Country-Level Vulnerability in Maritime Bulk Commodity Supply Chains: An Integrated Framework for Identification, Monitoring, and Extrapolation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Risk Factor Identification in Maritime Supply Chains

2.2. Vulnerability Assessment of Maritime Supply Chains

3. Methods

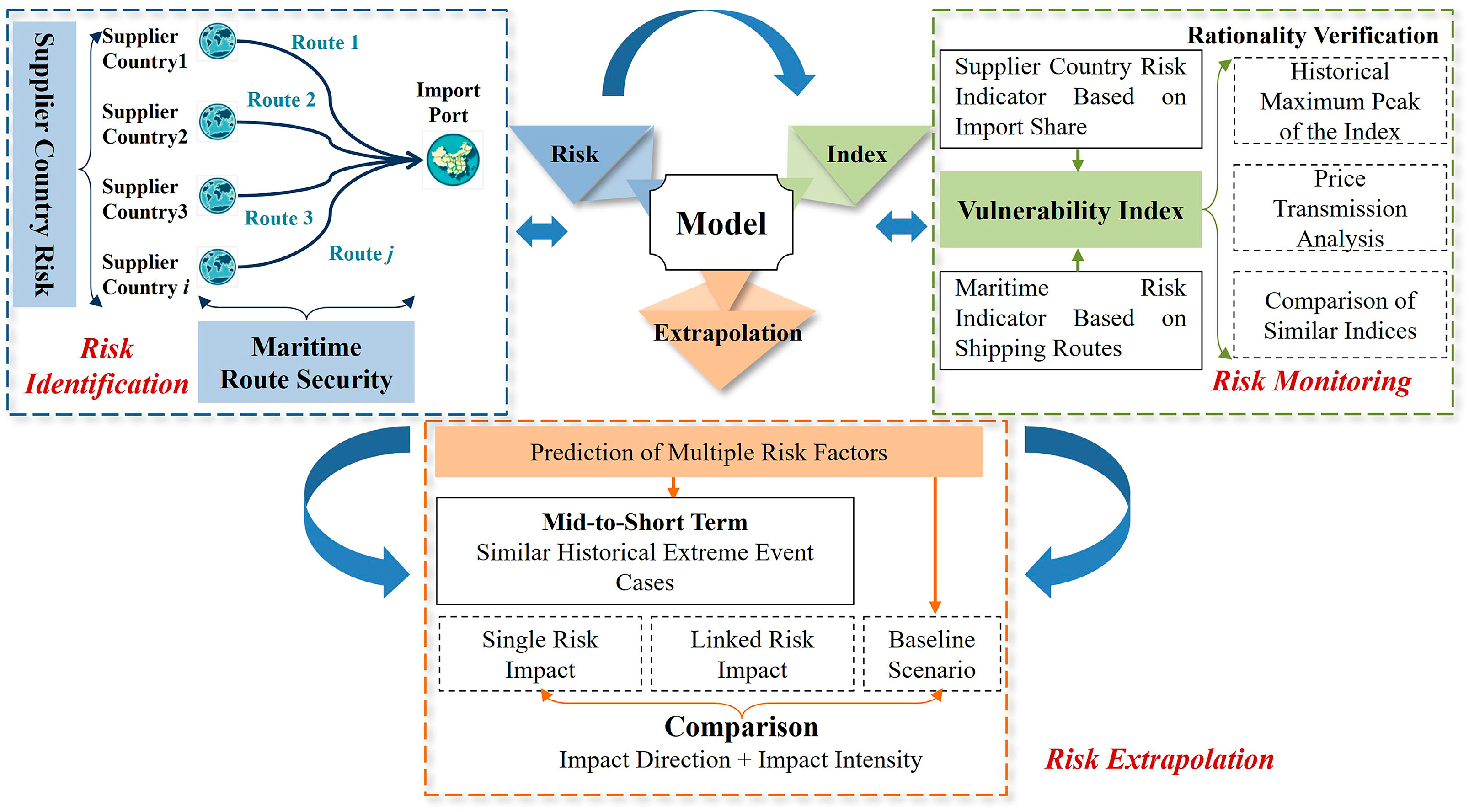

3.1. Fundamental Structure of the RIME Framework

3.2. Risk Identification

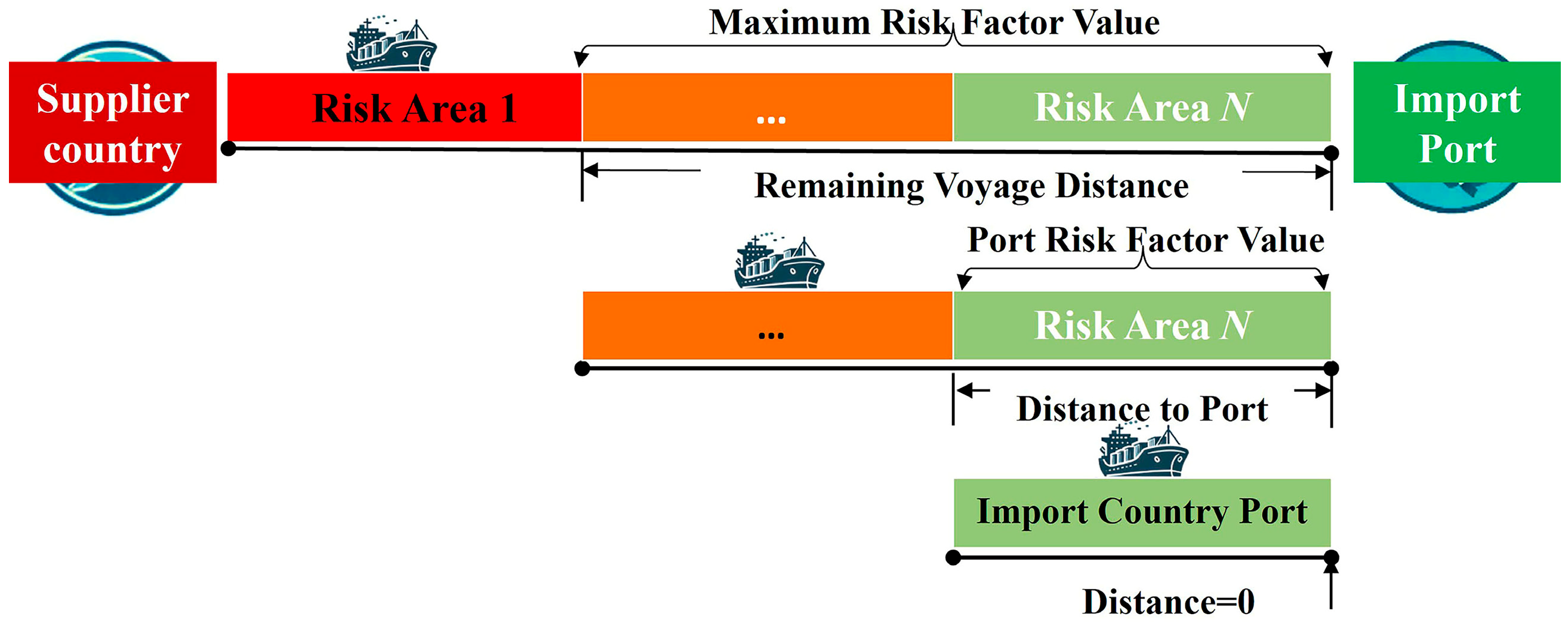

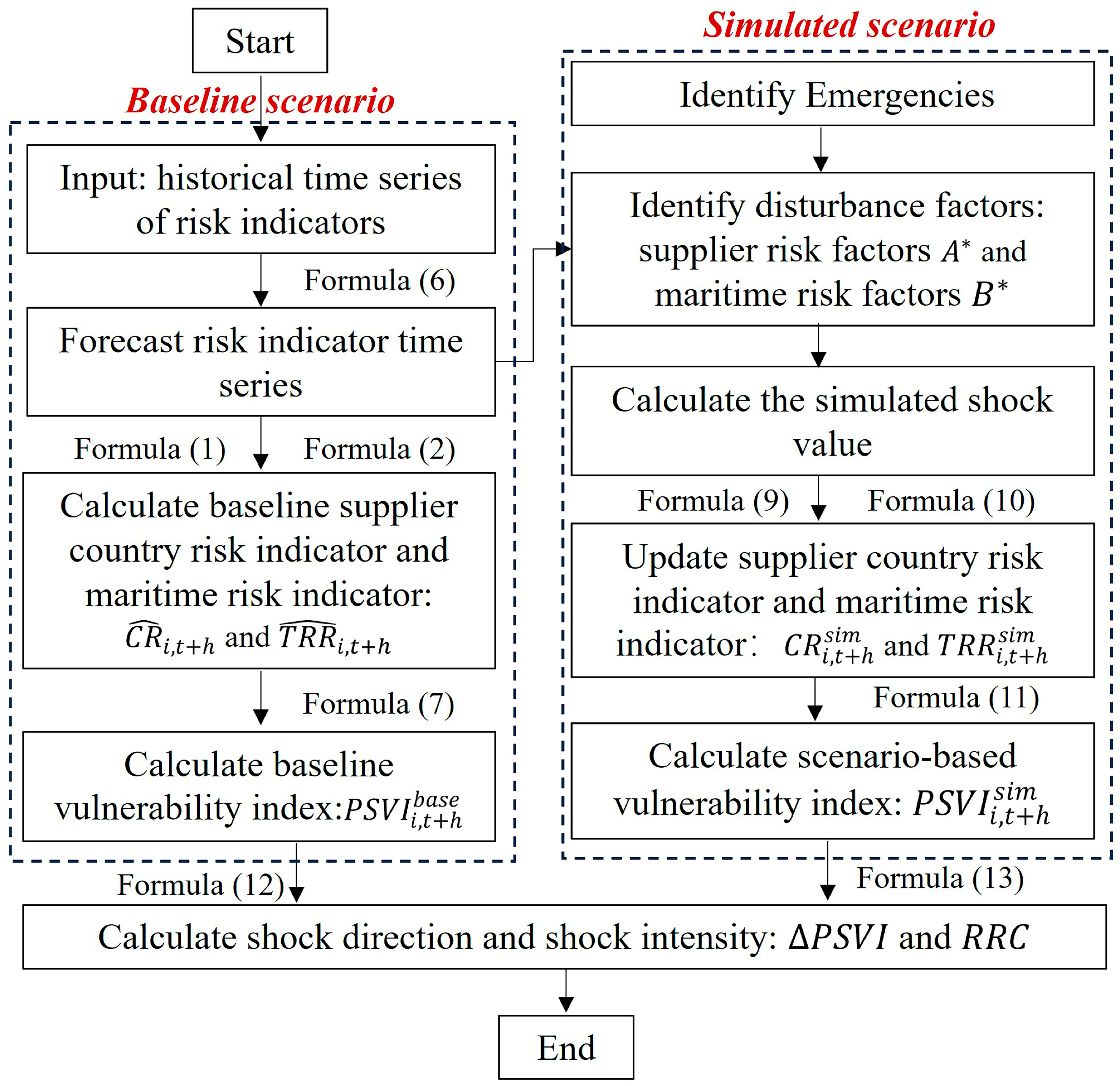

3.3. Risk Monitoring

3.4. Risk Extrapolation

3.5. Methodological Advantages and Framework Applicability

4. A Case Study of China’s Maritime Iron Ore Import Supply Chain

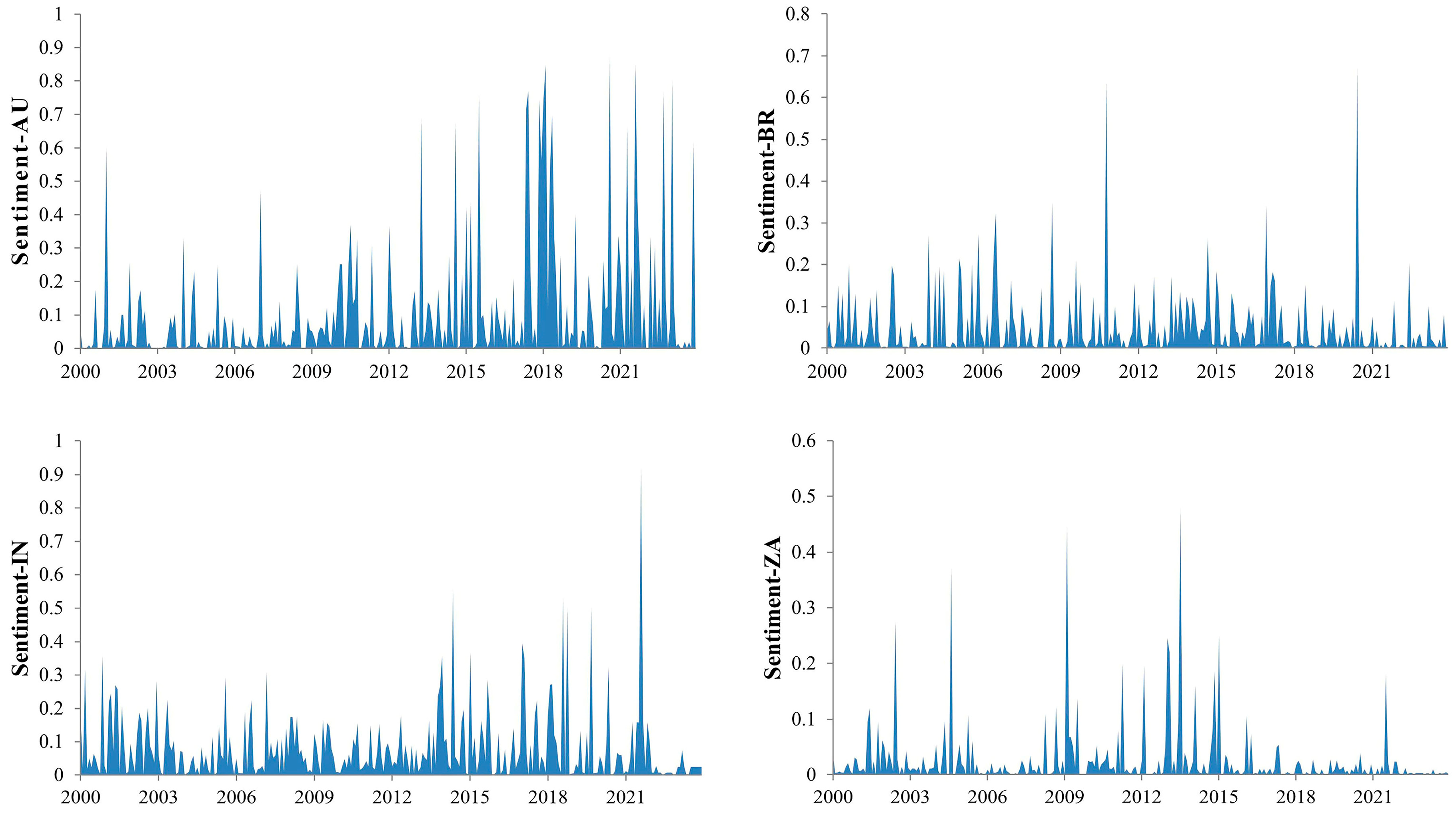

4.1. Data

4.1.1. Data Sources

4.1.2. Data Preprocessing and Standardization

