1. Introduction

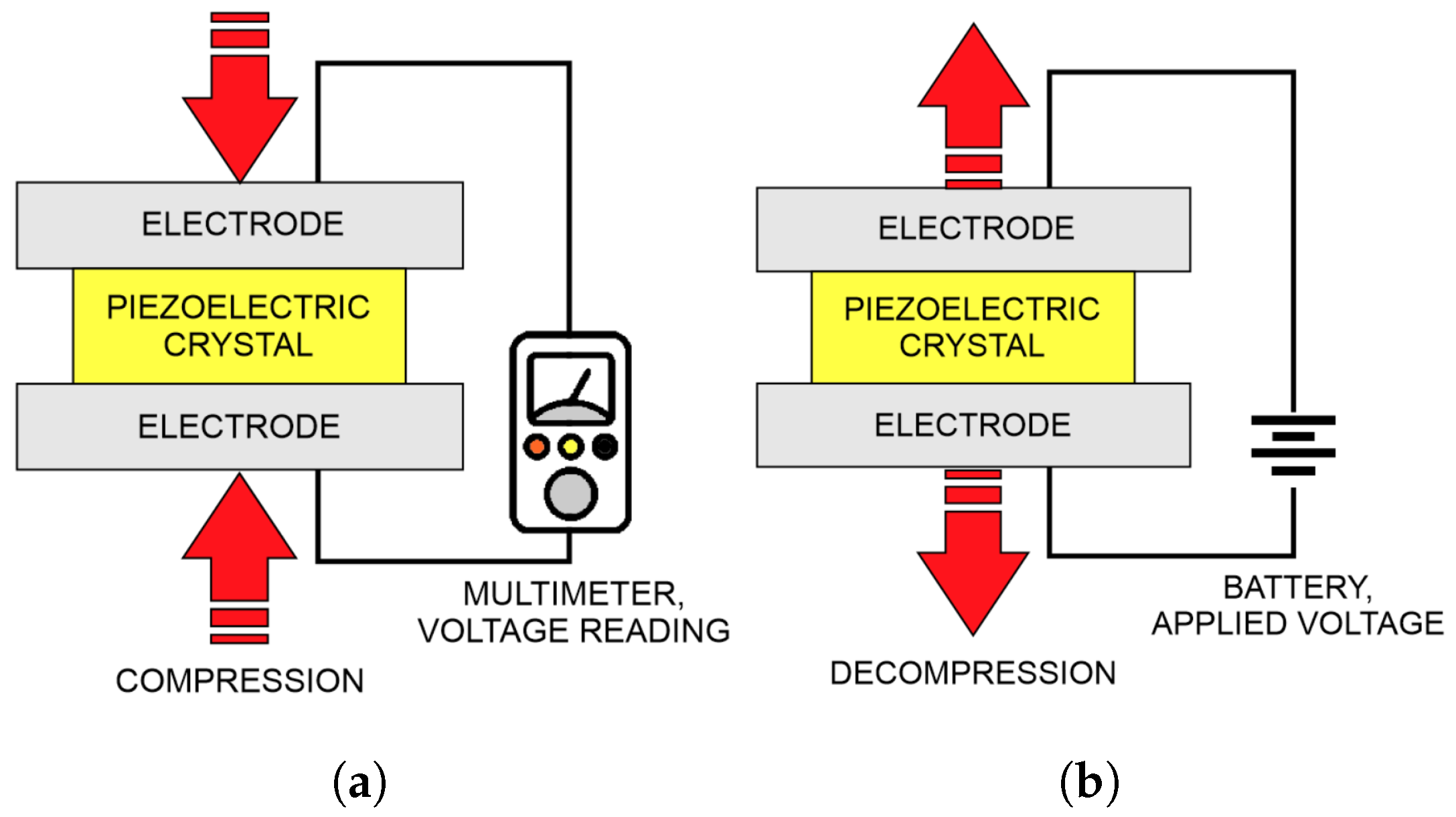

Wearable electronic systems have rapidly evolved over the past decade, driven by the growing demand for mobile health monitoring, activity tracking, and smart footwear applications. These devices often rely on batteries, which introduce limitations related to size, weight, and the need for frequent recharging. As a result, the development of autonomous, self-powered technologies has become a crucial area of research. Among the various solutions explored, energy harvesting systems based on piezoelectric and electrostatic principles stand out due to their ability to convert mechanical movements, such as those generated during walking, into usable electrical energy. In this context, piezoelectrets have emerged as a promising class of materials, offering flexibility, low cost, and efficient charge retention for energy conversion applications in wearable devices. Piezoelectricity is the phenomenon in which certain materials generate an electric charge in response to mechanical deformation or vibration a principle discovered in 1880 by Pierre Curie. This direct piezoelectric effect is caused by the internal displacement of ions, resulting in electric polarization and a measurable electric field [

1]. Conversely, when a voltage is applied, these materials undergo deformation (the reverse piezoelectric effect) [

2].

Figure 1 illustrates both the direct and reverse piezoelectric effects, highlighting the conversion of mechanical deformation into electrical signal, and vice versa.

Common piezoelectric materials include quartz, barium titanate, and lead zirconate titanate (PZT), the latter being widely used in sensors and actuators due to its strong electromechanical coupling [

3,

4,

5]. Due to the potential to generate charges and, therefore, energy, studies on energy harvesting with piezoelectric sensors have emerged recently. The recent research on piezoelectric energy harvesting for self-powered systems follows several key approaches, including system frameworks, hybrid device innovation, electronic interfaces, and materials science. The goal is to power low-power electronics and Internet of Things (IoT) devices by scavenging energy from sources like human motion, environmental vibrations, and wind [

6,

7]. A trend involves developing hybrid systems that couple piezoelectric and electromagnetic transduction mechanisms. This approach aims to broaden operational bandwidth and improve energy conversion efficiency, with applications shown in vehicle-mounted systems for harvesting wind and vibration energy, and in devices with adjustable resonant frequencies to adapt to changing environmental conditions [

8,

9]. Beyond hybrid systems, research focuses on optimizing harvesters for applications involving human–machine interaction and biomechanical energy. Innovations in mechanical design include impact-driven, press-button-type harvesters that convert human actions into electrical energy [

10]. The performance of these mechanical transducers, especially when subjected to aperiodic inputs from human motion, depends on the power management electronics. Consequently, harvesting circuits are an area of development, with interfaces employing synchronous charge extraction with load-screening schemes to maximize energy from flexible thin-film generators, or Bias-Flip techniques to enable self-powered vibration sensors with high efficiency [

11,

12]. These electronic systems are needed to manage the high-voltage, low-current outputs of piezoelectric devices and to condition the power for storage or use. Progress in the field is also driven by fundamental materials research to find sustainable and biocompatible alternatives to lead-based piezoelectric ceramics. Work has demonstrated and quantified the piezoelectric effect in bioelectret crystal films of proteinogenic amino acids, such as L-leucine [

13]. In addition to piezoelectric energy harvesters, triboelectric phenomena was also studied for the same application. An example of energy harvesting with triboelectric sensors is the development of a high-efficiency triboelectric nanogenerator (TENG) by incorporating 2D-MXene nanosheets into a PVDF-HFP tribo-layer. This approach leverages an interfacial polarization strategy to enhance the material’s dielectric properties and charge-trapping capability, achieving a peak power density of 4.9 W/m

2; from biomechanical energy sources such as human motion [

14]. The exploration of such materials presents an avenue for creating non-toxic, biodegradable, and flexible energy harvesters and sensors. This focus on new materials, combined with advancements in hybrid device architectures and power electronics, outlines a strategy to address the challenges of efficiency, bandwidth, and material safety in kinetic energy harvesting.

