Abstract

Accurate fault detection for Permanent Magnet Synchronous Motors (PMSMs) prevents costly failures and improves overall reliability. This paper presents a hybrid one-dimensional convolutional neural network (1DCNN)–bidirectional gated recurrent unit (BiGRU) deep learning model for PMSM fault detection. Inverter-driven short-circuit, open-circuit, and thermal faults, as well as stator faults, can cause electrical and thermal disturbances that affect PMSMs. Significant harmonic distortions, current and voltage peaks, and transient fluctuations are introduced by these faults. The proposed architecture utilizes handcrafted features, including statistical analysis, fast Fourier transform (FFT), and Discrete Wavelet Transform (DWT), extracted from the raw PMSM signals to efficiently capture these faults. 1DCNN effectively extracts local and high-frequency fault-related patterns that encode the effects of peaks and harmonic distortions, while the BiGRU of this enriched representation models complex temporal dependencies, including global asymmetries across phase currents and long-term fault evolution trends seen in stator faults and thermal faults. The proposed model reveals the highest metrics for inverter-driven and stator winding fault datasets compared to the other approaches, achieving an accuracy of 99.44% and 99.98%, respectively. As a result, the study with realistic and comprehensive datasets guarantees high accuracy and generalizability not only in the laboratory but also in industry.

1. Introduction

Electric vehicles have been progressively developed into one of the most popular modes of transportation due to the growing worldwide awareness of environmental protection and government support for new energy vehicle policy [1]. Permanent magnet synchronous machines (PMSMs) have been extensively incorporated into electric vehicles due to their superior efficiency, high torque density, low noise, and high power density characteristics. They are also mainly used for industrial applications and modern electric drive systems [2]. However, the rapid spread of PMSMs has resulted in considerable reliability concerns. As in other electrical machines, electrical, magnetic, and mechanical failures may occur in PMSMs due to long-term use under operational stress, particularly when the power source and load characteristics change [3]. Specially, inter-turn short faults [4,5,6,7] in stator winding faults [8,9,10], rotor eccentricity faults [11,12], bearing faults [13], hardware faults, especially sensor and driver failures [14,15,16,17], are the types of failure encountered. Additionally, overheating in PMSMs as a result of overloading, inadequate cooling, or faults in the power electronics leads to excessive thermal stress on windings and magnets, resulting in demagnetization of the permanent magnets, insulation degradation, and ultimately, irreversible motor failure [18].

Accurate and timely detection and diagnosis of faults in PMSMs ensures operational reliability, endurance, and availability. This prevents vital failures, reduces downtime and associated economic losses, and preserves system performance. Considering these challenges and the critical role of fault detection accuracy, academic and industrial studies on advanced fault detection and diagnosis (FDD) techniques for PMSMs have increased [19]. Short circuits, open circuits, overheating conditions, demagnetization, bearing faults, back-electromotor force imbalances, and DC bus voltage disturbances are various faults that can severely compromise the performance and the reliability of the PMSM.

Short-circuit faults, typically occurring in the inverter’s power switches or winding phases, can result in excessive currents, torque ripples, and ultimately damage to the drive system. Open-circuit faults, often caused by broken connections or malfunctioning switches, result in unbalanced phase currents and reduced torque output, which adversely affect motor stability. Overheating faults, usually caused by prolonged overloading, insufficient cooling, or internal insulation degradation, can accelerate aging of the permanent magnets and stator windings, leading to irreversible motor damage. Early and accurate detection of these fault types is therefore critical to prevent costly downtimes and ensure operational safety. To address these challenges, hybrid diagnostic methods that combine data-driven approaches with signal processing techniques have emerged as effective solutions for capturing subtle variations in electrical and thermal signatures associated with each fault condition.

The approaches for fault detection of PMSMs can be categorized into signal-based, model-based, data-driven [20,21], and hybrid methods. Signal decompositions (wavelet transform and Fast Fourier Transform), Motor Current Signature Analyses (MCSA) [22], and vibration analysis [13] are signal-based methods. Observer-based detection and parameter estimation are examples of model-based algorithms [7]. These traditional FDD methods are successful but often struggle with complex and nonlinear fault patterns in PMSMs because of their sensitivity to model uncertainties [23,24]. In this regard, Fang et al. [25] improved a zero-sequence voltage component (ZSVC)-based inter-turn fault detection technique. The noise and harmonics were filtered by the Discrete Wavelet Transform (DWT), and the extracted fault characteristic components were analyzed with the fast Fourier transform (FFT). Although the proposed method yields successful results, it requires the neutral point to be accessible, which limits its applicability and makes it feasible only for fault-tolerant PMSM drives. For the inter-turn short-circuit fault (ITSCF) detection problem, a model-based FDD approach combining an Extended Kalman Filter (EKF) with a Fuzzy Logic Estimator (FLE) was proposed by Romdhane et al. [26]. They evaluated their algorithm on Field-Oriented Controlled (FOCed) faulty PMSM using MATLAB/Simulink. As an example of model-based FDD, Xu et al. [27] developed a high-frequency (HF) mathematical model and analyzed the negative-sequence component of the model. They determined the fault severity based on the amplitude of the HF negative-sequence component and used the initial phase to locate the position of the faulty phase. Another signal- and model-based FDD method was proposed by Hang et al. [28]. The ITSCF diagnosis method for model-predictive control (MPC) and wavelet transform to extract the fault feature from the cost function were realized. There are also studies in the literature that focus on diagnosing multiple fault types simultaneously with a single method. Xu et al. [29] successfully distinguished both open-switch and current-sensor faults in IM drives using a reduced-order range observer, thereby eliminating the need for complex classification algorithms. They demonstrated the availability of the developed diagnosis algorithm through comparative analysis.

Analyzing the aforementioned studies reveals that the signal-based method relies on detecting signal anomalies (such as harmonics and spectral components) associated with specific faults, while the model-based method focuses on mathematical equations and physical principles to model a particular fault condition. These conventional methods have significant limitations, despite being successful in some situations. Beyond their high sensitivity to model uncertainties, they often lack the inherent capability to perform a broad and robust classification across diverse fault types.

Another category of PMSM fault detection approaches is the data-driven method, which comprises Independent Component Analysis (ICA), Principal Component Analysis (PCA), Canonical Correlation Analysis (CCA), neural networks (NNs), deep learning (DL), and machine learning (ML). The superiority of the data-driven method lies in its ability to avoid the need for predefined equations, expert knowledge, or a mathematical model [19]. It automatically learns discriminative features directly from raw input signals. By integrating the data-driven model with signal processing techniques such as the wavelet transform and FFT, a hybrid model is constructed to enhance time–frequency domain features, thereby improving classification performance and system robustness against noise and varying operating conditions. In addition to increasing resilience to noise and difficulties in feature selection, the hybrid model reduces the reliance on precise system modeling. El-Dalahmeh et al. [30] proposed an effective fault classification method that combines variational mode decomposition (VMD), the Hilbert–Huang transform (HHT), and a convolutional neural network (CNN). Instead of handcrafted frequency-domain features, instantaneous frequency features extracted through a combination of VMD and HHT were fed into the CNN. Another noteworthy example of a hybrid approach was presented by Mohammad-Alikhani et al. [31]. They presented a differential short-time Fourier transform (STFT) combined with a channel-wise regulated CNN for different datasets, including ITSCFs under noisy environments. Their proposed model showed superior performance under normal and noisy conditions. Another hybrid study, a CNN–BiLSTM-based method, combined with VMD, was proposed by Yu et al. [32] to effectively extract fault features from stator currents and classify turn-to-turn short-circuit and demagnetization faults. Their simulation results demonstrated the method’s robustness and practical applicability. Integrating a signal-based approach, bispectrum analysis (BA), with a CNN for the classification of winding faults was introduced by Pietrzak et al. [8]. Bispectrum features were extracted and fed into a CNN, achieving a classification accuracy of 99.4%. As a noteworthy example, Mahmoud et al. [33] proposed a scheme that combines a transfer-learned, pre-trained residual neural network (ResNet) with supervised machine learning (S-ML) methods for a noisy environment, utilizing the Continuous Wavelet Transform (CWT) for feature extraction. As a result, they decreased computational cost and achieved 96.84% accuracy in noisy industrial environments. Another hybrid approach, multi-level feature extraction and DWT for five different fault classes, was proposed by Boztas and Tuncer [34] using a dynamic centered one-dimensional local angular binary pattern. They evaluated their model on the dataset that they acquired and achieved high accuracy in the classification.

In recent years, Transformer-based architectures have become increasingly prevalent in motor fault diagnosis. In Zsuga and Dineva’s study [35], ITSCFs were detected using a Transformer architecture based on temporal-frequency components derived from stator current signals, yielding an accuracy of approximately 97%. Specifically, the recent work addressing ITSC faults in oil-drilling applications utilized a time-sequence efficient moving window self-attention network, achieving 96.72% accuracy while notably reducing computational complexity via half-sandwich and cascaded attention operations [36]. Yu et al. [37] proposed a dual-arm Transformer architecture that simultaneously evaluates features in both the time and frequency domains, reporting 99.79% accuracy and 99.79% F1-score with a very low number of parameters. These models incorporate strategies to reduce computational load by utilizing regional or window-based attention mechanisms, rather than traditional self-attention. Even if Transformer-based architecture enables fast inference and learning by processing temporal dependencies in parallel, rather than sequentially, Transformers naturally lack the inherent capability of CNNs to hierarchically extract local patterns; thus, they typically necessitate the use of patching or tokenization methods to encode local spatial information.

