Resilience Through Integration: The Synergistic Role of National and Organizational Culture in Enhancing Market Responsiveness

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background and Hypothesis Development

2.1. Market Responsiveness and Supply Chain Resilience

2.2. Information Processing Theory and Supplier Integration (SI)

2.3. Congruence Theory and Cultural Fit

3. Methodology

3.1. Sampling and Data Collection

3.2. Measurement Instruments

| Construct | Measurement Items | Mean | SD | Loading a | t-Value | Cronbach α | CR | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Supplier Integration (SI) | Please indicate the extent of integration or information sharing between your organization and your major supplier in the following areas. (1 = Strongly Disagree, 4= Neutral, 7 = Strongly Agree); Adapted from [101,102] | |||||||

| SI01 | Our level of strategic partnership with our major supplier | 4.70 | 1.45 | 0.742 | 10.592 | 0.912 | 0.913 | |

| SI02 | The participation level of our major supplier in our procurement and production processes | 4.52 | 1.62 | 0.804 | 11.758 | |||

| SI03 | The level of participation by our major supplier in our product design | 4.09 | 1.73 | 0.785 | 11.388 | |||

| SI04 | The extent to which our major supplier shares its inventory availability with us | 4.12 | 1.72 | 0.852 | 12.682 | |||

| SI05 | The extent to which we share our demand forecast with our major supplier | 4.24 | 1.69 | 0.8 | 11.67 | |||

| SI06 | The extent to which we help our major supplier to improve its process to better meet our needs | 4.28 | 1.68 | 0.8 | - | |||

| Organizational culture congruence (OCC) | The following statements are about the relationship between your organization and your major customer. Please indicate the extent to which you agree with each statement. (1 = Strongly Disagree, 4= Neutral, 7 = Strongly Agree); Adapted from [103] | |||||||

| VC01 | Our attachment to our major customer is primarily based on the similarity between its values and ours | 4.44 | 1.38 | 0.727 | 9.561 | 0.870 | 0.873 | |

| VC02 | The reason we prefer our major customer to others is because of what it stands for, its values | 4.31 | 1.33 | 0.878 | 11.544 | |||

| VC03 | During the past year, our company’s values and those of our major customer have become more similar | 4.34 | 1.29 | 0.805 | 10.684 | |||

| VC04 | What our major customer stands for is important to our company | 4.56 | 1.39 | 0.765 | - | |||

| Market Responsiveness | Please indicate the degree to which you agree with the following statements concerning your company’s performance, in comparison to the average of your competitors. (1 = Strongly Disagree, 4= Neutral, 7 = Strongly Agree); Adapted from [12,101,104] | |||||||

| MR01 | Our company can quickly modify products to meet our customers’ requirements | 5.40 | 1.32 | 0.813 | 11.444 | 0.878 | 0.883 | |

| MR02 | Our company can quickly introduce new products into the market | 4.96 | 1.44 | 0.94 | 12.241 | |||

| MR03 | Our company can quickly respond to changes in market demand | 5.09 | 1.29 | 0.777 | - | |||

| Supply Uncertainty | Please indicate your degree of agreement that you have with each statement. (1 = Strongly Agree, 4= Neutral, 7 = Strongly Disagree); Adapted from [105,106] | |||||||

| SU01 | Our suppliers consistently meet our requirements | 4.57 | 1.30 | 0.831 | 7.646 | 0.809 | 0.820 | |

| SU02 | Our suppliers provide us with inputs of consistent quality | 4.54 | 1.40 | 0.896 | 7.61 | |||

| SU03 | We have a low rejection rate for incoming critical materials from our suppliers | 4.76 | 1.22 | 0.58 | - | |||

| Demand Uncertainty | Please indicate your degree of agreement that you have with each statement. (1 = Strongly Disagree, 4= Neutral, 7 = Strongly Agree); Adapted from [105,106] | |||||||

| DU01 | Our demand fluctuates drastically from week to week | 4.29 | 1.51 | 0.829 | 9.379 | 0.828 | 0.830 | |

| DU02 | Customer requirements for our products vary dramatically | 4.45 | 1.36 | 0.789 | 9.238 | |||

| DU03 | Our supply requirements vary drastically from week to week | 4.37 | 1.44 | 0.741 | - | |||

| Technological Uncertainty | Please indicate your degree of agreement that you have with each statement. (1 = Strongly Disagree, 4= Neutral, 7 = Strongly Agree); Adapted from [105,106] | |||||||

| TU01 | Our industry is characterized by rapidly changing technology | 4.35 | 1.54 | 0.764 | 10.05 | 0.842 | 0.842 | |

| TU02 | Our production technology changes frequently | 4.25 | 1.60 | 0.794 | 10.337 | |||

| TU03 | The rate of technology obsolescence in our industry is high | 4.29 | 1.65 | 0.842 | - | |||