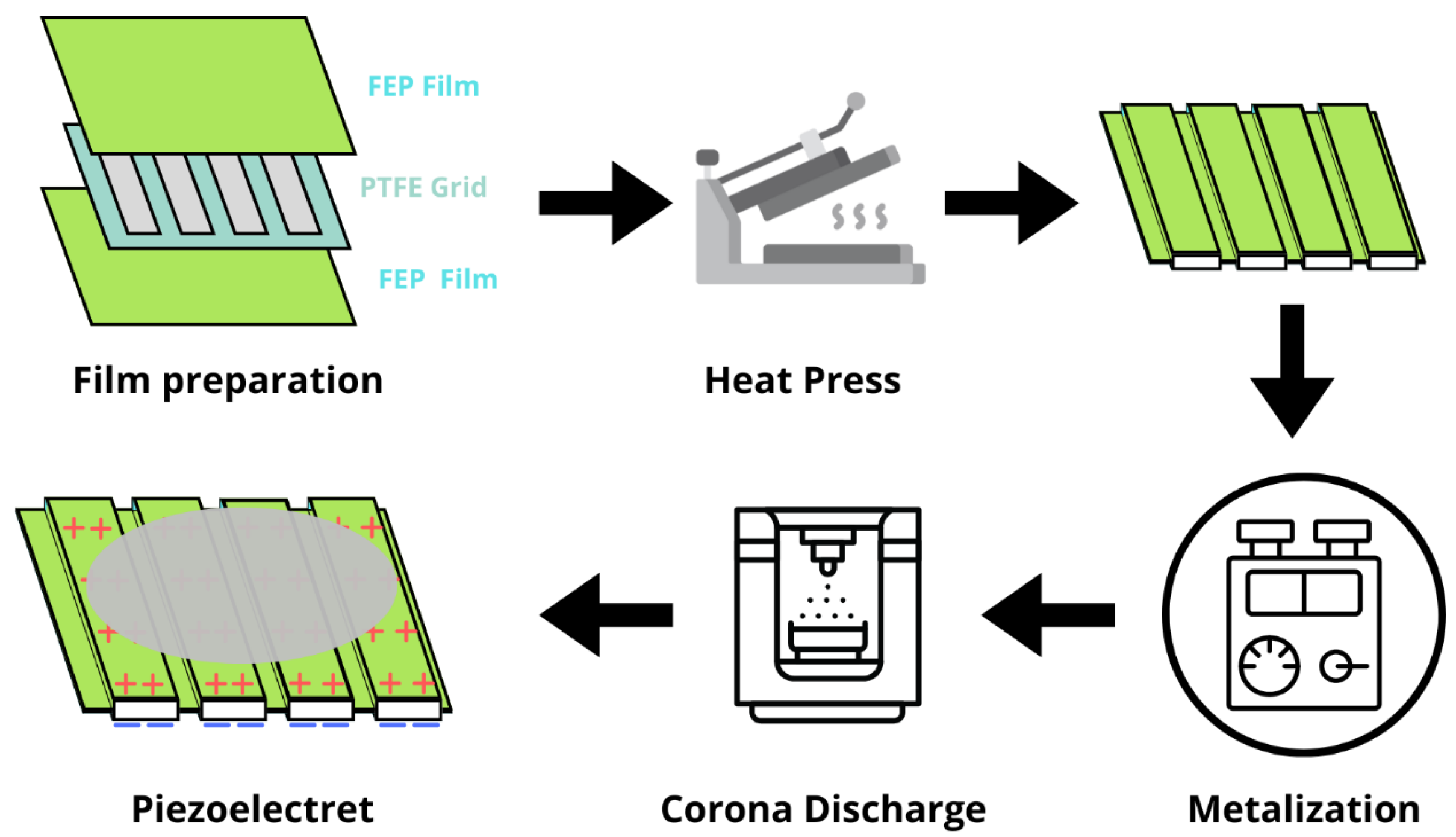

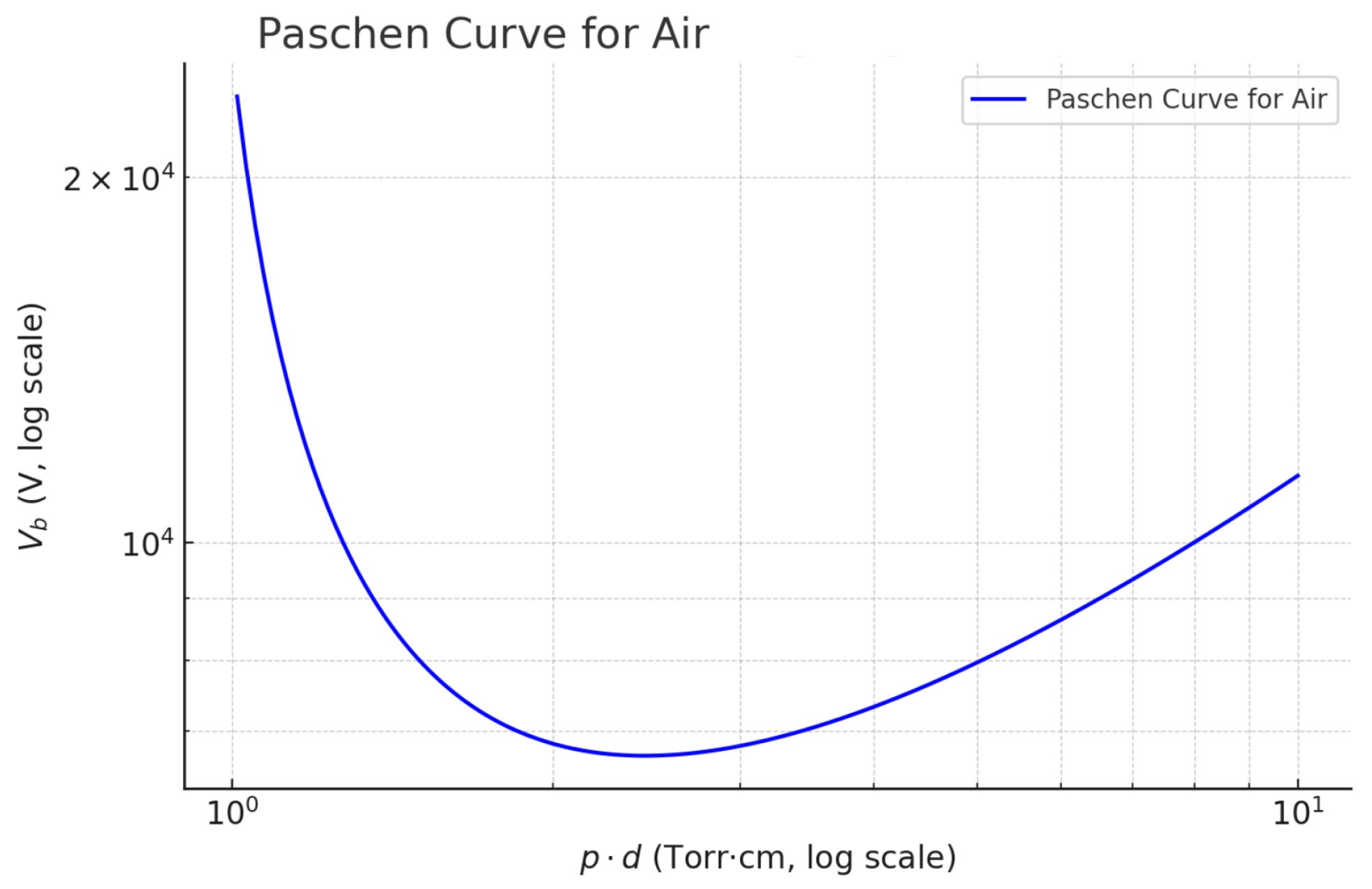

Piezoelectrets or ferroelectrets are a related class of materials that function as flexible electromechanical transducers. Unlike traditional piezoceramics, piezoelectrets consist of dielectric polymer films with internal or surface charges that persist over time. These charges are typically introduced using high-voltage techniques such as corona discharge or thermal poling [

15,

16]. Similar to the piezoelectric sensors, electret-based energy harvesters have been studied. These systems rely on improvements in theoretical modeling and physical device architecture. Accurate prediction of device performance is essential for design, and one model for rotational harvesters improves this by incorporating three-dimensional fringing effects, achieving maximum errors of only 7.2% for Cmax and 5.9% for Cmin when compared to experimental results [

17]. This model also quantifies that fringing effects can contribute up to 28.7% of the total effective capacitance, a factor often neglected [

17]. On the device level, performance is frequently limited by phenomena such as squeeze-film air damping. An innovation to mitigate this is the use of a perforated electrode, which was shown to increase the maximum power output by approximately 9.8 times at a low acceleration of 2.72 m/s

2 [

18]. These design strategies contribute to the broader goals in the field, such as achieving high power densities of up to 763 µW/cm

3, managing the ‘pull-in’ effect, and broadening the frequency bandwidth for practical applications [

19].

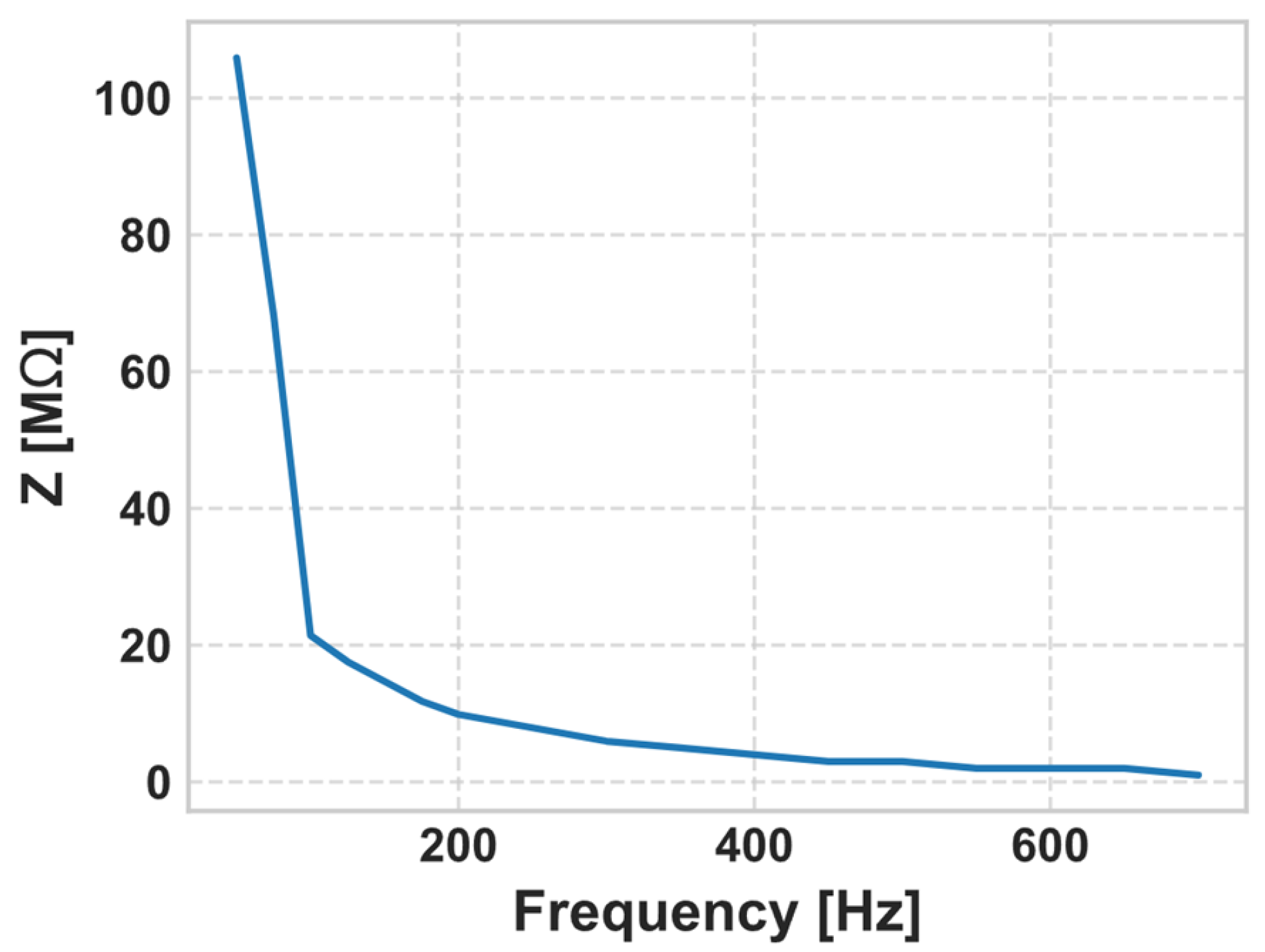

Beyond the harvester itself, advancements in power management electronics and novel applications are extending the utility of electret technology. Efficiently extracting energy from high-impedance electret sources requires specialized electronics, such as a self-powered synchronous electric charge extraction (SECE) circuit that demonstrated a 2.15-fold increase in harvested power compared to a standard buck converter, reaching a circuit efficiency of 63% at a 5 V load [

20]. The function of electret devices is also expanding to integrated systems, exemplified by a self-powered MEMS inertial switch that harvests energy from 0.3 g vibrations and triggers a wake-up signal in response to a 40 g shock [

21]. Furthermore, new charging methods and materials are being explored. A micro-patterning technique using liquid-solid contact electrification achieved a surface potential of −650 V with 82% charge retention after 45 days, enabling applications in droplet-based energy harvesting [

22]. The technology’s scope is also expanding beyond kinetic sources with the investigation of carbon-carbon composites for thermal energy harvesting, where mild heating was found to increase the material’s power density by a factor of 600 [

23].

