Data Secure Storage Mechanism for Trustworthy Data Space

Abstract

1. Introduction

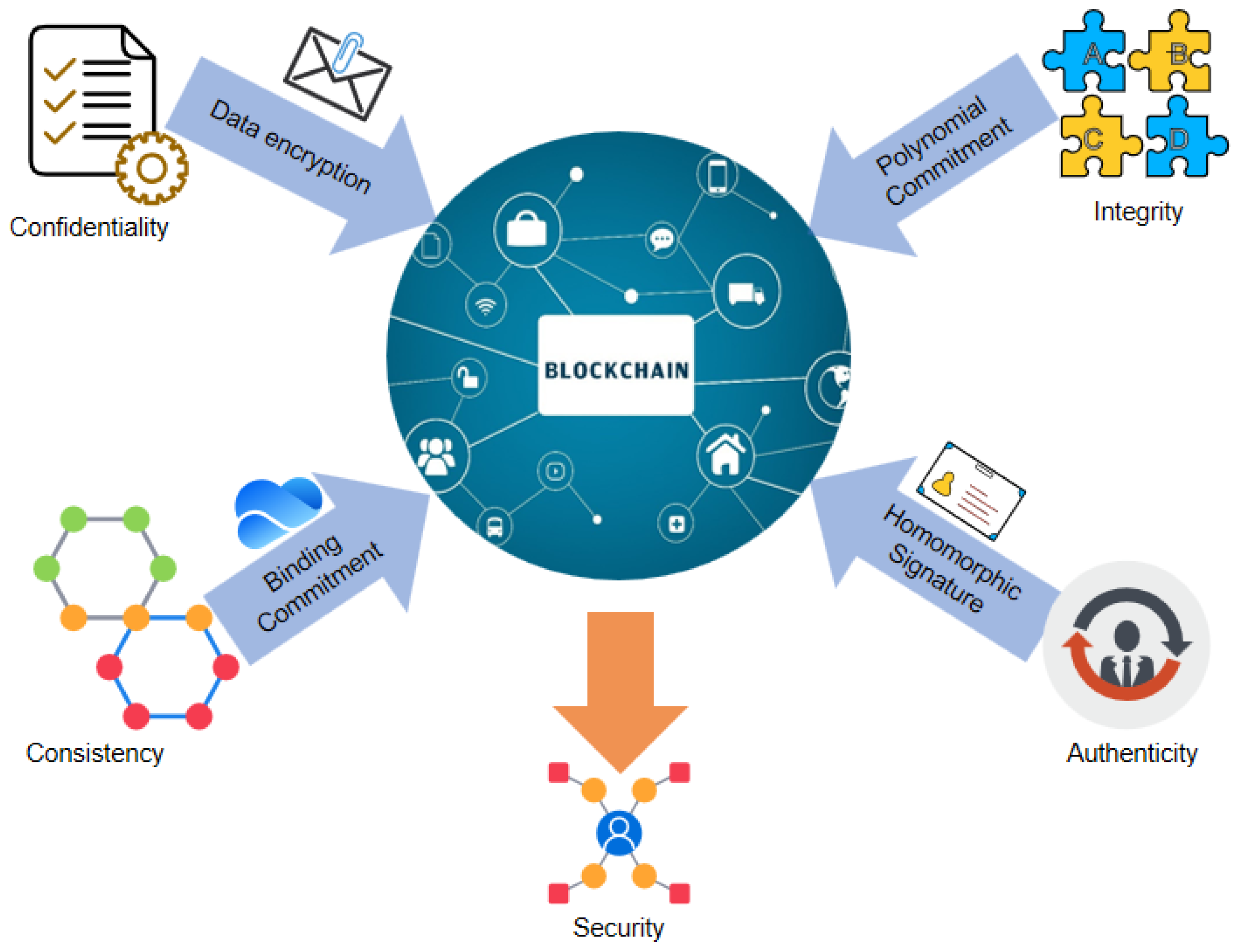

- This paper proposes a blockchain-based data security storage framework for trustworthy data space. In this framework, metadata is stored on-chain and business data is stored off-chain. Furthermore, data integrity and consistency are verified by querying one or more positional indexes stored in polynomial commitment on-chain.

- A data modification function is designed to record the update status of data, which achieves traceability in the data storage mechanism.

- To ensure data authenticity in the trustworthy data space, the paper verifies the identity of data senders. Combined with homomorphic signature technology, the authenticity of data sources can be verified without exposing original data.

