Abstract

During crisis situations like the COVID-19 pandemic, nonprofit organizations must rapidly adapt their community engagement approaches, yet traditional co-design methods often fall short in such time-sensitive, multi-stakeholder contexts. This paper examines how design methods need to evolve when working with nonprofits during crises by analyzing our intensive six-month collaboration with five Australian nonprofits serving migrant youth communities. Through Action Research involving over 130 co-design sessions, workshops, and stakeholder meetings, we developed and iteratively refined a social media engagement playbook. Our findings reveal three key methodological innovations: (1) adapting co-design methods for crisis contexts through flexible, asynchronous engagement; (2) managing multiple stakeholder relationships through what we term “nonprofit ecologies”—understanding organizations’ overlapping roles and relationships—and (3) balancing immediate needs with long-term goals through infrastructuring approaches that build sustainable capacity. This research contributes practical methods for conducting collaborative design during crises while advancing a theoretical understanding of how traditional design approaches must adapt to support nonprofits in complex, time-sensitive situations.

1. Introduction

Methodological innovation in crisis contexts presents unique challenges for human–computer interaction (HCI) research and design. The COVID-19 pandemic highlighted both the critical role of nonprofit organizations in community resilience and the urgent need to adapt traditional co-design methods when working with these organizations during crises [1]. While HCI research has explored academic–nonprofit collaborations around fundraising [2], information dissemination [3], and community organizing [4], less attention has been paid to how co-design methods themselves must evolve to meet the demands of crisis situations.

This methodological gap becomes particularly evident when examining how nonprofits engage with multicultural youth communities during crises. These communities face unique barriers around digital engagement and access [5,6], yet traditional co-design approaches often fail to account for the complex organizational ecologies and fluid roles that characterize nonprofit work in crisis contexts [7,8]. As Vines et al. [9] argue, we need new frameworks for understanding how relationships, resource sharing, and organizational dynamics shape design outcomes in these settings.

To address this gap, we investigate three key research questions:

- 1.

- How do traditional co-design methods need to adapt when working with nonprofits during crisis situations?

- 2.

- What methodological challenges emerge when conducting rapid, multi-stakeholder design during crises?

- 3.

- How can we develop more resilient and flexible design approaches for crisis contexts?

We explore these questions through a case study of an intensive community co-design project conducted with five nonprofits in Melbourne, Australia, during the COVID-19 pandemic (November 2020–May 2021). Melbourne experienced the world’s longest COVID-19 lockdown (https://www.publish.csiro.au/ma/pdf/MA22002, accessed on 1 April 2024), providing a unique context to examine methodological adaptation. Through participatory design sessions, we collaboratively developed a `social media playbook’—a design artifact for nonprofits to engage multicultural youth through digital platforms both during and after crises. Our work builds on existing HCI research examining crisis response technologies [10,11] while focusing specifically on methodological innovation.

Our research makes three key contributions to HCI methodology and crisis informatics:

- 1.

- We provide reflections on adapting co-design methods in crisis contexts, identifying specific techniques for managing time pressure, digital constraints, and stakeholder complexity

- 2.

- We surface methodological tensions that emerge when conducting rapid, multi-stakeholder design during crises, offering strategies for navigating these tensions

- 3.

- We propose a new understanding on how “organizational ecologies” shape design outcomes in crisis contexts, extending existing work on design artifacts [12] and community engagement [13]

The goal of this study is to develop and evaluate adapted co-design methods that can support nonprofits during crisis contexts, particularly in multicultural youth communities. Based on the literature and our preliminary observations, we investigated the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1.

Flexible and asynchronous co-design practices are more effective than traditional synchronous workshops in time-pressured, resource-constrained crisis environments.

Hypothesis 2.

Mapping and engaging with “nonprofit ecologies” (i.e., the overlapping roles and relationships among organizations) leads to improved coordination and design outcomes.

Hypothesis 3.

Infrastructuring approaches can simultaneously address immediate crisis needs while building long-term organizational capacity.

2. Background: HCI in Crisis Settings

2.1. Evolution of Co-Design Methods

Co-design emerged from Scandinavian participatory design traditions, building on the premise that involving users would lead to more relevant and impactful design outcomes [14]. This approach conceptualizes design as collective creativity applied throughout the entire design process, emphasizing the importance of surfacing participants’ tacit knowledge rather than solely their explicit competencies [15]. While co-design has been deployed across various contexts—from understanding lived experiences [16] to designing sustainable interventions [17]—its application with underserved communities reveals significant complexities and challenges that warrant critical examination.

A fundamental critique of traditional co-design approaches emerges from their embeddedness in privileged, middle-class contexts [18]. Harrington et al. highlight how community circumstances and historical relationships with research institutions significantly influence engagement with design activities. This critique extends beyond mere logistical challenges, questioning whether conventional design workshops adequately recognize and incorporate communities’ own approaches to creativity and innovation [19]. These insights suggest that meaningful co-design requires moving beyond standard participatory methods to embrace forms that resonate with communities’ existing practices and values.

The challenges become particularly salient when working with nonprofit organizations and community groups. While nonprofits often serve as intermediaries in co-design processes—potentially mitigating some participation barriers—this arrangement introduces its own complexities. Nonprofit stakeholders invest significant resources in these collaborations, from staff time to organizational capacity, making the outcomes particularly consequential for their operations [20]. However, as Erete argues, even when communities effectively utilize technologies to increase their visibility, this does not necessarily translate into increased political power or systemic change [21]. This disconnect highlights the need to critically examine how co-design processes might better support not just technological adoption but also structural transformation.

The temporal demands of co-design present another significant challenge, particularly when working with participants facing competing priorities. Wardle et al.’s work with mothers of young children demonstrates the necessity of flexible research approaches to prevent co-design from becoming an additional burden on already constrained individuals [20]. This observation points to a broader need to reconceptualize co-design methods in ways that accommodate participants’ lived realities while still maintaining meaningful engagement.

2.2. Methodological Challenges in Crisis Contexts

Designing under crises introduces its own set of challenges. In addition to physical and material harm, crises bring disruption to normal patterns of social and cultural life. Populations are then forced to re-implement or re-imagine what was previously considered `everyday’ routines of their life. Much work within HCI has presented the varied ways in which society carries out crisis informatics, i.e., the study of how crisis preparedness, response, and recovery intersect with information and communication technologies [22].

By using social networking sites (SNS) like Facebook, affected populations can take proactive steps both during and after recovery, for instance, by determining the safety of family and friends and rebuilding their social scaffolding [23]. Although, as in other areas of technology use, inequalities can be perpetuated through an overly simplistic analysis of social media use, for instance, mistaking social media activity for actual need [24]. Another consideration is that analyses of social media datasets from disaster events have suggested that only a tiny portion of messages posted are generated by eyewitnesses [25,26]. SNS have increasingly served as spaces where engaged populations seek to take part in community development, crisis response, and activism [11,27,28,29]. This is partly because of the flexibility and benefits of using popular social networking sites, as opposed to bespoke sites hosted by the organization [4].

