Abstract

Skin hydration is fundamental for maintaining epidermal barrier integrity and overall skin homeostasis. Beyond traditional moisturizing agents, recent research has highlighted the role of aquaporins (AQPs), transmembrane water channels, in regulating epidermal hydration, barrier function, and cellular signalling. Among them, aquaporin-3 (AQP3), predominantly expressed in keratinocytes, has attracted particular attention due to its involvement in water and glycerol transport. Dysregulation of AQP expression has been associated with impaired barrier function, inflammatory skin disorders, and ageing. Growing evidence suggests that specific cosmetic ingredients and bioactive compounds, including glycerol, glyceryl glucoside, isosorbide dicaprylate, urea, retinoids, bakuchiol, peptides, plant extracts, and bacterial ferments, can modulate AQP3 expression, thereby improving skin hydration and resilience. Despite promising in vitro data, clinical evidence remains limited, mainly due to methodological and ethical constraints associated with assessing aquaporin expression in vivo. Nonetheless, aquaporins represent promising molecular targets for innovative cosmetic strategies aimed at enhancing hydration, promoting regeneration, and counteracting photoageing. Furthermore, AQP modulation may improve dermal delivery of active substances, providing new perspectives for advanced skincare formulation design. While the available evidence supports their cosmetic potential, emerging discussions on the safety of long-term AQP upregulation highlight the need for continued research and careful evaluation of such ingredients. Future studies should focus on elucidating the molecular mechanisms underlying AQP regulation and validating these findings in human clinical models.

1. Introduction

Skin hydration plays a fundamental role in maintaining both the epidermal barrier and overall skin homeostasis. Although the term “moisturization” is often used to describe this process, such wording may oversimplify its physiological importance by framing it mainly as a cosmetic concern. In reality, water acts as an essential plasticizing component of the stratum corneum, and insufficient hydration can lead to microfissures and barrier disruption of clinical significance. The capacity of the stratum corneum to retain water depends largely on the structure and condition of its corneocytes, particularly those in the outermost layers, while cells in the deeper stratum corneum remain relatively dehydrated and display limited ability to absorb water even under hypotonic conditions [1,2]. Proper hydration of the skin is therefore not only a cosmetic attribute but a physiological necessity for maintaining epidermal homeostasis. Well-hydrated skin is typically associated with a healthy, youthful, and radiant appearance, whereas dehydration contributes to dullness, fine lines, and wrinkles. Moreover, altered hydration accompanies several dermatological conditions, such as xerosis and atopic dermatitis, further emphasizing its medical relevance. Consequently, strategies to support or restore optimal skin hydration have become a central focus of both dermatological and cosmetic research, reflecting the intersection of health and esthetics [3,4].

The skin serves as the body’s first line of defence, protecting against excessive transepidermal water loss (TEWL) through several mechanisms, including the unique hydro–lipid organization of the outermost epidermal layer, the stratum corneum. The principal factors contributing to epidermis hydration include the natural moisturizing factor (NMF), ceramides, and aquaporins (AQPs) [2,5]. Moreover, hyaluronic acid, a glycosaminoglycan with outstanding water-binding capability, although primarily localized in the extracellular matrix of dermis, also contributes to hydration of the stratum corneum [5,6]. The NMF is a hydrophilic mixture of endogenous compounds derived from the degradation of filaggrin into amino acids, which subsequently undergo enzymatic and non-enzymatic transformations. Together, these amino acids and their metabolites, such as pyrrolidone carboxylic acid (PCA) and trans urocainic acid, ensure optimal hydration of the stratum corneum due to their ability to bind water molecules. Moreover, NMF contains inorganic salts, sugars, as well as lactic acid and urea, also acting as effective humectants [1,3,7,8]. Ceramides are natural sphingolipids that play a central role in maintaining the skin’s barrier properties by preventing water loss from deeper epidermal layers. They were also shown to regulate pH, control inflammation, and enhance skin function and appearance. However, ceramides are widely used in cosmetic formulations; their high molecular weight limits effective penetration through the epidermis [9,10]. Aquaporins are a family of transmembrane proteins that facilitate water transport across the lipid bilayers of cell membranes. Some members of this family also enable the passage of small hydrophilic molecules and ions. Among them, AQP3 has received particular attention for its role in regulating skin hydration and barrier function [11]. In recent years, accumulating evidence has suggested that aquaporins represent promising molecular targets for therapeutic modulation using pharmacological agents or bioactive cosmetic compounds. This review aims to summarize the current understanding of aquaporin function in skin physiology and to highlight its potential modulation by cosmetic ingredients.

2. Methodology of Literature Search

The literature search was conducted using the PubMed database. The following search terms were applied: “aquaporin skin”, “aquaporin skin hydration”, and “aquaporin cosmetic”. The search was limited to articles published within the last five years. Publications relevant to the scope of this review were selected from the retrieved records, with particular emphasis on studies evaluating the effects of cosmetically relevant compounds on aquaporin expression. Due to the temporal restriction of the search, the review primarily included cosmetic ingredients and raw materials described in recent years.

In addition, a complementary search was performed in PubMed to identify information on well-established cosmetic ingredients for which study results were published more than five years ago, but which are used in the cosmetic market. To provide a broader context on selected topics, such as the general structure of aquaporins, their distribution in tissues other than skin, and safety considerations, additional searches using the terms “aquaporin” and “aquaporin skin cancer” were also conducted.

3. General Characteristics of Aquaporins and Their Function in Physiology and Pathophysiology of Skin

The aquaporins form a family of transmembrane proteins responsible for osmotically driven water transport. 13 aquaporins (AQP0-12) have already been cloned from humans and are categorized into distinct subgroups: classical water-selective AQPs (AQPs 0, 1, 2, 4, 5, 6, and 8), AQPs transporting water and other small water-soluble substances such as glycerol and urea (AQPs 3, 7, 9 and 10), and unorthodox AQPs (AQPs 11 and 12), which are localized in the intracellular endoplasmic reticulum. The classification is based not only on their molecular functions but also on their amino acid sequence [12,13].

