1. Introduction

1.1. Background and Motivation

The widespread use of embedded devices in critical fields such as aerospace, industrial control, railway transportation, and medical equipment makes the security of operating systems a core factor in ensuring system reliability and stability [

1]. As a representative of embedded real-time operating systems, VxWorks’ operational security directly impacts the correctness of task execution and the reliability of device behavior [

2]. To counter runtime attacks such as stack overflows, code injections, and illegal memory accesses, the VxWorks kernel incorporates various memory protection mechanisms [

3], including text segment write protection, exception vector table protection, task stack overflow detection, task stack non-executable protection, interrupt stack protection, and data segment non-executable protection [

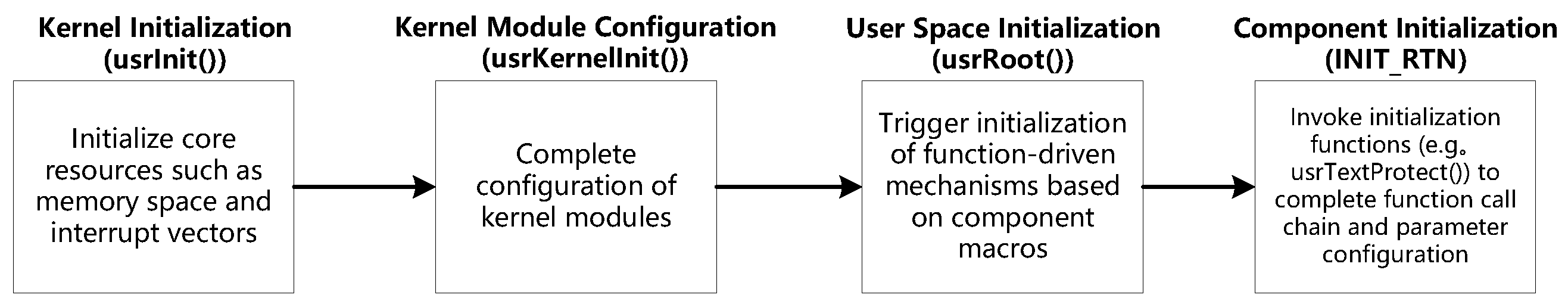

4]. These mechanisms are configured during startup or runtime through specific function call chains [

5], in order to enhance the system’s resilience against attacks.

However, recent security incidents have exposed significant risks in VxWorks’ memory security [

6]. In 2019, Armis Labs revealed the “URGENT/11” vulnerability event, identifying 11 zero-day vulnerabilities in the VxWorks’ TCP/IP protocol stack, involving issues such as heap overflows, stack overflows, integer underflows, and null pointer dereferences [

6,

7]. Six of these vulnerabilities could be remotely exploited, affecting more than 2 billion devices, including medical infusion pumps, industrial controllers, and SCADA systems [

6,

8,

9]. This incident prompted a joint advisory from the U.S. CISA and FDA, which urged vendors to promptly address the issues and improve security measures [

10]. Additionally, in recent years, high-risk vulnerabilities such as integer overflows in memory allocation functions (e.g., calloc) and buffer overrun issues in DHCP services have been discovered [

11], reflecting design flaws in VxWorks’ memory management and control flow validation [

12]. Due to the diversity of embedded system versions, the lack of symbol information, and the high costs of firmware updates, many systems remain unpatched, increasing security risks [

13,

14,

15]. These incidents highlight the need for runtime verification of memory protection configurations in VxWorks.

1.2. Related Work

Binary analysis and dynamic instrumentation techniques form the foundation of OS security research, widely applied in vulnerability discovery, reverse engineering, and firmware analysis [

16]. Early works, such as Shacham et al. [

17] on ASLR, laid the theoretical groundwork for dynamic behavior monitoring, while dynamic binary instrumentation (DBI) frameworks like DynamoRIO and Pin [

18] enable fine-grained analysis via runtime code injection, supporting taint tracking and symbolic execution. However, these tools primarily target user-space processes and struggle with RTOS kernel-level real-time execution.

In RTOS security, VxWorks and similar embedded systems face unique challenges, such as the URGENT/11 vulnerabilities exposing TCP/IP stack overflows [

6], affecting over 2 billion devices. Prior studies include PowerFL [

1] for fuzzing VxWorks firmware vulnerabilities and FirmPorter [

19] for binary-level RTOS porting to support re-hosting, but these rely on hardware interfaces or source access, failing to enable non-intrusive runtime monitoring. The DIVER framework [

1] embeds agents for VxWorks runtime visibility but introduces overhead impacting real-time performance.

Compared to existing dynamic analysis frameworks, the proposed approach demonstrates significant novelty compared to PANDA and Avatar

2, and Triton.PANDA [

20], a QEMU-based whole-system DBI platform, supports architecture-neutral reverse engineering and taint analysis for RTOS firmware replay, but lacks VxWorks-specific function call chain templates for automated memory protection identification. Avatar

2 [

21], a multi-target orchestration platform, bridges emulators and physical devices for embedded firmware fuzzing and vulnerability discovery [

22], yet requires JTAG-like hardware debugging interfaces unsuitable for purely closed-source emulation and involves complex setup. Triton [

23] provides a dynamic symbolic execution (DSE) and taint engine, converting ×86 semantics to SMT for VM-based code reversal [

24], but its process-level design does not adapt to VxWorks kernel initialization paths and omits static path modeling.

In contrast, this paper proposes a detection method tailored for VxWorks, which instruments function call instructions at the QEMU TCG layer to dynamically reconstruct call chains and combines them with static modeling to automatically identify the activation status of key memory protection mechanisms, such as text segment write protection and stack non-executability. To validate the method’s effectiveness, three groups of firmware samples were designed, representing scenarios with no protection, partial protection, and full protection enabled. Experimental results demonstrate that the method delivers accurate and reliable detection across various configurations, with no false positives or false negatives. Furthermore, open-source test cases enhance the credibility and reproducibility of the experiments. This approach, characterized by automation, non-intrusiveness, and high adaptability, provides an efficient tool for verifying the security configurations of closed-source embedded systems.

Existing methods, such as AFL++ [

25] and GDB dynamic taint analysis [

26], are primarily designed for Linux or general embedded platforms, making them difficult to directly adapt to VxWorks’ highly customized and closed-source nature. This research gap poses potential risks to VxWorks systems in high-safety-demand scenarios such as aerospace and industrial control, highlighting the necessity and pioneering nature of memory protection detection methods tailored for this platform.