Nonprofits are thoroughly part of the “patchwork of actors” who utilize social media to support communities in crisis recovery and community development [28]. In the crisis landscape, beyond the immediate recovery, social media is pivotal for nonprofits to collect tacit knowledge through community stories [30] to learn about community needs and the impact of nonprofit programs. Posting multimedia content helps nonprofits engage their target audience online, although turning online engagement into concrete responses (i.e., financial support, event attendance) remains a challenge [3]. The caveat, however, is that such research is often focused on the use of broadcast, social media posts (for instance, nonprofits posting using their Facebook page). As Hou et al. posit, “nonprofits [fail] to utilize social media for dialogic communication” [3]. However, there are notable examples of social media being utilized by researchers as a design space to create innovative community engagements. In WhatFutures [31], Lambton-Howard et al. use WhatsApp to engage 6000 global volunteers from the Red Cross movement about the future of humanitarianism using a gamified future forecasting approach. Elsewhere, Crivellaro et al. piloted the Let’s Talk Parks [32] toolkit for city-wide public engagement by augmenting in-person public consultations with online Twitter-based sessions. These examples illustrate the potential for using public and private social media spaces creatively for community engagement.

We also drew inspiration from the efforts of Asad et al., who have demonstrated the value of a playbook in providing a roadmap for community engagement for practitioners and civic bodies [33]. Their playbook was aimed more broadly at city-scale engagements. Nevertheless, the key benefit of a playbook is that rather than starting from a blank slate (and reinventing the wheel), community engagement can get a rolling start by building on existing best practices.

3. Context

The COVID-19 pandemic in Melbourne, Australia, led to strict lockdown measures disproportionately affecting migrant youth in the northern and western suburbs [34]. These areas faced higher case numbers and economic disruptions, exacerbating the digital divide and highlighting the need for inclusive ICT infrastructure and digital literacy programs. The pandemic intensified existing inequalities, causing mental health issues, social isolation, and economic hardship among multicultural communities [35]. Young people and international students faced compounded disadvantages due to educational disruptions and limited access to digital resources [36]. In response, the Victorian government established a CALD Communities Taskforce, providing funding and support to leverage ICTs for improved communication, service delivery, and community engagement during crises.

4. Methodology

The core research team, consisting of six academics with backgrounds in community development and migration, secured funding from the government task force to conduct a research project supporting nonprofits in effective social media communication. The fast-tracked project, running from November 2020 to May 2021, engaged multiple diverse multicultural nonprofits (see Table 1). We collaborated with multicultural youth workers (sometimes referred to as bicultural workers in the sector) from each nonprofit to co-design tailored community engagement activities addressing priority COVID-19-related issues. These activities leveraged young people’s digital capabilities to address core community challenges, utilizing both virtual and in-person participatory engagement methods.

Table 1.

Nonprofits we engaged as partners in the co-design process.

4.1. Reflexivity Statement

As researchers working at the intersection of HCI and community development, we acknowledge that our positionality fundamentally shapes how we approach this work. Our team included four women researchers and researchers from South Asian, South-east Asian, Middle-Eastern, and Pacific Islander backgrounds, bringing perspectives that are simultaneously insider and outsider to the communities we engage with. We have experienced firsthand both the limitations of deficit-focused research paradigms and the transformative potential of work that centers community strengths and aspirations.

While our identities give us lived experience navigating multicultural contexts and understanding the nuances of nonprofit engagement with migrant communities, we recognize that we do not speak for or represent all migrant experiences. Rather, our backgrounds make us acutely aware of the importance of creating space for communities to articulate their own priorities and definitions of success. Our combined expertise spans HCI, community development, participatory design, and migration studies, allowing us to bridge technical and social perspectives. This interdisciplinary lens helped us critically examine how crisis response technologies can move beyond addressing immediate needs to support long-term community flourishing.

4.2. Research Approach

We adopted an Action Research (AR) approach [37], emphasizing community-based research [17] and trust-building in co-design [38]. The project involved weekly team meetings, co-design meetings with partners, and workshops. We also met fortnightly with representatives of the State Government’s CALD Communities Taskforce, which had commissioned the broader initiative. These meetings served three purposes: (1) to ensure alignment with rapidly changing government communications priorities during the pandemic, (2) to provide accountability and progress updates on nonprofit engagement activities, and (3) to channel nonprofit partners’ perspectives into policy discussions. Our primary contact was a program officer from the Department of Premier and Cabinet, who acted as liaison between government and community organizations. While these meetings were not the focus of our research, they provided important context and ensured that nonprofit-driven insights were visible at the policy level.

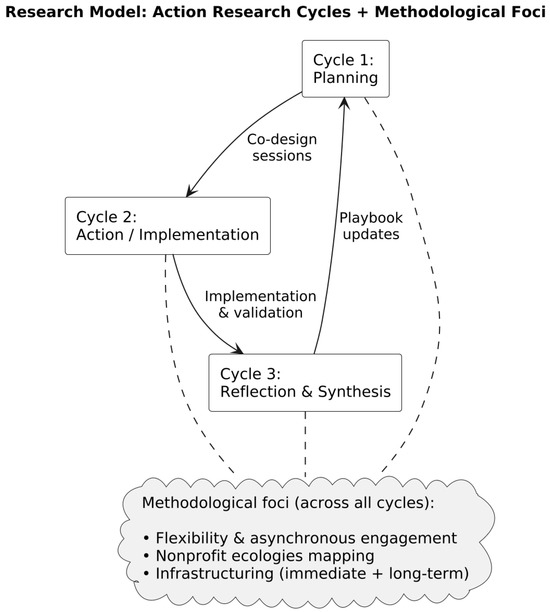

Our AR process followed three main cycles over the 6-month period:

Cycle 1 (Months 1–2): Initial engagement with nonprofits to understand their needs and contexts through planning meetings and preliminary co-design sessions. Each cycle concluded with team reflection sessions to refine our approach.

Cycle 2 (Months 3–4): Collaborative development and testing of social media engagement strategies through intensive co-design workshops, followed by implementation support.

Cycle 3 (Months 5–6): Evaluation of implemented strategies and synthesis of learnings into the playbook format through participatory analysis sessions with nonprofit partners.

Data collection was systematic across these cycles and included the following:

- 550+ min of audio-recorded co-design sessions and semi-structured interviews;

- Detailed field notes from 132 meetings across all partner organizations;

- Digital traces, including WhatsApp and Facebook Messenger conversations;

- Email correspondence and phone call notes;

- Research team reflection logs.

We employed thematic analysis [39] to analyze the data, following a rigorous six-phase process: (1) familiarization with data through multiple readings, (2) initial coding using both inductive and deductive approaches, (3) theme development, (4) theme refinement, (5) theme definition, and (6) final analysis. To ensure analytical rigour, at least two researchers coded each data source independently before comparing and reconciling their analyses. We also conducted regular checks with nonprofit partners (who were part of the research team for analysis purposes) to validate our interpretations.

Ethics approval was obtained from the first author’s IRB prior to beginning the research. Given the sensitive nature of working with marginalized communities during crisis, we prioritized reciprocity and flexibility in our approach [40,41]. Rather than positioning ourselves as external researchers studying the organizations, we actively worked to support their immediate needs while documenting the process. This included being responsive to changing organizational priorities and adapting our data collection methods to minimize the burden on already-strained nonprofit staff.

4.3. Recruiting Partner Nonprofits

We employed purposive sampling to select partner organizations, developing selection criteria through iterative discussions between our research team and the government taskforce. The final criteria included the following:

Community Impact: Organizations serving communities experiencing particular disadvantage during COVID-19, especially those facing compound challenges of digital exclusion, language barriers, and economic hardship.

Organizational Diversity: Representatives from different types of nonprofits (peak bodies, grassroots organizations, social enterprises) to understand how digital engagement strategies might need to vary based on organizational capacity and structure.

