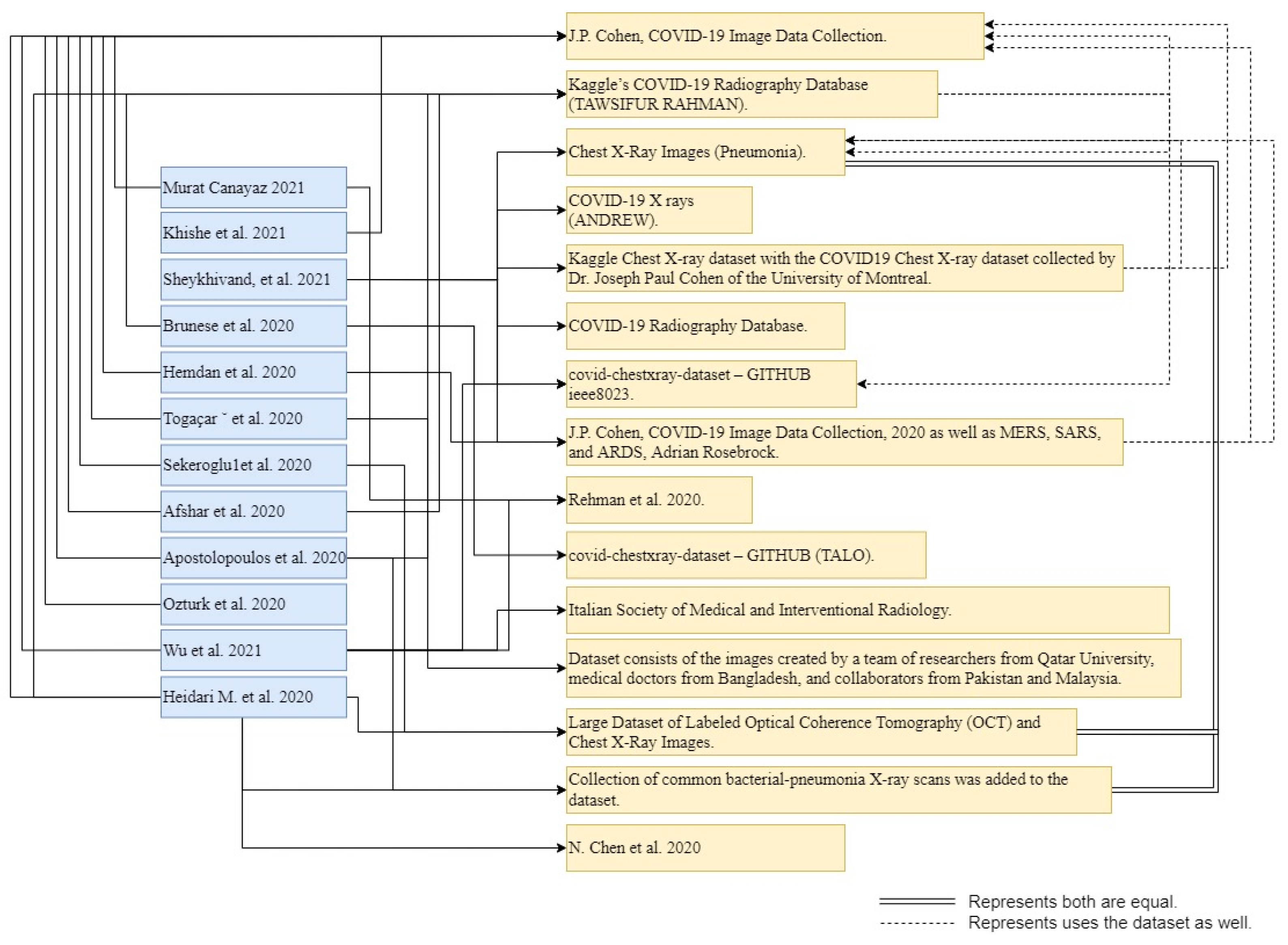

Wu et al. [

5] used a dataset of CXIs, i.e., the Radiography Dataset of Kaggle [

23]. This dataset includes 2905 CXIs, which are divided into three classes, containing 1341 healthy CXIs, 1345 of pneumonia, and 219 CXIs of COVID-19. This image repository also includes three different datasets: CXIs of COVID-19 are collected from the Italian Society of Medical and Interventional Radiology COVID-19 Dataset (SIRM) and from the Novel COVID-19 2019 dataset, which was established by Dr. Cohen at GitHub [

