1. Introduction

Ontologies have become an integral component in various fields, including artificial intelligence, semantic web technologies, and information systems. They play a crucial role in establishing a common vocabulary and structure, enabling consistent and systematic knowledge modelling. Moreover, they provide a structured framework for organising information, facilitating human comprehension and automated processing, as well as enhancing interoperability across systems and knowledge domains. Nevertheless, when facing real-world scenarios, classical ontologies appear incapable of handling vague or imprecise information due to the absence of suitable semantic frameworks. This limitation poses a significant challenge when it comes to representing the degree of properties within the classical framework of Description Logic (DL). In order to handle this, the traditional definition was extended to fuzzy ontology by incorporating fuzzy logic, enabling degrees of membership for concepts and relations. Fuzzy logic, introduced by Lotfi Zadeh in 1965 [

1], extends classical logic by allowing truth values to range continuously between 0 and 1 instead of being strictly binary. A fundamental concept in fuzzy logic is that of a fuzzy set, where a membership function

assigns each element

a degree of membership, with the set

X being the universe of discourse. This approach effectively captures real-world vagueness in concepts such as “tall”, “hot”, or “expensive”, which lack precise boundaries. Fuzzy Description Logic (FDL) generalises classical DL by interpreting concepts as fuzzy sets and roles as fuzzy relations [

1,

2]. Unlike classical DL, where an individual either belongs to a concept or not, FDL allows graded membership [

3], and reasoning in FDL involves handling these membership degrees using fuzzy logic operations to combine and manipulate them effectively. Integrating fuzzy logic into DL requires a reconsideration of reasoning processes. In FDL, reasoning involves computing the degree to which axioms hold, rather than verifying binary truth values [

1,

4]. For instance, subsumption checking extends the classical concept inclusion problem by determining the extent to which one fuzzy concept subsumes another. Similarly, consistency checking must account for partial inconsistencies due to fuzzy assertions [

2,

5]. But if fuzzy ontologies provide a more flexible framework, is it possible to fuzzify already well-developed crisp ontologies? What is the optimal assignment of membership functions for each individual in each class? Furthermore, is it possible to merge fuzzy ontologies from different sources in order to reflect different evaluations of membership functions? The problem of fuzzifying ontologies, often closely related to that of merging heterogeneous knowledge structures, is not new and is well documented across various domains of application (see, e.g., [

6,

7]). These issues become especially significant when addressing uncertainty and vagueness in expert-based knowledge modelling. Moreover, ontology merging is a process that has been applied in a variety of contexts, including Judgment Aggregation (JA) [

8,

9,

10,

11]. This approach enables the integration of information from multiple ontologies, combining them into a single coherent ontology. The process is particularly useful in scenarios where knowledge from different sources needs to be unified, ensuring semantic consistency and enhancing the ability to analyse and infer from complex data [

12,

13,

14]. In the context of the aggregation of fuzzy ontologies, see [

15], F. Bobillo and U. Straccia amalgamate fuzzy ontologies with aggregation operators, thereby furnishing both a syntax and semantics for an FDL with fuzzy aggregation operators. Moreover, they provide a reasoning algorithm for a specific family of operators and demonstrate, through a series of examples, the utilisation of such aggregation operators, all within the Fuzzy OWL 2 language [

16]. On the other hand, in [

17], the authors present a tool (designated

Fudge) that aggregates fuzzy datatypes (which, in the terminology of Fuzzy OWL 2, are fuzzy membership functions for real-valued fuzzy sets) supported by the consensus of a group of experts.

In this paper, we aim to answer the questions above by using multi-criteria decision-making algorithms. Multi-Criteria Decision-Making (MCDM) techniques focus on selecting the best option from conflicting alternatives [

18,

19,

20]. MCDM is widely applied in management, engineering, economics, and environmental science, as it enables decision-making that balances competing objectives. MCDM is particularly useful when integrating qualitative and quantitative data under uncertainty, a scenario closely associated with fuzzy logic. Numerous studies have employed fuzzy-based techniques to address decision-making challenges [

21,

22,

23,

24]. When the decision problem involves more than one decision maker, the method falls within Multi-Criteria Group Decision-Making (MCGDM), which combines MCDM with group decision-making (GDM) [

25,

26,

27].

In our approach, which is different from what was performed in the related literature, we fuzzify crisp ontologies through an MCGDM framework that treats ontology classes as criteria and configurations as alternatives, enabling a principled assignment of fuzzy membership degrees. A finite panel of experts is considered, each assigned a fuzzy weight

reflecting their relative importance with respect to the decision problem. Each expert selects a preferred alternative, and a global geometric compromise

is computed via a minimal mean distance operator so that the consensus reflects the experts’ views while minimising deviations from individual alternatives. In addition to the works mentioned above, other studies analyse the integration of fuzzy ontologies through consensus-building. In particular, in [

28,

29], the authors consider two fuzzy ontologies containing two concepts and examine the resulting inconsistency. Informally, an inconsistency arises if there is a relation between two classes in both ontologies and whose membership functions differ. However, the way in which they achieve consensus and overcome this inconsistency does not involve MCGDM techniques. Furthermore, they do not address how to aggregate two different membership functions for the same concept of an individual. For these reasons, although our method tackles a problem already discussed in the literature, it does so in a slightly different way. Indeed, it introduces a novel technique that explicitly incorporates the opinions of multiple experts.

The paper is organised as follows.

Section 2 reviews ontologies and fuzzy ontologies, fuzzy numbers, t-norms and t-conorms, aggregation operators, defuzzification methods, and MCDM/MCGDM algorithms.

Section 3 introduces our MCGDM-based ontology fuzzification method, including the membership matrix, and defines an “overall best compromise” as the weighted mean of the experts’ optimal alternatives. Furthermore, we define the geometric compromise based on the minimal mean distance, ensuring that all expert opinions are incorporated while minimising deviation from each expert’s best alternatives.

Section 4 applies the model to fuzzify two crisp ontologies from BioPortal (

https://bioportal.bioontology.org), the largest repository of biomedical ontologies. Finally,

Section 5 summarises contributions and outlines future work. This article is a revised and expanded version of the conference paper [

30].

2. Preliminaries and Theoretical Background

In this section, we recall some basic concepts on ontologies, fuzzy ontologies, trapezoidal fuzzy numbers and operations between them, t-norms and t-conorms, aggregation operators that will be used throughout the paper, defuzzification methods, and some background on Multi-Criteria Decision-Making problems.

2.1. Ontologies and Fuzzy Ontologies

An ontology can be defined as a structured representation of knowledge, comprising concepts, properties, relations, and axioms, which makes it easier to use information by both humans and machines. It facilitates data integration, semantic research, system interoperability, and decision support.

Definition 1. An ontology can be described as a tuple:where is a set of m concepts (or classes) representing entities in a specific domain.

is a set of N individuals such that, for all , , for some .

is a set of c relations between the concepts (or the individuals I) such that, for all , , where ⊥ is false, and ⊤ is true in classic boolean logic.

Classical ontologies frequently prove inadequate in addressing vagueness, a shortcoming that is addressed by fuzzy ontologies. Fuzzy ontologies build upon the foundations of classical ontologies by incorporating the principles of fuzzy logic. In particular, rules and constraints of fuzzy logic define (using axioms) the elements of the ontology.

