Managing Innovation Resources in Accordance with Sustainable Development Ethics: Typological Analysis

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Sustainability Crisis

1.2. Focusing on Long-Term Rationality

1.3. Previous Research

1.4. Research Outline

2. Methodology

2.1. Conceptual Design of Typological Analysis.

- Strategic environmental innovations (SEnI) are aimed at eradicating deep systemic causes of global environmental problems through the implementation and expansion of radical environmentally-oriented innovative technologies. Examples include: innovations in the sphere of clean energy, “free” or renewable energy sources, clean production technologies, non-waste production, and consumption cycles.

- Strategic social innovations (SSI) are intended to eliminate identifiable causes of global social problems through the implementation of radically innovative social technologies, thus transforming the basis of current social–economic systems, interactions, and relationships, and providing significant, steady humanization of societal systems. Examples include: innovations that increase the role of every human in social life and development, establishing priorities for individual and social collaborative development over money, profit, and competition; holistic systems of health-saving technologies; readily available, effective medicine, eliminating the causes of human illnesses and substantially improving human health, immune systems, life quality, and life expectancy; social, psychological, and educational innovations, which help people develop an active personality with free will, an extended mind, critical, logical, and systemic thinking, and the ability to find deep cause–effect relationships and to predict long-term effects; and social technologies that support innovators and innovations with high social significance.

- Strategic economic innovations (SEI) serve the purpose of solving systemic global economic problems, such as poverty, resource deficits, over-production, and over-consumption, and eliminate economic reasons for wars and catastrophe. SEIs improve the life quality of the whole society, recondition economic relationships between humans based on the premise that “the economic” serves “the social”, and not vice versa. The goals and means of SEI match the basic humanistic values and principles of a Steady-State Economy and their results significantly increase the integrated ecological, social, and economic wealth of society. Examples include: local currencies, collaborative and sharing economies, blockchain technology, and automation of unsafe and unhealthy production operations.

- Tactical environmental innovations (TEI) are designed to prevent the worst consequences of radical environmental problems and solve particular environmental problems without touching their deep causes or anthropogenic character. Examples include: innovative technologies for resource-saving production in particular industries; technologies that significantly decrease environmental pollution and environmental threats in mining industries and other unsafe production, and new methods and reagents for cleaning seas and oceans from oil and other pollution.

- Tactical social innovations (TSI) are aimed at preventing and solving significant social problems without radically eliminating their root causes. Examples include: new methods for developing tactical analytical thinking in the educational system; increasing the level of automation and computerization of manual and intellectual labor in existing workplaces, improving information and communication technologies and infrastructure; implementing effective mechanisms and systems supporting innovators who develop market-oriented and profitable innovations; developing health saving technologies, and curing and revitalizing medical technologies.

- Tactical economic innovations (TEI) provide significant mid-term economic SD effects. They are aimed at solving economic problems at the tactical level using innovative methods and instruments that are available in the framework of the current socio-economic system. Results of implementation of TEI slow down resource exhaustion, ease environmental problems, improve food safety, and increase economic prosperity. Examples include: innovations providing competitiveness of a particular territory; in particular, technologies that decrease resource consumption and increase availability of material welfare.

- Operative environmental innovations (OEnI) deal with the particular multi-layered implications of consequences associated with global climate change. They are new technologies or practices aimed at preserving threatened species, innovative methods of eliminating consequences of anthropogenic and natural catastrophes, along with innovations that help people adapt to unfavorable ecological conditions. Examples include: new technologies for cleaning water after oil spills, new materials for filtering potable water, and new technologies for building houses from plastic waste.

