Abstract

The governance of extractive industries has become increasingly globalized. International conventions and multi-stakeholder institutions set out rules and standards on a range of issues, such as environmental protection, human rights, and Indigenous rights. Companies’ compliance with these global rules may minimize risks for investors and shareholders, while offering people at sites of extraction more leverage. Although the Russian state retains a significant stake in the oil and gas industries, Russian oil and gas companies have globalized as well, receiving foreign investment, participating in global supply chains, and signing on to global agreements. We investigate how this global engagement has affected Nenets Indigenous communities in Yamal, an oil- and gas-rich region in the Russian Arctic, by analyzing Indigenous protests and benefit-sharing arrangements. Contrary to expectations, we find that Nenets Indigenous communities have not been empowered by international governance measures, and also struggle to use domestic laws to resolve problems. In Russia, the state continues to play a significant role in determining outcomes for Indigenous communities, in part by working with Indigenous associations that are state allies. We conclude that governance generating networks in the region are under-developed.

1. Introduction

The governance of extractive industries has become increasingly globalized, with authority shifting from the state to both the international and local scales, through processes of “glocalization” [1,2]. Although the 1962 UN General Assembly resolution on “Permanent Sovereignty over Natural Resources” enshrines every state’s sovereign rights on its territory “freely to dispose of its natural wealth and resources in accordance with its national interests”, and “respect for the economic independence of States, in practice different systems of property rights and licensing, and global supply chains create a variety of opportunities for citizens to influence extraction and revenues from natural resources. At the international scale, the tools for governing the extractive sector have become increasingly complex, as states sign international conventions and multi-stakeholder institutions set out rules and standards on a range of issues, such as environmental protection and human and Indigenous rights [3]. Companies’ compliance with multiple global rules may minimize risks for investors and shareholders [4,5], while offering people at sites of extraction more leverage. Pressure and resources at the international scale allow civil society largely to bypass the nation-state, addressing their concerns to intergovernmental or nongovernmental actors, whom they can now more easily contact via the Internet, which has also facilitated networking among social movement organizations and activists [6,7,8]. Meanwhile, this rapid transfer of information has allowed the environmental and social performance of oil and gas companies to come under increased scrutiny for their negative environmental impacts, as well as for seizures of land from Indigenous peoples and violations of their rights [9,10].

A particularly salient example of the intertwining of environmental and human rights issues is the Russian Arctic. As the fragile environment of the Arctic is affected by extraction, the rights of local residents, especially traditional reindeer herders, are under threat. However, identifying paths for resolving these issues through the governance of the oil and gas industry is particularly challenging in the Russian context. In Russia, land is owned by the state, and may be leased to companies and other users. Indigenous people often do not have property rights to their traditional territories, although many oil and gas companies voluntarily adopt international conventions related to the rights of Indigenous people. In the Russian Arctic, the growth of extractive industries also has set off conflicts over industrial development and revenue-sharing from the oil and gas sector. Oil exploration, extraction, and transport have severe impacts on the environment and livelihoods of Indigenous peoples, including degradation of land and water from oil spills, the loss of pasture land, and the fragmentation of territory used for reindeer herding and hunting [11,12,13,14]. In some cases, Indigenous communities and associations, as well as other non-governmental organizations (NGOs), have resisted industrial development, occasionally using tactics that extend to the global level and place pressure on financial lending institutions, such as during the “Green Wave” campaign against the expansion of oil development in Sakhalin in the Russian Far East [15].

To avoid these problems and the negative publicity they entail, international financial institutions and investors have developed a host of guidelines and standards to ensure the protection of Indigenous peoples’ rights to traditional natural resource use and to require benefit sharing by companies in the extractive sector in the form of social investment, development plans for Indigenous communities, or, at a minimum, compensation for damage to traditional livelihoods [16,17,18]. These requirements are one element of the globalization of corporate governance. However, due to significant levels of state ownership and investment by the Russian government, as well as the dependence of many countries on Russian oil exports, Russian companies are less sensitive to the opinions of transnational stakeholders, and therefore, less vulnerable to reputational risks outside the country and to pressure from transnational organizations and social movements [19,20,21]. However, continued globalization may be changing the status quo in Russia’s oil and gas sector [22]. To examine this issue in detail, we focus on the Yamal peninsula, a site of rapidly expanding oil and gas development in the midst of a significant Indigenous population.

2. Materials and Methods

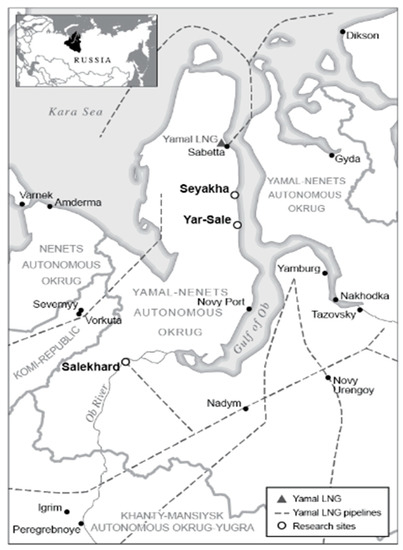

Data for this study were collected using qualitative methodologies [23]. The collection and analysis of materials were carried out in 2017–2019. The primary research strategy was the case study method based upon a detailed and comprehensive study of Yamalo-Nenets Autonomous Okrug (YaNAO), or Yamal (Figure 1) Yamal is a strategically important region for the development of the Russian oil industry, and a number of major Russian oil and gas corporations operate in Yamal. At the same time, Yamal is home to a large number of Indigenous people, many leading a traditional way of life. Intensive industrial development of the region has led to negative consequences for Indigenous people, whose well-being depends on the quality of the environment [24,25]. This case study allows us to consider the interactions among the state, oil and gas corporations, and Indigenous peoples in the context of the globalizing extractives sector. Processes of globalization are penetrating YaNAO; markers of globalization include the spread of global environmental and social standards that shape industrial activities and relations with foreign investors. However, the state remains committed to its role in controlling oil extraction and civic activity in the region. Thus, this case study allows us to analyze the key characteristics of interactions between global trends and state control in the field of natural resource management.

Figure 1.

Map of Yamal-Nenets Autonomous Okrug with research sites.

The main research methods included semi-structured interviews (Appendix A: Table A1), document analysis, and participant observation. Interviews were conducted with representatives of local and regional authorities, experts based in scientific institutes and NGOs, and local residents, including members of reindeer herding communities and employees of reindeer herding enterprises. In total, 23 interviews were conducted. Interview questions focused on the following issues: The impacts of the oil and gas industry on the lives of local residents, mechanisms of interaction with the government and companies, government programs to support Indigenous people, and companies’ engagements with Indigenous people. The interviews were transcribed and analyzed by the method of axial coding. In addition to interviews, observations were made in Indigenous settlements located in regions of oil and gas development. Document analysis also informs this study. The following documents were analyzed: Global standards related to the interaction of oil and gas companies and Indigenous peoples; state legislation defining the rules of interaction between companies and Indigenous people; and corporate reports describing the forms of interaction. The data obtained from different sources were compared, allowing for triangulation of the collected materials. The collected data helped to identify the features of interaction between oil and gas companies, Indigenous people, and state authorities.

3. The Globalization of Governance in the Oil and Gas Sector: The Theoretical Approach

As the rules and standards that govern the oil and gas sector have shifted from state-based government to global governance, including private efforts, such as the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (EITI) and the requirements of international financial institutions, there is an expectation that the state would be just one of many actors shaping company behavior. Governance may occur at many scales and involve many different actors; rules and standards are developing in a variety of institutional venues. Although they are not easily enforceable, global rules and standards often surpass state-based legal requirements for environmental protection and community consultation. For example, Indigenous rights may be more clearly codified at the international level than in domestic law. One would expect that global governance would then offer Indigenous communities greater leverage to address rights violations than domestic legal systems.

