A Complementary Fusion Framework for Robust Multimodal Emotion Recognition

Abstract

1. Introduction

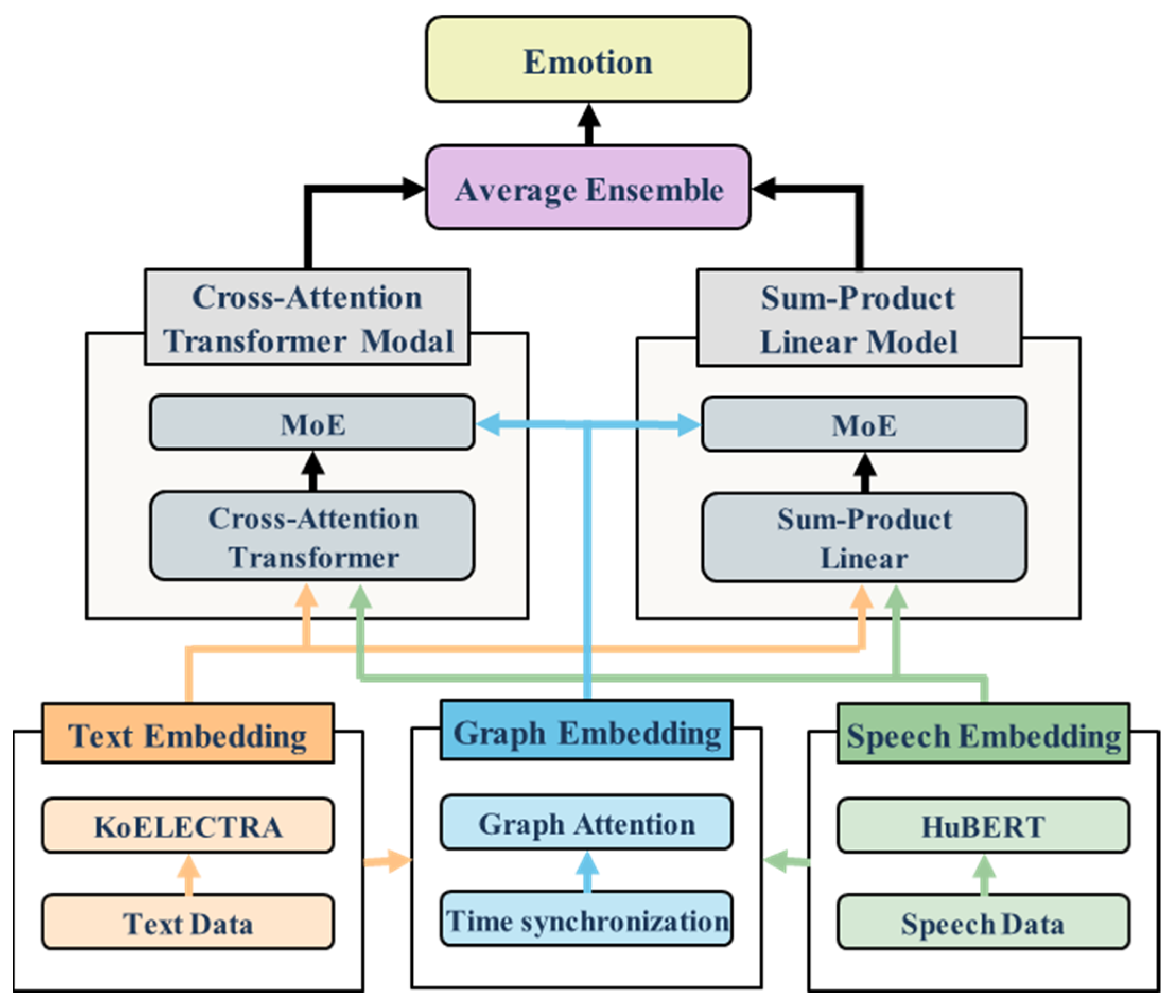

- Information Integration using Time-Aligned Graph Embedding: We model the connection structure between utterances in a graph format based on the temporal information of text and speech. By using this as an auxiliary modality, we effectively capture the temporal context and structural relationships of the dialogue, which have often been overlooked in existing models.

