A Multifaceted View on Ageing of the Hair and Scalp

Abstract

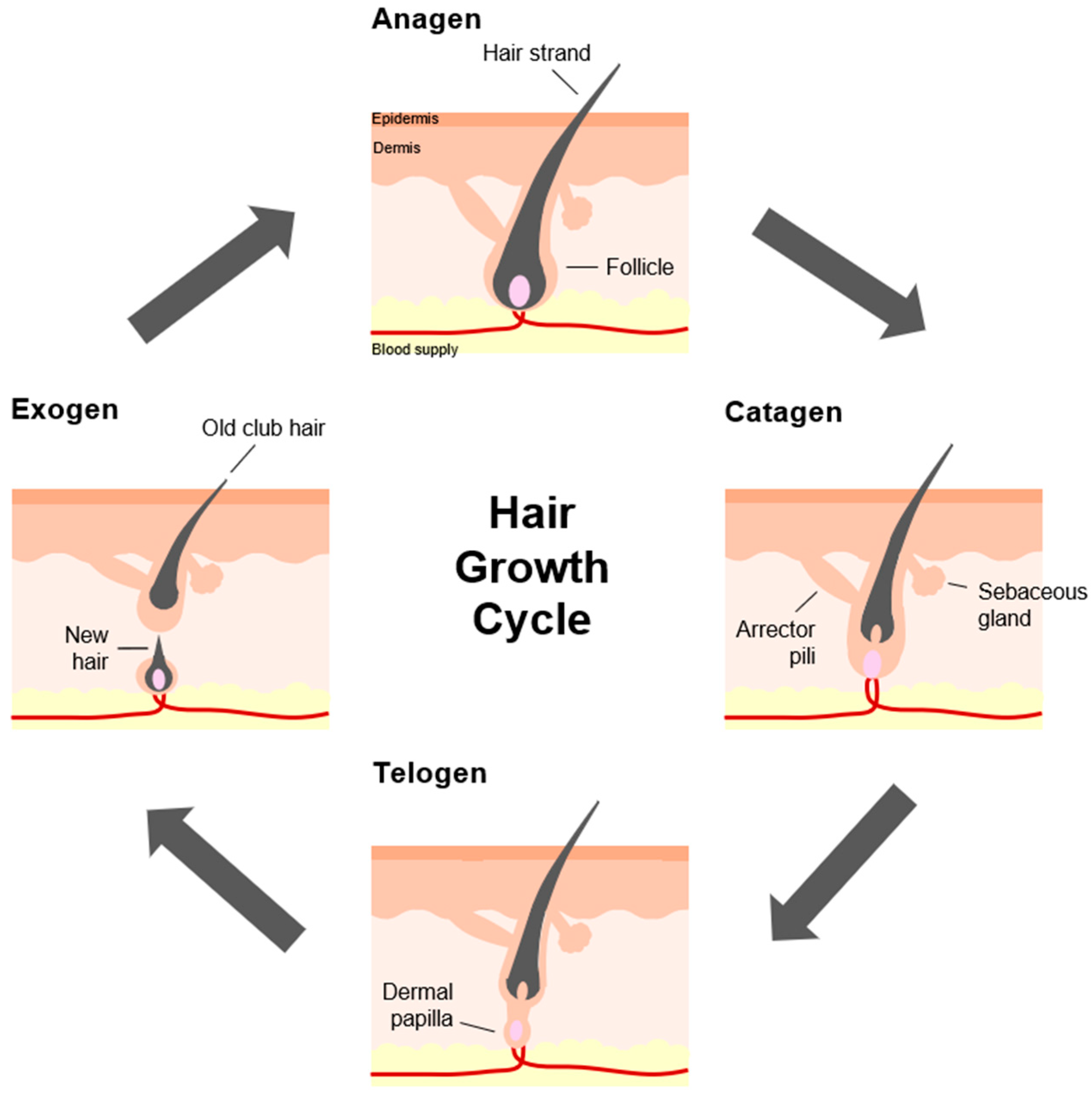

1. Introduction

2. Characteristics of Ageing Hair

2.1. Hair Greying

2.2. Hair Loss During Ageing

Senescent/Senile Alopecia and Androgenetic Alopecia

2.3. Changes in Morphology and Properties of Hair During Ageing

3. Ageing Scalp Skin

3.1. Age-Related Changes in the Scalp Skin

3.2. Scalp Skin Microbiome and Ageing

4. Hair and Scalp Care

5. Concluding Remarks

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PSU | Pilosebaceous Unit |

| ORS | Outer Root Sheath |

| IRS | Inner Root Sheath |

| GM | Germinative Matrix |

| DP | Dermal Papilla |

| DS | Dermal Sheath |

| HFPU | Hair Follicle Pigmentary Unit |

| MeSC | Melanocyte Stem Cell |

| UV | Ultraviolet |

| ROS | Reactive Oxygen Species |

| L-DOPA | L-3,4-dihydroxyphenylalanine |

| KRTs | Keratins |

| KRTAP | Keratin-associated Proteins |

| KRT6 | Keratin 6 |

| KRT14/16 | Keratin 14/16 |

| KRTAP4 | Keratin-associated Protein 4 |

| FGF7 | Fibroblast Growth Factor 7 |

| FGF5 | Fibroblast Growth Factor 5 |

| DDR | DNA Damage Response |

| ATM | Ataxia-Telangiectasia Mutated |

| HFSCs | Hair Follicle Stem Cells |

| MITF | Microphthalmia-associated Transcription Factor |

| Bcl-2 | B-cell Lymphoma 2 |

| TGF-β | Transforming Growth Factor-β |

| Col17A1 | Collagen XVII |

| SCF/c-Kit | Stem Cell Factor and its receptor c-Kit |

| NFIB | Nuclear Factor I/B |

| EDNRB | Endothelin Receptor Type B |

| CXCL12 | C-X-C Motif Chemokine Ligand 12 |

| TYR | Tyrosinase |

| TYRP1 | Tyrosinase-related Proteinase 1 |

| KIT | Tyrosine Kinase Receptor for SCF |

| NER | Nucleotide Excision Repair |

| HPP | Hair Pigmentation Patterns |

| AGA | Androgenetic Alopecia |

| SA | Senescent Alopecia |

| EGF | Epidermal Growth Factor |

| IGF-1 | Insulin-like Growth Factor 1 |

| BMP | Bone Morphogenetic Protein |

| Hh | Hedgehog |

| VEGF | Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor |

| UVR | Ultraviolet Radiation |

| 18-MEA | 18-methyleicosanoic Acid |

| SC | Stratum Corneum |

| ECM | Extracellular Matrix |

| PCPN | Podoplanin |

| VCAN | Versican |

| MMP1 | Matrix Metalloproteinase 1 |

| COMP | Cartilage Oligomeric Matrix Protein |

| dWAT | Dermal White Adipose Tissue |

| ADSVCs | Adipose-derived stromal vascular cells |

| HGF | Hepatocyte Growth Factor |

| FESEM | Field Emission Scanning Electron Microscopy |

| CLSM | Confocal Laser Scanning Microscopy |

| LCM | Laser-capture Microdissection |

| AMP | Antimicrobial Peptide |

| OTUs | Operational Taxonomic Units |

| HIF-1α | Hypoxia-inducible Factor 1-α |

| WIHN | Wound-induced Hair Follicle Neogenesis |

| PM10 | Particulate Matter 10 |

| KGF | Keratinocyte Growth Factor |

| PKB | Protein Kinase B |

| ERK | Extracellular Signal-regulated Kinases |

| Shh | Sonic Hedgehog |

| JNK | c-Jun N-terminal Kinase |

| JAK | Janus-activated Kinase |

| STAT3 | Signal Transducer and Activator of Transcription 3 |

| KLF4 | Krüppel-like Factor 4 |

References

- Trüeb, R.M. The value of hair cosmetics and pharmaceuticals. Dermatology 2001, 202, 275–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trüeb, R.M.; Henry, J.P.; Davis, M.G.; Schwartz, J.R. Scalp condition impacts hair growth and retention via oxidative stress. Int. J. Trichology 2018, 10, 262–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Etcoff, N. Survival of the Prettiest: The Science of Beauty; Anchor: Hamburg, Germany, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Symons, D. Beauty is in the adaptions of the beholder: The evolutionary psychology of human female sexual attractiveness. In Sexual Nature, Sexual Culture; Abramson, P.R., Pinkerton, S.D., Eds.; The University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1995; pp. 80–119. [Google Scholar]

