Abstract

Forest management in Indonesia has not yet been able to realize the constitutional mandate which was followed by uncontrolled forest destruction. Implementing a good forest government system is necessary. Therefore, it is essential to give indigenous peoples the authority to play a more critical role in forest management in the future. This study aims to find a form of sustainable forest management and sanctions for the perpetrators of forest destruction based on Dayak Kotabaru’s indigenous people. This study uses the normative juridical method that focuses on data in the form of primary, secondary, and tertiary legal materials. While the objectives of this study are to review and describe the problems due to the absence of legal protection for customary rights, we also examine the extent of forest management by the Dayak Kotabaru’s customary law and seek to formulate forest management solutions in Indonesia based on the local culture as a prescriptive future policy. The results of this study indicate that a large amount of permits, given by the government to the private sector for forests in possession of indigenous peoples, are overlapping and as a result have increasingly marginalized the indigenous community and acted as a drawback to development. Forest management through the local culture, such as the Bera system in Dayak Kotabaru, can be beneficial for the local community, because locals will enjoy the production of farms and gardens, the soil will be naturally fertile because of a four year interlude, and the forest will remain sustainable as less forest area is cut down.

1. Introduction

Indonesia is a sovereign country with vast forest resources. Thus, it is important for Indonesia to have a concept of forest governance that matches the forest tenure ideology in article 33, paragraph (3) of the 1945 Constitution which states that: “Earth, water and natural wealth contained therein is controlled by the state and used for the greatest prosperity of the people” [1]. Based on these provisions, it can be concluded that the state controls the natural resources, but that this control must be used for the greatest prosperity of the people [2]. The existence of government control shows that Indonesia still adheres to the concept of the welfare state as stated by Jimly Assidiqie: “The 1945 Constitution in addition to being a political constitution is also an economic constitution. One of the important features as an economic constitution is that the 1945 Constitution contains welfare state ideas.” [3].

However, forest management in Indonesia still does not reflect compliance with good forest governance, leading to deforestation and local people becoming unprosperous. Legally, forest management is based on the 1945 Constitution of Indonesia, Law No. 41/1999 on Forestry, and Law No. 18/2013 on Prevention and Eradication of Forest Destruction which have regulated an excellent concept of forest management. The idea of natural resources being controlled by the state for the greatest prosperity of the people is far from being achieved. In practice, there are many irregularities which have resulted in a gap between “das sollen” (ideals) and “das sein” (reality). Additionally, some of the problems often encountered are inaccurate maps and a lack of clarity over customary land.

Furthermore, the analysis of BAPPENAS (Ministry of National Development Planning) on fundamental issues in the Indonesian forestry sector demonstrates poor governance. Spatial planning which is out of sync between the central and regional levels, lack of clarity on tenure rights, and weak capacity in forest management (including law enforcement) are fundamental problems of forest management in Indonesia that leads to the destruction of forest resources [4].

In reality, it is necessary to implement a new forest management system by adopting the values of customary law. Data from the World Resources Institute and Global Forest Watch show that more than 50% of forest loss occurs within the concession area, where forest utilities are allowed to a certain extent according to the permit. These data prove that the rate of deforestation is the result of forest utilization activities by mining companies and the violation of forest utilization permits. Furthermore, the common problem of forest management in the world today is that the forestry policies that favor and benefit companies often violate local community rights. This is shown in one of the latest studies by Antonio and Griffith-Charles that reviews communal tenure and land reform mechanisms for optimizing economic and social outcomes for countries where this type of tenure predominates. They studied the experiences of two land groups, the Orogwangin and the Polulve Mahevie. Their research shows that the narrow legal reform mechanisms distort customary/communal practices, forcing conflicts and subsequent subdivisions of groups in some instances. The lack of capacity of state institutions to service the new requirements for maintaining the record of group characteristics is notable as well. Vulnerable groups are left to negotiate with powerful business entities for appropriate terms and compensation for the use of their land [5].

Therefore, the management of local forests in customary lands must be returned to indigenous peoples who do have the constitutional rights to manage and use it according to its function. In Indonesia, legal breakthroughs are essential; law enforcement is not only to reform the law or the legal substance, but also to reform the legal structures and legal culture [6]. Furthermore, it is important to review whether the use of customary law and local culture in forest management, such as Dayak Kotabaru, is practical and applicable for a sustainable future in Indonesia.

Another successful case study in Indonesia by Nugroho, Anne van der Veen, Skidmore, and Hussin explored adat forests in the Kandilo Subwatershed, East Kalimantan, Indonesia. They conducted a case study in the Kandilo Subwatershed using mixed methods, including image interpretation, spatial modeling, and sociocultural surveys, to examine the interrelationships between physical conditions, community characteristics, and traditional land-use expansion. The study also investigated community characteristics through household interviews, communication with key informants, and discussions with focus groups. By using an area production model, they were able to analyze the effect of improved farming systems, policy intervention, and law enforcement on traditional land-use expansion and deforestation. Based on the examination of 20 years of traditional land-use activities in adat forests, the evidence indicated that the steeper the slope of the land and the farther the distance from the village, the lower the rate of deforestation. This study also found that customary law, regulating traditional land-use, played an essential role in controlling deforestation and land degradation (see Figure 1). We conclude that the integration of land allocation, improved farming practices, and enforcement of customary law are effective measures to enhance traditional land productivity while avoiding deforestation and land degradation [7].

Figure 1.

Positive impact on traditional land used in the Kandilo Subwatershed [7].