It is crucial to assess the proposed method in relation to approaches that rely solely on recurrent neural networks (RNNs). Lale et al. [38] demonstrated the inherent capability of using pure long short-term memory (LSTM) and gated recurrent unit (GRU) models directly on three-phase current signals, achieving high accuracy (98.23% and 98.72%). Furthermore, the stacked de-noising autoencoder–generative adversarial network–LSTM model proposed by Feng et al. [39] highlights the significant challenge of unbalanced fault data samples in real-world PMSM systems, utilizing a stacked denoising autoencoder–generative adversarial network–long short-term memory (SDAE-GAN-LSTM) approach to boost the average accuracy to 98.63%. On the other hand, CNN–LSTM hybrid architectures have the capacity to handle sequential time dependencies with LSTM while performing local feature extraction with convolutional layers. Cheng et al. [40] proposed a one-dimensional CNN (1DCNN)–bidirectional LSTM (BiLSTM) hybrid, specifically designed for highly accurate stator temperature prediction using raw data and clustering of operating conditions. Furthermore, where many CNN–LSTM hybrids utilize the LSTM unit, the choice of the bidirectional GRU (BiGRU) offers a simpler, two-gate recurrent unit that provides a performance comparable to BiLSTM while significantly reducing the number of parameters.

Along with the development of state-of-the-art methods, the variety of hardware faults in motors has also increased in recent times. In addition to ITSCF, one of the most significant stator winding faults, the literature also discusses inverter-driven faults that impact the motor’s overall performance. In this context, Chu et al. [17] proposed a neural network-based system for open-circuit fault in an inverter using phase-to-phase voltage data, where separate CNN and CNN–LSTM architectures were trained for each motor phase. For another open-circuit fault in PMSM drivers, Cai et al. [41] proposed a Bayesian network with PCA and FFT. They validated their study with simulations and experiments.

In this study, a new hybrid 1DCNN–BiGRU architecture was designed for FDD of PMSM. Two different area datasets were utilized, one of inverter-based and the other motor-based (stator winding) faults, providing a greater diversity of application and improved generalizability compared to conventional approaches. While the proposed model was evaluated on all of the fault cases in the inverter-drive dataset, it was applied to 10 faulty and 1 healthy case (a total of 11 classes) in the stator winding fault dataset. An advanced regularization strategy was employed. Additionally, an adaptive learning framework was employed to ensure robust model convergence and achieve superior classification performance. A sliding window technique was used to divide the raw time-series signals into smaller segments in two very distinct datasets. To capture fine-grained temporal dynamics in the inverter-driven dataset, an overlapping windowing technique with a 75% overlap ratio was employed. To preserve computational efficiency while capturing a wider range of signal characteristics, a non-overlapping sliding windowing strategy with a larger window size was used for the stator winding fault dataset. These segments were first rigorously preprocessed into a comprehensive feature set in order to fully utilize the potential of this hybrid architecture. The handcrafted time-domain, frequency-domain, and time–frequency features were extracted using statistical analysis, FFT, and DWT with the Daubechies 4 (db4) wavelet, for each segment obtained via a sliding window. Subsequently, these multi-domain features were merged into a single, robust feature vector, creating a more comprehensive representation of the fault condition.

The inverter-driven method, utilizing a Transformer-based physics-informed neural network (PINN) framework, was proposed by Bacha et al. [42], who employed the same dataset [43] as the current study. They achieved a relatively lower classification performance with 98.57% accuracy. Another study on the same dataset as the current study, with lightweight-framework machine learning methods, was presented by Hague et al. [44]. They developed eight ML models and achieved a maximum accuracy of 98.71% on the test data using XGBoost. While both studies effectively combine data-driven modeling with PINN and various ML algorithms, respectively, the current study attains even greater accuracy (99.44%) on the same dataset by utilizing a 1DCNN–BiGRU architecture with handcrafted features. Additionally, the other performance metrics were achieved at a higher level than those reported in these studies.

A recent and closely related study by Mesai-Belgacem et al. [45] proposed a data fusion approach using the RegNet model for ITSCF, based on the dataset from the same source [46] as the stator winding fault dataset employed in this study. Their investigation was limited to four different ITSCFs plus a healthy class in a single dataset using down-sampled data (20 s from 120 s). In contrast, this present study adopts a more comprehensive approach, covering 11 different classes with various properties (inter-turn, inter-coil, and different power levels, among others). Employing sliding windows directly on the raw signal dataset and engaging feature fusion with handcrafted features yields stronger representation capabilities compared to [45]. Another study using the same dataset [46], by Tang et al. [47], developed a CNN–BiLSTM hybrid model with DWT for PMSM anomaly detection, achieving a maximum accuracy of 99.96%. In the present study, in addition to the DWT features, a more comprehensive feature set was created by using FFT and various statistical parameters. The other study on the same dataset was proposed by Chen et al. [48]. They employed the Gramian Angular Field (GAF) technique to convert one-dimensional signals into image data containing feature information, as well as a 2D convolutional neural network (2D CNN) with BiGRU for analyzing the faults. They evaluated their study on 20 s of limited data for a single power level (3 kW) and worked with four failure classes and a normal class. Despite the more complex and computationally costly approaches based on this architecture, the methodology of the present study has shown better generalizability and classification performance in an extensive problem space (different fault types and datasets).

In summary, the comparison with recent, state-of-the-art studies clearly demonstrates the superiority and necessity of the proposed hybrid 1DCNN–BiGRU architecture combined with handcrafted multi-domain feature fusion. Specifically, the methodology of the present study, with its comprehensive feature set and its successful application across two highly distinct fault datasets, has shown a better generalizability and classification performance in an extensive problem space.

Based on this information, the main motivation of the proposed study is as follows: PMSMs are widely used in industry due to their efficiency, high power density, and precise control capabilities. Additionally, they offer dynamic performance and low power losses because they do not require external excitation in the rotor structure. Accurate and timely fault detection of these motors is crucial to enhancing the reliability of rotating machines and preventing costly failures. This requirement has led to the need to develop a robust fault detection system utilizing both time- and frequency-domain characteristics.

The main contributions of this study are outlined as follows.

- To comprehensively evaluate the effectiveness of the proposed model, it is initially applied to two distinct datasets that represent different failure types and the data collection process: (i) real-world operating measurements collected from an inverter-driven PMSM system combining current, voltage, and temperature values [43]; (ii) PMSM stator fault data containing inter-coil and inter-turn short-circuit faults (ITSCFs) acquired under varying power levels [46].

- An inclusive preprocessing pipeline is developed to become highly representative. Multi-channel signals are processed separately to capture phase-specific characteristics, enhancing feature diversity and allowing models to learn phase-dependent fault patterns.

- The proposed model works reliably under various data conditions and can identify a variety of fault types. This work considers both stator current faults and inverter-driven faults within a combined framework, in contrast to some earlier studies that focus on a single fault type.

- The proposed novel hybrid 1DCNN–BiGRU architecture collaboratively combines the temporal dependency modeling strengths of BiGRU and the spatial feature extraction capabilities of CNN. This architecture comprises three sequential 1DCNN layers and two BiGRU layers. The Synthetic Minority Oversampling Technique (SMOTE) algorithm is used to create new samples for minority classes, addressing the inherent class imbalance frequently present in fault datasets. Furthermore, a comprehensive regularization framework that incorporates L1–L2 dual regularization, adaptive dropout rates (0.1–0.3), and batch normalization across all layers is introduced. When combined with an early stopping mechanism, this approach effectively reduces overfitting and enhances the model’s ability to generalize in fault classification tasks. To the best of the author’s knowledge, this technique is employed for the first time to diagnose PMSM ITSCFs and inverter-driven failures for several classes.

- To increase the transparency and interpretability of the hybrid model, the SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) technique, the most popular Explainable Artificial Intelligence (XAI) method, is employed to analyze the feature contributions to the model’s fault classification decisions. In this way, it is made clear which frequency or statistical information the model considers critical.

- Using a 5-fold cross-validation scheme on the whole evaluation process, the robustness of the model and its ability to be generalized to different subsets of data are verified. This method proved that the model achieves consistent high accuracy not only on a specific test set but also on the overall data distribution.

- This study presents a novel approach that advances the state-of-the-art in the field of industrial fault classification by demonstrating that a hybrid 1DCNN–BiGRU architecture can surpass both singular architecture deep learning methods (1DCNN, BiGRU, and Multilayer Perceptron (MLP)) and a conventional machine learning technique (Random Forest, RF).

To the best of the author’s knowledge, based on the existing literature, this study presents the first hybrid 1DCNN–BiGRU method with XAI and K-fold cross-validation for PMSM stator winding fault classification across a wide range of fault types. It accurately detects 11 classes of incipient faults with near-perfect performance, thereby extending previous studies that were limited to fewer classes.

The organization of the paper is as follows: The preprocessing pipeline and utilized deep learning models are summarized in Section 2. Data preprocessing and handcrafted feature extraction processes, along with a brief table, are presented in this section. Section 3 provides a detailed description of the proposed method. The overall scheme, including all functions, is presented in this section. The datasets tried with the proposed model and the acquisition processes are placed in Section 4. The comprehensive experimental verification results are presented in Section 5. The environment and model configuration, as well as the performance metrics for model evaluation and the experimental results for each dataset, are presented in this section.