- Hinsz, V.B.; Matz, D.C.; Patience, R.A. Does women’s hair signal reproductive potential? J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2001, 37, 166–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fink, B.; Hufschmidt, C.; Hirn, T.; Will, S.; McKelvey, G.; Lankhof, J. Age, health and attractiveness perception of virtual (rendered) human hair. Front. Psychol. 2016, 22, 1893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, Y.S.; Harland, D.P.; Dawson, T.L., Jr. Wanted, dead and alive: Why a multidisciplinary approach is needed to unlock hair treatment potential. Exp. Dermatol. 2019, 28, 517–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Natarelli, N.; Gahoonia, N.; Sivamani, R.K. Integrative and mechanistic approach to the hair growth cycle and hair loss. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 893–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jimenez, F.; Alam, M. The proportion of catagen and telogen hair follicles in occipital scalp of male androgenetic alopecia patients: Challenging the established dogma. Exp. Dermatol. 2024, 33, e70001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burg, D.; Yamamoto, M.; Namekata, M.; Haklani, J.; Koike, K.; Halasz, M. Promotion of anagen, increased hair density and reduction of hair fall in a clinical setting following identification of FGF5-inhibiting compounds via a novel 2-stage process. Clin. Cosmet. Investig. Dermatol. 2017, 10, 71–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, S.; Bergfeld, W. Diffuse hair loss: Its triggers and management. Cleve. Clin. J. Med. 2009, 76, 361–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paus, R.; Cotsarelis, G. The biology of hair follicles. N. Engl. J. Med. 1999, 341, 491–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bichakjian, C.K.; Johnson, T.M. Chapter 1—Anatomy of the skin. In Local Flaps in Facial Reconstruction, 2nd ed.; Baker, S.R., Ed.; Mosby: Maryland Heights, MO, USA, 2007; pp. 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindberg, M.; Forslind, B. Formation and structure: An introduction to hair. In Skin, Hair, and Nails, 1st ed.; Forslind, B., Lindberg, M., Eds.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Li, H.; Masieri, F.F.; Schneider, M.; Bartella, A.; Gaus, S.; Hahnel, S.; Zimmerer, R.; Sack, U.; Maksimovic-Ivanic, D.; Mijatovic, S.; et al. The middle part of the plucked hair follicle outer root sheath is identified as an area rich in lineage-specific stem cell markers. Biomolecules 2021, 11, 154–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leerunyakul, K.; Suchonwanit, P. Asian hair: A review of structures, properties, and distinctive disorders. Clin. Cosmet. Investig. Dermatol. 2020, 13, 309–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trüeb, R.M. Possibilities and limitations for reversal of age-related pigment loss. In Aging Hair; Trüeb, R.M., Tobin, D.J., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2010; pp. 207–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tobin, D.J.; Paus, R. Graying: Gerontobiology of the hair follicle pigmentary unit. Exp. Gerontol. 2001, 36, 29–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keogh, E.V.; Walsh, R.J. Rate of greying of human hair. Nature 1965, 207, 877–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panhard, S.; Lozano, I.; Loussouarn, G. Greying of the human hair: A worldwide survey, revisiting the ‘50′ rule of thumb. Br. J. Dermatol. 2012, 167, 865–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandhi, D.; Khanna, D. Premature graying of hair. Indian J. Dermatol. Venereol. Leprol. 2013, 79, 641–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maymone, M.B.C.; Laughter, M.; Pollock, S.; Khan, I.; Marques, T.; Abdat, R.; Goldberg, L.J.; Vashi, N.A. Hair aging in different races and ethnicities. J. Clin. Aesthet. Dermatol. 2021, 14, 38–44. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kumar, A.B.; Shamim, H.; Nagaraju, U. Premature graying of hair: Review with updates. Int. J. Trichology 2018, 10, 198–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jo, S.J.; Paik, S.H.; Choi, J.W.; Lee, J.H.; Cho, S.; Kim, K.H.; Eun, H.C.; Oh, S.K. Hair graying pattern depends on gender, onset age and smoking habits. Acta Derm. Venereol. 2012, 92, 160–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, S.K.; Lee, J.Y.; Lee, Y.; Kim, C.D.; Lee, J.; Lee, Y.H. Three streams for the mechanism of hair graying. Ann. Dermatol. 2018, 30, 397–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutnin, S.; Chanprapaph, K.; Pakornphadungsit, K.; Leerunyakul, K.; Visessiri, Y.; Srisont, S.; Suchonwanit, P. Variation of hair follicle counts among different scalp areas: A quantitative histopathology study. Skin Appendage Disord. 2021, 8, 24–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sikkink, S.K.; Mine, S.; Freis, O.; Danoux, L.; Tobin, D.J. Stress-sensing in the human greying hair follicle: Ataxia Telangiectasia Mutated (ATM) depletion in hair bulb melanocytes in canities-prone scalp. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 18711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Sullivan, J.D.B.; Nicu, C.; Picard, M.; Chéret, J.; Bedogni, B.; Tobin, D.J.; Paus, R. The biology of human hair greying. Biol. Rev. Camb. Philos. Soc. 2021, 96, 107–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Kang, Y.; Qi, F.; Jin, H. Genetics of hair graying with age. Ageing Res. Rev. 2023, 89, 101977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paus, R.; Sevilla, A.; Grichnik, J.M. Human hair graying revisited: Principles, misconceptions, and key research frontiers. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2024, 144, 474–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, J.; Shen, L.Y.; Wang, G.C. Role of hair follicles in the repigmentation of vitiligo. J. Investig. Dermatol. 1991, 97, 410–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kauser, S.; Westgate, G.E.; Green, M.R.; Tobin, D.J. Human hair follicle and epidermal melanocytes exhibit striking differences in their aging profile which involve catalase. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2011, 131, 979–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trüeb, R.M. Oxidative stress in ageing of hair. Int. J. Trichology 2009, 1, 6–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, J.W.; Kloepper, J.; Langan, E.A.; Kim, Y.; Yeo, J.; Kim, M.J.; Hsi, T.; Rose, C.; Yoon, G.S.; Lee, S.; et al. A guide to studying human hair cycling in vivo. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2016, 136, 34–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tobin, D.J. Aging of the hair follicle pigmentation system. Int. J. Trichology 2009, 1, 83–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tobin, D.J.; Bystryn, J.C. Different populations of melanocytes are present in hair follicles and epidermis. Pigment Cell Res. 1996, 9, 304–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernandez-Flores, A.; Saeb-Lima, M.; Cassarino, D.S. Histopathology of aging of the hair follicle. J. Cutan. Pathol. 2019, 46, 508–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slominski, A.; Wortsman, J.; Plonka, P.M.; Schallreuter, K.U.; Paus, R.; Tobin, D.J. Hair follicle pigmentation. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2005, 124, 13–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, K.J.; Lim, J.; Tan, Y.N.; Quek, D.; Lim, Z.; Pantelireis, N.; Clavel, C. Sox2 in the dermal papilla regulates hair follicle pigmentation. Cell Rep. 2022, 40, 111100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Commo, S.; Gaillard, O.; Bernard, B.A. Human hair greying is linked to a specific depletion of hair follicle melanocytes affecting both the bulb and the outer root sheath. Br. J. Dermatol. 2004, 150, 435–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arck, P.C.; Overall, R.; Spatz, K.; Liezman, C.; Handjiski, B.; Klapp, B.F.; Birch-Machin, M.A.; Peters, E.M.J. Towards a “free radical theory of graying”: Melanocyte apoptosis in the aging human hair follicle is an indicator of oxidative stress induced tissue damage. FASEB J. 2006, 20, 1567–1569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, Y.S.; Dawson, T.L. Ageing hair in Asians and Caucasians. In Practical Aspects of Hair Transplantation in Asians; Pathomvanich, D., Imagawa, K., Eds.; Springer: Tokyo, Japan, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tobin, D.J.; Hagen, E.; Botchkarev, V.A.; Paus, R. Do hair bulb melanocytes undergo apoptosis during hair follicle regression (catagen)? J. Investig. Dermatol. 1998, 111, 941–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Neste, D. Thickness, medullation and growth rate of female scalp hair are subject to significant variation according to pigmentation and scalp location during ageing. Eur. J. Dermatol. 2004, 14, 28–32. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, H.I.; Choi, G.I.; Kim, E.K.; Choi, Y.J.; Sohn, K.C.; Lee, Y.; Kim, C.D.; Yoon, T.J.; Sohn, H.J.; Han, S.H.; et al. Hair greying is associated with active hair growth. Br. J. Dermatol. 2011, 165, 1183–1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inomata, K.; Aoto, T.; Nguyen, T.B.; Okamoto, N.; Tanimura, S.; Wakayama, T.; Iseki, S.; Hara, E.; Masunaga, T.; Shimizu, H.; et al. Genotoxic stress abrogates renewal of melanocyte stem cells by triggering their differentiation. Cell 2009, 137, 1088–1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishimura, E.K.; Granter, S.R.; Fisher, D.E. Mechanisms of hair greying: Incomplete melanocyte stem cell maintenance in the niche. Science 2005, 307, 720–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishimura, E.K.; Suzuki, M.; Igras, V.; Du, J.; Lonning, S.; Miyachi, Y.; Roes, J.; Beermann, F.; Fisher, D.E. Key roles for Transforming Growth Factor β in melanocyte stem cell maintenance. Cell Stem Cell 2010, 6, 130–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishimura, E.K. Melanocyte stem cells: A melanocyte reservoir in hair follicles for hair and skin pigmentation. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 2011, 24, 401–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanimura, S.; Tadokoro, Y.; Inomata, K.; Nguyen, T.B.; Nishie, W.; Yamazaki, S.; Nakauchi, H.; Tanaka, Y.; McMillan, J.R.; Sawamura, D.; et al. Hair follicle stem cells provide a functional niche for melanocyte stem cells. Cell Stem Cell 2011, 8, 177–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botchkareva, N.V.; Khlgatian, M.; Longley, B.J.; Botchkarev, V.A.; Gilchrest, B.A. SCF/c-kit signaling is required for cyclic regeneration of the hair pigmentation unit. FASEB J. 2001, 15, 645–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moriyama, M.; Osawa, M.; Mak, S.; Ohtsuka, T.; Yamamoto, N.; Han, H.; Delmas, V.; Kageyama, R.; Beermann, F.; Larue, L.; et al. Notch signalling via Hes1 transcription factor maintains survival of melanoblasts and melanocyte stem cells. J. Cell Biol. 2006, 173, 333–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schouwey, K.; Delmas, V.; Larue, L.; Zimber-Strobl, U.; Strobl, L.J.; Radtke, F.; Beermann, F. Notch1 and Notch2 receptors influence progressive hair graying in a dose-dependent manner. Dev. Dyn. 2007, 236, 282–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valluet, A.; Druillennec, S.; Barbotin, C.; Dorard, C.; Monsoro-Burg, A.; Larcher, M.; Pouponnot, C.; Baccarini, M.; Larue, L.; Eychène, A. B-Raf and C-Raf are required for melanocyte stem cell self-maintenance. Cell Rep. 2012, 2, 774–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubic, J.D.; Young, K.P.; Plummer, R.S.; Ludvik, A.E.; Lang, D. Pigmentation PAX-ways: The role of Pax3 in melanogenesis, melanocyte stem cell maintenance, and disease. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 2008, 21, 627–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, L.; Zuo, Y.; Li, S.; Li, C. Melanocyte stem cells in the skin: Origin, biological characteristics, homeostatic maintenance and therapeutic potential. Clin. Transl. Med. 2024, 14, e1720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, Y.J.; Yoon, T.J.; Lee, Y.H. Changing expression of the genes related to human hair graying. Eur. J. Dermatol. 2008, 18, 397–399. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Peters, E.M.J.; Liezmann, C.; Spatz, K.; Ungethüm, U.; Kuban, R.; Daniltchenko, M.; Kruse, J.; Imfeld, D.; Klapp, B.F.; Campiche, R. Profiling mRNA of the graying human hair follicle constitutes a promising state-of-the-art tool to assess its aging: An exemplary report. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2013, 133, 1150–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adav, S.S.; Ng, K.W. Recent omics advances in hair aging biology and hair biomarker analysis. Ageing Res. Rev. 2023, 91, 102041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, M.; Bell, R.H.; Ho, M.M.; Leung, G.; Haegert, A.; Carr, N.; Shapiro, J.; McElwee, K.J. Deficiency in Nucleotide Excision Repair family gene activity, especially ERCC3, is associated with non-pigmented hair fiber growth. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e34185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Q.; Lee, W.; Hu, H.; Ogawa, T.; De Leon, S.; Katehis, I.; Lim, C.H.; Takeo, M.; Cammer, M.; Taketo, M.M.; et al. Dedifferentiation maintains melanocyte stem cells in a dynamic niche. Nature 2023, 616, 774–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenberg, A.M.; Rausser, S.; Ren, J.; Mosharov, E.V.; Sturm, G.; Ogden, R.T.; Patel, P.; Soni, R.K.; Lacefield, C.; Tobin, D.J.; et al. Quantitative mapping of human hair greying and reversal in relation to life stress. eLife 2021, 10, e67437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Muthuvel, K. Practical approach to hair loss diagnosis. Indian J. Plast. Surg. 2021, 54, 399–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, T.G.; Slomiany, W.P.; Allison, R. Hair loss: Common causes and treatment. Am. Fam. Physician 2017, 96, 371–378. [Google Scholar]