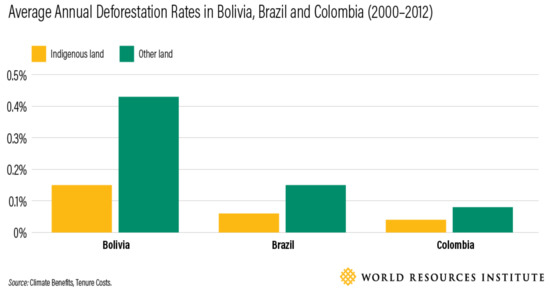

Concerning the effectiveness of forest resources protection managed by indigenous peoples, we used the World Resource Institute study to compare the efficacy of using customary law in forest management in Bolivia, Brazil, and Columbia. Based on these data, forest management in the secure lands of indigenous peoples runs effectively compared to forest management outside the customary sphere. During 2000−2012 the average rate of deforestation decreased significantly (see Figure 2). Standing at the top position, Bolivian indigenous people were even able to reduce the deforestation rate to 2.8× lower than conventional management.

Figure 2.

Forest management in tenure-secure indigenous lands [8].

Thus, we studied the Dayak Kotabaru customary law. Dayak Kotabaru was chosen as the subject of this research for some considerations, namely:

- Their tradition is still active, and the system of communal rights is implemented;

- It has strong economic ties between the community and the forest;

- It is an area with strong economic development;

Furthermore, this study aims to review and describe the problems that arise as a result of the absence of legal protection for indigenous peoples in customary forests in communal lands. In addition, this study aims to examine the extent of forest management by the Dayak Kotabaru customary law to prosper the local community. Moreover, this research seeks to formulate forest management solutions in Indonesia based on local culture as a prescriptive future policy to maintain the sustainability of forest for the locals.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Methods

The method used in this study is normative legal research. This particular method was chosen because the objects of the study are the legal principles, rules, theories, and doctrines of legal experts. Peter Mahmud Marzuki explains that normative legal research is:

“... a process to find the rule of law, legal principles, and legal doctrines to answer the problems of law. ... Normative legal research is conducted to produce new arguments, theories or concepts as prescriptions in solving problems.”[9]

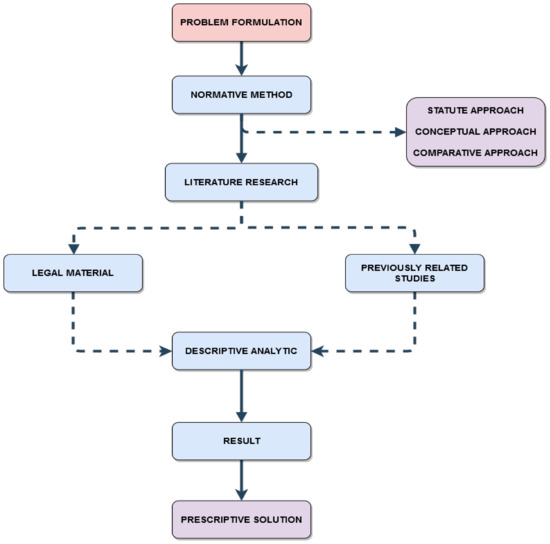

This research was conducted to develop new arguments, theories and concepts of forest management based on Dayak Kotabaru local culture compared to national laws to implement the idea of norms (see Figure 3). It primarily aims to create an understanding of binding legal material such as legislation and court decisions, and non-binding laws, such as code of conduct, guidelines, social ethics and common values [10].

Figure 3.

Methodology.

2.2. Legal Material

Furthermore, this research is focusing on secondary data in the form of primary, secondary and tertiary legal material. Meanwhile, the research specifications used descriptive analytic that describe the provisions, norms and legal principles applicable to obtain a comprehensive and systematic, factual, and accurate picture of the aspect of forest management in Dayak Kotabaru [11]. For legal materials, the analysis was carried out qualitatively, meaning it was conducted without using numbers, statistical formulas, and mathematics. The materials used in this study consist of primary legal material, secondary legal material and tertiary law material related to the issues.

Primary legal materials comprising of legislation in Indonesia on forest management and customary law are as follows:

- 1945 Constitution of the Republic of Indonesia;

- Law No. 41/1999 on Forestry; State Gazette No. 167/1999; Additional State Gazette No. 3888; and

- Law No. 18/2013 on Prevention and Eradication of Forest Destruction; State Gazette No. 130/2013; Additional State Gazette No. 5432.

Secondary legal materials use books, research findings, scientific journals, and published papers. The sources of secondary legal materials include material as they contain references. Meanwhile, tertiary legal material is a material that can explain both primary and secondary legal material in the form of law dictionaries and encyclopedias.

2.3. Legal Analysis and Approach

The collected material was analyzed using descriptive qualitative language to describe the current regulations and the legal document was reviewed to answer the problems as referred to in the formulation. Moreover, to sharpen the study, there were several approaches used in this research, namely:

- Statute approach was carried out by reviewing the 1945 Constitution of the Republic of Indonesia, Law No. 41/1999 on Forestry, and Law No. 18/2013 on Prevention and Eradication of Forest Destruction. This approach sought to uncover the interpretation of the statutory texts, both grammar and meanings.

- Conceptual approach was carried out by understanding and reviewing the principles, doctrines, theories and legal philosophies of forestry law and the Dayak Kotabaru customary law [12].

- Comparative approach was carried out by comparing a national law with other ones. In this case, we used a comparison between the Dayak Kotabaru customary law to the Law No. 41/1999 on Forestry, and Law No. 18/2013 on Prevention and Eradication of Forest Destruction in Indonesia. It was used to find differences and marked similarities regarding the principle of sustainable forest management [13].

3. Legislative Review

Indonesia is a state which is based on the rule of law (hereinafter, it will be referred to as the State of Law) as stipulated in Article 1 (3) of the 1945 Constitution of the Republic of Indonesia. The implication of the State of Law (Staatrecht) is that we must actively strive for prosperity and fairness for the peoples in a balanced way, without any exception. The concept of state obligations in providing welfare is a state of the law in the real perspective (material social-service state), which is often known as a type of modern state of law. By this doctrine, the objective of the country is to bring prosperity to all the people [14]. Therefore, the management and control of the forest are carried out by the Government. It aims to improve the effectiveness and efficiency of government as well as an extension of the 1945 Constitution which mandates the state control over natural resources (Article 33 (3) of the 1945 Constitution).