Definition 2. (cf. [

31]).

A fuzzy ontology can be defined as a generalisation of a classical ontology aswhere is a set of N individuals, also known as instances of concepts.

is a set of m concepts (or classes) representing entities in a specific domain. In particular, for all , is a fuzzy set on the domain of individuals, i.e., . The set of entities of the fuzzy ontology will be indicated by , i.e., .

is a set of c fuzzy relations on the domain of entities such that, for all , , with . A special role is held by the taxonomic relation , which identifies the fuzzy subsumption relation among the entities.

F is the set of fuzzy relations on the set of entities and a specific domain contained in . In detail, they are functions such that each element is a relation where , and .

A is the set of axioms expressed in a proper logical language, i.e., predicates that constrain the meaning of concepts, individuals, relationships, and functions.

The application of fuzzy ontologies allows for the representation of items with degrees of membership, rather than the binary classification typical of classical ontologies. For more details on these structures, we refer the reader to [

32,

33,

34].

2.2. Trapezoidal Fuzzy Numbers

A fuzzy number is a specific type of fuzzy subset within the set of real numbers

, characterised by additional defining properties (see, e.g., [

4,

35]). For these notions, we refer to the definitions and results used in the 1983 paper by P.J.M. van Laarhoven and W. Pedrycz [

36]. In this paper, we only consider trapezoidal fuzzy numbers defined as follows. However, as the reader will see later, the presented method is independent of the specific shape of the fuzzy numbers used. In such a case, the formulas (which make use of trapezoidal fuzzy numbers) presented in the remainder of the work would need to be revised accordingly.

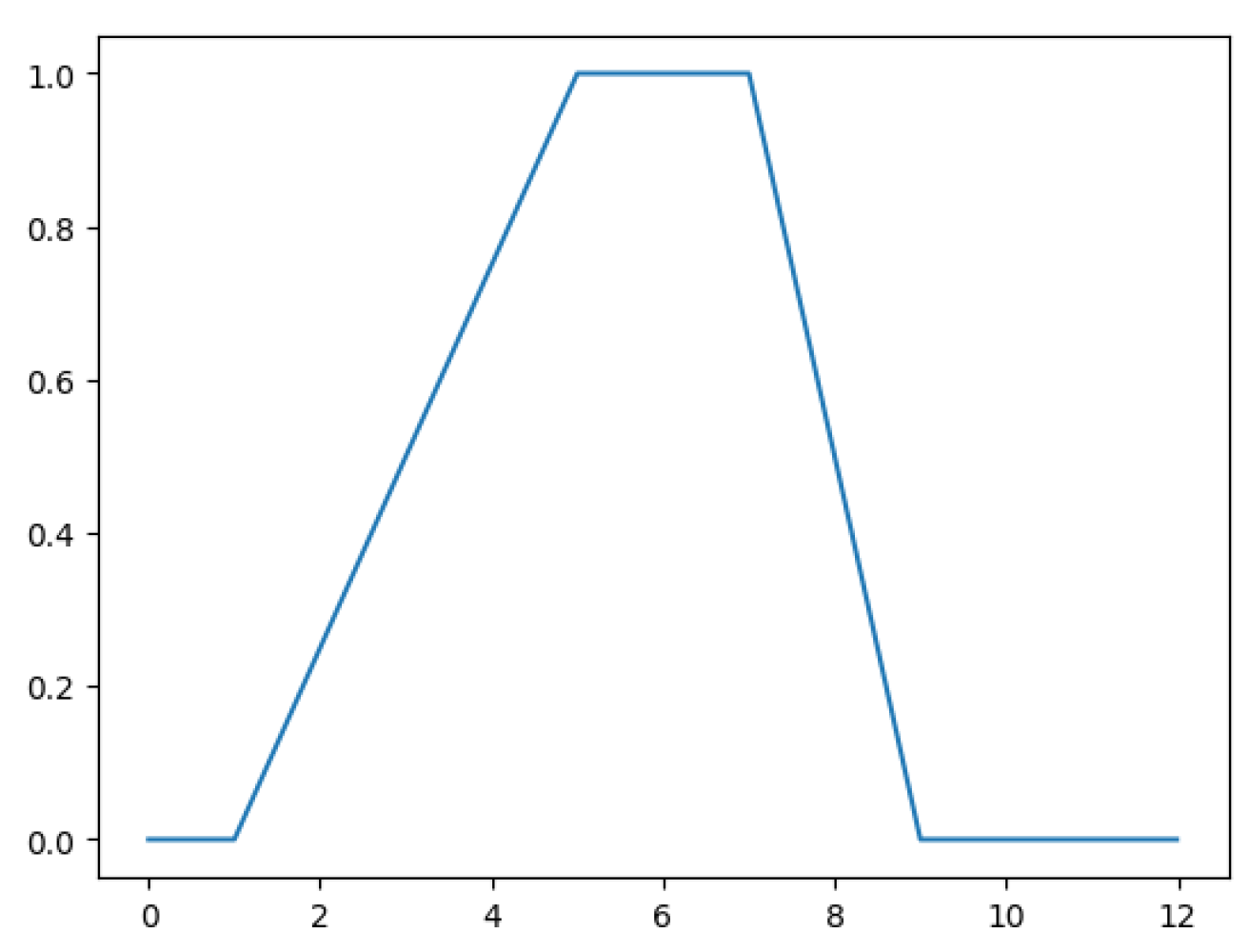

Definition 3. A trapezoidal fuzzy number (TpFN) , with and , is a fuzzy number whose membership function has a trapezoidal shape (as in Figure 1), i.e., for every , We denote with

the set of fuzzy subsets of the positive real numbers set

. The pseudo-arithmetic operations for such numbers, that are addition, multiplication, subtraction, and division [

37,

38] (see

Figure 2 for an example), are defined respectively as follows. For any pair

of TpFNs, with

,

Figure 1.

An example of a trapezoidal fuzzy number defined as .

Figure 1.

An example of a trapezoidal fuzzy number defined as .

2.3. Aggregator Operators

In this subsection, we recall some notions on aggregation operators. For the notation and definitions presented here, readers are referred to [

39] regarding the treatment of crisp operators, and to [

40] for fuzzy aggregator operators.

An aggregation operator is a function that takes an unknown number of inputs from a subinterval of , and returns an output within the same interval and satisfies certain conditions. Typically, to simplify notation and for the reader’s convenience, these contexts are restricted to the unit interval , that is . It is worth noting that, in our case, this operator fits perfectly, as we aggregate (matrices of) membership functions.

A basic example of an aggregation operator is the arithmetic mean

given by

The conditions that such a function has to satisfy are:

Boundary conditions: An aggregation operator

has to preserve the bounds of the domain and the range, i.e.,

To stress this condition when

, in the literature it is a convention to put

Monotonicity: It is the monotonicity of a function of

p variables, that is, the non-decreasingness of all partial operators, i.e.,

where we set

.

Therefore, we summarise the above with the following definition.

Definition 4. An operator is said to be an aggregation operator if it satisfies the boundary Conditions (5) and (6), and the monotonicity Condition (7). It is manifest that the arithmetic mean is an aggregation operator as defined in Definition 4. An aggregation operator may satisfy several properties beyond those of boundary conditions and monotonicity.

