Analysis of Core Temperature Dynamics in Multi-Core Processors

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Related Work

3. Methodology

3.1. Data Set Generation

3.2. Preprocessing of Data

3.3. Feature Extraction

4. Results

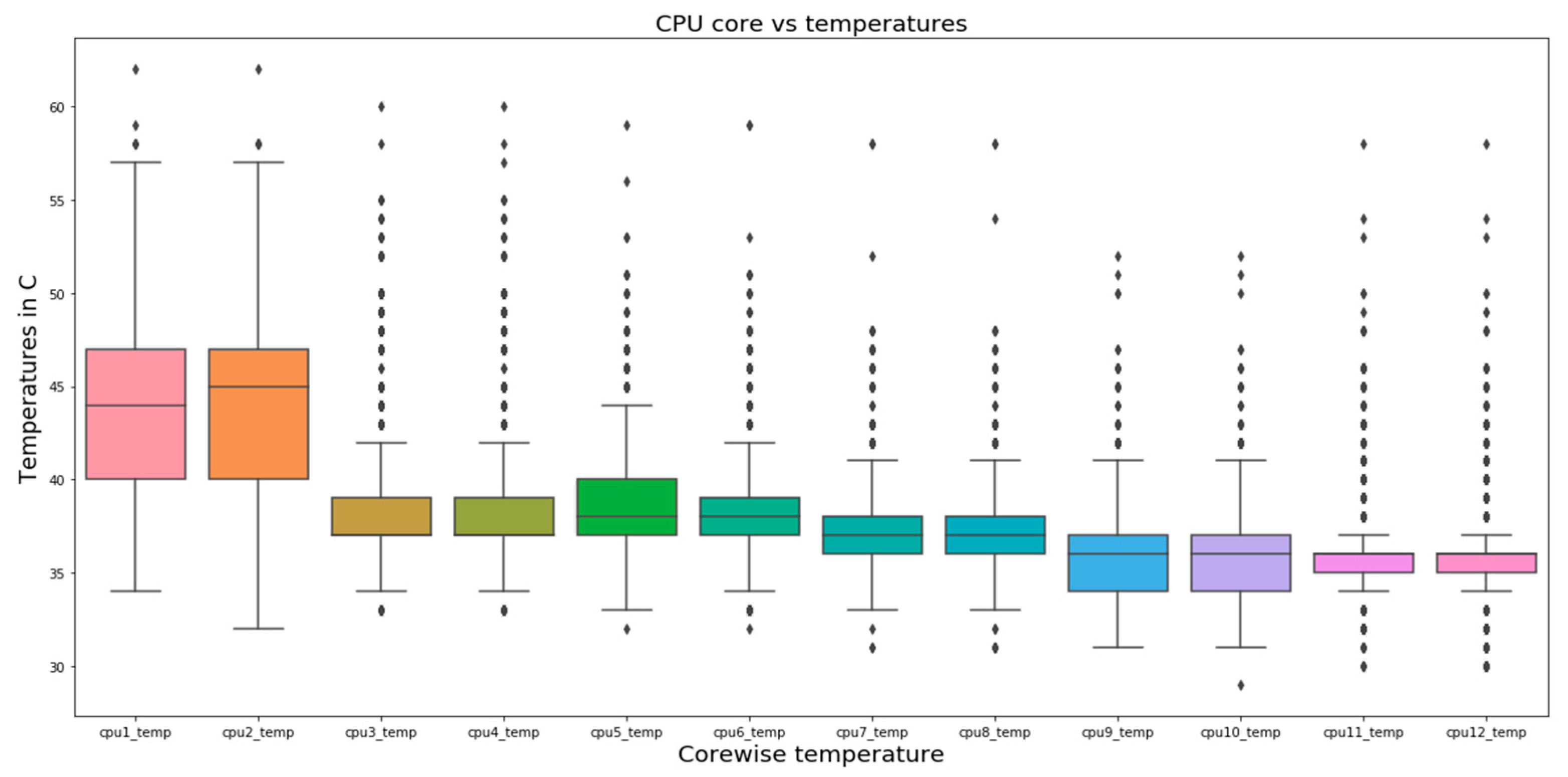

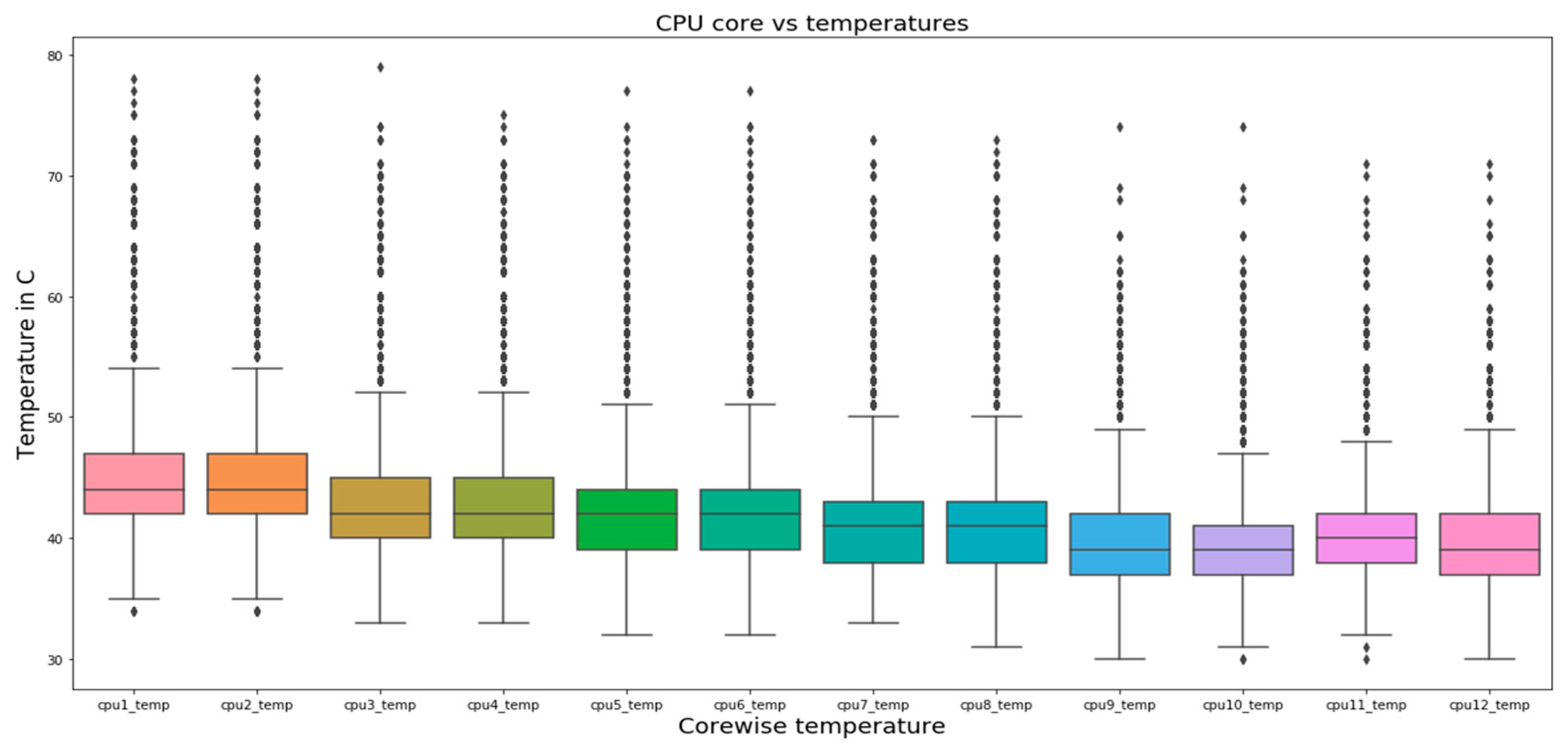

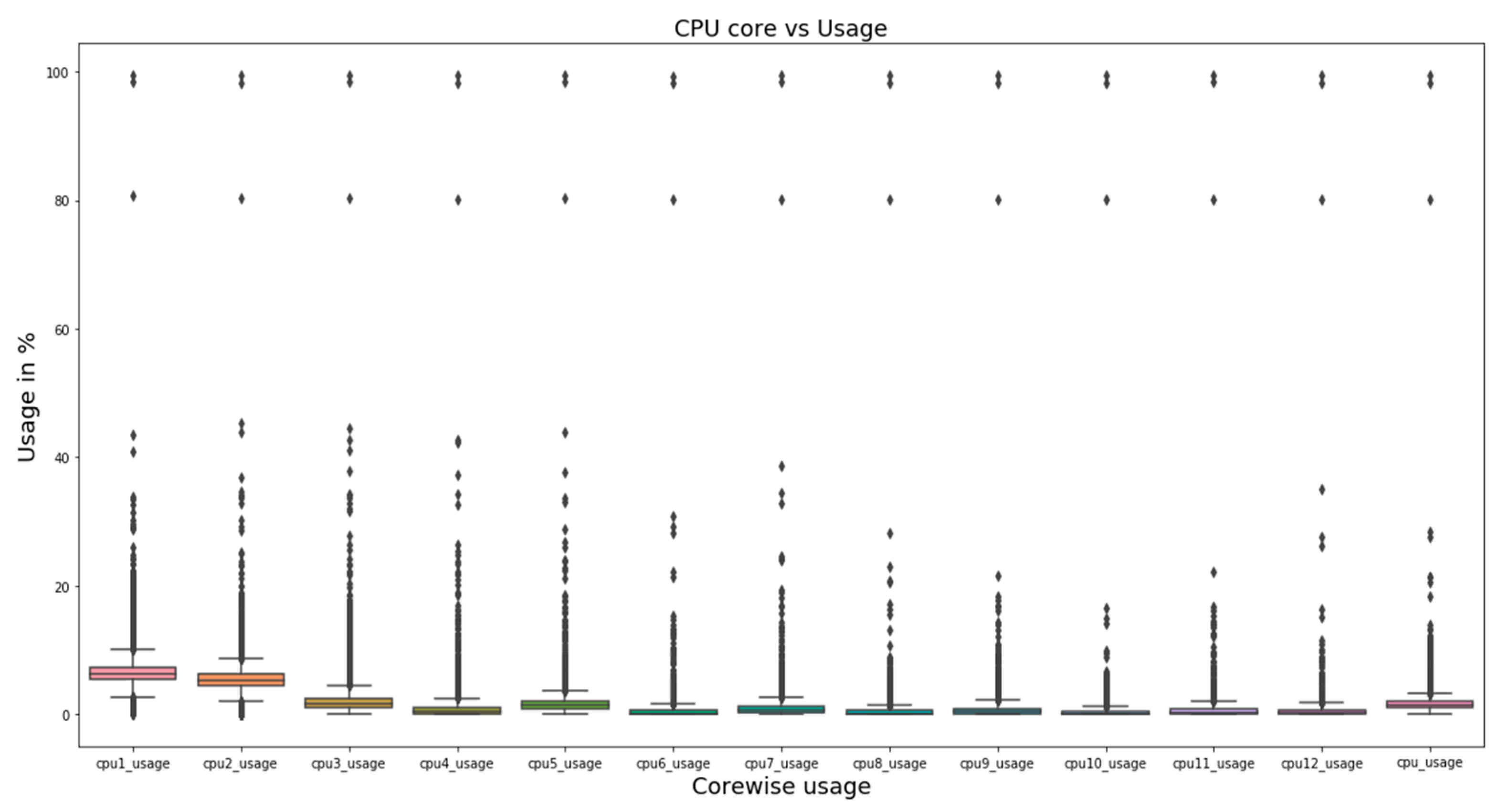

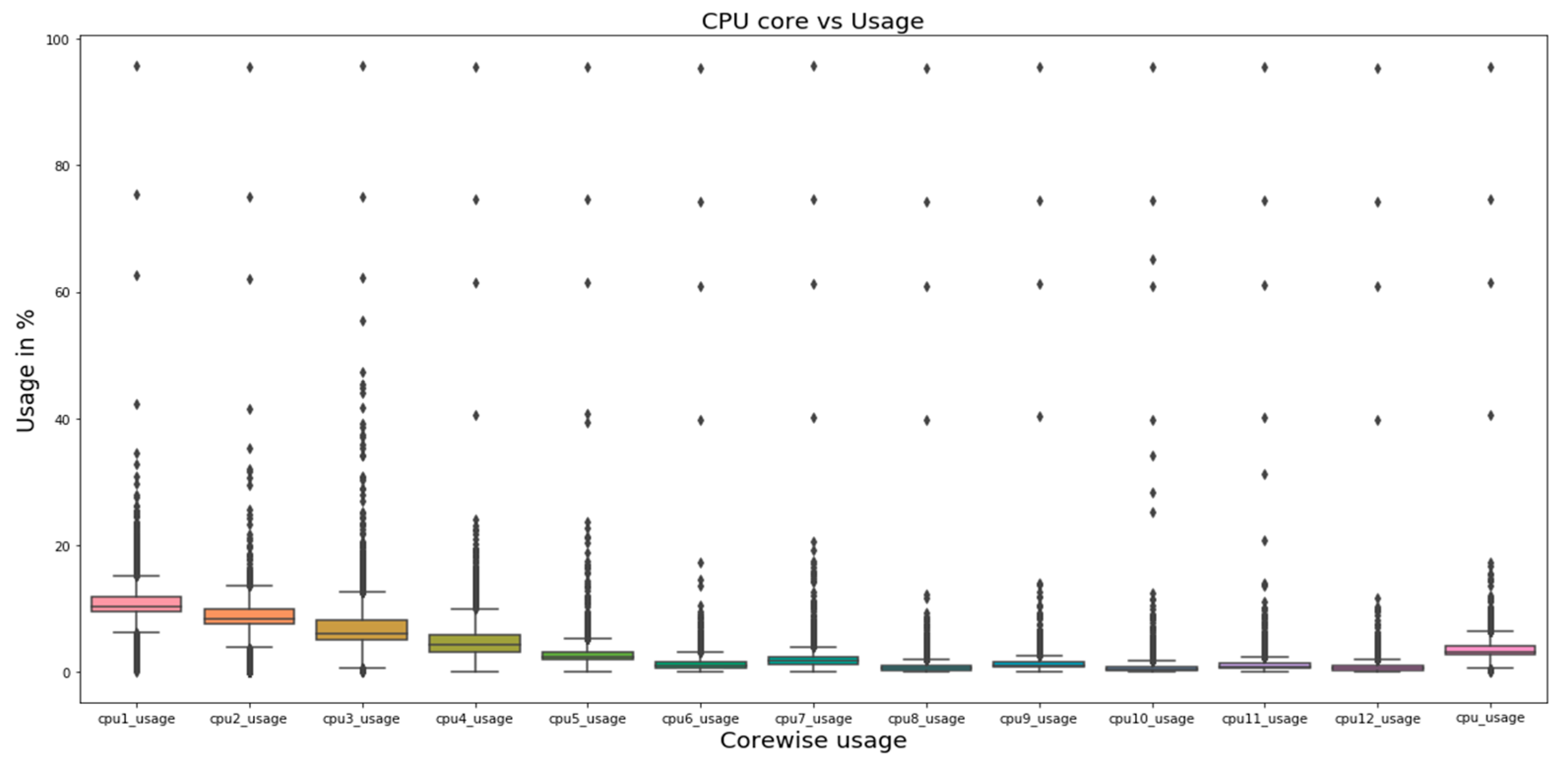

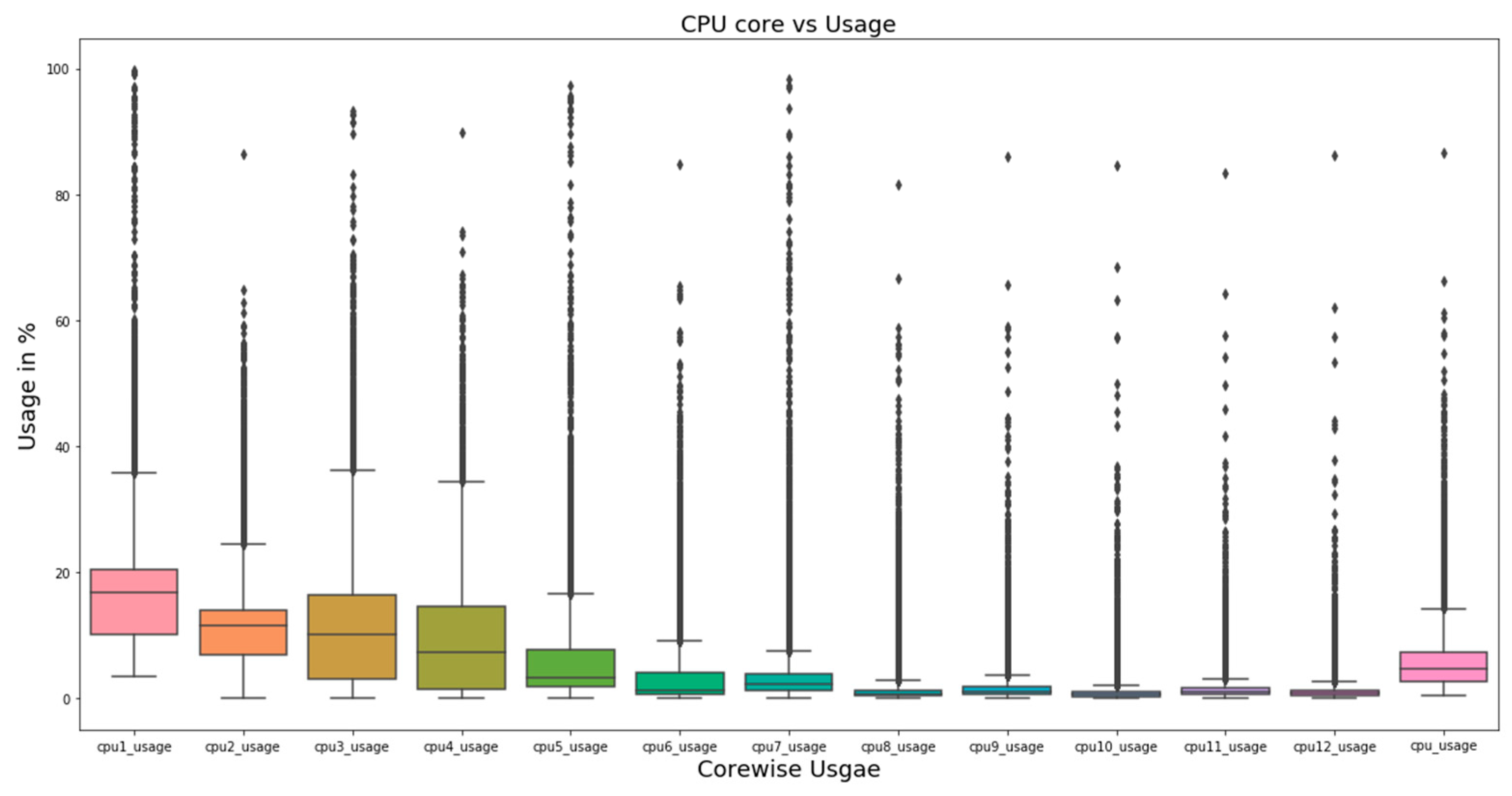

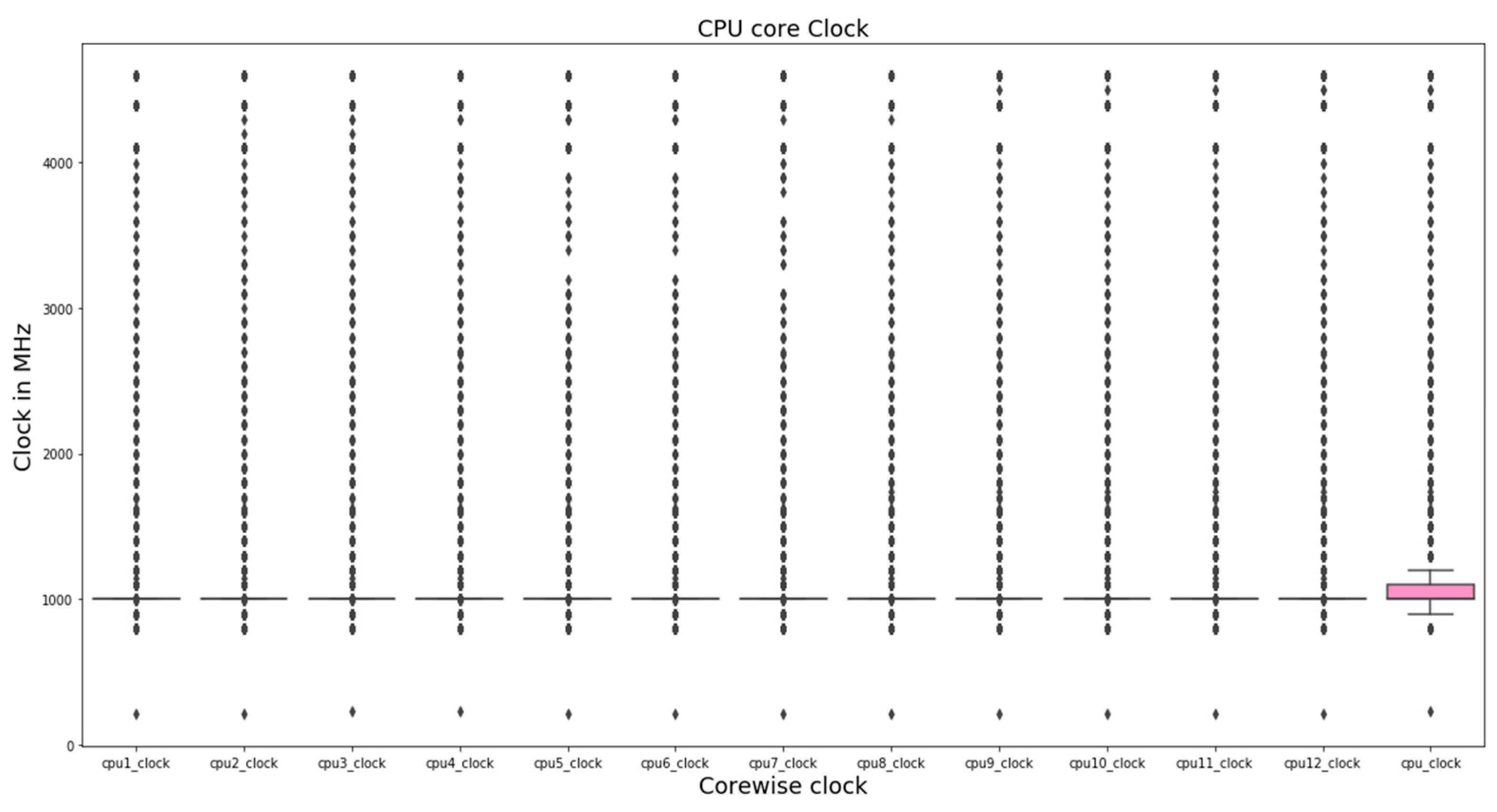

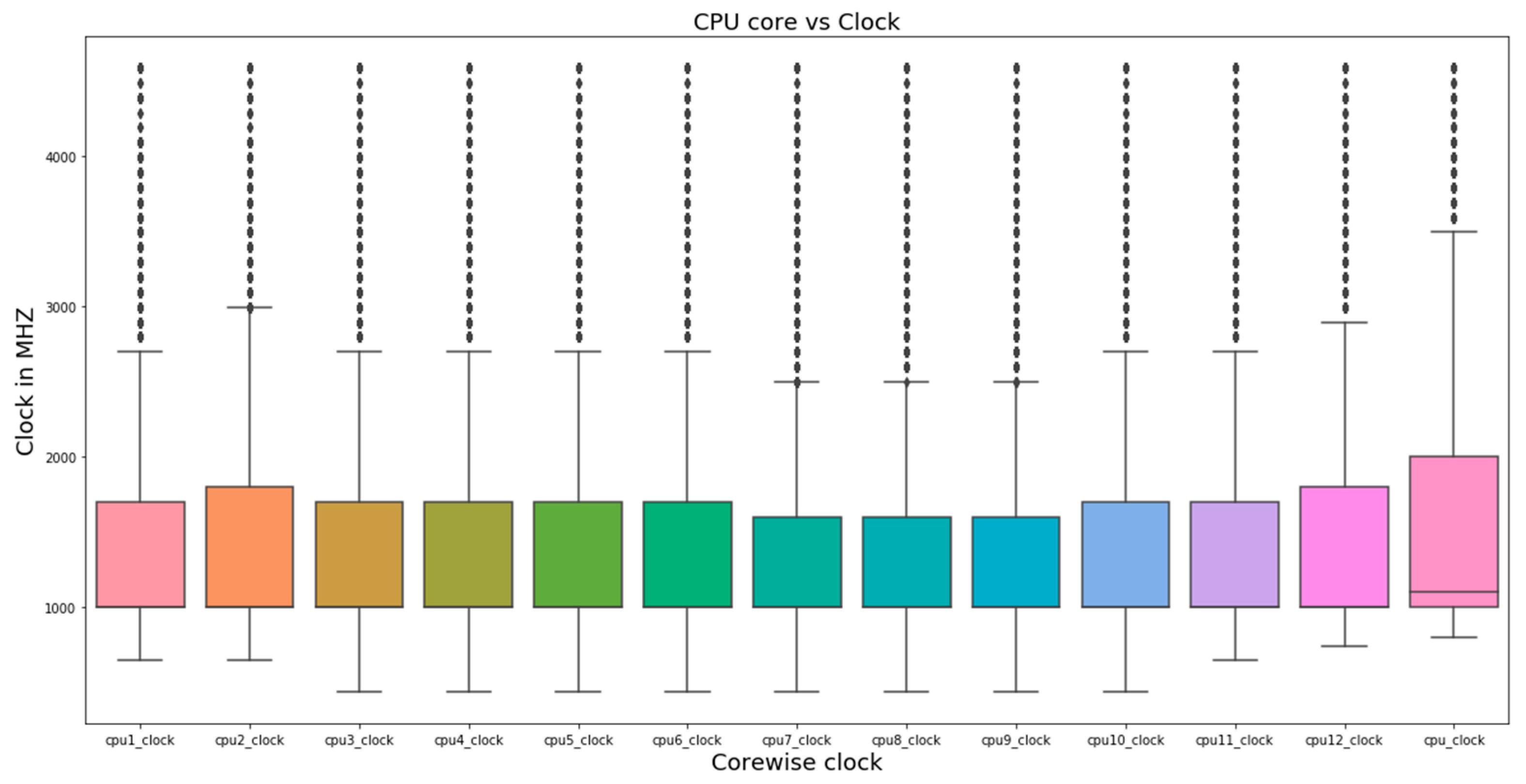

