Mushroom Cosmetics: The Present and Future

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Mushrooms: Nutritional and Medicinal Facts

2.1. Beneficial Components of Mushrooms

2.1.1. Phenolic and Polyphenolic Compounds

2.1.2. Terpenoids

2.1.3. Selenium

2.1.4. Polysaccharides

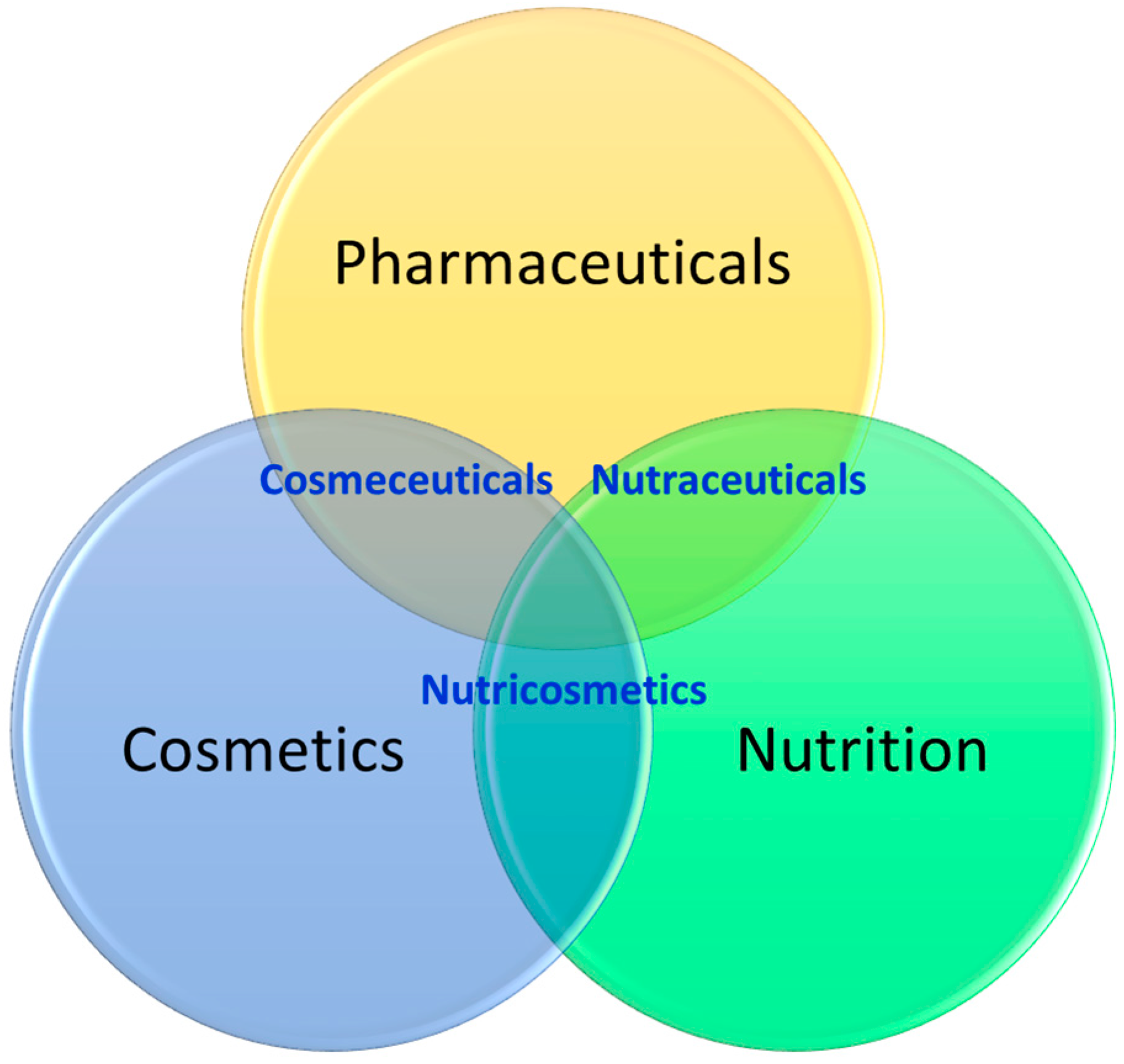

3. Cosmetics: Category and Progress

3.1. Cosmeceuticals

3.2. Nutricosmetics

4. Moisturizing Effect

5. Anti-Aging Effect (Lifting and Firming)

5.1. Antioxidant Activity

5.2. Anti-Wrinkle Activity

6. Skin Whitening Effect

7. Hair Cosmetics

8. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CATP | Carboxymethylated Polysaccharide |

| COX-2 | Cyclooxygenase-2 |

| DOPA | Dihydroxyphenylalanine |

| EGCG | Epigallocatechin Gallate |

| GPx | Glutathione Peroxidase |

| GXM | Glucuronoxylomannan |

| MMPs | Matrix Metalloproteinases |

| MRSs | Maintenance and Repair Systems |

| PGE2 | Prostaglandin E2 |

| PGs | Prostaglandins |

| PSK | Polysaccharide Krestin |

| PSP | Polysaccharide Peptide |

| Se | Selenium |

| SOD | Superoxidase Dismutase |

References

- Cheung, P.C. Mushrooms as Functional Foods; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2008; pp. 1–34. [Google Scholar]

- Miles, P.G.; Chang, S.T. Mushrooms: Cultivation, Nutritional Value, Medicinal Effect, and Environmental Impact, 2nd ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2004; pp. 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Wasser, S.P. Current findings, future trends, and unsolved problems in studies of medicinal mushrooms. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2011, 89, 1323–1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mueller, G.M.; Schmit, J.P. Fungal biodiversity: What do we know? What can we predict? Biodivers. Conserv. 2007, 16, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirk, P.M.; Cannon, P.F.; Minter, D.W.; Stalpers, J.A. Ainsworth and Bisby’s Dictionary of the Fungi, 10th ed.; Centre for Agriculture and Biosciences International: Wallingford, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Poucheret, P.; Fons, F.; Rapior, S. Biological and pharmacological activity of higher fungi: 20-Year retrospective analysis. Cryptogam. Mycol. 2006, 27, 311–333. