Predictive Risk-Aware Reinforcement Learning for Autonomous Vehicles Using Safety Potential

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Literature Review

1.2. Contributions

2. Method

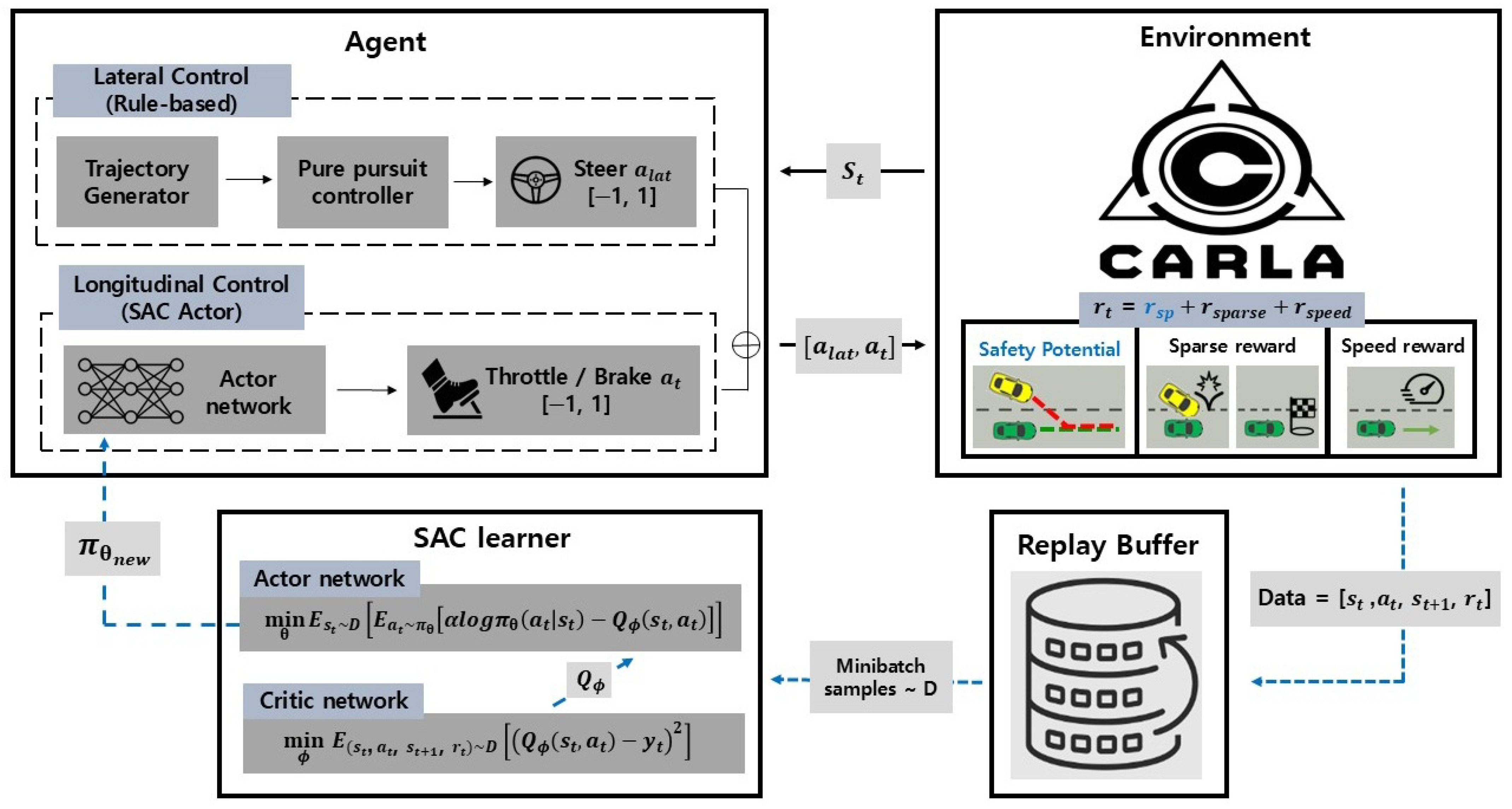

2.1. Overview

2.2. State Representation

2.3. Action and Control

2.4. Safety Potential: Discretized, Time-Weighted Overlap Risk

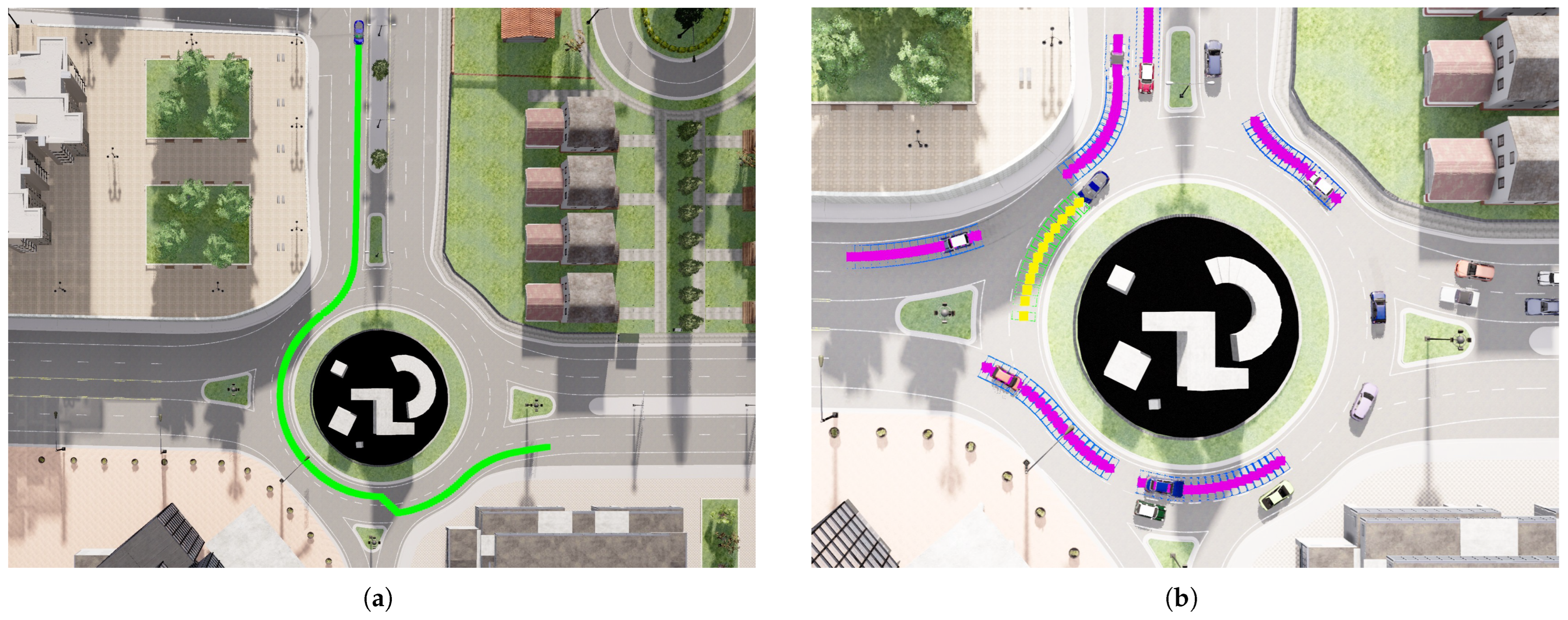

2.4.1. Route Discretization and Footprinting for SP

2.4.2. Overlap Area Definition

2.4.3. Normalized Weights (Time Weight)

2.4.4. Safety Potential Aggregate

2.4.5. Comparison of Pre-Collision Risk Metrics

2.5. Reward Design

2.5.1. Safety Potential Reward

2.5.2. Sparse Event Rewards

2.5.3. Speed Reward

2.5.4. Total Reward

2.6. Training Procedure (Soft Actor–Critic)

2.7. Experimental Setup

2.7.1. Traffic Generation

- headway to the leader: uniformly 6–20 m;

- desired speed scaling: uniformly ;

- lateral lane offset: uniformly m;

- ignore_lights: fixed (all NPCs ignore traffic lights to ensure steady inflow into the roundabout);

- ignore_vehicles: fixed (all NPCs occasionally ignore yielding, inducing near-collision conflicts).

2.7.2. Episode Protocol and Termination

2.7.3. Rule-Based Baseline (Calibration)

2.7.4. Agent Variants and Risk Shaping

- No-Safe: no dense per-step risk penalty.

