Abstract

Recognition of multiple knowledge systems is essential to facilitate collaboration and mutual learning between different actors, integration across social and ecological systems, and sustainable development goals. This study aims to identify how local knowledge from the indigenous people in developing countries contributes toward supporting the social–ecological system. We use a case study of the Ammatoa community, one of the indigenous communities in South Sulawesi Province, Indonesia. This study shows how their social and ecological practices are combined to develop their customary area and how the Ammatoa’s customary values contribute towards achieving Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) 15 and 12 of the United Nations, i.e., leveraging local resources for livelihood and ensuring sustainable consumption and production patterns. Examples of practices elaborated in this paper are protecting, restoring, and promoting sustainable use of terrestrial ecosystems, sustainably managing forests, combating desertification, halting and reversing land degradation, halting biodiversity loss, and ensuring sustainable consumption and production patterns. Furthermore, the Ammatoa’s customary values form a sustainable system that not only affects their social aspects, but also their economy and surrounding environment. This research can be used to develop relevant environmental-related interventions related to SDGs 15 and 12 from indigenous peoples’ perspectives.

1. Introduction

Complex environmental problems have encouraged the growth of a multidisciplinary approach to adequately identify environmental problems. Since the last decade, researchers have developed new approaches and modeling frameworks, such as the ‘socio-ecological coupling’ or ‘human and natural systems’ [1] to better understand the different dimensions of system functioning. These advancements also focus on the creation and realization of normative social goals, such as those related to sustainability [2]. These approaches support a more pluralistic and integrative understanding to the complex sustainability challenges that humanity is currently experiencing. The socio-ecological system (SES) idea has evolved into a mainstream field of research focused on the interdependent links between social and environmental change, and how these interdependent links influence the accomplishment of sustainability goals across many systems, levels, and scales [3].

Knowledge acquisition of SESs is an ongoing, dynamic learning process, and such knowledge often emerges in people’s institutions and organizations. Thus, the communities that interact with ecosystems on the daily basis and over long periods of time possess the most relevant knowledge of resource and ecosystem dynamics, together with associated management practices [4]. Recognition of multiple knowledge systems is essential for facilitating collaboration and mutual learning between different actors, integration across social and ecological systems, and the achievement of sustainable development goals [5].

Indigenous local knowledge (ILK) is different from science because ILK does not divide knowledge into disciplines. For example, some aspects of indigenous people’s knowledge of weather and climate may be related to different disciplines, such as botany, zoology, or pedology, and not relevant to climate science. It implies that indigenous people’s knowledge of weather and climate is intimately linked to their understanding of plants, animals, soils, and food [6,7]. Indigenous perspectives are holistic and based upon interconnectedness, reciprocity, and the utmost respect for nature. Both non-indigenous and indigenous science approaches and perspectives have their own strengths, and can greatly complement one another [8].

In the socio-ecological context, weaving generalized and context-specific perspectives is not limited to assessments by indigenous peoples and local communities [9]. Socio-ecological systems research related to ILK is focused on understanding the many dimensions of system functions and implementing normative social goals, such as those related to sustainability in the lives of indigenous people [10]. Some research studies proved that indigenous communities play a key role in environmental management and biodiversity management [11,12,13]. Those studies show how indigenous people sustained cultural values and environmental ethics, especially in saving the environment [14]. Indigenous people have established long-standing relationships with their surrounding environments [10]. Indigenous communities have good systems for integrating useful data in the philosophies of thought and modes of activity associated with a particular landscape [1,5,15].

Human relationships with flora and fauna, land and water, and supernatural forces have been mapped out in a variety of evidence (e.g., geographic, genealogical, biological, and other evidence) handed down through regular indigenous performances, including oral traditions, songs, dances, and ceremonies, convey literal and metaphorical truths about those relationships [16,17]. In some countries, ILK has been used as a basis for policy determination. For example, in forest conservation efforts, community-based forest companies have been relatively successful in the municipality of Ixtlán de Juárez in the Mexican state of Oaxaca, because the legal system recognizes and protects the rights of indigenous peoples, and local communities are given autonomy to decide the use of forest, forest resources and the sharing of benefits arising from them. In Sri Lanka, there has been a change in policy to revive traditional agricultural practices as a means to promote food self-sufficiency and entrepreneurship [18].

Despite its potential, ILK faces some challenges. One of them is a value degradation over time which is due to unwritten ILK, i.e., ILK is most often transmitted orally from one generation to another. As a result, the inherited knowledge base which is held by the future generation cannot explain these environmental changes [19,20,21]. In a study on ILK maintenance conducted in Vanuatu, it was found that the drivers of social change (such as linguistic shifts) will continue to influence, and in some cases reduce ILK [22]. Furthermore, implementing ILK in a broader context or outside of the community is another challenge [19].

Indonesia is the home of an estimated 70 million indigenous people. They are divided into 2371 indigenous communities spread across 31 provinces in Indonesia. The largest Indigenous communities distributed are on Kalimantan island, with 772 indigenous communities, and on Sulawesi island, where there are 664 indigenous communities [23,24]. Indigenous communities inhabiting different geographical areas will result in different characteristics of the customary values, including the context of environmental issues. To the best of our knowledge, no article comprehensively discusses how ILKs, i.e., these traditional values and local knowledge, shape the social–ecological system and the extent to which the indigenous community’s concept of life can be applied outside the customary area, in the Indonesian context. To be specific, there are two main research questions aimed to be answered in this study: (1) “what ILKs shape the social–ecological system in an indigenous community?”, and (2) “what are the lessons learned from the ILK system with regards to a bigger context?”.

In this research, we use the Ammatoa community as a case study, which is an indigenous group that still exists in Indonesia, well-known for its knowledge system on environmental conservation which comes from Pasang ri Kajang (“Message from Kajang” in English). Pasang is a collection of messages, tips, hints, instructions, and rules for how a person places him/herself in the macro and microcosmos and procedures for establishing harmony between nature–human–God [25]. They apply customary values, not only in a social context but also in an economic and environmental context. Wohling implies [19] that not all ILK can be applied to the broader context or outside of the indigenous community. However, we argue that there are still some lessons learned from the ILK that can be applied widely, which can then be part of answering the second research question. Finally, it is expected that by studying the life of the Ammatoa community, the gap between the ILK systems and the scientific knowledge system can be bridged.