- Operative social innovations (OSI) are aimed at alleviating the most urgent social problems, which can be characterized as consequences of root social problems (non-effective and conflict mechanisms of the actual social–economic system). OSIs provide step-by-step improvements in social institutions and organizations within the framework of existing policies and processes. OSIs are mainly oriented towards profitable and short-term health policies and programs. Examples include: optimization of existing bureaucratic procedures; new medicines that cure symptoms more effectively or provide better pain relief; new ways of identifying people who need urgent psychological or financial aid; new psychological techniques that help people to overcome stress because of unemployment, gender, ethnicity, or income inequality.

- Operative economic innovations (OEI) imply new ways to create short-term profit maximization. Examples include: innovations that increase the effectiveness and scale of mining industries and existing forms of production; new technologies that increase the possibility of extract finite, non-renewable resources; and marketing innovations that boost consumption.

2.2. Materials and Methods

- (1)

- Classification of supported innovation projects according to their SD effects. Each project was allocated to the appropriate classification group according to their potential SD effects. An innovation project could be allocated to several classification groups if it implied different effects simultaneously, for example strategic environmental and tactical economic effects, or tactical social and operative environmental effects. Calculation of the number of innovation projects in each cell of the typological matrix for classification of sustainability-oriented innovation activities in two periods: 2009–2015 and 2016–2017 (Table 3).

- (2)

- Formalization of the typological analysis results in matrices consisting of absolute and relative values and visualization of the results.

- (3)

