Defining Nanostores: Cybernetic Insights on Independent Grocery Micro-Retailers’ Identity and Transformations

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

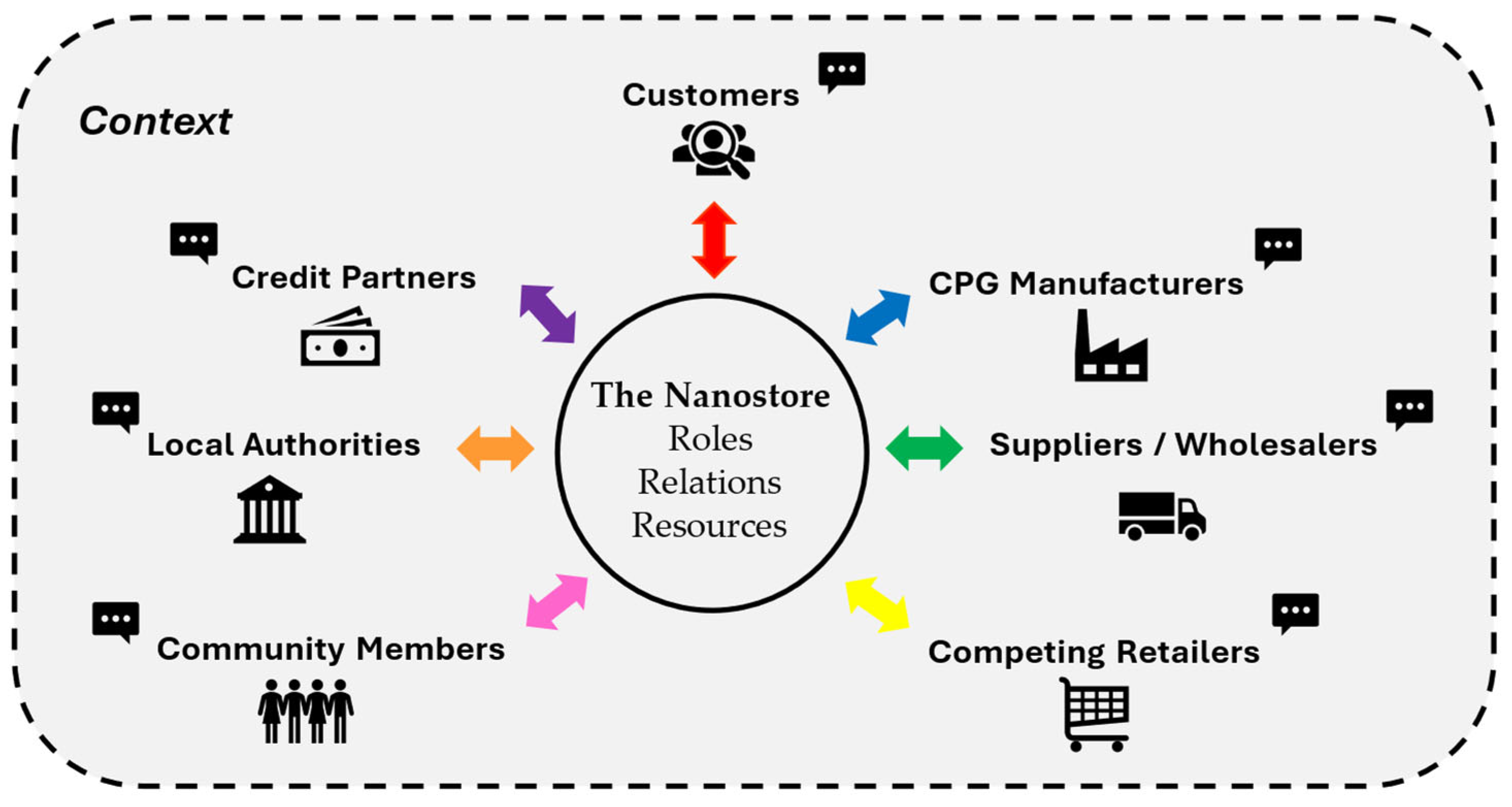

2.1. Nanostores as Purposeful Systems

2.2. Describing Nanostores as Purposeful Systems

- Actors and roles: shopkeepers, family workers, end consumers, suppliers, local authorities, community members.

- Purposes and expectations: income and revenue generation, convenient access to goods, social interaction, community contribution, and business continuity.

- Social processes: rule formation, informal practices (e.g., offering informal credit), relational trust, conflict negotiation, and identity construction.

- Resource configurations: physical assets (e.g., space and shelves), technological elements (e.g., point-of-sale systems, mobile payments, and other devices), and intangible assets (e.g., reputation and loyalty).

- Structural patterns: authority relationships, habitual routines, customer relationship dynamics, and roles in shop management and operations.