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad, M.F.; Ahmad, F.A.; Azad, Z.; Ahmad, A.; Alam, M.I.; Ansari, J.A.; Panda, B.P. Edible mushrooms as health promoting agent. Adv. Sci. Focus 2013, 1, 189–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bashir, A.; Vaida, N.; Dar, M.A. Medicinal importance of mushrooms—A review. Int. J. Adv. Res. 2014, 2, 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, S.T.; Wasser, S.P. The role of culinary-medicinal mushrooms on human welfare with a pyramid model for human health. Int. J. Med. Mushrooms 2012, 14, 95–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El Enshasy, H.A.; Hatti-Kaul, R. Mushroom immunomodulators: Unique molecules with unlimited applications. Trends Biotechnol. 2013, 31, 668–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalač, P. A review of chemical composition and nutritional value of wild-growing and cultivated mushrooms. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2013, 93, 209–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Millikan, L.E. Cosmetology, cosmetics, cosmeceuticals: Definitions and regulations. Clin. Dermatol. 2001, 19, 371–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antignac, E.; Nohynek, G.J.; Re, T.; Clouzeau, J.; Toutain, H. Safety of botanical ingredients in personal care products/cosmetics. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2011, 49, 324–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hyde, K.D.; Bahkali, A.H.; Moslem, M.A. Fungi—An unusual source for cosmetics. Fungal Divers. 2010, 43, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camassola, M. Mushrooms—The incredible factory for enzymes and metabolites productions. Ferment. Technol. 2013, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badalyan, S.M. The main groups of therapeutic compounds of medicinal mushrooms. Med. Mycol. 2001, 3, 16–23. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J. Biologically active substances from mushrooms in Yunnan, China. Heterocycles 2002, 57, 157–167. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Mills, G.L.; Nair, M.G. Cyclooxygenase inhibitory and antioxidant compounds from the mycelia of the edible mushroom Grifola frondosa. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2002, 50, 7581–7585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, M.H.; Han, H.K.; Lee, Y.J.; Jo, H.G.; Shin, H.J. In vitro anti-cancer activity of hydrophobic fractions of Sparassis latifolia extract using AGS, A529, and HepG2 cell lines. J. Mushroom 2014, 12, 304–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Griensven, L.J. Culinary-medicinal mushrooms: Must action be taken? Int. J. Med. Mushrooms 2009, 11, 281–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wani, B.A.; Bodha, R.H.; Wani, A.H. Nutritional and medicinal importance of mushrooms. J. Med. Plants Res. 2010, 4, 2598–2604. [Google Scholar]