It may be necessary to introduce and integrate a weighting system for an aggregation operator (i.e., for an MCGDM). Let

be integer weights and let

be the corresponding non-zero weighting vector. For a given aggregation operator

, we can integrate weights

as follows:

As an example, if we integrate a weighting system for the arithmetic mean we obtain the well known weighted arithmetic mean (with rational weights), that is defined as , where .

2.4. Fuzzy Triangular Aggregator Operators

This paragraph is derived from [

40], in which U.F. Simo and H. Gwét propose a methodology for constructing fuzzy aggregator operators (i.e., aggregation operators that aggregate fuzzy numbers) by using t-norms and t-conorms. The notation will not be extensively revised as, similar to their referenced work, the considered fuzzy numbers will typically possess a trapezoidal shape.

Definition 5. (cf. [

41]).

A function is called t-norm if- 1.

- 2.

- 3.

- 4.

,

for any .

Definition 6. (cf. [

41]).

A function is called t-conorm if satisfies Conditions (1)–(3) of Definition 5 and, for any , In the field of logic, the distinction of three primary logics is typically made based on the properties of t-norms and t-conorms, as illustrated in

Table 1. These logics are Łukasiewicz, Gödel, and Product Logic [

4]. In contrast, Zadeh’s logic, characterised by the relations

and

, is entailed from Łukasiewicz logic.

It is noteworthy that Zadeh logic, while sharing with Gödel logic the same t-norm (for conjunction) and t-conorm (for disjunction), differs in its treatment of negation and implication.

Here we recall that, if

and

are two t-norms, with

we mean that

Analogously, if

and

are two t-conorms, with

we mean that

It is worth noting that the ordering of t-norms and t-conorms is preserved when their application is iterated over more than two elements.

Proposition 1. Let , and let and be two t-norms such that , and let and be two t-conorms such that . Thenand Proof. The proof is the same for both t-norms and t-conorms, since we rely on axiom 3, which is identical for both functions. Therefore, the proof for the t-conorm case will be omitted. We prove the result by induction on

p. For

, since

, we have

Now, suppose that the Inequality (

8) holds for

, and let us prove it for

p. Define

By axiom 3 of t-norms and the inductive hypothesis, we get

and since

, it follows that

Therefore,

completing the inductive step. □

Prior to the presentation of a fuzzy aggregation operator built on t-norms, it is necessary to elucidate the concept of the weighting vector associated with a t-conorm. In contrast to the approach outlined in [

40], this study proposes the use of fuzzy numbers as components of the weighting vector. In alignment with the recommendations provided by the authors, the fuzzy weighting vector will undergo normalisation with respect to a t-conorm as in the following definition.

Definition 7. Let ⊕

be a t-conorm. A vector , with , is called a fuzzy weighting vector associated with ⊕

if and only if the following equality is verified: The following lemma provides sufficient and necessary conditions for defining a fuzzy weighting vector associated with different t-conorms.

Lemma 1. Let ⊕ be a t-conorm and be a fuzzy vector, with .

- 1.

If , then Equation (10) holds if and only if - 2.

If , then Equation (10) holds if and only if there exist such that .

As an immediate consequence of the above lemma, we have the following corollaries.

Corollary 1. Let ⊕ be a t-conorm, and let be a fuzzy weighting vector associated with ⊕, where . Then, is also a weighting vector for .

Corollary 2. Let ⊕

be a t-conorm, and be a fuzzy vector, with . If there exist such that , then Equation (10) holds for all . Moreover, in this case, For

, we observe that in order to obtain a normalised vector in the sense of Lemma 1, it is sufficient to divide each component of the trapezoidal fuzzy number by the addition between the first component of the fuzzy weights. In particular, let

be a vector of fuzzy weights, where

. Then, the

i-th component of the normalised vector of fuzzy weights is

As an example of fuzzy triangular aggregation operators, we slightly modify the definition of fuzzy triangular weighted arithmetic operator (FTWA) given in [

40] by considering a fuzzy weighting vector

and applying the operator on crisp numbers.

Definition 8. Let ⊗

be a t-norm, ⊕

a t-conorm, and a fuzzy weighting vector associated with ⊕. The fuzzy triangular weighted arithmetic operator is the map , such thatwhere and , for all . This operator will be used throughout this paper.

2.5. Defuzzification Methods

A defuzzification method can be thought of as a process of selecting an element x from the universe of discourse X, based on the value of its membership degree . This process can therefore be expressed through a defuzzification operator D that maps (the value of) a membership function to an element of X: .

There are several ways to choose a defuzzification operator, depending on the criteria and constraints that these operators must satisfy [

42,

43]. In the context of decision support systems, the most prevalent defuzzification operator is the Mean of Maxima (MOM). The following concise overview is provided on the latter operator within the context of the set of real numbers.

If

is a fuzzy set, then

is defined as follows

where

, with

. In our context, the fuzzy set

has a trapezoidal shape, namely

. Thus,

M is clearly the closed interval

and by Equation (

13) it follows

Remark 1. We observe that the operator defined in Definition 7 is not formally an aggregator. Nevertheless, when we apply a defuzzification method, e.g., MOM, the composition falls into the classical definition of an aggregation operator.

2.6. Multi-Criteria Decision Making and Multi-Criteria Group Decision Making

In the general context of decision-making, a prominent branch is given by Multi-Criteria Decision-Making (MCDM) that focuses on comparing several feasible courses of action and identifying the one that best aligns with predefined goals, objectives, values, and priorities. These kind of problems specifies a set of n alternatives and a set of m criteria . In this setting, alternatives denote the available choices of action, whereas decision criteria—also called goals or attributes—define the dimensions along which the alternatives are evaluated. For each a score is assigned, indicating how well satisfies criterion . The primary aim of MCDM is to determine the optimal alternative , namely the option with the highest overall desirability with respect to the chosen criteria.

MCDM methods also introduce a weight

for each criterion

to reflect its relative importance in the decision process, typically normalised so that

. These weights may capture the preferences of a single decision maker or represent a consensus formed by a panel of experts, and there exists extensive literature on procedures for weight assignment and elicitation (see, e.g., [

44]). Beyond selecting

, the MCDM framework commonly produces a final rank

for every alternative

,

, summarising each option’s overall desirability or relevance within the decision problem context. Such rankings are essential for prioritising the alternatives and guiding the decision maker towards the most suitable choice.

The relationship between alternatives and criteria is frequently organised into a decision matrix, whose rows correspond to the alternatives and columns to the criteria . This matrix provides a compact representation of the evaluations and serves as the foundation for applying MCDM techniques to aggregate performances and weights into overall rankings and final recommendations.

As an example, we show the so-called Weighted Sum Method (WSM), one of the most classical methods in MCDM. Formally, let

for each

. The alternatives

are ranked in descending order based on their final ranking values

, with the optimal alternative

being the one that achieves the highest ranking value, i.e.,

In case a group of decision makers is involved in the decision problem with the goal of selecting the most suitable alternative from a finite set of alternatives under multiple criteria, we move in the framework of Multi-Criteria Group Decision-Making (MCGDM). In this context, the difficulty of understanding how to join, incorporate, or appropriately consider the various opinions to reach a consensus among them is added.

In fact, there is extensive literature on various methods for assigning weights to experts in such settings (see, e.g., [

44]), reflecting the importance of this step in reaching reliable group decisions.

