An Architecture of Enhanced Profiling Assurance for IoT Networks

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Objective

1.2. Scope

- improvement to the effectiveness of malicious activity detection over the current MUD standard;

- IP-based IoT networks;

- MUD deployment in small-scale networks.

- mitigation of other than traffic amplification attacks;

- software-defined network (SDN)-based MUD deployments as these are not found in small-scale networks;

- authentication/authenticity of MUD files;

- MUD profile format/MUD profile generation and retrieval;

- non-IP-based networks;

- large-scale IoT networks.

1.3. Research Method

1.4. Contribution

- proposes a new gateway-based MUD architecture that enables stateless and stateful communication inspection to improve the effectiveness of malicious activity detection;

- employs layered intrusion detection and prevention systems (IDPSs) to improve the effectiveness of malicious activity detection;

- introduces the network behaviour analysis (NBA) system with network behaviour knowledge databases to conduct a stateful inspection of the network communication states;

- presents three-way decision theory with allow, deny, and uncommitted to allow continuous monitoring for uncertain network behaviours.

1.5. Paper Structure

2. Background

2.1. Manufacturer Usage Description (MUD)

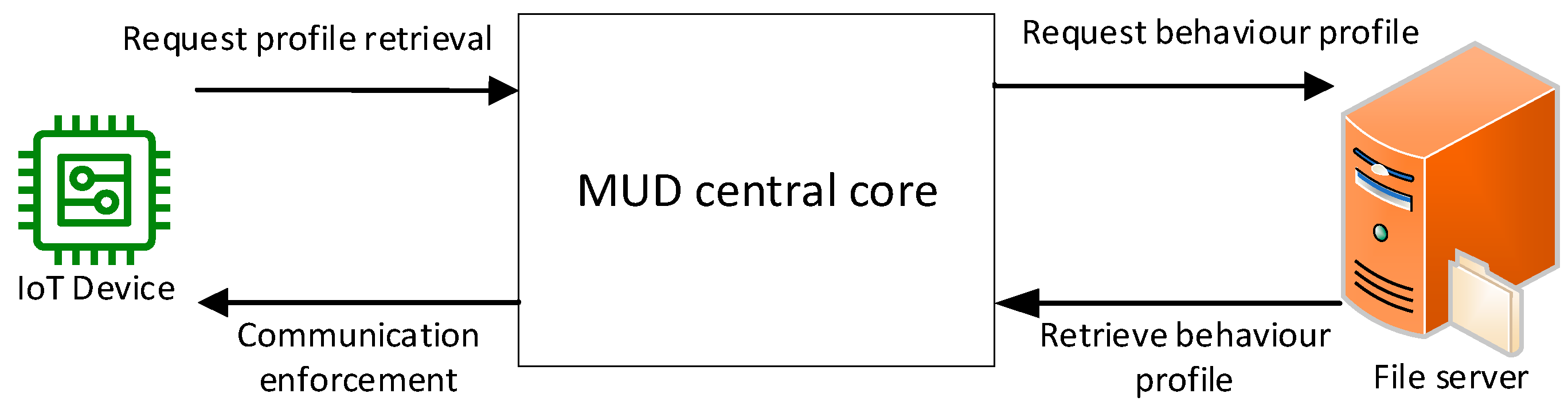

2.2. MUD Architecture

- Thing: the IoT device that transmits the MUD URL for MUD file retrieval.

- Router/Switch: provides the internet connection to the Thing.

- MUD Manager: the central core of MUD architecture. It retrieves and translates the MUD file into ACL rules for communication enforcement.

- MUD File Server: the file server that hosts the MUD file by the manufacturer or related entities.

- extract the MUD URL from the requested device for MUD file retrieval;

- retrieve the MUD file from the hosted MUD file server;

- translate the MUD file into the ACL rules for communication enforcement at the IDPS;

- maintain and update the behaviour profile and network configuration.

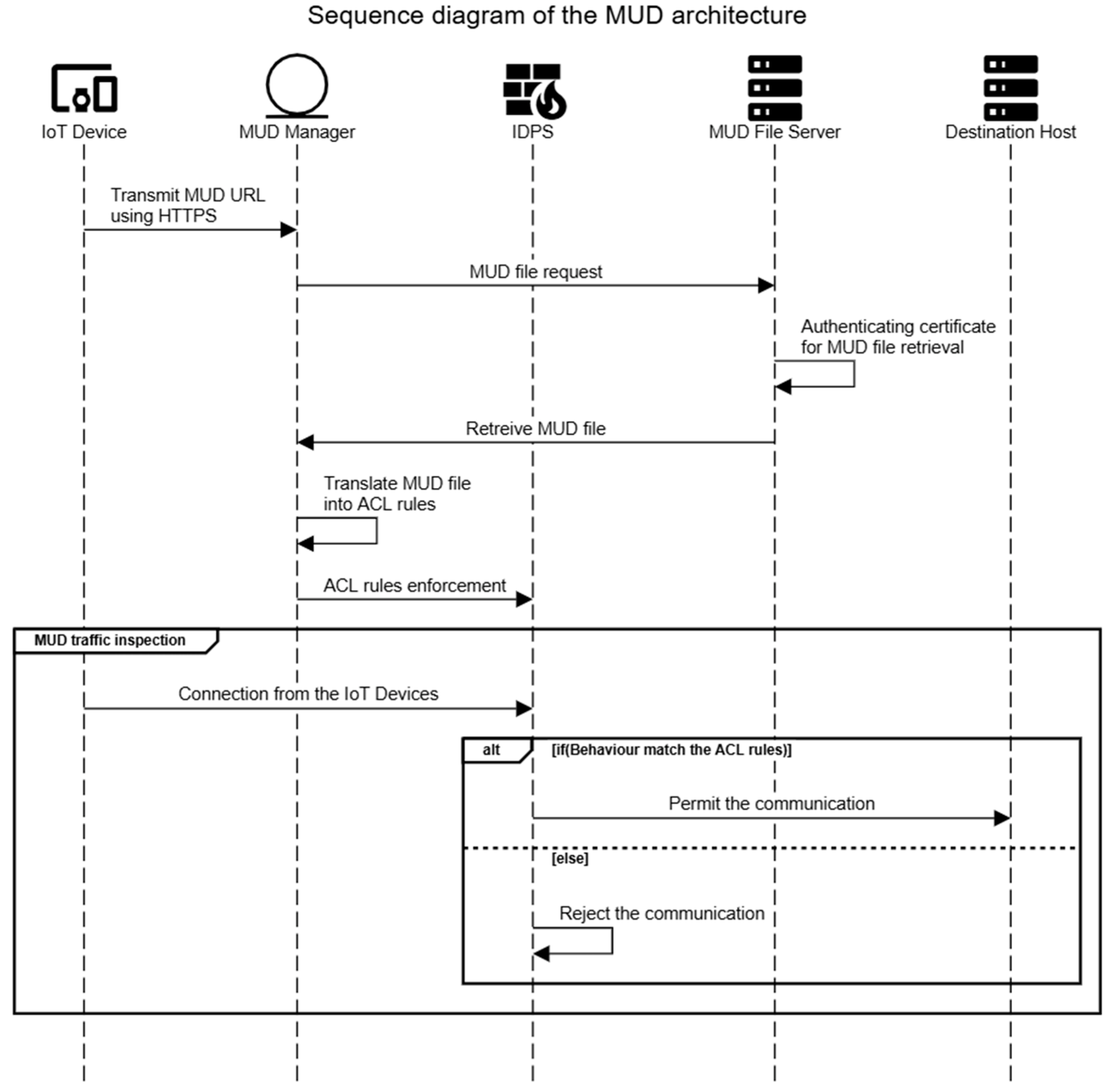

- In the first connection, the IoT device transmits the MUD URL to the MUD manager for the MUD profile request.