In addition, Article 33 (5) advocates the further provisions relating to the implementation of the national economy and social welfare shall be governed by the law. Thus, forest management has been governed by several laws since 1967. These policies have undergone several improvements based on the development of social, economic, political, cultural, and defense conditions of Indonesia. These developments can be seen in the following Table 1:

Table 1.

Forest legislative development.

Despite several changes in forestry policies in Indonesia, there are still some shortcomings related to the status of forest management rights communally. The acknowledgment of customary rights in the 1945 Constitution of the Republic of Indonesia is based on Article 18B paragraph (2) that determines:

“The State shall recognize and respect, to be regulated by law, the homogeneity of societies with customary law along with their traditional rights for as long as they remain in existence and complying with societal development and with the principle of the Unitary State of the Republic of Indonesia.”

The Constitution acknowledges the existence of customary law, however, there is no further regulation related to this provision. Controls on customary rights are only partially regulated as an ownership status as stipulated in Law No. 5/1960 on Basic Agrarian Principles related to land rights and Law No. 41/1999 on Forestry regulating state of forestry. Moreover, legal protection and customary forest management are still not procedurally governed and without the establishment of a clear map on customary forestry. Therefore, it leads to overlapping rights between indigenous peoples and companies that obtain the permits by the government. Thus, in this case, there is a need for mechanisms related to customary forest management. Because, without the procedural regulations on the management of customary forests, it has implications for the absence of formal legal protection (rights on paper such as permits or certificates). As a result, it causes the lack of supporting evidence of their customary rights if facing the case of overlapping forestry rights. Unlike the lack of protection on customary rights, private companies can apply for forest area utilization permits that strengthen their legal standing.

These government policies that tend to “take sides” in the permit system in favour of the company is an indication of doctrine by Hans Kelsen stating that the rule of law is a “command of the sovereign” or interpreted as the will of the authorities. This doctrine is in line with Merkl stating that a legal norm always has two faces (das Doppelte Rechtsantkizt) [15]. Then, it can be understood that various interests always accompany legal policy as a product of politics carries in both the economic and governing aspects. Thus, the customary rights are often overlooked, because the impact of this traditional device cannot be assessed directly and often given the perception that the communal is a backward society, that customary law is inferior in terms of quality compared to positive law. Meanwhile, in reality, legal developments tend to lead to the concept of restorative as first used by indigenous peoples.

4. Results and Findings

4.1. The Problems in Current Forest Management

The protection of forestry must be maintaining balance in biodiversity. The principle of biodiversity protection is a prerequisite for the success of the inter-generational equity principle. It is also related to the prevention of species extinction from biodiversity [16].

Indonesia is a state of law. The concept of law, regulations, and policies are essential to maintaining security, order, and protection for the people. In general, the state views forest management based on status and functions. The issuance of the Constitutional Court Ruling Number 35/PUU-X/2012 strengthened the position of indigenous peoples. It regulates three types of forests based on their status, namely:

- State forest, i.e., forests in which the lands are not burdened with private ownership rights. This forest ownership belongs to the state. Thus, all types of ownership and management must be authorized by the state.

- Rights/Private forest is located on lands which are burdened with ownership rights. The ownership of these rights can be in the hands of individuals or legal entities.

- The customary forest is a forest in the territory of customary law communities.

Furthermore, the forest function is more related to how the forest is managed to maintain sustainability for the prosperity of the people. The distribution of forest areas, based on their functions with specific criteria and considerations, is stipulated in Government Regulation Number 34/2002 on Forest Arrangement and Preparation of Forest Management Plans, Forest Utilization and Forest Area Use regulated in Article 5 paragraph (2), as follows:

- Conservation Forest Area consists of nature reserves (nature reserves and wildlife sanctuaries),

- Nature Tourism Areas (National Parks, Great Forest Parks, Nature Tourism Parks, and Hunting Parks).

- Protected Forest; and

- Production Forest.

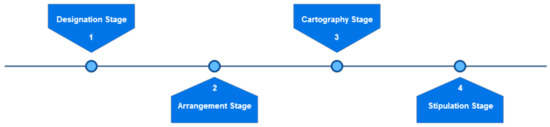

The separation of forest functions is intended to make the management adjustable to its designation. Then, to determine the legal status of the forest area, it is done through the inauguration. There are four stages in conducting forest inauguration, namely: The designation stage, the arrangement stage, the cartography stage, and the stipulation stage (see Figure 4). The inauguration is a significant momentum in determining the legal status of forestry. The decree of the Minister of Forestry divided the legal status of forest areas, whether protected forests, production forests, nature reserves, or tourism forests. In addition, it also covered the area, boundaries, and location of forest areas.

Figure 4.

Forest inauguration steps [17].

In the Elucidation of Article 15 paragraph (1) of Law Number 41/1999 on Forestry, it is stated that the designation of forest areas is an activity to prepare for the inauguration of forestry, namely:

- Creating a referral designation map on the outer boundary,

- designing temporary borders and passages,

- making boundary trenches in vulnerable locations, and

- announcing planned boundaries of forest areas, especially in places near private land.

Therefore, in determining the inauguration of the forest area, it still refers to the local spatial planning. To streamline the implementation of forestry planning, the activities that are most closely related to the planning are activities to designate forestry areas. However, the establishment of forest boundaries is a challenge in the forestry sector, and it continues to undermine the benefits for people from the forest. As a result, it will affect;

- the level of deforestation;

- state financial losses in the forestry sector;

- legal uncertainty over forest areas caused by overlapping permits (agrarian disputes, overlapping gardens, mines that are not clean and clear).