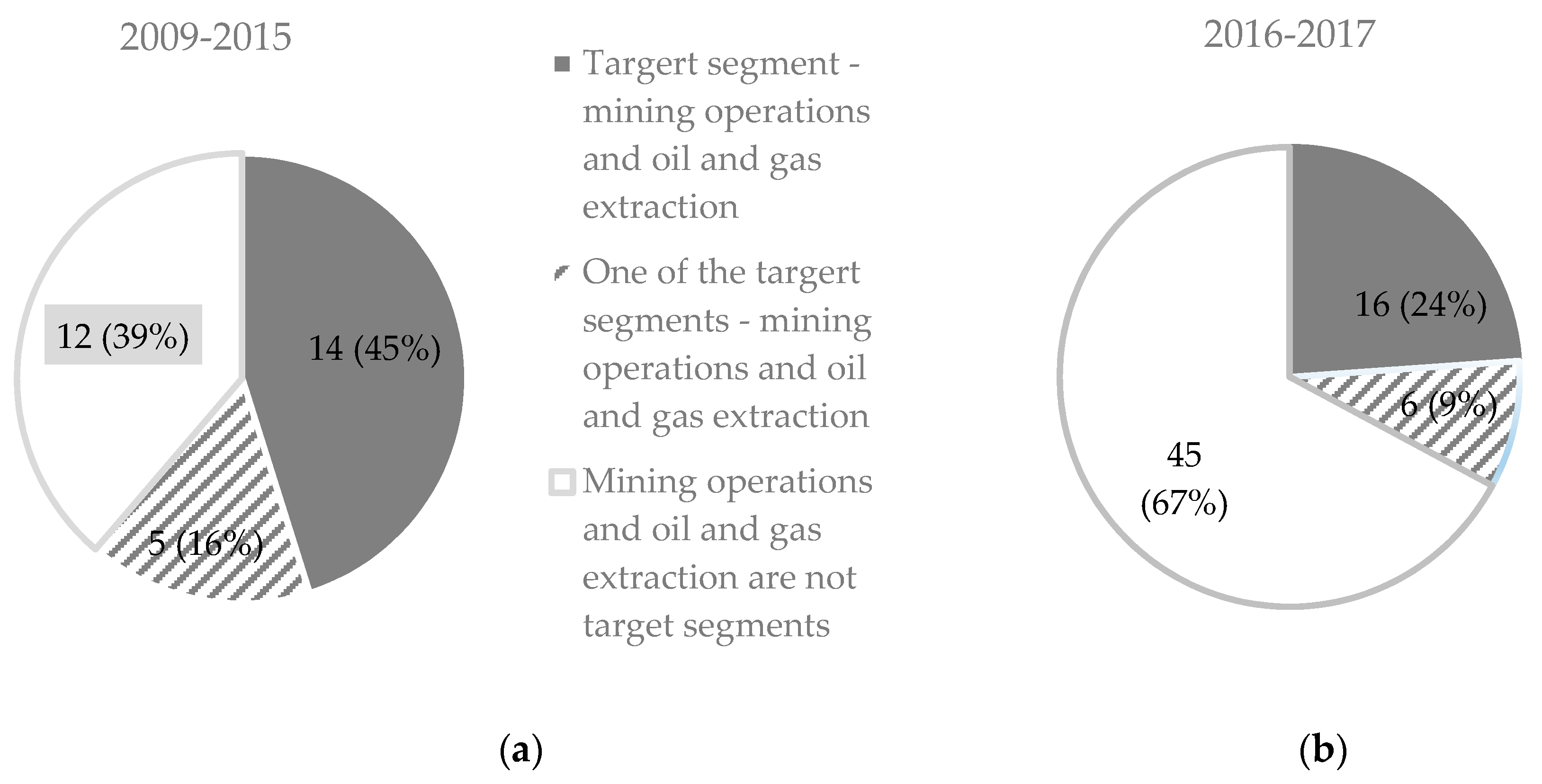

- Identification of supported innovation projects belonging to mining operations and the oil and gas industry.

- (4)

- Assessment of basic conditions for an effective sustainability-oriented innovation support system on the basis of typological analysis, including comparison of typological matrices by time periods (2009–2015 and 2016–2017).

- (5)

- Development of recommendations on which transformations in decision making policy are necessary to significantly increase the innovation system’s potential impact on achieving wider SD goals.

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

5.1. Recommendations

5.2. Research Implications

5.3. Limitations and Further Research Development

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Meadows, D.H.; Meadows, D.L.; Randers, J. The Limits to Growth: A Report for the Club of Rome’s Project on the Predicament of Mankind; Universe Books: New York, NY, USA, 1972; ISBN 0-87663-165-0. [Google Scholar]

- Baudrillard, J. The Consumer Society: Myths and Structures; SAGE Publications: London, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Ilin, A.N. Consumerism as a Factor in Anti-Cultural Innovation. Voprosy Filosofii 2016, 4, 171–181. [Google Scholar]

- Daly, H.E.; Farley, J. Ecological Economics; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Hoekstra, A.Y. The Water Footprint of Modern Consumer Society; Routledge: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- UNEP. Managing and Conserving the Natural Resource Base for Sustained Economic and Social Development. Report from the International Resource Panel. 2014. Available online: http://www.resourcepanel.org/reports/policy-coherence-sustainable-development-goals (accessed on 10 January 2019).

- World Commission on Environment and Development. Our Common Future; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- UNEP. Decoupling Natural Resource Use and Environmental Impacts from Economic Growth. A Report of the Working Group on Decoupling to the International Resource Panel. Fischer-Kowalski, M., Swilling, M., von Weizsäcker, E.U., Ren, Y., Moriguchi, Y., Crane, W., Krausmann, F., Eisenmenger, N., Giljum, S., Hennicke, P., et al., Eds.; 2011. Available online: http://www.resourcepanel.org/reports/decoupling-natural-resource-use-and-environmental-impacts-economic-growth (accessed on 10 January 2019).

- WWF Global. Living Planet Report. 2016. Available online: http://wwf.panda.org/about_our_earth/all_publications/lpr_2016/ (accessed on 10 January 2019).

