Abstract

With the public’s growing interest in skin whitening, lightening ingredients only used under dermatological supervision until recently, are more and more frequently incorporated into cosmetic formulas. The active agents that lighten skin tone are either natural or synthetic substances, and may act at various levels of melanogenesis. They are used to treat various skin pigmentation disorders or simply to obtain a lighter skin tone as whiter skin may be synonymous of wealth, health, youth, and/or beauty in different cultures. However, recent studies demonstrated the adverse effects of some of these ingredients, leading to their interdiction or restricted use under the European Directive and several other international regulations. After an overview of skin whitening practices and the associated risks, this article provides insight into the mechanisms involved in melanin synthesis and the biological assays available to attest the lightening activity of individual ingredients. The legislation dealing with the use of skin lighteners is then discussed. As traditional depigmenting agents such as hydroquinone and corticosteroids are of safety concern, the potential of natural extracts has been investigated more and more; finally, a synthesis of three years of research in our laboratory for such plant extracts will be given.

1. Introduction

Skin whitening or lightening refers to the practice, deeply embedded in many ethnic groups [1], of using natural or synthetic substances to lighten the skin tone or provide an even complexion by reducing the melanin concentration in the skin [2]. The use of whitening agents can be driven by medicinal necessity in the case of persons suffering from dermatological conditions linked to an abnormal accumulation of melanin (e.g., melasma, senile lentigo, etc.) [3] or simply by culture-specific beauty preferences. Numerous chemical substances have already been proven as effective skin whiteners, and some even display beneficial side effects (antioxidants [4,5,6,7], antiproliferative activity [8,9], protection of macromolecules such as collagen against UV radiation [4], etc.), but others have recently raised safety concerns, leading to their ban in some countries. The search for non-cytotoxic natural whitening compounds benefits from the fact that natural ingredients have become more prevalent nowadays in cosmetic formulations due to consumers’ concern about synthetic ingredients and the risks they may represent for human health [10]. In recent years, the quest for fairness has led to the identification of a number of whiteners originating from various biological sources that work as well as the synthetic ones, with few or no side effects [11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18]. However, there is still a long way to go from the discovery of an active ingredient to its incorporation into cosmetics and its commercialization. In fact, ingredients’ cytotoxicity, insolubility, and instability, as well as development costs, are some of the difficulties encountered when establishing a formulation [19]. In the present paper, the melanogenesis pathway as well as the diverse approaches to evaluate the skin whitening activity of an ingredient are presented. The main whitening agents and their status regarding the current legislation are then discussed. Finally, we report feedback from three years of research in our laboratory for plant extracts presenting skin-whitening capacity.

1.1. Why Such a Practice?

Skin whitening has been practiced for several centuries by people from a variety of ethnic backgrounds [1,2,17,20,21,22]. The particular enthusiasm for skin whitening agents originated in the 1960s, driven by the incidental discovery of the whitening action of hydroquinone on the black skins of U.S. workers daily exposed to this agent in the rubber industry. From the 1980s onwards, a blooming interest in skin-whitening cosmetics was observed: lighter complexion may be synonymous with health, youth, and/or beauty in different cultures. This fondness, motivated by complex social, cultural, and historical factors, has not slowed down since.

As already stated, this practice may be driven by dermatological needs. The therapeutic uses of whitening agents include the treatment of hyperpigmentated skin zones to achieve a more uniform appearance. People suffering from skin afflictions such as senile/solar lentigo (small pigmented spots on the skin, varying in diameter from 1 mm up to a few centimeters) [23,24], or wishing to reduce freckles (irregular clusters of melanin-containing cells) and birthmarks often resort to skin whitening. Whitening agents are also often used to treat melasma (also known as chloasma), a skin discoloration that can affect anyone, especially people with a genetic predisposition [25,26]. Most common in pregnant women, it is suspected to be linked to the stimulation of melanin production by female sex hormones when the skin is exposed to the sun [27]. Discoloration agents can also be used on scars, especially on pigmented acne scars, to make the skin color more uniform; hence, these agents are used by a large proportion of people.

On the contrary, vitiligo is a chronic skin condition characterized by portions of the skin losing their pigment when skin pigment cells die or are unable to function [28,29]: the surrounding unaffected skin may be lightened to match to the tone of the affected skin.

Nowadays, skin whitening is more often practiced for aesthetic ends and reaches dramatic proportions among some British, American, Caribbean, African, and Asian communities: whiter/paler skin tone is synonymous with youth, whereas darker skin is pejoratively associated with lower social classes [30]. McDougall (2013) stated that “the global market for skin lighteners is projected to reach US $19.8 billion by 2018, driven by the growing desire for light-colored skin among both men and women primarily from the Asian, African and Middle East regions” [31].

Skin-whitening products are particularly popular in Asian countries (India, China, Japan, and Korea). In fact, with a naturally higher skin hydration level, Asian skin is particularly prone to suffer from hyperpigmentation or hypopigmentation disorders, and to display general unevenness of skin tone with age rather than wrinkles. The wish to mimic Westerners also impels Asian people to practice skin whitening.

In Africa, voluntary depigmentation is performed for multiple reasons (aesthetic, sociological, political, etc.) [32,33,34]. Hence, the intensive use of whitening agents constitutes a real public health risk and can lead to severe pathologies including burns, acne, stretch marks, hypopigmentation, and even cancer [23,35]. Furthermore, it is important to underline that those whitening treatments are often very long-term ones, and their use over weeks or months produces results that are generally not definite [23].

1.2. Melanogenesis

1.2.1. Mechanism

Melanogenesis is the physiological process of producing melanin, the light-absorbing pigment that is responsible for the human skin and hair coloration, together with three other biochromes [32]. The melanogenesis pathway was first elucidated by Raper in 1928 and later revised [36,37,38,39]. It takes place in melanosomes, membrane-bound organelles located inside the melanocytes from the epidermis’ basal layer, also known as the stratum basale [19,40]. Melanocytes constitute the second most important dermis’ cell lineage after keratinocytes themselves, representing 80% of the epidermis. Once the melanin is produced, melanocytes transport the melanosomes that have lost their tyrosinase activity along their dendrites to reach the neighboring keratinocytes [34,41]. The keratinocytes are dispersed regularly and almost exclusively in the basal epidermis layer. The association of a melanocyte with 30–40 keratinocytes constitutes the epidermal unit where further reactions take place [42,43].

Melanin then accumulates in keratinocytes, where it ensures its photocarcinogenesis preventive role [44]. In fact, this pigment’s biosynthesis plays a crucial role in skin protection by shielding it from sunlight damage (UV radiation absorption) and ion accumulation, as well as by reactive oxygen species (ROS) trapping [45,46,47,48]. Oxidative stress, a direct consequence of the environment (UV radiation, pollution, etc.) and human lifestyle (cigarette smoking, etc.), is implied in skin pathogenesis and leads to alterations in connective tissues and to the formation of lipid peroxides and ROS harmful to the skin, hence leading to accelerated ageing [49,50,51,52].

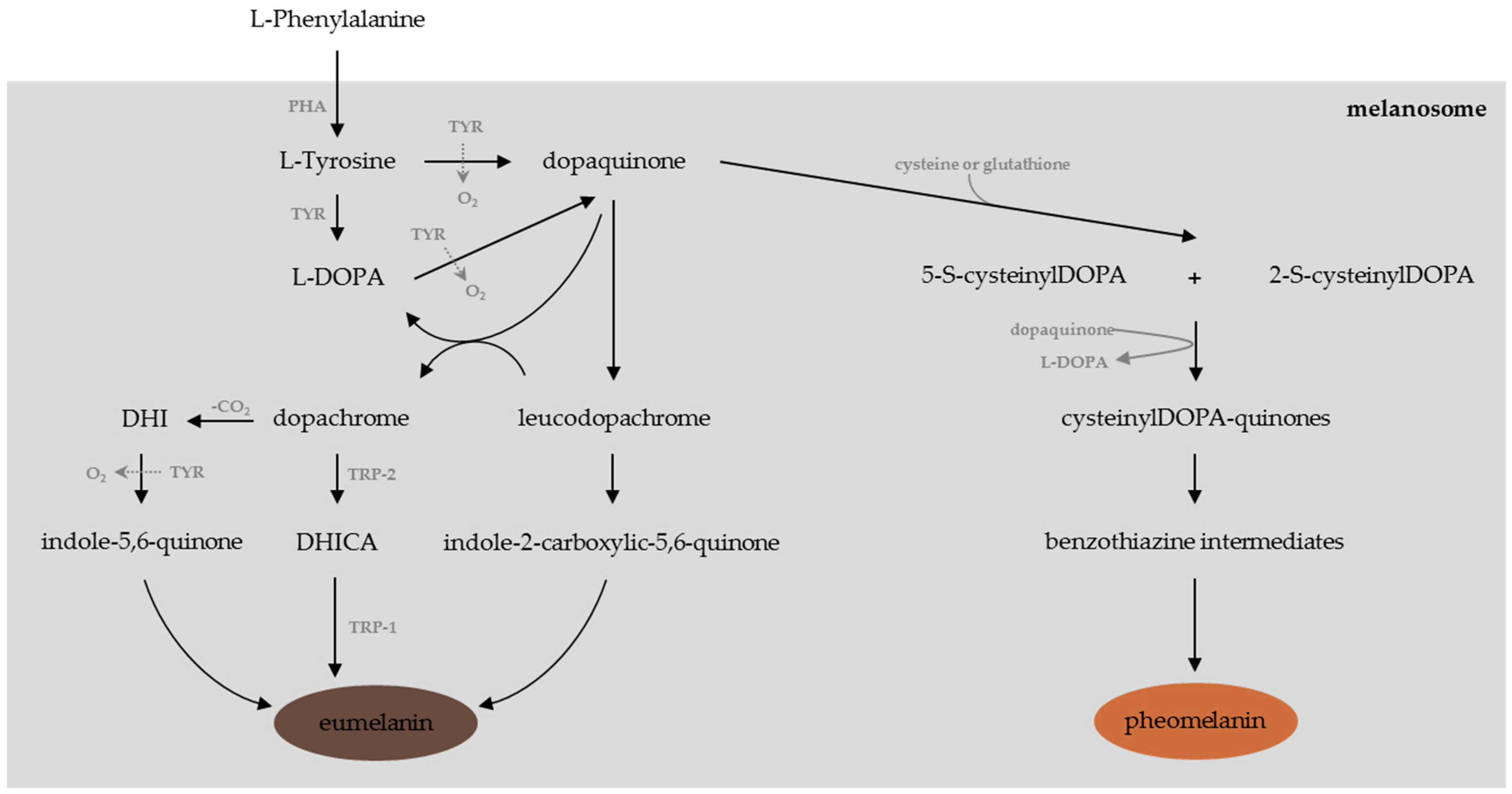

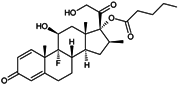

Melanogenesis is a complex pathway (Figure 1) regulated by several enzymes including tyrosinase, phenylalanine hydroxylase (PHA), and tyrosinase-related proteins (TRP-1 and TRP-2) [53]. Tyrosinase, a glycosylated copper-containing polyphenol oxidase, is the key enzyme involved in the melanogenesis pathway. Tyrosinase is mainly involved in the initial rate-limiting reactions in melanogenesis, e.g., the hydroxylation of l-Tyrosine (monophenolase activity) to l-3,4-dihydroxy-phenylalanine (l-DOPA) and its further oxidation (diphenolase activity) to give l-dopaquinone [54,55]. From l-dopaquinone synthesis, the melanin biosynthesis diverges into two pathways [56,57]:

- If cysteine or gluthatione is present, l-dopaquinone interacts with the amino acid to form cysteinyl-DOPA or glutathionyl-DOPA [11,58], subsequently converted and polymerized into pheomelanins, the yellow to red pigments implied in ion trapping [59,60].