Existing Relationships: Given the crisis context and compressed timeline, we prioritized organizations where either the research team or taskforce had existing relationships to enable rapid trust-building and engagement.

Through this process, we selected five organizations representing different approaches to supporting multicultural youth:

Young Victorians Unite (YVU): A peak body organization for multicultural youth, specifically their `Le Mana’ program serving Maori and Pasifika communities. YVU sought to build sustainable in-house capacity for digital storytelling and community documentation.

The Bramble: The community engagement arm of a major sports club, working in areas with high migrant populations facing socioeconomic barriers. Their existing `Voice your Voice’ program provided an opportunity to develop structured approaches to collaborative digital media creation in school settings.

FilipinoX: A volunteer-led migrant advocacy organization focused on supporting Filipino international students and youth severely impacted by COVID-19 restrictions. They aimed to amplify youth voices through digital storytelling on social media for both community building and advocacy.

Karen Victorian Association (KVA): An organization supporting Karen refugees, facing particular challenges in maintaining multilingual community engagement (across English, Pwo, and Sgaw languages) during the shift to online interactions. They sought to develop youth-led approaches to multilingual digital engagement.

YouthHub: A youth-led social enterprise employing multicultural young people as consultants on youth engagement. They identified podcasting as an emerging medium of interest, seeking to build capacity in audio storytelling among their youth associates.

4.4. Our Engagement Process

Our research process followed a systematic three-stage approach to develop social media engagement strategies with and for multicultural nonprofits. Each stage is built upon learnings from the previous stage, allowing us to iteratively develop and refine our understanding while maintaining methodological rigour.

4.5. Research Model

Our overall research model integrated an Action Research (AR) approach with iterative co-design practices, guided by three methodological foci identified in the literature and refined through our fieldwork: (1) enabling flexibility and asynchronous engagement, (2) understanding and working within “nonprofit ecologies,” and (3) balancing immediate needs with long-term capacity building through infrastructuring. The model was operationalized across three AR cycles (planning, action/implementation, and reflection), with continuous data collection and partner validation at each stage. Figure 1 provides a schematic overview of this model.

Figure 1.

Research model integrating Action Research cycles with three methodological foci.

4.5.1. Understanding Context and Building Relationships

We began with exploratory engagement sessions conducted via Zoom with youth workers from each organization. These semi-structured sessions focused on understanding (1) how COVID-19 had impacted their youth engagement work, (2) their current digital and social media practices, and (3) specific challenges they faced in maintaining youth connections during lockdown. We conducted 2–3 sessions with each organization, each lasting 60–90 min. These sessions were recorded, transcribed, and analyzed using open coding to identify key themes and challenges that informed the subsequent co-design stage.

4.5.2. Collaborative Design Process

Building on insights from the initial stage, we implemented a structured co-design process tailored to each organization’s context. This process involved regular working sessions (detailed in Table 2) following a five-phase framework:

Table 2.

Internal, external, and participant meetings held across nonprofits.

Understanding: Deep dive sessions exploring specific youth engagement challenges and social media opportunities unique to each organization’s context.

Ideation: Collaborative brainstorming sessions to generate potential approaches, drawing on both organization expertise and relevant case studies (similar to the approach of [33,42]).

Planning: Detailed development of selected approaches, including timeline creation, resource identification, and risk assessment.

Implementation: Active support during rollout of co-designed strategies, including technical assistance and regular check-ins.

Review: Structured reflection sessions to evaluate outcomes and identify learnings.

Each phase included documentation through detailed field notes, recordings where appropriate, and regular research team debriefing sessions to ensure methodological consistency across organizations.

4.5.3. Synthesis and Knowledge Translation

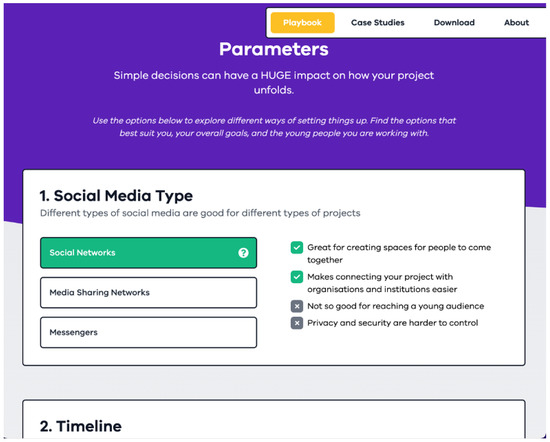

The final stage focused on synthesizing learnings into a format useful for the broader nonprofit sector. We collaborated with a UX designer to translate our findings into a social media playbook through the following process:

- Systematic analysis of data from all organizations to identify common patterns, challenges, and successful strategies

- Development of a framework categorizing different approaches based on organizational goals and capacities

- Creation of specific “plays” documenting successful strategies, including

- 1.

- Contextual requirements for implementation;

- 2.

- Resource needs and considerations;

- 3.

- Step-by-step implementation guidance;

- 4.

- Evaluation metrics and success indicators.

- Iterative refinement through feedback sessions with partner organizations

Figure 2 illustrates how we structured the engagement parameters within the playbook based on our analysis. This systematic approach to synthesis helped ensure our findings would be both academically rigorous and practically useful for nonprofits.

Figure 2.

Excerpt from social media playbook’s section on Parameters. The section described the following parameters: (1) Social Media Type; (2) Timeline; (3) Groups and Teams; (4) Responsibilities; (5) Openness.

Throughout all stages, we maintained regular analytical memos and conducted weekly research team meetings to discuss emerging patterns and methodological considerations. This rigorous documentation process supported both our ongoing analysis and the development of generalizable insights for the field.

5. Findings

5.1. Evolving Understanding of Youth Engagement During Crisis

Our analysis revealed two key shifts in understanding how to effectively engage youth during crisis: reconceptualizing youth’s role in community networks, and reframing engagement approaches beyond crisis-focused dialog. These insights emerged through our thematic analysis of interview transcripts, field notes, and recordings from over 550 min of meetings with nonprofit partners.

First, our initial assumption that youth could be engaged as an isolated demographic group proved misaligned with nonprofits’ understanding of youth as interconnected community nodes. Through our interviews and co-design sessions, we found that nonprofits conceptualized youth engagement through what we term “networked impact”—where youth serve as vital information conduits and cultural bridges within broader community systems. As one multicultural youth nonprofit leader explained,

My deep belief is that young people will listen if it comes from other young people but also from…people who look and sound like them.

This networked impact manifested in several ways we observed across our fieldwork. In workshops with YVU and FilipinoX, youth participants naturally drew in older community members affiliated with youth work, demonstrating how youth engagement catalyzed broader community involvement. During COVID-19 communications specifically, youth emerged as critical “information bridges,” leveraging their digital fluency to triangulate and transmit vital health information across generations and platforms. One youth participant described this multi-channel information brokering:

I [had] Facebook, Channel 9, Channel 7 media outlets turned on. As soon as you get a message, you relay it to the community and send a text message through WhatsApp or something…and then you just make follow-up calls with people that did not understand.

This finding aligns with prior work on crisis informatics showing how trusted community members become critical information mediators during emergencies [REF]. However, our work extends this by highlighting youth’s specific role as digital–social bridges during prolonged crisis.

Second, our research revealed the limitations of crisis-centric engagement approaches. Initial attempts to directly discuss COVID-19 impacts with youth met consistent resistance from youth workers who emphasized that “young people do not want to talk about COVID.” This resistance stemmed from what our analysis identified as engagement fatigue—youth were overwhelmed by constant crisis messaging from public organizations, impacting their mental health and wellbeing [43].