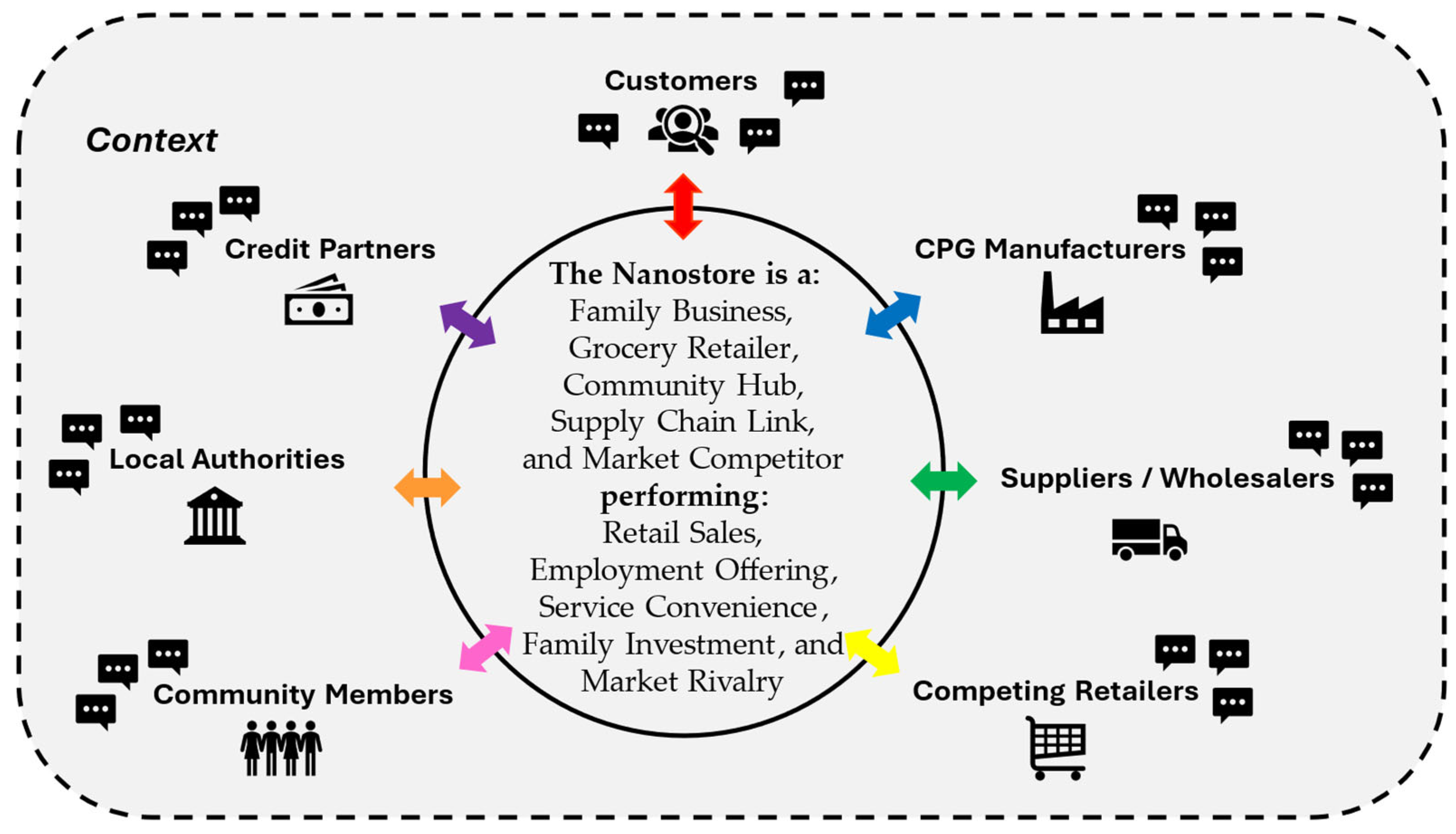

- “What systems do (X)” describes the business identity of nanostores, such as family-run grocery micro-retailers.

- “How they function (Y)” refers to nanostores’ operational dynamics, for example, delivering essential goods through personalised, proximity-based service.

- “Why they matter (Z)” captures the broader impact of nanostores on family livelihood, the provision of daily essentials, and social cohesion in communities.

- Transformation—the core process of converting goods into sales and services.

- Actors—those performing the transformation, such as shopkeepers, employees, and family members.

- Suppliers—entities providing goods, such as CPG manufacturers, grocery wholesalers, or distributors.

- Customers—community members and households who purchase from the nanostore.

- Owners—often, the families who operate and depend on the nanostore.

- Interveners—external influencers, such as competing retailers, regulatory bodies, and contextual constraints.

3. Methodology

3.1. Data Collection

3.2. Data Organisation and Analysis

- i.

- Familiarisation with the data: The survey database was reviewed to ensure consistency and to identify incomplete or incoherent responses.

- ii.