- the welfare of indigenous peoples.

Based on the objectives of regulating forest areas, shifting in the status and function of forest has several implications. The jurisdiction of forestry is determined by the legal boundaries of the area, which is also one of the most crucial challenges. Until today, the condition of forest areas in Indonesia could be categorized into several levels, including unregulated forest areas, regulated forest areas but are still in the process of ratification and stipulation, forest areas that are partially legalized by the Minister of Forestry, and forest areas stipulated by the Minister of Forestry. These conditions contain legal consequences for the existence of the forest area.

The activities in the forest are diverse such as opening and cultivating, plantations, fisheries/aquaculture, food crop farming, road construction, village/city expansion, and so on. This condition contributes to the worsening of the forest areas; in de jure, the state controls the forest, but in de facto, people live from generation to generation and depend on their lives in forests and its products. The issue of forestry lies in the matter of tenure where the forest grows and resides, rather than in the forest resources. In reality, a forest area is an area including the land along with the resources contained in it. The land is an important subject that often becomes a basis for conflict among stakeholders [18].

The lack of transparency in the permission process is a common problem in Indonesia, whereas transparency is a key element for making and implementing a reasonable regulation in forestry [19]. Thus, the risk of corruption increases, where bribes are paid for issuing permits without following proper procedures. The modus operandus is to convert the forest area into plantation areas such as palm oil and others. In addition, lack of transparency decreases the ability of common peoples or Non-Government Organizations (NGOs) to participate in monitoring land allocation and use. Information about permit applications and land allocated for permission are also not available for the public.

Based on the study of the Corruption Eradication Commission (hereafter referred to as KPK (Komisi Pemberantasan Korupsi)), it was found that the cases of corruption in granting permits to convert forest functions was often carried out before the regional election. Towards regional elections, regions with vast natural resources easily issue their permits. This study showed that the authority of the region concerning natural resource management is very prone to corruption. This system of local autonomy has resulted in several delegations of powers to the regions. Thus, the regent, mayor or governor has authority which was once controlled by the central government. The regional head can abuse this authority for self-enrichment and also, even though there is no direct empirical data, it is closely related to the political process in the elections.

4.2. The Overview of Dayak Kotabaru as a Customary Law Community

Indonesia is a complex nation, the motto of “Bhinneka Tunggal Ika” is a form of respect and appreciation of the philosophy of the Indonesian country of its diversity. This diversity can be seen in the existence in different groups of indigenous peoples. However, unfortunately, the presence of customary law as Indonesian living law became increasingly abandoned [20]. Empirically, many problems arise when indigenous peoples face the provisions of customary law and positive law, for example when the traditional rights of society are faced with the interests of companies with powers given by state law [21].

Article 2 paragraph (4) of Law No. 5/1960 on Basic Agrarian Law (hereafter referred to as UUPA) stipulates that the State’s right of control above its implementation may be authorized to the Swatantra regions and customary law communities, as necessary and not contrary to the national interest, which is in accordance with the provisions of Government Regulation. This arrangement is the basis for ulayat land management. UUPA does not define what ulayat land means. In Article 3 of the UUPA, there is a term “the ulayat rights and other similar rights.” In the explanation of Article 3 of UUPA, it is explained that what is referred to in customary law as “beschikkingsrecht.” The complete Article 3 of UUPA is as follows:

“In view of the provisions contained in Articles 1 and 2, the implementation of the ulayat rights and other similar rights of customary law communities—as long as such communities in reality still exist—must be such that it is consistent with the national interest and the State’s interest and shall not contradict the laws and regulations of higher levels.”

The definition of Ulayat Land is described in Minister of Agrarian Regulation No. 5/1999 on the Guidance on the Settlement of the Indigenous People’s Rights Problem. It is stated that Ulayat Land is a part of the land on which there are customary rights of a specific customary law community. Meanwhile, indigenous and tribal peoples are a group of people who are bound together by their universal order as citizens because of the similarity of residence or from descent. Moreover, Putu Oka Ngakan [22] defined ulayat right (collective right/beschikkingsrecht) as “land which is controlled jointly by indigenous and tribal peoples, where the management is carried out by the chief of adat (customary chief) and their utilization is intended for both indigenous and tribal peoples.”

Thus, the tenure rights over customary land are known as Ulayat Rights. Meanwhile, ulayat right is a series of authority and obligations of a customary law community related to land located within its territory. Furthermore, the requirements to be fulfilled as customary rights under Article 3 of UUPA are:

First, “As long as such communities in reality still exist”. Regarding this, following the explanation of Article 67 paragraph (1) of Law No. 41/1999 on Forestry, an adat law community is recognized, and Dayak Kotabaru is fulfilling the requirement elements:

- The Dayak Kotabaru tribes are still in the traditional form;

- Dayak Kotabaru have an institution in the form of traditional ruling device, i.e., “Kepala Adat”;

- Every one of Dayak Kotabaru’s communities have their own form of customary law jurisdiction;

- They have institutions and legal instruments in the form of “Balai Adat” and “Perangkat Adat”; and

- They still collect forest products in the surrounding forest areas for daily needs.

The indigenous people (Dayak tribe) generally are farmers who live in groups in a traditional residential area with Balai Adat as the center (see Figure 5), so that each traditional residential area stands for Balai Adat which does not only function as a ritual and ceremonial place but also acts as a Traditional Justice Court.

Figure 5.

Balai Adat as Dayak Kotabaru’s traditional institutions and legal instruments.

Second, “Must be such that it is consistent with the national interest and the State’s interest”. Since the statement “consistent with the national interest and the State’s interest” can lead to multiple interpretations and be full of political interests, it will be challenging to be able to determine whether the existence of a particular customary law community meets these requirements or not. However, we believe that Dayak Kotabaru’s society is not contrary to national interest.