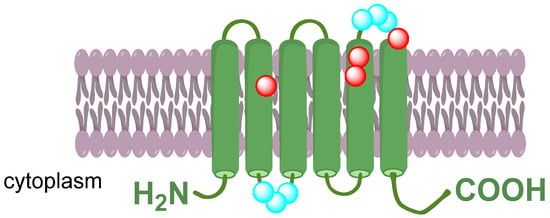

Aquaporins are tetramers, with each monomer forming a functional water channel independently. Furthermore, a central pore is formed in the homotetramer, facilitating the transport of liquids. Each monomer is composed of 6 α-helical transmembrane domains. Their polypeptide structure is formed by a single chain consisting of approximately 270–295 amino acids. Amino (N) and carboxyl (C) terminals are located in the cytoplasm and are responsible for the specific regulation of aquaporin activity. An asparagine–proline–alanine (NPA) motif is shared among all AQPs polypeptide chains and is believed to play a pivotal role in pore formation [14,15,16]. The aromatic/arginine selectivity filter region (ar/R) is located near the channel’s entrance. It functions as a crucial selectivity filter by physically restricting the channel entry. Additionally, the positive charge of the arginine residue repels positively charged ions (Figure 1) [17,18,19]

Figure 1.

Schematic structure of the AQP monomer formed by six transmembrane domains connected with five loops. Two asparagine–proline–alanine (NPA) motifs (highlighted in blue) are located oppositely in loops B and E to form the channel. The aromatic/arginine selectivity filter region (ar/R) is formed by residues highlighted in red.

The aquaporin family shows a diverse pattern of expression across different tissues. Specific aquaporins are characteristic for nervous system (AQP1, AQP4, AQP9, AQP11) and eyes (AQP0, AQP3), respiratory tract (AQP1, AQP5, AQP8), renal tract and kidneys (AQP1, AQP2, AQP6, AQP7, AQP11), gastrointestinal tract (AQP8, AQP9, AQP10, AQP12), and cardiovascular system (AQP1, AQP7, AQP11) [12,13]. In the skin, at least six aquaporins have been identified: AQP1, AQP3, AQP5, AQP7, AQP9, and AQP10. Among the aquaporin family members expressed in the skin, AQP3 is considered the most functionally relevant, playing a central role in epidermal hydration and barrier homeostasis [20].

AQP3 is predominantly expressed in keratinocytes, in the basal layer and stratum spinosum of epidermis in normal skin. Its primary role is related to glycerol transport into the more superficial layers of the epidermis and the stratum corneum, and glycerol plays a role as an endogenous humectant. Much of the current understanding of the physiological role of aquaporins comes from mouse models in which the AQP3 gene was disrupted. These studies demonstrated that animals lacking AQP3 exhibited reduced glycerol concentrations in the epidermis and stratum corneum, which in turn resulted in decreased water content, diminished skin elasticity, and delayed epidermal wound healing [1,21,22].

AQP9 in the skin is mainly localized in the upper stratum granulosum of the human epidermis. In addition to water and water-soluble substances transport and thus skin hydration, its role involves the differentiation of keratinocytes and the wound-healing process [23,24]. APQ5 is localized in the sweat glands, contributing to sweat secretion, thermoregulation and local water balance [13,25]. APQ1 is localized in vascular endothelial cells, keratinocytes, melanocytes, and fibroblasts. Its role involves proper microcirculation, cell migration and skin hydration [13,26]. APQ7 is expressed in Langerhans cells, dermal dendritic cells, and adipocytes. It is involved in cell migration and immune surveillance, as well as maintenance of proper glycerol levels [27,28]. AQP10 is expressed in keratinocytes and takes part in the proper maintenance of barrier function [13,29].

Aquaporins have emerged as important regulators of epidermal homeostasis, and their dysregulation has been increasingly implicated in the pathogenesis of several inflammatory skin diseases. Altered AQPs expression has been reported in conditions such as atopic dermatitis (AD), psoriasis (PS), and hidradenitis suppurativa (HS), all of which are associated with impaired skin barrier function. In AD lesions, a marked upregulation of AQP3 expression has been observed, which may enhance abnormal keratinocyte proliferation and contribute to the defective epidermal barrier and excessive transepidermal water loss (TEWL). In contrast, psoriatic lesions typically exhibit reduced AQP3 levels, resulting in diminished skin hydration and increased TEWL. Moreover, AQP3 has been shown to facilitate the transport of hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) into keratinocytes, thereby activating the NF-κB signalling pathway and amplifying inflammatory responses characteristic of psoriasis. In HS, downregulation of AQP5 has been documented, potentially affecting sweat secretion and keratinocyte differentiation [13]. Additionally, studies conducted in patients with rosacea and in a mouse rosacea-like skin inflammation model demonstrated that AQP3 is highly expressed in keratinocytes and CD4+ T cells. These findings indicate that AQP3 functions as a proinflammatory regulator contributing to the pathogenesis of rosacea, while at the same time representing a potential therapeutic target for this condition [30].

Moreover, aquaporin-3 expression has been reported to increase during wound healing, where it supports epidermal cell migration and proliferation [31,32]. Both AQP1 and AQP3 have been suggested as promising markers for determining wound age, given that their expression in vascular endothelial cells and keratinocytes, respectively, increases proportionally with wound maturation [33]. Recent histopathological studies have examined aquaporin expression in human skin samples collected from injury sites of individuals who sustained various types of trauma, including blunt and sharp force injuries, strangulation marks, burns, gunshot wounds, and frost erythema. Across all examined forms of mechanical or thermal damage, a consistent increase in aquaporin-3 expression was observed in the keratinocytes of the epidermis, independent of factors such as age, sex, body mass index, agonal period, or postmortem interval. In contrast, aquaporin-1 levels did not differ between injured and uninjured skin. These findings suggest that AQP3 expression is independent of the type of injury and may serve as a valuable immunohistochemical marker of wound vitality [34].

Aquaporin expression in the skin is significantly altered during ageing and in response to environmental stressors such as ultraviolet (UV) radiation and oxidative stress. AQP3 levels decrease in both chronologically aged and UVA-exposed skin, contributing to impaired autophagy, reduced cellular viability, and increased senescence in dermal fibroblasts. Environmental factors, including oxidative agents like H2O2, further modulate AQP3 and AQP8 expression, affecting intracellular signalling, stress responses, and inflammation. Dysregulation of aquaporins disrupts water and small molecule transport, exacerbating skin dehydration and barrier dysfunction. These findings highlight the pivotal role of AQPs in maintaining skin homeostasis and suggest that targeting their expression may mitigate photoageing and environmental damage [35]. AQP3 has emerged as a promising molecular target in anti-ageing skincare due to its key role in regulating autophagy in human dermal fibroblasts. Studies have shown that short-term UVA exposure upregulates AQP3 and induces autophagy, whereas long-term UVA exposure suppresses AQP3 expression, inhibits autophagy, and triggers cellular senescence. Experimental modulation of AQP3 demonstrated that its overexpression can prevent UVA-induced senescence, highlighting its protective function against photoageing. These findings suggest that targeting AQP3 may offer novel strategies to mitigate skin ageing and preserve youthful skin [36].