- In the absence of cysteine or gluthatione, one can observe the non-enzymatic cyclisation of l-DOPA into leucoDOPAchrome. This compound is further oxidized into dopachrome, the precursor of dihydroindole (DHI) and dihydroindole-2-carboxylic acid (DHICA), which leads through a series of oxidation reactions to the synthesis of UV-protective and ROS-scavenger eumelanins, which are brown or black pigments [11,60,61,62].

Figure 1.

The melanogenesis pathway (adapted from [14,53]).

The quantity and relative amounts of eumelanin and pheomelanin are responsible for the constitutive skin pigmentation [63]. Hence, the difference between lightly and darkly pigmented individuals is due to the melanocytes’ level of activity, a hormonally controlled process, and leads to six distinct skin phototypes, defined by the Fitzpatrick scale in 1975 [64,65]. People with darker skin are consequently genetically programmed to constantly produce higher levels of melanin [66].

Melanogenesis alterations may be responsible for various skin disorders causing both aesthetic problems and dermatological issues [55,67]. Hyperpigmentation phenomenon such as senile lentigo, post-inflammatory melanoderma, melasma, pigmented freckles, and acne scars are characterized by the darkening of a skin area caused by the overproduction of melanin. Relatively common and usually harmless, hyperpigmentation is linked both to external (UV radiation, medicines such as antibiotics, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, psychotropic drugs, pain killers, birth control pills, etc.) and internal (hormones, inflammation, etc.) factors [23,68]. Hypopigmentation, on the contrary, corresponds to the loss of skin color, caused by melanocyte or melanin depletion, or a decrease in the amino acid l-Tyrosine used to produce melanin.

1.2.2. Multidirectional Approaches to Modulating Skin Pigmentation

Any of these melanogenesis steps, whether chemically or enzymatically catalyzed, can be inhibited. Several approaches have been used to find chemicals that inhibit the catalytic activity of tyrosinase and disrupt the synthesis and release of melanin. One can distinguish true tyrosinase inhibitors that reversibly bind to the enzyme, from tyrosinase inactivators, e.g., compounds forming covalent bonds with the enzyme, thus leading to its irreversible inactivation [11]. Hence, tyrosinase inhibition (by tyrosinase blockers) is still the most common strategy adopted to achieve skin whitening, but agents acting upstream or downstream also exist [53,69,70,71]:

- inhibitors of tyrosinase mRNA transcription [11,69,71],

- modulators of tyrosinase glycosylation and maturation or acceleration of its degradation [11],

- inhibitors of the α-MSH (α-melanocyte-stimulating hormone)/cAMP (cyclic adenosine monophosphate)-dependent signaling pathway and the subsequent α-MSH-induced melanin production [53],

- modulators of the mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPK) signaling pathway [53],

- modulators of the Wnt signaling pathway [53],

- inhibitors of the NO (nitric oxide) signaling pathway [53],

- regulators/inhibitors of MITF (microphthalmia-associated transcription factor) involved in the regulation of the development of many cell lineages including melanocytes [19,72],

- regulators of the formation and transfer of melanosomes [11,73],

- ATP7A (also known as Menkes’ protein or MNK) trafficking inhibitors [53],

- down-regulators of MC1R (melanocortin 1 receptor) activity [19],

- inducers of autophagy, a cellular degradation process that affects skin color by regulation of melanin degradation in normal human epidermal keratinocytes [74].

The most successful whitening treatments stake on synergy and usually combine two or more complementary modes of action [19].

1.2.3. Testing the Whitening Potential of a Given Substance

The whitening potency of a given substance or extract may be assessed by several methodologies ranging from in vitro experiments to in vivo and clinical studies. All these procedures have their own advantages and disadvantages, and may sometimes lead to false positives and false negatives:

- in vitro assays constitute the first method to rapidly identify individual components or potentially active extracts. They are used to evaluate the tyrosinase or TRP-2 inhibition potency of single molecules or natural extracts.In vitro screening is usually performed using mushroom tyrosinase, generally purified from Agaricus bisporus (cheap and easily available) according to a protocol adapted from methods described earlier [75,76,77]; extrapolation to humans might be difficult. Only a few bioassays were actually performed using monomeric human tyrosinase, which is hard to purify as it is membrane-bound rather than cytosolic like its tetrameric mushroom counterpart [78]; also commercially available, it is seldom used as it remains quite expensive. However, the use of mammalian tyrosinase should be considered rather than the mushroom one for in vitro assays, as the inhibitors’ affinity for the mammalian one is generally lower than for the mushroom one [79]. Hence, numerous “false positives,” e.g., extracts or single molecules that are active inhibitors of mushroom tyrosinase but are inefficient once in contact with mammalian tyrosinase, might be avoided [23,80]. Recently, some studies were nevertheless performed using crude extracts of human melanocytes as the enzyme source [11].Tyrosinase activity is determined spectrophotometrically: the increase in absorption due to the DOPAchrome formation is recorded at 475–480 nm as a function of time. High-throughput screening can be performed using in vitro protocols at a reasonable cost as the assays can be realized in 96-well plates and the procedure can be totally automated. The results are either expressed as inhibition percentages or as inhibition concentration (IC50), in comparison with a positive control, generally kojic acid, but also Glycyrrhiza glabra or Morus alba extracts. The notion of “Relative Inhibitory Activity” (RA) has been introduced recently to facilitate the direct comparison of inhibitors described in various studies. RA is obtained by dividing the IC50 of the positive control by that of the inhibitor of interest [11].The DOPAchrome tautomerase, also known as tyrosinase-related protein 2 (TRP-2), presents a cellular distribution in the melanocytes quite similar to tyrosinase [81]. This enzyme is strongly involved in the regulation of the eumelanin synthesis, a late step in melanogenesis [82]. Some inhibitors have already been identified, e.g., N-(3,5-dimethylphenyl)-3-methoxybenzamide [83] and Neolitsea aciculata extract [84]. Further identification of TRP-2 inhibitors appears to be crucial, and a bioassay consisting of spectrophotometrical monitoring at 308 nm of the absorbance increase due to the TRP-2 controlled tautomerization of DOPAchrome to DHICA as a function of time has been developed [85].

- in cellulo and ex vivo assays: The whitening potency of a substance of interest can be appraised by the spectrophotometrical monitoring of the intracellular tyrosinase activity or of the intracellular melanin production after cell extraction. Several protocols have been developed depending on the cell lineage employed, the culture conditions, and the method employed to evaluate the inhibition activity [86,87,88].The evaluation of cellular MITF expression enables the identification of whitening substances that do not, or only at a very low level, display tyrosinase activity [69,89].Cultures of melanocytes may be used to assess the whitening properties of single molecules or natural extracts as they closely mimic physiologic conditions. They enable the study of the global effect of such agents on the melanin synthesis in melanocytes. However, melanocytes are difficult to maintain in culture. Hence this method, being complex and expensive, is usually not appropriate to confirm the activity of compounds the whitening activity of which was already assessed in vitro.Cultures of B16 melanoma cells, models for human skin cancers, are frequently used for the study of whitening potency [78]. However, one should bear in mind that cancerous cell lines display, owing to their nature, several abnormal functions and subsequently do not accurately mimic reality.Co-cultures of melanocytes and keratinocytes even more narrowly reproduce the in vivo situation and enable us to have a closer look at the interaction between both types of cells in the melanization epidermal unit and at the melanosomes transfer [90]. However, these systems are expensive and their implementation is difficult.Skin explants sampled from volunteers or stemming from surgical waste, as well as commercially available skin equivalent models (SEM) constituted of human epidermal cells, may be preferred for in vitro systems for testing skin whitening substances [88,91,92].

- in vivo assays and clinical trials: Mammalian skin is generally preferred to evaluate the efficacy and innocuousness of a given substance [93]: several animal models, more reliable than in vitro tests, have been used, e.g., the mouse [92,94], the zebrafish [94,95,96], the guinea pig [97,98], and the Yucatan swine [99,100]. The zebrafish presents several advantages, including easy maintenance and handling of the animals, short generation times, and high efficiency of drug penetration through the skin [96,101,102]. Relatively small, easily maintained, and displaying rather short generation times, mice are used to more closely approximate human reactions as their skin is more comparable to human skin than that of zebrafish [102]. Shaved mice present even higher drug penetration compared to non-shaved ones [102]. In contrast to mice, the epidermis of guinea pigs displays a moderate number of melanocytes and melanosomes distributed in a similar way to human skin [103]. Given the close morphologic and functional similarities between pig and human skins (similar epidermis thickness, similar epidermal cells turnover time, etc.), the effectiveness of depigmenting agents was also often evaluated in Yucatan miniature swine [99,100,104,105,106]. More complete studies taking into account the quantification of melanin production, the evaluation of the expression of cellular factors and tyrosinase, etc., may thus be undertaken in such robust integrative experimental models. It is important to remember that experimentation on animals to test cosmetic ingredients and finished cosmetics has been banned in the EU as well as in numerous countries throughout the world [23]. On the contrary, animal experimentation is still practiced by the pharmaceutical industry: dermatological whitening agents delivered only under medical prescription are tested for safety, efficacy, and liability on animal models before they are considered for widespread human use.

Finally, the whitening activity of a given substance may be appraised by clinical trials. Depigmentation of already existing hyperpigmented spots (such as freckles and lentigos) or of UV- or exogenous α-MSH-induced hyperpigmentated areas may be evaluated visually by experts using color charts such as the Munsell one [107] or measured with cutaneous colorimeters [108,109]. Results in both cases depend on the nature and size of the analyzed skin zone; furthermore, after the visual observation, being by nature quite subjective, one can only recommend the simultaneous use of both methods [23,110].

