1. Introduction

The world witnesses a huge increase in infrastructural investments (e.g., highways, dams, power plants, pipelines, and railways). Simultaneously, the industry has to comply with a growing number of environmental rules and regulations, and is expected to proactively internalize environmental performance in a way that is similar to that of other industries [

1].

The construction industry is perceived as a major contributor to environmental degradation [

2]. As an example, the sector consumes 40% of the virgin materials that are extracted, while it produces 10–35% of the waste that is found in the disposal sites [

3,

4]. Literature reports very few studies that are related to reuse and recycling of construction waste in low- and middle-income countries, and even less studies on factors that are affecting the implementation of reduction practices. According to Ofori [

5], this result is due to a lower awareness for performing waste management in the low- and middle-income countries construction sector and less pressure on land resources used for construction waste disposal [

6].

Among the few authors from low- and middle-income countries on the reuse of construction materials, it is good to mention Acchar et al. [

7], who have investigated the reuse of masonry trimmings, concrete, and mortar in clay based building ceramics. Others have reported on recycling construction waste, but mostly in relation to concrete aggregates [

8,

9,

10]. Barriers and motivations for the implementation of construction waste reduction practices have been described by authors, mainly from China, Chile, and Thailand, as introduced in

Section 5. Their identification is essential since it enables major decision makers with the intention of exploring strategies to promote a better performance on the use of materials to understand them [

11].

The main objective of this paper is to report the findings of a study that was performed on barriers and motivations, in addition to those found in the revised literature, that influence the efficiency and effectiveness of construction-waste-reduction practices, including the reuse and recycling of construction materials.

2. Construction Industry in Low- and Middle-Income Countries

The construction industry contributes to a significant percentage of the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) in low- and middle-income countries, and provides employment to a substantial portion of the working population [

12]. According to Thomas [

13], the construction technologies do not meet the functional requirements as set for the construction industry in general in these countries. There is a lack of development of basic simple equipment, and often there are few qualified equipment operators. The organizational structure is rather diffuse; activities are often carried out on an ad-hoc basis. Material components are typically sized to facilitate manual handling because smaller construction equipment like forklifts and rough terrain cranes is almost non-existent. Fabrication facilities are limited. Masonry units and batching of concrete is done on site [

13].

Studies show that in a number of countries that a growing amount of private clients are choosing to bypass general contractors and the more formal procedures for awarding contracts, in favour of buying materials and managing the building process themselves, and engage directly with enterprises from the informal sector. Contracts between the parties are mainly verbal, and construction happens in a series of stages [

14].

The industry is consistently ranked as one of the most corrupt: large payments to gain or alter contracts and circumvent regulations are common. The impact of corruption goes beyond bribe payments to poor quality construction of infrastructure with low economic returns alongside low funding for maintenance and this is where the major impact of corruption is felt [

15]. An example is the disaster in Bangladesh’s garment industry in 2013, in which a building collapsed, whereby killing more than one thousand workers due to extremely poor quality iron rods and cement [

16].

Low- and middle-income countries are characterized by lack of resources, expertise, and insufficient communication structure. Ofori [

17] affirms that the construction industry lags behind other sectors in its response to the problems of the environment. In low- and middle-income countries, the environmental aspect receives even less attention, even though it is of critical importance and it many see that it should be undertaken as a matter of urgency.