4. Cosmetic Ingredients Targeting Aquaporins

Aquaporins constitute intriguing molecular targets in cosmetology due to their key role in skin hydration and homeostasis. Consequently, a variety of cosmetic raw materials and bioactive compounds with potential relevance to skincare have been investigated as aquaporin modulators. Studies have demonstrated that several of these substances are capable of modulating the expression and/or aquaporin content, particularly AQP3, which, due to its localization in keratinocytes, is the most extensively studied isoform in the cosmetic context.

The strongest evidence supporting the activity of cosmetic ingredients acting through aquaporin modulation comes from human studies. However, only a limited number of such examples can be found in the literature. For instance, in one study, topical application of glyceryl glucoside on the forearm skin for seven days resulted in increased expression of aquaporin 3, as demonstrated in suction blister samples collected from study participants, along with a statistically significant improvement in skin hydration and a reduction in transepidermal water loss (TEWL) [37]. In another study, the application of a hyaluronan mask for only 15–25 min led to an upregulation of aquaporin expression, confirmed in appropriately stained microscopic sections of skin obtained after the cosmetic procedure [38]. Equally limited are the reports describing the activity of cosmetic ingredients in animal models, including rat [39] and mouse studies [40]. By contrast, ex vivo and in vitro experiments, performed on human skin explants or reconstructed epidermis models, are reported much more frequently. In these studies, enhanced expression of aquaporin 3 has been demonstrated for a variety of compounds, including retinol, bakuchiol, astaxanthin, isosorbide dicaprylate, as well as several plant extracts and bacterial ferments. The data on cosmetic raw materials tested in these experimental models, showing AQP3 upregulation, are summarized in Table 1. The table also includes information on other biological activities evaluated for these ingredients, not necessarily related to aquaporin modulation. However, these findings may provide valuable insights into potential directions for their practical application in cosmetology.

Table 1.

Bioactive ingredients and cosmetic interventions reported to upregulate aquaporin 3 expression in in vivo studies as well as in vitro studies utilizing skin models.

Evidence of lesser strength comes from in vitro studies employing human skin cells. Most frequently, human keratinocytes are used for this purpose, and occasionally fibroblasts. Such in vitro evidence demonstrating the influence of cosmetic raw materials on AQP3 expression is considerably more abundant. Compounds shown to stimulate AQP3 expression in human keratinocytes include urea [2], glycerol [50], glyceryl glucoside [41], retinol [45], retinoic acid [23], bakuchiol, astaxanthin [46], glycolic acid [51], and apigenin [52]. Moreover, certain peptides and their derivatives, as well as numerous plant extracts and bacterial fermentation products, have been reported to enhance AQP3 expression.

For most of the cosmetic ingredients cited in this review, the precise molecular mechanisms remain incompletely elucidated, meaning that the specific receptor, ligand, and downstream signalling pathway leading to aquaporin-3 (AQP3) modulation in human skin have not yet been identified. Existing evidence from studies on keratinocytes and other cell types suggests that AQP3 expression may be regulated via nuclear hormone receptors such as peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPARγ) and liver X receptor (LXR) [53]. Astaxanthin represents one of the few cosmetic-relevant compounds for which a direct molecular mechanism has been demonstrated: it acts as a PPARγ agonist and induces LXR expression, thereby contributing to AQP3 upregulation [46]. Additionally, there is evidence indicating that compounds with antioxidant activity may indirectly enhance AQP3 expression. Although the precise molecular pathway is not fully defined, it appears that the reduction in reactive oxygen species and oxidative stress associated with antioxidant activity is accompanied by increased AQP3 levels [46,54]. These observations suggest that, in the context of cosmetology, antioxidant properties of certain compounds may contribute to the modulation of aquaporins and support skin hydration.

A literature review has shown that the ability to increase aquaporin expression has been demonstrated for numerous cosmetic raw materials from diverse chemical groups, which may indicate that the mechanisms underlying AQP3 modulation in the skin are varied and not strictly dependent on the chemical structure of the compound. This suggests that the enhancement of AQP3 expression may be achieved through indirect mechanisms, such as the modulation of signalling pathways in keratinocytes, effects on cellular homeostasis, oxidative stress, or the lipid composition of the epidermis, rather than through direct binding to the AQP3 protein. From a cosmetological perspective, this indicates that there are multiple approaches to achieving the desired effects on skin hydration and barrier function via aquaporin stimulation. The diversity of active cosmetic ingredients, including humectants, peptides, plant extracts, and bacterial ferments, demonstrates that AQP3 represents a promising and functionally validated molecular target in modern cosmetology, and its modulation can be leveraged for the design of innovative skincare strategies.

Detailed information on bioactive ingredients and extracts with cosmetic relevance reported to upregulate aquaporin 3 expression, of which activity was proved only in vitro in human keratinocytes or fibroblasts, is summarized in Table 2. It also includes a description of additional activities that have been investigated, not necessarily related to the modulation of aquaporin-3 expression. However, these findings appear to be relevant as they may indicate potential directions for their application in cosmetology.

Table 2.

Bioactive ingredients and extracts with cosmetic relevance reported to upregulate aquaporin 3 expression in in vitro studies utilizing human keratinocytes or fibroblasts.

In addition, retinoic acid has been shown to suppress AQP9 expression in normal human epidermal keratinocytes (NHEK) [23], whereas peptides derived from spent yeast waste streams increased AQP9 expression in human keratinocytes (HaCaT), demonstrating anti-ageing activity and modulation of skin metabolism [73]. Some studies have also reported increased AQP3 expression following oral supplementation with certain bioactive materials, including oyster hydrolysate, tested in a UVB-induced skin damage model in SKH1 hairless mice. In addition to upregulating AQP3, oral administration of oyster hydrolysate exhibited antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects, improved skin hydration and barrier function, and demonstrated therapeutic potential against photoageing [74]. For isosorbide dicaprylate, an increase in AQP3 expression has been demonstrated in vitro using a full-thickness skin substitute model, accompanied in vivo by enhanced skin hydration and a reduction in TEWL [37]. Importantly, this ingredient was also evaluated in a four-week prospective, randomized, double-blind, vehicle-controlled study conducted in patients with atopic dermatitis [75]. Last but not least, one of the most widely used moisturizing ingredients in cosmetics, glycerol, is naturally transported through AQP3 and has also been shown to upregulate its expression following topical application [50].