2. Related Work

2.1. Secure Data Storage for Trustworthy Data Space

2.2. Data Storage Based on Blockchain

3. Secure Requirement of Data Storage for Trustworthy Data Space

4. Storage Security Guarantee Mechanism Based on Polynomial Commitment for Trustworthy Data Space

4.1. Framework of Data Security Storage for Trustworthy Data Space

4.2. Secure Storage Solution Based on Polynomial Commitment for Trustworthy Data Space

- Setup : The data owner needs to store a string of messages, and the smart contract executor runs the algorithm. After the execution is completed, the smart contract outputs PK, which is used to generate commitment and query messages on the blockchain.

- Commit : The data owner uploads the message, the smart contract executor encrypts the message according to the selected polynomial and stores the encrypted value off-chain according to the index, and the generated commitment value is stored on the chain.

- Query : The data verifier provides the index i to be queried, and the smart contract generates auxiliary parameters and auxiliary polynomials based on the previously selected polynomial and off-chain data.

- Verify : Substitute the generated parameters to determine whether the commitment value has been tampered with.

4.3. Homomorphic Signature Based on Polynomial Function

- Setup : The data owner generates and . The public key defines the message space M, the signature space and the valid functions set .

- Sign : The data owner utilizes the key , the label , n, the message and the index , and generates the signature .

- Verify : The data verifier employs the public key , the label , n, the message , the signature and the function to authenticate the message sender’s identity, then outputs 0 (reject) or 1 (accept).

- Evaluate : The data owner can obtain the public key , the label , n, the function and the signature tuple , aggregate the signatures of different messages, and output the signature .

- Setup . Provide the (security parameter) and the k (maximum dataset size) as inputs, and then execute the subsequent actions:

- i.

- Select n as an irreducible polynomial of degree, , . Let be embedded into by coefficient embedding. Let be the lattice associated with .

- ii.

- Run the PrincGen algorithm twice with inputs F and n to generate two distinct principal degree prime ideals and of R, along with their respective generators and .

- iii.

- Let T be the basis of u, v, .

- iv.

- The parameter is defined, with integers and chosen.

- v.

- A hash function is employed, treated as a random oracle.

- vi.

- The keys are generated as for the public key and for the secret key.

The public key specifies the following system parameters:- Messages are elements of , while signatures take the form of compact vectors from R.

- The permitted function class F includes all polynomials from satisfying coefficients ranging from to y, a maximum degree of d, and no constant term (Note: The parameter y is employed solely within the verification process).

- Consider the combinatorial parameter . Let enumerate all non-constant monomials with total degree , ordered lexicographically. Each polynomial function admits representation: , where coefficients are interpreted as integers in . The canonical encoding is .

- For hash function operating on encoded polynomial :(a) Generate k field elements , compute .(b) Evaluate .

- Sign . Input the secret key , n-bit tag , a message in prime field and an index i, and perform the following operations:

- i.

- Derive through hash computation.

- ii.

- Construct polynomial satisfying , αi.

- iii.

- Generate signature

- Verify . For inputs , , , signature , and function , accept (output 1) if all conditions hold, otherwise reject (output 0):

- (a)

- Norm constraint .

- (b)

- Message check .

- (c)

- Authentication check .

- Evaluate . Processing inputs , , encoded as and a signature , and perform the following:

- i.

- Elevate to via .

- ii.

- Return the evaluation .