- Distance (forward-distance shaping). Based on Equation (13) [8]; detections are limited to a forward cone to reduce false alarms. Unlike [8], we use a one-sided gap penalty (no penalty for large gaps) since the speed reward (Equation (10)) already captures efficiency. We set the gap margin to 15 m. With , the shaping term is as follows:

- TTC (time-to-collision shaping). Following Section 4.3 and Equation (13) of Lv et al. [8]—which computes and uses a 2.5 s margin—we adopt TTC as the surrogate and then apply roundabout-specific filters: we take the minimum over valid detections, ignore opposite-heading traffic, and disable the term when the ego is stationary. With , the shaping term is

- SP (ours): Safety Potential (time-weighted overlap; see Section 2.4) is used as the per-step shaping signal. The SP-based training procedure is summarized in Algorithm 1.

| Algorithm 1: SP-based Training Procedure |

| 1: Initialize networks and parameters . |

| 2: for episode do |

| 3: Spawn the ego vehicle and NPCs. |

| 4: while not (collision ∨ goal ∨ max_step) do |

| 5: Set (NPCs to observe at step t) and compose the state . |

| 6: Plan a local ego trajectory . |

| 7: Determine the steering command with the Pure Pursuit controller. |

| 8: Sample throttle , apply (steer, a), and step the environment to obtain . |

| 9: Replan the ego local trajectory and update predicted trajectories for NPCs . |

| 10: For each , compute ; then set . |

| 11: Compute reward r and store . |

| 12: Periodically update with the SAC optimizer. |

| 13: end while. |

| 14: Destroy the ego vehicle and all NPCs for the next episode. |

| 15: end for. |

| Output: learned longitudinal control policy . |

3. Results

3.1. Quantitative Results

3.1.1. Success and Collision Rates over Training

3.1.2. Speed Reward Comparison

3.2. Stress-Test Scenarios

3.3. Qualitative Study

3.3.1. Risk-Aligned Behavior Around Hazard Onset

3.3.2. Collision Case Analysis

- Case 1. The ego (blue box) changes from the inner to the outer lane as a red vehicle enters the same outer lane from an entrance. Because the first path overlap occurs only on a far segment of the ego’s plan, SP rises late as the vehicles converge, consistent with the delayed increase before the collision.

- Case 2. The ego (blue box) merges from an entrance into the inner lane while a white vehicle is already traveling there. SP briefly rises as a passing outer–lane car dominates, dips when it clears, then rises again as the inner–lane conflict becomes critical. Because SP takes the maximum overlap across surrounding vehicles, this temporary dominance understated the inner-lane risk; the ego kept merging, and a collision followed.

- Case 3. The ego (blue box) moves outward from the inner lane while a reddish-orange vehicle on the outer lane restarts from a stop. Because the first path overlap lies farther along the ego’s plan, SP stays at a moderate level without a sharp rise; risk is flagged but not high enough to trigger a stronger response, and a collision follows.

- Case 4. A red vehicle is blocked by a lead car ahead, while the ego (blue box) attempts to pass from behind. The path overlap is partial and oblique to the body, so SP stays very low (<5) despite footprint intersection, leading to underestimated risk.

3.4. Ablation Study

3.4.1. Safety-Augmented Policies in the Training Environment

3.4.2. SP as a State Feature

4. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Nomenclature (State Vector)

- State vector (total dimension = 49).

- Ego state

- v: ego-vehicle speed—divided by 20; clipped to [0, 1].

- : direction of ego-vehicle velocity—angular encoding.

- a: ego-vehicle acceleration—divided by 10; clipped to [0, 1].

- : direction of ego-vehicle acceleration—angular encoding.

- Progress

- g: goal progress ratio, (0 start, 1 goal).

- Lookahead target

- : lookahead distance—divided by 20; clipped to [0, 1].

- : lookahead direction—angular encoding.

- Surrounding vehicles

- If fewer than six vehicles are present, remaining slots are zero-filled; if more are present, the six nearest are kept (nearest-first).

- For each surrounding vehicle k:

- -

- : distance to vehicle k—divided by 20; clipped to .

- -

- : ego-relative direction to vehicle k — angular encoding.

- -

- : speed of vehicle k—divided by 20; clipped to .

- -

- : direction of velocity of vehicle k—angular encoding.

- -

- : yaw angle of vehicle k—angular encoding.

- -

- : acceleration of vehicle k—divided by 10; clipped to .

- -

- : direction of acceleration of vehicle k—angular encoding.