5. Current Challenges, Future Perspectives and Safety Concerns of Aquaporins in Cosmetology

5.1. In Vitro–In Vivo Correlation Challenge

Aquaporins, particularly aquaporin-3, have gained increasing recognition as important molecular players in skin physiology and as promising targets in modern cosmetology. This is reflected in the growing number of cosmetic formulations and raw materials on the market that are promoted as “AQP3 activators” or “aquaporin boosters”, including isosorbide dicaprylate and glyceryl glucoside. Their inclusion in commercial products suggests that the cosmetic industry has acknowledged their potential role in enhancing skin hydration and barrier function.

However, despite this growing interest, aquaporins cannot yet be regarded as fully established molecular targets in cosmetology. The primary limitation lies in the scarcity of reliable in vivo data, especially from well-designed human clinical trials. Most available evidence derives from in vitro experiments conducted on cultured keratinocytes or reconstructed epidermis, while in vivo studies are largely confined to animal models. Consequently, many of the beneficial effects observed in humans, such as improved hydration or skin elasticity, are extrapolated from in vitro findings demonstrating enhanced AQP3 expression.

This gap in clinical evidence is not necessarily due to a lack of biological activity but rather reflects the methodological and ethical challenges associated with direct in vivo evaluation. Assessing aquaporin expression in human skin would require invasive tissue sampling, which is difficult to justify in studies involving healthy volunteers. While such procedures may be acceptable in dermatological research on wound healing or pathological conditions, obtaining biopsies from intact, cosmetically treated skin poses substantial ethical barriers. Furthermore, cosmetics are not legally required to undergo controlled clinical testing, which further limits the generation of robust in vivo data.

As a result, most investigations into the effects of cosmetic ingredients on aquaporins focus on indirect functional parameters, such as skin hydration, TEWL, or elasticity, rather than direct molecular assessment. Nevertheless, fundamental insights into the role of aquaporins in skin hydration and barrier homeostasis have largely emerged from animal models, which laid the groundwork for current cosmetic applications.

Future research should therefore aim to bridge the gap between molecular and functional evidence by elucidating the mechanisms through which topical agents modulate aquaporin expression and activity in human skin. Such studies could provide a stronger scientific basis for considering aquaporins as validated molecular targets in cosmetology.

5.2. Current Research Drives Future Directions

As summarized in Table 1 and Table 2, numerous cosmetic ingredients and cosmetically relevant raw materials have been shown to stimulate the expression of aquaporin-3, an essential water and glycerol channel predominantly expressed in keratinocytes. It is noteworthy that for several of these ingredients, such as glycerol, hyaluronic acid, and urea, their beneficial effects on skin hydration had been recognized long before their ability to enhance AQP3 expression was elucidated. This advancement has been made possible by the development of molecular biology and analytical techniques, which have enabled the identification of specific molecular targets and continue to drive innovation in cosmetic science.

A particularly illustrative example is glycerol, one of the most widely used moisturizing agents in both cosmetic and dermatological formulations. Studies in AQP3-deficient mice demonstrated markedly reduced stratum corneum hydration and skin elasticity. Subsequent research revealed that these effects were primarily due to decreased epidermal glycerol content, resulting from impaired transport from deeper skin layers. Topical or oral administration of glycerol restored skin hydration, providing compelling evidence for the physiological role of AQP3 in skin moisture homeostasis. These findings not only reinforced the rationale for the common use of glycerol in moisturizing cosmetics but also sparked interest in the broader involvement of AQP3 in skin health and disease [22,76,77,78]. Another promising direction for the cosmetic application of aquaporin activators lies in anti-ageing formulations. It has been demonstrated that aquaporin expression in the skin is significantly altered during ageing and under environmental stressors such as ultraviolet radiation and oxidative stress. Consequently, modulation of AQP3 expression has emerged as a potential strategy not only for maintaining epidermal hydration but also for structural integrity in ageing skin. Although current evidence on the molecular mechanisms underlying age-related changes in aquaporin expression remains limited, future studies may help to clarify these pathways and support the rational design of novel bioactive ingredients with moisturizing, regenerative, and anti-ageing potential, properties highly valued by both the cosmetic industry and consumers.

Aquaporins may also represent promising molecular targets for enhancing the skin permeation of active ingredients. A recent study reported encouraging results for an encapsulated form of tranexamic acid in this context. In vivo experiments conducted in a murine model demonstrated that topical application of an emulsion containing the novel encapsulated form of tranexamic acid to the dorsal skin of mice significantly increased the expression of aquaporin-1 and aquaporin-3. The upregulation of these water channel proteins may not only improve the transport of water and glycerol but also facilitate the permeation of small hydrophilic molecules across the stratum corneum, thereby enhancing their dermal bioavailability. Such findings highlight the potential of aquaporin-targeted strategies to optimize the delivery and efficacy of active substances in dermatological and cosmetic formulations [79].

5.3. Safety Concerns Related to Upregulation of Aquaporins in Cosmetology

The present article has focused primarily on the beneficial aspects of increasing AQP3 expression in the skin, which may have potential applications in cosmetology, particularly in moisturizing formulations. However, some studies have suggested a possible association between enhanced AQP3 expression and tumour formation, as well as a tendency toward aquaporin overexpression in certain skin cancers, including human squamous cell carcinoma and melanoma [80,81,82]. It has been demonstrated that AQP3 plays a crucial role in skin carcinogenesis, as AQP3-knockout mice do not develop tumours even after exposure to chemical carcinogens [81]. From a physiological standpoint, increased glycerol transport through AQP3 in cancer cells has been shown to contribute to ATP synthesis and cell cycle alterations, thereby promoting cell proliferation [83,84]. Moreover, AQP3 has also been identified as a channel for hydrogen peroxide (H2O2). When AQP3 is overexpressed, elevated intracellular levels of H2O2 can lead to oxidative stress and activation of molecular pathways that promote inflammation, tumour growth, angiogenesis, and metastasis, ultimately facilitating tumour malignancy [85,86]. Recent studies in human melanoma cell lines (MNT1 and A375) confirmed increased expression of AQP3 and AQP11 and further demonstrated that inhibition of AQP3 expression suppresses melanoma cell adhesion, proliferation, and migration. Consequently, AQP3 inhibitors have emerged as promising therapeutic candidates not only for melanoma but also for other hyperproliferative skin disorders [32,84,87]. On the other hand, some reports have described reduced AQP3 expression in squamous cell carcinoma and basal cell carcinoma, though this downregulation has also been associated with excessive proliferation of cancer cells [88,89]. Despite these discrepancies, all authors consistently emphasize a link between altered AQP3 expression and skin conditions characterized by uncontrolled cellular proliferation.