The globalization of governance in the extractive sector is manifested in several trends: The increasing dependence of extractive companies on international financial institutions; the development of global environmental and social standards; the involvement of non-state actors (corporations and NGOs) in shaping governance; and the institutionalization of global standards at the local level [26,27,28,29]. As the governance of natural resources has globalized, it has grown to encompass a range of regulatory and standard development institutions, such as the United Nations, notably through the International Labor Organization (ILO) convention, the Arctic Council, Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) Guidelines, and the Responsible Care Initiative, among others. Multi-stakeholder initiatives like the Global Reporting Initiative, the Voluntary Principles on Security and Human Rights, Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (EITI), and others foster transparency by encouraging companies to monitor and report social and environmental impacts [29,30,31]. In addition, companies may participate in voluntary environmental management certification schemes, such as International Organization for Standardization-14000 (ISO 14000), Occupational health and safety management systems-18000 (OHSAS-18000), the European Union Eco-Management and Audit Scheme (EMAS), and so forth. Some global standards specifically focus on the protection of Indigenous people’s rights, such as ILO Convention No.169 and World Bank Operational Directive 4.20 on Indigenous people.

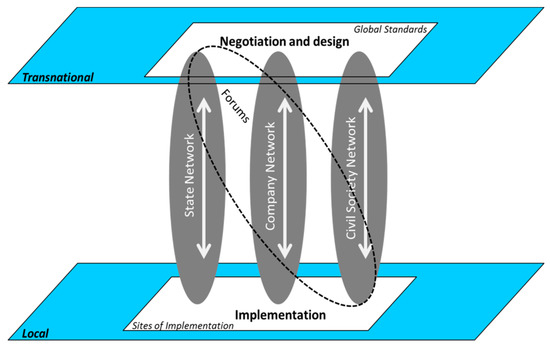

This article uses the concept of governance generating networks (GGN) to understand how extractive industries may be governed by multiple actors operating across different scales [32,33,34,35,36]. The GGN in this study is the oil production network, including companies, investment banks, equity partners, international and local offices, as well as state agencies at different levels and civil society actors (NGOs and Indigenous peoples’ associations). Interactions among actors from the state, the private sector, and civil society in these networks link the transnational level and the local level. The main components of the GGN are (i) the transnational nodes of global governance design, (ii) the forums of negotiation, and (iii) sites of implementation.

In the transnational nodes of global governance design (see Figure 2), global institutions like the United Nations (UN), the Arctic Council (AC), the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the International Financial Corporation (IFC), the World Bank (WB), and the Extractive Industry Transparency Initiative (EITI), and other environmental management certification schemes develop new regulatory global standards, such as guidelines for oil companies to ensure the sustainability of oil production and the protection of Indigenous people’s rights.

Figure 2.

Governance of oil production network.

Governance decisions are not only made in the nodes of design, but also in “forums of negotiation” and “sites of implementation” [33]. Forums of negotiations can involve both global and local actors, can take the form of global conferences and meetings (for example, in the Arctic Council or its Sustainable Development working group, involving Indigenous people as permanent participants), and can occur at the national, regional or local level. The local forums can take place at public hearings, or extend from bottom-up resistance movements by local actors who appeal to global institutions.

Sites of implementation are geographic territories where governance arrangements are implemented and adapted to local circumstances. In the context of oil production, key sites of implementation are the places of oil exploration, extraction, and transportation. In these sites, local stakeholders, and especially Indigenous people, experience the impact of oil development. These sites of implementation are connected to the transnational level by networks of state, market and civil society actors, interacting and negotiating over the development of global policies and standards, and the implementation of these standards in the management of oil companies.

GGNs link transnational spaces with the “space of places”, a term coined by Manuel Castells [6]. These connections can be established in different ways. In well-developed GGNs, the network includes civil society actors operating in the local space of places participating in the network from the bottom up. They may participate in NGO-led market campaigns to change corporate practices by highlighting grievances about the local activities of transnational corporations. A GGN also involves actors operating in transnational spaces with the aim of fostering, from the top down, institutional changes in specific localities by imposing sets of new rules and standards to be implemented locally. These actors may collaborate on new rules issued by transnational actors and institutions, such as the investors and equity partners who fund extraction. Oil companies may voluntarily adopt certain global standards to increase their competitiveness in the market, attract financial support, and comply with the requirements of financial institutions that provide loans or investment. Ideally, GGNs facilitate constant interaction and information exchange among local and transnational actors, with the ultimate goal of encouraging sustainable development in the specific localities. This type of robust GGN has been observed in the forest sector [33]. New modes of global governance and decision-making are crafted and recrafted to adapt to the globalization of oil production.

In this way, companies in the extractive sector may go beyond the requirements of national legislation by adopting and implementing global standards. Oil and gas companies adopt global standards to avoid reputational risks, satisfy their shareholders, limit pressure from NGOs and Indigenous organizations, and most importantly, to ensure future investment. For instance, private Russian oil companies seek loans from international lending institutions, such as the IMF, World Bank, or the European Bank of Reconstruction and Development (EBRD) and also need to maintain good relations with equity partners. These banks and partners have crafted lending requirements that are based on the global conventions and rules described above. This results in the institutionalization of global rules in concrete practices in places of oil exploration, extraction and transportation. The companies also respond to the interests and demands of shareholders by developing their own corporate codes of conduct and corporate social responsibility policies.

Scholars have argued that the role of the state in governing the oil and gas industry is changing, due to globalization and oil production supply chains that stretch across borders [37]. In a well-developed GGN, companies go beyond a given state’s legal requirements for operation, instead of maintaining the often stricter or more expansive standards from the global nodes of design. Cumulatively, these rules and standards encourage companies to pursue what has been referred to as a “social license to operate” (SLO) in order to further avoid risks and minimize conflicts [38,39]. SLO assumes that in addition to meeting legal requirements by obtaining licenses and permits, companies have to receive social acceptance and approval from society [40,41]. SLO helps companies to avoid conflicts with interested and affected stakeholders from civil society. Negotiated benefit sharing arrangements, both formal and informal, can effectively contribute to SLO [42,43,44]. The need to obtain SLO potentially may strengthen non-state actors’ influence over rules and standards and may change the role of the state in oil governance. However, it is not clear to what degree the state’s governance role has been supplemented by SLO and whether the need for social licensing and benefit sharing, in fact, shape the governance of oil and gas companies at specific sites of extraction [45,46].

Ultimately, companies may need to exceed basic legal compliance to ensure smooth operations at sites of extraction. However, at the same time, in Russia, major petroleum companies, such as Gazprom and Rosneft are owned or co-owned by the Russian state. As a result, they do not seek loans from global financial institutions and instead receive investment money from the Russian government. Moreover, oil and gas are strategic commodities for the Russian government in its effort to ensure economic development. Thus, in Russia, state-led governance may persist as more influential than transnational governance efforts.

4. Results: Indigenous People and Oil and Gas Extraction in the Yamal Peninsula

The sustainability of local communities in the Russian Arctic has become an urgent issue amid intensive industrial development, global climate change, and broader social transformation. Global warming has affected migration routes and the economic strategies of reindeer herders [47]. Intensive oil and gas development in the Arctic has led to environmental pollution, a decrease in wildlife populations, changes in animal migration routes, and a decline in freshwater fish populations [48]. These changes, in turn, have had an adverse impact on the traditional activities of local residents, such as hunting and fishing. Moreover, the expansion of oil development is associated with the seizure of some land used by local residents [49]. These challenges are present in Russia’s Yamal peninsula, home to members of several Indigenous groups.