- The MUD manager extracts the MUD URL for MUD file retrieval and then requests the MUD file from the hosted file server.

- MUD file server authenticating certificate to ensure the authenticity of MUD file request.

- The MUD manager retrieves the MUD file and translates it into the ACL rules to enforce at the IDPS.

- Enforcing ACL rules at the IDPS for traffic monitoring.

- The IDPS receives new connections from the IoT device and conducts stateless inspection based on the ACL rules. The IDPS will permit the communication if the behaviour matches the ACL rules and reject it if it does not.

- software define network (SDN)-based MUD deployment;

- gateway-based MUD deployment.

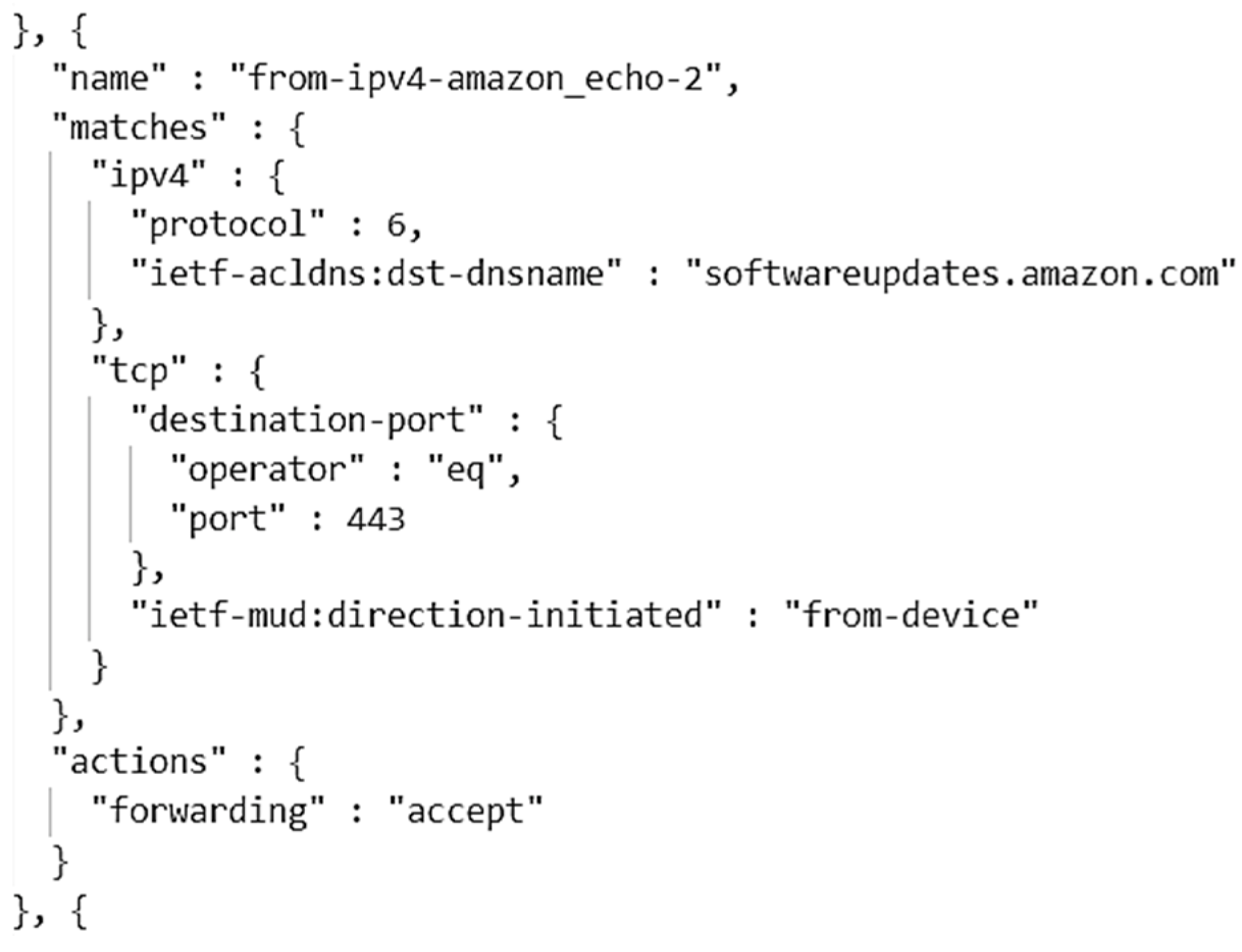

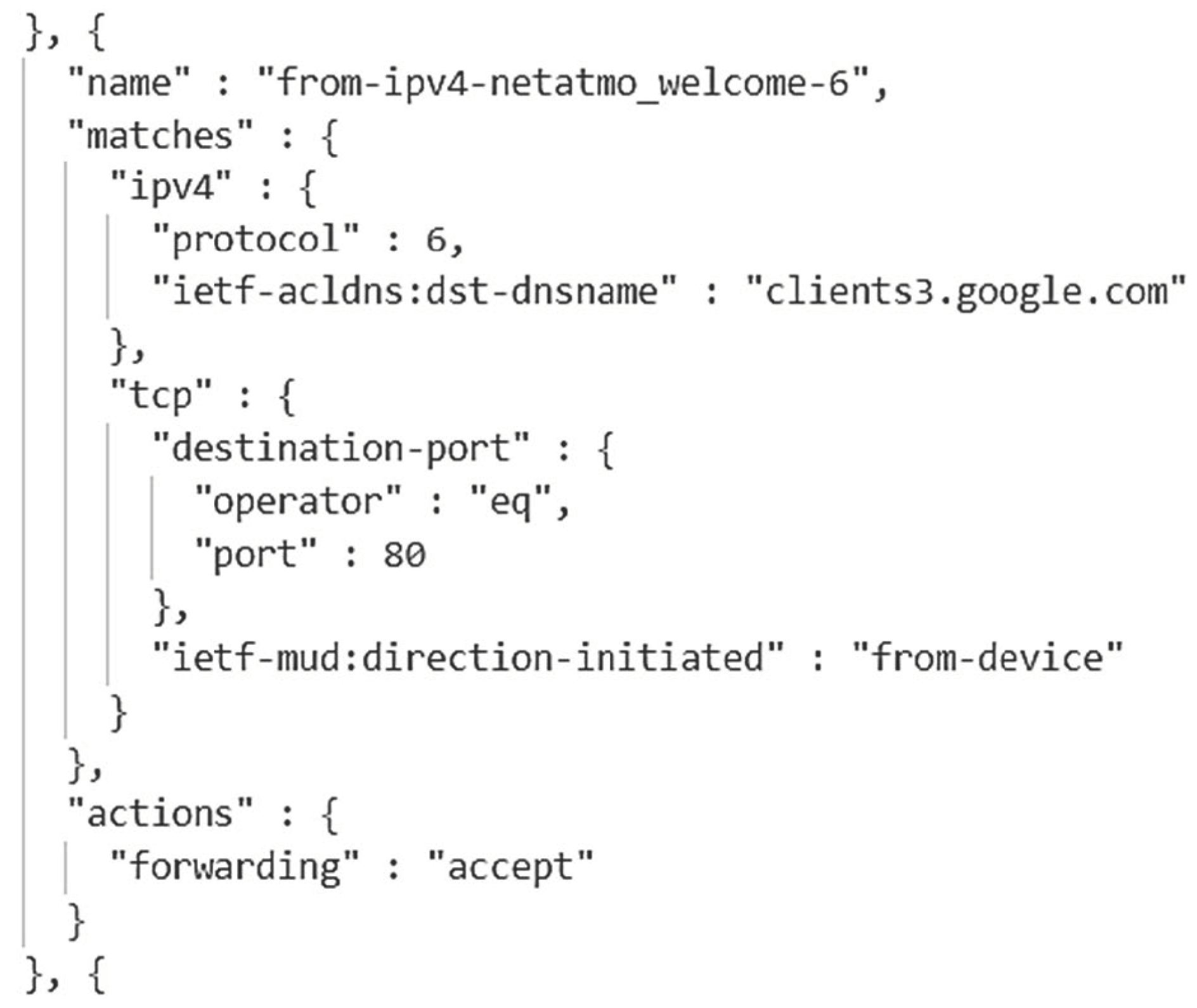

2.3. MUD Behaviour Profile

- Name: Name of the ACL and access control entry (ACE);

- Type: Connection type, either IPv4 or IPv6;

- Protocol: Protocol number defined by the Internet Assigned Numbers Authority (IANA) [7];

- Destination (dst): The address of the destination host to which it is to be connected; Port: Port number usage of each connectivity. Depending on the manufacturer, this can be a well-known port assigned by IANA [8] or a custom port;

- Direction-initiated: Description of connection initiation direction for TCP-based communication. It can be “from-device” or “to-device”;

- Forwarding: Denotes that it will either allow or deny this communication behaviour.

3. Related Works

3.1. MUD Impact on IoT Security and Supporters

3.2. Gateway-Based MUD Architecture

3.3. Network Traffic Analysis in MUD-Based Networks

3.4. Three-Way Decision Theory for Intrusion Detection

3.5. Limitations of the MUD Architecture

- The MUD architecture only conducts stateless traffic inspections without monitoring communication states. This could cause false negative filtering, as malicious activities might pass through the MUD enforcement.