In particular, several studies focus on automatic or data-driven methods to determine these weights based on criteria such as consistency, consensus, or the maximisation of deviation among expert opinions [

45,

46,

47,

48], reducing subjectivity and improving the reliability of aggregated judgments.

In addition to automatic methods, other works address the problem of how to qualitatively assess and weight experts according to their experience, expertise, and domain knowledge. For example, methods based on maximising the deviation of expert opinions [

49] or on consistency and consensus metrics [

50] have been proposed.

In this paper, we consider a domain expert (a meta-expert) who will assign weights to the involved experts based on their experience in terms of years, skills, and competencies, thereby relying on qualitative judgment rather than automated weighting.

3. Model and Mathematical Aspects

In this section, we first present the notation used throughout this work, and we analyse more technical mathematical details and necessary assumptions. Then, we present the algorithm in which we integrate ontologies in the MCGDM setting.

We begin by introducing the concept of a membership matrix.

Definition 9. Let be a fuzzy ontology with classes , with and let be the set of individuals, with . Given a membership function μ, we define the membership matrix, where is the value of the membership function on the individual with respect to the class .

Let be the set of experts, the set of alternatives and the set of criteria. In our context, given a set of membership functions defined on , the criteria and alternatives will be interpreted as follows:

the criteria , for , are the classes of ;

the alternatives , for , are the membership matrices related to , i.e , where .

For each expert

, with

, we build a decision matrix based on the alternatives and the criteria available, as illustrated in

Table 2. The components of these matrices are the scores

that each expert

assigns to the alternative

with respect to the criterion

, for all

, and

.

Furthermore, each expert assigns a weight to the class (i.e., the criterion) . These weights represent the relative importance of the class for the expert with respect to (the ontology involved in) the decision problem. For each expert, we assume the family of weights to be normalised and we place them in what we call weighting matrix, denoted as .

Then we have the

matrices, for

,

Usually, the score in the decision matrix indicates how well, for the expert , the alternative satisfies that specific criterion . In our case, the expert assigns the score to the j-th column of the membership matrix , i.e., the expert evaluates how the alternative fulfils (the ontology involved in) the decision problem for the class .

In the following remark, we highlight that it is possible to extend our method to every entity of an ontology.

Remark 2. Note that it is possible to extend our method to the relations between the entities of a fuzzy ontology, by defining the decision matrix as illustrated in Table 3. In this case, the alternatives are defined as the matrix , where is the value of the i-th membership function of the relation defined as , with , , for all , and . Precisely, represents the entities fulfils the relation. In order to make our method as general as possible, we assume that the weights and scores are TpFNs, thus

, where

Once a t-conorm ⊕ has been chosen, we can, by Lemma 1, assume w.l.o.g. that the fuzzy vectors of fuzzy weights

are weighting vectors with respect to the t-conorm ⊕ in the sense of Definition 7. Subsequently, we construct the

p decision matrices, one for each expert, as in

Table 2.

Each expert computes their optimal alternative based on the MCDM method they have chosen to solve the decision problem. We denote with

the function that each expert

chose to compute final ranks

, associated with its MCDM, and with

the set

. This function depends on the weighting vector

and the decision matrix

. Then

and

Henceforth, each expert calculates the final rank value with respect to the alternative . Note that the final rank value is a fuzzy number. Subsequently, in order to obtain a crisp rank, for each expert, a defuzzification method is applied. That is, we denote by the set , where , so that , for any , is the defuzzified rank of alternative for expert .

Thereafter, we may use the defuzzied ranks to identify the optimal alternative

, with

and

, relative to the expert

in the classical way, namely

Finally, to compute the matrix of the best compromise , we need to choose a t-norm and a fuzzy aggregator . With an abuse of notation, we say that we apply the aggregator to the tuple of matrices , meaning that is applied component-wise, i.e., .

Additionally, a weighting vector

associated to ⊕ is introduced. Every

is the fuzzy weight of the expert

in the final aggregation process. Then

is a weighted fuzzy aggregator with respect to

. In this way, we can aggregate

p matrices whose entries are trapezoidal fuzzy numbers in

, then

and the aggregated matrix can be written as

, with

and

, where

In order to finally obtain the best compromise matrix

, we have to apply element-wise a defuzzification operator

to the matrix

, i.e.,

We conclude this section by proving that is still a membership matrix, thereby ensuring the mathematical consistency of our method.

Proposition 2. The best compromise is a membership matrix.