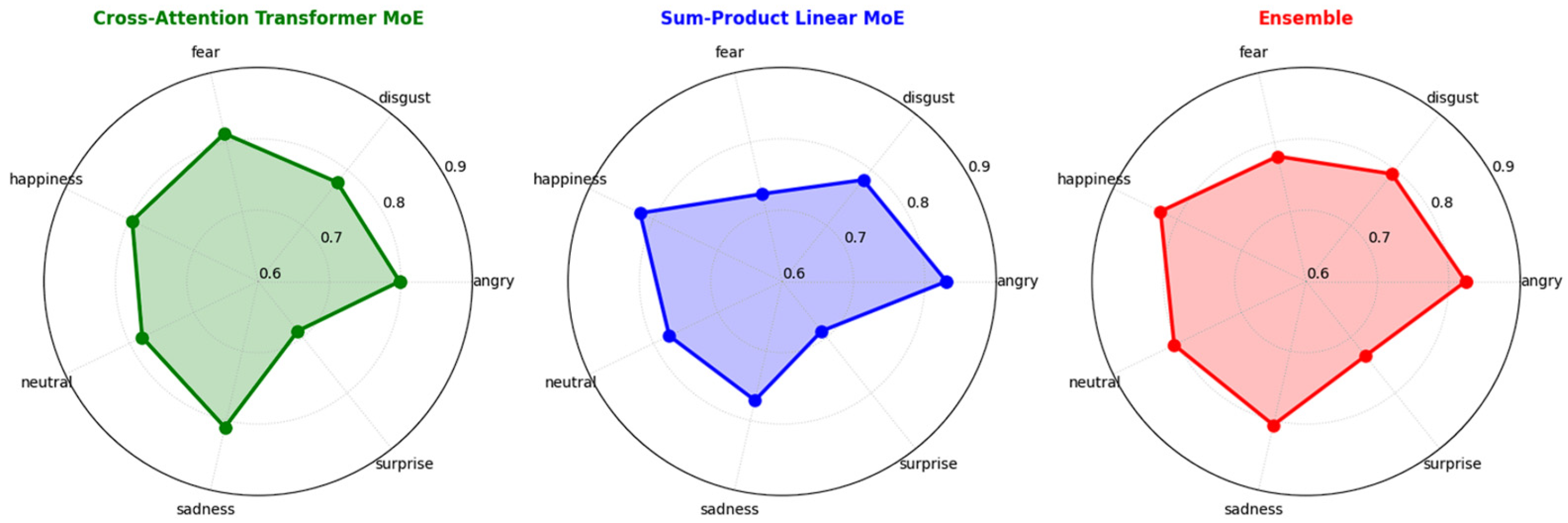

- Design of a Complementary Dual-Fusion Strategy: We propose a dual strategy that analyzes emotions with high affective complexity using a Cross-Attention Transformer structure, while analyzing those with high clarity using a Sum-Product Linear structure. This division is motivated by established affective computing theories, such as Russell’s Circumplex Model [22], which differentiate emotions based on dimensions like valence and arousal. We hypothesized that ‘clear’ emotions like ‘anger’ and ‘happiness’, which are typically high arousal, present distinct signals suitable for efficient, lightweight fusion. Conversely, ‘complex’ emotions like ‘fear’ and ‘sadness’, which are often low-arousal or ambiguous, exhibit subtle or even contradictory signals, such as strong text with weak audio. This necessitates a deep, bidirectional fusion model to decipher their intricate inter-modal dependencies. This presents a novel multimodal recognition architecture that can flexibly respond to various types of emotions.

- Quantitative Validation on Diverse Public Datasets: Through experiments on both the Korean AI-Hub Emotion in Dialogue dataset and the English IEMOCAP dataset, we empirically demonstrate the superiority and linguistic generalization capabilities of the proposed model.

- Practical Design for Industrial Applications: The model was designed with practical applicability in various industrial fields, such as education and healthcare, in mind. In particular, the proposed parallel structure and graph embedding enhance scalability and suitability for real-world application environments.

2. Related Work

2.1. Text- and Speech-Based Emotion Recognition

2.2. Multimodal Emotion Recognition

2.3. MoE Architecture

3. Proposed Mechanism

3.1. Input Embeddings

3.1.1. Text Embedding

| Algorithm 1. Text Embedding using KoELECTRA |

|

1: procedure GenerateTextEmbedding(text_input) 2: tokenizer ← LoadTokenizer(“koelectra-base-v3”) 3: model ← LoadModel(“koelectra-base-v3”) 4: input_features ← tokenizer(text, padding = “max_length”, max_length = 128, truncation = True) 5: model_output ← model(input_features) 6: text_embedding ← outputs.last_hidden_state 7: return text_embedding 8: end procedure |

3.1.2. Speech Embedding

| Algorithm 2. Speech Embedding using HuBERT |

|

1: procedure GenerateSpeechEmbedding(speech_path) 2: extractor ← LoadFeatureExtractor(“hubert-base-ls960”) 3: model ← LoadModel(“hubert-base-ls960”) 4: audio, sr ← LoadAudio(speech_path, sr = 16,000) 5: input_features ← extractor(audio, sampling rate = sr, return tensors = “pt”) 6: model_output ← model(input_features) 7: speech_embedding ← outputs.last_hidden_state 8: if speech_embedding.shape[1] < 128 then 9: pad ← 128 − speech_embedding.shape[1] 10: speech_embedding ← Pad(speech_embedding, (0, 0, 0, pad)) 11: else if speech_embedding.shape[1] > 128 then 12: speech_embedding ← AdaptiveAvgPool1D(Permute(embedding, (0, 2, 1)), output size = 128) 13: speech_embedding ← Permute(speech_embedding, (0, 2, 1)) 14: end if 15: return speech_embedding 16: end procedure |