4.2. Construction of the Vulnerability Index

4.2.1. PSVI

4.2.2. Analysis of Largest Spikes

4.2.3. Analysis of the Index–Price Linkage

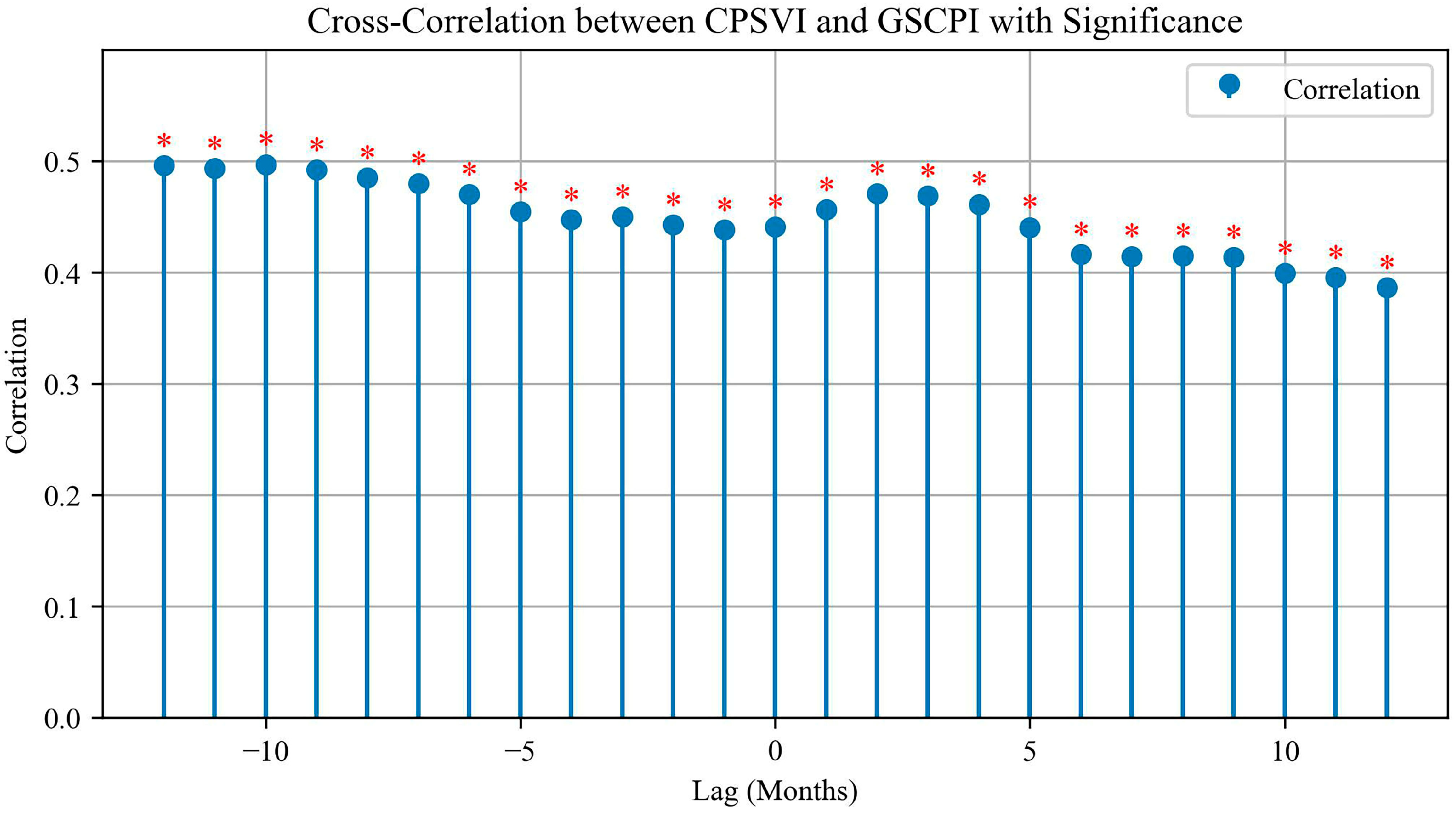

4.2.4. Comparison with the Global Supply Chain Pressure Index

4.2.5. Robustness Tests

- the historical peaks successfully capture all major supply chain shocks, including the COVID-19 pandemic and the Brazil tailings dam collapse, with event rankings highly consistent with the benchmark results (see Table A1);

- the impulse response of China’s iron ore import price (P) to the new index remains significantly positive and the lead–lag relationship is unchanged (see Figure A1);

- the association with the Global Supply Chain Pressure Index (GSCPI) remains statistically significant.

- the revised index effectively identifies the most important historical shocks, including the COVID-19 pandemic and the Brazil tailings dam collapse, and their rankings are consistent with the baseline results; however, the “China–U.S. trade friction”, ranked fifth in the baseline analysis, is not flagged by the entropy-weighted index as among the most prominent shocks, reflecting subtle differences in emphasis on the underlying risk structure induced by different weighting logics (see Table A2).

- In terms of the price–quantity linkage, the new index continues to exert a significantly positive effect on the iron ore price (P), and the core transmission mechanism remains unchanged (see Figure A3).

- Regarding the relationship with the GSCPI, the correlation coefficient declines relative to the baseline result, but statistical significance remains (see Figure A4).