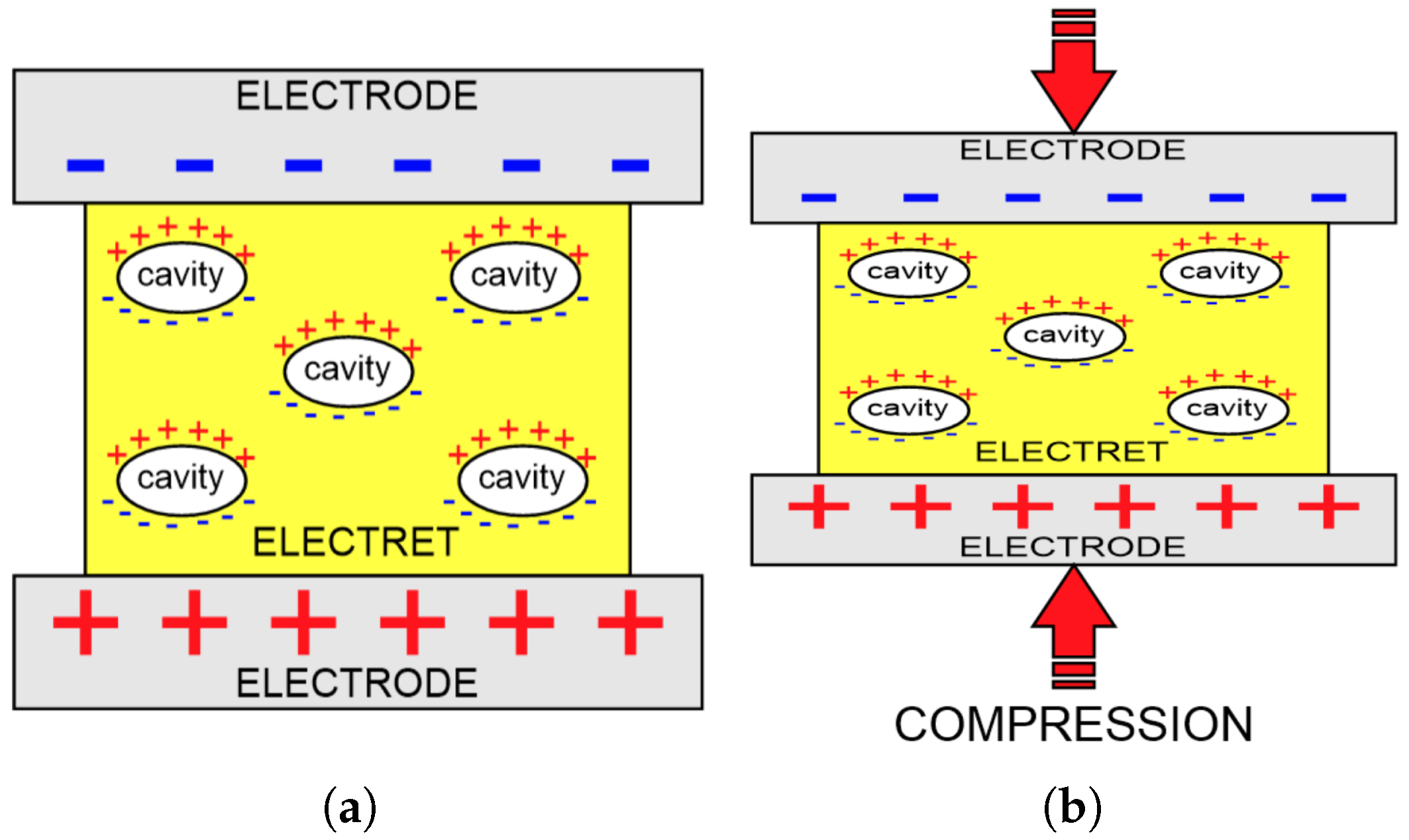

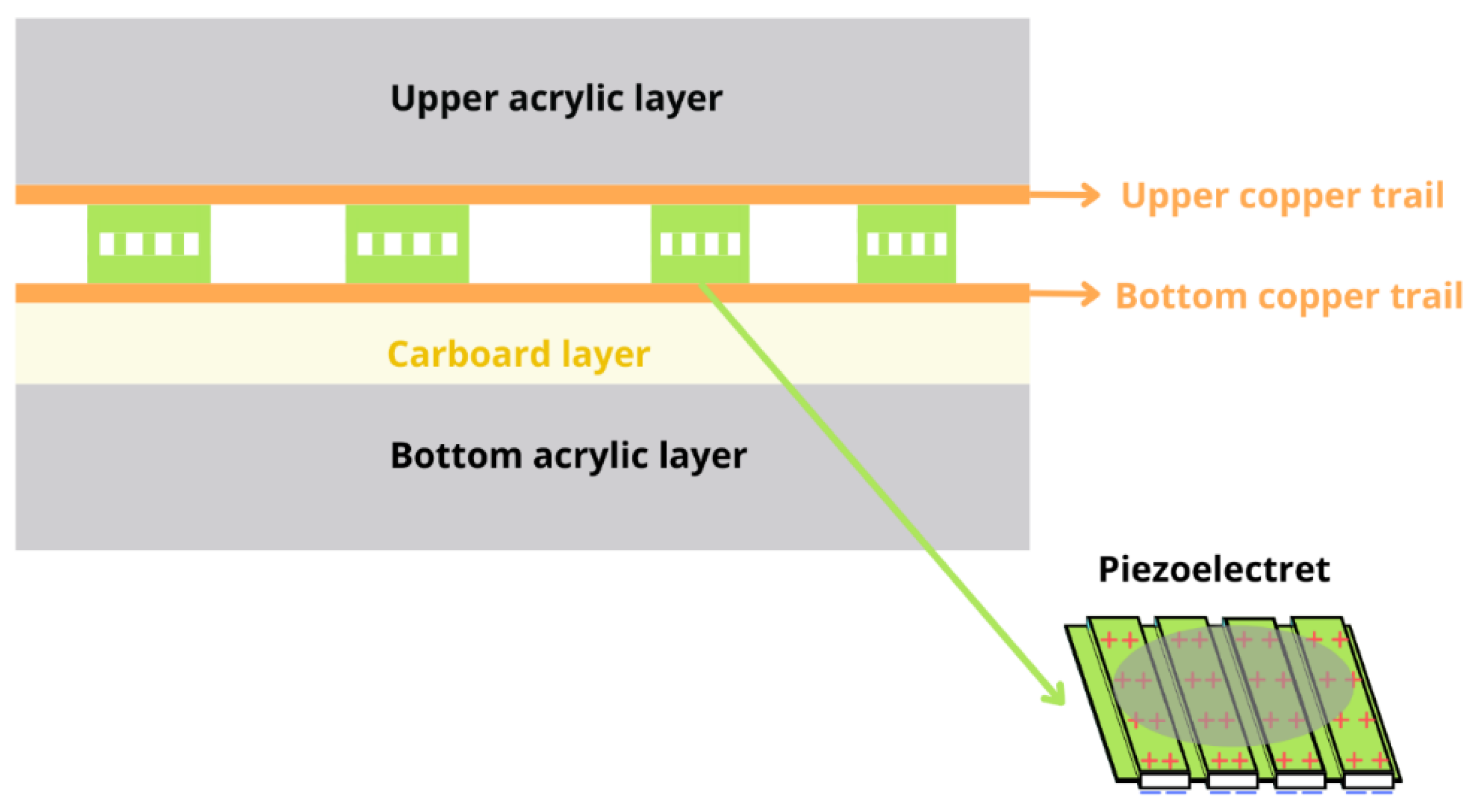

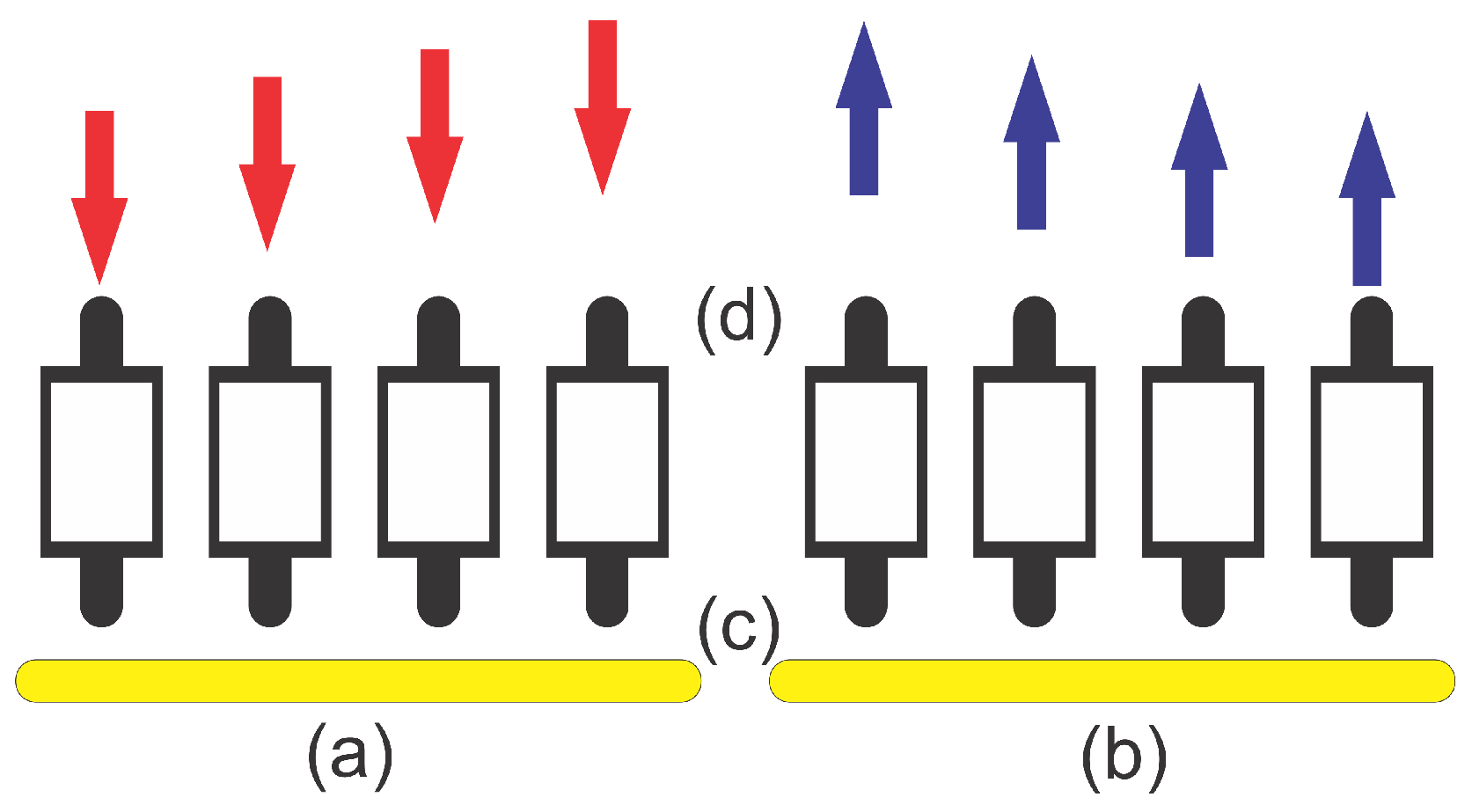

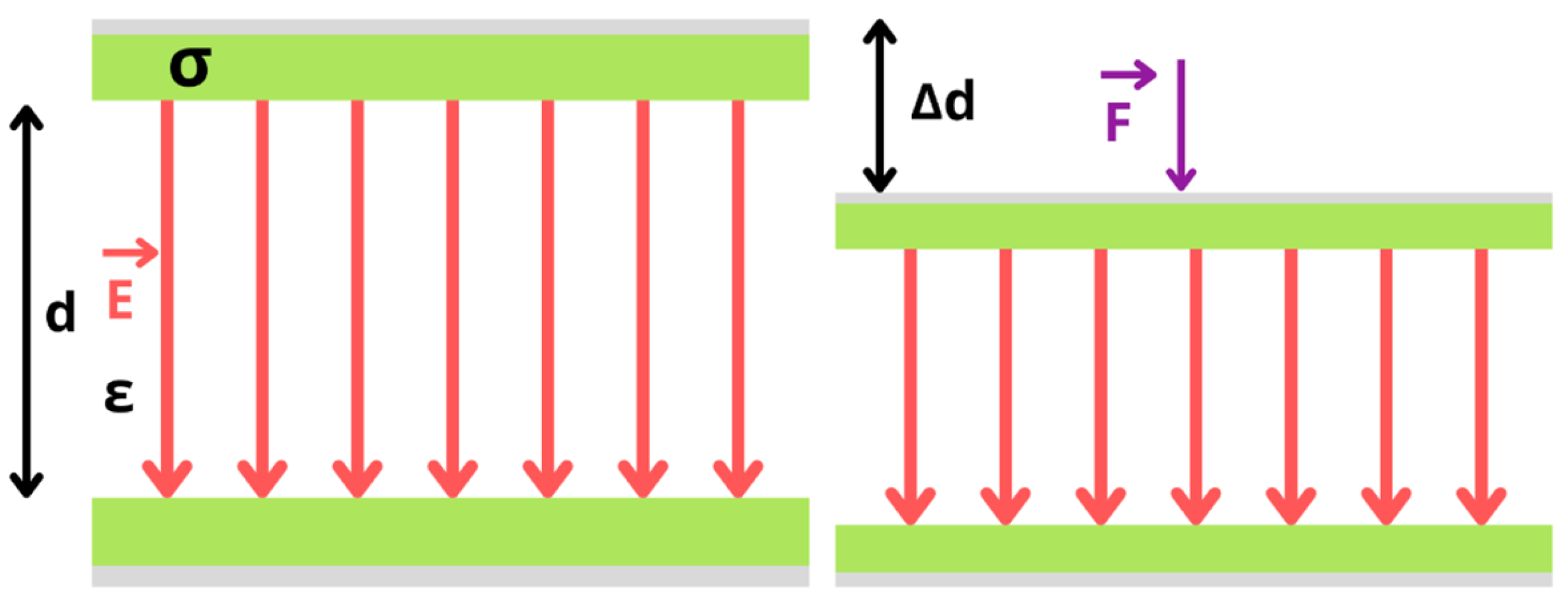

One of the defining characteristics of piezoelectrets is the presence of internal air cavities. These cavities act as regions of enhanced polarization under stress and dramatically increase the material’s sensitivity to pressure. When a compressive force is applied, the distance between the charged surfaces within the cavities changes, inducing a measurable voltage. The fundamental working principle of a piezoelectret under mechanical compression is illustrated in

Figure 2 shows how a piezoelectret responds to mechanical compression. The material consists of an electret layer with internal air cavities, placed between two electrodes.

Figure 2a, the piezoelectret is in its uncompressed state. The internal cavities are uniformly spaced, and electric charges (positive and negative) are distributed around these cavities. The piezoelectret produces a homogenous electric field for de near area of the electrodes.

Figure 2b shows the piezoelectret under compression. The applied force reduces the size of the internal cavities and brings the charges closer together. This change in geometry increases the net dipole moment, resulting in a stronger electric field and a measurable electrical signal across the electrodes.

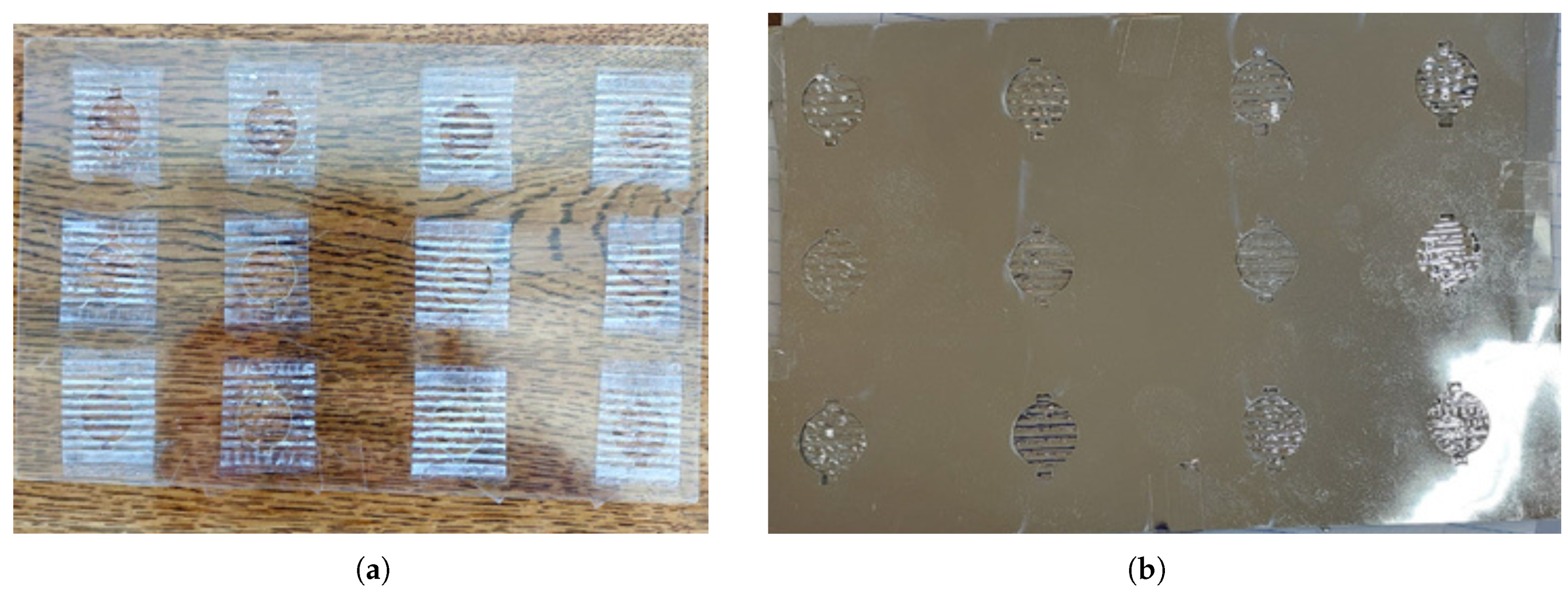

To fabricate these structures, polymers such as PTFE or FEP are used due to their excellent dielectric strength and thermal stability. The films are thermoformed to create regular internal grooves or channels and then charged through electrostatic methods to trap charges in the cavity interfaces [