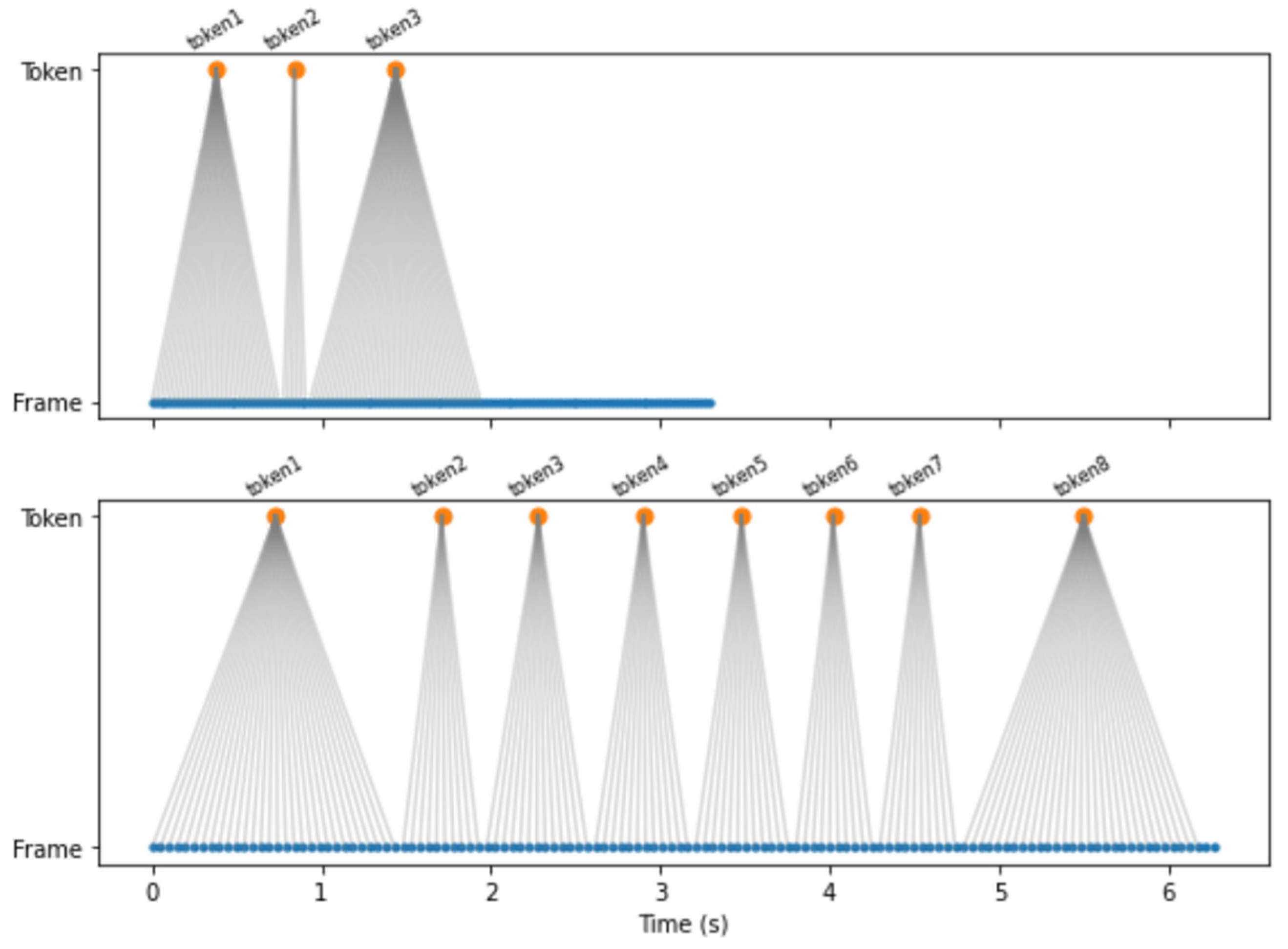

3.1.3. Graph Embedding

| Algorithm 3. Graph Embedding Construction |

|

1: procedure GenerateGraphEmbedding (text_embeddings, speech_embeddings, speech_path) 2: whisper_model ← LoadWhisperModel() 3: audio ← LoadAndResampleAudio(speech_path, target_sr = 16,000) 4: token_timestamps ← Transcribe(whisper_model, audio, get_timestamps = True) 5: speech_frame_times ← GetFrameTimestamps(speech_embeddings) 6: edge_list ← [] 7: for i, token in enumerate(token_timestamps): 8: for j, frame in enumerate(speech_frame_times): 9: if frame.time ≥ token.start and frame.time ≤ token.end then 10: edge_list.append([i, j]) 11: end if 12: edge_index ← ConvertToEdgeIndex(edge_list) 13: gat_model ← LoadGATModel() 14: final_graph_embedding ← gat_model(text_nodes = text_embeddings, 15: speech_nodes = speech_embeddings, 16: edge_index = edge_index) 17: return final_graph_embedding 18: end procedure |

3.2. Cross-Attention Transformer MoE

| Algorithm 4. Cross-Attention Transformer |

|

1: procedure CrossAttentionLayer(query_input, key_input, value_input) 2: quert ← LinearProjection(query_input) 3: key ← LinearProjection(key_input) 4: value ← LinearProjection(value_input) 5: Reshape query, key, value to shape (B, H, L, D/H) 6: attn ← Softmax(()/√D) 7: attention_output ← attn · value 8: Reshape and project output to shape (B, L, D) 9: return final_output 10: end procedure |

3.3. Sum-Product Linear MoE

| Algorithm 5. Sum-Product Linear |

|

1: procedure SumProductFusion(text_vector, speech_vector) 2: sum_vector ← text_vector + speech_vector 3: product_vector ← text_vector⊙speech_vector 4: concatenated_vector ← Concat(text_vector, speech_vector, sum_vector, product_vector) 5: fused_vector ← LinearProjection(concatenated_vector) 6: return fused_vector 7: end procedure |