- von Weizsäcker, E.; Wijkman, A. Come On! Capitalism, Short-termism, Population and the Destruction of the Planet; A Report to the Club of Rome; Springer Science+Business Media LLC: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Stiglitz, J. The Price of Inequality; Allen Lane: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Gallopín, G. A Systems Approach to Sustainability and Sustainable Development; United Nations: Santiago, Chile, 2003; ISSN 1564-4189. [Google Scholar]

- Matjaz, M.; Maletic, D.; Dahlgaard, J.J.; Dahlgaard-Park, S.M.; Gomiscek, B. Effect of sustainability-oriented innovation practices on the overall organizational performance: An empirical examination. Total Qual. Manag. Bus. 2016, 27, 1171–1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanninen, T. Crisis of Global Sustainability; The Global Institutions Series; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Raworth, K. Doughnut Economics. Seven Ways to Think Like a 21st-Century Economist; Random House Business Books: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Cayli, B. The ravages of social catastrophe: Striving for the quest of ‘Another World’. Philos. Soc. Crit. 2015, 41, 963–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grosso, A. Minding the Modern: Human Agency, Intellectual Traditions, and Responsible Knowledge. Tradit. Discov. 2015, 42, 45–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcez, M.P.; Hourneaux, J.F.; Farah, D. Green Plastics: Analysis of a Firm’s Sustainability Orientation for Innovation. Revista de Gestao Ambiental e Sustentabilidade-Geas 2016, 5, 21–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IRP. Redefining Value–The Manufacturing Revolution. Remanufacturing, Refurbishment, Repair and Direct Reuse in the Circular Economy; A Report of the International Resource Panel; Nasr, N., Russell, J., Bringezu, S., Hellweg, S., Hilton, B., Kreiss, C., von Gries, N., Eds.; United Nations Environment Programme: Nairobi, Kenya, 2018; Available online: http://www.resourcepanel.org/reports/re-defining-value-manufacturing-revolution (accessed on 10 January 2019).

- Busch, J.; Foxon, T.J.; Taylor, P.G. Designing industrial strategy for a low carbon transformation. Environ. Innov. Soc. Transit. 2018, 29, 114–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schot, J.; Kanger, L. Deep transitions: Emergence, acceleration, stabilization and directionality. Res. Policy 2018, 47, 1045–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Noi, C.; Ciroth, A. Environmental and social pressures in mining. Results from a sustainability hotspots screening. Resources 2018, 7, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IRENA. Rethinking Energy 2017: Accelerating the Global Energy Transformation; International Renewable Energy Agency: Abu Dhabi, UAE, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- UNEP. City-Level Decoupling: Urban Resource Flows and the Governance of Infrastructure Transitions. A Report of the Working Group on Cities of the International Resource Panel. Swilling, M., Robinson, B., Marvin, S., Hodson, M., Eds.; 2013. Available online: http://www.resourcepanel.org/reports/city-level-decoupling (accessed on 10 January 2019).

- Vishnyakov, I.E.; Borchsenius, S.N.; Kayumov, A.R.; Rivkina, E.M. Mycoplasma Diversity in Arctic Permafrost. BioNanoSci 2016, 6, 516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motesharrei, S.; Rivas, J.; Kalnay, E. Human and nature dynamics (HANDY): Modeling inequality and use of resources in the collapse or sustainability of societies. Ecol. Econ. 2014, 101, 90–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapor, P. Complexity, Chaos and Economic Modeling. In Proceedings of the 21st International Scientific Conference on Economic and Social Development, Belgrade, Serbia, 18–19 May 2017; pp. 273–282. [Google Scholar]

- Laurenti, R.; Martin, M.; Stenmarck, Å. Developing adequate communication of waste footprints of products for a circular economy—A stakeholder consultation. Resources 2018, 7, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IRENA. Innovation Priorities to Transform the Energy System; International Renewable Energy Agency: Abu Dhabi, UAE, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- IRP. Green Technology Choices: The Environmental and Resource Implications of Low-Carbon Technologies; A Report of the International Resource Panel; Suh, S., Bergesen, J., Gibon, T.J., Hertwich, E., Taptich, M., Eds.; United Nations Environment Programme: Nairobi, Kenya, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Kozlov, A.; Gutman, S.; Rytova, E.; Zaychenko, I. Human and Economic Factors of Long-Distance Commuting Technology: Analysis of Arctic Practices. In Advances in Social & Occupational Ergonomics. Advances in Intelligent Systems and Computing; Goossens, R., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; Volume 487. [Google Scholar]