- Generating initial codes: The database was systematically searched to identify coding coincidences between responses and the deductive theory-driven codes defined by each element of the X-Y-Z and the TASCOI framework. Additionally, other relevant descriptions were coded inductively (and extracted) regarding the roles and functions of nanostores, or their challenges and opportunities.

- iii.

- Searching for themes: As the main themes were defined deductively, stakeholders’ descriptions were collated and accommodated according to the X-Y-Z and TASCOI code categories. Inductively identified themes were collated and flagged to further enrich the descriptions of identity.

- iv.

- Reviewing themes: Each X-Y-Z and TASCOI coding category (as themes) was checked for consistency with each stakeholder type because of their diverse perspectives.

- v.

- Defining and naming themes: Descriptions were articulated for each code category, and themes were named accordingly. Descriptive statistical analysis and excerpts were extracted to describe their diversity and highlight stakeholders’ perspectives. Relevant inductively identified descriptions were integrated and combined into the identity statements. Therefore, multiple iterations were conducted by returning to steps 2, 3, and 4.

- vi.

- Producing the report: Descriptions were summarised in tables, exemplifying each case with excerpts, linked to the research questions, and further discussed in light of the literature.

3.3. Results Reporting and Discussion

4. Results

4.1. Identity Statement Descriptions by Stakeholders

4.1.1. Categorisation of “X”—What the Nanostore Does

4.1.2. Categorisation of “Y”—How the Nanostore Functions

4.1.3. Categorisation of “Z”—Purpose of Nanostores (Why It Matters)

4.2. A Systemic View of the Nanostore: Integrating TASCOI with X, Y, Z, and Transformation Variations

4.3. X-Y-Z Identity Descriptions of the Nanostore: Patterns, Alternatives, and Significance

5. Discussion

5.1. Findings

5.1.1. Findings on Identity Statements and the TASCOI Tool

5.1.2. Findings on Nanostore Identity and Transformation

5.2. Implications

5.2.1. Theoretical Implications

5.2.2. Practical Implications

5.3. A Discussion on Validity, Reliability, Transferability, and Generalisability

5.4. Limitations and Future Work

5.4.1. Limitations

5.4.2. Future Research

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| RQ | Research question; |

| X-Y-Z | What they do (X), how they function (Y), and why they matter (Z); |

| TASCOI | Transformation, Actors, Suppliers, Customers, Owners, and Interveners. |

Appendix A. Survey Questionnaire

Appendix A.1

- Identify the type of stakeholder to be interviewed (e.g., actor, supplier, client, owner, or intervener).

- Describe the key characteristics and attributes of the selected stakeholder.

- What is the stakeholder’s specific role within the store?

- In what ways does the stakeholder regularly interact with the nanostore?

- What makes this stakeholder particularly important or relevant to the nanostore’s operations?

- What specific tasks or activities do stakeholders perform in collaboration with the nanostore?

Appendix A.2

- What are the stakeholders’ expectations, needs, requirements, or preferences regarding the nanostore and its operations?

- How does the stakeholder assess their relationship with the nanostore?

Appendix A.3

- Do “X” (What they do): What does the nanostore do? What are the primary activities of the nanostores?

- Through “Y” (How they function): How does the nanostore conduct its operations? What resources and processes are used for operation?

- With the purpose of “Z” (Why they matter): What is the underlying purpose? Why does it matter?

- Transformation: Which inputs are converted into outputs at the nanostore? What are the key nanostore processes performed?

- Actors: Who perform the nanostore activities?

- Suppliers: Who supplies/inputs the products that the nanostore sells?

- Customers/beneficiaries: Who benefits from (or is affected by) the activities conducted by the nanostore? In what ways?

- Owner: Who is responsible for the nanostore operation? And how?

- Interveners: Who shapes the broader context? Who, from the outside, provides the nanostore with context for its functioning and operation?

Appendix B. Survey Result Tables for X-Y-Z Questions

| Stakeholder Type | N | Sale of Goods | Source of Income/Employment | Convenience/Essential Goods | Supply Chain Point | Market Rival/Barrier | Personal Investment/Sustenance | Community Service |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Actors | 124 | 110 (89%) | 102 (82%) | 18 (15%) | 0% | 0 (0%) | 3 (2%) | 18 (15%) |

| Suppliers | 41 | 20 (49%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 21 (51%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| Customers | 15 | 13 (87%) | 2 (13%) | 10 (67%) | 0% | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (13%) |

| Owner | 7 | 7 (100%) | 7 (100%) | 2 (29%) | 0% | 0 (0%) | 7 (100%) | 1 (14%) |

| Interveners | 22 | 19 (86%) | 0 (0%) | 3 (14%) | 0% | 14 (64%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (5%) |

| Stakeholder Type | N | Physical Store | Human Resources | Supplies | Admin/Tech Systems | Specific Tools/Processes | Market Transactions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Actors | 124 | 92 (74%) | 81 (65%) | 39 (31%) | 7 (6%) | 18 (15%) | 0 (0%) |