4.4. Security Analysis

5. Performance of Proposed Scheme

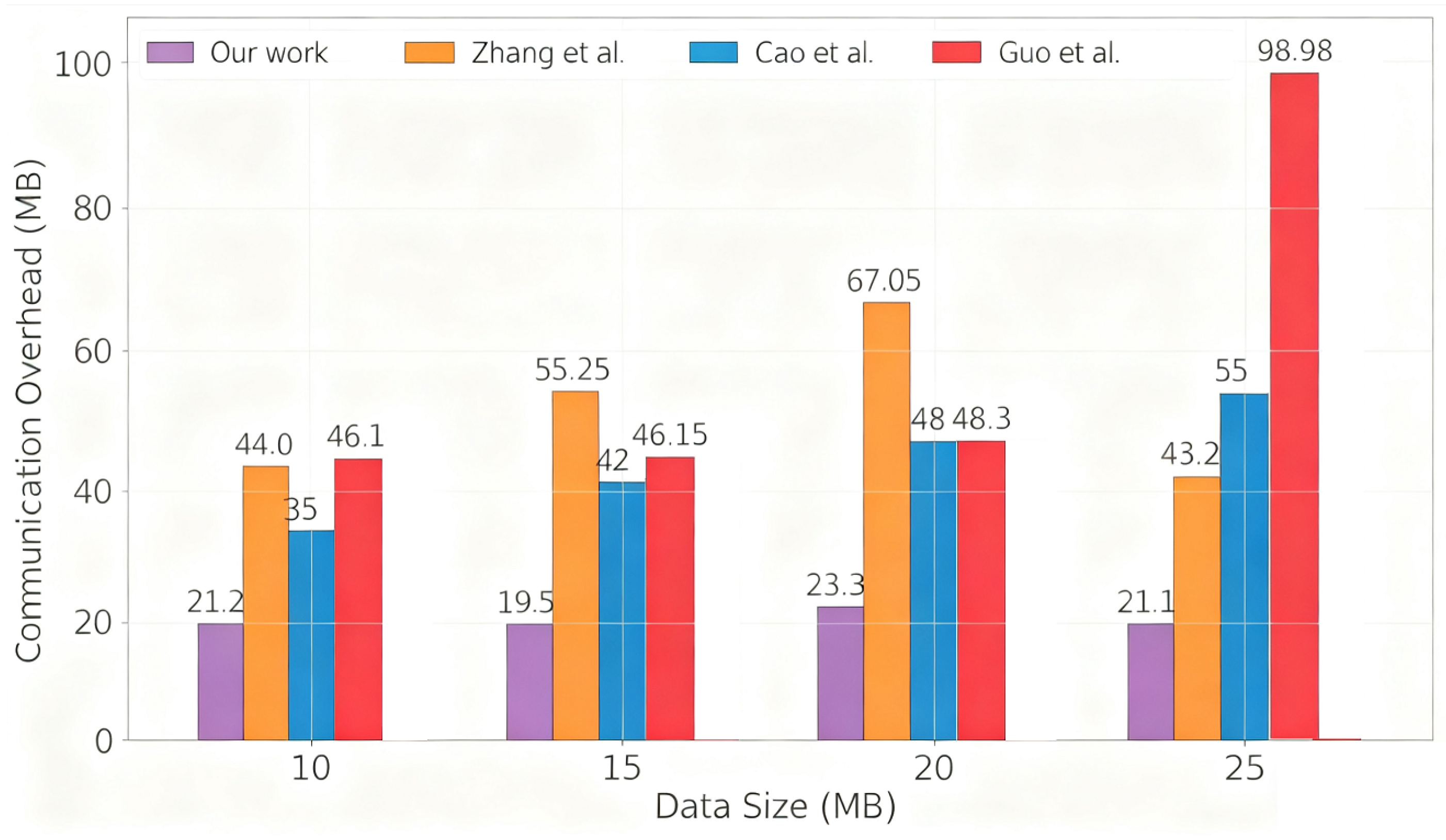

5.1. Communication Overhead

5.2. Storage Overhead Evaluation

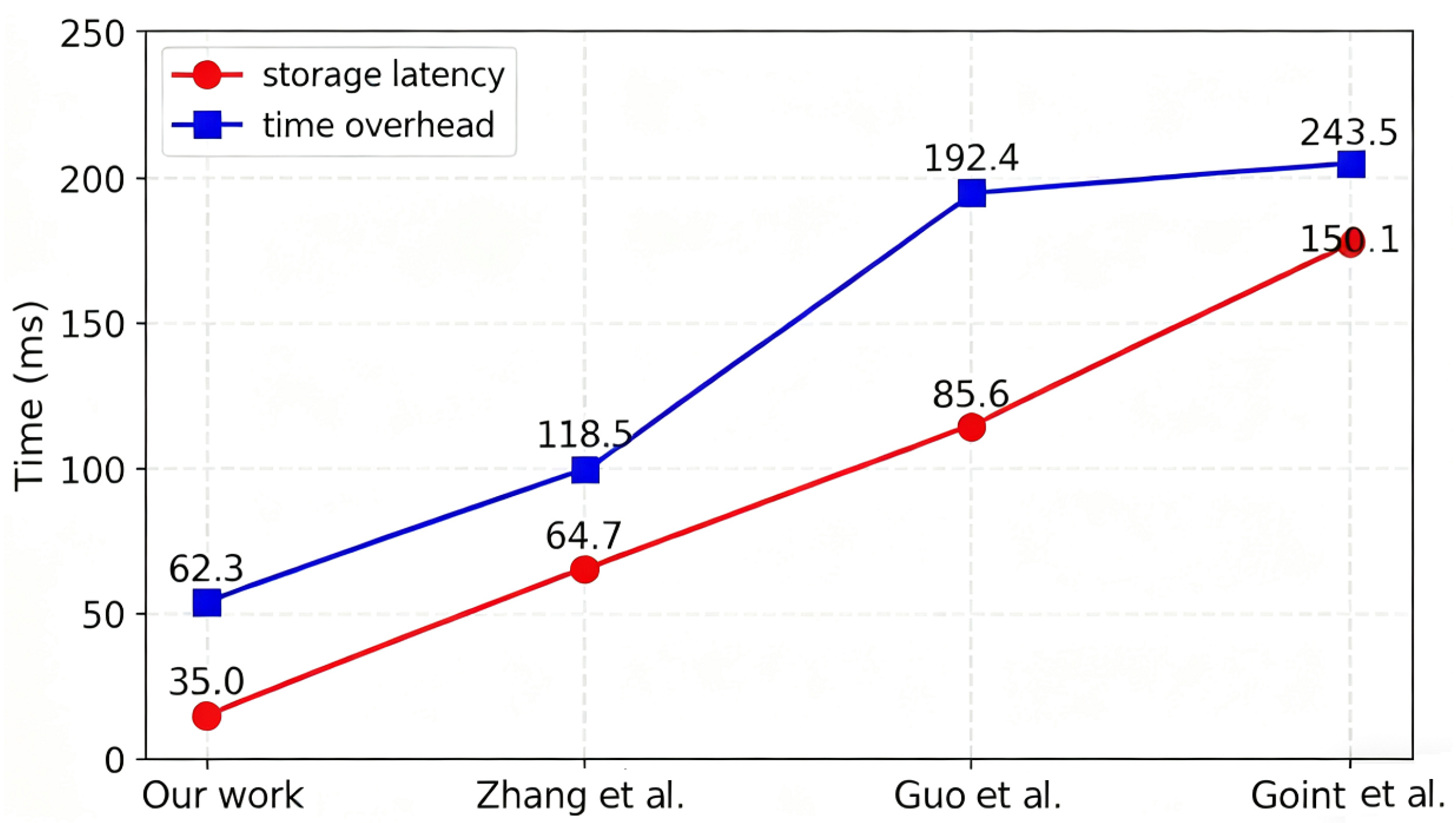