Proof. In order to prove that

is still a membership matrix, we show that its entries are always values in

. Since the fuzzy operator

returns value in

and the defuzzification operator

D returns value in

, thus we have

□

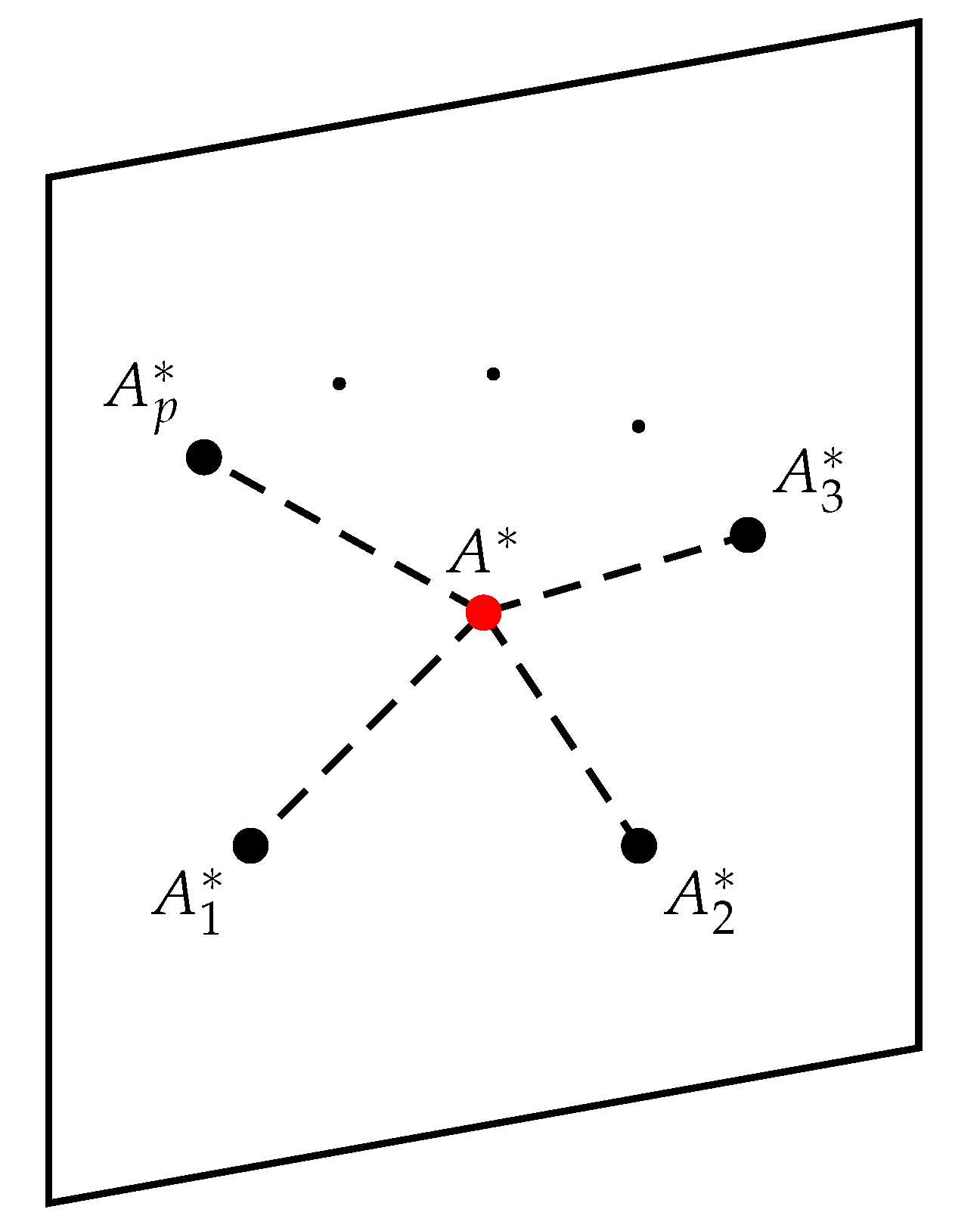

Geometric Compromise

In order to reach the optimal overall compromise, we propose to minimise the mean of distances. For this reason, we will refer to this consensus as geometric compromise.

Since experts weights

are fuzzy, we aggregate the experts’ alternatives

, with

, into a global compromise

using a suitable fuzzy triangular aggregation operator (see [

40])

, so that

Given that membership matrices are in

, where

and

, the Euclidean distance between

and

is as follows:

Here, the subscript

indicates that

is obtained through the aggregation operator

. We define the mean distance

which depends on the choice of

in Equation (

19). Our aim is to select

so that it reflects the collective views of all experts

while remaining as close as possible to each

in

(see

Figure 3). This prevents bias towards any single expert and ensures a balanced compromise. Formally, we choose

to minimise the mean distance:

where

denotes the set of fuzzy triangular weighted operators on

with respect to

. In order to guarantee the existence of a minimum, we can restrict attention to a finite family

and rewrite Equation (

21) as follows:

If multiple operators achieve the same minimum, any of them may be chosen, possibly using secondary criteria such as computational efficiency.

Definition 10. A geometric compromise is the aggregated matrix , where is a minimal mean distance operator from a given family of fuzzy triangular weighted operators.

A natural choice for

could be including the fuzzy triangular versions of the weighted arithmetic and geometric means, which are, respectively,

(see Equation (

12)) and

, which is defined as follows:

Thus, the entries of the overall best compromise matrix

in these two cases are computed as, respectively:

and

It is worth noting that the best compromise is not necessarily one of the initial , with . We point this out in the following remark, with which we conclude this section.

Remark 3. This algorithm is well-suited for MCDM problems where the final choice can fall outside the set of predefined alternatives. For instance, a company may use MCGDM to determine the optimal office temperature that balances employee comfort, energy efficiency, and health considerations. In this case, the final decision could be any temperature within a reasonable range, rather than being limited to a predefined set of options.

However, this approach can also be used for MCGDM problems where the final choice must strictly be one of the given alternatives. A clear example is selecting a site for a long-term nuclear waste storage facility. Unlike office temperature, where intermediate values are valid, the best location cannot be an arbitrary compromise between sites. For example, choosing a different location might place the site in an unstable geological area or too close to a population centre. In cases like this, if we want the final output to be one of the initial alternatives, the best choice is chosen to be the closest option to the minimal mean distance compromise.

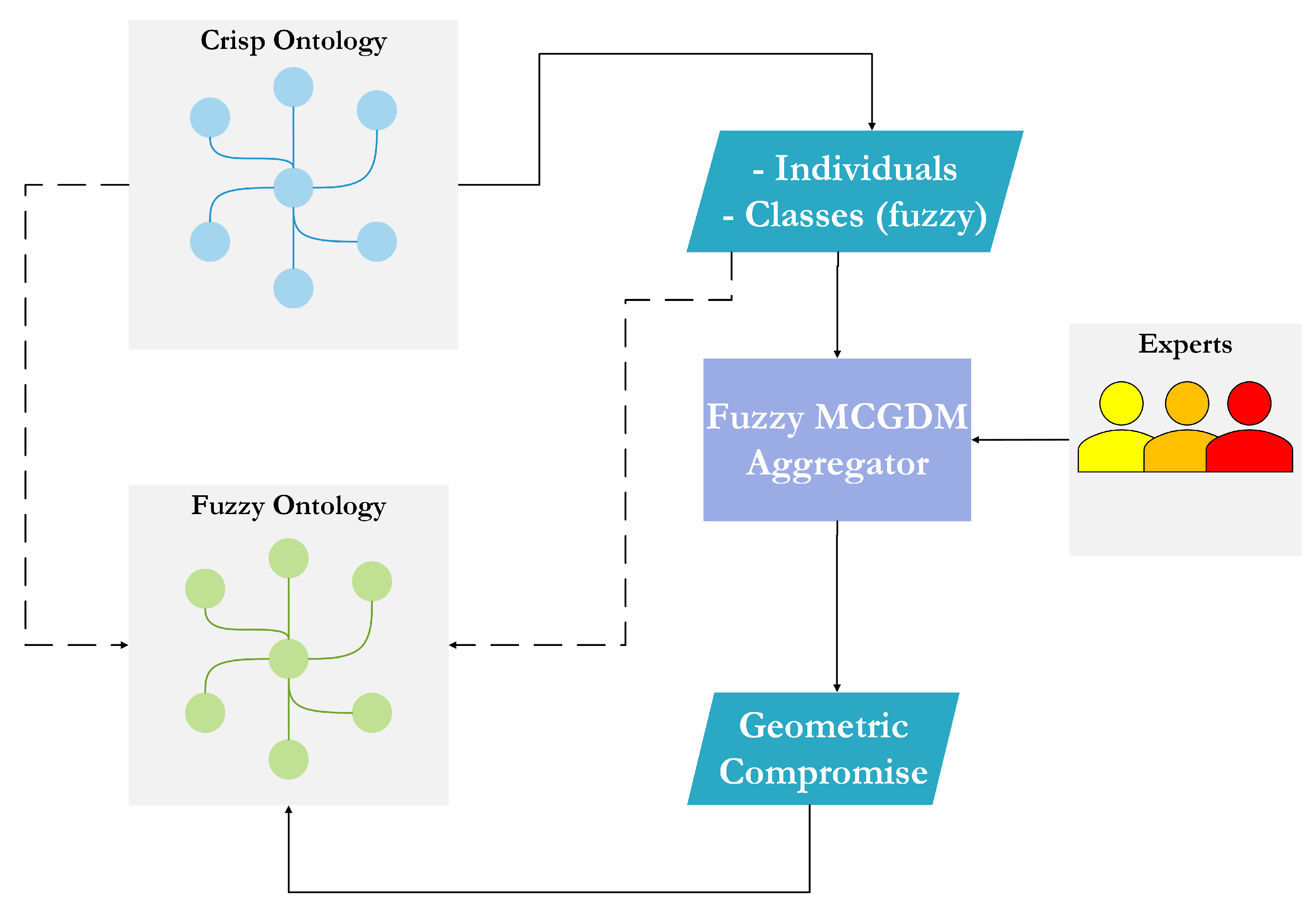

As illustrated in

Figure 4, the reader can finally observe the flowchart of our algorithm. Moreover, in

Figure 5, we give a simple graphical representation of the principal steps involved in our process applied to the particular case of fuzzification of crisp ontologies.

