Cutaneous Permeation and Penetration of Sunscreens: Formulation Strategies and In Vitro Methods

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Organic Filters

2.1. Substances that Protect against UVA Radiation

2.2. Substances that Protect against UVB Radiation

2.3. Broad-Spectrum Substances (UVA + UVB)

2.4. Natural Compounds

2.5. Inorganic Filters

2.6. Nanomaterials

3. In Vitro Methods

4. Formulation Strategies

5. Discussion

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Skotarczak, K.; Osmola-Man Kowska, A.; Lodyga, M.; Polanska, A.; Mazur, M.; Adamski, Z. Photoprotection: Facts and controversies. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2015, 19, 98–112. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.Q.; Xu, H.; Stanfield, J.W.; Osterwalder, U.; Herzog, B. Comparison of ultraviolet A light protection standards in the United States and European Union through in vitro measurements of commercially available sunscreens. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2017, 77, 42–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haque, T.; Crowther, J.M.; Lane, M.E.; Moore, D.J. Chemical ultraviolet absorbers topically applied in a skin barrier mimetic formulation remain in the outer stratum corneum of porcine skin. Int. J. Pharm. 2016, 510, 250–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.Q.; Osterwalder, U.; Jung, K. Ex vivo evaluation of radical sun protection factor in popular sunscreens with antioxidants. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2011, 65, 525–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martins, R.M.; Siqueira, S.; Fonseca, M.J.; Freitas, L.A. Skin penetration and photoprotection of topical formulations containing benzophenone-3 solid lipid microparticles prepared by the solvent-free spray-congealing technique. J. Microencapsul. 2014, 31, 644–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, C.C.; Lin, Y.T.; Chen, Y.T.; Sie, S.F.; Chen-Yang, Y.W. Improvement in UV protection retention capability and reduction in skin penetration of benzophenone-3 with mesoporous silica as drug carrier by encapsulation. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B 2015, 148, 277–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puglia, C.; Damiani, E.; Offerta, A.; Rizza, L.; Tirendi, G.G.; Tarico, M.S.; Curreri, S.; Bonina, F.; Perrotta, R.E. Evaluation of nanostructured lipid carriers (NLC) and nanoemulsions as carriers for UV-filters: Characterization, in vitro penetration and photostability studies. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2014, 51, 211–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mancebo, S.E.; Hu, J.Y.; Wang, S.Q. Sunscreens: A review of health benefits, regulations, and controversies. Dermatol. Clin. 2014, 32, 427–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quatrano, N.A.; Dinulos, J.G. Current principles of sunscreen use in children. Curr. Opin. Pediatr. 2013, 25, 122–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gilbert, E.; Pirot, F.; Bertholle, V.; Roussel, L.; Falson, F.; Padois, K. Commonly used UV filter toxicity on biological functions: Review of last decade studies. Int. J. Cosmet. Sci. 2013, 35, 208–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Detoni, C.B.; Coradini, K.; Back, P.; Oliveira, C.M.; Andrade, D.F.; Beck, R.C.; Pohlmann, A.R.; Guterres, S.S. Penetration, photo-reactivity and photoprotective properties of nanosized ZnO. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 2014, 13, 1253–1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gulson, B.; McCall, M.J.; Bowman, D.M.; Pinheiro, T. A review of critical factors for assessing the dermal absorption of metal oxide nanoparticles from sunscreens applied to humans, and a research strategy to address current deficiencies. Arch. Toxicol. 2015, 89, 1909–1930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hung, C.-F.; Chen, W.-Y.; Aljuffali, I.A.; Shih, H.-C.; Fang, J.-Y. The risk of hydroquinone and sunscreen over-absorption via photodamaged skin is not greater in senescent skin as compared to young skin: Nude mouse as an animal model. Int. J. Pharm. 2014, 471, 135–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, Y.; Ediriwickrema, A.; Yang, F.; Lewis, J.; Girardi, M.; Saltzman, W.M. A sunblock based on bioadhesive nanoparticles. Nat. Mater. 2015, 14, 1278–1285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saettone, M.F.; Alderigi, C.; Giannaccini, B.; Anselmi, C.; Rossetti, M.G.; Scotton, M.; Cerini, R. Substantivity of sunscreens—Preparation and evaluation of some quaternary ammonium benzophenone derivatives. Int. J. Cosmet. Sci. 1988, 10, 99–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freitas, J.V.; Praça, F.S.; Bentley, M.V.; Gaspar, L.R. Trans-resveratrol and beta-carotene from sunscreens penetrate viable skin layers and reduce cutaneous penetration of UV-filters. Int. J. Pharm. 2015, 484, 131–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monti, D.; Tampucci, S.; Chetoni, P.; Burgalassi, S.; Saino, V.; Centini, M.; Staltari, L.; Anselmi, C. Permeation and distribution of ferulic acid and its α-cyclodextrin complex from different formulations in hairless rat skin. AAPS PharmSciTech 2011, 12, 514–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monti, D.; Brini, I.; Tampucci, S.; Chetoni, P.; Burgalassi, S.; Paganuzzi, D.; Ghirardini, A. Skin permeation and distribution of two sunscreens: A comparison between reconstituted human skin and hairless rat skin. Skin Pharmacol. Physiol. 2008, 21, 318–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monti, D.; Chetoni, P.; Burgalassi, S.; Tampucci, S.; Centini, M.; Anselmi, C. 4-Methylbenzylidene camphor microspheres: Reconstituted epidermis (Skinethic®) permeation and distribution. Int. J. Cosmet. Sci. 2015, 37, 298–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gilbert, E.; Roussel, L.; Serre, C.; Sandouk, R.; Salmon, D.; Kirilov, P.; Haftek, M.; Falson, F.; Pirot, F. Percutaneous absorption of benzophenone-3 loaded lipid nanoparticles and polymeric nanocapsules: A comparative study. Int. J. Pharm. 2016, 504, 48–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hopkins, Z.R.; Snowberger, S.; Blaney, L. Ozonation of the oxybenzone, octinoxate, and octocrylene UV-filters: Reaction kinetics, absorbance characteristics, and transformation products. J. Hazard Mater. 2017, 338, 23–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gallardo Cabrera, C.; Pinillos Madrid, J.F.; Pazmiño Arteaga, J.D.; Munera Echeverry, A. Characterization of Encapsulation Process of Avobenzone in Solid Lipid Microparticle Using a Factorial Design and its Effect on Photostability. J. App. Pharm. Sci. 2014, 4, 35–43. [Google Scholar]