2. Multi-Domain Feature Extraction and Deep Models

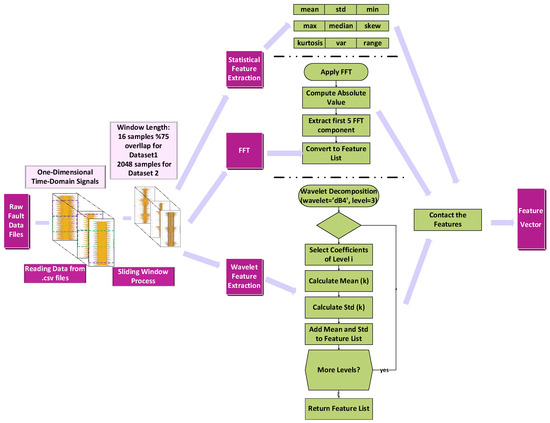

The present raw data is redesigned using sliding windows by converting a time-series signal into a dataset consisting of fixed-size and overlapping segments. The segmental transformation enables the model to capture local and transient anomalies in the data more effectively. The comprehensive data processing methodology used to train the model is presented in a detailed block diagram in Figure 1. The hybrid approach provides enriched data to 1DCNN–BiGRU, enabling comprehensive and versatile feature extraction from multidimensional sensor data. Multi-domain features are extracted from real, industry-standard PMSM sensor data. This observation aligns with the notion that combining different data representations enhances model performance [49]. These encompass time-domain, frequency-domain, and time–frequency domain features, followed by deep feature learning using 1DCNN and BiGRU layers. Each stage contributes to different aspects of the data representation, as summarized in Table 1.

Figure 1.

Data preprocessing and handcrafted feature extraction.

Table 1.

Summary of multi-domain feature extraction and deep models.

3. Proposed Method

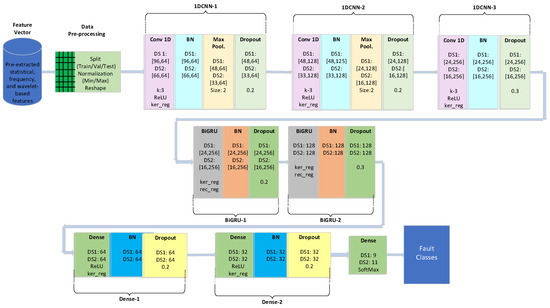

As previously emphasized, this study proposes a fault detection system that utilizes a hybrid deep learning framework, combining the spatial feature learning capability of CNNs with the temporal pattern learning capability of BiGRUs. This synergistic method addresses the inherent challenges in motor fault detection, where both local feature patterns and long-term temporal patterns are important for accurate fault diagnosis. The comprehensive approach is illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

The overall scheme of the proposed hybrid approach (BN: batch normalization; DS: dataset; k: kernel size; ker_reg: kernel regularizer; rec_reg: recurrent_regularizer).

The input of the hybrid deep model consisted of handcrafted features from three complementary domains: statistical measures, frequency-domain features via FFT, and time–frequency description through wavelet decomposition. When , expressing the concatenated feature matrix—where represents the number of time windows and is the total feature dimensionality—Equation (1) states the single feature matrix combining all three feature types:

where comprises statistical features, contains the first five FFT components, and encompasses wavelet coefficients by db4 wavelets at level 3.

The designed feature dataset passed critical preprocessing stages to guarantee optimal performance and dependable evaluation prior to model training. After the feature matrix and label vector were combined, a stratified split was performed to split the dataset into training (60%), validation (20%), and test (20%) sets, saving the class distribution in each set. Subsequently, the Min–Max normalization technique, as given by Equation (2), was employed to scale feature values to the [0, 1] range, which is necessary for the stable training of deep learning models. After that, the feature vectors are converted into a tensor format suitable for the network architecture.

The CNN component consisted of three sequential 1D convolutional blocks, designed for hierarchical feature extraction. Each convolutional block followed the pattern below:

where represents the output of the previous layer; and denote convolution filters and bias; ReLU is the activation function; BN stands for batch normalization, MaxPool is maximum pooling; and Dropout is to prevent overfitting. The maximum pooling procedure was excluded in the final convolutional block to retain additional temporal information for the BiGRU layers.

The output from the CNN layers is input into two stacked BiGRU layers to capture sequential dependencies and temporal correlations among features. The first BiGRU layer consisted of 128 units, and the second layer had 64 units, with dropouts of 0.2 and 0.3, respectively. Both layers were followed by return sequences and batch normalization. The BiGRU process is

where is the hidden state at timestep . The BiGRU combines forward and backward passes to encapsulate bidirectional dependency.

The final dense layers converted the learned temporal–spatial representations into a concise feature space appropriate for fault classification. The processed features were transmitted through two fully linked layers of sizes 64 and 32, each followed by batch normalization and dropout for regularization. This process is given as

Finally, the SoftMax activation function outputted the predicted probabilities for each of the 9 classes in the first dataset and the 11 classes in the second dataset. This process is given as

where is the feature learned by the BiGRU layer, and are the weight matrix and bias term of the dense layer, and denotes the predicted probability distribution over the classes. The SoftMax function is calculated by

The model was optimized using the Adaptive Moment Estimation (Adam) optimizer (initial learning rate = 1 × 10−4), combining the advantages of both AdaGrad and RMSprop optimizers. The sparse categorical cross-entropy (SCCE) loss was employed to train the model as

where N represents the total sample number; and denotes the true class label of the ith sample; is the estimated probability of for the ith sample; and is the number of classes.

To prevent the developed hybrid 1DCNN and BiGRU model from overfitting to the training data and performing poorly on the test data, a variety of regularization techniques were employed throughout the training process. These techniques enhanced the model’s capacity for generalization, yielding more robust and reliable results.

3.1. Batch Normalization After Each Major Layer

Batch normalization layers, which standardize the data distribution among their layers, speed up the training process and allow the network to learn more consistently. Normalizing the input of each layer reduces sensitivity to the learning rate and provides additional resistance to overfitting by mitigating the internal covariate shift that occurs in the deeper layers of the model.

3.2. Dropout with Varying Probabilities (0.2–0.3)

Dropout is a potent regularization strategy that stops the model from overfitting by randomly disabling neurons in the neural network layers with a predetermined probability. This technique trains a distinct network architecture at each training phase, preventing co-adaptation between neurons. Dropout was chosen at various rates for the layers. The model’s complexity and the requirements for generalization of each layer were taken into consideration when adjusting these ratios.

3.3. L1–L2 Regularization with a Coefficient

This technique is a widely used method to prevent overfitting, especially in complex deep learning models. The occurrence of excessively large weight values is prevented by adding a penalty term to the weight matrices of the model. Both L1 (Lasso) and L2 (Ridge) penalties reduce the model’s complexity, helping to create a simpler and more generalizable structure.

3.4. Early Stopping

The training procedure is automatically halted when the validation set loss value does not improve over a specified number of consecutive epochs. In the proposed model, the patience value was chosen as 15. This strategy prevents the model from continuing training unnecessarily and overfitting.

3.5. Data Balance with SMOTE

DL model success generally depends on a balanced training dataset. Notably, the first dataset, formed with inverter-driven faults, consists of imbalances in the number of samples for different fault types, as shown in Table 2. As a result, the model may be more likely to learn classes with a larger number of samples (the majority), which would make it harder for it to predict classes with fewer samples (the minority). This problem can significantly decrease the model’s generalization performance and, consequently, its fault detection accuracy. To address this class imbalance issue and ensure that the model learns all failure classes equally, SMOTE was applied exclusively to the training dataset. The dataset was balanced by generating new synthetic samples for the minority classes. This method identifies the nearest neighbors among existing minority class samples and utilizes their properties to generate new, artificial data points.

Table 2.

The fault scenarios for the inverter-driven dataset [43].

4. Description of Experimental Dataset

The proposed hybrid deep model was verified separately using two distinct types of PMSM fault datasets. The first dataset is the comprehensive up-to-date dataset for FDD in an inverter-drive PMSM [43]. The second one is stator winding faults, comprised of an inter-turn and inter-coil short-circuit fault datasets, which is frequently preferred in the literature [46]. The wide application area and the robustness of the model were verified with this approach.

4.1. Inverter-Driven Dataset

In industrial applications, the reliable operation of PMSM highly depends on the state of power inverters. Inverter faults are one of the critical failure types that have a direct impact on motor performance and typically occur before stator or rotor failures. Short-circuit faults, open-circuit faults, and overheating are inverter-related complications that cause abrupt performance drops, uncontrollable vibrations, and even total system failure in the motor drive system. Inverter faults must be identified promptly to protect the motor and the drive system as a whole. Failing to do so may result in irreversible damage to the motor windings and a substantial increase in repair expenses.

Therefore, in this study, model performance was evaluated using the comprehensive fault detection and diagnosis dataset for inverter-driven PMSM systems published by Bacha et al. in 2025 [43] as the first case for evaluation. This is a multi-sensor dataset derived from real-world conditions. This dataset is the first to apply a hybrid method. The dataset has the following basic characteristics:

- Total sample number: 10,892 samples;

- Operational state numbers: 9 states (1 normal, 8 fault types);

- Sensor measurements: 8 raw sensor measurements (phase currents, DC bus voltage/current, temperature);

- Sampling frequency: 10 Hz;

- Fault types: Open-circuit faults, short-circuit faults, and half-bridge overheating conditions.

The dataset was obtained using ACS712 20 A hall-effect sensors for phase currents and DC bus current, with series resistors added to these sensors for voltage measurements (DC bus voltage and driver voltage). Additionally, 10 kΩ NTC thermistors were used for temperature sensing, and the data acquisition system was based on an Arduino. The data were collected under controlled experimental conditions (ambient temperature of 25 °C, 15 V DC power supply, and a motor speed of 10 rad/s). The fault types, along with their corresponding fault labels, are listed in Table 2.

