1. Introduction

In recent years, China has increasingly prioritized rural revitalization as a national development strategy aimed at addressing deep-rooted urban-rural disparities and promoting sustainable rural growth. As the rural policy agenda gradually moves beyond the poverty alleviation phase, it becomes necessary to re-examine the dominant models of external intervention [

1]. Traditional rural assistance approaches, which historically relied on economic aid and technological inputs, used to play an important role during earlier development stages [

2,

3]. However, experience from the field has shown that these approaches alone are often insufficient to ensure long-term sustainability and can impose significant financial burdens [

4,

5]. This realization has prompted a growing recognition of the need for more systemic and integrated models of support–approaches that move beyond unidimensional economic metrics and take into account the social, cultural, and institutional dimensions of rural development [

6]. Moreover, the government has also come to recognize that the vast and complex task of rural revitalization cannot be achieved through state power alone. In this context, the role of corporate engagement has become more prominent and is increasingly viewed as a vital supplement to government-led efforts [

7].

Recent scholarship has begun to re-examine the role of SOEs under the new revitalization paradigm in China. Kan and Song [

8] demonstrate that corporate engagement in rural revitalization not only improves financial performance but also strengthens firms’ capacity for social responsibility, illustrating the synergistic potential of development and accountability. A case study of Huanglongxian Village, reveal that co-governance between government, SOEs, and communities enhances local identity and strengthens place-making through participatory reconstruction [

9]. From another perspective, Zhang et al. [

10] reveals that state-owned equity participation can effectively incentivize private enterprises to engage in rural revitalization, particularly by mitigating financial constraints and aligning policy incentives. These studies indicate that SOEs are no longer confined to capital provision roles; rather, they have potentials to act as an institutional catalyst embedded within evolving governance assemblages.

To address these gaps, this paper adopts a systems-theoretic perspective, reconceptualizing rural social capital as a dynamic system composed of structural, relational, and cognitive subsystems interacting within complex governance environments [

11]. Social capital theory has provided important insights into how networks of trust, norms, and reciprocal relations underpin rural communities’ adaptive capacities and resilience [

12,

13], offering a robust analytical framework for understanding multi-actor and cross-scalar interventions in rural development [

14,

15]. However, while extensive research employing the framework of social capital were concentrated in urban and organizational contexts, comparatively limited attention has been paid to rural settings [

16]. In rural China, where social structures are often characterized by low levels of institutionalization and a strong reliance on informal, relationship-based governance, these conditions make rural areas particularly valuable sites for applying the analytical lens of social capital. This perspective helps reveal how trust, reciprocity, and social networks sustain everyday rural life, while also highlighting the challenges and opportunities that external interventions may encounter [

17].

This study takes China Southern Power Grid (CSG) as the focal organization and systematically examines its 11 rural assistance projects implemented across different provincial subsidiaries. Through this empirical basis, the study aims to illustrate how SOEs operate as systemic nodes, orchestrating social capital transfers across different governance scales to enhance rural systemic resilience.

Specifically, the research objectives are threefold: first, to conceptualize the systemic dimensions of social capital as structural (network topology), relational (trust-based governance), and cognitive (localized knowledge integration) components; second, to empirically investigate how SOEs employ hybrid governance mechanisms, characterized by strong commitments and flexible contracts, to rebuild and activate rural social capital networks; and third, to assess the implications of these systemic interventions for long-term rural development sustainability. Ultimately, this study contributes theoretically to the broader understanding of complex social systems in rural revitalization, while providing practical insights into policy design for sustainable rural governance in China.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Study Area and Case Selection

This study focuses on the rural revitalization projects conducted by China Southern Power Grid (CSG), a major state-owned enterprise (SOE) operating primarily in southern China. Specifically, we selected representative rural assistance cases implemented between 2022 and 2024 across Guangdong, Guangxi, Yunnan, and Guizhou provinces. These provinces were selected due to their varying levels of rural development, institutional capacities, and diverse governance structures, thus providing a comprehensive basis for comparative analysis.

The selected cases encompass multiple rural revitalization domains, including industrial development, ecological improvement, infrastructure upgrading, and human capital enhancement, consistent with China’s rural revitalization strategy. A purposive sampling approach was adopted to ensure diversity in project type, governance complexity, and socio-economic contexts.