1.3. Contributions

(1) A dynamic function call chain monitoring method based on QEMU dynamic binary translation is proposed. This method performs semantic recognition of function call instructions under the ×86 architecture and injects lightweight instrumentation logic during the IR generation stage. It enables real-time capture of function call behaviors and key parameters during emulation. By dynamically reconstructing function call chains and correlating them with statically extracted symbol mappings and predefined path templates, the method automatically determines the activation status of memory protection mechanisms in VxWorks. It exhibits strong platform generality and a high degree of automation. Ref. [

27] proposed a general QEMU-based dynamic instrumentation framework for binary behavior monitoring; this work extends it to real-time function call chain tracking in closed-source VxWorks. Ref. [

28] validated the low overhead of IR-stage instrumentation; this work applies it to high-precision analysis in embedded real-time systems.

(2) A static template for VxWorks 7 memory protection mechanisms is constructed. Through systematic analysis of official documentation and kernel source code, six representative mechanisms were identified, and their initialization paths and configuration logic were extracted and classified into function-driven and parameter-controlled types. This structured representation provides a reliable template for dynamic behavior recognition. Ref. [

29] is the official VxWorks 7 Kernel Programmer’s Guide; this work is the first to systematically model memory-protection-related function call chains based on it.

Without requiring source code access, the proposed method enables runtime identification of memory protection mechanisms in closed-source firmware, demonstrating strong adaptability and automation capabilities. It is applicable to scenarios such as system configuration integrity verification and security mechanism validation. Experimental results show that the proposed approach outperforms existing techniques in terms of detection accuracy, false-positive and false-negative control, and performance overhead. It efficiently supports runtime status identification for multiple types of protection mechanisms and provides a practical and effective solution for behavior-level security analysis of closed-source systems.

2. Problem Analysis

In closed-source VxWorks firmware, determining whether memory protection mechanisms are truly enabled is a well-defined challenge. As a real-time operating system widely used in high-security domains such as defense, aerospace, rail transit, and industrial control, VxWorks is designed to balance performance optimization and security isolation. Its source code has long been commercially closed, and the system exhibits a high degree of customization across different device models and mission requirements. This dual characteristic of “strong customization + closed source” prevents researchers from directly accessing the internal configuration logic and makes it difficult to observe runtime behavior through traditional reverse engineering or debugging approaches. Furthermore, the prevalent security confidentiality requirements and environmental isolation constraints in these domains further hinder external researchers from directly verifying or performing runtime tracing of its memory protection mechanisms.

Existing security detection and dynamic analysis methods targeting general-purpose operating systems (e.g., Linux, Windows) largely rely on accessible symbol information, source code, or debugging interfaces. However, these methods often fail on the VxWorks platform: static analysis can extract function symbols and control-flow information but cannot confirm the runtime activation status of mechanism configurations; dynamic analysis, on the other hand, is constrained by the access-closed nature and real-time requirements of closed-source systems, making effective monitoring difficult without interfering with the original system behavior. Therefore, constructing a detection method that is both observable and non-intrusive, without compromising system integrity, has become the core challenge in addressing the closed-source nature of VxWorks.

To this end, this paper proposes a non-intrusive monitoring approach based on QEMU dynamic binary translation, which overcomes existing bottlenecks through the following technical pathway: first, lightweight semantic instrumentation is injected at the QEMU TCG intermediate representation (IR) layer for CALL instructions, enabling runtime behavior capture without modifying guest code or relying on debugging interfaces; second, VxWorks 7-specific static call-chain templates (categorized into function-driven and parameter-controlled types) are constructed to provide high-precision semantic priors for dynamic path matching; finally, by combining runtime call-chain reconstruction with template association, the method achieves automatic identification of function-level mechanism states, effectively resolving the core challenges of “unobservable paths” and “unverifiable configurations” in closed-source environments.

2.1. Unobservability of Runtime Function Call Chains

Determining whether a memory protection mechanism is enabled requires verifying whether the corresponding configuration function (such as usrTextProtect()) is actually invoked at runtime. Since the invocation of such functions directly determines whether the memory protection mechanism takes effect, static analysis alone—such as checking whether a function “exists” or is “visible” in the binary—cannot yield a valid conclusion. However, closed-source VxWorks firmware lacks source code and debugging symbols, so static analysis can only extract function addresses and symbols through disassembly tools such as IDA Pro, without determining whether these functions are executed during system runtime. For example, the text segment write-protection mechanism may be invoked during the kernel initialization phase, but if it is not directly referenced by the main task or exported symbols, static analysis cannot verify its actual execution state.

Furthermore, existing dynamic analysis techniques typically rely on source-level instrumentation or debugging interfaces (such as AFL++ or GDB) [

25,

26], which are unavailable in closed-source environments. The firmware execution process is automatically initiated by the boot image, making it difficult for analysts to inject monitoring points without disrupting the normal execution flow. This limitation prevents effective runtime observation of function call operations, such as ×86 CALL instructions.

Therefore, to achieve behavior-level identification of memory protection states in closed-source scenarios, it is essential to develop a method capable of dynamically monitoring function call chains at runtime, thereby overcoming the invisibility inherent in static analysis paths.

Section 3 introduces a function call chain extraction method based on dynamic instruction translation and static matching, which captures runtime invocation behaviors to address this challenge.

2.2. Static Variability of Memory Protection Mechanism Initialization Paths

The initialization paths of memory protection mechanisms in VxWorks exhibit significant variability across different versions and configurations, which greatly increases the complexity of static analysis. For example, in VxWorks 7, the text segment write-protection mechanism is invoked during startup through the usrTextProtect() function, while other versions or configurations may employ different functions or initialization paths. Moreover, the activation of a mechanism depends not only on whether a function is called but also on parameter configurations and call sequences. For instance, the permission parameters passed to vmStateSet() directly determine whether a code segment is executable. If these parameters are improperly configured, the mechanism may remain inactive even if the function itself is executed.

This variability arises from differences in build macros, component configurations, and Board Support Packages (BSPs), leading to distinct function call paths and configuration logic for the same mechanism across systems. Accurate determination of mechanism states through static analysis therefore requires systematic extraction of these paths and parameter settings. However, relying solely on disassembly or symbol tables is insufficient to reconstruct the full initialization logic, highlighting the need for a structured analytical approach.

Section 4 will address this challenge by parsing official documentation, Component Definition Files (CDFs) [

30], and kernel source code to extract initialization paths and configuration information.