The dataset used for the model consisted of 2692 samples, each with 96 features, and was split into training (1614 samples), validation (539 samples), and test (539 samples) sets. The class distribution was inherently imbalanced; therefore, SMOTE was applied to create a balanced dataset for all fault types, thereby preventing the model from becoming biased toward the majority classes. SMOTE was used during training to create synthetic instances for the minority classes. To improve generalization and overall classification performance, this method is crucial for ensuring the model learns to recognize all fault conditions, regardless of their frequency of occurrence. To avoid overfitting, the model was trained for a maximum of 200 epochs using learning rate reduction techniques and early stopping.

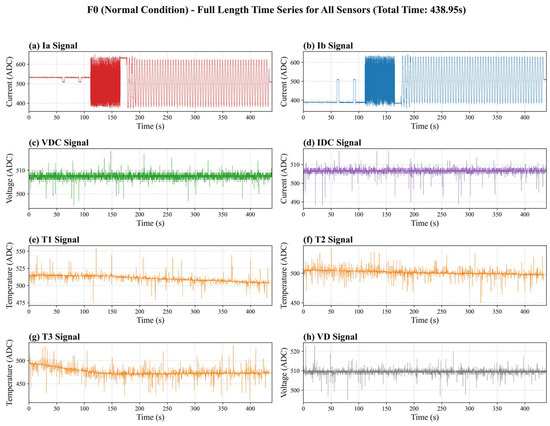

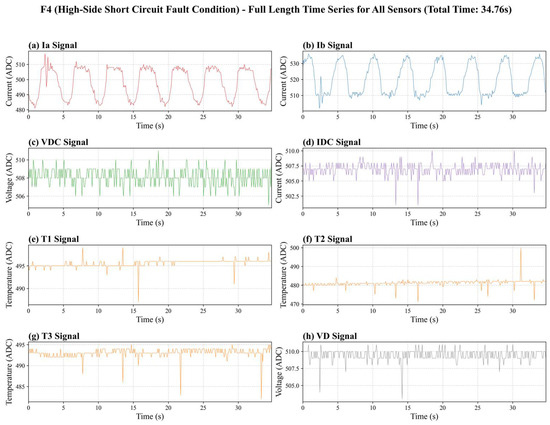

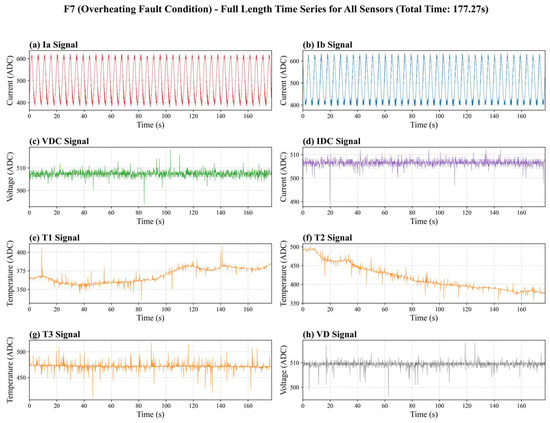

Figure 3, Figure 4 and Figure 5 show the full-length raw time-series signals obtained from all sensors under three representative PMSM operating conditions: F0 (normal), F4 (high-side short-circuit fault), and F7 (overheating fault) (the other signals for the remaining cases are presented in Appendix A). The phase currents (Ia and Ib), DC bus voltage (VDC), DC bus current (IDC), half-bridge sub-circuits temperatures (T1, T2, and T3), and driver voltage (VD) measurements are shown in each subfigure. The phase currents show a clear sinusoidal waveform under normal conditions (F0), suggesting steady and balanced operation. On the other hand, asymmetric conduction in the high-side short-circuit fault (F4) results in significant waveform distortion in the phase currents, and the DC link quantities exhibit greater fluctuations, as shown in Figure 4. While the current waveforms for the overheating fault (F7) remain sinusoidal, the temperature sensors (T1–T3) exhibit a distinct upward trend over time, indicating an increase in the system’s thermal stress, as shown in Figure 5. These visual patterns serve as the basis for subsequent feature extraction and data-driven fault diagnosis, confirming that the obtained raw data contain unique temporal characteristics for each fault type.

Figure 3.

Multi-sensor time-series data (currents, voltages, and temperature) from PMSM under the normal operation (N0) case.

Figure 4.

Multi-sensor time-series data (currents, voltages, and temperature) from PMSM under the high-side short-circuit fault case.

Figure 5.

Multi-sensor time-series data (currents, voltages, and temperature) from PMSM under the overheating fault case on the half-bridge sub-circuits.

The raw PMSM sensor signals, from which the feature sets were derived, exhibit diverse temporal and morphological characteristics under different fault types. Instead of processing raw time-domain waveforms directly, the proposed model utilizes statistical, wavelet, and FFT-based features extracted from these signals. In this configuration, the convolutional layers effectively learn spatial correlations and hierarchical feature interactions across the extracted domains, enabling the network to capture complex fault-related patterns that correspond to variations in amplitude, frequency components, or transient energy distributions. The bidirectional nature of the BiGRU layer is essential for the model’s performance, as it allows for the effective capture of time-series information and long-range correlations associated with slowly developing thermal faults. This provides a substantial advantage to the hybrid architecture by enabling the model to learn sequential dependencies and temporal continuity among the extracted feature segments. Consequently, the CNN module acts as a local pattern recognizer, emphasizing instantaneous distortions or sudden transients, whereas the BiGRU module models the evolving fault dynamics and dependencies between sensors.

4.2. Stator Winding Fault Dataset

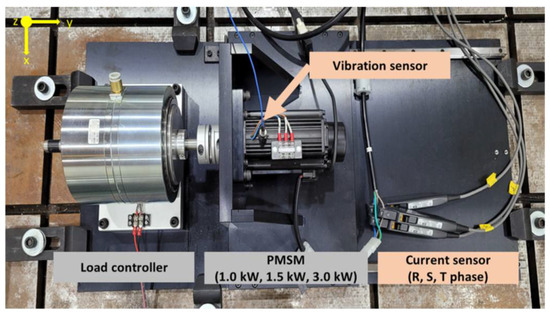

Stator winding failures are the most damaging of all PMSM issues. They generally start out as an undetectable single-turn short circuit, which spreads swiftly over the entire winding to cause a phase-to-phase or phase-to-ground short circuit. Emergency stops and even safety incidents may result from these flaws if they are not identified and diagnosed in a timely manner. High expenses could be linked to this risky circumstance. Furthermore, rotor permanent magnets may become irreversibly demagnetized as a result of ITSCF [8]. For these reasons, the datasets of the PMSM with different power values for stator faults [46], which comprise various stator short-circuit faults, were used in this study. This was chosen because of its extensive usage in the current literature. The test rig for the data acquisition from the PMSMs is shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

The stator winding fault dataset test rig [46].

The dataset was obtained from 3-phase, 4-pole PMSMs with power ratings of 1.0 kW, 1.5 kW, and 3.0 kW, all from the same manufacturer and at the same speed (3000 RPM). It includes two main fault types—inter-turn and inter-coil short circuits, which bypassing resistances were used to artificially seed. A total of 8 inter-coil circuit faults and 8 inter-turn circuit faults are the seeds of a total of 16 stator faults in each motor. There are 48 inter-turn and inter-coil short-circuit fault vibration data files, obtained using a PCB352C34 accelerometer with a sampling frequency of 25.6 kHz. Additionally, 48 sets of inter-turn and inter-coil short-circuit fault current data were acquired using Hioki CT6700 current sensors at a sampling frequency of 100 kHz for 120 s. These datasets contain various severities caused by bypass resistors. This dataset comprises diverse and large data files due to the severe failure ranges, high sample frequencies, and long sampling duration. To address this, one healthy and ten faulty three-phase current fault files were selected for this study, consisting of three motors with different fault types. The selected files are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Fault scenarios for inter-turn and inter-coil short-circuit current dataset [46].

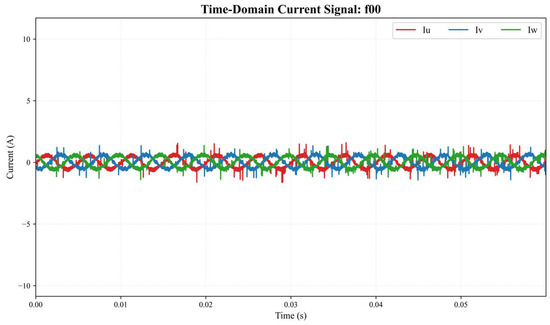

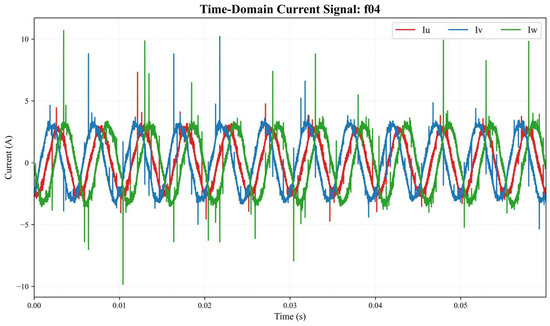

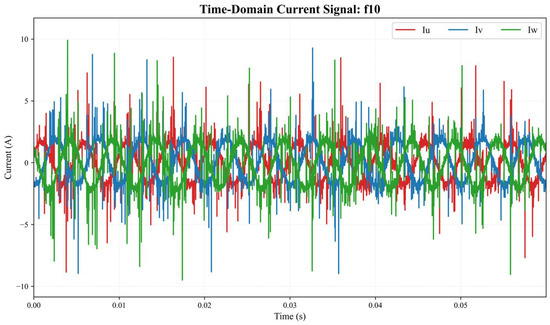

To increase the reliability and transparency of the data on which the proposed hybrid model is based, time-domain plots of three-phase current signals representing the healthy state of the motor and stator fault states with diverse severity ratios (16.08 inter-turn and 23.48 inter-coil) are presented in Figure 7, Figure 8 and Figure 9. Visual analysis confirms a marked distortion in the current signals, accompanied by a gradual increase in the severity of the motor fault. While the healthy state (f00) signal maintains a balanced and low-amplitude sinusoidal structure, as the fault severity increases (f04 and f10 cases), significant increases in current amplitudes, disruption of interphase symmetry, and high-frequency harmonic components become dominant.