- Wasser, S.P. Medicinal mushroom science: History, current status, future trends, and unsolved problems. Int. J. Med. Mushrooms 2010, 12, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandrasekaran, G.; Oh, D.S.; Shin, H.J. Versatile applications of the culinary-medicinal mushroom Mycoleptodonoides aitchisonii (Berk.) Maas G. (Higher Basidiomycetes): A review. Int. J. Med. Mushrooms 2012, 14, 395–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Silva, D.D.; Rapior, S.; Hyde, K.D.; Bahkali, A.H. Medicinal mushrooms in prevention and control of diabetes mellitus. Fungal Divers. 2012, 56, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mortimer, P.E.; Karunarathna, S.C.; Li, Q.; Gui, H.; Yang, X.; Yang, X.; Hyde, K.D. Prized edible Asian mushrooms: Ecology, conservation and sustainability. Fungal Divers. 2012, 56, 31–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, B.; Park, J.; Park, J.; Shin, H.J.; Kwon, S.; Yeom, M.; Sur, B.; Kim, S.; Kim, M.; Lee, H.; et al. Cordyceps militaris improves neurite outgrowth in Neuro2A cells and reverses memory impairment in rats. Food Sci. Biotechnol. 2011, 20, 1599–1608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattila, P.; Könkö, K.; Eurola, M.; Pihlava, J.M.; Astola, J.; Vahteristo, L.; Hietaniemi, V.; Kumpulainen, J.; Valtonen, M.; Piironen, V. Contents of vitamins, mineral elements, and some phenolic compounds in cultivated mushrooms. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2001, 49, 2343–2348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bernaś, E.; Jaworska, G.; Lisiewska, Z. Edible mushrooms as a source of valuable nutritive constituents. Acta Sci. Pol. Technol. Aliment. 2006, 5, 5–20. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, Y.; Lee, S.M.; Chun, J.; Lee, H.B.; Lee, J. Influence of heat treatment on the antioxidant activities and polyphenolic compounds of Shiitake (Lentinus edodes) mushroom. Food Chem. 2006, 99, 381–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, T.X.; Furuta, S.; Fukamizu, S.; Yamamoto, R.; Ishikawa, H.; Arung, E.T.; Kondo, R. Evaluation of biological activities of extracts from the fruiting body of Pleurotus citrinopileatus for skin cosmetics. J. Wood Sci. 2011, 57, 452–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deepalakshmi, K.; Mirunalini, S. Therapeutic properties and current medical usage of medicinal mushroom: Ganoderma lucidum. Int. J. Pharm. Sci. Res. 2011, 2, 1922–1929. [Google Scholar]

- Chiu, S.W.; Law, S.C.; Ching, M.L.; Cheung, K.W.; Chen, M.J. Themes for mushroom exploitation in the 21st century: Sustainability, waste management, and conservation. J. Gen. Appl. Microbiol. 2000, 46, 269–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Badalyan, S.M. Potential of mushroom bioactive molecules to develop healthcare biotech products. In Proceedings of the 8th International Conference on Mushroom Biology and Mushroom Products, New Delhi, India, 19–22 November 2014.