24,

25]. This layered configuration creates an electromechanical response that is highly suitable for energy harvesting applications, particularly in wearable systems subjected to cyclic mechanical forces like human gait. Energy harvesting from human motion has become increasingly relevant in wearable applications, where energy autonomy is critical for user comfort and system reliability. Traditional batteries are bulky and require frequent charging, which limits the practicality of fully integrated wearable devices. Piezoelectret-based systems offer a promising alternative by converting mechanical input from walking or running into electrical energy. Their low cost, high flexibility, and capability to retain charge over time make them well suited for dynamic applications such as gait monitoring, step counting, and even GPS tracking. Recent studies have demonstrated the versatility of piezoelectrets in other fields, such as acoustic sensing and fluid analysis [

26,

27]. However, their integration into footwear for energy harvesting is still emerging as a novel and scalable approach. Piezoelectret-based systems have demonstrated significant potential for energy harvesting and sensing applications across various configurations and fabrication methods. Single-layer and stacked piezoelectret films have been studied for vibration-based energy harvesting, achieving considerable output power enhancement proportional to the number of stacked layers, highlighting the nonlinear relationship between stress and generated power [

28]. Further, advancements in geometry optimization using laser-patterned adhesive spacers have substantially improved the piezoelectric performance, showcasing enhanced dynamic piezoelectric coefficients suitable for flexible sensor applications, including human pulse and cardiovascular monitoring [

29]. Additionally, the implementation of machine learning algorithms on multifunctional piezoelectric cantilevers coated with MoS

2 (Molybdenum Disulfide) has enabled accurate simultaneous environmental sensing of parameters such as humidity, temperature, and CO

2 concentrations, demonstrating versatility and reduced complexity compared to traditional multisensor systems [

30]. Fundamental insights into the manufacturing processes and properties of piezoelectrets have further underscored their high piezoelectric performance, flexibility, and diverse fabrication techniques including additive manufacturing, which expand their applicability in sensor and actuator technologies [

31]. Moreover, advanced configurations and novel material modifications have been employed to enhance the sensitivity and applicability of piezoelectret devices. For instance, stacked piezoelectret microphones utilizing pressure-expanded polypropylene films achieved high sensitivities and low distortion, making them ideal for acoustic sensing applications [

32]. Tape-like vibrational energy harvesters made of fluorinated polyethylene propylene (FEP) piezoelectrets exhibited notable transverse piezoelectric effects and flexibility, enabling scalable designs for wearable electronic applications [

33,

34]. Further material innovation was demonstrated through incorporating polydopamine-modified tourmaline nanoparticles into polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) matrices, significantly enhancing the piezoelectric output voltage and power density for wearable self-powered devices [

35]. Finally, cross-linked polypropylene ferro/piezoelectrets have been developed into air-borne ultrasonic transducers, combining high piezoelectric activity with low acoustic impedance, thus providing improved ultrasonic emission and detection capabilities in flexible and lightweight configurations [

36].

The present work is limited to proof-of-concept validation using a custom mechanical gait simulator, chosen to ensure repeatability and avoid ethical restrictions associated with early human trials. This approach enables controlled quantification of the electrical response, while laying the groundwork for subsequent in vivo testing under real gait conditions Rather than aiming for full optimization or immediate deployment, the main objective is to demonstrate the feasibility and scalability of this low-cost and passive technology as a foundational step toward developing self-powered wearable systems.

Objective: Demonstrate the feasibility of a piezoelectret-based insole that converts human step dynamics into electrical signals suitable for future energy harvesting applications.

Goal: Lay the groundwork for the development of self-powered wearable electronics, addressing the growing demand for energy-autonomous devices.

Proposed Solution: A low-cost, scalable insole system using thermoformed Teflon piezoelectrets, integrated into a custom-built insole prototype.

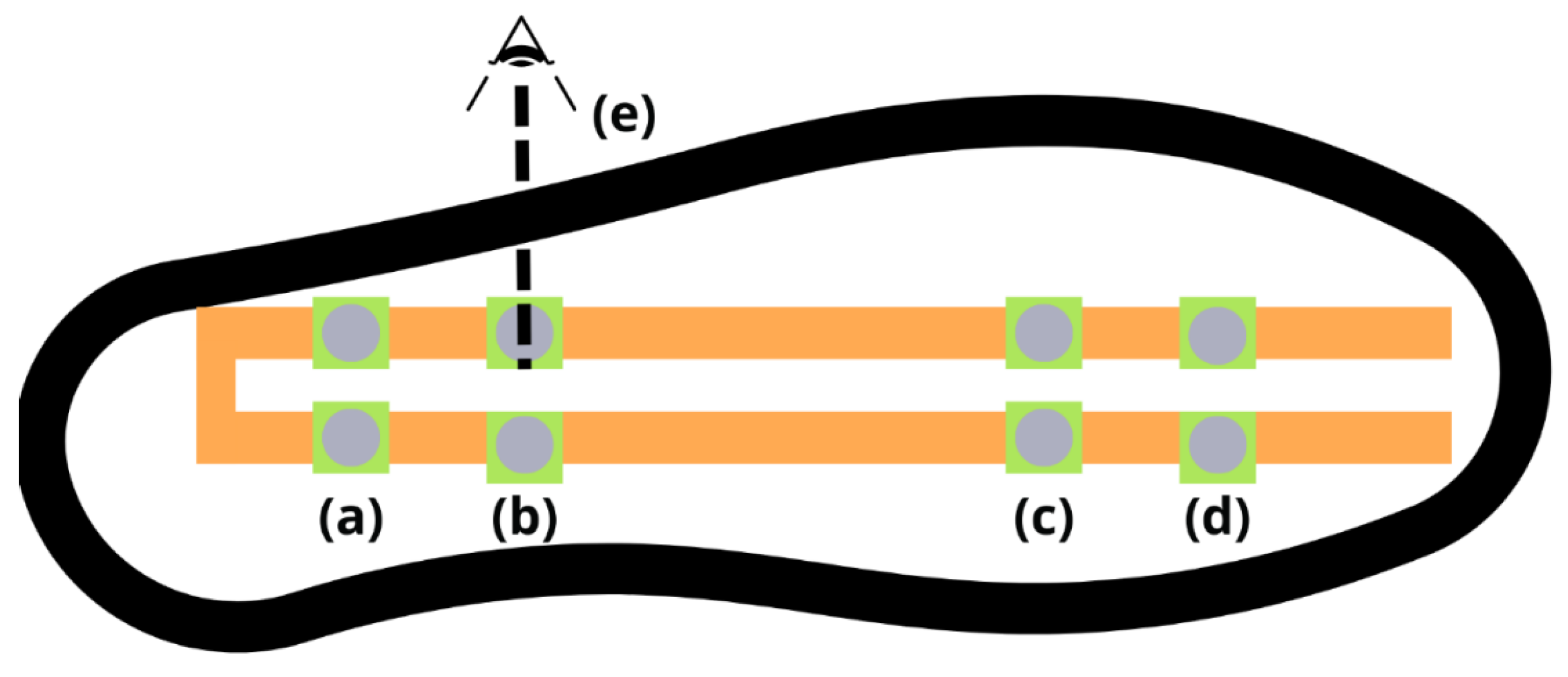

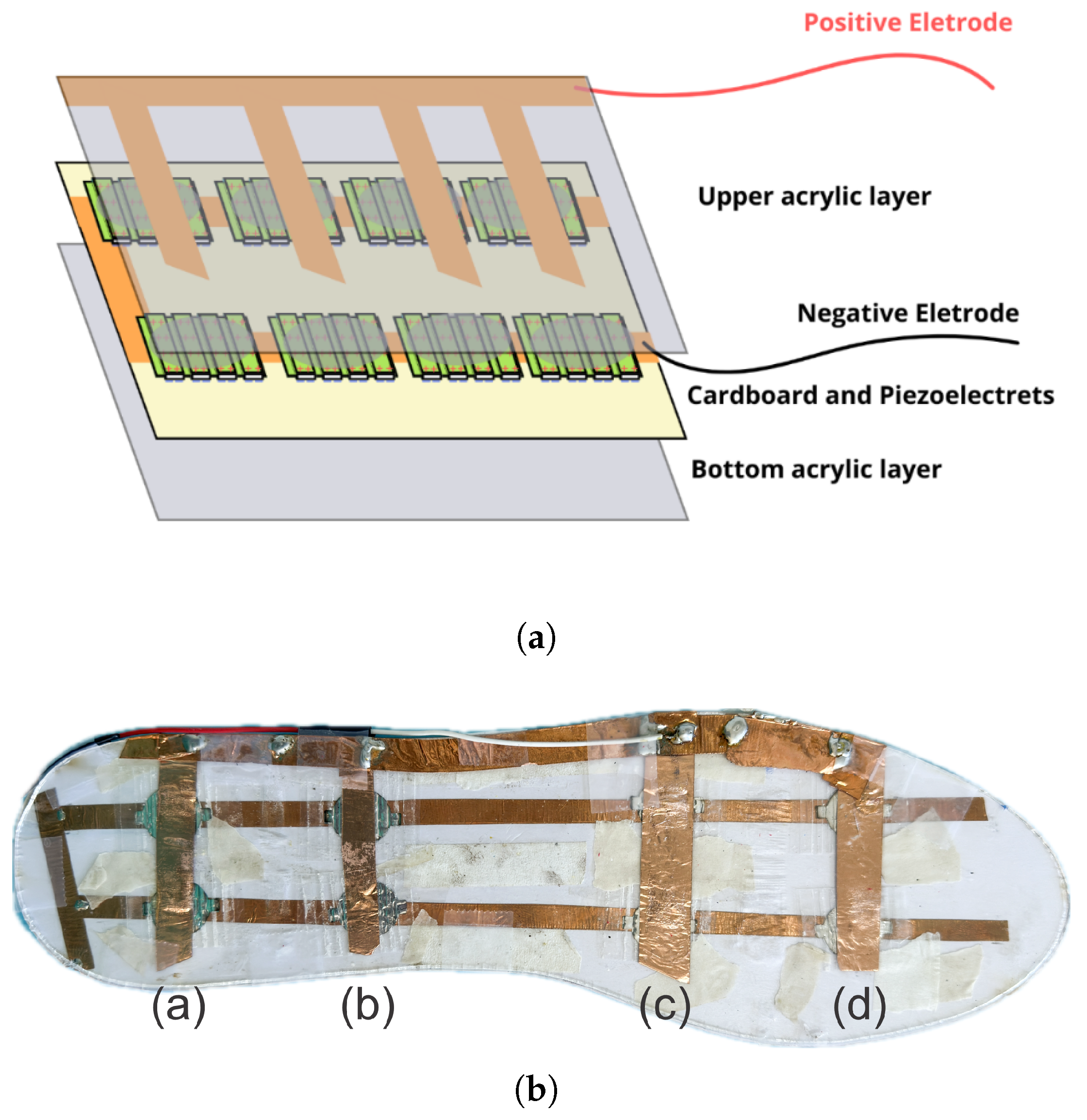

Sensor Placement: Piezoelectret sensors are strategically positioned in high-pressure regions such as the heel and forefoot to enhance energy conversion efficiency.

Testing Methodology: A mechanical test rig capable of replicating human gait was developed to validate the performance of the device under repeatable and controlled laboratory conditions, as well as to avoid ethical issues related to human experimentation.

Experimental Results:

- –

The prototype generated voltage pulses exceeding 13 V under limited force (~10 kgf).

- –

Average rectified DC output of approximately 3 V using a Delon circuit.

- –

A parallel arrangement of eight piezoelectret elements improved signal consistency and enhanced overall energy capture.

Theoretical Model:

- –

A simplified model was developed to estimate the output voltage based on electret parameters, applied force, and the number of sensors.

- –

The model aligns with experimental findings and serves as a predictive tool for future system scaling.

Applications:

- –

Potential integration into smart footwear platforms.

- –

Enables future energy autonomy for low-power electronics such as fitness trackers, health monitors, and GPS modules.

Advantages:

- –

Straightforward fabrication process.

- –

Use of readily available, low-cost materials.

- –

Compatibility with various wearable platforms.

- –

Aligned with sustainable electronics and energy harvesting trends.

Paper Structure:

- –

Section 2: Materials and methods—sensor fabrication, insole integration, test bench setup, and signal rectification circuitry.

- –

Section 3: Experimental results—signal response under dynamic load, energy estimation, and model validation.