Third, “Shall not contradict the laws and regulations of higher levels”. The Constitution has firmly acknowledged the existence of the traditional rights of communities in Indonesia. Article 18B paragraph (1) of the Constitution states that the State recognizes and respects the unity of customary law community with its traditional rights as long as it still exists and is under the development of society and the principle of the Unitary State of the Republic of Indonesia. Thus, if there is a law that does not recognize the existence of the traditional rights of the community, it is contrary to the Constitution.

4.3. The Extent of Forest Management in Customary Law to Provide Livelihood for the Local People of Dayak Kotabaru

The management of forest areas is very closely related to land tenure rights. For the Dayak Kotabaru community, every single family, in general, has private land of residential and yardland, garden land, and farmland/ex-farmland. Housing and yard are the lands on which the house stands as a place to live for one family, and in fact, one building is often used as a place of residence for more than one family. Garden land includes rubber gardens and orchard fruits; farmland is used as a farm; while ex-farmland is a land that is left for a relatively long time so that it becomes shrubs with the intention of giving an opportunity for the land to be able to naturally restore its fertility so that it can be used as a farmland again.

Besides, there are also lands which are explicitly not under individuals’ control. These lands can be forest areas, including specific areas which are considered by the community as sacred. Therefore, in terms of managing the forest, the Dayak Kotabaru people tend to have awareness and compliance to preserve the forest because they believe that if it is violated, there will be a disaster. One prominent example is the belief of the Dayak tribe in the village of Limbur, Hampang Subdistrict, that there is a prohibition for local people to carry out any activities within the Gunung Kelawang forest area. They still obey this prohibition until today. Sacred places are usually those that are considered by the community as the burial places of their ancestors.

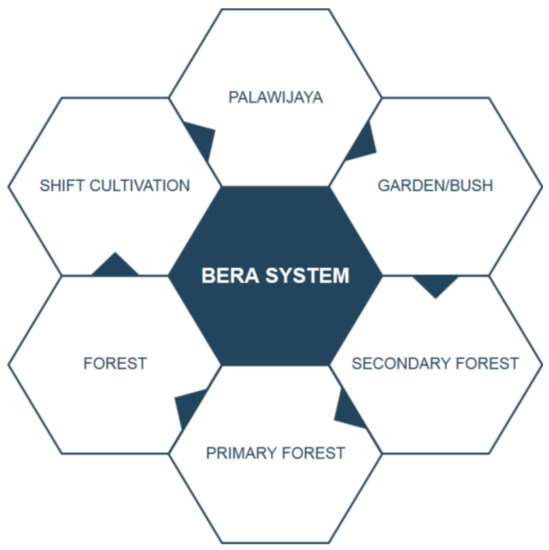

Furthermore, farming is the main livelihood of the Dayak tribe in general. It is a hereditary tradition that has been integrated into their cultural system. Their farming system is using shifting cultivation. With such a cultivation system, farmland is first obtained through cutting and burning forest (primary) which is then planted with various commodities, mainly rice, and so on (see Figure 6). Therefore, there is often an assessment that their activities have been considered as the cause of forest destruction. Meanwhile, the shifting cultivation they did was not in a sense of opening and burning primary or secondary forest from one place to another continuously. They have developed a concept called the “Bera System” as their law and local culture. This system is intended to give time and opportunity for ex-farm lands to naturally restore their fertility for at least four years [23].

Figure 6.

Bera System of Dayak Kotabaru.

The use of the Bera System has implications for the creation of a cycle of land that has been designated as a plantation (see Figure 7 and Figure 8). It is different from the forest conversion system in Forestry Law with a permits system as in practice; there is often a mismatch between legal ideals and reality. Moreover, behind this system, there is a substantial background on why Dayak Kotabaru tribes have a culture to maintain their forest and use it wisely. For them, land and forests are not only appraised based on economic value but also have religious–magical values as some forests and mountains are considered sacred related to their ancestors.

Figure 7.

Primary and secondary Forest.

Figure 8.

Garden/bush, palawijaya, and cultivating area.

The Dayak Kotabaru public forest management is in line with the sustained yield doctrine of forest management based on ‘forestry ethics’ which avoid unilateral and exclusive benefits and understand that forests are important for human life. The theory of sustained yield obscures preserved forest function for public goods and services with forests that can be owned privately or communally, where decisions are made to use the forest either as individual or group choices. As a result, forest preservation is mandatory for forest owners with various regulations.

One of the examples of sustained yield is forest management in Finland. Most of the Finnish forest owners are private owners. While, 62.2% of the private forest holdings is 5–100 ha. In southern Finland, private owners own 73.5% of the forested area, companies own 12.2% and the state owns 8.2%. In northern Finland, the state owns 54.6% of the forest, but more than half of the area is in scrubland. Private owners own 37.1% and companies own 4.2%. This regulation dismisses a political authority of the State to control every natural resource and gives a mandate to privates. We are, however, considering the bureaucracy and the increasing number of corruption cases in the natural resources sector in Indonesia, arising a doubt in this concept to be implemented in Indonesia.

Hence of that bureaucracy and political issues, the concept of forest management should be more involving of communal people. This concept arises a discourse in line with the doctrine of sustained yield as one of the objectives of scientific forestry by questioning, “is increasing the role of communal groups in managing customary forest as their human right and constitutional right able to reduce conflict, create sustainable forest management, or reduce open access of forest areas in Indonesia?”. To answer this question, based on a Bera system study as explained earlier, it shows that the use of the local culture system of the Dayak Kotabaru communal believes that the forest has a magical value that needs to be respected by preserving forests’ sustainability. In addition, some literature and previous research have proven the positive results of indigenous tenurial rights on forest management as outlined as follows:

In 1990, Cramb and Wills wrote “The role of traditional institutions in rural development: Community-based land tenure and government land policy in Sarawak, Malaysia.”. The research was performed on the ground that traditional local-level institutions are frequently considered obstacles to rural development. Therefore, attempts are made by the state to impose “dissonant” institutional forms from above. In contrast, the result of research argues that traditional institutions should be viewed as the building blocks of a modern, development-oriented institutional structure. The argument is applied to the case of the Iban system of community-based land tenure and its relationship with government land policy in the Malaysian state of Sarawak [24].