1.3. Traditional Whitening Products

Several chemicals have been shown to achieve pigmentation clearance and have been frequently used in whitening cosmetics. Whitening products may act both upstream and downstream of the melanin synthesis, but the majority interfere directly with one of the melanogenesis reactions (Table 1).

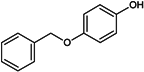

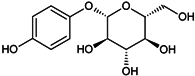

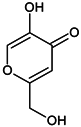

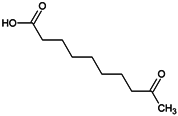

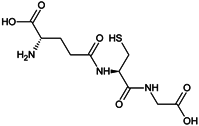

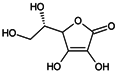

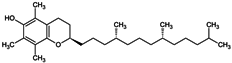

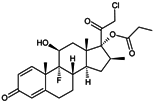

Table 1.

Chemical structures and modes of action of the main skin-whitening substances traditionally used in whitening cosmetics.

1.4. Current Regulations

However, over the last decade, some of these whitening agents have proven to be toxic or to have questionable safety profiles over long-term exposure. Depending on the type of substance applied and the method of application, adverse reactions ranging from dermatological complications (for example, burning, itching, or ochronosis), face lesions, stretch marks, excessive body odor, steroid addiction, and periorbital hyperchromia to chronic kidney disease have been reported [23,129,130,131,132,133]. Hypopigmentation resulting from the use of whitening agents leaves the skin sensitive and more prone to UV-induced damage, and, in the long term, to melanoma. Increasingly facing the phenomenon of these voluntary practices and the subsequent health risks to which users have exposed themselves, Afssaps (Agence Française de Sécurité Sanitaire des Produits de Santé, France) and the DGCCRF (Direction Générale de la Concurrence, de la Consommation et de la Répression des Fraudes, France) formed a national campaign to control these products’ market in 2009 and in 2010 [134]. A list of non-conforming or dangerous skin-whitening products was subsequently established [135]. Most recently, a decision emanated from the ANSM (Agence Nationale de Sécurité du Médicament, France) to suspend the commercial launch of injectable whitening products (for intradermal, subcutaneous, intramuscular, or intravenous injection) sold on the Internet under various names [136]. A similar measure was already taken by the FDA (Food Drug Administration) in 2015 [137], as such products can contain harmful substances such as glutathione or EGF (Epidermal Growth Factor).

Due to their assessed adverse effects, some of these substances have been banned recently by the EU Cosmetic Regulation 1223/2009 [32,138] applied in the European Economic Area (EEA), i.e., all 28 EU Member States plus Iceland, Liechtenstein, and Norway.

The presence of retinoids in cosmetics can lead to burning, tingling, dryness, exfoliation, and desquamation. In 2015, the ANSM contra-indicated their use during pregnancy because of their strong teratogenic potency [139]. In addition, the presence of retinoic acid and its salts in cosmetics has been prohibited in EU countries [138].

The use of hydroquinone has lately been banned in all European countries because of concerns regarding its possible association with carcinogenesis [138]. Several other countries have limited the amount of hydroquinone allowed in cosmetic products. Its glycosylated counterpart, β-arbutin, may under some environmental conditions, carry similar cancer risks [140]: in fact, in acidic conditions, this substance easily hydrolyzes into hydroquinone. However, the SCCS (Scientific Committee on Consumer Safety) consider the occurrence of β-arbutin in a concentration up to 7% in face creams as safe, provided that the concentration of hydroquinone in the cosmetics remains below 1 ppm [141].

Mercury-containing products are hazardous and have been banned in most countries (since 1976 in Europe and since 1990 in the USA): accumulation of this heavy metal may lead to chronic complications including mercurialentis, photophobia, irritability, muscle weakness, and nephrotoxicity [32,133,142,143,144,145]. Mercury poisoning is also observed in newborns as the metal is easily conveyed via the placenta and breastmilk [146,147]. Furthermore, long-term application of mercurial derivatives has adverse effects such as mercury accumulation darkening the skin and nails. However, the use of some mercury salts as preservatives (thiomersal, phenylmercury salts) is still authorized.

Other substances that are still authorized should be used cautiously. Oral intake of glutathione has, for example, been reported to have dangerous effects when combined with other skin-whitening agents such as hydroquinone. Care should also be taken after AHA treatment: the skin should be neutralized after the application of AHA, as it might cause burning and erythema [19]. For this reason, their concentration should not exceed 10% (m/m) in the finished product, with a final pH of the formulation not lower than 3.5. Moreover, corticosteroid-containing creams, diverted from their prime usage (e.g., anti-inflammatory), lead to severe adverse effects, ranging from irreversible stretch marks and epidermal thinning to neuropathy and steroid addiction [2,148]. Furthermore, some research has suggested that kojic acid may cause allergic contact dermatitis and skin irritation, and even cancer in large doses [149]. However, the SCCS declared 1% kojic acid safe in cosmetics [141].

Outside the EU, the severity of cosmetic regulations is quite heterogeneous, so these agents’ status remains uncertain: they may have been banned in some countries, whereas their presence is still authorized in skin-lightening cosmetic formulations in other countries. Those substances may also still be used under strict dermatological supervision. Thus, the presence of hydroquinone, kojic acid, or azelaic acid is totally prohibited in cosmetic formulations by Swiss legislation, whereas hydroquinone is still authorized in the USA, where it is sold as an over-the-counter drug (concentration of hydroquinone not exceeding 2%), and products containing β-arbutin or plants that naturally contain hydroquinone and β-arbutin continue to remain available in European countries [132,150,151]. Moreover, numerous Asian and African countries have yet to legislate about the safety status of such substances [23].

Hence the downward slide observed recently: the presence of illegal products (especially hydroquinone, corticosteroids, and tretinoin) on the black market, and subsequent health issues deriving from their use [32,148]. In fact, such products are usually manufactured abroad, where their usage is still legal or where there is a juridical void concerning their use, and sold illegally in the country. Consumers may also have bought them online, a generalized tendency leading to self-medication and all its underlying dangers.

Considering this and the growing consumer interest in more natural cosmetics, one can observe a boom in development over the last decade of natural hypopigmenting ingredients that have been proven to be safe and effective supplements for the treatment of certain dermatological disorders in humans.

2. Development of Natural Whitening Ingredients

2.1. State of the Art

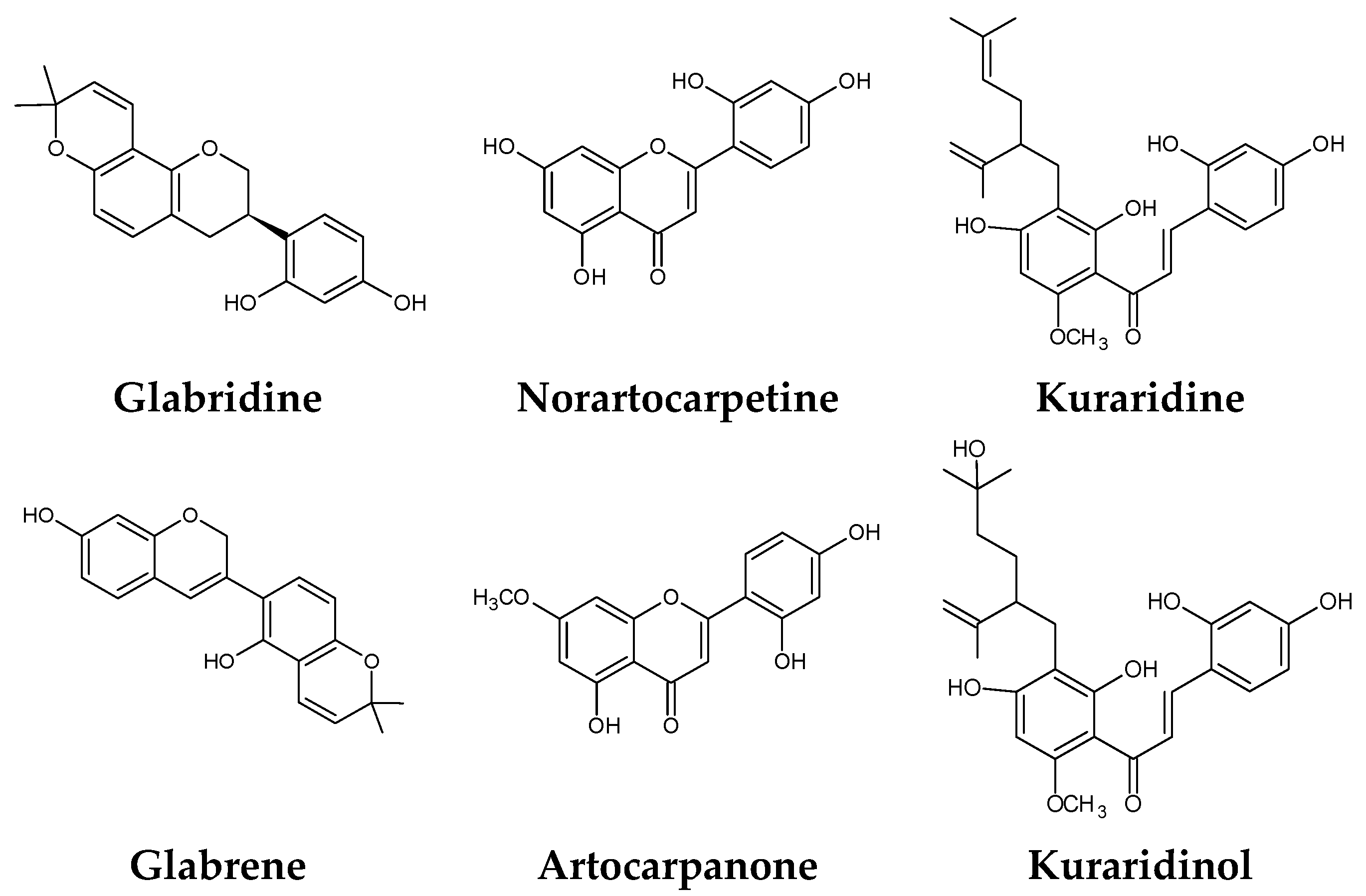

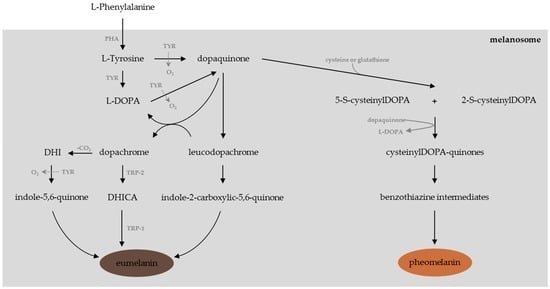

The search for natural melanogenesis inhibitors in recent years has demonstrated that plant extracts could be potential sources of new whitening ingredients as potent as synthetic whitening agents but not associated with cytotoxicity or mutagenicity (Figure 2) [19,55,67,152]. Classification of these whitening components, based on their structure and the mechanism by which they interfere with melanogenesis, is difficult, notably because of their huge number, the fact that some of them act at several levels, and the variety of tests used to assess their whitening potency [79].