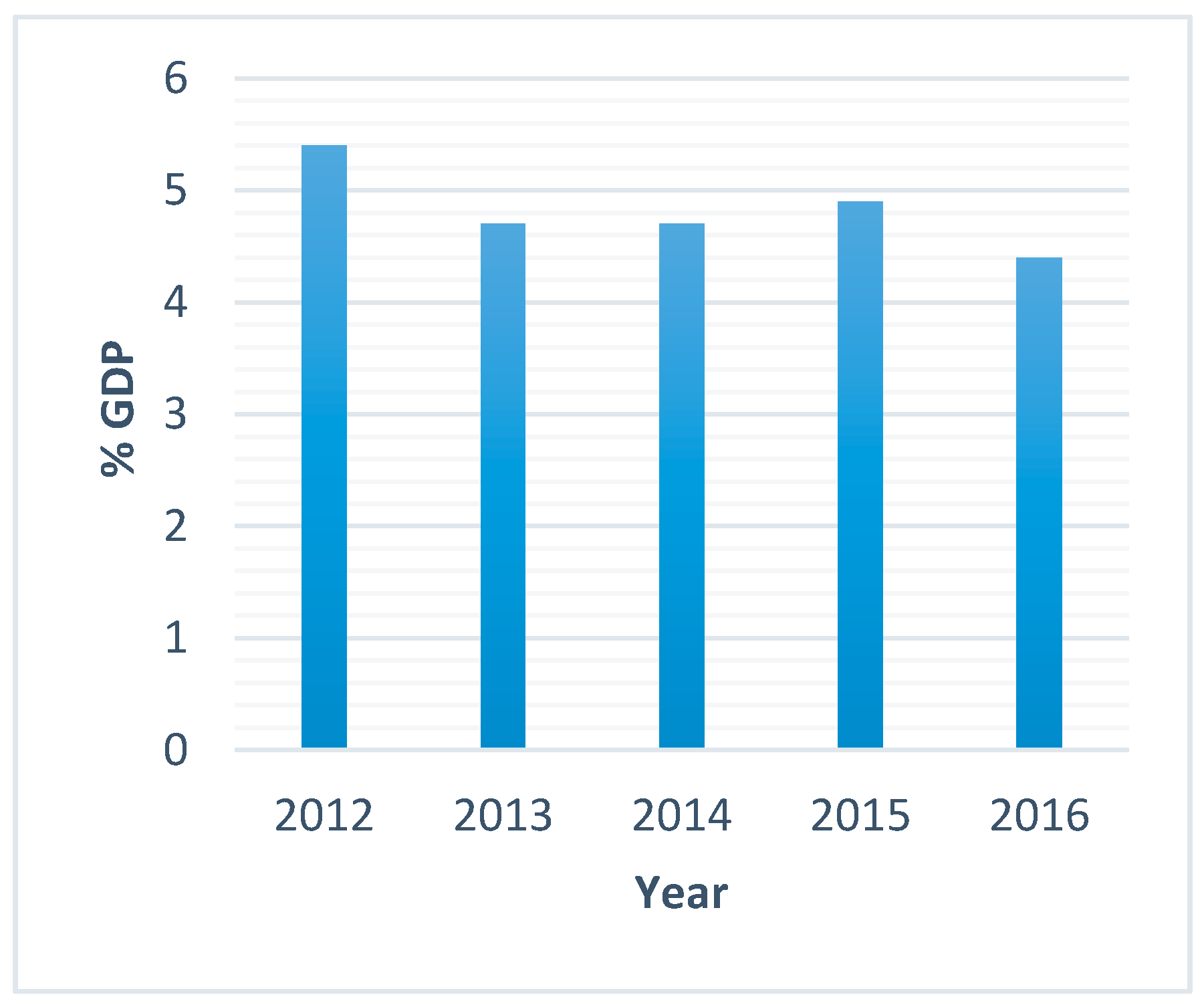

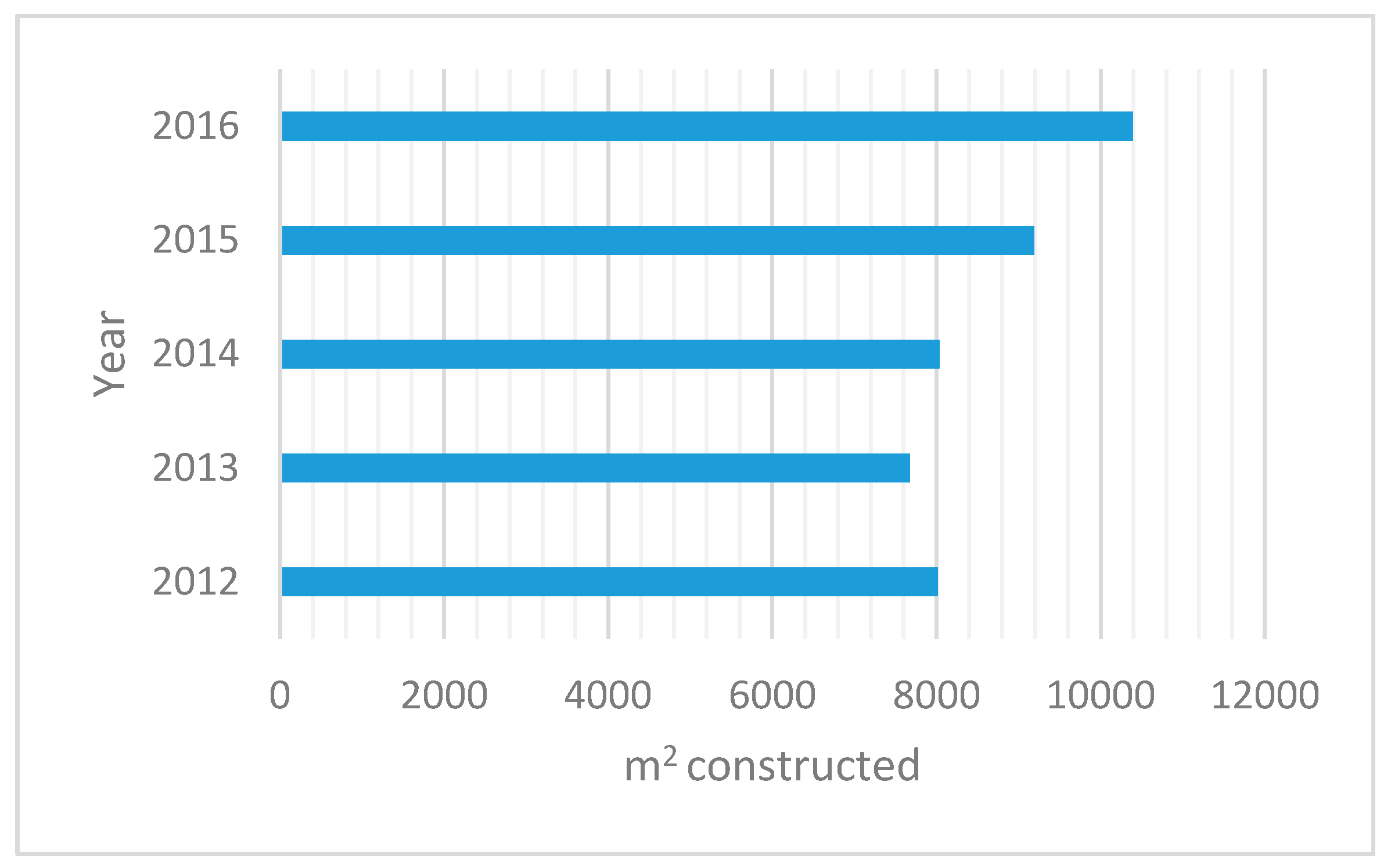

Costa Rica is a middle-income country in Central America, with approximately 4.9 million inhabitants, in which 60% lives in urbanised areas [

18]. The contribution of the construction sector to the Gross Domestic Product in the last five years is represented in

Figure 1, while the m

2 annually built is depicted in

Figure 2. Both show the importance of this sector in the economy of the country. The built area is in general distributed as: housing 40%, commercial 25%, urbanistic 16%, industrial 6% and other 13%. Some studies have reported construction waste generation in housing projects ranging from 700 kg/m

2 to 24 kg/m

2. Comparisons among the projects is not possible due to different construction processes, different materials, and the diversity of methods analysing the generation of waste. The most important (in quantity) residual products that are indicated by construction companies are: wood (clean and mixed with concrete), metals (piping systems and corrugated roof shields, reinforcing steel), packaging materials, pieces of block and concrete, paints, and others in minor quantities [

19].

3. Barriers and Motivations for Improved Construction Waste Reduction Practices

To determine the barriers and motivations for implementing good practices for construction waste faced by the construction industry in low- and middle-income countries, seven journals in construction and waste management for the period 2000–2017 have been reviewed: Resources, Conservation and Recycling, Waste Management Journal, Waste Management and Research, Construction Management and Economics, Construction Management and Engineering, and Building Research and Information.