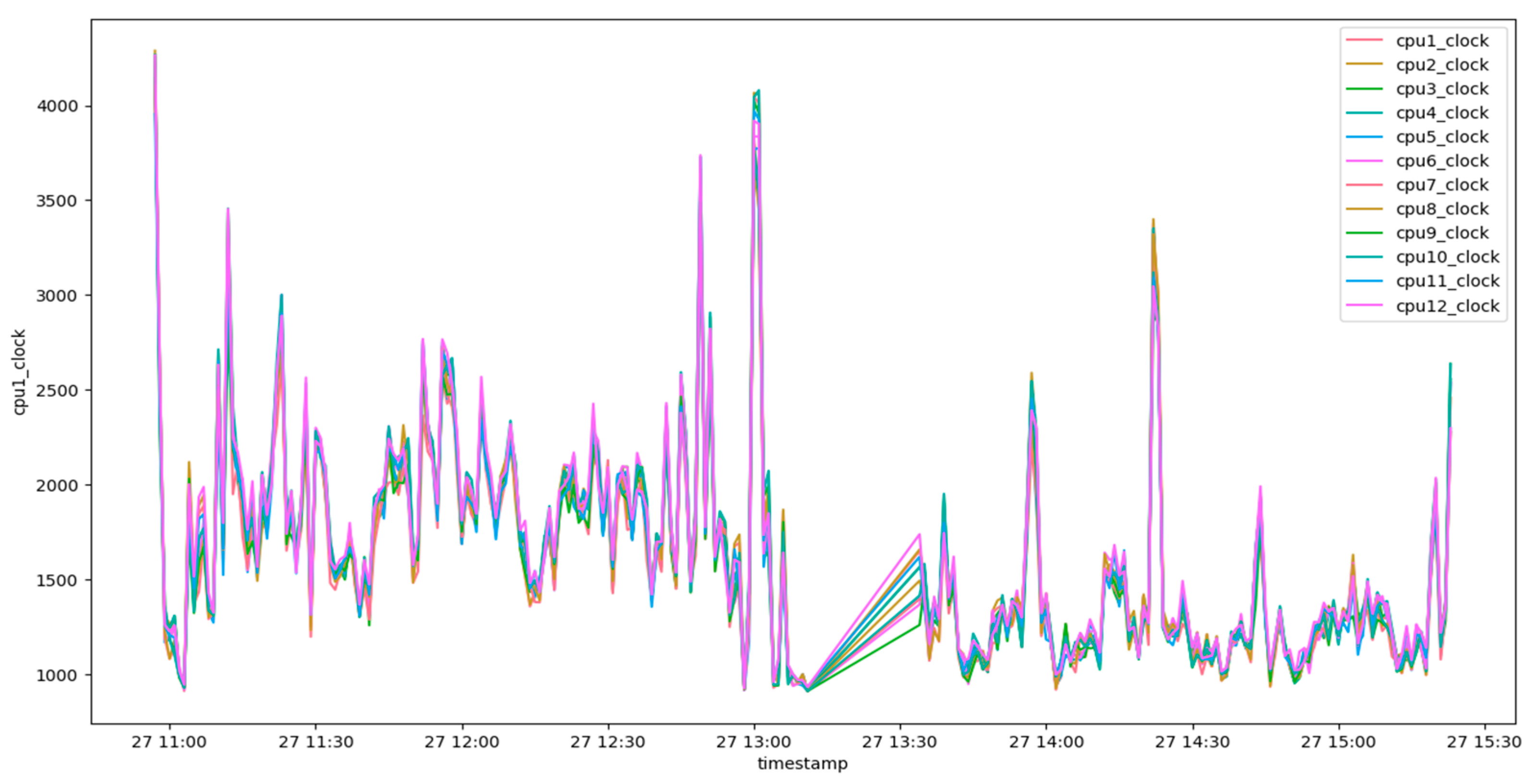

4.1. Single-Variate Analysis

4.2. Multivariate Analysis

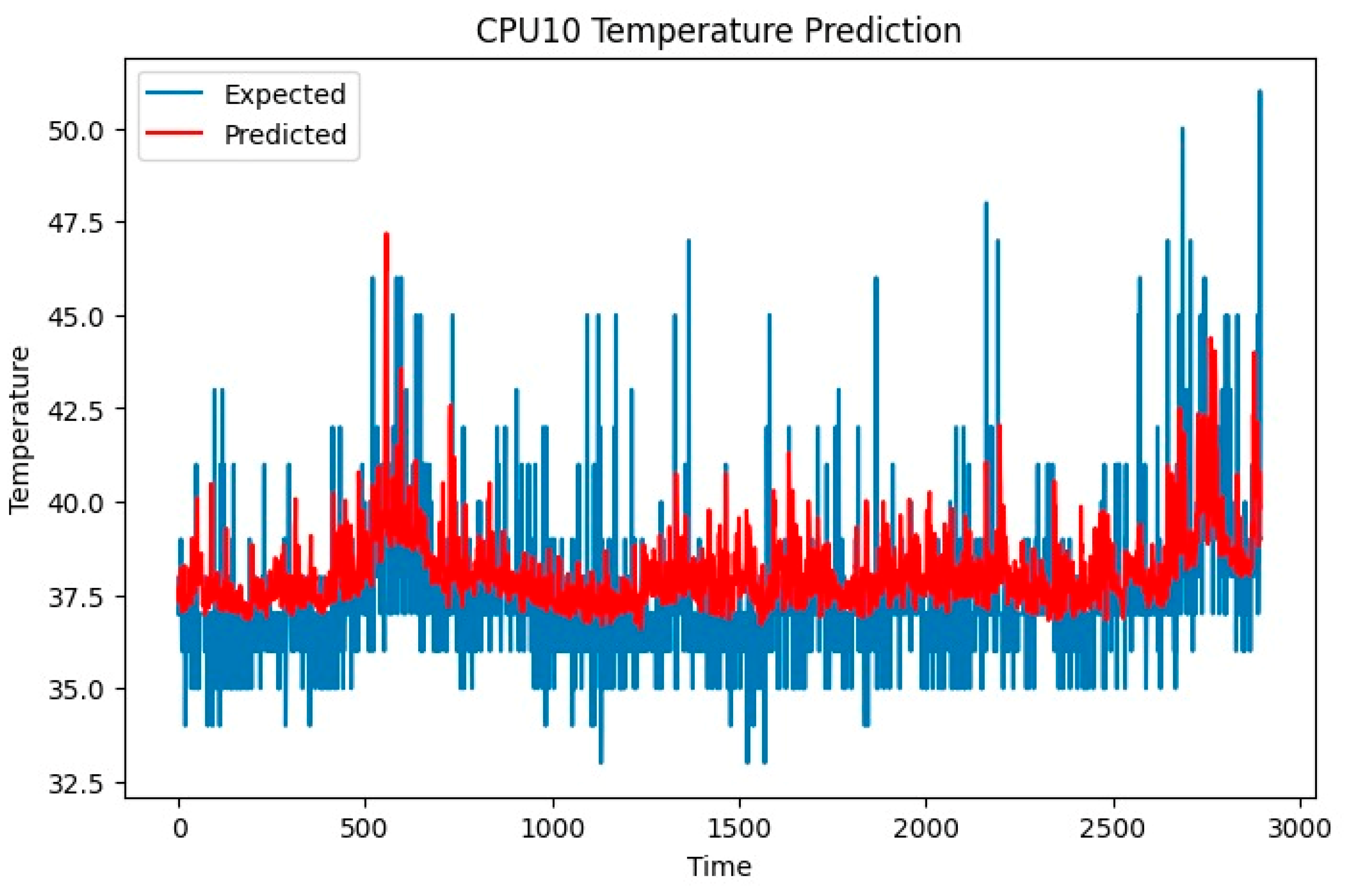

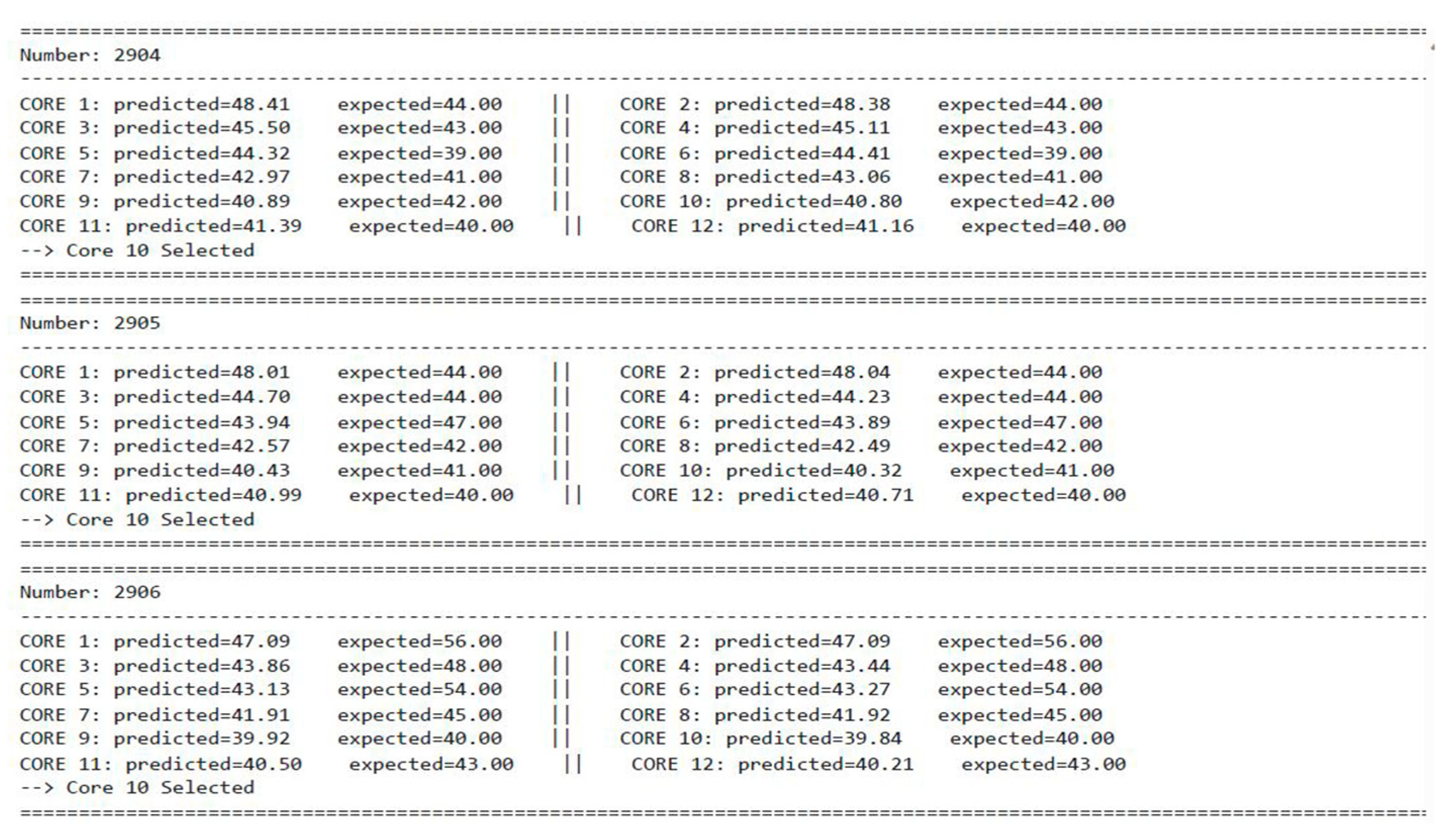

4.3. Estimation of Core Temperature

- T = predicted core temperature (°C)

- = independent variables

- = intercept term (baseline temperature when all )

- = regression coefficients representing the sensitivity of temperature to each variable

- = random error term

- T = predicted core temperature (°C)

- = independent variable

- = degree of the polynomial

- = model coefficients