2. Materials and Methods

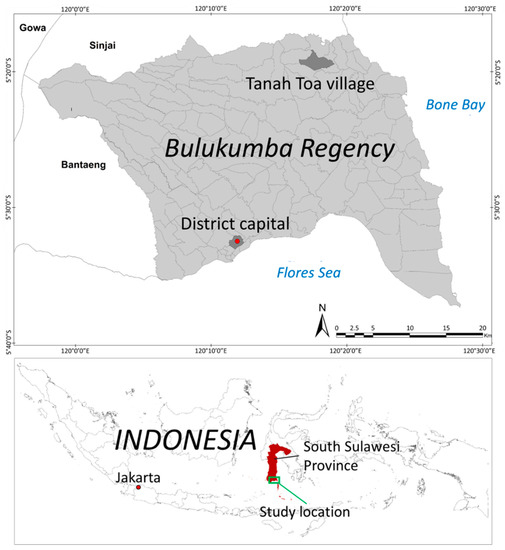

An exploratory study was conducted to answer the first research question mentioned previously, i.e., to explore how ILKs shape the social–ecological system [26]. We then analysed the findings and linked them to the SDGs, i.e., what we can learn from the ILK. The Ammatoa customary area is administratively located in Tanah Toa Village, Kajang District, Bulukumba Regency, South Sulawesi Province, Indonesia (Figure 1). The total area of the Ammatoa region is 72,247 hectares. The Ammatoa community is known for its forest conservation and simple life. Their customary territory consists of settlements, agriculture, and forest. They always wear black clothes, which symbolize their unity and simplicity. They have defended their customary area through the customary system they have built, covering social, economic, and environmental aspects, which originate from their customary values, called pasang ri Kajang (“message from Kajang” in English). The Ammatoa community was selected because the research team came from an area close to the Ammatoa traditional area, making it more accessible for conducting this study.

Figure 1.

The study location in the Tanah Toa Village, Bulukumba Regency, South Sulawesi Province, Indonesia.

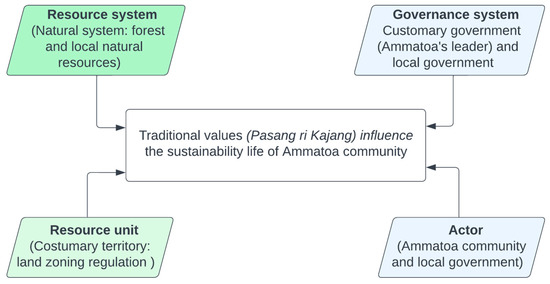

This study was approved by the local government and the leader of the Ammatoa community. The researcher stayed in the location for several days and conducted semi-structured, in-depth interviews with the leader of the Ammatoa community and local people to gain knowledge about their traditional values, especially those governing the social issues related to the environment. To be more specific, there were two community leaders, two people from the Ammatoa community, and three people around the study site who were interviewed, i.e., 6 men and 1 woman. We also combine data from the literature and field observations from April to May 2017. We have adopted a social–ecological system framework [27] to analyze the data (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

The social–ecological system framework in the Ammatoa community.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. The Social–Ecological System Framework in the Ammatoa Community

Understanding best practice and enabling factors that will contribute to increasing the resilience of socio-ecological systems is of paramount importance [18]. Interactions and outputs that arise in the social–ecological system are supported by several factors, including resource systems, resource units, governance systems, and actors [27]. Figure 2 illustrates the social–ecological system framework in the Ammatoa community. They built their own system which regulates the social, economic, and institutional aspects of their lives based on traditional values.

The actors in the SES Framework in this study are the Ammatoa community and local government. The synergy between the two parties is an effort to maintain the customary area by understanding the provisions inside and outside the customary area. In the Ammatoa community, the resource system is associated with a natural system where this community manages local resources in daily life in a traditional way. In addition, the sacred forest that has built a culture of conservation is also carried out because it is considered the center of the Ammatoa community. Another component that is an essential part of the SES framework is the resource unit. The customary government of the Ammatoa community also regulates land zoning regulations, such as establishing residential areas, rice fields, forests, and plantations. Meanwhile, the government system is related to traditional values that have been regulated by customary leaders and affect the way of life of the Ammatoa community.

3.2. The Effect of Customary Values on the Way of Life of the Ammatoa Community

The Ammatoa leader has the main task of maintaining the teachings of traditional values with the life principle of tallasa tamase-mase (“Live simply” in English) [28]. With this principle of life, they build their community by developing a sense of gratitude for what they have and living in moderation. In addition, indigenous values have shaped local knowledge and influenced the daily behavior of the Ammatoa community. These values are developed as a reference for building relationships with God, humans, and the environment [29].

An example of how the customary values influence the daily life of the Ammatoa community can be seen in the way they wear their clothes. The Ammatoa community is synonymous with black clothes, used both in traditional areas and areas outside their customary land. They use these colors for headbands for men, clothes, and sarongs; besides, they also travel barefoot. Women’s clothes also consist of sarongs and baju bodo (“Short sleeve shirt” in English) that are black. According to Ammatoa community belief, black color means equality, unity in all things, and simplicity. Black also shows the same power and degree in God’s sight [30]. The practice of dressing and not using slippers also applies to visitors who enter the customary area.

Another example of how customary values influence their daily life is related to the health aspect. According to the Ammatoa community, diseases can develop due to health determinants (such as personal and environmental variables), mystical elements, and breaking customary rules [31]. This indicates that indigenous people tend to choose traditional medicine that has been trusted for centuries rather than medical facilities. They face a myriad of obstacles when accessing the public health system. Access to the healthcare system is hampered by the cultural differences that exist between indigenous and healthcare workers, such as language differences, illiteracy, and lack of understanding of indigenous cultures and traditional healthcare systems [32]. On the other hand, the Ammatoa community’s challenges in the health sector are due to the absence of written knowledge about traditional medicines and treatments. In this case, the family education system had some limitations since the knowledge of medicinal plant use was only given when a family member was sick. There were no educational demands for the children to understand the treatment system. The family was unable to develop the youth’s interest and motivation to preserve the local knowledge [20].