In summary, closed-source VxWorks firmware faces two core challenges in identifying memory protection mechanisms: the unobservability of runtime function call chains and the static variability of initialization paths. The former makes it difficult to confirm runtime invocation behaviors, while the latter complicates the extraction of call paths and configuration logic. Together, these challenges limit the effectiveness of existing analytical approaches. To address these issues, the following chapters will explore two complementary dimensions—dynamic instruction translation and static path extraction—to propose a method capable of accurately determining the activation status of memory protection mechanisms even in the absence of source code.

3. Function Call Chain Extraction Method Based on Dynamic Instruction Translation and Static Matching

In closed-source VxWorks firmware, the activation status of memory protection mechanisms depends on the correct execution of specific function calls (such as

VM_STAT_ESET() [

30,

31,

32]), but due to the lack of source code and debugging information, their runtime call paths are difficult to observe, creating a bottleneck for mechanism identification. To address this, this paper proposes a function call chain extraction method based on dynamic instruction translation and static matching. By enhancing instrumentation capabilities under the ×86 architecture, the method extracts function call chains and key parameters, and combines them with symbol and address mappings exported by static tools (such as IDA Pro) to automatically detect the activation status of memory protection mechanisms.

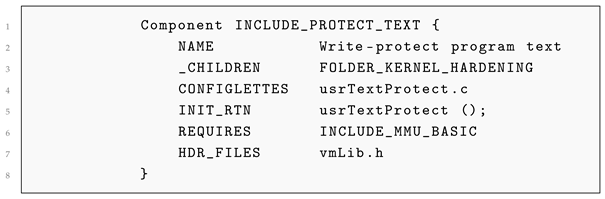

Under the ×86 architecture, function calls follow the standard calling convention: arguments are pushed onto the stack from right to left, the stack pointer ESP points to the top of the stack, the return address is located at ESP, the first argument is at ESP + 4, and subsequent arguments are offset accordingly (e.g., ESP + 8). QEMU’s TCG mechanism translates ×86 function call operations (such as CALL instructions [

33]) into host-executable code. Translation blocks (TBs) [

28] are generated through an intermediate representation (IR) that supports instruction control flow analysis and instrumentation, as illustrated in

Figure 1.

In this method, monitoring logic is inserted during the IR generation stage for the following reasons:

The IR stage has clear semantics, and the target address of function call operations is explicit, facilitating identification;

The IR layer is cross-platform consistent, suitable for lightweight instrumentation;

The instrumentation is non-intrusive, leaving the execution behavior of the target system unmodified and ensuring the integrity of the native runtime environment.

To clarify the timing of insertion of the instrumentation logic relative to TCG optimizations, monitoring hooks are injected after the generation of the intermediate representation (IR) and prior to the TCG optimization phase—including constant folding, register allocation optimization, and dead code elimination. Specifically, within the QEMU source file

target/i386/translate.c [

30,

31,

32], the instrumentation is inserted immediately after the IR for a

CALL instruction is constructed and before the invocation of

tcg_optimize(). A lightweight helper function is invoked via

tcg_gen_helper_call() to record the caller address, callee address, and stack-passed arguments. This strategy ensures that the instrumentation logic remains intact and semantically accurate, as it is not subject to removal or alteration by subsequent compiler-like optimizations.

The monitoring of function calls is implemented in

target/i386/translate.c [

28]. To handle register-based indirect calls in the ×86 architecture (e.g.,

CALL %EAX), the opcode parsing logic is extended: during translation, indirect call variants are identified by inspecting the ModR/M byte (e.g., opcode

0xFF/2). The target register value is dynamically extracted using

tcg_temp_new() and

tcg_gen_mov_tl(), enabling precise capture of the callee address and ensuring comprehensive coverage of all

CALL instruction forms. Within the translation logic for ×86 function calls, the monitoring module captures the caller address (current instruction pointer), callee address (computed from the instruction operand), and stack-based arguments. The monitoring module is designed to be lightweight and efficiently records call relationships, parameter information, and matching results with static templates. It is suitable for various ×86 system configurations and clearly demonstrates the integration process through extended pseudocode (Algorithm 1).

Since the instrumentation is purely observational—introducing no modifications to control flow or memory state—the consistency of the translation block (TB) cache is inherently maintained by QEMU’s built-in mechanisms. In rare cases involving self-modifying code, QEMU automatically triggers TB retranslation via tb_invalidate_phys_page(), ensuring execution correctness without requiring additional intervention from the monitoring framework.

For compiler-inlined functions—which lack explicit CALL instructions and thus cannot be directly observed via dynamic instrumentation—a hybrid mitigation strategy is adopted. High-frequency inlined functions (e.g., lightweight wrappers around vmStateSet) are pre-identified through static analysis, and their semantic effects are inferred during call-chain reconstruction based on control-flow context. Unidentified inlined paths are flagged as “potentially unobserved calls,” and their validation is recommended through complementary techniques such as symbolic execution or manual disassembly to ensure analysis completeness.

To clearly illustrate the implementation concept of the proposed method, Algorithm 1 presents the pseudocode for extracting function call chains and their associated parameters. The call chain extraction employs a dynamic linked list to record the relationship between callers (current instruction pointers) and callees (target function addresses). Structured call paths are constructed upon function invocation events—such as ×86

CALL instructions—and redundant call nodes are merged through path compression to minimize memory overhead, enabling real-time call graph reconstruction. Parameter extraction retrieves critical arguments (e.g., permission flags) directly from the runtime stack, supports multi-argument scenarios, and incorporates a stack address validity verification mechanism to ensure robustness and portability across diverse ×86 system configurations.

| Algorithm 1 Instrumentation of CALL Instructions and Call Chain Monitoring |

- 1:

function TRANSLATECALL(context, instruction) - 2:

- 3:

- 4:

MONITORCALL(, , context.stack) - 5:

EXECUTEORIGINALCALL(context, ) - 6:

end function

- 7:

function MONITORCALL(caller_addr, target_addr, stack) - 8:

APPENDTOCALLCHAIN(, ) - 9:

READSTACK(stack, offset = 8) - 10:

LOGPARAM() - 11:

if INVALIDSTACKACCESS(stack) then - 12:

LOGERROR(“Invalid stack access”) - 13:

end if - 14:

LOOKUP_SYMBOL() - 15:

if then - 16:

if then - 17:

MARK_ENABLED(“Text Segment Write Protection”) - 18:

else if then - 19:

MARK_DISABLED(“Text Segment Write Protection”) - 20:

end if - 21:

end if - 22:

COMPRESS_CALL_CHAIN - 23:

end function

|

The extended pseudocode demonstrates how dynamically captured stack parameters—such as the permission flag MMU_ATTR_SUP_RW—are directly linked to static templates: by symbolically mapping runtime addresses to function names and comparing the extracted parameter values against expected configurations, the system determines whether a protection mechanism is enabled. This design ensures that the integration process is transparent, verifiable, and grounded in concrete runtime evidence.