- The MUD architecture does not support uncommitted decisions for uncertain network behaviours, which requires continuous analysis.

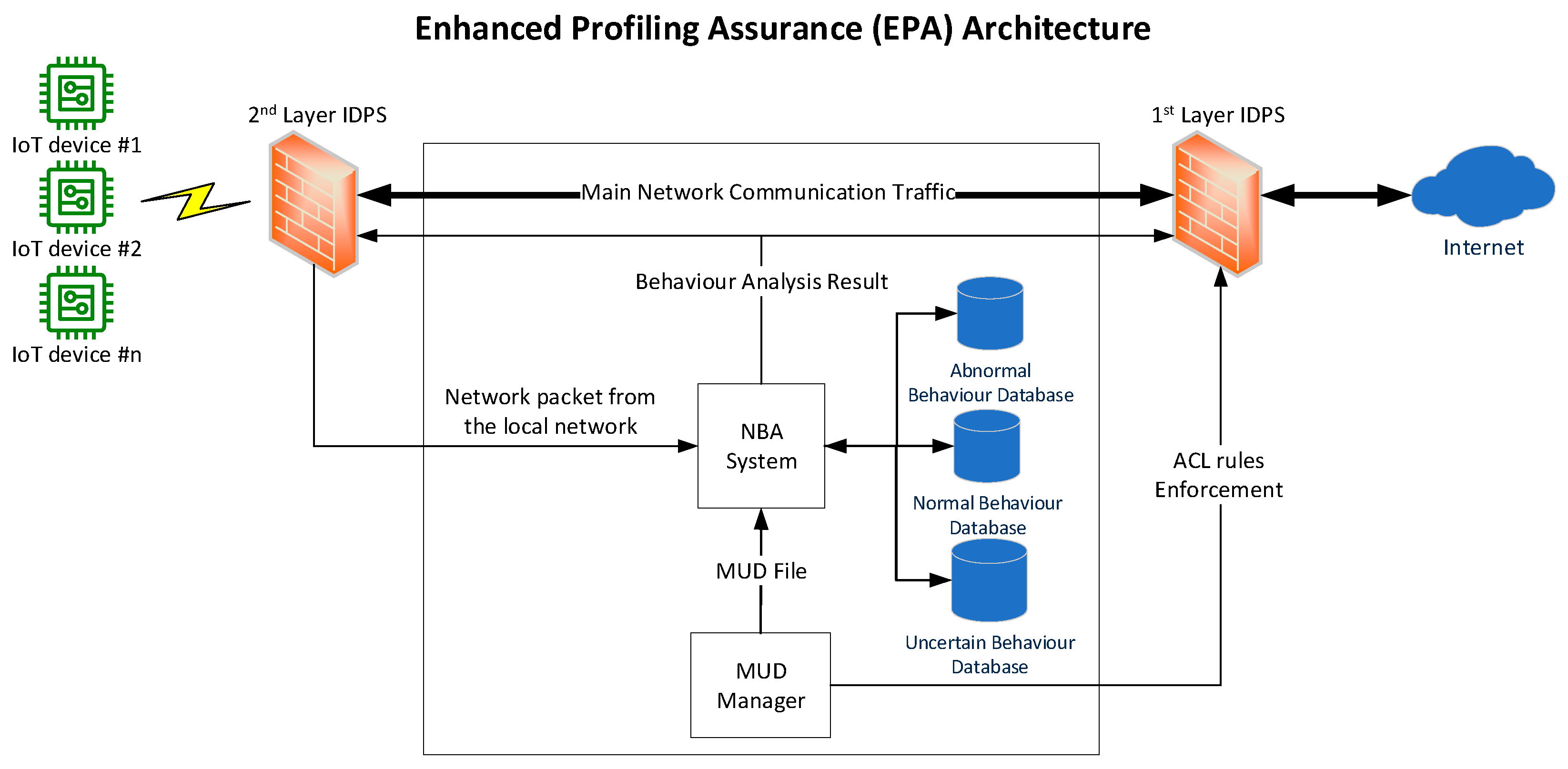

4. Proposal of the EPA

- stateless and stateful communication inspection to detect malicious activity effectively;

- three-way decision-making with allow, deny, and uncommitted to continuously analyse uncertain behaviours.

- The MUD architecture relies on stateless inspections for packet filtering, which may be insufficient to detect and prevent malicious activities as the attack patterns evolve.

- A two-layer IDPS can separate simple and complex traffic monitoring tasks to reduce the traffic congestion that occurs in the first layer, thus reducing the latency in network inspection.

- A two-layer IDPS design can avoid a single point of failure. If one IDPS is down, another active IDPS can still operate to prevent malicious activity from reaching the destination host.

- The second layer of the IDPS can protect the MUD manager and NBA system by segregating the IoT networks from being directly connected to the MUD manager and NBA system.

- A two-layer IDPS in the EPA is the conceptual design that displays how it can protect against malicious activities. The IDPS can be deployed on a single or separate entity as EPA does not specify the physical setup.

4.1. Components

- 1.

- MUD manager

- 2.

- NBA system

- the NBA system first conducts stateless inspection using ACL rules from the MUD file for packet filtering;

- the stateful communication inspection is conducted after stateless inspection to monitor communication states for malicious activity detection.

- 3.

- Network behaviour knowledge databases

- Abnormal behaviour database

- Normal behaviour database

- Uncertain behaviour database

- 4.

- First layer of the IDPS

- 5.