These findings have led to the appearance of cautionary notes in the scientific literature, highlighting that cosmetic ingredients capable of upregulating AQP3 expression may contribute to tumour development under certain conditions [80,90]. Therefore, aquaporins may be considered ambiguous molecular targets, potentially beneficial for maintaining skin hydration, yet possibly risky if their modulation disrupts cellular homeostasis.

The safety of aquaporin enhancers in cosmetology is particularly relevant given that most published studies focus exclusively on their beneficial effects. It has been clearly indicated that further research is warranted, including epidemiological studies among individuals using cosmetics designed to enhance aquaporin expression. Some authors have also suggested that a reconsideration of preclinical testing in animal models might be justified to ensure consumer safety before such products reach the market [90].

6. Conclusions

Well-hydrated skin is synonymous with a healthy and youthful appearance, while adequate hydration also contributes to consumer comfort and skin barrier stability. Established cosmetic strategies to improve skin hydration rely on moisturizers and emollients, whereas more recent approaches emphasize the biological role of aquaporins, transmembrane water channels facilitating water transport across the lipid membranes of epidermal cells. Several cosmetic ingredients have been reported to modulate AQP3 expression, thereby enhancing epidermal hydration. However, most of these findings originate from in vitro studies, which, although mechanistically informative, remain limited in their translational relevance.

The most reliable human in vivo evidence currently available supports the activity of glyceryl glucoside and hyaluronic acid, both of which have been shown in human studies to increase AQP3 expression, improve skin hydration, and reduce transepidermal water loss. These results provide a solid foundation for further exploration of aquaporins as molecular targets in modern cosmetology.

Nonetheless, as aquaporin-focused strategies continue to gain attention, their safety aspects should not be overlooked. Emerging data on the complex role of AQP3 in skin physiology and pathology highlight the need for careful evaluation of long-term effects associated with its upregulation. Future research should therefore aim to confirm the efficacy of AQP-modulating ingredients in well-designed clinical studies, while simultaneously addressing potential safety considerations to ensure consumer protection.

Funding

This research was funded by Jagiellonian University Medical College grant number N42/DBS/000391.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this manuscript, the author used ChatGPT 5.1 for the purposes of text correction, improvement and/or translation from Polish. The author have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Choi, E.H.; Man, M.Q.; Wang, F.; Zhang, X.; Brown, B.E.; Feingold, K.R.; Elias, P.M. Is Endogenous Glycerol a Determinant of Stratum Corneum Hydration in Humans? J. Investig. Dermatol. 2005, 125, 288–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Draelos, Z.D. Modern Moisturizer Myths, Misconceptions, and Truths. Cutis 2013, 91, 308–314. [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin, H.; Del Rosso, J. Going Beyond Ceramides in Moisturizers: The Role of Natural Moisturizing Factors. J. Drugs Dermatol. 2024, 23, 466–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Draelos, Z.D.; Nelson, D.B. In Vitro and In Vivo Evaluation of an Emollient-Rich Moisturizer Developed to Address Three Critical Elements of Natural Moisturization. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2025, 24, e70085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verdier-Sévrain, S.; Bonté, F. Skin Hydration: A Review on Its Molecular Mechanisms. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2007, 6, 75–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDaniel, D.H.; Dover, J.S.; Wortzman, M.; Nelson, D.B. In Vitro and in Vivo Evaluation of a Moisture Treatment Cream Containing Three Critical Elements of Natural Skin Moisturization. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2020, 19, 1121–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallinger, J.; Kuhn, A.; Wessel, S.; Behm, P.; Heinecke, S.; Filbry, A.; Hillemann, L.; Rippke, F. Depth-Dependent Hydration Dynamics in Human Skin: Vehicle-Controlled Efficacy Assessment of a Functional 10% Urea plus NMF Moisturizer by near-Infrared Confocal Spectroscopic Imaging (KOSIM IR) and Capacitance Method Complemented by Volunteer Perception. Ski. Res. Technol. 2022, 28, 342–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fowler, J. Understanding the Role of Natural Moisturizing Factor in Skin Hydration. Pract. Dermatol. 2012, 9, 36–40. [Google Scholar]