- Qi, J.; Garza, L.A. An overview of alopecias. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2014, 4, a013615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gokce, N.; Basgoz, N.; Kenanoglu, S.; Akalin, H.; Ozkul, Y.; Ergoren, M.C.; Becarri, T.; Bertelli, M.; Dundar, M. An overview of the genetic aspects of hair loss and its connection with nutrition. J. Prev. Med. Hyg. 2022, 63, E228–E238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morgan, B.A. The dermal papilla: An instructive niche for epithelial stem and progenitor cells in development and regeneration of the hair follicle. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2014, 4, a015180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, J.; Ng, K.J.; Clavel, C. Chapter Four—Dermal papilla regulation of hair growth and pigmentation. In Advances in Stem Cells and their Niches; Perez-Moreno, M., Ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019; pp. 115–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Qiu, X.; Liao, X. Dermal papilla cells: From basic research to translational applications. Biology 2024, 13, 842–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Scott, E.J.; Eckel, T.M. Geometric relationships between the matrix of the hair bulb and its dermal papilla in normal and alopecic scalp. J. Investig. Dermatol. 1958, 31, 281–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elliott, K.; Stephenson, T.J.; Messenger, A.G. Differences in hair follicle dermal papilla volume are due to extracellular matrix volume and cell number: Implications for the control of hair follicle size and androgen responses. J. Investig. Dermatol. 1999, 113, 873–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miranda, B.H.; Tobin, D.J.; Sharpe, D.T.; Randall, V.A. Intermediate hair follicles: A new more clinically relevant model for hair growth investigations. Br. J. Dermatol. 2010, 163, 287–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdin, R.; Zhang, Y.; Jimenez, J.J. Treatment of androgenetic alopecia using PRP to target dysregulated mechanisms and pathways. Front. Med. 2022, 16, 843127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, J.; Jang, Y.; Sim, J.; Ryu, D.; Cho, E.; Park, D.; Jung, E. Anti-hair loss effect of veratric acid on dermal papilla cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 2240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pappalardo, A.; Kim, J.Y.; Abaci, H.E.; Christiano, A.M. Restoration of hair follicle inductive properties by depletion of senescent cells. Aging Cell 2025, 24, e14353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, T.; Li, Y.; Jin, S.; Yang, F.; Xiong, R.; Dai, Y.; Song, X.; Guan, C. Progress on mitochondria and hair follicle development in androgenetic alopecia: Relationships and therapeutic perspectives. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2025, 16, 44–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Xiong, Y.; Li, Y. Pathogenesis and regenerative therapy in vitiligo and alopecia areata: Focus on hair follicle. Front. Med. 2025, 11, 1510363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joulai Veijouye, S.; Yari, A.; Heidari, F.; Sajedi, N.; Ghoroghi Moghani, F.; Nobakht, M. Bulge region as a putative hair follicle stem cells niche: A brief review. Iran. J. Public Health 2017, 46, 1167–1175. [Google Scholar]