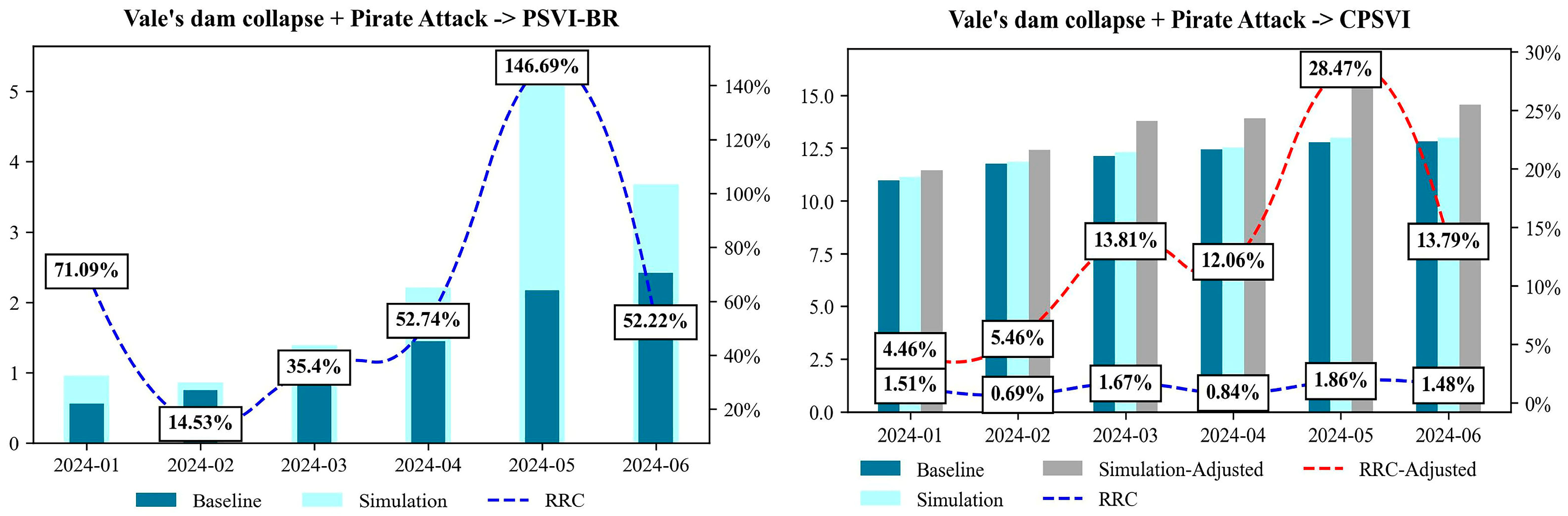

4.3. Risk Extrapolation Results

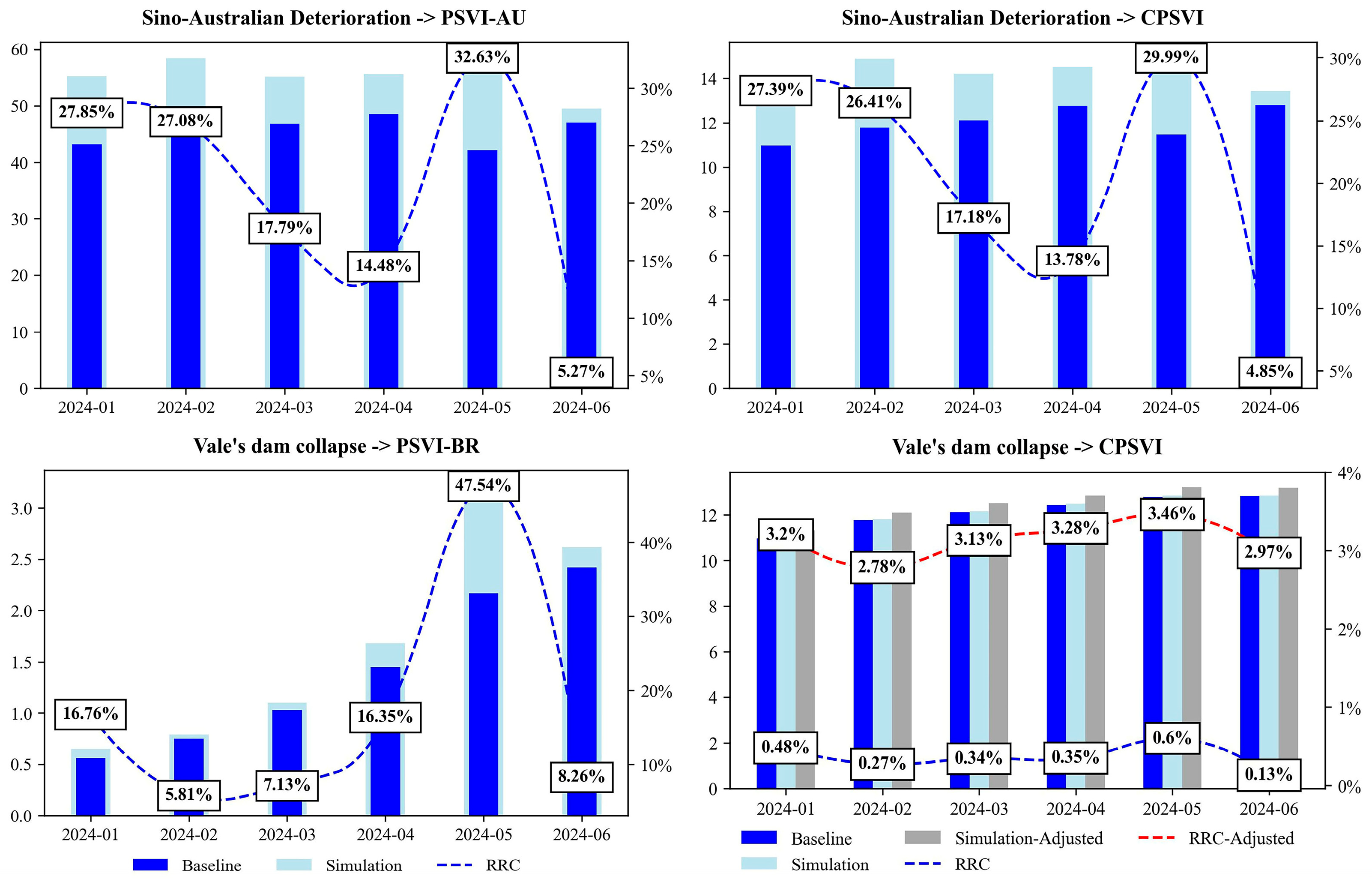

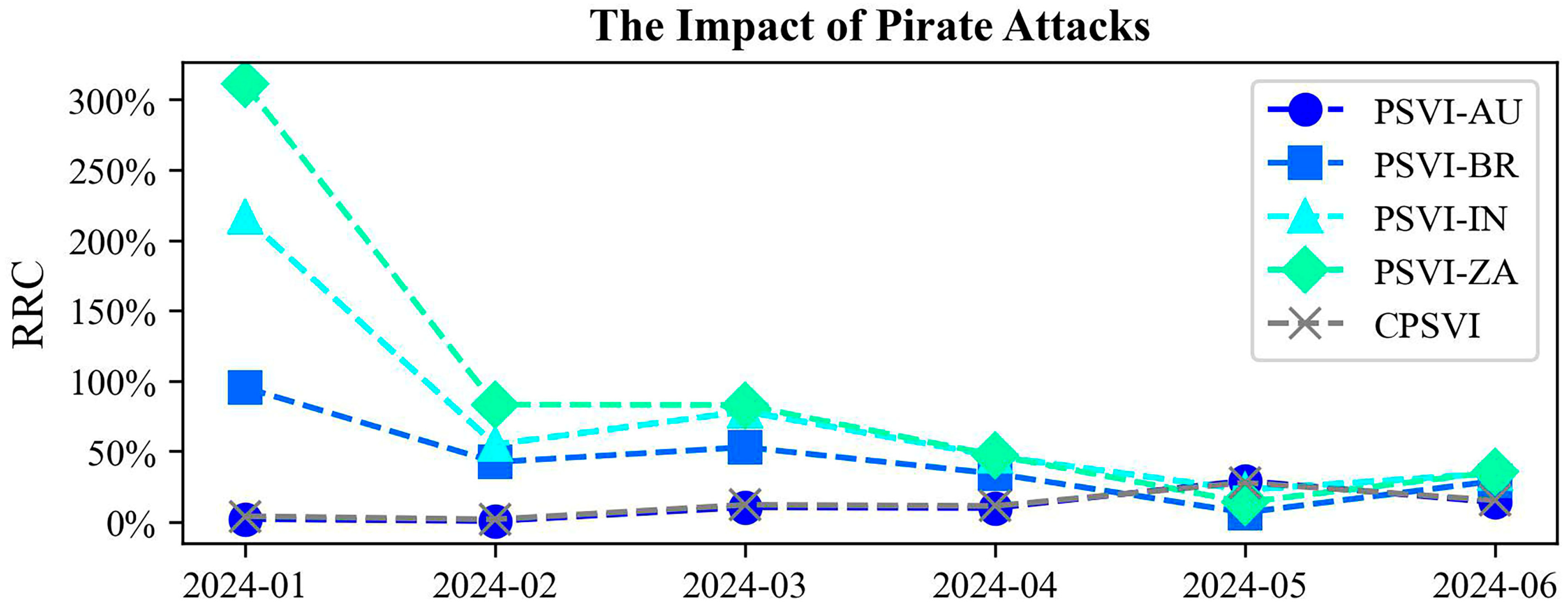

4.3.1. Single Event Shocks

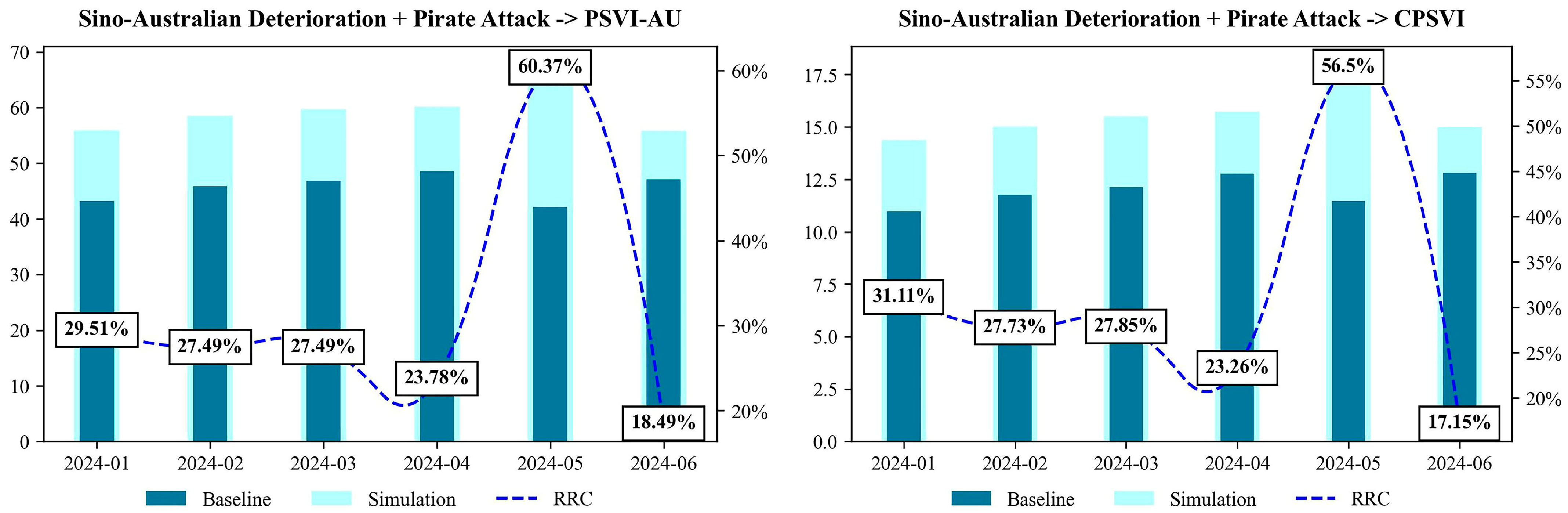

4.3.2. Combined Event Shocks

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix A.1

| Month | Rank | CPSVI | Shock | Event |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| January 2015 | 12 | 16.63 | 6.61 | Completion of Australia’s expansion plan |

| July 2015 | 15 | 16.89 | 6.05 | |

| December 2015 | 4 | 21.20 | 8.68 | |

| February 2016 | 9 | 6.55 | 7.34 | Capacity reduction and environmental production restrictions |

| November 2016 | 2 | 10.62 | 9.60 | |

| July 2017 | 7 | 11.02 | 8.05 | |

| April 2018 | 10 | 24.22 | 7.12 | Sino–U.S. trade friction |

| January 2019 | 6 | 20.21 | 8.22 | Vale dam collapse in Brazil |

| May 2019 | 11 | 23.32 | 7.02 | |

| October 2019 | 13 | 20.04 | 6.43 | |

| December 2019 | 8 | 23.89 | 8.02 | |

| March 2020 | 1 | 21.94 | 10.11 | Outbreak of the COVID-19 pan-demic |

| October 2020 | 5 | 11.70 | 8.68 | |

| March 2021 | 3 | 20.53 | 9.21 | |

| January 2022 | 14 | 18.13 | 6.19 |

Appendix A.2