3.3. Sustainable Pathway of the Ammatoa Community

3.3.1. Leveraging Local Resources for Livelihood

The Ammatoa community does not excessively exploit or waste all the natural potential to meet their needs in utilizing the earth’s products. The Ammatoa community optimizes local natural resources to meet their daily needs, including clothing, shelter, and food materials. In addition, they also process local ingredients into marketable products.

The black sarongs worn by the men are handmade and woven by the women in the Ammatoa community [30]. Black sarong coloring is done naturally, generally using natural materials in the forest, namely tarum (“Indigofera” in English). The Ammatoa woven fabrics have the benefit of not fading after the first wash and use only pure water for washing without detergent. The cloth motifs depict life lessons alongside nature and manifest simplicity for the Ammatoa community. They still maintain the ancient motifs of their ancestral heritage, i.e., ratu puteh for white line motif, ratu gahu for the blue line motif, and ratu ejah for the red line motif. Weaving the black sarong takes approximately a few months, starting from taking Indigofera leaves from the indigo tree until the white threads are soaked in a basin containing natural dyes for several days and then dried in the sun for several hours. After that, the threads are then spun and inserted into the loom.

A study showed that the Ammatoa community has good knowledge, attitudes, and practices (KAP) on the usage of medicinal plants to treat respiratory disorders [33]. They cultivate some plants for medicine, e.g., tammu (“Curcuma” in English) and jammu bo’dong (“guava” in English) to treat diarrhea, saffron for wound treatment, biccoro (“Melastoma candidum D.Don” in Latin) to get rid of bad breath, tangeng-tangeng (“Ricinus communis” in Latin) leaves for the treatment of fever, banana leaves for the treatment of women who have given birth [34]. A total of 104 plant species from 50 families were used for medicine in the Ammatoa community. The Asteraceae family accounts for the majority of these therapeutic plants (67.3%), followed by the Anacardiaceae, Arecaceae, Euphorbiaceae, and Fabaceae families (each accounting for 5.77%) [20].

The main livelihoods in the Ammatoa community are farming, fishing, weaving, and trading in the market. The Ammatoa community uses several types of wood and bamboo as infrastructure materials and palm sugar to sell [34]. In addition, the community farms obtain food by growing several types of crops (e.g., tomatoes, pepper, rice, and corn) and vegetables (e.g., green beans, soybeans) [14].

3.3.2. The Ammatoa Community’s Perception of Shaping Sustainable Settlement

The Ammatoa settlement is also equipped with traditional and simple housing facilities and infrastructure. A home for the Ammatoa community is a fundamental right because it is where their life begins. They believe that it is a sin if someone enters the home without cleaning their body. The house is important because it serves as the main place of interaction from birth to death. One to three families inhabit houses in traditional areas, usually consisting of parents and descendants who have married. The use of materials for buildings and infrastructure in customary areas must not affect the quality of the environment. One of the real actions of the Ammatoa community’s wisdom toward the environment can be seen in the selection of materials to build houses. Each house construction uses raw materials such as stone, wood, bamboo, and rattan, which are taken from the surrounding environment. In addition, the roof of the house does not use shiny material like copper because it is not in accordance with the kamase-masea (“modest” in English) concept. Therefore, the roof is made of thatched leaves commonly found in their customary areas.

The orientation of the houses in the Ammatoa community refers to traditional values. Settlements in customary areas must pay attention to the direction of placement and should not face sacred places, sacred forests, and deep valleys. To build a house, it is necessary to determine the right site or approval from uragi (“Feng shui master” in English), to determine the orientation of the building between human and natural harmony [35]. There are no traditional rules for the orientation of the house that require it to face west in order to increase the power of the Feng Shui master’s direction.

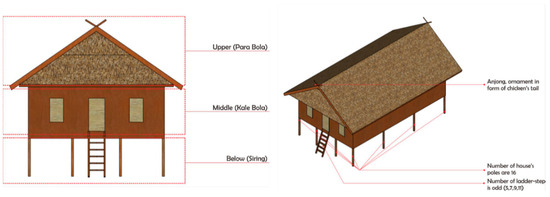

Figure 3 shows the design of houses in the Ammatoa settlement. The houses in the Ammatoa settlement are stilt houses that form three parts, and each has a function as siring (“the bottom part of the house that touches the ground” in English), kangkung balla (“a core part of the house” in Bahasa), and para (“the space on the ceiling of the house” in English). Part A of the house is used as a warehouse, weaving for women, carpentry for men, and for pounding rice. Part B is kangkung balla, considered as the main part of the house. It is a living space and a place to carry out daily activities. Meanwhile, Part C is a room on the house’s roof that has the function to store crops. House poles consist of 16 poles which are arranged 4 to back and 4 to the side, showing 4 elements that build the world and universe, i.e., earth, fire, water, and air [36].

Figure 3.

Design of Ammatoa community’s houses.

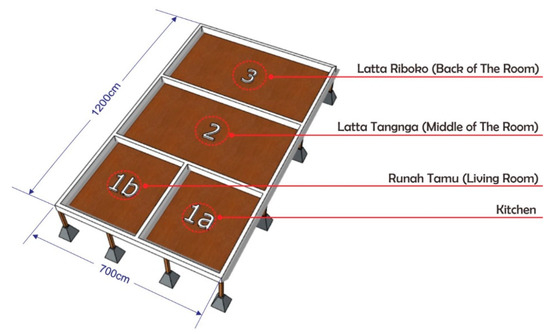

Figure 4 shows the floor plan of houses in the Ammatoa settlement. The floor plan in the Ammatoa community has three parts [30]. Part 1a, namely latta riolo (“front of the room” in English), is used as the kitchen, located on the right side of the entrance to the house, and part 1b is used as a reception area. The kitchen in the front room has a meaning that includes whatever is cooked by the house residents and must be served to the guests. Part 2 is latta tangnga (“living room” in English) used as a dining area, family room, and a place to receive guests. Part 3 is latta riboko (“the backroom” in English), used as a place for rest and located at the height of 30 cm from the front room and living room.