| GLOBE Index Dimension | Definition | Mainland China | Hong Kong | Taiwan | U.S. | South Korea |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Future Orientation | The extent to which individuals engage in future-oriented behaviors such as planning, investing in the future, and delaying gratification. | 3.75 | 4.03 | 3.96 | 4.15 | 3.97 |

| Institutional Collectivism | The degree to which organizational and societal institutional practices encourage and reward collective distribution of resources and collective action. | 4.77 | 4.13 | 4.59 | 4.20 | 5.20 |

| Humane Orientation | The degree to which a collective encourages and rewards individuals for being fair, altruistic, generous, caring, and kind to others. | 4.36 | 3.90 | 4.11 | 4.17 | 3.81 |

| Uncertainty Avoidance | The extent to which a society, organization, or group relies on social norms, rules, and procedures to alleviate the unpredictability of future events. | 4.94 | 4.32 | 4.34 | 4.15 | 3.55 |

| Assertiveness | The degree to which individuals are assertive, confrontational, and aggressive in their relationships with others. | 3.76 | 4.67 | 3.92 | 4.55 | 4.40 |

| Power Distance | The degree to which members of a collective expect power to be distributed equally. | 5.04 | 4.96 | 5.18 | 4.88 | 5.61 |

| In-Group Collectivism | The degree to which individuals express pride, loyalty, and cohesiveness in their organizations or families. | 5.80 | 5.32 | 5.59 | 4.25 | 5.54 |

| Performance Orientation | The degree to which a collective encourages and rewards group members for performance improvement and excellence. | 4.45 | 4.80 | 4.56 | 4.49 | 4.55 |

| Gender Egalitarianism | The degree to which a collective minimizes gender inequality. | 3.05 | 3.47 | 3.18 | 3.34 | 2.50 |

3.3. Reliability and Validity

| Mean | SD | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | (9) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) Buyer’s Dependence on its Major Supplier | 46.883 | 22.954 | - | ||||||||

| (2) Relationship Duration | 11.491 | 8.385 | 0.031 | - | |||||||

| (3) Supply Uncertainty | 3.379 | 1.114 | −0.122 | −0.078 | 0.610 a | ||||||

| (4) Technological Uncertainty | 4.319 | 1.454 | 0.118 | −0.139 † | 0.011 | 0.641 a | |||||

| (5) Demand Uncertainty | 4.303 | 1.168 | −0.151 * | −0.036 | 0.037 | 0.536 *** | 0.620 a | ||||

| (6) Supplier Integration (SI) | 4.324 | 1.374 | 0.121 | 0.203 ** | −0.373 *** | −0.068 | 0.009 | 0.637 a | |||

| (7) National Culture Congruence (NCC) | 1.250 | 0.712 | 0.022 | 0.087 | −0.209 ** | −0.158 * | −0.169 * | 0.159 * | - | ||

| (8) Organizational culture congruence (OCC) | 4.413 | 1.143 | 0.208 ** | 0.100 | −0.257 ** | 0.013 | −0.028 | 0.442 *** | 0.156 * | 0.633 a | |

| (9) Market Responsiveness | 5.150 | 1.212 | −0.048 | 0.007 | −0.245 ** | 0.095 | 0.009 | 0.246 ** | −0.116 | 0.183 * | 0.720 a |