- Adams, R.; Jeanrenaud, S.; Bessant, J.; Denyer, D.; Overy, P. Sustainability-oriented Innovation: A Systematic Review. IJMR 2016, 18, 180–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilipiszyn, A.C.; Hedjazi, A.B. Implementation of the Sustainable Development Goals in GCC countries via application of sustainability-oriented innovation to critical infrastructures. In Gulf Research Meeting: Towards a Sustainable Lifestyle in the Gulf; University of Cambridge: Cambridge, UK, 2016; pp. 78–102. [Google Scholar]

- Wehnert, P.; Kollwitz, C.; Daiberl, C. Capturing the Bigger Picture? Applying Text Analytics to Foster Open Innovation Processes for Sustainability-Oriented Innovation. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, F. Narratives of biorefinery innovation for the bioeconomy: Conflict, consensus or confusion? Environ. Innov. Soc. Transit. 2018, 28, 96–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siqueira, R.P.; Pitassi, C. Sustainability-oriented innovations: Can mindfulness make a difference? J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 139, 1181–1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, T.L. Dynamic Markets for Dynamic Environments: The Case for Water Marketing. Dædalus 2015, 144, 83–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calabrese, A.; Forte, G.; Chiron, N.L. Fostering sustainability-oriented service innovation (SOSI) through business model renewal: The SOSI tool. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 201, 783–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oskam, I.; Bossink, B.; de Man, A.-P. The interaction between network ties and business modeling: Case studies of sustainability-oriented innovations. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 177, 555–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schot, J.; Steinmueller, W.E. Three frames for innovation policy: R&D, systems of innovation and transformative change. Res. Policy 2018, 47, 1554–1567. [Google Scholar]

- Eteokleous, P.P.; Leonidou, L.C.; Katsikeas, C.S. Corporate social responsibility in international marketing: Review, assessment, and future research. Int. Market. Rev. 2016, 33, 580–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukman, R.K.; Glavic, P.; Carpenter, A.; Virtic, P. Sustainable consumption and production—Research, experience, and development—The Europe we want. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 138, 139–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van de Wetering, R.; Mikalef, P.; Helms, R. Driving organizational sustainability-oriented innovation capabilities: A complex adaptive systems perspective. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2017, 28, 71–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calabrese, A.; Castaldi, C.; Forte, G.; Levialdi, N.G. Sustainability-oriented service innovation: An emerging research field. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 193, 533–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panfilov, A.A. Features of Calculation Schemes and Methods for Design of Wind Turbine Foundations for Arctic Conditions. In Proceedings of the 2018 International Ural Conference on Green Energy (UralCon), Chelyabinsk, Russia, 4–6 October 2018; pp. 122–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vylegzhanina, A.O. Harakteristika sootvetstvija infrastruktury podderzhki innovacij prioritetam ustojchivogo razvitija obshhestva na primere tjumenskogo tehnoparka [Analysis of correspondence of innovation support infrastructure with priorities of sustainable development of society on the example of Tyumen Technopark]. Mezhdunarodnoe nauchnoe izdanie sovremennye fundamental’nye i prikladnye issledovanija 2016, 1, 87–96. [Google Scholar]

- Oslo Manual, 3rd ed.; OECD Publications: Paris, France; Available online: https://www.oecd.org/sti/inno/2367580.pdf (accessed on 10 January 2019).