The major barriers and motivations for construction waste reduction reported in literature are grouped around six different aspects: financial, institutional, environmental, socio-cultural, technical, and legal [

22].

3.1. Financial

Literature suggests that financial obstacles are related to the absence of markets receiving recycled construction products, which jeopardize efforts for construction waste recycling or minimization practices [

23]. They also mentioned that the sector is reluctant to conduct construction waste management because they perceived that it would result in higher project costs. Moreover, there is an absence of economic penalizing methods for inappropriate waste management, thus hampering construction waste reduction practices. Teo and Loosemore [

24] found that the workers consider the financial benefits from waste reduction to be inequitably distributed. There is also a perception that waste reduction activities are not cost-effective, efficient, practical, or compatible with core construction activities. They also determined the unwillingness of the workers to separate for recycling or re-using materials that have low economic value or are difficult to reuse.

3.2. Institutional

Various authors have suggested that the institutional barriers are related to the fact that designers do not pay attention to waste reduction while designing a building, inconsistencies between different governmental agencies and the lack of coordination among divisions for the application of environmental regulations, the unavailability of waste management procedures (collection, separation, transportation, and disposal of construction waste), lack of managerial commitment and support for the application of better construction practices, absence of norms or performance standards for managing construction waste, and lack of integration of operatives’ expertise and experience in waste management processes [

23,

25,

26]. In addition, internally, individual responsibilities for waste management is poorly defined, inadequately communicated, and are perceived as irrelevant to operatives [

24].

3.3. Environmental

Awareness and education have been mentioned as two major topics in relation to environmental barriers for improved construction practices, as well as a lack of sustainable building education at university level, inadequate training by construction workers on waste handling issues, absence of awareness on clients about sustainable housing, and the impact of the activity on the environment. The government and the private sector are more interested in the housing deficit than in environmental issues. Furthermore, healthcare and waste handling training are essential to prevent risks from being exposed to wastes on-site and off-site. When this is provided, stakeholders feel more motivated to voluntarily deal with wastes [

23,

25,

26].

There are sufficient technologies available for building with less production of construction waste but there are technical barriers hampering those practices such as insufficient knowledge on how to implement eco-technologies, deficient education for practitioners, and on site operatives on waste reduction practices, which results in a lack of these skills during the construction process [

13,

23,

25].

3.4. Socio-Cultural

Reported socio cultural barriers are the lack of awareness on the clients and construction workers, which has created a behaviour in which clients have a low demand for sustainable buildings, traditional construction culture, and behaviour, e.g., in China, conventional cast in-situ construction is still the preferable technique against prefabrication [

23,

25].

Furthermore, waste reduction efforts will never be sufficient to completely eliminate waste because it has been accepted as an inevitable by-product of the construction activity. Teo and Loosemore [

24] reported that gender equality has a direct causal effect on construction waste management efforts because women are generally more aware of these issues and can influence stimulating the effectiveness of policies and planning for management of construction waste and pollution. Furthermore, they found that the major practitioners are unlikely to perceive waste management with great importance on projects unless managers make it a priority and provide the necessary supporting facilities, incentives, and resources.

3.5. Legal

Construction waste reduction practices are motivated when a legal framework is in place that considers environmental regulations and recycling mandates [

4]. Many low- and middle-income economies have created regulations that address the generation of waste by the construction sector. Yuan et al. [

23] and Manowong [

26] have reported that legal barriers hampering waste reduction practices are related to insufficient policies in place, if policies exist they are difficult to put into practice, and very often in the absence of enforcement mechanisms.

3.6. Technical

Some scholars have identified financial, technical, and institutional motivations in relation to construction waste reduction. Chini [

27] has indicated that higher disposal cost at landfill site has increased the use of recycled materials. Moreover, he reported that recycled aggregates would have greater acceptance by the public when there are specific guidelines for their use.

Companies with a waste management culture within the organization invest in construction waste management by employing waste management workers, purchasing equipment and/or machines for waste minimization, and improving workers’ skills. Other technical motivations include: site space for performing waste management, low-waste construction technologies, service experience with recycled materials, development of specifications, and guidelines for the use of recycled materials [

4].