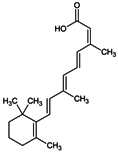

Figure 2.

Some natural whitening agents.

Nevertheless, one can distinguish families of compounds that are particularly active. Hence a notable number of phenolic compounds have demonstrated good tyrosinase inhibition [11,12,13,14,15,153,154]. Flavonols have been identified as competitive tyrosinase inhibitors thanks to their ability to chelate the copper from the enzyme’s active site, leading to the enzyme’s irreversible inactivation [120,155]; however these compounds are still less active than kojic acid. Flavones, flavanones, and flavanols are also weak inhibitors of tyrosinase activity [23]. Aloesin, a coumarin-type component isolated from Aloe vera and reported to modulate melanogenesis, is frequently incorporated into topically applied cosmetic formulations [156,157]. Anthraquinones from several natural sources display similar or higher tyrosinase inhibition potencies compared to kojic acid [158,159].

Some botanic ingredients combining two or more classes of active molecules that work in synergy have also been identified as potent tyrosinase inhibitors; the most frequently cited is licorice (Glycyrrhiza glabra roots), which mainly contains isoflavonoids and chalcones as actives components [77,160]. Origanum vulgare (whitening agent: origanoside, a glycosylated phenolic compound) and Scutelleria baicalensis (whitening agent: baicalein, a flavone) extracts, as well as Morus (containing chalcones and stilbenoids) and Citrus (containing flavones, flavanones, and flavanols) species extracts also display interesting whitening properties [12,14,15,19,161,162,163,164,165,166,167]. It was proven that oral intake for one year of pro-anthocyanidin-rich extract from grape seeds (Vitis vinifera) reduced the hyperpigmentation of women suffering chloasma [43]. Benzaldehyde and benzoate derivatives such as anisaldehyde, cuminaldehyde, and hydroxycinnamic acid derivatives have been identified as potent tyrosinase inhibitors [168,169]. Similarly, some authors have demonstrated that triterpenoids isolated from Amberboa ramose and Rhododendron collettianum are able to inhibit tyrosinase’s diphenolase activity [170,171].

Some natural extracts interfering with melanosomes’ maturation and/or transfer have been identified [119]: Glycine max [172], Achillea millefolium [173,174], and Ophiopogon japonicas [174].

Marine sources—algae, marine fungi, and bacteria—of tyrosinase inhibitors have also been explored and led to the identification of some interesting trails [16,18,175].

However, at the moment only a few of these interesting molecules or ingredients have been incorporated into skin-whitening formulations due to a lack of in vivo assays and especially clinical trials to attest to their efficacy and safety [4,11].

2.2. Lab Reality: Our Experience

A systematic screening of plant extracts was undertaken in our laboratory over a three-year period to evaluate their whitening activity for potential application in cosmetology. Such a large-scale assessment proved to be a frustrating task as only a few extracts actually present promising activity.

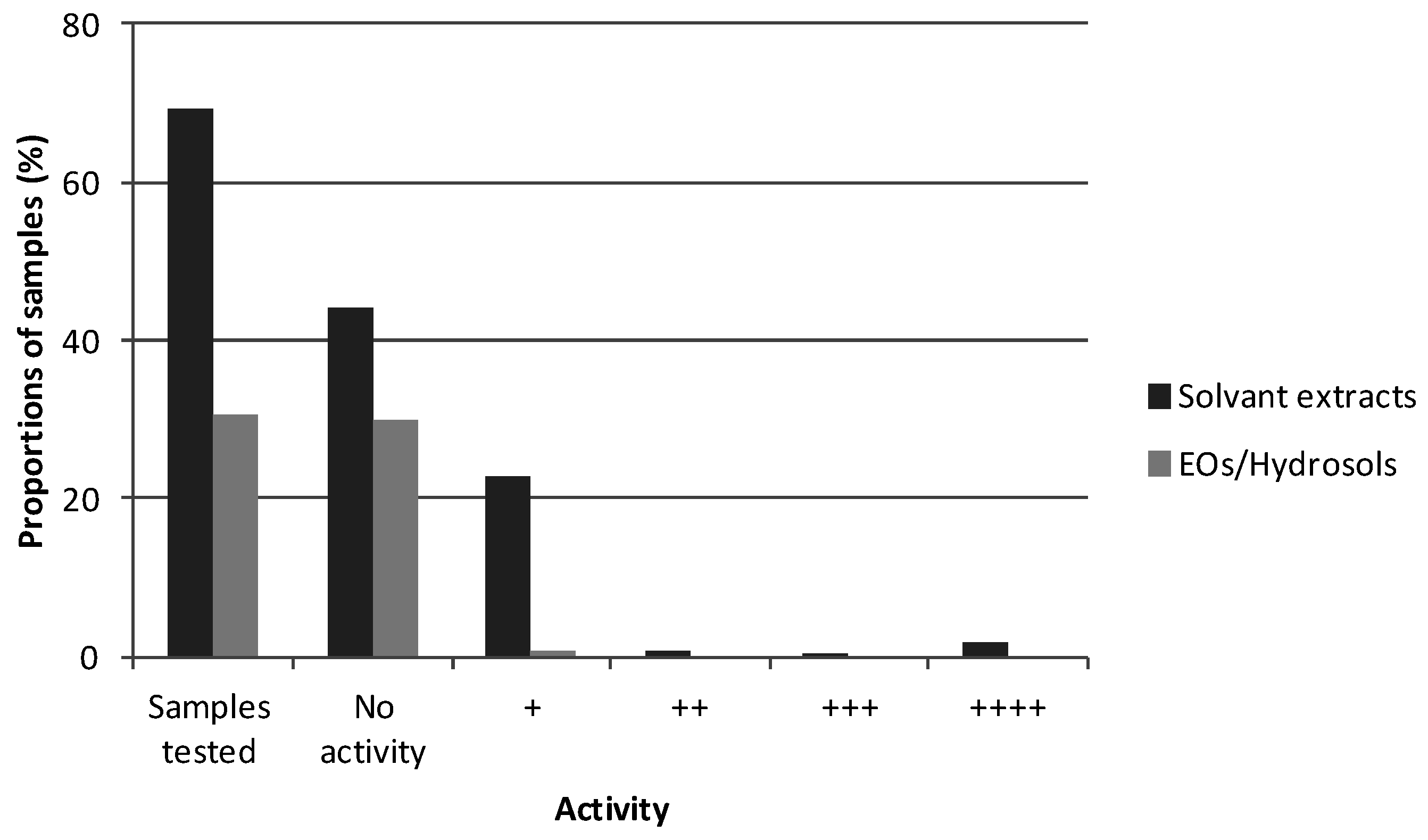

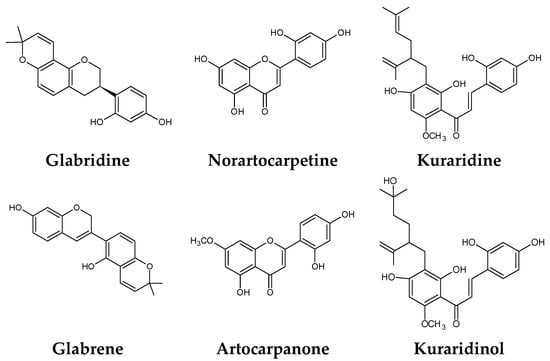

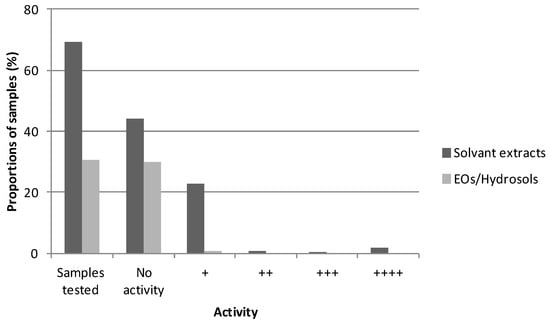

The inhibitory effect of a total of 350 plant extracts was assessed on mushroom tyrosinase activity by enzymatic assays, using either l-Tyrosine or l-DOPA. The sample’s final concentration per well—100 µg/mL—was chosen after a thorough literature survey. Essential oils (EOs) and hydrosols obtained by distillation on one hand and solvent extracts (hexane, ethyl acetate, ethanol, etc.) on the other hand were assayed for their inhibition potency on both the mono- (Figure 3) and diphenolase (data not shown) activities of mushroom tyrosinase. Samples were analyzed in triplicate in 96-well plates and reference standard solutions of kojic acid were used to verify the effectiveness of the tests. The kojic acid inhibition systematically ranged from 91% to 99% in the assays when the monophenolase activity was tested and from 68% to 85% when the diphenolase activity was tested. In total, 36.2% of the solvent extracts tested presented some whitening activity (regardless of the tyrosinase inhibition intensity). Among the six extracts presenting inhibition higher than 80%, three were obtained using ethyl acetate and two were obtained using ethanol (Figure 2). These observations might be explained by the fact that polar solvents, and notably ethanol, are appropriate for polyphenol and flavonoid-potent tyrosinase inhibitor extraction from plant matrices. The sixth was obtained from the same plant as one of the active ethyl acetate extracts, using hexane. However, it should be pointed out that hexane is not compatible with cosmetic use and its usage for the extraction of cosmetic ingredients may even be banned as residual traces might be present in the finished product. For any further development of such an ingredient to take place, the extraction procedure will have to be redesigned.

Figure 3.

Proportions of samples (%) tested in triplicate and presenting whitening activity (++++: 80% ≤ tyrosinase inhibition ≤ 100%; +++: 60% ≤ inhibition ≤ 80%; ++: 40% ≤ inhibition ≤ 60%; +: 20% ≤ inhibition ≤ 40%; positive control = kojic acid).

By comparison, even fewer EOs/hydrosols (1.8%) display some whitening potency (no inhibition higher than 20%). This might be due to the compounds present in these types of extracts (mainly mono- and sesquiterpenes). This observation already shows through the literature survey: compared to solvent extracts, only a few studies report the tyrosinase inhibition and/or anti-melanogenic effects of such extracts or of individual EOs’ constituents [87,166,176,177,178,179,180,181]. Single components, mainly acting as alternative substrates to l-Tyrosine and l-DOPA (eugenol, thymol, etc.), have been proven to be quite effective [177]. Nevertheless, the overall composition of the EO influences its bioactivity via synergism/antagonism and might be the reason for such poor screening results. Those results might also be linked to the fact that the numerous molecules constituting these EOs might be more or less soluble in DMSO.