4. Applications

In this section, we analyse possible applications of the algorithm presented in the previous section. Moreover, to put theory into practice, we propose two examples in order to better clarify how the algorithm presented in the previous sections works. More precisely, in

Section 4.1, we fuzzify the Cognitive Task Ontology (CogiTO) by considering classes already present in the ontology, while in

Section 4.2, we fuzzify the BrainTeaser Ontology (BTO) by adding new fuzzy classes.

As already mentioned, despite the greater flexibility of fuzzy ontologies, their applicability is currently limited by the lack of well-done (and public) ones. To achieve this, in the following remark, we observe that, starting from a crisp ontology, it is possible to fuzzify it using the algorithm presented in

Section 3.

Remark 4. By exploiting the algorithm in Figure 4, it is possible to fuzzify a crisp ontology by adding new fuzzy classes to the starting ontology. The challenge here is to coherently assign the membership degrees to the individuals in these new classes. A possibility is to get the opinion of either domain experts or survey a sample of users in order to infer appropriate membership degrees (see Section 4.2). It is worth noting that our approach can also be applied to merge the solutions of multiple decision-making problems, as is pointed out in the following remark.

Remark 5. Since an ontology is a structured representation of knowledge, it is reasonable to assume that it can be used to solve multiple decision problems. For instance, an ontology on geo-thematic topics may be used to deal with the following decision problems:

What are the optimal countries for commercialisation purposes?

For a given state, which neighbouring state has the highest employment rate?

In particular, we may consider the alternative as the membership assignment given by an expert with respect to the decision problem . Hence, given these alternatives as input, our approach computes the best compromise to build or update the membership assignment of the individuals of a fuzzy ontology with respect to multiple decision problems.

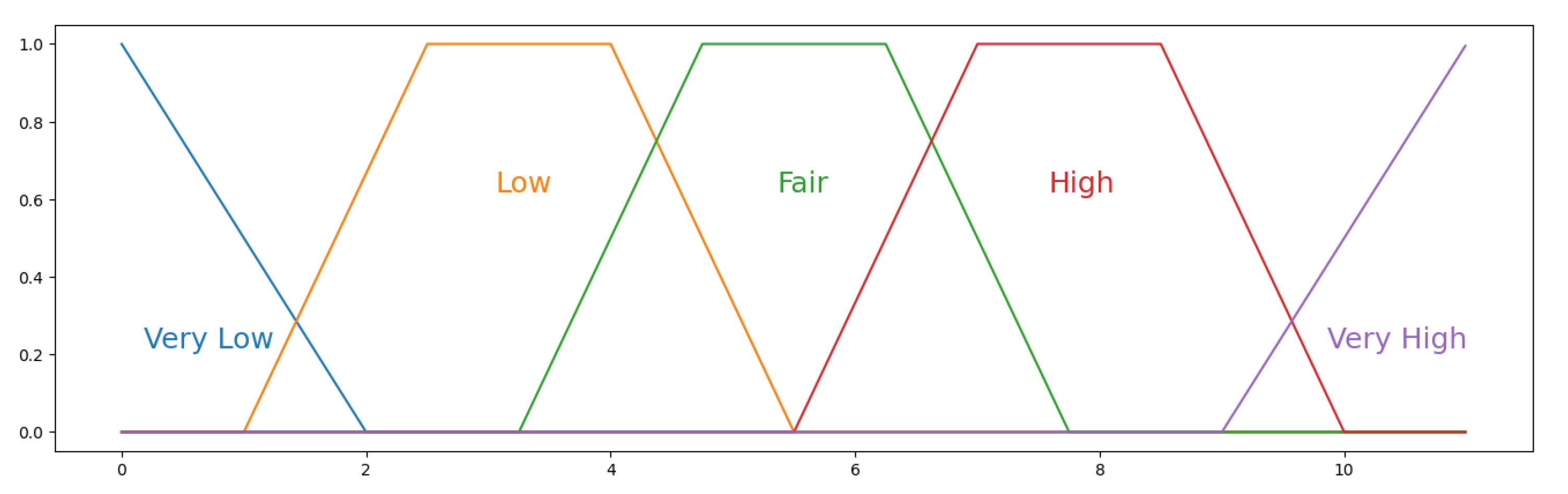

In the following, for each expert

the weights

assigned to the classes in

, are expressed through qualitative degrees such as “Very Low”, “Low”, “Fair”, “High”, “Very High”. Similarly, the scores

are described through “Very Poor”, “Poor”, “Fair”, “Good”, “Very Good”. These qualitative degrees are subsequently translated in terms of TpFNs according to

Table 4 (see also

Figure 6). In order to simplify our approach, we underline that we consider the same pairwise TpFNs for weights and scores. However, it is always possible to define different TpFNs of weights and scores. Note that, in the examples, in order to avoid a new potentially complex notation, we report the expert weights in the tables with the same labels indicated in

Table 4. We recall that the fuzzy weights selected by each

have to be normalised according to Lemma 1 following Equation (

11).

As explained in the

Section 3, the algorithm enables each expert

to select their own MCDM,

, and defuzzification operator,

. For simplicity, we assume that each of them uses a Simple Additive Weightage (SAW), but the weights and scores are TpFNs. Hence we have

Additionally, every defuzzification operator, denoted as

D, coincides with the MOM operator (see Equations (

13) and (

14)). More precisely, by Equation (

26) we have

and the crisp rank is found as

In the examples, we will use the fuzzy triangular aggregation operator, i.e., the operator

, which is the one defined by Equation (

12). Hence, by Equation (

24), we have

and the best compromise matrix

is finally determined by the formula

When we use the fuzzy weighted geometric mean

(Equation (

25)), we explicitly obtain

and the best compromise matrix

is given by

In the following remark, we observe that, in our case, the fuzzy weighted geometric mean requires reversing the order of the components of the TpFNs.

Remark 6. We recall that, within the fuzzy weighted geometric mean, since all components of the TpFNs lie in , the map is monotonically nonincreasing on for any fixed base . Consequently, exponentiation by a trapezoidal weight reverses the component order. Therefore, for and , we obtain When it is necessary to emphasise the specific t-norm or t-conorm employed in the computation, the notation will be used. Similarly, we use the notation when it is necessary to emphasise the specific t-norm employed in the computation of the fuzzy weighted geometric mean.

In [

40], the authors prove that the fuzzy aggregators based on the t-norms and t-conorms they introduced satisfy the fundamental axioms of aggregation operators (see

Section 2), focusing especially on properties such as monotonicity with respect to the aggregated quantities. In this work, we extend their analysis by proving an additional form of monotonicity: we show that for the aggregators considered here (namely,

and

), the ordering between different t-norms is preserved in the aggregated value once the t-conorm is fixed, and similarly, the ordering between different t-conorms is preserved once the t-norm is fixed.

Proposition 3. Let be an aggregation operator.

If , then for every fixed t-conorm ⊕.

If , then for every fixed t-norm ⊗.