- Second layer of the IDPS

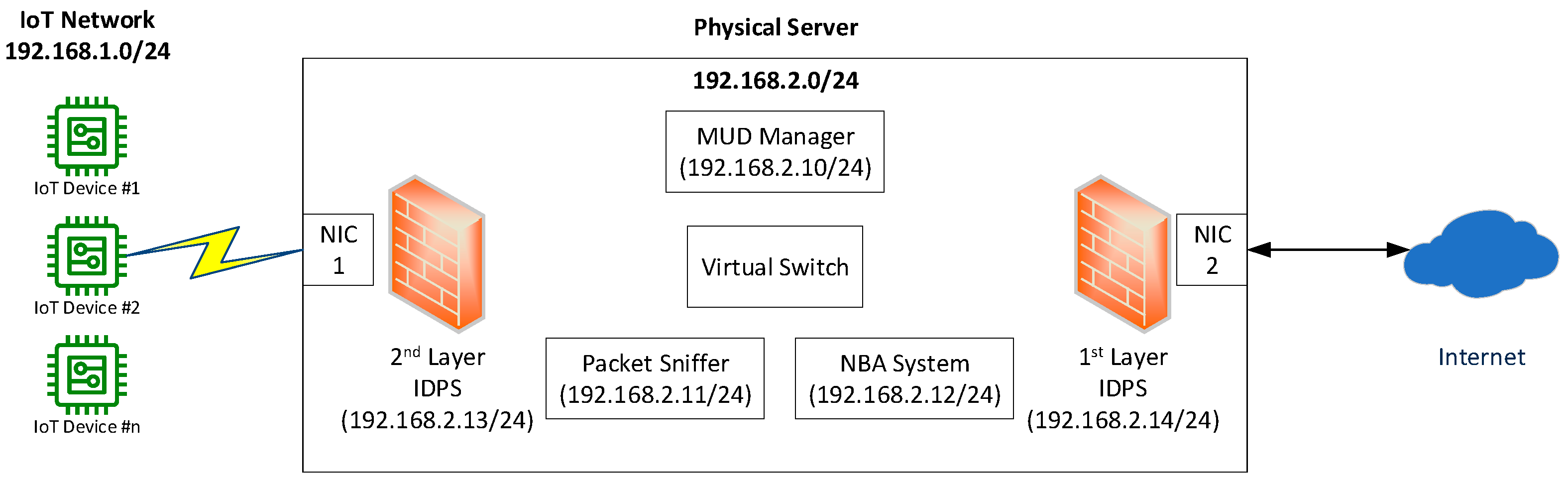

4.2. Implementation of the EPA

- one physical server with two network interface cards (NICs) and a Linux-based OS/Hypervisor;

- five Linux-based VMs for the following:

- MUD manager (OSMUD);

- packet sniffer (tcpdump)

- NBA system;

- first layer of the IDPS (iptables);

- second layer of the IDPS (iptables).

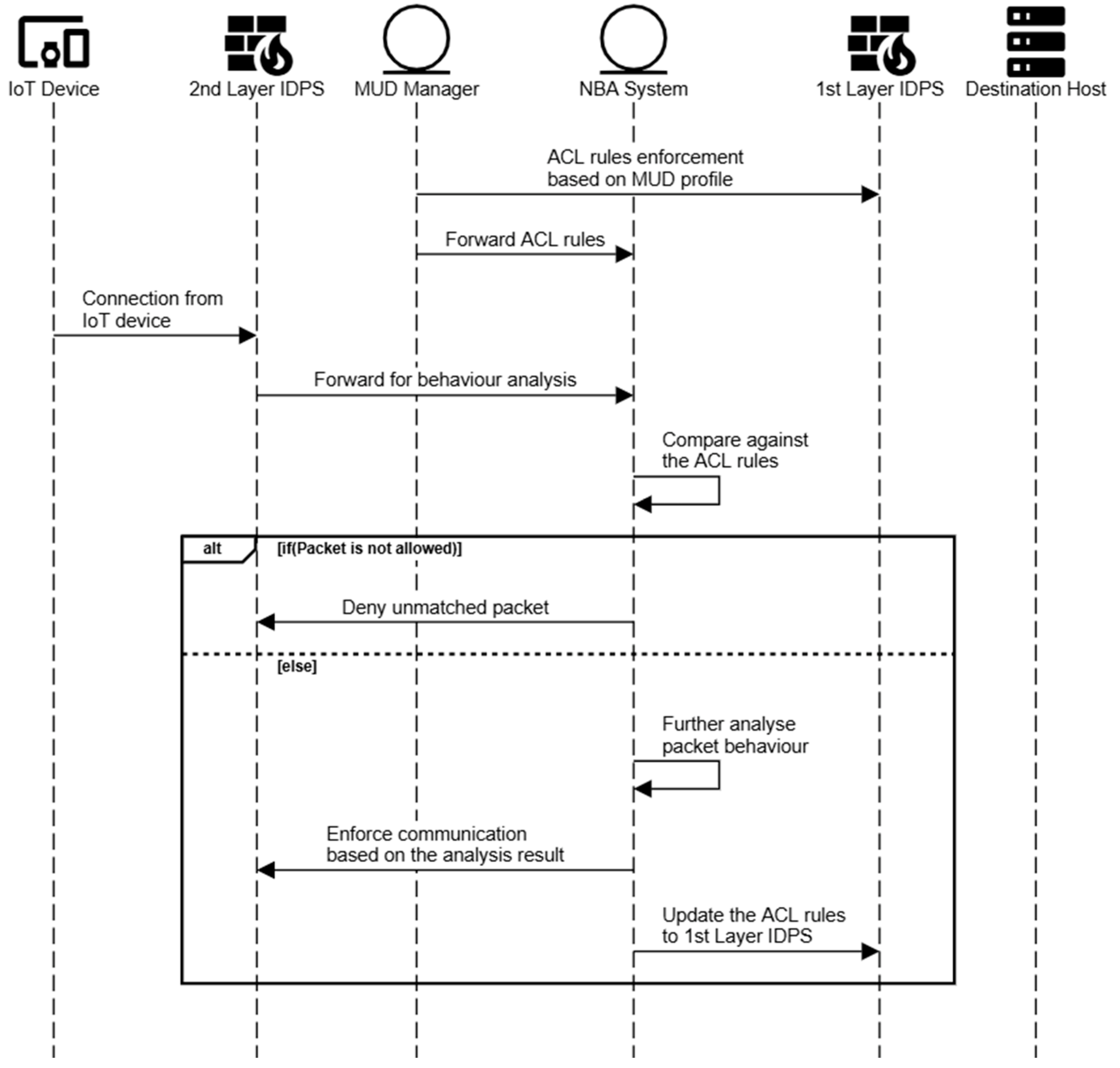

4.3. EPA Workflow and Decision-Making

4.3.1. Workflow of the EPA

- the MUD manager retrieves the MUD file, translates it into ACL rules, and then enforces it at the first layer of the IDPS;

- the MUD Manager forwards the MUD file to the NBA system;

- the IoT device sends communication packets through the second layer of the IDPS;

- the second layer of the IDPS forwarded the received packet to be analysed by the NBA system;

- the NBA system compares the received packet against the ACL rules specified in the MUD file;

- if the packet behaviour does not match the ACL rules, it will be rejected;

- if the packet behaviour matches the ACL rules, further analysis will be conducted to detect malicious activity;

- based on the result of the analysis, the NBA system informs the second layer of the IDPS to allow or deny the connection;

- the NBA system informs the first layer of the IDPS to reject similar connection patterns.

