1. Introduction

In recent years, substantial changes in land-use/land-cover (LU/LC) have taken place due to human activities [

1,

2]. LU/LC change linked to human factors, such as agricultural loss, overexploitation of forests, and urbanisation, has caused natural resource shortages, including widespread and permanent losses of biodiversity across the sphere [

3,

4]. Population growth continues to modify the landscape and natural lands through socio-ecological and socio-economic phenomena at extremely high rates, causing effects of LU/LC on ecosystem services [

5,

6,

7]. However, despite the increasing awareness that human well-being strongly depends on natural ecosystems [

8], many environments continue to face unprecedented stress that might result in their conversion and degradation, thus affecting the provisioning of ecosystem services for both present and future generations [

9]. Since the late 90s, ecosystem services have become a central issue for researchers and decision-makers, especially after the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment report [

10] addressed the gap between natural protection and human welfare [

11]. Although consequences of LU/LC changes have been studied at a global level, these studies have not captured critical LULC changes occurring at the basin scale [

12,

13] including Wami River Basin.

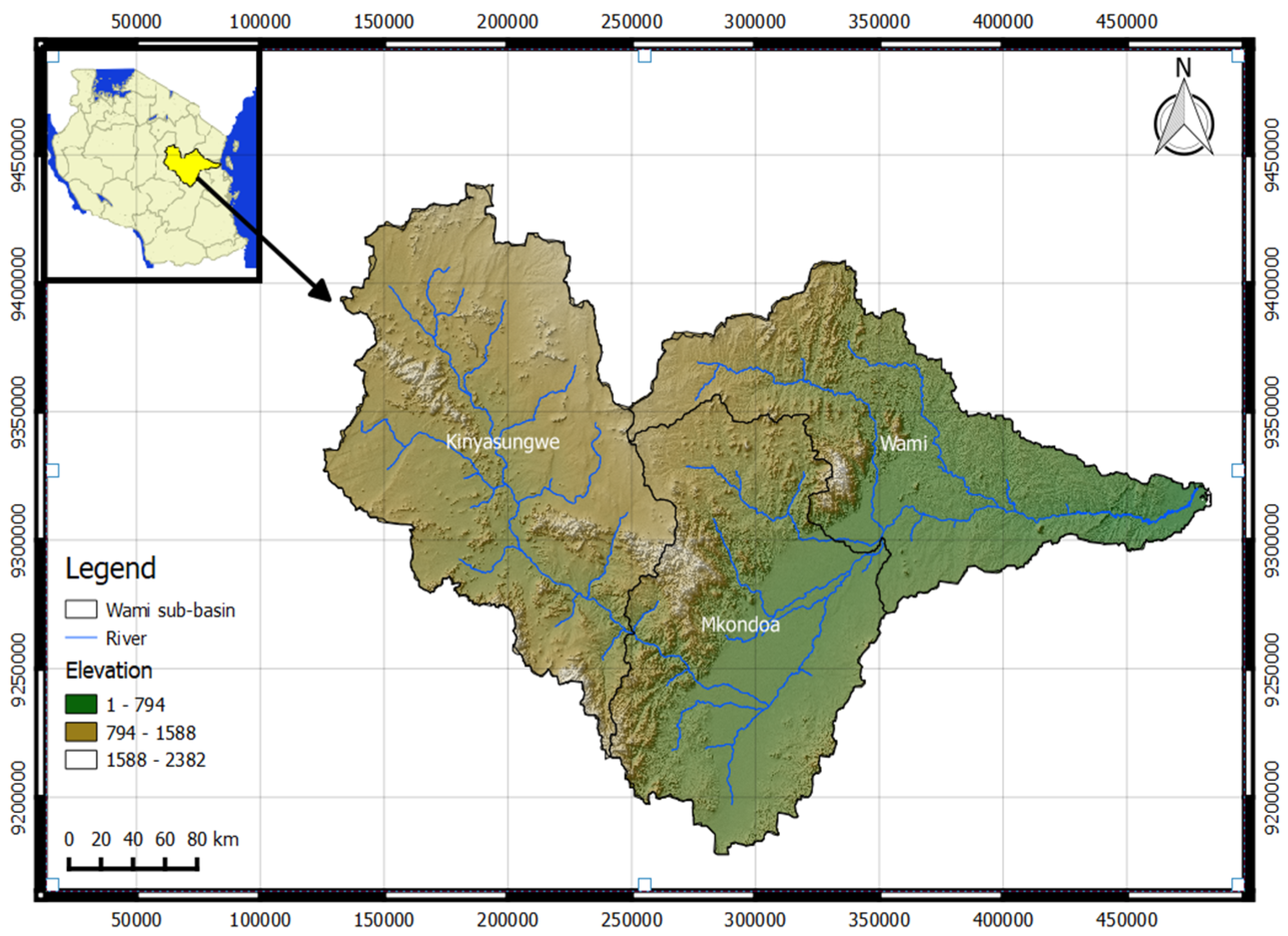

The Wami River Basin is a significant area, due to its different benefits to a diverse range of shareholders [

14], while LU/LC changes could be severe for the Wami river system, given its primary role in providing water, food and livelihoods [