The extraction of function call chains uses a dynamic linked list to store the relationships between callers (current instruction pointer) and callees (target function addresses). Structured call paths are generated based on function call operations (such as ×86 CALL instructions), and duplicate call nodes are merged through path compression to reduce storage overhead, enabling real-time reconstruction. Parameter extraction reads key parameters (such as permission flags) from the stack, supports multi-parameter scenarios, and includes an error-checking mechanism to verify stack address validity, ensuring robustness and applicability across various ×86 system configurations.

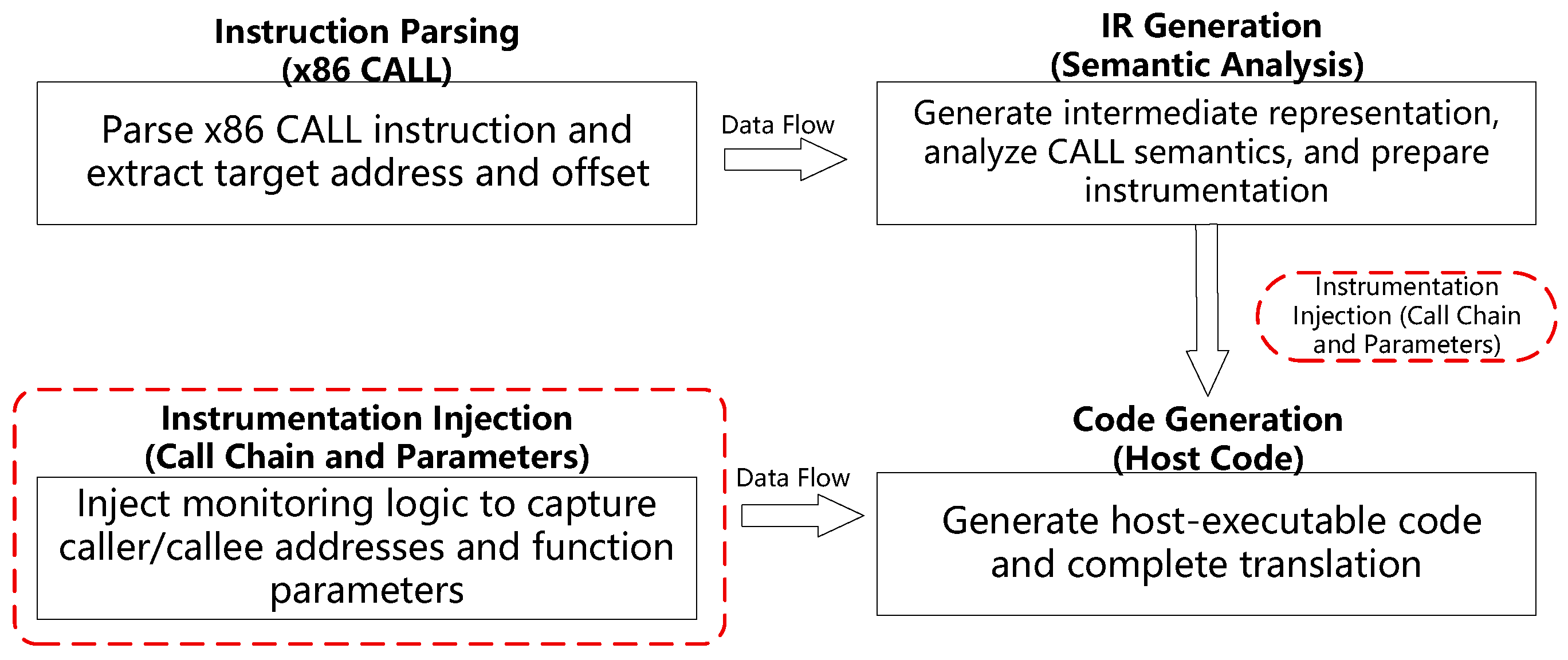

To enable function-level semantic reconstruction, the method leverages a static address-to-function-name mapping table—extracted offline using reverse engineering tools—to resolve runtime addresses captured by QEMU into human-readable function symbols. This allows the identification of function-level caller–callee relationships between the current instruction pointer (caller) and the target function address (callee), thereby constructing a structured, semantically meaningful call chain.

Specifically, dynamically captured virtual addresses are integrated with the precomputed static symbol map via binary search for efficiency. Once resolved to function names, these calls are matched against predefined templates using pattern-based alignment. Concurrently, parameter values—such as permission flags—are directly compared against expected entries in the templates; for instance, the presence of MMU_ATTR_SUP_RW indicates that the corresponding protection mechanism is enabled.

This integration ensures seamless alignment between runtime execution behavior and the static semantic model, significantly enhancing detection accuracy. The symbol resolution process begins by extracting the address–function mapping from the firmware binary, sorting it by address, and then applying binary search to efficiently annotate both caller and callee addresses observed during QEMU instrumentation. The resulting symbolized call chain provides a clear, interpretable trace for template matching and validation, as illustrated in

Figure 2.

To further clarify the relationship between raw stack data and semantic configuration flags, we take parameter-controlled memory protection mechanisms (e.g., data segment non-executability) as an example. During QEMU’s TCG translation, operations such as tcg_gen_ld_tl() dynamically capture runtime parameters (e.g., protFlags or param_perm) from stack offsets (e.g., ESP+8 on ×86). This captured value is then precisely compared against semantically defined flags in the static template—such as MMU_ATTR_SUP_RW (denoting supervisor-mode read-write but non-executable permissions) or MMU_ATTR_SUP_RWX (indicating executable permissions). If the observed value matches MMU_ATTR_SUP_RW, the protection mechanism is deemed enabled; if it matches an executable flag like MMU_ATTR_SUP_RWX, the mechanism is considered disabled. This dynamic verification approach, through real-time semantic interpretation of runtime parameters, effectively overcomes the fundamental limitation of pure static analysis—which cannot determine actual runtime configuration states—and thereby enables accurate and robust validation of memory protection policies in closed-source firmware environments without source code or debugging symbols.