- Xing, Y.; Guo, H.; Xiang, F.; Li, Y. Recent progress in hair follicle stem cell markers and their regulatory roles. World J. Stem Cells 2024, 16, 126–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Huang, W.; Wang, E.H.C.; Tai, K.; Lin, S. Functional complexity of hair follicle stem cell niche and therapeutic targeting of niche dysfunction for hair regeneration. J. Biomed Sci. 2020, 27, 43–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, H.; Jo, Y.; Lee, J.H.; Choi, S. Aging of hair follicle stem cells and their niches. BMB Rep. 2023, 56, 2–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.H.; Choi, S. Deciphering the molecular mechanisms of stem cell dynamics in hair follicle regeneration. Exp. Mol. Med. 2024, 56, 110–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsumura, H.; Mohri, Y.; Binh, N.T.; Morinaga, H.; Fukuda, M.; Ito, M.; Kurata, S.; Hoeijmakers, J.; Nishimura, E.K. Hair follicle aging is driven by transepidermal elimination of stem cells via COL17A1 proteolysis. Science 2016, 351, aad4395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keyes, B.E.; Segal, J.P.; Heller, E.; Lien, W.; Chang, C.; Guo, X.; Oristian, D.S.; Zheng, D.; Fuchs, E. Nfatc1 orchestrates aging in hair follicle stem cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, E4950–E4959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Messenger, A.G. Hair through the female life cycle. Br. J. Dermatol. 2011, 165, 2–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Y.; Wang, M.; He, Y.; Liu, F.; Chen, L.; Xiong, X. Cellular senescence: Ageing and androgenetic alopecia. Dermatology 2023, 239, 533–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, J.; Ho, B.S.; Qian, G.; Xie, X.; Bigliardi, P.L.; Bigliardi-Qi, M. Aging in hair follicle stem cells and niche microenvironment. J. Dermatol. 2017, 44, 1097–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, Y.; Miao, Y.; Gur-Cohen, S.; Gomez, N.; Yang, H.; Nikolova, M.; Polak, L.; Hu, Y.; Verma, A.; Elemento, O.; et al. The aging microenvironment dictates stem cell behavior. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 5339–5350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tiwari, R.L.; Mishra, P.; Martin, N.; George, N.O.; Sakk, V.; Soller, K.; Nalapareddy, K.; Nattamai, K.; Scharffetter-Kochanek, K.; Florian, M.C.; et al. A Wnt5a-Cdc42 axis controls aging and rejuvenation of hair-follicle stem cells. Aging 2021, 13, 4778–4793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Egger, A.; Tomic-Canic, M.; Tosti, A. Advances in stem cell-based therapy for hair loss. CellR4 Repair Replace. Regen. Reprogram. 2020, 8, e2894. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Whiting, D.A. How real is senescent alopecia? A histopathologic approach. Clin. Dermatol. 2011, 29, 49–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ntshingila, S.; Oputu, O.; Arowolo, A.T.; Khumalo, N.P. Androgenetic alopecia: An update. JAAD Int. 2023, 13, 150–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Xie, X.; Zhang, G.; Zhang, Y. Comorbidities in androgenetic alopecia: A comprehensive review. Dermatol. Ther. 2022, 12, 2233–2247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trüeb, R.M.; Rezende, H.D.; Dias, M.F.R.G. A comment on the science of hair aging. Int. J. Trichology 2018, 10, 245–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kligman, A.M. The comparative histopathology of male-pattern baldness and senescent baldness. Clin. Dermatol. 1988, 6, 108–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karnik, P.; Shah, S.; Dvorkin-Wininger, Y.; Oshtory, S.; Mirmirani, P. Microarray analysis of androgenetic and senescent alopecia: Comparison of gene expression shows two distinct profiles. J. Dermatol. Sci. 2013, 72, 183–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillmer, A.M.; Hanneken, S.; Ritzmann, S.; Becker, T.; Freudenberg, J.; Brockschmidt, F.F.; Flaquer, A.; Freudenberg-Hua, Y.; Jamra, R.A.; Metzen, C.; et al. Genetic variation in the human androgen receptor gene is the major determinant of common early-onset androgenetic alopecia. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2005, 77, 140–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, R.; Brockschimidt, F.F.; Kiefer, A.K.; Stefansson, H.; Nyholt, D.R.; Song, K.; Vermeulen, S.H.; Kanoni, S.; Glass, D.; Medland, S.E.; et al. Six novel susceptibility Loci for early-onset androgenetic alopecia and their unexpected association with common diseases. PLoS Genet. 2012, 8, e1002746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Courtney, A.; Triwongwarant, D.; Chim, I.; Eisman, S.; Sinclair, R. Evaluating 5 alpha reductase inhibitors for the treatment of male androgenetic alopecia. Expert Opin. Pharmacother. 2023, 24, 1919–1922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hirshburg, J.M.; Kelsey, P.A.; Therrien, C.A.; Gavino, A.C.; Reichenberg, J.S. Adverse effects and safety of 5-alpha reductase inhibitors (Finasteride, Dustasteride): A systematic review. J. Clin. Aesthet. Dermatol. 2016, 9, 56–62. [Google Scholar]