4. Materials and Methods

The data were collected in two phases. In the first phase, a survey instrument was prepared based on Kuijsters [

25] found in

Appendix A. It contained a total of nine queries that were proposed from literature that covered a number of topics: general information about the responding company, as well as the level of education completed by the supervisor that was directly involved with construction site activities. It included two questions about barriers and motivations for construction waste reduction, as measured on a five-point Likert-type scale, with anchors ranging from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (5), and one binary scale question (Yes/No). Respondents were asked to include additional barriers or motivations that they considered important to mention.

Prior to data collection, the survey instrument was pre-tested for ease of understanding and content validity in two stages. In the first stage, seven experienced construction engineers from the Research Centre for Housing and Construction of the Costa Rica Institute of Technology were asked to scrutinize the questionnaire for ambiguity, clarity, and appropriateness of the items that were used to operationalize each construct. Based on the feedback received from these researchers, the instrument was improved to enhance clarity and appropriateness. In the second stage, the survey instrument was sent via e-mail to 419 main contractors registered at the School Federation of Engineers and Architects (CFIA). Efforts were made via the telephone to ensure a high response from respondents.

The second phase had the goal to validate the findings of the data collection. A focus group with 49 professionals from the construction industry was organised, with the objective to get more insight in the survey results, to analyse their views on the presented topics, and to collect a wider insight into different opinions [

28]. The 49 professionals consisted of companies that participated in the survey, representatives of the Federation of Architects and Engineers, academic sector, Costa Rican Construction Chamber, and the Cleaner Production Centre. The found barriers and motivations were presented and discussed to validate them within the Costa Rican context.

5. Results and Discussion

A total of 30 companies responded, of which one was discarded due to incomplete information resulting in an effective response rate of 7% (29/419). They represented small-, medium-, and large-companies, according to the definition in Costa Rica: small with less than 25 employees but more than eleven; medium is with more than 25 but less than 100; and, big with more than 100 employees. The respondent companies do not represent the whole spectrum of existing construction companies in Costa Rica since the sector consists mainly of micro-, small-, and medium-sized enterprises (MSMEs). The ‘micro firms’, with ten or fewer employees, make up for 30% of the total number of companies [

19]. They did not participate in the survey because they work mainly in the informal market and are not registered in the used database of the School Federation of Engineers and Architects.

The construction sector in the country is labour intensive, the division between the workers is sharp: a small group of higher level of education workers, mainly composed by skilled engineers and managers that are organized on a permanent basis, and a bigger group with low-education and low motivated employees working on site, which are hired with temporary contracts and low salaries. Two-thirds of the supervisors have primary education or secondary education up to the third year (nine years of education). It was reported during the professional group meeting that the training of the workers takes place in an informal way on site. It is common to hire unskilled migrants from neighbouring countries, who often have an illegal status. It may be expected that most of the talented workmen without a degree are promoted from the building practice and they slowly move towards more managerial tasks. As mentioned by Osmani [

29], knowledge and education programmes could potentially help to appreciate waste minimization benefits.

Companies were requested to report on the use of a waste management plan or of the appointment of an employee/manager who has the responsibility to guarantee an efficient and responsible material handling practice. A waste management plan (WMP) puts the waste issue on the map, making it the first step to identify whether a potential waste problem exists [

30]. The results indicated that few companies (13%) had a waste management plan or an employee/manager who is responsible for a guaranteed efficient and responsible waste handling at the beginning of the projects, 13% of the companies reported that they have both (plan and manager), but 74% of the responding firms do not have a plan nor manager. This reflects the fact that working in an environmental friendly way is not yet institutionalized within the construction companies in Costa Rica.

The queries proposed from literature were used to analyse the barriers (

Table 1) and motivations (

Table 2) that are faced by the Costa Rican construction sector to apply practices for waste reduction. For simplicity reasons, only one author is mentioned. New barriers found in present study, which were not mentioned during the literature review, are included with an acronym PS which means Present Study.

The financial barriers that were found during this study are related to prices of the construction projects, which do not reflect the costs of the environmental impact: reduction of natural resources that are disposed of and pollution caused to water sources, soil or air by disposal of hazardous materials. The companies are not interested in improving their processes environmentally due to their first priority, which is financial profit. The emphasis is on investment costs in the short term over savings in the long term.