Through the aforementioned approach, the system can observe function call behavior and extract its semantic meaning at runtime—without relying on debugging symbols—thereby ensuring both accuracy and generality in subsequent call-path matching and mechanism determination.

4. Static Analysis of VxWorks 7 Memory Protection Mechanisms and Construction of Call Chain Information

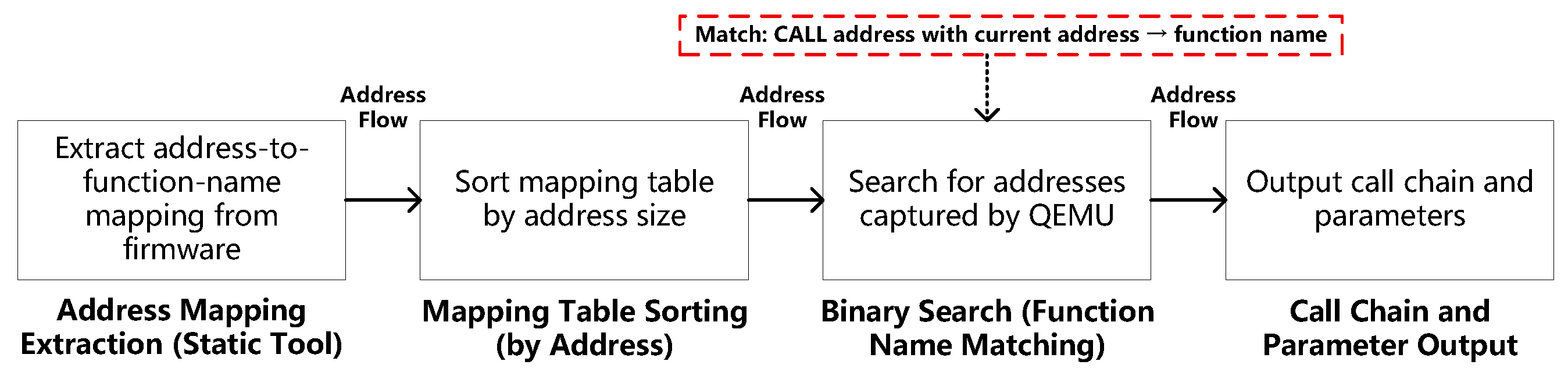

To support dynamic monitoring of memory protection mechanisms in a closed-source environment, this paper extracts function call chains and permission configuration information for VxWorks 7 under the ×86 architecture through static analysis. This chapter analyzes six representative memory protection mechanisms (text segment write protection, exception vector table protection, task stack overflow protection, task stack non-executable protection, interrupt stack protection, and data segment non-executable protection) using the following steps:

Review official documentation: Consult the VxWorks 7 Kernel Programmer’s Guide and Kernel API Reference to identify component macros and functional descriptions of the memory protection mechanisms;

Parsing CDF project configuration files: Automated scripts are employed to scan the INIT_RTN field within CDF files to identify the initialization functions of each protection mechanism and their associated dependencies;

Analyze kernel source code: Trace the call paths of the initialization functions and their permission configuration logic to extract function call chains and parameter information.

To demonstrate the automation and reproducibility of this process, a custom Python script is developed to enable automated parsing of CDF files. Specifically, the script systematically scans all component definition files in the official VxWorks 7 CDF repository, employs regular expressions to match CDF syntax—e.g., r’INIT_RTN\s*=\s*“([⌃”]+)”’—to extract initialization entry points, and cross-references component macros (e.g., INCLUDE_PROTECT_TEXT) with their dependencies. Furthermore, the script integrates macro descriptions from official documentation and call paths from kernel source code to construct structured templates. This automated tool ensures an efficient, consistent extraction process and supports batch processing of CDF files across different VxWorks versions.

Figure 3 illustrates the static analysis workflow, encompassing document review, CDF parsing, and source code tracing, resulting in the generation of structured function call chains and permission configuration information.

By reviewing the official VxWorks 7 documentation, six representative memory protection mechanisms were identified: text segment write protection, exception vector table protection, task stack overflow detection, task stack non-executable protection, interrupt stack protection, and data segment non-executable protection. The activation of these mechanisms depends on specific component macros and initialization functions, and their configuration information is obtained from the official documentation and CDF (Component Definition File) project configuration files.

Taking the text segment write protection mechanism as an example, the analysis process is described in detail, followed by a brief overview of the call chain construction results for the other mechanisms. To illustrate the output of the automated parsing, the following example presents a typical call-chain template in JSON format, extracted by the script from the CDF and source code of the INCLUDE_PROTECT_TEXT component:

{

“mechanism”: “Text Segment Write Protection”,

“component_macro”: “INCLUDE_PROTECT_TEXT”,

“type”: “function-driven”,

“init_rtn”: “usrTextProtect()”,

“call_chain”: [

“usrRoot()”,

“usrTextProtect()”,

“vmTextProtect()”,

“vmStateSet()”

],

“parameters”: {

“vmStateSet”: {

“permission”: “read-only”,

“segment”: “.text”

}

},

“dependencies”: [“INCLUDE_MMU_BASIC”]

}

This template exemplifies the structured output generated by the script and can be directly consumed by the subsequent dynamic matching module, ensuring reproducibility and rigor in the analysis.