While in 2014, Robinson, Holland, and Naughton-Treves wrote a paper entitled “Does secure land tenure save forests? A meta-analysis of the relationship between land tenure and tropical deforestation”. Their study used the method to review literature that connects forest outcomes and land tenure to better understand broad interactions between tenure form, security and forest change. Papers from economic theory suggest that tenure is embedded in a broader socioeconomic context, with the potential for either a positive or negative conservation impact on forested land. Empirically, they found 36 publications that link land cover change to tenure conditions while controlling for other plausibly confounding variables. Publications often investigate more than one site and more than one form of tenure. Thus, from these, they derived 118 cases related to forest change with a specific tenure form in a particular location. From these cases, they found evidence that protected areas are associated with positive forest outcomes and that land tenure security is associated with less deforestation, regardless of the form of tenure. The researchers conclude with a call for more robust identification of this relationship in future research, as well as set of recommendations for policymakers, particularly as forest carbon incentive programs such as Reduction of Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation (REDD) is integrated further into national policies [25]. Therefore, as a preventative attempt, forest management through tenure right of communal groups has been proven to be successful. In addition to the Bera system as a preventative effort for deforestation, the Dayak Kotabaru people have repressive measures to punish the perpetrator of forest destruction or even a violation of their customary law.

As repressive measures, the punishments for perpetrators of forest destruction are still applied to the principles of customary law as well as resolving other disputes that occur within the community, with payment of fines called Tahil. Therefore, Tahil is a calculation to determine sanctions for those declared guilty by the custom. One Tahil equals 8/16 plates or bowls according to the Dayak community. In Dayak communities, bowls and plates are interpreted as a treasured item. The same fines are also applicable to those who violate customary laws such as fighting, murder, theft, adultery, etc. Thus, it can be seen that sanctions for perpetrators of forest destruction is more emphasized on compensation than administrative (prohibition or limitation on forest use) or criminal sanction.

While in the Indonesian legal system, the regulation on forestry is administrative penal law and there are two laws concerning forestry sanctions directly, namely: Law No. 41/1999 on Forestry and Law No. 18/2013 on Prevention and Eradication of Forest Destruction. In Law No. 41/1999 on Forestry, it regulates the provision of sanctions on civil, administrative, and criminal penalties. The civil sanction is applied under a general or class action lawsuit if an act is deemed to be detrimental to the plaintiffs. The administrative sanctions are given to holders of forestry permits that violate their permits. There are five types of administrative penalties for permit holders of forest utilization namely: (1) Temporary suspension of administrative services; (2) temporary suspension of field activities; (3) administrative fine; (4) reducing the production quota; (5) revocation of permit.

Furthermore, criminal provisions as stated in Law No. 41/1999 on Forestry are limited to unauthorized use of forest and forest protection with prevention efforts and the welfare of plants and animals. Meanwhile, Law No. 18/2013 on Prevention and Eradication of Forest Destruction regulates the prohibition, criminal sanctions, and institutions explicitly to prevent forest destruction. This law governs the expansion of criminal acts in forestry covering corporate crime, organized forest destruction, even abuse of authority by officials. The penal policy of this law is contained in articles 11 until 28. Therefore, the criminal sanction in forestry has become more functional.

Provisions on forest violations as stipulated in Law Number 41/1999 on Forestry show that the criminal regulation is limited to the use of forests without permits and forest protection with prevention efforts, as well as the welfare of plants and animals. Meanwhile, Law Number 18/2013 on Prevention and Eradication of Forest Destruction specifically regulates prohibitions, criminal sanctions, and institutions to prevent forest destruction.

In addition, the Law Number 18/2013 regulates the expansion of criminal acts in the forestry sector involving corporate crime, organized forest destruction, and even abuse of authority by officials. Therefore, the penal law has become more functional today. Thus, it can be concluded that the penal policy in the forestry sector has been developed significantly. The criminal regulation in Law Number 41/1999 was limited to illegal forest area use and forest destruction; since in the beginning, the Forestry Law regulated governance forests in Indonesia and only used penal law as a tool in forestry law enforcement. Then, the enactment of Law No. 18/2013 provides legal certainty by extending its provisions to the domain of permit and document forgery, regulating organized forest destruction, corporate crime and abuse of authority by officials [26].

5. Discussion

The recognition of the customary law of indigenous peoples can be seen from Indonesian legal politics stipulated in the 1945 Constitution of the Republic of Indonesia. Article 18B paragraph (2) states: “The state recognizes and respects the customary law communities and their traditional rights as long as they are alive and in accordance with community development and the principles of the Republic of Indonesia which are regulated in the law”.

However, in its development, Indonesian law tends to move more towards western law (civil law and common law) which has implications for Indonesian legal politics to deny customary law, which is more relevant. For example, resolving disputes between indigenous peoples in one area should be addressed through the role of adat institutions rather than district courts [27]. The crucial problem that arises due to the overriding of customary law is that there is a conflict between land ownership by adat community based on customary rights and the public interest which is an obligation of the State [28].