- Yong, T.L.; Zaman, R.; Rehman, N.; Tan, C.K. Ceramides and Skin Health: New Insights. Exp. Dermatol. 2025, 34, e70042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahraman, E.; Kaykın, M.; Bektay, H.Ş.; Güngör, S. Recent Advances on Topical Application of Ceramides to Restore Barrier Function of Skin. Cosmetics 2019, 6, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verkman, A.S. Aquaporins. Curr. Biol. 2013, 23, R52–R55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bozkurt, A.; Halici, H.; Yayla, M. Aquaporins: Potential Targets in Inflammatory Diseases. Eurasian J. Med. 2023, 55, S106–S113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricarico, P.M.; Mentino, D.; De Marco, A.; Del Vecchio, C.; Garra, S.; Cazzato, G.; Foti, C.; Crovella, S.; Calamita, G. Aquaporins Are One of the Critical Factors in the Disruption of the Skin Barrier in Inflammatory Skin Diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 4020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adeoye, A.; Odugbemi, A.; Ajewole, T. Structure and Function of Aquaporins: The Membrane Water Channel Proteins. Biointerface Res. Appl. Chem. 2022, 12, 690–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonen, T.; Walz, T. The Structure of Aquaporins. Q. Rev. Biophys. 2006, 39, 361–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, L.S.; Kozono, D.; Agre, P. From Structure to Disease: The Evolving Tale of Aquaporin Biology. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2004, 5, 687–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gössweiner-Mohr, N.; Siligan, C.; Pluhackova, K.; Umlandt, L.; Koefler, S.; Trajkovska, N.; Horner, A. The Hidden Intricacies of Aquaporins: Remarkable Details in a Common Structural Scaffold. Small 2022, 18, 2202056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kitchen, P.; Salman, M.M.; Pickel, S.U.; Jennings, J.; Törnroth-Horsefield, S.; Conner, M.T.; Bill, R.M.; Conner, A.C. Water Channel Pore Size Determines Exclusion Properties but Not Solute Selectivity. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 20369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, B.; Beitz, E. Aquaporins with Selectivity for Unconventional Permeants. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2007, 64, 2413–2431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hara-Chikuma, M.; Verkman, A.S. Aquaporin-3 Functions as a Glycerol Transporter in Mammalian Skin. Biol. Cell 2005, 97, 479–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonghui, M.; Hara, M.; Sougrat, R.; Verbavatz, J.M.; Verkman, A.S. Impaired Stratum Corneum Hydration in Mice Lacking Epidermal Water Channel Aquaporin-3. J. Biol. Chem. 2002, 277, 17147–17153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hara, M.; Verkman, A.S. Glycerol Replacement Corrects Defective Skin Hydration, Elasticity, and Barrier Function in Aquaporin-3-Deficient Mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2003, 100, 7360–7365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugiyama, Y.; Yamazaki, K.; Kusaka-Kikushima, A.; Nakahigashi, K.; Hagiwara, H.; Miyachi, Y. Analysis of Aquaporin 9 Expression in Human Epidermis and Cultured Keratinocytes. FEBS Open Bio 2014, 4, 611–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojek, A.M.; Skowronski, M.T.; Füchtbauer, E.-M.; Füchtbauer, A.C.; Fenton, R.A.; Agre, P.; Frøkiaer, J.; Nielsen, S. Defective Glycerol Metabolism in Aquaporin 9 (AQP9) Knockout Mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104, 3609–3614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Converse, C.; Lyons, M.C.; Hsu, W.H. Neural Control of Sweat Secretion: A Review. Br. J. Dermatol. 2018, 178, 1246–1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leitch, V.; Agre, P.; King, L.S. Altered Ubiquitination and Stability of Aquaporin-1 in Hypertonic Stress. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2001, 98, 2894–2898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hara-Chikuma, M.; Sugiyama, Y.; Kabashima, K.; Sohara, E.; Uchida, S.; Sasaki, S.; Inoue, S.; Miyachi, Y. Involvement of Aquaporin-7 in the Cutaneous Primary Immune Response through Modulation of Antigen Uptake and Migration in Dendritic Cells. FASEB J. 2012, 26, 211–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hibuse, T.; Maeda, N.; Nagasawa, A.; Funahashi, T. Aquaporins and Glycerol Metabolism. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Biomembr. 2006, 1758, 1004–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jungersted, J.M.; Bomholt, J.; Bajraktari, N.; Hansen, J.S.; Klærke, D.A.; Pedersen, P.A.; Hedfalk, K.; Nielsen, K.H.; Agner, T.; Hélix-Nielsen, C. In Vivo Studies of Aquaporins 3 and 10 in Human Stratum Corneum. Arch. Dermatol. Res. 2013, 305, 699–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Peng, Q.; Tan, Z.; Xu, S.; Wang, Y.; Wu, A.; Xiao, W.; Wang, Q.; Xie, H.; Li, J.; et al. Targeting Aquaporin-3 Attenuates Skin Inflammation in Rosacea. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2023, 19, 5160–5173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hara-Chikuma, M.; Verkman, A.S. Aquaporin-3 Facilitates Epidermal Cell Migration and Proliferation during Wound Healing. J. Mol. Med. 2008, 86, 221–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, I.V.; Silva, A.G.; Pimpão, C.; Soveral, G. Skin Aquaporins as Druggable Targets: Promoting Health by Addressing the Disease. Biochimie 2021, 188, 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishida, Y.; Kuninaka, Y.; Furukawa, F.; Kimura, A.; Nosaka, M.; Fukami, M.; Yamamoto, H.; Kato, T.; Shimada, E.; Hata, S.; et al. Immunohistochemical Analysis on Aquaporin-1 and Aquaporin-3 in Skin Wounds from the Aspects of Wound Age Determination. Int. J. Leg. Med. 2018, 132, 237–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prangenberg, J.; Doberentz, E.; Witte, A.L.; Madea, B. Aquaporin 1 and 3 as Local Vitality Markers in Mechanical and Thermal Skin Injuries. Int. J. Leg. Med. 2021, 135, 1837–1842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimi, N.; Ahmadi, V. Aquaporin Channels in Skin Physiology and Aging Pathophysiology: Investigating Their Role in Skin Function and the Hallmarks of Aging. Biology 2024, 13, 862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, H.; Zhou, L.; Liu, F.; Long, J.; Yan, S.; Xie, Y.; Hu, X.; Li, J. Autophagy Induction Regulates Aquaporin 3-Mediated Skin Fibroblast Ageing*. Br. J. Dermatol. 2022, 186, 318–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaudhuri, R.K.; Bojanowski, K. Improvement of Hydration and Epidermal Barrier Function in Human Skin by a Novel Compound Isosorbide Dicaprylate. Int. J. Cosmet. Sci. 2017, 39, 518–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Cao, Y.; Huang, X.; Zhang, M.; Hu, J.F.; Li, L.; Xiong, L. Short-Term Skin Reactions and Changes in Stratum Corneum Following Different Ways of Facial Sheet Mask Usage. J. Tissue Viability 2024, 33, 831–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, C.J.; Chen, C.C.; Shih, H.S.; Chang, L.R.; Liu, C.H.; Liu, Y.T.; Lin, P.H.; Huang, W.S.; Jeng, S.F.; Feng, G.M. Effect of Intense Pulsed Light on the Expression of Aquaporin 3 in Rat Skin. Lasers Med. Sci. 2015, 30, 1959–1965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ikarashi, N.; Shiseki, M.; Yoshida, R.; Tabata, K.; Kimura, R.; Watanabe, T.; Kon, R.; Sakai, H.; Kamei, J. Cannabidiol Application Increases Cutaneous Aquaporin-3 and Exerts a Skin Moisturizing Effect. Pharmaceuticals 2021, 14, 879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schrader, A.; Siefken, W.; Kueper, T.; Breitenbach, U.; Gatermann, C.; Sperling, G.; Biernoth, T.; Scherner, C.; Stäb, F.; Wenck, H.; et al. Effects of Glyceryl Glucoside on AQP3 Expression, Barrier Function and Hydration of Human Skin. Ski. Pharmacol. Physiol. 