Figure 7.

Time-domain three-phase current signals of the PMSM under the healthy condition.

Figure 8.

Time-domain three-phase current signals of the PMSM under the inter-turn short-circuit fault with 16.08% severity.

Figure 9.

Time-domain three-phase current signals of the PMSM under the inter-coil short-circuit fault with 23.48% severity.

These observations demonstrate that stator faults result in significant frequency-domain variations in the structure of the current signals. Therefore, instead of using the raw signal data directly, the Fourier and db4 wavelet transforms were applied to the signals to best capture these subtle differences between motor states. The handcrafted frequency-domain features obtained by these transforms encoded the spectral distribution and time-dependent variation in the signal energy, forming the basis for the highly accurate classification of the hybrid 1DCNN–BiGRU model. Thus, the evidence provided by the raw signal analysis scientifically supports the necessity and effectiveness of the feature engineering approach, as well as the local spatial dependencies and morphological features, temporal dependencies, and long-term dynamics capturing capabilities of the 1DCNN and BiGRU.

5. Experimental Verification

The proposed FDD methodology was confirmed through a rigorous and multi-phase experimental evaluation to validate its performance, robustness, and architectural efficiency. This section presents a two-part ablation study, where the first part examines the contribution of the handcrafted features (statistical, FFT, and wavelet) and the second part systematically analyzes the performance gains contributed by the hybrid architecture components (1DCNN-only, BiGRU-only, and hybrid). Subsequently, a comparative study was conducted against baseline models (MLP and RF) to benchmark the overall performance. Furthermore, the model’s transparency is ensured by utilizing the SHAP technique to identify the critical features that drive the fault classification decisions. The robustness and generalization capability of the final model are confirmed through 5-fold cross-validation.

5.1. Experimental Environment and Model Configuration

All experiments were implemented in Python 3.10.using the PyCharm 2021.3.3 IDE with the TensorFlow framework (TensorFlow-gpu 2.10.0) on a computing platform equipped with an Intel Core i7-14700HX CPU, 32 GB RAM, and an NVIDIA GeForce RTX 4060 GPU. To build the deep learning models, the Keras API within TensorFlow was employed.

NumPy and Pandas were employed for efficient data preprocessing and handling for the overall implementation. Scikit-learn was extensively used for essential deep learning utilities, including data normalization, label encoding, dataset splitting, evaluation metrics calculation, 5-fold cross-validation scheme setup, and dimensionality reduction with t-SNE. Furthermore, the SMOTE algorithm from the imbalanced-learn library was exclusively utilized on the training data to mitigate class imbalance. Finally, to ensure the model’s transparency and interpretability, the SHAP library was employed for feature contribution analysis. The deep learning models, including 1DCNN and BiGRU, were designed using convolutional, pooling, recurrent, and dense layers. The initial learning rate was set at 0.0001, and the Adam optimizer was chosen for the training configuration. Data were fed into the model with mini-batch sizes of 32 for the inverter-driven dataset and 256 for the stator winding fault dataset. EarlyStopping and ReduceLROnPlateau callbacks were employed to avoid overfitting and improve convergence. Furthermore, several regularization strategies and callback mechanisms, such as L1–L2 weight regularization, batch normalization, and dropout layers, are used to further enhance generalization. If there was no improvement in validation loss, the learning rate was dynamically adjusted, enabling the model to converge toward an optimal solution. Matplotlib 3.7.0 and Seaborn 0.12.2 were used for graphical analysis and performance visualization.

5.2. Evaluation Metrics

To demonstrate the model’s superiority, several performance metrics were employed, providing a comprehensive evaluation. The main metric, accuracy, which represents the total percentage of correctly classified samples, was employed and is shown as

The terms in the formula are obtained from the confusion matrix, where the model’s predictions are classified according to the actual conditions [50]. While TP represents the number of cases that the model predicts as positive and are actually positive, TN is the number of cases that the model predicts as negative and are actually negative. FP and FN are the numbers of incorrect predictions of the cases that are predicted to be positive but are actually negative, and that are predicted to be negative but are actually positive, respectively. To further evaluate classification performance across imbalanced classes, precision, sensitivity, specificity, F1-score, and AUC as given by Equations (10)–(14) are presented.

For these metrics, macro and weighted values were calculated. To treat every class equally, regardless of size, and to reflect performance on minority classes, the macro metrics calculate the arithmetic mean of the scores across all classes. The weighted metrics, on the other hand, give greater weight to the majority classes as they calculate the average scores by taking the class distribution into account.

Additionally, Cohen’s Kappa was used for performance evaluation, which is especially important for an imbalanced dataset.

where , the same as with the accuracy, indicates the observed agreement. means the expected agreement with the probability of a random model making a correct prediction.

5.3. Inverter-Driven Dataset Experimental Results

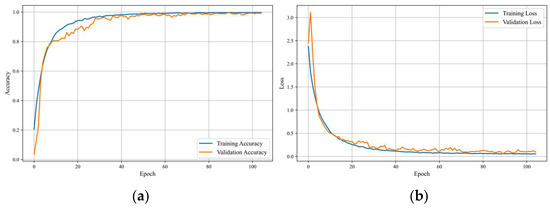

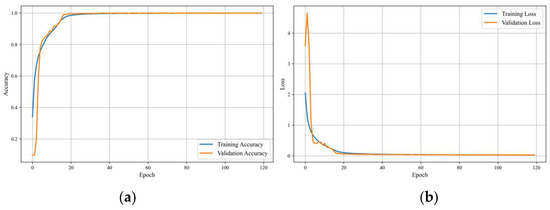

The inverter-driven dataset was selected as the first evaluation dataset for the proposed model. The learning curves for the proposed hybrid model are illustrated in Figure 10, together with the training and validation loss/accuracy. As shown in the figure, the proposed hybrid 1DCNN–BiGRU model exhibits the strongest convergence behavior after the 20th epoch, with both training and validation accuracies very close to each other, exceeding 95%. Both curves show that the model progressively enhanced its learning performance. Concurrently, the validation loss steadily dropped and eventually converged to a very low value. The validation accuracy is obtained as 99.44% for this dataset. The training and validation curves are very close to each other, indicating that the model does not overfit the data and can generalize with high accuracy, even on new, unseen data.

Figure 10.

Training and validation (a) accuracy and (b) loss curves of the proposed hybrid model for the inverter-driven dataset.

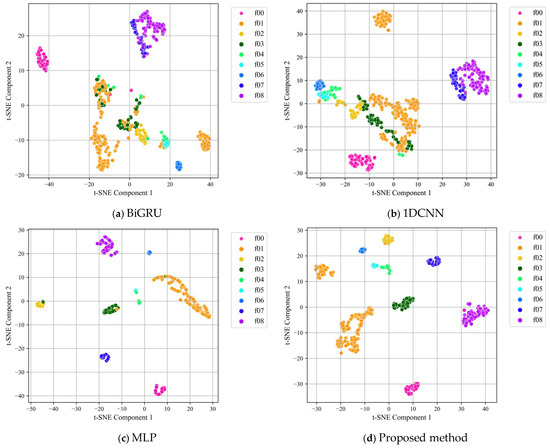

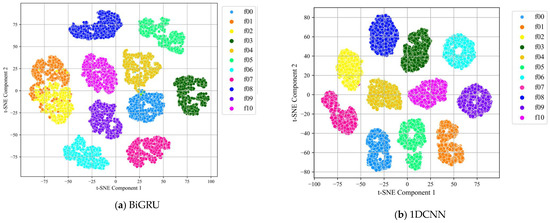

t-SNE is a dimensionality reduction technique designed for visualizing high-dimensional and continuous feature representations learned by artificial neural networks. The complex feature space is reduced to two dimensions using the t-SNE method, and the clustering of classes is visualized, as shown in Figure 11, to demonstrate the quality of the discriminative features learned by the hybrid model from the handcrafted features. The t-SNE plot of the hybrid 1DCNN–BiGRU model visually supported the high accuracy of the model, showing a near-perfect segregation between all failure classes. The clusters of each failure class formed clear and non-mixing regions. Some classes are more dispersed or their boundaries are more uncertain than in the hybrid model for the 1DCNN model, which is the closest in accuracy to the proposed model. A tree-based ensemble method, Random Forest, is not standard practice as it does not produce such a feature space; this visualization was not applied to the RF model.

Figure 11.

t-SNE visualization for the inverter-driven dataset.