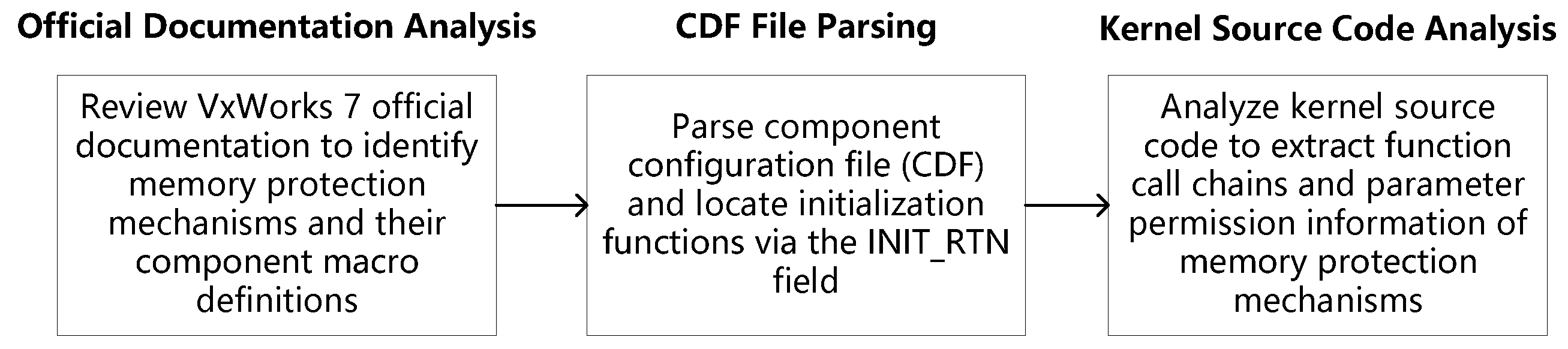

According to the VxWorks 7 official documentation, text segment write protection is controlled by the component INCLUDE_PROTECT_TEXT, which sets the memory attributes of the .text segment to read-only to prevent runtime modification. The corresponding CDF file [

30,

31,

32] is defined in Listing 1:

| Listing 1. CDF definition of INCLUDE_PROTECT_TEXT. |

![Electronics 14 04382 i001 Electronics 14 04382 i001]() |

By parsing the INIT_RTN field, the initialization function usrTextProtect() is located, which is called by usrRoot() during the kernel startup phase. Source code analysis indicates that usrTextProtect() verifies whether the .text segment resides in local memory, and if the condition is met, it calls vmTextProtect() to set the segment as read-only. The pseudocode is as follows (Algorithm 2):

| Algorithm 2 Text Segment Write-Protection Logic in usrTextProtect() |

- 1:

function USRTEXTPROTECT - 2:

if then - 3:

- 4:

else - 5:

- 6:

end if - 7:

VMTEXTPROTECT() - 8:

end function

|

The extracted call chain is usrRoot() → usrTextProtect() → vmTextProtect() → vmStateSet(), with the core parameter being the read-only permission flag.

Through static analysis, the six memory protection mechanisms are categorized into function-driven and parameter-controlled types. The call chains and permission configuration information for these mechanisms are summarized below:

Text Segment Write Protection INCLUDE_PROTECT_TEXT

Category: Function-driven.

Implementation: Enabled during kernel startup via usrRoot() →usrTextProtect()→ vmTextProtect(), which sets the .text segment to read-only.

Text Segment Write Protection INCLUDE_PROTECT_TEXT

Category: Function-driven.

Implementation: Enabled during kernel startup via usrRoot() →usrTextProtect()→ vmTextProtect(), which sets the .text segment to read-only.

Exception Vector Table Write Protection INCLUDE_PROTECT_VEC_TABLE

Category: Function-driven.

Implementation: usrRoot() calls intVecTableWriteProtect(), which applies write-protect attributes to the vector table region.

Task Stack Overflow Protection INCLUDE_PROTECT_TASK_STACK

Category: Function-driven.

Implementation: Guard pages are enabled by taskStackGuardPageEnable() during task creation or system initialization.

Task Stack Non-Executable Protection INCLUDE_TASK_STACK_NO_EXEC

Category: Function-driven.

Implementation: Stack memory is marked non-executable via taskStackNoExecEnable().

Interrupt Stack Overflow Protection INCLUDE_PROTECT_INTERRUPT_STACK

Category: Function-driven.

Implementation: Reuses the vector table protection mechanism: intVecTableWriteProtect() is applied to the interrupt stack region.

Data Segment Non-Executable Protection INCLUDE_DATA_NO_EXEC

Category: Parameter-controlled.

Implementation: Controlled by the global flag mmuDataNoExec. When set to TRUE, unldByModuleId() configures memory with MMU_ATTR_SUP_RW (non-executable) instead of MMU_ATTR_SUP_RWX.

Function-driven mechanisms include text segment write protection, exception vector table protection, task stack overflow protection, task stack non-executable protection, and interrupt stack protection. These mechanisms are initialized through explicit function call chains invoked by usrRoot().

Figure 4 illustrates the initialization logic of function-driven mechanisms.

Parameter-controlled mechanism: Data segment non-executable protection is controlled by the global variable mmuDataNoExec and sets memory attributes in the module unload function unldByModuleId() based on the permission parameter protFlags. By capturing stack parameters through QEMU, the protFlags value can be dynamically verified to infer the state of mmuDataNoExec: if it is read_write, the mechanism is enabled; if it is read_write_execute, the mechanism is not enabled. The logic for enforcing data segment non-executable protection in

unldByModuleId() is implemented as shown in Algorithm 3:

| Algorithm 3 Data Segment Non-Executable Protection Logic in unldByModuleId() |

- 1:

function UNLDBYMODULEID(segment_id, size) - 2:

if MMUDATANOEXEC then - 3:

VMSTATESET(segment_id, size, MMU_ATTR_SUP_RW) - 4:

else - 5:

VMSTATESET(segment_id, size, MMU_ATTR_SUP_RWX) - 6:

end if - 7:

end function

|

This chapter extracts the function call chains and permission configuration information of VxWorks 7 memory protection mechanisms through static analysis, providing structured templates for dynamic monitoring in a closed-source environment. Function-driven mechanisms are automatically initialized through explicit call chains, while parameter-controlled mechanisms have their activation status verified by dynamically capturing permission parameters. Combined with the dynamic instrumentation method presented in

Section 3, this enables accurate identification of memory protection mechanisms.