The Yamal Peninsula, located in the Russian Arctic, is part of the Yamalo-Nenets Autonomous Okrug (YaNAO), a federal administrative unit in the Tyumen Oblast. Most of Yamal’s territory is located above the Arctic Circle and covered by tundra. Oil and gas deposits are concentrated in the Tazovsky and Yamalsky districts of YaNAO. Gas reserves in Yamal account for about 70% of all Russian gas reserves. In 2018, YaNAO produced 433.5 billion m3 of natural gas, approximately 80% of all Russian gas and 20% of global gas production. Gas production is carried out by 39 enterprises at 98 fields, operated by large corporations, including Gazprom, Rosneft, and Novatek. Gazprom produces 75.9% and Novatek 14.5% of all gas in YaNAO. Oil reserves in YaNAO account for about 14.5% of all Russian oil reserves. In 2018 the okrug produced 23.9 million tons of oil, approximately 9% of all Russian oil production. Oil production is carried out by 25 enterprises at 72 fields in YaNAO. The main oil-producing enterprises in the okrug are Gazprom Neft (62%), Rosneft (15.5%) and Novatek (15%) [50]. The Yamal regional government is heavily dependent on oil and gas revenues for its budget. Natural resource extraction accounts for approximately 50% of the regional GDP, not counting associated construction and transportation industries, while agriculture, hunting and forestry are just 0.1–0.2% of GDP [51]. In recent years, the YaNAO regional economy has grown much more quickly than the Russian average [52,53]. In addition, oil and gas companies also provide infrastructure to the region. For example, the Obskaya-Bovanenkovo-Karskaya Line, a railway line crossing the peninsula, was built by Gazprom and is used for oil transportation.

Oil and gas companies have overseen significant development in the region, often with financing from outside Russia. Novatek, which produced 9% of all natural gas in Russia in 2018, operates in 56 fields and license areas in Russia, including in Yamal. In 2018, Novatek sold 66 billion cubic meters of natural gas inside Russia and sold 6 billion abroad [54]. In the Yamal region, Novatek is directing a gas production project entitled Yamal LNG, which includes the construction of a seaport close to the village of Sabetta. The port, located on the Arctic Northern Sea Route, will be used to ship liquefied natural gas, initially with exports mostly to Europe, but with plans for increased exports to China. Novatek has received foreign investment for the Yamal LNG project. The French company Total and the Chinese corporation CNPC each own 20% of Yamal LNG shares, and the Silk Road Foundation owns 9.9%; Novatek retains 50.1% of shares (Novatek 2018). In March 2018, Total agreed to invest in the LNG-2 project to be built on the Gidan Peninsula [54]. However, these are not the only international sources of financing solicited by Novatek. In 2016, the Japan Bank for International Cooperation (JBIC) agreed to provide a loan to Novatek [55]. The Russian government owns just over 50% of the shares in Gazprom and Rosneft, so they depend somewhat less on foreign investment.

Alongside oil development, three groups of Indigenous people live in Yamal—the Nenets, the Selkup, and the Khanty. The Nenets comprise the majority of Yamal’s Indigenous population. Currently, there are more than 29,000 Nenets living in the region, who comprise almost 6% of the general population [56]. Traditionally, the Nenets are reindeer herders and fishers. In the Soviet period, the government attempted to force the local population into a sedentary way of life and work in Soviet reindeer herding kolkhozes (collective farms). However, due to the reindeer herders’ nomadic lifestyles, extremely remote herding routes, and difficulty accessing the area, Soviet rule failed to significantly influence the traditional Indigenous way of life in Yamal. Currently, Yamal has the largest reindeer livestock population in Russia, with most of the animals belonging to private herders, some working in former state farms which have been privatized and others operating independently. In 2010, there were 600,000 reindeer in Yamal, yet only 44% of privatized state farms have leased land officially; other reindeer herders use the land for pasture and migration without a formal lease [24].

The rights of Indigenous people and their ability to engage companies and other agents are defined in Russian federal and regional laws. According to federal law, representatives of the Indigenous small-numbered peoples of the North and Far East (ISPN) are entitled to legal protection of their traditional lifestyle. A number of federal laws (FL) and laws of the autonomous okrug (LAO) further guarantee these rights—for example, FL-82 On Guarantees of the Rights of Numerically Small Indigenous Peoples of the Russian Federation (1999), FL-104 On the General Principles of Organizing Small Indigenous Communities of the North, Siberia, and the Far East of the Russian Federation (2000), LAO-56 On subsoil use in Yamal-Nenets Autonomous Okrug, LAO-46 On Reindeer Herding (1998) and LAO-52 On Traditional Subsistence Territories of Regional Importance in YaNAO (2010) [57,58,59,60].

4.1. Indigenous Associations and Fragile Resistance

In the early 1990s, Russia was engulfed by a wave of social movements and new social organizations, including those associated with Indigenous rights, due to Gorbachev’s perestroika policies and the end of the Soviet regime. Social movements arose in Yamal, with the participation of several non-governmental organizations protecting the rights of Indigenous people. These groups helped to construct a legal basis to safeguard Indigenous rights at the regional level, including establishing mechanisms of public participation and governmental agencies dedicated to the rights of Indigenous people. These actions reduced conflict between the oil industry and Indigenous residents in Yamal. However, the effectiveness of these laws in guaranteeing rights appears questionable, as we explain in this section.

In the 1990s, oil and gas extraction intensified in YaNAO and the neighboring Nenets Autonomous Okrug (NAO). The land was seized for resource development and environmental conditions degraded, which spawned a number of conflicts between local residents and companies overseeing extraction. The Indigenous peoples’ movement in Yamal established an organizational framework, creating the regional association “Yamal to its Descendants” (Yamal—Potomkam!) in 1989 to coordinate their activities. In the 1990s, NGOs organized public lectures on Indigenous rights in the region, which forced the authorities and oil and gas companies to take into account the interests of Indigenous people when implementing industrial projects. Yamal to its Descendants helped to introduce regional laws protecting Indigenous people’s rights, such as the Laws of Autonomous Okrug (LAO) on Subsurface and Subsurface Management in YaNAO, on Local Self-Government in YaNAO, on The Regulation of Land Rights, on Reindeer Herding in YaNAO, and on Traditional Subsistence Territories [59,60,61,62]. The Department for Indigenous Small-Numbered Peoples of the North was created in the YaNAO administration in 2005. In addition, a system of Indigenous peoples’ representation was created, which reserved three seats, out of 22, for Indigenous members in the YaNAO legislative assembly.

Today there are several large Indigenous NGOs operating in Yamal. The largest and most important are “Yamal to its Descendants” and “Yamal”, both of which receive support through state grants, with additional funding from companies active in the region. These organizations contribute to the preservation of the traditional Indigenous lifestyle and culture, and participate in providing environmental and ethnological expertise, mainly to the Russian state. They also help negotiate agreements among companies, government authorities, and local communities. While these organizations aim to strengthen the YaNAO government’s pro-Indigenous policies, their work does not always enable ordinary Indigenous citizens to participate in decision-making about their environment and cultural preservation. Interviewees expressed concerns that these NGOs do not support complaints lodged by reindeer herders related to oil infrastructure, such as when pasture land is taken for development, leaving the territory for the growing reindeer livestock population in short supply.

The problem of land shortage is intensifying, due to ongoing industrial development in the Arctic and the seizure of land for oil extraction. Many reindeer herders express their desire to maintain their traditional economic practices, independent of the former state-owned reindeer herding enterprises, but they need sufficient land to do so. As one herder notes, “It’s easier [to herd reindeer] without the sovkhoz [state farm] … because it’s not the state who invented this traditional way of life”. (Reindeer herder, Yamal, Yamal district, 2017). As one herder remarks on the competition for territory, “It seems like a vast expanse. But, in fact, there are reindeer herders everywhere. If you are dropped from a plane somewhere, a reindeer herder will pop up in an hour and ask you what you are doing here.” (Head of the reindeer herding community, Yamal, Yamal district, 2017). According to the official data for 2010–2015, the reindeer population surpassed 700,000 animals in Yamal, almost twice the level considered to be a sustainable carrying capacity for the territory. The administration currently aims to develop an economic policy that would help preserve reindeer herding in YaNAO as the basis of Indigenous residents’ livelihoods, while also decreasing the number of reindeer overall, due to concerns about having sufficient land. However, this is quite difficult in practice. As one herder stated, “The reindeer are his [the herder’s] wallet, they are his bank... If he’s going to constantly decrease [the herd], how does that work?” (Representative of the reindeer-herding enterprise-1, Yamal district, Yamal, 2017).