| Month | Rank | CPSVI | Shock | Event |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| December 2015 | 2 | 17.38 | 7.90 | Completion of Australia’s expansion plan |

| February 2016 | 5 | 5.15 | 5.83 | Capacity reduction and environmental production restrictions |

| November 2016 | 3 | 16.55 | 7.78 | |

| December 2016 | 6 | 17.80 | 5.72 | |

| February 2017 | 13 | 9.46 | 4.92 | |

| July 2017 | 12 | 7.40 | 5.07 | |

| January 2019 | 11 | 13.32 | 5.15 | Vale dam collapse in Brazil |

| May 2019 | 15 | 14.91 | 4.88 | |

| December 2019 | 7 | 15.48 | 5.60 | |

| February 2020 | 9 | 19.14 | 5.39 | Outbreak of the COVID-19 pan-demic |

| March 2020 | 1 | 6.69 | 9.99 | |

| October 2020 | 10 | 7.58 | 5.24 | |

| November 2020 | 8 | 16.31 | 5.57 | |

| December 2020 | 14 | 8.78 | 4.90 | |

| March 2021 | 4 | 14.21 | 6.68 |

References

- Clarkson, P.L.C. Clarkson PLC Annual Report 2024; Clarkson PLC: London, UK, 2024; Available online: https://www.clarksons.com/media/iabfo121/clarkson_plc_annual_report_2024.pdf (accessed on 10 December 2025).

- World Economic Forum. Global Risks Report 2023; World Economic Forum: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023; Available online: https://www.weforum.org/publications/global-risks-report-2023/ (accessed on 10 December 2025).