- Smith, J.E.; Rowan, N.J.; Sullivan, R. Medicinal mushrooms: A rapidly developing area of biotechnology for cancer therapy and other bioactivities. Biotechnol. Lett. 2002, 24, 1839–1845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gautier, S.; Xhauflaire-Uhoda, E.; Gonry, P.; Piérard, G.E. Chitinglucan, a natural cell scaffold for skin moisturization and rejuvenation. Int. J. Cosmet. Sci. 2008, 30, 459–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Baets, S.; Vandamme, E.J. Extracellular Tremella polysaccharides: Structure, properties and applications. Biotech. Lett. 2001, 23, 1361–1366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.M.; Zhang, A.L.; Chen, H.; Liu, J.K. Molecular species of ceramides from the ascomycete truffle Tuber indicum. Chem. Phys. Lipids 2004, 131, 205–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bowe, W.P. Cosmetic benefits of natural ingredients: Mushrooms, feverfew, tea, and wheat complex. J. Drugs Dermatol. 2013, 12, s133–s136. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ferreira, I.C.; Barros, L.; Abreu, R. Antioxidants in wild mushrooms. Curr. Med. Chem. 2009, 16, 1543–1560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, M.Y.; Seguin, P.; Ahn, J.K.; Kim, J.J.; Chun, S.C.; Kim, E.H.; Seo, S.H.; Kang, E.Y.; Kim, S.L.; Park, Y.J.; et al. Phenolic compound concentration and antioxidant activities of edible and medicinal mushrooms from Korea. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2008, 56, 7265–7270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bentley, R. From miso, sake and shoyu to cosmetics: A century of science for kojic acid. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2006, 23, 1046–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wright, J.S.; Johnson, E.R.; DiLabio, G.A. Predicting the activity of phenolic antioxidants: Theoretical method, analysis of substituent effects, and application to major families of antioxidants. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001, 123, 1173–1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, R.H. Potential synergy of phytochemicals in cancer prevention: Mechanism of action. J. Nutr. 2004, 134, 3479S–3485S. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Le Marchand, L. Cancer preventive effects of flavonoids—A review. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2002, 56, 296–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Zhou, S.; Jiang, W.; Huang, M.; Dai, X. Effects of ganopoly (a Ganoderma lucidum polysaccharide extract) on the immune functions in advanced-stage cancer patients. Immunol. Investig. 2003, 32, 201–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, Y.T.; Yang, B.K.; Jeong, S.C.; Kim, S.M.; Song, C.H. Ganoderma applanatum: A promising mushroom for antitumor and immunomodulating activity. Phytother. Res. 2008, 22, 614–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, J.M.; Lee, J.; Lee, Y.W. Characterization of carotenoid biosynthetic genes in the ascomycete Gibberella zeae. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2010, 302, 197–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Racz, L.; Bumbalova, A.; Harangozo, M.; Tölgyessy, J.; Tomeček, O. Determination of cesium and selenium in cultivated mushrooms using radionuclide X-ray fluorescence technique. J. Radioanal. Nucl. Chem. 2000, 245, 611–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogra, Y.; Ishiwata, K.; Encinar, J.R.; Łobiński, R.; Suzuki, K.T. Speciation of selenium in selenium-enriched shiitake mushroom, Lentinula edodes. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2004, 379, 861–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McSheehy, S.; Yang, W.; Pannier, F.; Szpunar, J.; Łobiński, R.; Auger, J.; Potin-Gautier, M. Speciation analysis of selenium in garlic by two-dimensional high-performance liquid chromatography with parallel inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometric and electrospray tandem mass spectrometric detection. Anal. Chim. Acta 2000, 421, 147–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Synytsya, A.; Míčková, K.; Synytsya, A.; Jablonský, I.; Spěváček, J.; Erban, V.; Kováříkovád, E.; Čopíková, J. Glucans from fruit bodies of cultivated mushrooms Pleurotus ostreatus and Pleurotus eryngii: Structure and potential prebiotic activity. Carbohydr. Polym. 2009, 76, 548–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikekawa, T. Beneficial effects of edible and medicinal mushrooms on health care. Int. J. Med. Mushrooms 2001, 3, 79–86. [Google Scholar]