3.2. Data Collection and Analysis

This research adopts a qualitative multi-case study approach, combining primary and secondary data sources to ensure triangulation and analytical robustness. Fieldwork was conducted from May 2023 to January 2024 across selected rural assistance projects implemented by CSG. From the full pool of 199 projects, 11 cases were purposively selected as representative examples based on geographic distribution, project type (e.g., infrastructure, agriculture, vocational training), and implementation depth. These cases were identified as particularly illustrative of institutionalized intervention mechanisms and cross-sector coordination patterns.

Primary data were collected through field visits, participatory observations, and 36 in-depth semi-structured interviews with key stakeholders, including SOE project managers, local government officials, village committee members, and beneficiary farmers. Interviews were conducted with informed consent, audio-recorded, and transcribed in full. Observations included participation in planning meetings, project evaluation activities, and site-based implementation processes, where the researchers were involved in a consultant or facilitator capacity.

Thematic coding was applied to the interview transcripts using NVivo 14 software, following an abductive logic that moved iteratively between emerging empirical patterns and the theoretical framework of structural, relational, and cognitive social capital. Codes were developed inductively and then grouped into analytical categories aligned with the three dimensions of social capital. To enhance internal validity, researcher memos and observation notes were triangulated with interview data to verify organizational practices and relational dynamics.

While participants offered valuable insights, their views were inevitably shaped by their institutional roles, personal experiences, and expectations. To address potential subjectivity, the analysis focused on patterns of interaction, institutional arrangements, and relational structures rather than on isolated individual opinions. Reflexive attention was also given to the researchers’ positionality throughout the study design and interpretation process.

Secondary data included internal project documents, policy reports, implementation guidelines, and annual evaluation reports provided by CSG and relevant local governments. Academic literature, governmental statistics, and policy documents related to rural revitalization and social capital theory were also reviewed to contextualize and triangulate the primary data findings.

4. Case Analysis and Findings

This section analyzes eleven cases of CSG’s interventions in rural revitalization across different regions. Despite their diverse local conditions, the cases reveal three overarching patterns of social capital reconstruction. First, SOEs often mobilize structural capital by integrating fragmented village resources and aligning them with broader institutional frameworks. Second, relational capital is fostered through the establishment of hybrid governance mechanisms, blending enterprise logic with grassroots participation and trust-building. Third, cognitive capital emerges from localized training, symbolic recognition, and market-oriented learning processes, enabling villagers to co-produce development pathways. These three modes interact within a dynamic feedback system, reflecting a systemic approach to governance. The following sections unpack each dimension with detailed empirical illustrations.

4.1. Structural Capital Reconstruction: Multi-Path Embedding to Reshape Rural Network Structures

In the context of rural revitalization, China’s rural governance system is composed of a complex constellation of actors with varying degrees of capacity, autonomy, and connectivity. These typically include:

Village collectives: which serve as nominal governance cores but often lack technical capacity and economic autonomy;

Local government entities: responsible for policy transmission and resource allocation, but frequently constrained by staffing and fragmentation;

Cooperatives and small-scale local enterprises, which act as intermediaries between production and market but exhibit uneven organizational maturity;

Individual households and farmers: who remain the end beneficiaries but have limited power to shape system-wide coordination.

This actor constellation exhibits characteristics of a loosely coupled system with high relational dependency but low structural integration. Network topologies are often fragmented, hierarchical linkages weak, and cross-node communication sparse. In such a context, external actor, particularly state-owned enterprises (SOEs), can serve as institutional integrators or temporary governance nodes, reconfiguring the spatial and organizational logic of the local system through targeted embedding strategies.

Based on empirical fieldwork, this study identifies four distinct modes of structural embedding through which SOEs reshape rural network architectures:

4.1.1. Mode One: Resource-Rich Villages with Local Organizational Capacity

In villages with well-established cooperatives or collective enterprises, SOEs tend to serve as resource integrators, supporting endogenous coordination while expanding external linkages. For example, In Niugong Village of Lüchun County, Yunnan Province, the Honghe Branch of Southern Power Grid applied a structural embedding model to rebuild rural governance networks through multi-actor coordination. Under the framework of “Assisting Entity + Local Enterprise + Village Collective + Cooperative + Farmers”, the SOE provided infrastructure investment and facilitated market access, while local actors took responsibility for daily production and management. This arrangement enhanced role differentiation and improved the internal connectivity of the rural system.