3.4. Multimodal Emotion Recognition Model

4. Experimental Evaluation

4.1. Experimental Data

4.1.1. AI-HuB Dataset

4.1.2. IEMOCAP Dataset

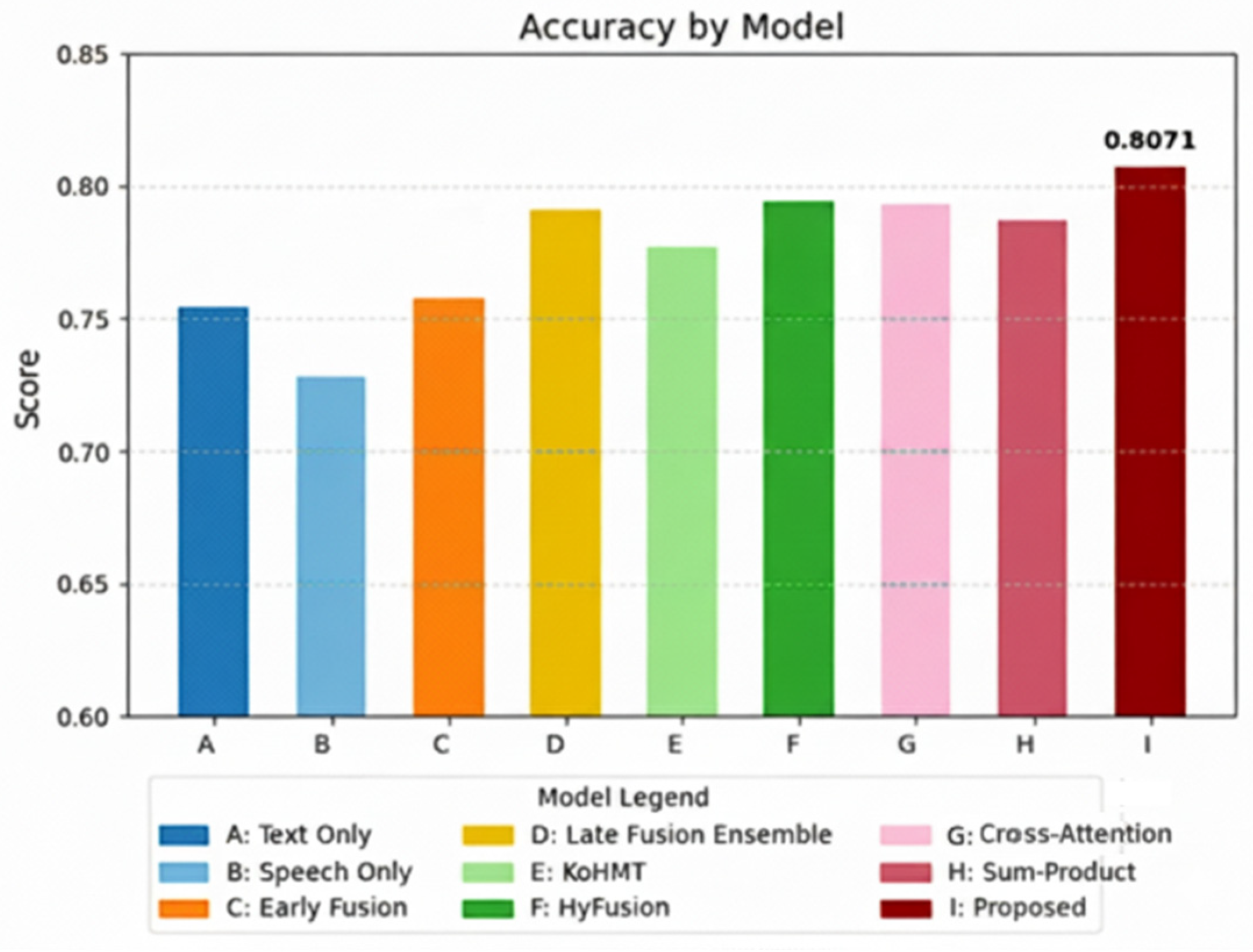

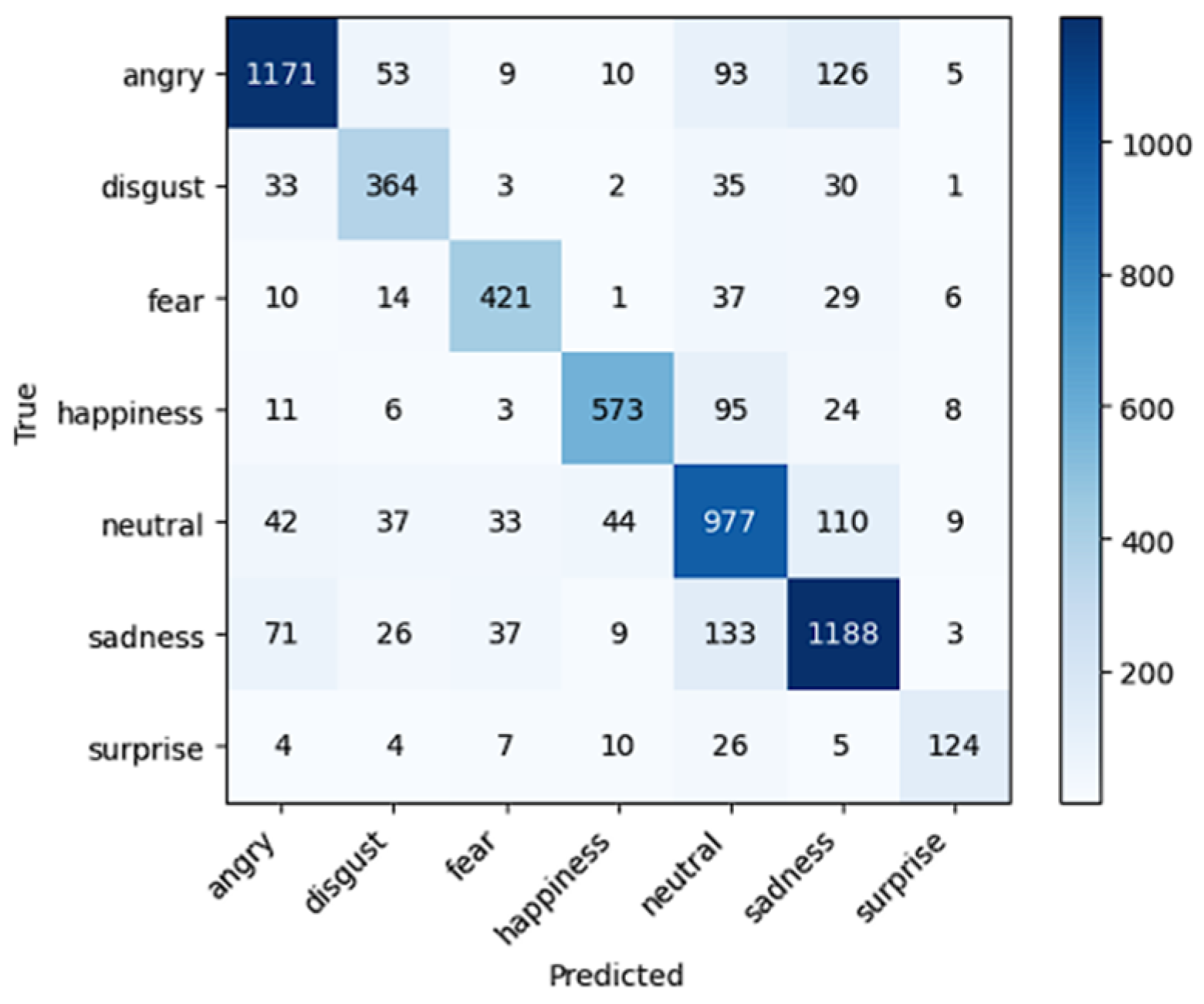

4.2. Performance Evaluation and Analysis

4.2.1. Experimental Environment and Evaluation Metrics

4.2.2. Comparative Models and Experimental Design

4.2.3. Overall Performance Comparison and Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Xie, Z.; Guan, L. Multimodal information fusion of audiovisual emotion recognition using novel information theoretic tools. In Proceedings of the 2013 IEEE International Conference on Multimedia and Expo (ICME), San Jose, CA, USA, 15–19 July 2013; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Busso, C.; Bulut, M.; Narayanan, S. Toward effective automatic recognition systems of emotion in speech. In Social Emotions in Nature and Artifact: Emotions in Human and Human-Computer Interaction; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 110–127. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, T.; Vossen, P. EmoBERTa: Speaker-aware emotion recognition in conversation with RoBERTa. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2108.12009. [Google Scholar]

- Soleymani, M.; Garcia, D.; Jou, B.; Schuller, B.; Chang, S.-F.; Pantic, M. A survey of multimodal sentiment analysis. Image Vis. Comput. 2017, 65, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bharti, S.K.; Kumar, P.; Kumari, K.; Rashid, M.; Faiyaz, M.; Kumar, V.; Kumar, R. Text-based emotion recognition using deep learning approach. Comput. Intell. Neurosci. 2022, 2022, 9523756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Lee, S.-P. A BiLSTM–transformer and 2D CNN architecture for emotion recognition from speech. Electronics 2023, 12, 4034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabbeh, S.F.; Fasihuddin, H.A. A comparative analysis of word embedding and deep learning for Arabic sentiment classification. Electronics 2023, 12, 1425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutinda, J.; Mwangi, W.; Okeyo, G. Sentiment analysis of text reviews using lexicon-enhanced Bert embedding (LeBERT) model with convolutional neural network. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 1445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Ma, Y.; Ma, Z.; Zhu, H. Weibo text sentiment analysis based on BERT and deep learning. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 10774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reggiswarashari, F.; Sihwi, S.W. Speech emotion recognition using 2D-convolutional neural network. Int. J. Electr. Comput. Eng. 2022, 12, 6594–6601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazra, S.K.; Ema, R.R.; Galib, S.M.; Kabir, S.; Adnan, N. Emotion recognition of human speech using deep learning method and MFCC features. Spec. Syst. Data Process. 2022, 4, 161–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez-Gonzalez, N.; Kaltenbrunner, A.; Gómez, V. Uncovering the limits of text-based emotion detection. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2109.01900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, S.M.; Ilyas, P.M. A review on speech emotion recognition: A survey, recent advances, challenges, and the influence of noise. Neurocomputing 2024, 568, 127015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Z.; Ortega, J.; Wang, Y.; Chen, Z.; Guo, Y.; Yu, S.X.; Whitney, D. VEATIC: Video-based emotion and affect tracking in context dataset. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision (WACV), Waikoloa, HI, USA, 4–8 January 2024; pp. 4467–4477. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Y.-J.; Roh, K.; Chae, D. Feature-based emotion recognition model using multimodal data. In Proceedings of the 2023 Korean Computer Congress (KCC), Seoul, Republic of Korea, 21–23 June 2023; Korean Institute of Information Scientists and Engineers: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2023; pp. 2169–2171. [Google Scholar]

- Park, H. Enhancement of multimodal emotion recognition classification model through weighted average ensemble of KoBART and CNN models. In Proceedings of the 2023 Korean Computer Congress (KCC), Seoul, Republic of Korea, 21–23 June 2023; Korean Institute of Information Scientists and Engineers: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2023; pp. 2157–2159. [Google Scholar]