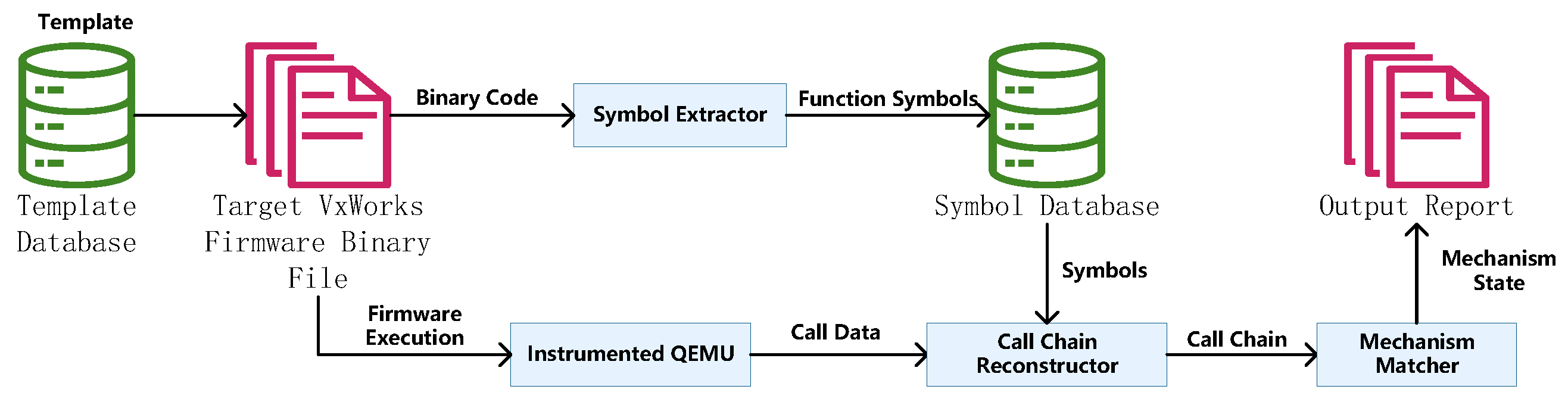

5. System Design and Experimental Evaluation

To validate the effectiveness of the proposed memory protection mechanism detection method based on dynamic instruction translation in closed-source VxWorks 7 firmware, this chapter presents the design of a prototype system and its experimental evaluation. The system combines static template extraction with dynamic QEMU instrumentation to automatically identify six types of memory protection mechanisms: text segment write protection, exception vector table protection, task stack overflow detection, task stack non-executable protection, interrupt stack protection, and data segment non-executable protection.

5.1. System Design

The system adopts a modular architecture, integrating static analysis (template database construction) and dynamic monitoring (QEMU instrumentation and call chain reconstruction). It takes the target firmware binary as input and outputs the activation status of memory protection mechanisms. The system architecture is shown in

Figure 5.

The static analysis module is responsible for constructing a template database that represents the expected function call chains and permission configurations for each memory protection mechanism. This module processes VxWorks 7 official documentation, Component Definition Files (CDFs), and kernel source code to extract the necessary information.

First, by reviewing official documentation (such as the VxWorks 7 Kernel Programmer’s Guide and Kernel API Reference), the module identifies the components and macros associated with each protection mechanism. For example, text segment write protection is controlled by the INCLUDE_PROTECT_TEXT component. Next, the CDF files are parsed to locate the initialization functions for these components. The INIT_RTN field in the CDF specifies the functions called during system startup to initialize the components. For instance, the INCLUDE_PROTECT_TEXT component uses usrTextProtect() as its initialization function.

Then, by analyzing the kernel source code, the call paths from the initialization functions to the functions that actually set memory protection (such as vmStateSet()) are traced. This process involves identifying the sequence of function calls and extracting the permission parameters passed to these functions to define memory attributes. The extracted information is organized into templates for each mechanism, including the function call chain and expected permission parameters. These templates are stored in JSON format in the database for use by the subsequent mechanism matching module. The symbol extraction module extracts function symbols from the target firmware binary to establish a mapping between function names and their addresses. This mapping is crucial for interpreting runtime data captured during emulation. The module uses disassembly tools such as IDA Pro to analyze the binary, extract the symbol table, and generate a database pairing function names with their corresponding addresses. This database enables the conversion of runtime addresses into meaningful function names.

The dynamic monitoring module is the core of the system, responsible for capturing function calls and their parameters during firmware emulation. This functionality is implemented by instrumenting QEMU’s Tiny Code Generator (TCG), specifically targeting ×86 CALL instructions. In particular, the CALL instruction translation logic in target/i386/translate.c is modified to insert hooks that capture the caller address (current instruction pointer), callee address (target function address), and stack parameters. The instrumentation is designed to be lightweight to minimize the impact on emulation performance. The captured data, including caller–callee pairs and parameters, is recorded for further processing by the call chain reconstruction module. The pseudocode provided in

Section 3 details the instrumentation logic.

The call chain reconstruction module processes the runtime data captured by the dynamic monitoring module to build structured call chains. This process involves mapping the captured addresses to function names using the symbol database and constructing sequences of function calls. First, the symbol database is queried to convert caller and callee addresses into function names. Then, a call graph is constructed based on the call relationships, where nodes represent functions and edges represent calls between functions. To optimize storage and processing efficiency, path compression is used to merge duplicate call sequences. Additionally, captured key parameters are associated with the relevant functions in the call chain, which is particularly useful for mechanisms that depend on specific parameter values.

The mechanism-matching module compares the reconstructed call chains with the static templates to determine whether a specific memory protection mechanism is enabled. For function-driven mechanisms, the module checks whether the call chain from the initialization function (e.g., usrRoot()) to the function that sets protection (e.g., vmStateSet()) matches the template. A successful match indicates that the mechanism is enabled. For parameter-controlled mechanisms (such as data segment non-executable protection), the module verifies both the call chain and the captured parameters against the template. For example, it checks whether the protFlags parameter in vmStateSet() matches the expected value (e.g., MMU_ATTR_SUP_RW when protection is enabled). An efficient pattern-matching algorithm is used to compare call chains and parameters, ensuring high detection accuracy.

The system integrates these modules into a coordinated workflow. The process begins with static analysis to build the template database, while the symbol extraction module generates a symbol database from the firmware binary. During emulation, the instrumented QEMU captures runtime data, which is then processed by the call chain reconstruction module using the symbol database. The reconstructed call chains are sent to the mechanism matching module for comparison with the templates, producing the final detection results. This modular design ensures that each component efficiently handles the output of the previous stage, forming a smooth and effective detection workflow.

5.2. Experimental Evaluation

This section validates the effectiveness of the proposed memory protection mechanism identification method based on dynamic instruction translation in closed-source VxWorks 7 firmware through system-level experiments. As this method represents the first automated detection approach specifically targeting VxWorks memory protection mechanisms, there are no directly comparable methods for VxWorks. Therefore, the experiments use self-compiled firmware samples to evaluate accuracy, false positive rate, false negative rate, execution time, and memory overhead. The experiments focus on representative configurations and are extended to comprehensive combinations to assess the robustness of the method.

