1. Introduction

With the continuous advancement of unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) technology, collaborative multi-UAV systems have shown significant potential in applications such as intelligent inspection, disaster response, and smart cities. Meanwhile, semantic communication has emerged as an efficient paradigm by transmitting key semantic features, reducing redundancy, and improving communication efficiency.

However, in multi-UAV-assisted semantic communication networks, ground devices often operate in highly dynamic environments with uncertain and time-varying positional distributions and channel states. This challenges the real-time performance and robustness of computation offloading and resource allocation strategies. UAVs must dynamically optimize transmission power, task offloading ratios, and data compression to adapt to device mobility while ensuring communication quality and minimizing energy consumption, achieving joint optimization of computational and communication resources.

Computation offloading and resource allocation are mutually coupled and closely interrelated critical issues. Existing research has made significant progress in the field of multi-UAV collaborative computation offloading and resource allocation. A UAV-enabled secure edge computing platform was investigated in [

1], achieving the objective of maximizing the transmission rate by jointly optimizing the UAV trajectory, power, and offloading ratio. A UAV-assisted edge computing system with energy harvesting capabilities was published in [

2] that realized minimization of energy consumption and maximization of UAV energy storage. A UAV-assisted vehicular edge computing architecture that optimizes task offloading was proposed in [

3], maximizing the weighted sum of offloading utility for all vehicles. A UAV-based mobile edge computing system aiming to minimize UAV energy consumption by optimizing offloading decisions, UAV hovering time, and available computational resources was investigated in [

4]. A joint optimization algorithm in a UAV-supported edge computing system was designed in [

5], and it was based on particle swarm optimization and double deep Q-network to minimize UAV energy consumption. A UAV-assisted edge computing scenario was examined in [

6], focusing on task offloading between IoT mobile devices and UAVs and minimizing total system energy consumption by jointly optimizing offloading decisions and UAV trajectory. A dynamic resource management in a multiple-access mobile edge computing-assisted railway IoT network was explored in [

7], jointly optimizing subcarrier allocation, offloading ratio, power allocation, and computational resource allocation to minimize a weighted sum of energy consumption and latency. A UAV-enabled mobile edge computing system under partial computation offloading was investigated in [

8], maximizing computational efficiency through the joint optimization of UAV offloading time, CPU frequency, user transmission power, and UAV flight trajectory.

In traditional UAV-assisted communication networks, computation offloading and resource allocation strategies typically focus on accurate bit-level transmission while neglecting the semantic meaning conveyed by information symbols, thus failing to meet task-driven and semantic-oriented communication requirements. To address this challenge, an increasing number of studies have begun to explore computation offloading and resource allocation mechanisms in semantic communication environments.

A resource allocation model based on semantic-aware networks was proposed in [

9], defining semantic spectral efficiency as a metric to evaluate communication efficiency. They then jointly optimized task offloading and the transmission volume of semantic symbols to maximize SSE. An adaptive semantic compression framework for end-to-end semantic transmission was designed in [

10], introducing a task success probability metric based on successful transmission probability and successful comprehension probability. An adaptive semantic resource allocation paradigm incorporating semantic-bit quantization was proposed in [

11], defining semantic communication quality of service based on semantic quantization efficiency and transmission latency. A dynamic multiplexing and co-scheduling scheme for semantic and URLLC traffic coexistence was introduced in [

12], optimizing channel allocation, power, scheduling, and network parameters to minimize semantic users’ average data reconstruction error.

A task offloading and power allocation problem for UAV swarms in the low-altitude economy was investigated in [

13]. However, they did not establish a complete and well-defined semantic communication system. The base station locations were fixed, and the optimization variables were limited to transmission power and offloading decisions. The semantic-driven computation offloading and resource allocation problem in a UAV swarm-assisted surveillance system was studied in [

14], but the UAVs in this work were deployed at fixed locations without computational capabilities, preventing active position adjustment or adaptive control over transmitted and computed data volume based on environmental conditions. Additionally, the study focused on video scenarios and lacked proper modeling for image transmission characteristics. A semantic-driven resource allocation in UAV-assisted semantic communication networks was explored in [

15]. However, this work did not consider UAV trajectory planning and ignored the impact of computational processes on system latency and energy overhead.