To support the cooperative’s development, the assisting entity actively coordinated with township and county governments to secure over CNY 3.7 million in East–West cooperation project funding. These resources were used to expand processing capacity and implement order-based production, linking the village to broader regional markets. A “6:2:2” profit-sharing mechanism was introduced, allocating 60% of profits to farmers and cooperative members, 20% to incentivise management, and 20% to strengthen the village collective economy—balancing interests across organisational levels.

By 2023, the tea cooperative had achieved CNY 6.2 million in cumulative sales revenue, with average household income increasing by more than CNY 2000. The village collective economy reached CNY 200,000, placing Niugong among the most economically resilient formerly impoverished villages in the region. The case illustrates how SOE-led interventions can restructure rural governance systems by building durable, locally grounded institutional linkages.

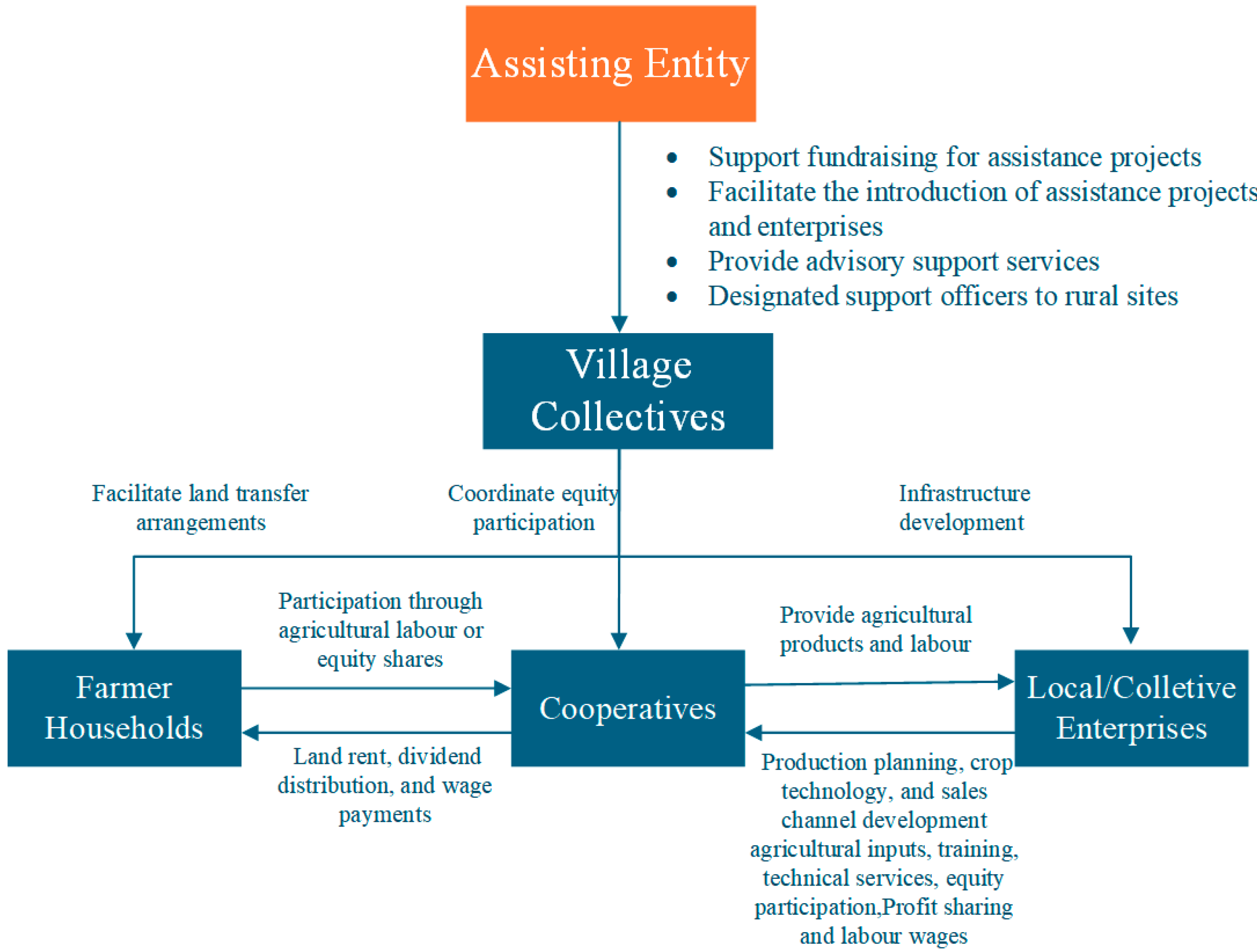

The governance structure followed a multilayered format (

Figure 1):

This governance model reflects a multi-level coordination framework in which distinct actors take on specialized but interdependent roles. The assisting entity (typically an SOE) functions as the institutional catalyst, mobilizing external resources, providing technical guidance, and connecting local production to broader markets. Rather than exercising full operational control, it delegates day-to-day tasks to local enterprises, which act as coordinators embedded in both rural and external systems. This division of labour ensures that strategic direction and local responsiveness are effectively aligned.