5.3. Off-Chain Time Cost

5.4. On-Chain Time Cost

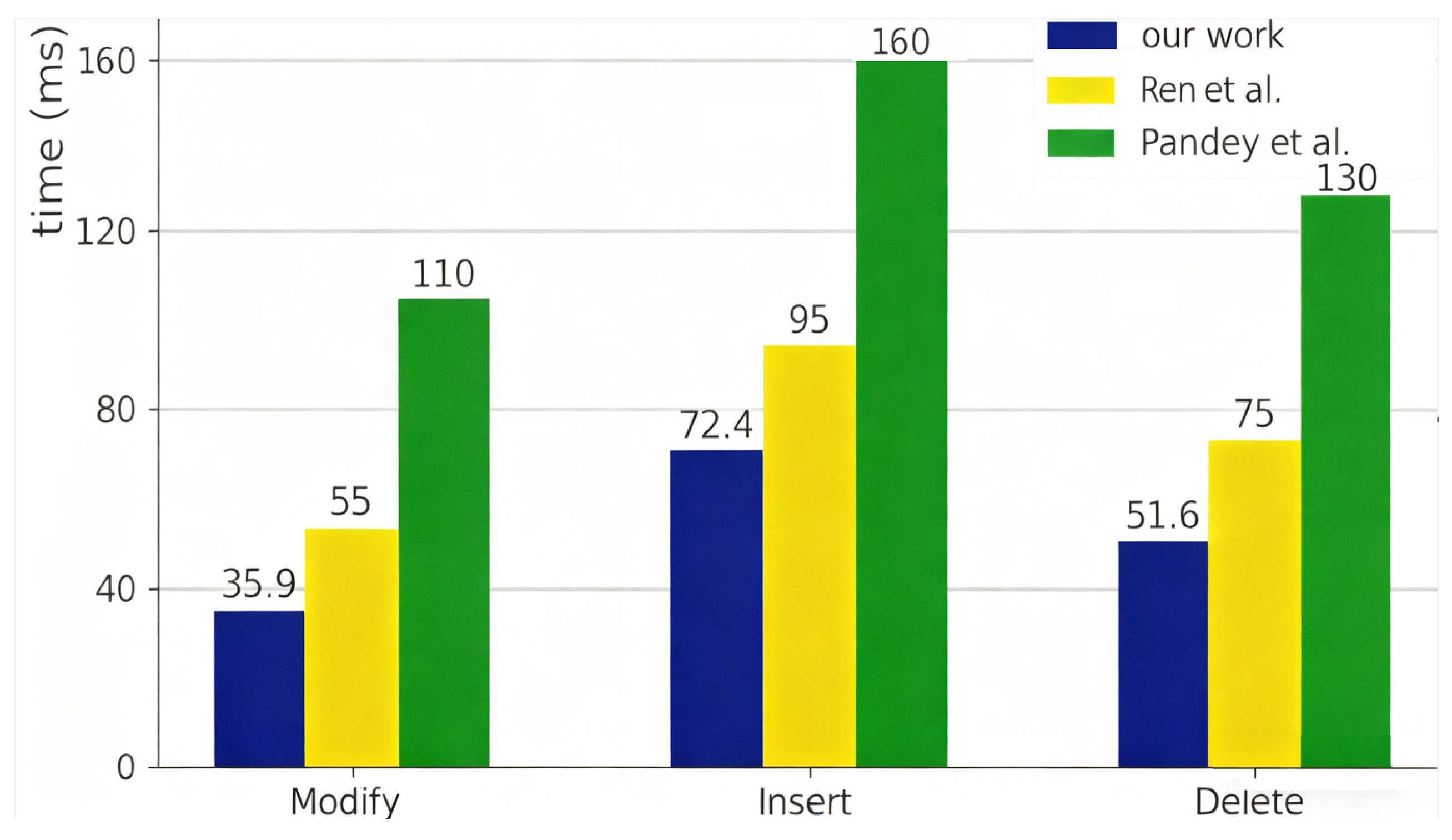

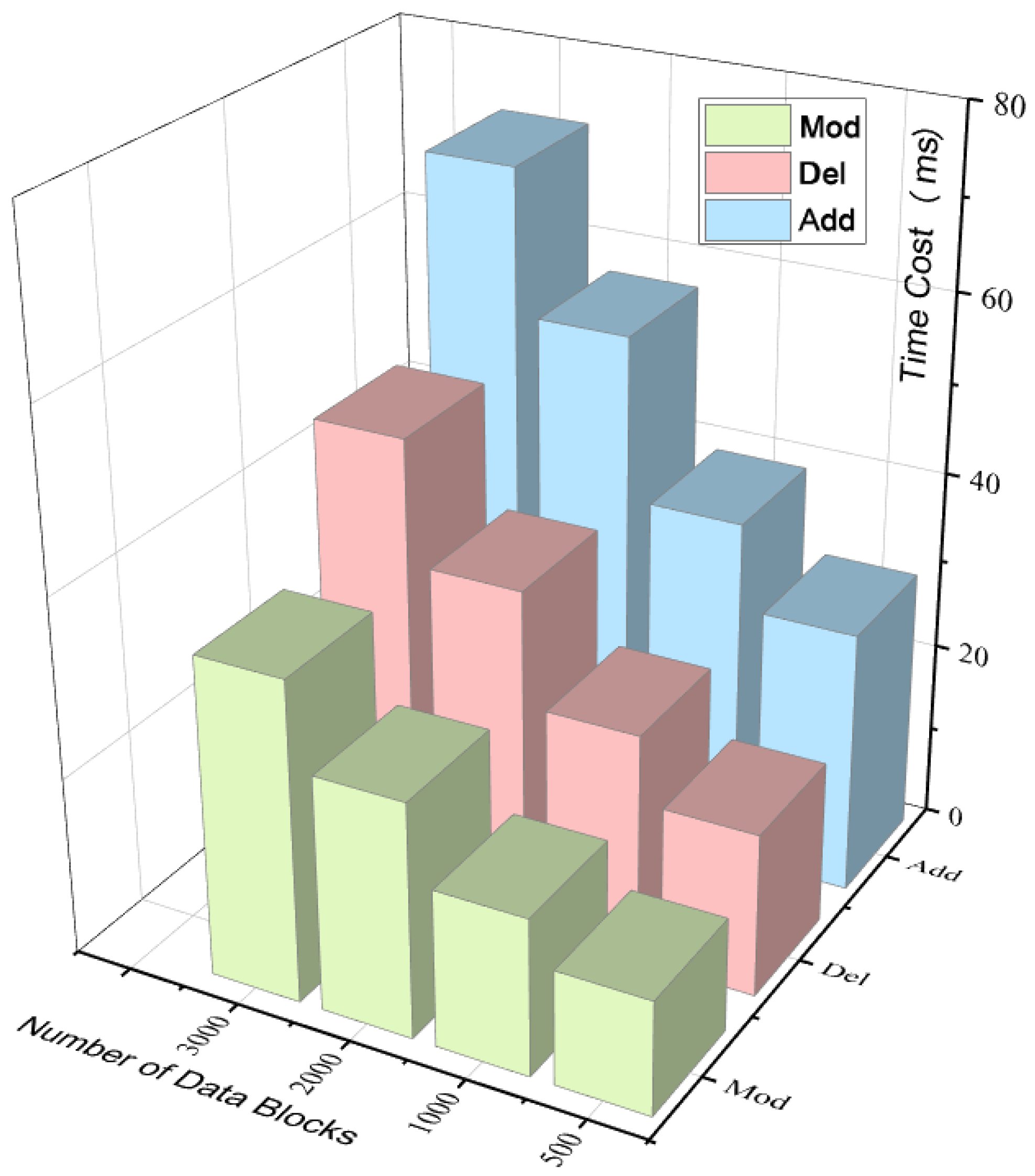

5.5. Overhead of Data Update

5.6. Fault Tolerance Testing

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- EOSC. EOSC Future Results. 2024. Available online: https://eoscfuture.eu/results/ (accessed on 30 June 2024).