This insight prompted a methodological pivot in our approach. Rather than focusing on COVID-19 attitudes directly, we reframed our engagement strategy to

- 1.

- Center youth’s everyday communication practices and priorities;

- 2.

- Build youth workers’ capacity to use familiar social media platforms for community dialog;

- 3.

- Create spaces for youth to discuss broader impacts on their lives (education, employment, social connections).

This methodological evolution reflects recent work on crisis research methods that emphasizes the need for flexible, community-centered approaches during extended emergencies [44]. Our findings suggest that effective youth engagement during crisis requires moving beyond direct crisis discourse to create spaces for processing broader life impacts through familiar digital channels.

5.2. Organizational Ecologies in Crisis Response

Our analysis revealed how nonprofits operate within intricate organizational ecosystems during crisis response. Through our fieldwork and analysis of meeting transcripts, we identified distinct organizational configurations while also observing how these configurations overlap and evolve based on community needs.

A senior nonprofit leader articulated this ecosystem approach:

We played an important role in assessing individual and family needs, linking that back with our local partners, including, local and state government working with other community not-for-profits and services to ensure that people’s food, medical, educational needs were all taken care of.

Our analysis identified five key organizational configurations in how nonprofits structured their community engagement work:

- 1.

- Community-Focused Organizations: These organizations maintain deep connections with specific cultural communities, exemplified by FilipinoX’s focused work with Filipino community members. This configuration enabled targeted messaging and culturally appropriate engagement strategies during the pandemic.

- 2.

- Network Facilitators: Organizations like KVA act as network hubs, coordinating multiple grassroots groups through structures like the Victoria Karen Communities Network Group (VKCNG). During our study period, KVA coordinated COVID-19 information distribution across multiple community organizations.

- 3.

- Capacity Builders: Exemplified by YVU’s work with smaller organizations, these groups focus on strengthening other organizations’ capabilities. The Le Mana program engaged over 2500 young people through capacity-building initiatives during 2019–2020, demonstrating substantial reach through this approach.

- 4.

- Grassroots Organizations: These volunteer-led groups provide direct community support, operating with high community trust but limited resources. They played critical roles in rapid information dissemination during the early pandemic phases.

- 5.

- Civic Connectors: Organizations like Bramble bridge between formal institutions (schools, sports clubs) and communities. During our study, Bramble facilitated connections between schools and multicultural communities for COVID-19 messaging.

Our analysis revealed these configurations are not mutually exclusive but represent different organizational capabilities that can be activated based on community needs. As detailed in the vignette presented in Box 1, FilipinoX demonstrated this flexibility by operating both as a community-focused organization and as a network facilitator, coordinating with multiple community groups through various social media channels.

The vignette illustrates how FilipinoX leveraged different organizational configurations to reach young people effectively. Their work with Anakbayan (youth activism) and PINAS (Filipino scholars) shows how they activated different network connections based on project needs. While they maintained strong direct community engagement through skilled volunteers, their networked approach enabled broader reach and enhanced message credibility through multiple community channels.

Box 1. Vignette from FilipinoX.

We partnered with FilipinoX to better understand how a social media playbook might support their work in addressing challenges faced by young Filipinos in Australia. We discovered that FilipinoX worked closely with four other community organizations (which were unincorporated grassroots community groups). Facebook was its main social networking site of choice, and it used Pages, Groups and Messenger (group chats) in nuanced ways to engage its constituents. When planning a social media campaign, FilipinoX would utilize Messenger groups to bring together young people from the previously mentioned community groups. When a project to support young Filipinos and international students is initiated, FilipinoX would collaborate with Anakbayan (a youth activism organization) and PINAS (Philippines Studies Network in Australia—a group of Filipino scholars involved in Filipino diasporic and cultural studies). While FilipinoX Melbourne has many skilled volunteers, who are proficient in designing resources for the organization’s online campaigns, it remains intricately linked to the other two organizations, which allows further reach to ensure that its messaging is both appropriate and accessible to young people.

5.3. Adapting Project Framing to Organizational Contexts

Our analysis revealed how the initial open-ended nature of the social media playbook project created engagement challenges with nonprofit partners. Through iterative engagement with organizations, we identified how different framing approaches emerged to align with each organization’s culture and capacity.

Initially, nonprofit partners expressed uncertainty about both the benefits of participation and the expected level of involvement from their staff and constituents. As we worked with each organization, distinctive frames emerged that resonated with their organizational contexts. For KVA, the project was ultimately framed as a “social media masterclass” for their youth volunteers. YouthHub approached it as professional development, while FilipinoX conceptualized it as a grassroots marketing campaign. These frames served to anchor the project within existing organizational practices and expertise.

However, our analysis also revealed limitations and challenges with specific frames. The case of YouthHub illustrates these complexities. Initial discussions centered on providing digital media production support for an existing YouthHub project that involved training multicultural youth recruited through their networks. A co-design partner reflected on the challenges this created:

It is hard. I experienced, and this is also a learning for me, when it comes to planning and design, it is that a lot of the time, the end users kind of don’t even know what they want. So, it is like, I think for me, how I approach it now—it is more of a presentation of different options rather than them trying to ideate from the get-go from a very foundational level.

The crisis context amplified these challenges, echoing findings from prior work on nonprofit collaboration during emergencies [20]. Time constraints and communication difficulties led to project delays until we later reframed the collaboration as professional development for youth associates.

We also observed how frames could create misalignment. In one case, a nonprofit misinterpreted our proposed social media methods as marketing tactics, noting they had already engaged a marketing company for their online presence. This highlighted the importance of clear frame articulation to avoid misconceptions.

Beyond organizational framing, our analysis revealed the critical role of media metaphors in engaging young people effectively. We found that nonprofits had diverse existing social media practices, from Facebook live broadcasts to Instagram graphics. This variety necessitated tailored approaches building on existing media literacy. Working with Bramble demonstrated this principle: previous attempts at using traditional storyboarding for student filmmaking had faced challenges. We developed an alternative approach based on “story beats” inspired by screenplay practices [45]. A Bramble co-design partner described the impact:

There was more engagement with the technical side of things this year…they understood and got more visibility and more learning around what it takes to make a good video, like the understanding of ’story beats’…this concept of beats is more accessible, it’s easier to produce and then easier to build off it.

This experience validated our approach of developing templates and scaffolds that built upon communities’ existing media literacies. While the playbook focused on pandemic-era youth engagement, it evolved into a capacity-building tool that could benefit organizations beyond the immediate crisis context.

During the final synthesis stage, we conducted reflection sessions with all five nonprofit partners to evaluate the usefulness of the playbook. Partners reported that the resource was both practical and adaptable to their ongoing programs. For example, one YouthHub leader noted the following: “The playbook helped us think through possibilities we hadn’t considered, while still letting us stay true to how our community actually uses these platforms.” Similarly, a FilipinoX volunteer emphasized that “having concrete examples of campaign ‘plays’ gave us confidence to run our own online activities.” These reflections suggest that, beyond the immediate co-design process, the playbook provided a durable reference point that partners could continue to use in their digital engagement work.

5.4. Navigating Researcher Identity and Positionality

Our analysis revealed how researchers’ institutional and personal identities significantly shaped partnership dynamics with nonprofit organizations during crisis response. Through examining our fieldnotes and meeting transcripts, we identified specific ways these identities influenced research relationships and engagement approaches.

