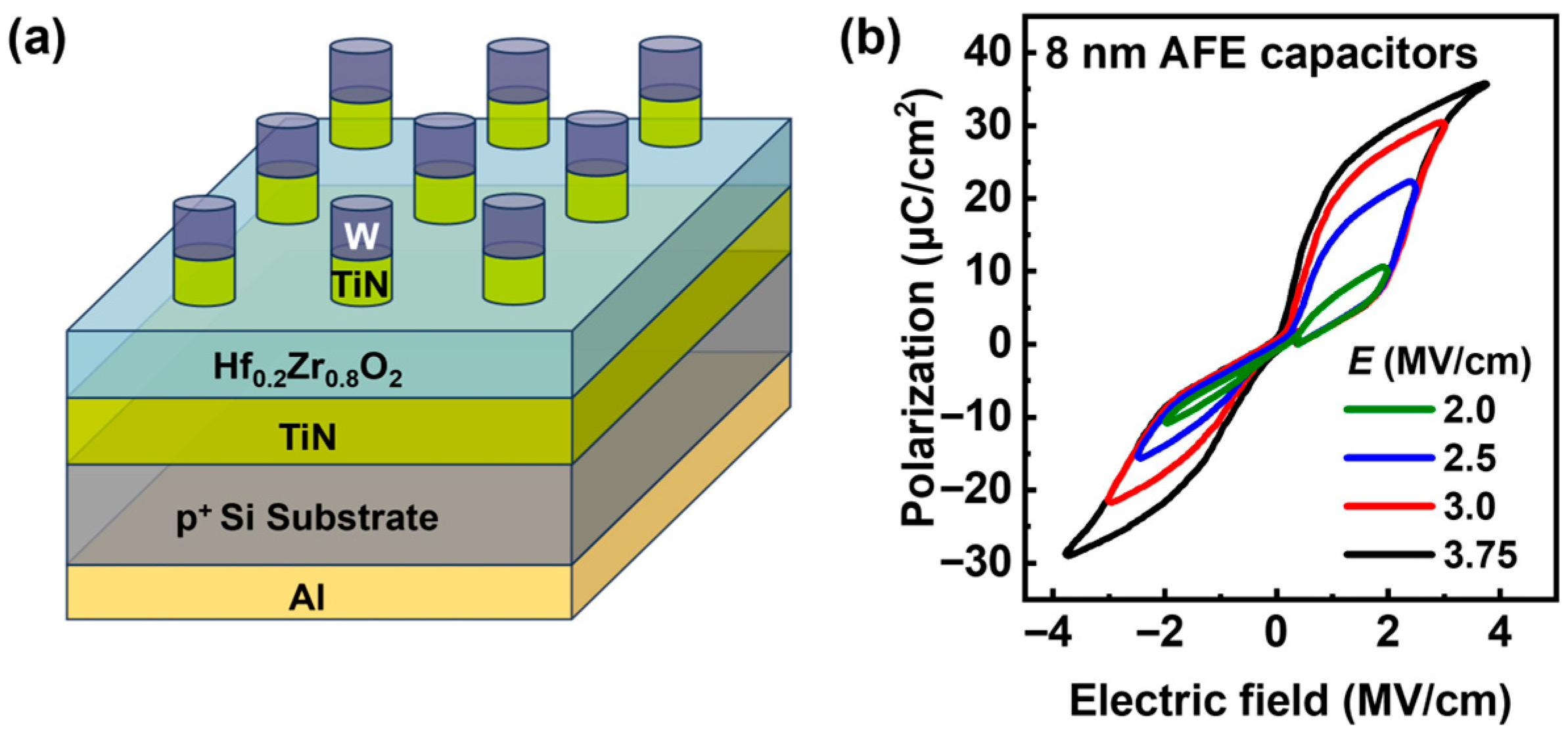

2. Experiments

2.1. Device Processing

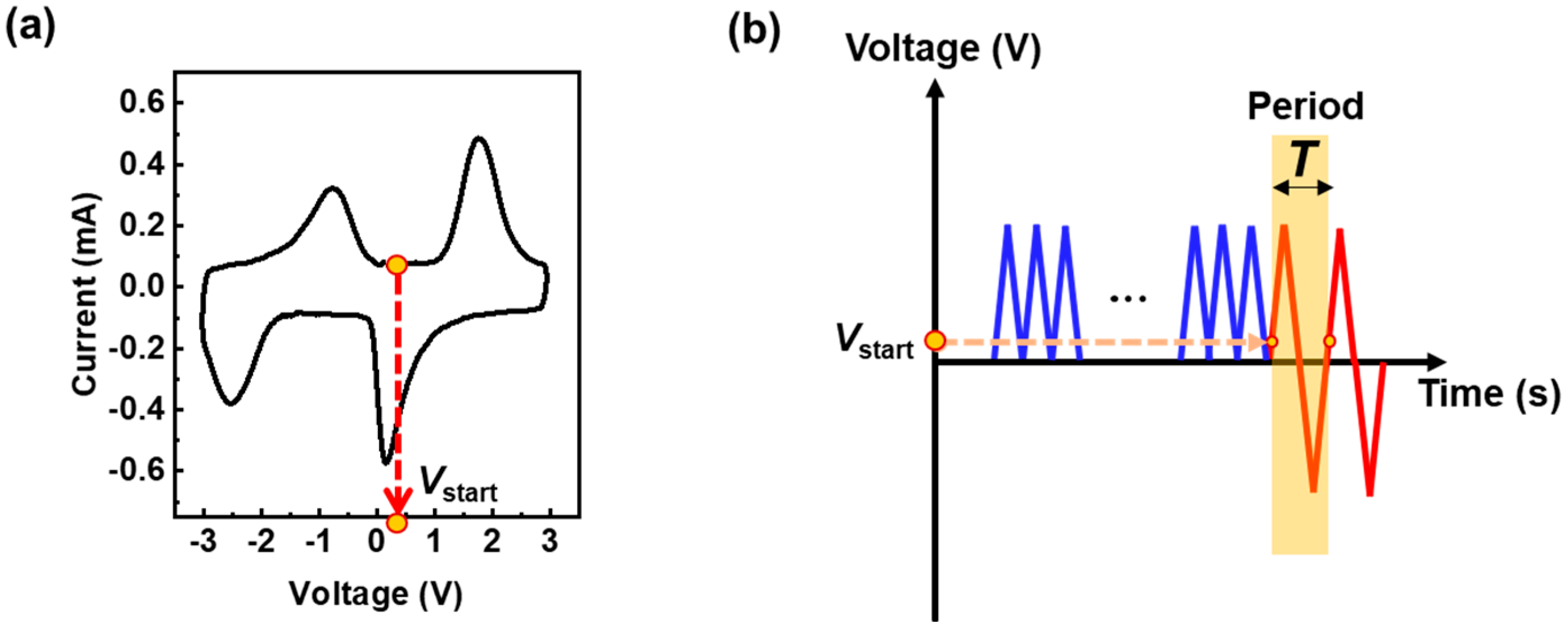

2.2. Characterization Method

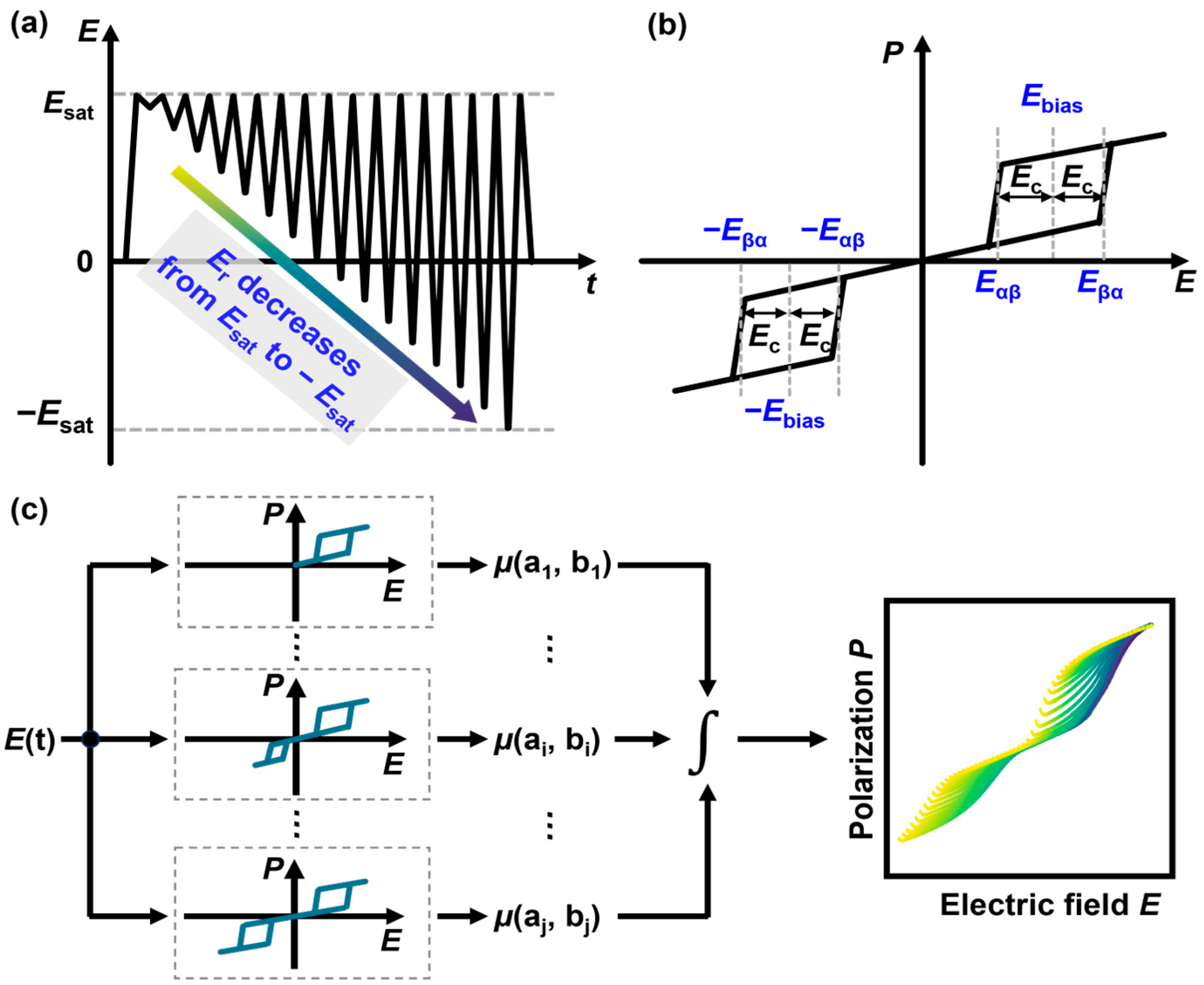

2.3. FORC Characterization

3. Results and Discussion

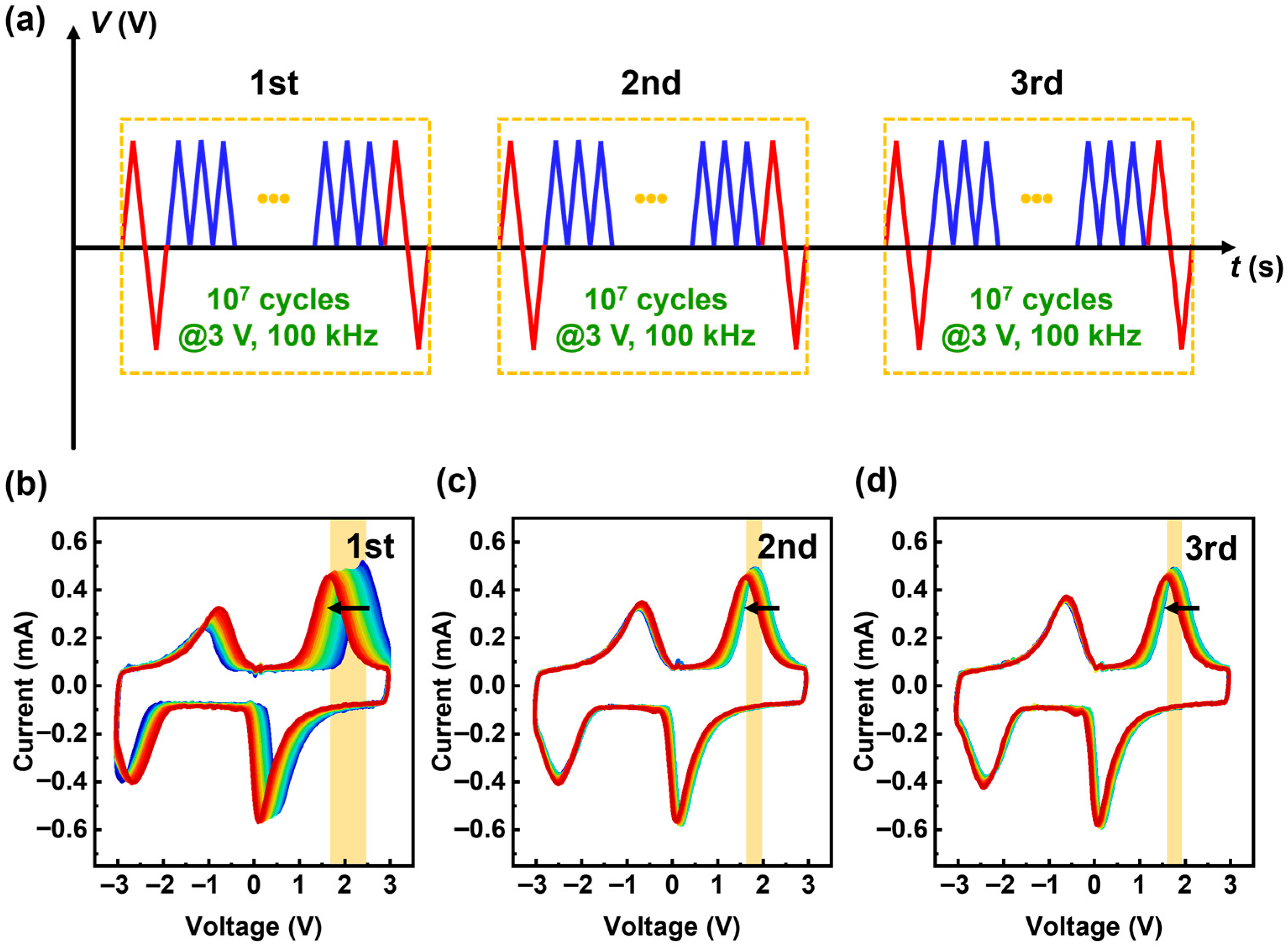

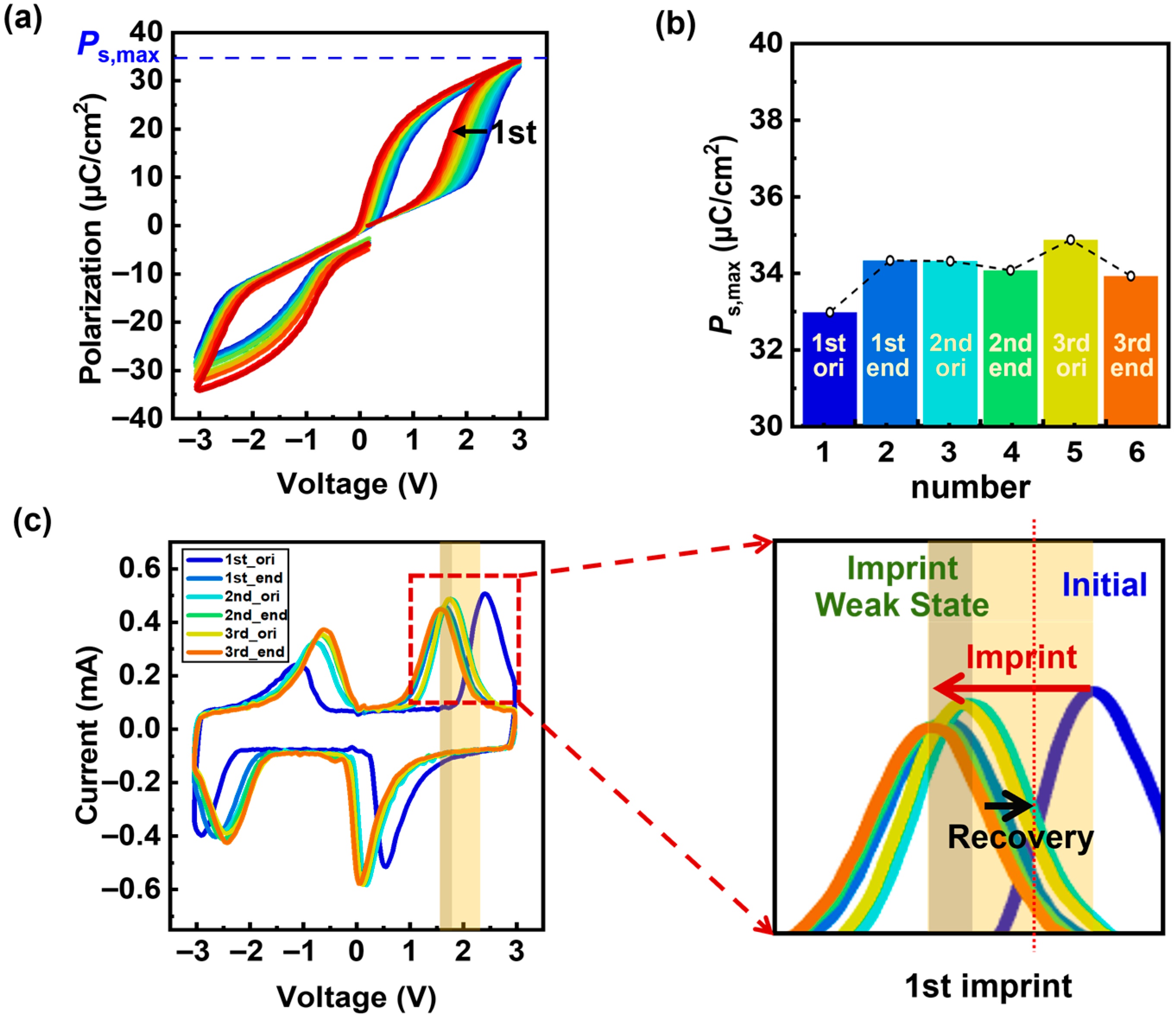

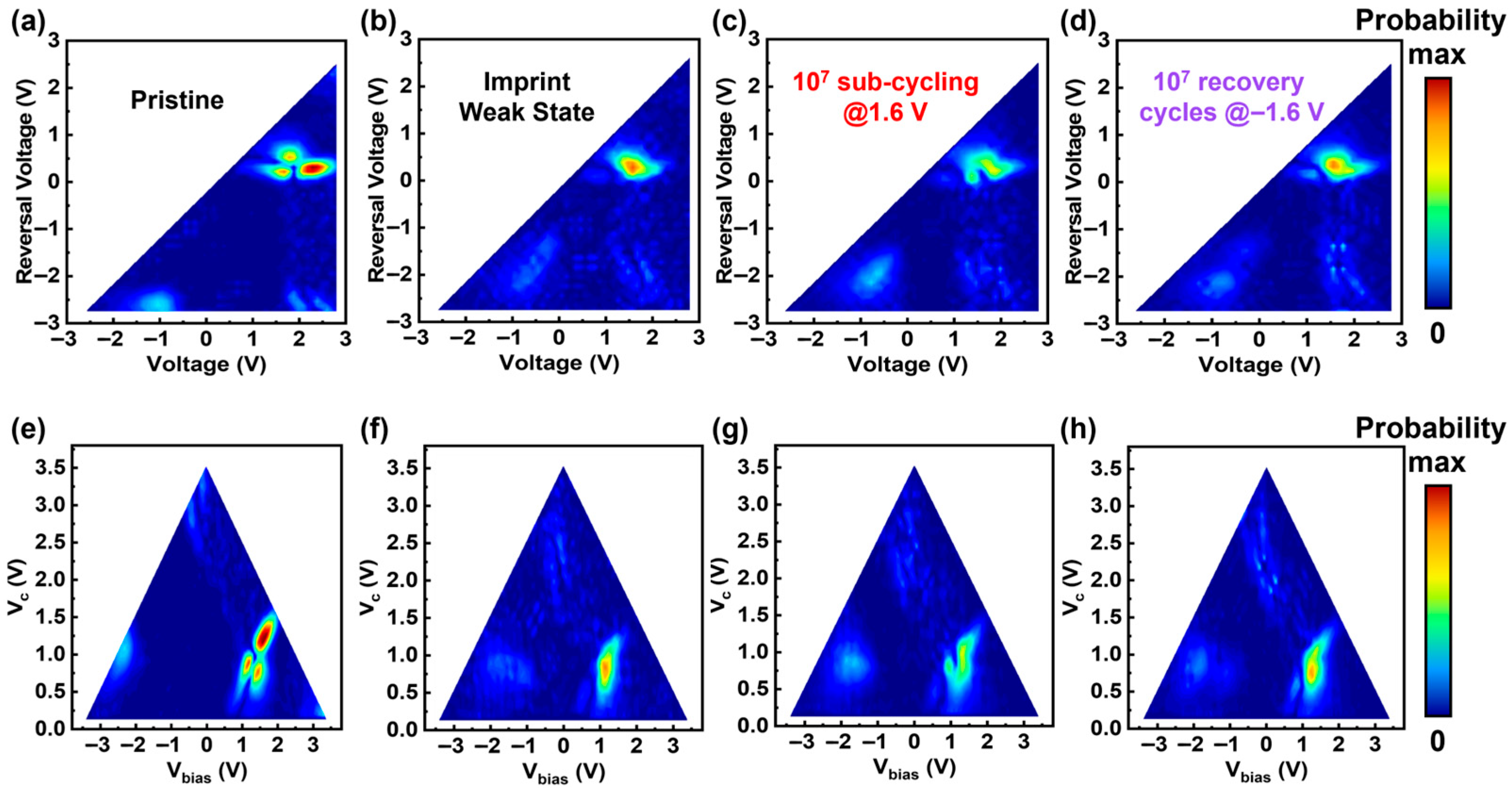

3.1. Variations in Imprint Behaviors

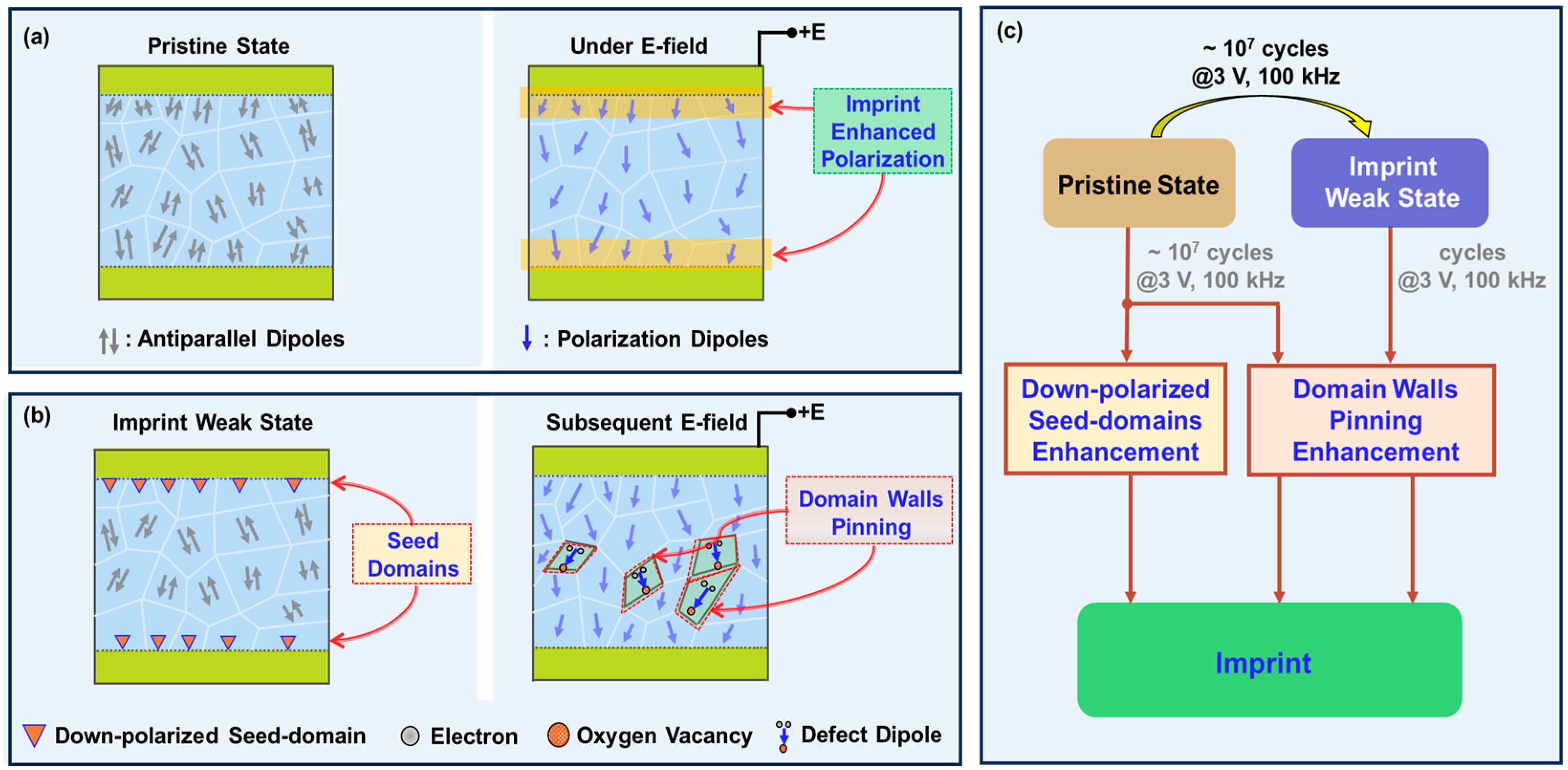

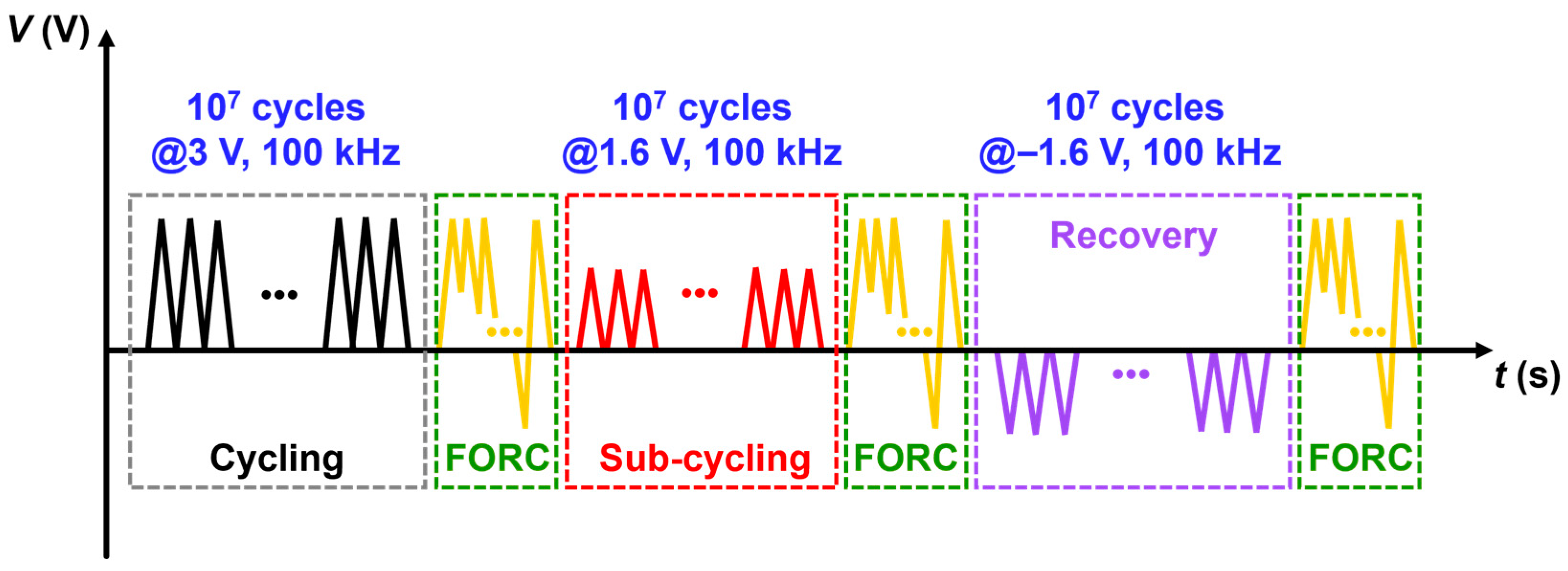

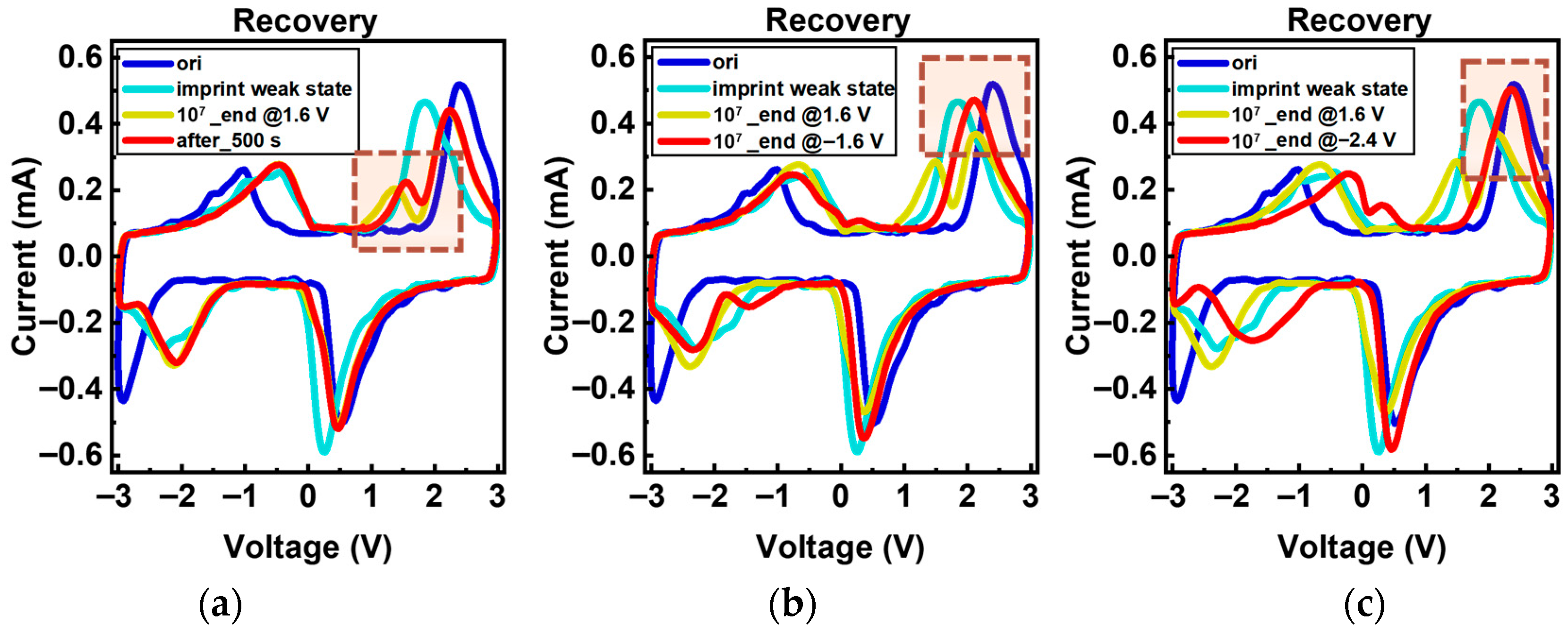

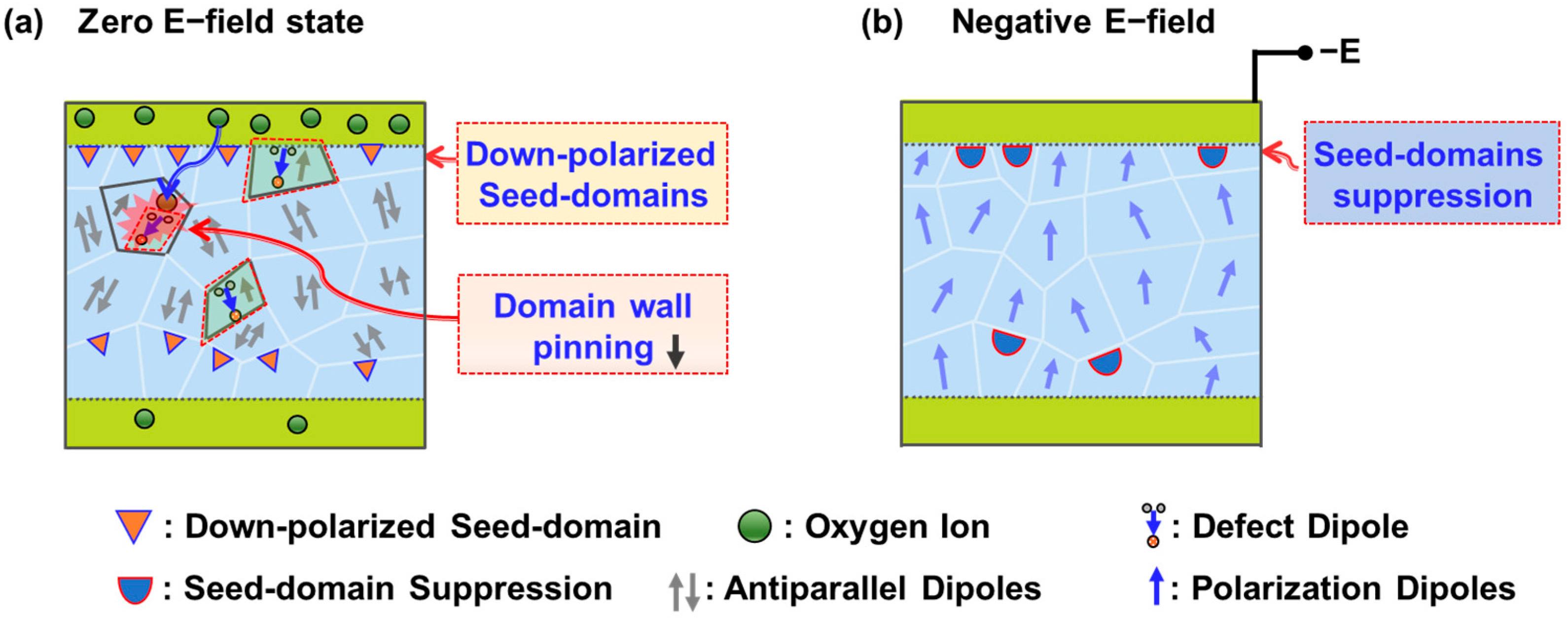

3.2. Imprint Behavior and Recovery Mechanisms

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Vishnumurthy, P.; Alcala, R.; Mikolajick, T.; Schroeder, U.; Antunes, L.A.; Kersch, A. ferroelectric HfO2-based capacitors for FeRAM: Reliability from field