17]. The dataset differs from those used in many articles published recently. The pneumonia and healthy CXIs were collected from Kaggle’s Chest X-ray pneumonia dataset [

20]. Sheykhivand et al. [

6], in their experiment, used six different trustworthy and reliable datasets that were based on CXIs. Recently, these databases frequently been used in studies focusing on the automatic detection of COVID-19 symptoms [

18,

19,

20,

21,

24,

28]. These datasets include posterior–anterior CXIs of patients with pneumonia. These CXIs include four different classes, namely, viral pneumonia, bacterial pneumonia, healthy, and COVID-19. Murat Canayaz [

2] used datasets that had been discovered by Joseph Paul Cohen [

17] and Kaggle [

23]. There were 145 images of COVID-19 in the first dataset, and in the second dataset, there were 219 images of COVID-19; these datasets are easily and openly available. By merging these datasets, a dataset containing 364 images was obtained for COVID-19. A dataset including pneumonia and normal CXIs, which was prepared in [

29], was used in this experiment. Hemdan et al. [

7] implemented the proposed model on publicly available images on the basis of a dataset provided by Dr. Joseph Cohen [

17] and Dr. Adrian Rosebrock [

28], which was used in this study for the classification of COVID-19 results as being either negative or positive. There were 50 CXIs in this dataset, which were categorized into two classes, i.e., half of them were positive images, and the remaining half were negative images for COVID-19 in this dataset. Togaçar et al. [

3] performed an experiment using three classes of classification, i.e., pneumonia CXIs, normal CXIs, and COVID-19, on the basis of datasets that were easily and publicly available. In their research, the authors used a combination of two datasets that were publicly and easily accessible, and which contained images of COVID-19. The first COVID-19 dataset was found on the GitHub website, and was shared by the researcher Dr. Joseph Paul Cohen [

17]. These images were subsequently examined by experts and made accessible on the public website GitHub. Images of MERS, SARS, COVID-19, and other diseases can be found in Dr. Joseph Paul Cohen’s dataset. For this experiment, a dataset with 76 images highlighting COVID-19 was chosen. The CXIs were developed by a team of researchers from Qatar University, medical practitioners from Bangladesh, and partners from Pakistan and Malaysia, and were included in the second COVID-19 dataset. The current COVID-19 dataset comprises 219 CXIs, and is the second dataset to have been made available on Kaggle [

8,

19]. The 225 CXIs of COVID-19 used by Boran Sekeroglu and Ilker Ozsahin [

8] were discovered in [

17], and have been made freely available on GitHub [

24]. The age of the COVID-19 group was noted as being 58.8 ± 14.9 years, and the dataset consisted of 131 male patients and 64 female patients. Please note that information was missing for some patients; this is because the datasets used did not always contain complete data, it was the first publicly available dataset containing images of CXIs of COVID-19 collection, and it was developed in a very short period of time. This dataset contains four types of labels, i.e., healthy, bacterial, non-COVID viral, and COVID-19. The study aimed to determine the results for COVID-19: either positive or negative. However, the negative class was organized into three labels—healthy, bacterial, and non-COVID viral. Afshar et al. [

9] generated a dataset from a publicly available dataset of CXIs [

17,

24] and performed experiments. Apostolopoulos et al. [

10] used a collection of CXIs provided by Dr. Joseph Cohen [

17]. The work in [

29] employed bacterial-pneumonia CXIs, and a dataset made available on the Internet [

21] was examined by the Italian Society of Medical and Interventional Radiology (SIRM), Radiopaedia, and the Radiological Society of North America (RSNA). Ozturk et al. [

11] used two CXI datasets for the identification of COVID-19. The dataset contained CXIs which were developed by Dr. Cohen [

17] using images from different open contact sources. This dataset is continually being updated with images that have been shared by researchers from around the world. Furthermore, a database of chest X-rays was provided by the researchers in [

30], and was used to detect normal and pneumonia images. Using the suggested strategy, Brunese et al. [

12] analyzed several datasets belonging to various universities. Furthermore, researchers have used three different CXI datasets: the first was the collection of “Images with infection of COVID-19” [

17], and the second dataset [

24] was used by authors of the paper “Automated Detection of COVID- 19 Cases Using Deep Neural Networks with X-ray Images” [