- OpenAIRE. Openaire Guidelines. 2024. Available online: https://guidelines.openaire.eu/en/latest (accessed on 31 July 2024).

- Otto, B.; Hompel, M.T.; Wrobel, S. International Data space: Reference architecture for the digitization of industries. In Digital Transformation; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019; pp. 109–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Data Space Business Alliance. Technical Convergence. 2022. Available online: https://data-spaces-business-alliance.eu/wp-content/uploads/dlm_uploads/DSBA-Technical-Convergence.pdf (accessed on 26 September 2022).

- Trustworthy Data Space—Technology Architecture. 2025. Available online: http://jkzgnews.com/d/file/2025-05-12/1747035305429248.pdf (accessed on 30 April 2025).

- Huber, M.; Wessel, S.; Brost, G.; Menz, N. Building Trust in data space. In Designing Data Space; Otto, B., ten Hompel, M., Wrobel, S., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 147–164. [Google Scholar]

- Hackel, S.; Makohl, M.E.; Petrac, S. Trustworthy Data Exchange: Leveraging Linked Data for Enhanced IDS Certification. In Proceedings of the INFORMATIK 2024: 9th IACS Workshop, Wiesbaden, Germany, 24–26 September 2024; Gesellschaft für Informatik e.V.: Bonn, Germany, 2024; pp. 1977–1987. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, Y.; Leng, Y.; Qi, J.; Sharma, P.K.; Wang, J.; Almakhadmeh, Z.; Tolba, A. Multiple Cloud Storage Mechanism Based on Blockchain in Smart Homes. Future Gener. Comput. Syst. 2021, 115, 304–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, J.T.; Bhat, S.A.; Huang, N.F. Blockchain-based privacy-preserving data-sharing framework using proxy re-encryption scheme and interplanetary file system. Peer-to-Peer Netw. Appl. 2023, 16, 2415–2437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gai, K.; Guo, Y.; Yu, J.; Chan, W.; Zhu, L.; Zhang, Y. CAPE: Commitment-Based Privacy-Preserving Payment Channel Scheme in Blockchain. IEEE Trans. Dependable Secur. Comput. 2025, 22, 3977–3992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Chen, J.; Ren, Y.; Sharma, P.; Alfarraj, O.; Tolba, A. Data Security Storage Mechanism Based on Blockchain Industrial Internet of Things. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2022, 164, 107903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Yan, Y.; Guo, S.; Wei, X.; Shao, S. On-Chain and Off-Chain Collaborative Management System Based on Consortium Blockchain. In Advances in Artificial Intelligence and Security; Sun, X., Zhang, X., Xia, Z., Bertino, E., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 197–210. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, Y.; Lv, Z.; Xiong, N.N.; Wang, J. HCNCT: A Cross-Chain Interaction Scheme for the Blockchain-Based Metaverse. ACM Trans. Multimed. Comput. Commun. Appl. 2024, 20, 188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonura, S.; Carbonare, D.D.; Díaz-Morales, R.; Fernández-Díaz, M.; Morabito, L.; Muñoz-González, L.; Napione, C.; Navia-Vázquez, A.; Purcell, M. Privacy-Preserving Technologies for Trusted data space. In Technologies and Applications for Big Data Value; Curry, E., Auer, S., Berre, A.J., Metzger, A., Perez, M.S., Zillner, S., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 111–134. [Google Scholar]