Figure 4.

Floor plan of Ammatoa community’s houses.

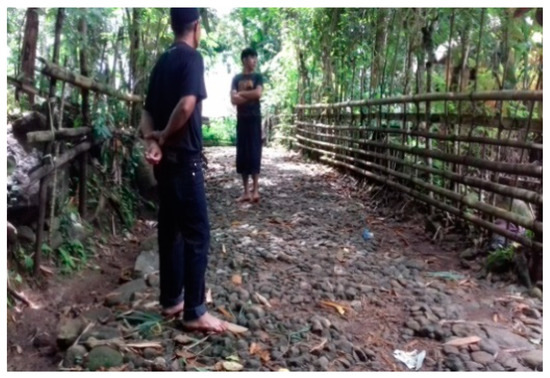

The traditional value also regulates settlement infrastructure. According to pasang, the Ammatoa community does not accept any modernization such as asphalting or casting [35]. Figure 5 shows that roads in customary areas are only cobblestone roads. Customary rules refer to environmental conservation efforts, where the construction of roads consists of only soil and rocks without hardening. Recent studies have shown that asphalt is a significant source of air pollution in urban areas, especially on hot and sunny days [37]. Consequently, the choice not to use asphalt in the Ammatoa customary area is an effective way to prevent air pollution. In addition, the absence of vehicles entering also frees the area from noise disturbance. Furthermore, in this area, there should be no development activities that interfere with the absorption of water into the ground, such as the use of asphalt. It is stated that in the local language rie sallo se’re hattu nalallo ulara le’leng a’teko ri lino, punna nalallomi kinni tana sikidi kidia kiama’mi lino (“In the future, black snakes will circle the world. If snakes have pass-through this customary territory, the apocalypse will soon come” in English). According to their belief, the meaning of “black snake” is asphalt, while “apocalypse” refers to disaster. Therefore, to avoid disaster, indigenous people defend their territory and do not accept all forms of modernization that can damage the environment in customary areas, e.g., the use of asphalt or concrete that can interfere with water absorption.

Figure 5.

The Amma Toa settlement’s road conditions.

The construction is also made of soil that carries water from the river to the rice fields. The condition of the customary area is maintained, without any soil sealing, so that the groundwater catchment area remains in a good condition. The drainage channel concept used in soil and water conservation system avoids the concentration of surface runoff in any place that is detrimental and destroys the land in its path. This system follows the physical conditions of the Ammatoa area. There are three types of canals: dodger channels, terraces, and grass channels. Dodger canals are made at the top of the slopes of agricultural land, which serve to capture water from the slopes and drain it into grassy channels. Terraces serve to collect water from higher terrace to lower ones and drain it into grassy channels. The grass channel is a natural channel at the bottom that can convey water from the other two channels to the river system.

Water and sanitation are also a concern for indigenous peoples. The Ammatoa community’s water sources come from wells and springs connected via salu (“pipes made of bamboo” in English) built from the edge of the forest to the settlement. Figure 6 shows the condition of traditional toilets in the Ammatoa community. In the customary area, indigenous people use traditional sanitation. The latrine’s construction is made by digging the ground to collect dirt. Then to cover the hole, a small hut was built using woven bamboo as a wall, and above it, there is a cover building that can be shifted when the hole is full. The drain hole is closed and equipped with a drainpipe to avoid unpleasant odors. This system is suitable for Ammatoa residential land conditions because it easily absorbs water. For this system, they do not use cement. It is low cost and simple but requires maintenance to prevent the spread of disease or odors, and the floors need to be cleaned regularly. However, recent research has shown that about 90% of houses already have a latrine, 7% of the houses share a latrine, and another 3% defecate in the bush [38].

Figure 6.

The latrine models of Ammatoa’s settlement.

3.4. Conservation and Protected Areas Management

The conservation embraced by ILK is more developed compared to current environmental resilience efforts. The concept of life, that seeks to balance human–environment interaction through simplicity and sustainability, is a practical example of environmental resilience. Tanah Toa village, where the Ammatoa community lives, is divided into two, i.e., the Ilalang Embaya (“customary area” in English) and Ipantarang Embaya (“the outside of the traditional area” in English). The Tuli, Sangkal, Limba, and Doro rivers become the boundary between the outside and the inside customary areas.

The division of the territory defines which areas can accept modernization and which cannot. In the customary area, they build resistance to external influences and modernization, because the rules prevent modernization and luxury from entering their territory. This is different from outside the customary area which has undergone modernization. Education, health, and government facilities are outside the customary area. Modern infrastructure only exists outside of customary areas such as asphalt roads, water supply systems, and telecommunication lines.

The Ammatoa community implements land zoning by dividing the region into rabbang seppang (“narrow boundary” in English) and rabbang luara (“wide boundary” in English). The narrow boundary is allocated for the customary forest. The traditional forest has contents that cannot be touched, to preserve it as required in the customary rule and for preserving the hydrological system. Thus, the wide boundary is categorized as a protected area covering the regions used for different purposes, such as residential, farm, and pasture. This region includes the entire area outside of the narrow boundary. When viewed from the point of the managing system of natural resources, land zoning, in fact, signals the ecological wisdom which is still relevant to the ideal land zoning system present in the modern era [29].

The forest in the Ammatoa region is the motherland of the area which is highly protected. The forest with 331 ha covers 63.77% of the total customary area. Forest management is regulated by customary rules, because the Ammatoa community believes that the forest is where their ancestors descended to protect the earth as an expression of gratitude and an effort to conserve resources [39]. They divided the forest management zone into three parts: the first zone is called borong karamaka (“sacred forest” in English); the second zone called borong batasayya (“forest boundary” in English); and the third zone is called borong luarayya (“Outer Forest” in English) [40].