cycling endurance to retention (invited). In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE International Reliability Physics Symposium (IRPS), Dallas, TX, USA, 14 April 2024; IEEE: Grapevine, TX, USA, 2024; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Bouaziz, J.; Rojo Romeo, P.; Baboux, N.; Vilquin, B. Imprint issue during retention tests for HfO2-based FRAM: An industrial challenge? Appl. Phys. Lett. 2021, 118, 082901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sünbül, A.; Lehninger, D.; Lederer, M.; Mähne, H.; Hoffmann, R.; Bernert, K.; Thiem, S.; Schöne, F.; Döllgast, M.; Haufe, N.; et al. A study on imprint behavior of ferroelectric hafnium oxide caused by high-temperature annealing. Phys. Status Solidi A 2023, 220, 2300067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulaosmanovic, H.; Lomenzo, P.D.; Schroeder, U.; Slesazeck, S.; Mikolajick, T.; Max, B. Reliability aspects of ferroelectric hafnium oxide for application in non-volatile memories. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE International Reliability Physics Symposium (IRPS), Monterey, CA, USA, 21–24 March 2021; IEEE: Monterey, CA, USA, 2021; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Warren, W.L.; Tuttle, B.A.; Dimos, D.; Pike, G.E.; Al-Shareef, H.N.; Ramesh, R.; Evans, J.T.; Jr, J. Imprint in ferroelectric capacitors. JPN. J. Appl. Phys. 1996, 35, 1521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takada, K.; Takarae, S.; Shimamoto, K.; Fujimura, N.; Yoshimura, T. Time-dependent imprint in Hf0.5Zr0.5O2 ferroelectric thin films. Adv. Electron. Mater. 