- = random error term

- Yt = actual value at time t;

- c = constant term;

- p = order of the AutoRegressive (AR) part;

- φi = AR coefficients;

- d = degree of differencing;

- q = order of the Moving Average (MA) part;

- θj = MA coefficients;

- εt = white noise error term.

5. Discussion

5.1. Single-Variate Analysis

5.2. Multivariate Analysis

5.3. Estimation of Core Temperature

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Singh, A.K.; Dey, S.; McDonald-Maier, K.; Basireddy, K.R.; Merrett, G.V.; Al-Hashimi, B.M. Dynamic energy and thermal management of multi-core mobile platforms: A survey. IEEE Des. Test 2020, 37, 25–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Everman, B.; Villwock, T.; Chen, D.; Soto, N.; Zhang, O.; Zong, Z. Evaluating the Carbon Impact of Large Language Models at the Inference Stage. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE International Performance, Computing, and Communications Conference (IPCCC), Anaheim, CA, USA, 17–19 November 2023; pp. 150–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borkar, S. Thousand core chips: A technology perspective. In Proceedings of the 44th Annual Design Automation Conference, New York, NY, USA, 4–8 June 2007; pp. 746–749. [Google Scholar]

- Mishra, A.; Tripathi, A.K. Energy efficient voltage scheduling for multi-core processors with software controlled dynamic voltage scaling. Appl. Math. Model. 2014, 38, 3456–3466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kok, C.L.; Ho, C.K.; Aung, T.H.; Koh, Y.Y.; Teo, T.H. Transfer Learning and Deep Neural Networks for Robust Intersubject Hand Movement Detection from EEG Signals. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 8091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stavrou, K.; Trancoso, P. Thermal-aware scheduling for future chip multiprocessors. EURASIP J. Embed. Syst. 2007, 2007, 048926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roeder, J.; Rouxel, B.; Altmeyer, S.; Grelck, C. Energy-aware scheduling of multi-version tasks on heterogeneous real-time systems. In Proceedings of the 36th Annual ACM Symposium on Applied Computing, New York, NY, USA, 22–26 March 2021; pp. 501–510. [Google Scholar]