- Vylegzhanina, A.O. Rezul’taty analiza benchmarketingovyh metodik ocenki innovacionnyh sistem na predmet sootvetstviya celyam ustojchivogo razvitiya obshchestva [The results of the analysis of benchmarking methods for evaluating innovative systems for compliance with the goals of sustainable development of society.]. MIR (Modernization Innovation Development) 2016, 1, 104–111. [Google Scholar]

- De Gregori, T.R. Resources Are Not; They Become: An Institutional Theory. J. Econ. Issues 1987, 21, 1241–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cancino, C.A.; La Paz, A.I.; Ramaprasad, A.; Syn, T. Technological innovation for sustainable growth: An ontological perspective. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 179, 31–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorek, S.; Spangenberg, J.H. Sustainable consumption within a sustainable economy—Beyond green growth and green economies. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 63, 33–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padilla-Perez, R.; Gaudin, Y. Science, technology and innovation policies in small and developing economies: The case of Central America. Res. Pol. 2014, 43, 749–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. Declaration on Science and the Use of Scientific Knowledge. In Proceedings of the World Conference on Science, Budapest, Hungary, 26 June–1 July 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Resolution adopted by the General Assembly on 25 September 2015. Available online: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/index.php?menu=2361 (accessed on 10 January 2019).

- Kemp, R.; Pearson, P. Final Report MEI Project about Measuring Eco-Innovation; UM MERIT: Maastricht, The Netherlands, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Huesemann, M.H.; Huesemann, J.A. Will progress in science and technology avert or accelerate global collapse? A critical analysis and policy recommendations. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daly, H.E. Ecological Economics and Sustainable Development, Selected Essays of Herman Daly; Edward Elgar: Cheltenham, UK; Northampton, MA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- The Concept of the Long-Term Tyumen Regional Development to 2020 and Prospectively—Till 2030. 2009. Available online: https://admtyumen.ru/files/upload/OIV/D_Economy/Документы/Концепция.pdf (accessed on 10 January 2019).

- Didenko, N.I.; Klochkov, Y.S.; Skripnuk, D.F. Ecological Criteria for Comparing Linear and Circular Economies. Resources 2018, 7, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Didenko, N.; Rudenko, D.; Skripnuk, D. Environmental security issues in the Russian Arctic. Int. Multidiscip. Sci. GeoConf. Surv. Geol. Min. Ecol. Manag. SGEM Albena 2015, 3, 267–274. [Google Scholar]

- Didenko, N.; Skripnuk, D.; Krasulina, O. Modelling the spatial development of the Russian Barents-Arctic. Region. SGEM Int. Multidiscip. Sci. Conf. Soc. Sci. Arts Sofia Bulgaria 2016, 5, 471–478. [Google Scholar]

- Didenko, N.I.; Cherenkov, V.I. Economic and geopolitical aspects of developing the northern sea route. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2018, 180, 012012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romashkina, G.F.; Didenko, N.I.; Skripnuk, D.F. Socioeconomic modernization of Russia and its arctic regions. Stud. Russ. Econ. Dev. 2017, 28, 22–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komkov, N.I.; Selin, V.S.; Tsukerman, V.A.; Goryachevskaya, E.S. Problems and perspectives of innovative development of the industrial system in Russian arctic regions. Stud. Russ. Econ. Dev. 2017, 28, 31–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leksin, V.N.; Profiryev, B.N. Socio-economic priorities for the sustainable development of Russian Arctic macro-region. Econ. Reg. 2017, 1, 985–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leksin, V.N.; Porfiryev, B.N. Evaluation of the effectiveness of government programs of socioeconomic development of regions of Russia. Stud. Russ. Econ. Dev. 2016, 27, 418–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Official Portal of Public Authorities of the Tyumen Region. Innovative Projects. Available online: http://admtyumen.ru/ogv_ru/finance/innovation/nov_projects.htm?f=1&blk=11045511 (accessed on 10 January 2019).

- Residents—West Siberian Innovation Centre. Available online: http://www.tyumen-technopark.ru/rezidenty (accessed on 10 January 2019).

- Tyumen Technopark Dataset. Contributor(s): Anastasia Ljovkina. Available online: http://dx.doi.org/10.17632/3c95r56fjg.1 (accessed on 10 January 2019).