The village collective serves as the territorial and administrative anchor, safeguarding land-use rights and community legitimacy. Cooperatives function as organizational intermediaries, coordinating smallholder participation, aggregating production, and delivering technical services. Farmers, in turn, contribute labor, land, and local knowledge, while receiving income and support through formalized contracts. The overall system promotes horizontal integration and role complementarity, resulting in stronger network resilience, lower coordination costs, and enhanced local capacity for self-sustaining development.

4.1.2. Mode Two: Resource-Rich but Organizationally Fragmented Villages

In rural areas with favorable resource endowments but weak internal organizational capacity, such as the absence of local enterprises or limited collective governance experience, SOEs tend to adopt a platform-type embedding strategy. Rather than relying on endogenous coordination, the SOE introduces external anchor enterprises and acts as a convening intermediary that links village collectives, government actors, and market-oriented firms into a modular, semi-structured governance system.

This approach addresses two key structural limitations: low network centrality and fragmented stakeholder relations. By providing a stable institutional interface, the SOE facilitates the formation of vertical and horizontal linkages that gradually evolve into more hierarchical and dense governance structures. The result is a shift from isolated, transaction-based interactions to a more integrated rural economic system.

A case from Wayao Village in Baiyun District, Guizhou Province illustrates this model. In 2022, the Guizhou branch of the Southern Power Grid partnered with the district power utility to introduce both an aquaculture enterprise and an agritourism firm. These actors co-developed a compound rural revitalization project that combined fish farming with experiential agriculture. Under the coordination of the SOE, local government agencies, the village collective, and individual farmers collaborated to form a vertically integrated value chain centered on aquaculture. This project not only improved resource utilization but also expanded employment opportunities and diversified the village’s income base by linking traditional production with rural tourism markets.