- Ladge, L.; Rao, Y.S. Study of temperature and power consumption in embedded processors. In Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on Computing in Engineering & Technology (ICCET 2022), Online Conference, 12–13 February 2022; pp. 331–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Rodríguez, J.; Yomsi, P.; Zaykov, P. A Thermal-Aware Approach for DVFS-Enabled Multi-Core Architectures. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Embedded Systems, Chengdu, China, 18–21 December 2022; pp. 1904–1911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, M.; Singh, K.; Kumar, S. Adaptive Behavior-Driven Thermal Management Framework in Heterogeneous Multi-Core Processors. Microprocess. Microsyst. 2021, 87, 104392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bashir, Q.; Pivezhandi, M.; Saifullah, A. Energy- and Temperature-Aware Scheduling: From Theory to an Implementation on Intel Processor. IEEE Trans. Comput.-Aided Des. Integr. Circuits Syst. 2022, 41, 1674–1687. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, J.; Wang, H.; Gong, G.; Wang, L.; Chen, X. An Efficient Multi-Core DSP Power Management Controller. Eng. Rep. 2025, 4, e13050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Martín, E.; Rodrigues, C.F.; Riley, G.; Grahn, H. Estimation of energy consumption in machine learning. J. Parallel Distrib. Comput. 2019, 134, 75–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheikh, H.F.; Ahmad, I.; Wang, Z.; Ranka, S. An overview and classification of thermal-aware scheduling techniques for multi-core processing systems. Sustain. Comput. Inform. Syst. 2012, 2, 151–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, G.; Xu, Z. Temperature-aware task scheduling algorithm for soft real-time multi-core systems. J. Syst. Softw. 2010, 83, 2579–2590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhat, G.; Singla, G.; Unver, A.K.; Ogras, U.Y. Algorithmic optimization of thermal and power management for heterogeneous mobile platforms. IEEE Trans. Very Large Scale Integr. Syst. 2018, 26, 544–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.G.; Kong, J.; Chung, S.W. A survey on recent OS-level energy management techniques for mobile processing units. IEEE Trans. Parallel Distrib. Syst. 2018, 29, 2388–2401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rupanetti, D.; Salamy, H. Task allocation, migration and scheduling for energy-efficient real-time multiprocessor architectures. J. Syst. Archit. 2019, 98, 17–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abou-Of, M.A.; Sedky, A.A.; Taha, A.H. Power-energy simulation for multi-core processors in benchmarking. Adv. Sci. Technol. Eng. Syst. J. 2017, 2, 255–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Han, Q.; Fan, M.; Bai, O.; Ren, S.; Quan, G. Temperature-constrained feasibility analysis for multicore scheduling. IEEE Trans. Comput.-Aided Des. Integr. Circuits Syst. 2016, 35, 2082–2092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanumaiah, V.; Vrudhula, S. Temperature-aware DVFS for hard real-time applications on multicore processors. IEEE Trans. Comput. 2012, 61, 1484–1494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Wei, T.; Chen, M.; Yan, J.; Hu, X.S.; Ma, Y. Thermal-aware task scheduling for energy minimization in heterogeneous real-time mpsoc systems. IEEE Trans. Comput.-Aided Des. Integr. Circuits Syst. 2015, 35, 1269–1282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhat, G.; Gumussoy, S.; Ogras, U.Y. Power–Temperature Stability and Safety Analysis for Multiprocessor Systems. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1806.06180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuravlev, S.; Saez, J.C.; Blagodurov, S.; Fedorova, A.; Prieto, M. Survey of energy-cognizant scheduling techniques. IEEE Trans. Parallel Distrib. Syst. 2012, 24, 1447–1464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bambagini, M.; Marinoni, M.; Aydin, H.; Buttazzo, G. Energy-aware scheduling for real-time systems: A survey. ACM Trans. Embed. Comput. Syst. 2016, 15, 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kok, C.L.; Li, X.; Siek, L.; Zhu, D.; Kong, J. A Switched-Capacitor Deadtime Controller for DC–DC Buck Converter. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2019, 34, 5678–5687. [Google Scholar]

- Kok, C.L.; Siek, L. Designing a Twin Frequency Control DC–DC Buck Converter Using Accurate Load Current Sensing Technique. Electronics 2023, 13, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chrobak, M.; Dürr, C.; Hurand, M.; Robert, J. Algorithms for temperature-aware task scheduling in microprocessor systems. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Algorithmic Applications in Management, Xi’an, China, 22–25 June 2005; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany; 2005; pp. 120–130. [Google Scholar]

- Coskun, A.K.; Ayala, J.L.; Atienza, D.; Rosing, T.S.; Leblebici, Y. Dynamic thermal management in 3D multicore architectures. In Proceedings of the 2009 Design, Automation & Test in Europe Conference & Exhibition, Nice, France, 20–24 April 2009; pp. 1410–1415. [Google Scholar]

- Heirman, W.; Sarkar, S.; Carlson, T.E.; Hur, I.; Eeckhout, L. Power-aware multi-core simulation for early design stage hardware/software co-optimization. In Proceedings of the 21st International Conference on Parallel Architectures and Compilation Techniques, Minneapolis, MN, USA, 19–23 September 2012; pp. 3–12. [Google Scholar]

- Tsoi, K.H.; Luk, W. Power profiling and optimization for heterogeneous multi-core systems. ACM SIGARCH Comput. Archit. News 2011, 39, 8–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, X.; Yan, L.; Li, Q.; Ge, X.; Li, Y. Modeling and optimization of power consumption for multi-core processors: A thermodynamic perspective. Results Eng. 2025, 26, 104837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mittal, S. A survey of techniques for improving energy efficiency in embedded computing systems. Int. J. Comput. Aided Eng. Technol. 2014, 6, 440–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekhtiyari, Z.; Moghaddas, V.; Beitollahi, H. A temperature-aware and energy-efficient fuzzy technique to schedule tasks in heterogeneous mpsoc systems. J. Supercomput. 2019, 75, 5398–5419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kocot, B.; Czarnul, P.; Proficz, J. Energy-aware scheduling for high-performance computing systems: A survey. Energies 2023, 16, 890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagalakshmi, K.; Gomathi, N. Analysis of power management techniques in multicore processors. In Artificial Intelligence and Evolutionary Computations in Engineering Systems: Proceedings of ICAIECES 2016; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; pp. 397–418. [Google Scholar]

- Pagani, S.; Manoj, P.D.S.; Jantsch, A.; Henkel, J. Machine learning for power, energy, and thermal management on multicore processors: A survey. IEEE Trans. Comput.-Aided Des. Integr. Circuits Syst. 2018, 39, 101–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dowling, A.; Jiang, L.; Cheng, M.-C.; Liu, Y. Regulating CPU Temperature with Thermal-Aware Scheduling. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2310.00854. [Google Scholar]

- Djedidi, O.; M’Sirdi, N.K.; Naamane, A. Adaptive Estimation of the Thermal Behavior of CPU–GPU SoCs for Prediction and Diagnosis. In Proceedings of the IMAACA 2019—International Conference on Integrated Modeling and Analysis in Applied Control and Automation, Lisbon, Portugal, 18–20 September 2019; pp. 45–51. [Google Scholar]