- –

Section 4: Conclusion—summary of findings and their technological relevance.

- –

Section 5: Future work—scaling strategies, inclusion of energy storage (e.g., supercapacitors), DC-DC converters, and integration of communication or signaling modules.

3. Results

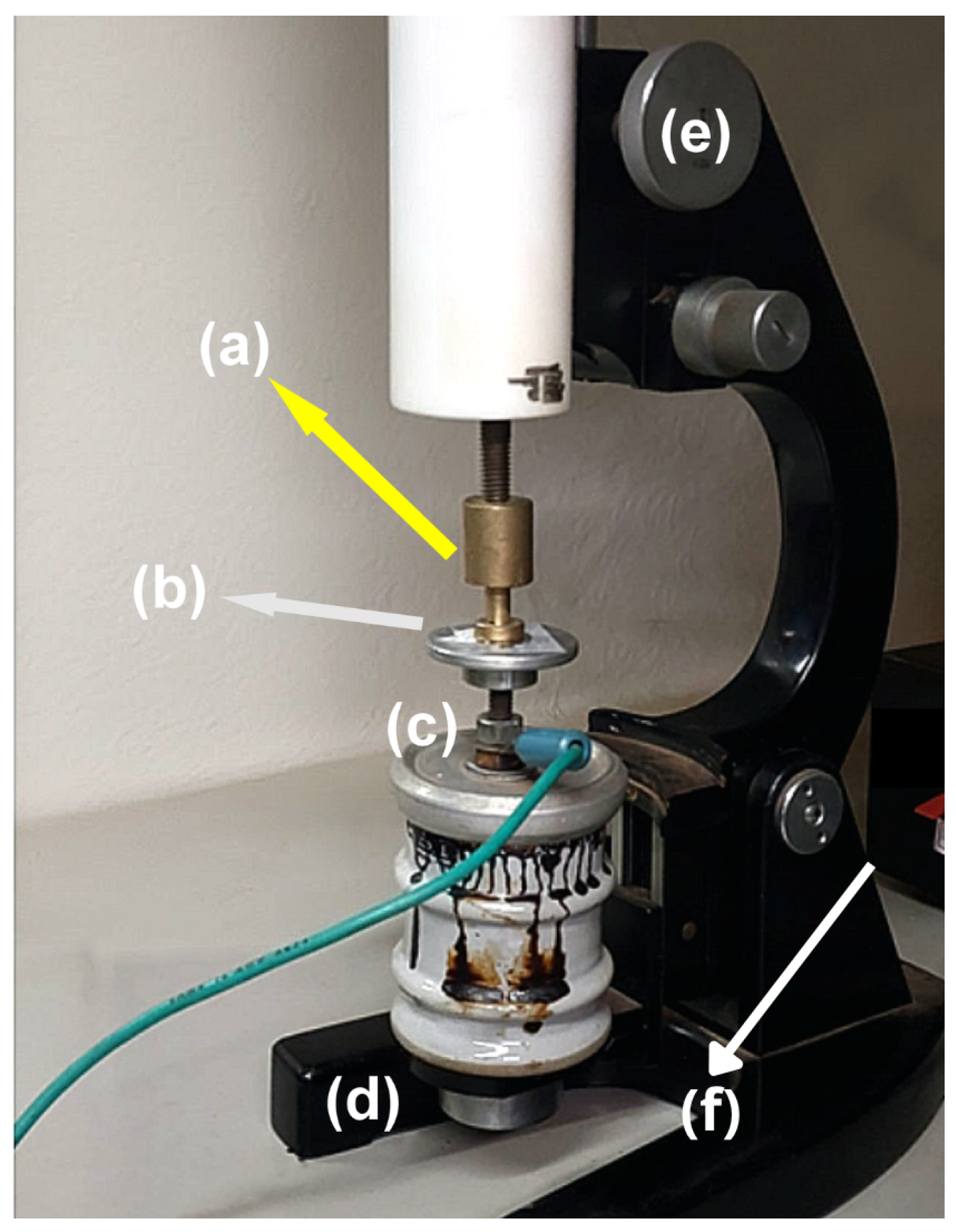

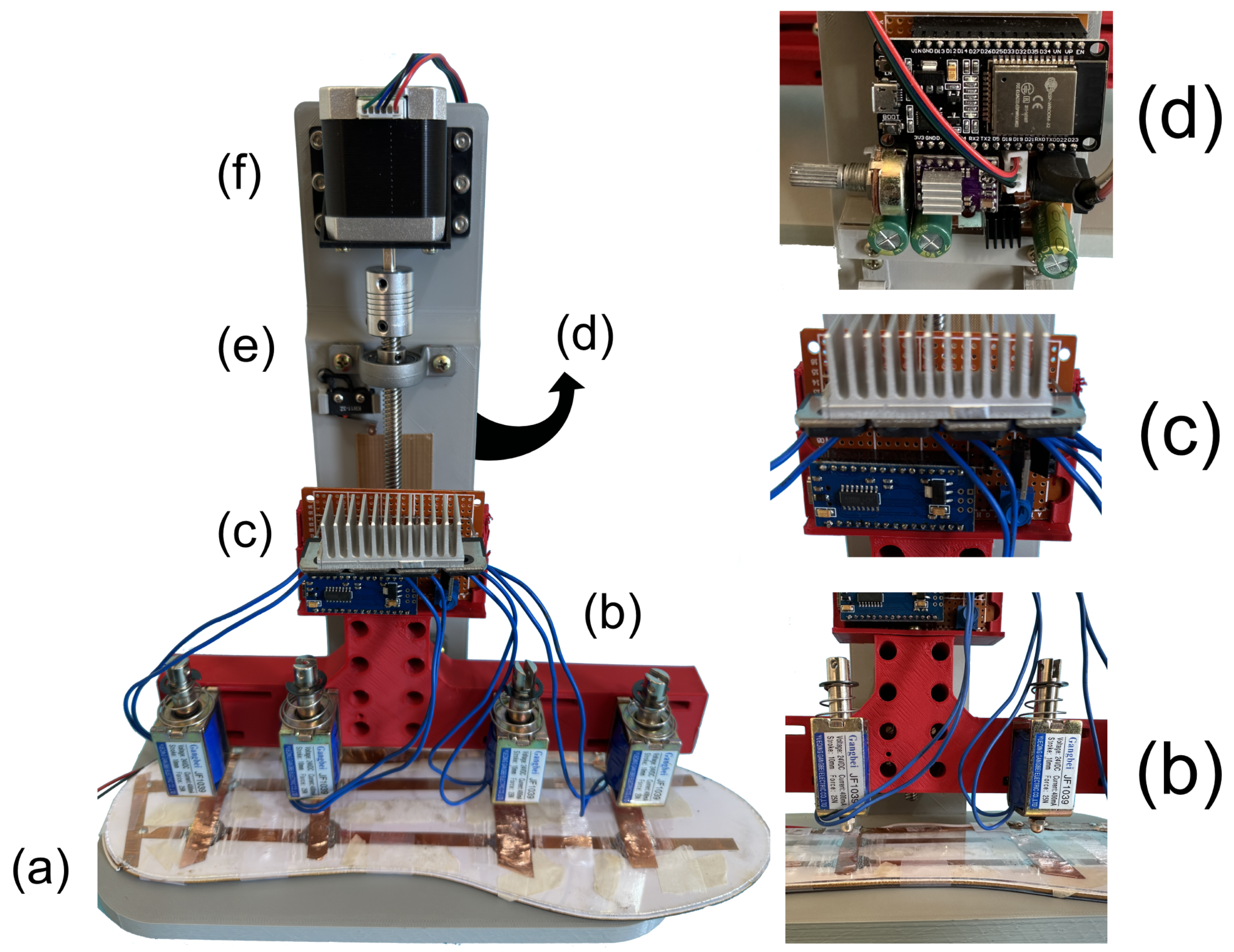

This section presents the experimental results obtained from the piezoelectret-based energy harvesting system and discusses their implications in terms of signal consistency, energy conversion, and theoretical validation. The performance of the insole was analyzed under dynamic loading using the test rig described in the previous section. The electrical outputs generated by the sensors were examined in both time and frequency domains, and key metrics such as peak voltage, pulse duration, and average DC output were measured. These results are further interpreted through a simplified theoretical model that establishes a linear relationship between the applied force and the generated voltage. Using the test rig as a controlled stepping analog allowed the experiments to be highly consistent, precise, and repeatable. Each solenoid piston applied a force of 25 Newtons (N) to the insole surface. To relate this to human step dynamics, the applied force must be converted into kilogram-force (kgf), a more intuitive unit for representing body weight distribution.

Thus, the equivalent force produced by each piston in kgf can be calculated using the following equation.

This force value closely resembles the pressure applied by a partial footstep, making the test conditions suitable for simulating realistic gait-related impacts. The test rig employs four pistons, which produce a combined total of approximately 10 kgf. In comparison, a 70 kg person walking usually exerts about 70 kgf per step, equivalent to their body weight. When running, as previously mentioned, the same person can generate between 2.3 and 3 times more force, resulting in an impact force ranging from 173 kgf to 214 kgf per step. Therefore, the total force applied by the pistons in this setup represents only a fraction of the mechanical energy that the electrets would be exposed to under real human motion. Despite the reduced input, the electrets were still able to generate measurable electrical signals.

3.1. Electrical Output and Signal Analysis

The electrical response of the insole under dynamic mechanical excitation was evaluated using the solenoid-based test rig operating at a frequency of four steps per second, which corresponds to a simulated running speed of approximately 20 km/h, assuming an average stride length of 1.4 m. Each actuation event applied a compressive force to the piezoelectret sensor zones, resulting in distinct voltage pulses characterized by sharp rise and fall transitions, consistent with the dynamic nature of heel–toe contact. To assess signal integrity and reliability over time, extended testing was performed for a total duration of 25 min, during which periodic waveform samples were recorded.