2021, 7, 2100151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chojecki, P.; Walters, G.; Forrester, Z.; Nishida, T. Preisach modeling of imprint on hafnium zirconium oxide ferroelectric capacitors. J. Appl. Phys. 2021, 130, 094102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhada-Lahbabi, K.; Manchon, B.; Magagnin, G.; Lepri, C.; Gonzalez, S.; Infante, I.C.; Le Berre, M.; Vilquin, B.; Bouaziz, J.; Gautier, B.; et al. Investigating experimental short term imprint dynamics in ferroelectric hafnium oxide through phase-field modeling. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2025, e14094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buragohain, P.; Erickson, A.; Kariuki, P.; Mittmann, T.; Richter, C.; Lomenzo, P.D.; Lu, H.; Schenk, T.; Mikolajick, T.; Schroeder, U.; et al. Fluid imprint and inertial switching in ferroelectric La:HfO2 capacitors. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2019, 11, 35115–35121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pesic, M.; Schroeder, U.; Slesazeck, S.; Mikolajick, T. Comparative study of Reliability of ferroelectric and anti-ferroelectric memories. IEEE Trans. Device Mater. Reliab. 2018, 18, 154–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsiang, K.-Y.; Liao, C.-Y.; Lin, Y.-Y.; Lou, Z.-F.; Lin, C.-Y.; Lee, J.-Y.; Chang, F.-S.; Li, Z.-X.; Tseng, H.-C.; Wang, C.-C.; et al. Correlation between access polarization and high endurance (~1012 cycling) of ferroelectric and anti-ferroelectric HfZrO2. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE International Reliability Physics Symposium (IRPS), Dallas, TX, USA, 27–31 March 2022; IEEE: Dallas, TX, USA, 2022; pp. P9-1–P9-4. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, P.; Mao, G.