Recognition of customary law shows the right of communal groups to manage and control forests collectively for the common interests [29]. The customary ownership system is also recognized with the attributes of social, mystical and religion which are inherent in customary land. For decades, the problem in the forestry policies as interests of the state for the welfare of its people is that it is often violating the customary rights as a result of interest and regulation conflicts. Thus, based on the problems outlined earlier, several essential steps can be formulated towards effective forest management, namely:

- The need for harmonious regulation;

- The need for strengthening law enforcement;

- The need for legal certainty of forestry status;

- The need for conflict resolution in the concept of forest control;

- The need for maps of customary forest area;

- The need for resolving forestry and agrarian conflicts.

- The need for supervision on overlapping forest utilization permits.

Thus, in this case, several important things that need to be done in forest management are to designate a map of customary forest areas where the management and control of forests in communal tenure land are given entirely to indigenous peoples. Then, the status and inauguration of customary forests must be clarified and published so that there is no overlapping of company permits in customary forests. In addition, the harmonization of the Ministry of Forest policies in designation forest areas must be harmonized with spatial planning in each region.

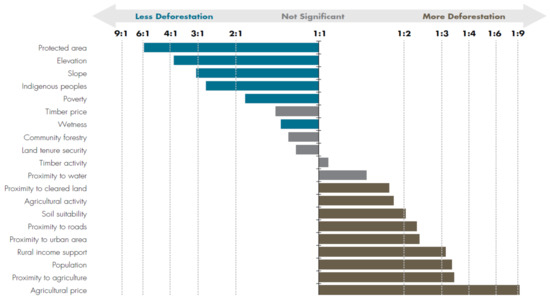

The control of forests by communal tenure has proven to have a positive impact in several studies. In addition, based on a meta-analysis by the Center for Global Development (CGDEV), one of the critical factors that reduces deforestation is indigenous people (see Figure 9). The CGDEV further states that “Indigenous peoples are consistently associated with low deforestation in both low and high levels of baseline threats.” [30].

Figure 9.

What drives deforestation and what stops it? A meta-analysis [30].

The complexity that occurs in the management of forest areas is in fact, which is in terms of determining policy choices, to reduce or override corporate interference in the land of indigenous peoples. A large amount of overlapping of permits given by the government to the private sector for the forests in possession of indigenous peoples has increasingly marginalized indigenous communities as a drawback of the development. This is because the formal verification system often favored permits as proof of the existence of stakeholder’s rights, while the indigenous people indeed did not have written documents on the forest. Therefore, this condition certainly makes it difficult for the forestry apparatus and law enforcement officials to completely resolve violations of customary forest rights. On the one hand, there needs to be a policy towards the establishment of customary forests that can provide certainty and favors the locals. Furthermore, the forest management through local culture such as the Bera system in Dayak Kotabaru can be used for the benefits of the local community. Local people will enjoy the production of farms and gardens while the soil will be naturally fertile because of four years interlude and the forest will maintain sustainability through less cutting down of forest area.

As for future policy, any prosperous province should finance performance-based payments to forest management for reducing emissions from deforestation and degradation. The Central Government can propose an approach for customary forests and their community by consulting with the chief of local communities and providing their rights, including their economic growth through forest utilization.

6. Conclusions

From the results of this study, the conclusions can be drawn as follows:

First, the establishment of forest boundaries is a challenge in the forestry sector that continues to undermine the benefits for people from the forest. Whereas, the lack of transparency in the permission process is a common problem in Indonesia. Thus, the risk of corruption is increasing, where bribes are paid for issuing permits without following proper procedures. Furthermore, the complexity that occurs in determining policy choices has reduced or overrode corporate interference in the land of indigenous peoples. A large amount of overlapping of permits given by the government to the private sector for the forests in possession of indigenous peoples has increasingly marginalized the indigenous community as a drawback of the development.

Second, the Dayak Kotabaru customary law regulates the forest management through the Bera system with the additional punishment in the form of fines. Moreover, forest management through local culture such as the Bera system in Dayak Kotabaru can be used for the benefits of the local community. Local people will enjoy the production of farms and gardens while the soil will be naturally fertile because of four years interlude and the forest will maintain sustainablility through less cutting down of forest area.

Third, several important things that need to be done in forest management are to designate a map of customary forest areas where the management and control of forests in communal tenure land are given entirely to indigenous peoples; then, the status and inauguration of customary forests must be clarified and published so that there is no overlapping of company permits in customary forests. In addition, the harmonization of the Ministry of Forest policies in designation forest areas must be harmonized with spatial planning in each region.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.; methodology, I.; validation, I; formal analysis, I., F.A.A., A.H.B, Y.N, and M.Y.S; investigation, I., F.A.A., A.H.B; resources, Y.N; data curation, M.Y.S; writing—original draft, I. and M.Y.S; preparation, Y.N; writing—review and editing, M.Y.S; visualization, Y.N.; supervision, I.; project administration, I., F.A.A., A.H.B.; funding acquisition, I.; translation, M.Y.S.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

This research used the descriptive–analytic method with the support of secondary data which obtained from World Resource Institute, Global Forest Watch, Center for Global Development and Monograph from Lambung Mangkurat University, Faculty of Law.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Article 33, Paragraph 3 of the 1945 Constitution of the Republic of Indonesia. Available online: http://www.unesco.org/education/edurights/media/docs/b1ba8608010ce0c48966911957392ea8cda405d8.pdf (accessed on 20 March 2019).