References

- Czechowski, P.; Kawa, B.; Sakhai, M.; Wielgosz, M. Deep Reinforcement and IL for Autonomous Driving: A Review in the CARLA Simulation Environment. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 8972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delavari, E.; Khanzada, F.K.; Kwon, J. A Comprehensive Review of Reinforcement Learning for Autonomous Driving in the CARLA Simulator. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2509.08221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Z.; Zhao, D. Adaptive Cruise Control Based on Reinforcement Learning with Shaping Rewards. J. Adv. Comput. Intell. Intell. Inform. 2011, 15, 351–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, M.; Wang, Y.; Pu, Z.; Hu, J.; Wang, X.; Ke, R. Safe, Efficient, and Comfortable Velocity Control Based on Reinforcement Learning for Autonomous Driving. Transp. Res. Part C 2020, 117, 102662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLaughlin, S.B.; Hankey, J.M.; Dingus, T.A. A Method for Evaluating Collision Avoidance Systems Using Naturalistic Driving Data. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2008, 40, 8–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasarinda, R.; Tharuminda, T.; Palitharathna, K.W.S.; Edirisinghe, S. Traffic Collision Avoidance with Vehicular Edge Computing. In Proceedings of the 2023 3rd International Conference on Advanced Research in Computing (ICARC), Belihuloya, Sri Lanka, 23–24 February 2023; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Mahmood, A.; Szabolcsi, R. A Systematic Review on Risk Management and Enhancing Reliability in Autonomous Vehicles. Machines 2025, 13, 646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, K.; Pei, X.; Chen, C.; Xu, J. A Safe and Efficient Lane Change Decision-Making Strategy of Autonomous Driving Based on Deep Reinforcement Learning. Mathematics 2022, 10, 1551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Liu, X.; Wu, Z. Design of Unsignalized Roundabouts Driving Policy of Autonomous Vehicles Using Deep Reinforcement Learning. World Electr. Veh. J. 2023, 14, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, C.; Guo, N. Biased-Attention Guided Risk Prediction for Safe Decision-Making at Unsignalized Intersections. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2510.12428. [Google Scholar]

- Haarnoja, T.; Zhou, A.; Abbeel, P.; Levine, S. Soft Actor–Critic: Off-Policy Maximum Entropy Deep Reinforcement Learning with a Stochastic Actor. In Proceedings of the 35th International Conference on Machine Learning (ICML), Stockholm, Sweden, 10–15 July 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Coulter, R.C. Implementation of the Pure Pursuit Path Tracking Algorithm; Technical Report CMU-RI-TR-92-01; Carnegie Mellon University, The Robotics Institute: Pittsburgh, PA, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Dosovitskiy, A.; Ros, G.; Codevilla, F.; López, A.; Koltun, V. CARLA: An Open Urban Driving Simulator. In Proceedings of the 1st Conference on Robot Learning (CoRL), Mountain View, CA, USA, 13–15 November 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Minsky, M. Steps toward Artificial Intelligence. Proc. IRE 2007, 49, 8–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mataric, M.J. Reward Functions for Accelerated Learning. In Machine Learning Proceedings 1994; Morgan Kaufmann: Burlington, MA, USA, 1994; pp. 181–189. [Google Scholar]

- Randløv, J.; Alstrøm, P. Learning to Drive a Bicycle Using Reinforcement Learning and Shaping. In Proceedings of the 15th International Conference on Machine Learning (ICML), San Francisco, CA, USA, 24–27 July 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Nageshrao, S.; Tseng, H.-E.; Filev, D. Autonomous Highway Driving using Deep Reinforcement Learning. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE International Conference on Systems, Man and Cybernetics (SMC), Bari, Italy, 6–9 October 2019; pp. 2326–2331. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Y.; Xu, X.; Li, Y.; Zhang, X.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, X. Vehicle-Following Control Based on Deep Reinforcement Learning. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 10648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alarcon, N. DRIVE Labs: Eliminating Collisions with Safety Force Field. NVIDIA Developer Blog. 2019. Available online: https://developer.nvidia.com/blog/drive-labs-eliminating-collisions-with-safety-force-field (accessed on 27 August 2025).