-Q.; Cheng, Y.; Xue, K.-H.; Zheng, Y.; Yang, Y.; Jiang, P.; Xu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Y.; et al. Microscopic mechanism of imprint in hafnium oxide-based ferroelectrics. Nano Res. 2022, 15, 3667–3674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pešić, M.; Fengler, F.P.G.; Larcher, L.; Padovani, A.; Schenk, T.; Grimley, E.D.; Sang, X.; LeBeau, J.M.; Slesazeck, S.; Schroeder, U.; et al. Physical mechanisms behind the field-cycling behavior of HfO2-based ferroelectric capacitors. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2016, 26, 4601–4612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, H.-K.; Chiu, C.-Y.; Kao, Y.-C.; Wu, P.-J.; Wu, Y.-H. Enhanced reliability, switching speed and uniformity for ferroelectric HfZrOx on epitaxial Ge film by post deposition annealing for oxygen vacancy control. IEEE Trans. Electron Devices 2022, 69, 4002–4009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, M.; Peng, Y.; Xiao, W.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Du, P.; Jiang, H.; Liu, F.; Liu, Y.; Hao, Y.; et al. HfO2–ZrO2 ferroelectric capacitors with superlattice structure: Improving fatigue stability, fatigue recovery, and switching speed. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2024, 16, 2954–2963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, Z.; Zhao, L.; Lee, C.; Zhao, Y. Phase transitions and anti-ferroelectric behaviors in Hf1−xZrxO2 films. IEEE Electron Device Lett. 2023, 44, 1780–1783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhejiang Liryder Technologies Co., Ltd. Available online: https://www.liryder.com/en/ (accessed on 4 September 2025).