Seminal works on UAV-enabled semantic communication from [

13,

14,

15] have laid important groundwork by assuming static ground devices or pre-optimized, static UAV trajectories. However, like most existing studies, they fail to account for in-depth modeling and consideration of device mobility characteristics in dynamic environments. The random movement of ground devices leads to time-varying channel states and necessitates real-time adjustments to association and resource allocation. This oversight neglects the impact of positional and behavioral variations in dynamic scenarios, making it difficult for systems to adapt to the communication and computation requirements of complex real-time applications.

Recent studies on mobility-aware semantic communication are laying the groundwork for new directions in UAV semantic communications. A Mobility-aware Split-Federated with Transfer Learning (MSFTL) framework was proposed in [

16] to facilitate efficient and adaptive semantic communication model training in dynamic vehicular environments. A semantic-aware trajectory summarization technique was presented in [

17] to streamline the analysis of human mobility patterns. In the context of UAV semantic communications, there are several studies that consider mobile ground devices. A wildlife monitoring system was investigated in [

18], deploying sensors in the service area and employing UAVs to collect data for animal tracking. However, their work did not establish a comprehensive mobility model for the animal targets. The trajectory planning for UAV-assisted mobile users was studied in [

19], where user movement was modeled using a Gauss–Markov random process. They employed a double deep Q-network algorithm for trajectory optimization, achieving reward maximization under energy consumption and quality-of-service constraints. Additionally, considering the feasibility of the UAV learning framework, a feasible and generalizable multi-agent reinforcement learning framework is proposed in [

20] for wireless MAC protocols, which introduces a practical training procedure and leverages state abstraction to enhance its adaptability to diverse scenarios. While their work provides a detailed modeling of user mobility patterns, there remains room for improvement in terms of joint optimization strategies.

To address the aforementioned challenges, it is imperative to develop flexible dynamic computation offloading and resource allocation strategies for multi-UAV semantic communication networks. However, existing research exhibits two critical limitations: insufficient modeling of ground device mobility patterns and inadequate consideration of flexible computation–communication trade-offs through multi-UAV deployment.

This paper proposes a novel framework for dynamic computation offloading and resource allocation in multi-UAV semantic communication networks. By establishing comprehensive dynamic mobility models and developing joint optimization methodologies, we explicitly addresses the dynamic time-varying channel conditions induced by user mobility and aim to achieve efficient system performance balancing in complex environments. The main contributions of this work are shown below:

We construct a joint transmission–computation allocation model for dynamic devices in multi-UAV semantic communication networks. The model simultaneously optimizes UAV–device association, UAV trajectory, transmission power, task offloading ratio, and semantic compression depth to minimize the maximum task processing latency.