15]. This change could cause several variations in services and roles, consequently causing degradation in provisioning ecosystem services from the natural resources of the Wami River Basin [

16]. As the population increases and consumption patterns vary, additional land will be needed for agricultural production and living space [

17]. The challenge facing society as a whole is deciding in what way to meet individuals’ growing demands for food, living space, fuel, and other supplies, while sustaining ecosystem services in LU/LC variations [

18,

19,

20]. Approximately 15 types of universal ecosystem services are declining, including water purification, erosion regulation and natural hazard regulation, and this trend could increase in the future [

10]. Ecosystem services benefit individuals, indirectly or directly, by providing goods, well-being, and growth of economic activities [

10,

21,

22]. The provision of water for domestic use has been an ecosystem service that can be directly associated with increasing population, in that the water supply has been steadily decreasing [

23].

Since the mid-20th century, human activities have altered ecosystems in substantial ways [

10], and water stress has increased due to water pollution, withdrawal, and contamination [

24,

25,

26]. LU/LC changes are regarded as the dominant form of anthropogenic stress on the environment [

27], causing changes in ecosystem service patterns affecting the water supply [

10,

28,

29]. Sustainable land management plans could ensure the constant provision of ecosystem services. Studies have showed that the effects of LU/LC on ecosystem services differ temporally and spatially [

22,

30,

31,

32,

33]. Water supply services are susceptible since they are exposed to severe natural stresses related to interactions among biophysical factors, which considerably increase their heterogeneity from a temporal and spatial perspective [

34,

35]. Several relatively static influences (soil, topography, and geology) and dynamic influences (land use, land management, and climate) interact to control water access and how it will be distributed to competing users [

23]. The presence of human activities’ pressure makes these services more vulnerable, leading to extreme variation in the frequency of accessibility [

36]. Water yield is challenging to value and measure, but there is a need to account for the changing availability of water from the basin across various spatial scales and throughout long-time perspectives, to guarantee sustainable usage [

23,

37,

38,

39].

Water ecosystem services for drinking are intensely affected by the amount and quality of water delivered to the basin, and how it is divided between the processes of surface water runoff, evaporation, groundwater recharge, and transpiration [

40]. Therefore, understanding the consequences of LU/LC on the water ecosystem services for drinking is vital for understanding the significance of decisions and policies, and might support the development of appropriate plans [

38]. Further, land use management and plan assessment requires in-depth information about the different effects on ecosystem services [

41,

42]. Therefore, this study uses the spatial econometrics approach to analyse the impact of LU/LC change on water ecosystem services for domestic use in the Wami River Basin, in order to provide relevant policy recommendations related to water supply services.

4. Discussion

The evidence shows that community water supplies in rural areas in developing countries, such as in Africa, are mostly insufficient and unreliable given the rate of population growth [

48,

49,

50]. Safe and clean drinking water is one of the most vital needs of life [

51]. Presently, water shortages affect approximately 40% of people across the world, and by 2030, the overall demand for water is estimated to increase by 50% [

52]. Challenges in the water sector are linked with population increase, climate change, and LU/LC change, resulting in shortages of various societal needs, including the supply of safe drinking water [

53]. Global trends such as LU/LC change pose severe challenges to resource management [

54], including of water. Such changes are disturbing in the light of growing insecurities and pressures around managing resources [

55]. Increasing human activities across the world are causing significant modification of the land surface, which has a severe effect on the functioning of global systems [

1]. The effects include land degradation [

56], impacts on hydrological cycles [

57,

58,

59], and a decline in ecosystem services [

60], including water for domestic use. LU/LC change is a worldwide phenomenon, which will continue to cause increased demand for water resources and their associated ecosystem services, particularly for drinking water [

60]. While several researchers have observed how water resources are becoming strained due to LU/LC change, none have researched how water ecosystem services are affected.