- Miao, D.; Duan, G.; Chen, D.; Zhu, Y.; Zheng, X. Real-Time Temperature Prediction for Large-Scale Multi-Core Chips Based on Graph Convolutional Neural Networks. Electronics 2025, 14, 1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pivezhandi, M.; Saifullah, A.; Modekurthy, P. Feature-Aware Task-to-Core Allocation in Embedded Multi-Core Platforms via Statistical Learning. In Proceedings of the IEEE 31st International Conference on Embedded and Real-Time Computing Systems and Applications (RTCSA), Singapore, 20–22 August 2025; pp. 102–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Li, W.; Zhao, X. Task Scheduling and Temperature Optimization Co-Design for Multi-Core Embedded Systems. J. Syst. Archit. 2020, 107, 101738. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher, N.A.; Chen, J.-J.; Wang, S.; Thiele, L. Thermal-Aware Global Real-Time Scheduling on Multicore Systems. Real-Time Syst. 2009, 43, 243–274. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, J.; Li, L.; Vajdi, A.; Wu, Z.; Chen, D. Temperature-Constrained Reliability Optimization of Industrial Cyber-Physical Systems Using Machine Learning and Feedback Control. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 134025–134038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, M.; Bhargava, L.; Indu, S. Mapping techniques in multicore processors: Current and future trends. J. Supercomput. 2021, 77, 9308–9363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.-G.; Wang, Y.-Y.; Liu, D.; Jiang, X.; Fang, H.; Yang, Y.; Zhao, M. Reinforcement learning for thermal-aware task allocation on multicore. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1912.00189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Yang, S.-G.; He, Z.; Zhao, M.; Liu, W. Compiler-assisted reinforcement learning for thermal-aware task scheduling and DVFS on multicores. IEEE Trans. Comput.-Aided Des. Integr. Circuits Syst. 2021, 41, 1813–1826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min-Allah, N.; Hussain, H.; Khan, S.U.; Zomaya, A.Y. Power efficient rate monotonic scheduling for multi-core systems. J. Parallel Distrib. Comput. 2012, 72, 48–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Msi. Available online: https://www.msi.com/Landing/afterburner/graphics-cards (accessed on 27 February 2024).

- Rodgers, J.L.; Nicewander, W.A. Thirteen Ways to Look at the Correlation Coefficient. Am. Stat. 1988, 42, 59–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsiramua, S.; Meladze, H.; Davitashvili, T.; Sanchez-Sáez, J.-M.; Criado-Aldeanueva, F. Structural Analysis of Multi-Core Processor and Reliability Evaluation Model. Mathematics 2025, 13, 515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Timestamp | CPU1 Temperature | CPU1 Usage | CPU1 Clock |

|---|---|---|---|

| GPU1 temperature | CPU2 temperature | CPU2 usage | CPU2 clock |

| GPU1 usage | CPU3 temperature | CPU3 usage | CPU3 clock |

| GPU2 usage | CPU4 temperature | CPU4 usage | CPU4 clock |

| GPU1 FB usage | CPU5 temperature | CPU5 usage | CPU5 clock |

| GPU1 VID usage | CPU6 temperature | CPU6 usage | CPU6 clock |

| GPU2 VID usage | CPU7 temperature | CPU7 usage | CPU7 clock |

| GPU1 BUS usage | CPU8 temperature | CPU8 usage | CPU8 clock |

| GPU1 memory usage | CPU9 temperature | CPU9 usage | CPU9 clock |

| GPU2 memory usage | CPU10 temperature | CPU10 usage | CPU10 clock |

| GPU1 core clock | CPU11 temperature | CPU11 usage | CPU11 clock |

| GPU2 core clock | CPU12 temperature | CPU12 usage | CPU12 clock |

| GPU1 memory clock | CPU temperature | CPU usage | CPU clock |

| GPU2 power | CPU power | RAM usage | Commit charge |

| GPU1 voltage limit | GPU1 no load limit |

| Parameter | Unit | Min | Max | Parameter | Unit | Min | Max | Parameter | Unit | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CPU1 temperature | C | 10 | 100 | CPU1 usage | % | 10 | 100 | CPU1 clock | MHz | 10 | 5000 |

| CPU2 temperature | C | 10 | 100 | CPU2 usage | % | 10 | 100 | CPU2 clock | MHz | 10 | 5000 |

| CPU3 temperature | C | 10 | 100 | CPU3 usage | % | 10 | 100 | CPU3 clock | MHz | 10 | 5000 |

| CPU4 temperature | C | 10 | 100 | CPU4 usage | % | 10 | 100 | CPU4 clock | MHz | 10 | 5000 |

| CPU5 temperature | C | 10 | 100 | CPU5 usage | % | 10 | 100 | CPU5 clock | MHz | 10 | 5000 |

| CPU6 temperature | C | 10 | 100 | CPU6 usage | % | 10 | 100 | CPU6 clock | MHz | 10 | 5000 |

| CPU7 temperature | C | 10 | 100 | CPU7 usage | % | 10 | 100 | CPU7 clock | MHz | 10 | 5000 |

| CPU8 temperature | C | 10 | 100 | CPU8 usage | % | 10 | 100 | CPU8 clock | MHz | 10 | 5000 |

| CPU9 temperature | C | 10 | 100 | CPU9 usage | % | 10 | 100 | CPU9 clock | MHz | 10 | 5000 |

| CPU10 temperature | C | 10 | 100 | CPU10 usage | % | 10 | 100 | CPU10 clock | MHz | 10 | 5000 |

| CPU11 temperature | C | 10 | 100 | CPU11 usage | % | 10 | 100 | CPU11 clock | MHz | 10 | 5000 |

| CPU12 temperature | C | 10 | 100 | CPU12 usage | % | 10 | 100 | CPU12 clock | MHz | 10 | 5000 |

| CPU temperature | C | 10 | 100 | CPU usage | % | 10 | 100 | CPU clock | MHz | 10 | 5000 |

| Core No. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 |

| RMSE | 3.356 | 2.414 | 2.736 | 2.756 | 2.742 | 2.780 | 2.082 | 2.069 | 1.651 | 1.656 | 2.557 | 2.488 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ladge, L.; Rao, Y.S. Analysis of Core Temperature Dynamics in Multi-Core Processors. J. Low Power Electron. Appl. 2025, 15, 68. https://doi.org/10.3390/jlpea15040068

Ladge L, Rao YS. Analysis of Core Temperature Dynamics in Multi-Core Processors. Journal of Low Power Electronics and Applications. 2025; 15(4):68. https://doi.org/10.3390/jlpea15040068

Chicago/Turabian StyleLadge, Leena, and Y. Srinivasa Rao. 2025. "Analysis of Core Temperature Dynamics in Multi-Core Processors" Journal of Low Power Electronics and Applications 15, no. 4: 68. https://doi.org/10.3390/jlpea15040068

APA StyleLadge, L., & Rao, Y. S. (2025). Analysis of Core Temperature Dynamics in Multi-Core Processors. Journal of Low Power Electronics and Applications, 15(4), 68. https://doi.org/10.3390/jlpea15040068