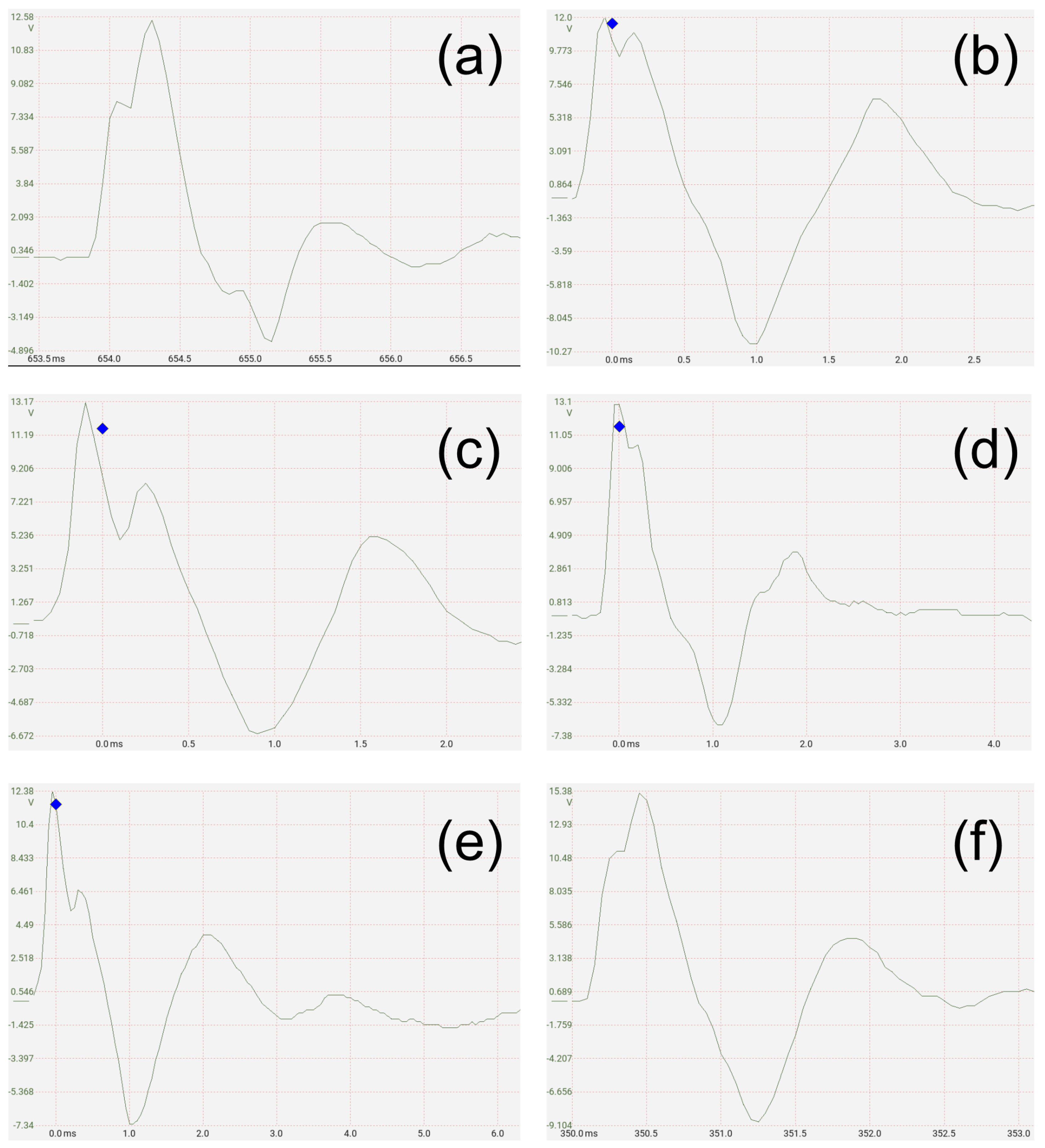

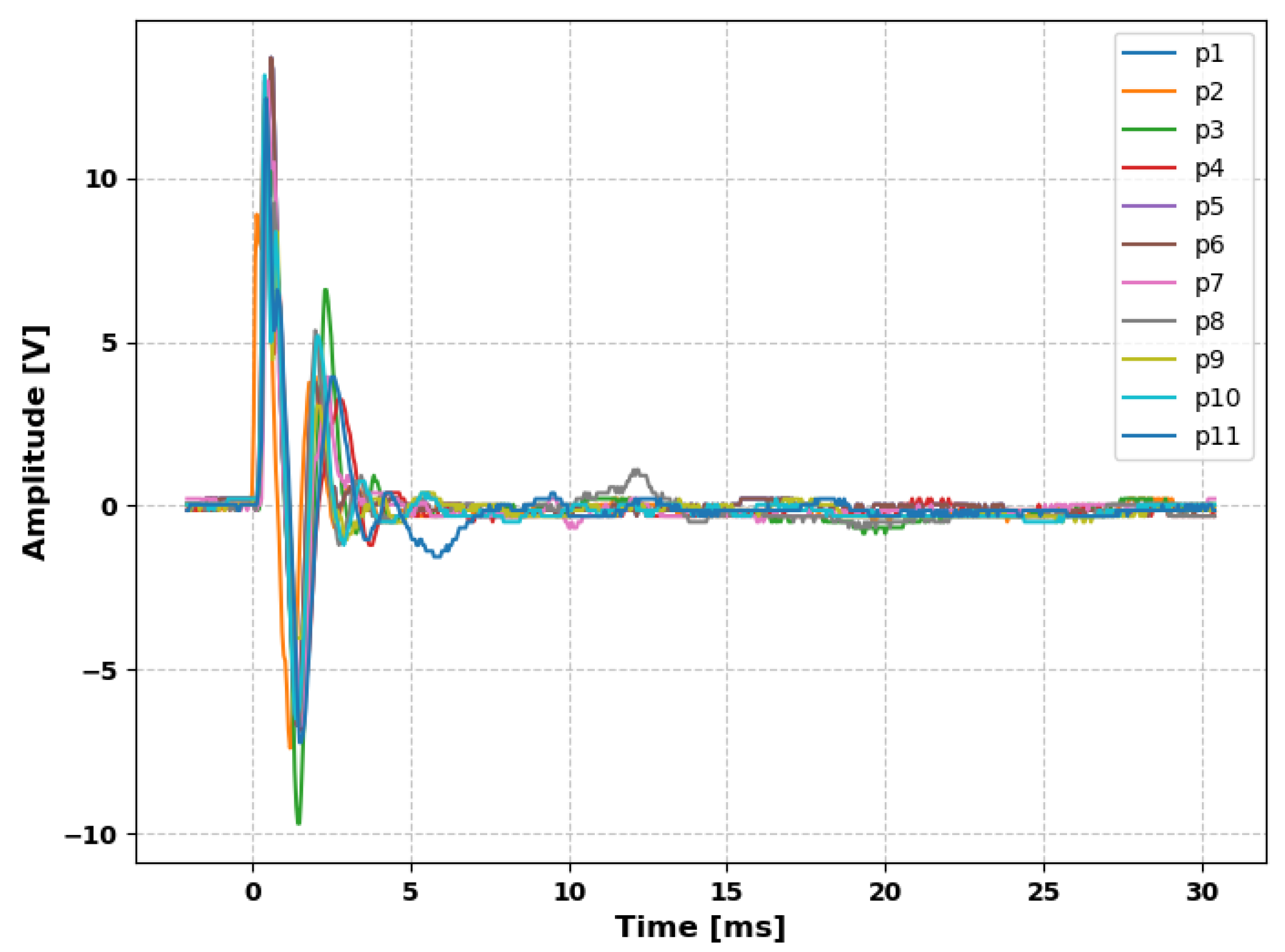

Figure 16 shows the electrical response of a single pulse.

Figure 17 presents a detailed view of the typical voltage waveform generated by a single piezoelectret module subjected to a compressive force of 25 N. The pulse exhibits a sharp rising edge followed by a damped oscillatory decay, reaching a peak amplitude of approximately 13 V. The total pulse duration is around 6 milliseconds, corresponding to the transient mechanical compression imposed by the solenoid actuator. This waveform illustrates the fast electromechanical response of the piezoelectret structure and confirms its ability to transduce rapid dynamic loads into measurable electrical signals with high sensitivity and temporal resolution.

In order to extend the electromechanical characterization of the piezoelectret response, additional performance metrics were estimated from the measured voltage waveform and the capacitor-based model of the sensor. The instantaneous charge

Q transferred during a compression cycle can be expressed as follows:

where

C is the effective capacitance of the piezoelectret element and

is the peak voltage variation during the pulse. Normalizing this charge by the active electrode area

A, the surface charge density

is obtained as follows:

which provides an indicator of the trapped charge effectiveness in the electret structure.

The corresponding peak current

is given by the derivative of the voltage across the capacitor as folows:

Its normalized value yields the current density

J as follows:

The harvested energy per compression event can be approximated by the stored energy in the equivalent capacitor as follows:

Finally, dividing this energy by the active volume

of the sensor leads to the energy density

:

These metrics charge density, current density, and energy density provide a more complete description of the electromechanical conversion process and enable fair comparison with other energy harvesters reported in the literature.

Quantitative Metrics from the Typical Pulse

From the representative waveform in

Figure 15, the following measurable quantities can be extracted with oscilloscope cursors: (i) peak amplitude

, (ii) pulse width

(e.g., full width at half maximum, FWHM), (iii) rise time

(10–90%), (iv) fall time

, (v) inter-pulse period

T (or step frequency

), and (vi) ring-down frequency

and decay envelope (for damping/quality factor).

A conservative RMS estimate of a narrow pulse train can be obtained under a rectangular approximation:

which provides a lower-bound normalization for comparison across operating conditions.

Given the equivalent capacitive model of the piezoelectret element, additional electrical figures of merit can be derived once the effective capacitance C and active electrode area A are known/estimated:

Transferred charge per pulse

where

is the pulse excursion (typically

for an open-circuit snapshot).

Surface charge density

Peak current and current density

In practice,

can be estimated from the 10–90% rise segment as

Energy per compression event and energy density

where

is the active volume of the transduction region.

Average power (per channel) at repetition rate

fTogether, these directly measurable (or single-parameter-derived) metrics—, , , , f, , Q, , , E, , and provide a compact yet comprehensive description of the electromechanical response and enable comparison with prior energy harvesters.

Figure 17 presents representative oscilloscope traces acquired at six time intervals: (a) initial time (0 min), (b) 5 min, (c) 10 min, (d) 15 min, (e) 20 min, and (f) 25 min. The results demonstrate a stable signal profile with negligible degradation in voltage amplitude, waveform shape, or response time, indicating that the electrodes retained their ability to convert mechanical impact into electrical output throughout the entire test duration. This confirms the electromechanical reliability and repeatability of the insole system under sustained dynamic loading conditions.

The waveform features a rapid rise time, indicating an immediate electromechanical response, followed by a symmetrical decay. The positive part of the pulse is due to the approximation of the parallel films of the tubular channels and the symmetrical decay is the reverse polarization due to the return of the original state of the films after the force is released. The signal is highly repeatable, as confirmed by the persistence mode on the oscilloscope, which overlays multiple cycles without significant deviation. This repeatability is crucial for practical energy harvesting systems, as it ensures a stable power supply and facilitates modeling. Furthermore, the well-defined pulse shape enables precise estimation of instantaneous power and energy per cycle.

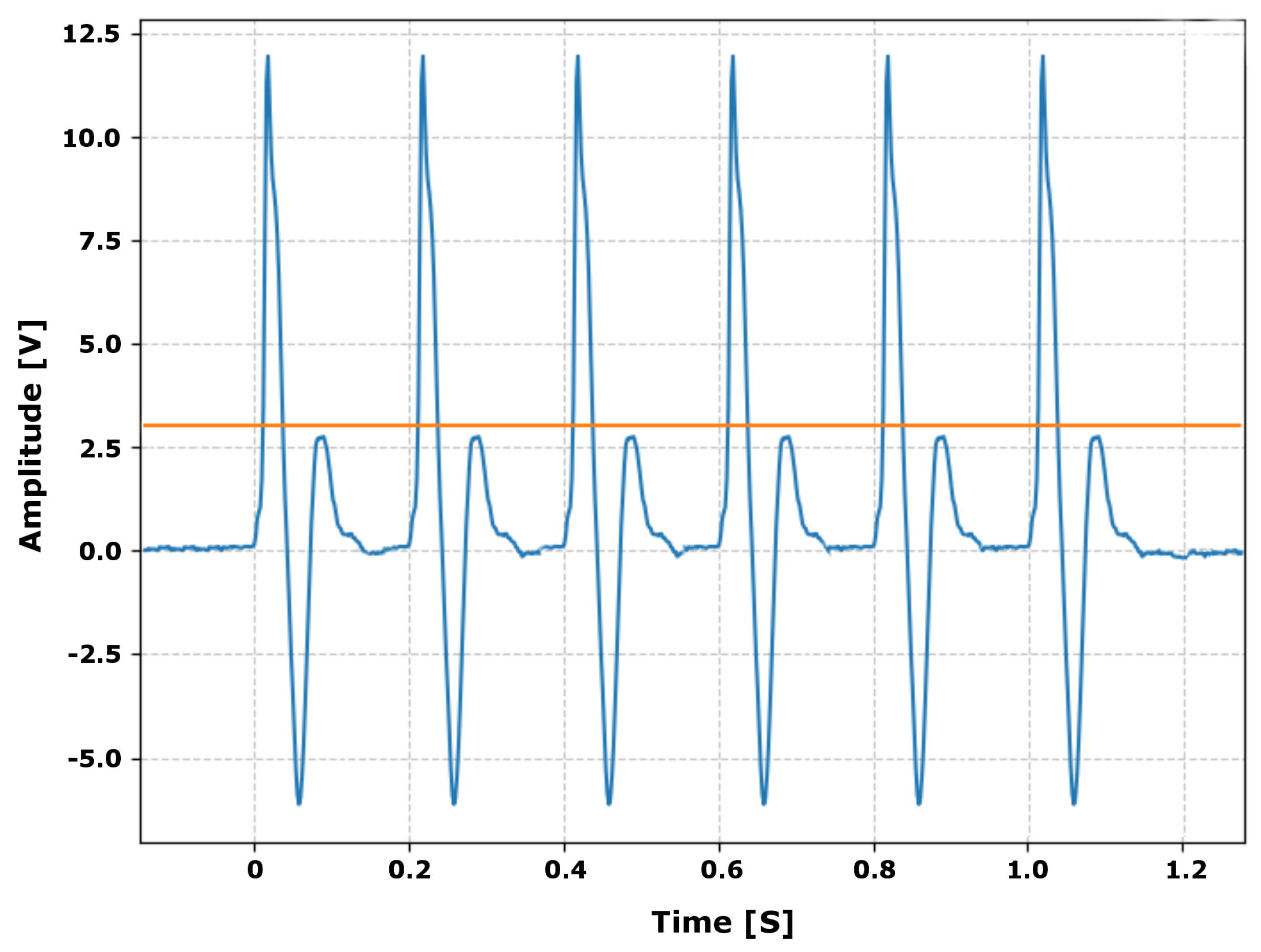

Figure 18 shows a sequence of pulses recorded over a 1 s interval, highlighting the periodicity and consistency of the output when subjected to cyclic loading conditions.