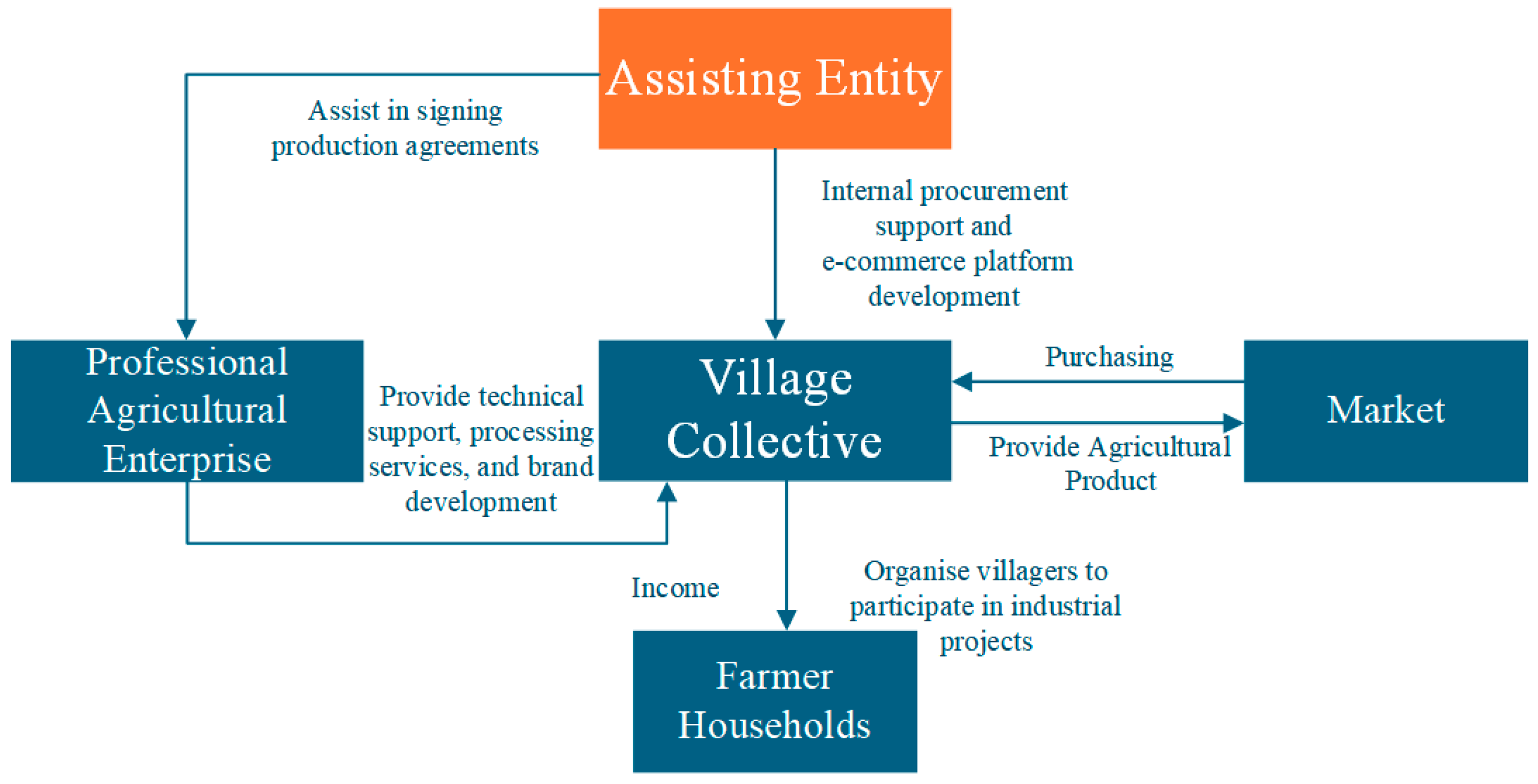

Through this externally anchored, platform-oriented model (

Figure 2), the SOE transformed the village’s governance structure from one of low density and weak integration into a system characterized by increased organizational layering, actor interdependence, and functional diversification. The success of this model demonstrates how SOEs can function as systemic brokers, assembling temporary institutional platforms that foster new economic ecologies in rural regions lacking internal coordination mechanisms.

4.1.3. Mode Three: Resource-Constrained but Market-Accessible Villages

In rural areas with moderate production capacity but limited market connectivity, SOEs often adopt a channel-building strategy aimed at improving the outward integration of local economies. In these contexts, internal resource flows are restricted and linkages to urban consumption systems remain weak. Rather than investing heavily in production infrastructure, SOEs intervene by constructing reliable and sustained sales pathways—thereby enabling the rural system to transition from an inward-looking to an outward-oriented economic configuration.

The case of Anning Village in Liuzhou, Guangxi Province, illustrates this model. As local fish farming expanded, small-scale producers encountered growing difficulties in accessing stable markets. To address this, the Liuzhou Power Supply Bureau developed a targeted procurement system, integrating agricultural products from the village cooperative into its employee canteen supply chain. This institutionalized, consumption-based linkage not only relieved sales pressure on producers but also helped expand cooperative scale and improve economic resilience.