- Sawaya, M.E.; Price, V.H. Different levels of 5α-reductase type I & II, aromatase, and androgen receptor in hair follicles of women and men with androgenetic alopecia. J. Investig. Dermatol. 1997, 109, 296–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messenger, A.G.; Rundegren, J. Minoxidil: Mechanisms of action on hair growth. Br. J. Dermatol. 2004, 150, 186–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.K.; Taluker, M.; Venkataraman, M.; Bamimore, M.A. Minoxidil: A comprehensive review. J. Dermatol. Treat. 2022, 33, 1896–1906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orasan, M.S.; Bolfa, P.; Coneac, A.; Muresan, A.; Mihu, C. Topical products for human hair regeneration: A comparative study on an animal model. Ann. Dermatol. 2016, 28, 65–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naito, A.; Midorikawa, T.; Yoshino, T.; Ohdera, M. Lipid peroxides induce early onset of catagen phase in murine hair cycles. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2008, 22, 725–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahta, A.W.; Farjo, N.; Farjo, B.; Philpott, M.P. Premature senescence of balding dermal papilla cells in vitro is associated with p16INK4a expression. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2008, 128, 1088–1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaworsky, C.; Kligman, A.M.; Murphy, G.F. Characterization of inflammatory infiltrates in male pattern alopecia: Implications for pathogenesis. Br. J. Dermatol. 1992, 127, 239–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahé, Y.F.; Michelet, J.F.; Billoni, N.; Jarrousse, F.; Buan, B.; Commo, S.; Saint-Léger, D.; Bernard, B.A. Androgenetic alopecia and microinflammation. Int. J. Dermatol. 2000, 39, 576–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.I.; Choi, S.; Roh, W.S.; Lee, J.H.; Kim, T. Cellular senescence and inflammaging in the skin microenvironment. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 3849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whiting, D.A. Diagnostic and predictive value of horizontal sections of scalp biopsy specimens in male pattern androgenetic alopecia. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 1993, 28 Pt 1, 755–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eichmüller, S.; van der Veen, C.; Moll, I.; Hermes, B.; Hofmann, U.; Müller-Röver, S.; Paus, R. Clusters of perifollicular macrophages in normal murine skin: Physiological degeneration of selected hair follicles by programmed organ deletion. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 1998, 46, 361–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Neste, D.; Tobin, D.J. Hair cycle and hair pigmentation: Dynamic interactions and changes associated with aging. Micron 2004, 35, 193–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robbins, C.; Mirmirani, P.; Messenger, A.G.; Birch, M.P.; Youngquist, R.S.; Tamura, M.; Filloon, T.; Luo, F.; Dawson, T.L., Jr. What women want—Quantifying the perception of hair amount: An analysis of hair diameter and density changes with age in Caucasian women. Br. J. Dermatol. 2012, 167, 324–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otsuka, H.; Nemoto, T. Study on Japanese hair. J. Jpn. Cosmet. Sci. Soc. 1988, 12, 192–197. [Google Scholar]

- Trotter, M.; Dawson, H.L. The hair of French Canadians. Am. J. Phys. Anthrop. 1934, 18, 443–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Courtois, M.; Loussouarn, G.; Hourseau, C.; Grollier, J.F. Ageing and hair cycles. Br. J. Dermatol. 1995, 132, 86–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirmirani, P.; Luo, F.; Youngquist, S.R.; Fisher, B.K.; Li, J.; Oblong, J.; Dawson, T.L., Jr. Hair growth parameters in pre-and postmenopausal women. In Aging Hair; Trüeb, R.M., Tobin, D.J., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2010; pp. 49–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baltenneck, F.; Genty, G.; Samra, E.B.; Richena, M.; Harland, D.P.; Clerens, S.; Leccia, E.; Le Blach, M.; Doucet, J.; Michelet, J.; et al. Age-associated thin hair displays molecular, structural and mechanical characteristic changes. J. Struct. Biol. 2022, 214, 107908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, G.V.; Robbins, C.R. Stiffness of human hair fibers. J. Soc. Cosmet. Chem. 1978, 29, 469–485. [Google Scholar]

- Robbins, C.R.; Crawford, R.J. Cuticle damage and the tensile properties of human hair. J. Soc. Cosmet. Chem. 1991, 42, 49–58. [Google Scholar]

- Persaud, D.; Kamath, Y.K. Torsional method for evaluating hair damage and performance of hair care products. J. Cosmet. Sci. 2004, 55, S65–S77. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, W.; Zhang, S.G.; Zhang, J.K.; Chen, S.; Zhu, H.; Ge, S.R. Ageing effects on the diameter, nanomechanical properties and tactile perception of human hair. Int. J. Cosmet. Sci. 2016, 38, 155–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.N.; Lee, S.Y.; Choi, M.H.; Joo, K.M.; Kim, S.H.; Koh, J.S.; Park, W.S. Characteristic features of ageing in Korean women’s hair and scalp. Br. J. Dermatol. 2013, 168, 1215–1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plott, T.J.; Karim, N.; Durbin-Johnson, B.P.; Swift, D.P.; Youngquist, R.S.; Salemi, M.; Phinney, B.S.; Rocke, D.M.; Davis, M.G.; Parker, G.J.; et al. Age-related changes in hair shaft protein profiling and genetically variant peptides. Forensic Sci. Int. Genet. 2020, 47, 102309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thibaut, S.; Becker, E.D.; Bernard, B.A.; Huart, M.; Fiat, F.; Baghdadli, N.; Luengo, G.S.; Leroy, F.; Angevin, P.; Kermoal, A.M.; et al. Chronological ageing of human hair keratin fibres. Int. J. Cosmet. Sci. 2010, 32, 422–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagase, S.; Kajiura, Y.; Mamada, A.; Abe, H.; Shibuichi, S.; Satoh, N.; Itou, T.; Shinohara, Y.; Amemiya, Y. Changes in structure and geometric properties of human hair by aging. J. Cosmet. Sci. 2010, 60, 637–648. [Google Scholar]

- Nagase, S.; Tsuchiya, M.; Matsui, T.; Shibuichi, S.; Tsujimura, H.; Masukawa, Y.; Satoh, N.; Itou, T.; Koike, K.; Tsujii, K. Characterization of curved hair of Japanese women with reference to internal structures and amino acid composition. J. Cosmet. Sci. 2008, 59, 317–332. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hollfelder, B.; Blankenburg, G.; Wolfram, L.J.; Höcker, H. Chemical and physical properties of pigmented and non-pigmented hair (‘grey hair’). Int. J. Cosmet. Sci. 1995, 17, 87–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nogueira, A.C.S.; Joekes, I. Hair color changes and protein damage caused by ultraviolet radiation. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B 2004, 74, 109–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stenn, K.S.; Karnik, P. Lipids to the top of hair biology. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2010, 130, 1205–1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, J.H.; Park, T.S.; Lee, H.J.; Kim, Y.D.; Pi, L.Q.; Jin, X.H.; Lee, W. The ethnic differences of the damage of hair and integral hair lipid after ultra violet radiation. Ann. Dermatol. 2013, 25, 54–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, W. Integral hair lipid in human hair follicle. J. Dermatol. Sci. 2011, 64, 153–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harel, S.; Christiano, A.M. Genetics of structural hair disorders. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2012, 132, E22–E26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coderch, L.; Alonso, C.; Garcia, M.T.; Pérez, L.; Martí, M. Hair lipid structure: Effect of surfactants. Cosmetics 2023, 10, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tokunaga, S.; Tanamachi, H.; Ishikawa, K. Degradation of hair surface: Importance of 18-MEA and epicuticle. Cosmetics 2019, 6, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, S.; Park, H.S.; Lim, B.T.; Son, S.K. Biomimetics through bioconjugation of 16-methylheptadecanoic acid to damaged hair for hair barrier recovery. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 27387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiboutot, D. Regulation of human sebaceous glands. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2004, 123, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nicolaides, N.; Rothman, S. Studies on the chemical composition of human hair fat. II. The overall composition with regard to age, sex and race. J. Investig. Dermatol. 1953, 21, 9–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, M.A.; Martí, M.; Coderch, L.; Carrer, V.; Kreuzer, M.; Barba, C. Lipid loses and barrier function modifications of the brown-to-white hair transition. Skin Res. Technol. 2019, 25, 517–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breakspear, S.; Smith, J.R.; Luengo, G. Effect of the covalently linked fatty acid 18-MEA on the nanotribology of hair’s outermost surface. J. Struct. Biol. 2005, 149, 235–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.; Kim, Y.D.; Pi, L.; Lee, S.Y.; Hong, H.; Lee, W. Comparison of hair shaft damage after chemical treatment in Asian, White European, and African hair. Int. J. Dermatol. 2014, 53, 1103–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masukawa, Y.; Tanamachi, H.; Tsujimura, H.; Mamada, A.; Imokawa, G. Characterization of hair lipid images by argon sputter etching-scanning electron microscopy. Lipids 2006, 41, 197–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takahashi, T.; Mamada, A.; Breakspear, S.; Itou, T.; Tanji, N. Age-dependent changes in damage processes of hair cuticle. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2015, 14, 2–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vyumvuhore, R.; Verzeaux, L.; Gilardeau, S.; Bordes, S.; Aymard, E.; Manfait, M.; Closs, B. Investigation of the molecular signature of greying hair shafts. Int. J. Cosmet. Sci. 2021, 43, 332–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’goshi, K.; Iguchi, M.; Tagami, H. Functional analysis of the stratum corneum of scalp skin: Studies in patients with alopecia areata and androgenetic alopecia. Arch. Dermatol. Res. 2000, 292, 605–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam-Phaure, L. Formulating on Trend: Skinification of Hair. Cosmetics & Toiletries. 2022. Available online: https://www.cosmeticsandtoiletries.com/formulas-products/formulating-basics/article/22288816/cosmetics-toiletries-magazine-formulating-on-trend-skinification-of-hair (accessed on 3 July 2025).