Modernizations considered damaging or disturbing to the Ammatoa customary area are not allowed. For example, wood cutting machines are not allowed in customary areas because they make noise and cut down many trees. They believe that cutting down wood will reduce rainfall and affect the availability of springs. Therefore, they traditionally cut down trees (using machetes) because the process is long and requires more energy than using wood-cutting machines. This can be a consideration to take the wood as needed, preventing over-exploitation.

Forest management in the Ammatoa customary area is the business of the government and indigenous peoples. The existence of Ammatoa law against national law relating to forest management has been recognized, respected by the state, and is still valid in the Ammatoa community because it is considered relevant to the prevailing laws and regulations [34]. Either government or the Ammatoa community builds policies, and also develops forest implementation regulations that include forest and land rehabilitation and forest management. It can be a good illustration of collaboration for forest governance between indigenous people and the government. However, one of the policies issued by the government related to forest management is the use of modern equipment. The introduction of a modern forest management system is suspected to affect the local wisdom embraced by the Ammatoa community [40].

Running the system in the Ammatoa community also requires a controlling tool in giving sanctions for violators of customary rules. The enforcement of the rule is carried out to control people’s lives. Sanctions and litigation have been set for each type of violation to minimize deviant behavior. There are three levels of punishment that have been set in the Ammatoa Tribe, ranging from the lightest punishment to the most severe punishment. First, cappa ba’bala (“the tip punishment” in English) is the obligation to pay a fine of SAR 12 (Arabic currency) plus one buffalo. Second, tangnga ba’bala (“the middle punishment” in English) is a fine of 33 Real plus one buffalo. The highest fine is poko ba’bala (“the main punishment” in English), which must pay 44 Real plus a buffalo.

In this case, the real currency is only used as a value because the money used is hump and rarely found. There are two other forms of punishment used by the Ammatoa community. First, tunu panroli (“Burning a crowbar” in English) is a way for indigenous peoples to gather and carry burned crowbars. An innocent person will not feel the heat from a burning crowbar, while a guilty person will feel the heat from a burning crowbar. Second, tunu passau (“burning incense” in English) is used if the suspect escapes punishment by leaving the Ammatoa custom territory. The Ammatoa’s leader would burn incense and recite a mantra sent to the suspect, and she or he would suffer illness or die unnaturally.

3.5. Lessons Learned from the Local Knowledge of the Ammatoa Community

Indigenous and local knowledge systems differed from scientific knowledge systems, with different intellectual heritage, contexts, applications, and underpinned by substantially different institutions [6]. The strength of local knowledge lies in its easy-to-understand and easy-to-use aspects, because it grows and develops in the community. The Ammatoa community has built their life based on the rules in pasang, which developed into indigenous local knowledge (ILK). Unfortunately, these rules, messages, and values are not written down, so they are only conveyed through word of mouth from traditional leaders. Moreover, not all Ammatoa ILK can be applied in the broader and modern context, as implied by [19]. This research has summarized several pasang related to sustainability principles as indicated in Table 1.

Table 1.

Indigenous local knowledge for sustainable life.

Table 1 indicates some local knowledge in the Ammatoa community that can be applied in the broader and modern communities, i.e., forest conservation, building orientation, facilities and basic settlement infrastructures, land management, and sustainability concepts. Those values in the ILK can be used as lessons learned for environmental management outside of customary areas. The main lesson that can be learned from the Ammatoa community is how their local knowledge forms a sustainable system that not only affects their social aspects, but also their economy and environment. ILK from the Ammatoa community is closely related to the SGD 15, i.e., to protect, restore and promote sustainable use of terrestrial ecosystems, sustainably manage forests, combat desertification, halt and reverse land degradation and halt biodiversity loss. In addition, the modest principle of the Ammatoa community is related to SDG 12, i.e., to ensure sustainable consumption and production patterns.

Many studies on forest conservation carried out by the Ammatoa community have been published in English (e.g., [13,28,29,41,42,43]) and Indonesian (e.g., [44,45,46]). These articles show that in the indigenous people’s knowledge of the Ammatoa community, there are at least two main functions of the forest, i.e., a ritualistic function and an ecological function. The ritualistic function views the forest as something sacred. Various ceremonies are performed in the forest as a consequence of this belief, for example, the inauguration of the traditional leader, attunu passau (“curse ceremony for trespassers” in English), angnganro ceremony (“ceremony to ask God for help” in English). Meanwhile, the ecological function views the forest as a regulator of the water system, as it causes rain and springs to fall. Forests in the Ammatoa customary area serve more as protection than other practical functions [47].

Indonesia is prioritizing the SDG Target 15.2 for the restoration of degraded land [48]. Indigenous people who have been living in forests in Indonesia have a crucial role. They have developed interdependent systems of agriculture and forestry that are uniquely suited to the ecological requirements of the land they inhabit [49]. Local knowledge owned by the Ammatoa community has the potential to contribute to the development of forestry (i.e., forest as the center of the area, prohibition to cut down forests indiscriminately, and prohibition of forest function conversion) from local, regional, and national levels. Both local knowledges of the Ammatoa community and modern knowledge share the same view on forest conservation. Compared to customary outside areas, the government has regulated forest conservation. For example, the Ministerial Regulation of Environment and Forestry of the Republic of Indonesia (Number 9/2021) explains that forest areas act as a buffer system for life by regulating water systems, preventing flooding, preventing erosion, seawater intrusion, and maintaining soil fertility.

Another lesson learned from the Ammatoa community is about land management. Overlapping land use and tenure uncertainties are prevalent in Indonesia [50]; meanwhile, the Ammatoa community, with its local knowledge, has understood the importance of land use according to geographical conditions. Land use planning is necessary to ensure that the carrying capacity of the environment is maintained. There is a potential for ILK to build a creative understanding of the local environment, which not only illustrates ecological information but also supports management strategies and encourages adaptive capacity to environmental variability [21,22]. Therefore, ILKs are considered to be able to contribute to creating a resilient landscape, and identify climate change threats based on the knowledge they have practiced for centuries [5]. In the ILK context, the Ammatoa community regulated land use, including settlements, agriculture, and forests, to ensure land use follows the environment’s carrying capacity.