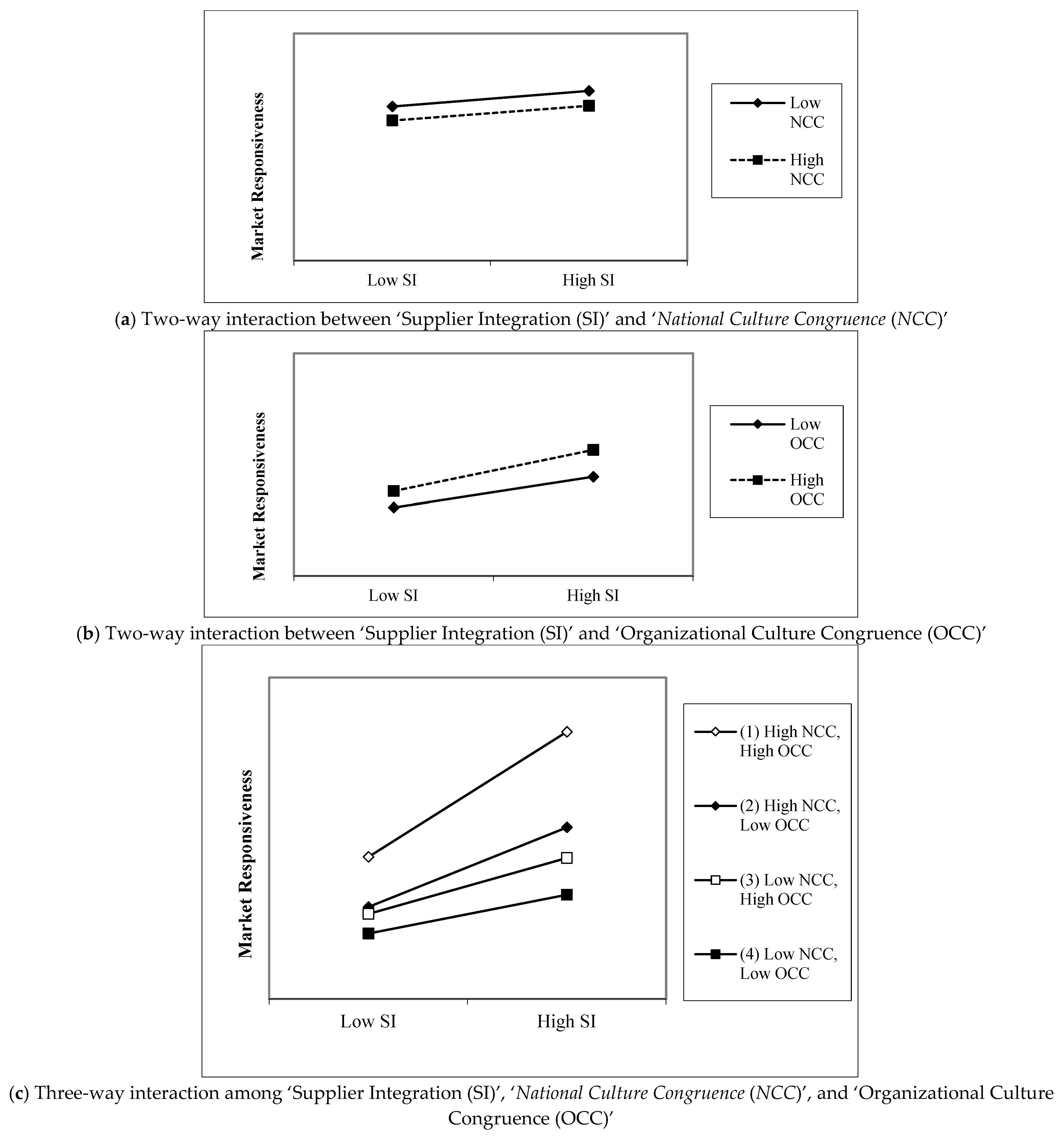

4. Analysis Results

4.1. Hierarchical Regression Analysis

4.2. Ad Hoc Analysis

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Implications

5.2. Managerial Implications

5.3. Limitations & Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dyer, J.H.; Singh, H. The relational view: Cooperative strategy and sources of interorganizational competitive advantage. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1998, 23, 660–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flynn, B.; Huo, B.; Zhao, X. The impact of supply chain integration on performance: A contingency and configuration approach. J. Oper. Manag. 2010, 28, 58–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glaster, S.; Buckley, P.J. An empirical analysis of motives for offshore international production. Manag. Int. Rev. 1996, 36, 75–96. [Google Scholar]