- Chia, V. The ‘Skinification’ of Hair Is the Biggest Beauty Trend Right Now—But What Is It? CNA Lifestyle. 2021. Available online: https://cnalifestyle.channelnewsasia.com/women/beauty-trend-skinification-hair-skincare-haircare-products-280901 (accessed on 3 July 2025).

- Hasegawa, R. The Future of Haircare, Styling & Colour: 2024 [Industry Report]; Mintel: London, UK, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz, J.R.; Henry, J.P.; Kerr, K.M.; Flagler, M.J.; Page, S.H.; Redman-Furey, N. Incubatory environment of the scalp impacts pre-emergent hair to affect post-emergent hair cuticle integrity. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2018, 17, 105–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, W.; Li, L.; Kaijura, S.; Amoh, Y.; Tan, Y.; Liu, F.; Hoffman, R.M. Aging hair follicles rejuvenated by transplantation to a young subcutaneous environment. Cell Cycle 2016, 15, 1093–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chanprapaph, K.; Sutharaphan, T.; Suchonwanit, P. Scalp biophysical characteristics in males with androgenetic alopecia: A comparative study with healthy controls. Clin. Interv. Aging 2021, 16, 781–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, J.R.; Henry, J.P.; Kerr, K.M.; Mizoguchi, H.; Li, L. The role of oxidative damage in poor scalp health: Ramifications to causality and associated hair growth. Int. J. Cosmet. Sci. 2015, 37, 9–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tosti, A.; Schwartz, J.R. Role of scalp health in achieving optimal hair growth and retention. Int. J. Cosmet. Sci. 2021, 43, S1–S8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hori, H.; Moretti, G.; Rebora, A.; Crovato, F. The thickness of human scalp: Normal and bald. J. Investig. Dermatol. 1972, 58, 396–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Florence, P.; Cornillon, C.; D’arras, M.; Flament, F.; Panhard, S.; Diridollou, S.; Loussouarn, G. Functional and structural age-related changes in the scalp skin of Caucasian women. Skin Res. Technol. 2013, 19, 384–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.I.; Kim, J.; Park, S.R.; Ham, S.; Lee, H.J.; Park, C.R.; Kim, H.N.; Kang, B.H.; Jung, I.; Suk, J.M.; et al. Age-related changes in scalp biophysical parameters: A comparative analysis of the 20s and 50s age groups. Skin Res. Technol. 2023, 29, e13433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piérard-Franchimont, C.; Loussouarn, G.; Panhard, S.; Saint Léger, D.; Mellul, M.; Piérard, G.E. Immunohistochemical patterns in the interfollicular Caucasian scalps: Influences of age, gender, and alopecia. Biomed Res. Int. 2013, 2013, 769489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Duan, E. Fighting against skin aging. Cell Transplant. 2018, 27, 729–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunin, A.G.; Petrov, V.V.; Vasilieva, O.V.; Golubtsova, N.N. Age-related changes of blood vessels in the human dermis. Adv. Gerontol. 2015, 5, 65–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, R.; Westgate, G.; Pawlus, A.D.; Sikkink, S.K.; Thornton, M.J. Age-related changes in female scalp dermal sheath and dermal fibroblasts: How the hair follicle environment impacts hair ageing. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2021, 141, 1041–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, S.J.; Kim, J.Y.; Jang, S.; Choi, S.J.; Kim, K.H.; Kwon, O. Decrease of versican levels in the follicular dermal papilla is a remarkable aging-associated change of human hair follicles. J. Dermatol. Sci. 2016, 84, 354–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weihermann, A.C.; Lorencini, M.; Brohem, C.A.; de Carvalho, C.M. Elastin structure and its involvement in skin photoageing. Int. J. Cosmet. Sci. 2017, 39, 241–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston, R.B. Chapter 12—Disorders of elastic tissue. In Weedon’s Skin Pathology Essentials E-Book, 2nd ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2017; pp. 255–265. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, R.; Pawlus, A.D.; Thorton, M.J. Getting under the skin of hair aging: The impact of the hair follicle environment. Exp. Dermatol. 2020, 29, 588–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freitas-Rodríguez, S.; Folgueras, A.R.; López-Otín, C. The role of matrix metalloproteinases in aging: Tissue remodeling and beyond. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Cell Res. 2017, 1864, 2015–2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderi, R.; Makdissy, N.; Azar, A.; Rizk, F.; Hamade, A. Cellular therapy with human autologous adipose-derived adult cells of stromal vascular fraction for alopecia areata. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2018, 9, 141–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicu, C.; O’Sullivan, J.D.B.; Ramos, R.; Timperi, L.; Lai, T.; Farjo, N.; Farjo, B.; Pople, J.; Bhogal, R.; Hardman, J.A.; et al. Dermal adipose tissue secretes HGF to promote human hair growth and pigmentation. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2021, 141, 1633–1645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Festa, E.; Fretz, J.; Berry, R.; Schmidt, B.; Rodeheffer, M.; Horowitz, M.; Horsley, V. Adipocyte lineage cells contribute to the skin stem cell niche to drive hair cycling. Cell 2011, 146, 761–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shook, B.; Gonzalez, G.R.; Ebmeier, S.; Grisotti, G.; Zwick, R.; Horsley, V. The role of adipocytes in tissue regeneration and stem cell niches. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 2016, 32, 609–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, K.N.; Jain, P.; He, C.H.; Eun, F.C.; Kang, S.; Tumbar, T. Skin vasculature and hair follicle cross-talking associated with stem cell activation and tissue homeostasis. Elife 2019, 8, e45977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gur-Cohen, S.; Yang, H.; Baksh, S.C.; Miao, Y.; Levorse, J.; Kataru, R.P.; Liu, X.; de la Cruz-Racelis, J.; Mehrara, B.J.; Fuchs, E. Stem cell-driven lymphatic remodeling coordinates tissue regeneration. Science 2019, 366, 1218–1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peña-Jimenez, D.; Fontenete, S.; Megias, D.; Fustero-Torre, C.; Graña-Castro, O.; Castellana, D.; Loewe, R.; Perez-Moreno, M. Lymphatic vessels interact dynamically with the hair follicle stem cell niche during skin regeneration in vivo. EMBO J. 2019, 38, e101688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pająk, J.; Nowicka, D.; Szepietowski, J.C. Inflammaging and immunosenescence as part of skin aging—A narrative review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 7784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, M.A.; Quan, T.; Voorhees, J.J.; Fisher, G.J. Extracellular matrix regulation of fibroblast function: Redefining our perspective on skin aging. J. Cell Commun. Signal. 2018, 12, 35–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solé-Boldo, L.; Raddatz, G.; Schütz, S.; Mallm, J.; Rippe, K.; Lonsdorf, A.S.; Rodriguez-Paredes, M.; Lyko, F. Single-cell transcriptomes of the human skin reveal age-related loss of fibroblast priming. Commun. Biol. 2020, 3, 188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salzer, M.C.; Lafzi, A.; Berenguer-Llergo, A.; Youssif, C.; Castellanos, A.; Solanas, G.; Peixoto, F.O.; Attolini, C.S.; Prats, N.; Aguilera, M.; et al. Identity noise and adipogenic traits characterize dermal fibroblast aging. Cell 2018, 175, 1575–1590.e22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahoda, C.A.B. Cell movement in the hair follicle dermis—More than a two-way street? J. Investig. Dermatol. 2003, 121, ix–xi. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajran, J.; Gosman, A.A. Anatomy, Head and Neck, Scalp. StatPearls. 2023. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK551565/ (accessed on 4 July 2025).