Interviews revealed a deep ambivalence among local Indigenous people about oil and gas development. Some local citizens consider the negative effects of oil industry expansion in the Arctic a necessary evil, essential for the national economy and the country as a whole. An Indigenous community member seemed resigned to the damage, stating, “Well, I think even if it [the fishing] is dying out because of the oil and gas complex, it is for the whole of Russia that this gas is flowing. And if the fish are dying, then we’re going to have no fish … But if there’s no gas, there’s nothing, I guess” (Fisher, Yamal district, Yamal, 2017). However, other local residents are concerned about further environmental deterioration, land loss, and disappearance of fish from rivers, due to future oil extraction. A community leader notes, “They’ll start constructing a gas tower in your district. They’ll say, ‘We’re terribly sorry, but we have to relocate you to another district…’ [A local person] lived his whole life, moving along the river from the mouth to the headwaters. … He goes away, but there are other people out there already. They tell him, do not come here. And he becomes an outcast.” (Representative of the local administration-2, Yamal, Yamal district, 2017).

Russian laws protecting the rights of Indigenous people do not always work in practice. For example, Russian legislation allows Indigenous citizens to be assigned “territories of traditional nature use” (TTNU), enshrined in the Law on Traditional Subsistence Territories of Regional Importance in YaNAO (2010). However, since the law has come into force, not a single TTNU has been registered. Similarly, some federal laws safeguarding Indigenous people’s rights were not implemented in YaNAO. For instance, the federal law on ethnological expertise that focuses on additional protection of Indigenous rights has not been actively used, partly due to the lack of supporting regional legislation. An NGO leader comments, “We would really like [the law on ethnological expertise] to be applied. But this creates large obstacles for the gas industry. We tried to implement the law in Shuryshkarsky district. But it won’t pass. We have gas industry people in 50% [of the seats] in the legislative assembly. They won’t allow laws like that to pass.” (Representative of the NGO “Yamal for posterity,” Salekhard, Yamal, 2017). In addition, certain laws to assist reindeer herders are not enforced in practice, due to weak state control over the vast and often inaccessible territory in Yamal. The pasture territories where private herders let their reindeer graze have no formal borders, and disputes are resolved by custom: “The borders are determined by herders themselves. They resolve these issues between themselves. The state does not get involved. It is too afraid.” (Head of the reindeer herding community, Yamal, Yamal district, 2017). At the same time, reindeer herders cannot avail themselves of the opportunity to receive compensation from oil and gas companies for land seizure because the herders’ rights to the land are not legally formalized. “Lands are not vested in private herders. They are caught in between” (Head of the reindeer herding community, Yamal, Yamal district, 2017). Reindeer herders do not count on state support, which they consider inadequate: “Because it has always been like this among the Nenets, only counting on yourself.” (Local resident-3, Yamal, Yamal district, 2017). Instead, they rely on themselves and their personal networks when dealing with problems.

In recent years, new conflicts have arisen between oil and gas companies and reindeer herders. For example, in 2013 the reindeer herders of Tazovsky district opposed the construction of Lukoil facilities, including a pipeline. Although the participants at a public hearing voted against the project, it continued. In 2019, another conflict arose between reindeer herders and industry in Yamalsky district. Gazprom was constructing a gas pipeline across the Ob Bay (Obskaya Guba), but local residents believe that the project threatens the Ob Bay ecosystem. In February 2019, the online community Voice of Yamal (Golos Yamala) posted the following message: “Oil companies do not own the planet. I hope that you, who are going to drill in the Arctic, will think about your children and grandchildren, who will struggle for clean water, suffering from famine and crop failure. Look around. We live where the ice is thawing. We see the weather conditions change every year. A month hardly passes without some … damage done by rain, wind, or temperature. Look around you. We are here, where the water is getting warmer. People are losing their homes, their friends, their families” [63].

One reindeer herder who was interviewed had published a message, addressed to the UN secretary, demanding protection for local citizens. “We wrote a letter asking [the UN] to intervene in the construction process. We want a different, alternative pathway for the pipeline to be found. If they won’t do it, then our fish in the north will probably disappear. The pipeline construction will destroy the whole [flora and fauna] that whitefish feed on” [64].

Meanwhile, in conflicts between Indigenous people and companies, the Indigenous NGOs sometimes have not supported local actors resisting further industrial development. In March 2019, Yamal reindeer herders held a meeting on the tundra where they discussed the negative consequences of industrial development for the Indigenous local residents. This meeting was later sanctioned as an unauthorized public rally. The Indigenous association Yamal supported the side of the industry in the dispute, and lodged a complaint to the authorities against the organizer of the meeting. The reindeer herder faced fine of 30,000 rubles, until the court eventually decided that he was not guilty [65,66,67].

4.2. State Controlled Benefit Sharing

Although legal processes may fail to protect Indigenous people’s environmental rights, the sharing of revenue from the industrial activity may compensate for the negative effects of extraction on local communities. Benefit sharing is a strategy enshrined in several global conventions to ensure that Indigenous people in particular receive some reward from extraction on their traditional territories. In Russia benefit sharing arrangements in northern regions take diverse forms, most commonly through socio-economic partnership agreements among companies and regional, and in certain cases municipal, authorities [68,69,70,71]. In Yamal, there are a number of agreements among companies, government agencies, and local residents regulating the distribution of funds. These types of agreement are described below, from most to least formal in nature. The most significant benefit sharing happens through different levels of government intervention, although relatively little financial support is transferred to reindeer herders engaging in a traditional, nomadic way of life.

Socio-economic partnerships between the regional YaNAO authorities and oil and gas companies, which transfer funds to the regional budget for infrastructure development and social programs to the okrug, are the most significant form of benefit sharing in Yamal. A local leader stated, “First of all, the regional budget is nearly 90% composed of oil money. The companies finance the construction of schools, hospitals, boarding schools—and the upkeep of all that, too. And the agreement is ultimately a deal between two big bosses—the president of the company and the head of the [YaNAO] district.” (Representative of the local administration-3, Yamal, Yamal district, 2017). Initially, in the 1990s, the socio-economic agreements were tripartite—among the regional government, company, and Indigenous organizations, and were formalized at the YaNAO level. Currently, however, the agreements are generally bilateral between the state and the company. “The level of social investment provided by a company is determined during negotiations with the regional authorities.“ (Representative of the Department of Indigenous Affairs, Yamal, Salekhard, 2017). Funds from oil companies are transferred to the regional budget and used to construct and support housing, schools, churches, and hospitals. These framework agreements between an oil company and the regional authorities then serve as a basis for supplementary agreements regarding specific social programs, including those supporting the YaNAO Indigenous population. The funds are used to pay for gifted students’ education, summer camps, and equipment for villages, such as satellite phones, snowmobiles, power generators, and fuel. Some funding is distributed to lower levels of government. Municipal representatives may request funding for specific purposes from the YaNAO authorities. Depending on the number of applications and their justification, funds are then redistributed across the YaNAO. A YaNAO government official describes the process: “The application arrives to the department, and funds are allocated depending on the fiscal situation. If there is enough money, everyone receives some funding. If not, a municipality has to prove it needs this money. Applications are open once a year. … They budget for petroleum products, satellite phones, mini power sources, tarp, and first-aid kits.” (Representative of the Department of Indigenous Affairs, Salekhard, Yamal, 2017).

