Medicinal Plants for Dermatological Diseases: Ethnopharmacological Significance of Botanicals from West Africa in Skin Care

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methodology

- It is published in English or translated to English.

- At least one plant is listed for the treatment of skin diseases.

- It studied the bioactivity of at least one of the plants in the list of plants documented.

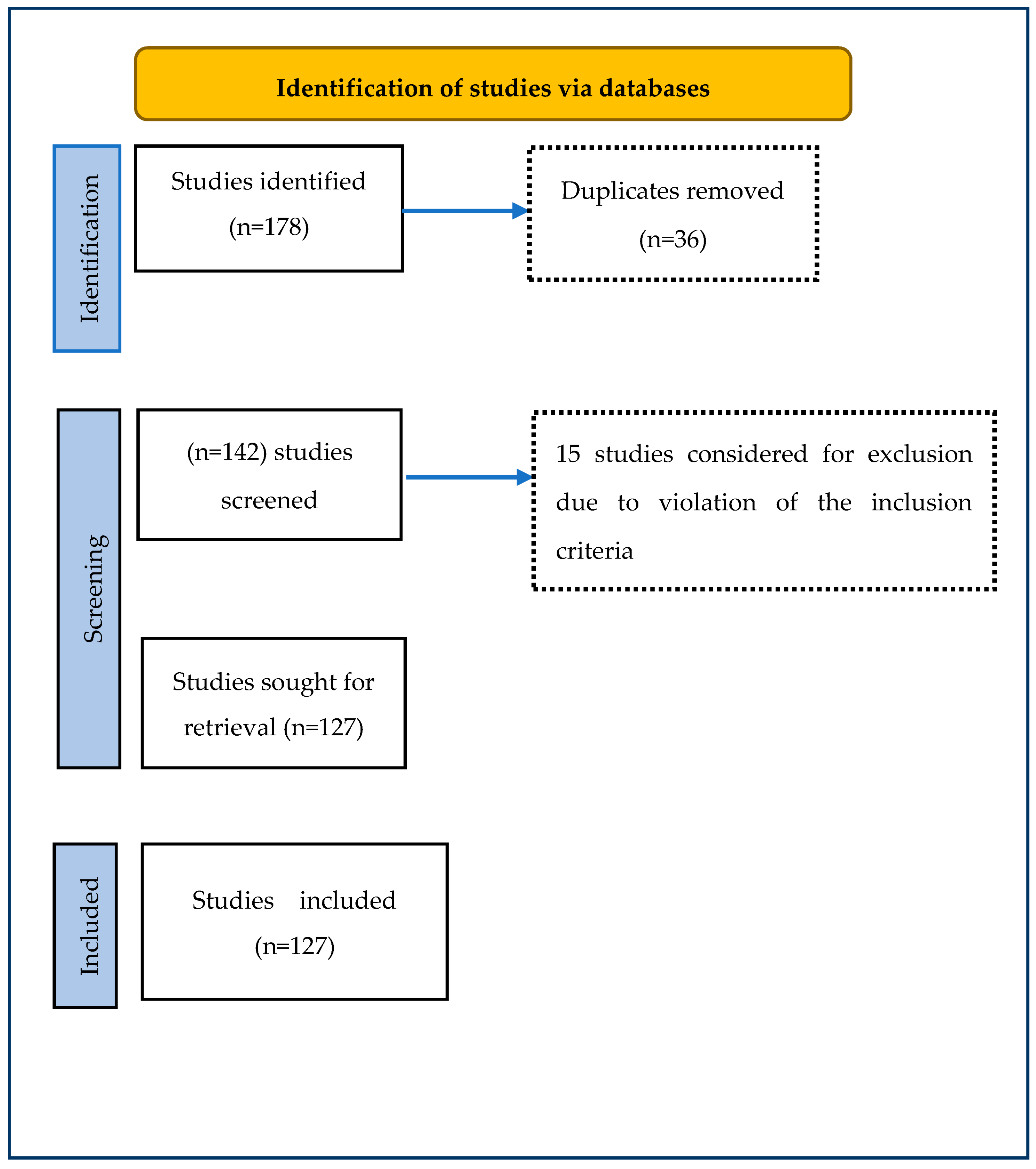

- If the ethnopharmacological study is carried out outside West Africa but examines the bioactivity of any documented plants used to treat skin diseases in the region. Figure 1 shows the PRISMA flowchart for the inclusion and exclusion procedure.