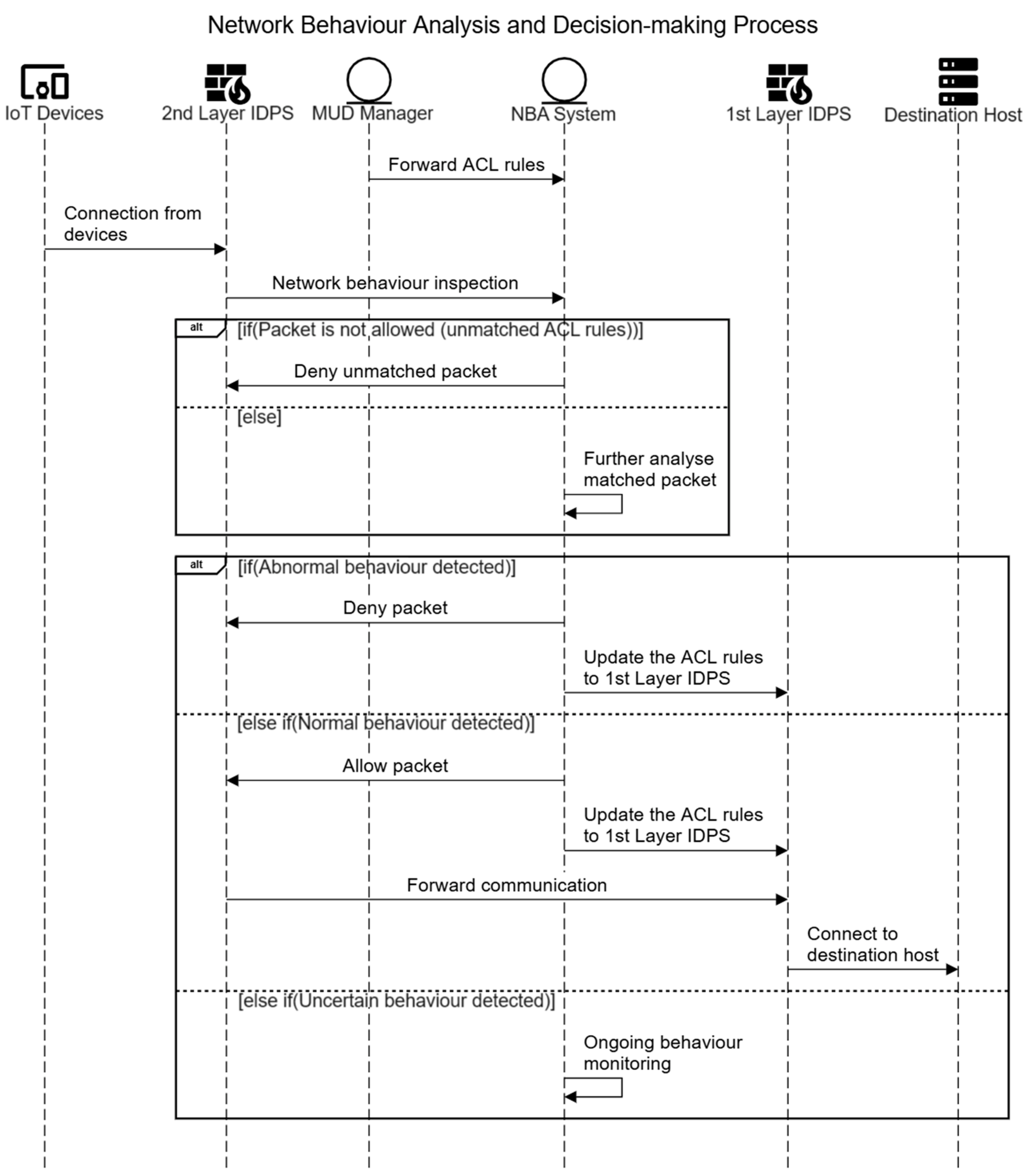

4.3.2. Network Behaviour Analysis and Decision-Making Process

| Algorithm 1 Network behaviour analysis and decision-making |

| Require: MUDretrieval {MUD file retrieval and ACL translation function of MUD manager} ACLrules {translated ACL rules from MUD file} packet {captured packet for analysis} IDPSupdate {function for updating the ACL rules of both IDPSs} action {action for allowing or denying packet for updating IDPSs} ongoingmonitor {ongoing behaviour monitoring function} 1: ACLrules ← MUDretrieval() 2: if packet = ACLrules then 3: if packet = abnormal then 4: action ← deny 5: IDPSupdate() 6: break 7: else if packet = normal then 8: action ← allow 9: IDPSupdate() 10: break 11: else if packet = uncertain then 12: ongoingmonitor() 13: end if 14: else 15: return deny 16: end if |

- rejection of the unmatched packet;

- further analysis of the packet behaviour to detect malicious activity.

- the transmission rate is higher than the usual rate;

- the transmission rate does not match the previous rate;

- there is a mismatched protocol and port number usage (for example, traffic arrived at port 80, but it is not the HTTP communication).