| Suppliers | 42 | 2 (5%) | 0 (0%) | 32 (76%) | 0 (0%) | 3 (7%) | 0 (0%) |

| Owner | 7 | 6 (86%) | 5 (71%) | 7 (100%) | 3 (43%) | 2 (29%) | 0 (0%) |

| Customers | 15 | 11 (73%) | 9 (60%) | 2 (13%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (7%) | 0 (0%) |

| Interveners | 22 | 7 (32%) | 5 (23%) | 7 (32%) | 1 (5%) | 0 (0%) | 14 (64%) |

| Stakeholder Type | N | Generate Income/Sustenance | Serve Community/Clients | Business Growth/Loyalty | Provide Essential Goods | Market Competition |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Actors | 124 | 106 (85%) | 18 (15%) | 6 (5%) | 14 (11%) | 0 (0%) |

| Suppliers | 42 | 19 (45%) | 4 (10%) | 1 (2%) | 8 (19%) | 0 (0%) |

| Owner | 7 | 7 (100%) | 2 (29%) | 4 (57%) | 2 (29%) | 0 (0%) |

| Customers | 15 | 4 (27%) | 3 (20%) | 0 (0%) | 11 (73%) | 0 (0%) |

| Interveners | 22 | 15 (68%) | 1 (5%) | 0 (0%) | 5 (23%) | 7 (32%) |

References

- Fransoo, J.C.; Blanco, E.; Mejia-Argueta, C. Reaching 50 Million Nanostores: Retail Distribution in Emerging Megacities; CreateSpace Independent Publisher Platform: Columbia, SC, USA, 2017; ISBN 978-1-9757-4200-3. [Google Scholar]

- Boulaksil, Y.; Fransoo, J.; Koubida, S. Small Traditional Retailers in Emerging Markets; BETA Publicatie: Working Papers; Technische Universiteit Eindhoven: Eindhoven, The Netherlands, 2014; Volume 460. [Google Scholar]

- D’Andrea, G.; Lopez-Aleman, B.; Stengel, A. Why Small Retailers Endure in Latin America. Int. J. Retail. Distrib. Manag. 2006, 34, 661–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escamilla González Aragón, R.C.; Fransoo, J.; Mejía Argueta, C.; Velázquez Martínez, J.; Gastón Cedillo Campos, M. Nanostores: Emerging Research in Retail Microbusinesses at the Base of the Pyramid. In Academy of Management Global Proceedings; Academy of Management: Valhalla, NY, USA, 2020; p. 161. [Google Scholar]

- Paswan, A.; Pineda, M.d.l.D.S.; Ramirez, F.C.S. Small versus Large Retail Stores in an Emerging Market—Mexico. J. Bus. Res. 2010, 63, 667–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega-Jimenez, C.H.; Amador-Matute, A.M.; Parada-Lopez, J.S. Logistics and Information Technology: A Systematic Literature Review of Nanostores from 2014 to 2023. In Proceedings of the 21st LACCEI International Multi-Conference for Engineering, Education and Technology (LACCEI 2023): “Leadership in Education and Innovation in Engineering in the Framework of Global Transformations: Integration and Alliances for Integral Development”, Hybrid Event, Buenos Aires, Argentina, 19–21 July 2023; Latin American and Caribbean Consortium of Engineering Institutions: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Salinas-Navarro, D.E.; Vilalta-Perdomo, E.; Mejía-Argueta, C. Beyond the Counter: A Systemic Mapping of Nanostore Identities in Traditional, Informal Retail Through Multi-Dimensional Archetypes. Systems 2025, 13, 546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salinas-Navarro, D.E.; Vilalta-Perdomo, E.; Michel-Villarreal, R. Empowering Nanostores for Competitiveness and Sustainable Communities in Emerging Countries: A Generative Artificial Intelligence Strategy Ideation Process. Sustainability 2024, 16, 11244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rangel-Espinosa, M.F.; Hernández-Arreola, J.R.; Pale-Jiménez, E.; Salinas-Navarro, D.E.; Mejía Argueta, C. Increasing Competitiveness of Nanostore Business Models for Different Socioeconomic Levels. In Supply Chain Management and Logistics in Emerging Markets; Yoshizaki, H.T.Y., Mejía Argueta, C., Mattos, M.G., Eds.; Emerald Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2020; pp. 273–298. ISBN 978-1-83909-333-3. [Google Scholar]