2.3. Further Development of a Cosmetic Ingredient

Notwithstanding, it is important to keep in mind that such a screening constitutes only the first step in the development of a whitening ingredient dedicated to cosmetic or dermatological formulations. In fact, the further development and use of such a natural whitening ingredient is still a long-term undertaking as “roughly only 5 in every 100 genetic resources identified as being potentially of interest will ever end up in cosmetic and personal care formulas as they also have to pass all the efficacy, quality and safety tests right throughout the development chain” [182].

In fact, once the bioactivity of an extract is assessed, the isolation and structural characterization of the active constituents are of great interest. Hence, molecules modulating the metabolism of pigmentation have to be targeted and identified using either semi-preparative HPLC or flash chromatography fractionation, associated with further activity evaluation in 96-well plates. The initial goal of such an experimental procedure is to bring out the most active fractions in order to correlate their bioactivities to the molecules or families of molecules they are made of. The proper isolation of those molecules of interest can occur in a second time.

One should also keep in mind that such a high-throughput screening is performed using mushroom tyrosinase. As already stated, human tyrosinase is hard to purify and quite expensive but the hits identified previously should be retested using such an enzyme or at least using crude extracts of human melanocytes as the enzyme source in order to confirm that the activity is transposable to humans.

The clinical efficacy of the single molecule or the extract’s fraction of interest has then to be assessed, and its efficacy and safety need to be validated. Its toxicological innocuousness has to be evaluated as well. Tests can be performed on artificial skin, but skin cell viability tests, e.g., cytotoxicity assays, are usually performed on human keratinocytes or melanocytes [183,184,185]. Skin irritancy testing is usually performed on human keratinocytes [186]; human repeat insult patch testing (HRIPT, repeated applications of products on the skin, under an occlusive patch, in healthy adult volunteers) has also been developed to assess the dermal irritation or sensitization potency of a molecule. In vivo toxicity assays can be performed in zebrafish or mice [187].

The ingredient, once elaborated, may still be unstable, may display offensive color and/or odor unacceptable in skin care products, or may not be compatible with the developed cosmetic formulations [10,19]. Other parameters such as cutaneous absorption and penetration of the agents should also be considered.

Another major pitfall in the development of such whitening ingredients is the question of sourcing and all the underlying economic and legislative issues. A plant has to be accessible in quantities that allow a reasonable price and are in accord with current legislation, notably the Nagoya protocol requiring, among other things, the sustainable use of biodiversity resources [188].

3. Materials and Methods

All the chemicals were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Quentin Fallavier, France) unless otherwise stated. Untreated 96-well plates were obtained from Thermo Nunc (Illkirch, France). The extracts (EOs, hydrosols, and solvent extracts) tested for whitening activity were obtained using several protocols and, as only preliminary results are presented, those protocols are not detailed in the present paper. During incubation, the 96-well plates were sealed with adhesive films (Greiner Bio-One, Les Ulis, France). Samples for biological activity testing were prepared in 1.5-mL Eppendorf tubes, appropriate for the use of the automated pipetting system epMotion® 5075 (Eppendorf, Montesson, France). Absorbance measurements were performed using a microplate reader (Spectramax Plus 384, Molecular Devices, Wokingham, Berkshire, UK). Data were acquired with the SoftMaxPro software (Molecular Devices, Wokingham, Berkshire, UK) and inhibition percentages were calculated with the Prism software (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, California, USA). The results are presented as inhibition percentages (%), calculated as follows:

I% = [(OD control − OD sample)/OD control] × 100 (with OD stating for optical density).

Similarly, all OD values were corrected with the blank measurement corresponding to the absorbance of the sample before addition of the substrate, unless otherwise stated.

The assays were performed in 96-well plates as follows: 150 µL of a solution of mushroom tyrosinase prepared at a concentration of 171.66 U/mL in phosphate buffer (100 mM pH = 6.8) are distributed in each well (final enzyme concentration per well: 100 U/mL), together with 7.5 µL of samples diluted at a concentration of 3.433 mg/mL in DMSO (final sample concentration per well: 100 µg/mL). Kojic acid (3.433 mM in DMSO) was used as the positive control; DMSO alone was used as the negative control (OD control).

The plate is filmed and incubated at RT for 20 min. Then, 100 µL of a solution of l-Tyrosine 1 mM in phosphate buffer (pH = 6.8; final l-Tyrosine concentration per well: 0.388 mM) were distributed in each well. After 20 min of incubation, OD reading was performed at 480 nm to assess the percentage of inhibition.

4. Conclusions

Lightening/whitening cosmetics are largely represented in the global cosmetics landscape. Mainly used to alleviate hyperpigmentation problems in Europe and North America, they are mostly popular in Africa and Asia for cosmetic purposes. This quest for whiter skin can lead to major health issues, largely due to the use in high concentrations of very aggressive compounds, some of which have been progressively banned by the European Cosmetic Regulations. Regarding the adverse effects of many of those traditional whitening products, consumers await safer and more effective preparations for lightening and/or depigmenting skin.

Persistent research into skin lightening has recently led to the identification of a number of whitening agents originating from biological sources (plants, fungus, bacteria, and algae) [11,12,13,14,15,16,18,175,189]. From our own results, it appears clear that some plant extracts are able to inhibit melanogenesis at least in vitro, hence suggesting their whitening potential as single ingredients. However, the bioactivity of many of these compounds/botanic extracts (either cited in the literature or identified in our laboratory) has yet to be screened via in vivo assays and their efficacy and adverse effects need to be established through clinical trials before a cosmetic formulation can be considered [19]. The success of whitening treatments may lie in the combination of two or more active ingredients that may be eventually effective at different levels of melanogenesis to achieve a synergistic effect [2].

Natale et al. (2016) have recently proved that estrogen and progesterone reciprocally regulate melanin synthesis via membrane-bound receptors such as G protein-coupled estrogen receptor (GPER), and as progestin and adipoQ receptor 7 (PAQR7), discovered on melanocytes [190]. Those receptors are activated or inhibited by progesterone or estrogen to lighten or darken the skin, respectively: future pigmentation controling cosmetics could capitalize on this concept.

The effectiveness of physical approaches to lightening the skin tone, including liquid nitrogen cryotherapy, laser surgery, and superficial dermabrasion, has also been investigated in recent years, prompted by the drawbacks of the chemical agents discussed previously [191,192,193,194,195]. One can hence imagine that therapies combining chemical and physical approaches, producing a synergetic hypopigmenting effect, might offer new opportunities in the search for skin tone control.

Finally, it must be concluded that given the underlying recognized or yet-to-be proven safety issues linked to the use of whitening agents, prevention, e.g., the use of sunscreen products, is still the most effective and universal weapon to prevent hyperpigmentation [2].

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Cécile Becquart and Sofia Barreales Suarez for the development of the tyrosinase assays.

Author Contributions

Xavier Fernandez, Thomas Michel, and Stéphane Azoulay conceived and designed the experiments; Pauline Burger, Anne Landreau, Thomas Michel and Stéphane Azoulay performed the experiments and analyzed the data; Pauline Burger and Anne Landreau wrote the article and all the authors equally contributed to its revision.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Naidoo, L.; Khoza, N.; Dlova, N.C. A fairer face, a fairer tomorrow? A review of skin lighteners. Cosmetics 2016, 3, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Couteau, C.; Coiffard, L. Overview of skin whitening agents: Drugs and cosmetic products. Cosmetics 2016, 3, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimes, P.; Nordlund, J.J.; Pandya, A.G.; Taylor, S.; Rendon, M.; Ortonne, J.-P. Increasing our understanding of pigmentary disorders. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2006, 54, S255–S261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, W.; Gao, J. The use of botanical extracts as topical skin-lightening agents for the improvement of skin pigmentation disorders. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2008, 13, 20–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chou, T.-H.; Ding, H.-Y.; Hung, W.J.; Liang, C.-H. Antioxidative characteristics and inhibition of alpha-melanocyte-stimulating hormone-stimulated melanogenesis of vanillin and vanillic acid from Origanum vulgare. Exp. Dermatol. 2010, 19, 742–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yokozawa, T.; Kim, Y.J. Piceatannol inhibits melanogenesis by its antioxidative actions. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2007, 30, 2007–2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, H.J.; Lee, W.J.; Chang, S.E.; Lee, G.-Y. Hesperidin, a popular antioxidant inhibits melanogenesis via Erk1/2 mediated MITF degradation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2015, 16, 18384–18395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iwai, K.; Kishimoto, N.; Kakino, Y.; Mochida, K.; Fujita, T. In vitro antioxidative effects and tyrosinase inhibitory activities of seven hydroxycinnamoyl derivatives in green coffee beans. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2004, 52, 4893–4898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, F.; Li, W.; Huang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Jin, B.; Chen, N.; Ding, Z.; Ding, X. Antioxidant, antityrosinase and antitumor activity comparison: The potential utilization of fibrous root part of Bletilla striata (Thunb.) Reichb.f. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e58004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kerdudo, A.; Burger, P.; Merck, F.; Dingas, A.; Rolland, Y.; Michel, T.; Fernandez, X. Development of a natural ingredient—Natural preservative: A case study. C. R. Chim. 2016, 19, 1077–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, T.-S. An updated review of tyrosinase inhibitors. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2009, 10, 2440–2475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, H.; Nishida, J.; Saito, S.; Kawabata, J. Inhibitory effects of 5,6,7-trihydroxyflavones on tyrosinase. Molecules 2007, 12, 86–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Itoh, K.; Hirata, N.; Masuda, M.; Naruto, S.; Murata, K.; Wakabayashi, K.; Matsuda, H. Inhibitory effects of Citrus hassaku extract and its flavanone glycosides on melanogenesis. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2009, 32, 410–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gillbro, J.M.; Olsson, M.J. The melanogenesis and mechanisms of skin-lightening agents—Existing and new approaches. Int. J. Cosmet. Sci. 2011, 33, 210–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ribeiro, A.S.; Estanqueiro, M.; Oliveira, M.B.; Sousa Lobo, J.M. Main benefits and applicability of plant extracts in skin care products. Cosmetics 2015, 2, 48–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, H.S.; Kim, H.R.; Byun, D.S.; Son, B.W.; Nam, T.J.; Choi, J.S. Tyrosinase inhibitors isolated from the edible brown alga Ecklonia stolonifera. Arch. Pharm. Res. 2004, 27, 1226–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, E.P.H.; Min, H.J.; Belk, R.W.; Kimura, J.; Bahl, S. Skin lightening and beauty in four Asian cultures. Adv. Consum. Res. 2008, 35, 444–449. [Google Scholar]