The sustainability value adopted by the Ammatoa community also includes SDG 12, where long-term development and economic growth depend on changing how we produce and consume goods. The Ammatoa community, which has a simple life concept, is very concerned about consuming and managing natural resources in their customary territory. Furthermore, local knowledge of the Ammatoa community in building resilient and sustainable settlements is regulated in more detail. Customary rules have been held, e.g., the materials used must be local materials that are easily available in customary areas; infrastructure materials that should not interfere with the passage of water; home orientation; minimalist and functional parts of the house. It is related to the selection of local materials and effective planning to minimize the use of resources, especially in building residential areas and infrastructure.

The customary rules govern a minimalist and functional home model. In addition, the materials used must be local ones that are easily available in customary areas and environmentally friendly. Their concept of settlements is closely related to sustainable consumption. The traditional values demand more efficient and environmentally friendly management of materials across the lifecycle, through production, consumption, and disposal.

Besides that, the modest life practiced by the Ammatoa community is not fully applicable outside the customary area. Of course, implementing their rejection of modernity will be a difficult task. Nowadays, humans have many heterogeneous activities and need infrastructure that can help them move quickly and efficiently. Therefore, humans outside the customary area need a modern transportation system, internet, and electricity. In this case, we can only take lessons about consumption and production patterns from the Ammatoa community linked to economic activity. As a result of uncontrolled consumption, residents of many parts of the world consume enormous resources and produce large volumes of waste to maintain their lifestyles [51]. The current environmental damage is due to economic development, increasing human needs, and ignorance of natural resources [52]. Therefore, we can learn from ILK that the developing customary system can shape a life that applies to the values of sustainable development, not only in the social field but also includes the interconnected economy and environment. The Ammatoa community believes that logging or overexploiting natural resources will disrupt the natural cycle and lead to disaster.

Although much research on the use of ILKs has been carried out, the strategic use of knowledge by actors (including scientists) and institutional barriers to linking knowledge to action at various scales are still obstacles. Bridging valuable and equitable knowledge for indigenous and non-indigenous communities is the key to ensuring that knowledge can be used in sustainability efforts. These insights and innovations from indigenous and local knowledge systems can strengthen the efforts of industrial communities in the transformation toward biosphere management [53]. By considering values that can be learned from indigenous local knowledge, practical methods can be developed to operationalize the evaluation of local socio-ecological systems to assist in governance planning and management of land and resource systems in our modern lifestyle system.

3.6. Study Limitation and Recommendation for Future Research

There are some limitations of this study. First, we did not investigate in detail the socio-economic conditions of the community and how the practiced ILK influences those conditions. We have some related discussions in this draft, but we consider it worth studying further. Furthermore, a historical aspect of the ILK should be studied further. It can reveal the changes in ILK and its practice in a certain time frame.

This study can be seen as a starting point to study other ILKs, not only in Indonesia but also in other regions, concerning their social–ecological system to conserve the natural environment. One can then compare various ILK related to environmental management and how they can be integrated into our modern situations. In addition, one should also analyze the role or influence of the people living in the surrounding customary areas or outside information in influencing the ILK, especially the ILK related to environmental management. Finally, we believe that ILK should be considered in the development of any regulation related to environmental conservation, which can also preserve the ILK itself from extinction.

4. Conclusions

Indigenous local knowledge (ILK) that is practiced by the Ammatoa community has formed their social–ecological system to maintain their culture and customary land. The modest principle of living leads them to a more sustainable and friendly way of life for the environment. Furthermore, they believe that breaking customary rules can result in diseases, including breaking rules about how they should utilize natural resources in their customary area. This can be seen, for example, in the way they use materials to build their houses without excessively exploiting natural resources. The ILK also indirectly force them not to apply any modernization development that may interrupt environmental balance, e.g., water absorption. The customary area is divided in such a way that let them preserve the natural condition in their customary areas. For example, forest management is regulated by the Ammatoa’s ILK which forbids over-exploitation of the forest. All those ILKs show the integration of social and ecological practices for the balance of nature.

The main lesson that can be learned from the Ammatoa community is related to the SGD 15, i.e., protect, restore and promote sustainable use of terrestrial ecosystems, sustainably manage forests, combat desertification, halt and reverse land degradation and halt biodiversity loss; and SDG 12, i.e., ensure sustainable consumption and production patterns. More specifically, we could learn from them how they are able to manage their forest area sustainably, how land management is properly applied, e.g., no overlapping land use, and how their simple or modest life influences their consumption practices.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: D.D., S.S. and A.E.; methodology: D.D., S.S. and A.E.; validation: D.D., S.S., S.L.Z. and A.E.; formal analysis: S.S.; writing—original draft: D.D. and S.S.; writing—review and editing: D.D., S.S. and A.E.; visualization: S.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The third author receives master’s research funding from Indonesia Endowment Fund for Education (LPDP).

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

We thank all participants of this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Yiannakou, A.; Eppas, D.; Zeka, D. Spatial interactions between the settlement network, natural landscape and zones of economic activities: Case study in a Greek Region. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Partelow, S. A review of the social-ecological systems framework: Applications, methods, modifications, and challenges. Ecol. Soc. 2018, 23, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, J.; Gardner, T.A.; Bennett, E.M.; Balvanera, P.; Biggs, R.; Carpenter, S.; Daw, T.; Folke, C.; Hill, R.; Hughes, T.P.; et al. Advancing sustainability through mainstreaming a social-ecological systems perspective. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2015, 14, 144–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkes, F.; Colding, J.; Folke, C. Rediscovery of traditional ecological knowledge as adaptive management. Ecol. Appl. 2000, 10, 1251–1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, P.A.; Sikutshwa, L.; Shackleton, S. Acknowledging indigenous and local knowledge to facilitate collaboration in landscape approaches- lessons from a systematic review. Land 2020, 9, 331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. The Unesco Expert Meeting on Indigenous Knowledge and Climate Change in Africa; UNESCO: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Daniel, D. Contextual determinants of general household hygiene conditions in rural indonesia. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 11064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popp, J. How Indigenous Knowledge Advances Modern Science and Technology. The Conversation. 2018. Available online: https://theconversation.com/how-indigenous-knowledge-advances-modern-science-and-technology-89351 (accessed on 27 February 2022).