Oil and gas companies also may conclude agreements on socio-economic partnerships with local authorities (lower-level district authorities and municipalities) in relation to specific sites of extraction. A local administrator recounts, “When oil and gas companies arrive, they come to us. We confuse them [with our demands]. You come here, occupy our pastures, you have to compensate somehow. It is outside the scope of Russian law.” (Representative of the local administration-2, Yamal, Yamal district, 2017). As in the case of YaNAO agreements, the exact form and amount of benefits shared result from a negotiation between the company and government representatives. Another local government official explains, “First, they make a [verbal] agreement, and then, based on these verbal [agreements], they make an arrangement. First, they discuss what is feasible. If the other side says that it is, then they agree—it’s a deal.” (Representative of the local administration-3, Yamal, Yamal district, 2017). Most of the lower-level agreements are tripartite—with an Indigenous association as the third partner, alongside company representatives and government officials. In Yamalsky district, the agreements were concluded between the district authorities, a company and the association Yamal, while in Tazovsky district the third partner is the NGO Yamal for Posterity. According to these agreements, funds are spent on needs, such as constructing infrastructure, conducting secondary and post-secondary education, organizing holiday celebrations, and purchasing equipment. These lower-level agreements are most likely to occur on the territories where a company is actively operating, resulting in social and economic asymmetries between districts. Yamalsky and Tazovsky districts are considered the most prosperous in YaNAO, as they possess the main oil and gas deposits. Extractive activity on their territory allows them to receive additional financial support through benefit sharing. Meanwhile, other districts, deprived of direct connection with oil companies, are relatively disadvantaged in seeking benefits. Municipalities then find their requests for support to companies rebuffed: “Where there are no oil companies, you tell them [the company], we need money, for example, to preserve the Khanty bear festival. And they say, we do not work there, we’re not interested.” (Representative of NGO “Yamal”, Yamal district, Yamal, 2017).

In addition to negotiated socio-economic partnerships, oil and gas companies also pay financial compensation to local citizens for agricultural lands seized for extraction. The level of compensation is based on an official procedure that takes into account land valuation. However, only some former state-owned reindeer herding enterprises that were privatized in the post-Soviet period have official leases and are entitled to compensation in Yamal. In contrast, private reindeer herders have no land officially assigned to them, and thus, are not eligible for compensation for grazing land lost to company activity. As a result, some herders are compensated, and others are not; in either case, the levels of compensation are low. A private reindeer herder states, “[State-sanctioned] land users receive compensation—reindeer herding communities. They’re so lucky. If construction work begins [on their territory], they are paid for the loss of agricultural lands. It’s calculated by the [official] method. The whole land is fully vested in them. But the land price has now become minimal.” (Representative of the reindeer-herding enterprise-1, Yamal district, Yamal, 2017).

Finally, companies may provide low levels of financial aid to villages informally, for specific purposes, such as the purchase of goods, transportation, and holiday festivals. This support is provided to the local residents directly or channeled through a social organization. The amount of—aid is usually between several thousand rubles and tens of thousands of rubles (roughly between $50 and $1000). Generally, representatives of a school, library, or cultural institution will ask a company for one-time assistance for a specific event or program. These requests can be quite small, such as gifts for veterans or for children to mark a special occasion.

Thus, oil and gas companies are actively involved in the economic development of YaNAO through benefit sharing. Government officials play a key role in the distribution of benefits from “oil money,” and argue in favor of this centralized approach given that the government has a better understanding of the situation across the region than other actors. The YaNAO government is able to accumulate funds coming from various companies and distribute them according to the needs of districts and municipalities, allocating money for infrastructure projects, for example. They also can mitigate economic inequality between those districts with oil deposits and those districts without oil. Some experts see these socio-economic agreements as a better approach than transferring funds directly to Indigenous community members: “Where will this company money go [if given directly to reindeer herders]? Trinkets? The same trinkets that purchased Manhattan? The [YaNAO] money is spent on roads and houses—not on a snowmobile for specific reindeer herders. Therefore, I believe this is a good policy. When they ask for a new hospital, it will be easier to build the hospital right away.” (Expert, Arctic center, Salekhard, 2017). An NGO representative largely agreed, “We know better who needs what. Otherwise, they [the company] will finance the Solnyshko community near Sabetta instead of the Romashka community in Shuryshkarsky district. Whereas we know better than Romashka is more in need now than Solnyshko.” (Representative of the NGO “Yamal for Prosperity”, Yamal, Salekhard, 2017). Finally, other experts argue against direct agreements between the oil companies and the locals by pointing out that centralized agreements are more likely to avoid the dependency of reindeer herders on resource transfers from companies. A member of the Coordinating Council, created by Novatek for public consultations, who is also a local administrator stated: “If we pay reindeer herders directly now, we will bring about dependency, which is already thriving here …. Our reindeer herders have become kind of lazy.” (Representative of the coordinating Council, representative of the local administration, Yamal district, Yamal, 2017).

However, many local Indigenous community members point out that much of the funding for social infrastructure and programs serve to improve the lives of village dwellers, while Indigenous residents pursuing a traditional nomadic lifestyle receive the least benefit from the projects. Nomadic herders make little use of new village infrastructure, with the possible exception of sending their children to boarding schools. At the same time, industrial projects impose great costs on traditional reindeer herders, as they include the seizure of reindeer pastures and environmental degradation. A local resident from a village remarks, “The oil industry is probably better for villagers, because they [the companies] are building their infrastructure. We have new housing, a school, a gym, and they are building a new dormitory, too. It is probably worse for the tundra dwellers. Their lands are shrinking.” (Local resident-1, Yamal, Yamal district, 2017). A traditional herder states, “A lot of our land was seized for oil development. No compensation—only the company’s agreement with the region, and also some sub-agreements with the districts and municipalities. They do not directly negotiate with reindeer herders, only through the authorities. They rebuild villages, [and] construct schools, kindergartens, gyms.” (Head of the reindeer herding community, Yamal, Yamal district, 2017). Ultimately, traditional nomadic reindeer herders do not greatly benefit from these arrangements.

4.3. Forums of Negotiation between Oil Companies and Indigenous Communities

In Yamal, there are several forums to facilitate communication between the authorities, companies, and Indigenous people. First, public hearings and consultations with local residents are required by Russian law before the implementation of an industrial project. At a public hearing, local residents can communicate their concerns and make suggestions to companies. In some cases, these events allow the locals to mitigate the damaging effects of the industrial activities or solve certain problems. A local administrator gives an example, stating, “If the municipality residents are not very happy with the project, they can find a way to address these grievances through bargaining. They say ‘include this and that in the budget, or build us a hospital … or fly our children to school from the tundra.’ And after that, they [the municipality and company] conclude an agreement.” (Representative of the local administration-3, Yamal, Yamal district, 2017). A government official gave another example from 2010: “There was an occasion a couple of years ago, when a subsidiary of Gazprom or Yamal LNG wanted to build an artificial island in the Ob Bay. The people of three districts opposed it, and there was a petition to the governor. They [company and government representatives] decided it was no good. They didn’t make the artificial island.” (Representative of the Department of Indigenous Affairs, Salekhard, Yamal, 2017). However, public hearings are not always an effective form of interaction. Companies are not obliged to follow up on the suggestions of those attending the hearing. In addition, local citizens note that public hearings are often carried out in a formal way that does not involve real discussion. For example, some public hearings take place far away from the territory affected by the industrial project. A reindeer herder notes, “Reindeer herders have no time to attend public hearings. They are in the tundra all the time. That’s why they are formal, those hearings. They get a handful of people together, check it off the list, and that’s it.” (Head of the reindeer herding community, Yamal, Yamal district, 2017). Informal meetings with local residents, organized by the municipality, are another common form of company-community consultation in Yamal. The meetings are timed to occur before important events and major holidays to maximize participation. For example, a meeting of government and company representatives with local residents precedes the Reindeer Herder Festival each year. In these meetings, local residents may voice their concerns or suggestions.