- Tsuchiya, T.; Yamada, K.; Minoura, K.; Miyamoto, K.; Usami, Y.; Kobayashi, T.; Hamada-Sato, N.; Imada, C.; Tsujibo, H. Purification and determination of the chemical structure of the tyrosinase inhibitor produced by Trichoderma viride strain H1-7 from a marine environment. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2008, 31, 1618–1620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamakshi, R. Fairness via formulations: A review of cosmetic skin-lightening ingredients. J. Cosmet. Sci. 2012, 63, 43–54. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ashikari, M. Cultivating Japanese whiteness: The “whitening” cosmetics boom and the Japanese identity. J. Mater. Cult. 2005, 10, 73–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhri, S.K.; Jain, N.K. History of cosmetics. Asian J. Pharm. 2009, 3, 164. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, R.E. The bleaching syndrome: Western civilization vis-à-vis inferiorized people of color. In The Melanin Millennium; Hall, R.E., Ed.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2013; pp. 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez, X.; Michel, T.; Azoulay, S. Actifs cosmétiques à effet blanchissant—Nature, efficacité et risques. Tech. Ing. 2015, J2300, 33. (In French) [Google Scholar]

- Porta, E.A. Pigments in aging: An overview. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2002, 959, 57–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rendon, M.; Berneburg, M.; Arellano, I.; Picardo, M. Treatment of melasma. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2006, 54, S272–S281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- James, W.D.; Berger, T.; Elston, D. Andrews’ Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology, 12th ed.; Elsevier: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Tunzi, M.; Gray, G.R. Common skin conditions during pregnancy. Am. Fam. Physician 2007, 75, 211–218. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ezzedine, K.; Sheth, V.; Rodrigues, M.; Eleftheriadou, V.; Harris, J.E.; Hamzavi, I.H.; Pandya, A.G. Vitiligo is not a cosmetic disease. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2015, 73, 883–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iannella, G.; Greco, A.; Didona, D.; Didona, B.; Granata, G.; Manno, A.; Pasquariello, B.; Magliulo, G. Vitiligo: Pathogenesis, clinical variants and treatment approaches. Autoimmun. Rev. 2016, 15, 335–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McDougall, A. Skin Whitening Products Have Global Potential IF Marketed Correctly. Available online: http://www.cosmeticsdesign-asia.com/Market-Trends/Skin-whitening-products-have-global-potential-IF-marketed-correctly (accessed on 20 September 2016).

- McDougall, A. Skin Lightening Trend in Asia Boosts Global Market. Available online: http://www.cosmeticsdesign-asia.com/Market-Trends/Skin-lightening-trend-in-Asia-boosts-global-market (accessed on 20 September 2016).

- Desmedt, B.; Courselle, P.; De Beer, J.O.; Rogiers, V.; Grosber, M.; Deconinck, E.; De Paepe, K. Overview of skin whitening agents with an insight into the illegal cosmetic market in Europe. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2016, 30, 943–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kpanake, L.; Mullet, E. Motives for skin bleaching among West Africans. Househ. Pers. Care Today 2011, 6, 6–9. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, R.E. The Melanin Millennium: Skin Color as 21st Century International Discourse; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin, Germany, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- De Souza, M.M. The concept of skin bleaching in Africa and its devastating health implications. Clin. Dermatol. 2008, 26, 27–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raper, H.S. The anaerobic oxidases. Physiol. Rev. 1928, 8, 245–282. [Google Scholar]

- Mason, H.S. The chemistry of melanin. III. Mechanism of the oxidation of trihydroxyphenylalanine by tyrosinase. J. Biol. Chem. 1948, 172, 83–99. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Cooksey, C.J.; Garratt, P.J.; Land, E.J.; Pavel, S.; Ramsden, C.A.; Riley, P.A.; Smit, N.P. Evidence of the indirect formation of the catecholic intermediate substrate responsible for the autoactivation kinetics of tyrosinase. J. Biol. Chem. 1997, 272, 26226–26235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schallreuter, K.U.; Kothari, S.; Chavan, B.; Spencer, J.D. Regulation of melanogenesis—Controversies and new concepts. Exp. Dermatol. 2008, 17, 395–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seiji, M.; Fitzpatrick, T.B.; Birbeck, M.S. The melanosome: A distinctive subcellular particle of mammalian melanocytes and the site of melanogenesis. J. Investig. Dermatol. 1961, 36, 243–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schallreuter, K.; Slominski, A.; Pawelek, J.M.; Jimbow, K.; Gilchrest, B.A. What controls melanogenesis? Exp. Dermatol. 1998, 7, 143–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fitzpatrick, T.B.; Breathnach, A.S. The epidermal melanin unit system. Dermatol. Wochenschr. 1963, 147, 481–489. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Jimbow, K.; Quevedo, W.C.; Fitzpatrick, T.B.; Szabo, G. Some aspects of melanin biology: 1950–1975. J. Investig. Dermatol. 1976, 67, 72–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kobayashi, N.; Nakagawa, A.; Muramatsu, T.; Yamashina, Y.; Shirai, T.; Hashimoto, M.W.; Ishigaki, Y.; Ohnishi, T.; Mori, T. Supranuclear melanin caps reduce ultraviolet induced DNA photoproducts in human epidermis. J. Investig. Dermatol. 1998, 110, 806–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agar, N.; Young, A.R. Melanogenesis: A photoprotective response to DNA damage? Mutat. Res. 2005, 571, 121–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bush, W.D.; Simon, J.D. Quantification of Ca(2+) binding to melanin supports the hypothesis that melanosomes serve a functional role in regulating calcium homeostasis. Pigment Cell Res. 2007, 20, 134–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costin, G.-E.; Hearing, V.J. Human skin pigmentation: Melanocytes modulate skin color in response to stress. Fed. Am. Soc. Exp. Biol. J. 2007, 21, 976–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riley, P.A. Melanin. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 1997, 29, 1235–1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betteridge, D.J. What is oxidative stress? Metabolism 2000, 49, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamakoshi, J.; Sano, A.; Tokutake, S.; Saito, M.; Kikuchi, M.; Kubota, Y.; Kawachi, Y.; Otsuka, F. Oral intake of proanthocyanidin-rich extract from grape seeds improves chloasma. Phytother. Res. 2004, 18, 895–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trouba, K.J.; Hamadeh, H.K.; Amin, R.P.; Germolec, D.R. Oxidative stress and its role in skin disease. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2002, 4, 665–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaur, G.; Jabbar, Z.; Athar, M.; Alam, M.S. Punica granatum (pomegranate) flower extract possesses potent antioxidant activity and abrogates Fe-NTA induced hepatotoxicity in mice. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2006, 44, 984–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pillaiyar, T.; Manickam, M.; Jung, S.-H. Downregulation of melanogenesis: Drug discovery and therapeutic options. Drug Discov. Today 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prota, G. The role of peroxidase in melanogenesis revisited. Pigment Cell Res. 1992, 3, 25–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baurin, N.; Arnoult, E.; Scior, T.; Do, Q.T.; Bernard, P. Preliminary screening of some tropical plants for anti-tyrosinase activity. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2002, 82, 155–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jimbow, K.; Alena, F.; Dixon, W.; Hara, H. Regulatory factors of pheo- and eumelanogenesis in melanogenic compartments. Pigment Cell Res. 1992, 3, 36–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, S.; Wakamatsu, K. Quantitative analysis of eumelanin and pheomelanin in humans, mice, and other animals: A comparative review. Pigment Cell Res. 2003, 16, 523–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prota, G. Progress in the chemistry of melanins and related metabolites. Med. Res. Rev. 1988, 8, 525–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hearing, V.J. Determination of melanin synthetic pathways. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2011, 131, E8–E11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simon, J.D.; Peles, D.; Wakamatsu, K.; Ito, S. Current challenges in understanding melanogenesis: Bridging chemistry, biological control, morphology, and function. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 2009, 22, 563–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Del Marmol, V.; Beermann, F. Tyrosinase and related proteins in mammalian pigmentation. FEBS Lett. 1996, 381, 165–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slominski, A.; Tobin, D.J.; Shibahara, S.; Wortsman, J. Melanin pigmentation in mammalian skin and its hormonal regulation. Physiol. Rev. 2004, 84, 1155–1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamaguchi, Y.; Brenner, M.; Hearing, V.J. The regulation of skin pigmentation. J. Biol. Chem. 2007, 282, 27557–27561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fitzpatrick, T.B. The validity and practicality of sun-reactive skin types I through VI. Arch. Dermatol. 1988, 124, 869–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fitzpatrick, T.B. Soleil et peau. J. Médecine Esthét. 1975, 2, 33–34. (In French) [Google Scholar]