2012, 25, 192–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khmaladze, I.; Butler, É.; Fabre, S.; Gillbro, J.M. Lactobacillus Reuteri DSM 17938—A Comparative Study on the Effect of Probiotics and Lysates on Human Skin. Exp. Dermatol. 2019, 28, 822–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, Y.H.; Kim, J.W.; Kim, N.; Kim, H.S.; Jang, J.H.; Bae, J.T.; Kim, W. Lactobacillus Brevis-Derived Exosomes Enhance Skin Barrier Integrity by Upregulating Key Barrier-Related Proteins. Clin. Cosmet. Investig. Dermatol. 2025, 18, 1151–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Carmen Velazquez Pereda, M.; de Campos Dieamant, G.; Eberlin, S.; Nogueira, C.; Colombi, D.; Di Stasi, L.C.; de Souza Queiroz, M.L. Effect of Green Coffea Arabica L. Seed Oil on Extracellular Matrix Components and Water-Channel Expression in in Vitro and Ex Vivo Human Skin Models. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2009, 8, 56–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhuri, R.K.; Bojanowski, K. Bakuchiol: A Retinol-like Functional Compound Revealed by Gene Expression Profiling and Clinically Proven to Have Anti-Aging Effects. Int. J. Cosmet. Sci. 2014, 36, 221–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikarashi, N.; Kon, R.; Nagoya, C.; Ishikura, A.; Sugiyama, Y.; Takahashi, J.; Sugiyama, K. Effect of Astaxanthin on the Expression and Activity of Aquaporin-3 in Skin in an in-Vitro Study. Life 2020, 10, 193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyoshi, T.; Keller, B.C.; Nakagawa, S.; Ashino, T.; Numazawa, S. PEG-23 Glyceryl Distearate, a Multifunctional Skin-Supporting Material, Upregulates the Expression of Factors Associated with Epidermal Barrier and Hydration. Int. J. Cosmet. Sci. 2025. Online ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, H.J.; Park, S.A.; Shin, E.; Kim, J.; Lee, G.S.; Lee, Y.J.; Park, S.M.; Lee, J.; Hyun, C.G. Poly-γ-Glutamic Acid from a Novel Bacillus Subtilis Strain: Strengthening the Skin Barrier and Improving Moisture Retention in Keratinocytes and a Reconstructed Skin Model. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caruso, F.; Yoo, N.H.; Lee, H.S.; Park, S.M.; Baek, Y.S.; Kim, M.J. Skin-Whitening, Antiwrinkle, and Moisturizing Effects of Astilboides Tabularis (Hemsl.) Engl. Root Extracts in Cell-Based Assays and Three-Dimensional Artificial Skin Models. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 5725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fluhr, J.W.; Darlenski, R.; Surber, C. Glycerol and the Skin: Holistic Approach to Its Origin and Functions. Br. J. Dermatol. 2008, 159, 23–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, S.C.; Tang, L.C.; Liu, C.H.; Liao, P.Y.; Lai, J.C.; Yang, J.H. Glycolic Acid Attenuates UVB-Induced Aquaporin-3, Matrix Metalloproteinase-9 Expression, and Collagen Degradation in Keratinocytes and Mouse Skin. Biochem. J. 2019, 476, 1387–1400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, C.H.; Min, S.Y.; Yu, H.W.; Kim, K.; Kim, S.; Lee, H.J.; Kim, J.H.; Park, Y.J. Effects of Apigenin on Rbl-2h3, Raw264.7, and Hacat Cells: Anti-Allergic, Anti-Inflammatory, and Skin-Protective Activities. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 4620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, R.; Chowdhury, S.; Choudhary, V.; Chen, X.; Bollag, W.B. Keratinocyte Aquaporin-3 Expression Induced by Histone Deacetylase Inhibitors Is Mediated in Part by Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptors (PPARs). Exp. Dermatol. 2020, 29, 380–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, N.H.; Kim, H.J.; Lee, A.Y. Aquaporin-3 Downregulation in Vitiligo Keratinocytes Increases Oxidative Stress of Melanocytes. Biomol. Ther. 2023, 31, 648–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Zhao, N.; Liang, L.; Li, M.; Nie, X.; Wang, Y.; Liu, Q.; Zhou, Q.; Shu, P. Evaluation of the Anti-Aging Potential of Acetyl Tripeptide-30 Citrulline in Cosmetics. Int. J. Pharm. 2024, 663, 124557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, W.; Luo, D.; Chen, D.; Zhang, S.; Chen, X.; Zhou, H.; Liu, Q.; Chen, S.; Liu, W. Systematic Study of Paeonol/Madecassoside Co-Delivery Nanoemulsion Transdermal Delivery System for Enhancing Barrier Repair and Anti-Inflammatory Efficacy. Molecules 2023, 28, 5275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Shen, X.; Liu, D.; Hong, M.; Lu, Y. The Protective Effects of β-Sitosterol and Vermicularin from Thamnolia Vermicularis (Sw.) Ach. Against Skin Aging in Vitro. Acad. Bras. Cienc. 2019, 91, e20181088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, H.; Zha, P.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, W.; Meng, H.; Di, T. Study on Moisturizing Effect of Dendrobium Officinale, Sparassis Crispa, and Their Compound Extracts. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2025, 24, e70189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buono, S.; Langellotti, A.L.; Martello, A.; Bimonte, M.; Tito, A.; Carola, A.; Apone, F.; Colucci, G.; Fogliano, V. Biological Activities of Dermatological Interest by the Water Extract of the Microalga Botryococcus Braunii. Arch. Dermatol. Res. 2012, 304, 755–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tito, A.; Bimonte, M.; Carola, A.; De Lucia, A.; Barbulova, A.; Tortora, A.; Colucci, G.; Apone, F. An Oil-Soluble Extract of Rubus Idaeus Cells Enhances Hydration and Water Homeostasis in Skin Cells. Int. J. Cosmet. Sci. 2015, 37, 588–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, M.; Sun, Y.; Zhu, L.; Li, L.; Zhao, Y. Study on the Skincare Effects of Red Rice Fermented by Aspergillus Oryzae In Vitro. Molecules 2024, 29, 2066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, X.; Tian, X.; Wang, M.; Li, Y.; Yang, S.; Kong, J. Protective Effect of Bifidobacterium Animalis CGMCC25262 on HaCaT Keratinocytes. Int. Microbiol. 2024, 27, 1417–1428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Huang, H.; Tao, K.; Guo, L.; Hu, X.; Chang, H. Novel Thermus Thermophilus and Bacillus Subtilis Mixed-Culture Ferment Extract Provides Potent Skin Benefits in Vitro and Protects Skin from Aging. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2024, 23, 4334–4342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, W.; Di, F.; Li, L.; Pu, C.; Wang, C.; Zhang, J. Anti-Photodamage Effect of Agaricus Blazei Murill Polysaccharide on UVB-Damaged HaCaT Cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 4676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Fu, H.