- Coen, S.E.; Ross, N.A.; Turner, S. “Without Tiendas It’s a Dead Neighbourhood”: The Socio-Economic Importance of Small Trade Stores in Cochabamba, Bolivia. Cities 2008, 25, 327–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinlocke, R.; Thomas-Hope, E. Characterisation, Challenges and Resilience of Small-Scale Food Retailers in Kingston, Jamaica. Urban Forum 2019, 30, 477–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espejo, R. Aspects of Identity, Cohesion, Citizenship and Performance in Recursive Organisations. Kybernetes 1999, 28, 640–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron, S.; Harris, K.; Leaver, D.; Oldfield, B.M. Beyond Convenience: The Future for Independent Food and Grocery Retailers in the UK. Int. Rev. Retail. Distrib. Consum. Res. 2001, 11, 395–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega-Jiménez, C.H.; Amador-Matute, A.; Parada López, J.; Zavala-Fuentes, D.; Sevilla, S. A Meta-Analysis of Nanostores: A 10-Year Assessment. In Proceedings of the 2nd LACCEI International Multiconference on Entrepreneurship, Innovation and Regional Development (LEIRD 2022): “Exponential Technologies and Global Challenges: Moving Toward a New Culture of Entrepreneurship and Innovation for Sustainable Development”, Virtual, 6–7 December 2022; Latin American and Caribbean Consortium of Engineering Institutions: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Pathak, A.A.; Kandathil, G. Strategizing in Small Informal Retailers in India: Home Delivery as a Strategic Practice. Asia Pac. J. Manag. 2020, 37, 851–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Everts, J. Consuming and Living the Corner Shop: Belonging, Remembering, Socialising. Soc. Cult. Geogr. 2010, 11, 847–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espejo, R. What Is Systemic Thinking? Syst. Dyn. Rev. 1994, 10, 199–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beer, S. Diagnosing the System for Organizations; Classic Beer Series; Wiley: Chichester, UK, 1985; ISBN 978-0-471-90675-9. [Google Scholar]

- Espejo, R.; Bowling, D.; Hoverstadt, P. The Viable System Model and the Viplan Software. Kybernetes 1999, 28, 661–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulrich, H.; Probst, G. (Eds.) Self-Organization and Management of Social Systems: Insights, Promises, Doubts, and Questions; Springer Series in Synergetics; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany; New York, NY, USA, 1984; ISBN 978-0-387-13459-8. [Google Scholar]

- Espejo, R. Self-construction of Desirable Social Systems. Kybernetes 2000, 29, 949–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Checkland, P.; Scholes, J. Soft Systems Methodology: A 30-Year Retrospective, new ed.; Wiley: Chichester, UK; New York, NY, USA, 1999; ISBN 978-0-471-98605-8. [Google Scholar]

- Gano-An, J.C.; Gempes, G.P. The Success and Failures of Sari-Sari Stores: Exploring the Minds of Women Micro-Entrepreneurs. HOLISTICA—J. Bus. Public Adm. 2020, 11, 25–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Funahashi, T. Sari-Sari Stores as Sustainable Business by Women in the Philippines. In Base of the Pyramid and Business Process Outsourcing Strategies; Hayashi, T., Hoshino, H., Hori, Y., Eds.; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2023; pp. 75–96. ISBN 978-981-19-8170-8. [Google Scholar]

- Goswami, P.; Mishra, M.S. Would Indian Consumers Move from Kirana Stores to Organized Retailers When Shopping for Groceries? Asia Pac. J. Mark. Logist. 2009, 21, 127–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mexican Government Retail Trade of Groceries and Food. Available online: https://www.economia.gob.mx/datamexico/en/profile/industry/retail-trade-of-groceries-and-food (accessed on 9 June 2025).

- Talamas Marcos, M.Á. Surviving Competition: Neighborhood Shops vs. Convenience Chains; Inter-American Development Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basu, P. Future of the Kirana Stores in India 2024. Available online: https://durham-repository.worktribe.com/output/2147572 (accessed on 30 August 2025).

- Granados-Rivera, D.; Mejía, G.; Tinjaca, L.; Cárdenas, N. Design of a Nanostores’ Delivery Service Network for Food Supplying in COVID-19 Times: A Linear Optimization Approach. In Production Research; Rossit, D.A., Tohmé, F., Mejía Delgadillo, G., Eds.; Communications in Computer and Information Science; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; Volume 1408, pp. 19–32. ISBN 978-3-030-76309-1. [Google Scholar]

- Salinas-Navarro, D.E.; Alanis-Uribe, A.; da Silva-Ovando, A.C. Learning Experiences about Food Supply Chains Disruptions over the COVID-19 Pandemic in Metropolis of Latin America. In Proceedings of the 2021 IISE Annual Conference, Online, 22–25 May 2021; Ghate, A., Krishnaiyer, K., Paynabar, K., Eds.; Institute of Industrial and Systems Engineers (IISE): Norcross, GA, USA, 2021; pp. 495–500. [Google Scholar]

- Haboush-Deloye, A.L.; Knight, M.A.; Bungum, N.; Spendlove, S. Healthy Foods in Convenience Stores: Benefits, Barriers, and Best Practices. Health Promot. Pract. 2023, 24, 108S–111S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salinas, D.; Fransoo, J.; Mejia-Argueta, C.; Benitez, V. Food Logistics, 19 October 2018. Available online: https://www.foodlogistics.com/warehousing/blog/21032010/an-overlooked-weapon-in-the-fight-against-malnutrition-small-store-logistics (accessed on 30 August 2025).