5. Analysis

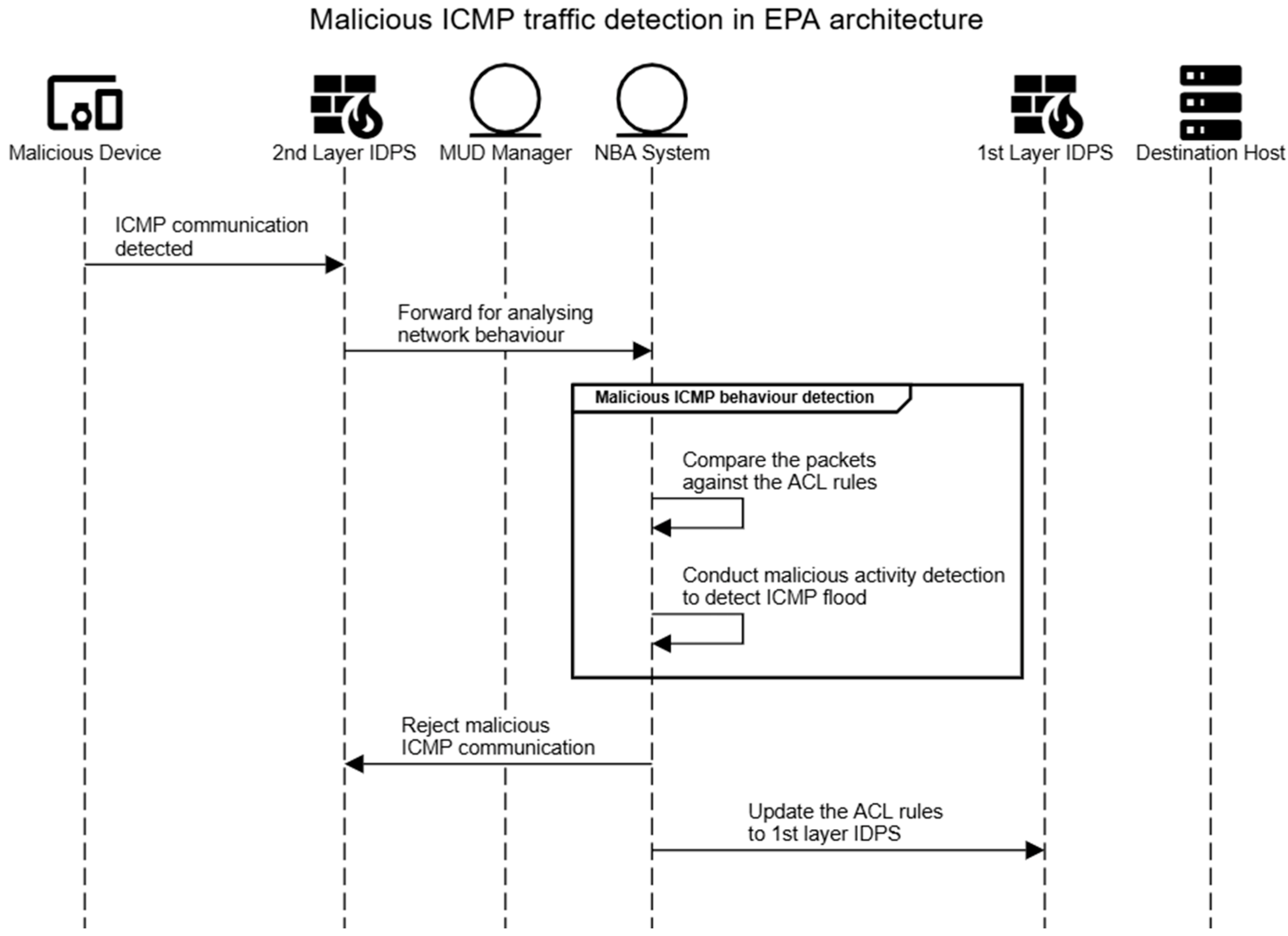

5.1. Malicious ICMP Traffic Detection

- the IoT device sends ICMP echo-request packets to the destination host through the second layer of the IDPS;

- the second layer of the IDPS forwards the arrived ICMP packets to be analysed by the NBA system;

- the NBA system compares the received ICMP packets against the access control list (ACL) rules specified in the MUD file;

- the ICMP packets match the ACL rule in the MUD file, and then the NBA conducts malicious detection against the abnormal behaviour database, normal database, and uncertain behaviour databases;

- it identifies that this is a malicious ICMP flood attack;

- the NBA system informs the first and second layers of the IDPS to block this malicious ICMP flood traffic.

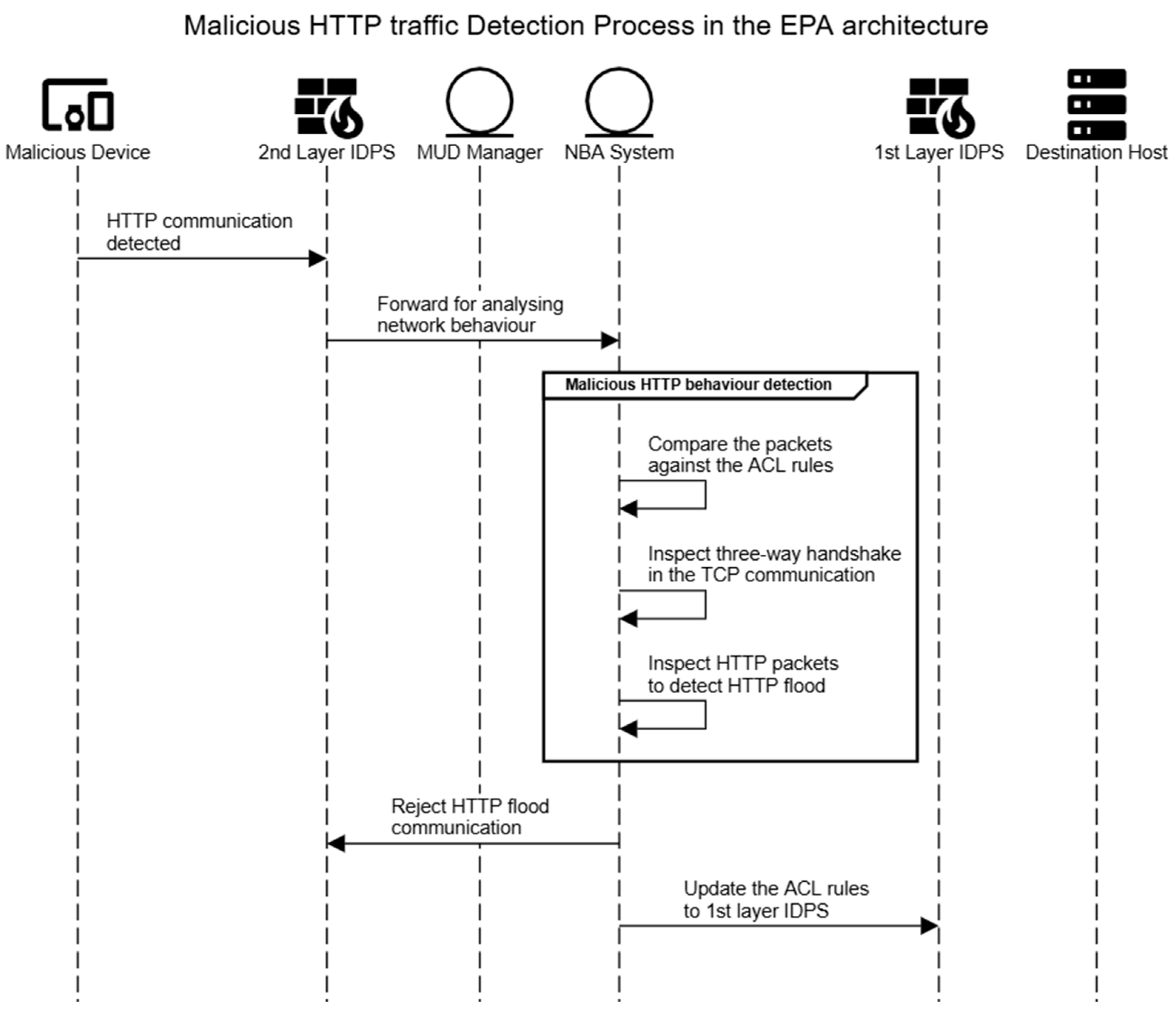

5.2. Malicious HTTP Traffic Detection

- The IoT device sends HTTP packets through the second layer of the IDPS;

- The second layer of the IDPS forwards the arrived packets to be analysed by the NBA system;

- The NBA system compares the received HTTP packets against the ACL rules specified in the MUD profile;

- The HTTP packets match the ACL rule in the MUD profile. Then, the NBA conducts malicious detection against the abnormal behaviour database, normal database, and uncertain behaviour databases;

- The NBA system inspects the three-way handshake process in TCP communication. Then, it inspects the HTTP request packets to identify that it is a malicious HTTP flood packet;

- The NBA system informs the second layer of the IDPS to reject this HTTP flood communication;

- The second layer of the IDPS forwards the analysis result to the first layer of the IDPS to prevent this malicious communication.

6. Conclusions and Future Work

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Nayak, G.; Mishra, A.; Samal, U.; Mishra, B.K. Depth Analysis on DoS & DDoS Attacks. In Wireless Communication Security; Scrivener Publishing: Beverly, MA, USA, 2022; pp. 159–182. [Google Scholar]

- Gamblin, J. Mirai BotNet. Available online: https://github.com/jgamblin/Mirai-Source-Code (accessed on 15 March 2024).

- Greenstein, S. The Aftermath of the Dyn DDOS Attack. IEEE Micro 2019, 39, 66–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoachimik, O.; Pacheco, J. DDoS threat report for 2024 Q1. Available online: https://blog.cloudflare.com/ddos-threat-report-for-2024-q1 (accessed on 17 April 2024).