- Rai, R.; Shanmuga, S.C.; Srinivas, C. Update on Photoprotection. Indian J. Dermatol. 2012, 57, 335–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dunkel, V.C.; San, R.H.; Harbell, J.W.; Seifried, H.E.; Cameron, T.P. Evaluation of the mutagenicity of an N-nitroso contaminant of the sunscreen Padimate O: N-nitroso-N-methyl-p-aminobenzoic acid, 2-ethylhexyl ester (NPABAO). Environ. Mol. Mutagen. 1992, 20, 188–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Durand, L.; Habran, N.; Henschel, V.; Amighi, K. Encapsulation of ethylhexyl methoxycinnamate, a light-sensitive UV filter, in lipid nanoparticles. J. Microencapsul. 2010, 27, 714–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baker, L.A.; Horbury, M.D.; Greenough, S.E.; Ashfold, M.N.R.; Stavros, V.G. Broadband ultrafast photoprotection by oxybenzone across the UVB and UVC spectral regions. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 2015, 14, 1814–1820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donglikar, M.M.; Deore, S.L. Sunscreens: A review. Pharmacogn. J. 2016, 8, 171–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonofiglio, D.; Giordano, C.; De Amicis, F.; Lanzino, M.; Andò, S. Natural Products as Promising Antitumoral Agents in Breast Cancer: Mechanisms of Action and Molecular Targets. Mini. Rev. Med. Chem. 2016, 16, 596–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Camera, E.; Mastrofrancesco, A.; Fabbri, C.; Daubrawa, F.; Picardo, M.; Sies, H.; Stahl, W. Astaxanthin, canthaxanthin and β-carotene differently affect UVA-induced oxidative damage and expression of oxidative stress-responsive enzymes. Exp. Dermatol. 2009, 18, 222–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jain, P.; Rahi, P.; Pandey, V.; Asati, S.; Soni, V. Nanostructure lipid carriers: A modish contrivance to overcome the ultraviolet effects. Egypt. J. Basic Appl. Sci. 2017, 4, 89–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larese Filon, F.; Mauro, M.; Adami, G.; Bovenzi, M.; Crosera, M. Nanoparticles skin absorption: New aspects for a safety profile evaluation. Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2015, 72, 310–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tampucci, S.; Burgalassi, S.; Chetoni, P.; Lenzi, C.; Pirone, A.; Mailland, F.; Caserini, M.; Monti, D. Topical Formulations Containing Finasteride. Part II: Determination of Finasteride Penetration into Hair Follicles using the Differential Stripping Technique. J. Pharm. Sci. 2014, 103, 2323–2329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verma, A.; Jain, A.; Hurkat, P.; Jain, S.K. Transfollicular drug delivery: Current perspectives. Res. Rep. Transdermal Drug Deliv. 2016, 5, 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Schmook, F.P.; Meingassner, J.G.; Billich, A. Comparison of human skin or epidermis models with human and animal skin in in-vitro percutaneous absorption. Int. J. Pharm. 2001, 215, 51–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, E.C.; Maibach, H.I. Animal models for percutaneous absorption. J. Appl. Toxicol. 2015, 35, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shokri, J.; Hasanzadeh, D.; Ghanbarzadeh, S.; Dizadji-Ilkhchi, D.; Adibkia, K. The Effect of Beta-Cyclodextrin on Percutaneous Absorption of Commonly Used Eusolex® Sunscreens. Drug Res. 2013, 63, 591–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, C.-C.; Lin, L.-H.; Lee, H.-T.; Tsai, J.-R. Avobenzone encapsulated in modified dextrin for improved UV protection and reduced skin penetration. Chem. Pap. 2016, 70, 840–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abd, E.; Yousef, S.A.; Pastore, M.N.; Telaprolu, K.; Mohammed, Y.H.; Namjoshi, S.; Grice, J.E.; Roberts, M.S. Skin models for the testing of transdermal drugs. Clin. Pharmacol. 2016, 8, 163–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peres, P.S.; Terra, V.A.; Guarnier, F.A.; Cecchini, R.; Cecchini, A.L. Photoaging and Chronological Aging Profile: Understanding Oxidation of the Skin. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B 2011, 103, 93–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benson, H.A.; Sarveiya, V.; Risk, S.; Roberts, M.S. Influence of anatomical site and topical formulation on skin penetration of sunscreens. Ther. Clin. Risk Manag. 2005, 1, 209–218. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Klang, V.; Schwarz, J.C.; Hartl, A.; Valenta, C. Facilitating in vitro tape stripping: Application of infrared densitometry for quantification of porcine SC proteins. Skin Pharmacol. Physiol. 2011, 24, 256–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, C.C.; Chen, Y.T.; Lin, Y.T.; Sie, S.F.; Chen-Yang, Y.W. Mesoporous silica aerogel as a drug carrier for the enhancement of the sunscreen ability of benzophenone-3. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2014, 115, 191–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.R.; Chen, K.M. Preparation and surface active properties of biodegradable dextrin derivative surfactants. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2006, 281, 190–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, S.N.; Jeong, E.; Prausnitz, M.R. Transdermal Delivery of Molecules is Limited by Full Epidermis, Not Just Stratum Corneum. Pharm. Res. 2013, 30, 1099–1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| INCI Name (INN/XAN) | Chemical Structure | Brand Name | Absorption Spectrum Range | Molecular Weight (g/mol) | Log P | Water Solubility (mg/L) | Melting Point (°C) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