- Deepa, N.; Pham, Q.V.; Nguyen, D.C.; Bhattacharya, S.; Prabadevi, B.; Gadekallu, T.R.; Maddikunta, P.K.R.; Fang, F.; Pathirana, P.N. A Survey on Blockchain for Big Data: Approaches, Opportunities, and Future Directions. Future Gener. Comput. Syst. 2022, 131, 209–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jadhav, S.; Choudhari, G.; Bhavik, M.; Bura, R.; Bhosale, V. A Decentralized Document Storage Platform using IPFS with Enhanced Security. In Proceedings of the 2024 8th International Conference on Computing, Communication, Control and Automation (ICCUBEA), Pune, India, 23–24 August 2024; pp. 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Esposito, C.; De Santis, A.; Tortora, G.; Chang, H.; Choo, K.R. Blockchain: A Panacea for Healthcare Cloud-Based Data Security and Privacy? IEEE Cloud Comput. 2018, 5, 31–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Wang, X.; Zhang, Y. A Secure Cloud Storage Framework with Access Control Based on Blockchain. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 112713–112725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Tan, L.; Shi, N.; Xu, B.; Cao, Y.; Yu, K. AuthPrivacyChain: A Blockchain-Based Access Control Framework with Privacy Protection in Cloud. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 70604–70615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuznetsov, O.; Yezhov, A.; Yusiuk, V.; Kuznetsova, K. Scalable Zero-Knowledge Proofs for Verifying Cryptographic Hashing in Blockchain Applications. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2407.03511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, W.; Fan, Y.; Li, K.C.; Zhang, D.; Gaudiot, J.L. Secure Data Storage and Recovery in Industrial Blockchain Network Environments. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2020, 16, 6543–6552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Han, D.; Li, D.; Weng, T.; Li, K.; Mei, X. MedRSS: A Blockchain-Based Scheme for Secure Storage and Sharing of Medical Records. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2023, 183, 109521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Xiong, L.; Li, F.; Niu, X.; Wu, H. A Blockchain-Based Privacy-Preserving Auditable Authentication Scheme with Hierarchical Access Control for Mobile Cloud Computing. J. Syst. Archit. 2023, 142, 102949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Guo, H.; Xu, M.; Wang, S.; Yu, D.; Yu, J. Extending On-Chain Trust to Off-Chain—Trustworthy Blockchain Data Collection Using Trusted Execution Environment (TEE). IEEE Trans. Comput. 2022, 71, 3268–3280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Hou, C.; Jiang, T.; Ning, J.; Qiao, H.; Wu, Y. FACOS: Enabling Privacy Protection Through Fine-Grained Access Control with On-Chain and Off-Chain System. IEEE Trans. Inf. Forensics Secur. 2024, 19, 7067–7074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Y.; Wu, Z.; Miao, Y.; Xie, L.; Ding, M. Genuine On-Chain and Off-Chain Collaboration: Achieving Secure and Non-Repudiable File Sharing in Blockchain Applications. IEEE Trans. Netw. Serv. Manag. 2024, 21, 1802–1816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Wei, L.; Li, S.; Liu, Y.; Cheung, S.C. ÐArcher: Detecting On-Chain-Off-Chain Synchronization Bugs in Decentralized Applications. In Proceedings of the ACM SIGSOFT International Symposium on Software Testing and Analysis, Virtual, 11–17 July 2021; pp. 553–565. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, Y.; Cao, J.; Bai, D.; Wen, L.; Liu, Y.; Li, R. MAP the Blockchain World: A Trustless and Scalable Blockchain Interoperability Protocol for Cross-Chain Applications. In Proceedings of the ACM Web Conference, Sydney, Australia, 28 April–2 May 2025; pp. 717–726. [Google Scholar]

- Pandey, S.; Rishiwal, V.; Jat, D.S.; Yadav, P.; Yadav, M.; Jain, A. Towards Securing the Digital Document Using Blockchain Technology with Off-Chain Attribute Based Encryption Framework. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Emerging Trends in Networks and Computer Communications, Windhoek, Namibia, 23–25 July 2024; pp. 857–864. [Google Scholar]

- Javed, M.U.; Rehman, M.; Javaid, N.; Aldegheishem, A.; Alrajeh, N.; Tahir, M. Blockchain-Based Secure Data Storage for Distributed Vehicular Networks. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyachi, K.; Mackey, T.K. hOCBS: A privacy-preserving blockchain framework for healthcare data leveraging an on-chain and off-chain system design. Inf. Process. Manag. 2021, 58, 102535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eberhardt, J.; Tai, S. On or Off the Blockchain? Insights on Off-Chaining Computation and Data. In Service-Oriented and Cloud Computing; De Paoli, F., Schulte, S., Broch Johnsen, E., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 3–15. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmadjee, S.; Bahsoon, R. A Taxonomy for Understanding the Security Technical Debts in Blockchain Based Systems. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1903.03323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiayias, A.; Russell, A.; David, B.; Oliynykov, R. Ouroboros: A Provably Secure Proof-of-Stake Blockchain Protocol. In Advances in Cryptology—CRYPTO 2017; Katz, J., Shacham, H., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 357–388. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, X.; Xiong, Z.; Chen, J.; Chen, D. A Secure, Blockchain-Based Data Storage Scheme for Cloud Environments. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Computer, Artificial Intelligence, and Control Engineering (CAICE 2023), Hangzhou, China, 17–19 February 2023; p. 1264524. [Google Scholar]