Contractors indicated that they do not develop waste management plans for various reasons. Firstly, it is not obligatory under the present country’s legislation, it is not requested by the client and they have no knowledge on how to set one up. It is important to point that the Bill of Quantities that is prepared by the project director already includes an extra 10% in the budget, which is earmarked as “debris”. This practice, which is common among all of the construction companies, already reduces the need to save materials. Additionally, they have the belief that waste reduction efforts will never be sufficient to eliminate waste.

Legal barriers that are provided during the study indicate that though Costa Rica has laws related to waste management, the country lacks regulations to operationalise the laws and the government is not capable to enforce the laws while the companies do not have sufficient information on the environmental norms and the requirements expected to follow these norms.

A recent study on reuse and recycling construction waste in Costa Rica [

31] showed the presence of private initiatives collecting materials for reuse or recycling of metals, glass, ligneous materials from packaging of products, plastics, debris for land levelling activities, and gypsum. These enterprises also mentioned that they faced those barriers in preventing the development of a more effective and efficient construction material recycling market.

Table 2 shows the different motivations to prevent construction waste. Some of them are related to removing the barriers for better construction material management and few mentioned the lack of awareness on the reduction costs by reducing materials losses, savings in raw materials, energy and the profits by reselling of sub-products. They also mentioned that if the law would be enforced and fines or compensations are to be paid, then the company would make efforts to reduce the pollution.

Construction companies are following what the competitors are doing in relation to sustainable construction. They started to recognise the opportunity to promote their image and to improve their market share by including, among others, good practices for material management. The construction sector is committed to creating environmental awareness to the stakeholders. Material suppliers can play a very important role in providing adequate assistance and information on new equipment and materials. Clients requesting sustainable buildings would promote the change of attitudes and behaviour of major practitioners.

As mentioned by Esin and Cosgun [

32], the most effective method of reducing the environmental impact of construction waste is primarily by preventing its generation and reducing it as much as possible. Efforts should be made to provide incentives for the reuse of construction materials and the creation of recycling companies processing all materials produced as waste.

6. Conclusions

This paper presented the findings from a research conducted in Costa Rica, which looked at barriers and motivations for the construction sector to be more efficient and effective in the reduction of construction materials. This study adds extra barriers to those already reported in existing literature: “construction price does not reflect the environmental cost”, “first priority is financial profit and not environmental issues”, “emphasis on investment cost, not on low cost on long term”, “lack of time to develop plans for waste reduction”, “a belief that waste reduction efforts will never be sufficient to completely eliminate waste”, “deficiency of environmental regulations”, and “lack of available information regarding the requirements of environmental norms”. Motivations were analysed and additional barriers and motivations were found: “awareness of reduction of costs due to: reduction material loss and savings of raw materials”, “diminishing of legal costs associated with environmental problems and insurance (fines, compensation)”, “additional profits, as a result of the reselling of sub-products”, “savings on energy (electricity, fossil fuels)”, “promoting the image of the company”, “improve market share/competition”, “following what the competence has done”, “environmental awareness of the industry”, “improving workers’ skills”, assistance or information from suppliers”, “demand by clients of sustainable buildings”, and “government environmental enforcement”.

This study shows that the barriers and motivations that were found are in accordance to reported ones from China [

23], Chile [

25], and Thailand [

26], as well as from high-income countries, such as United Kingdom [

24,

30]. These results indicate, as mentioned by Koskela [

33], that the achievement of a low carbon and low resource economy requires significant and radical changes in the socio-technological systems, especially if countries are striving to be low-carbon societies, such as Costa Rica.

This study contributes to a growing research stream documenting the construction sector challenges in emerging countries, using Costa Rica as a case study. The identification of new and other reported major barriers and motivations to implementing construction waste reduction practices, allows for determining which aspects must be approached in order to improve the performance of the sector, which can be extended to studies in other countries in the world.

Table 1 and

Table 2 show that the barriers and motivations are around financial, institutional, environmental, technical, socio-cultural, and legal aspects. Similar findings were obtained by Guerrero et al. [

22] analysing factors that influence waste management systems in some world cities.