24], while the third dataset included the collections from the “National Institutes of Health Chest X-ray” [

30]. In the end, by merging all of the datasets, it was possible to obtain results of chest X-rays that were linked to several classes. Heidari et al. [

13] developed and collected a dataset of CXIs that was easily available in public medical repositories [

17,

23,

29,

31]. These data image repositories were initially produced and studied at the Georgetown University Center for Security and Emerging Technology, the National Library of Medicine, the National Institutes of Health, and Microsoft Research, by the Allen Institute of AI and Chan Zuckerberg, coordinated by the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy. Specifically, the dataset used in this study contained 8474 2D images of CXIs in the posterior–anterior chest view. Among them, 415 images showed confirmed COVID-19 disease, 2880 images showed healthy (non-pneumonia) patients, and 5179 images belonged to other community-acquired non-COVID-19-infected pneumonia cases.

Table 2 presents a detailed discussion of the above literature review regarding the datasets used by the authors and the classes used for classification, training, testing, and validation.

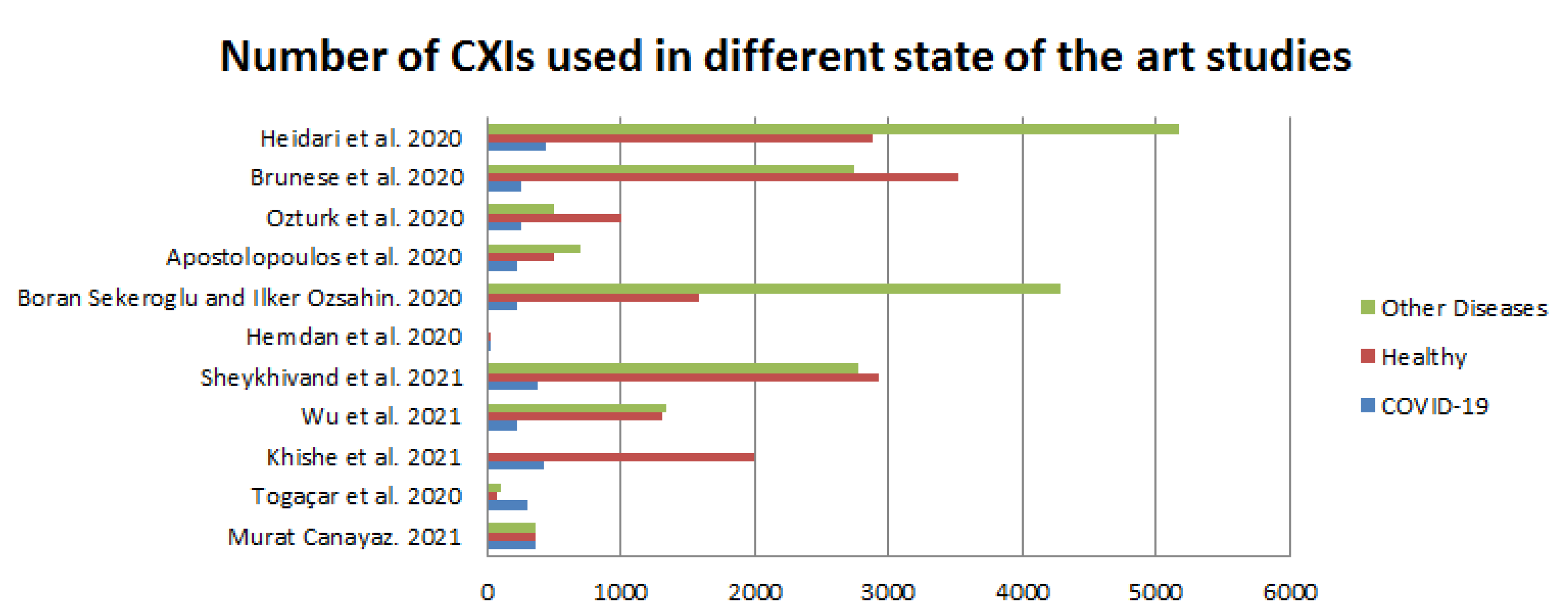

Figure 3, below, illustrates the smaller amount of data used by authors in more recent studies. However, the dataset of Dr. Joseph [

17] has been used by almost all researchers for the classification task. Furthermore, the dataset of Dr. Joseph [

17] is very famous, and is used by many researchers in current research, as well.