- Goint, M.; Bertelle, C.; Duvallet, C. Secure Access Control to Data in Off-Chain Storage in Blockchain-Based Consent Systems. Mathematics 2023, 11, 1592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Y.; Huang, D.; Wang, W.; Yu, X. BSMD: A Blockchain-Based Secure Storage Mechanism for Big Spatio-Temporal Data. Future Gener. Comput. Syst. 2023, 138, 328–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, J.; Liu, D.; Chen, X.; Huang, X.; Chen, J.; Zhang, M. Secure Publicly Verifiable Computation with Polynomial Commitment in Cloud Computing. In Information Security and Privacy; Susilo, W., Yang, G., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 417–430. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, R.; Molnar, D.; Song, D.; Wagner, D. Homomorphic Signature Schemes. In Topics in Cryptology—CT-RSA 2002; Preneel, B., Ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2002; pp. 244–262. [Google Scholar]

- Boneh, D.; Drake, J.; Fisch, B.; Gabizon, A. Halo Infinite: Recursive zk-SNARKs from Any Additive Polynomial Commitment Scheme. Cryptol. ePrint Arch. 2020. Available online: https://eprint.iacr.org/2020/1536 (accessed on 3 November 2025).

- Boneh, D.; Freeman, D.M. homomorphic signature for Polynomial Functions. In Advances in Cryptology—EUROCRYPT 2011; Paterson, K.G., Ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2011; pp. 149–168. [Google Scholar]

| Phase | Input Parameters | Output Parameters |

|---|---|---|

| Setup | , t, s, g, p | |

| Commit | , , | |

| Query | i | , , |

| Verify | 1/0 |

| Phase | Input Parameters | Output Parameters |

|---|---|---|

| Setup | , k | , |

| Sign | , , m, i | signature: |

| Verify | , , m, , f | 1/0 |

| Evaluate | , , f, | evaluation: |

| Data Size (n) | On-Chain Storage (KB) | Off-Chain Storage (MB) | Off-Chain Redundancy Rate (%) | Average Signature Size (Bytes) | Commitment Size (Bytes) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 100 | 4.1 | 21.4 | 7.0 | 126 | 32 |

| 500 | 8.3 | 21.6 | 8.0 | 154 | 32 |

| 1000 | 12.5 | 21.8 | 9.0 | 181 | 32 |

| 2000 | 20.8 | 22.1 | 10.5 | 203 | 32 |

| 3000 | 29.1 | 22.4 | 12.0 | 222 | 32 |

| Operation | Sending Rate (TPS) | Max Latency (ms) | Min Latency (ms) | Avg Latency (ms) | Throughput (TPS) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Commitment Verification 1 | 298.36 | 52.17 | 22.35 | 46.89 | 9.82 |

| Commitment Verification 2 | 295.41 | 51.82 | 21.98 | 46.53 | 9.91 |

| Commitment Verification 3 | 297.15 | 51.59 | 22.11 | 46.72 | 9.78 |

| Signature Verification 1 | 362.85 | 28.43 | 12.57 | 14.89 | 15.93 |

| Signature Verification 2 | 365.27 | 28.16 | 12.73 | 14.72 | 15.98 |

| Signature Verification 3 | 368.51 | 28.32 | 12.64 | 14.58 | 15.89 |

| Phase | Query | Update | Consistency |

|---|---|---|---|

| Benchmark | Average response time 65 ms, success rate | Average response time 90 ms, success rate | Matching rate |

| Fault | Success rate | Success rate , response time fluctuation ≤10 ms | No inconsistency |

| After Recovery | - | - | Matching rate |

| Recovery Time | - | - | Full business recovery in 23 s |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yang, X.; Luo, Q.; Xu, J.; Cao, Q. Data Secure Storage Mechanism for Trustworthy Data Space. Electronics 2025, 14, 4348. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14214348

Yang X, Luo Q, Xu J, Cao Q. Data Secure Storage Mechanism for Trustworthy Data Space. Electronics. 2025; 14(21):4348. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14214348

Chicago/Turabian StyleYang, Xinyi, Qicheng Luo, Jiang Xu, and Qinghong Cao. 2025. "Data Secure Storage Mechanism for Trustworthy Data Space" Electronics 14, no. 21: 4348. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14214348

APA StyleYang, X., Luo, Q., Xu, J., & Cao, Q. (2025). Data Secure Storage Mechanism for Trustworthy Data Space. Electronics, 14(21), 4348. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14214348