- Ochoa, A.F.; Duarte, M.G.; Bueno, L.A.S.; Salas, B.V.; Alpírez, G.M.; Wiener, M.S. Systemic Analysis of Supermarket Solid Waste Generation in Mexicali, Mexico. JEP 2010, 01, 105–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidalgo-Carvajal, D.; Gutierrez-Franco, E.; Mejia-Argueta, C.; Suntura-Escobar, H. Out of the Box: Exploring Cardboard Returnability in Nanostore Supply Chains. Sustainability 2023, 15, 7804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bocken, N.M.P.; Short, S.W.; Rana, P.; Evans, S. A Literature and Practice Review to Develop Sustainable Business Model Archetypes. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 65, 42–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ram, M.; Theodorakopoulos, N.; Worthington, I. Policy Transfer in Practice: Implementing Supplier Diversity in the UK. Public Adm. 2007, 85, 779–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corner, P.D.; Pavlovich, K. Shared Value Through Inner Knowledge Creation. J. Bus. Ethics 2016, 135, 543–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giddens, A. The Constitution of Society: Outline of the Theory of Structuration, 1st ed.; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 1986; ISBN 978-0-520-05728-9. [Google Scholar]

- Beer, S. Decision and Control: The Meaning of Operational Research and Management Cybernetics; Stafford Beer Classic Library; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Chichester, UK, 1994; ISBN 978-0-471-94838-4. [Google Scholar]

- Salinas-Navarro, D.E. Performance in Organisations, An Autonomous Systems Approach; Lambert Academic Publishing: Saarbrücken, Germany, 2010; ISBN 978-3-8383-4887-2. [Google Scholar]

- Argyris, C.; Schön, D.A. Organizational Learning II: Theory, Method, and Practice; Addison-Wesley Series on Organizational Development; Addison-Wesley: Reading, MA, USA, 1999; ISBN 978-0-201-62983-5. [Google Scholar]

- Espejo, R. Requirements for Effective Participation in Self-Constructed Organizations. Eur. Manag. J. 1996, 14, 414–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Freeman, R.E.E.; McVea, J. A Stakeholder Approach to Strategic Management. SSRN J. 2001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granovetter, M. Economic Action and Social Structure: The Problem of Embeddedness. Am. J. Sociol. 1985, 91, 481–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barney, J. Firm Resources and Sustained Competitive Advantage. J. Manag. 1991, 17, 99–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Zeeuw, G. Three Phases of Science: A Methodological Exploration; Working Paper 7; Centre for Systems and Information Sciences, University of Lincolnshire and Humberside: Lincoln, UK, 1996; p. 7. [Google Scholar]

- Vahl, M. Doing Research in the Social Domain. In Systems for Sustainability; Stowell, F.A., Ison, R.L., Armson, R., Holloway, J., Jackson, S., McRobb, S., Eds.; Springer US: Boston, MA, USA, 1997; pp. 147–152. ISBN 978-1-4899-0267-2. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann, V.; Doan, M.K.; Harigaya, T. Self-Selection versus Population-Based Sampling for Evaluation of an Agronomy Training Program in Uganda. J. Dev. Eff. 2024, 16, 375–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stratton, S.J. Population Research: Convenience Sampling Strategies. Prehosp. Disaster Med. 2021, 36, 373–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birt, L.; Scott, S.; Cavers, D.; Campbell, C.; Walter, F. Member Checking: A Tool to Enhance Trustworthiness or Merely a Nod to Validation? Qual. Health Res. 2016, 26, 1802–1811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mora-Quiñones, C.; Cárdenas-Barrón, L.; Velázquez-Martínez, J.; Gámez-Pérez, K. The Coexistence of Nanostores within the Retail Landscape: A Spatial Statistical Study for Mexico City. Sustainability 2021, 13, 10615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guest, G.; MacQueen, K.; Namey, E. Applied Thematic Analysis; SAGE Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2012; ISBN 978-1-4129-7167-6. [Google Scholar]

- Saunders, M.N.K.; Lewis, P.; Thornhill, A. Research Methods for Business Students, 9th ed.; Financial Times/Prentice Hall: Harlow, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2007; ISBN 978-0-273-70148-4. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popper, K.R. The Logic of Scientific Discovery; Routledge Classics; Routledge: London, UK, 2008; ISBN 978-0-415-27843-0. [Google Scholar]