- Hill, R.; Díaz, S.; Pascual, U.; Stenseke, M.; Molnár, Z.; Van Velden, J. Nature’s contributions to people: Weaving plural perspectives. One Earth 2021, 4, 910–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgos-Ayala, A.; Jiménez-Aceituno, A.; Torres-Torres, A.M.; Rozas-Vásquez, D.; Lam, D.P.M. Indigenous and local knowledge in environmental management for human-nature connectedness: A leverage points perspective. Ecosyst. People 2020, 16, 290–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Shui, W.; Li, Z.; Huang, S.; Wu, K.; Sun, X.; Liang, J. Green space optimization for rural vitality: Insights for planning and policy. Land Use Policy 2021, 108, 105545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamila, N.; Wisnu, I.; Endro, W.; Parkinson, M. Perencanaan Sistem Drainase Berwawasan Lingkungan (Ecodrainage). J. Tek. Lingkung. 2016, 22, 63–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samad, I.D.; Niswaty, R.; Agus, A.A.; Arman, A. Learning Environmental Lessons from Indegenous Ammatoa Kajang to Preserve the Forest. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2021, 1899, 012150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surtikanti, H.K.; Syulasmi, A.; Ramdhani, N. Traditional Knowledge of Local Wisdom of Ammatoa Kajang Tribe (South Sulawesi) about Environmental Conservation. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2017, 895, 12122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowak, A.; Tokarczyk, N. Transformations of traditional land use and settlement patterns of Kosarysche Ridge (Chornohora, Western Ukraine). Bull. Geogr. 2014, 24, 191–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruchac, M.M. Indigenous Knowledge and Traditional Knowledge. In Encyclopedia of Global Archaeology; Department of Anthropology Papers; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; pp. 5686–5696. [Google Scholar]

- Daniel, D.; Djohan, D.; Machairas, I.; Pande, S.; Arifin, A.; Al Djono, T.P.; Rietveld, L. Financial, institutional, environmental, technical, and social (FIETS) aspects of water, sanitation, and hygiene conditions in indigenous—Rural Indonesia. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 1723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, H.; Subramanian, S.M. Drivers of change in socio-ecological production landscapes: Implications for better management. Ecol. Soc. 2014, 19, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wohling, M. The problem of scale in indigenous knowledge: A perspective from Northern Australia. Ecol. Soc. 2009, 14, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azis, S.; Zubaidah, S.; Mahanal, S.; Batoro, J.; Sumitro, S.B. Local knowledge of traditional medicinal plants use and education system on their young of ammatoa kajang tribe in south sulawesi, indonesia. Biodiversitas J. Biol. Divers. 2020, 21, 3989–4002. [Google Scholar]

- Alayasa, J.Y. Building on the Strengths of Indigenous Knowledge to Promote Sustainable Development in Crisis Conditions from the Community Level: The Case of Palestine; Portland State University: Portland, OR, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Mccarter, J.; Gavin, M.C.; Baereleo, S.; Love, M. The challenges of maintaining indigenous ecological knowledge. Ecol. Soc. 2014, 19, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andiarsi, M.K. Sebaran Masyarakat Adat. Katadata.co.id. 2020. Available online: https://katadata.co.id/padjar/infografik/5f8030631f92a/sebaran-masyarakat-adat (accessed on 5 February 2022).

- Berger, D.N.; Bulanin, N.; García-Alix, L.; Jensen, M.W.; Leth, S.; Madsen, E.A.; Mamo, D.; Parelladaa, A.; Rose, G.; Thorsell, S.; et al. The Indigenous World 2021; International Work Group for Indigenous Affairs: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Musi, S.; Fitriana, F. Pola Komunikasi Ammatoa dalam Melestarikan Kearifan Lokal Melalui Nilai Kamase-Masea di Kajang. Komodifikasi 2019, 7, 257–290. [Google Scholar]

- Chaurasia, N.K.; Pankaj, C. Case study as a research method. Int. J. Inf. Dissem. Technol. 2011, 1, 34–39. [Google Scholar]

- McGinnis, M.D.; Ostrom, E. Social-ecological system framework: Initial changes and continuing challenges. Ecol. Soc. 2014, 19, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nurmala, N.; Dassir, M.; Supratman, S. “Pasang”, Knowledge and Implementation of Local Wisdom in The Kajang Traditional Forest Area, South Sulawesi. Pusaka J. Tour. Hosp. Travel Bus. Event 2022, 4, 40–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hijjang, P. Pasang and Traditional Leadership Ammatoa Indigenous Communities in Forest Resources Management. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Ethics in Governance (ICONEG 2016), Makassar, Indonesia, 19–20 December 2016; Atlantis Press: Paris, France, 2017; pp. 365–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rusdiansyah, R. Sumur dan Budaya Suku Kajang; Kearifan Lokal Suku Kajang. J. Commer. 2019, 2, 29–35. [Google Scholar]

- Juhannis, H.; Nildawati Habibi Satrianegara, M.F.; Amansyah, M.; Syarifuddin, N. Community beliefs toward causes of illness: Cross cultural studies in Tolotang and Ammatoa Ethnics in Indonesia. Gac. Sanit. 2021, 35, S19–S22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- United Nations. State of the World’s Indigenous Peoples: Indigenous Peoples’ Access to Health Services; United Nations: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2016; Available online: https://www.un.org/development/desa/indigenouspeoples/wp-content/uploads/sites/19/2018/03/The-State-of-The-Worlds-Indigenous-Peoples-WEB.pdf (accessed on 27 July 2022).