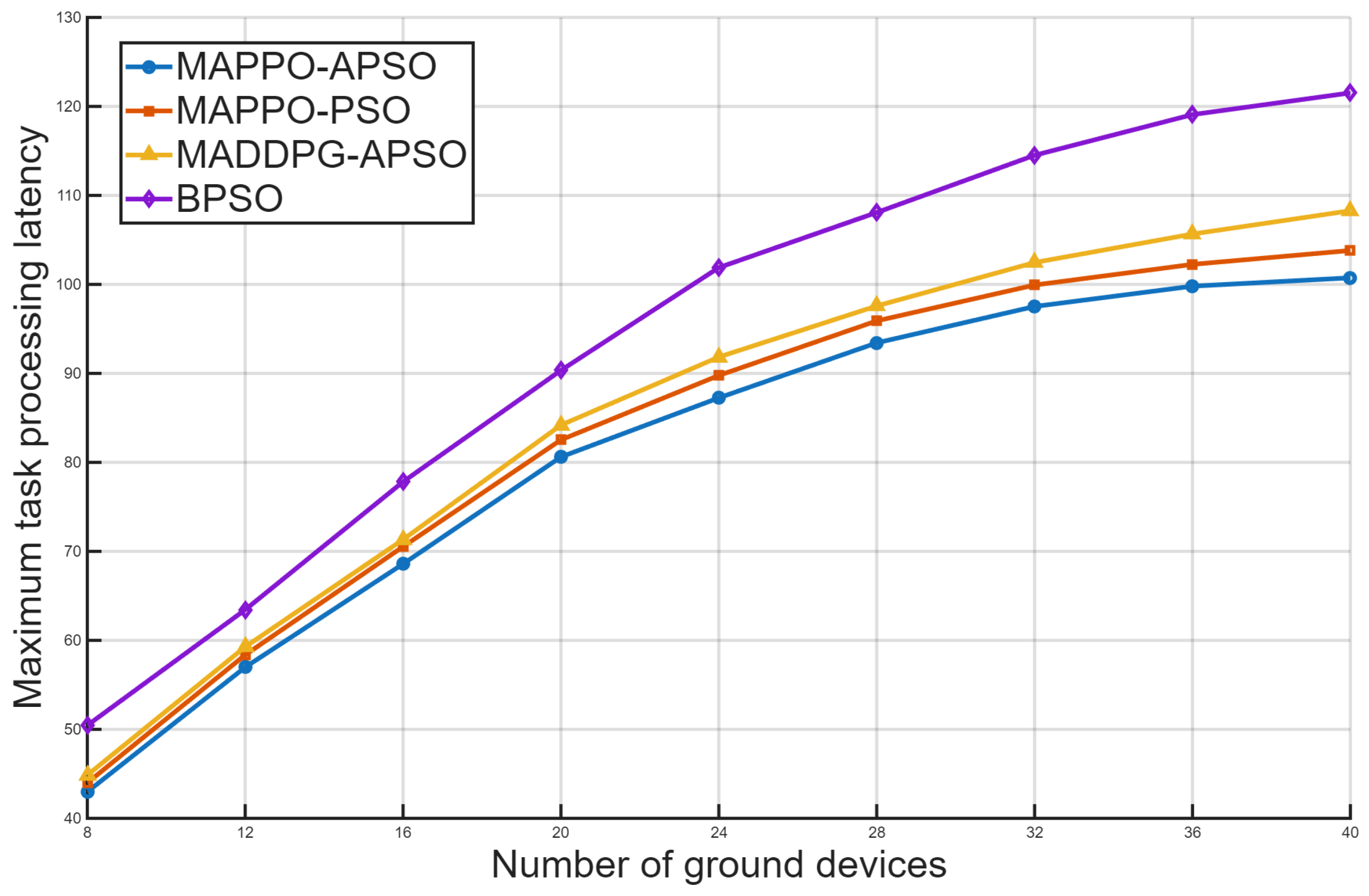

We decompose the UAV optimization problem into two subproblems and develop an alternating iterative optimization approach. This hybrid solution combines MAPPO with APSO algorithms to obtain near-optimal solutions.

Through comprehensive simulations, we demonstrate that the proposed algorithm significantly reduces both latency and energy consumption compared to existing schemes such as PSO and MADDPG.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows.

Section 2 introduces the system model.

Section 3 formulates the optimization problem.

Section 4 presents the proposed algorithm.

Section 5 provides simulation results, and the paper is concluded in

Section 6.

2. System Model

We consider a multi-UAV semantic communication network for image transmission and random device movement in an intelligent disaster rescue scenario, as shown in

Figure 1. The set

represents

I ground devices equipped with small computing units, and the set

represents

J UAVs maintaining a fixed altitude

H.