- De Zeeuw, G. Values, Science and the Quest for Demarcation. Syst. Res. 1995, 12, 15–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, L. Validity, Reliability, and Generalizability in Qualitative Research. J. Fam. Med. Prim. Care 2015, 4, 324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drisko, J.W. Transferability and Generalization in Qualitative Research. Res. Soc. Work. Pract. 2025, 35, 102–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maturana, H.R.; Varela, F.J. The Tree of Knowledge: The Biological Roots of Human Understanding; Shambhala: Boston, MA, USA, 2008; ISBN 978-0-87773-642-4. [Google Scholar]

- Espejo, R.; Schwaninger, M. (Eds.) Organisational Fitness: Corporate Effectiveness Through Management Cybernetics; Campus-Verlag: Frankfurt am Main, Germany, 1993; ISBN 978-3-593-34783-7. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan, G. Images of Organization, Executive ed., 1st ed.; Berrett-Koehler Publishers: San Francisco, CA, USA; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1998; ISBN 978-1-57675-038-4. [Google Scholar]

- Flood, R.L.; Jackson, M.C. Creative Problem Solving: Total Systems Intervention; Wiley: Chichester, UK; New York, NY, USA, 1991; ISBN 978-0-471-93052-5. [Google Scholar]

- Mingers, J.; Gill, A. (Eds.) Multimethodology: The Theory and Practice of Combining Management Science Methodologies; Wiley: Chichester, UK; New York, NY, USA, 1997; ISBN 978-0-471-97490-1. [Google Scholar]

- Espejo, R. An Enterprise Complexity Model: Variety Engineering and Dynamic Capabilities. Int. J. Syst. Soc. 2015, 2, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espejo, R.; Stewart, N.D. Systemic Reflections on Environmental Sustainability. Syst. Res. 1998, 15, 483–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buldeo Rai, H.; Kang, S.; Sakai, T.; Tejada, C.; Yuan, Q.; Conway, A.; Dablanc, L. ‘Proximity Logistics’: Characterizing the Development of Logistics Facilities in Dense, Mixed-Use Urban Areas around the World. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2022, 166, 41–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meadows, D.H.; Wright, D. Thinking in Systems: A Primer; Chelsea Green Pub: White River Junction, VT, USA, 2008; ISBN 978-1-60358-055-7. [Google Scholar]

- Rai, H.B.; Cetinkaya, A.; Verlinde, S.; Macharis, C. How Are Consumers Using Collection Points? Evidence from Brussels. Transp. Res. Procedia 2020, 46, 53–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor, C.; Joffe, H. Intercoder Reliability in Qualitative Research: Debates and Practical Guidelines. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2020, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Zeeuw, G. The Acquisition of High Quality Experience. J. Res. Pract. 2005, 1, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

| TASCOI Role | X: What/Who (Identity and Activity) | Y: How (Means and Resources) | Z: Why (Purpose) | Example from the Dataset | Variations/Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Actors | Carry out retail, service, and logistics. | Staff, owners, and family members. | Seek employment, business growth, and community value. | “Staff who attend all day” | These actors may include delivery staff, cashiers, and family members. |

| Suppliers | Enable product variety and availability. | Deliver goods, maintain supply chains. | Support the store’s commercial viability. | “Suppliers of each sold product” | Local vs. national suppliers, reliability varies. |

| Customers | Sale/receive goods/services, define demand. | Interact at the store, purchase, and give feedback. | Satisfy needs, seek convenience, and community ties. | “Close customers”, “People who are passing by” | Frequency, loyalty, and needs differ by segment. |

| Owners | Generate income/sustenance and provide employment; oversee, invest, and manage. | Make strategic, financial, and operational choices. | Ensure family sustenance and long-term viability. | “The owner… is responsible for the operation.” | Sometimes, actors and owners play dual roles. |

| Interveners | Sale of goods, influence context, and competition. | Compete, manage, or enable operations. | Shape the market, set competition norms, and provide retail infrastructure. | “Direct competition”, “The government and the arrangements” | It can be positive (support) or negative (barriers). |

| X Identity (What/Who) | Transformation: Inputs → Outputs and Key Processes | Example from the Dataset | Variation/Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Retail Sales of Everyday Goods | Inventory, staff time, supplier goods → Sold products, customer satisfaction. Key processes include stocking, merchandising, sales, and checkout. | “Sale of consumer products such as soft drinks, ham, etc.” “Arrange material and sell.” | Transformation is transactional and product-focused. |

| Source of Employment/Income | Employee labour, store infrastructure, inventory → wages, financial stability, job satisfaction. Key processes include shift management, payroll, and customer service. | “It’s a source of employment.”, “Your source of income.” | Transformation centres on converting labour into livelihoods and security. |

| Community Service/Convenience | Access to location, product variety, staff attention → neighbourhood convenience, social capital, trust. Key processes: extended hours, personalised service, local engagement. | “Serve nearby customers.” “Meet neighbourhood needs.” | Transformation emphasises the social value and accessibility over pure sales. |