- Hobbs, C. The chemistry, nutritional value, immunopharmacology, and safety of the traditional food of medicinal split-gill fugus Schizophyllum commune Fr.: Fr. (Schizophyllaceae). A literature review. Int. J. Med. Mushrooms 2005, 7, 127–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angeli, J.P.; Ribeiro, L.R.; Bellini, M.F.; Mantovani, M.S. β-Glucan extracted from the medicinal mushroom Agaricus blazei prevents the genotoxic effects of benzo[a]pyrene in the human hepatoma cell line HepG2. Arch. Toxicol. 2009, 83, 81–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, N.; White, P.J.; Alavi, S. Impact of β-glucan and other oat flour components on physico-chemical and sensory properties of extruded oat cereals. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2011, 46, 651–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bisen, P.S.; Baghel, R.K.; Sanodiya, B.S.; Thakur, G.S.; Prasad, G.B. Lentinus edodes: A macrofungus with pharmacological activities. Curr. Med. Chem. 2010, 17, 2419–2430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oricha, B.S. Cosmeceuticals: A review. Afr. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2010, 4, 127–129. [Google Scholar]

- Anuradha, S.N.; Vilashene, G.; Lalithambigai, J.; Arunkumar, S. “Cosmeceuticals”: An opinion in the direction of pharmaceuticals. Asian J. Pharm. Clin. Res. 2015, 8, 64–69. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, C.M.; Berson, D.S. Cosmeceuticals. Semin. Cutan. Med. Surg. 2006, 25, 163–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anunciato, T.P.; da Rocha Filho, P.A. Carotenoids and polyphenols in nutricosmetics, nutraceuticals, and cosmeceuticals. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2012, 11, 51–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barel, A.O.; Paye, M.; Maibach, H.I. 55 Use of food supplements as nutricosmetics in health and fitness. In Handbook of Cosmetic Science and Technology, 4th ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2014; pp. 583–596. [Google Scholar]

- Sator, P.G.; Schmidt, J.B.; Hönigsmann, H. Comparison of epidermal hydration and skin surface lipids in healthy individuals and in patients with atopic dermatitis. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2003, 48, 352–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baumann, L. Skin ageing and its treatment. J. Pathol. 2007, 211, 241–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, S.H.; Liu, H.I.; Tsai, S.J. Edible Tremella Polysaccharide for Skin Care. U.S. Patent US20060222608, 5 October 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, K.; Meng, X.Y.; Sun, Y.; Guo, P.Y. Preparation of Tremella, Speranskiae tuberculatae and Eriocaulon buergerianum extracts and their performance in cosmetics. Deterg. Cosmet. 2013, 36, 28–32. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, H.; He, L. Comparison of the moisture retention capacity of Tremella polysaccharides and hyaluronic acid. J. Anhui Agric. Sci. 2012, 40, 13093–13094. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Zhang, Z.; Zhao, M. Carboxymethylation of polysaccharides from Tremella fuciformis for antioxidant and moisture-preserving activities. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2015, 72, 526–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liao, W.C.; Hsueh, C.Y.; Chan, C.F. Antioxidative activity, moisture retention, film formation, and viscosity stability of Auricularia fuscosuccinea, white strain water extract. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2014, 78, 1029–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sandewicz, I.M.; Julio, G.R.; Zhu, V.X. Anhydrous Cosmetic Compositions Containing Mushroom Extract. U.S. Patent US6645502, 11 November 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Kosmadaki, M.G.; Gilchrest, B.A. The role of telomeres in skin aging/photoaging. Micron 2004, 35, 155–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khare, N.; Khare, P.; Yadav, G. Recent advances in anti-aging—A review. Glob. J. Pharm. 2015, 9, 267–271. [Google Scholar]