3. Results and Discussion

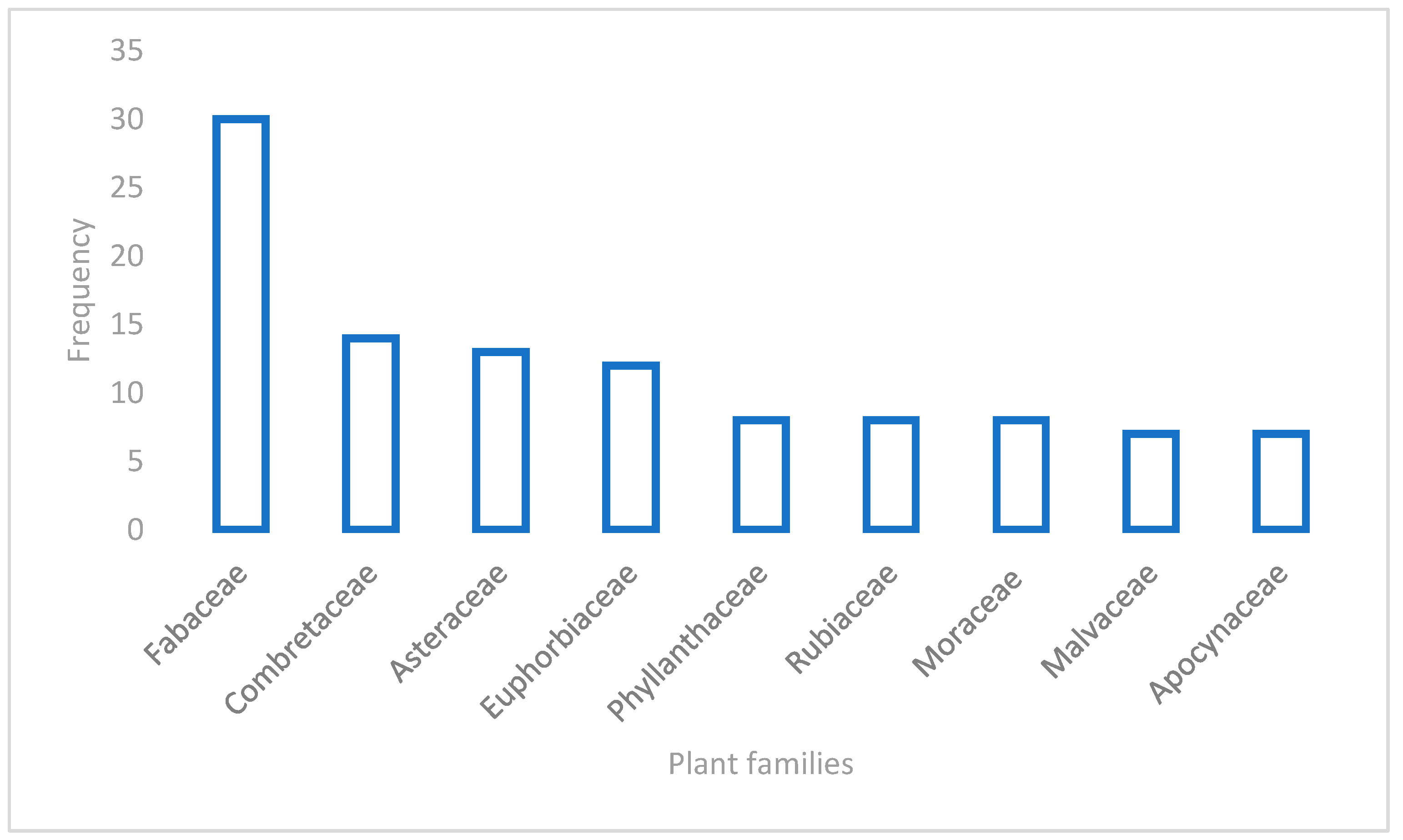

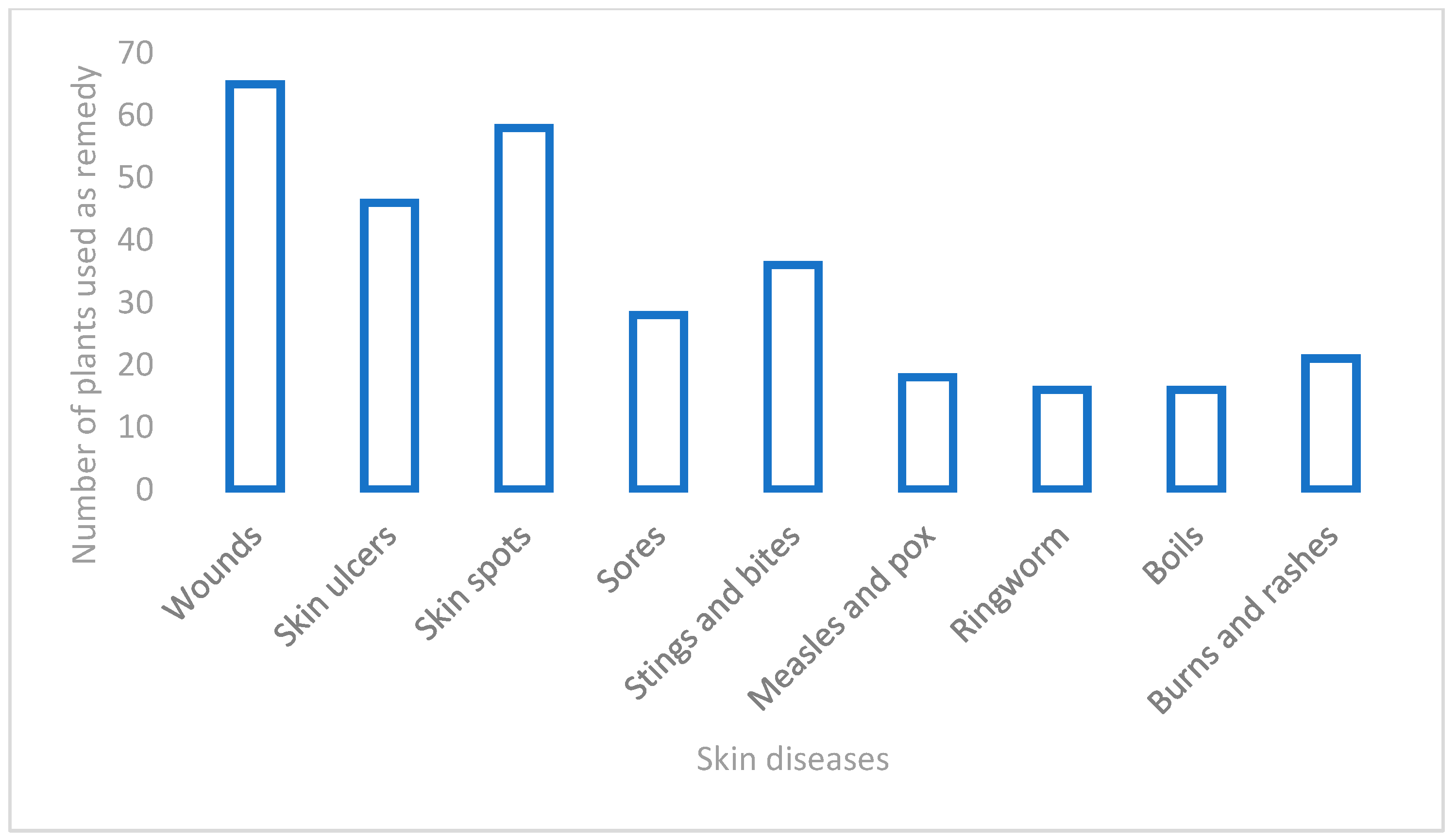

3.1. Diversity of the Medicinal Plants Used for Skin Diseases in West Africa

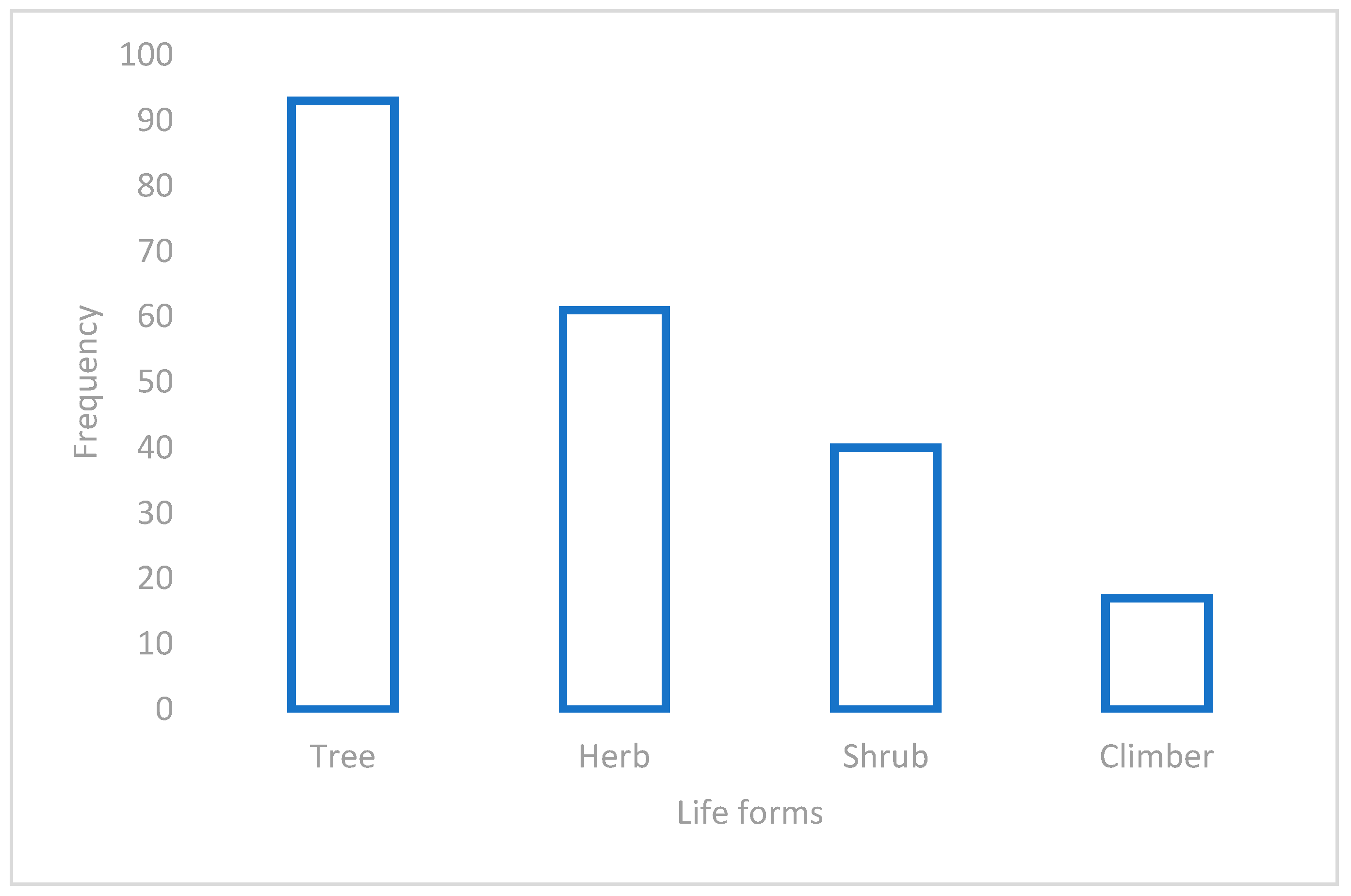

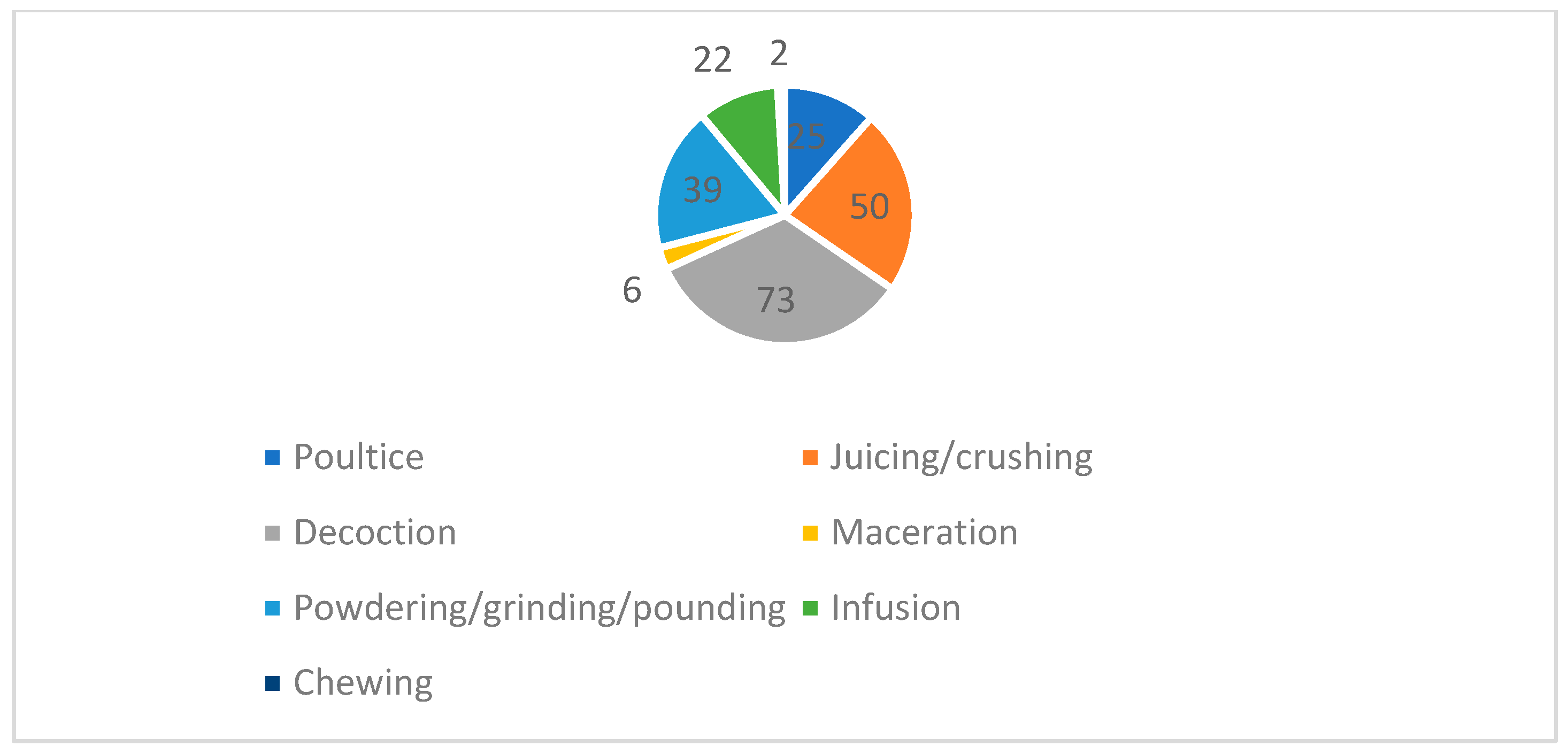

3.2. Life Forms, Plant Parts Used, Mode of Preparation, and Conservation Statuses of the Plants

3.3. Biological Activities of the Recorded Plants

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rosamah, E.; Haqiqi, M.T.; Putri, A.S.; Kuspradini, H.; Kusuma, I.W.; Amirta, R.; Arung, E.T. The potential of Macaranga plants as skincare cosmetic ingredients: A review. J. Appl. Pharm. Sci. 2023, 13, 001–012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGrath, J.A.; Eady, R.A.J.; Pope, F.M. Anatomy and organization of human skin. Rook’s Textb. Dermatol. 2004, 1, 2–3. [Google Scholar]

- Paulino, L.C.; Tseng, C.H.; Strober, B.E.; Blaser, M.J. Molecular analysis of fungal microbiota in samples from healthy human skin and psoriatic lesions. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2006, 44, 2933–2941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Byrd, A.L.; Belkaid, Y.; Segre, J.A. The human skin microbiome. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2018, 16, 143–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belkaid, Y.; Segre, J.A. Dialogue between skin microbiota and immunity. Science 2014, 346, 954–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hay, R.J.; Johns, N.E.; Williams, H.C.; Bolliger, I.W.; Dellavalle, R.P.; Margolis, D.J.; Naghavi, M. The global burden of skin disease in 2010: An analysis of the prevalence and impact of skin conditions. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2014, 134, 1527–1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Basra, M.K.; Shahrukh, M. Burden of skin diseases. Expert. Rev. Pharmacoecon. Outcomes Res. 2009, 9, 271–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tabassum, N.; Hamdani, M. Plants used to treat skin diseases. Pharmacogn. Rev. 2014, 8, 52–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukaila, Y.O.; Oladipo, O.T.; Ogunlowo, I.; Ajao, A.A.N.; Sabiu, S. Which plants for what ailments: A quantitative analysis of medicinal ethnobotany of Ile-Ife, Osun State, Southwestern Nigeria. Evid.-Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2021, 2021, 5711547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mabona, U.; Van Vuuren, S.F. Southern African medicinal plants used to treat skin diseases. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2013, 87, 175–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alamgeer, S.A.; Asif, H.; Younis, W.; Riaz, H.; Bukhari, I.A.; Assiri, A.M. Indigenous medicinal plants of Pakistan used to treat skin diseases: A review. Chin. Med. 2018, 13, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsioutsiou, E.E.; Amountzias, V.; Vontzalidou, A.; Dina, E.; Stevanović, Z.D.; Cheilari, A.; Aligiannis, N. Medicinal plants used traditionally for skin related problems in the south balkan and east mediterranean region—A review. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 936047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kankara, S.S.; Ibrahim, M.H.; Mustafa, M.; Go, R. Ethnobotanical survey of medicinal plants used for traditional maternal healthcare in Katsina state, Nigeria. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2015, 97, 165–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zizka, A.; Thiombiano, A.; Dressler, S.; Nacoulma, B.M.; Ouédraogo, A.; Ouédraogo, I.; Ouédraogo, O.; Zizka, G.; Hahn, K.; Schmidt, M. Traditional plant use in Burkina Faso (West Africa): A national-scale analysis with focus on traditional medicine. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2015, 11, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ajibesin, K.K. Ethnobotanical survey of plants used for skin diseases and related ailments in Akwa Ibom State, Nigeria. Ethnobot. Res. Appl. 2012, 10, 463–522. [Google Scholar]

- Codo Toafode, N.M.; Oppong Bekoe, E.; Vissiennon, Z.; Ahyi, V.; Vissiennon, C.; Fester, K. Ethnomedicinal information on plants used for the treatment of bone fractures, wounds, and sprains in the northern region of the Republic of Benin. Evid.-Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2022, 2022, 8619330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simbo, D.J. An ethnobotanical survey of medicinal plants in Babungo, Northwest Region, Cameroon. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2010, 6, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Udegbunam, S.O.; Udegbunam, R.I.; Nnaji, T.O.; Anyanwu, M.U.; Kene, R.O.C.; Anika, S.M. Antimicrobial and antioxidant effect of methanolic Crinum jagus bulb extract in wound healing. J. Intercult. Ethnopharmacol. 2015, 4, 239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, G.M.S.; Gobbo, J. Antimicrobial effect of Anacardium occidentale extract and cosmetic formulation development. Braz. Arch. Biol. Technol. 2012, 55, 843–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Minero, F.J.; Bravo-Díaz, L.; Moreno-Toral, E. Pharmacy and fragrances: Traditional and current use of plants and their extracts. Cosmetics 2023, 10, 157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maroyi, A. Medicinal uses of the Fabaceae family in Zimbabwe: A Review. Plants 2023, 12, 1255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajao, A.A.; Sibiya, N.P.; Moteetee, A.N. Sexual prowess from nature: A systematic review 315 of medicinal plants used as aphrodisiacs and sexual dysfunction in sub-Saharan Africa. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2019, 122, 342–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, C.B.; Verotta, L. Chemistry and biological properties of the African Combretaceae. In Chemistry, Biological and Pharmacological Properties of African Medicinal Plants; Hostettman, K., Chinyanganga, F., Maillard, M., Wolfender, J.-L., Eds.; University of Zimbabwe Publications: Harare, Zimbabwe, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Eloff, J.N.; Katerere, D.R.; McGaw, L.J. The biological activity and chemistry of the southern African Combretaceae. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2008, 119, 686–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ccana-Ccapatinta, G.V.; Monge, M.; Ferreira, P.L.; Da Costa, F.B. Chemistry and medicinal uses of the subfamily Barnadesioideae (Asteraceae). Phytochem. Rev. 2018, 17, 471–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ntie-Kang, F.; Lifongo, L.L.; Mbaze, L.M.A.; Ekwelle, N.; Owono Owono, L.C.; Megnassan, E.; Efange, S.M. Cameroonian medicinal plants: A bioactivity versus ethnobotanical survey and chemotaxonomic classification. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2013, 13, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dalziel, J.M. The Useful Plants of West Tropical Afica. In Being an Appendix to “the Flora of West Tropical Africa”; Crown Agents for the Colonies: London, UK, 1937. [Google Scholar]

- Bouquet, A.; Debray, M. Plantes médicinales de la Côte d’Ivoire. Trav. Doc. L’office Rech. Sci. Tech. Outre-Mer. 1974, 32, 5–229. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, W.H.; Elvin-Lewis, M.P. Medical Botany: Plants Affecting Human Health; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Kerharo, J.; Adam, J.G. Deuxième inventaire des plantes médicinales et toxiques de la Casamance (Sénégal). Ann. Pharm. Françaises 1963, 21, 773–792. [Google Scholar]

- Kerharo, J.; Adam, J.G. La Pharmacopée Sénégalaise Traditionnelle: Plantes Medicinales et Toxiques; Vigot: Paris, France, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Irvine, F.R. Plants of the Gold Coast; Oxford University Press: London, UK, 1930. [Google Scholar]

- Chevalier, A.; Laffitte, M. Une enquête sur les plantes médicinales de l’Afrique occidentale. Rev. Bot. Appl. Agric. Trop. 1937, 27, 165–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfa, T.; Anani, K.; Adjrah, Y.; Batawila, K.; Ameyapoh, Y. Ethnobotanical survey of medicinal plants used against fungal infections in prefecture of sotouboua central region, Togo. Eur. Sci. J. 2018, 14, 342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burkill, H.M. The Useful Plants of West Tropical Africa, 2nd ed.; Family A–D; Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew: London, UK, 1985; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Betti, J.L. An ethnobotanical study of medicinal plants among the Baka pygmies in the Dja biosphere reserve, Cameroon. Afr. Stud. Monogr. 2004, 25, 1–27. [Google Scholar]