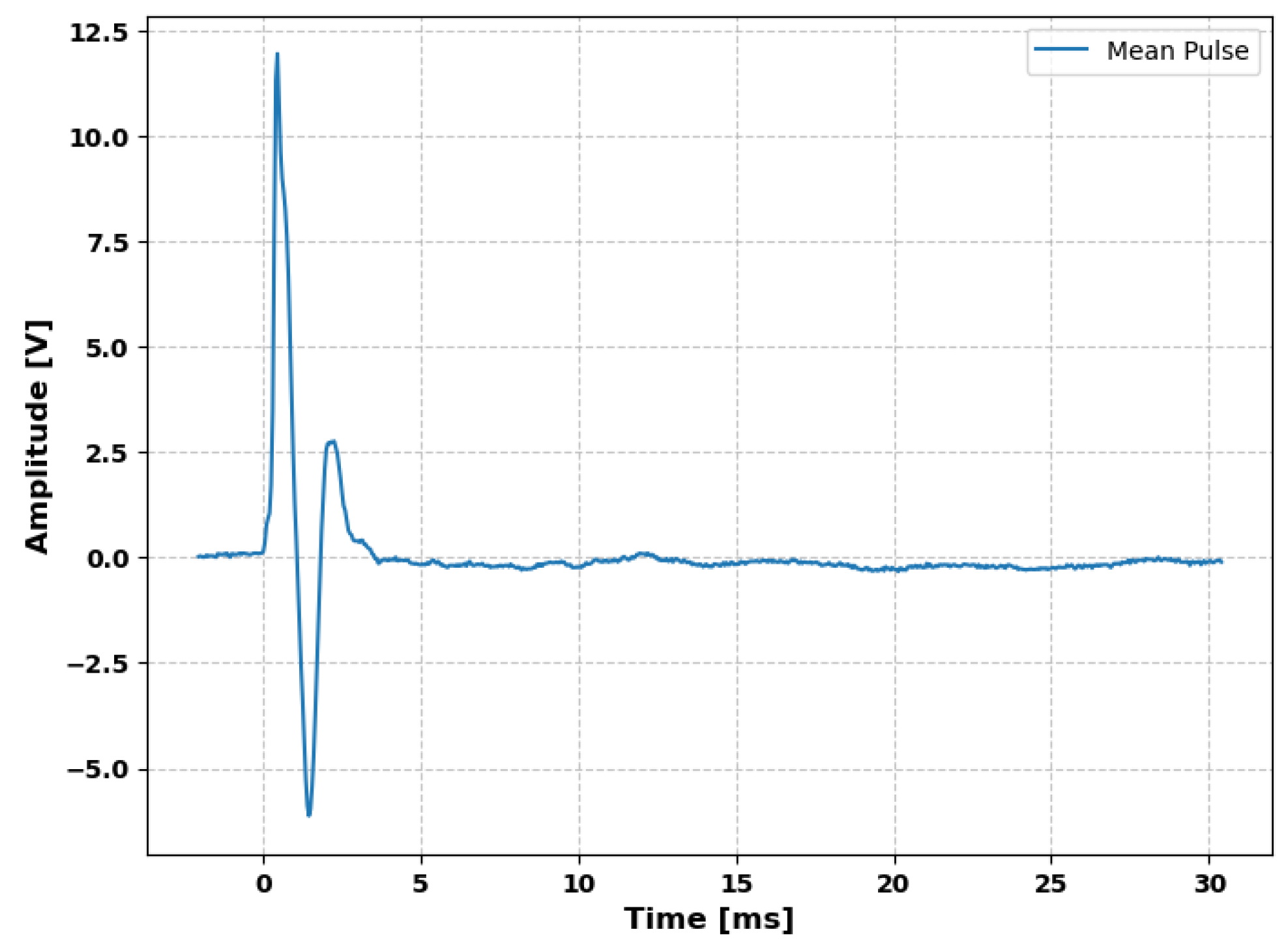

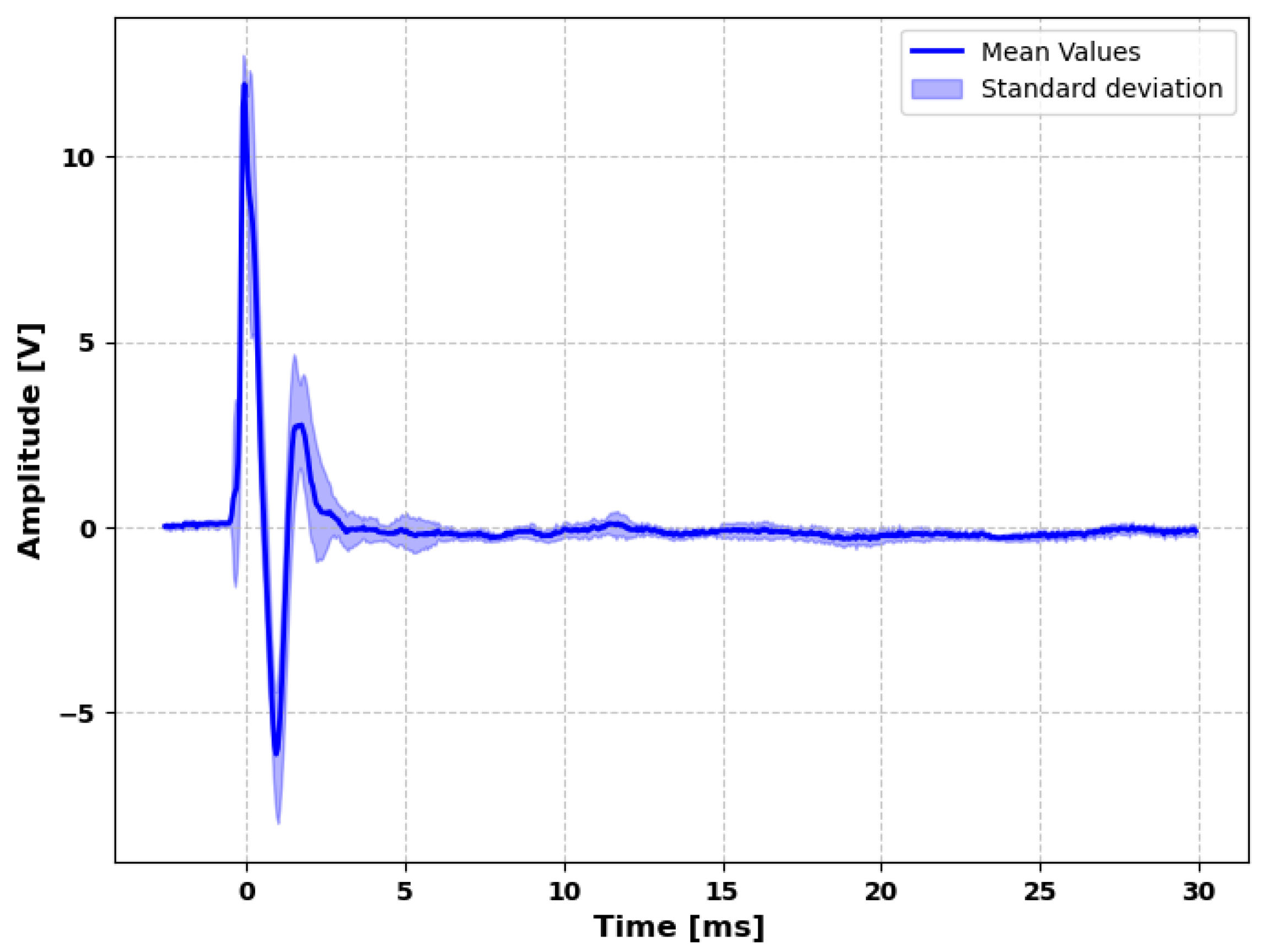

In order to reassure the repeatability of the generated pulses of the piezoelectret insole, the mean and standard deviation values for all pulses was calculated and is shown in

Figure 19.

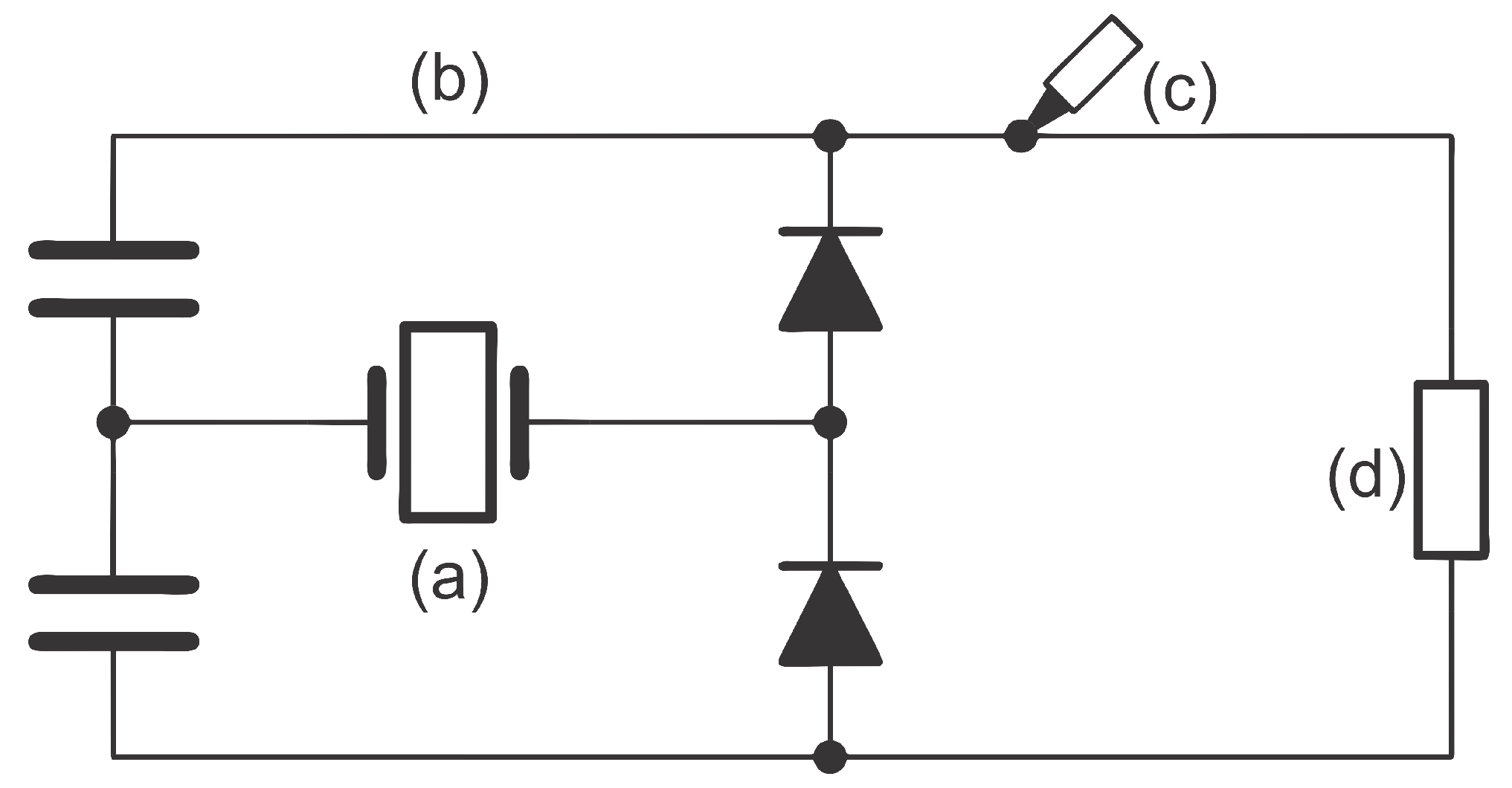

3.2. Harvested Energy Estimation

The time-domain behavior of the piezoelectret system was evaluated to assess its performance under different frequencies simulating walking and running.

At a frequency increased to 5 steps per second, corresponding to a simulated speed of approximately 22 km/h, the generated signal exhibited consistent timing between pulses, with uniform peak intervals and no delay-induced degradation.

The reliability of pulse timing is critical in applications where energy storage or power management circuits depend on predictable input behavior. This consistency also facilitates synchronization with other wearable system modules.

To properly quantify the level of energy harvested during the tests, the AC pulses generated by the piezoelectrets must be converted into an equivalent DC voltage. This can be estimated using the RMS value of the pulse signal which measures the equivalent of the average power of an AC signal [

46]. The RMS value

is determined by the following:

where:

: is the RMS output voltage;

is the time-varying pulse signal;

T: is the period of the signal (30 ms).

By applying this method to the mean value of the measured pulses, an RMS voltage of approximately 3 V was obtained. This value represents the effective energy contribution of each dynamic event over time, converting the alternating electrical behavior of the piezoelectret into a steady-state DC equivalent suitable for energy storage or powering low-power electronic devices.

Figure 20 illustrates this relationship, showing the repetition of representative AC voltage pulses generated at 5 steps per second (blue waveform), overlaid with a constant orange line representing the calculated RMS voltage. This RMS line reflects the equivalent DC value that would deliver the same amount of energy over time, allowing a direct comparison between transient piezoelectric signals and their potential in real-world energy harvesting applications.

In addition to voltage analysis, the system’s average current output under a 10 kΩ resistive load was estimated to assess its energy delivery capacity. Given the DC-equivalent voltage

V of approximately 3 V, the resulting current

I is as follows:

This corresponds to an average power output of the following:

This power output is a result of the individual contribution of the eight piezoelectrets, yielding an effective contribution of 112.2 µW per sensor. While modest, this power level is compatible with intermittent operation of ultra-low-power systems such as signaling LEDs or Bluetooth Low Energy (BLE) modules. These results confirm the practical viability of the energy harvesting strategy for powering discrete embedded devices in wearable electronics.