The institutional identity of “social media consultant” emerged as a key framework through which nonprofits engaged with our research team. This positioning aligned with nonprofits’ immediate needs for technological support during the pandemic crisis, reflecting patterns identified in prior crisis informatics research [46]. Our data showed that nonprofits often struggled with the same technologies they relied upon for civic engagement, corroborating findings from recent studies of Filipino diaspora organizations in Australia [47].

However, our analysis revealed that personal identities and connections proved equally crucial in establishing effective partnerships. Building on Talhouk et al.’s [48] observations about researcher–community relationships requiring active response beyond empathetic listening, we found that personal connections facilitated deeper organizational access and trust. For example, one researcher’s marriage connection to the Pasifika community became a regular point of introduction in community gatherings, while another researcher’s Filipino migrant background enabled nuanced engagement with FilipinoX and KVA.

These personal connections manifested in practical accommodations that blurred traditional research boundaries. Meeting schedules often shifted to evenings and weekends to accommodate volunteer availability, particularly with KVA and FilipinoX. Our field notes documented how these scheduling adaptations created intersections between researchers’ personal and professional lives. This finding builds on Toombs et al.’s [49] work on “caring relationships” in community research, demonstrating how such relationships develop through practical accommodations.

The analysis also revealed tensions in managing these dual identities. While project funding provided researchers flexibility to engage in multiple roles, internal team discussions highlighted disagreements about maintaining consistent researcher–organization pairings versus rotating team members. These tensions reflected broader challenges in balancing research rigor with relationship maintenance.

Our engagement often extended beyond traditional researcher roles, particularly in skill-sharing contexts. For instance, field notes documented researchers conducting podcasting workshops despite limited expertise in this medium. Rather than undermining credibility, our data showed this approach enhanced affinity with nonprofit partners who similarly learned new skills on the job. This finding adds nuance to understanding how researcher expertise is perceived in community settings during crisis response.

The Action Research framework provided structure for these identity negotiations, allowing research priorities to be shaped by nonprofit needs. For example, YVU’s desire for rapid content production capabilities and Bramble’s need for school-specific toolkits influenced project direction. This reflects how personal and institutional identities served as bridges between academic research goals and community crisis response needs.

6. Discussion and Lessons Learned

Our research contributes key methodological insights about adapting co-design approaches during crisis situations through our intensive collaboration with five nonprofits over six months during COVID-19. We analyze how traditional participatory methods needed to evolve to meet the unique challenges of rapid, multi-stakeholder engagement during crisis response while maintaining methodological rigor and community-centered values.

6.1. Methodological Tensions: Balancing Structure and Flexibility

A fundamental methodological challenge emerged around how to adapt traditional co-design approaches, which thrive on open-ended exploration [50], within the constraints of crisis response where organizations needed clear, immediate value. While co-design typically embraces ambiguity to allow novel solutions to emerge organically, we found this created friction when working with nonprofits under intense resource pressure during COVID-19.

Our initial open-ended approach of positioning ourselves as a general “technological capacity” for youth engagement proved challenging for two key reasons. First, nonprofit partners struggled to envision possibilities within such a broad scope while managing crisis demands. Second, the ambiguity conflicted with their need for concrete, immediate support for existing programs. As one nonprofit leader noted, “We need help with specific programs we’re already running—it’s hard to think about new initiatives right now.” [KVA]

Through iterative refinement of our methodology, we developed a hybrid approach that provided more structure while preserving co-design’s generative potential. This involved creating tailored engagement frameworks for each nonprofit based on their specific organizational context and constraints, explicitly distinguishing between immediate program support and longer-term playbook development, and taking a more active role in facilitating ideation and implementation when partner bandwidth was limited.

This methodological evolution aligns with Le Dantec et al.’s [8] observation that community-based design requires developing new “dialogs and vocabularies.” However, our work extends this by demonstrating how such methodological adaptations must be accelerated during crisis contexts while still maintaining participatory principles.

The tension between structure and flexibility connects to broader questions in HCI about adapting our methods for crisis response. While previous work has examined crisis informatics [51] and nonprofit engagement [52], less attention has been paid to how our core design methodologies must evolve. Our findings suggest that rather than simply applying traditional co-design approaches faster, we need new hybrid methodological frameworks that can balance immediate needs with longer-term generative potential.

As Huybrechts [53] argues, we need ways to reconfigure how institutions engage in design work. Our adapted methodology provides one model for how to structure co-design processes when working with resource-constrained organizations while still preserving participatory values. The key is creating clear frameworks that guide engagement while maintaining space for emergence and adaptation.

Lesson #1: When adapting co-design methods for crisis contexts, establish clear methodological frameworks upfront that provide structure and immediate value for partners while preserving space for emergent possibilities. This requires explicitly distinguishing between short-term support and longer-term co-design goals.

6.2. Institutional Design Methods in Crisis Contexts

Our research reveals critical insights about how traditional HCI design methods must evolve when working with institutions rather than individuals during crisis response. While much HCI research has examined individual-level crisis response [51], less attention has been paid to how we effectively design with and through institutions that serve as critical information infrastructure during crises.

Through our collaborations, we identified three key methodological requirements for institutional design during crises. First, information dissemination must be carefully orchestrated over time rather than delivered all at once. When working with nonprofits, we found that their deep community knowledge allowed them to strategically sequence and contextualize crisis information in ways that prevented overwhelming their constituents. As one nonprofit leader explained, “We know when our community is ready to receive certain messages and how to frame them effectively.” [FilipinoX]

Second, institutional design methods must explicitly account for and leverage existing organizational capabilities around content generation and community engagement. The nonprofits we worked with already had established practices for creating culturally relevant content and maintaining community dialog. However, they needed methodological support to adapt these capabilities to crisis communication. This extends previous work on nonprofit social media use [54,55] by demonstrating how design methods can systematically build on existing institutional strengths rather than imposing entirely new approaches.

Third, relationship-building methods must be accelerated while maintaining depth. Traditional design approaches rely heavily on informal, face-to-face interactions to build trust over time [44]. However, crisis contexts demand faster relationship development, often in virtual settings where informal interactions are limited [56]. We developed new methodological techniques for rapid trust-building through

- 1.

- Explicitly acknowledging and working within institutional constraints;

- 2.

- Creating clear value propositions tied to immediate organizational needs;

- 3.

- Establishing structured but flexible engagement frameworks;

- 4.

- Leveraging existing organizational partnerships and networks.

This connects to broader methodological questions in HCI about designing with institutions under time pressure. While previous work has examined rapid design methods [52], these approaches often focus on individual users rather than institutional partnerships. Our findings suggest that institutional design methods during crises require unique considerations around information orchestration, capability leveraging, and accelerated relationship building.

These methodological insights have implications beyond crisis contexts. They demonstrate how HCI methods can be adapted to work more effectively with institutions as design partners, particularly in situations requiring rapid response while maintaining community-centered values. This addresses calls in the literature for more research on design methods that can operate across different organizational and political domains [57].

Lesson #2: When designing with institutions during crises, methods must support strategic information orchestration, leverage existing organizational capabilities, and enable accelerated yet meaningful relationship development. This requires explicitly adapting traditional HCI approaches to account for institutional contexts and constraints.

6.3. Artifacts as Methodological Resources for Design Translation

Our research contributes insights into how design artifacts (such as toolkits and playbooks) can support methodological translation across different organizational contexts during crisis response. While previous work has examined how design methods transfer between settings [57], less attention has been paid to creating resources that enable organizations to adapt methods to their specific contexts. Our development of playbooks as methodological resources provides key insights for this challenge.