- Gladys, A.A.; Vetriselvi, V. Survey on multimodal approaches to emotion recognition. Neurocomputing 2023, 556, 126693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lian, H.; Lu, C.; Li, S.; Zhao, Y.; Tang, C.; Zong, Y. A survey of deep learning-based multimodal emotion recognition: Speech, text, and face. Entropy 2023, 25, 1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramaswamy, M.P.A.; Palaniswamy, S. Multimodal emotion recognition: A comprehensive review, trends, and challenges. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Data Min. Knowl. Discov. 2024, 14, e1563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shou, Y.; Meng, T.; Ai, W.; Yin, N.; Li, K. A comprehensive survey on multi-modal conversational emotion recognition with deep learning. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2312.05735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Gu, Y.; Yin, Y.; Han, Y.; Zhang, H.; Wang, S.; Li, C.; Quan, D. Multimodal transformer augmented fusion for speech emotion recognition. Front. Neurorobot. 2023, 17, 1205391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, A.; Russell. A Circumplex Model of Affect. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1980, 39, 1161–1178. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Kou, L.; Sugumaran, V.; Luo, X.; Zhang, H. Emotion correlation mining through deep learning models on natural language text. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2007.14071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habib, M.A.; Akhand, M.A.H.; Kamal, M.A.S. Emotion recognition from microblog managing emoticon with text and classifying using 1D CNN. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2301.02971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, B.; Cheun, S.; Kim, Y.; Kim, S. An emotion recognition technique using speech signals. J. Korean Inst. Intell. Syst. 2008, 18, 494–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, H.; Si, Y.; Chen, C.; Rajan, D.; Chng, E.S. Speech emotion recognition with co-attention based multi-level acoustic information. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2203.15326. [Google Scholar]

- Jo, A.-H.; Kwak, K.-C. Feature level fusion based on canonical correlation analysis for Korean speech emotion recognition. In Proceedings of the 2023 KIIT Summer Conference, Jeju, Republic of Korea, 21–23 June 2023; pp. 244–248. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, M.; Tran, P.-N.; Pham, N.T.; El Saddik, A.; Othmani, A. MemoCMT: Multimodal emotion recognition using cross-modal transformer-based feature fusion. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 5473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yi, M.-H.; Kwak, K.-C.; Shin, J.-H. HyFusER: Hybrid multimodal transformer for emotion recognition using dual cross modal attention. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ai, W.; Shou, Y.; Meng, T.; Yin, N.; Li, K. DER-GCN: Dialogue and event relation-aware graph convolutional neural network for multimodal dialogue emotion recognition. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2312.10579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Wang, X.; Liu, Y.; Zeng, Z. CFN-ESA: A cross-modal fusion network with emotion-shift awareness for dialogue emotion recognition. IEEE Trans. Affect. Comput. 2024, 15, 1919–1933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shazeer, N.; Mirhoseini, A.; Maziarz, K.; Davis, A.; Le, Q.; Hinton, G.; Dean, J. Outrageously large neural networks: The sparsely-gated mixture-of-experts layer. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1701.06538. [Google Scholar]

- Fedus, W.; Zoph, B.; Shazeer, N. Switch transformers: Scaling to trillion parameter models with simple and efficient sparsity. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2101.03961. [Google Scholar]

- Goyal, A.; Kumar, N.; Guha, T.; Narayanan, S.S. A multimodal mixture-of-experts model for dynamic emotion prediction in movies. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP), Shanghai, China, 20–25 March 2016; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 2825–2829. [Google Scholar]

- Dialogue Voice Dataset for Emotion Classification. Available online: https://aihub.or.kr/aihubdata/data/view.do?dataSetSn=263 (accessed on 31 August 2025).

- IEMOCAP Database. Available online: https://sail.usc.edu/iemocap/ (accessed on 13 May 2025).

| Emotion Class | Data Count (%) |

|---|---|

| Anger | 7333 (24.15) |

| Sadness | 7333 (24.15) |

| Neutral | 6261 (20.62) |

| Happiness | 3601 (11.86) |

| Fear | 2588 (8.52) |

| Disgust | 2339 (7.9) |

| Surprise | 903 (2.97) |

| Total | 30,358 (100) |

| Indicator | Formula | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Accuracy | Proportion of correct predictions | |

| Precision | Proportion of true positives among positive predictions | |

| Recall | Proportion of true positives among actual positives | |

| F1-Score | Harmonic mean of Precision and Recall |

| Hyperparameter | Cross-Attention Transformer | Sum-Product Linear MoE |

|---|---|---|

| Optimization Algorithm | Adam | Adam |

| LR Scheduler | OneCycleLR | None |

| Learning Rate | 1 × 10−4 (max) | 1 × 10−4 (Fixed) |

| Dropout | 0.1 | 0.1 |

| Batch Size | 32 | 32 |

| Max Epochs | 100 | 100 |

| Early Stopping | Patience = 5 | Patience = 5 |

| Number of Experts | 5 | 5 |

| Category | Modality | Model |

|---|---|---|

| Unimodal Models | Text | Bidirectional LSTM |

| Speech | CNN | |

| Graph Embedding | MLP | |

| Simple Multimodal Models | Text + Speech | Early Fusion, Late Fusion |

| Existing Transformer- based Models | Text + Speech | KoHMT, HyFusER |

| Proposed Models | Text + Speech + Graph Embedding | Cross-Attention Transformer and Sum-Product Linear Late Fusion |

| Modal | Fusion Method | Accuracy | Precision | Recall | F1-Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unimodal | Text (BiLSTM) | 0.7540 | 0.7558 | 0.7540 | 0.7541 |

| Speech (CNN) | 0.7281 | 0.7372 | 0.7281 | 0.7302 | |

| Graph (MLP) | 0.5637 | 0.5750 | 0.5637 | 0.5539 | |

| Multimodal | Early Fusion | 0.7576 | 0.7615 | 0.7576 | 0.7580 |

| Late Fusion | 0.7913 | 0.8011 | 0.7913 | 0.7938 |

| Model | Accuracy | Precision | Recall | F1-Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| KoHMT | 0.7771 | 0.7797 | 0.7771 | 0.7778 |