Through this approach, the SOE functions as a market conduit, embedding rural products into formalized purchasing networks and enhancing the cooperative’s bargaining position. By facilitating demand-side integration, the enterprise enables rural producers to overcome scale and coordination barriers without requiring direct capital or technology injection. This model illustrates how structural capital can be reinforced through external linkages, shifting rural economies into broader systems of circulation and improving their systemic competitiveness (

Figure 3).

4.1.4. Mode Four: Resource and Capital-Constrained Villages

In villages facing both limited resources and weak financial capacity, SOEs adopt a financial embedding strategy to enhance capital flow and strengthen rural economic resilience. Traditional social capital networks often fail to meet the financing needs of modern agriculture, and farmers face barriers to accessing credit and insurance. To address this, SOEs collaborate with financial institutions to introduce rural credit schemes, agricultural insurance, and trust-based investment mechanisms.

In Donglan County, Guangxi, the Hechi Power Supply Bureau invested CNY 4.19 million to support edible mushroom production across 40 villages. Cooperatives managed input procurement and operations, while technical support was provided by a local agricultural firm. This model enabled capital and knowledge to reach farmers efficiently, expanded production capacity, and increased household incomes. By embedding financial tools into rural production systems, SOEs improve resource coordination, reduce risk, and lay the foundation for long-term industrial development (

Figure 4).

In summary, the embedding strategies of state-owned enterprises (SOEs) in rural revitalization are far from uniform. Instead, they are differentiated and adaptive, shaped by variations in local resource endowments, industrial bases, and organizational capacities. Through mechanisms such as resource integration, industrial linkage, market expansion, and financial embedding, SOEs reconfigure the topological structure of rural socio-economic networks. This restructuring process transforms fragmented and inward-looking systems into more connected, market-responsive, and resilient configurations.

Crucially, the institutional legitimacy of SOEs amplifies their capacity to act as central nodes in these rural systems. By promoting centralization, connectivity, and market orientation, they enhance the operational efficiency of rural economies while laying the groundwork for the reconstruction of social capital. From a systems perspective, these interventions foster multi-scalar coordination, activate feedback loops between actors and institutions, and support the emergence of more robust, adaptive, and sustainable rural systems.

4.2. Relational Capital Cultivation: Establishing Hybrid Governance Mechanisms Through Strong Commitment and Weak Contract

While structural embedding reshapes the spatial and institutional topology of rural systems, the long-term viability of these configurations hinges on the effective cultivation of relational capital—the trust-based ties, informal norms, and shared expectations that enable cooperation among heterogeneous actors. In many rural contexts with weak formal institutions, strong commitments and embedded interactions often substitute for enforceable contracts, laying the groundwork for hybrid governance mechanisms [

29].

A compelling illustration can be found in the Qinzhi Farm project in Badong Village, Potou District, Zhanjiang. Rather than directly controlling the project, the stationed team from Foshan Power Supply Bureau facilitated a locally rooted governance model of “Cooperative + Village Collective + Formerly Impoverished Households”. The village collective assumed the central organizational role: the village secretary served as the legal representative, committee members were responsible for financial and production oversight, and formerly poor households acted as group leaders for on-the-ground coordination. This arrangement was not cemented by strict legal contracts but by delegating management rights to the village, thereby enhancing its governance capacity and embedding a long-term incentive mechanism. Profits were not only distributed among the households but also reinvested into collective welfare projects, reinforcing community recognition and support. Through such commitment-based cooperation, the farm transitioned from a short-term assistance initiative into a self-sustaining rural enterprise, effectively bridging poverty alleviation with long-term revitalization.

The effectiveness of this model lies in its capacity to combine formal organizational roles with informal trust-building processes. Even in the absence of rigid contracts between the village committee and households, the mutual dependency on collective outcomes, such as income generation and local legitimacy, creates powerful internal motivations for sustained cooperation. The SOE, while instrumental in initiating the model and providing early-stage support, gradually withdrew from daily operations, enabling locally driven self-management and repositioning the village from recipient to protagonist.

To address the technical gap among local households, the project adopted a “master-apprentice” mechanism, where experienced aquaculture farmers mentored others through incentive structures such as fixed salaries plus profit shares. This hands-on approach not only reduced learning costs and project risks, but also created pathways for knowledge reproduction through social embeddedness, enhancing long-term resilience.