Playbooks differ fundamentally from prescriptive guides or “cookbooks” in how they support methodological adaptation. Rather than providing step-by-step instructions that flatten contextual differences, playbooks serve as abductive resources that help organizations explore possibilities within their unique circumstances. This aligns with Steen’s [58] conception of open problem solving, where both the solution approach (“how”) and specific intervention (“what”) emerge through engagement with the context.

Our findings reveal three key principles for developing effective methodological resources:

First, resources must support local interpretation while maintaining methodological rigor. The playbook achieved this by providing clear frameworks for social media engagement while encouraging organizations to adapt these frameworks based on their community’s specific practices and values. As one nonprofit leader noted, “The playbook helped us think through possibilities we hadn’t considered, while still letting us stay true to how our community actually uses these platforms.”

Second, resources should acknowledge and build upon existing organizational capabilities. Rather than prescribing entirely new approaches, the playbook helped organizations identify how their current strengths could be leveraged in new ways. This extends Dreessen et al.’s [59] work on generativity in design by demonstrating how methodological resources can enhance rather than replace existing organizational capacities.

Third, resources must explicitly support the plurality of approaches that exist within communities. Our findings showed that no single organization represents an entire community’s needs or practices. The playbook acknowledged this by providing multiple engagement models and encouraging organizations to adapt these based on their specific stakeholder relationships. This addresses previous critiques of design approaches that assume homogeneous community representation [60].

These insights connect to broader questions in HCI about how we create design resources that enable methodological adaptation while maintaining rigor. While previous work has examined how methods transfer between contexts [61], less attention has been paid to creating resources that actively support contextual translation. Our findings suggest that playbooks, when designed as abductive resources rather than prescriptive guides, can help bridge this gap.

This has implications beyond crisis contexts. As HCI increasingly engages with complex organizational and community settings, we need better approaches for sharing methodological knowledge in ways that enable local adaptation. The playbook approach provides one model for how design resources can support rigorous yet flexible method translation across contexts.

Lesson #3: Create methodological resources that support abductive exploration rather than prescriptive guidelines. These resources should enable organizations to adapt methods to their context while maintaining rigor, building on existing capabilities, and supporting plural approaches within communities.

6.4. Managing Resource Constraints in Crisis Design

Our research reveals critical methodological insights about managing resource constraints when conducting design work during crisis situations. While previous work has examined resource limitations in nonprofit contexts [62], crisis situations introduce unique challenges around both organizational capacity and information management that require methodological innovation.

We identified two interrelated resource challenges that affected our methodological approach. First, organizations faced severe constraints on staff time and attention due to crisis demands. Traditional co-design methods assume organizations can dedicate time to exploring new possibilities. However, we found nonprofits were primarily focused on maintaining existing programs while managing crisis response. As one nonprofit staff described in our initial planning stages, “We know we need to think about new approaches, but right now we’re just trying to keep our current programs running.”

Second, information itself became a constrained resource requiring careful management. During COVID-19, nonprofits had to balance distributing critical health information with avoiding overwhelming their communities [63]. This created what we term an “information constraint”—organizations needed to be selective about what information they shared and when, even when that information was important. These constraints required us to develop new methodological approaches:

Rather than asking organizations to envision entirely new programs, we shifted to identifying how existing programs could be enhanced through targeted support. This allowed organizations to leverage familiar contexts while still incorporating innovation. We took a more active role in implementation, particularly around training and event facilitation. This helped address capacity constraints while maintaining collaborative principles. We developed structured approaches for information staging and sequencing, helping organizations strategically manage information flow to their communities.

These insights extend previous work on resource constraints in HCI [56] by demonstrating how crisis contexts require methods that can adapt to both operational and informational constraints. While prior research has examined each type of constraint separately, our findings suggest they are deeply intertwined during crises and must be addressed holistically. This has implications for how we design methodological approaches for resource-constrained contexts more broadly. Rather than seeing constraints purely as limitations to work around, our findings suggest they can actually help focus design work in productive ways by forcing careful consideration of existing capabilities and information flows.

Lesson #4: When designing during crises, methods must explicitly account for both operational and informational resource constraints. This requires approaches that build on existing programs, provide implementation support, and enable strategic information management.

Our analysis provides evidence supporting each of the three hypotheses proposed in the Introduction. H1 was validated through the successful implementation of flexible and asynchronous co-design practices (e.g., WhatsApp, Messenger), which enabled participation under severe time and resource constraints. H2 was supported by our identification of distinct but overlapping organizational configurations (“nonprofit ecologies”), which shaped how design outcomes were coordinated and scaled across communities. H3 was validated by our infrastructuring approach: while playbook activities addressed urgent crisis needs, they also strengthened long-term digital engagement capacity (e.g., podcasting at YouthHub, multilingual event delivery at KVA). Together, these findings affirm the methodological value of adapting co-design practices through flexibility, ecological awareness, and infrastructuring in crisis contexts.

7. Limitations

Our research on methodological adaptations during crisis contexts has several important limitations to acknowledge. First, while our intensive collaboration with five nonprofits provided rich insights into methodological challenges and innovations, the accelerated timeline of crisis response limited our ability to conduct longer-term evaluation of how these adapted methods performed over time. Future work should examine the sustainability and evolution of crisis-adapted design methods as organizations transition from immediate response to recovery phases.

Second, while we identified key patterns in how organizational ecologies shape design outcomes during crises, our findings are necessarily bounded by the Melbourne context and the specific dynamics of COVID-19 response. Additional research is needed to understand how these methodological insights translate to other types of crises and institutional contexts. This is particularly important for understanding how design methods must adapt differently for sudden onset crises (e.g., natural disasters) versus prolonged crises like pandemics.

Finally, our methodological focus on organizational adaptation and collaboration meant we did not directly examine how these adapted methods impacted end beneficiaries. While we documented how nonprofits perceived and utilized our methodological innovations, future work should investigate how crisis-adapted design methods influence program outcomes and community engagement from constituents’ perspectives.

While our study is grounded in the specific context of Melbourne during the COVID-19 pandemic, the methodological insights are transferable to other types of crises. Contexts such as natural disasters, refugee displacement, or economic shocks similarly require nonprofits to balance immediate response with long-term capacity building, manage overlapping stakeholder relationships, and adapt engagement methods to digital constraints. Future research should test the adaptability of our framework in these varied settings to better understand its broader applicability.

8. Conclusions

This research contributes important methodological insights about adapting traditional co-design approaches for crisis contexts through our intensive six-month collaboration with nonprofits during COVID-19. Our findings reveal how design methods must evolve to address three key challenges during crises: (1) balancing structure and flexibility when organizations face severe resource constraints, (2) managing complex stakeholder relationships through what we term “nonprofit ecologies”, and (3) developing sustainable capacity while meeting immediate needs.

These methodological innovations have implications beyond crisis response. They demonstrate how HCI methods can be adapted to work more effectively with institutions as design partners, particularly in situations requiring rapid response while maintaining community-centered values. Our findings suggest that rather than simply accelerating traditional approaches, we need new hybrid methodological frameworks that can balance immediate needs with longer-term capacity building.