- Li, D.Y.H.; Jiao, J.B.; Wang, S.Y.; Zhou, G.H. Supply chain resilience from the maritime transportation perspective: A bibliometric analysis and research directions. Fundam. Res. 2025, 5, 437–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabalu, H. Vulnerability of natural gas supply in the Asian gas market. Econ. Anal. Policy 2009, 39, 255–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.D.; Lu, J.; Li, J. Investigation of accident severity in sea lanes from an emergency response perspective based on data mining technology. Ocean Eng. 2021, 239, 109920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.G.; Gu, B.M.; Chen, J.H. Enablers for maritime supply chain resilience during pandemic: An integrated MCDM approach. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2023, 175, 103777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, B.M.; Liu, J.G. A systematic review of resilience in the maritime transport. Int. J. Logist. Res. Appl. 2022, 28, 257–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.G.; Wu, J.J.; Gong, Y. Maritime supply chain resilience: From concept to practice. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2023, 182, 109366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarghami, S.A.; Dumrak, J. Unearthing vulnerability of supply provision in logistics networks to the black swan events: Applications of entropy theory and network analysis. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2021, 215, 107798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ducruet, C. The polarization of global container flows by interoceanic canals: Geographic coverage and network vulnerability. Marit. Policy Manag. 2015, 43, 242–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, F.; Chan, H.K.; Pawar, K. The effects of inter- and intraorganizational factors on the adoption of electronic booking systems in the maritime supply chain. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2021, 236, 108119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tatarczak, A. Mapping the landscape of artificial intelligence in supply chain management: A bibliometric analysis. Mod. Manag. Rev. 2024, 29, 43–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Lam, J.S.L. Estimating the economic losses of port disruption due to extreme wind events. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2015, 116, 300–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, J.S.L.; Lassa, J.A. Risk assessment framework for exposure of cargo and ports to natural hazards and climate extremes. Marit. Policy Manag. 2017, 44, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.Y.; Song, D.P. Ocean container transport in global supply chains: Overview and research opportunities. Transp. Res. Part B Methodol. 2017, 95, 442–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, J.S.L.; Su, S.L. Disruption risks and mitigation strategies: An analysis of Asian ports. Marit. Policy Manag. 2015, 42, 415–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verschuur, J.; Koks, E.E.; Hall, J.W. Port disruptions due to natural disasters: Insights into port and logistics resilience. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2020, 85, 102393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verschuur, J.; Koks, E.E.; Hall, J.W. Ports’ criticality in international trade and global supply-chains. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 4351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wendler-Bosco, V.; Nicholson, C. Port disruption impact on the maritime supply chain: A literature review. Sustain. Resilient Infrastruct. 2020, 5, 378–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.H.; Xu, J.J.; Song, D.P. An analysis of safety and security risks in container shipping operations: A case study of Taiwan. Saf. Sci. 2014, 63, 168–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shepard, J.U.; Pratson, L.F. Maritime piracy in the Strait of Hormuz and implications of energy export security. Energy Policy 2020, 140, 111379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, C.; Yang, Z.; Zhang, D.; Yan, X.P.; Fan, S.Q. Resilience in transportation systems: A systematic review and future directions. Transp. Rev. 2018, 38, 479–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, A.; Ng, A.K.Y.; McEvoy, D.; Mullett, J. Implications of climate change for shipping: Ports and supply chains. WIREs Clim. Change 2018, 9, e508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narasimha, P.T.; Jena, P.R.; Majhi, R. Impact of COVID-19 on the Indian seaport transportation and maritime supply chain. Transp. Policy 2021, 110, 191–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Notteboom, T.; Pallis, T.; Rodrigue, J.P. Disruptions and resilience in global container shipping and ports: The COVID-19 pandemic versus the 2008–2009 financial crisis. Marit. Econ. Logist. 2021, 23, 179–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseini, S.; Ivanov, D. A multi-layer Bayesian network method for supply chain disruption modelling in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2022, 60, 5258–5276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, R.; Xiao, T.; Zhao, P.; Zhang, M.; Ma, T.; Qiu, S. Structure and resilience changes of global liquefied natural gas shipping network during the Russia–Ukraine conflict. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2024, 252, 107102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Liu, Y.; Wong, C.W.Y.; Lai, K.-H.; Tu, E. The impacts of geopolitics on global Liquefied Natural Gas (LNG) shipping network: Evidence from two geopolitical events. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2025, 267, 107706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Fu, X.; Wang, K.; Zheng, S.; Xiao, Y. Bibliometric analysis and literature review on maritime transport resilience and its associated impacts on trade. Marit. Policy Manag. 2025, 52, 440–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.L.; Tian, Z.H.; Huang, A.Q.; Yang, Z.L. Analysis of vulnerabilities in maritime supply chains. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2018, 169, 475–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, S.; Goerlandt, F. Exploring vulnerability and resilience of shipping for coastal communities during disruptions: Findings from a case study of Vancouver Island in Canada. Int. J. Logist. Manag. 2021, 32, 1434–1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilko, J.; Ritala, P.; Hallikas, J. Risk management abilities in multimodal maritime supply chains: Visibility and control perspectives. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2019, 123, 469–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, M.Z.; Lu, J.; Qu, Z.H.; Yang, Z.L. Port vulnerability assessment from a supply chain perspective. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2021, 213, 105851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Iulia, M.; Majumdar, A.; Feng, Y.; Xin, X.; Wang, X. Investigation of the risk influential factors of maritime accidents: A novel topology and robustness analytical framework. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2025, 254, 110636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, Q.; Zhen, R.; Dong, H.; Wang, S.W.; Fang, Q.L. Identification of key risk ships in risk-based ship complex network. Ocean Eng. 2025, 327, 120969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.X.; Wu, M.; Yuen, K.F. Assessment of port resilience using Bayesian network: A study of strategies to enhance readiness and response capacities. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2023, 237, 109394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mou, N.X.; Sun, S.Y.; Yang, T.F.; Wang, D.P. Assessment of the resilience of a complex network for crude oil transportation on the Maritime Silk Road. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 181311–181325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, T.; Gao, Q.Y.; Chen, Y.W.; Cheong, K.H. Exploring the vulnerability of transportation networks by entropy: A case study of Asia-Europe maritime transportation network. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2022, 226, 108578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, M.; Cai, Y.; Chen, T.; Wang, H.; Meng, Q. Data-driven impact analysis of chokepoint on multi-scale maritime networks: A case study of the Taiwan Strait. Transp. Res. Part E Logist. Transp. Rev. 2025, 200, 104179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, W.; Shi, J.; Pang, C.; Chen, J.; Wan, Z.; Wang, Z. Assessment and optimization of shipping network resilience in the maritime silk road regions. J. Transp. Geogr. 2025, 130, 104454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, P.; Cheng, S.; Chen, J.; Liao, M.; Wu, L.; Liu, X.; Lu, F. A fine-grained perspective on the robustness of global cargo ship transportation networks. J. Geogr. Sci. 2018, 28, 881–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calatayud, A.; Mangan, J.; Palacin, R. Vulnerability of international freight flows to shipping network disruptions: A multiplex network perspective. Transp. Res. Part E Logist. Transp. Rev. 2017, 108, 195–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, D.; Wang, N.; Yu, A.Q.; Wu, N. Vulnerability analysis of global container shipping liner network based on main channel disruption. Marit. Policy Manag. 2019, 46, 394–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.; Ma, X.; Chen, L.; Zhang, R.W.; Zhang, J.Q. A methodology to quantify risk evolution in typhoon-induced maritime accidents based on directed-weighted CN and improved RM. Ocean Eng. 2025, 319, 120303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Peng, P.; Claramunt, C.; Xie, W.; Lu, F. Modeling cascading risk diffusion in global container shipping network under dynamic flow reassignment. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2026, 265, 111530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Zhang, X.; Ge, Y.E. Measuring risk spillover effects on dry bulk shipping market: A value-at-risk approach. Marit. Policy Manag. 2021, 49, 558–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caldara, D.; Iacoviello, M. Measuring geopolitical risk. Am. Econ. Rev. 2022, 112, 1194–1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mora, N. Sovereign credit ratings: Guilty beyond reasonable doubt. J. Bank. Financ. 2006, 30, 2041–2062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, C.L. Business as usual? Economic responses to political tensions. Am. J. Polit. Sci. 2011, 55, 628–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Cheng, L. MAKG: A maritime accident knowledge graph for intelligent accident analysis and management. Ocean Eng. 2024, 312, 119280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, W.; Zheng, T.; Yildiz, H.; Talluri, S. Supply chain risk management: A literature review. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2015, 53, 5031–5069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biresselioglu, M.E.; Demir, M.H.; Kandemir, C. Modeling Turkey future LNG supply security strategy. Energy Policy 2012, 46, 146–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdmann, L.; Graedel, T.E. Criticality of non-fuel minerals: A review of major approaches and analyses. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2011, 45, 7620–7630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.P.; Sun, X.L.; Wang, F.; Wu, D.S. Risk integration and optimization of oil-importing maritime system: A multi-objective programming approach. Ann. Oper. Res. 2015, 234, 57–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unal, E.O.; Kocaman, S.; Gokceoglu, C. Impact assessment of geohazards triggered by 6 February 2023 Kahramanmaras earthquakes (Mw 7.7 and Mw 7.6) on the natural gas pipelines. Eng. Geol. 2024, 334, 107508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, A.G.; Leeds, B.A. Trading for security: Military alliances and economic agreements. J. Peace Res. 2006, 43, 433–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caldara, D.; Iacoviello, M.; Molligo, P. The economic effects of trade policy uncertainty. J. Monet. Econ. 2020, 109, 38–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, F.; Ji, Q.; Liu, B.Y.; Fan, Y. Energy investment risk assessment for nations along China’s Belt & Road Initiative. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 170, 535–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Liu, J.; Zhang, H.; Guo, Y. Sustainable risk analysis of China’s overseas investment in iron ore. Resour. Policy 2020, 68, 101771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolstad, I.; Wiig, A. What determines Chinese outward FDI? J. World Bus. 2012, 47, 26–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhai, Y.; Jiang, S.X. Quantitative analysis of maritime piracy at global and regional scales to improve maritime security. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2024, 248, 106968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.H.; Fang, Q.; Li, C.G.; Xu, X.F.; Mao, Y.F.; Yu, F. Impact of the Russia–Ukraine conflict on the resilience of global shipping supply chains. Reg. Stud. Mar. Sci. 2025, 91, 104502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilko, J.P.P.; Hallikas, J.M. Risk assessment in multimodal supply chains. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2012, 140, 586–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, J.S.L.; Bai, X.W. A quality function deployment approach to improve maritime supply chain resilience. Transp. Res. Part E Logist. Transp. Rev. 2016, 92, 16–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graedel, T.E.; Barr, R.; Chandler, C.; Chase, T. Methodology of metal criticality determination. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2012, 46, 1063–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jażdżewska-Gutta, M.; Borkowski, P. As strong as the weakest link: Transport and supply chain security. Transp. Rev. 2022, 42, 762–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Niu, Z.; Gao, W. The time-varying effects of trade policy uncertainty and geopolitical risks shocks on the commodity market prices: Evidence from the TVP-VAR-SV approach. Resour. Policy 2022, 76, 102600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, C.; Morales-Contreras, M.F.; Langella, I.M.; Alonso-Monge, J. Modeling supply chain disruptions due to geopolitical reasons: A systematic literature review. Transp. Res. Part E Logist. Transp. Rev. 2025, 202, 104290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Conference on Trade and Development. Review of Maritime Transport 2023; UNCTAD: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023; Available online: https://unctad.org/webflyer/review-maritime-transport-2023 (accessed on 10 December 2025).