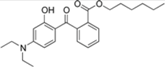

| diethylamino hydroxybenzoyl hexyl benzoate |  | Uvinul® A Plus | UVA1 | 397.515 4 | 5.7–6.2 1 | <0.01 (20 °C) 1 | 54; 314 (dec.) 1 |

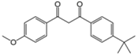

| Butyl methoxydibenzoylmetha ne (avobenzone) |  | Eusolex® 020, Parsol® 1789 | UVA | 310.393 4 | 4.51 4 | 2.2 (25 °C) 4 | 83.5 4 |

| 4-methylbenzylidene camphor (enzacamene) |  | Eusolex® 6300 Parsol® 5000 Uvinul® MBC 95 | UVB | 258.397 4 | 4.95 | 1.3 (20 °C) | 66–68 |

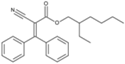

| Octocrylene (octocrilene) |  | Eusolex® OCR, Parsol® 340, Uvinul® N539T, NeoHeliopan® 303 USP | UVB | 361.485 4 | 6.78 3 | 0.0038 3 | N/A |

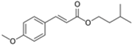

| isoamyl p-methoxycinnamate (amiloxate) |  | Neo Heliopan® E1000 | UVB | 248.322 4 | 3.6 1 | 4.9 (25 °C) 1 | N/A |

| Ethylhexyl triazone |  | Uvinul® T150 | UVB | 823.092 4 | >7 (20 °C) 6 | <0.001 (20.0 °C) 6 | 129 6 |

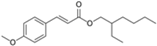

| Ethylhexyl methoxycinnamate (octinoxate) |  | Parsol® MCX, Heliopan® New | UVB | 290.403 4 | 6.1 4 | 0.041 (24 °C and pH 7.1) 4 | N/A |

| Ethylhexyl dimethyl PABA (padimate-O) |  | Escalol ™ 507 Arlatone 507 Eusolex 6007 | UVB | 277.408 4 | 5.77 4 | 0.54 (25 °C) 4 | N/A |

| benzophenone-3 (oxybenzone) |  | Eusolex® 4360 | UVA2 + UVB | 228.247 4 | 3.7 2 | 3.7 (20 °C) 2 | 62–65 2 |

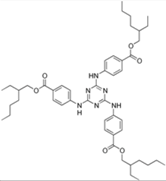

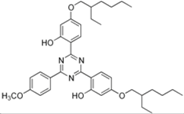

| bis-ethylhexyloxyphenol methoxyphenol triazine (bemotrizinol) |  | Tinosorb® S | UVA1 + UVB | 627.826 4 | 12.6 1 | <10−4 | 80.40 1 |

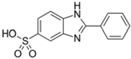

| Phenylbenzimidazole sulfonic acid (ensulizole) |  | Eusolex® 232 Parsol® HS Neo Heliopan® Hydro | UVA2 + UVB | 274.294 5 | −1.1 (pH 5) −2.1 (pH 8) 5 | >30% (As sodium or triethanolammonium salt at 20 °C 5 | N/A |

| Reference | Sun-Filter | Formulation | Substrate | Equipment | T (°C) | Receiving Phase | Lenght (h) | Analitycal Procedure | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [3] | IPMC DHHB BMZ | Biomimetic O/W cream | Full thickness porcine ear skin | Franz cell | 30 | 6% Brij PBS | 12 | HPLC -receiving phase -15 tape strips for SC removal -remaining tissue | None of the molecules was detected in the receiving phase after 12h and the sunscreens were largely detected in the 5 tape strips |

| [5] | BP-3 | SLM | Porcine ear skin | Franz cell | 37 | Buffer 150 mM pH 7.2 + 0.5% Tween 80 | 12 | HPLC tape stripping (SC) and E+D | SLM with natural waxes are able to inhibit permeation and reduce 3-fold penetration with respect to free BP-3 |

| [6] | BP3 | -Emulsion -Emulsion with BP3 encapsulated in mesoporous silica | Cellulose membrane | Franz cell | 37 | pH 7.4 buffer + 2% Tween 20 | 24 | UVvis | Skin permeation of BP-3 was prevented due to encapsulation by MS |

| [7] | BMZ ETZ DHHB OMC AVO | NLC | Human skin (SC+E separated from the dermis by treatment at 60°C for 2 min) | Franz cell | 32 | EtOH/water 50:50 | 24 | HPLC | Comparison NLC/nanoemulsion; NLC reduced permeation and the filter remained on the skin surface |