- Polak-Witka, K.; Rudnicka, L.; Blume-Peytavi, U.; Vogt, A. The role of the microbiome in scalp hair follicle biology and disease. Exp. Dermatol. 2020, 29, 286–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shibagaki, N.; Suda, W.; Clavaud, C.; Bastien, P.; Takayasu, L.; Iioka, E.; Kurokawa, R.; Yamashita, N.; Hattori, Y.; Shindo, C.; et al. Aging-related changes in the diversity of women’s skin microbiomes associated with oral bacteria. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 10567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saxena, R.; Mittal, P.; Clavaud, C.; Dhakan, D.B.; Roy, N.; Breton, L.; Misra, N.; Sharma, V.K. Longitudinal study of the scalp microbiome suggests coconut oil to enrich healthy scalp commensals. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 7220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.K.; Ha, M.; Park, S.; Kim, M.N.; Kim, B.J.; Kim, W. Characterization of the fungal microbiota (mycobiome) in healthy and dandruff-afflicted human scalps. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e32847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez-Perez, G.I.; Gao, Z.; Jourdain, R.; Ramirez, J.; Gany, F.; Clavaud, C.; Demaude, J.; Breton, L.; Blaser, M.J. Body site is a more determinant factor than human population diversity in the healthy skin microbiome. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0151990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lousada, M.B.; Edelkamp, J.; Lachnit, T.; Fehrholz, M.; Jimenez, F.; Paus, R. Laser capture microdissection as a method for investigating the human hair follicle microbiome reveals region-specific differences in the bacteriome profile. BMC Res. Notes 2023, 16, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogai, K.; Nagase, S.; Mukai, K.; Iuchi, T.; Mori, Y.; Matsue, M.; Sugitani, K.; Sugama, J.; Okamoto, S. A comparison of techniques for collecting skin microbiome samples: Swabbing versus tape-stripping. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 2362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakatsuji, T.; Chiang, H.; Jiang, S.B.; Nagarajan, H.; Zenglar, K.; Gallo, R.L. The microbiome extends to subepidermal compartments of normal skin. Nat. Commun. 2013, 4, 1431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rinaldi, F.; Pinto, D.; Borsani, E.; Castrezzati, S.; Amedei, A.; Rezzani, R. The first evidence of bacterial foci in the hair part and dermal papilla of scalp hair follicles: A pilot comparative study in alopecia areata. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 11956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schembri, K.; Scerri, C.; Ayers, D. Plucked human hair shafts and biomolecular medical research. Sci. World J. 2013, 2013, 620531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matard, B.; Meylheuc, T.; Briandet, R.; Casin, I.; Assouly, P.; Cavelier-balloy, B.; Reygagne, P. First evidence of bacterial biofilms in the anaerobe part of scalp hair follicles: A pilot comparative study in folliculitis decalvans. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2012, 27, 853–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paus, R.; Nickoloff, B.J.; Ito, T. A ‘hairy’ privilege. Trends Immunol. 2005, 26, 32–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, K.C.; Klatte, J.E.; Dinh, H.V.; Harries, M.J.; Reithmayer, K.; Meyer, W.; Sinclair, R.; Paus, R. Evidence that the bulge region is a site of relative immune privilege in human hair follicles. Br. J. Dermatol. 2008, 159, 1077–1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cong, T.; Hao, D.; Wen, X.; Li, X.; He, G.; Jiang, X. From pathogenesis of acne vulgaris to anti-acne. Arch. Dermatol. Res. 2019, 311, 337–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabat, R.; Jemec, G.B.E.; Matusiak, Ł.; Kimball, A.B.; Prens, E.; Wolk, K. Hidradenitis suppurativa. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2020, 6, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilhem, K.P.; Cua, A.B.; Maibach, H.I. Skin aging. Effect on transepidermal water loss, stratum corneum hydration, skin surface pH, and causal sebum content. Arch. Dermatol. 1991, 127, 1806–1809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marrakchi, S.; Maibach, H.I. Biophysical parameters of skin: Map of human face, regional, and age-related differences. Contact Dermat. 2007, 57, 28–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farage, M.A.; Miller, K.W.; Elsner, P.; Maibach, H.I. Functional and physiological characteristics of the aging skin. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 2008, 20, 195–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chng, K.C.; Tay, A.; Li, C.; Ng, A.; Wang, J.; Suri, B.K.; Matta, S.A.; McGovern, N.; Janela, B.; Wong, C.; et al. Whole metagenome profiling reveals skin microbiome-dependent susceptibility to atopic dermatitis flare. Nat. Microbiol. 2016, 1, 16106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.; Guichard, A.; Cheng, Y.; Li, J.; Qin, O.; Wang, X.; Liu, W.; Tan, Y. Sensitive scalp is associated with excessive sebum and perturbed microbiome. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2018, 18, 922–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papaccio, F.; D’Arino, A.; Caputo, S.; Bellei, B. Focus on the contribution of oxidative stress in skin aging. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azzimonti, B.; Ballacchino, C.; Zanetta, P.; Cucci, M.A.; Monge, C.; Margherita, G.; Dianzani, C.; Barrera, G.; Pizzimenti, S. Microbiota, oxidative stress, and skin cancer: An unexpected triangle. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krueger, A.; Mohamed, A.; Kolka, C.M.; Stoll, T.; Zaugg, J.; Linedale, R.; Morrison, M.; Soer, H.P.; Hugenholtz, P.; Frazer, I.H.; et al. Skin cancer-associated S. aureus strains can induce DNA damage in human keratinocytes by downregulating DNA repair and promoting oxidative stress. Cancers 2022, 14, 2143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Später, S.; Hipler, U.; Haustein, U.; Nenoff, P. Generation of reactive oxygen species in vitro by Malessezia yeasts. Hautarzt 2009, 60, 122–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trüeb, R.M. Oxidative stress and its impact on skin, scalp and hair. Int. J. Cosmet. Sci. 2021, 43, S9–S13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, G.; Sweren, E.; Andrews, W.; Li, Y.; Chen, J.; Xue, Y.; Wier, E.; Alphonse, M.P.; Luo, L.; Miao, Y.; et al. Commensal microbiome promotes hair follicle regeneration by inducing keratinocyte HIF-1α signalling and glutamine metabolism. Sci. Adv. 2023, 9, eabo7555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šebetić, K.; Masnec, I.S.; Čavka, V.; Biljan, D.; Krolo, I. UV damage of the hair. Coll. Antropol. 2008, 32, 163–165. [Google Scholar]

- Hoting, E.; Zimmerman, M.; Höcker, H. Photochemical alterations in human hair part III: Analysis of melanin. J. Soc. Cosmet. Chem. 1995, 46, 181–190. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, W. Photoaggravation of hair aging. Int. J. Trichology 2009, 1, 94–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, T.A. How Damaged in Hair? Part I: Surface Damage. Cosmetics & Toiletries. 2017. Available online: https://www.cosmeticsandtoiletries.com/testing/sensory/article/21836754/how-damaged-is-hair-part-i-surface-damage (accessed on 4 July 2025).