- Chopra, R.N.; Nayar, S.L.; Chopra, I.C. Glossary of Indian Medicinal Plants; CSIR: New Delhi, India, 1956. [Google Scholar]

- Pobéguin, H. Plantes Médicinales de la Guinée; Challamel: Paris, France, 1912. [Google Scholar]

- Kerharo, J.; Adam, J.G. Premier inventaire des plantes médicinales et toxiques de la Casamance (Senegal). Ann. Pharm. Françaises 1962, 20, 76–84. [Google Scholar]

- Agbovie, T.; Amponsah, K.; Crentsil, O.R.; Dennis, F.; Odamtten, G.T.; Ofusohene-Djan, W. Conservation and sustainable use of medicinal plants in Ghana. Ethnobot. Surv. 2002, 15, 32–37. [Google Scholar]

- Kerharo, J.; Bouquet, A. Indigenous Conceptions of Leprosy and its Treatment in the Ivory Coast and Haute-Volta. Bull. Société Pathol. Exot. 1950, 43, 56–65. [Google Scholar]

- Bhat, R.B.; Etejere, E.O.; Oladipo, V.T. Ethnobotanical studies from central Nigeria. Econ. Bot. 1990, 44, 382–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dossou-Yovo, H.O.; Vodouhè, F.G.; Kaplan, A.; Sinsin, B. Application of ethnobotanical indices in the utilization of five medicinal herbaceous plant species in Benin, West Africa. Diversity 2022, 14, 612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouquet, A. Féticheurs et médicines traditionalles du Congo (Brazzaville). Mémoires Off. Rech. Sci. Technol. Outre-Mer. 1969, 36, 4–304. [Google Scholar]

- Chifundera, K. Contribution to the inventory of medicinal plants from the Bushi area, South Kivu Province, Democratic Republic of Congo. Fitoterapia 2001, 72, 351–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyen, L.P.A. Symphonia globulifera L.f. In PROTA (Plant Resources of Tropical Africa/Ressources Végétales de l’Afrique Tropicale); Louppe, D., Oteng-Amoako, A.A., Brink, M., Eds.; Wageningen University: Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Fromentin, Y.; Cottet, K.; Kritsanida, M.; Michel, S.; Gaboriaud-Kolar, N.; Lallemand, M.C. Symphonia globulifera, a widespread source of complex metabolites with potent biological activities. Planta Medica 2015, 81, 95–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madge, C. Therapeutic landscapes of the Jola, The Gambia, West Africa. Health Place 1998, 4, 293–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aubréville, A. Flore Forestière Soudano-Guinéene: A.O.F., Cameroun, A.E.F; Société d’Éditions Géographiques Maritimes et Coloniales: Paris, France, 1950. [Google Scholar]

- Boadu, A.A.; Asase, A. Documentation of herbal medicines used for the treatment and management of human diseases by some communities in southern Ghana. Evid.-Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2017, 2017, 3043061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabran, F.A.; Maciuk, A.; Okpekon, T.A.; Leblanc, K.; Seon-Meniel, B.; Bories, C.; Champy, P.; Djakouré, L.A.; Figadère, B. Phytochemical and biological analysis of Mallotus oppositifolius (Euphorbiaceae). Planta Med. 2012, 78, 1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellena, R.; Quave, C.L.; Pieroni, A. Comparative medical ethnobotany of the Senegalese community living in Turin (Northwestern Italy) and in Adeane (Southern Senegal). Evid.-Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2012, 2012, 604363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuma, D.N.; Boye, A.; Kwakye-Nuako, G.; Boakye, Y.D.; Addo, J.K.; Asiamah, E.A.; Atsu Barku, V.Y. Wound healing properties and antimicrobial effects of Parkia clappertoniana keay fruit husk extract in a rat excisional wound model. BioMed Res. Intern. 2022, 2022, 9709365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Komakech, R. Herbs & Plants. Psorospermum febrifugum Spach. A Medicinal Plant for Skin Diseases. Available online: southworld.net/herbs-plants-psorospermum-febrifugum-spach-a-medicinal-plant-for-skin-diseases (accessed on 1 April 2023).

- Tropical lants Database, Ken Fern. Available online: tropical.theferns.info/viewtropical.php?id=Psorospermum+febrifugum (accessed on 1 April 2023).

- Rukangira, E. The African herbal industry: Constraints and challenges. Proceedings of the Natural Products and Cosmeceuticals, August 2001. Erbor. Domani 2001, 1, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Adediwura, F.J.; Ajibesin, K.K.; Odeyemi, T.; Ogundokun, G. Ethnobotanical studies of folklore phytocosmetics of South West Nigeria. Pharm. Biol. 2015, 53, 313–318. [Google Scholar]

- DeFilipps, R.A.; Maina, S.L.; Crepin, J. Medicinal Plants of the Guianas (Guyana, Surinam, French Guiana). In Medicinal Plants of the Guianas (Guyana Surinam Fr. Guiana); Department of Botany, National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution: Washington, DC, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Kitambala, M.M. Uapaca guineensis Müll.Arg. In PROTA (Plant Resources of Tropical Africa/Ressources Végétales de l’Afrique Tropicale); Schmelzer, G.H., Gurib-Fakim, A., Eds.; Wageningen University: Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Kokwaro, J.O. Medicinal Plants of East Africa; University of Nairobi Press: Nairobi, Kenya, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Haq, I. Safety of medicinal plants. Pak. J. Med. Res. 2004, 43, 203–210. [Google Scholar]

- Mlilo, S.; Sibanda, S. An ethnobotanical survey of the medicinal plants used in the treatment of cancer in some parts of Matebeleland, Zimbabwe. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2022, 146, 401–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makgobole, M.U.; Onwubu, S.C.; Nxumal, C.T.; Mpofana, N.; Ajao, A.A.N. In search of oral cosmetics from nature: A review of medicinal plants for dental care in West Africa. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2023, 162, 644–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petran, M.; Dragos, D.; Gilca, M. Historical ethnobotanical review of medicinal plants used to treat children diseases in Romania (1860s–1970s). J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2020, 16, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howes, M.J.R.; Quave, C.L.; Collemare, J.; Tatsis, E.C.; Twilley, D.; Lulekal, E.; Nic-Lughadha, E. Molecules from nature: Reconciling biodiversity conservation and global healthcare imperatives for sustainable use of medicinal plants and fungi. Plants People Planet 2020, 2, 463–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iyekowa, O.; Oviawe, A.P.; Ndiribe, J.O. Antimicrobial activities of Acalypha wilkesiana (Red Acalypha) extracts in some selected skin pathogens. Zimb. J. Sci. Technol. 2016, 11, 48–57. [Google Scholar]

- Ram, A.J.; Bhakshu, L.M.; Raju, R.V. In vitro antimicrobial activity of certain medicinal plants from Eastern Ghats, India, used for skin diseases. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2004, 90, 353–357. [Google Scholar]

- Okoli, C.O.; Akah, P.A.; Onuoha, N.J.; Okoye, T.C.; Nwoye, A.C.; Nworu, C.S. Acanthus montanus: An experimental evaluation of the antimicrobial, anti-inflammatory and immunological properties of a traditional remedy for furuncles. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2008, 8, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ndam, P.; Onyemelukwe, N.; Nwakile, C.D.; Ogboi, S.J.; Maduakor, U. Antifungal properties of methanolic extracts of some medical plants in Enugu, south east Nigeria. Afr. J. Cli. Experiment. Microbiol. 2018, 19, 141–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.; Toppo, K.I.; Karkun, D.; Kumar, A.; Mishra, N.; Dadsena, R.; Thakur, T. Antimicrobial activity of Achyranthes aspera against some human pathogenic bacteria and fungi. Intern. J. Pharmacol. Biol. Sci. 2013, 7, 43–54. [Google Scholar]

- Abhaykumar, K. Phytochemical studies on Achyranthes aspera. World Sci. News 2018, 100, 16–34. [Google Scholar]

- Olatunji, B.P.; Idris, O.O.; Ogunmefun, O.T.; Abuka, D.U. Assessment of Andrographis paniculata and Aframomum melegueta on bacteria isolated from wounds. J. Chem. Pharm. Sci. 2019, 12, 2349–8552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gbadamosi, I.T.; Oyedele, T.O. The efficacy of seven ethnobotanicals in the treatment of skin infections in Ibadan, Nigeria. Afr. J. Biotechnol. 2012, 11, 3928–3934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vigbedor, B.Y.; Osei-Owusu, J.; Kwakye, R.; Neglo, D. Bioassay-guided fractionation, ESI-MS scan, phytochemical screening, and antiplasmodial activity of Afzelia africana. Biochem. Res. Int. 2022, 2022, 6895560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kouame, B.K.F.P.; Toure, D.; Kablan, L.; Bedi, G.; Tea, I.; Robins, R.; Tonzibo, F. Chemical constituents and antibacterial activity of essential oils from flowers and stems of Ageratum c onyzoides from Ivory Coast. Rec. Nat. Prod. 2018, 12, 160–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agyare, C.; Ansah, A.O.; Ossei, P.P.S.; Apenteng, J.A.; Boakye, Y.D. Wound healing and anti-infective properties of Myrianthus arboreus and Alchornea cordifolia. Med. Chem. 2014, 4, 533–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajibesin, K.K.; Rene, N.; Bala, D.N.; Essiett, U.A. Antimicrobial activities of the extracts and fractions of Allanblackia floribunda. Biotechnol. 2008, 7, 129–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Ayoola, G.A.; Ipav, S.S.; Sofidiya, M.O.; Adepoju-Bello, A.A.; Coker, H.A.; Odugbemi, T.O. Phytochemical screening and free radical scavenging activities of the fruits and leaves of Allanblackia floribunda Oliv (Guttiferae). Intern. J. Health Res. 2008, 1, 87–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samuel, J.K.; Andrews, B.; Jebashree, H.S. In vitro evaluation of the antifungal activity of Allium sativum bulb extract against Trichophyton rubrum, a human skin pathogen. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2000, 16, 617–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusuf, A.; Fagbuaro, S.S.; Fajemilehin, S.O.K. Chemical composition, phytochemical and mineral profile of garlic (Allium sativum). J. Biosci. Biotechnol. Discov. 2018, 3, 105–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bashir, A.; Saeed, B.; Mujahid, T.Y.; Jehan, N. Comparative study of antimicrobial activities of Aloe vera extracts and antibiotics against isolates from skin infections. Afr. J. Biotechnol. 2011, 10, 3835–3840. [Google Scholar]

- Arunkumar, S.; Muthuselvam, M. Analysis of phytochemical constituents and antimicrobial activities of Aloe vera L. against clinical pathogens. World J. Agric. Sci. 2009, 5, 572–576. [Google Scholar]

- Fetse, J.P.; Kyekyeku, J.O.; Dueve, E.; Mensah, K.B. Wound healing activity of total alkaloidal extract of the root bark of Alstonia boonei (Apocynacea). Br. J. Pharm. Res. 2014, 4, 26–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pamila, U.A.; Karpagam, S. Antimicrobial activity of Alternanthera bettzickiana (regel) g. Nicholson and its phytochemical contents. Intern. J. Pharm. Sci. Res. 2017, 8, 2594–2599. [Google Scholar]

- Maiyo, Z.C. Chemical Compositions and Antimicrobial Activity of Amaranthus hybridus, Amaranthus caudatus, Amaranthus spinosus and Corriandrum sativum. Ph.D. Dissertation, Egerton University, Egerton, Kenya, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Silva, J.G.; Souza, I.A.; Higino, J.S.; Siqueira-Junior, J.P.; Pereira, J.V.; Pereira, M.S.V. Atividade antimicrobiana do extrato de Anacardium occidentale Linn. em amostras multiresistentes de Staphylococcus aureus. Rev. Bras. Farm. 2007, 17, 572–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyetayo, V.O. Comparative Studies of the Phytochemical and Antimicrobial Properties of the Leaf, Stem and Tuber of Anchomanes difformis. J. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2007, 2, 407–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Nyong, E.E.; Odeniyi, M.A.; Moody, J.O. In vitro and in vivo antimicrobial evaluation of alkaloidal extracts of Enantia chlorantha stem bark and their formulated ointments. Acta Pharma 2015, 72, 14–52. [Google Scholar]

- Odoh, U.; Okwor, I.; Ezejiofor, M. Phytochemical, trypanocidal and antimicrobial studies of Enantia chlorantha (Annonaceae) root. J. Pharm. Allied Sci. 2011, 7, 4. [Google Scholar]

- Mann, A.; Yahaya, Y.; Banso, A.; John, F. Phytochemical and antimicrobial activity of Terminalia avicennioides extracts against some bacteria pathogens associated with patients suffering from complicated respiratory tract diseases. J. Med. Plants Res. 2008, 2, 9–97. [Google Scholar]

- Tukur, A.; Musa, N.M.; Bello, H.A.; Sani, N.A. Determination of the phytochemical constituents and antifungal properties of Annona senegalensis leaves (African custard apple). ChemSearch J. 2020, 11, 16–24. [Google Scholar]

- Chah, K.F.; Eze, C.A.; Emuelosi, C.E.; Esimone, C.O. Antibacterial and wound healing properties of methanolic extracts of some Nigerian medicinal plants. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2006, 104, 164–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Obioma, A.; Chikanka, A.T.; Dumo, I. Antimicrobial activity of leave extracts of Bryophyllum pinnatum and Aspilia africana on pathogenic wound isolates recovered from patients admitted in University of Port Harcourt Teaching Hospital, Nigeria. Ann. Clin. Lab. Res. 2017, 5, 185–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, E.C.; Eseyin, O.A.; Udobre, A.E.; Ike, P. Antibacterial Effect of Methanolic Extract of the Root of Aspilia africana. Niger. J. Pharm. Appl. Sci. Res. 2011, 1, 44–50. [Google Scholar]