| [9] | 4-MBC | -4-MBC polymeric microspheres in O/W emulsion -free 4-MBC in O/W emulsion | Episkin | Harvard apparatus | 37 | pH 7.4 phosphate buffer 66.7 mM + 1% Brij98 | 5 | HPLC tape stripping (2 strips for SC) and estraction from remaining Epidermis | Encapsulation in microspheres remarkably reduced the permeation of 4-MBC and increased its retention on the skin surface |

| [13] | BP3 AVO ZnO | EtOH/buffer | Nude mice-8 and 24 weeks | Franz cell | 37 | 30% EtOH/ buffer pH 7.4 | 24 | HPLC, atomic abs. differential stripping | UVA and UVA/UVB increased follicular uptake for BP-3 and AVO, particularly for senescent skin; ZnO produced no permeation/penetration; AVO produced no permeation and penetration was higher for young skin |

| [14] | Padimate O | Bioadhesive nanoparticles (BNP) | Fresh pig skin | Incubation of skin with formulation in humidity chamber and subsequent washing with PBS buffer | 32 | / | 6 | HPLC tape stripping (30 strips), remaining skin chopped and extraction performed | No Padimate-O penetrated in the skin from BNPs; minimal amounts were found in the tape stripped skin, suggesting minimal epidermal penetration |

| [16] | BMZ OMC AVO OCT Resveratrol β-Carotene | O/W Emulsion | Porcine ear skin dermatomed at 500 μm | Franz cell | 32 | Phosphate buffer (pH 7.4–0.1 M) + 4% w/v BSA | 12 | HPLC tape stripping (16 strips) and E+D cut in little pieces | The permeated amounts were below LLOQ; over 90% was retained in the SC; the presence of both resveratrol and carotene reduced the amount of UV filters in the SC; BMZ exhibited the lowest penetration rate |

| [20] | BP3 | SLN NLC NPLC NC | Porcine ear skin dermatomed at 600 μm | Franz cell | 37 | Albumina PBS solution | 24 | HPLC -SC ( 20 strips) -E and D separated with scalpel | NPLC and NC were able to significantly reduce BP-3 flux across the skin, exhibiting high in vitro SPF |

| [36] | AVO BP-3 ESZ | Complex with β-cyclodextrin o/w cream | Wistar male rats abdominal skin | Franz cell | 37 | phosphate buffer pH7.4 and isopropyl alcohol 70:30 | 6 | HPLC | ESZ permeated the rat skin in a higher amount; the complex BP-3-CD was found to be the safest one, both in terms of slow rate of permeation and prolonged lag-time |

| [37] | AVO | -AVO encapsulated in modified dextrin formulated in O/W emulsion -- free AVO in O/W emulsion | Cellulose membrane | Franz cell | 37 | pH 5.5 buffer + 2% Tween 20 | 6 | HPLC | AVO encapsuled in modified dextrin and dispersed in an emulsion exhibited a transdermal flux 2.5-fold lower than free AVO. |

© 2017 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tampucci, S.; Burgalassi, S.; Chetoni, P.; Monti, D. Cutaneous Permeation and Penetration of Sunscreens: Formulation Strategies and In Vitro Methods. Cosmetics 2018, 5, 1. https://doi.org/10.3390/cosmetics5010001

Tampucci S, Burgalassi S, Chetoni P, Monti D. Cutaneous Permeation and Penetration of Sunscreens: Formulation Strategies and In Vitro Methods. Cosmetics. 2018; 5(1):1. https://doi.org/10.3390/cosmetics5010001

Chicago/Turabian StyleTampucci, Silvia, Susi Burgalassi, Patrizia Chetoni, and Daniela Monti. 2018. "Cutaneous Permeation and Penetration of Sunscreens: Formulation Strategies and In Vitro Methods" Cosmetics 5, no. 1: 1. https://doi.org/10.3390/cosmetics5010001

APA StyleTampucci, S., Burgalassi, S., Chetoni, P., & Monti, D. (2018). Cutaneous Permeation and Penetration of Sunscreens: Formulation Strategies and In Vitro Methods. Cosmetics, 5(1), 1. https://doi.org/10.3390/cosmetics5010001