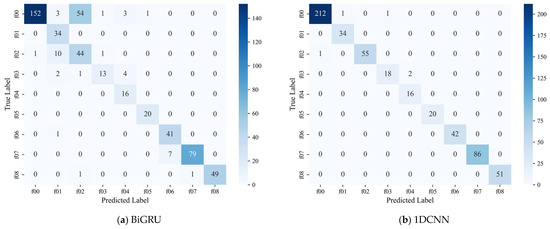

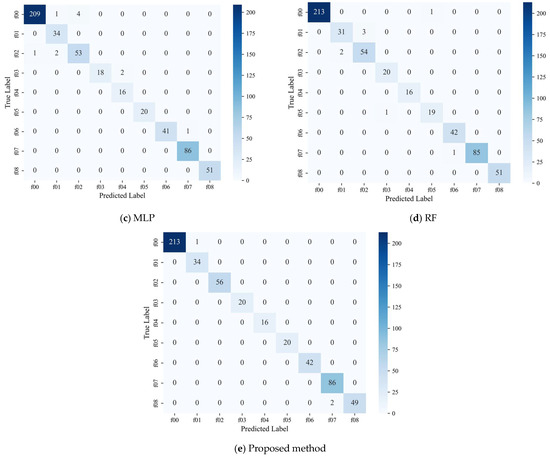

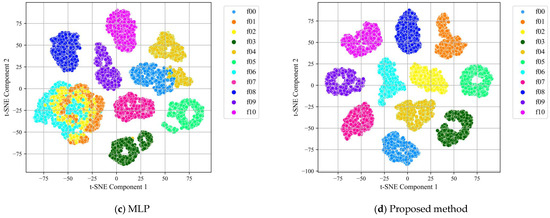

Additionally, confusion matrices were obtained for each of the models—1DCNN, BiGRU, MLP, RF, and the proposed 1DCNN–BiGRU—to graphically illustrate their classification strengths and misclassification trends. These matrices are shown in Figure 12, which offers important information about how well each model differentiates between the various fault classes. As can be seen from the confusion matrices, the majority of the samples are correctly categorized along the diagonal, demonstrating the model’s strong discriminative power with the proposed hybrid model. It correctly classified almost all of the fault classes on the diagonal. The BiGRU-only model shows the weakest performance, indicating that processing only sequential data is insufficient for PMSM fault detection.

Figure 12.

Confusion matrices for the inverter-driven dataset.

5.3.1. Handcrafted Features Ablation Study for Inverter-Driven Dataset

Handcrafted features from the signals provide crucial information for precise classification in the context of PMSM FDD. These characteristics capture different facets of the system’s dynamic behavior, including time-domain statistical metrics, frequency-domain FFT components, and multi-level wavelet coefficients. As it is unclear how each of these feature types contributes to the overall performance of the model, an ablation study was performed using each type of handcrafted feature as well as the raw signal data. This analysis allowed assessment of the individual contribution of each feature set and comparison of their effectiveness. Table 4 presents the results of the handcrafted features ablation study for the inverter-driven dataset. The comparison includes four input representations—raw sensor data, statistical features, FFT-based features, and wavelet-based features—as well as a fifth configuration that combines all handcrafted features together. The results were evaluated on both weighted and macro averages.

Table 4.

An ablation study for the handcrafted features for the inverter-driven dataset.

The primary focus of this ablation study is to systematically evaluate the impact of feature engineering on the performance of deep learning models. As demonstrated in the table results, the “multi-domain feature fusion” configuration exhibits superior performance across all principal metrics. The high Cohen’s Kappa (0.99) and AUC (99.99%) confirm the robustness of the model’s learned feature representation against chance, while the exceptional specificity (99.92%) highlights its critical capability to minimize false alarms in an industrial setting. Coupled with a low inference time of 1.45 ms/sample, these metrics collectively validate the proposed feature fusion methodology as a highly reliable, balanced, and computationally efficient solution for real-time PMSM fault classification.

Among individual feature categories, the wavelet-based representation achieves the strongest results. The wavelet-based features demonstrated superior performance compared to FFT-derived features across multiple evaluation metrics when employed as a standalone feature set. Specifically, the wavelet features achieved an accuracy of 98.70% versus 97.40% for FFT features, an F1-score of 98.71% versus 97.41%, and, notably, a macro-averaged sensitivity of 99.20% compared to 95.88% for FFT features. These findings confirm that features extracted via the db4 wavelet transform exhibit significantly enhanced discriminative capability relative to FFT features in characterizing localized, transient, and time-variant spectral components inherent in motor fault signatures. Additionally, the elevated macro-averaged sensitivity metric is especially noteworthy, as it indicates robust detection performance across all fault classes, including minority classes that are typically underrepresented in imbalanced datasets. Specificity (macro) represents the average specificity across all classes, with equal weighting. When the two values are so close to each other, it indicates that the specificity performance of the model is equally high and balanced for all failure classes. In addition to high accuracy and sensitivity, achieving high specificity directly improves operational efficiency. The high specificity of the model proves that the model has minimized false alarms in the system. A false alarm leads to unnecessary downtime, control, and maintenance costs. Therefore, the model’s ability to confirm the absence of failure with 99.93% confidence is one of the strongest indicators that the proposed solution can be used reliably and cost-effectively in the field. The wavelet transform’s capacity for simultaneous time–frequency localization renders it particularly well-suited for capturing the non-stationary dynamics, even with data acquired non-systematically.

Even when statistical features are used alone, a high accuracy (98.52%) and F1-score (98.53%) are achieved. However, reflecting the discriminative capacity of time-domain statistics (RMS, variance, and kurtosis) is fundamentally limited to characterizing global amplitude variations under stationarity assumptions. Motor faults manifest as frequency-specific signatures, sideband modulations, harmonic distortions, and transient spectral components that are intrinsically non-stationary and load-dependent. Statistical metrics, operating exclusively in the time domain, cannot resolve these fault-characteristic frequency components or their temporal localization. Thus, despite achieving adequate classification performance for pronounced faults, this methodology lacks the spectral resolution necessary for incipient fault detection, fault-type differentiation, and prognostic capability, which are essential for physics-informed predictive maintenance strategies.

As a result, the superior performance of the fused feature set, which incorporates time, spectral, and time–frequency components, confirms the necessity of a multi-domain approach. Multi-domain feature fusion creates a more comprehensive and robust signal representation, enabling the hybrid 1DCNN–BiGRU model to extract deeper, physically meaningful correlations between the extracted features and the specific fault modes. This integration not only improves numerical accuracy but also enhances the model’s generalizability and diagnostic confidence across all operating conditions, which is crucial for transitioning from simple pattern recognition to reliable, physics-informed condition monitoring in industrial applications.

This ablation study clearly demonstrates that in the inverter-driven dataset signals (Figure 3, Figure 4 and Figure 5), which encompass current, voltage, and temperature signals, handcrafted feature extraction plays a pivotal role in enhancing interpretability and discriminative power prior to deep model training.

5.3.2. Architectural Ablation Study for Inverter-Driven Dataset

An ablation study evaluating the individual and combined contributions of convolutional and recurrent components within the proposed architecture is presented in Table 5. Specifically, three configurations were analyzed: BiGRU-only (purely recurrent), 1DCNN-only (purely convolutional), and the hybrid 1DCNN–BiGRU model (integrated convolutional–recurrent structure). The comparative evaluation includes accuracy, macro, and weighted values for precision, sensitivity, F1-score, specificity, and AUC, as well as Cohen’s Kappa, inference latency, and training time.

Table 5.

Performance metrics of the architectural ablation study for the inverter-driven dataset.

The results clearly indicate that the hybrid model proposes the most consistent and superior performance across all evaluation metrics. However, the 1DCNN-only configuration, although computationally efficient (0.32 ms/sample) and highly accurate (99.07%), performs slightly below the hybrid model, particularly in terms of sensitivity and macro-averaged precision. As is known, 1DCNN can only capture temporal or sequence dependencies in short local windows, which leads to the inability of 1DCNN to fully model temporal relationships. Therefore, 1DCNN may miss correct examples in some classes (false negatives increase), resulting in a decrease in sensitivity. As a result, while convolutional filters effectively learn spatial feature patterns (high accuracy), the absence of recurrent dynamics prevents the model from forming temporal context awareness, resulting in reduced sensitivity and macro-level generalization. The BiGRU-only configuration exhibits substantially lower accuracy (83.12%) and sensitivity (83.12%), but shows relatively higher weighted precision (88.99%), reflecting the limited feature extraction capacity of a standalone recurrent design.

When used as a hybrid structure, the 1DCNN component primarily captures localized spatial dependencies across sensor signals, effectively learning characteristic waveform distortions, voltage fluctuations, and transient current peaks that typically occur under fault conditions. By sliding convolutional filters over time windows, 1DCNN automatically detects amplitude variations and repetitive fault patterns without requiring manual signal segmentation, resulting in a compact yet discriminative set of local features. While 1DCNN acts as a spatial feature encoder, BiGRU functions as a temporal integrator—capturing both forward and backward dependencies in the multi-channel time series. This enables the model to differentiate subtle phase shifts, time-lagged responses among current and voltage channels, and slow thermal dynamics that evolve during fault progression.

These ablation studies confirm that the synergistic combination of convolutional feature extraction and bidirectional recurrent temporal modeling significantly enhances both spatial–temporal representation learning and classification stability. Consequently, the hybrid 1DCNN–BiGRU architecture provides the optimal balance between accuracy, robustness, and computational efficiency among the tested variants.