- Azis, S.; Zubaidah, S.; Mahanal, S.; Sulisetijono Sumitro, S.B. The Ammatoa Kajang’s knowledge, attitude, and practice of medicinal plants used for respiratory disorders remedy. AIP Conf. Proc. 2021, 2330, 030034. [Google Scholar]

- Fadila, L.N.; Handoko, A.S.; Uliyah, L.; Yulanty, C.; Tanduru, J.; Syafruddin, P. Badan Registrasi Wilayah Adat (BRWA). 2019. Available online: https://brwa.or.id/assets/image/rujukan/1580800885.pdf (accessed on 27 July 2022).

- Osman, W.W.; Wunas, D.S.; Arifin, M.; Wikantari, R. The Spatial Patterns of Settlement Plateau of The Ammatoa Kajang: Reflection of Local Wisdom. Int. J. Civ. Eng. Technol. 2020, 11, 199–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arisaputri, S.B.N. Pola Ruang Permukiman Berdasarkan Kearifan Lokal Kawasan Adat Ammatoa Kecamatan Kajang Kabupaten Bulukumba (Settlement Space Pattern Based on Local Wisdom Ammatoa Traditional Areakajang District Bulukumba Regency). Ph.D. Thesis, ITN Malang, Malang, Indonesia, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Weir, W. Asphalt Adds to Air Pollution, Especially on Hot, Sunny Days. Yale News. 2020. Available online: https://news.yale.edu/2020/09/02/asphalt-adds-air-pollution-especially-hot-sunny-days#:~:text=Yale researchers observed that common,typical temperature and solar conditions (accessed on 20 November 2022).

- Mukhlisa, N. An Overview of Hyigiene and Sanitation from a Socio Antrhopoligacl Perspective on Kajang Ethnic; State Islamic University of Alauddin Makassar: Makasar, Indonesia, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Kambo, G.A. Local wisdom Pasang ri Kajang as a political power in maintaining indigenous people’s rights. J. Etnogr. Indones. 2021, 6, 265–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahbub, M.A.S.; Salman, D.; Malamassam, D.; Dassir, M.; Ibrahim, T.; Hajawa, H. Indigenous and Non-Indigenous Knowledges Dialectics in Management of Kajang Customary Forest, District of Bulukumba, South Sulawesi. Int. J. Sci. Basic Appl. Res. Int. J. Sci. Basic Appl. Res. 2018, 42, 195–204. Available online: http://gssrr.org/index.php?journal=JournalOfBasicAndApplied (accessed on 30 July 2022).

- Akbal, M.; Umar, F. Adat Law-Based in Developing Environment on Forest Management of Ammatoa. Adv. Soc. Sci. Educ. Hum. Res. 2020, 226, 983–987. [Google Scholar]

- Van der Muur, W.; Bedner, A. Traditional Rule As “Modern Governance”: Recognising the Ammatoa Kajang Adat Law Community. Mimb. Huk.—Fak. Huk. Univ. Gadjah Mada 2016, 28, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syarif, E.; Fatchan, A.; Sumarmi; Astina, K. Tradition of “Pasang Ri-Kajang” in the Forests Managing in System Mores of “Ammatoa” at District Bulukumba South Sulawesi, Indonesia. Mediterr. J. Soc. Sci. 2016, 7, 325–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Embas, A.R.; Nas, J. Analisis Sistem Pemerintahan Desa Adat Ammatoa Dalam Pelestarian Lingkungan Hidup Di Kecamatan Kajang, Kabupaten Bulukumba. Ilmu Pemerintah. 2017, 10, 30–37. [Google Scholar]

- Imran, K.; Pratama, W.A.; Pratama, W.A. Penguatan Hak-Hak Masyarakat Hukum Adat Ammatoa Kajang Sebagai Wujud Realisasi Putusan Mahkamah Konstitusi Nomor 35/PUU-X/2012. Legislatif 2020, 3, 254–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maarif, S.; Azis, A.; Setiani, P. Pembangunan nasional: Kearifan lokal sebagai sarana dan target community building untuk komunitas Ammatoa. Masy. Kebud. Dan Polit. 2013, 26, 167–181. [Google Scholar]

- Hijjang, P. Pasang dan Kepemimpinan Ammatoa: Memahami Kembali Sistem Kepemimpinan Tradisional Masyarakat Adat dalam Pengelolaan Sumberdaya Hutan di Kajang Sulawesi Selatan. Antropol. Indones. 2014, 29, 255–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayer, J.; Sheil, D.; Galloway, G.; Riggs, R.A.; Mewett, G.; MacDicken, K.G.; Arts, B.; Boedhihartono, A.K.; Langston, J.; Edwards, D.P.; et al. SDG 15: Life on land-The central role of forests in sustainable development. In Sustainable Development Goals: Their Impacts on Forests and People; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2019; pp. 482–509. [Google Scholar]

- Schiffman, R. Lessons Learned from Centuries of Indigenous Forest Management. YaleEnvironment360. 2018. Available online: https://e360.yale.edu/features/lessons-learned-from-centuries-of-indigenous-forest-management (accessed on 4 October 2022).

- Ridhwan, D.; Astri, C.; Taufik, A.A.; Affandi, D.; Fajar, M.; Lawalata, J. Improving the Lives of Indigenous Communities through Mapping: A Case Study from Indonesia. WRI Indones. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kissinger, M.; Sussman, C.; Moore, J.; Rees, W.E. Accounting for the ecological footprint of materials in consumer goods at the urban scale. Sustainability 2013, 5, 1960–1973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, R.B. Yes, Humans Are Depleting Earth’s Resources, but ‘Footprint’ Estimates Don’t Tell the Full Story. The Conversation. 2018. Available online: https://theconversation.com/yes-humans-are-depleting-earths-resources-but-footprint-estimates-dont-tell-the-full-story-100705 (accessed on 2 March 2022).

- Hill, R.; Malmer, P.; Raymond, C.M.; Spierenburg, M.; Danielsen, F.; Elmqvist, T.; Folke, C. Weaving knowledge systems in IPBES, CBD and beyond—Lessons learned for sustainability. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2016, 26–27, 17–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).