Proof. Let

, let ⊕ be a fixed t-conorm, and let

be two t-norms. Under these assumptions, for every

and

, we have

and

. By applying Axiom 3 for t-conorms iteratively p times, it follows that

Since the same inequalities hold for the terms

, and given that the MOM involves only addition and multiplication of real numbers, we conclude that

, that is,

. Now, let ⊗ be a fixed t-norm, and let

be two t-conorms. By Proposition 1, and in particular by Inequality

9, we have

andUsing the same reasoning applied to MOM, we conclude that .

Let

. In this case, no t-conorms are involved in the computation (see Equations (

28) and (

29)). Let

be two t-norms. By Proposition 1, and in particular Inequality

8, we obtain

Therefore, also in this case, we conclude that , that is, □

For the sake of the reader’s convenience and to facilitate experimentation, the following examples show the entries of the alternatives as linguistic variables, with the value assignment given in

Table 5. Moreover, we show the aggregation results using both the fuzzy weighted arithmetic and geometric mean.

In the following remark, we highlight the reason related to our practical normalisation of the fuzzy weights and .

Remark 7. As highlighted in Corollary 2, for a set of vectors to be normalised with respect to the t-conorms taken into account, it suffices that there exists a fuzzy number whose components are all equal to 1. From an applied perspective, however, the presence of such a fuzzy number within the set of vectors is of limited practical significance. In the case of the fuzzy weighting vectors , this would correspond to the existence of an “oracle” expert who possesses complete and perfect knowledge. Conversely, in the case of the weights , it would imply the existence of a class within the ontology that is deemed to be of absolute importance by every expert.

One way to circumvent this issue is to introduce a fictitious expert with weight , as well as a class of exact importance with a corresponding weight . With regard to the class, a further consideration is required: in order for this class not to exert any influence on the final aggregation, the experts must assign to its scores the TpFN . In other words, they have to indicate that the corresponding column across the alternatives is exact.

We therefore assume that, in this context, each alternative is extended with an additional column corresponding to this class of exact importance, and that the membership degree of each alternative to this class is given by 1. One conceptual means of arriving at this conclusion is to consider one of the classes between U and ∅, where U denotes the universal class. For instance, in the OWL standard, these are represented respectively by the classes Thing and Nothing. Assuming the choice of the Thing class, each alternative may be extended with a column referring to Thing, and each individual may be assessed as having a membership degree of 1 with respect to this class.

Similarly, in order to render the “oracle” expert inconsequential, one might have this expert assign the score (1, 1, 1, 1) throughout its entire decision matrix.

Given that neither the “oracle” expert nor the Thing class nor the associated weight has any influence on the calculations, they may be safely excluded from the actual implementation.

From an applicative point of view, therefore, following the notion of normalisation outlined in Corollary 2, it is sufficient to require that the fuzzy weighting vectors are normalised solely with respect to the Łukasiewicz t-conorm. For the other two t-conorms, normalisation may be achieved via the theoretical precautions described above, without any modification to the implementation itself. Finally, since these weights do not contribute to the computation of the geometric compromise, we also ignore them in the calculation of the fuzzy rank of the alternatives in Equation (26). 4.1. Fuzzification of Cognitive Task Ontology (CogiTO)

In this example, we consider the Cognitive Task Ontology (CogiTO) (

https://bioportal.bioontology.org/ontologies/COGITO, accessed on 28 July 2025), which relates Tasks from Cognitive Atlas to Hierarchical Event Descriptor (HED) tags via logical relationships (as equivalent class axioms) between concepts. This could be a semantic basis for fuzzy sentimental analysis (see [

51] for a review on this topic).

In particular, we select a few classes and individuals for the fuzzification process. Specifically, we select five individuals

,

,

,

and

, five classes

,

,

,

and

, and three experts

, for

. For this applicative example, we choose to model the degree of an individual’s emotional state with the classes

(sub-classes of the class “Agent-emotional-state”.) in

Table 6. Moreover, the individuals represent participants who have been exposed to some emotional stimulus.

Suppose we have the following three alternatives

,

and

, given as follows:

where every entry of the matrices is a linguistic variable in

Table 5, which represents the membership degree of the individual

with respect to the corresponding class

.

For the sake of transparency and reproducibility, please refer to Equation (

30) for the numerical values employed for each alternative.

Each expert

, taking into account the decision problem, assigns weights (normalised according to Equation (

11))

,

,

,

, and

to the classes, then evaluates the above alternatives and gives their respective decision matrix. In particular, the decision matrices for

are given in

Table 7.

First, for each expert, we compute the final ranks by using Equation (

16), and we get their optimal alternative by using Equation (

17). In particular, we get the following optimal alternatives:

Furthermore, we assume the following normalised family of fuzzy weighting vectors (normalised with respect to the Łukasiewicz t-conorm as highlighted in Remark 7):

The most optimal consensus among the three experts is now computed by employing the Equation (

27) using the fuzzy weighted arithmetic mean aggregator

(see Equation (

12)):

In particular, for any pair of ⊗ and ⊕, with

and

, we get the following geometric compromises (see

Section 3) with linguistic variables in

Table 5:

Remark 8. We observe that the order of the t-norms and t-conorms is preserved. Since ([52], sec. Fuzzy Intersections: t-Norms, p. 63) and ([52], sec. Fuzzy Unions: t-conorms, p. 78), for all and , we have that

Next, we compute the Euclidean distances between each

and each

as in Equation (

20):

Finally, we compute all the mean distances

and we have the following results:

Therefore, in this particular context, using the fuzzy weighted arithmetic mean aggregator, the geometric compromise that has minimal mean distance is that computed using

and

, whose numerical matrix is as follows:

Now, we aggregate the optimal compromises using the fuzzy weighted geometric mean

:

In this case, we get the following three geometric compromises with linguistic variables in

Table 5:

As before, we compute all the mean distances

:

We observe that, using the weighted geometric mean, the most optimal compromise is that obtained using

, whose membership matrix is

4.2. Fuzzification of BrainTeaser Ontology (BTO)

In particular, since the ontology under consideration is very large, we determine a few classes to fuzzify and select some individuals for the ontology fuzzification process. Specifically, we choose ten individuals, seven classes, and five experts

, for

. For this applicative example, we model the degree of disease disorder by fuzzifying the classes

, and by selecting the individuals

in

Table 8, respectively.

Suppose we have the following three alternatives

,

and

, given as follows:

where every entry of the matrices is a linguistic variable as in

Table 5, which represents the membership degree of the individual

with respect to the corresponding class

.

For the sake of transparency and reproducibility, please refer to Equation (

31) for the numerical values employed for each alternative.

As in the previous example, each expert

, taking into account the decision problem, assigns weights

to the classes (normalised according to Remark 7), then evaluates the above alternatives and gives their respective decision matrix. In particular, the decision matrices for each expert

are given in

Table 9.

For each expert, we compute the final ranks by using Equation (

16), and we get their optimal alternative by using Equation (

17). In particular, we get the following optimal alternatives:

Furthermore, we have the following normalised family of fuzzy weighting vectors selected by an external expert (normalised with respect to the Łukasiewicz t-conorm as highlighted in Remark 7):

The geometric compromise among the experts is computed by employing the Equation (

27), using the fuzzy weighted arithmetic mean aggregator

, and the fuzzy weighted geometric mean aggregator

.