- Dias, M.F.R.G. Hair cosmetics: An overview. Int. J. Trichology 2015, 7, 2–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robbins, C.R. Interactions of shampoo and crème rinse ingredients with human hair. In Chemical and Physical Behaviour of Human Hair, 4th ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 193–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Torre, C.; Bhushan, B. Nanotribological effects of silicone type, silicone deposition level and surfactant type on human hair using atomic force microscopy. J. Cosmet. Sci. 2006, 57, 37–56. [Google Scholar]

- Mysore, V.; Arghya, A. Hair oils: Indigenous knowledge revisited. Int. J. Trichology 2022, 14, 84–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sang, S.; Akowuah, G.A.; Liew, K.B.; Lee, S.; Keng, J.; Lee, S.; Yon, J.; Tan, C.S.; Chew, Y. Natural alternatives from your garden for hair care: Revisiting the benefits of tropical herbs. Heliyon 2023, 9, e21876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeanneton, O.; Kurfurst, R.; Cavagnino, A.; Notte, D.; Gourguillon, L.; LeBlanc, E.; Nizard, C.; Baraibar, M.; Pays, K. A mixture of honeys and Royal Jelly for protection and repair of Chinese hair from UVA combined with environmental pollution [Poster presentation]. In Proceedings of the European Society for Dermatological Research 50th Annual Meeting, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 28 September–1 October 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Kurfurst, R.; Jeanneton, O.; Cavagnino, A.; Desroches, J.; Nizard, C.; Baraibar, M.; Pays, K. A combination of honey to repair Asian hair from UV-A and environmental pollution-induced damage [Poster presentation]. In Proceedings of the First International Societies for Investigative Dermatology Meeting, Tokyo, Japan, 10–13 May 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, S. What’s New in the ‘Skinification’ of Hair Care? Cosmetics Design-Europe. 2024. Available online: https://www.cosmeticsdesign-europe.com/Article/2024/02/15/Skincare-ingredients-for-hair/ (accessed on 4 July 2025).

- Westgate, G.E.; Grohmann, D.; Moya, M.M. Hair Longevity—Evidence for a multifactorial holistic approach to managing hair aging changes. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 1894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szendzielorz, E.; Spiewak, R. Caffeine as an active molecule in cosmetic products for hair loss: Its mechanisms of action in the context of hair physiology and pathology. Molecules 2025, 30, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szendzielorz, E.; Spiewak, R. Adenosine as an active ingredient in topical preparations against hair loss: A systematic review and meta-analysis of published clinical trials. Biomolecules 2025, 15, 1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habeebuddin, M.; Karnati, R.K.; Shiroorkar, P.N.; Nagaraja, S.; Asdaq, S.M.B.; Anwer, M.K.; Fattepur, S. Topical probiotics: More than a skin deep. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 557–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herbert, S.; Haughton, R.; Nava, J.; Ji-Xu, A.; Le, S.T.; Maverakis, E. A review of topical probiotic therapy for atopic dermatitis. Clin. Exp. Dermatol. 2023, 48, 319–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castiel, I.; Gueniche, A. Cosmetic and Dermatological Use of Probiotic Lactobacillus Paracasei Microorganisms for the Treatment of Greasy Scalp Disorders. European Patent Office EP2149368B1, 30 May 2018. Available online: https://patents.google.com/patent/EP2149368B1/en (accessed on 11 August 2025).

- Yin, C.; Nguyen, T.T.M.; Yi, E.; Zheng, S.; Bellere, A.D.; Zheng, Q.; Jin, X.; Kim, M.; Park, S.; Oh, S.; et al. Efficacy of probiotics in hair growth and dandruff control: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Heliyon 2024, 10, e29539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woo, Y.M.; Seo, J.Y.; Kim, S.; Cha, J.H.; Cho, H.D.; Cha, Y.K.; Jeong, J.T.; Park, S.M.; Ryu, H.S.; Kim, J.M.; et al. Hair growth effect of TS-SCLF from Schisandra chinensis extract fermented with Lactobacillus plantarum. Microbiol. Biotechnol. Lett. 2022, 50, 533–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Jesus, G.F.A.; Rossetto, M.P.; Voytena, A.; Feder, B.; Borges, H.; da Costa Borges, G.; Feuser, Z.P.; Dal-Bó, S.; Michels, M. Clinical evaluation of paraprobiotic-associated Bifidobacterium lactis CCT 7858 anti-dandruff shampoo efficacy: A randomized placebo-controlled clinical trial. Int. J. Cosmet. Sci. 2023, 45, 572–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, W.; Fang, Y.; Huang, T.; Chiang, Y.; Lin, C.; Chang, W. Heat-killed Lacticaseibacillus paracasei GMNL-653 ameliorates human scalp health by regulating scalp microbiome. BMC Microbiol. 2023, 23, 121–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mori-Ichioka, A.; Sunada, Y.; Koikeda, T.; Matsuda, H.; Matsuo, S. Effect of applying Lactiplantibacillus plantarum subsp. plantarum N793 to the scalps of men and women with thinning hair: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group study. Biosci. Microbiota Food Health 2024, 43, 192–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kesika, P.; Sivamaruthi, B.S.; Thangaleela, S.; Bharathi, M.; Chaiyasut, C. Role and mechanisms of phytochemicals in hair growth and health. Pharmaceuticals 2023, 16, 206–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babich, O.; Ivanova, S.; Bakhtiyarova, A.; Kalashnikova, O.; Sukhikh, S. Medicinal plants are the basis of natural cosmetics. Process Biochem. 2025, 154, 35–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; Lee, J. Modulation of hair growth promoting effect by natural products. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13, 2163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, J.Y.; Boo, M.Y.; Boo, Y.C. Can plant extracts help prevent hair loss or promote hair growth? A review comparing their therapeutic efficacies, phytochemical components, and modulatory targets. Molecules 2024, 29, 2288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sennett, R.; Wang, Z.; Rezza, A.; Grisanti, L.; Roitershtein, N.; Sicchio, C.; Mok, K.W.; Heitman, N.J.; Clavel, C.; Ma’ayan, A.; et al. An integrated transcriptome atlas of embryonic hair follicle progenitors, their niche, and the developing skin. Dev. Cell 2015, 34, 577–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, A.; Fang, Y.; Ye, L.; Meng, J.; Wang, X.; Chen, J.; Xu, X. Signaling pathways in hair aging. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2023, 11, 1278278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forraz, N.; Kurfurst, R.; Jeanneton, O.; Desroches, A.; Payen, P.; Milet, C.; Vialle, A.; Choisy, P.; Nizard, C.; Pays, K.; et al. Stimulation of the KLF4 pathway by bee products modulates the progression of hair anagen to telogen molecular switch [Paper presentation]. In Proceedings of the International Federation of Societies of Cosmetic Scientists 2022 Congress, London, UK, 19–22 September 2022. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lim, Y.S.; Nizard, C.; Pays, K.; Brun, C.; Kurfurst, R. A Multifaceted View on Ageing of the Hair and Scalp. Cosmetics 2025, 12, 284. https://doi.org/10.3390/cosmetics12060284

Lim YS, Nizard C, Pays K, Brun C, Kurfurst R. A Multifaceted View on Ageing of the Hair and Scalp. Cosmetics. 2025; 12(6):284. https://doi.org/10.3390/cosmetics12060284

Chicago/Turabian StyleLim, Yi Shan, Carine Nizard, Karl Pays, Cecilia Brun, and Robin Kurfurst. 2025. "A Multifaceted View on Ageing of the Hair and Scalp" Cosmetics 12, no. 6: 284. https://doi.org/10.3390/cosmetics12060284

APA StyleLim, Y. S., Nizard, C., Pays, K., Brun, C., & Kurfurst, R. (2025). A Multifaceted View on Ageing of the Hair and Scalp. Cosmetics, 12(6), 284. https://doi.org/10.3390/cosmetics12060284