- Pandey, G.; Verma, K.K.; Singh, M. Evaluation of phytochemical, antibacterial and free radical scavenging properties of Azadirachta indica (neem) leaves. Int. J. Pharm. Pharm. Sci. 2014, 6, 444–447. [Google Scholar]

- Agyare, C.; Oguejiofor, S.; Adu-Amoah, L.; Boakye, Y.D. Anti-inflammatory and anti-infective properties of ethanol leaf and root extracts of Baphia nitida. Br. Microbiol. Res. J. 2016, 11, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owoyemi, O.O.; Oladunmoye, M.K. Phytochemical screening and antibacterial activities of Bidens pilosa L. and Tridax procumbens L. on skin pathogens. Intern. J. Mod. Biol. Med. 2017, 8, 24–46. [Google Scholar]

- Tamokou, J.D.D.; Kuiate, J.R.; Tene, M.; Nwemeguela, T.J.K.; Tane, P. The antimicrobial activities of extract and compounds isolated from Brillantaisia lamium. Iran. J. Med. Sci. 2011, 36, 24. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Goyal, S.; Kumar, S.; Rawat, P.; Dhaliwal, N. Antifungal activity of Calotropis procera towards dermatoplaytes. Intern. J. Adv. Pharm. Biol. Chem. 2013, 2, 2277–4688. [Google Scholar]

- Naser, E.H.; Kashmer, A.M.; Abed, S.A. Antibacterial activity and phytochemical investigation of leaves of Calotropis procera plant in Iraq by GC-MS. IJPSR 2019, 10, 1988–1994. [Google Scholar]

- Udoumoh, A.F.; Eze, C.A.; Chah, K.F.; Etuk, E.U. Antibacterial and surgical wound healing properties of ethanolic leaf extracts of Swietenia mahogoni and Carapa procera. Asian J. Trad. Med. 2011, 6, 272–277. [Google Scholar]

- Dwivedi, M.K.; Sonter, S.; Mishra, S.; Patel, D.K.; Singh, P.K. Antioxidant, antibacterial activity, and phytochemical characterization of Carica papaya flowers. Beni-Suef Univ. J. Basic Appl. Sci. 2020, 9, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alain, K.Y.; Morand, A.J.; Andreea, B.D.; Théophile, O.; Pascal, A.D.C.; Alain, A.G.; Dominique, S.C.K. Phytochemical analysis, antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activities of Chassalia kolly leaves extract, a plant used in Benin to treat skin illness. GSC Biol. Pharm. Sci. 2021, 15, 063–072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thophon, S.H.S.; Waranusantigul, P.; Kangwanrangsan, N.; Krajangsang, S. Antimicrobial activity of Chromolaena odorata extracts against bacterial human skin infections. Mod. Appl. Sci. 2016, 10, 159–171. [Google Scholar]

- Ngozi, I.M.; Jude, I.C.; Catherine, I.C. Chemical profile of Chromolaena odorata L. (King and Robinson) leaves. Pak. J. Nutr. 2009, 8, 521–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najafi, S.; Sanadgol, N.; Nejad, B.S.; Beiragi, M.A.; Sanadgol, E. Phytochemical screening and antibacterial activity of Citrullus colocynthis (Linn.) Schrad against Staphylococcus Aureus. J. Med. Plants Res. 2010, 4, 2321–2325. [Google Scholar]

- Hameed, B.; Ali, Q.; Hafeez, M.M.; Malik, A. Antibacterial and antifungal activity of fruit, seed and root extracts of Citrullus colocynthis plant. Biol. Clin. Sci. Res. J. 2020, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gbedema, S.Y.; Emelia, K.; Francis, A.; Kofi, A.; Eric, W. Wound healing properties and kill kinetics of Clerodendron splendens G. Don, a Ghanaian wound healing plant. Pharmacogn. Res. 2010, 2, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oscar, N.D.Y.; Joel, T.N.S.; Ange, A.A.N.G.; Desire, S.; Brice, S.N.F.; Barthelemy, N. Chemical constituents of Clerodendrum splendens (Lamiaceae) and their antioxidant activities. J. Dis. Med. Plants 2018, 4, 120–127. [Google Scholar]

- Chakraborty, P.; Deb, P.; Chakraborty, S.; Chatterjee, B.; Abraham, J. Cytotoxicity and antimicrobial activity of Colocasia esculenta. J. Chem. Pharm. Res. 2015, 7, 627–635. [Google Scholar]

- Marquardt, P.; Seide, R.; Vissiennon, C.; Schubert, A.; Birkemeyer, C.; Ahyi, V.; Fester, K. Phytochemical characterization and in vitro anti-inflammatory, antioxidant and antimicrobial activity of Combretum collinum Fresen leaves extracts from Benin. Molecules 2020, 25, 288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mvongo, C.; Noubissi, P.A.; Kamgang, R.; Minka, C.S.M.; Mfopa, A.; Oyono, J.L.E. Phytochemical studies and in vitro antioxidant potential of two different extracts of Crinum jagus. Int. J. Pharm. Sci. Res. 2015, 6, 2354–2358. [Google Scholar]

- Suja, S.; Varkey, I.C. Medicinal and Pharmacological Values of Cyanthillium Cinereum (Poovamkurunilla) Extracts: Investigating the Antibacterial and Anti-Cancer Activity in Mcf-7 Breast Cancer Cell Lines. Int. J. Res. Anal. Rev. 2019, 6, 412–415. [Google Scholar]

- Bharti, S.; Yadav, S.; Panday, J. Evaluation of anti-anxiety activity of the leaves of Cyanthillium cinereum. NeuroQuantol. 2023, 21, 733–746. [Google Scholar]

- Ibrahim, B.; Sowemimo, A.; van Rooyen, A.; Van de Venter, M. Anti-inflammatory, analgesic and antioxidant activities of Cyathula prostrata (Linn.) Blume (Amaranthaceae). J. Ethnopharmacol. 2012, 141, 282–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajibesin, K.K.; Essien, E.E.; Adesanya, S.A. Antibacterial constituents of the leaves of Dacryodes edulis. Afr. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2011, 5, 1782–1786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coker, M.E.; Ogundele, O.S. Evaluation of the antifungal properties of extracts of Daniella oliveri. Afr. J. Biomed. Res. 2016, 19, 55–60. [Google Scholar]

- Ifediba, C.J.; Okezie, U.M.; Onyegbule, F.A.; Gugu, T.H.; Egbuim, T.C.; Ugwu, M.C. Antifungal activity of the methanol tuber extract of Dioscorea Dumetorum (Pax). World Wide J. Multidiscip. Res. Dev. 2017, 3, 376–380. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, N.S.; Abdullah, S.Y.; Phin, C.K. Phytochemical constituents from leaves of Elaeis guineensis and their antioxidant and antimicrobial activities. Int. J. Pharm. Pharm. Sci. 2013, 5, 137–140. [Google Scholar]

- Erhabor, J.O.; Oshomoh, E.O.; Timothy, O.; Osazuwa, E.S.; Idu, M. Antimicrobial activity of the methanol and aqueous leaf extracts of Emilia coccinea (Sims) G. Don. Niger. J. Biotechnol. 2013, 25, 37–45. [Google Scholar]

- Unegbu, C.C.; Ajah, O.; Amaralam, E.C.; Anyanwu, O.O. Evaluation of phytochemical contents of Emilia coccinea leaves. J. Med. Bot. 2017, 1, 47–50. [Google Scholar]

- Edrees, W.H.A. The inhibitory effect of Euphorbia hirta extracts against some wound bacteria isolated from Yemeni patients. Chron. Pharm. Sci. 2019, 3, 780–786. [Google Scholar]

- Usman, H.; Abdulrahman, F.I.; Usman, A. Qualitative phytochemical screening and in vitro antimicrobial effects of methanol stem bark extract of Ficus thonningii (Moraceae). Afr. J. Tradit. Complement. Altern. Med. 2009, 6, 289–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dickson, R.A.; Houghton, P.J.; Hylands, P.J.; Gibbons, S. Antimicrobial, resistance-modifying effects, antioxidant and free radical scavenging activities of Mezoneuron benthamianum Baill., Securinega virosa Roxb. &Wlld. and Microglossa pyrifolia Lam. Phytother. Res. Intern. J. Devot. Pharmacol. Toxicol. Evaluat. Nat. Prod. Deriv. 2006, 20, 41–45. [Google Scholar]

- Guo-Cai, W.A.N.G.; LIANG, J.P.; Ying, W.A.N.G.; Qian, L.I.; Wen-Cai, Y.E. Chemical constituents from Flueggea virosa. Chin. J. Nat. Med. 2008, 6, 251–253. [Google Scholar]

- Adekunle, A.A.; Ikumapayi, A.M. Antifungal property and phytochemical screening of the crude extracts of Funtumia elastica and Mallotus oppositifolius. West. Indian Med. J. 2006, 55, 219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kombate, B.; Metowogo, K.; Kantati, Y.T.; Afanyibo, Y.G.; Fankibe, N.; Halatoko, A.W.; Aklikokou, K.A. Phytochemical screening, antimicrobial and antioxidant activities of Aloe buettneri, Mitracarpus scaber and Hannoa undulata used in Togolese Cosmetopoeia. J. Drug Deliv. Ther. 2022, 12, 19–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolulope, O. Phytochemical Screening, Antibacterial Activity and Fatty Acids from Heliotropium indicum. Pharmacogn. J. 2023, 15, 350–352. [Google Scholar]

- Okorondu, S.I.; Akujobi, C.O.; Okorondu, J.N.; Anyado-Nwadike, S.O. Antimicrobial activity of the leaf extracts of Moringa oleifera and Jatropha curcas on pathogenic bacteria. Intern. J. Biol. Chem. Sci. 2013, 7, 195–202. [Google Scholar]

- Agbo, I.A.; HlangothI, B.; Didloff, J.; Hattingh, A.C.; Venables, L.; Govender, S.; van de Venter, M. Comparative evaluation of the phytochemical contents, antioxidant and some biological activities of Khaya grandifoliola methanol and ethyl acetate stem bark, root and leaf extracts. Trop. J. Nat. Prod. Res. 2023, 7, 2829–2836. [Google Scholar]

- Agyare, C.; Dwobeng, A.S.; Agyepong, N.; Boakye, Y.D.; Mensah, K.B.; Ayande, P.G.; Adarkwa-Yiadom, M. Antimicrobial, antioxidant, and wound healing properties of Kigelia africana (Lam.) Beneth. and Strophanthus hispidus DC. Adv. Pharmacol. Pharm. Sci. 2013, 2013, 692613. [Google Scholar]

- Bello, I.; Shehu, M.W.; Musa, M.; Asmawi, M.Z.; Mahmud, R. Kigelia africana (Lam.) Benth.(Sausage tree): Phytochemistry and pharmacological review of a quintessential African traditional medicinal plant. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2016, 189, 253–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Isaiah, O.O.; Olusegun, O.A.; Adesola, O.C.; Samson, A.O. Anti-infective Properties and time-killing assay of Lannea acida extracts and its constituents. Biosci. Bioeng. 2021, 6, 100. [Google Scholar]

- Ouattara, M.B.; Bationo, J.H.; Kiendrebeogo, M.; Nacoulma, O.G. Evaluation of Acute Toxicity, Antioxidant and Antibacterial Potential of Leaves Extracts from Two Anacardiaceae’s Species: Lannea microcarpa Engl. & K. Krause and Mangifera indica L. J. Biosci. Med. 2022, 10, 125–134. [Google Scholar]

- Ngouana, V.; Fokou, P.V.; Menkem, E.Z.; Donkeng, V.F.; Fotso, G.W.; Ngadjui, B.T.; Boyom, F.F. Phytochemical analysis and antifungal property of Mallotus oppositifolius (Geiseler) Müll. Arg.(Euphorbiaceae). Int. J. Biol. Chem. 2021, 15, 414–426. [Google Scholar]

- El-Gied, A.A.A.; Abdelkareem, A.M.; Hamedelniel, E.I. Investigation of cream and ointment on antimicrobial activity of Mangifera indica extract. J. Adv. Pharm. Technol. Res. 2015, 6, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, M.; Saurabh, V.; Tomar, M.; Hasan, M.; Changan, S.; Sasi, M.; Mekhemar, M. Mango (Mangifera indica L.) leaves: Nutritional composition, phytochemical profile, and health-promoting bioactivities. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daniel, P.; Supe, U.; Roymon, M.G. A review on phytochemical analysis of Momordica charantia. Int. J. Adv. Pharm. Biol. Chem. 2014, 3, 214–220. [Google Scholar]

- Mwambete, K.D. The in vitro antimicrobial activity of fruit and leaf crude extracts of Momordica charantia: A Tanzania medicinal plant. Afr. Health Sci. 2009, 9, 34–39. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Dongmo, S.C.M.; Njateng, G.S.S.; Tane, P.; Kuiate, J.R. Chemical composition and antimicrobial activity of essential oils from Aframomum citratum, Aframomum daniellii, Piper capense and Monodora myristica. J. Med. Plants Res. 2019, 13, 173–187. [Google Scholar]

- Azubuike, C.P.; Obiakor, C.V.; Igbokwe, N.H.; Usman, A.R. Antimicrobial and Physical Properties of Herbal Ointments Formulated with Methanolic extracts of Persea americana seed and Nauclea latifolia stem bark. J. Pharm. Sci. Pharm. Pract. 2014, 10, 166–172. [Google Scholar]