- Lear, E.; Droms, R.; Romascanu, D. RFC 8520: Manufacturer Usage Description Specification. Available online: https://datatracker.ietf.org/doc/html/rfc8520 (accessed on 15 March 2024).

- Jethanandani, M.; Agarwal, S.; Huang, L.; Blair, D. YANG Data Model for Network Access Control Lists (ACLs). Available online: https://datatracker.ietf.org/doc/html/rfc8519 (accessed on 9 May 2024).

- Boehm, B.; Howard, B.; Aboba, B.; Petri, B.; Nguyen, B.; McIntosh, B.; Braden, B.; Hinden, B.; Kantor, B.; Lee, C.; et al. Protocol Numbers. Available online: https://www.iana.org/assignments/protocol-numbers/protocol-numbers.xhtml (accessed on 17 May 2024).

- Touch, J.; Lear, E.; Ono, K.; Eddy, W.; Trammell, B.; Iyengar, J.; Scharf, M.; Tuexen, M.; Kohler, E.; Nishida, Y. Service Name and Transport Protocol Port Number Registry. Available online: https://www.iana.org/assignments/service-names-port-numbers/service-names-port-numbers.xhtml (accessed on 17 May 2024).

- Heeb, Z.; Kalinagac, O.; Soussi, W.; Gur, G. The Impact of Manufacturer Usage Description (MUD) on IoT Security. In Proceedings of the 2022 1st International Conference on 6G Networking (6GNet), Paris, France, 6–8 July 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Souppaya, M.; Montgomery, D.; Polk, T.; Ranganathan, M.; Dodson, D.; Barker, W.; Johnson, S.; Kadam, A.; Pratt, C.; Thakore, D.; et al. Securing Small-Business and Home Internet of Things (IoT) Devices: Mitigating Network-Based Attacks Using Manufacturer Usage Description (MUD); National Institute of Standards and Technology: Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Watrobski, P.; Klosterman, J. MUD-PD. Available online: https://github.com/usnistgov/MUD-PD (accessed on 24 March 2024).

- Lear, E.; Weis, B. Slinging MUD: Manufacturer usage descriptions: How the network can protect things. In Proceedings of the 2016 International Conference on Selected Topics in Mobile & Wireless Networking (MoWNeT), Cairo, Egypt, 11–13 April 2016. [Google Scholar]

- What is MUD? Available online: https://developer.cisco.com/docs/mud/what-is-mud/#what-is-mud (accessed on 16 May 2024).

- DeKok, A.; Cudbard-Bell, A.; Newton, M.; Clouter, A. FreeRADIUS. Available online: https://freeradius.org/ (accessed on 16 May 2024).

- Shah, R.; Madson, C.; Lear, E. CiscoDevNet MUD-Manager. Available online: https://github.com/CiscoDevNet/MUD-Manager (accessed on 16 May 2024).

- Hamza, A.; Ranathunga, D.; Gharakheili, H.H.; Roughan, M.; Sivaraman, V. Clear as MUD: Generating, Validating and Applying IoT Behavioral Profiles. In Proceedings of the 2018 Workshop on IoT Security and Privacy, Budapest, Hungary, 20 August 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Hamza, A. MUDGEE. Available online: https://github.com/ayyoob/mudgee (accessed on 4 March 2024).

- Hamza, A.; Ranathunga, D.; Gharakheili, H.H.; Benson, T.A.; Roughan, M.; Sivaraman, V. Verifying and Monitoring IoTs Network Behavior Using MUD Profiles. IEEE Trans. Dependable Secur. Comput. 2022, 19, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamza, A.; Ranathunga, D.; Habibi Gharakheili, H.; Benson, T.A.; Roughan, M.; Sivanathan, A. MUD Profiles. Available online: https://iotanalytics.unsw.edu.au/mudprofiles.html (accessed on 9 May 2024).

- osMUD—The Open Source MUD Manager. Available online: https://osmud.org/ (accessed on 20 March 2024).

- OpenWRT. Available online: https://openwrt.org/ (accessed on 20 March 2024).

- Kelly, S. Dnsmasq. Available online: https://thekelleys.org.uk/dnsmasq/doc.html (accessed on 20 March 2024).

- Andalibi, V.; Kim, D.; Camp, J. Throwing MUD into the FOG: Defending IoT and Fog by expanding MUD to Fog network. In Proceedings of the 2nd USENIX Workshop on Hot Topics in Edge Computing, HotEdge 2019, Co-Located with USENIX ATC 2019, Renton, WA, USA, 9 July 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Corno, F.; Mannella, L. A Gateway-based MUD Architecture to Enhance Smart Home Security. In Proceedings of the 2023 8th International Conference on Smart and Sustainable Technologies (SpliTech), Split/Bol, Croatia, 20–23 June 2023; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Home Assistant. Available online: https://www.home-assistant.io/ (accessed on 26 March 2024).

- Feraudo, A.; Popescu, D.A.; Yadav, P.; Mortier, R.; Bellavista, P. Mitigating IoT Botnet DDoS Attacks through MUD and eBPF based Traffic Filtering. In Proceedings of the 25th International Conference on Distributed Computing and Networking, Chennai, India, 4–7 January 2024; pp. 164–173. [Google Scholar]

- Sajjad, S.M.; Yousaf, M.; Afzal, H.; Mufti, M.R. eMUD: Enhanced Manufacturer Usage Description for IoT Botnets Prevention on Home WiFi Routers. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 164200–164213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OWASP Firmware Security Testing Methodology. Available online: https://github.com/scriptingxss/owasp-fstm (accessed on 25 May 2024).

- Feraudo, A.; Yadav, P.; Safronov, V.; Popescu, D.A.; Mortier, R.; Wang, S.; Bellavista, P.; Crowcroft, J. CoLearn: Enabling federated learning in MUD-compliant IoT edge networks. In Proceedings of the Third ACM International Workshop on Edge Systems, Analytics and Networking, Heraklion, Greece, 7 April 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Ziller, A.; Trask, A.; Lopardo, A.; Szymkow, B.; Wagner, B.; Bluemke, E.; Nounahon, J.-M.; Passerat-Palmbach, J.; Prakash, K.; Rose, N.; et al. PySyft: A Library for Easy Federated Learning. In Federated Learning Systems: Towards Next-Generation AI.; Rehman, M.H.u., Gaber, M.M., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 111–139. [Google Scholar]

- Datta, S.; Bhattacharya, A.; Rana, R.; Venkanna, U. iDAM: A Distributed MUD Framework for Mitigation of Volumetric Attacks in IoT Networks. In Proceedings of the 2022 13th International Symposium on Communication Systems, Networks and Digital Signal Processing (CSNDSP), Porto, Portugal, 20–22 July 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Un Nisa, K.; Alhudhaif, A.; Qureshi, K.N.; Hadi, H.J.; Jeon, G. Security provision for protecting intelligent sensors and zero touch devices by using blockchain method for the smart cities. Microprocess. Microsyst. 2022, 90, 104503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afek, Y.; Bremler-Barr, A.; Hay, D.; Shalev, A. MUDirect: Protecting P2P IoT Devices with MUD. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE International Conferences on Internet of Things (iThings) and IEEE Green Computing & Communications (GreenCom) and IEEE Cyber, Physical & Social Computing (CPSCom) and IEEE Smart Data (SmartData) and IEEE Congress on Cybermatics (Cybermatics), Melbourne, Australia, 6–8 December 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Hadi, H.J.; Sajjad, S.M.; Nisa, K. BoDMitM: Botnet Detection and Mitigation System for Home Router Base on MUD. In Proceedings of the 2019 International Conference on Frontiers of Information Technology (FIT), Islamabad, Pakistan, 16–18 December 2019; pp. 139–1394. [Google Scholar]

- Cisco. Snort—Network Intrusion Detection & Prevention System. Available online: https://www.snort.org/ (accessed on 18 March 2024).