| Family/Personal Investment | Family labour, personal capital, shared responsibilities → family income, business experience, generational skills. Key processes include joint decision-making, intergenerational training, and flexible roles. | “Family project.”, “Own business.” | Transformation integrates economic and family/social outcomes. |

| Market Rival/Barrier | Competitive pricing, product selection, marketing efforts → market share, customer retention, barriers to entry for others. Key processes include monitoring competitors, conducting promotional activities, and adjusting the product mix. | “Direct competition.”, “It represents a barrier because it is direct competition.” | External market dynamics and the level of competition shape the transformation. |

| Dimension | Category (Theme) | Description | Example Responses |

|---|---|---|---|

| X | Retail Sales of Everyday Goods | The nanostore sells groceries, snacks, pharmacy items, stationery, and other essential products. | “Sale of consumer products such as soft drinks, ham, etc.”, “Sale of stationery products.” |

| Source of Employment/Income | The nanostore is a workplace and the primary source of income for staff and owners. | “It’s a source of employment.” “My source of income.” | |

| Community Service/Convenience | The nanostore is valued for its accessibility, convenience, and service to the neighbourhood. | “Serve nearby customers.”, “Meet neighbourhood needs.” | |

| Family/Personal Investment | The nanostore is seen as a family project or personal investment. | “Family project.”, “Own business.” | |

| Market Rival/Barrier | The nanostore is seen as a competitor or obstacle in the local market. | “Direct competition.”, “It represents a barrier because it is direct competition.” | |

| Supply Chain Delivery Point | The nanostore is seen as a link or destination in product supply chains. | “It represents a delivery point”, “it is another client to make deliveries” | |

| Y | Physical Store/Infrastructure | Operations depend on the physical location, premises, and tangible infrastructure. | “Through its establishment.”, “At your premises.” |

| Human Resources/Personnel | Staff, owners, or family members carry out activities. | “Staff who attend.”, “A person who attends all day.” | |

| Supplier Networks | The nanostore sources goods from external suppliers and brands. | “Buys products from suppliers.”, “Receives merchandise from Bimbo, Sabritas, and others.” | |

| Operational Tools/Processes | Use of specific tools, equipment, or routines (e.g., delivery bikes, refrigerators). | “Use bicycles for delivery.”, “Cash register.” | |

| Customer Service/Community Engagement | Focus on serving clients and engaging with the community. | “Serve customers.”, “It offers home delivery service.” | |

| Z | Generating Income/Sustenance | The primary purpose is to provide economic benefit or financial security. | “Generate income for the family.”, “To have a livelihood.” |

| Providing Essential Goods/Services | The purpose is to provide essential products and services to the community. | “Meet customer needs.”, “Offer basic necessities.” | |

| Supporting Family/Personal Project | The nanostore is a family business or personal investment. | “Family project.”, “Help the family.” | |

| Serving the Community | The purpose is to contribute to or support the local community. | “Helping the community.” “To be useful to the neighbourhood.” |

| Dimension | For Management and Problem Solving | For Decision and Policymaking | Response Themes |

|---|---|---|---|

| X | Identify core and alternative roles; diversify offerings; strengthen identity as an employer, service provider, competitor, supply chain link, or family asset. | Design and deploy support programmes that reflect nanostores’ social and economic functions and impact on their communities. |

|

| Y | Improve resource utilisation and processes; invest in infrastructure, staff development, and supplier relations; adopt relevant technology. | Set standards for fair, efficient, reliable supply chains, labour, and infrastructure support. |

|

| Z | Align goals with stakeholder needs (income, service, convenience, family, community); measure performance beyond sales. | Develop policies for microenterprise income stability, social impact, and local access. Ensure product availability, accessibility, and affordability. |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Salinas-Navarro, D.E.; Vilalta-Perdomo, E.; Herron, R.M.; Mejía-Argueta, C. Defining Nanostores: Cybernetic Insights on Independent Grocery Micro-Retailers’ Identity and Transformations. Systems 2025, 13, 771. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems13090771

Salinas-Navarro DE, Vilalta-Perdomo E, Herron RM, Mejía-Argueta C. Defining Nanostores: Cybernetic Insights on Independent Grocery Micro-Retailers’ Identity and Transformations. Systems. 2025; 13(9):771. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems13090771

Chicago/Turabian StyleSalinas-Navarro, David Ernesto, Eliseo Vilalta-Perdomo, Rebecca Michell Herron, and Christopher Mejía-Argueta. 2025. "Defining Nanostores: Cybernetic Insights on Independent Grocery Micro-Retailers’ Identity and Transformations" Systems 13, no. 9: 771. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems13090771

APA StyleSalinas-Navarro, D. E., Vilalta-Perdomo, E., Herron, R. M., & Mejía-Argueta, C. (2025). Defining Nanostores: Cybernetic Insights on Independent Grocery Micro-Retailers’ Identity and Transformations. Systems, 13(9), 771. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems13090771