- Suk, H.; Kim, T.; Park, H.; Yadav, P.; Lee, J.; Kim, S. Rationale-Aware Autonomous Driving Policy Utilizing Safety Force Field Implemented on CARLA Simulator. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2211.10237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leng, B.; Yu, R.; Han, W.; Xiong, L.; Li, Z.; Huang, H. Risk-Aware Reinforcement Learning for Autonomous Driving: Improving Safety When Driving through Intersection. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2503.19690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, R.; Li, Z.; Xiong, L.; Han, W.; Leng, B. Uncertainty-Aware Safety-Critical Decision and Control for Autonomous Vehicles at Unsignalized Intersections. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2505.19939. [Google Scholar]

- Gan, J.; Zhang, J.; Liu, Y. Research on Behavioral Decision at an Unsignalized Roundabout for Automatic Driving Based on Proximal Policy Optimization Algorithm. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 2889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Z.; Tian, Z.; Lan, J.; Zhang, Q.; Ye, Z.; Zhuang, H.; Zhao, X. A Conflicts-Free, Speed-Lossless KAN-Based Reinforcement Learning Decision System for Interactive Driving in Roundabouts. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2408.08242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Replay buffer capacity | 200,000 |

| Batch size | 256 |

| Update frequency (env steps per optimize) | 5 |

| Actor/Critic/ learning rate | |

| Discount factor | 0.99 |

| Soft update coefficient | 0.001 |

| Target entropy | |

| Initial log- | |

| L2 regularization (critic) | |

| Actor network layer sizes (input output) | |

| Critic network layer sizes (input output) |

| Method | Success Rate ↑ | Collision Rate ↓ | Timeout Rate ↓ | Steps (Mean) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No-Safe | 78.00% | 21.75% | 0.25% | 249.5 |

| Distance | 81.00% | 12.50% | 6.50% | 286.3 |

| TTC | 88.25% | 10.25% | 1.50% | 345.2 |

| SP (ours) | 94.00% | 3.00% | 3.00% | 369.2 |

| Method | Test A: Aggressive Driving | Test B: High Density | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Success ↑ | Collision ↓ | Timeout ↓ | Steps (Mean) | Success ↑ | Collision ↓ | Timeout ↓ | Steps (Mean) | |

| No-Safe | 74.0% | 25.0% | 1.0% | 260.6 | 69.0% | 30.5% | 0.5% | 276.9 |

| Distance | 79.0% | 10.5% | 10.5% | 274.4 | 80.4% | 9.8% | 9.8% | 293.9 |

| TTC | 89.5% | 9.0% | 1.5% | 347.9 | 78.5% | 17.5% | 4.0% | 387.9 |

| SP (ours) | 90.0% | 5.5% | 4.5% | 365.2 | 92.0% | 3.5% | 4.5% | 397.7 |

| Method | Success ↑ | Collision ↓ | Timeout ↓ | Steps (Mean) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No-Safe + Hard Guard | 90.50% | 4.50% | 5.00% | 329.7 |

| Distance + Hard Guard | 82.75% | 3.00% | 14.25% | 382.0 |

| TTC + Hard Guard | 87.25% | 2.50% | 10.25% | 414.7 |

| SP + Hard Guard | 92.75% | 0.25% | 7.00% | 412.6 |

| Method | Success Rate ↑ | Collision Rate ↓ | Timeout Rate ↓ | Steps (Mean) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No-SP (=No-Safe) | 78.00% | 21.75% | 0.25% | 249.5 |

| SP state only | 89.25% | 8.00% | 2.75% | 292.5 |

| SP reward only | 94.00% | 3.00% | 3.00% | 369.2 |

| SP state + reward | 94.25% | 1.75% | 4.00% | 339.2 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Choi, J.; Kim, S. Predictive Risk-Aware Reinforcement Learning for Autonomous Vehicles Using Safety Potential. Electronics 2025, 14, 4446. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14224446

Choi J, Kim S. Predictive Risk-Aware Reinforcement Learning for Autonomous Vehicles Using Safety Potential. Electronics. 2025; 14(22):4446. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14224446

Chicago/Turabian StyleChoi, Jinho, and Shiho Kim. 2025. "Predictive Risk-Aware Reinforcement Learning for Autonomous Vehicles Using Safety Potential" Electronics 14, no. 22: 4446. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14224446

APA StyleChoi, J., & Kim, S. (2025). Predictive Risk-Aware Reinforcement Learning for Autonomous Vehicles Using Safety Potential. Electronics, 14(22), 4446. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14224446