Assume that each device i collects several images containing environmental information, with a total of bits. Among them, a proportion of the images are semantically encoded and compressed to a depth of by device i and then transmitted to the associated UAV j where the images are semantically decoded and restored to their original form. Correspondingly, the remaining proportion of the images is directly transmitted to UAV j without any processing. The task offloading ratio satisfies , where indicates that all images from device i undergo semantic encoding with no direct transmission of the original images, and means that none of the images from device i are processed and that they are all directly transmitted. The value of is determined based on the configuration of the compressible convolutional module in the semantic communication system. The UAVs have no starting or ending positions and only need to complete the reception of all data within the flight time T.

Upon completing reception, UAVs perform semantic-based image recovery. Ground devices, affected by environmental interference, adjust their positions following a Gaussian–Markov mobility model. We assume LoS channels with interference exist between devices and UAVs. The UAVs are modeled as medium-sized platforms with sufficient embedded computing and storage resources that are capable of concurrent multi-task processing and temporary data retention. This assumption is justified by the reduced data volume of semantic communication and the manageable computational demands of semantic encoding for modern processors, allowing the study to focus on the joint optimization of offloading and resource allocation under user mobility.

2.1. The Mobility Model of Ground Devices

The study is carried out in a three-dimensional Cartesian coordinate system with all measurements in meters. The height of each ground device i is 0, and its horizontal position coordinates at a certain time are . To facilitate problem handling, a time descretization method can be adopted, dividing the system operation time T into N equal-length time slots, each with a duration of . Through this transformation, the horizontal position of ground device i in a specific time slot n can be represented as , where .

At

, the system has not yet entered the operation time, the ground devices are randomly distributed, and the position of device

i is defined as

. During the system operation time, the movement of each device

i follows a Gaussian–Markov random mobility model. In time slot

n, its speed

and direction

are calculated as

where

and

represent the speed of device

i in time slot

n and

, respectively, while

and

represent the direction of device

i in time slot

n and

, respectively. The parameters

denote the memory level, which adjusts the influence of the previous state.

represents the average speed, and all ground devices share the same average speed.

represents the average direction of device

i, and each ground device has a different average direction.

and

are two independent Gaussian distributions, following different mean–square pairs

and

.

Based on the formulas for speed

and direction

, the position of device

i in time slot

n is given as

2.2. Channel Model

All UAVs fly at a constant altitude

H, and the horizontal position of UAV

j in time slot

n is

. Each UAV maintains a constant speed within every time slot. The height of device

i is 0, and its horizontal position in time slot

n is

. Therefore, the distance between UAV

j and device

i in time slot

n is given by

Assuming that the communication channel between ground device

i and UAV

j is dominated by the Line of Sight (LoS) link, we adopt the free-space propagation model. The channel power gain can be expressed as

where

represents the channel power gain at a reference distance of 1 m.

Assume that within each time slot, a UAV can serve at most one device, and a device can be served by at most one UAV across all time slots. A set of UAV–device association variables

is introduced to represent the association between UAV

j and device

i in different time slots.

is a binary variable, where

indicates that device

i establishes a communication connection with UAV

j in the

n-th time slot, and

indicates that no connection is established. The variable

satisfies the following constraints:

Assume that all ground devices and UAVs in the region communicate using the same frequency band. There may be cases where multiple devices establish connections with different UAVs within the same time slot, leading to channel interference. The Signal to Interference plus Noise Ratio (SINR)

between UAV

j and device

i in time slot

n is given by

where

is the noise power at the receiving UAV,

represents the transmission power of device

i in time slot

n, and the term

in the denominator represents the channel interference caused by the transmissions of all other devices

in time slot

n. Therefore, the data transmission rate between UAV

j and device

i in time slot

n can be expressed as

where

B represents the channel bandwidth.

2.3. Latency Model

The latency model consists of four parts: semantic encoding latency, transmission latency, semantic decoding latency, and task processing latency.

2.3.1. Semantic Encoding Latency

For any device

i, define the computational load of the standard convolutional module when there is no direct transmission of the original image (only semantic transmission) as

and the computational load of the compressible convolutional module as

, where

is the computational load when

. Therefore, when the task offloading ratio is

, the total computational load for semantic encoding is

. Let

. For ground device

i, the semantic encoding latency model can be expressed as

where

is the computational capability of device

i.