- Lupo, M.P.; Cole, A.L. Cosmeceutical peptides. Dermatol. Ther. 2007, 20, 343–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheung, L.M.; Cheung, P.C. Mushroom extracts with antioxidant activity against lipid peroxidation. Food Chem. 2005, 89, 403–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puttaraju, N.G.; Venkateshaiah, S.U.; Dharmesh, S.M.; Urs, S.M.; Somasundaram, R. Antioxidant activity of indigenous edible mushrooms. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2006, 54, 9764–9772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Landrault, N.; Poucheret, P.; Ravel, P.; Gasc, F.; Cros, G.; Teissedre, P.L. Antioxidant capacities and phenolics levels of French wines from different varieties and vintages. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2001, 49, 3341–3348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheung, L.M.; Cheung, P.C.; Ooi, V.E. Antioxidant activity and total phenolics of edible mushroom extracts. Food Chem. 2003, 81, 249–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubost, N.J.; Beelman, R.B.; Peterson, D.; Royse, D.J. Identification and quantification of ergothioneine in cultivated mushrooms by liquid chromatography-mass spectroscopy. Int. J. Med. Mushrooms 2006, 8, 215–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, C.; Huang, X.; Cheng, L.; Bu, Y.; Liu, G.; Yi, F.; Yang, Z.; Song, F. Evaluation of antioxidant and immune activity of Phellinus ribis glucan in mice. Food Chem. 2009, 115, 581–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maity, K.; Kar, E.; Maity, S.; Gantait, S.K.; Das, D.; Maiti, S.; Maiti, T.K.; Sikdar, S.R.; Islam, S.S. Structural characterization and study of immunoenhancing and antioxidant property of a novel polysaccharide isolated from the aqueous extract of a somatic hybrid mushroom of Pleurotus florida and Calocybe indica variety APK2. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2011, 48, 304–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, J.; He, H.; Xie, B.J. Novel antioxidant peptides from fermented mushroom Ganoderma lucidum. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2004, 52, 6646–6652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, S.Y.; Go, K.C.; Song, Y.S.; Jeong, Y.S.; Kim, E.J.; Kim, B.J. Extract of the mycelium of T. matsutake inhibits elastase activity and TPA-induced MMP-1 expression in human fibroblasts. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2014, 34, 1613–1621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, T.K.; Shin, D.B.; Lee, K.R.; Shin, P.G.; Cheong, J.C.; Yoo, Y.B.; Lee, M.W.; Jin, G.H.; Kim, H.Y.; Im, K.H.; et al. Antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activities of fruiting bodies of Dyctiophora Indusiata. J. Mushroom 2013, 11, 269–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Prescott, S.M. Many actions of cyclooxygenase-2 in cellular dynamics and in cancer. J. Cell. Physiol. 2002, 190, 279–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stanikunaite, R.; Khan, S.I.; Trappe, J.M.; Ross, S.A. Cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitory and antioxidant compounds from the truffle Elaphomyces granulatus. Phytother. Res. 2009, 23, 575–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, J.; Chiang, H.; Lin, Y.; Wen, K. Natural products with skin-whitening effects. J. Food Drug Anal. 2008, 16, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, S.K.; Gautam, A.; Kumar, S. Natural skin whitening agents: A current status. Adv. Biol. Res. 2014, 8, 257–259. [Google Scholar]

- Parvez, S.; Kang, M.; Chung, H.S.; Bae, H. Naturally occurring tyrosinase inhibitors: Mechanism and applications in skin health, cosmetics and agriculture industries. Phytother. Res. 2007, 21, 805–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, T.S. An updated review of tyrosinase inhibitors. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2009, 10, 2440–2475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, D.; Park, J.; Kim, J.; Han, C.; Yoon, J.; Kim, N.; Seo, J.; Lee, C. Flavonoids as mushroom tyrosinase inhibitors: A fluorescence quenching study. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2006, 54, 935–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.S.; Shin, D.B.; Lee, S.M.; Kim, S.H.; Lee, T.S.; Jung, D.C. Melanogenesis inhibitory and antioxidant activities of Phellinus baumii methanol extract. Korean J. Mycol. 2013, 41, 104–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagasaka, R.; Ishikawa, Y.; Inada, T.; Ohshima, T. Depigmenting effect of winter medicinal mushroom Flammulna velutipes (higher Basidiomycetes) on melanoma cells. Int. J. Med. Mushrooms 2015, 17, 511–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chien, C.C.; Tsai, M.L.; Chen, C.C.; Chang, S.J.; Tseng, C.H. Effects on tyrosinase activity by the extracts of Ganoderma lucidum and related mushrooms. Mycopathologia 2008, 166, 117–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Draelos, Z.D. Hair cosmetics. In Hair Growth and Disorders; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin, Germany; Heidelberg, Germany, 2008; pp. 499–513. [Google Scholar]