In particular, we compute all the mean distances

:

and the mean distances

:

Hence, we have that the most optimal consensus among the experts is given by

for the aggregator

and

for the aggregator

, whose matrices are as follows:

In the following remark, we observe some computational differences between the use of the fuzzy weighted arithmetic and geometric mean aggregators.

Remark 9. From a computational standpoint, is the preferred aggregator. This is due to the fact that requires only t-norms. Indeed, as the number of alternatives and the number of experts increase, the number of operations needed by is less than that needed by . The latter, indeed, requires the calculation of nine different aggregate compromises since we use three t-norms and three t-conorms. Nevertheless, the minimum attained by can be smaller than that of as in Section 4.1 and in Section 4.2, where and , respectively. In the following remark, we observe some limitations of these experiments.

Remark 10. A caveat concerning Section 4.1 and 4.2 is the reliance on linguistic variables to encode the alternative matrices. From an elicitation standpoint, this is appropriate—domain experts must judge alternatives in cognitively meaningful terms. The main goal of this study, however, is to construct a fuzzy ontology by computing an optimal consensus of the fuzzy membership degrees of individuals to fuzzy concepts. Consequently, the algorithm operates strictly over real-valued memberships in the unit interval [0, 1]. This design choice, while methodologically convenient, burdens interpretation for experts unfamiliar with fuzzy set theory: the quantitative semantics underlying a given linguistic label are not directly visible. For example, throughout our illustrations, we identify every membership degree in [0, 1/5] with the linguistic term “Very Low”; yet two assessments both labelled “Very Low”—say 0.14 vs. 0.05—remain indistinguishable to the expert despite their non-trivial numerical disparity. 5. Conclusions and Future Works

Building on the integration of fuzzy logic into MCDM, as discussed in [

53], and its application in ontologies [

32], we introduced a novel framework for applying MCGDM to fuzzy ontologies, which we refer to as Fuzzy Value-Aggregation for Semantic Preference Unification.

Our approach considers a crisp ontology with a set of m classes and formulates an MCGDM problem with a group of p experts and a set of n alternatives . In this work, the decision criteria correspond to the ontology’s classes. Each alternative represents a membership matrix, where an entry denotes the membership degree of an individual with respect to the class . Alternatively, it may represent the membership value of relations between entities in the ontology , as mentioned in Remark 2.

In our proposed methodology, each expert constructs a decision matrix by assigning a fuzzy score to the membership values in column j of , reflecting the membership values of individuals in class within that configuration. Additionally, experts assign fuzzy weights to each class , representing its relative importance in the decision-making process. With a fixed t-conorm, the fuzzy weight vectors serve as weighting vectors as in Definition 7. Each expert computes a final fuzzy ranking value for each alternative . These values are then defuzzified using a chosen defuzzification method (in our case, we choose the MOM defuzzification method), converting them into their corresponding crisp ranking values . The optimal alternative for each expert, denoted as , is determined by selecting the alternative with the highest ranking values with respect to the expert.

In order to integrate the individual expert evaluations, a weighting vector is introduced, where each represents the fuzzy weight of the expert . Using a fuzzy aggregation function , we compute the geometric compromise , aggregating the expert-specific matrices composed of trapezoidal fuzzy numbers. Finally, a defuzzification operator is applied to convert the aggregated matrix into a membership matrix. This process ensures a systematic and flexible method for integrating expert opinions in fuzzy ontology-based decision-making.

Additionally, as highlighted in Remark 5, our approach enables the computation of membership assignments that achieve an optimal balance across multiple decision problems within a fuzzy ontology.

In

Section 4, we used two crisp ontologies from the BioPortal website to test our approach.

As the use of ontologies, particularly fuzzy ontologies, continues to grow, it is likely that different ontologies will increasingly share common domains, classes, and individuals. This makes ontology aggregation a relevant and practical challenge. Moreover, as highlighted in the example presented in

Section 4, the choice of t-norms and t-conorms in the fuzzy aggregation process can significantly influence the final aggregation. Therefore, selecting an appropriate t-norm and t-conorm should be performed carefully, ensuring coherence with the specific ontology being considered.

Future works could be related to the use of different aggregation operators in order to find the best compromise .

An important direction for future research is the use of conditional probabilities to construct membership functions, which represents a gap in our current approach. Our primary challenge is not the aggregation of numerous existing ontologies, as such ontologies are not yet widely available in the literature. Instead, our focus is more theoretical: determining the most appropriate function to assign membership degrees. For instance, given an economic indicator such as Gross Domestic Product (GDP), how can we define a function that accurately represents how wealthy a country is? A probabilistic approach could provide a foundation for defining membership functions based on empirical data. One possibility is to collect responses from a sample group and analyse how to derive membership degrees from their assessments. However, this does not necessarily mean that if of respondents classify a country as “rich”, its membership degree should be . An alternative approach could involve consulting domain experts to determine not only their assessments but also the reasoning behind their function construction. Exploring these methodologies could lead to more robust and interpretable fuzzy membership functions, thereby improving ontology modelling in uncertain domains.

Moreover, we plan to apply the proposed methodology to fuzzify the ontology currently under development within the Sustainability Decision Framework (SDF) project—a joint initiative of the Dipartimento di Matematica e Informatica (DMI) at the Università degli Studi di Palermo (UniPa), in collaboration with the industrial partner TD Group Italia SRL. The project’s objective is to design an Explainable Artificial Intelligence (XAI) system, named SDF-FuzzIA, to support stakeholders operating in geo-thematic domains in making informed, transparent decisions. In this architecture, the fuzzy ontology constitutes the system’s semantic layer. For additional details on SDF-FuzzIA, see [

54].

Finally, as a direction for future work, we intend to replace human experts with algorithmic surrogates (e.g., aggregation algorithms), thereby enabling the assignment of expert weights in a principled and reproducible manner. As already noted, eliciting from people is fraught with difficulties—not least because individuals typically resist being numerically scored. Algorithms, by contrast, are readily amenable to quantitative evaluation according to objective indicators such as execution time and memory footprint. In order to operationalise this idea, we could incorporate a fuzzy rule-based weighting module, specifically a Mamdani-type inference system composed of IF–THEN rules, which maps the aforementioned performance indicators to the weights assigned to the experts (algorithms). Moreover, because algorithmic experts consume and produce numerical values without additional interpretive overhead, their use directly addresses the limitation highlighted in Remark 10, aligning expert assessment with the algorithm’s native domain . Furthermore, we remark that it is, in general, rather difficult to determine a priori the types of algorithms and the objective metrics to be adopted in weighting them as experts. This is because the choice of algorithms may depend on a variety of factors, including the extent to which they are intrinsically linked to the specific decision problem. For instance, the experts (algorithms) employed in an MCGDM concerning a classification problem would inevitably differ from those used in a medical or healthcare-related MCGDM. A change in the type of experts necessarily implies a corresponding change in the objective metrics by which they are to be evaluated. For this reason, we have elected not to dwell on the particular categories of algorithms considered as experts here. However, one could envisage as experts the classical methodologies employed for the evaluation and classification of alternatives in decision-making problems (for instance, SAW, TOPSIS, and VIKOR, among others). In such a case, the decision metrics might include computational efficiency, memory consumption, sensitivity to rank reversal, and so forth.