2.3.2. Transmission Latency

Ground device

i needs to transmit both the encoded and compressed semantic data and the unprocessed original images to a UAV

j to complete the image transmission task. To ensure that UAV

j receives all the data required for the image transmission task from device

i, the following constraint must be satisfied

where

represents the minimum number of time slots required to complete the transmission, satisfying

. We define

as the amount of semantic data transmitted over the wireless channel after semantic encoding and compression with depth

for the original

-bit image. Additionally, for ground device

i, the transmission latency model can be expressed as

2.3.3. Semantic Decoding Latency

The semantic decoder has a structure similar to that of the semantic encoder, also consisting of two parts: a standard convolutional module and a compressible convolutional module. For any device

i, in the case where there is no direct transmission of the original image, we define the computational load of the compressible convolutional module for semantic decoding as

, where

is the computational load when

, and the computational load of the standard convolutional module for semantic decoding as

. Therefore, when the task offloading ratio is

, the total computational load for semantic decoding is

. Let

. For ground device

i, the semantic decoding latency model can be expressed as

where the computational capability of all UAVs is

.

2.3.4. Task Processing Latency

Ground devices are required to semantically encode and compress selected images, transmit both semantic and raw image data, and enable UAV-side semantic decoding within the UAV’s flight duration. The task processing latency

for device

i is given by

2.4. Energy Consumption Model

This chapter considers the energy consumption of ground devices and UAVs. The energy consumption model consists of three parts: semantic encoding energy consumption, transmission energy consumption, and semantic decoding energy consumption.

2.4.1. Semantic Encoding Energy Consumption

The semantic encoding energy consumption model for ground device

i can be expressed as

where

is the energy efficiency factor of the device’s computing chip.

2.4.2. Transmission Energy Consumption

For ground device

i, the transmission energy consumption can be expressed as

2.4.3. Semantic Decoding Energy Consumption

The semantic decoding energy consumption model can be expressed as

where

is the energy efficiency factor of the computing chip for all UAVs.

2.5. Semantic Evaluation Model

To assess semantic transmission performance, we introduce two key metrics, semantic transmission performance and original image transmission performance, defined as follows.

Based on the SINR

obtained in (

11), the semantic transmission performance

and the original image transmission performance

from device

i to UAV

j in time slot

n are respectively given by

where

is the logarithmic scale transformation of the SINR,

,

, and

represent the positive constant coefficients of

for different

, and

,

, and

are the positive constant coefficients of

, respectively.

In time slot

n, the transmission performance

of device

i to UAV

j can be expressed as

The transmission performance

of device

i is given by

where

. The transmission is completed within

time slots, and the impact of any excess transmission can be neglected.

3. Problem Formulation

This paper aims to minimize the maximum task processing latency through joint optimization of UAV–device association, trajectories, transmission power, offloading ratios, and compression depths. To simplify subsequent notation, define the UAV–device association variable set as

, the UAV trajectory variable set as

, the transmission power set as

, the task offloading ratio variable set as

, and the compression depth variable set as

. The above optimization problem can be formulated as

In problem

, constraint (

25a) indicates that the transmission performance must be higher than the performance threshold

to ensure effective transmission. (

25b) and (

25c) state that the transmission and computation energy consumption of the ground and UAVs must not exceed the maximum energy threshold. (

25d) specifies that the task offloading ratio takes a value between 0 and 1. (

25e) requires the compression depth to be selected from a numerically discrete set

. (

25f) represents the maximum speed constraint of the UAVs. (

25g) enforces the collision avoidance distance between UAVs. (

25h) represents the transmitted data volume constraint. Since the UAV–device association variables are binary (0 or 1), this constraint is an integer constraint. Additionally, the compression depth selection constraint and the transmitted data volume constraint are non-convex. In summary, it is challenging to solve

using conventional convex optimization algorithms.