Additionally, a comparative study presented in Table 6 was conducted for two conventional methods, MLP and RF. While RF exhibits competitive accuracy (98.52%) and low inference latency ( 0.0015 ms/sample), its performance remains limited by its shallow feature abstraction capability. Similarly, the MLP model demonstrates strong specificity (99.67%) but slightly reduced sensitivity (97.96%) and generalization capacity, suggesting difficulty in capturing nonlinear temporal dependencies across time-series features. In contrast, the hybrid 1DCNN–BiGRU benefits from convolutional layers and recurrent layers, yielding the highest performance metrics. These findings confirm the superior discriminative power and reliability of the hybrid deep learning approach compared to traditional machine learning classifiers.

Table 6.

Baseline comparative study for the inverter-driven dataset.

5.3.3. Cross Validation with 5-Fold for Inverter-Driven Dataset

Cross-validation is a statistical resampling technique employed to assess the performance of machine learning and deep learning models on unseen data with maximal objectivity and precision [51]. For this study, the K-fold cross-validation technique was employed, with a k value of 5. Table 7 presents the average metrics across all folds, including the mean and standard deviation.

Table 7.

Hybrid 1DCNN–BiGRU model performance across 5-fold cross-validation for the inverter-driven dataset.

This table demonstrates the outstanding stability and generalization capability of the proposed hybrid architecture. Across five folds, the model achieves an average accuracy of 99.26%, a macro F1-score of 98.87%, and a macro-AUC of nearly 99.99%, indicating exceptional discrimination ability across all classes. The minimal standard deviations (e.g., ±0.38 for accuracy) confirm consistent convergence and low variance across folds. Moreover, the macro specificity at 99.89% supports the robustness of the false-positive control even in less frequent fault classes. These findings highlight the efficiency of the hybrid configuration.

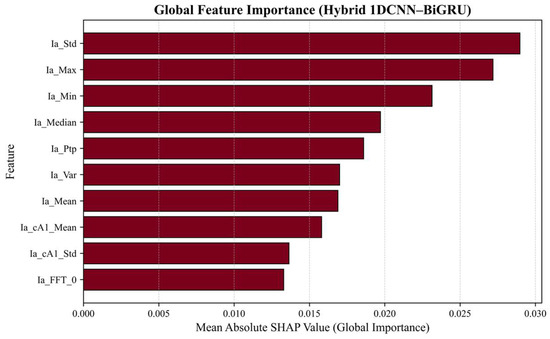

5.3.4. Explainability (XAI) Analysis for Inverter-Driven Dataset

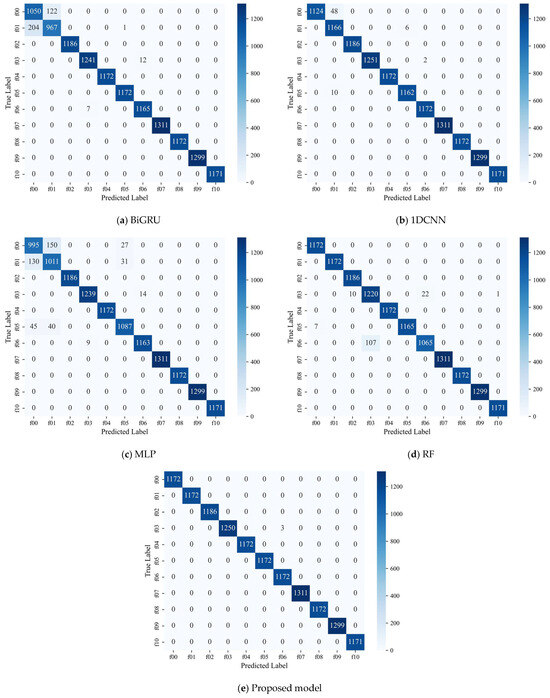

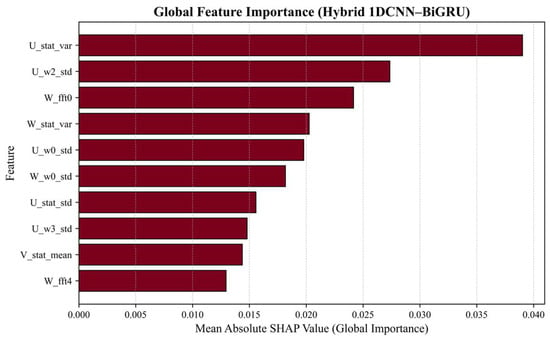

Feature importance was determined using the SHAP method, a key tool in the field of XAI, to further interpret which features most significantly affect the model’s global predictions. Figure 13 presents the global feature importance distribution for the inverter-driven dataset. The Mean Absolute SHAP value on the x-axis represents the average of the absolute contribution of a feature over the entire dataset, indicating its global importance. This figure clearly demonstrates that the statistical and frequency/wavelet domain characteristics of the motor current (Ia) have a significant influence on the model’s decision-making process.

Figure 13.

Global SHAP-based feature importance for the inverter-driven dataset.

In the model’s SHAP analysis, almost all of the most important features are derived solely from the A-phase current (Ia) signal, which has strong implications for both the nature of the failure mechanics and the learning strategy. The primary reason for this is that the types of faults investigated (especially the open-circuit and short-circuit faults from f01 to f05) are directly related to the power circuit, and such faults momentarily change, interrupt, or short-circuit the current path to the motor phases. A fault in a phase switch directly disturbs the amplitude, harmonic content, and symmetry of the waveform of the current (Ia). The DC bus current and voltage do not directly indicate the effect of the fault, as is the case with the temperatures of the half-bridge sub-circuits (T1, T2, and T3). Even if the B-phase current (Ib) is affected by the fault, the location of the fault (e.g., a fault in the phase A switch) makes the effect on Ia more pronounced and earlier than the effect on Ib. As a result, the Ia current shows the fastest and most obvious reflection of the fault.

The top rows of the graph show that the basic statistical measurements of the current signal are the most critical inputs for the model to detect faults: The parameter that best captures unexpected deviations resulting from motor faults is the standard deviation, which quantifies the ripple and irregularity in the current signal. This finding supports the hypothesis that faults lead to significant alterations in the amplitude distribution of the motor current. The second and third most important features, the maximum and minimum current values, indicate that the model detects fault-induced current spikes or dips directly through these extreme values. The lower rows of the graph show the frequency- and wavelet-domain-derived features (Ia_cA1_Mean, Ia_cA1_Std, and Ia_FFT_0). These features are the mean and standard deviation values of the Ia approximation coefficient of the db4 wavelet transform, as well as the zeroth frequency component of the Fourier transform. While the wavelet coefficients represent the low-frequency components of the signal, the FFT component shows that even changes in the DC shift signal play a role in differentiating the fault types.

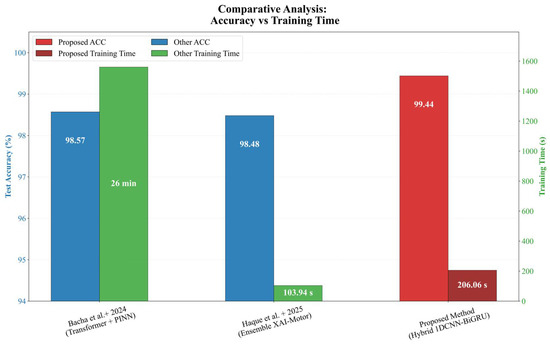

5.3.5. Comparative Evaluation with Existing Studies for Inverter-Driven Dataset

Table 8 presents the position of the proposed study within the literature, which includes studies that utilized the same dataset. The proposed recent framework surpasses existing models, such as the Transformer-based PINN [42] and Ensemble XAI-Motor [44], in terms of accuracy, generalization, and inference efficiency. Notably, the proposed model achieves 99.44% accuracy and 1.45 ms/sample inference latency while maintaining a strong macro-level balance (precision, recall, and F1 ≈ 99.4%), thereby demonstrating superior diagnostic precision under real-world operational conditions.

Table 8.

Comparison of the proposed approach, feature extraction methods, generalization, and validation status, as well as evaluation metrics in the literature using the same inverter-driven dataset.

Additionally, Figure 14 presents a comparison of studies that used the same dataset, examining accuracy and training time. The proposed hybrid model (99.44% accuracy) exhibits higher fault diagnosis accuracy than its competitors (98.57% and 98.48%), while its training time (206 s) is longer than that of the Ensemble XAI model (104 s), but significantly faster than the Transformer-based model (1560 s).

Figure 14.

Comparison of the models for the same inverter-driven dataset (Bacha et al. + 2024: [42]; Haque et al. + 2025: [44]).

5.4. Stator Winding Fault Dataset Experimental Results

The stator winding fault dataset was chosen for its popularity in the current literature [46]. This dataset comprises 48 vibration and 48 current data files in Technical Data Management Streaming (.tdms) format. Eleven different classes with various properties (inter-turn, inter-coil, various power levels, etc.) were chosen for this study. The training and validation accuracy and loss curves are presented in Figure 15 to further illustrate the learning behavior of the proposed model. These curves indicate fast and steady convergence, with accuracy and loss approaching near-optimal values in the early epochs. The hybrid 1DCNN–BiGRU architecture successfully learns discriminative temporal–spatial patterns and attains a dependable optimization performance throughout the learning process, as evidenced by the consistent trend both during training and validation.

Figure 15.

Training and validation (a) accuracy and (b) loss curves of the hybrid model for the stator winding fault dataset.