- Inkpen, A.C.; Dinur, A. Knowledge management processes and international joint ventures. Organ. Sci. 1998, 9, 454–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lubatkin, M.; Florin, J.; Lane, P. Learning together and apart: A model of reciprocal interfirm learning. Hum. Relat. 2001, 54, 1353–1382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mowery, D.C.; Oxley, J.E.; Silverman, B.S. Technological overlap and interfirm cooperation: Implications for the resource-based view of the firm. Res. Policy 1998, 27, 507–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. Science, Technology and Industry Outlook 2000; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Sirmon, D.G.; Lane, P.J. A model of cultural differences and international alliance performance. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2004, 35, 306–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, G.; Shang, G. Impact of supply base structural complexity on financial performance: Roles of visible and not-so-visible characteristics. J. Oper. Manag. 2017, 53–56, 23–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Namdar, J.; Pant, G.; Blackhurst, J. Impact of industrial and geographical concentrations of upstream industries on firm performance during COVID-19. Prod. Oper. Manag. 2025; in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Zhou, H.; Zhao, X. The role of supply chain diversification in mitigating the negative effects of supply chain disruptions in COVID-19. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2024, 44, 99–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braunscheidel, M.J.; Suresh, N.C. The organizational antecedents of a firm’s supply chain agility for risk mitigation and response. J. Oper. Manag. 2009, 27, 119–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narayanan, S.; Narasimhan, R.; Schoenherr, T. Assessing the contingent effects of collaboration on agility performance in buyer–supplier relationships. J. Oper. Manag. 2015, 33–34, 140–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, B.D.; Roh, J.; Tokar, T.; Swink, M. Leveraging supply chain visibility for responsiveness: The moderating role of internal integration. J. Oper. Manag. 2013, 31, 543–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huo, B.; Han, Z.; Zhao, X.; Zhou, H.; Wood, C.H.; Zhai, X. The impact of institutional pressures on supplier integration and financial performance: Evidence from China. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2013, 146, 82–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, A.K.W. Influence of contingent factors on the perceived level of supplier integration: A contingency perspective. J. Eng. Technol. Manag. 2014, 33, 210–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danese, P. Supplier integration and company performance: A configurational view. Omega 2013, 41, 1029–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perols, J.; Zimmermann, C.; Kortmann, S. On the relationship between supplier integration and time-to-market. J. Oper. Manag. 2013, 31, 153–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simonin, B. An empirical investigation of the process of knowledge transfer in international strategic alliances. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2004, 35, 407–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, K.L.; Nollen, S.D. Culture and congruence: The fit between management practices and national culture. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 1996, 27, 753–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pothukuchi, V.; Damanpour, F.; Choi, J.; Chen, C.C.; Park, S.H. National and organizational culture differences and international joint venture performance. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2002, 33, 243–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cannon, J.P.; Doney, P.M.; Mullen, M.R.; Petersen, K.J. Building long-term orientation in buyer–supplier relationships: The moderating role of culture. J. Oper. Manag. 2010, 28, 506–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, M.; Gupta, S. Influence of national cultures on operations management and supply chain management practices: A research agenda. Prod. Oper. Manag. 2019, 28, 2681–2698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ralston, P.M.; Blackhurst, J.; Cantor, D.E.; Crum, M.R. A structure–conduct–performance perspective of how strategic supply chain integration affects firm performance. J. Supply Chain Manag. 2015, 51, 47–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, W.; Chavez, R.; Jacobs, M.A.; Wong, C.Y.; Yuan, C. Environmental scanning, supply chain integration, responsiveness, and operational performance: An integrative framework from an organizational information processing theory perspective. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2019, 39, 787–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Z.; Huo, B.; Li, Y.; Zhao, X. The impact of organizational culture on supply chain integration: A contingency and configuration approach. Supply Chain Manag. Int. J. 2015, 20, 24–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durach, C.F.; Wiengarten, F. Supply chain integration and national collectivism. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2020, 224, 107543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Tan, J.; Mao, H.; Gong, Y. Does national culture matter? Understanding the impact of supply chain integration in multiple countries. Supply Chain Manag. Int. J. 2021, 26, 610–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, C.; Sancha, C.; Thomsen, C. A national culture perspective in the efficacy of supply chain integration practices. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2017, 193, 554–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, F.; Matzler, K. Antecedents of M&A success: The role of strategic complementarity, cultural fit, and degree and speed of integration. Strateg. Manag. J. 2014, 35, 269–291. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Z.J.; Anand, J. A multilevel perspective on knowledge transfer: Evidence from the Chinese automotive industry. Strateg. Manag. J. 2009, 30, 959–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaara, E.; Sarala, R.; Stahl, G.K.; Björkman, I. The impact of organizational and national cultural differences on social conflict and knowledge transfer in international acquisitions. J. Manag. Stud. 2012, 49, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, K.; Bhagat, R.S.; Buchan, N.R.; Erez, M.; Gibson, C.B. Culture and international business: Recent advances and their implications for future research. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2005, 36, 357–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aljanabi, A.R.A.; Ghafour, K.M. Supply chain management and market responsiveness: A simulation study. J. Bus. Ind. Mark. 2020, 36, 150–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tukamuhabwa, B.R.; Stevenson, M.; Busby, J.; Bell, M. Supply chain resilience: Definition, review and theoretical foundations for further study. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2015, 53, 5592–5623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamin, B.M. Investigating the drivers of supply chain resilience in the wake of the covid-19 pandemic: Empirical evidence from an emerging economy. Sustainability 2021, 13, 11939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanov, D. Supply chain resilience: Conceptual and formal models drawing from immune system analogy. Omega 2024, 127, 103081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siagian, H.; Tarigan, Z.J.H.; Jie, F. Supply chain integration enables resilience, flexibility, and innovation to improve business performance in covid-19 era. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, J.P.; Barbosa-Póvoa, A.P.F.D. A responsiveness metric for the design and planning of resilient supply chains. Ann. Oper. Res. 2023, 324, 1129–1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spieske, A.; Birkel, H. Improving supply chain resilience through Industry 4.0: A systematic literature review under the impressions of the COVID-19 pandemic. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2021, 158, 107452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, C.; Chen, S.; Huang, C. Investigating the role of supply chain environmental risk in shaping the nexus of supply chain agility, resilience, and performance. Sustainability 2023, 15, 15003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richey, R.G.; Roath, A.S.; Adams, F.G.; Wieland, A. A responsiveness view of logistics and supply chain management. J. Bus. Logist. 2022, 43, 62–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, Y.; Wang, X.; Zhang, M.; Wang, Q. Developing supply chain resilience through integration: An empirical study on an e-commerce platform. J. Oper. Manag. 2022, 69, 477–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aslam, H.; Blome, C.; Roscoe, S.; Azhar, T.M. Dynamic supply chain capabilities: How market sensing, supply-chain agility and adaptability affect supply-chain ambidexterity. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2018, 38, 2266–2285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, H.-L.; Shen, B.; Cai, Y.-J. Quick response strategy with cleaner technology in a supply chain: Coordination and win-win situation analysis. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2018, 56, 3397–3408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munir, M.; Jajja, M.S.S.; Chatha, K.A. Capabilities for enhancing supply chain resilience and responsiveness in the COVID-19 pandemic: Exploring the role of improvisation, anticipation, and data analytics capabilities. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2022, 42, 1576–1604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galbraith, J.R. Organization design: An information processing view. Interfaces 1974, 4, 28–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tushman, M.L.; Nadler, D.A. Information processing as an integrating concept in organizational design. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1978, 3, 613–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, S.; Kim, H.; Hur, D.S.; Schoenherr, T. Interorganizational information processing and the contingency effects of buyer-incurred uncertainty in a supplier’s component development project. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2019, 210, 169–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, C.Y.; Boon-Itt, S.; Wong, C.W.Y. The contingency effects of environmental uncertainty on the relationship between supply chain integration and operational performance. J. Oper. Manag. 2011, 29, 604–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molinaro, M.; Danese, P.; Romano, P.; Swink, M. Implementing supplier integration practices to improve performance: The contingency effects of supply base concentration. J. Bus. Logist. 2022, 43, 540–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, W.; Jacobs, M.A.; Salisbury, W.D.; Enns, H. The effects of supply chain integration on customer satisfaction and financial performance: An organizational learning perspective. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2013, 146, 346–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Cavusgil, E.; Cavusgil, S.T. An investigation of the black-box supplier integration in new product development. J. Bus. Res. 2014, 67, 1058–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvador, F.; Villena, V.H. Supplier integration and NPD outcomes: Conditional moderation effects of modular design competence. J. Supply Chain Manag. 2013, 49, 87–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramirez, M.J.; Roman, I.E.; Ramos, E.; Patrucco, A.S. The value of supply chain integration in the Latin American agri-food industry: Trust, commitment and performance outcomes. Int. J. Logist. Manag. 2020, 32, 281–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cousins, P.D.; Menguc, B. The implications of socialization and integration in supply chain management. J. Oper. Manag. 2006, 24, 604–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amoako-Gyampah, K.; Boakye, K.G.; Famiyeh, S.; Adaku, E. Supplier integration, operational capability and firm performance: An investigation in an emerging economy environment. Prod. Plan. Control 2020, 31, 1128–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, J.R.; Cable, D.M. The value of value congruence. J. Appl. Psychol. 2009, 94, 654–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cable, D.M.; Edwards, J.R. Complementary and supplementary fit: A theoretical and empirical integration. J. Appl. Psychol. 2004, 89, 822–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, M.B.; Echambadi, R.; Cavusgil, S.T.; Aulakh, P.S. The influence of complementarity, compatibility, and relationship capital on alliance performance. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2001, 29, 358–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajaguru, R.; Matanda, M.J. Effects of inter-organizational compatibility on supply chain capabilities: Exploring the mediating role of inter-organizational information systems integration. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2013, 42, 620–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hult, G.T.M.; Ketchen, D.J.; Slater, S.F. Strategic supply chain management: Improving performance through a culture of competitiveness and knowledge development. Strateg. Manag. J. 2007, 28, 1035–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, S.; Singh, H.; Lee, K. Complementarity, status similarity and social capital as drivers of alliance formation. Strateg. Manag. J. 2000, 21, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, T.K.; Teng, B.S. Between trust and control: Developing confidence in partner cooperation in alliances. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1998, 23, 491–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cartwright, S.; Cooper, C.L. The role of culture compatibility in successful organizational marriage. Acad. Manag. Exec. 1993, 7, 57–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giorgi, S.; Maoret, M.; Zajac, E.J. On the relationship between firms and their legal environment: The role of cultural consonance. Organ. Sci. 2019, 30, 803–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribbink, D.; Grimm, C.M. The impact of cultural differences on buyer–supplier negotiations: An experimental study. J. Oper. Manag. 2014, 32, 114–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naor, M.; Linderman, K.; Schroeder, R. The globalization of operations in Eastern and Western countries: Unpacking the relationship between national and organizational culture and its impact on manufacturing performance. J. Oper. Manag. 2010, 28, 194–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schein, E.H. Organizational Culture and Leadership; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Kalliath, T.J.; Bluedorn, A.C.; Strube, M.J. A test of value congruence effects. J. Organ. Behav. 1999, 20, 1175–1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meglino, B.M.; Ravlin, E.C.; Adkins, C.L. A work values approach to corporate culture: A field test of the value congruence process and its relationship to individual outcomes. J. Appl. Psychol. 1989, 74, 424–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofstede, G. Culture’s Consequences: International Differences in Work-Related Values; Sage: Beverly Hills, CA, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Hofstede, G. The business of international business is culture. Int. Bus. Rev. 1994, 3, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lane, H.W.; Beamish, P.W. Cross-cultural cooperative behavior in joint ventures in LDCs. Manag. Int. Rev. 1990, 30, 87–102. [Google Scholar]