5.2.1. Experimental Design

The experimental design covers all combinations of the six memory protection mechanisms (2

= 64 configurations), including single-mechanism enablement (6 groups), two-mechanism combinations (C(6,2) = 15 groups), three-mechanism combinations (C(6,3) = 20 groups), four-mechanism combinations (C(6,4) = 15 groups), five-mechanism combinations (C(6,5) = 6 groups), full enablement (1 group), and full disablement (1 group). To validate representative scenarios, three typical configurations were selected, with 10 samples per configuration, totaling 30 samples. The focus is on the following:

Sample A: All mechanisms disabled, component macros set to FALSE, with no corresponding call chains;

Sample B: Text segment write protection enabled (call chain: usrRoot() → usrTextProtect() → vmTextProtect() → vmStateSet(), parameter read_only) and task stack overflow detection enabled (usrRoot() → taskStackGuardPageEnable());

Sample C: All six mechanisms enabled, covering the call chains and parameters listed in

Table 1 (e.g., MMU_ATTR_SUP_RW).

All samples were compiled using Wind River Workbench based on the standard VxWorks 7 development process, representing industrial scenarios. It should be noted that VxWorks is a mainstream real-time operating system widely used in high-assurance domains such as defense, aerospace, and critical infrastructure. Due to national security and commercial confidentiality concerns, authentic VxWorks firmware images are rarely available in the public domain, and no open-source firmware suitable for academic evaluation exists. Therefore, this study employs Wind River Workbench—the official VxWorks integrated development environment (IDE)—together with standard Board Support Packages (BSPs) to build custom firmware images. The compilation strictly follows real-world industrial development practices, ensuring that the generated firmware matches production systems in terms of build configuration, compiler flags, and memory layout. By exhaustively evaluating all 64 combinations of protection mechanisms (enabled/disabled), the experimental setup comprehensively covers realistic deployment scenarios and exhibits strong representativeness and credibility with respect to actual industrial configurations. Symbol information was extracted using IDA Pro. The experimental environment employed QEMU 5.0.0 (×86 emulation) with hardware configured as Intel Core i7-11800H (Dell Inc., Beijing, China), with 32 GB of memory, running Ubuntu 20.04.

5.2.2. Experimental Analysis

To comprehensively evaluate the performance of the method, the following key metrics are defined:

Accuracy: The proportion of detection results that match the actual configuration, reflecting the reliability of the method;

False Positive Rate: The proportion of mechanisms that are not enabled but incorrectly detected as enabled, measuring the tendency for misclassification;

False Negative Rate: The proportion of enabled mechanisms that are not detected, assessing the completeness of detection.

The experiments were conducted on the three sample groups, with the results as follows:

Sample A (mechanisms disabled): The method did not detect any protection mechanism calls, confirming reliability with no false positives.

Sample B (partially enabled mechanisms): The method accurately captured the call chains and parameters for text segment write protection and task stack overflow detection, correctly distinguishing between enabled and disabled mechanisms.

Sample C (all mechanisms enabled): The method fully captured the call chains and parameters defined in

Table 1 demonstrating adaptability under complex configurations.

5.2.3. Experimental Summary

The three sample experiments show that the method achieves 100% accuracy across different configurations, with both false positive and false negative rates at 0%. To verify generality, extended testing covering all 64 combinations of mechanisms was conducted, yielding consistent results of 100% accuracy and 0% false positives/negatives.

To further strengthen the credibility of the results, this work includes a performance evaluation: in a QEMU 5.0.0 (×86) environment, enabling instrumentation increases system boot time by an average of 7.2% (from 12.4 s to 13.3 s) and memory consumption by approximately 4.8 MB (<3%), demonstrating the low overhead of the proposed approach. The observed 100% accuracy stems from the deterministic nature of the protection mechanism activation logic: function-driven mechanisms rely on exact matches of explicit call chains, while parameter-controlled mechanisms depend on precise comparisons of permission flags. By combining automatically generated templates with runtime capture, the method eliminates ambiguous states in theory. Consequently, achieving zero false positives and zero false negatives in a controlled environment is both reasonable and expected.

The samples follow the standard VxWorks development process, ensuring industrial applicability. Test cases and configuration files have been open-sourced [

34], supporting community verification and applications in aerospace and industrial control domains.

6. Conclusions

This paper presents a dynamic binary translation-based approach for detecting memory protection mechanisms in closed-source VxWorks firmware. By integrating static template extraction with dynamic function call monitoring, the method achieves high-precision identification of the activation status of multiple memory protection mechanisms—without requiring source code or debug symbols.

In the methodology, we first leverage official documentation, Component Definition Files (CDFs), and kernel source code to automatically extract initialization routines, call chains, and permission configurations for each protection mechanism, thereby constructing a structured static template database. During dynamic execution, we extend QEMU’s TCG translation pipeline to perform lightweight instrumentation on ×86 CALL instructions, enabling real-time capture of complete function call paths and their arguments. Finally, the system matches the observed runtime call behavior against the static templates to accurately determine whether each memory protection mechanism is enabled.

It is important to emphasize that the core contribution lies in the generic monitoring framework at the QEMU layer, not in targeting a specific VxWorks version. Although our experiments use VxWorks 7—as the most widely deployed and representative release in high-assurance domains such as defense and aerospace—the underlying memory protection mechanisms exhibit strong backward compatibility across VxWorks 5, 6, and 7. Moreover, as long as the target firmware can be executed in QEMU (e.g., ×86-based VxWorks 5–7 images), our method applies directly. This ensures the framework’s portability and practical relevance in real-world scenarios.

Experimental results demonstrate that, across 64 distinct firmware configurations, our approach achieves 100% detection accuracy for six representative memory protection mechanisms—including text segment write protection, exception vector table protection, task stack overflow detection, non-executable task stack, interrupt stack protection, and non-executable data segment—with zero false positives and zero false negatives. The runtime overhead is minimal: system boot time increases by only ∼7.2% (from 12.4 s to 13.3 s), and memory consumption rises by less than 3% (∼4.8 MB), confirming the method’s correctness, robustness, and practicality.

This work establishes a general and automated analysis paradigm for identifying security mechanisms in closed-source embedded systems—particularly industrial control and aerospace firmware that lacks symbol information. Future work will focus on three directions: (1) extending the detection framework to other embedded architectures such as ARM and PowerPC; (2) incorporating runtime behavioral analysis on top of mechanism detection to identify protection bypasses or potential exploit scenarios; (3) combining symbolic execution with binary semantic modeling to enable automated reverse engineering of more complex security mechanisms.

In summary, the proposed approach not only provides an effective tool for security assessment of VxWorks systems but also lays a scalable, reproducible foundation for memory protection verification in closed-source real-time operating systems.