Importantly, the project’s relational capital-building efforts also strengthened collective governance. The decision to entrust the village committee and residents with daily farm operations fostered a strong sense of ownership and responsibility, transforming them from passive recipients into active stakeholders. This also enhanced the governance capability of the village collective, enabling the emergence of a community-led economic model that can function independently of external actors.

From a systems perspective, this case illustrates how rural transformation relies not only on material infrastructure or formal institutions, but also on relational feedback loops—reciprocal processes through which trust, learning, and coordination reinforce one another over time [

30]. These hybrid governance forms reflect polycentricity, flexibility, and embedded adaptability, aligning with core principles of resilient system design [

23,

24]. As such, the cultivation of relational capital is not merely a social phenomenon but a fundamental driver of systemic governance transformation.

4.3. Cognitive Capital Integration: Localizing Technical Standards and Knowledge Reproduction

In rural revitalization, cognitive capital refers to the shared knowledge systems, mental models, and interpretative frameworks through which actors make sense of and adapt to development interventions. While structural and relational capital provide the scaffolding for collective action, the sustainability of such action depends on whether external knowledge inputs—technologies, market logic, and institutional norms—can be meaningfully absorbed, internalized, and reproduced within rural contexts. Without such localization, technical support risks becoming extractive, episodic, or structurally mismatched with local lifeworlds.

A key insight from systems thinking is that knowledge transfer is not linear but circulatory, requiring iterative feedback loops and contextual adaptation [

30]. This study finds that successful cognitive capital integration often hinges on mechanisms that bridge external standards and local epistemologies. In Guangdong Power Grid’s aid initiatives, these mechanisms take the form of participatory demonstrations, adaptive training, and practical co-production. In the agricultural service outsourcing project in Xin’an Town, Huazhou City, for example, the SOE’s support team avoided top-down imposition of a new farming model. Instead, they held open consultations, invited farmers to compare costs and returns, and allowed local stakeholders to pilot production changes on a voluntary basis. Farmers began to accept modern operational models not through formal instruction, but through visible, self-interpreted benefits.

Such strategies of localization extend beyond production to encompass market cognition. In the case of Dongfang Village, Gaozhou City, farmers had strong planting skills but limited understanding of value chains. Rather than simply improving production techniques, the SOE facilitated the entry of hometown entrepreneurs to build a seedling base and fruit-processing factory, embedding the entire agricultural chain locally. This helped farmers comprehend and participate in branding, logistics, and pricing. Through this process, rural producers became not just laborers but knowledge holders within a modern agrarian system.

The reproduction of knowledge also relies on relationally embedded learning. Recognizing the limited efficacy of classroom-style training, the Zhuhai Power Supply Bureau in the same region adopted a mentorship model, pairing experienced growers with newcomers and incentivizing long-term engagement through profit-sharing schemes. This “apprenticeship system” embedded learning into daily labor, reducing the cognitive distance between external knowledge and local practice. In turn, this created an internal multiplier effect: farmers became informal teachers within the village, diffusing knowledge horizontally and fostering collective learning.

In systems terms, such arrangements enhance both absorptive capacity and system memory—the ability of rural communities to sustain learned practices after external actors withdraw. This aligns with the broader shift from projectized interventions to adaptive, endogenous development strategies. Ultimately, the integration of cognitive capital allows the rural system to not only operate with new knowledge, but to evolve its own knowledge regimes in response to environmental and market changes.

5. Discussion

Rural areas are not static or isolated spatial units but complex adaptive systems composed of interwoven subsystems. Within this system, natural resources, social relations, cultural cognition, and institutional governance together form a multi-dimensional interactive structural field. This article focuses on one of the often-overlooked yet critical subsystems: the system of social capital. Particularly in the context of rural revitalization, the reconstruction mechanisms, governance logic, and developmental potential of social capital have not received sufficient scholarly attention.

As an intangible and relational resource, social capital is inherently difficult to quantify and is often marginalized in policy interventions. This study proposes a three-dimensional analytical framework comprising structural, relational, and cognitive aspects to reorganize social capital as a systematic and actionable component. This approach not only endows social capital with dynamic system properties but also foregrounds its coupling with other subsystems such as industry, governance, and technology.