- Parente, R.C.; Baack, D.W.; Hahn, E.D. The effect of supply chain integration, modular production, and cultural distance on new product development: A dynamic capabilities approach. J. Int. Manag. 2011, 17, 278–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Hain, D.S.; Larimo, J.; Dao, L.T. Cultural differences and synergy realization in cross-border acquisitions: The moderating effect of the acquisition process. Int. Bus. Rev. 2020, 29, 101675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, M.S.; Myers, M.B.; Mentzer, J.T. Does relationship learning lead to relationship value? A cross-national supply chain integration. J. Oper. Manag. 2010, 28, 472–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trompenaars, F.; Hampden-Turner, C. Riding the Waves of Culture: Understanding Diversity in Global Business, 3rd ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Alexander, M.; Korine, H. When you shouldn’t go global. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2008, 86, 70–77. [Google Scholar]

- Buono, A.F.; Bowditch, J.L. The Human Side of Mergers and Acquisitions: Managing Collisions between People, Cultures, and Organizations; Beard Books: Washington, DC, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Son, B.-G.; Kim, H.; Hur, D.; Subramanian, N. The Dark Side of Supply Chain Digitalisation: Supplier-Perceived Digital Capability Asymmetry, Buyer Opportunism and Governance. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2021, 41, 1220–1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, J.; In, J. Supplier involvement and supplier performance in new product development: Moderating effects of supplier salesperson behaviors. J. Bus. Res. 2023, 161, 113816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, L.J.; Hartman, N.; Cavazotte, F. Method variance and marker variables: A review and comprehensive CFA marker technique. Organ. Res. Methods 2010, 13, 477–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malhotra, N.K.; Kim, S.S.; Patil, A. Common Method Variance in IS Research: A Comparison of Alternative Approaches and a Reanalysis of Past Research. Manag. Sci. 2006, 52, 1865–1883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, R.B. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling, 4th ed.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Bentler, P.M.; Bonett, D.G. Significance Tests and Goodness of Fit in the Analysis of Covariance Structures. Psychol. Bull. 1980, 88, 588–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Browne, M.W.; Cudeck, R. Alternative Ways of Assessing Model Fit. Sociol. Methods Res. 1992, 21, 230–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, S.H.; Bilsky, W. Toward a universal psychological structure of human values. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1987, 53, 550–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trompenaars, F. Riding the Waves of Culture: Understanding Cultural Diversity in Business; Nicholas Brealey: London, UK, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- House, R.J.; Hanges, P.J.; Javidan, M.; Dorfman, P.W.; Gupta, V. (Eds.) Culture, Leadership, and Organizations: The GLOBE Study of 62 Societies; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Reus, T.H.; Lamont, B.T. The double-edged sword of cultural distance in international acquisitions. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2009, 40, 1298–1316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kogut, B.; Singh, H. The effect of national culture on the choice of entry mode. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 1988, 19, 411–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skinner, S.J.; Gassenheimer, J.B.; Kelley, S.W. Cooperation in supplier–dealer relations. J. Retail. 1992, 68, 174–193. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, E.; Weitz, B. Determinants of continuity in conventional industrial channel dyads. Mark. Sci. 1989, 8, 310–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carey, S.; Lawson, B.; Krause, D.R. Social capital configuration, legal bonds and performance in buyer–supplier relationships. J. Oper. Manag. 2011, 29, 277–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frazier, G.L.; Rody, R.C. The use of influence strategies in interfirm relationships in industrial product channels. J. Mark. 1991, 55, 52–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yli-Renko, H.; Autio, E.; Sapienza, H.J. Social capital, knowledge acquisition, and knowledge exploitation in young technology-based firms. Strateg. Manag. J. 2001, 22, 587–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villena, V.H.; Revilla, E.; Choi, T.Y. The dark side of buyer–supplier relationships: A social capital perspective. J. Oper. Manag. 2011, 29, 561–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; Pei, X. Integrating supplier innovation in the fuzzy front end: Based on an analysis of the task environment. J. Bus. Ind. Mark. 2022, 37, 2417–2431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, M.; Yen, G.; Liu, T. Reexamining supply chain integration and the supplier’s performance relationships under uncertainty. Supply Chain Manag. Int. J. 2014, 19, 64–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frohlich, M.T.; Westbrook, R. Arcs of integration: An international study of supply chain strategies. J. Oper. Manag. 2001, 19, 185–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narasimhan, R.; Kim, S.W. Effect of supply chain integration on the relationship between diversification and performance: Evidence from Japanese and Korean firms. J. Oper. Manag. 2002, 20, 303–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, J.R.; Lusch, R.F.; Nicholson, C.Y. Power and relationship commitment: Their impact on marketing channel member performance. J. Retail. 1995, 71, 363–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swafford, P.M.; Ghosh, S.; Murthy, N. The antecedents of supply chain agility of a firm: Scale development and model testing. J. Oper. Manag. 2006, 24, 170–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, Y.; Zhao, X.; Sheu, C. The impact of competitive strategy and supply chain strategy on business performance: The role of environmental uncertainty. Decis. Sci. 2011, 42, 371–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, I.J.; Paulraj, A. Towards a theory of supply chain management: The constructs and measurements. J. Oper. Manag. 2004, 22, 119–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neter, J.; Wasserman, W.; Kutner, M.H. Applied Regression Models; Irwin: Homewood, IL, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Brouthers, K.D.; Brouthers, L.E. Explaining the National Cultural Distance Paradox. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2001, 32, 177–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, D.; Hasse, V.C.; Schotter, A.P.J. Multinational Enterprises Within Cultural Space and Place: Integrating Cultural Distance and Tightness–Looseness. Acad. Manag. J. 2017, 60, 904–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Mainland China | Hong Kong | Taiwan | U.S. | South Korea | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Number of questionnaires sent | 2878 | 2056 | 2000 | 2500 | 1278 | 10,712 |