- Muchsan. Hukum Administrasi Negara dan Peradilan Administrasi di Indonesia; Liberty: Jakarta, Indonesia, 2006. (In Indonesian) [Google Scholar]

- Asshiddiqie, J. UUD 1945: Konstitusi Negara Kesejahteraan dan Realitas Masa Depan; Speech at Faculty of Law University of Indonesia: Jakarta, Indonesia, 13 June 1998. (In Indonesian) [Google Scholar]

- BAPPENAS. Indonesian Climate Change Sectoral Roadmap (ICCSR) Summary Report Forestry Sector; Republic of Indonesia Synthesis Report: Jakarta, Indonesia, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Antonio, W.; Griffith-Charles, C. Achieving land development benefits on customary/communal land. Land Use Policy 2019, 83, 124–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ifrani. Kebijakan Hukum Pidana Terhadap Penyalahgunaan Perizinan Dalam Pengelolaan Kawasan Hutan. Ph.D. Thesis, Universitas Padjadjaran, Bandung, Indonesia, 2017. (In Indonesian). [Google Scholar]

- Nugroho, H.Y.; van der Veen, A.; Skidmore, A.K.; Hussin, Y.A. Expansion of traditional land-use and deforestation: A case study of an adat forest in the Kandilo Subwatershed, East Kalimantan, Indonesia. J. For. Res. 2018, 29, 495–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veit, P.; Ding, H. Protecting Indigenous Land Rights Makes Good Economic Sense; World Resources Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 2016. Available online: https://www.wri.org/blog/2016/10/protecting-indigenous-land-rights-makes-good-economic-sense (accessed on 20 March 2019).

- Marzuki, P.M. Penelitian Hukum; Kencana: Jakarta, Indonesia, 2005. (In Indonesian) [Google Scholar]

- Freeman, M.D.A.; Lloyd, L. Introduction to Jurisprudence; Sweet & Maxwell LTD: London, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Fajar, M.; Ahmad, Y. Dualisme Penelitian Hukum, 1st ed.; RajaGrafindo Persada: Yogyakarta, Indonesia, 2010. (In Indonesian) [Google Scholar]

- Hart, H.L.A. The Concept of Law; Nusa Media: Bandung, Indonesia, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Waxman, M.P. Teaching Comparative Law in the 21st Century: Beyond the Civil/Common Law Dichotomy. J. Leg. Educ. 2001, 51, 305. [Google Scholar]

- Ellydar, C. Negara Hukum, Demokrasi dan Konstalasi Ketatanegaraan Indonesia; Kreasi Total Media: Yogyakarta, Indonesia, 2007. (In Indonesian) [Google Scholar]

- Ni’matul, H.; Nazriyah, R. Teori dan Pengujian Peraturan Perundang-undangan; Nusamedia: Bandung, Indonesia, 2011. (In Indonesian) [Google Scholar]

- Bethan, S. Penerapan Prinsip Hukum Pelestarian Fungsi Lingkungan Hidup dalam Aktivitas Industri Nasional; Alumni: Bandung, Indonesia, 2008. (In Indonesian) [Google Scholar]

- Article 15 of Law No.41/1999 on Forestry. Available online: http://www.flevin.com/id/lgso/translations/Laws/Law%20No.%2041%20of%201999%20on%20Forestry.pdf (accessed on 20 March 2019).

- Safitri, M.A. Menuju Kepastian dan Keadilan Tenurial (edisi revisi 7 November 2011); Kelompok Masyarakat Sipil untuk Reformasi Tenurial: Jakarta, Indonesia, 2011. (In Indonesian) [Google Scholar]

- Meidinger, E. The Administrative Law of Global Private-Public Regulation: The Case of Forestry. Eur. J. Int. Law 2006, 17, 47–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Hoadley, M.C. The Leiden Legacy: Concepts of Law in Indonesia (Review). J. Soc. Issues Southeast Asia 2006, 21, 124–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syamsudin, M. Beban Masyarakat Adat Menghadapi Hukum Negara. Law J. 2008, 15, 338–351. (In Indonesian) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiliam, D.; Ngakan, P.O.; Achmad, A.; Tako, A. Dinamika Proses Desentralisasi Sektor Kehutanan di Sulawesi Selatan: Sejarah, Realitas dan Tantangan Menuju Pemerintahan Otonomi Yang Mandiri; Cifor: Bogor, Indonesia, 2005. (In Indonesian) [Google Scholar]

- ULM Faculty of Law. Lambung Mangkurat University Faculty of Law in Cooperation with Tanah Bumbu District Government, Monograph Entitled “Hak-Hak Adat Atas Tanah Suku Dayak Kotabaru”; ULM Faculty of Law: Banjarmasin, Indonesia, 2007. (In Indonesian) [Google Scholar]

- Cramb, R.A.; Wills, I.R. The role of traditional institutions in rural development: Community-based land tenure and government land policy in Sarawak, Malaysia. World Dev. 1990, 8, 347–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, B.E.; Holland, M.B.; Naughton-Treves, L. Does secure land tenure save forests? A meta-analysis of the relationship between land tenure and tropical deforestation. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2014, 29, 281–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Said, M.Y. Sanksi Pidana Sebagai Premium Remedium Bagi Pelaku Tindak Pidana Di Bidang Kehutanan; Research Paper; Universitas Islam Kalimantan Muhammad Arsyad Al-Banjari Banjarmasin: Kota Banjarmasin, Indonesia, 2018. (In Indonesian) [Google Scholar]

- Sahalessy, J. Peran Latupati Sebagai Lembaga Hukum Adat Dalam Penylesaian Konflik Antar Negeri Di Kecamatan Leihitu Propinsi Maluku. Sasi J. 2011, 17, 45–52. (In Indonesian) [Google Scholar]

- Rosmidah, R. Pengakuan Hukum Terhadap Hak Ulayat Masyarakat Hukum Adat Dan Hambatan Implementasinya. Inov. J. Law 2010, 2, 92–102. (In Indonesian) [Google Scholar]

- Mudjiono, M. Eksistensi Hak Ulayat dalam Pembangunan Daerah. J. Huk. UII 2004, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferretti-Gallon, K.; Busch, J. What Drives Deforestation and What Stops It? A Meta-Analysis of Spatially Explicit Econometric Studies; CGD Working Paper 361; Center for Global Development: Washington, DC, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).