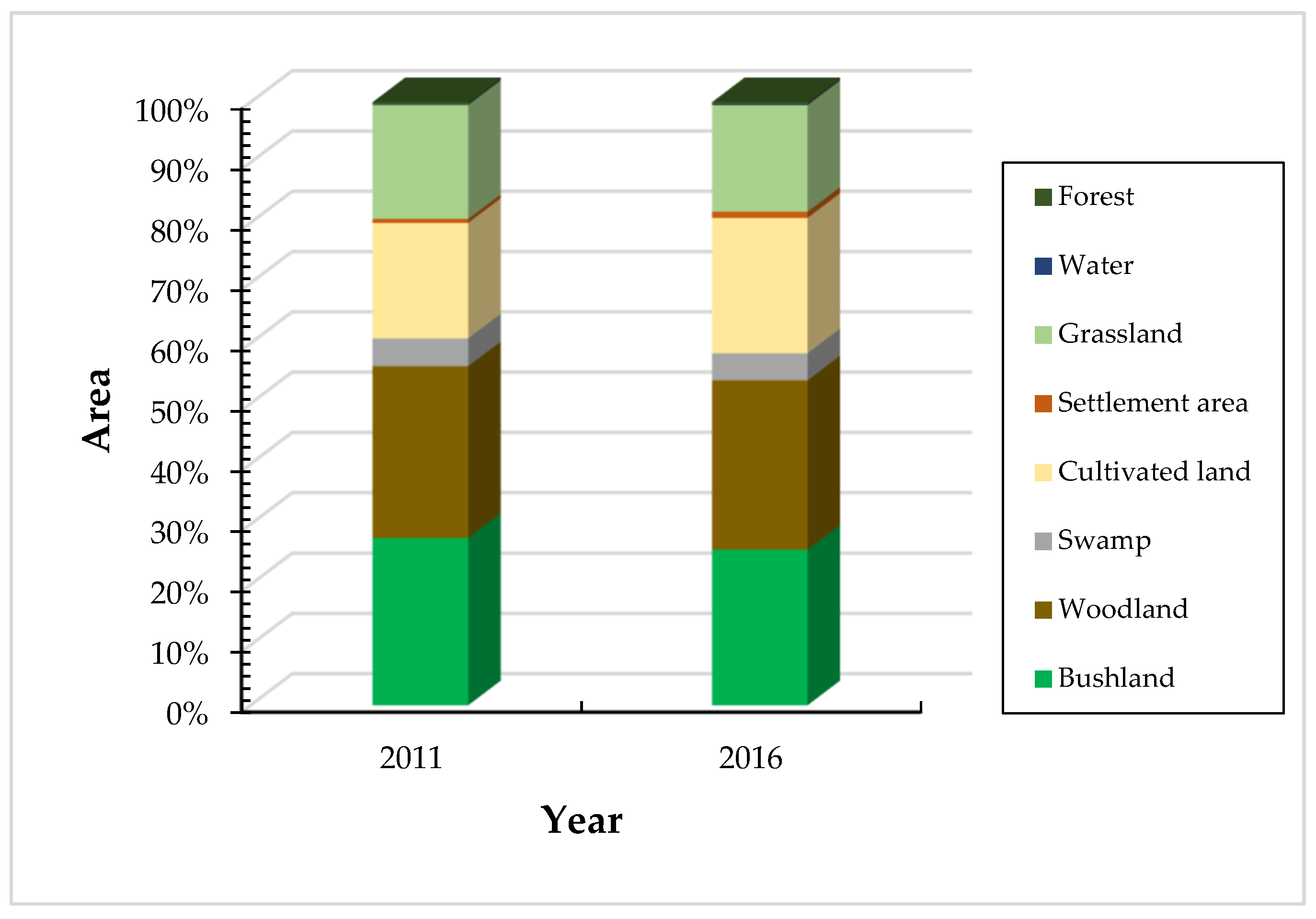

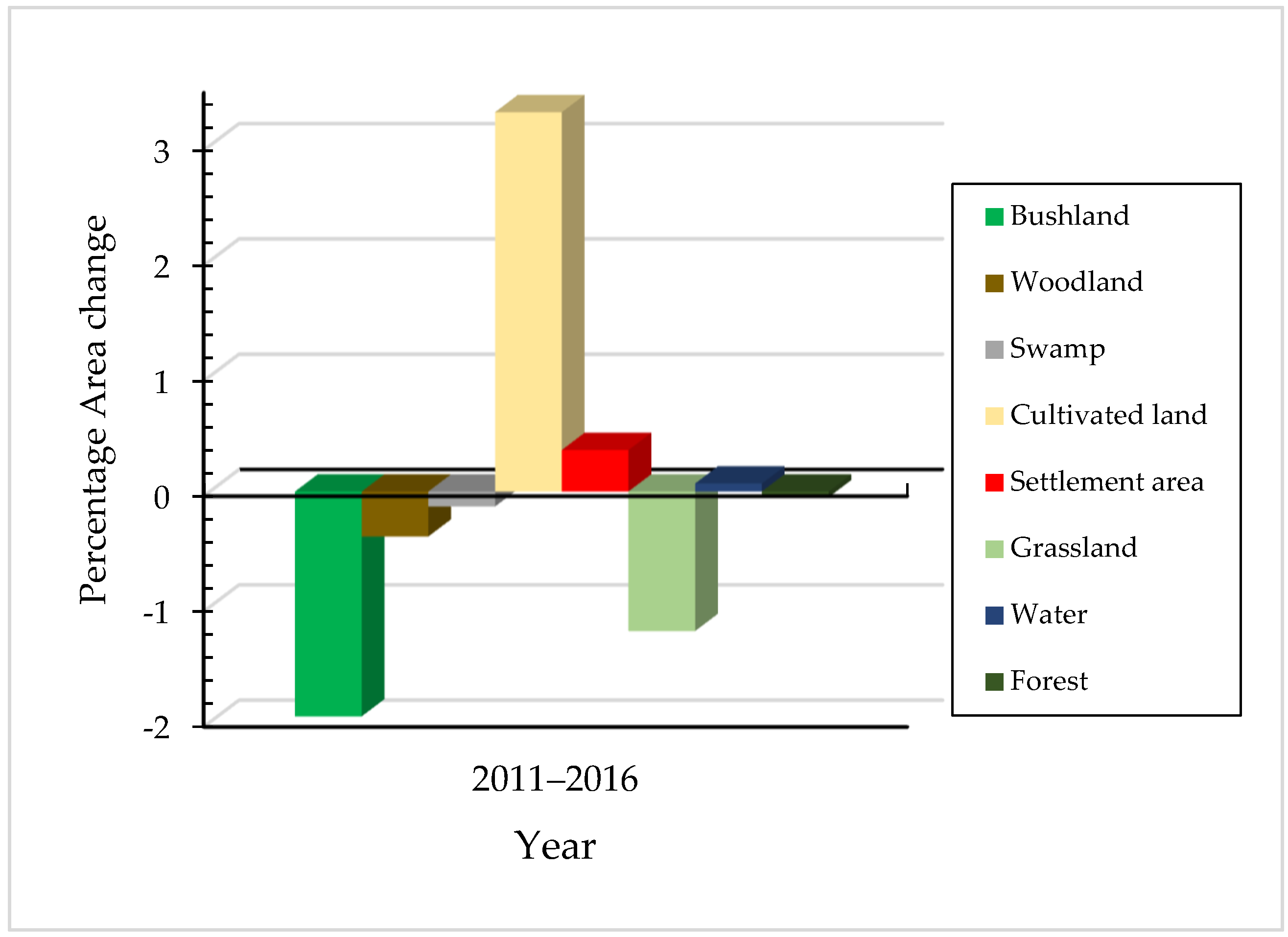

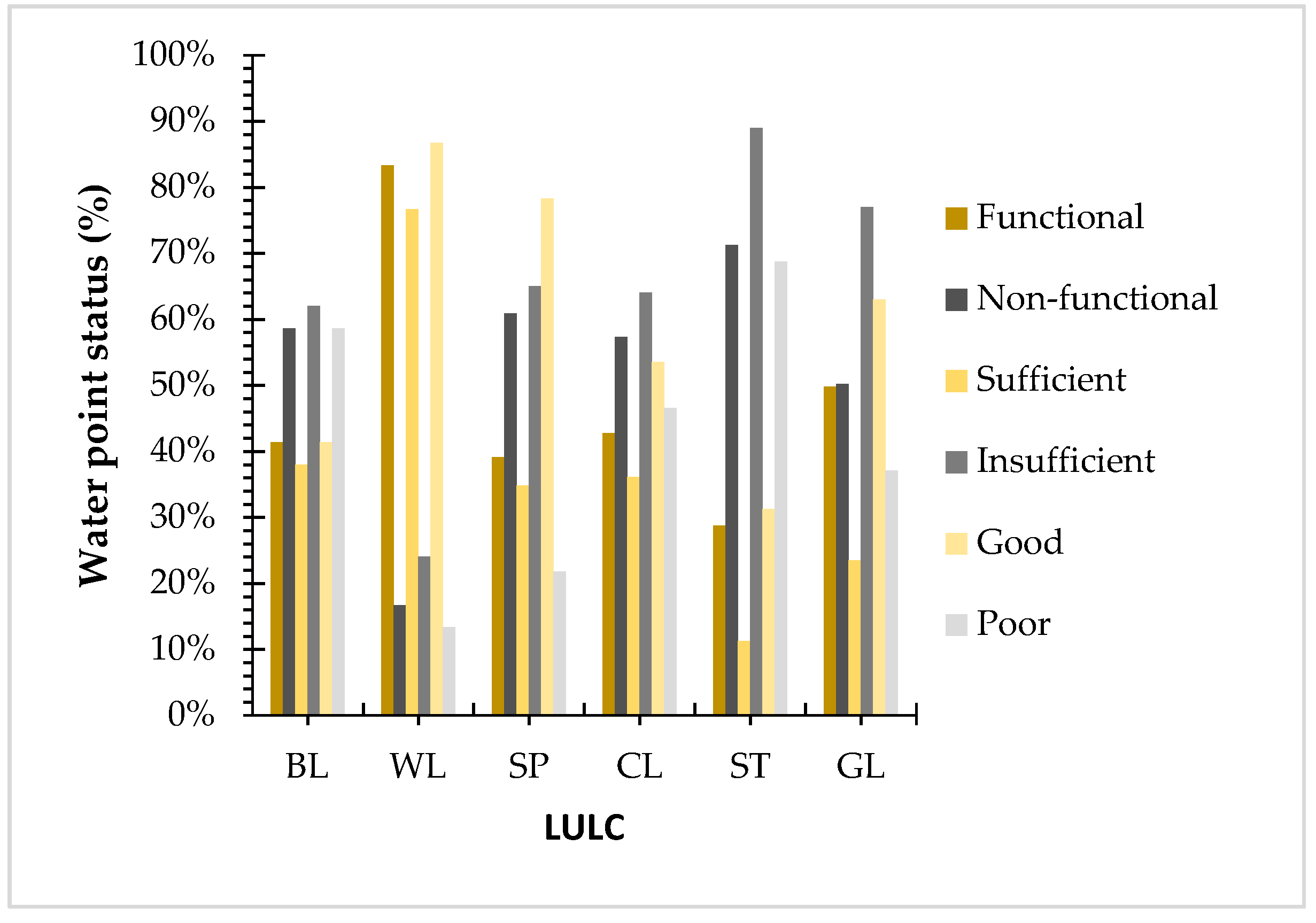

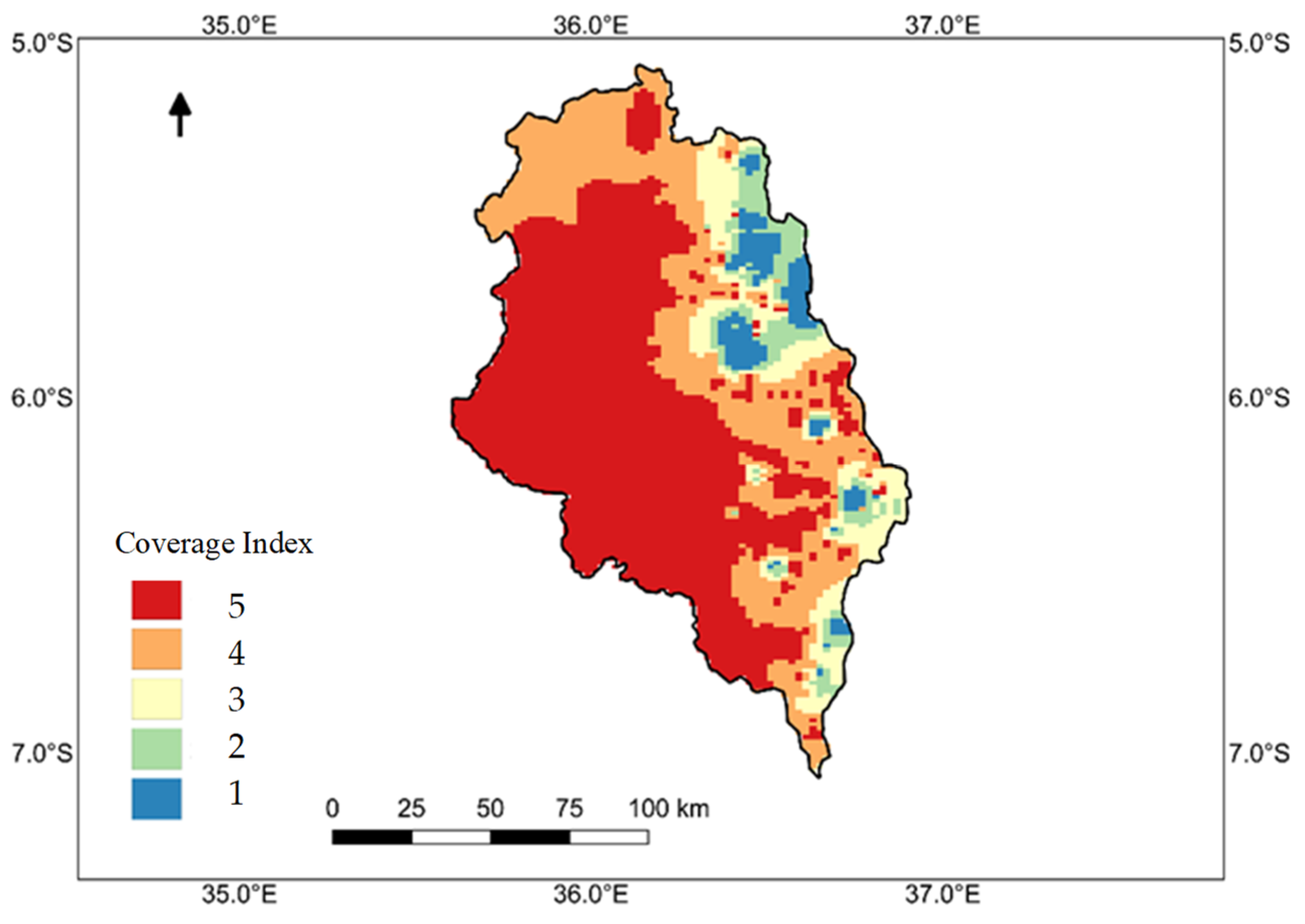

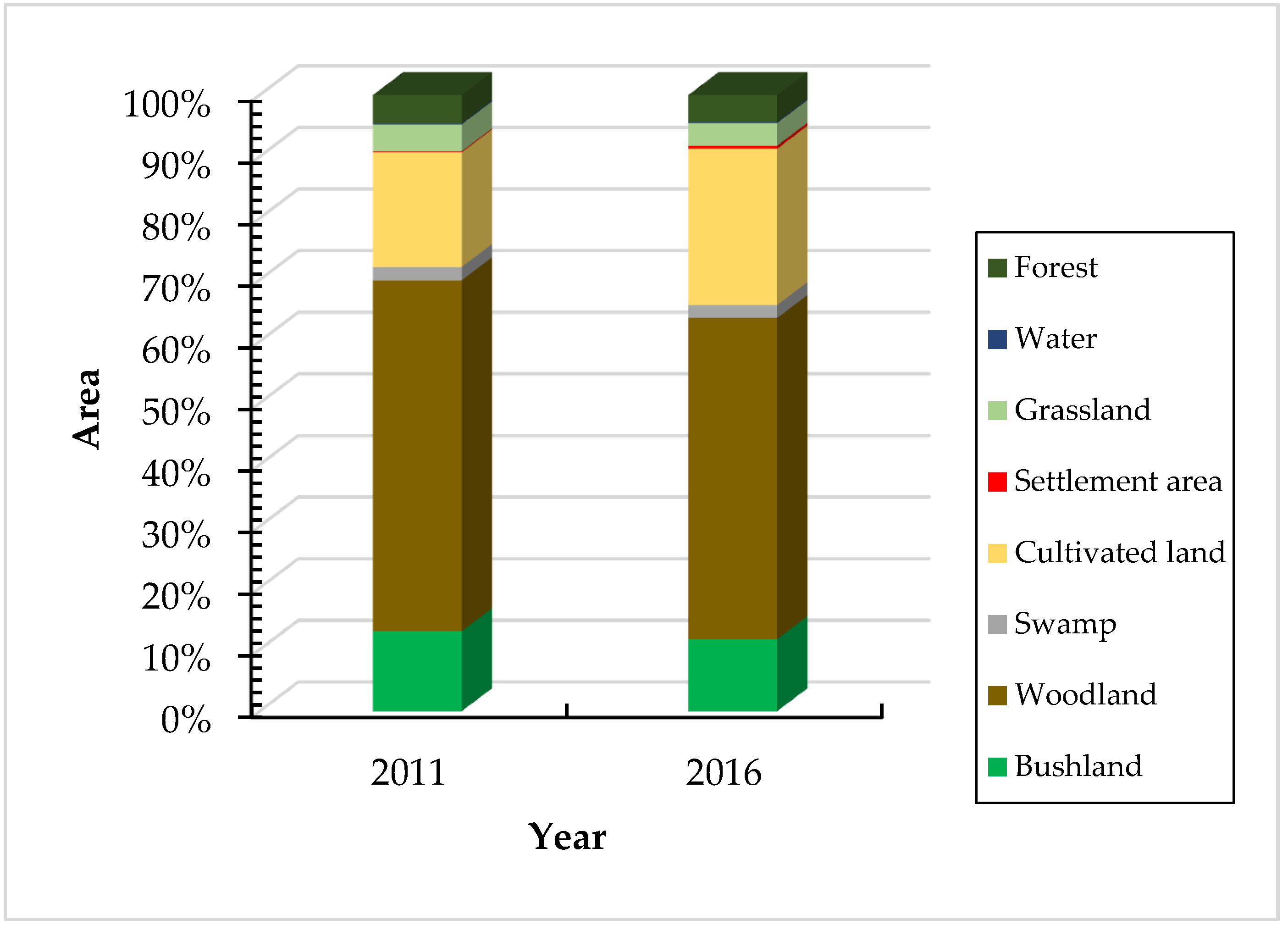

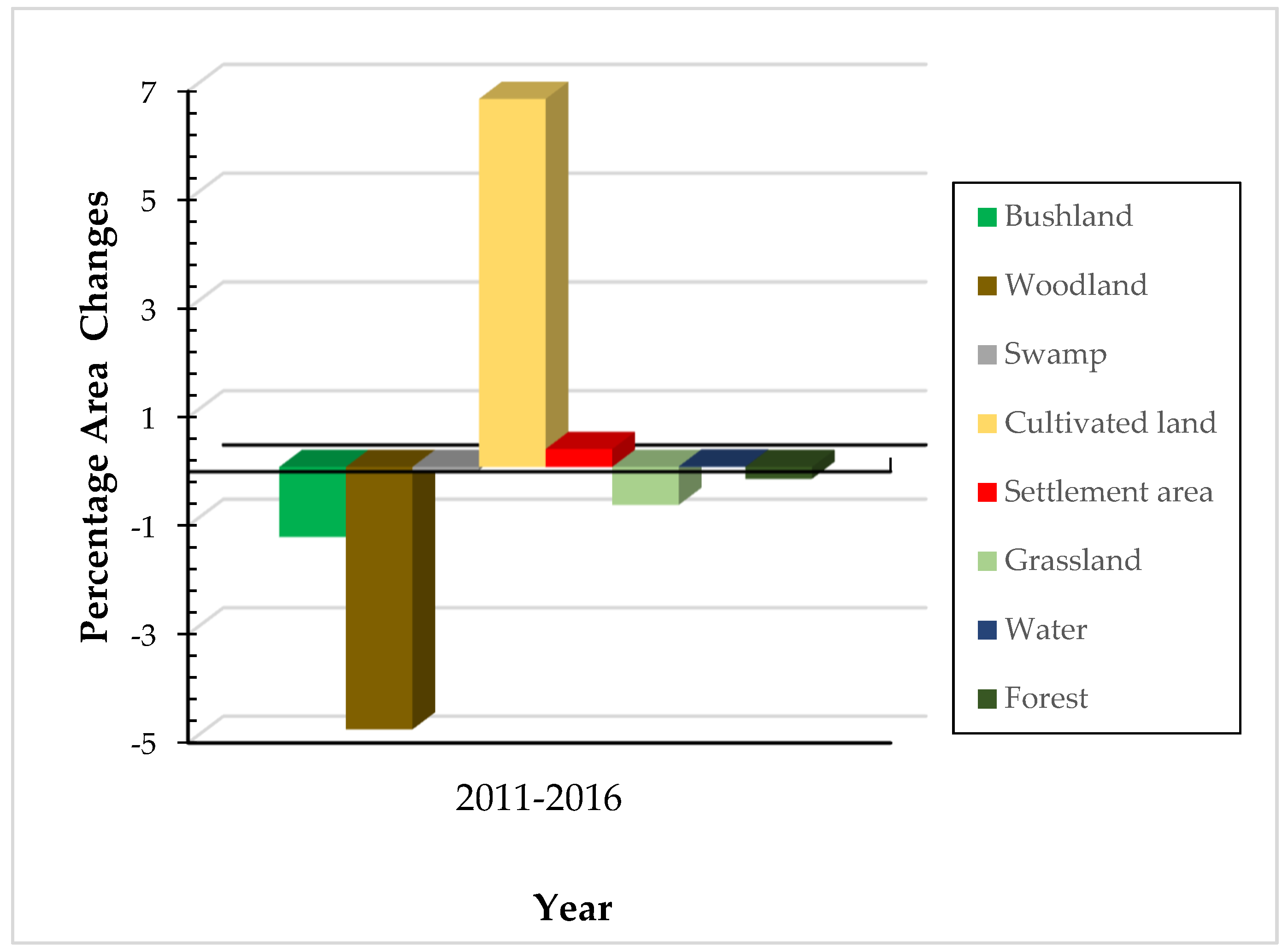

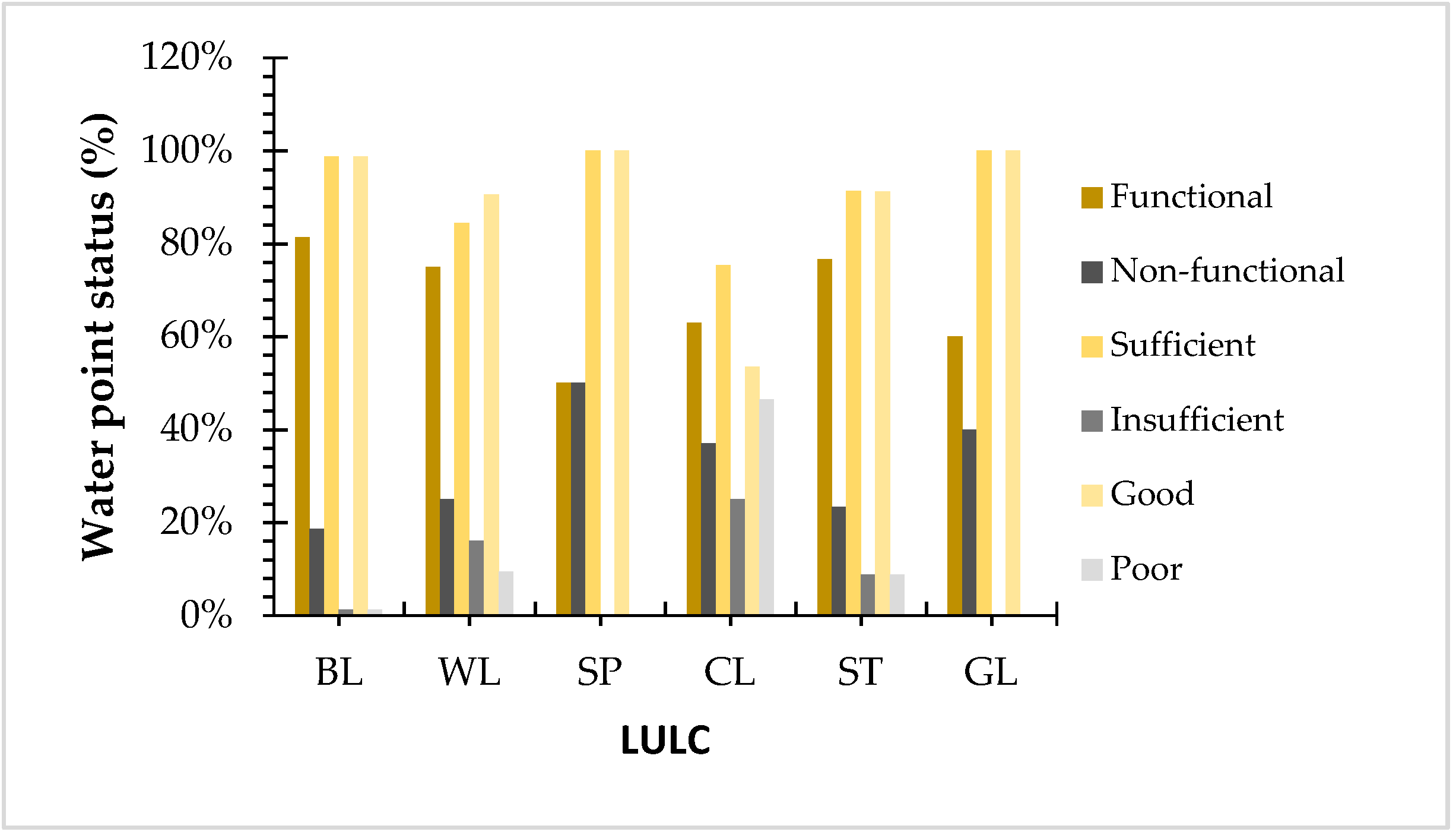

Using the spatial econometric technique, we analysed the impact of LU/LC changes on water ecosystem services for domestic use in the Wami River Basin. The LU/LC changes both upstream and downstream of the basin have already been presented. The findings during the study period (2011–2016) on different classes revealed that cultivated land showed maximum positive changes in both sub-catchments, while bushland and woodland showed maximum negative changes in the Kinyasungwe sub-catchment and Wami sub-catchment, respectively. The results showed that bushland, woodland, cultivated land, and grassland were significantly correlated with water point characteristics in both sub-catchments. For functionality characteristics, a significant effect was observed for bushland and grassland in the Kinyasungwe sub-catchment and Wami sub-catchment, respectively, while sufficient