- Madnani, N.; Khan, K. Hair cosmetics. Indian J. Dermatol. Venereol. Leprol. 2013, 79, 654–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dias, M.F. Hair cosmetics: An overview. Int. J. Trichol. 2015, 7, 2–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nazir, H.; Wang, L.; Lian, G.; Zhu, S.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Ma, G. Multilayered silicone oil droplets of narrow size distribution: preparation and improved deposition on hair. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2012, 100, 42–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meehan, K. Composition to Promote Hair Growth in Humans. U.S. Patent US9144542, 29 September 2015. [Google Scholar]

| Mycochemicals | Mushroom Species | Activities | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alkaloids | Agaricus bisporus, Coprinus comatus, Pleurotus ostreatus, Volvareilla volvacea | Antimicrobial, Anti-inflammatory, Antioxidant | [27] |

| Carbohydrate | Agaricus bisporus, Lyophyllum shimeiji, Pleurotus ostreatus, Termitomyces eurhizus, Volvareilla volvacea | Antimicrobial | [24] |

| Flavonoids | Lactarius deliciosus, Lentinus edodes, Macrolepiota mastoidea, Russula griseocarnosa | Antimicrobial, Anti-inflammatory, Antioxidant | [25] |

| Glycosides | Flammulina velutipes, Grifola frondosa, Hypsizigus mamoreus, Lentinus edodes, Pholiota nameko | Anti-inflammatory, Antioxidant | [17,25] |

| Phenols and Polyphenols | Agaricus bisporus, Lentinus edodes, Phellinus linteus, Pleurotus ostreatus, Sparassis crispa, Tricholoma equestre | Antimicrobial, Anti-inflammatory, Antioxidant | [16,27] |

| Protein and amino acids | Agaricus bisporus, Coprinus comatus, Lentinus edodes, Pleurotus ostreatus, Sparassis crispa, Volvareilla volvacea | Antimicrobial, Anti-inflammatory | [19] |

| Saponins | Agaricus bisporus, Ganoderma lucidum, Pleurotus ostreatus, Termitomyces albuminosus, Wolfiporia cocos | Anticancer, Antioxidant | [26] |

| Steroids | Agaricus subrufescens, Marasmius oreades, Panellus serotinus, Pleurotus eryngii, Stropharia rugosoannulata | Anti-inflammatory | [32] |

| Tannins | Agaricus bisporus, Lentinus edodes, Lentinus sajor-caju, Volvareilla volvacea | Antimicrobial, Antioxidant | [25] |

| Triterpenoids | Ganoderma colossum, Lepista nuda, Naematoloma sublateritium, Panellus serotinus, Scleroderma citrinum, Tricholoma matsutake | Antibacterial, Anti-inflammatory | [16,31] |

| Product Name | Mushroom/Extract Included | Function |

|---|---|---|

| Aveeno Positively Ageless Daily Exfoliating Cleanser, U.S. | Lentinula edodes | Lift away dirt, oil and makeup and fight signs of aging |

| One Love Organics Vitamin D Moisture Mist, U.K. | Lentinula edodes | Part lightweight moisturizer and part toner |

| Osmia Organics Luz Facial Brightening Serum, U.S. | Lentinula edodes extract | Skin looking bright and luminous |