| 2. Number of valid responses | 410 | 202 | 212 | 202 | 204 | 1230 |

| 3. Response rate | 14.25% | 9.82% | 10.60% | 8.08% | 15.96% | 11.48% |

| 4. Number of the companies whose main suppliers are foreign company | 0 | 108 | 13 | 35 | 30 | 186 |

| 5. The total number of firms after excluding samples with unspecified overseas supplier countries. | 0 | 106 | 12 | 32 | 24 | 174 |

| 6. Ratio from entire responses | 0.00% | 53.47% | 6.13% | 17.33% | 14.71% | 15.12% |

| Buyer’s dependence on its major supplier | Frequency (%) |

| <20% | 26 (15.2) |

| 21% to <40% | 64 (37.4) |

| 41% to <60% | 39 (22.8) |

| 61% to <80% | 34 (19.9) |

| 81% to <100% | 8 (4.7) |

| Total | 171 (100) |

| Relationship duration with the major supplier | |

| <5 years | 39 (22.4) |

| 6 years to <10 years | 71 (40.8) |

| 11 years to <15 years | 29 (16.7) |

| 16 years to <20 years | 24 (13.8) |

| 21 years to <25 years | 5 (2.9) |

| 26 years to <30 years | 2 (1.1) |

| More than 31 years | 4 (2.3) |

| Total | 174 (100) |

| Number of employees | |

| <50 | 33 (19.0) |

| 51 to <99 | 34 (19.5) |

| 100 to <199 | 48 (27.6) |

| 200 to <499 | 28 (16.1) |

| 500 to <999 | 16 (9.2) |

| 1000 to <4999 | 6 (3.4) |

| More than 5000 | 9 (5.2) |

| Total | 174 (100) |

| Buyer’s industry | |

| Arts & crafts | 1 (0.6) |

| Building materials | 2 (1.2) |

| Chemicals & petrochemicals | 6 (3.5) |

| Electronics & electrical | 35 (20.2) |

| Food, beverage, alcohol, & cigarettes | 3 (1.7) |

| Jewelry | 2 (1.2) |

| Metal, mechanical, & engineering | 26 (15.0) |

| Pharmaceutical & medicals | 4 (2.3) |

| Publishing & printing | 2 (1.2) |

| Rubber & plastics | 11 (6.4) |

| Textiles & apparel | 54 (31.2) |

| Toys | 4 (2.3) |

| Wood & furniture | 3 (1.7) |

| Others | 20 (11.6) |

| Total | 173 (100) |

| Dependent Variable: Buyer’s Market Responsiveness | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | ||

| Industry Dummy (Base: Electronics) | ||||||

| Arts & crafts | 1.643 | 1.924 | 1.713 | 1.713 | 1.527 | |

| Building materials | 0.916 | 1.010 | 1.044 | 1.066 | 0.795 | |

| Chemicals & petrochemicals | −0.094 | −0.136 | −0.086 | −0.055 | −0.097 | |

| Food, beverage, alcohol, & cigarettes | −0.291 | −0.075 | −0.186 | −0.295 | −0.440 | |