- Chen, S.; Meng, B.; Qiu, B.C.; Kuang, H.B. Dynamic effects of maritime risk on macroeconomic and global maritime economic activity. Transp. Policy 2025, 167, 246–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sui, C.; Zhao, Y.; Sun, X.Q.; Kuang, H.B. Cross-market impacts of shipping and commodities: Evidence from iron ore and its shipping routes. Syst. Eng. Theory Pract. 2022, 42, 713–723. [Google Scholar]

- Gande, A.; Parsley, D. News spillovers in the sovereign debt market. J. Financ. Econ. 2005, 72, 691–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.X.; Wang, J. A hybrid ECM-SVR model for iron ore price forecasting in China. Syst. Eng. Theory Pract. 2016, 36, 1769–1777. [Google Scholar]

- Secomandi, N. Optimal commodity trading with a capacitated storage asset. Manag. Sci. 2010, 56, 449–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warell, L. The effect of a change in pricing regime on iron ore prices. Resour. Policy 2014, 41, 16–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Federal Reserve Bank of New York. Global Supply Chain Pressure Index; Federal Reserve Bank of New York: New York, NY, USA, 2022; Available online: https://www.newyorkfed.org/research/policy/gscpi (accessed on 10 December 2025).

- Schonlau, M.; Zou, R.Y. The random forest algorithm for statistical learning. Stata J. 2020, 20, 3–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonseca, L.; Domingues, J.P.; Lima, V.; Dima, A.M.; Busu, M. Digital futures, sustainable outcomes: Mapping the impact of digital transformation on EU SDG progress. Sustain. Dev. 2025. epub ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Risk | Driver | Indicator | Indicator Description | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Supplier Country Risk | Geopolitical Risk | Geopolitical Risk Index (GPR) | A monthly index based on the proportion of articles reporting adverse geopolitical events in the supplier country’s major newspapers | [47] |

| Trade Policy Uncertainty Index (TPR) | A monthly index based on the proportion of articles discussing trade policy uncertainty in the supplier country’s major newspapers | [57] | ||

| Sovereign Credit Risk | Sovereign Credit Rating | Sovereign credit ratings and outlooks published by Standard & Poor’s | [48] | |

| Resource Risk | Reserves | Total proven reserves of the commodity in the supplier country | [58] | |

| Reserve-to-Production Ratio | The ratio of proven reserves to annual production | [59] | ||

| Export Share | Ratio of export volume to total production of the commodity | [60] | ||

| Foreign Dependence | Bilateral Trade | Total trade value of the commodity between the supplier and importing countries | [58] | |

| Export Value/GDP | The ratio of the export value from the supplier country to the GDP of the importing country | [59] | ||

| Import Value/GDP | The ratio of the export value from the supplier country to the GDP of the importing country | |||

| Foreign Direct Investment | Direct investment from the supplier country to the importing country | |||

| Diplomatic Risk | Diplomatic Sentiment Index | A monthly index based on the sentiment of headlines from major newspapers in the supplier and importing countries | [56] | |

| Maritime Risk | Maritime Accidents | Number of maritime accidents in key areas along the shipping routes | [50] | |

| Piracy Attacks | Number of piracy attacks in key areas along the shipping routes | [61] | ||

| Terrorist Activities and Armed Conflicts | Whether terrorist activities and armed conflicts occur in key areas along the shipping routes | [62] | ||