- Eze, S.O.; Ernest, O. Phytochemical and nutrient evaluation of the leaves and fruits of Nauclea latifolia (Uvuru-ilu). Communicat. Appl. Sci. 2014, 2, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Usman, H.; Osuji, J.C. Phytochemical and in vitro antimicrobial assay of the leaf extract of Newbouldia laevis. Afr. J. Tradit. Complement. Altern. Med. 2007, 4, 476–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chukwunonye, U.C.E.; Ebele, O.P.; Kenne, T.M.; Gaza, A.S.P. Phytochemical screening and antimicrobial activity of methanol extract and fractions of the leaf of Piliostigma thonningii Schum (Caesalpiniaceae). World Appl. Sci. J. 2017, 35, 621–625. [Google Scholar]

- Premkumar, V.G.; Shyamsundar, D. Antidermatophytic activity of Pistia stratiotes. Indian J. Pharmacol. 2005, 37, 127. [Google Scholar]

- Namukobe, J.; Sekandi, P.; Byamukama, R.; Murungi, M.; Nambooze, J.; Ekyibetenga, Y.; Asiimwe, S. Antibacterial, antioxidant, and sun protection potential of selected ethno medicinal plants used for skin infections in Uganda. Trop. Med. Health 2021, 49, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chukwudozie, I.K.; Ezeonu, I.M. Antimicrobial properties and acute toxicity evaluation of Pycnanthus angolensis stem bark. Sci. Afr. 2022, 16, e01185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kisangau, D.P.; Hosea, K.M.; Lyaruu, H.V.; Joseph, C.C.; Mbwambo, Z.H.; Masimba, P.J.; Sewald, N. Screening of traditionally used Tanzanian medicinal plants for antifungal activity. Pharm. Boil. 2009, 47, 708–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olatokunboh, A.O.; Kayode, Y.O.; Adeola, O.K. Anticonvulsant activity of Rauvolfia vomitoria (Afzel). Afr. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2009, 3, 319–322. [Google Scholar]

- Donkor, A.M.; Mosobil, R.; Suurbaar, J. In vitro bacteriostatic and bactericidal activities of Senna alata, Ricinus communis and Lannea barteri extracts against wound and skin disease causing bacteria. J. Anal. Pharm. Res. 2016, 3, 00046. [Google Scholar]

- Adelanwa, E.B.; Habibu, I. Phytochemical screening and antimicrobial activities of the methanolic leaf extract of Jacaranda mimosifolia D. DON and Sansevieria liberica THUNB. J. Trop. Biosci. 2015, 10, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Kowti, R.; Harsha, R.; Ahmed, M.G.; Hareesh, A.R.; Thammanna Gowda, S.S.; Dinesha, R.; Satish Kumar, B.P.; Irfan Ali, M. Antimicrobial activity of ethanol extract of leaf and flower of Spathodea campanulata P. Beauv. Res. J. Pharm. Biol. Chem. Sci. 2010, 1, 691–698. [Google Scholar]

- Aliyu, M.S.; Hanwa, U.A.; Tijjani, M.B.; Aliyu, A.B.; Ya’u, B. Phytochemical and antibacterial properties of leaf extract of Stereospermum kunthianum (Bignoniaceae). Niger. J. Basic Appl. Sci. 2009, 17, 235–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojiako, O.A.; Igwe, C.U. A time-trend hypoglycemic study of ethanol and chloroform extracts of Strophanthus hispidus. J. Herbs Spices Med. Plants 2009, 15, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukubye, B.; Ajayi, C.O.; Wangalwa, R.; Kagoro-Rugunda, G. Phytochemical profile and antimicrobial activity of the leaves and stem bark of Symphonia globulifera Lf and Allophylus abyssinicus (Hochst.) Radlk. BMC Complement. Med. Ther. 2022, 22, 223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adewumi, S.S.; Akinpelu, B.A.; Akinpelu, D.A.; Aiyegoro, O.A.; Alayande, K.A.; Agunbiade, M.O. Studies on wound healing potentials of the leaf extract of Terminalia avicennioides (Guill. & parr.) on wistar rats. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2020, 133, 285–297. [Google Scholar]

- Yadav, E.; Singh, D.; Yadav, P.; Verma, A. Attenuation of dermal wounds via downregulating oxidative stress and inflammatory markers by protocatechuic acid rich n-butanol fraction of Trianthema portulacastrum Linn. in wistar albino rats. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2017, 96, 86–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ebi, G.C.; Ifeanacho, C.J.; Kamalu, T.N. Antimicrobial properties of Uvaria chamae stem bark. Fitoterapia 1999, 70, 621–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akinduti, P.A.; Emoh-Robinson, V.; Obamoh-Triumphant, H.F.; Obafemi, Y.D.; Banjo, T.T. Antibacterial activities of plant leaf extracts against multi-antibiotic resistant Staphylococcus aureus associated with skin and soft tissue infections. BMC Complement. Med. Ther. 2022, 22, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kouakou, A.B.; Megnanou, R.M. Potential treatment of mycosic dermatoses by shea (Vitellaria paradoxa) nuts hulls and press cakes: In vitro efficacy of their methanolic extracts. Arab. J. Med. Aromat. Plants 2021, 7, 342–351. [Google Scholar]

- Ndukwe, I.G.; Amupitan, J.O.; Isah, Y.; Adegoke, K.S. Phytochemical and antimicrobial screening of the crude extracts from the root, stem bark and leaves of Vitellaria paradoxa (GAERTN. F). Afr. J. Biotechnol. 2007, 6, 1905–1909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmourlo, G.; Mendonça-Filho, R.R.; Alviano, C.S.; Costa, S.S. Screening of antifungal agents using ethanol precipitation and bioautography of medicinal and food plants. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2005, 96, 563–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashalata, N.; Swarnalata, N.; Laitonjam, W.S. Phytochemical Constituents, Total Flavonoid and Phenolic Content of Xanthosoma sagittifolium Stem Extracts. J. Acad. Indust. Res. 2021, 10, 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Onuora, C.C.; Florence, C.C. Antimycotic Efficacy of Aqueous Extract from Xylopia aethiopica Against Some Zoophilic Dermatophytes. GSJ 2020, 8, 4595–4604. [Google Scholar]

- Usman, L.A.; Akolade, J.O.; Odebisi, B.O.; Olanipekun, B. Chemical Composition and antibacterial activity of fruit essential oil of Xylopia aethiopica D. grown in Nigeria. J. Ess. Oil Bear. Plants 2016, 19, 648–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Family | Plant Species | Habit and Conservation Status | Country | Local Name | Plant Part(s) Used | Mode of Preparation | Ailment | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acanthaceae | Acanthus montanus (Nees) T. Anderson | Herb; LC | Nigeria | Mbara ekpe (Akwaibom) | Leaves | Poultice. | Abscess, boils, whitlow, and wounds | [15] |

| Acanthaceae | Afrofittonia silvestris Lindau | Herb; VU | Nigeria | Mmeme (Akwaibom) | Whole plant | Crushed and the juice is topically used for skin spots; Poultice is applied to whitlow. | Skin spots and whitlow | [15] |

| Acanthaceae | Brillantaisia lamium (Nees) Benth. | Herb; No Record | Cameroon | No record | Aerial parts | Decoction of aerial parts is used to bath. | Skin infections | [26] |

| Acanthaceae | Justicia insularis T. Anders | Herb; No Record | Nigeria | No record | Whole plant | Crushed and the juice applied; poultice. | Skin spots | [15] |

| Aiozoaceae | Trianthema portulacastrum L. | Herb; No Record | Nigeria | Ntia ntia ikon (Akwa Ibom) | Leaves | Decoction is used for bathing the affected area. | Wounds | [15] |

| Amaranthaceae | Achyranthes aspera L. | Herb; No Record | Nigeria | Udok mbiok | Leaves | Crushed and juice applied. | Skin ulcers | [15] |

| Amaranthaceae | Alternanthera bettzickiana (Regel) G. Nicholson | Herb; No Record | Nigeria | Nkpok isip essien | Leaves | Crushed and the juice applied. | Skin spots, measles | [15] |

| Amaranthaceae | Amaranthus caudatus L. | Herb; No Record | Nigeria | Inyan afia | Leaves | Leaf juice mixed with kaolin is applied. | Abscess, boil, eczema, and skin eruption | [15] |

| Amaranthaceae | Celosia globosa Schinz | Herb; No Record | Cameroon | NA | Leaves | Decoction of the leaves in Cameroon. | Athlete’s foot | [26] |

| Amaranthaceae | Cyathula prostrata (L.) Blume | Herb; No Record | Cote d’Ivoire, Guinea and Nigeria | Nkibe ubuk | Leaves | Decoction is taken orally in Nigeria, and Cote d’Ivoire for leprosy; the juice from macerated leaves is applied to cuts and bruises in Guinea. | Leprosy, skin spots, scabies, sores, and rashes | [15,27,28] |

| Amaryllidaceae | Allium cepa L. | Herb; LC | Nigeria and West Africa | Alubosa (Yoruba) | Bulb | Poultice. | Scorpion sting and skin disease | [15,29] |

| Amaryllidaceae | Allium sativum L. | Herb; LC | Nigeria | Alubosa Ayu (Yoruba) | Clove | Poultice. | Skin spots, burns, ulcers, and scorpion sting | [15] |

| Amaryllidaceae | Crinum jagus (Thompson) Dandy | Herb; LC | Nigeria | Ayim ekpo, ekop-eyen (Akwa ibom), Ogede odo (Yoruba) | Bulb | Poultice. | Whitlow | [15] |

| Anacardiaceae | Anacardium occidentale L. | Tree; LC | Nigeria | Kashu, Cashew | Leaves | Poultice | Ringworm and leprosy | [15] |

| Anacardiaceae | Lannea acida A. Rich. | Shrub; LC | Nigeria and Senegal | Ayara nsukakara | Leaves | Crushed and juice applied. | Burns and skin infections | [15,30,31] |

| Anacardiaceae | Lannea microcarpa A. Rich | Tree; LC | Republic of Benin | Sinman | Root bark | The root bark is ground to powder and applied topically. | Wounds | [16] |

| Anacardiaceae | Mangifera indica L. | Tree; DD | Nigeria | Mongoro | Leaves | Decoction for bathing and applied topically. | Skin spots | [15] |

| Anacardiaceae | Ozoroa pulcherrima (schweinf.) R. & A. | Shrub; No Record | Republic of Benin | Mukentétié | Root bark | The root bark is ground into powder and applied topically. | Wounds | [16] |

| Annonaceae | Annickia chlorantha (Oliv.) Setten & Maas | Tree; LC | Nigeria and West Africa | Osopa (Yoruba) | Leaves, stem bark | Crushed and juice applied. | Sores, ulcers, and wounds | [32] |

| Annonaceae | Annona senegalensis Pers. | Tree; LC | Ghana, Mali, Nigeria, and Togo | Sawa-sawa (Yoruba), Tchoutchourè (Togo) | Leaves and fruits | A poultice made from the leaves is used for leprosy, sores, and wounds in Ghana, Mali, and Nigeria. Decoction of the leaves and fruits is taken orally for aphthous ulcers in Togo. | Leprosy, sores, and wounds | [15,27,33,34] |

| Annonaceae | Monodora myristica (Gaertn.) Dunal | Tree; LC | Nigeria | Enwun | Seeds | Seeds are ground to powder and applied externally. | Pediculosis and sores | [15] |

| Annonaceae | Uvaria chamae P. Beauv. | Shrub; LC | Nigeria and Senegal | Nkarika ekpo | Root | Sap from the crushed root is applied topically. | Snakebites and wounds | [15,35] |

| Annonaceae | Xylopia aethiopica (Dunal) A. Rich | Tree; No Record | Republic of Benin | Nadofacha | Seeds | Dried seeds are ground into powder and applied topically. | Wounds | [16] |

| Apocynaceae | Alstonia boonei De Wild. | Tree; LC | Cameroon, Cote d’Ivoire; Nigeria, Senegal | Ahun (Yoruba) | Stem bark | Crushed and applied. | Snakebites | [15,36] |

| Apocynaceae | Calotropis procera (Aiton) W.T. Aiton | Herb; LC | Gambia, Nigeria, and Senegal | Bomubomu (Yoruba) | Leaves | The poultice made from the leaves. | Smallpox, skin eruption, snakebites, and wounds | [15,27,37] |

| Apocynaceae | Funtumia elastica (Preuss) Stapf | Tree; LC | Cameroon and Nigeria | Eto okpo | Leaves | Juice from the crushed leaves is applied topically. | Snakebites and wounds | [15,36] |

| Apocynaceae | Holarrhena floribunda (G.Don) T.Durand & Schinz | Tree; LC | Togo | Kororo (Togo) | Leaves | Decoction of the leaves is taken orally. | Aphthous ulcers | [34] |

| Apocynaceae | Leptadenia hastata (Pers.) Decne | Climber; No Record | Senegal | Mboom (wolof) Duto (mandingo) | Stem | Infusion of woody stems is taken orally. | Snakebites | [15] |

| Apocynaceae | Rauvolfia vomitoria Afzel | Tree; LC | Nigeria | kiko | Leaves | Crushed and applied. | Ringworm and itchy body | [15] |

| Apocynaceae | Strophanthus hispidus DC. | Shrub; LC | Cote d’Ivoire, Ghana, Guinea, Nigeria, and Senegal | Ibok idan | Root bark | Crushed and applied. | Snakebites, scorpion stings, cuts, skin ulcers, and sores | [15,28,38,39,40] |