- Mapunya, M.B.; Nikolova, R.V.; Lall, N. Melanogenesis and antityrosinase activity of selected South African plants. Evid.-Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2012, 2012, e374017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almeda, F.; Astorga, L.; Orellana, A.; Sampuel, L.; Sierra, P.; Gaitán, I.; Cáceres, A. Piper genus: Source of natural products with anti-tyrosinase activity favored in phytocosmetics. Int. J. Phytocosmetics Nat. Ingred. 2015, 2, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krause, W. Drug-induced hyperpigmentation: A systematic review. J. Dtsch. Dermatol. Ges. 2013, 11, 644–651. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kim, S.S.; Kim, M.-J.; Choi, Y.H.; Kim, B.K.; Kim, K.S.; Park, K.J.; Park, S.M.; Lee, N.H.; Hyun, C.-G. Down-regulation of tyrosinase, TRP-1, TRP-2 and MITF expressions by citrus press-cakes in murine B16 F10 melanoma. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Biomed. 2013, 3, 617–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, T.-S. Natural melanogenesis inhibitors acting through the down-regulation of tyrosinase activity. Materials 2012, 5, 1661–1685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pillaiyar, T.; Manickam, M.; Jung, S.-H. Inhibitors of melanogenesis: A patent review (2009–2014). Expert Opin. Ther. Pat. 2015, 25, 775–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hershey, C.L.; Fisher, D.E. Mitf and Tfe3: Members of a b-HLH-ZIP transcription factor family essential for osteoclast development and function. Bone 2004, 34, 689–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shin, J.W.; Park, K.C. Current clinical use of depigmenting agents. Dermatol. Sin. 2014, 32, 205–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murase, D.; Hachiya, A.; Takano, K.; Hicks, R.; Visscher, M.O.; Kitahara, T.; Hase, T.; Takema, Y.; Yoshimori, T. Autophagy has a significant role in determining skin color by regulating melanosome degradation in keratinocytes. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2013, 133, 2416–2424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pomerantz, S.H. Separation, purification, and properties of two tyrosinases from hamster melanoma. J. Biol. Chem. 1963, 238, 2351–2357. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Curto, E.V.; Kwong, C.; Hermersdörfer, H.; Glatt, H.; Santis, C.; Virador, V.; Hearing, V.J.; Dooley, T.P. Inhibitors of mammalian melanocyte tyrosinase: In vitro comparisons of alkyl esters of gentisic acid with other putative inhibitors. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1999, 57, 663–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nerya, O.; Vaya, J.; Musa, R.; Izrael, S.; Ben-Arie, R.; Tamir, S. Glabrene and isoliquiritigenin as tyrosinase inhibitors from licorice roots. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2003, 51, 1201–1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parvez, S.; Kang, M.; Chung, H.-S.; Bae, H. Naturally occurring tyrosinase inhibitors: Mechanism and applications in skin health, cosmetics and agriculture industries. Phytother. Res. 2007, 21, 805–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Solano, F.; Briganti, S.; Picardo, M.; Ghanem, G. Hypopigmenting agents: An updated review on biological, chemical and clinical aspects. Pigment Cell Res. 2006, 19, 550–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, M.; Park, J.; Song, K.; Kim, H.G.; Koh, J.-S.; Boo, Y.C. Screening of plant extracts for human tyrosinase inhibiting effects. Int. J. Cosmet. Sci. 2012, 34, 202–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barber, J.I.; Townsend, D.; Olds, D.P.; King, R.A. Dopachrome oxidoreductase: A new enzyme in the pigment pathway. J. Investig. Dermatol. 1984, 83, 145–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guyonneau, L.; Murisier, F.; Rossier, A.; Moulin, A.; Beermann, F. Melanocytes and pigmentation are affected in dopachrome tautomerase knockout mice. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2004, 24, 3396–3403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, E.-J.; Lee, Y.S.; Hwang, S.; Kim, S.; Hwang, J.S.; Kim, T.-Y. N-(3,5-Dimethylphenyl)-3-Methoxybenzamide (A3B5) targets TRP-2 and inhibits melanogenesis and melanoma growth. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2011, 131, 1701–1709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, S.S.; Yoon, W.J.; Hyun, C.-G.; Lee, N.H. Down-regulation of tyrosinase, TRP-2 and MITF expressions by Neolitsea aciculata extract in murine B16 F10 melanoma. Int. J. Pharmacol. 2010, 6, 290–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aroca, P.; Solano, F.; García-Borrón, J.C.; Lozano, J.A. A new spectrophotometric assay for dopachrome tautomerase. J. Biochem. Biophys. Methods 1990, 21, 35–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, M.; Takara, K.; Toyozato, T.; Wada, K. A novel bioactive chalcone of Morus australis inhibits tyrosinase activity and melanin biosynthesis in B16 melanoma cells. J. Oleo Sci. 2012, 61, 585–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chou, S.-T.; Chang, W.-L.; Chang, C.-T.; Hsu, S.-L.; Lin, Y.-C.; Shih, Y. Cinnamomum cassia essential oil inhibits α-MSH-induced melanin production and oxidative stress in murine B16 melanoma cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2013, 14, 19186–19201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jorge, A.T.S.; Arroteia, K.F.; Santos, I.A.; Andres, E.; Medina, S.P.H.; Ferrari, C.R.; Lourenço, C.B.; Biaggio, R.M.T.T.; Moreira, P.L. Schinus terebinthifolius Raddi extract and linoleic acid from Passiflora edulis synergistically decrease melanin synthesis in B16 cells and reconstituted epidermis. Int. J. Cosmet. Sci. 2012, 34, 435–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hegde, B.; Vadnal, P.; Sanghavi, J.; Korde, V.; Kulkarni-Almeida, A.A.; Dagia, N.M. Vitamin E is a MIF inhibitor. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2012, 418, 384–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nicolaÿ, J.-F.; Levrat, B. A keratinocytes-melanocytes coculture system for the evaluation of active ingredients’ effects on UV-induced melanogenesis. Int. J. Cosmet. Sci. 2003, 25, 15–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duval, C.; Smit, N.P.M.; Kolb, A.M.; Régnier, M.; Pavel, S.; Schmidt, R. Keratinocytes control the pheo/eumelanin ratio in cultured normal human melanocytes. Pigment Cell Res. 2002, 15, 440–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lehraiki, A.; Abbe, P.; Cerezo, M.; Rouaud, F.; Regazzetti, C.; Chignon-Sicard, B.; Passeron, T.; Bertolotto, C.; Ballotti, R.; Rocchi, S. Inhibition of melanogenesis by the antidiabetic metformin. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2014, 134, 2589–2597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gendreau, I.; Angers, L.; Jean, J.; Pouliot, R. Pigmented skin models: Understand the mechanisms of melanocytes. In Regenerative Medicine and Tissue Engineering; Andrades, J.A., Ed.; InTech: Rijeka, Croatia, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, V.C.; Ding, H.-Y.; Tsai, P.-C.; Wu, J.-Y.; Lu, Y.-H.; Chang, T.-S. In vitro and in vivo melanogenesis inhibition by biochanin A from Trifolium pratense. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2011, 75, 914–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cha, S.-H.; Ko, S.-C.; Kim, D.; Jeon, Y.-J. Screening of marine algae for potential tyrosinase inhibitor: Those inhibitors reduced tyrosinase activity and melanin synthesis in zebrafish. J. Dermatol. 2011, 38, 354–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, T.-Y.; Kim, J.-H.; Ko, D.H.; Kim, C.-H.; Hwang, J.-S.; Ahn, S.; Kim, S.Y.; Kim, C.-D.; Lee, J.-H.; Yoon, T.-J. Zebrafish as a new model for phenotype-based screening of melanogenic regulatory compounds. Pigment Cell Res. 2007, 20, 120–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, T.H.; Seo, J.O.; Do, M.H.; Ji, E.; Baek, S.-H.; Kim, S.Y. Resveratrol-enriched rice down-regulates melanin synthesis in UVB-induced guinea pigs epidermal skin tissue. Biomol. Ther. 2014, 22, 431–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fujii, T.; Ikeda, K.; Saito, M. Inhibitory effect of rose hip (Rosa canina L.) on melanogenesis in mouse melanoma cells and on pigmentation in brown guinea pigs. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2011, 75, 489–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nair, X.; Tramposch, K. The Yucatan miniature swine as an in vivo model for screening skin depigmentation. J. Dermatol. Sci. 1991, 2, 428–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nair, X.; Tramposch, K. Effect of single UVR exposure on skin pigmentation and melanocyte morphology in the Yucatan miniature swine. J. Investig. Dermatol. 1990, 94, 558. [Google Scholar]

- Peal, D.S.; Peterson, R.T.; Milan, D. Small molecule screening in zebrafish. J. Cardiovasc. Transl. Res. 2010, 3, 454–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, C.-H.V.; Ding, H.-Y.; Kuo, S.-Y.; Chin, L.-W.; Wu, J.-Y.; Chang, T.-S. Evaluation of in vitro and in vivo depigmenting activity of raspberry ketone from Rheum officinale. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2011, 12, 4819–4835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Imokawa, G.; Kawai, M.; Mishima, Y.; Motegi, I. Differential analysis of experimental hypermelanosis induced by UVB, PUVA, and allergic contact dermatitis using a brownish guinea pig model. Arch. Dermatol. Res. 1986, 278, 352–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meyer, W.; Schwarz, R.; Neurand, K. The skin of domestic mammals as a model for the human skin, with special reference to the domestic pig. Curr. Probl. Dermatol. 1978, 7, 39–52. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Montagna, W.; Yun, J.S. The skin of the domestic pig. J. Investig. Dermatol. 1964, 42, 11–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- David, L.T. Histology of the skin of the Mexican hairless swine (Sus scrofa). Am. J. Anat. 1932, 50, 283–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abella, M.L.; de Rigal, J.; Neveux, S. A simple experimental method to study depigmenting agents. Int. J. Cosmet. Sci. 2007, 29, 311–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uter, W.; Benz, M.; Mayr, A.; Gefeller, O.; Pfahlberg, A. Assessing skin pigmentation in epidemiological studies: The reliability of measurements under different conditions. Skin Res. Technol. 2013, 19, 100–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, Y.; Hoshino, T.; Chen, C.J.; E, Y.; Yabe, S.; Liu, W. The evaluation of whitening efficacy of cosmetic products using a human skin pigmentation spot model. Skin Res. Technol. 2009, 15, 218–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watanabe, F.; Hashizume, E.; Chan, G.P.; Kamimura, A. Skin-whitening and skin-condition-improving effects of topical oxidized glutathione: A double-blind and placebo-controlled clinical trial in healthy women. Clin. Cosmet. Investig. Dermatol. 2014, 7, 267–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoshimura, K.; Sato, K.; Aiba-Kojima, E.; Matsumoto, D.; Machino, C.; Nagase, T.; Gonda, K.; Koshima, I. Repeated treatment protocols for melasma and acquired dermal melanocytosis. Dermatol. Surg. 2006, 32, 365–371. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Orlow, S.J.; Chakraborty, A.K.; Pawelek, J.M. Retinoic acid is a potent inhibitor of inducible pigmentation in murine and hamster melanoma cell lines. J. Investig. Dermatol. 1990, 94, 461–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ortonne, J.-P. Retinoid therapy of pigmentary disorders. Dermatol. Ther. 2006, 19, 280–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weldon, M.M.; Smolinski, M.S.; Maroufi, A.; Hasty, B.W.; Gilliss, D.L.; Boulanger, L.L.; Balluz, L.S.; Dutton, R.J. Mercury poisoning associated with a Mexican beauty cream. West. J. Med. 2000, 173, 15–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pop, C.; Vlase, L.; Tamas, M. Natural resources containing arbutin. Determination of arbutin in the leaves of Bergenia crassifolia (L.) Fritsch. acclimated in Romania. Not. Bot. Horti Agrobot. Cluj-Napoca 2009, 37, 129–132. [Google Scholar]