| HyFusER | 0.7944 | 0.7937 | 0.7944 | 0.7936 |

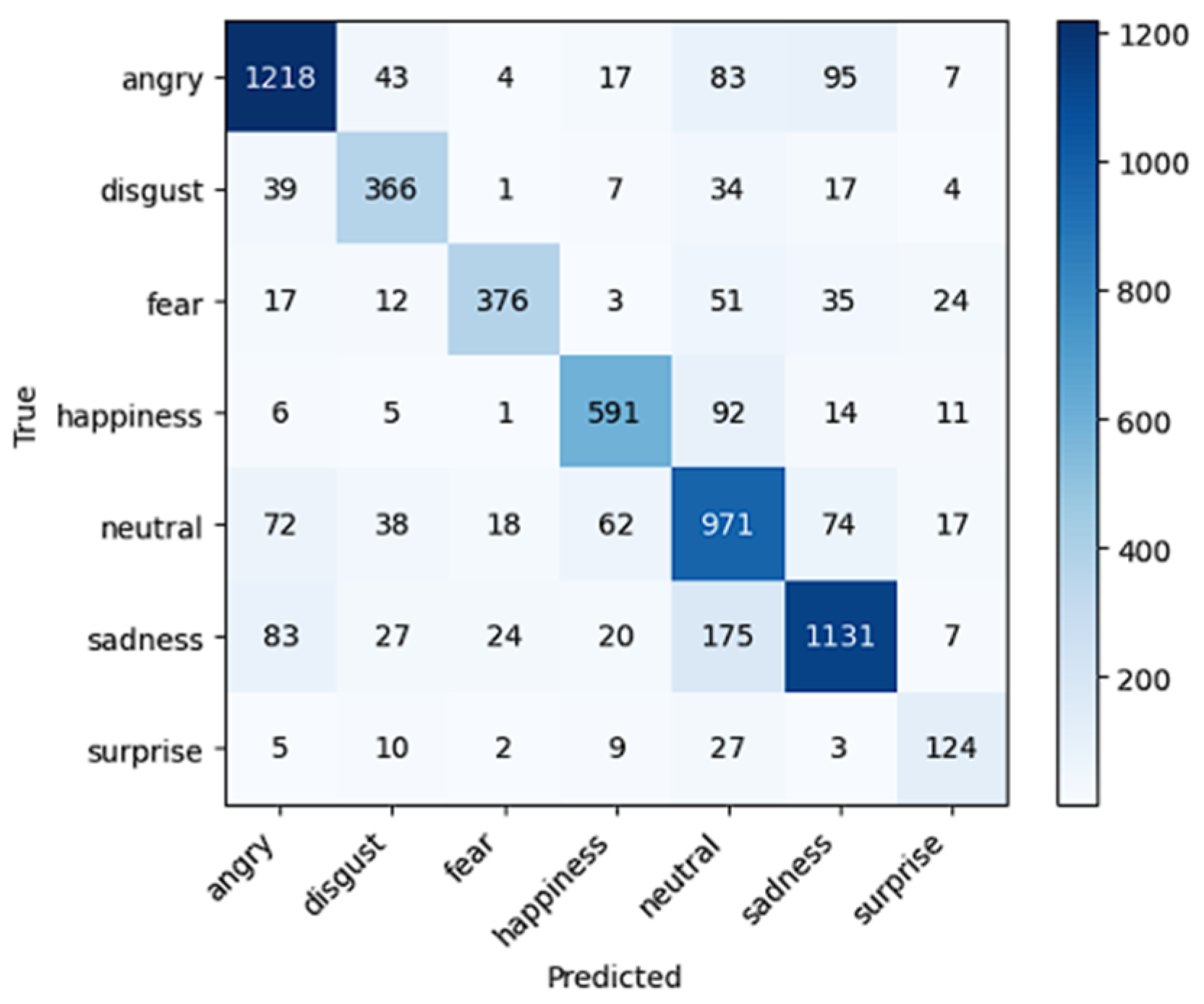

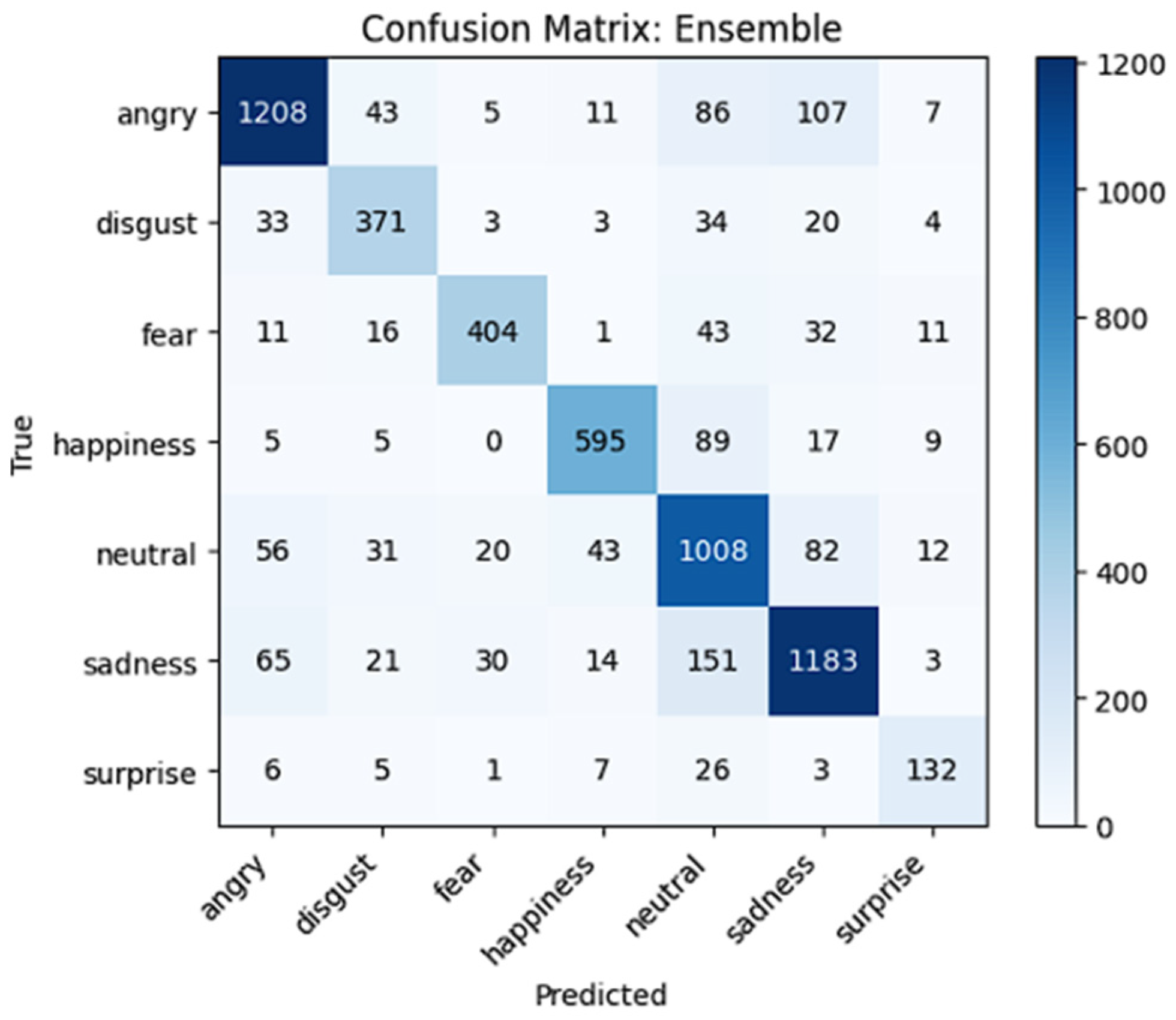

| Cross-Attention Transformer MoE | 0.7940 | 0.7961 | 0.7804 | 0.7865 |

| Sum-Product Linear MoE | 0.7851 | 0.7918 | 0.7624 | 0.7721 |

| Proposed model | 0.8073 | 0.8139 | 0.7898 | 0.7997 |

| Model | Metric | Mean | SD | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cross-Attention Transformer MoE | Accuracy | 0.7940 | 0.0031 | [0.7918, 0.7962] |

| F1-Score | 0.7865 | 0.0025 | [0.7847, 0.7883] | |

| Sum-Product Linear MoE | Accuracy | 0.7851 | 0.0036 | [0.7825, 0.7877] |

| F1-Score | 0.7721 | 0.0038 | [0.7694, 0.7748] | |

| Proposed Model | Accuracy | 0.8073 | 0.0014 | [0.8063, 0.8083] |

| F1-Score | 0.7997 | 0.0022 | [0.7982, 0.8013] |

| Model | Accuracy | Precision | Recall | F1-Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Top-1 | 0.8071 | 0.8064 | 0.7953 | 0.7997 |

| Top-2 | 0.8113 | 0.8122 | 0.7985 | 0.8043 |

| Model | Number of Experts | Number of Parameters | Inference Speed (ms) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cross-Attention Transformer MoE | 1000 | 210,892,911 | 2.08 |

| Sum-Product Linear MoE | 1000 | 206,525,935 | 0.69 |

| Model | Accuracy | Precision | Recall | F1-Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Text (BiLSTM) | 0.5766 | 0.5240 | 0.5766 | 0.5450 |