- van der Vleuten, E. Radical change and deep transitions: Lessons from Europe’s infrastructure transition 1815–2015. Environ. Innov. Soc. Transit. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diethelm, J. Doughnut Economics: Seven Ways to Think Like a 21st Century Economist. She Ji: J. Des. Econ. Innov. 2016, 2, 349–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, G.M. On the cusp of global collapse? Updated comparison of the Limits to Growth with historical data. Gaia 2012, 21, 116–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konakhina, N.A. Evaluation of Russian Arctic Foreign Trade Activity. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2018, 180, 012018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzucato, M.; Perez, C. Innovation as Growth Policy: The Challenge for Europe. In The Triple Challenge for Europe; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fagerberg, J. Mobilizing innovation for sustainability transitions: A comment on transformative innovation policy. Res. Policy 2018, 47, 1568–1576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geels, F.W. Processes and patterns in transitions and system innovations: Refining the co-evolutionary multi-level perspective. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2005, 72, 681–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markard, J.; Raven, R.; Truffer, B. Sustainability transitions: An emerging field of research and its prospects. Res. Policy 2012, 41, 955–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Typological Characteristics | Types of Innovations by the Scale of SD Effects | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Strategic | Tactical | Operative | |

| The level and complexity of innovations’ effects | System transformative effects | Some integrative effects | Immediate single effects |

| The quality of problem solution | Eradicating the radical SD problems through eliminating their causes | Preventing some consequences of SD problems (or derivative SD problems) | Alleviating consequences of SD problems |

| The extent of influencing the problem situation | Radical societal transition to SD path | Noticeable improvement of the global situation in SD context | Insignificant surface improvements |

| Time frames of effects | Long-term | Mid-term | Short-term |

| The scale of SD Innovation Effects | SD Ethics Dimensions | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Environmental | Social | Economic | |

| Strategic | Strategic environmental innovations (SEnI) | Strategic social innovations (SSI) | Strategic economic innovations (SEI) |

| Tactical | Tactical environmental innovations (TEnI) | Tactical social innovations (TSI) | Tactical economic innovations (TEI) |

| Operative | Operative environmental innovations (OEnI) | Operative social innovations (OSI) | Operative economic innovations (OEI) |

| SD Ethics Dimensions | The Scale of SD Innovation Effects | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Environmental | Social | Economic | ||||

| 2009–2015 | 2016–2017 | 2009–2015 | 2016–2017 | 2009–2015 | 2016–2017 | |

| Strategic | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 1 |

| Tactical | 13 | 4 | 2 | 8 | 14 | 9 |

| Operative | 2 | 9 | 1 | 15 | 14 | 39 |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ljovkina, A.O.; Dusseault, D.L.; Zaharova, O.V.; Klochkov, Y. Managing Innovation Resources in Accordance with Sustainable Development Ethics: Typological Analysis. Resources 2019, 8, 82. https://doi.org/10.3390/resources8020082

Ljovkina AO, Dusseault DL, Zaharova OV, Klochkov Y. Managing Innovation Resources in Accordance with Sustainable Development Ethics: Typological Analysis. Resources. 2019; 8(2):82. https://doi.org/10.3390/resources8020082

Chicago/Turabian StyleLjovkina, Anastasia O., David L. Dusseault, Olga V. Zaharova, and Yury Klochkov. 2019. "Managing Innovation Resources in Accordance with Sustainable Development Ethics: Typological Analysis" Resources 8, no. 2: 82. https://doi.org/10.3390/resources8020082

APA StyleLjovkina, A. O., Dusseault, D. L., Zaharova, O. V., & Klochkov, Y. (2019). Managing Innovation Resources in Accordance with Sustainable Development Ethics: Typological Analysis. Resources, 8(2), 82. https://doi.org/10.3390/resources8020082