| Jewelry | 0.509 | 0.330 | 0.107 | 0.083 | 0.118 | |

| Metal, mechanical, & engineering | −0.130 | 0.006 | −0.185 | −0.217 | −0.225 | |

| Pharmaceutical & medicals | −1.698 ** | −1.772 ** | −1.908 ** | −1.961 ** | −1.991 ** | |

| Publishing & printing | −1.559 † | −2.093 * | −2.271 ** | −2.471 ** | −2.512 ** | |

| Rubber & plastics | −0.368 | −0.361 | −0.468 | −0.462 | −0.500 | |

| Textiles | 0.209 | 0.354 | 0.181 | 0.180 | 0.105 | |

| Toys | −0.230 | −0.126 | −0.297 | −0.396 | −0.389 | |

| Wood & furniture | 1.165 | 1.334 † | 1.486 * | 1.451 * | 1.408 * | |

| Others | −0.001 | 0.036 | −0.104 | −0.122 | −0.183 | |

| Firm-level Control Variables | ||||||

| Firm size | −0.012 | −0.031 | −0.014 | −0.013 | −0.014 | |

| Buyer’s dependence | −0.004 | −0.005 | −0.006 | −0.007 | −0.006 | |

| Relationship duration | 0.008 | 0.002 | 0.003 | 0.000 | 0.003 | |

| Supply uncertainty | −0.232 ** | −0.111 | −0.131 | −0.130 | −0.148 † | |

| Demand uncertainty | −0.088 | −0.122 | −0.146 | −0.165 † | −0.184 † | |

| Technological uncertainty | 0.122 | 0.142 † | 0.131 † | 0.136 † | 0.144 † | |

| Independent Variable & Moderators | ||||||

| Supplier integration (SI) | 0.267 *** | 0.234 ** | 0.258 ** | 0.223 ** | ||

| National Culture Congruence (NCC) | −0.365 ** | −0.397 ** | −0.530 *** | |||

| Organizational Culture Congruence (OCC) | 0.120 | 0.104 | 0.023 | |||

| 2-Way Interaction | ||||||

| SI * NCC | −0.011 | 0.003 | ||||

| SI *OCC | 0.075 | 0.045 | ||||

| 3-Way Interaction | ||||||

| SI * NCC * OCC | 0.138 * | |||||

| R-square | 0.194 | 0.262 | 0.304 | 0.314 | 0.337 | |

| Adjusted R-square | 0.091 | 0.163 | 0.200 | 0.200 | 0.222 | |

| F-value | 1.894 ** | 2.651 *** | 2.917 *** | 2.764 *** | 2.933 *** | |

| Change in R-square | 0.053 * | 0.069 *** | 0.041 * | 0.010 | 0.023 * | |

| Change in F | 3.297 | 13.930 | 4.369 | 1.062 | 5.098 | |

| NCC (Mean-Centered) | OCC (Mean-Centered) | Effect (β) | SE | t | p-Value | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low (−0.378) | Low (−1.18) | 0.241 | 0.096 | 2.51 | 0.013 | [0.052, 0.430] |

| Low (−0.378) | Mid (−0.18) | 0.158 | 0.082 | 1.92 | 0.057 | [−0.005, 0.320] |

| Low (−0.378) | High (0.57) | 0.096 | 0.101 | 0.94 | 0.346 | [−0.104, 0.295] |

| High (0.928) | Low (−1.18) | 0.121 | 0.143 | 0.85 | 0.399 | [−0.161, 0.402] |

| High (0.928) | Mid (−0.18) | 0.214 | 0.112 | 1.9 | 0.059 | [−0.008, 0.435] |

| High (0.928) | High (0.57) | 0.283 | 0.121 | 2.33 | 0.021 | [0.043, 0.523] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kim, H.; Hur, D.; Oh, J. Resilience Through Integration: The Synergistic Role of National and Organizational Culture in Enhancing Market Responsiveness. Systems 2025, 13, 772. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems13090772

Kim H, Hur D, Oh J. Resilience Through Integration: The Synergistic Role of National and Organizational Culture in Enhancing Market Responsiveness. Systems. 2025; 13(9):772. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems13090772

Chicago/Turabian StyleKim, Hyojin, Daesik Hur, and Jaeyoung Oh. 2025. "Resilience Through Integration: The Synergistic Role of National and Organizational Culture in Enhancing Market Responsiveness" Systems 13, no. 9: 772. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems13090772

APA StyleKim, H., Hur, D., & Oh, J. (2025). Resilience Through Integration: The Synergistic Role of National and Organizational Culture in Enhancing Market Responsiveness. Systems, 13(9), 772. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems13090772