Within this system, the intervention of state-owned enterprises (SOEs) should not be treated as a simple injection of external variables but as a form of ecological embedding that disrupts and reshapes the original rural ecology. This embeddedness is not static; it evolves in response to the heterogeneity of rural resource endowments, organizational capacities, and market connections. As the four models presented in this paper demonstrate, SOEs adopt differentiated strategies rather than uniform templates. These strategies are developed through trial, feedback, and negotiation, dynamically adapting to local social logics and institutional constraints. This process reflects a mechanism of co-evolution in which external actors and endogenous systems mutually shape and adapt to one another [

30].

Rather than exerting unilateral control, SOEs often stimulate the emergence of collaborative and self-organized governance by enabling village collectives, cooperatives, and smallholder households. This has resulted in a model of cooperation built on weak contracts and strong commitments, which fosters local initiative and shared responsibility. Over time, such arrangements generate positive feedback loops. Village collectives build institutional capacity, accumulate technical knowledge, and reinforce the sustainability of development efforts even after SOEs withdraw. These feedback mechanisms manifest in three ways: structurally, through increased institutional legitimacy and access to resources; relationally, through strengthened trust networks and internalised roles; and cognitively, through the localized translation and re-coding of modern agricultural standards and market knowledge.

These micro-level interactions converge into macro-level path dependencies, reinforcing rural resilience and enabling greater autonomy in development trajectories. The shift from passive embedding to collaborative adaptation suggests that rural systems are capable of self-regulation and regeneration when enabling conditions are met. In this context, SOEs should be understood not as fixed authorities but as catalytic agents that realign the coupling between external resources and internal systems.

Additionally, the hybrid nature of SOEs, which combines political legitimacy, economic capacity, and organizational flexibility, makes them uniquely positioned to bridge the gap between administrative governance and community-based development. Unlike purely profit-driven capital or bureaucratic state interventions, SOEs can mobilize a combination of policy instruments, financial capital, and technical support. However, the effectiveness of their embedded governance strategies still depends on the absorptive capacity and collaborative willingness of local institutions. Sustainable reconstruction of social capital can only be achieved when external activation and internal mobilization are aligned.

This study has several limitations that should be acknowledged. First, the analysis focuses on a single type of actor, state-owned enterprises, within a specific sector and region, namely the energy industry in southern China. While the findings reveal transferable patterns of institutional coordination and social capital activation, caution is needed when generalizing to other regions or forms of rural intervention. Second, as a qualitative study based on a limited number of cases, the research uncovers deep mechanisms and relational dynamics but does not provide quantitative evaluations of impact. Third, the projects examined were implemented between 2022 and 2024, which means their long-term outcomes cannot yet be directly assessed and can only be inferred based on early-stage observations and stakeholder expectations. Fourthly, some cases also encountered implementation challenges, including mismatches between local needs and technical plans or limited participation from certain village groups. These experiences suggest that even well-resourced interventions must continuously adapt to evolving local conditions. Future research could expand the scope by incorporating cross-sector comparisons, longitudinal tracking, or mixed-method evaluations to assess sustainability and impact over time.

In summary, this study contributes to both empirical and theoretical debates by proposing a typology of SOE embeddedness and highlighting the pivotal role of social capital in coordinating across multiple subsystems. The findings suggest that SOEs are not merely implementers of policy, but institutional actors that help generate feedback, reconfigure local governance structures, and reproduce context-sensitive knowledge. Policymakers designing rural revitalization programs should consider building long-term partnerships with SOEs and other stable organizational actors, while also investing in the social foundations of rural systems—particularly trust, local networks, and collective learning capacities. These elements form the enabling environment for adaptive and resilient rural development.

While the study focuses on China, the insights have broader relevance for Global South contexts where state-led initiatives coexist with fragmented governance and uneven institutional capacity. In such settings, state-owned or quasi-public entities can serve as anchors for multi-level coordination if their interventions are embedded within local knowledge systems and social infrastructures. Future research should further explore how different types of organizations, such as cooperatives, NGOs, or private enterprises, perform comparable roles in rural systems, and how systemic governance can be sustained across diverse institutional environments.