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, D.; Zhao, D.; Zhang, J.; Li, M.; Wang, C. Reparative Effects of Dandelion Fermentation Broth on UVB-Induced Skin Inflammation. Clin. Cosmet. Investig. Dermatol. 2022, 15, 471–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.Y.; Pan, C.C.; Tseng, C.H.; Yen, F.L. Antioxidant, Anti-Inflammation and Antiaging Activities of Artocarpus Altilis Methanolic Extract on Urban Particulate Matter-Induced HaCaT Keratinocytes Damage. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 2304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; Lim, J.; Kim, S.; Jeon, M.; Baek, H.; Park, W.; Park, J.; Kim, S.; Kang, N.G.; Park, C.G.; et al. Anti-Inflammatory Artificial Extracellular Vesicles with Notable Inhibition of Particulate Matter-Induced Skin Inflammation and Barrier Function Impairment. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2023, 15, 59199–59208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khmaladze, I.; Österlund, C.; Smiljanic, S.; Hrapovic, N.; Lafon-Kolb, V.; Amini, N.; Xi, L.; Fabre, S. A Novel Multifunctional Skin Care Formulation with a Unique Blend of Antipollution, Brightening and Antiaging Active Complexes. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2020, 19, 1415–1425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.; Cho, H.; Kim, M.; Kim, B.; Jang, Y.P.; Park, J. Evaluating the Dermatological Benefits of Snowberry (Symphoricarpos albus): A Comparative Analysis of Extracts and Fermented Products from Different Plant Parts. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 9660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Someya, T.; Sano, K.; Hara, K.; Sagane, Y.; Watanabe, T.; Wijesekara, R.G.S. Fibroblast and Keratinocyte Gene Expression Following Exposure to Extracts of Neem Plant (Azadirachta indica). Data Brief. 2018, 16, 982–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Someya, T.; Sano, K.; Hara, K.; Sagane, Y.; Watanabe, T.; Wijesekara, R.G.S. Fibroblast and Keratinocyte Gene Expression Following Exposure to the Extracts of Holy Basil Plant (Ocimum tenuiflorum), Malabar Nut Plant (Justicia adhatoda), and Mblic Myrobalan Plant (Phyllanthus emblica). Data Brief. 2018, 17, 24–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, K.; Guo, C.; Zhu, J.; Wei, Y.; Wu, M.; Huang, X.; Zhang, M.; Li, J.; Wang, X.; Wang, Y.; et al. The Whitening, Moisturizing, Anti-Aging Activities, and Skincare Evaluation of Selenium-Enriched Mung Bean Fermentation Broth. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 837168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, E.M.; Oliveira, A.S.; Silva, S.; Ribeiro, A.B.; Pereira, C.F.; Ferreira, C.; Casanova, F.; Pereira, J.O.; Freixo, R.; Pintado, M.E.; et al. Spent Yeast Waste Streams as a Sustainable Source of Bioactive Peptides for Skin Applications. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 2253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dusabimana, T.; Karekezi, J.; Nugroho, T.A.; Ndahigwa, E.N.; Choi, Y.J.; Kim, H.; Kim, H.J.; Park, S.W. Oyster Hydrolysate Ameliorates UVB-Induced Skin Dehydration and Barrier Dysfunction. Life Sci. 2024, 358, 123149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadora, D.; Burney, W.; Chaudhuri, R.K.; Galati, A.; Min, M.; Fong, S.; Lo, K.; Chambers, C.J.; Sivamani, R.K. Prospective Randomized Double-Blind Vehicle-Controlled Study of Topical Coconut and Sunflower Seed Oil-Derived Isosorbide Diesters on Atopic Dermatitis. Dermatitis 2024, 35, S62–S69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verkman, A.S. Aquaporins at a Glance. J. Cell Sci. 2011, 124, 2107–2112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hara, M.; Ma, T.; Verkman, A.S. Selectively Reduced Glycerol in Skin of Aquaporin-3-Deficient Mice May Account for Impaired Skin Hydration, Elasticity, and Barrier Recovery. J. Biol. Chem. 2002, 277, 46616–46621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hara-Chikuma, M.; Verkman, A.S. Roles of Aquaporin-3 in the Epidermis. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2008, 128, 2145–2151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, J.; Li, Y.; Hu, X.; Hua, W.; Xu, H.; Li, L.; Xu, F. Enhancing Tranexamic Acid Penetration through AQP-3 Protein Triggering via ZIF-8 Encapsulation for Melasma and Rosacea Therapy. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2024, 13, 2304189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Verkman, A.S.; Hu, J.; Verkman, A.S. Increased Migration and Metastatic Potential of Tumor Cells Expressing Aquaporin Water Channels. FASEB J. 2006, 20, 1892–1894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hara-Chikuma, M.; Verkman, A.S. Prevention of Skin Tumorigenesis and Impairment of Epidermal Cell Proliferation by Targeted Aquaporin-3 Gene Disruption. Mol. Cell Biol. 2008, 28, 326–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osorio, G.; Zulueta-Dorado, T.; González-Rodríguez, P.; Bernabéu-Wittel, J.; Conejo-Mir, J.; Ramírez-Lorca, R.; Echevarría, M. Expression Pattern of Aquaporin 1 and Aquaporin 3 in Melanocytic and Nonmelanocytic Skin Tumors. Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 2019, 152, 446–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galán-Cobo, A.; Ramírez-Lorca, R.; Serna, A.; Echevarría, M. Overexpression of AQP3 Modifies the Cell Cycle and the Proliferation Rate of Mammalian Cells in Culture. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0137692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadariswantiningsih, I.N.; Kadarman, J.T. Inhibiting Aquaporin-3 to Prevent Melanoma Progression: The Potential of Organogold. J. Physiol. 2024, 602, 3007–3009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prata, C.; Hrelia, S.; Fiorentini, D. Peroxiporins in Cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 1371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pizzino, G.; Irrera, N.; Cucinotta, M.; Pallio, G.; Mannino, F.; Arcoraci, V.; Squadrito, F.; Altavilla, D.; Bitto, A. Oxidative Stress: Harms and Benefits for Human Health. Oxid. Med. Cell Longev. 2017, 2017, 8416763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Da Silva, I.V.; Pimpão, C.; Paccetti-Alves, I.; Thomas, S.R.; Barateiro, A.; Casini, A.; Soveral, G.; Casini, A. Blockage of Aquaporin-3 Peroxiporin Activity by Organogold Compounds Affects Melanoma Cell Adhesion, Proliferation and Migration. J. Physiol. 2024, 602, 3111–3129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Voss, K.E.; Bollag, R.J.; Fussell, N.; By, C.; Sheehan, D.J.; Bollag, W.B. Abnormal Aquaporin-3 Protein Expression in Hyperproliferative Skin Disorders. Arch. Dermatol. Res. 2011, 303, 591–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Seleit, I.; Bakry, O.A.; Al Sharaky, D.; Ragheb, E. Evaluation of Aquaporin-3 Role in Nonmelanoma Skin Cancer: An Immunohistochemical Study. Ultrastruct. Pathol. 2015, 39, 306–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verkman, A.S. A Cautionary Note on Cosmetics Containing Ingredients That Increase Aquaporin-3 Expression. Exp. Dermatol. 2008, 17, 871–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).