- Zangrandi, L.M.; Ede, T.V.; Booij, T.; Sciancalepore, S.; Allodi, L.; Continella, A. Stepping out of the MUD: Contextual threat information for IoT devices with manufacturer-provided behavior profiles. In Proceedings of the 38th Annual Computer Security Applications Conference, Austin, TX, USA, 5–9 December 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Zangrandi, L.M.; Ede, T.V. MUDscope. Available online: https://github.com/lucamrgs/MUDscope (accessed on 3 April 2024).

- Morgese Zangrandi, L.; van Ede, T.; Booij, T.; Sciancalepore, S.; Allodi, L.; Continella, A. MUDscope dataset. Available online: https://zenodo.org/records/7182597 (accessed on 30 May 2024).

- Andalibi, V.; Dev, J.; Kim, D.; Lear, E.; Camp, L.J. Is Visualization Enough? Evaluating the Efficacy of MUD-Visualizer in Enabling Ease of Deployment for Manufacturer Usage Description (MUD). In Proceedings of the Annual Computer Security Applications Conference, Virtual Event, 6–10 December 2021; pp. 337–348. [Google Scholar]

- Lear, E.; Andalibi, V. MUD Visualizer. Available online: https://github.com/iot-onboarding/mud-visualizer (accessed on 30 March 2024).

- Bremler-Barr, A.; Meyuhas, B.; Shister, R. MUDIS: MUD Inspection System. In Proceedings of the NOMS 2022–2022 IEEE/IFIP Network Operations and Management Symposium, Budapest, Hungary, 25–29 April 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Bremler-Barr, A.; Meyuhas, B.; Shister, R. One MUD to Rule Them All: IoT Location Impact. In Proceedings of the NOMS 2022–2022 IEEE/IFIP Network Operations and Management Symposium, Budapest, Hungary, 25–29 April 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Zhang, L.; Xu, Y.; Yao, Y.; Lau, R.Y.K.; Wu, Y. Enhancing Binary Classification by Modeling Uncertain Boundary in Three-Way Decisions. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng. 2017, 29, 1438–1451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subhashini, L.D.C.S.; Li, Y.; Zhang, J.; Atukorale, A.S. Assessing the effectiveness of a three-way decision-making framework with multiple features in simulating human judgement of opinion classification. Inf. Process. Manag. 2022, 59, 102823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subhashini, L.D.C.S.; Li, Y.; Zhang, J.; Atukorale, A.S. Integration of Fuzzy and Deep Learning in Three-Way Decisions. In Proceedings of the 2020 International Conference on Data Mining Workshops (ICDMW), Sorrento, Italy, 17–20 November 2020; pp. 71–78. [Google Scholar]

- Subhashini, L.D.C.S.; Li, Y.; Zhang, J.; Atukorale, A.S. Integration of Fuzzy and LSTM in Three-Way Decisions. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE/WIC/ACM International Joint Conference on Web Intelligence and Intelligent Agent Technology (WI-IAT), Melbourne, Australia, 14–17 December 2020; pp. 975–980. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, Y. An Intrusion Detection Algorithm for DDoS Attacks Based on DBN and Three-way Decisions. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2022, 2356, 012044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, X.; Li, Y.; Zhang, S. Research on Intrusion Detection Algorithm Based on Deep Belief Networks and Three-way Decisions. In Proceedings of the 2020 4th International Conference on Electronic Information Technology and Computer Engineering, Xiamen, China, 6–8 November 2020; pp. 50–56. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, S.; Li, Y.; Du, X. An Intrusion Detection Approach Based on Autoencoder and Three-way Decisions. In Proceedings of the 2020 4th International Conference on Electronic Information Technology and Computer Engineering, Xiamen, China, 6–8 November 2020; pp. 495–500. [Google Scholar]

- Geng, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhang, S. Research on Multi-granularity Intrusion Detection Algorithm Based onSequential Three-Way Decision. In Proceedings of the 2021 5th International Conference on Electronic Information Technology and Computer Engineering, Xiamen, China, 22–24 October 2021; pp. 1154–1160. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, C.; Wang, W.; Liu, L.; Ren, J.; Wang, L. Three-Branch Random Forest Intrusion Detection Model. Mathematics 2022, 10, 4460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Reference | Application | Inspection Techniques | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| [23] | Unspecified | Stateless | MUD manager deployment on fog computing. |

| [24] | Smart home | Stateless | Local behaviour policies and MUD profile generation. |

| [26] | Unspecified | Stateless | Rate limit extension and backend deployment for packet filtering. |

| [27] | Smart home | - | Firmware testing and vulnerability detection on the gateway. |

| [29] | - | Stateless | Focus on employing federated learning for authorising device connection. |

| [31] | Smart home | Stateless | Employing federated learning with two-level defence. |

| [32] | Smart cities | - | Firmware testing and vulnerability detection on the gateway. |

| [33] | Smart home | Stateless | Extending MUD profile to support P2P networks. |

| Reference | Application Usage | Description |

|---|---|---|

| [34] | Smart home protection | MUD-rejected traffic analysis for attack source detection and notification. |

| [36] | Attack type identification | MUD-rejected traffic analysis to identify attack type. |

| [39] | Visualising MUD traffic | Development of MUD traffic visualiser tool. |

| [41] | Behaviour profile inspection and merging | Development of MUD behaviour profile analysis and profile merging tool, MUDIS. |

| [42] | Impact of location on MUD profile generation demonstration | Implemented MUDIS from [41] to demonstrate the impact of location on MUD profile generation. |

| Reference | Techniques | Evaluation | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| [47] | DBN, Three-way decision, and KNN | Real SDN traffic | Integrated three-way decision with DBN for intrusion detection in SDN. |

| [48] | DBN, Three-way decision, and KNN | KDD Cup 99 and NSL-KDD | Integrated three-way decision with DBN for intrusion detection. |

| [49] | Autoencoder and Three-way decision | NSL-KDD | Using autoencoder for denoising before classification for intrusion detection. |

| [50] | Autoencoder and Sequential three-way decision | NSL-KDD | Using autoencoder to extract multi-granularity with sequential three-way decision. |

| [51] | Three-way decision and random forest | NSL-KDD | Using three-way decision to divide attributes for random forest forming. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Aroon, N.; Liu, V.; Kane, L.; Li, Y.; Tesfamicael, A.D.; McKague, M. An Architecture of Enhanced Profiling Assurance for IoT Networks. Electronics 2024, 13, 2832. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics13142832

Aroon N, Liu V, Kane L, Li Y, Tesfamicael AD, McKague M. An Architecture of Enhanced Profiling Assurance for IoT Networks. Electronics. 2024; 13(14):2832. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics13142832

Chicago/Turabian StyleAroon, Nut, Vicky Liu, Luke Kane, Yuefeng Li, Aklilu Daniel Tesfamicael, and Matthew McKague. 2024. "An Architecture of Enhanced Profiling Assurance for IoT Networks" Electronics 13, no. 14: 2832. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics13142832

APA StyleAroon, N., Liu, V., Kane, L., Li, Y., Tesfamicael, A. D., & McKague, M. (2024). An Architecture of Enhanced Profiling Assurance for IoT Networks. Electronics, 13(14), 2832. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics13142832