| Araceae | Anchomanes difformis (Blume) Engl | Herb; LC | Cote d’Ivoire and Nigeria | Nkokot | Bulb | Crushed and sap applied. | Wounds | [15,41] |

| Araceae | Colocasia esculenta (L.) Schott | Herb; LC | Nigeria and Cameroon | Ikpon ekpo Ndai (Cameroon) | Whole plant, tubers | Crushed and applied to the sore. Paste from grated tubers is applied on the part affected by whitlow and tied with a band. | Insect bites, sores, and whitlow | [15,17] |

| Araceae | Elaeis guineensis Jacq. | Tree; LC | Cameroon, Ghana, and Nigeria | Eyop | Fruit pericarp | Peeled and applied. | Boil, scabies, and wounds | [15,36,40] |

| Araceae | Pistia stratiotes L. | Herb; LC | Nigeria | Amana mmon | Whole plant | Powdered dry plant is applied topically. | Wounds and sores | [15] |

| Araceae | Xanthosoma sagittifolium (L.) Schott | Herb; No Record | Nigeria | Ikpon mbakara | Leaves | Crushed and juice applied. | Smallpox, skin spots, and fungal skin infection | [15] |

| Asparagaceae | Agave sisalana Perrine | Herb; No Record | Togo | Kolgragou | Root | Decoction of the root is taken orally. | Aphthous ulcers | [34] |

| Asparagaceae | Dracaena arborea (Willd.) Link | Tree; LC | Nigeria | Okno | Root bark | Poultice. | Boils and burns | [15] |

| Asparagaceae | Sansevieria liberica Gérôme & Labroy | Herb; No Record | Nigeria | Okono ekpe | Leaves, stem bark, Root | Decoction, poultice. | Eczema and snakebites | [15] |

| Asphodelaceae | Aloe vera (L.) Burm. f. | Herb; LC | Nigeria, Cameroon, Ghana, Togo, and Benin | Eti erin (Yoruba) | Leaves | Gel from the crushed leaves is applied topically. | Skin infections and wounds | [15,17] |

| Asteraceae | Acanthospermum hispidum DC | Herb; No Record | Togo | Kpangsoyè | Whole plant | Decoction of the whole plant is taken orally. | Aphthous ulcers | [34] |

| Asteraceae | Ageratum conyzoides L. | Herb; LC | Nigeria | Imi esu (Yoruba) | Whole plant | Crushed in water and applied topically. The same preparation is taken orally for general skin infections. | Rashes, skin ulcers, and wounds | [15,42] |

| Asteraceae | Aspilia africana (Pers.) C.D. Adams | Herb; No Record | Cameroon, Liberia, Nigeria, and Sierra Leone | Edemeron Wowoh (Cameroon) | Leaves | Decoction of the leaves in Cameroon. Leaves are crushed or squeezed on the wound in Nigeria and Cameroon. | Wounds | [15,17,20,27] |

| Asteraceae | Bidens pilosa L. | Herb; No Record | Cameroon, Cote d’Ivoire, Nigeria | Ntafion ison Shoctesuc (Cameroon) | Leaves | Crushed and juice applied. | Insect bites and wounds | [15,17,41] |

| Asteraceae | Chromolaena odorata (L.) R.M. King & H. Rob. | Herb; LC | Cameroon, Ghana, Nigeria | Mbiet (Ghana) Awolowo (Yoruba) Twigi (Cameroon) | Leaves | Crushed and juice applied. A poultice made from the leaves is used to cover the wound. | Rashes, scorpion sting, snakebites, and Wounds | [15,17,40] |

| Asteraceae | Crassocephalum biafrae (Oliv. & Hiern) S. Moore | Herb; No Record | Nigeria | Mkpafit | Leaves | Dried leaves are ground into powder and applied to the wound. | Wounds | [15] |

| Asteraceae | Crassocephalum crepidioides (Benth.) S. Moore | Herb; No Record | Nigeria | Mkpafit | Leaves | Juice from the crushed leaves is applied. | Boil, burns, and wounds | [15] |

| Asteraceae | Cyanthillium cinereum (L.) H.Rob | Herb; No Record | Togo | Kogbèdiyè | Aerial part | Decoction is taken orally. | Aphthous ulcers | [34] |

| Asteraceae | Emilia coccinea (Sims) G. Don | Herb; No Record | Nigeria, Cameroon | Utime nse Nsefouse (Cameroon) Femefouse (Cameroon) | Leaves | Juice from the crushed leaves is applied. | Measles, rashes, wounds | [15] |

| Asteraceae | Emilia sonchifolia (L.) DC | Herb; No Record | Nigeria | Utime nse, usio mmon | Leaves | Juice from the crushed leaves is applied. | Measles, rashes, and Wounds | [15] |

| Asteraceae | Laggera decurrens (Vahl) Hepper & J.R.I. Wood | Herb; No Record | Nigeria | Ewedorun (Yoruba) | Whole plants | Decoction of the whole plant is applied to the wound with cotton wool. | Wounds | [42] |

| Asteraceae | Tridax procumbens L. | Herb; LC | Nigeria | Ayara utimense (Akwa Ibom), imi esu or apasa funfun (Yoruba) | Leaves | Decoction of the leaves is taken orally. | Skin spots | [15] |

| Asteraceae | Vernonia amygdalina Delile | Shrub; LC | West Africa | Etidod (Akwa ibom) Ewuro (Yoruba) Ying (Cameroon) | Leaves | Juice from the crushed leaves is applied externally. The juice is mixed with palm oil in Yoruba culture. | Chickenpox, measles, ringworm skin spots, skin infections and wounds | [15,40] |

| Bignoniaceae | Kigelia africana (Lam.) Benth | Tree; LC | Cote d’Ivoire, Nigeria, and Senegal | Ntabinim | Stem bark | Dried stem bark is ground to powder and applied topically. | Leprosy, snakebites, sores, and wounds | [15,31,32] |

| Bignoniaceae | Newbouldia laevis (P. Beauv.) Seem | Tree; LC | Cote d’Ivoire and Nigeria | Tumo | Stem bark and root | Decoction of stem back and root is taken orally. | Boils and skin spots | [15] |

| Bignoniaceae | Spathodea campanulata P. Beauv. | Tree; LC | Nigeria | Esenim | Stem bark | Infusion of stem back is applied externally for burns, bruises, skin infections, ulcers and wounds. | Skin infections, ulcers and wounds | [15,41] |

| Bignoniaceae | Stereospermum kunthianum Cham. | Shrub; LC | Togo | Essogbalou | Leaves | Decoction is taken orally for herpes sores. | Herpes sores | [34] |

| Boraginaceae | Heliotropium indicum L. | Herb; LC | Benin, Ghana, Nigeria, Senegal, and Togo | Ewe akuko (Yoruba); Soucondiè (Togo), Koklosou dinkpadja (Benin) | Leaves and whole plant | Decoction of the leaves is taken orally for boil in Nigeria; a poultice made from the leaves is applied to wounds and insect bites in Ghana and Senegal. Decoction of the whole plants is taken orally for aphthous ulcers in Togo. | Boil, insect bites, and ulcers | [15,31,32,34,43] |

| Brassicaceae | Brassica oleracea L. | Herb; No Record | Nigeria | Efere mbakara | Leaves | Poultice. | Ringworm and skin ulcers | [15] |

| Burseraceae | Commiphora africana (A. Rich.) Engl. | Tree; LC | Nigeria | Eto komfi itiat | Stem bark | Decoction of the stem back is taken orally. | Rashes caused by measles | [15] |

| Burseraceae | Dacryodes edulis (G. Don) H.J. Lam | Tree; No Record | Cote d’Ivoire and Nigeria | Eben | Leaves | Decoction is applied externally. | Leprosy and skin spots | [15,27,44] |

| Burseraceae | Dacryodes klaineana (Pierre) H.J. Lam | Tree; LC | Nigeria | Eben ikot | Leaves and root | Decoction is of the leaves and root taken orally. | Skin spots | [15] |

| Cannabaceae | Trema orientale (L.) Blume | Tree; LC | Cameroon and Nigeria | No record | Whole plant | Decoction of the whole plant is used to bath or applied topically. | Abscesses and skin spots | [15,45] |

| Capparaceae | Maerua angolensis DC | Tree; LC | Republic of Benin | Fetounanfè | Root bark | The root bark is ground to powder and applied topically. | Wounds | [16] |

| Caricaceae | Carica papaya L. | Tree; LC | Cameroon | Pawpaw | Leaves | Leaf juice is applied on fresh wounds. | Wounds | [17] |

| Celastraceae | Apodostigma pallens (Planch. ex Oliv.) R.Wilczek | Climber; No Record | Republic of Benin | Mukentetie | Root | The chewed root is applied topically. | Wounds | [16] |

| Celastraceae | Gymnosporia senegalensis L. E. T. Loesener | Shrub; LC | Republic of Benin | Moukorou | Root bark | Root bark is ground to powder and applied topically. | Wounds | [16] |

| Celastraceae | Maytenus senegalensis (Lam.) Exell | Shrub; No Record | Togo | Liakpangsoyè (Togo) | Whole plant | Decoction of the leaves is taken orally. | Aphthous ulcers | [34] |

| Chrysobalanaceae | Maranthes kerstingii (Engl.) Prance | Tree; No Record | Togo | Poundoulayzay (Togo) | Leaves | Decoction of the leaves is taken orally. | Aphthous ulcers | [34] |

| Chrysobalanaceae | Parinari curatellifolia Planch. ex Benth. | Tree; LC | Togo | Malay (Togo) | Leaves | Decoction of the leaves is taken orally. | Aphthous ulcers | [34] |

| Clusiaceae | Allanblackia floribunda Oliv | Tree; VU | Nigeria | Udiaebion, ekporo-enin | Leaves | Decoction of the leaves is used for bathing. | Skin spots | [15] |

| Clusiaceae | Symphonia globulifera L. f. | Tree; LC | Cameron and Nigeria | No record | Bark, roots, and resin | Boiled bark and roots are used as a wash to treat itch, and the resin is used to treat wounds and prevent skin infections in Cameroon. Leaves decoction for skin disease and skin spots in Nigeria. | Itching, skin infections, and wounds | [15,46,47] |

| Cochlospermaceae | Cochlospermum planchonii Hook. f. | Shrub; No Record | Togo | Kalantcheyah (Togo) | Leaves | Decoction of the leaves is taken orally. | Aphthous ulcers | [34] |

| Combretaceae | Anogeissus leiocarpus (DC.) Guill. & Perr. | Tree; No Record | Cote d’Ivoire and Nigeria | Kolou (Togo) | Leaves and Stem bark | Infusion of stem bark in water is mixed with honey for skin ulcers, sores, and wounds. Decoction of leaves for aphthous ulcer. | Wounds, skin ulcers, and sores | [15,34,41] |

| Combretaceae | Combretum collinum Fresen | Tree; LC | Republic of Benin | Gberukporo | Root bark | The root bark is ground to powder and applied topically. | Wounds | [16] |

| Combretaceae | Combretum glutinosum Perr. Ex DC | Tree; LC | Republic of Benin | Oudadaribou | Root bark | Powdered root bark is incinerated and applied topically. | Wounds | [16] |

| Combretaceae | Combretum hypopilinum Diels | Shrub; No Record | Gambia | Katanyangkungo | Leaves and root | Decoction of both leaves and root is used to bath. | Itchy body | [48] |

| Combretaceae | Combretum micranthum G. Don | Shrub; LC | Cote d’Ivoire, Nigeria, and West Africa | Asaka | Leaves | Infusion of the leaves is taken orally. | Leprosy, sores and skin spots | [27,31] |

| Combretaceae | Combretum racemosum P. Beauv. | Shrub; No Record | Nigeria | Uyai asaka | Leaves | Juice from the crushed leaves is taken orally. | Skin spots | [15] |

| Combretaceae | Combretum sericeum G. Don | Tree; No Record | Republic of Benin | Cocopourka | Root bark | The root bark is ground to powder and applied topically. | Wounds | [16] |

| Combretaceae | Combretum zeyheri Engl. & Diels | Climber; LC | Nigeria | Ndia asaka | Leaves | Poultice. | Mump, skin eruption, and warts | [15] |

| Combretaceae | Guarea thompsonii Sprague & Hutch. | Tree; VU | Nigeria | Afia ikpok eto | Stem bark | Sap produced from the crushing of the stem bark is applied topically. | Skin diseases | [15] |

| Combretaceae | Guiera senegalensis J.F. Gmel. | Shrub; LC | Guinea, Senegal, and West Africa | No record | Leaves and twigs | Decoction of the leaves is taken for leprosy. The twigs are chewed for scorpion stings. | Leprosy and scorpion bites | [31,35,49] |

| Combretaceae | Pteleopsis suberosa Engl. et Diels | Tree; LC | Togo | Kézinzinang | Leaves and bark | Decoction is taken orally. | Aphthous ulcers | [34] |

| Combretaceae | Terminalia avicennioides Guill. & Perr. Fl. Seneg. Tent. | Tree; LC | Togo | Koyèkouloumryè | Aerial part | Decoction is taken orally | Aphthous ulcers | [34] |

| Combretaceae | Terminalia ivorensis A. Chev | Tree; VU | Cote d’Ivoire, Ghana, and Nigeria | Nkot ebene | Stem bark | Infusion of the stem bark is applied topically. | Sores and ulcers | [15,27,28] |

| Combretaceae | Terminalia superba Engl. & Diels | Tree; No Record | Nigeria | Afia eto | Leaves | Juice from the crushed leaves is applied externally. | Skin spots | [15] |