This research opens up important directions for future work on crisis-adapted design methods, particularly around understanding how different types of crises require different methodological innovations, how adapted methods perform over longer time horizons, and how we can better support institutional design partners in building sustainable crisis response capacity.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.V. and P.O.; methodology, D.V., T.B. and J.P.S.; software, T.B. and J.P.S.; validation, D.V., C.R., R.P. and R.W.; formal analysis, D.V., C.R., R.P. and R.W.; investigation, D.V.; resources, D.V.; data curation, M.T. and J.P.S.; writing—original draft preparation, D.V.; writing—review and editing, D.V., J.P.S., T.B. and P.O.; visualization, D.V.; supervision, D.V.; project administration, R.P. and M.T.; funding acquisition, D.V., C.R., R.W., P.O. and T.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by State Government of Victoria’s Department of Premier & Cabinet (DPC).

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee of Monash University (ID: 27027; date of approval: 3 February 2021).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. Written informed consent has been obtained from the participating stakeholders to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

All case studies produced through this research are available at https://playbook.actionlab.dev. Accessed on 1 April 2025.

Acknowledgments

We wish to acknowledge the generous contributions from the partner organizations involved in this Action Research project, including Centre for Multicultural Youth (CMY), The Huddle (North Melbourne Football Club), Migrante Melbourne, Australian Karen Organisation (AKO) and YLab.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Fitzpatrick, T.; Molloy, J. The role of NGOs in building sustainable community resilience. Int. J. Disaster Resil. Built Environ. 2014, 5, 292–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goecks, J.; Voida, A.; Voida, S.; Mynatt, E.D. Charitable Technologies; ACM Press: New York, NY, USA, 2008; p. 689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Y.; Lampe, C. Social Media Effectiveness for Public Engagement. In Proceedings of the 33rd Annual ACM Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 18–23 April 2015; Volume 4, pp. 3107–3116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lampe, C.; Roth, R. Implementing Social Media in Public Sector Organizations; ACM Press: New York, NY, USA, 2012; pp. 191–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsi, S.; Pinkard, N.; Woolsey, K. Creating equity spaces for digitally fluent kids. Commissioned Paper for the Exploratorium, San Francisco, CA, USA, 2005. Available online: https://annex.exploratorium.edu/research/digitalkids/Digital_equity_paper.pdf (accessed on 18 September 2025).

- Whitehead, L.; Talevski, J.; Fatehi, F.; Beauchamp, A. Barriers to and facilitators of digital health among culturally and linguistically diverse populations: Qualitative systematic review. J. Med. Internet Res. 2023, 25, e42719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ciolfi, L.; Avram, G.; Maye, L.; Dulake, N.; Marshall, M.T.; Dijk, D.V.; McDermott, F. Articulating co-design in museums: Reflections on two participatory processes. In Proceedings of the ACM Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work, CSCW, San Francisco, CA, USA, 27 February–2 March 2016; Volume 27, pp. 13–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dantec, C.A.L.; Fox, S. Strangers at the Gate: Gaining Access, Building Rapport, and Co-Constructing Community-Based Research. In Proceedings of the 18th ACM Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work & Social Computing, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 14–18 March 2015; Volume 2, pp. 1348–1358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vines, J.; Wright, P.C.; Silver, D.; Winchcombe, M.; Olivier, P. Authenticity, Relatability and Collaborative Approaches to Sharing Knowledge about Assistive Living Technology. In Proceedings of the 18th ACM Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work & Social Computing, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 14–18 March 2015; pp. 82–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cobb, C.; McCarthy, T.; Perkins, A.; Bharadwaj, A.; Comis, J.; Do, B.; Starbird, K. Designing for the deluge: Understanding & supporting the distributed, collaborative work of crisis volunteers. In Proceedings of the 17th ACM Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work, CSCW, Baltimore, MD, USA, 15–19 February 2014; pp. 888–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haesler, S.; Mogk, R.; Putz, F.; Logan, K.T.; Thiessen, N.; Kleinschnitger, K.; Baumgärtner, L.; Stroscher, J.P.; Reuter, C.; Knodt, M.; et al. Connected Self-Organized Citizens in Crises: An Interdisciplinary Resilience Concept for Neighborhoods. In Proceedings of the 2021 Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work and Social, Virtual Event USA, 23–27 October 2021; Volume 10, pp. 62–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bødker, S.; Iversen, O.S. Staging a Professional Participatory Design Practice; ACM Press: New York, NY, USA, 2002; Volume 31, p. 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.L.; Starbird, K.; Orand, M.; Stanek, S.A.; Pedersen, H.T. Connected Through Crisis. In Proceedings of the 18th ACM Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work & Social Computing, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 14–18 March 2015; Volume 2, pp. 969–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanders, E.B.N.; Stappers, P.J. Co-creation and the new landscapes of design. CoDesign 2008, 4, 5–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehn, P. Participation in Design Things; The MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2008; pp. 92–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asha, A.Z.; Smith, C.; Freeman, G.; Crump, S.; Somanath, S.; Oehlberg, L.; Sharlin, E. Co-Designing Interactions between Pedestrians in Wheelchairs and Autonomous Vehicles. In Proceedings of the DIS 2021—2021 ACM Designing Interactive Systems Conference: Nowhere and Everywhere, Virtual Event USA, 28 June–2 July 2021; pp. 339–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Westhuizen, D.; Conrad, N.; Douglas, T.S.; Mutsvangwa, T. Engaging Communities on Health Innovation: Experiences in Implementing Design Thinking. Int. Q. Community Health Educ. 2020, 41, 101–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrington, C.N.; Borgos-Rodriguez, K.; Piper, A.M. Engaging Low-Income African American Older Adults in Health Discussions through Community-based Design Workshops. In Proceedings of the 2019 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Glasgow, Scotland, UK, 4–9 May 2019; Volume 5, pp. 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrington, C.; Erete, S.; Piper, A.M. Deconstructing Community-Based Collaborative Design: Towards More Equitable Participatory Design Engagements. Proc. ACM Hum.-Comput. Interact. 2019, 3, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wardle, C.J.; Green, M.; Mburu, C.W.; Densmore, M. Exploring co-design with breastfeeding mothers. In Proceedings of the 2018 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems—Proceedings, Montreal, QC, Canada, 21 April–26 April 2018; pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erete, S.; Burrell, J.O. Empowered Participation: How Citizens Use Technology in Local Governance. In Proceedings of the 2017 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Denver, CO, USA, 6–11 May 2017; pp. 2307–2319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soden, R.; Palen, L. Informating Crisis. Proc. ACM on Hum.-Comput. Interact. 2018, 2, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semaan, B.; Mark, G. ‘Facebooking’ Towards Crisis Recovery and Beyond; ACM Press: New York, NY, USA, 2012; p. 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semaan, B.; Mark, G. Technology-mediated social arrangements to resolve breakdowns in infrastructure during ongoing disruption. ACM Trans. Comput.-Hum. Interact. 2011, 18, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olteanu, A.; Vieweg, S.; Castillo, C. What to Expect When the Unexpected Happens. In Proceedings of the 18th ACM Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work & Social Computing, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 14–18 March 2015; Volume 5, pp. 994–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarmiento, H.; Poblete, B. Crisis communication. In Proceedings of the 36th Annual ACM Symposium on Applied Computing, Virtual Event Republic of Korea, 22–26 March 2021; Volume 3, pp. 1711–1720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Compte, D.L.; Klug, D. “It’s Viral!”—A Study of the Behaviors, Practices, and Motivations of TikTok Users and Social Activism. In Proceedings of the 2021 Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work and Social Computing, Virtual Event USA, 23–27 October 2021; Volume 10, pp. 108–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dailey, D.; Starbird, K. Social Media Seamsters. In Proceedings of the 2017 ACM Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work and Social Computing, Portland, OR, USA, 25 February–1 March 2017; Volume 2, pp. 1277–1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orth, Z.; Andipatin, M.; Mukumbang, F.C.; van Wyk, B. Applying Qualitative Methods to Investigate Social Actions for Justice Using Social Media: Illustrations From Facebook. Soc. Media Soc. 2020, 6, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Given, L.M.; Forcier, E.; Rathi, D. Social media and community knowledge: An ideal partnership for non-profit organizations. Proc. Am. Soc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 2013, 50, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambton-Howard, D.; Anderson, R.; Montague, K.; Garbett, A.; Hazeldine, S.; Alvarez, C.; Sweeney, J.A.; Olivier, P.; Kharrufa, A.; Nappey, T. WhatFutures: Designing Large-Scale Engagements on WhatsApp. In Proceedings of the 2019 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Glasgow, Scotland, UK, 4–9 May 2019; Volume 5, pp. 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crivellaro, C.; Anderson, R.; Lambton-Howard, D.; Nappey, T.; Olivier, P.; Vlachokyriakos, V.; Wilson, A.; Wright, P. Infrastructuring Public Service Transformation. ACM Trans. Comput.-Hum. Interact. 2019, 26, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asad, M.; Le Dantec, C.A.; Nielsen, B.; Diedrick, K. Creating a sociotechnical API: Designing city-scale community engagement. In Proceedings of the 2017 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Denver, CO, USA, 6–11 May 2017; Volume 2017, pp. 2295–2306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCredie, J. Melbourne’s COVID-19 Second Wave Exposes Multicultural ”Data Hole”. Available online: https://insightplus.mja.com.au/2020/25/melbournes-covid-19-second-wave-exposes-multicultural-data-hole/ (accessed on 1 July 2025).