In addition to officially organized hearings and meetings, every oil and gas company engages local citizens with its own problem-solving and communication strategies. Gazprom and Rosneft, for example, prefer to interact with locals through government agencies and procedures established by Russian law, such as public hearings. Novatek, with its financial commitments to foreign investors, is bound to follow international partners’ requirements and international standards for community consultation. (Representative of the coordinating Council, Yamal district, Yamal, 2017). In the villages near Novatek’s operations, a Coordination Council was formed that includes government and company representatives, as well as local residents. The main goal of the Council is to facilitate the company’s interactions with stakeholders. A local administrator describes the process: “There is the Coordination Council that meets twice a year to address emerging issues. It includes a company representative, a head, a representative of the Yamalsky district administration. Sometimes we meet more often, if it’s necessary to act quickly.” (Interview with the head of local administration, Yamal district, Yamal, 2017). A member of the council states, “The Coordination Council is what solves pressing problems, or any issues that emerge… For instance, if you need to conduct some survey or provide assistance in delivering groceries to the trading post. If the Coordination Council decides that help is needed … it contacts the CEO.” (Representative of the coordinating Council, Yamal district, Yamal, 2017). In addition, the company employs liaisons who regularly collect suggestions and complaints from Indigenous people about the company’s activities. There are also community liaison offices open in the villages affected by the company’s operations. However, this level of community consultation is not carried out by other oil and gas companies active in the region, further suggesting that standards promulgated by financing institutions play an important role. For example, the consulting firm Environ was hired to complete an impact assessment of the Yamal LNG project, which was funded in part by Total, the Japan Bank for International Cooperation and the China National Petroleum Corporation [72]. A district official states: “That’s why they [international actors] invest, they offer money at a small interest rate, but they closely monitor all of that. This is why the project was simply necessary. And the investors come here all the time and check the progress, like, they came to our village in April, checking everything, looking around, asking questions.” (Representative of the local administration-1, Yamal, 2017). International standards appear to have encouraged the company to introduce new practices of interaction.

5. Discussion: Nationalization, Globalization and the Role of the State

Despite the globalization of oil production in Russia, the state continues to play the most significant role in governing the oil and gas sector, particularly in regard to shaping the relationship between oil and gas companies and Indigenous people. We find evidence of the state’s continued robust role in several categories: Cultivating channels for interactions between different groups of actors in which government officials play a significant role; policing and suppressing other actors who have a desire to participate in the governance of oil; and playing a leading role in arranging benefit sharing. We argue that the dominance of the state indicates that rather than pursuing a “social license to operate,” as expected under more globalized governance, instead we see the continuation of a formal and informal “state license to operate”.

The state has continued to assert its governance in part because the oil and gas industry is a priority for the Russian government. Despite the globalization of oil production networks, nation-states for whom oil is a strategic resource are making a considerable effort to retain their regulatory authority and resist the global governance of oil, given that it is a source of economic growth and global political power. Oil and gas revenues accounted for more than 45% of Russia’s federal budget in 2015 [73], and constituted about 15% of GDP [74]. Europeans rely on Russian imports for 30% of imported gas and 35% of crude oil [75]. Gas is particularly important domestically, as it is used for roughly 50% of both residential heating and national electricity production [75]. The Russian government has attempted to convert natural resource abundance into political power on the world stage, and has used the supply of oil and gas to pressure post-Soviet neighboring states. Oil and gas also have served as a source of national pride. In 2005, President Putin declared that Russia is a superpower and world leader in the energy sector [76]. Energy security in Russian ideology is part and parcel of national security. Therefore, since Putin came into power in 2000, he initiated reforms that reinforce state control over oil production, including social issues related to oil production [77,78]. Revenue from the oil and gas sector fueled rapid economic growth from 1999 to 2008, and has been a means to improve living standards and invest in public infrastructure and social programs. Arguably, oil and gas wealth also have allowed the state greater autonomy from taxing citizens, and therefore, greater independence of action more generally.

Nevertheless, under global market pressures, Russian oil and gas companies have selectively adopted global standards, such as the Global Compact, Global Reporting Initiative (GRI), and ISO certification. Financial ties to equity partners and international financial institutions, as in the Novatek case, appear to foster some implementation of global standards, such as those that protect Indigenous peoples’ rights. Novatek has made a greater effort than other companies to provide forums of negotiations for Indigenous communities, such as the Coordination Council, which is established to allow some citizen participation in governance, and which may serve to limit violations of Indigenous peoples’ rights. Overall, however, governance of the oil and gas sector in Russia generally does not feature strong adherence to global standards, in part because of the state’s interest in remaining the key decision maker. This is in contrast to the more robust role of global governance in some of Russia’s other natural resource sectors, such as forestry [33]. The Russian government’s reliance on oil for economic and political power acts as a kind of barrier to blunt global influences. Research conducted in Yamal demonstrates how Russian state officials remain closely involved in interactions among oil and gas companies, Indigenous NGOs, and local communities, including in shaping benefit sharing arrangements. The state allows globalization of oil production networks and supply changes, encourages foreign investment and partnerships, and the transfer of advanced technologies. However, the day to day governance of oil and gas resources, including its social and environmental aspects, remains under strict state legislation and control as the state owns the land, leases it to companies, and regulates other land users.

5.1. State Controlled Civic Activity and Forums of Negotiation

Global governance rules and standards often are designed to strengthen the role of NGOs and Indigenous associations within a governance generating network. However, in the case of Yamal, Indigenous associations work closely with the regional government and industry. These NGOs emerged first as social movement organizations in the mid-1980s to late 1990s with the goal of protecting Indigenous peoples’ rights. However, although these groups remain involved in community affairs and offer grants for community development, Indigenous associations now often appear to serve to legitimize state policies and decisions. Neither of the associations Yamal nor Yamal to its Descendants is involved in transnational Indigenous networks or other transnational NGO networks, and they have not participated in the United Nations Indigenous peoples’ committees or those of other global institutions. Instead, their primary relationship is with the regional and local authorities in Yamal. Both groups organize local forums between government officials and Indigenous reindeer herders, and participate in the negotiation of socio-economic agreements and state funding that is distributed across the region. In several notable cases, these Indigenous associations have supported the government’s position on oil construction projects, despite local concerns and grassroots efforts to negotiate with company representatives. For example, in the 2019 conflict between Gazprom and Indigenous reindeer herders around pipeline construction, both Indigenous associations supported the agenda of oil companies and the state and not the local Indigenous community. Indeed, reindeer herders’ resistance to pipeline construction and their appeal to the UN led to repression [65,66,67]. Without the support of regional NGOs or links to a transnational NGOs network, the resistance movement demobilized.

In a governance generating network, forums of negotiations between oil companies and civil society representatives may be organized across scales and involve both global and local actors. Indigenous associations in Yamal do not participate in transnational forums, such as the Arctic Council or UN working groups, instead of relying on public hearings organized by municipal authorities. However, most public hearings appear to be carried out as a formality and do not represent a means of reconciling the interests of oil companies and Indigenous people. The Coordination Council, organized by Novatek and stimulated by the guidelines of foreign investment banks, is an exception and includes participation by Indigenous people and company representatives engaged in public relations.