To illustrate the classification performances of the proposed, singular type, and baseline models, t-SNE graphics are shown in Figure 16. BiGRU’s clusters partially overlap, indicating limited spatial discrimination, despite capturing temporal dependencies. The 1DCNN model generates more compact clusters, indicating stronger local pattern extraction, although some inter-class blending remains. On the other hand, MLP produces diffuse and highly mixed clusters, demonstrating its inadequate representational capability for intricate temporal–spectral patterns. The hybrid model’s performance is clearly evident. This figure illustrates how effectively the features learned in the hidden layers of the hybrid model discriminate between different failure classes.

Figure 16.

t-SNE visualization for the stator winding fault dataset.

According to the confusion matrices in Figure 17, the proposed hybrid model shown in Figure 17e achieves a nearly flawless classification performance across all fault categories. There are no notable misclassifications found, and each class (f00–f10) is mapped nearly exclusively to its matching predicted label. The model has effectively learned the discriminative characteristics of various stator winding fault types, as evidenced by the diagonal influence, which guarantees precise fault separation even between conditions that are closely related.

Figure 17.

Confusion matrices for the stator winding fault dataset.

5.4.1. Handcrafted Features Ablation Study for Stator Winding Fault Dataset

The results of the handcrafted features ablation study for the stator winding fault are presented in Table 9. The results are acquired from the raw signal and training with four feature configurations separately: statistical, FFT, wavelet, and their fusion. The close alignment of weighted and macro metrics indicates a uniformly strong performance across classes. The model achieved a high performance (96.66% accuracy and 0.96 Cohen’s Kappa) even on raw data. This confirms the hybrid 1DCNN–BiGRU architecture’s ability to extract relevant features even from the raw signal. However, the use of raw data required the longest training time, at 904.71 s, and yielded the lowest accuracy/F1-score values of the model. The statistical (99.87%) and wavelet (99.89%) features provide an increase of over 3.2 points in accuracy compared to the raw data, demonstrating the importance of efficiently encoding distortion information in the raw signal. All attribute engineering approaches have greatly reduced training time compared to raw data. This shows that enriched feature sets significantly increase the convergence speed of the model.

Table 9.

An ablation study for the handcrafted features in the proposed model for the stator winding fault dataset.

By comparison, feature-engineered representations achieve near-ceiling results: statistical and wavelet features reach accuracies of 99.87% and 99.89%, respectively, with an AUC of approximately 100%, while also reducing inference latency to approximately 0.17–0.20 ms. With the shortest training time (337.58 s; approximately 2.7-times faster than raw) and 4.9-times lower latency, wavelet-only provides the best Pareto trade-off among single families (ACC 99.89%, Cohen’s Kappa 1.00). Using multi-domain feature fusion attains the highest accuracy (99.98%) and Cohen’s Kappa (1.00), albeit with a longer training time (485.92 s). As a result, wavelet-only is preferable under real-time or resource-constrained conditions, whereas the multi-domain feature-fusion case is justified when maximizing accuracy is critical.

5.4.2. Architectural Ablation Study for Stator Winding Fault Dataset

An expanded ablation study for the developed models on the stator winding fault dataset is presented in Table 10, revealing the contribution of each component and the synergy of the hybrid structure. When used alone, BiGRU exhibits strong baseline performance, achieving an accuracy of 97.39% and a Cohen’s Kappa of 0.97. The 1DCNN-only model achieved a significantly higher accuracy of 99.50% and a Cohen’s Kappa of 0.99 compared to BiGRU. This demonstrates that, in the feature set enriched with statistical, Fourier, and wavelet transforms, the distinctive local and high-frequency signal patterns of the fault are dominant, and 1DCNN efficiently extracts these patterns. 1DCNN also demonstrated the fastest performance, with an extraction time of 0.08 ms/sample and a training time of 136.91 s. The hybrid 1DCNN–BiGRU model significantly outperforms both the pure 1DCNN and the pure BiGRU models. The hybrid model achieved arguably the highest classification performance, with 99.98% accuracy, a 99.98% macro F1-score, and a Cohen’s Kappa of 1.00. These results demonstrate that the model exhibits nearly perfect stability and accuracy across all failure classes. Although the hybrid model requires a longer training time (485.92 s) than only 1DCNN, its maximum accuracy and low inference time of 0.20 ms/sample prove that this architecture represents the optimal balance between performance and efficiency.

Table 10.

Performance metrics of the architectural ablation study for the stator winding fault dataset.

An additional comparative study was conducted to evaluate the performance of the proposed model against two classical models trained on the same multi-domain feature set. The results of this comparison are shown in Table 11. The hybrid model achieved the highest accuracy, 99.98%, compared to MLP with 96.63% and RF with 98.89%. The F1-score (weighted and macro) values, the most critical balance metrics, were recorded at 99.98%. This result demonstrates that the hybrid model can accurately diagnose all failure classes with precision and sensitivity, without exception. Despite RF and MLP’s ability to leverage the power of handcrafted features, their ability to capture intricate and hierarchical nonlinear relationships between features is limited: While the hybrid model is slow (485.92 s) and RF is very fast (0.31 s) in terms of training time, the accuracy gain offered by the hybrid architecture demonstrates that in complex industrial systems, reliability is more important than training cost. As a result, the hybrid architecture provides the most reliable, balanced, and accurate solution for fault diagnosis.

Table 11.

Baseline comparative study for the stator winding fault dataset.

5.4.3. Cross-Validation with 5-Fold for Stator Winding Fault Dataset

To evaluate the robustness and dataset sensitivity of the proposed architecture, 5-fold cross-validation was conducted on the stator winding fault dataset acquired under comparable experimental conditions. Table 12 summarizes all the metrics per fault class, along with the mean and standard deviation values of the 5-fold cross-validation (k-fold CV) results. The model achieved a correct classification rate of nearly 100% for the entire dataset. The differences are less than 0.001% for both the balance between classes (macro) and the sample weight, indicating that the model does not overfocus on any class. A high Cohen’s Kappa value indicates that the effect of chance categorization is almost non-existent; the consistency between folds is too high. The low standard deviations (<0.02%) demonstrate the remarkable stability and reproducibility of the model.

Table 12.

Hybrid 1DCNN–BiGRU model performance across 5-fold cross-validation for the stator winding fault dataset.

The first dataset produced an average accuracy of 99.26 ± 0.38% (Table 7), while the second dataset produced an accuracy of 99.97 ± 0.02% (Table 12). In both cases, precision, recall, and F1-scores remained above 98.7%, with AUC values approaching 100%. The slightly lower and more variable results from the first dataset suggest that the signal characteristics in that dataset exhibited higher intra-class diversity or measurement noise, despite both evaluations validating the model’s strong discriminative capability and stability across folds. In contrast, the second dataset, sampled at 100 kHz with more homogeneous waveform segments, provided almost ideal separability among fault classes. These complementary findings suggest that while the proposed model consistently achieves high accuracy across datasets, the magnitude of improvement in the second experiment may be partially attributed to the smoother and less noisy statistical features. Therefore, cross-dataset consistency supports the general reliability of the proposed architecture.

5.4.4. Explainability (XAI) Analysis for Stator Winding Fault Dataset

The graph in Figure 18 shows the global attribute importance for the proposed model. The U_stat_var, the U-phase current static statistical variance, at the top of the graph, has the highest global significance (Mean Absolute SHAP value of approximately 0.040). This indicates that the model most significantly depends on the signal variation in the U phase, and the signal instability or fluctuation is a crucial indicator. when classifying faults. The second most important attribute is U_w2_std, the standard deviation of the second-order coefficients of the U-phase db4 wavelet transform, with a value of approximately 0.028. This case demonstrates that the model is effective in capturing fault-specific signal frequency components. The third most important attribute, W_fft0, the zeroth component of the Fourier transform of the W phase, is significant at approximately 0.024. This indicates that the fundamental energy content of the signal also plays a critical role in fault discrimination. The SHAP analysis indicates the strong discriminative power of the statistical variance attributes, which are of the highest importance, followed closely by the db4 wavelet transform attributes. Additionally, this analysis confirms that the majority of the attributes come from measurements specifically on the U phase, when taking into consideration the phase contributions. This is the result of the faults in the motor, which usually leave their most obvious traces in the U-phase signals. This situation is identical to the first inverter-driven dataset.

Figure 18.

Global SHAP-based feature importance for the stator winding fault dataset.

5.4.5. Comparative Evaluation with Existing Studies for Stator Winding Fault Dataset

This dataset has been preferred in the literature because it collects data that complies with standards and encompasses a wide range of fault cases. Table 13 presents the studies that have applied their model to this dataset.

Complex feature extraction techniques, such as Gram Angular Fields and IAIUnet, are employed by models like the ECNN–BiGRU by Chen et al. [48] and the IAIUNet-SRC by Wang et al. [52]. Other researchers have investigated RF and RegNet models, such as Zhang et al. [53] and Belgacem et al. [45], frequently using wavelet packet decomposition or statistical properties for feature engineering. The number of fault classes addressed by these models varies from four to seven, and many studies lack reported generalizability despite achieving high accuracy in many cases. On the other hand, the proposed hybrid 1DCNN–BiGRU model is superior in terms of the number of classes. Classifying one healthy and ten faulty classes is a more complex task than undertaken in most other studies. Furthermore, the proposed model employs a robust feature extraction technique that combines statistical analysis, DWT with a db4 wavelet, and FFT. Additionally, the model exhibited a fast inference time (0.2 ms per sample) and a reasonable training cost (≈485.92 s), highlighting its computational efficiency compared to deep architectures such as ResNet or IAI-UNet.