- Karp, P.; Minister Downplays Concerns Australia’s Covid Crisis Has Hit Multicultural Communities Harder. Guardian 28 Auguest 2020. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2020/aug/28/minister-downplays-concerns-australias-covid-crisis-has-hit-multicultural-communities-harder (accessed on 18 September 2025).

- ABC News. Victorian Government Rejects Ombudsman’s Call to Apologise to Public Housing Residents over Towers lockdown. 2020. Available online: https://www.abc.net.au/news/2020-12-17/lockdown-public-housing-towers-breached-human-rights-ombudsman/12991162 (accessed on 18 September 2025).

- Hayes, G.R. The relationship of action research to human-computer interaction. ACM Trans. Comput.-Hum. Interact. 2011, 18, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, R.E.; Briggs, J.; Armstrong, A.; MacDonald, A.; Vines, J.; Flynn, E.; Salt, K. Socio-materiality of trust: Co-design with a resource limited community organisation. CoDesign 2021, 17, 258–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potnis, D.; Adkins, D.; Cooke, N.; Babu, R. Addressing barriers to engaging with marginalized communities: Advancing research on information, communication and technologies for development (ICTD). Proc. Assoc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 2017, 54, 587–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brereton, M.; Roe, P.; Schroeter, R.; Hong, A.L. Beyond ethnography. In Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Toronto, ON, Canada, 26 April–1 May 2014; Volume 4, pp. 1183–1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research: Design and Methods; Sage Publications: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, C.; Shum, A.; Pearcey, S.; Skripkauskaite, S.; Patalay, P.; Waite, P. Young people’s mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet Child Adolesc. Health 2021, 5, 535–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.J.; Williams, S.; Eldridge, E.R.; Reinke, A.J. Digitally shaped ethnographic relationships during a global pandemic and beyond. Qual. Res. 2021, 23, 809–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heckmann, C.; What is a Story Beat in a Screenplay? Definition and Story Beat Examples. StudioBinder 2020. Available online: https://www.studiobinder.com/blog/story-beat-in-screenplay/ (accessed on 18 September 2025).

- Ghoshal, S.; Bruckman, A. The Role of Social Computing Technologies in Grassroots Movement Building. ACM Trans. Comput.-Hum. Interact. 2019, 26, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seguin, J.P.; Varghese, D.; Anwar, M.; Bartindale, T.; Olivier, P. Co-Designing Digital Platforms for Volunteer-Led Migrant Community Welfare Support. In Proceedings of the Designing Interactive Systems Conference, Virtual Event, Australia, 13–17 June 2022; pp. 247–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talhouk, R.; Balaam, M.; Toombs, A.L.; Garbett, A.; Akik, C.; Ghattas, H.; Araujo-Soares, V.; Ahmad, B.; Montague, K. Involving Syrian Refugees in Design Research. In Proceedings of the 2019 on Designing Interactive Systems Conference, San Diego, CA, USA, 23–28 June 2019; Volume 6, pp. 1583–1594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toombs, A.; Gross, S.; Bardzell, S.; Bardzell, J. From empathy to care: A feminist care ethics perspective on long-term researcher-participant relations. Interact. Comput. 2017, 29, 45–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akama, Y.; Pink, S.; Fergusson, A. Design + ethnography + futures: Surrendering in uncertainty. Conf. Hum. Factors Comput. Syst.-Proc. 2015, 18, 531–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haunschild, J.; Reuter, C. Bridging from Crisis to Everyday Life—An Analysis of User Reviews of the Warning App NINA and the COVID-19 Regulation Apps CoroBuddy and DarfIchDas. In Proceedings of the 2021 Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work and Social Computing, Virtual Event USA, 23–27 October 2021; Volume 10, pp. 72–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, D.L.; Koepfler, J.A.; Jaeger, P.T.; Bertot, J.C.; Viselli, T. Civic action brokering platforms. In Proceedings of the 17th ACM Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work & Social Computing, Baltimore, MD, USA, 15–19 February 2014; Volume 2, pp. 1308–1322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huybrechts, L.; Benesch, H.; Geib, J. Institutioning: Participatory Design, Co-Design and the public realm. CoDesign 2017, 13, 148–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, K. Examining the Digital Labor of Mental Health Communication on Social Media. In Proceedings of the 39th ACM International Conference on Design of Communication, Virtual Event USA, 12–14 October 2021; Volume 10, pp. 401–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopton, S.B.; Parry, R.M. Saving the sea, socially. Commun. Des. Q. 2017, 4, 32–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutwin, C.; Greenberg, S.; Blum, R.; Dyck, J.; Tee, K.; McEwan, G. Supporting Informal Collaboration in Shared-Workspace Groupware. J. Univers. Comput. Sci. 2008, 14, 1411–1434. [Google Scholar]

- Bødker, S. Using IT to ‘do good’ in communities? J. Community Inform. 2015, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steen, M. Co-Design as a Process of Joint Inquiry and Imagination. Des. Issues 2013, 29, 16–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dreessen, K.; Huybrechts, L.; Schoffelen, J. Generativity Revisited. Participatory Design for Self-Organization in Communities. Des. J. 2021, 24, 449–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dempsey, S.E. Critiquing Community Engagement; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2010; Volume 24, pp. 359–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heeks, R. Information systems and developing countries: Failure, success, and local improvisations. Inf. Soc. 2002, 18, 101–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dantec, C.A.L.; Edwards, W.K. The View from the Trenches: Organization, Power, and Technology at Two Nonprofit Homeless Outreach Centers; ACM Press: New York, NY, USA, 2008; p. 589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leavitt, A.; Robinson, J.J. The role of information visibility in network gatekeeping: Information aggregation on reddit during crisis events. In Proceedings of the ACM Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work, CSCW, Portland, OR, USA, 25 February–1 March 2017; pp. 1246–1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).