5.2. State Controlled Benefit Sharing Arrangements

Efforts to strengthen the global rules and standards that govern extraction have highlighted the importance of gaining a “social license to operate” from local actors, including affected communities, Indigenous peoples, and NGOs. In Yamal, however, we see the enduring importance of a “state license to operate.” Decisions about oil exploration, extraction, and transportation in Yamal—regardless of their impact on local residents—are made with the permission of or through negotiations with state actors. In practice, an SLO is granted by regional authorities, not local stakeholders. A similar default to state preferences is present in benefit sharing as well. Benefit sharing between industries and communities at sites of extraction has emerged as an important guideline in the global governance of natural resources. In Yamal, benefit sharing is taking place in several forms, including socio-economic agreements with the regional government and municipalities [79], and the regional and local authorities are the key negotiators about levels of funding and decision makers about how that funding should be allocated. Given that the vast majority of tax revenue from the oil and gas industries flows into the federal budget, socio-economic agreements provide a means for regional and local authorities to retain funding locally to fill gaps in regional budgets and to support public infrastructure. The financial transfers generally benefit village-dwellers who make use of public infrastructure, rather than reindeer herders engaged in traditional practices. Reindeer herding enterprises that lease agricultural lands designated for reindeer herding are able to use a federally-developed methodology to demand compensation for land lost to or damaged by industrial development, but reindeer herders’ enterprises that do not have leases do not have the same opportunity. Since regional legislation on “territories of traditional natural resource use” has not been utilized to this point, a large number of private reindeer herders are using traditional lands without legal confirmation of their rights. To this point, government agencies have not assisted herders in designating TTNUs, which would make herders eligible for compensation.

6. Conclusions

As the governance of extractive industries has increasingly globalized, with new rules and standards for the protection of Indigenous rights and the environment, a new avenue for the voices of local stakeholders has been created. The emergence of governance generating networks around particular industries anticipates that forums of negotiation will link global rule-making bodies with sites of implementation. In this process, the state would become one of many actors claiming a role in governance. However, these governance networks may not develop, due to conditions at the national or regional level. As a result, Indigenous communities may remain vulnerable to rights violations and may not benefit from global governance guidelines.

Yamal is an important case for exploring the power and limitations of global governance in the extractive sector. In Yamal, we see government agencies strongly asserting the right of the state to govern interactions between oil and gas companies and Indigenous peoples. Based on this case, resistance to global governance appears more likely to occur under the following conditions: (1) In a state that has relied on extractive resources for economic and political power, and in a region of the country that is an important oil and gas producing area; (2) under an authoritarian regime that has exerted substantial influence over civil society and social movements, including Indigenous NGOs and activism; (3) when domestic laws to protect Indigenous rights are only weakly developed or not enforced; and (4) where many of the oil and gas companies are wholly or partially state-owned.

In Yamal, global flows of financing for the oil and gas industry and global supply chains are growing rapidly. Russian oil and gas companies have sought relationships with international investors and equity partners and have adopted some global standards, such as ISO 14000 and ISO 26000, and participate in the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) in order to increase their competitiveness in international markets. Of the companies operating in Yamal, Novatek is both the most exposed to global financing and the most likely to conform to global standards of community consultation, raising intriguing questions about the factors that shape the behavior of private actors, in the absence of state requirements. At the same time, transnational networks bringing together global and local actors remain underdeveloped. The major Indigenous associations in Yamal are disconnected from their international counterparts. Government agencies have been able to maintain their authority by either co-opting or discouraging actors who would participate in the global governance networks at the sites of implementation and by inserting themselves as influential actors in globally-endorsed processes, such as benefit sharing. The result is that Indigenous communities are limited in their ability to take advantage of global conventions and standards that are intended to protect their rights— and that Indigenous people engaged in traditional livelihoods are the least likely to gain from benefit sharing. Overall, governance generating networks in the region are under-developed.

The Yamal case indicates that states may be able to adapt to economic globalization without a corresponding erosion in their governance authority. Through a combination of national rules and informal incentives for companies, state control of civil society, and adaptation to some aspects of global standards, the state may be able to selectively filter certain aspects of global governance to limit the significance of a “social license to operate” and prioritize the “state license.”

Author Contributions

M.S.T. and S.A.T. were involved in fieldwork, data collection, analysis, conceptualization and writing. L.A.H. and L.S.H. were involved in analysis, conceptualization and writing.

Funding

This research was funded by the internship at the National Research University Higher School of Economics, (HSE-Moscow), the NWO, the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research, Arctic Program (“Developing benefit sharing standards in the Arctic”, # 866.15.203), and the Arctic Fulbright Program.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the Laboratory for studies in economic sociology (HSE) for feedback on this work and all our informants in Yamal for a valuable time during the interview process.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Interviews.

Table A1.

Interviews.

| Date | Informant | Location |

|---|---|---|

| 11.07.2017 | Expert of the Arctic Center | Salekhard |

| 12.07.2017 | Representative of the NGO “Yamal for descendants”—1 | Salekhard |

| 12.07.2017 | Representative of the NGO “Yamal for descendants”—2 | Salekhard |

| 15.07.2017 | Representative of the Department of Indigenous Affairs | Salekhard |

| 16.07.2017 | Head of the reindeer herding community | Yamal district |

| 18.07.2017 | Local resident—1 | Yamal district |

| 18.07.2017 | Local resident—2 | Yamal district |

| 19.07.2017 | Representative of the reindeer-herding enterprise—1 | Yamal district |

| 19.07.2017 | Representative of the reindeer-herding enterprise—2 | Yamal district |

| 20.07.2017 | Representative of the local administration—1 | Yamal district |

| 20.07.2017 | Staff member of the House of Culture | Yamal district |

| 20.07.2017 | Representative of the coordinating Council | Yamal district |

| 21.07.2017 | Representative of NGO “Yamal” | Yamal district |

| 21.07.2017 | Representative of the reindeer-herding enterprise—3 | Yamal district |

| 22.07.2017 | Fisher | Yamal district |

| 22.07.2017 | Representative of the local administration—2 | Yamal district |

| 23.07.2017 | Representative of the local administration—3 | Yamal district |

| 23.07.2017 | Staff member of school | Yamal district |

| 24.07.2017 | Local resident—3 | Yamal district |

| 24.07.2017 | Local resident—4 | Yamal district |

| 24.07.2017 | Reindeer herder—1 | Yamal district |

| 25.07.2017 | Reindeer herder—2 | Yamal district |

| 25.07.2017 | Reindeer herder—3 | Yamal district |

References

- Swyngedouw, E. Globalisation or ‘glocalisation’? Networks, territories and rescaling. Camb. Rev. Int. Aff. 2004, 17, 25–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swyngedouw, E. The Marxian alternative: Historical-geographical materialism and the political economy of capitalism. In A Companion to Economic Geography; Sheppard, E., Barnes, T.J., Eds.; Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 2000; pp. 41–59. [Google Scholar]

- International Council on Mining and Metals (ICMM). Indigenous Peoples and Mining: Position Statement; ICMM: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Grieg-Gran, M. Financial Incentives for Improved Sustainability Performance: The Business Case and the Sustainability Dividend; International Institute for Environment and Development and World Business Council for Sustainable Development: London, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, C. Civil Society Initiatives and “Soft Law” in the Oil and Gas Industry. Int. Law Politics 2004, 36, 456–502. [Google Scholar]

- Castells, M. The Rise of the Network Society; Blackwell Publishers: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Castells, M. The Information Age: Economy, Society and Culture; Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Keck, M.; Sikkink, K. Activists Beyond Borders: Advocacy Networks in International Politics; Cornell University Press: Ithaca, NY, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Guzmán-Gallegos, M. Controlling abandoned oil installations: Ruination and ownership in Northern Peruvian Amazonia. In Indigenous Life Projects and Extractivism: Ethnographies from South America; Vindal Ødegaard, C., Rivera Andía, J.J., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 53–73. [Google Scholar]

- Krøijer, S. In the spirit of oil: Unintended flows and leaky lives in Northeastern Ecuador. In Indigenous Life Projects and Extractivism: Ethnographies from South America; Vindal Ødegaard, C., Rivera Andía, J.J., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 95–118. [Google Scholar]