| Speech (CNN) | 0.6615 | 0.6521 | 0.6615 | 0.6481 |

| Graph (MLP) | 0.5850 | 0.5263 | 0.5850 | 0.5521 |

| Early Fusion | 0.6859 | 0.6746 | 0.6859 | 0.6768 |

| Late Fusion | 0.6702 | 0.6657 | 0.6702 | 0.6652 |

| Cross-Attention Transformer MoE | 0.7768 | 0.7773 | 0.7880 | 0.7803 |

| Sum-Product Linear MoE | 0.7757 | 0.7802 | 0.7773 | 0.7766 |

| Proposed model | 0.7823 | 0.7832 | 0.7870 | 0.7843 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yi, M.-H.; Kwak, K.-C.; Shin, J.-H. A Complementary Fusion Framework for Robust Multimodal Emotion Recognition. Electronics 2025, 14, 4444. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14224444

Yi M-H, Kwak K-C, Shin J-H. A Complementary Fusion Framework for Robust Multimodal Emotion Recognition. Electronics. 2025; 14(22):4444. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14224444

Chicago/Turabian StyleYi, Moung-Ho, Keun-Chang Kwak, and Ju-Hyun Shin. 2025. "A Complementary Fusion Framework for Robust Multimodal Emotion Recognition" Electronics 14, no. 22: 4444. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14224444

APA StyleYi, M.-H., Kwak, K.-C., & Shin, J.-H. (2025). A Complementary Fusion Framework for Robust Multimodal Emotion Recognition. Electronics, 14(22), 4444. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14224444