| Commelinaceae | Commelina benghalensis L. | Herb; LC | Cameroon | Wiwih | Latex | Latex is applied to the affected skin. | Ringworm | [17] |

| Commelinaceae | Commelina diffusa Burn. f. | Climber; LC | Nigeria | Ekpa ekpa ikpaha | Whole plant | Dried whole plant is ground to powder and applied externally. | Sores and burns | [15] |

| Convulvulaceae | Ipomoea pileata Roxb | Herb; No Record | Nigeria | Mkpafiafian | Leaves | Infusion of the leaves is applied topically. | Skin spots | [15] |

| Convulvulaceae | Ipomoea quamoclit L. | Herb; No Record | Nigeria | Ediam ikanikot | Leaves | Poultice. | Boil and wounds | [15] |

| Cucurbitaceae | Citrullus colocynthis (L.) Schrad. | Climber; No Record | Nigeria | Ikon | Seeds | Seeds are ground and applied topically. | Abscess and skin spots | [15] |

| Cucurbitaceae | Cucurbita maxima Duchesne | Climber; No Record | Ghana and Nigeria | Ikim | Leaves | Juice from the crushed leaves is applied topically. | Boil and skin spots | [15,27] |

| Cucurbitaceae | Momordica balsamina L. | Climber; No Record | Nigeria and Senegal | Mbiadon edon | Whole plant | Poultice. | Boil | [15] |

| Cucurbitaceae | Momordica charantia L. | Climber; No Record | Ghana, Mali, Nigeria, and Senegal | Mbiadon edon Nyenyen (Ghana) | Fruit | Poultice; infusion of whole plants is taken orally in Ghana for snakebites. | Boil, burns snakebites, and ulcers | [15,40,50] |

| Dioscoraceae | Dioscorea dumetorum (Kunth) Pax | Climber; No Record | Nigeria | Enem (Akwa Ibom); Esuru (Yoruba) | Leaves | Decoction of the leaves is applied topically. | Skin spots | [15] |

| Dioscoraceae | Dioscorea rotundata Poir | Climber; No Record | Nigeria | Eko | Leaves | Infusion of the leaves is applied topically. | Burns and skin spots | [15] |

| Ebenaceae | Diospyros canaliculata De Wild. | Tree; LC | Cameroon | No record | Stem bark | No record. | Skin infections | [26] |

| Euphorbiaceae | Acalypha fimbriata Schumach. & Thonn | Herb; No Record | Nigeria | Okokho nyin | Leaves and twigs | Decoction of leaves and twigs is used topically to bath. | Skin spots and sores | [15] |

| Euphorbiaceae | Acalypha hispida Burm. f. | Shrub; No Record | Nigeria | Okokho nyin | Leaves | Decoction of leaves is used externally to bath. | Skin spots and sores | [15] |

| Euphorbiaceae | Acalypha wilkesiana Müll. Arg. | Shrub; No Record | Nigeria | Okokho nyin | Leaves | Decoction of leaves is used topically to bath. | Skin spots | [15] |

| Euphorbiaceae | Alchornea cordifolia (Schumach. & Thonn.) Müll. Arg. | Shrub; No Record | Ghana, Nigeria, and West Africa | Mbom | Leaves and fruits | Infusion of the leaves; juice from the crushed fruits is applied topically. | Skin spots and skin ulcers, skin spots, scorpion stings, and snakebites | [15,29,40] |

| Euphorbiaceae | Alchornea laxiflora (Benth.) Pax & K. Hoffm. | Shrub; LC | Nigeria | Nwariwa | Leaves | Infusion of the leaves is used for skin spots and skin ulcers. | Skin spots and ulcers | [15] |

| Euphorbiaceae | Euphorbia hirta L. | Herb; No Record | Nigeria | Etinkene ekpo | Leaves | The poultice made from the leaves is applied topically. | Snakebites, scorpion stings, and insect bites | [15] |

| Euphorbiaceae | Jatropha curcas L. | Shrub; LC | Togo | Essogbalou (Togo) Medjai (Cameroon) | Leaves and latex | Decoction of the leaves is taken for cancer sores. Latex from the cut stem is applied to the wounds. | Cancer sores and wounds | [17,34] |

| Euphorbiaceae | Jatropha gossypiifolia L. | Shrub; LC | Nigeria | Eto oko obio nsit | Leaves | Juice from the crushed leaves is applied topically. | Eczema, ringworm, and scabies | [15] |

| Euphorbiaceae | Macaranga barteri Mull. Arg. | Shrub; LC | Ghana | Opam | Bark | Decoction of bark is taken orally. | Footrot | [50] |

| Euphorbiaceae | Mallotus oppositifolius (Geiseler) Müll. Arg. | Herb; LC | Cameroon, Ghana, and Nigeria | Uman nwariwa | Leaves or stem back | Decoction of the leaves is applied topically. | Skin spots | [15,40,51] |

| Euphorbiaceae | Manniophyton fulvum Müll. Arg. | Climber; No Record | Nigeria | Ekonikon | Leaves and stem bark | Infusion of the leaves and stem bark is applied topically. | Scabies, ringworm, and eczema | [15] |

| Euphorbiaceae | Ricinus communis L. | Shrub; LC | Nigeria | Eto kasto | Leaves and seeds | Infusion of the leaves; expression of the oil from the seeds. | Chickenpox smallpox, and skin spots | [15] |

| Fabaceae | Abrus precatorius L. | Climber; No Record | Nigeria | Nneminua (Akwa ibom); Oju ologbo (Yoruba) | Leaves | Juice from the crushed leaves is applied topically. | Skin spots | [15] |

| Fabaceae | Afzelia africana Sm. | Tree; VU | Nigeria | Eyin mbukpo | Stem bark | Sap produced from the crushed stem back is applied topically. | Leprosy, pimples, skin eruption, and wounds | [15] |

| Fabaceae | Afzelia bella Harms | Tree; LC | Nigeria | Enyin mbukpo | Leaves | Juice from the crushed leaves is applied topically. | Pimples | [15] |

| Fabaceae | Aganope stuhlmannii (Taub.) Adema | Tree; LC | Togo | Kpodougboou | Aerial part | Decoction is taken orally. | Aphthous ulcers | [34] |

| Fabaceae | Albizia lebbeck (L.) Benth. | Tree; LC | Nigeria | Ubam | Stem bark | Poultice. | Eczema and insect bites | [15] |

| Fabaceae | Arachis hypogaea L. | Herb; LC | Senegal | Gerte (wolof) Jamba katalig (mandingo) | Nut | Peanut oil mixed with powdered leaf of A. digitata is applied to wounds. | Burns | [52] |

| Fabaceae | Baphia nitida Lodd. | Tree; LC | Ghana and Nigeria | Afuo | Leaves | Juice from the crushed leaves is applied topically. | Boils, skin ulcers, and wounds | [15,40] |

| Fabaceae | Burkea africana Hook | Tree; LC | Togo | Tchangbali (Togo | Leaves | Decoction of the leaves is taken orally. | Aphthous ulcers | [34] |

| Fabaceae | Cajanus cajan (L.) Huth | Herb; No Record | Nigeria and Togo | Nkoti (Akwa Ibom); Otili (Yoruba); Assongoyè (Togo | Seeds and whole plant | Seeds are ground into powder and applied topically for measles, smallpox, sores, skin ulcers, and skin spots in Nigeria. Decoction of the whole plants is taken orally for aphthous ulcers in Togo. | Measles, sores, skin ulcers, skin spots, and smallpox | [15,34] |

| Fabaceae | Daniellia oliveri (Rolfe) Hutch. & Dalziel | Tree; LC | Nigeria and Togo | Enan-eto (Akwa Ibom); Hemou (Togo) | Root, bark, and leaves | Sap from the crushed root bark is applied topically in Nigeria. Leaves and bark are macerated and taken orally for aphthous ulcers in Togo. | Aphthous ulcers and rashes | [15,34] |

| Fabaceae | Detarium microcarpum Guill. & Perr | Tree; LC | Nigeria and Togo | Kpayè (Togo) | Bark, leaves, and roots | Dried roots and leaves are ground into powder and applied externally for cuts, ulcers and wounds in Nigeria. Stem bark is macerated and taken orally for aphthous ulcers in Togo. | Aphthous ulcers and wounds | [15,34] |

| Fabaceae | Distemonanthus benthamianus Baill. | Tree; LC | Nigeria | Eto-afia | Root bark | Decoction of the root bark is taken orally. | Skin spot | [15] |

| Fabaceae | Faidherbia albida (Delile) A. Chev | Tree; LC | Gambia | Bubrick | Root | NA | Snakebites | [48] |

| Fabaceae | Lonchocarpus cyanescens (Schumach. & Thonn.) Benth. | Shrub; No Record | Nigeria | Awa | Leaves | Infusion of the leaves is applied topically. | Skin ulcers and skin spots | [15] |

| Fabaceae | Lonchocarpus sericeus (Poir.) Kunth | Tree; LC | Nigeria | Ipappo (Yoruba) | Leaves | Decoction of the leaves with Vernonia macrocynus O.Hoffm is taken orally. | Skin infections | [42] |

| Fabaceae | Parkia biglobosa (Jacq.) R. Br. ex G. Don | Tree; LC | Nigeria and Togo | Ukon uyayak (Akwa Ibom); Igi iru (Yoruba); Soulou (Togo) | Stem bark | Dried stem bark is ground to powder for ringworms in Nigeria. Decoction of the stem bark is used externally for skin infection in Nigeria and taken orally for aphthous ulcers in Togo. | Aphthous ulcers, ringworm, and skin infection | [15,34] |

| Fabaceae | Parkia clappertoniana Keay | Tree; No Record | Nigeria and Ghana | Igba (Yoruba) | Leaves | Leaves are ground with Loranthus with potash and taken orally with pap (Nigeria); Extract from the husk is used for sores and wounds in Ghana. | Skin infections, sores, and wounds | [42,53] |

| Fabaceae | Pentaclethra macrophylla Benth | Tree; LC | Nigeria | Ukana | Stem bark | Decoction or infusion is used topically. | Skin spots | [15] |

| Fabaceae | Piliostigma thonningii (Schum.) Milne-Redh. | Tree; No Record | Republic of Benin, Nigeria, and Togo | Tilabaati (Benin); Pambakou (Togo) Abafe (Nigeria) | Root and root bark | Decoction of the root and fruit is taken orally for herpes sores and other skin diseases. The root bark is ground to powder and applied topically. | Herpes sores and skin disease | [16,34,42] |

| Fabaceae | Pterocarpus erinaceus Poir. | Tree; No Record | Nigeria and Togo | Ukpa (AkwaIbom, Nigeria); Tém (Togo) | Leaves and stem bark | Decoction of the leaves and stem bark is used externally for skin spots in Nigeria. Latex from the plant is applied topically for herpes sores and ringworm in Togo. | Herpes, ringworm sores, and skin spots | [15,34] |

| Fabaceae | Pterocarpus santalinoides L’Hér. ex DC. | Tree; No Record | Nigeria | Nkpa-inyan | Leaves | Decoction is used topically. | Skin spots | [15] |

| Fabaceae | Senegalia ataxacantha (DC.) Kyal. & Boatwr. | Tree; LC | Nigeria | Mbara okpok | Leaves | Juice from the crushed leaves is applied topically. | Burn and sores | [15] |

| Fabaceae | Senna alata L (Roxb | Shrub; LC | Nigeria | Asunwon (Yoruba); Akoria (Bennin) | Leaves and stem | Juice from the leaves and stem is applied externally. | Ringworms and skin spots | [42] |

| Fabaceae | Senna hirsuta (L.) H.S.Irwin & Barneby | Herb; No Record | Cameroon | Tulushine | Leaves | Decoction of leaves is taken orally. | General skin diseases | [17] |

| Fabaceae | Senna occidentalis (L.) Link | Herb; LC | Nigeria | Flower uduk-ikot | Leaves | Juice from the crushed leaves is applied topically. | Abscess and chickenpox | [15] |

| Fabaceae | Senna tora (L.) Roxb. | Herb; No Record | Nigeria | Mfan udukikot | Leaves | Infusion of the leaves is applied topically. | Skin spots and sores | [15] |

| Fabaceae | Tamarindus indica L. | Tree; LC | Nigeria and Togo | Okukuk mbakara (Akwa Ibom, Nigeria); Nidié (Togo) | Leaves and root bark | Decoction of the root bark is used externally for bathing for skin spots in Nigeria. Decoction of the leaves is taken orally for aphthous ulcers in Togo. | Aphthous ulcers and skin spots | [15,34] |

| Fabaceae | Tetrapleura tetraptera (Schumach. & Thonn.) Taub. | Tree; LC | Nigeria | Uyayak (Akwa Ibom); Aidan (Yoruba) | Fruits | Oil from the expression of the fruit is used externally for skin spots. | Skin spots | [15] |

| Fabaceae | Vachellia nilotica (L.) P.J.H. Hurter & Mabb | Tree; LC | Senegal | Nep nep (wolof) Mbano (mandingo) | Root | Root infusion is applied topically. | Herpes | [52] |

| Fabaceae | Zornia latifolia Sm. | Herb; No Record | Nigeria | Ubok etikoriko | Leaves | Sap from the crushed leaves or dried leaves ground into powder is applied topically. | Snakebites and scorpion stings | [15] |

| Gentianaceae | Anthocleista djalonensis A. Chev. | Tree; LC | Nigeria | Ibu (Akwa Ibom); Sapo (Yoruba) | Stem bark | Sap from the crushed stem bark is used topically. | Skin spots, sores, ulcers, and wounds | [15] |