- Qin, L.; Wu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, P. Dual effects of alpha-arbutin on monophenolase and diphenolase activities of mushroom tyrosinase. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e109398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cabanes, J.; Chazarra, S.; Garcia-Carmona, F. Kojic acid, a cosmetic skin whitening agent, is a slow-binding inhibitor of catecholase activity of tyrosinase. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 1994, 46, 982–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bentley, R. From miso, saké and shoyu to cosmetics: A century of science for kojic acid. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2006, 23, 1046–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiang, H.M.; Chen, H.W.; Huang, Y.H.; Chan, S.Y.; Chen, C.C.; Wu, W.C.; Wen, K.C. Melanogenesis and natural hypopigmentation agents. In Melanin: Biosynthesis, functions and health effects; eBook; Ma, X.-P., Sun, X.-X., Eds.; NOVA Science Publisher: Hauppauge, NY, USA, 2012; pp. 1–76. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Y.-J.; Uyama, H. Tyrosinase inhibitors from natural and synthetic sources: Structure, inhibition mechanism and perspective for the future. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2005, 62, 1707–1723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arjinpathana, N.; Asawanonda, P. Glutathione as an oral whitening agent: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. J. Dermatol. Treat. 2012, 23, 97–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fujiwara, Y.; Sahashi, Y.; Aritro, M.; Hasegawa, S.; Akimoto, K.; Ninomiya, S.; Sakaguchi, Y.; Seyama, Y. Effect of simultaneous administration of vitamin C, L-cysteine and vitamin E on the melanogenesis. BioFactors 2004, 21, 415–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kameyama, K.; Sakai, C.; Kondoh, S.; Yonemoto, K.; Nishiyama, S.; Tagawa, M.; Murata, T.; Ohnuma, T.; Quigley, J.; Dorsky, A.; et al. Inhibitory effect of magnesium l-ascorbyl-2-phosphate (VC-PMG) on melanogenesis in vitro and in vivo. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 1996, 34, 29–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Régnier, M.; Tremblaye, C.; Schmidt, R. Vitamin C affects melanocyte dendricity via keratinocytes. Pigment Cell Res. 2005, 18, 389–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hakozaki, T.; Minwalla, L.; Zhuang, J.; Chhoa, M.; Matsubara, A.; Miyamoto, K.; Greatens, A.; Hillebrand, G.G.; Bissett, D.L.; Boissy, R.E. The effect of niacinamide on reducing cutaneous pigmentation and suppression of melanosome transfer. Br. J. Dermatol. 2002, 147, 20–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Navarrete-Solís, J.; Castanedo-Cázares, J.P.; Torres-Álvarez, B.; Oros-Ovalle, C.; Fuentes-Ahumada, C.; González, F.J.; Martínez-Ramírez, J.D.; Moncada, B. A double-blind, randomized clinical trial of niacinamide 4% versus hydroquinone 4% in the treatment of melasma. Dermatol. Res. Pract. 2011, 2011, e379173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X. A theory for the mechanism of action of the alpha-hydroxy acids applied to the skin. Med. Hypotheses 1999, 53, 380–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Usuki, A.; Ohashi, A.; Sato, H.; Ochiai, Y.; Ichihashi, M.; Funasaka, Y. The inhibitory effect of glycolic acid and lactic acid on melanin synthesis in melanoma cells. Exp. Dermatol. 2003, 12 (Suppl. S2), 43–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parvez, S.; Kang, M.; Chung, H.-S.; Cho, C.; Hong, M.-C.; Shin, M.-K.; Bae, H. Survey and mechanism of skin depigmenting and lightening agents. Phytother. Res. 2006, 20, 921–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Charlín, R.; Barcaui, C.B.; Kac, B.K.; Soares, D.B.; Rabello-Fonseca, R.; Azulay-Abulafia, L. Hydroquinone-induced exogenous ochronosis: A report of four cases and usefulness of dermoscopy. Int. J. Dermatol. 2008, 47, 19–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olumide, Y.M.; Akinkugbe, A.O.; Altraide, D.; Mohammed, T.; Ahamefule, N.; Ayanlowo, S.; Onyekonwu, C.; Essen, N. Complications of chronic use of skin lightening cosmetics. Int. J. Dermatol. 2008, 47, 344–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Donoghue, J.L. Hydroquinone and its analogues in dermatology—A risk-benefit viewpoint. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2006, 5, 196–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dadzie, O.E.; Petit, A. Skin bleaching: Highlighting the misuse of cutaneous depigmenting agents. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2009, 23, 741–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- AFSSAPS. Évaluation des Risques Liés à la Dépigmentation Volontaire. Available online: http://ansm.sante.fr/content/download/36916/483991/version/1/file/Rapport-depigmentation2011.pdf (accessed on 21 September 2016).

- Liste des Produits Eclaircissants de la Peau Non Conformes et Dangereux Identifiés en France, Contenant de L’hydroquinone. Available online: http://ansm.sante.fr/content/download/36918/484005/version/1/file/Liste-produits+-depigmentatio+-Afssaps-DGCCRF.pdf (accessed on 21 September 2016).

- ANSM. Suspension de la Mise sur le Marché des Produits Eclaircissants de la Peau Présentés en Solution Injectable—Point D’information. Available online: http://ansm.sante.fr/S-informer/Points-d-information-Points-d-information/Suspension-de-la-mise-sur-le-marche-des-produits-eclaircissants-de-la-peau-presentes-en-solution-injectable-Point-d-Information (accessed on 21 September 2016).

- FDA. Consumer Health Information—Injectable Skin Lightening Products: What You Should Know. Available online: http://www.fda.gov/downloads/ForConsumers/ConsumerUpdates/UCM460999.pdf (accessed on 21 September 2016).

- Regulation (EC) No 1223/2009 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 30 November 2009 on Cosmetic Products. Available online: http://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=OJ:L:2009:342:0059:0209:en:PDF (accessed on 21 September 2016).

- ANSM. Groupe de Travail Reproduction, Grossesse et Allaitement GT252015043. Available online: http://ansm.sante.fr/var/ansm_site/storage/original/application/a713e233daf32e61474bf1462500a0b1.pdf (accessed on 21 September 2016).

- Blaut, M.; Braune, A.; Wunderlich, S.; Sauer, P.; Schneider, H.; Glatt, H. Mutagenicity of arbutin in mammalian cells after activation by human intestinal bacteria. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2006, 44, 1940–1947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- SCCS/1481/12—Opinion on Kojic Acid. Available online: http://ec.europa.eu/health/scientific_committees/consumer_safety/docs/sccs_mi_015.pdf (accessed on 21 September 2016).

- Bains, V.K.; Loomba, K.; Loomba, A.; Bains, R. Mercury sensitisation: Review, relevance and a clinical report. Br. Dent. J. 2008, 205, 373–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO (World Health Organization). Mercury in Skin Lightening Products. Available online: http://www.who.int/ipcs/assessment/public_health/mercury_flyer.pdf (accessed on 21 September 2016).

- Engler, D.E. Mercury “bleaching” creams. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2005, 52, 1113–1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tlacuilo-Parra, A.; Guevara-Gutiérrez, E.; Luna-Encinas, J.A. Percutaneous mercury poisoning with a beauty cream in Mexico. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2001, 45, 966–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Counter, S.A.; Buchanan, L.H. Mercury exposure in children: A review. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2004, 198, 209–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahé, A.; Ly, F.; Perret, J.-L. Systemic complications of the cosmetic use of skin-bleaching products. Int. J. Dermatol. 2005, 44 (Suppl. S1), 37–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Desmedt, B.; Van Hoeck, E.; Rogiers, V.; Courselle, P.; De Beer, J.O.; De Paepe, K.; Deconinck, E. Characterization of suspected illegal skin whitening cosmetics. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2014, 90, 85–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakagawa, M.; Kawai, K.; Kawai, K. Contact allergy to kojic acid in skin care products. Contact Dermat. 1995, 32, 9–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DFI. Ordonnance du DFI sur les Cosmétiques RS 817.023.31. Available online: https://www.admin.ch/opc/fr/classified-compilation/20050180/201510010000/817.023.31.pdf (accessed on 21 September 2016).

- Pauwels, M.; Rogiers, V. Human health safety evaluation of cosmetics in the EU: A legally imposed challenge to science. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2010, 243, 260–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Batubara, I.; Darusman, L.K.; Mitsunaga, T.; Rahminiwati, M.; Djauhari, E. Potency of Indonesian medicinal plants as tyrosinase inhibitor and antioxidant agent. J. Biol. Sci. 2010, 10, 138–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nugroho, A.; Choi, J.-K.; Park, J.-H.; Lee, K.-T.; Cha, B.C.; Park, H.-J. Two new flavonol glycosides from Lamium amplexicaule L. and their in vitro free radical scavenging and tyrosinase inhibitory activities. Planta Med. 2009, 75, 364–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yokota, T.; Nishio, H.; Kubota, Y.; Mizoguchi, M. The inhibitory effect of glabridin from licorice extracts on melanogenesis and inflammation. Pigment Cell Res. 1998, 11, 355–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, L.-P.; Chen, Q.-X.; Huang, H.; Wang, H.-Z.; Zhang, R.-Q. Inhibitory effects of some flavonoids on the activity of mushroom tyrosinase. Biochem. Mosc. 2003, 68, 487–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, K.; Hughes, J.; Hong, M.; Jia, Q.; Orndorff, S. Modulation of melanogenesis by aloesin: A competitive inhibitor of tyrosinase. Pigment Cell Res. 2002, 15, 335–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, S.; Lee, S.-K.; Kim, J.-E.; Chung, M.-H.; Park, Y.-I. Aloesin inhibits hyperpigmentation induced by UV radiation. Clin. Exp. Dermatol. 2002, 27, 513–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leu, Y.-L.; Hwang, T.-L.; Hu, J.-W.; Fang, J.-Y. Anthraquinones from Polygonum cuspidatum as tyrosinase inhibitors for dermal use. Phytother. Res. 2008, 22, 552–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Devkota, K.P.; Khan, M.T.H.; Ranjit, R.; Lannang, A.M.; Samreen; Choudhary, M.I. Tyrosinase inhibitory and antileishmanial constituents from the rhizomes of Paris polyphylla. Nat. Prod. Res. 2007, 21, 321–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kao, T.-C.; Wu, C.-H.; Yen, G.-C. Bioactivity and potential health benefits of licorice. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2014, 62, 542–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, C.-H.; Chou, T.-H.; Ding, H.-Y. Inhibition of melanogenesis by a novel origanoside from Origanum vulgare. J. Dermatol. Sci. 2010, 57, 170–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shin, N.H.; Ryu, S.Y.; Choi, E.J.; Kang, S.H.; Chang, I.M.; Min, K.R.; Kim, Y. Oxyresveratrol as the potent inhibitor on dopa oxidase activity of mushroom tyrosinase. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1998, 243, 801–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeong, S.H.; Ryu, Y.B.; Curtis-Long, M.J.; Ryu, H.W.; Baek, Y.S.; Kang, J.E.; Lee, W.S.; Park, K.H. Tyrosinase inhibitory polyphenols from roots of Morus lhou. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2009, 57, 1195–1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.H.; Choi, S.Y.; Kim, H.; Hwang, J.S.; Lee, B.G.; Gao, J.J.; Kim, S.Y. Mulberroside F isolated from the leaves of Morus alba inhibits melanin biosynthesis. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2002, 25, 1045–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, K.B.; Lee, D.Y.; Kim, T.B.; Kim, S.H.; Kim, H.J.; Kim, J.; Sung, S.H. Prediction of tyrosinase inhibitory activities of Morus alba root bark extracts from HPLC fingerprints. Microchem. J. 2013, 110, 731–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.H.; Lee, S.Y.; Hong, C.Y.; Gwak, K.S.; Park, M.J.; Smith, D.; Choi, I.G. Whitening and antioxidant activities of bornyl acetate and nezukol fractionated from Cryptomeria japonica essential oil. Int. J. Cosmet. Sci. 2013, 35, 484–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]