- Novikova, N. Indigenous peoples of the Russian North and the oil and gas companies: Managing risk. Arct. Ecol. Econ. 2013, 3, 102–111. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Stammler, F. Oil without conflicts. The anthropology of industrialization in Northern Russia. In Crude Domination. An Anthropology of Oil; Behrends, A., Reyna, S., Günther, S., Eds.; Berghahn Books: New York, NY, USA; Oxford, UK, 2011; pp. 243–269. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, E.; Istomin, K. Beads and Trinkets? Stakeholder Perspectives on Benefit-sharing and Corporate Responsibility in a Russian Oil Province. Eur. Asia Stud. 2019, 71, 1285–1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sulyandziga, L. Indigenous peoples and extractive industry encounters: Benefit-sharing agreements in Russian Arctic. Polar Sci. 2018, 21, 68–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tysiachniouk, M.; Henry, L.; Lamers, M.; Tatenhove, J. Oil and Indigenous people in sub-Arctic Russia: Rethinking equity and governance in benefit sharing agreements. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2018, 37, 140–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrov, A.; Tysiachniouk, M. Benefit Sharing in the Arctic: A Systematic View. Resources 2019, 8, 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tysiachniouk, M.; Petrov, A.; Kuklina, V.; Krasnoshtanova, N. Between Soviet Legacy and Corporate Social Responsibility: Emerging Benefit Sharing Frameworks in the Irkutsk Oil Region, Russia. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tysiachniouk, M.; Tulaeva, S. Benefit-Sharing Arrangements between Oil Companies and Indigenous People in Russian Northern Regions. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1326. [Google Scholar]

- Bilgin, M. Energy security and Russia’s gas strategy: The symbiotic relationship between state and firms. Communist Post Communist Stud. 2001, 44, 119–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodgers, D. The Depth of Russia. Oil, Power and Culture after Socialism; Cornell University Press: Ithaca, NY, USA; London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, E. The Oil Company, the Fish, and the Nivkhi: The Cultural Value of Sakhalin Salmon. In Keystone Nations: Indigenous Peoples and Salmon across the North Pacific; Colombi, B.J., Brooks, J.B., Eds.; SAR Press: Santa Fe, NM, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Ross, M. The Oil Curse: How Petroleum Wealth Shapes the Development of Nations; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Kvale, S. Interviews: An Introduction to Qualitative Research Interviewing; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Martynova, E.; Novikova, N. Tazovsky Nenets in Terms of Oil and Gas Development; IP AG Yakovlev: Moscow, Russia, 2011. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Stammler, F.; Wilson, E. Dialogue for Development: An Exploration of Relations between Oil and Gas Companies, Communities and the State. Sibirica 2006, 5, 1–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boasson, E.; Wettestad, J.; Bohn, M. CSR in the European Oil Sector: A Mapping of Company Perceptions. FNI-rapport 9/2006; The Fridtjof Nansen Institute: Lysaker, Norway, 2006; 22p. [Google Scholar]

- Haufler, V. Global Governance and the Private Sector. In Global Corporate Power; May, C., Ed.; Lynne Rienner: Boulder, CO, USA, 2006; pp. 95–105. [Google Scholar]

- Frynas, G. Corporate social responsibility in the oil and gas sector. J. World Energy Law Bus. 2009, 2, 178–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watts, M. Righteous Oil? Human Rights, the Oil Complex and Corporate Social Responsibility. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2005, 30, 373–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watts, M. Petro-violence: Community, extraction, and political ecology of a mythic commodity. In Violent Environments; Peluso, N.L., Watts, M., Eds.; Cornell University Press: Ithaca, NY, USA; London, UK, 2001; pp. 189–212. [Google Scholar]

- Watts, M. Resource curse? Governmentality, oil and power in the Niger Delta, Nigeria. Geopolitics 2004, 9, 50–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierk, S.; Tysiachniouk, M. Structures of mobilization and resistance: Confronting the oil and gas industries in Russia. Extr. Ind. Soc. 2016, 3, 997–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tysiachniouk, M. Transnational Governance Through Private Authority: The Case of the Forest Stewardship Council Certification in Russia; Wageningen Academic Publishers: Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Tysiachniouk, M.; McDermott, C. Certification with Russian characteristics: Implications for social and environmental equity. For. Policy Econ. 2016, 62, 43–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tysiachniouk, M.; Henry, L. Managed citizenship: Global forest governance and democracy in Russian communities. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. 2015, 22, 476–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, E. What is Benefit Sharing? Respecting Indigenous Rights and Addressing Inequities in Arctic Resource Projects. Resources 2019, 8, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bridge, G. Global production networks and the extractive sector: Governing resource-based development. J. Econ. Geogr. 2008, 8, 389–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bice, S.; Brueckner, M.; Pforr, C. Putting social license to operate on the map: A social, actuarial and political risk and licensing model (SAP Model). Resour. Policy 2017, 53, 46–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, E. What is the social licence to operate? Local perceptions of oil and gas projects in Russia’s Komi Republic and Sakhalin Island. Extr. Ind. Soc. 2016, 3, 73–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moffat, K.; Zhang, A. The paths to social licence to operate: An integrative model explaining community acceptance of mining. Resour. Policy 2014, 39, 61–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prno, J.; Slocombe, D.S. Exploring the origins of ‘social license to operate’ in the mining sector: Perspectives from governance and sustainability theories. Resour. Policy 2012, 37, 346–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, L. The Social Licence to Operate: Your Management Framework for Complex Times. Do Sustainability; Routledge: Oxford, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, N.; Lacey, J.; Carr-Cornish, S.; Dowd, A.M. Social licence to operate: Understanding how a concept has been translated into practice in energy industries. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 86, 301–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owen, J.R.; Kemp, D. Social licence and mining: A critical perspective. Resour. Policy 2013, 38, 29–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jijelava, D.; Vanclay, F. Legitimacy, credibility and trust as the key components of a social licence to operate: An analysis of BP’s projects in Georgia. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 140, 1077–1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buhmann, K. Public regulators and CSR: The ‘social licence to operate’ in recent United Nations instruments on business and human rights and the juridification of CSR. J. Bus. Ethics 2016, 136, 699–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forbes, B.C.; Stammler, F. Arctic climate change discourse: The contrasting politics of research agendas in the West and Russia. Polar Res. 2009, 28, 28–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasilkova, T.; Evay, A.; Martynova, E.; Novikova, N. Indigenous Peoples and Industrial Development of the Arctic. Ethnological Monitoring in the Yamal-Nenets Autonomous Okrug; Tishkov, V., Mataev, S., Eds.; Shadrinsky house Press: Shadrinsk, Russia, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Novikova, N.; Wilson, E. The Sakhalin2 Project Grievance Mechanism, Russia. In Dispute or Dialogue? Community Perspectives on Company-Led Grievance Mechanisms; Wilson, E., Blackmore, E., Eds.; Intern. Inst. for Environment and Development: London, UK, 2013; pp. 84–109. [Google Scholar]

- Extraction of Oil and Gas in YaNAO. Official Website of YaNAO Administration. 2018. Available online: https://www.yanao.ru/presscenter/news/5302/ (accessed on 17 September 2019).

- Nalimov, P.; Rudenko, D. Socio-Economic Problems of the Yamal-Nenets Autonomous Okrug Development. Procedia Econ. Financ. 2015, 24, 543–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larchenko, L.; Kolesnikov, R. Development of resource centers of the Yamal-Nenets Autonomous Okrug specializing in hydrocarbon production. Innovations 2016, 1, 79–84. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Zubarevich, N. Socio-Economic Development in the Regions: 2018 Results (28 March 2019). Monitoring of Russia’s Economic Outlook. Moscow. IEP 2019, 26, 13–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PAO NOVATEK. NOVATEK Annual Review: Expanding Our Global LNG Footprint. 2018. Available online: http://www.novatek.ru/en/investors/reviews/ (accessed on 15 September2019).

- Dziadko, T. The Bank, Which Joined the Country’s Sanctions, Will Give Credit to NOVATEK for the First Time. RBC 2 September 2016. Available online: https://www.rbc.ru/business/02/09/2016/57c939d49a7947397f368c10 (accessed on 5 September 2019). (In Russian).