water was found at the water points for woodland (Kinyasungwe sub-catchment) and grassland (Wami sub-catchment). Furthermore, the results showed that bushland had a significant amount of water points of poor quality at the Kinyasungwe sub-catchment, while a significant number of water points of good quality were found in grassland of the Wami sub-catchment.

Population growth and economic development have led to changes in LU/LC worldwide, while ecosystems services are continuously threatened by human activities and stand to be further affected [

2,

61,

62]. Resulting changes can have positive consequences such as increased vulnerability, resulting in a decreased supply of ecosystem services including water availability and quality, especially in arid and semiarid regions [

61]. With the rapid expansion of LU/LC, ecosystem services for drinking water will continue to be affected [

63,

64]. It is critical to research the typologies of water points and role of LU/LC changes in influencing water supply services [

65,

66]. Numerous concerns exist today in areas where demands on land and water ecosystem services can be high due to natural degradation from agriculture and settlement expansion [

67]. The loss of ecosystem services such as drinking water due to natural resource reduction are not native phenomena, but rather a collective universal issue [

68]. A number of studies have been performed worldwide showing that natural resources are decreasing, leading to losses of ecosystem services; namely, the supporting, regulating, and provisioning of services [

57,

69]. In future, the loss of ecosystem services due to unforeseen LU/LC change is expected to continue, especially in poor countries, and this will affect land and water resources, which provide a lot of ecosystem services [

70].

Water shortages and pollution are all signs of stress, especially in rural areas which have difficult interactions with the natural water cycle [

71]. To reduce the damage to ecosystem services for drinking water around the basin, it is critical to identify land uses which are highly vulnerable to human activities [

72]. The relative influence of the different LU/LC changes on water provisioning services and water supply is based on the LU/LC patterns affecting annual water available for drinking [