| Port | Route | Distance |

|---|---|---|

| Hedland Port, Australia to Qingdao, China (C5) | Hedland Port–Indian Ocean–Lombok Strait–Makassar Strait–Celebes Sea–Sulu Sea–South China Sea–East China Sea–Yellow Sea–Qingdao | 3613.1 nm |

| Tubarao Port, Brazil to Qingdao, China (C3) | Tubarao Port–Atlantic Ocean–Cape of Good Hope–Indian Ocean–Strait of Malacca–South China Sea–East China Sea–Yellow Sea–Qingdao | 11,427.4 nm |

| Paradip Port, India to Huanghua, China | Paradip Port–Bay of Bengal–Myanmar Sea–Strait of Malacca–South China Sea–Taiwan Strait–East China Sea–Yellow Sea–Huanghua Port | 4394.6 nm |

| Saldanha Bay, South Africa to Tianjin, China | Saldanha Bay–Cape of Good Hope–Indian Ocean–Strait of Malacca–South China Sea–East China Sea–Yellow Sea–Tianjin | 8583.2 nm |

| Month | Rank | CPSVI | Shock | Event |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| January 2015 | 5 | 15.78 | 7.01 | Completion of Australia’s expansion plan |

| July 2015 | 13 | 16.46 | 5.84 | |

| December 2015 | 7 | 18.82 | 6.80 | |

| February 2016 | 17 | 7.84 | 5.38 | Capacity reduction and environmental production restrictions |

| November 2016 | 4 | 19.64 | 7.64 | |

| July 2017 | 8 | 11.38 | 6.59 | |

| April 2018 | 16 | 14.99 | 5.67 | Sino–U.S. trade friction |

| January 2019 | 6 | 17.66 | 6.94 | Vale dam collapse in Brazil |

| May 2019 | 11 | 21.12 | 6.07 | |

| July 2019 | 10 | 12.69 | 6.25 | |

| October 2019 | 20 | 17.76 | 5.23 | |

| December 2019 | 9 | 21.20 | 6.46 | |

| March 2020 | 1 | 10.55 | 10.34 | Outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic |

| October 2020 | 2 | 11.81 | 7.80 | |

| March 2021 | 3 | 18.60 | 7.69 | |

| May 2021 | 19 | 10.22 | 5.24 | |

| January 2022 | 12 | 17.24 | 5.93 | |

| February 2022 | 18 | 19.47 | 5.31 | |

| March 2022 | 15 | 22.67 | 5.73 | |

| January 2023 | 14 | 17.58 | 5.77 |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.236 *** (3.60) | 0.213 *** (3.26) | 0.236 *** (3.60) | 0.241 *** (3.66) | |

| 0.220 *** (3.00) | ||||

| −0.186 *** (−2.53) | ||||

| −0.014 (−0.25) | ||||

| 0.115 ** (2.05) | ||||

| 0.091 (1.18) | ||||

| −0.030 (−0.38) | ||||

| CSO | 0.224 ** (2.29) | 0.217 ** (2.22) | 0.196 * (1.97) | 0.202 ** (2.02) |

| BDI | 0.012 (1.19) | 0.001 (0.12) | 0.005 (0.50) | 0.002 (0.22) |

| ER | −1.020 (−1.44) | −1.362 ** (−1.99) | −1.213 * (−1.77) | −1.185 * (−1.71) |

| PPI | −0.003 ** (−1.98) | −0.003 ** (−2.02) | −0.002 (−1.57) | −0.002 (−1.50) |

| 0.152 | 0.154 | 0.119 | 0.114 | |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (1) | (2) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| November 2007–June 2015 | September 2017–December 2023 | |||||

| 0.280 *** (4.29) | 0.273 *** (4.18) | 0.264 *** (4.00) | 0.274 *** (4.20) | 0.329 *** (3.28) | 0.201 * (1.86) | |

| 0.043 (1.34) | 0.138 * (1.73) | |||||

| 0.008 (0.25) | 0.153 ** (2.34) | |||||

| 0.031 (0.93) | −0.007 (−0.22) | |||||

| 0.082 | 0.075 | 0.079 | 0.075 | 0.126 | 0.110 | |

| Hypothesis A: CPSVI Is Not a Granger Cause of GSCPI | Hypothesis B: GSCPI Is Not a Granger Cause of CPSVI | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| F | F | ||

| 0.575 (0.7505) | 3.448 (0.7509) | 2.956 *** (0.0082) | 17.738 *** (0.0069) |

| Historical Event | Time Window | Disturbance Factor | Average Change Rate |

|---|---|---|---|

| Deterioration of Sino–Australia Relations | December 2017–November 2023 | Geopolitical Risk Index | 58% |

| Diplomatic Sentiment Index | 65.03% | ||

| Vale Dam Disaster in Brazil | January 2019–June 2019 | Production to Square Ratio | 21.85% |

| Reserve-to-Extraction Ratio | 22.38% | ||

| Import Proportion | 22.94% | ||

| Pirate Attacks | January 2010–December 2020 | South China Sea Pirate Attacks | 73.02% |

| January 2014–December 2015 | Strait of Malacca Pirate Attacks | 67.17% |

| Historical Event | Representative Event | Time Window | Disturbance Factor | Simulated Shock Change Rate |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Deterioration of Sino–Australia Relations | Australia passing the “Foreign Interference Law” and publicly accusing China of political interference for the first time | June 2018–December 2018 | Geopolitical Risk Index | [62.83%, 62.37%, 48.50%, 45.81%, 108.55%, 26.97%] |

| Australia pushing for a COVID-19 origin investigation, China launching trade countermeasures (barley, beef, coal, wine) | April 2020–October 2020 | Diplomatic Sentiment Index | [86.68%, 79.32%, 69.46%, 53.87%, 122.44%, 34.22%] | |

| Australia unilaterally tearing up the “Belt and Road” agreement | April 2021–October 2021 | |||

| Vale Dam Disaster in Brazil | January 2019–July 2019 | Production to Square Ratio | [21.85%, 21.85%, 21.85%, 21.85%, 21.85%, 21.85%] | |

| Reserve-to-Extraction Ratio | [22.38%, 22.38%, 22.38%, 22.38%, 22.38%, 22.38%] | |||

| Import Proportion | [29.94%, 4.54%, 5.46%, −28.51%, −51.48%, 5.81%] | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Guo, L.; Yu, F.; Sui, C.; Yang, M. Country-Level Vulnerability in Maritime Bulk Commodity Supply Chains: An Integrated Framework for Identification, Monitoring, and Extrapolation. Systems 2026, 14, 120. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems14020120

Guo L, Yu F, Sui C, Yang M. Country-Level Vulnerability in Maritime Bulk Commodity Supply Chains: An Integrated Framework for Identification, Monitoring, and Extrapolation. Systems. 2026; 14(2):120. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems14020120

Chicago/Turabian StyleGuo, Lin, Fangping Yu, Cong Sui, and Mo Yang. 2026. "Country-Level Vulnerability in Maritime Bulk Commodity Supply Chains: An Integrated Framework for Identification, Monitoring, and Extrapolation" Systems 14, no. 2: 120. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems14020120

APA StyleGuo, L., Yu, F., Sui, C., & Yang, M. (2026). Country-Level Vulnerability in Maritime Bulk Commodity Supply Chains: An Integrated Framework for Identification, Monitoring, and Extrapolation. Systems, 14(2), 120. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems14020120