To provide a normalized perspective of the harvester’s performance, the measured average power of 900 µW was divided by the active sensor area of

(eight sensors of

each). This yields a power density of approximately the following:

Similarly, the average current of 300 µA results in a current density of the following:

These normalized figures allow a direct comparison with state-of-the-art piezoelectric and triboelectric energy harvesters, and confirm that the proposed insole operates within the expected range for polymer-based devices.

3.3. Theoretical Modeling of the Energy Harvesting Mechanism

To provide analytical insight into the behavior of the piezoelectret-based energy harvesting system, a simplified physical model is proposed. Each electret unit is approximated as a parallel-plate capacitor, in which the electrodes are separated by a distance

d, and the electric field is generated by permanently trapped charges on the internal surfaces. As seen in

Figure 21.

Assuming a uniform surface charge density

and dielectric permittivity

, the electric field E between the plates is given by the following:

When the structure is mechanically compressed, the distance between the plates decreases by a small amount

. Under the assumption that the internal electric field remains approximately constant during this small deformation, the resulting change in voltage

across the electret can be approximated by the following:

The displacement

is related to the applied force

F through Hooke’s Law, assuming linear elastic behavior, is as follows:

where

A is the electrode area and

Y is the Young’s modulus of the dielectric material. Substituting into Equation (

8), we obtain the following:

This expression shows that the generated voltage is linearly proportional to the applied force. For an array of X identical electrets connected in parallel, the overall voltage output remains the same, but the current capacity increases. However, for modeling purposes, we define a practical proportionality constant for the insole configuration:

This constant can be calculated based on the experimental data. For example, considering a measured voltage of 260 mV from eight sensors under a total force of 25 N, we obtain the following:

This result suggests that, on average, each Newton of applied force generates approximately 15 mV per electret module, which aligns well with the experimental voltage pulses observed in

Section 3.3. The model, despite simplifications, provides a useful predictive tool for system scaling and optimization in future designs.

It is important to note that the present setup applied approximately 25 N per piston, corresponding to localized loading of each insole zone. This choice ensured that the piezoelectret films operated within the small-strain elastic regime, avoiding nonlinear or saturation effects while still producing measurable and repeatable signals. Since the voltage output scales linearly with the applied force under these conditions, the measured response can be extrapolated to realistic ground-reaction forces of 700–1000 N observed during human gait. In this scenario, the load is distributed among multiple zones of the foot, and the harvested energy per step increases quadratically with force:

Thus, the experimental operating point at 25 N per piston provides a valid basis for scaling toward real-use conditions while maintaining linearity and material integrity.

3.4. Piezoelectret Insole Benchmark

In order to evaluate the response of the piezoelectret insole,

Table 1 shows a comparative between the results of the piezoelectret insole compared to other energy harvesting systems.

The piezoelectret insole demonstrates a feasible and scalable approach to biomechanical energy harvesting, achieving notable voltage outputs from a low-cost, flexible platform. Under a controlled, limited-force load of approximately 10 kgf, the system consistently generated voltage peaks up to 13 V, with an estimated average power output of 900 µW. The key achievement of this work is the validation of a simple and scalable fabrication process using thermoformed Teflon films, positioning the technology as a practical solution for integration into smart footwear. When benchmarked against other energy harvesting technologies, the performance of the piezoelectret insole is best understood by the application and transduction method. Its power output is modest when compared to other footstep-based harvesters; for example, mechanical systems using fluid-flow have reported significantly higher average power, reaching up to 1.4 W per step. This highlights that while piezoelectrets offer simplicity, other mechanical methods can capture a larger fraction of the available energy. In the realm of advanced materials, triboelectric nanogenerators (TENGs) show exceptionally high peak power density (4.9 W/m2), indicating superior efficiency per unit area. Similarly, devices designed for discrete, high-force events, like a piezoelectric press-button harvester, can produce much higher instantaneous power (20 mW per impact). In the broader context of vibration energy harvesting, the insole’s output is lower than that of systems targeting more consistent or powerful sources. Hybrid systems for wind energy can generate over 46 mW, and devices tuned for specific resonant machine vibrations can yield 9.1 mW. However, the insole’s power generation is substantially greater than that of miniaturized MEMS-based harvesters, which operate in the microwatt and nanowatt range. In conclusion, while the insole’s 900 µW output is not the highest, its primary advantages are its low cost, simplicity, and scalability. This positions it as a practical solution for powering low-consumption wearable electronics, such as simple sensors or BLE modules, rather than as a high-power source.

To advance this technology toward real-world use, future efforts will focus on resolving key challenges in scalability and environmental resilience. For scalability, the straightforward thermoforming process is highly amenable to automated manufacturing techniques, where precise control over temperature and pressure can ensure high manufacturing uniformity across all sensors, leading to predictable and reliable energy output in a full-coverage insole. Regarding long-term durability, the inherent mechanical resilience of the FEP and PTFE films is a significant advantage, and this can be further enhanced with advanced encapsulation methods that protect the internal structures from material fatigue. According to the manufacturer, the FEP film is durable for at least 10,000 cycles to a maximum 31 MPa stress [

47]. To ensure stable performance against environmental factors like humidity or sweat, the current multi-layer design already offers physical protection. This protection can be augmented with hermetic sealing or hydrophobic coatings to prevent moisture ingress, thereby preserving the stable charge retention and ensuring the integrity of the output signals. By addressing these factors, the system’s robustness can be fully realized for commercial smart footwear applications.

It should be noted that the present validation was performed exclusively under controlled conditions using a mechanical gait simulator. While this approach ensured repeatability and isolation of electrical performance, it does not fully replicate the variability of human gait. Therefore, real-time insole application testing with human participants will be a necessary step to validate durability, comfort, and energy yield under realistic biomechanical conditions.

4. Conclusions

The results presented in this work confirm that the proposed methodology for integrating piezoelectret-based energy harvesting systems into footwear is both functional and highly scalable. The custom insole, equipped with eight piezoelectret sensors positioned at high-impact regions (heel and forefoot), successfully converted simulated step loads into measurable electrical energy, validating the viability of the system.

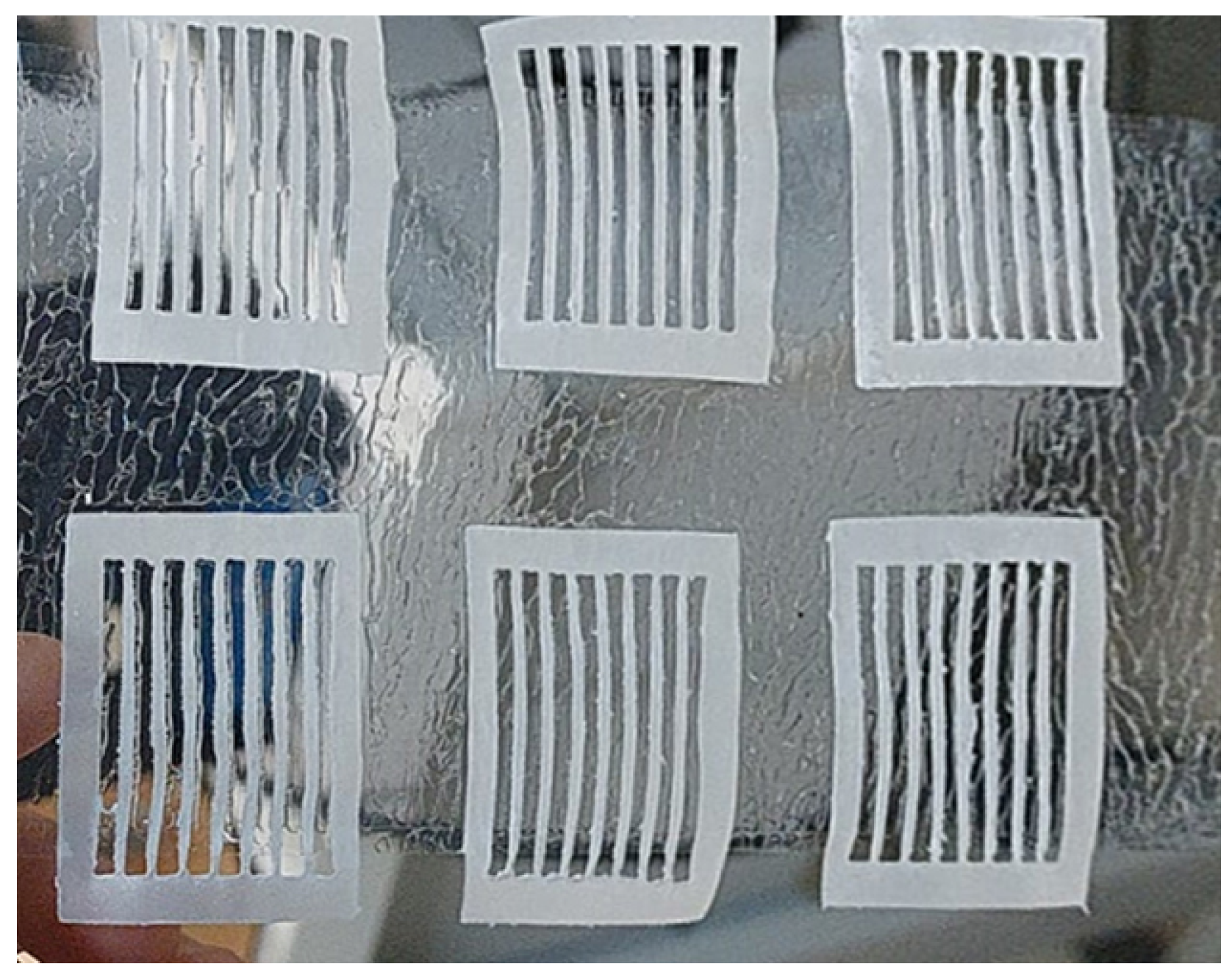

Controlled testing using a solenoid-driven rig enabled consistent evaluation of electrical output under repeatable gait conditions. The sensors produced voltage pulses ranging from 5 V to over 13 V under low-force scenarios (10 kgf), with pulse durations above 1 ms. These levels are sufficient to activate low-power electronic circuits. The entire system was fabricated using cost-effective methods including laser-cut FEP/PTFE layers, thermal lamination, and aluminum sputtering making it suitable for large-scale and low-cost production.

The mean value of all collected pulses was used in order to evaluate the capability of the sensor to transduce force into energy. The calculated RMS output of the generated pulse was approximately 3 V and the estimated power was 900 µW. In a real-life environment, a human walk would lead to greater forces applied to the insole and, therefore, a greater generated energy. The resulting voltage could be sufficient to power low-energy embedded systems embedded in footwear. Such systems may include fitness trackers, GPS modules, step counters, or other wearable electronics, enabling self-powered smart shoes for health monitoring, sports performance, or personal safety applications [

48,

49,

50].

From a scalability perspective, the current design utilizes only a portion of the available insole area. Even so, it produced usable energy levels, suggesting that a full-coverage configuration could significantly increase energy yield per step. This opens the door to powering embedded systems such as GPS modules, fitness trackers, health monitors, or wireless communication devices within a self-powered smart shoe. The potential applications of this technology extend beyond footwear. The concept of harvesting mechanical energy from motion is applicable to prosthetics, industrial vibration sensing, biomedical monitoring, and other wearable systems that benefit from autonomous power sources. In conclusion, the proposed system is technically robust, economically viable, and easily replicable. Its simplicity, low cost, and adaptability position it as a compelling solution for sustainable energy harvesting in the next generation of intelligent wearable electronics.

5. Future Work

Future developments of this research aim to expand the active surface area of the piezoelectret elements to enhance energy harvesting efficiency under gait-induced mechanical loading. Increasing the physical dimensions of the electret layers or employing a larger number of sensors is expected to significantly boost charge displacement and improve voltage generation under realistic plantar pressure profiles. In addition, optimization of fabrication parameters, such as thermal pressing conditions and electrode geometry, may further enhance device performance. From a system integration perspective, a custom low-input-voltage boost converter is currently under design, together with fast-charging supercapacitors that will serve as energy buffers, enabling stable output to power ultra-low-power devices such as indicator LEDs, Bluetooth Low Energy (BLE) beacons, or GPS trackers. Together, these improvements are expected to transform the current prototype into a fully autonomous and robust energy-harvesting platform.

Beyond these aspects, future work will also address experimental durability tests, extending up to several hundred thousand gait cycles, to quantify long-term stability and fatigue resistance of the piezoelectret films under repetitive stress. Additional figures of merit, such as experimentally measured energy density and surface charge density, will be incorporated to enable rigorous benchmarking against state-of-the-art harvesters. Importantly, in vivo testing with human participants will be carried out under different gait conditions (walking, running, stair climbing) to validate electrical performance under realistic biomechanical variability. Finally, ergonomic evaluations of thickness, flexibility, and comfort will be performed to ensure the suitability of the insole for prolonged daily use, consolidating its potential for next-generation smart footwear and wearable energy harvesting applications.

In addition to the electrical and mechanical optimizations proposed, future investigations will also consider long-term reliability aspects such as humidity resistance, sweat exposure, and mechanical fatigue. Predictive maintenance strategies, including in-field monitoring and anomaly detection algorithms [

51], may be integrated in later stages to improve robustness and mitigate functional degradation in practical wearable applications.