| CV Skinlabs Body Repair Lotion, U.S. | Ganoderma lucidum | Wound-healing and anti-inflammatory |

| Dr. Andrew Weil for Origins Mega-Mushroom Skin Relief Face Mask, U.S. | Ganoderma lucidum | Anti-inflammatory properties |

| Four Sigma Foods Instant Reishi Herbal Mushroom Tea, U.K. | Ganoderma lucidum | Immunity boost |

| Kat Burki Form Control Marine Collagen Gel, U.K. | Ganoderma lucidum | Boost collagen, improve elasticity and provide hydration |

| Menard Embellir Refresh Massage, France | Ganoderma lucidum | Skin anti-aging |

| Moon Juice Spirit Dust, U.S. | Ganoderma lucidum | Immune system |

| Tela Beauty Organics Encore Styling Cream, U.K. | Ganoderma lucidum | Provide hair with sun protection and prevent color fading |

| Yves Saint Laurent Temps Majeur Elixir De Nuit, France | Ganoderma lucidum | Anti-aging |

| Vitamega Facial Moisturizing Mask, Brazil | Agaricus subrufescens (also known as A. brasiliensis) | Renew and revitalize skin |

| Kose Sekkisei Cream, Japan | Cordyceps sinensis | Moisturizer and suppress melanin production |

| Root Science RS Reborn Organic Face Mask, U.S. | Inonotus obliquus | Anti-inflammatory to help soothe irritated skin |

| Alqvimia Eternal Youth Cream Facial Máxima Regeneración, Spain | Schizophyllum commune | Anti-aging and lifting |

| Sulwhasoo Hydroaid, Korea | Schizophyllum commune extract | Hydrating cream promoting clear, radiant skin |

| La Prairie Advanced Marine Biology Night Solution, Switzerland | Tremella fuciformis | Moisturizer which nourishes, revitalizes and hydrates skin |

| BeautyDiy Aqua Circulation Hydrating Gel, Taiwan | Tremella polysaccharide | Moisturizing gel |

| Surkran Grape Seed Lift Eye Mask, U.S. | Tremella polysaccharide | Improve skin around eyes |

| Hankook Sansim Firming Cream (Tan Ryuk SANG), Korea | Ganoderma lucidum and Pleurotus ostreatus | Make skin tight and vitalized |

| La Bella Figura Gentle Enzyme Cleanser, Italia | Ganoderma lucidum and Lentinula edodes extracts | Antioxidants and vitamin D |

| Pureology NanoWorks Shineluxe, France | Ganoderma lucidum, Lentinula edodes, and Mucor miehei | Anti-age and anti-fade |

| Snowberry Bright Defense Day Cream No. 1, New Zealand | Mushroom extract | Hydrate and illuminate dull skin, along with anti-bacterial properties to help prevent acne |

| Murad Invisiblur Perfecting Shield, U.S. | Mushroom peptides | Diminish fine lines and wrinkles by aiding regulation of collagen and elastin |

© 2016 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC-BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wu, Y.; Choi, M.-H.; Li, J.; Yang, H.; Shin, H.-J. Mushroom Cosmetics: The Present and Future. Cosmetics 2016, 3, 22. https://doi.org/10.3390/cosmetics3030022

Wu Y, Choi M-H, Li J, Yang H, Shin H-J. Mushroom Cosmetics: The Present and Future. Cosmetics. 2016; 3(3):22. https://doi.org/10.3390/cosmetics3030022

Chicago/Turabian StyleWu, Yuanzheng, Moon-Hee Choi, Jishun Li, Hetong Yang, and Hyun-Jae Shin. 2016. "Mushroom Cosmetics: The Present and Future" Cosmetics 3, no. 3: 22. https://doi.org/10.3390/cosmetics3030022

APA StyleWu, Y., Choi, M.-H., Li, J., Yang, H., & Shin, H.-J. (2016). Mushroom Cosmetics: The Present and Future. Cosmetics, 3(3), 22. https://doi.org/10.3390/cosmetics3030022