63,

73]. The impacts of cumulative pressures on ecosystems may not be observed for many years, until threshold point is reached, which activates rapid or permanent changes [

74]. This will impact the supply of ecosystem services that are essential for human well-beings including provision of drinking water [

75]. In order to more effectively manage ecosystem services, there is a need to understand how incremental impacts on biodiversity and ecosystems affect the goods and services they provide [

76]. In this context, efficient and protection-oriented plans and policies should be adopted for sustainable land and water resource development in the basin.

5. Conclusions

Our aim in this study was to analyse the impacts of LU/LC change on water ecosystem services for domestic use in the Wami River Basin. We found that the LU/LC changes and water point characteristic correlations are all statistically significant. We have also shown that different LU/LCs can affect drinking water services, with a likely drop in service coverage. Our study confirms the influence of LU/LC change on water point functionality, water quantity and water quality, and, therefore, we conclude that LU/LC change affects water ecosystems for drinking water in the basin. These findings point to an inherent reduction of natural resources, resulting from increasing agriculture and urbanization, and explain natural resource decreases in the Wami River Basin. Hence, they support initiation of dialogue on policies at the national level that could emphasise either land-use and water resource choices, or motivations that could potentially be used by the community regarding natural resource protection. A very strong argument exists in these cases to develop a nexus of land and water resource systems for environmental protection, including decreasing or preventing impacts. However, such an act may be challenged if the relationships between land, water and other sectors have not been clearly determined due to a lack of data. This critical problem alarms stakeholders in land and water resources in terms of the implementation of a resource nexus system that takes other sectors into account. The demand for sustainability, accountability, and incentives for rural water supply services may evidently arise. For example, compensation schemes and data on the water supply can be developed if a well-defined link can be established between land use management and the water supply, both at economic and hydrological intensities. Furthermore, for the sustainability of rural water supply services, we suggest numerous policy effects to optimize resource management in the basin. First, the authority should make use of the Water Point Mapping System to establish inter-sectorial cooperation mechanisms, reinforce temporal and spatial data availability in the basin, and build specific standard bases for services. This will help to increase water ecosystem service benefits, while reducing the spatial and temporal effects of LU/LC change and other factors. Second, other factors such as operation and maintenance, technology, financing, and management of water points determine the standards of the services. Thus, construction of new water points must be based on a researched evaluation of suitability, as well as the management capacity of an area. At the same time, proper land management in the basin could prevent impacts on the environmental ecosystem and reduce challenges to water ecosystem services.