| Hypericaceae | Harungana madagascariensis (Lam.) ex Poir. | Tree; LC | Nigeria | Oton | Leaves, stem, root | Infusion of the leaves, stem, and root is used topically. | Skin spots | [15] |

| Hypericaceae | Hypericum Lanceolatum Lam. | Shrub; No Record | Cameroon | No record | Stem bark | No record. | Skin infections | [26] |

| Hypericaceae | Psorospermum febrifugum Spach | Shrub; LC | Cameroon | No record | Stem bark and root | Decoction of the stem bark for skin sores in HIV/AIDS patients. Powdered root is used topically on parasitic skin diseases. It is used for pimples, eruptions, and wounds when ground up and mixed with oil. | Acne, leprosy, skin sores in HIV/AIDS patients, and skin infection. | [54,55] |

| Lamiaceae | Clerodendrum splendens G. Don | Climber; No Record | Mali and Nigeria | Mmon oyot adiaha ekiko | Leaves | Juice from the crushed leaves is applied topically. | Skin spots and snakebites | [15,29] |

| Lamiaceae | Mesosphaerum suaveolens (L.) Kuntze | Herb; No Record | Togo and Gambia | Pinbinè (Togo) Jammakarla (Gambia | Root | Root is macerated and taken orally for aphthous ulcers. Sap is applied to fresh cut. | Aphthous ulcers and fresh cuts | [34,48] |

| Lamiaceae | Solenostemon monostachyus (P. Beauv.) Briq | Herb; No Record | Nigeria | Ntorikwot | Leaves | Juice from the crushed leaves is added to water and applied topically. | Measles | [15] |

| Lamiaceae | Vitex doniana Sweet | Tree; LC | West Africa | Nkokoro | Root | Poultice. | Leprosy and wrinkles | [15,31,56] |

| Malvaceae | Adansonia digitata L. | Tree; No Record | Côte d’Ivoire, Gambia, and Nigeria and | Luru (Hausa) Buback (Gambia) | Leaves and fruits | Juice from the crushed leaves is applied topically. Fruit pulp is applied to body blisters. | Body blisters, scorpion stings, and snakebites | [15,48] |

| Malvaceae | Bombax buonopozense P. Beauv. | Tree; LC | Nigeria | Ukim | Stem bark | Infusion of the stem bark is applied externally. | Ringworm, rashes, and skin spots | [15] |

| Malvaceae | Ceiba pentandra (L.) Gaertn. | Tree; LC | Cote d’Ivoire and Nigeria | Akpu-ogwu (Igbo); Araba (Yoruba); Rimi (Hausa) | Stem bark | Decoction of the stem bark is used for bathing. | Leprosy, sores, and skin ulcers | [15,28] |

| Malvaceae | Glyphaea brevis (Spreng.) Monach | Shrub; LC | Nigeria | Ndodiro | Leaves | Poultice. | Burns and wounds | [15] |

| Malvaceae | Gossypium hirsutum L. | Shrub; VU | Nigeria | Eto-ofo | Leaves | Juice from the crushed leaves is applied topically. | Sores, skin eruption, and wounds | [15] |

| Malvaceae | Sterculia tragacantha Lindl. | Tree; LC | Nigeria | Udot eto | Stem bark | Sap from the crushed stem bark is applied topically. | Boil, skin ulcers, and wounds | [15] |

| Malvaceae | Triumfetta cordifolia Guill., Perr. & A. Rich | Shrub; No Record | Nigeria | Nkibbe ubuk | Leaves | Juice from the crushed leaves is applied topically. | Skin spots | [15] |

| Marantaceae | Thaumatococcus danielli Benth | Herb; No Record | Nigeria | Ewe iran | Leaves | Powder from the dried leaves is mixed with oil and applied to the affected area. | Skin infections | [57] |

| Melastomataceae | Heterotis rotundifolia (Sm.) Jacq.-Fél. | Shrub; LC | Nigeria | Nyie ndan | Whole plant | Decoction of the whole plant is used externally for bathing. | Measles | [15] |

| Meliaceae | Azadirachta indica A. Juss. | Tree; LC | Ghana and Nigeria | Ibok utoenyin | Leaves, stem bark, root | Infusion is used topically. | Eczema, ringworm, skin spots, and scabies | [15,40] |

| Meliaceae | Carapa procera DC. | Tree; LC | Ghana, Guinea, and Nigeria | Mkpono ubom | Seeds | Oil from the crushed seed is used externally. | Burns, insect bites, and scabies | [40,58] |

| Meliaceae | Khaya grandifoliola A. Juss. | Tree; VU | Nigeria | Odala (Igbo), Oganwo (Yoruba) | Stem bark | Decoction is used topically. | Skin spots | [15] |

| Meliaceae | Pseudocedrela kotschyii (Schweinf.) Harms | Tree; LC | Togo | Helitétéwiyé | Root | Root maceration is taken orally. | Aphthous ulcers | [34] |

| Menispermaceae | Chasmanthera dependens Hochst | Climber; No Record | Republic of Benin | Boborou | Stem | Ground stem is applied topically or mixed with shea butter. | Wounds | [16] |

| Moraceae | Afromorus mesozygia (Stapf) E.M. Gardener | Tree; No Record | Cameroon | No record | Roots, stem, and leaves | No record. | Dermatitis | [26] |

| Moraceae | Artocarpus altilis (Parkinson) Fosberg | Tree; No Record | Cameroon | No record | Roots | No record. | Abscesses, boils, and skin infections | [26] |

| Moraceae | Ficus sycomorus L. | Tree; LC | Nigeria | Sikamo | Root | Poultice. | Snakebites | [15] |

| Moraceae | Ficus carica L. | Tree; LC | Nigeria | Ukimo | Stem bark | Dried stem bark is ground to powder and applied to the wounds. | Wounds | [15] |

| Moraceae | Ficus exasperata Vahl | Tree; LC | Nigeria and Togo | Ukuok (Akwa ibom); Eepin (Yoruba); Laalayou (Togo) | Leaves and root | Sap from the crushed root is used externally for ringworms in Nigeria. Decoction of the leaves is taken orally for aphthous ulcers in Togo. | Ringworm | [15,34] |

| Moraceae | Ficus ingens (Miq.) Miq | Shrub; LC | Republic of Benin | Dekuru sanni | Root bark | The root bark is ground to powder and applied topically. | Wounds | [16] |

| Moraceae | Ficus thonningii Blume | Tree; LC | Benin republic | Kudoro | Roots | Adventitious roots of F. thonningii and bark of the root of Newbouldia laevis are ground into powder and applied topically. | Wounds | [16] |

| Moraceae | Treculia obovoidea N.E.Br | Tree; LC | Cameron | No record | Twigs | No record. | Skin disease | [26] |

| Myristicaceae | Pycnanthus angolensis (Welw.) Warb. | Tree; LC | Cameroon | No record | Stem bark | No record. | Fungal skin infection | [26] |

| Myrtaceae | Eugenia uniflora L. | Tree; LC | Nigeria | No record | Leaves | Decoction of the leaves is taken orally. | Skin spots | [15] |

| Ochnaceae | Lophira lanceolata Tiegh. ex Keay | Tree; LC | Nigeria and Togo | Tabsomang (Togo) | Leaves, root bark and stem | Decoction of the leaves and root back for chickenpox, fungal skin infection, and wounds in Nigeria. Stem is rubbed directly on the herpes sore in Togo. | Chicken pox, herpes sores, and skin infections | [15,34] |

| Ochnaceae | Ochna rhizomatosa (Tiegh.) Keay | Shrub; No Record | Republic of Benin | Yinkpenoka | Root bark | The root bark is ground to powder and applied topically for wounds. | Wounds | [16] |

| Ochnaceae | Ochna schweinfurthii F. Hoffm. | Shrub; LC | Republic of Benin | Yinkpenoka | Root bark | The root bark is ground to powder and applied topically for wounds. | Wounds | [16] |

| Olacaceae | Coula edulis Baill. | Tree; LC | Cameron | No record | stem bark | No record. | Skin disease | [26] |

| Phyllanthaceae | Bridelia ferruginea Benth. | Tree; LC | Nigeria | Udia afua | Stem bark | Infusion is used topically. | Fungal skin infections and wounds | [15] |

| Phyllanthaceae | Flueggea virosa, (Roxb. ex Willd.) Royle | Shrub; LC | Republic of Benin | Opanko (Benin), Tchaakatchaka (Togo) | Root bark and aerial part | Root bark is incinerated and applied topically to wounds. Decoction is taken orally for aphthous ulcers. | Aphthous ulcers and wounds | [16,34] |

| Phyllanthaceae | Hymenocardia acida Tul. | Shrub; LC | Togo, Republic of Benin | KpaiKpai (Togo), Sinkakakou (Benin) | Leaves, Root bark | Decoction of the leaves is taken orally for aphthous ulcers. Root bark is ground to powder and applied topically to wounds. | Aphthous ulcers and wounds | [16,34] |

| Phyllanthaceae | Maesobotrya barteri (Baill.) Hutch | Tree; LC | Nigeria | Nnyanyatet | Root | Sap from the crushed root is applied externally. | Skin spots | [15] |

| Phyllanthaceae | Maesobotrya dusenii (Pax) Pax | Tree; No Record | Nigeria | Nnyanyatet | Root | Sap from the crushed root is applied externally. | Skin spots | [15] |

| Phyllanthaceae | Phyllanthus amarus Schumach. & Thonn. | Herb; No Record | Nigeria | Oyomokiso | Whole plant | Decoction of the whole plant is taken orally and for bathing. | Skin spots | [15] |

| Phyllanthaceae | Phyllanthus pentandrus Schum. And Thonn | Shrub; No Record | Nigeria | Ehin olobe | Leaves and fruit husks | The dried leaves are ground with Vigna plant, and the powder is then mixed with shea butter; the ointment is applied to boils. | Boil | [42] |

| Phyllanthaceae | Uapaca togoensis Pax | Tree; LC | Côte d’Ivoire | No record | Root and stem bark | Preparation from the root and stem bark. | Leprosy and skin diseases | [59] |

| Poaceae | Andropogon gayanus Kunth | Herb; No Record | Nigeria | Mbokko ekpo | Leaves | Dried leaves are ground to powder and used topically. | Wounds | [15] |

| Poaceae | Imperata cylindrica (L.) Raeusch. | Herb; LC | Nigeria | Ndan inwan | Rhizome | Rhuzome is crushed and applied topically. | Abscess and scorpion sting | [15] |

| Poaceae | Pennisetum polystachion (L.) Schult. | Herb; LC | Nigeria | Nwan-mbakara | Shoot | Dried shoots are ground into powder and applied to the wounds. | Wounds | [15] |

| Poaceae | Rottboellia cochinchinensis (Lour.) Clayton | Herb; No Record | Nigeria | Mbokko enan ikot | Whole plant | Decoction of the whole plant is for bathing. | Measles | [15] |

| Polygalaceae | Carpolobia lutea G. Don | Shrub; LC | Nigeria | Ikpafun | Leaves | Decoction of the leaves is taken orally. | Skin spots | [15] |

| Polygalaceae | Portulaca oleracea L. | Herb; LC | Ghana and Nigeria | Uton ekpu | Whole plant | Decoction of the whole plant is used for bathing. | Dermatitis and skin spots | [15] |

| Rubiaceae | Borreria verticillata (L.) G. Mey. | Herb; No Record | Nigeria | No record | Leaves | Juice from the crushed leaves is applied topically. | Eczema and skin spots | [15] |

| Rubiaceae | Chassalia kolly (Schumach.) Hepper | Shrub; No Record | Togo | Tiyah (Togo) | Roots | Paste made from the roots is applied topically. | Ringworm | [34] |

| Rubiaceae | Crossopteryx febrifuga (Afzel. ex G.Don) Bents | Tree; LC | Republic of Benin | Otoupedou | Root bark | The root bark is ground to powder and applied topically. | Wounds | [16] |

| Rubiaceae | Diodia sarmentosa Sw. | Climber; No Record | Nigeria | No record | Leaves | Decoction of leaves is used topically. | Skin spots | [15] |

| Rubiaceae | Gardenia ternifolia schumach. & Thonn | Shrub; LC | Republic of Benin and Togo | Keyabouaka (Benin); Kaou (Togo) | Root and root bark | Root decoction is applied topically for ringworms in Togo. Root bark is incinerated and mixed with palm kernel oil and used topically for wounds in Benin. | Ringworm and wounds | [16,34] |

| Rubiaceae | Morinda longiflora G. Don | Climber; No Record | Nigeria | No record | Leaves | Infusion of the leaves in water and used externally. | Scabies | [15] |

| Rubiaceae | Nauclea latifolia Sm. | Tree; LC | Nigeria | No record | Leaves | Juice from the crushed leaves is applied externally. | Rashes | [15] |

| Rubiaceae | Sarcocephalus latifolius (Sm.) E.A.Bruce. | Tree; No Record | Togo | Kayou (Togo) | Root | Decoction of the root is taken orally. | Aphthous ulcers | [34] |

| Rutaceae | Clausena anisata (Willd.) Hook. f. ex Benth. | Shrub; LC | Nigeria | Mbiet ekpene | Stem bark | Decoction of the stem bark is taken orally. | Measles | [15] |

| Rutaceae | Zanthoxylum gilletii (De Wild.) Waterman | Tree; LC | Ghana and Nigeria | Nkek | Root bark | Sap from the crushed root back is applied topically. | Boil | [15] |

| Rutaceae | Zanthoxylum zanthoxyloides (Lam.) Zepern. & Timler | Tree; LC | Togo | Kolgragu | Aerial part | Maceration is taken orally. | Aphthous ulcers | [34] |