- Shi, Z.; Zhou, D.; Li, S.; Xu, J.; Schroeder, U. First-order reversal curve diagram and its application in investigation of polarization switching behavior of HfO2-based ferroelectric thin films. Acta Phys. Sin. 2021, 70, 127702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Zhou, D.; Shi, Z.; Hoffmann, M.; Mikolajick, T.; Schroeder, U. Involvement of unsaturated switching in the endurance cycling of Si-doped HfO2 ferroelectric thin films. Adv. Electron. Mater. 2020, 6, 2000264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schenk, T.; Hoffmann, M.; Ocker, J.; Pešić, M.; Mikolajick, T.; Schroeder, U. Complex internal bias fields in ferroelectric hafnium oxide. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2015, 7, 20224–20233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Y.; Huo, Y.; Yan, C.; Weng, Z.; Li, J.; Lan, Z.; Qu, Y.; Zhao, Y. Modeling of endurance degradation of anti-ferroelectric Hf1−xZrxO2 capacitors. In Proceedings of the 2024 Conference of Science and Technology for Integrated Circuits (CSTIC), Shanghai, China, 17–18 March 2024; IEEE: Shanghai, China, 2024; pp. 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, L.; Ding, Y.; Weng, Z.; Li, J.; Cai, D.; Zhao, Y. A compact model for degradation behaviors in Hf0.2Zr0.8O2 anti-ferroelectric devices. IEEE Trans. Electron Devices 2025, 72, 2936–2942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.C.; Yang, Z.Y.; Zheng, X.J. Residual stress in PZT thin films prepared by pulsed laser deposition. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2003, 162, 202–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catalan, G.; Sinnamon, L.J.; Gregg, J.M. The effect of flexoelectricity on the dielectric properties of inhomogeneously strained ferroelectric thin films. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 2004, 16, 2253–2264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.K.; Shin, G.Y.; Song, K.; Choi, W.S.; Shin, Y.A.; Park, S.Y.; Britson, J.; Cao, Y.; Chen, L.-Q.; Lee, H.N.; et al. Direct observation of asymmetric domain wall motion in a ferroelectric capacitor. Acta Mater. 2013, 61, 6765–6777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colla, E.L.; Tagantsev, A.K.; Taylor, D.V.; Kholkin, A.L. Fatigued state of the Pt-PZT-Pt system. Integr. Ferroelectr. 1997, 18, 19–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colla, E.L.; Taylor, D.V.; Tagantsev, A.K.; Setter, N. Discrimination between bulk and interface scenarios for the suppression of the switchable polarization (fatigue) in Pb(Zr,Ti)O3 thin films capacitors with Pt electrodes. Appl. Phys. Lett. 1998, 72, 2478–2480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, D.V.; Damjanovic, D.; Colla, E.; Setter, N. Fatigue and nonlinear dielectric response in sol-gel derived lead zirconate titanate thin films. Ferroelectrics 1999, 225, 91–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tagantsev, A.K.; Stolichnov, I.; Colla, E.L.; Setter, N. Polarization fatigue in ferroelectric films: Basic experimental findings, phenomenological scenarios, and microscopic features. J. Appl. Phys. 2001, 90, 1387–1402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, X.-Y.; Yu, J.; Ren, T.-L.; Xue, K.-H.; Zhou, W.-L.; Wang, Y.-B. Studies on the fatigue behavior of ferroelectric film using preisach approach. Integr. Ferroelectr. 2008, 99, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Postnikov, V.S.; Pavlov, V.S.; Turkov, S.K. Internal friction in ferroelectrics due to interaction of domain boundaries and point defects. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 1970, 31, 1785–1791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, L.; Soh, A.K.; Du, Q.G.; Li, J.Y. Interaction of O vacancies and domain structures in single crystal BaTiO3: Two-dimensional ferroelectric model. Phys. Rev. B 2008, 77, 094104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.; Yuan, X.; Tian, Z.; Zou, M.; Yuan, Y.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Jin, X.; Wu, T.; et al. A facile approach for generating ordered oxygen vacancies in metal oxides. Nat. Mater. 2025, 24, 835–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fengler, F.P.G.; Pešić, M.; Starschich, S.; Schneller, T.; Künneth, C.; Böttger, U.; Mulaosmanovic, H.; Schenk, T.; Park, M.H.; Nigon, R.; et al. Domain Pinning: Comparison of Hafnia and PZT Based Ferroelectrics. Adv. Electron. Mater. 2017, 3, 1600505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warren, W.L.; Pike, G.E.; Dimos, D.; Vanheusden, K.; Al-Shareef, H.N.; Tuttle, B.A.; Ramesh, R.; Evans, J.T. Voltage shifts and defect-dipoles in ferroelectric capacitors. MRS Proc. 1996, 433, 257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morozov, M.I.; Damjanovic, D. Hardening-softening transition in Fe-doped Pb(Zr,Ti)O3 ceramics and evolution of the third harmonic of the polarization response. J. Appl. Phys. 2008, 104, 034107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schenk, T.; Schroeder, U.; Pešić, M.; Popovici, M.; Pershin, Y.V.; Mikolajick, T. Electric field cycling behavior of ferroelectric hafnium oxide. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2014, 6, 19744–19751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S.; Zhou, D.; Shi, Z.; Hoffmann, M.; Mikolajick, T.; Schroeder, U. Temperature-dependent subcycling behavior of Si-doped HfO2 ferroelectric thin films. ACS Appl. Electron. Mater. 2021, 3, 2415–2422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stancu, A.; Ricinschi, D.; Mitoseriu, L.; Postolache, P.; Okuyama, M. First-order reversal curves diagrams for the characterization of ferroelectric switching. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2003, 83, 3767–3769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pešić, M.; Slesazeck, S.; Schenk, T.; Schroeder, U.; Mikolajick, T. Impact of charge trapping on the ferroelectric switching behavior of doped HfO2. Phys. Status Solidi A 2016, 213, 270–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimley, E.D.; Schenk, T.; Mikolajick, T.; Schroeder, U.; LeBeau, J.M. Atomic structure of domain and interphase boundaries in ferroelectric HfO2. Adv. Mater. Interfaces 2018, 5, 1701258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McPherson, J.W.; Kim, J.; Shanware, A.; Mogul, H.; Rodriguez, J. Trends in the ultimate breakdown strength of high dielectric-constant materials. IEEE Trans. Electron Devices 2003, 50, 1771–1778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumari, N.; Krupanidhi, S.B.; Varma, K.B.R. Dielectric, impedance and ferroelectric characteristics of c-oriented bismuth vanadate films grown by pulsed laser deposition. Mater. Sci. Eng. B 2007, 138, 22–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raghavan, N.; Pey, K.L.; Wu, X.; Liu, W.; Li, X.; Bosman, M.; Kauerauf, T. Oxygen-soluble gate electrodes for prolonged high-k gate-stack reliability. IEEE Electron Device Lett. 2011, 32, 252–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Migita, S.; Ota, H.; Yamada, H.; Shibuya, K.; Sawa, A.; Matsukawa, T.; Toriumi, A. Ion implantation synthesis of Si-doped HfO2 ferroelectric thin films. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE 2nd Electron Devices Technology and Manufacturing Conference (EDTM), Kobe, Japan, 13–16 March 2018; IEEE: Kobe, Japan, 2018; pp. 44–46. [Google Scholar]

- Böscke, T.S.; Müller, J.; Bräuhaus, D.; Schröder, U.; Böttger, U. Ferroelectricity in hafnium oxide thin films. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2011, 99, 102903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Huo, Y.; Li, J.; Weng, Z.; Ding, Y.; Chen, L.; Qi, J.; Qu, Y.; Zhao, Y. Dynamic Imprint and Recovery Mechanisms in Hf0.2Zr0.8O2 Anti-Ferroelectric Capacitors with FORC Characterization. Electronics 2025, 14, 4593. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14234593

Huo Y, Li J, Weng Z, Ding Y, Chen L, Qi J, Qu Y, Zhao Y. Dynamic Imprint and Recovery Mechanisms in Hf0.2Zr0.8O2 Anti-Ferroelectric Capacitors with FORC Characterization. Electronics. 2025; 14(23):4593. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14234593

Chicago/Turabian StyleHuo, Yuetong, Jianguo Li, Zeping Weng, Yaru Ding, Lijian Chen, Jiabin Qi, Yiming Qu, and Yi Zhao. 2025. "Dynamic Imprint and Recovery Mechanisms in Hf0.2Zr0.8O2 Anti-Ferroelectric Capacitors with FORC Characterization" Electronics 14, no. 23: 4593. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14234593

APA StyleHuo, Y., Li, J., Weng, Z., Ding, Y., Chen, L., Qi, J., Qu, Y., & Zhao, Y. (2025). Dynamic Imprint and Recovery Mechanisms in Hf0.2Zr0.8O2 Anti-Ferroelectric Capacitors with FORC Characterization. Electronics, 14(23), 4593. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14234593